1. Introduction

Orthopedic injuries, particularly distal radius and forearm fractures, are among the most common pediatric injuries encountered in the emergency department (ED), often requiring closed reduction and immobilization in the acute phase [

1]. Procedural sedation has remained the standard of care for analgesia and reduction success in pediatric patients, demonstrating a low rate of subsequent operative intervention [

2,

3]. Performing procedural sedation with agents, such as ketamine, facilitates optimal fracture reduction by minimizing patient movement, mitigating procedural distress, and therefore reducing the likelihood of additional reductions [

4].

Despite its advantages, procedural sedation presents notable drawbacks. While the risk of significant complications remains low, procedural sedation can lead to vomiting, agitation, hypoxia, apnea, and more notably laryngospasm [

5]. Additionally, increased length of stay (LOS) in the ED, increased physician and staff time, and prolonged post-procedural monitoring associated with procedural sedation contribute to greater healthcare costs and resource utilization [

6,

7]. As a result, alternative analgesic techniques have been explored to improve procedural efficiency and patient safety in pediatric emergency care.

Regional anesthesia techniques, including peripheral nerve blocks, field blocks, and intravenous regional anesthesia, have emerged as excellent alternatives to procedural sedation for providing analgesia during fracture reduction and management. Supraclavicular nerve block, in particular, has demonstrated similar analgesia and reduction success compared to procedural sedation, while maintaining high satisfaction and cost-effectiveness, minimizing medication usage, and shortening ED LOS [

8,

9,

10]. Herein, we present a series of three pediatric cases in which supraclavicular nerve blocks were successfully performed for reduction of forearm fractures in the ED. We highlight the clinical scenarios which prompted the need for a viable, safe, and effective alternative to procedural sedation with comparable post-procedural outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ultrasound-Guided Supraclavicular Nerve Block

Ultrasound-guided nerve block is a technique where ultrasound imaging is used to visualize the anatomy and guide the placement of a needle to deliver a local anesthetic around a specific nerve or group of nerves. This approach is particularly useful for performing precise nerve blocks with enhanced safety and effectiveness, as it allows the clinician to see the nerves, blood vessels, and surrounding structures in real-time.

