Submitted:

10 April 2025

Posted:

11 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

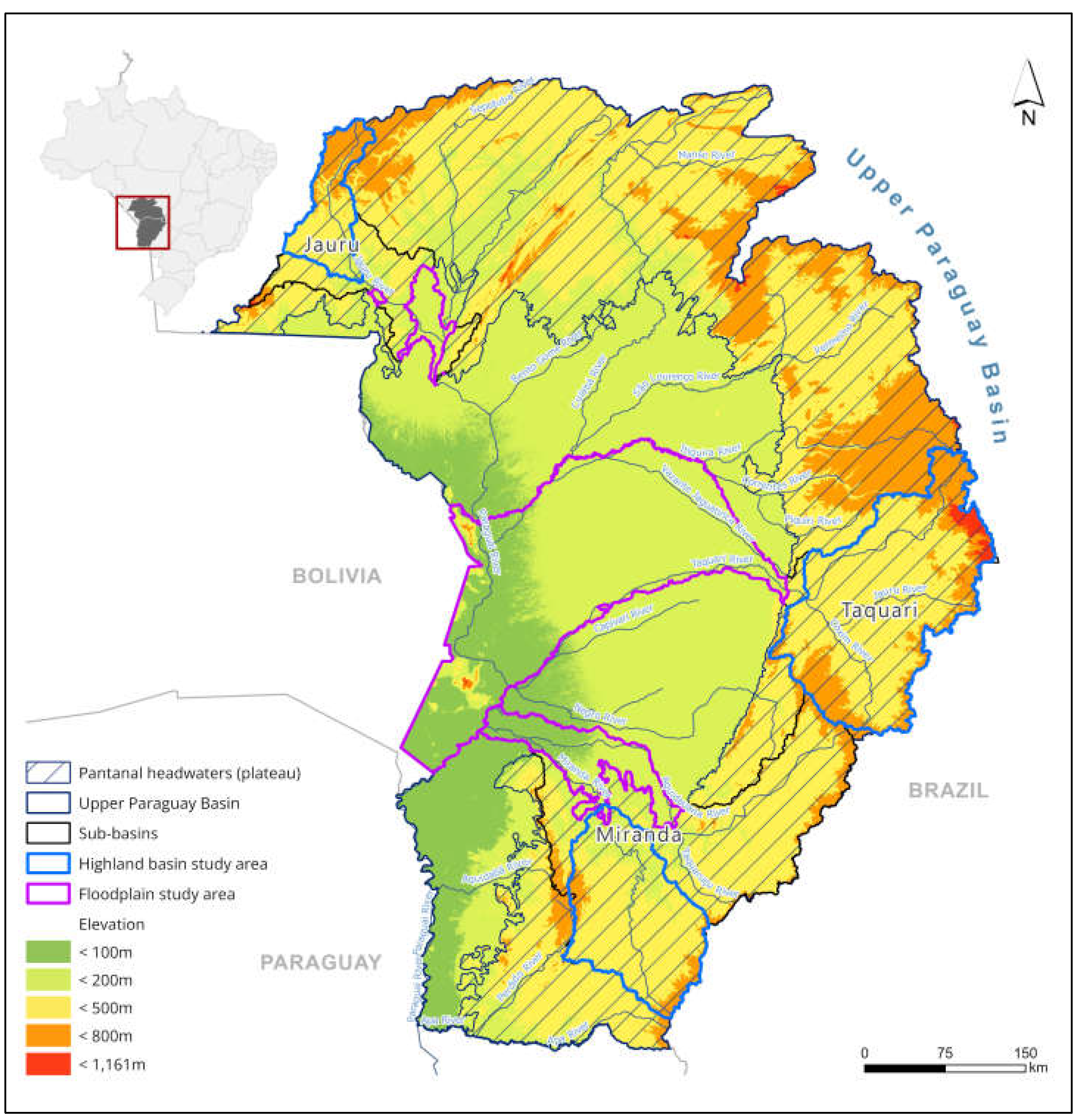

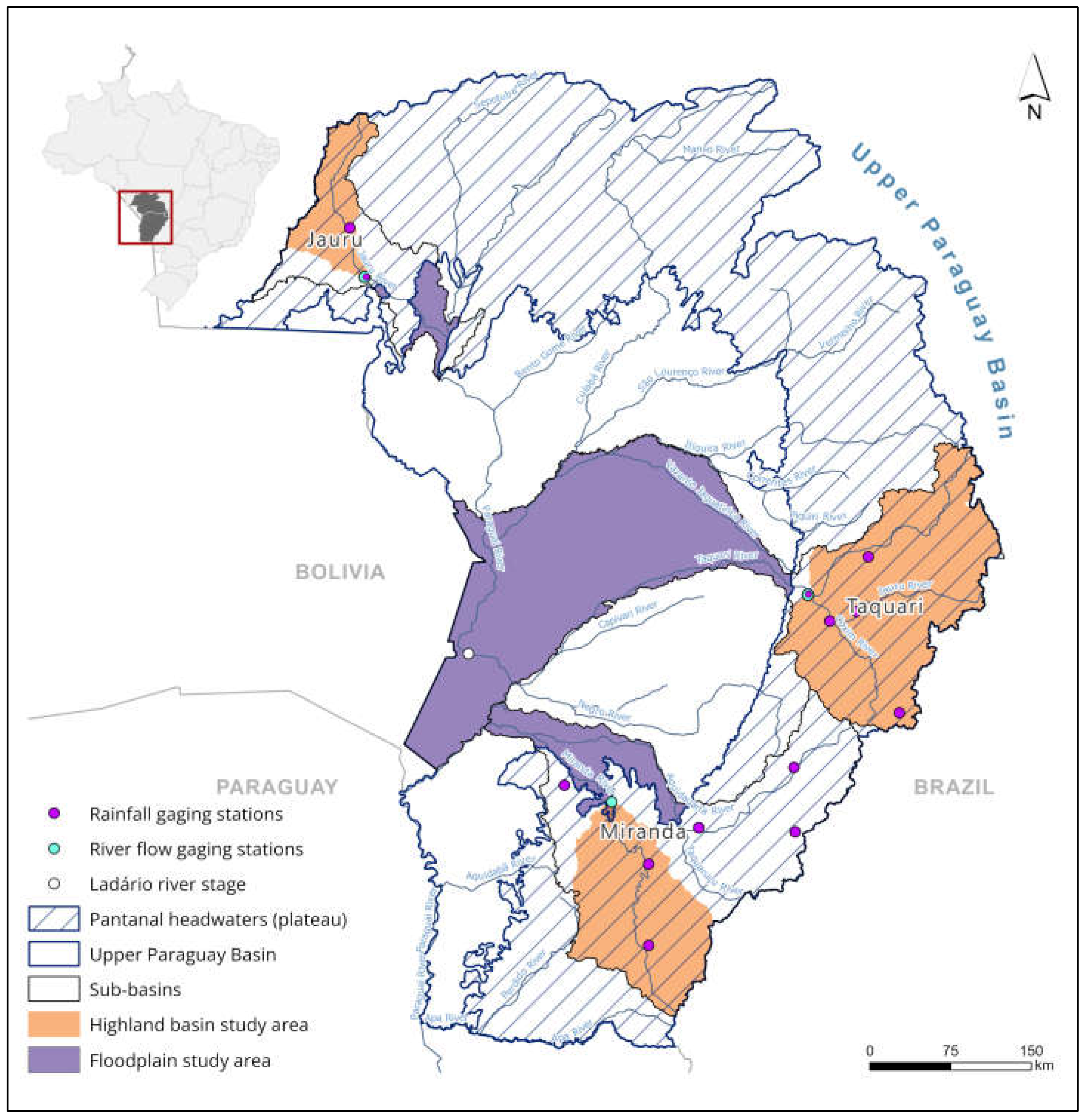

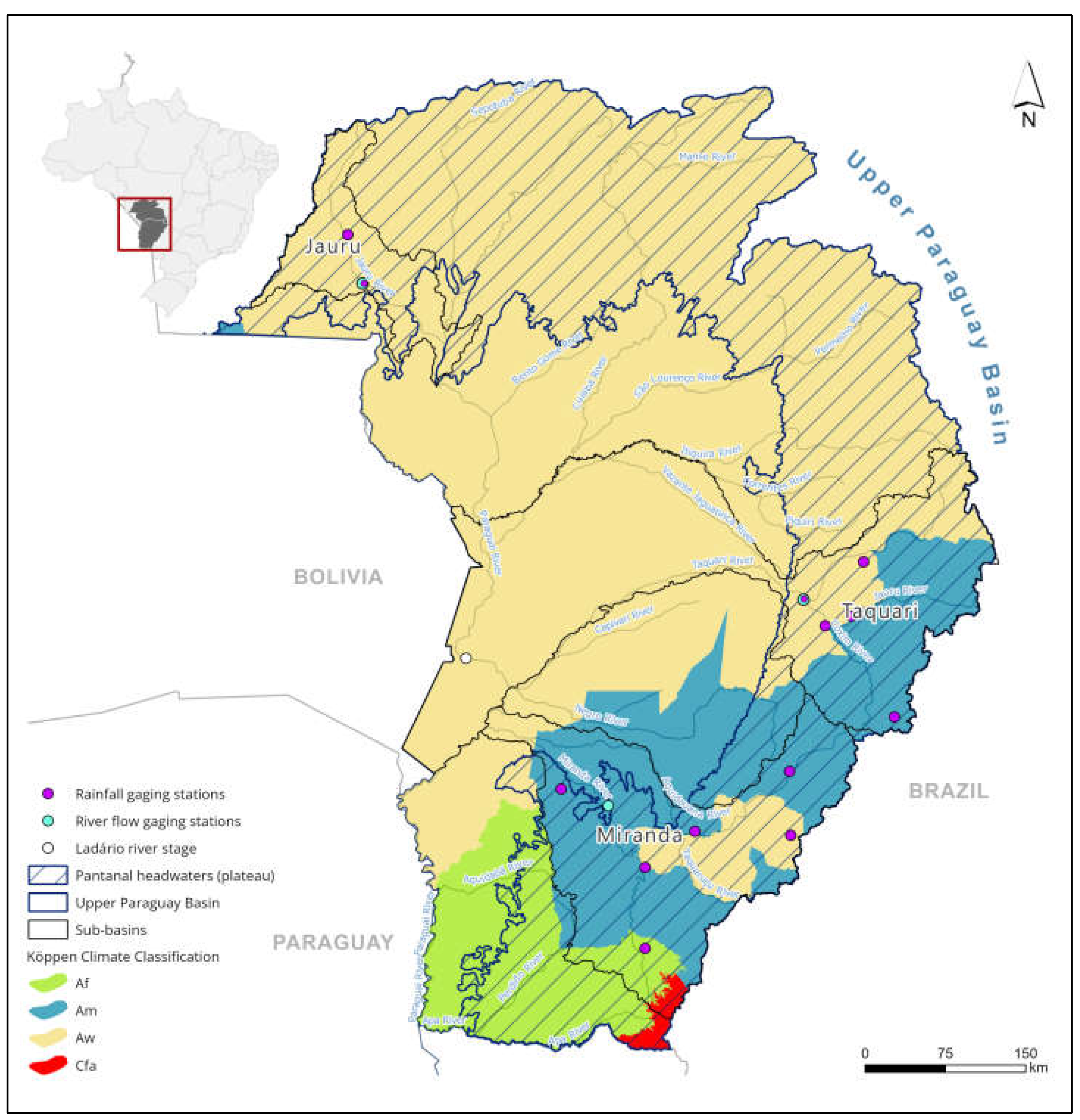

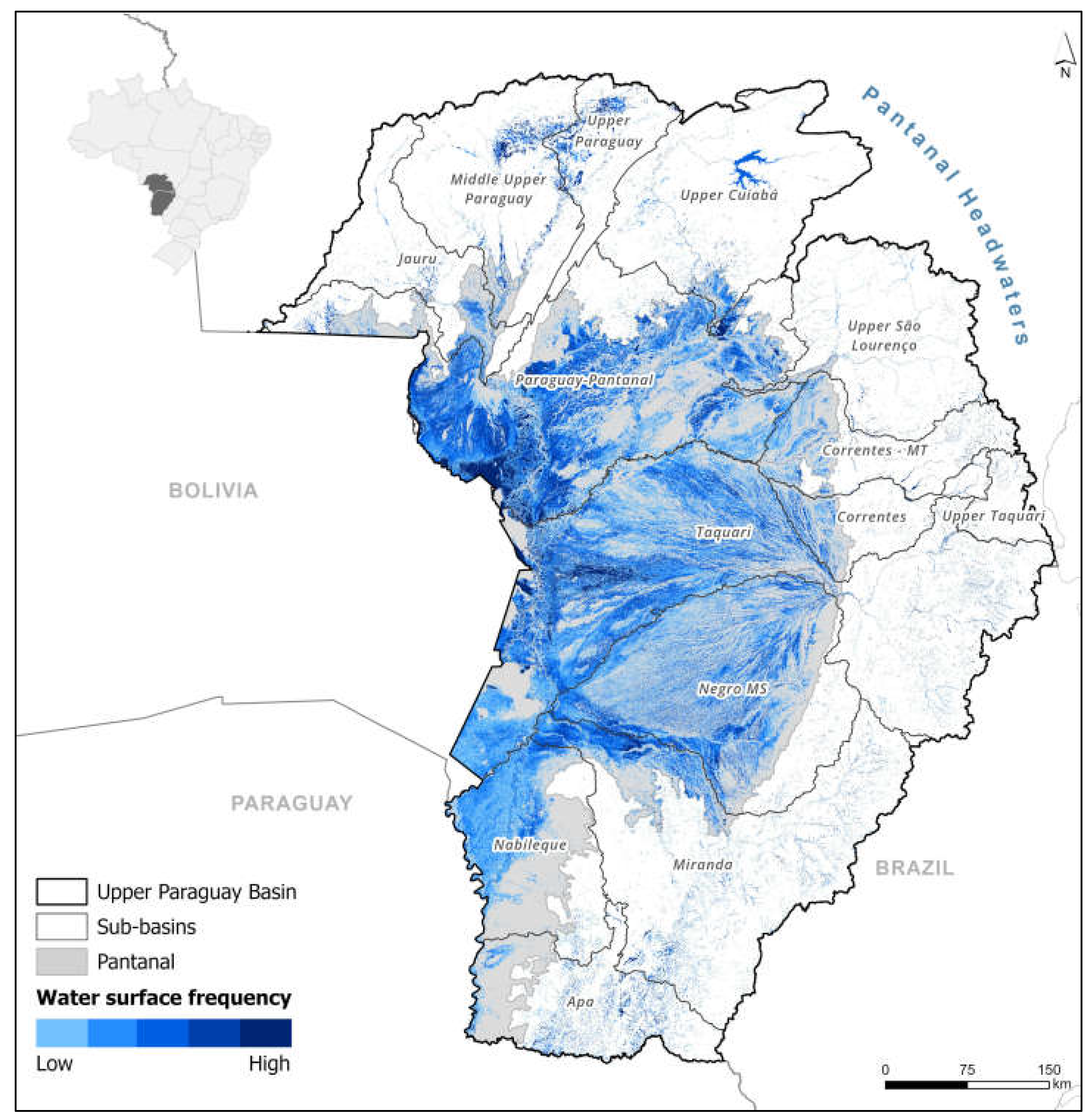

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data and Analyses

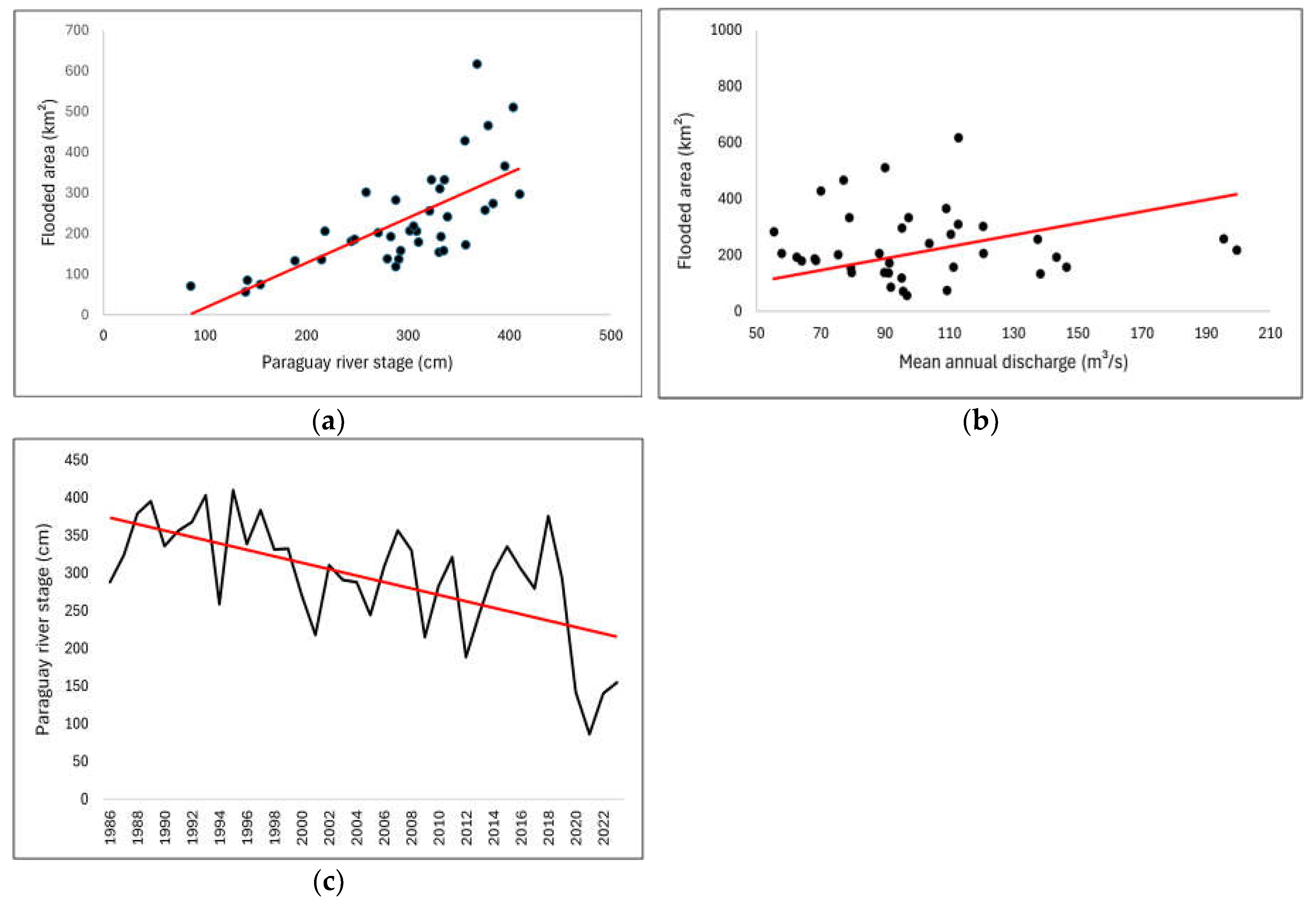

3. Results

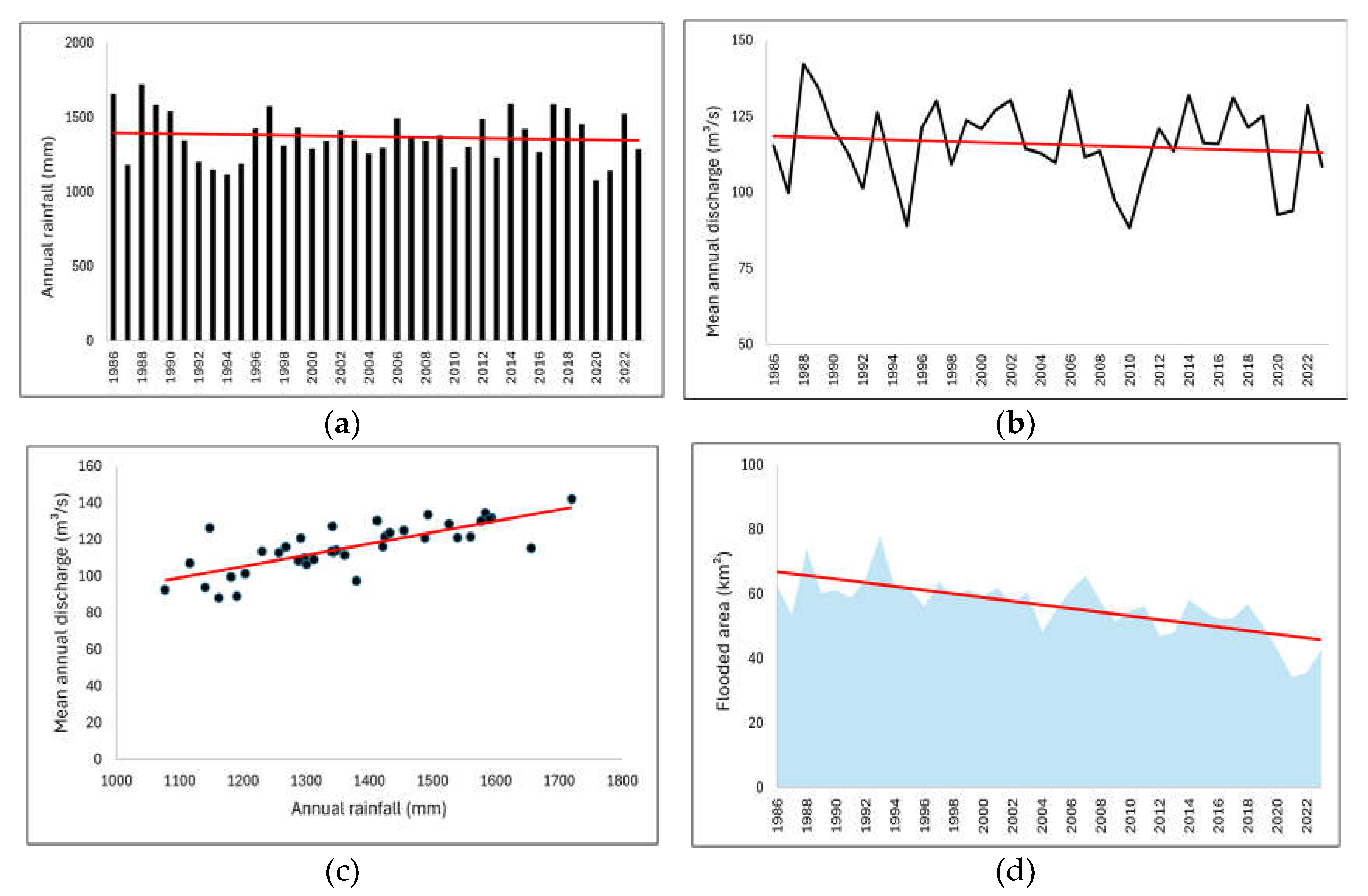

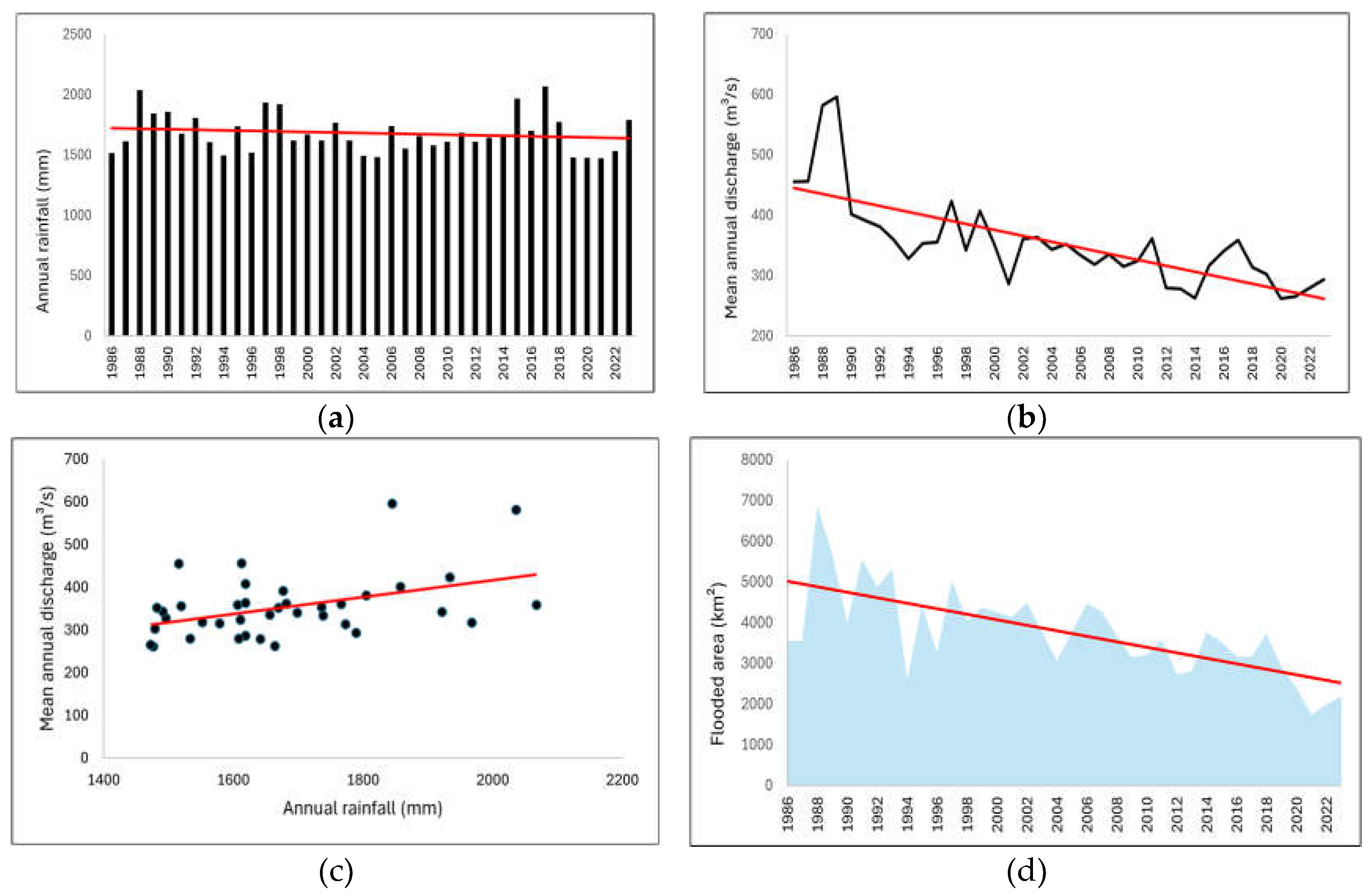

3.1. Jauru Basin (JB)

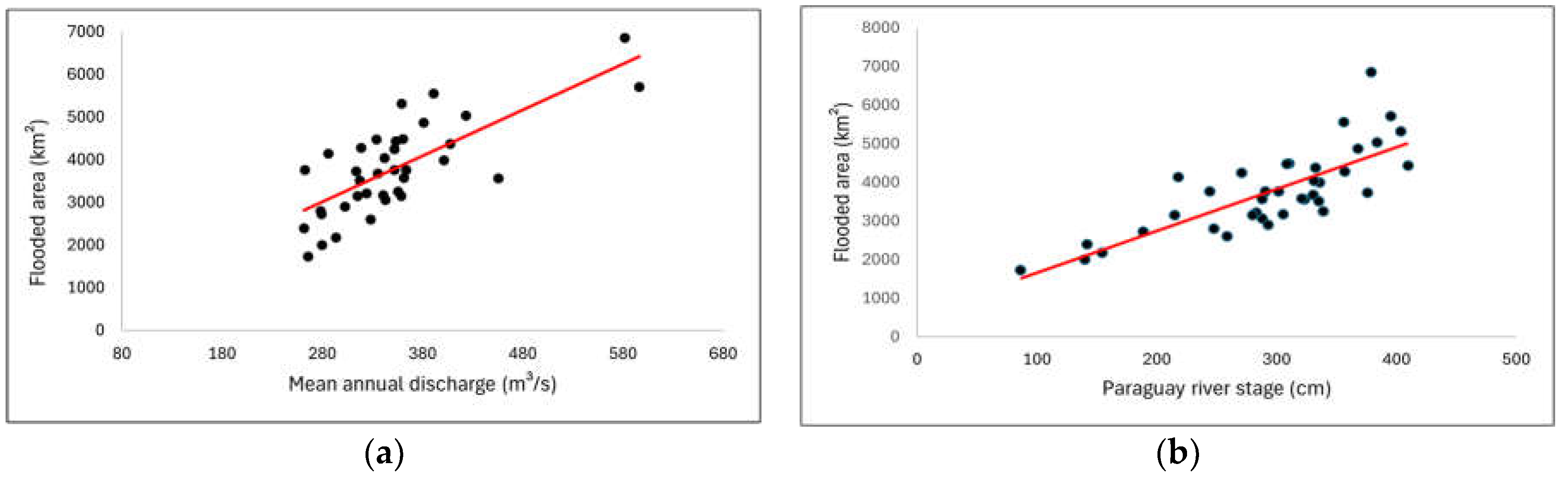

