Submitted:

10 April 2025

Posted:

11 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Direct Impact of Epilobium on the Vasculature

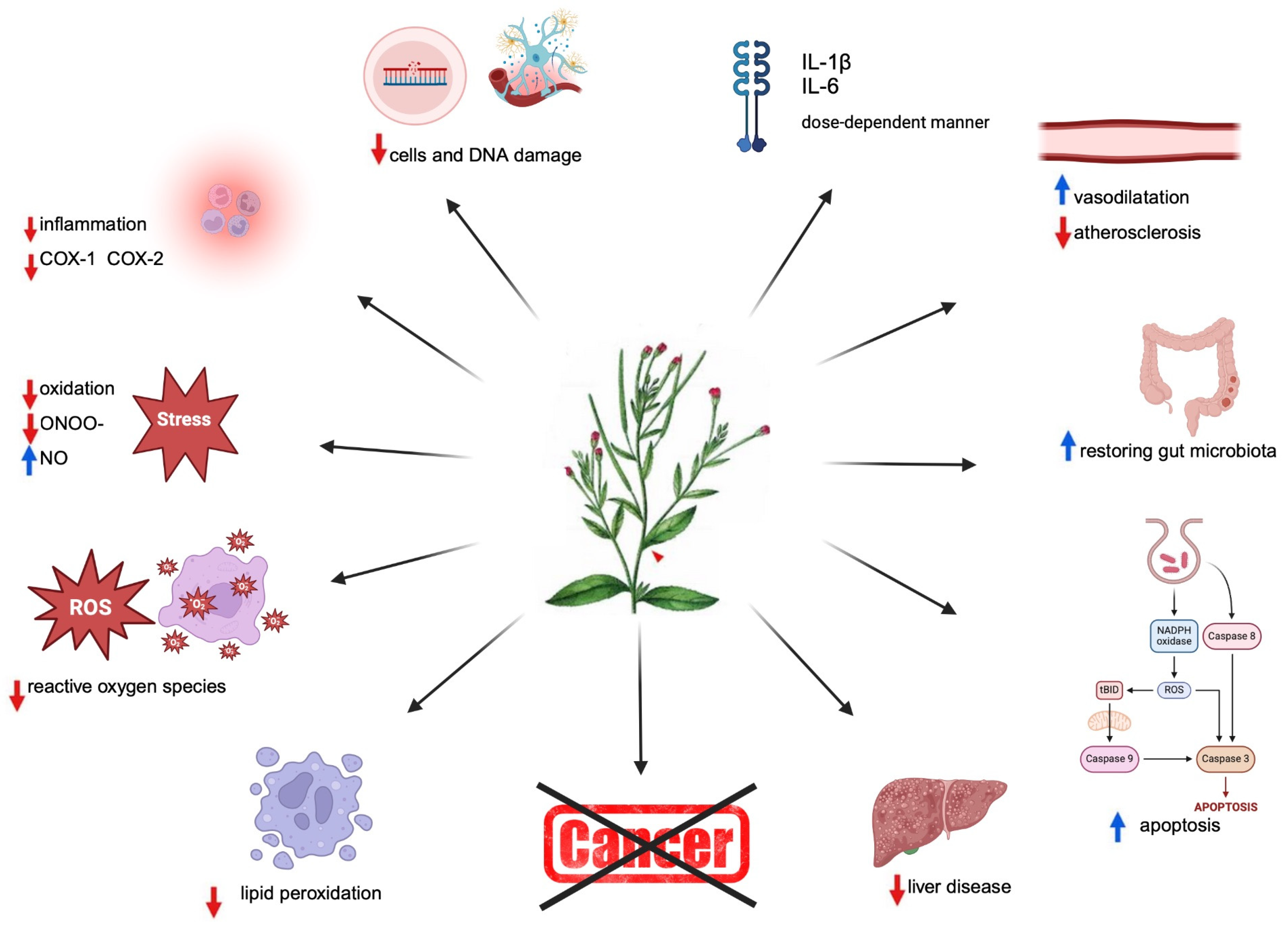

3.2. The Possible Impact of Epilobium on the Vasculature Based on its Properties

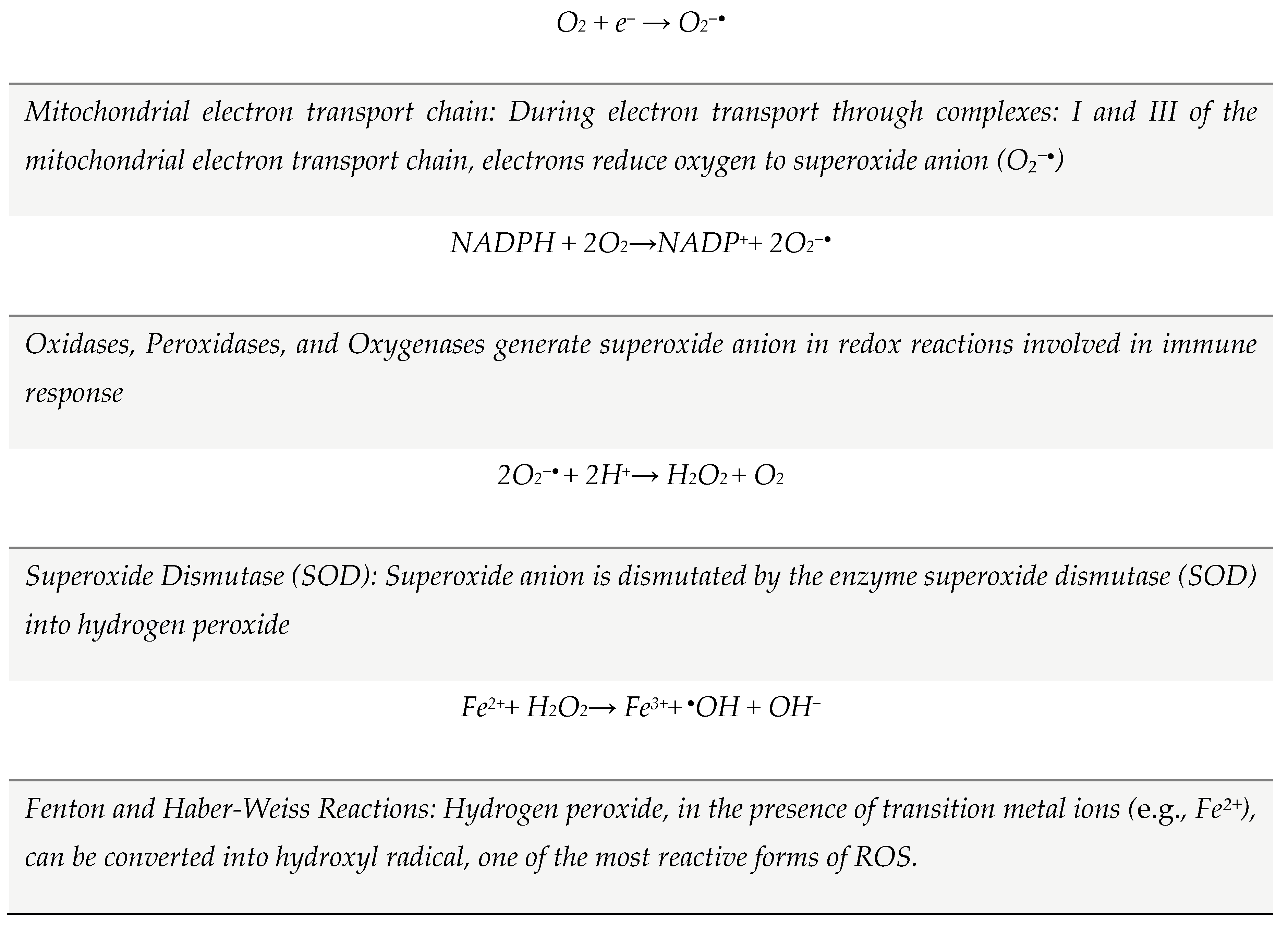

3.2.1. The Antioxidant and the Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Epilobium

3.2.2. The Impact of Epilobium on the Lipid Profile and Atherosclerotic Plaque Synthesis

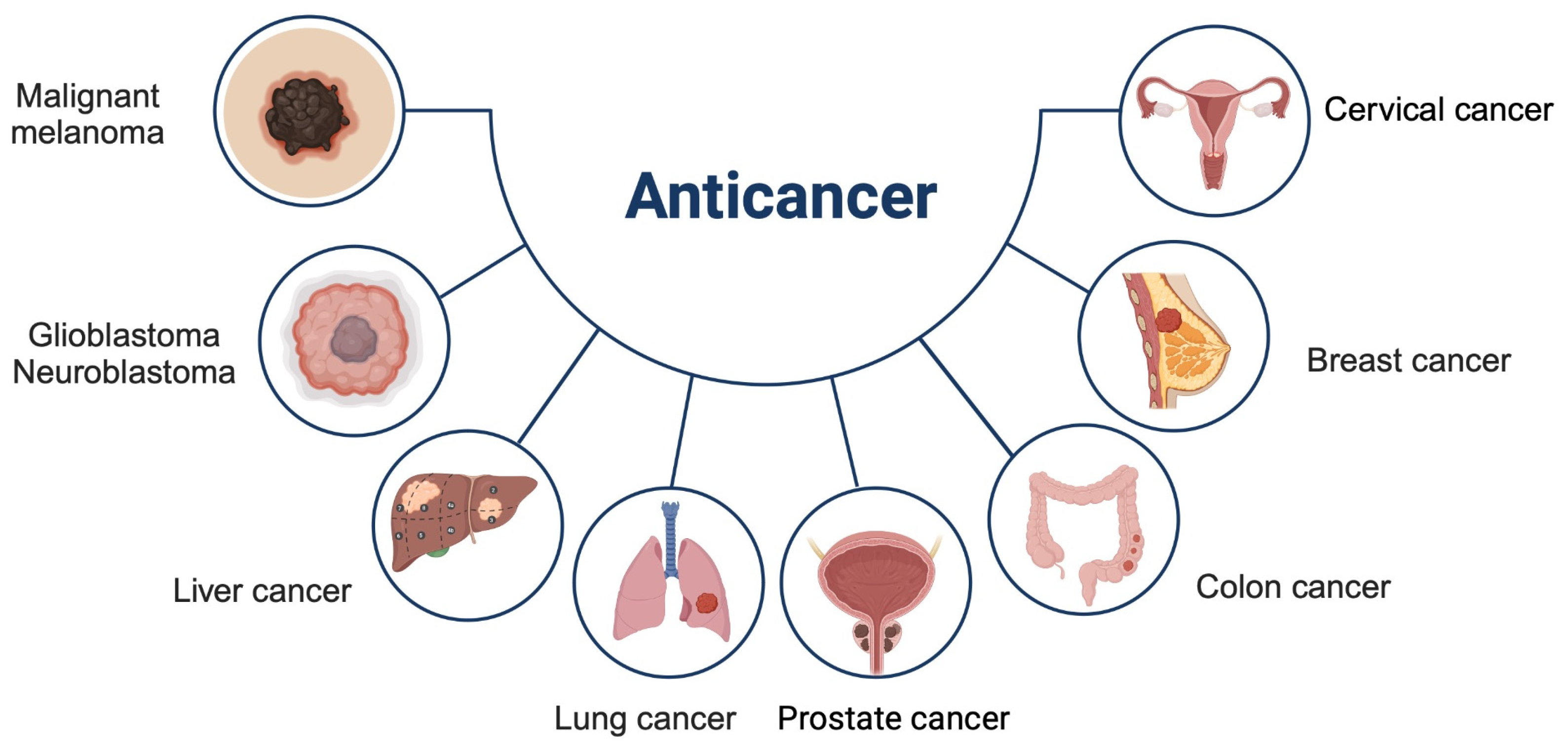

3.2.3. Anti Colorectal Cancer Activity

3.2.4. Other than Colorectal Cancer Activity

3.2.5. Nuclear factor (NF-κB)

3.2.6. Lymphocytes Cells and Interferons (IFNs)

3.2.7. Dendritic Cells

3.2.8. Brain Inflammation

3.2.10. Antimicrobial Activity

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Steenkamp, V.; Gouws, M.C.; Gulumian, M.; Elgorashi, E.E.; van Staden, J. Studies on antibacterial, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activity of herbal remedies used in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostatitis. J Ethnopharmacol 2006, 103, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbarossa, A.; Rosato, A.; Carocci, A.; Arpini, S.; Bosisio, S.; Pagni, L.; Piatti, D.; Spinozzi, E.; Angeloni, S.; Sagratini, G.; Zengin, G.; Cespi, M.; Maggi, F.; Caprioli, G. Efficacy of Willow Herb (Epilobium angustifolium L. and E. parviflorum Schreb.) Crude and Purified Extracts and Oenothein B Against Prostatic Pathogens. Antibiotics (Basel) 2025, 14, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Zong, W.; Tao, X.; Liu, S.; Feng, Z.; Lin, Y.; Liao, Z.; Chen, M. Evaluation of the therapeutic effect against benign prostatic hyperplasia and the active constituents from Epilobium angustifolium L. J Ethnopharmacol 2019, 232, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakaya, S.; Süntar, I.; Yakinci, O.F.; Sytar, O.; Ceribasi, S.; Dursunoglu, B.; Ozbek, H.; Guvenalp, Z. In vivo bioactivity assessment on Epilobium species: A particular focus on Epilobium angustifolium and its components on enzymes connected with the healing process. J Ethnopharmacol 2020, 262, 