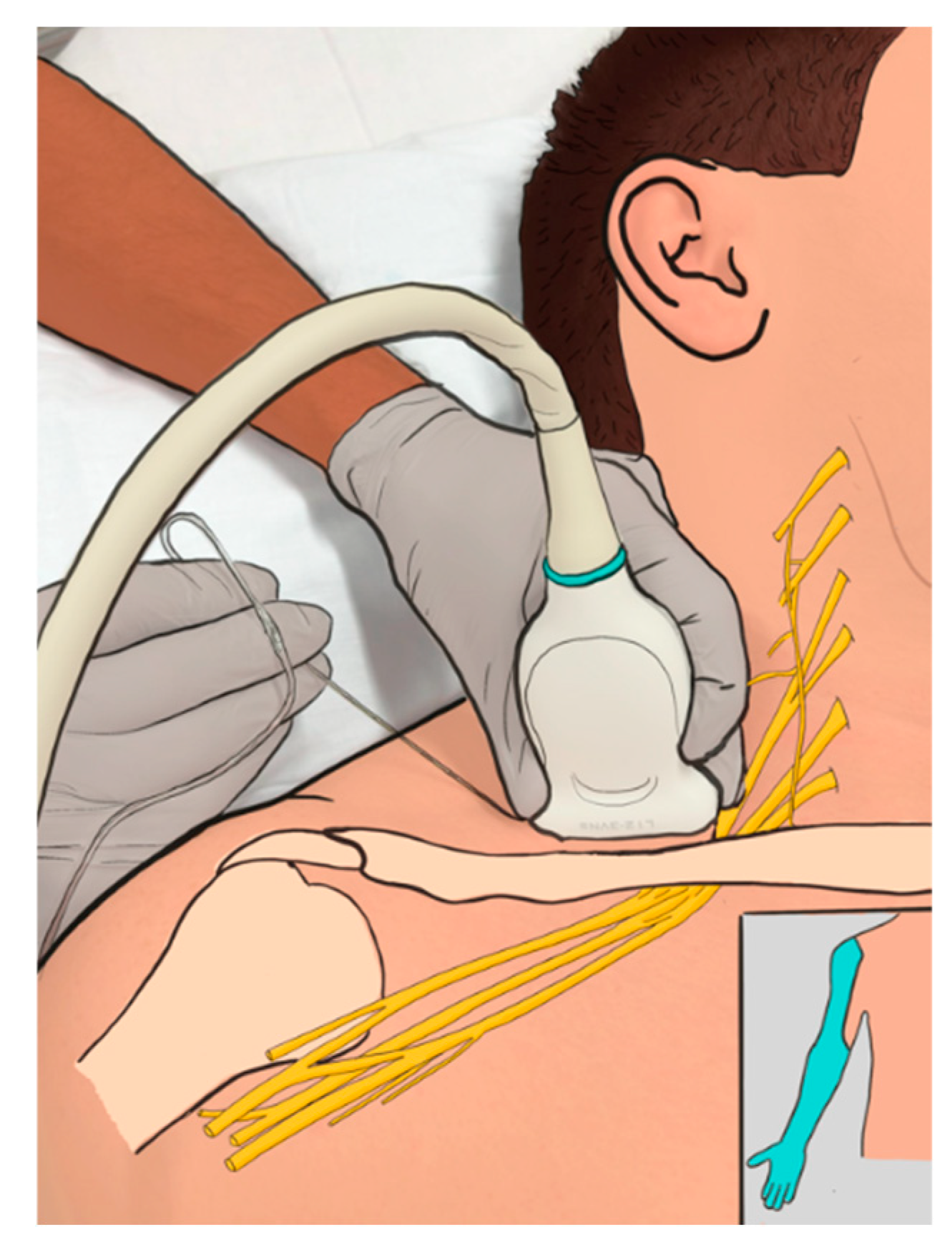

An ultrasound-guided supraclavicular nerve block involves the injection of a local anesthetic near the brachial plexus, specifically at the level of the supraclavicular fossa (the area just above the clavicle), providing anesthesia to the upper extremity, including part of the shoulder, arm, and hand (

Figure 1).