3.2. Taquari Basin (TB)

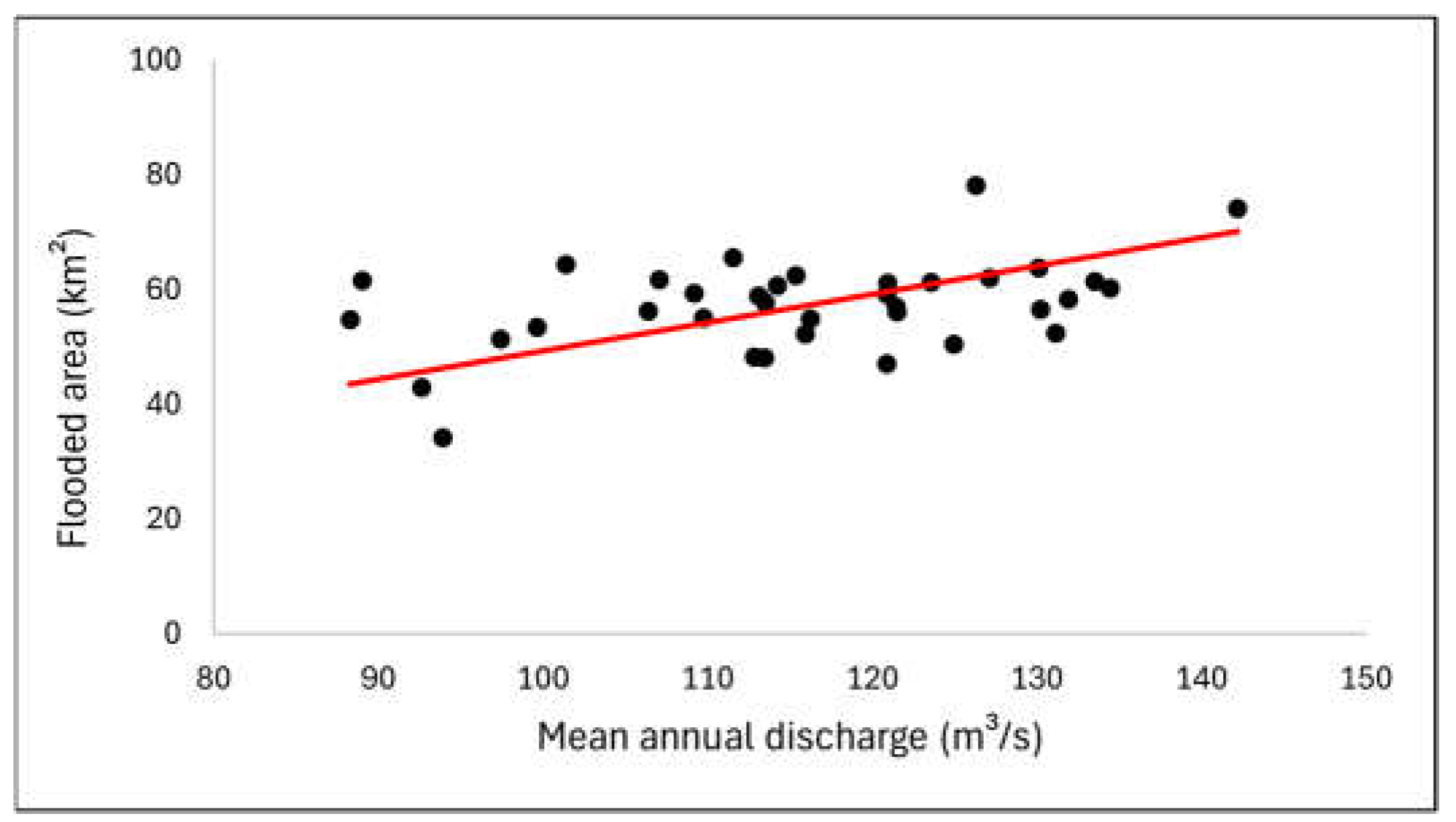

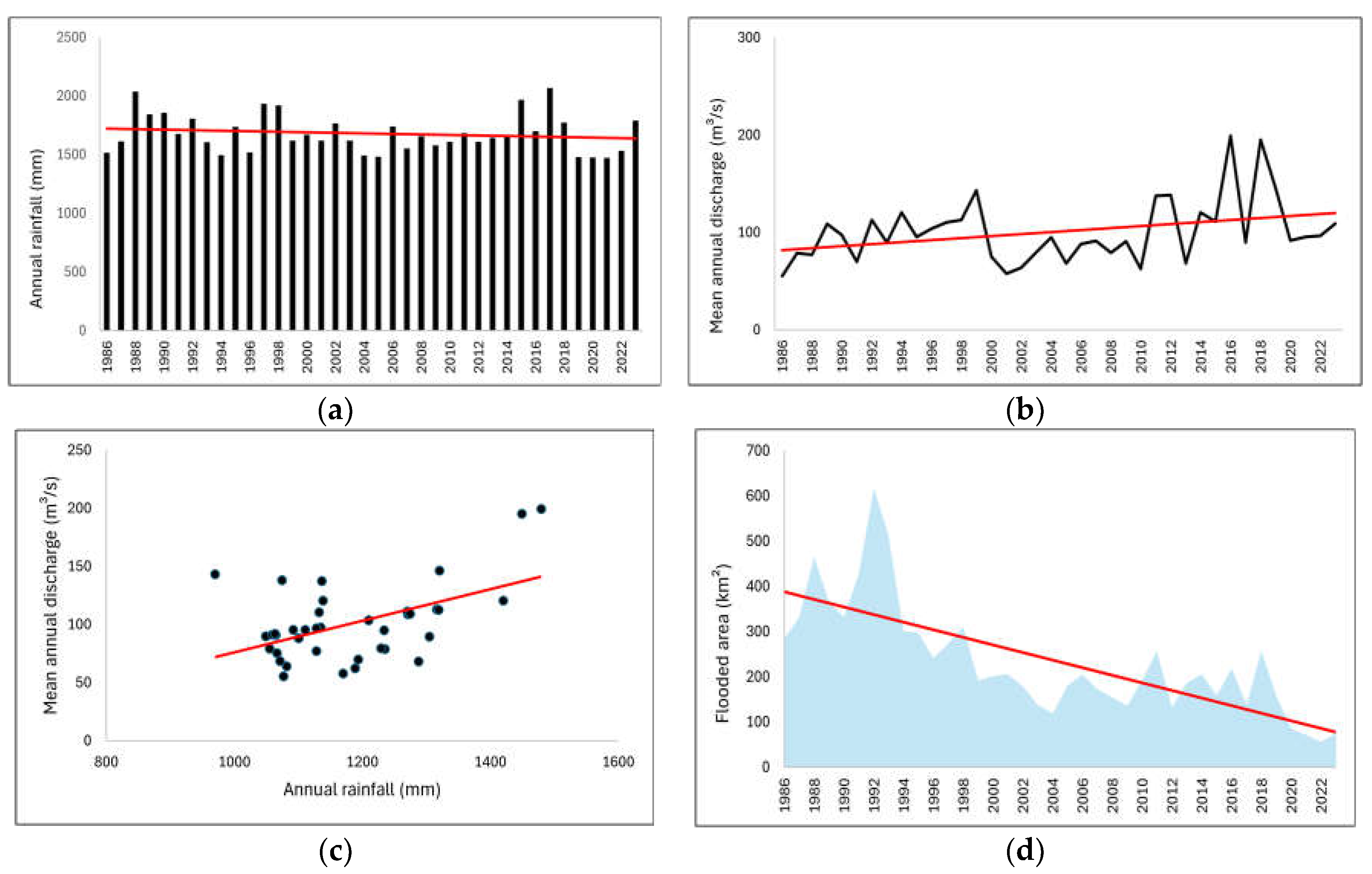

3.3. Miranda Basin (MB)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hao, Z.; Hao, F.; Singh, V.P.; Zhang, X. Changes in the Severity of Compound Drought and Hot Extremes over Global Land Areas. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libonati, R.; DaCamara, C.C.; Peres, L.F.; Sander de Carvalho, L.A.; Garcia, L.C. Rescue Brazil’s Burning Pantanal Wetlands. Nature 2020, 