113207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolarczyk, M.; Naruszewicz, M.; Kiss, A.K. Extracts from Epilobium sp. herbs induce apoptosis in human hormone-dependent prostate cancer cells by activating the mitochondrial pathway. J Pharm Pharmacol 2013, 65, 1044–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevrenova, R.; Zengin, G.; Ozturk, G.; Zheleva-Dimitrova, D. Exploring the Phytochemical Profile and Biological Insights of Epilobium angustifolium L. Herb. Plants (Basel) 2025, 14, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, A.K.; Bazylko, A.; Filipek, A.; Granica, S.; Jaszewska, E.; Kiarszys, U.; Kośmider, A.; Piwowarski, J. Oenothein’s contribution to the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activity of Epilobium sp. Phytomedicine 2011, 18, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiermann, A.; Juan, H.; Sametz, W. Influence of Epilobium extracts on prostaglandin biosynthesis and carrageenin induced oedema of the rat paw. J Ethnopharmacol 1986, 17, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, T.; Yoshimura, M.; Amakura, Y. Chemical and Biological Significance of Oenothein B and Related Ellagitannin Oligomers with Macrocyclic Structure. Molecules 2018, 23, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isla, K.K.Y.; Tanae, M.M.; de Lima-Landman, M.T.R.; de Magalhães, P.M.; Lapa, A.J.; Souccar, C. Vasorelaxant effects of ellagitannins isolated from Cuphea carthagenensis. Planta Med 2024, 90, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosby, K.; Partovi, K.S.; Crawford, J.H.; Patel, R.P.; Reiter, C.D.; Martyr, S.; Yang, B.K.; Waclawiw, M.A.; Zalos, G.; Xu, X.; Huang, K.T.; Shields, H.; Kim-Shapiro, D.B.; Schechter, A.N.; Cannon, R.O., 3rd; Gladwin, M.T. , 3rd; Gladwin, M.T. Nitrite reduction to nitric oxide by deoxyhemoglobin vasodilates the human circulation. Nat Med 2003, 9, 1498–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.Y.; Oh, H.; Li, X.; Cho, K.W.; Kang, D.G.; Lee, H.S. Ethanol extract of seeds of Oenothera odorata induces vasorelaxation via endothelium-dependent NO-cGMP signaling through activation of Akt-eNOS-sGC pathway. J Ethnopharmacol 2011, 133, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shikov, A.N.; Poltanov, E.A.; Dorman, H.J.; Makarov, V.G.; Tikhonov, V.P.; Hiltunen, R. Chemical composition and in vitro antioxidant evaluation of commercial water-soluble willow herb (Epilobium angustifolium L.) extracts. J Agric Food Chem 2006, 54, 3617–3624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stajner, D. ; Popović; B M., Boza, P. Evaluation of willow herb's (Epilobium angustofolium L.) antioxidant and radical scavenging capacities. Phytother Res 2007, 21, 1242–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hevesi, B.T.; Houghton, P.J.; Habtemariam, S.; Kéry, A. Antioxidant and antiinflammatory effect of Epilobium parviflorum Schreb. Phytother Res 2009, 23, 719–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merighi, S.; Travagli, A.; Tedeschi, P.; Marchetti, N.; Gessi, S. Antioxidant and Antiinflammatory Effects of Epilobium parviflorum, Melilotus officinalis and Cardiospermum halicacabum Plant Extracts in Macrophage and Microglial Cells. Cells 2021, 10, 2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.L.; Wang, C.C.; Yen, K.Y.; Yoshida, T.; Hatano, T.; Okuda, T. Antitumor activities of ellagitannins on tumor cell lines. Basic Life Sci 1999, 66, 615–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakagami, H.; Jiang, Y.; Kusama, K.; Atsumi, T.; Ueha, T.; Toguchi, M.; Iwakura, I.; Satoh, K.; Ito, H.; Hatano, T.; Yoshida, T. Cytotoxic activity of hydrolyzable tannins against human oral tumor cell lines--a possible mechanism. Phytomedicine 2000, 7, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumagai, T.; Kawamoto, Y.; Nakamura, Y.; Hatayama, I.; Satoh, K.; Osawa, T.; Uchida, K. 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal, the end product of lipid peroxidation, is a specific inducer of cyclooxygenase-2 gene expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2000, 273, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Xia, Y.; Garcia, G. E. , Hwang, D., Wilson, C. B. Involvement of reactive oxygen intermediates in cyclooxygenase-2 expression induced by interleukin-1, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and lipopolysaccharide. J Clin Invest 1995, 95, 