2.2. Procedure Overview

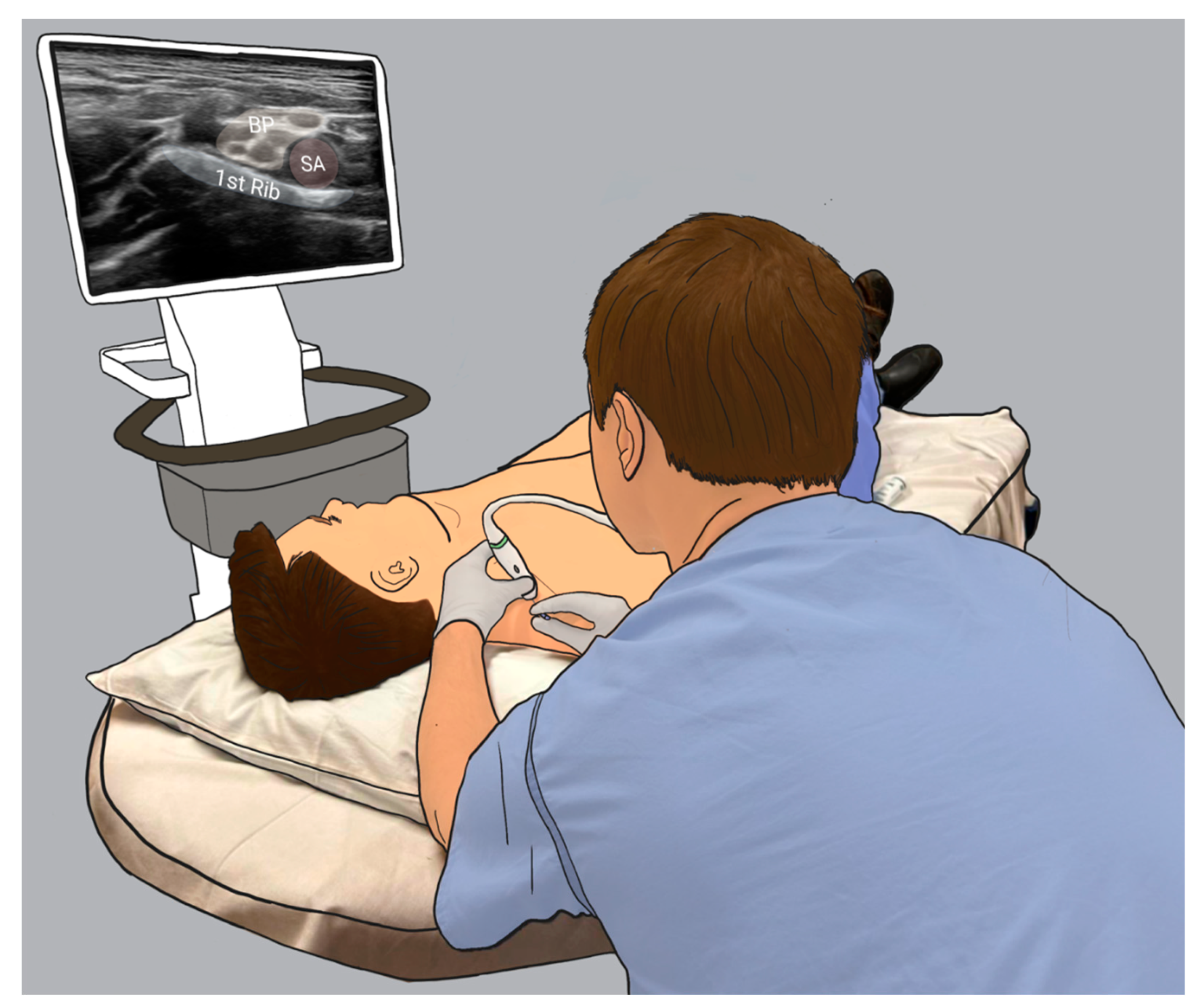

Positioning: The patient is typically positioned in a supine or slightly lateral position with the head turned away from the side of the procedure. The arm is placed in a neutral or slightly abducted position to expose the supraclavicular region. The ultrasound machine is placed on the opposite side of the bed (