588, 217–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leal Filho, W.; Azeiteiro, U.M.; Salvia, A.L.; Fritzen, B.; Libonati, R. Fire in Paradise: Why the Pantanal Is Burning. Environ. Sci. Policy 2021, 123, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chagas, V.B.P.; Chaffe, P.L.B.; Blöschl, G. Climate and Land Management Accelerate the Brazilian Water Cycle. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feron, S.; Cordero, R.R.; Damiani, A.; MacDonell, S.; Pizarro, J.; Goubanova, K.; Valenzuela, R.; Wang, C.; Rester, L.; Beaulieu, A. South America Is Becoming Warmer, Drier, and More Flammable. Commun. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal-Riveros, C.; Currey, B.; McWethy, D.B.; Bieng, M.A.N.; Souza-Alonso, P. Spatiotemporal Analysis of Wildfires and Their Relationship with Climate and Land Use in the Gran Chaco and Pantanal Ecoregions. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 955, 176823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, A.M. How Do La Niña Events Disturb the Summer Monsoon System in Brazil? Clim. Dyn. 2004, 22, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ropelewski, C.H.; Halpert, M.S. Precipitation Patterns Associated with the High Index Phase of the Southern Oscilation. J. Clim. 2 1989, 268–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, H.M.L.; Lorena, D.R. Assessing Reservoir Reliability Using Classical and Long-Memory Statistics. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2019, 26, 100641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thielen, D.; Schuchmann, K.L.; Ramoni-Perazzi, P.; Marquez, M.; Rojas, W.; Quintero, J.I.; Marques, M.I. Quo Vadis Pantanal? Expected Precipitation Extremes and Drought Dynamics from Changing Sea Surface Temperature. PLoS One 2020, 15, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genta, J.L.; Perez-Iribarren, G.; Mechoso, C.R. A Recent Increasing Trend in the Streamflow of Rivers in Southeastern South America. J. Clim. 1998, 11, 2858–2862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; 2023.