1669–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuda, T.; Yoshida, T.; Hatano, T. Pharmacologically active tannins isolated from medicinal plants. Basic Life Sci 1992, 59, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolnik, A.; Olas, B.; Szablińska-Piernik, J.; Lahuta, L.B.; Gromadziński, L.; Majewski, M.S. Antioxidant and anticoagulant properties of myo-inositol determined in an ex vivo studies and gas chromatography analysis. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 25633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtacha, P.; Bogdańska-Chomczyk, E.; Majewski, M.K.; Obremski, K.; Majewski, M.S.; Kozłowska, A. Renal Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Metabolic Abnormalities During the Initial Stages of Hypertension in Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. Cells 2024, 13, 1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żary-Sikorska, E.; Fotschki, B.; Kołodziejczyk, K.; Jurgoński, A.; Kosmala, M.; Milala, J.; Majewski, M.; Ognik, K.; Juśkiewicz, J. Strawberry phenolic extracts effectively mitigated metabolic disturbances associated with high-fat ingestion in rats depending on the ellagitannin polymerization degree. Food Funct 2021, 12, 5779–5792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolnik, A.; Olas, B.; Szablińska-Piernik, J.; Lahuta, L.B.; Rynkiewicz, A.; Cygański, P.; Socha, K.; Gromadziński, L.; Thoene, M.; Majewski, M. Beneficial In Vitro Effects of a Low Myo-Inositol Dose in the Regulation of Vascular Resistance and Protein Peroxidation under Inflammatory Conditions. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, A.K.; Kapłon-Cieślicka, A.; Filipiak, K.J.; Opolski, G.; Naruszewicz, M. Ex vivo effects of an Oenothera paradoxa extract on the reactive oxygen species generation and neutral endopeptidase activity in neutrophils from patients after acute myocardial infarction. Phytother Res 2012, 26, 482–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granica, S.; Czerwińska, M.E.; Piwowarski, J.P.; Ziaja, M.; Kiss, A.K. Chemical composition, antioxidative and anti-inflammatory activity of extracts prepared from aerial parts of Oenothera biennis L. and Oenothera