Figure 2) [

11,

12].

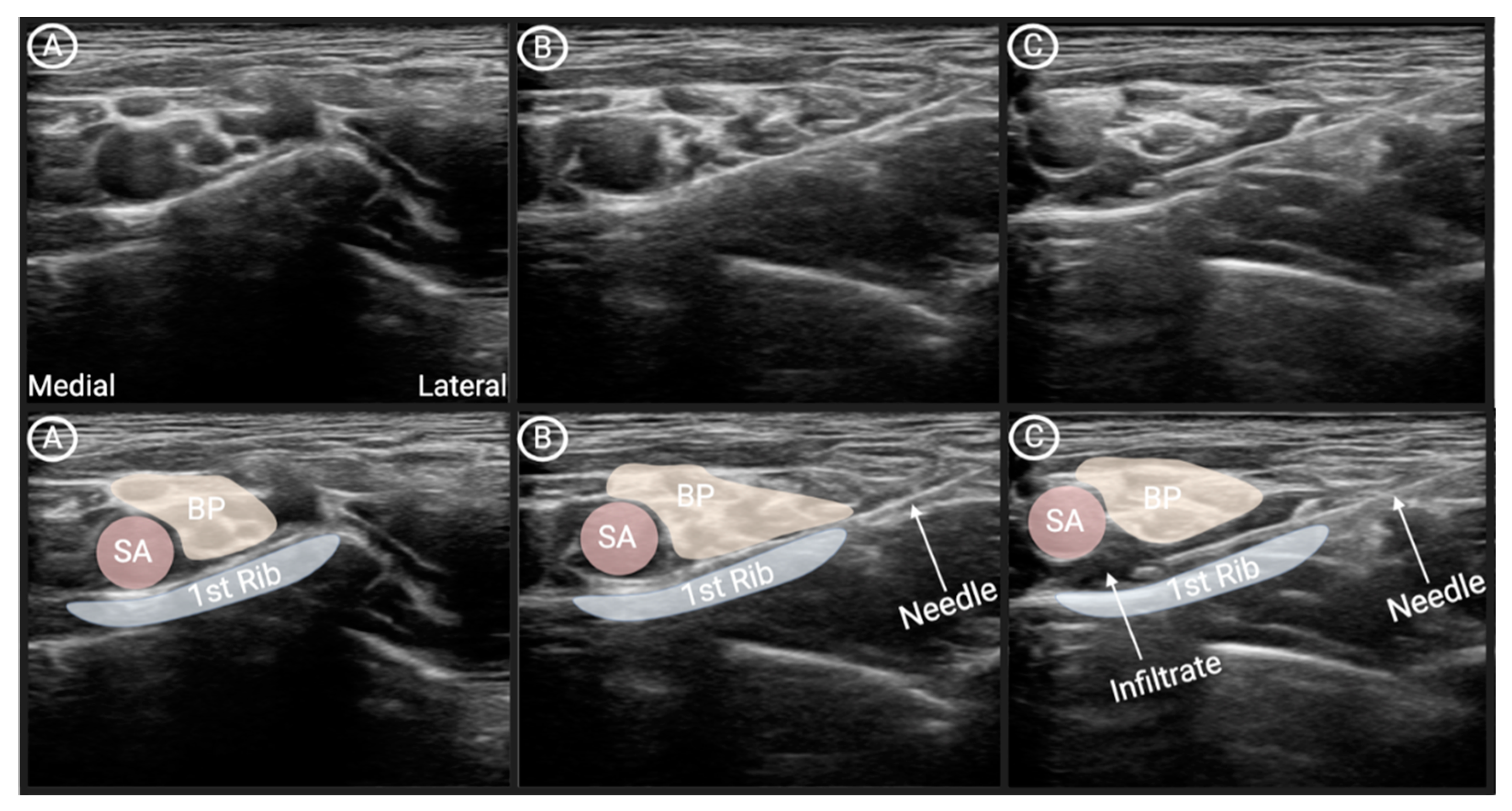

Ultrasound Imaging: An ultrasound probe is placed on the patient's skin just above the clavicle to visualize the brachial plexus, which appears as a "cluster of grapes" at the root or trunk level. The brachial plexus lies adjacent to the subclavian artery and the first rib (

Figure 3).