- Hoffmann, W.A.; Jackson, R.B. Vegetation-Climate Feedbacks in the Conversion of Tropical Savanna to Grassland. J. Clim. 2000, 13, 1593–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debortoli, N.S.; Dubreuil, V.; Hirota, M.; Filho, S.R.; Lindoso, D.P.; Nabucet, J. Detecting Deforestation Impacts in Southern Amazonia Rainfall Using Rain Gauges. Int. J. Climatol. 2017, 37, 2889–2900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, J. de O.; Chaves, H.M.L. Trends and Variabilities in the Historical Series of Monthly and Annual Precipitation in Cerrado Biome in the Period 1977-2010. Rev. Bras. Meteorol. 2020, 35, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmona, Y.B.; Matricardi, E.A.T.; Skole, D.L.; Silva, J.F.A.; Coelho Filho, O. de A.; Pedlowski, M.A.; Sampaio, J.M.; Castrillón, L.C.R.; Brandão, R.A.; Silva, A.L. da; et al. A Worrying Future for River Flows in the Brazilian Cerrado Provoked by Land Use and Climate Changes. Sustain. 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, H.C.; Mercante, M.A.; Santos, E.T. Hydrological Cycle. Dict. Phys. Geogr. Fourth Ed. 2016, 71, 272–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tucci, C.E.M.; Clarke, R.T. Impact Og Changes in Vegetation Cover on Runoff: Review of Terrestrail Hydrological Cycle Processes. Global Cycle Description of Hydrological Processes in the Basin. 1997, 2, 135–152. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, P.T.; Nearing, M.A.; Moran, S.M.; Goodrich, D.C.; Wendland, E.; Gupta, H. V. Trends in Water Balance Components across the Brazilia Cerrado. 2014, 20, 7100–7114. [CrossRef]

- Bruijinzeel, L.A. Hydrology of Moist Tropical Forests and Effects of Conversion: A State of Knowledge Review; Paris, 1990.

- Blöschl, G. unte.; Ardoin-Bardin, S.; Bonell, M.; Dorninger, M.; Goodrich, D.; Gutknecht, D.; Matamoros, D.; Merz, B.; Shand, P.; Szolgay, J. At What Scales Do Climate Variability and Land Cover Change Impact on Flooding and Low Flows? Hydrol. Process 2007, 21, 1241–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marengo, J.A.; Tomasella, J.; Uvo, C.R. Trends in Streamflow and Rainfall in Tropical South America: Amazonia, Eastern Brazil, and Northwestern Peru. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1998, 103, 1775–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collischonn, W.; Tucci, C.E.M.; Clarke, R.T. Further Evidence of Changes in the Hydrological Regime of the River Paraguay: Part of a Wider Phenomenon of Climate Change? J. Hydrol. 2001, 245, 218–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, R.M. A Perspective on Nonstationarity and Water Management. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2011, 47, 436–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junk, W.J. The Flood Pulse Concept in River-Floodplain Systems. In Proceedings of the SIL Proceedings; 1922-2010; 1989; pp. 110–127. [Google Scholar]

- Poff, N.L.R.; Allan, J.D.; Bain, M.B.; Karr, J.R.; Prestegaard, K.L.; Richter, B.D.; Sparks, R.E.; Stromberg, J.C. The Natural Flow Regime: A Paradigm for River Conservation and Restoration. Bioscience 1997, 47, 769–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junk, W.J. Flood Pulsing and the Linkages between Terrestrial, Aquatic, and Wetland Systems. In Proceedings of the SIL Proceedings; 2005; Vol. 29 (1); pp. 11–38. [Google Scholar]

- Junk, W.J.; Da Cunha, C.N.; Wantzen, K.M.; Petermann, P.; Strüssmann, C.; Marques, M.I.; Adis, J. Biodiversity and Its Conservation in the Pantanal of Mato Grosso, Brazil. Aquat. Sci. 2006, 68, 278–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivory, S.J.; McGlue, M.M.; Spera, S.; Silva, A.; Bergier, I. Vegetation, Rainfall, and Pulsing Hydrology in the Pantanal, the World’s Largest Tropical Wetland. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergier, I. Effects of Highland Land-Use over Lowlands of the Brazilian Pantanal. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 463–464, 1060–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, J.M.; Collischonn, W.; da Paz, A.R.; Allasia, D.; Domecq, F. Impact of Projected Climate Change on Hydrologic Regime of the Upper Paraguay River Basin. Clim. Change 2014, 127, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite-Filho, A.T.; Soares-Filho, B.S.; Oliveira, U.; Coe, M. Intensification of Climate Change Impacts on Agriculture in the Cerrado Due to Deforestation. Nat. Sustain. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diffenbaugh, N.S.; Singh, D.; Mankin, J.S.; Horton, D.E.; Swain, D.L.; Touma, D.; Charland, A.; Liu, Y.; Haugen, M.; Tsiang, M.; et al. Quantifying the Influence of Global Warming on Unprecedented Extreme Climate Events. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2017, 114, 4881–4886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, P.; Mishra, A. Separating the Impacts of Climate Change and Human Activities on Streamflow: A Review of Methodologies and Critical Assumptions. J. Hydrol. 2017, 548, 278–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spracklen, D. V.; Arnold, S.R.; Taylor, C.M. Observations of Increased Tropical Rainfall Preceded by Air Passage over Forests. Nature 2012, 489, 282–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marengo, J.A. Variations and Change in South American Streamflow. Clim. Change 1995, 31, 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cigizoglu, H.K.; Bayazit, M.; Önöz, B. Trends in the Maximum, Mean, and Low Flows of Turkish Rivers. J. Hydrometeorol. 2005, 6, 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, S.K. Human Impacts on Hydrology in the Pantanal Wetland of South America. Water Sci. Technol. 2002, 45, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercante, M.A.; Rodrigues, S.C.; Ross, J.L.S. Geomorphology and Habitat Diversity in the Pantanal. Brazilian J. Biol. 2011, 71, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alho, C.J.R.; Sabino, J. Seasonal Pantanal Flood Pulse: Implications for Biodiversity Conservation – a Review. Oecologia Aust. 2012, 16, 958–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alho, C.J.R.; Silva, J.S.V. Effects of Severe Floods and Droughts on Wildlife of the Pantanal Wetland (Brazil)-a Review. Animals 2012, 2, 591–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roque, F.O.; Ochoa-Quintero, J.; Ribeiro, D.B.; Sugai, L.S.M.; Costa-Pereira, R.; Lourival, R.; Bino, G. Upland Habitat Loss as a Threat to Pantanal Wetlands. Conserv. Biol. 2016, 30, 1131–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, G.; Ramos, R. de C.; Rocha, L.C.; Brunsell, N.A.; Merino, E.R.; Mataveli, G.A.V.; Cardozo, F. da S. Rainfall Patterns and Geomorphological Controls Driving Inundation Frequency in Tropical Wetlands: How Does the Pantanal Flood? Prog. Phys. Geogr. 2021, 45, 669–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WWF Brazil Early Warning to Mitigate the Impacts of Drought in the Pantanal Available online: https://wwfbrnew.awsassets.panda.org/downloads/0107-nota-tecnica---crise-hidrica.pdf.