paradoxa Hudziok obtained after seeds cultivation. J Agric Food Chem 2013, 61, 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura, M.; Akiyama, H.; Kondo, K.; Sakata, K.; Matsuoka, H.; Amakura, Y.; Teshima, R.; Yoshida, T. Immunological effects of Oenothein B, an ellagitannin dimer, on dendritic cells. Int J Mol Sci 2012, 14, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuyama, S.; Furukawa, Y.; Yoshimura, M.; Amakura, Y.; Nakajima, M.; Yoshida, T. Oenothein B, a Bioactive Ellagitannin, Activates the Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase 2 Signaling Pathway in the Mouse Brain. Plants (Basel) 2021, 10, 1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuyama, S.; Makihata, N.; Yoshimura, M.; Amakura, Y.; Yoshida, T.; Nakajima, M.; Furukawa, Y. Oenothein B suppresses lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced inflammation in the mouse brain. Int J Mol Sci 2013, 14, 9767–9778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majewski, M.; Gromadziński, L.; Cholewińska, E.; Ognik, K.; Fotschki, B.; Juśkiewicz, J. Dietary Effects of Chromium Picolinate and Chromium Nanoparticles in Wistar Rats Fed with a High-Fat, Low-Fiber Diet: The Role of Fat Normalization. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majewski, M.; Lis, B.; Juśkiewicz, J.; Ognik, K.; Jedrejek, D.; Stochmal, A.; Olas, B. The composition and vascular/antioxidant properties of Taraxacum officinale flower water syrup in a normal-fat diet using an obese rat model. J Ethnopharmacol 2021, 265, 113393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortensen, M.B.; Dzaye, O.; Bøtker, H.E.; Jensen, J.M.; Maeng, M.; Bentzon, J.F.; Kanstrup, H.; Sørensen, H.T.; Leipsic, J.; Blankstein, R.; Nasir, K.; Blaha, M.J.; Nørgaard, B.L. Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Is Predominantly Associated With Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Events in Patients With Evidence of Coronary Atherosclerosis: The Western Denmark Heart Registry. Circulation 2023, 147, 1053–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żary-Sikorska, E.; Fotschki, B.; Jurgoński, A.; Kosmala, M.; Milala, J.; Kołodziejczyk, K.; Majewski, M.; Ognik, K.; Juśkiewicz, J. Protective