Needle Insertion: After identifying the correct anatomy, a fine needle is inserted in-plain, under real-time ultrasound guidance. The needle is advanced toward the brachial plexus, from lateral to medial, with the goal of depositing the local anesthetic medication near the nerve trunks, next to the subclavian artery, and 1st rib [

12].

Anesthetic Injection: The maximal amount of anesthetic should be calculated using a dosing calculator, usually from 10-20 ml. 1% lidocaine is the usual anesthetic agent of choice for this type of reduction in the ED. The time of effect of lidocaine is usually 1-2 hours allowing enough time to perform reduction, splinting, immobilization and x-rays. The short duration of action permits performing neurologic exam of the extremity following reduction. [

13,

14].

3. Results

3.1. Patient One

An 11-year-old male with a past medical history of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder presented to the ED after suffering a fall of approximately 25 feet from a rock-climbing wall onto a rubberized floor due to equipment failure. He landed on an outstretched left arm and struck his forehead, with no loss of consciousness.

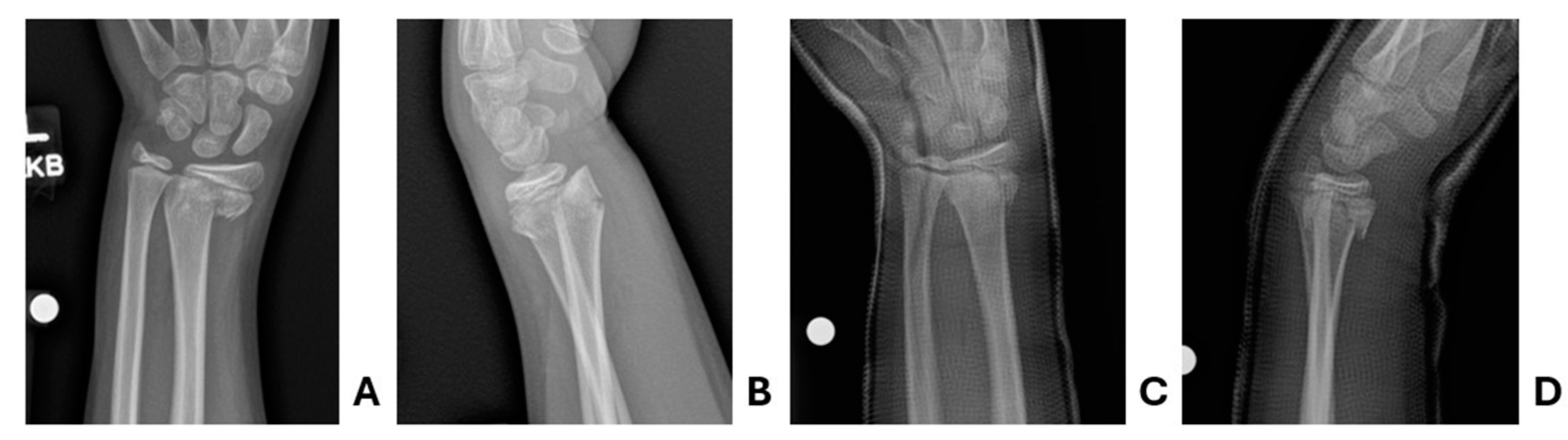

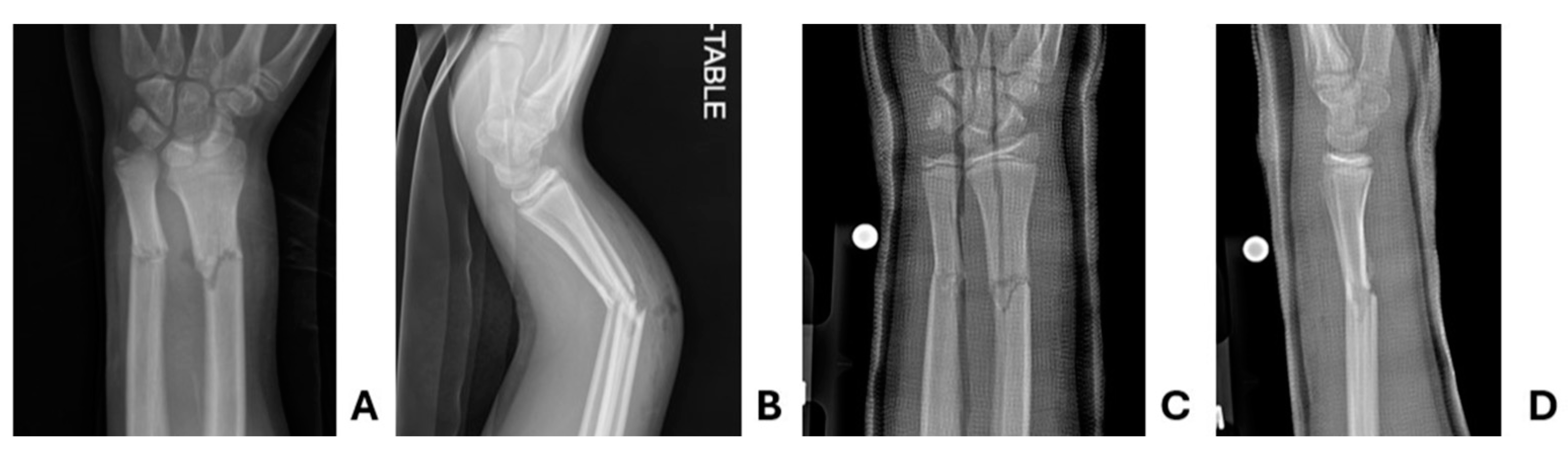

In the ED, the patient was found to have an obvious deformity with accompanying tenderness and mild swelling of the left wrist. He was neurovascularly intact distally. It was a closed injury without violation of the skin. Full trauma assessment was performed given the mechanism of injury and notable for a small forehead hematoma indicating head trauma. X-rays of the left wrist, radius, and ulna were obtained. Given a normal neurologic examination, no signs of a basilar skull fracture, and no altered mental status, computed tomography of the head was deferred. X-ray imaging was subsequently notable for an acute, displaced, mildly angulated fracture of the distal left radial metaphysis with extension into the physis, Salter-Harris type II (

Figure 4).

Orthopedics was consulted, recommending reduction and immobilization with cast placement. Given the severe mechanism of injury, close observation and serial neurological examinations were favored over advanced imaging of the head. To facilitate the need for close observation and orthopedic reduction, the decision was made to perform supraclavicular nerve block over procedural sedation. This was preferred as the team wished to closely observe Glasgow Coma Scale, while not delaying care of his distal radius fracture. Ultimately, supraclavicular block was performed without complications. He was provided an additional 50 mcg of fentanyl for analgesia during the closed reduction, which was performed successfully on the first attempt. Biplanar fluoroscopy and post-reduction x-rays confirmed appropriate reduction before the patient was placed in a bivalved, long-arm, fiberglass cast. There were no procedural complications. Following an appropriate observation for his head injury, he was discharged with plans to follow-up with Orthopedics in one week for repeat radiographs. X-rays obtained during follow-up 1, 2, and 3 weeks later demonstrated stable alignment of the fracture site.

3.2. Patient Two

12-year-old male presented to the ED with an obvious deformity of the left arm following a dirt bike crash. Past medical history was notable for a Salter Harris type two distal radius fracture treated with casting one year prior. The patient was operating a dirt bike at speeds of approximately 15 miles per hour when he lost control. The patient was helmeted and there was no loss of consciousness. Immediately following the crash, the patient was found to have an obvious deformity of the left arm, reporting 9/10 pain in the extremity. Intravenous access was obtained by EMS and he was initially provided 50 mcg fentanyl before a splint was applied and his arm was rested on a pillow. In the pre-hospital setting, the patient was provided two additional doses of 25 mcg of fentanyl, over 30 minutes.