- Woodward, C.; Shulmeister, J.; Larsen, J.; Jacobsen, G.E.; Zawadzki, A. The Hydrological Legacy of Deforestation on Global Wetlands. Science (80-. ). 2014, 346, 844–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Debortoli, N.; Dubreuil, V.; Funatsu, B.; Delahaye, F.; de Oliveira, C.H.; Rodrigues-Filho, S.; Saito, C.H.; Fetter, R. Rainfall Patterns in the Southern Amazon: A Chronological Perspective (1971–2010). Clim. Change 2015, 132, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, S.A. De; Matos, B.A.; Troger, F.H.; De, T.L.L. Stationarity Analysis of Streamflow Time Series at Paraguai Basin. In Proceedings of the XXII Simpósio Brasileiro de Recursos Hídricos; 2015; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Colman, C.B.; Oliveira, P.T.S.; Almagro, A.; Soares-Filho, B.S.; Rodrigues, D.B.B. Effects of Climate and Land-Cover Changes on Soil Erosion in Brazilian Pantanal. Sustain. 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assine, M.L.; Macedo, H.A.; Stevaux, J.C.; Bergier, I.; Padovani, C.R.; Silva, A. Avulsive Rivers in the Hydrology of the Pantanal Wetland. Handb. Environ. Chem. 2016, 37, 83–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvares, C.A.; Stape, J.L.; Sentelhas, P.C.; De Moraes Gonçalves, J.L.; Sparovek, G. Köppen’s Climate Classification Map for Brazil. Meteorol. Zeitschrift 2013, 22, 711–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudmundsson, L.; Bremnes, J.B.; Haugen, J.E.; Engen-Skaugen, T. Technical Note: Downscaling RCM Precipitation to the Station Scale Using Statistical Transformations – A Comparison of Methods. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2012, 16, 3383–3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcante, R.B.L.; Ferreira, D.B. da S.; Pontes, P.R.M.; Tedeschi, R.G.; da Costa, C.P.W.; de Souza, E.B. Evaluation of Extreme Rainfall Indices from CHIRPS Precipitation Estimates over the Brazilian Amazonia. Atmos. Res. 2020, 238, 104879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia Filho, W.L.F.; de Oliveira-Júnior, J.F.; da Silva Junior, C.A.; Santiago, D. de B. Influence of the El Niño–Southern Oscillation and the Sypnotic Systems on the Rainfall Variability over the Brazilian Cerrado via Climate Hazard Group InfraRed Precipitation with Station Data. Int. J. Climatol. 2022, 42, 3308–3322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WMO Calculation of Monthly and Annual 30-Year Standard Normals; Ginebra, Switzerland, 1989.

- Dahmen, E.R.; Hall, M.J. Screening of Hydrological Data: Tests for Stationarity and Relative Consistency; International Institute for Land Reclamation and Improvement/ILRI: Wangeningen, 1990; ISBN 9070754231. [Google Scholar]

- Salas, J.D. Analysis and Modeling of Hydrologic Time Series. In Handbook of Hydrology; Maidmend, D.R., Ed.; New York, 1992; pp. 19.1-19.72.

- Libiseller, C.; Grimvall, A. Performance of Partial Mann-Kendall Tests for Trend Detection in the Presence of Covariates. Environmetrics 2002, 13, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, H.E.A. A Suggested Statistical Model of Some Time Series Which Occur in Nature 1956.

- Chandrasekaran, S.; Poomalai, S.; Saminathan, B.; Suthanthiravel, S.; Sundaram, K.; Abdul Hakkim, F.F. An Investigation on the Relationship between the Hurst Exponent and the Predictability of a Rainfall Time Series. Meteorol. Appl. 2019, 26, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandelbrot, B. & Wallis, J. Range R / S in the Measurement Long Run Statistical Dependence. Water Resour. Res. 1969, 5, 967–988. [Google Scholar]

- Mirza, M.Q.; Warrick, R.A.; Ericksen, N.J.; Kenny, G.J. Tendances et Persistance Des Précipitations Des Bassins Des Fleuves Gange, Brahmapoutre et Meghna. Hydrol. Sci. J. 1998, 43, 845–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatli, H. Detecting Persistence of Meteorological Drought via the Hurst Exponent. Meteorol. Appl. 2015, 22, 763–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SALAS, J.D. Analysis and Modeling of Hydrologic Time Series; New York, USA, 1992.

- Yue, S.; Pilon, P.; Cavadias, G. Power of the Mann-Kendall and Spearman’s Rho Tests for Detecting Monotonic Trends in Hydrological Series. J. Hydrol. 2002, 259, 254–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevaux, J.C.; Macedo, H. de A.; Assine, M.L.; Silva, A. Changing Fluvial Styles and Backwater Flooding along the Upper Paraguay River Plains in the Brazilian Pantanal Wetland. Geomorphology 2020, 350, 106906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marengo, J.A.; Oliveira, G.S.; Alves, L.M. Climate Change Scenarios in the Pantanal. Handb. Environ. Chem. 2016, 37, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S. Il; Wang, B. Interdecadal Change of the Structure of the ENSO Mode and Its Impact on the ENSO Frequency. J. Clim. 2000, 13, 2044–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, R.R.; Michael, J. McPhaden Why Did the 2011–2012 La Niña Cause a Severe Drought in the Brazilian Northeast? 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, W.; McPhaden, M.J.; Grimm, A.M.; Rodrigues, R.R.; Taschetto, A.S.; Garreaud, R.D.; Dewitte, B.; Poveda, G.; Ham, Y.G.; Santoso, A.; et al. Climate Impacts of the El Niño–Southern Oscillation on South America. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 215–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, H.M.L.; Lorena, D.R. Assessing Reservoir Reliability Using Classical and Long-Memory Statistics. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2019, 26, 100641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, M.C.S.; Rodriguez, D.A. Impacts of the Landscape Changes in the Low Streamflows of Pantanal Headwaters—Brazil. Hydrol. Process. 2022, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, A.R.; Bhattacharya, D. Effect of Short-Term Memory on Hurst Phenomenon. J. Hydrol. Eng 2001, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossman, N.D. Drought Resilience, Adaptation and Management Policy ( DRAMP ) Framework. Support. Tech. Guidel. 2018, 17. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).