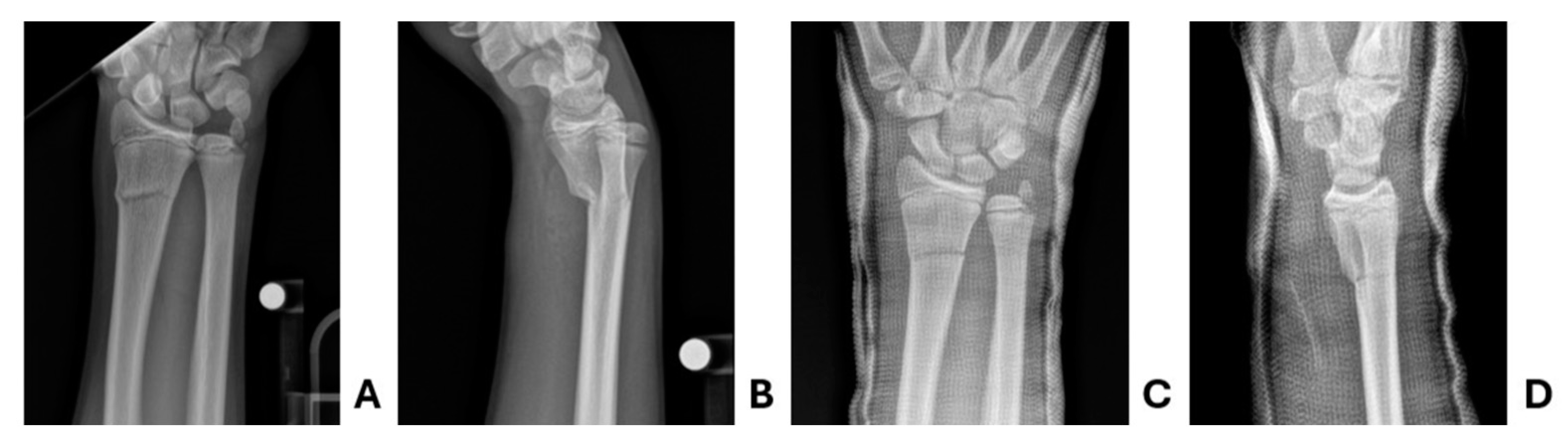

Upon arrival to the ED, he was hemodynamically stable. Examination was notable for deformity of the left forearm with a 1-2 mm open wound overlying the site. Distal perfusion, motor function, and sensation were intact. There was no concern for other injury about the remainder of his body. X-rays of the left radius and ulna were obtained and notable for an apex dorsal angulated radius and ulna diaphysis fractures (

Figure 5). Pediatric Orthopedics was consulted and recommended irrigation and closed reduction. In the ED, he was provided another two doses of 50 mcg of fentanyl, for a total of 200 mcg over 90 minutes. In light of his analgesia requirements, it was decided to facilitate the procedure with a supraclavicular block. This was performed without complications. He subsequently underwent irrigation of the puncture site before a bivalved long arm cast was placed. Post-reduction x-rays confirmed adequate length, alignment, and rotation. No further analgesic doses were required during his ED stay. X-rays obtained during follow-up 1, 3, and 6 weeks later demonstrated stable alignment of the fracture site. He was not felt to need any further follow-up and was cleared from this injury.

3.3. Patient Three

14-year-old male presented to the ED with right wrist pain following an injury sustained at hockey practice when he was checked into the boards. He did not sustain any head trauma or any other injuries at that time. In the ED, the patient was noted to have an obvious deformity of the right upper extremity with tenderness overlying the wrist. He was neurovascularly intact. X-ray of the right radius and ulna were notable for a distal radius fracture, >20 degrees of angulation (

Figure 6). Orthopedics was consulted and recommended non-operative management with closed reduction and casting. Procedural sedation was the initial method discussed with his family, though his family continued to feel uncomfortable with the potential risks of complication and need for monitoring. Supraclavicular block was performed to facilitate bedside reduction and long arm casting. He was subsequently followed at an outside Sports Medicine facility, locally. X-rays obtained during follow-up 10 days and 27 days later demonstrated appropriate alignment and robust healing response, respectively. He was felt to make a complete clinical recovery from his distal radius and ulna fractures and encouraged to follow-up on an as-needed basis.

4. Discussion

Procedural sedation is widely recognized as the standard of care over regional anesthesia when performing bedside reduction and immobilization of distal forearm fractures in pediatric emergency departments. A critical deciding factor of anxiolytic, analgesic, and anesthetic agent is the overall quality of sedation and pain control required to achieve adequate reduction and avoid the ultimate need for surgical intervention. A systematic review and meta-analysis conducted in 2016 analyzed 13,883 procedural sedations in children under 18, found the most common adverse events were vomiting, agitation, hypoxia, and apnea. Laryngospasm was reported in 2.9 per 1,000 sedations and intubation was reported in 4 cases out of 9,136 sedations [

5]. To facilitate a safe sedation, clinicians commonly consider the fasting recommendations from the American Society of Anesthesiologists [

15]. However, the American College of Emergency Physicians have recommended that clinicians do not delay PS in ED patients, as the duration of fasting did not reduce a patients risk for aspiration or emesis [

16]. A prospective cohort of 2,497 children who underwent PS in an ED, found no increased risk of these adverse events in patients who met the preprocedural fasting recommendations from the American Society of Anesthesiologists, compared to those who did not [

17]. Considering these factors and small risk for adverse events, procedural sedation remains the preferred method for reduction in the ED.

Regional anesthesia, such as ultrasound-guided supraclavicular nerve blocks, are a well-known alternative or adjunct to procedural sedation, having been implemented in the operating room and adult population in the ED. However, its use in the pediatric ED remains underutilized. There are abundant studies in the literature which demonstrate that regional anesthesia is a safe and effective alternative for reduction of orthopedic emergencies in adults, though pediatric patients are commonly excluded. Stone et al. in 2007 presented a case series of adult patients who found successful treatment and analgesia from supraclavicular block with abscess, metacarpal fracture, two midshaft humerus fractures, and a posterior elbow dislocation [

18]. One of the primary limitations of regional anesthesia is the effectiveness of analgesia. Given the technical skill required to perform regional anesthesia, there may be cases where incomplete analgesia is achieved secondary to the accuracy of the block. We described three cases where supraclavicular block provided excellent analgesia and successful reduction of a distal radius fracture on the first attempt. In cases where incomplete regional block is achieved, clinicians may consider providing additional local anesthesia with a hematoma block.

Considering the wide variety of patients that present to the ED, it is important to have alternatives to fit various clinical scenarios. This case series highlights that supraclavicular nerve block holds potential to provide safe and effective analgesia for orthopedic emergencies without compromising the quality of reduction. Benefits of supraclavicular block over procedural sedation include the avoidance of potential respiratory depression, no indication for intravenous access or continuous cardiac monitoring, and shorter recovery phase. Although limited by sample size, length of stay was shorter for patients who underwent supraclavicular compared to procedural sedation, without impacting satisfaction scores [

10]. Risks of complications from supraclavicular block include nerve injury, inadvertent vascular puncture, pneumothorax, and diaphragmatic paralysis. With the potential risk for diaphragmatic paralysis, clinicians should be diligent in assessing for underlying pulmonary disease. A previous systematic review and meta-analysis found overall low incidence of complications and no patients experienced diaphragmatic paralysis requiring ventilatory support [

19]. As underlying pulmonary disease is less common in the pediatric population, supraclavicular nerve block serve as an excellent alternative for patients who are not nothing by mouth (NPO), when there is parental concern for sedation complication, and in children who are likely to cooperate.

The use of ultrasound guidance for anatomic structure identification and direct needle visualization significantly improves safety and precision. A prospective study comparing landmark-based techniques to ultrasound-guided supraclavicular nerve blocks demonstrated a respective increase in success rate from 85% to 95% [

20].

Supraclavicular nerve blocks provide a promising alternative to procedural sedation for pediatric distal radius fracture reductions, maintaining appropriate analgesia while reducing the risk of sedation-related adverse events. Commonly utilized for regional anesthesia in the pediatric operating room, this technique has been demonstrated to provide adequate analgesia with high levels of patient, parent, and provider satisfaction [

21]. Our cases demonstrate three clinical scenarios where supraclavicular nerve blocks were successfully used to facilitate reduction of distal radius fractures in pediatric patients. In a case of an open fracture with the need for opioid for analgesia, supraclavicular nerve blocks facilitated bedside irrigation, reduction, and immobilization. Additionally, supraclavicular nerve block allowed for continuous neurologic monitoring in a patient with a significant injury mechanism and need for monitoring. Lastly, using a multidisciplinary approach and shared decision making amongst emergency medicine providers, pediatric orthopedic providers, parents, and the patient, procedural sedation was avoided given significant concerns raised by the parents for the risks of complications and need for monitoring. These cases demonstrate that ultrasound-guided supraclavicular nerve blocks can be effectively implemented in the ED for pediatric patients, offering a viable alternative to procedural sedation while optimizing ED resource utilization.

5. Conclusions

Ultrasound-guided supraclavicular nerve blocks are an effective alternative to procedural sedation for forearm fracture management and immobilization in pediatric patients in the ED. This technique, well within the skillset of emergency medicine practitioners, provides adequate analgesia while reducing resource utilization and minimizing the risk of sedation-related adverse effects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.F.M. and S.M; methodology, D.F.M and J.K.; software, J.K., investigation, J.K. and D.F.M.; data curation, J.K., T.T, and D.F.M.; writing—original draft preparation, J.K., T.T., S.M., and D.F.M..; writing—review and editing, K.C., J.H., and D.F.M.; visualization, J.K.; supervision, D.F.M; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived as no identifying information was described. All patient data described was gathered retrospectively, in case series format.

Data Availability Statement

Data and results represented within the article available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ED |

Emergency Department |

| LOS |

Length of Stay |

References

- Naranje, S.M.; Erali, R.A.; Warner, W.C., Jr.; Sawyer, J.R.; Kelly, D.M. Epidemiology of Pediatric Fractures Presenting to Emergency Departments in the United States. J Pediatr Orthop. 2016, 36, e45–e48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gursanscky, J.; Kelly, A.M.; Hamad, A.; Tagg, A.; Klim, S.; Ritchie, P.; Law, I.; Krieser, D. Outcome of reduction of paediatric forearm fracture by emergency department clinicians. Emerg Med Australas. 2023, 35, 347–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putnam, K.; Kaye, B.; Timmons, Z.; Wade Shrader, M.; Bulloch, B. Success Rates for Reduction of Pediatric Distal Radius and Ulna Fractures. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2020, 36, e56–e60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, R.M.; Luhmann, J.D.; Luhmann, S.J. Emergency Department Management of Pain and Anxiety Related to Orthopedic Fracture Care: A Guide to Analgesic Techniques and Procedural Sedation in Children. Paediatr Drugs. 2004, 6, 11–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellolio, M.F.; Puls, H.A.; Anderson, J.L.; Gilani, W.I.; Murad, M.H.; Barrionuevo, P.; Erwin, P.J.; Wang, Z.; Hess, E.P. Incidence of adverse events in paediatric procedural sedation in the emergency department: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ open. 2016, 6, e011384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livingstone, J.; Opanova, M.; Beaman, A.; Radi, J.; Izuka, B. "You're O.K. Anesthesia": Closed Reduction of Displaced Pediatric Forearm and Wrist Fractures in the Office Without Anesthesia." J Pediatr Orthop. 2022, 42(10): 595-599.

- Saunders, R.; Davis, J.A.; Kranke, P.; Weissbrod, R.; Whitaker, D.K.; Lightdale, J.R. Clinical and economic burden of procedural sedation-related adverse events and their outcomes: analysis from five countries. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2018, 14, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuypers, M.I.; Veldhuis, L.I.; Mencl, F.; van Riel, A.; Thijssen, W.A.H.M.; Tromp, E.; Goslings, J.C.; Plötz, F.B. Procedural sedation and analgesia versus nerve blocks for reduction of fractures and dislocations in the emergency department: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians. 2023, 4, e12886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fauteux-Lamarre, E.; Burstein, B.; Cheng, A.; Bretholz, A. Reduced Length of Stay and Adverse Events Using Bier Block for Forearm Fracture Reduction in the Pediatric Emergency Department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2019, 35, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, M.B.; Wang, R.; Price, D.D. Ultrasound-guided supraclavicular brachial plexus nerve block vs procedural sedation for the treatment of upper extremity emergencies. Am J Emerg Med. 2008, 26, 706–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bendtsen T.F.; Lopez A.M.; Vandepitte C. Ultrasound-guided supraclavicular brachial plexus block in Hadzic's Textbook of Regional Anesthesia and Acute Pain Management. Hadzic A., Ed. McGraw-Hill Education. New York City, New York, U.S. 32.

- Chan, V.W.S.; Perlas, A.; Lupu, M. Ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia: Current concepts and techniques. Can J Anaesth. 2007, 54, 623–634. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B.S.; Kim, K.; Day, J.; Seilern Und Aspang, J.; Kim, J. Ultrasound-Guided Popliteal Nerve Block with Short-Acting Lidocaine in the Surgical Treatment of Ingrown Toenails. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021, 18, 5059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, P.N.; Aarons, L.J.; Bending, M.R.; Steiner, J.A.; Rowland, M. Pharmacokinetics of lidocaine and its deethylated metabolite: dose and time dependency studies in man. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1982, 10, 265–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The American Society of Anesthesiologists Committee. Practice Guidelines for Preoperative Fasting and the Use of Pharmacologic Agents to Reduce the Risk of Pulmonary Aspiration: Application to Healthy Patients Undergoing Elective Procedures: An Updated Report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Preoperative Fasting and the Use of Pharmacologic Agents to Reduce the Risk of Pulmonary Aspiration. Anesthesiology. 2017, 126, 376-393.

- Godwin, S. A.; Burton J.H.; Gerardo C.J.; Hatten B.W.; Mace S.E.; Silvers S.M.; Fesmire F.M.; American College of Emergency Physicians. Clinical policy: procedural sedation and analgesia in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2014, 63, 247–58.

- Roback, M.G.; Bajaj, L.; Wathen, J.E.; Bothner, J. Preprocedural fasting and adverse events in procedural sedation and analgesia in a pediatric emergency department: are they related? Ann Emerg Med. 2004, 44, 454–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, M.B.; Price, D.D.; Wang, R. Ultrasound-guided supraclavicular block for the treatment of upper extremity fractures, dislocations, and abscesses in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2007, 25, 472–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casas-Arroyave F.D.; Ramírez-Mendoza E.; Ocampo-Agudelo A.F. Complications associated with three brachial plexus blocking techniques: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim (Engl Ed). 2021, 68, 392–407.

- Williams, S.R.; Chouinard, P.; Arcand, G.; Harris, P.; Ruel, M.; Boudreault, D.; Girard, F. Ultrasound guidance speeds execution and improves the quality of supraclavicular block. Anesth Analg. 2003, 97, 1518–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karagoz, S.; Tekin, E.; Aydin, M.E.; Turgut, M.C.; Yayik, A.M. Sedoanalgesia Versus Infraclavicular Block for Closed Reduction of Pediatric Forearm Fracture in Emergency Department: Prospective Randomized Study. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2021, 37, e324–e328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).