Effects of a Strawberry Ellagitannin-Rich Extract against Pro-Oxidative and Pro-Inflammatory Dysfunctions Induced by a High- Fat Diet in a Rat Model. Molecules 2020, 25, 5874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Li, W.; Chen, S.Y.; Deng, X.W.; Deng, W.F.; Liu, G.; Chen, Y.J.; Cao, Y. Oenothein B ameliorates hepatic injury in alcoholic liver disease mice by improving oxidative stress and inflammation and modulating the gut microbiota. Front Nutr 2022, 9, 1053718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozzelino, R.; Jeney, V.; Soares, M.P. Mechanisms of cell protection by heme oxygenase-1. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2010, 50, 323–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitalone, A.; Guizzetti, M.; Costa, L.G.; Tita, B. Extracts of various species of Epilobium inhibit proliferation of human prostate cells. J Pharm Pharmacol 2003, 55, 683–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesuisse, D.; Berjonneau, J.; Ciot, C.; Devaux, P.; Doucet, B.; Gourvest, J.F.; Khemis, B.; Lang, C.; Legrand, R.; Lowinski, M.; Maquin, P.; Parent, A.; Schoot, B.; Teutsch, G. Determination of oenothein B as the active 5-alpha-reductase-inhibiting principle of the folk medicine Epilobium parviflorum. J Nat Prod 1996, 59, 490–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.A.; Silva, C.R.; Véras, J.H.; Chen-Chen, L.; Ferri, P.H.; Santos, S.d.C. Genotoxicity and cytotoxicity evaluation of oenothein B and its protective effect against mitomycin C-induced mutagenic action. Mutat Res Genet Toxicol Environ Mutagen 2014, 767, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.A.; Véras, J.H.; Ventura, J.A.; de Melo Bisneto, A.V.; de Oliveira, M.G.; Cardoso Bailão, E.F.L.; ESilva, C.R.; Cardoso, C.G.; da Costa Santos, S.; Chen-Chen, L. Chemopreventive effect and induction of DNA repair by oenothein B ellagitannin isolated from leaves of Eugenia uniflora in Swiss Webster treated mice. J Toxicol Environ Health A 2023, 86, 929–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, K.; Kishi, N.; Koshiura, R.; Yoshida, T.; Hatano, T.; Okuda, T. Relationship between the structures and the antitumor activities of tannins. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 1987, 35, 814–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, K.; Nomura, M.; Sasakura, M.; Matsui, E.; Koshiura, R.; Murayama, T.; Furukawa, T.; Hatano, T.; Yoshida, T.; Okuda, T. Antitumor activity of oenothein B, a unique macrocyclic ellagitannin. Jpn J Cancer Res 1993, 84, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murayama, T.; Kishi, N.; Koshiura, R.; Takagi, K.; Furukawa, T.; Miyamoto, K. Agrimoniin, an antitumor tannin of Agrimonia pilosa Ledeb., induces interleukin-1. Anticancer Res 1992, 12, 1471–1474. [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto, K.; Murayama, T.; Nomura, M.; Hatano, T.; Yoshida, T.; Furukawa, T.; Koshiura, R.; Okuda, T. Antitumor activity and interleukin-1 induction by tannins. Anticancer Res 1993, 13, 37–42. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.J.; Kim, Y.S.; Kim, J.H.; Woo, K.W.; Park, Y.H.; Ha, J.H.; Li, W.; Kim, T.I.; An, B.K.; Cho, H.W.; Han, J.H.; Choi, J.G.; Chung, H.S. Uncovering the colorectal cancer immunotherapeutic potential: Evening primrose (Oenothera biennis) root extract and its active compound oenothein B targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 blockade. Phytomedicine 2024, 125, 155370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schepetkin, I.A.; Kirpotina, L.N.; Jakiw, L.; Khlebnikov, A.I.; Blaskovich, C.L.; Jutila, M.A.; Quinn, M.T. Immunomodulatory activity of oenothein B isolated from Epilobium angustifolium. J Immunol 2009, 183, 6754–6766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlase, A.M.; Toiu, A. ; Tomuță; I; Vlase, L.; Muntean, D.; Casian, T.; Fizeșan, I.; Nadăș; GC; Novac, C.Ș.; Tămaș; M; Crișan, G. Epilobium Species: From Optimization of the Extraction Process to Evaluation of Biological Properties. Antioxidants (Basel) 2022, 12, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlase, A.M.; Toiu, A.; Gligor, O.; Muntean, D.; Casian, T.; Vlase, L.; Filip, A.; Bȃldea, I.; Clichici, S.; Decea, N.; Moldovan, R.; Toma, V.A.; Virag, P.; Crișan, G. Investigation of Epilobium hirsutum L. Optimized Extract's Anti-Inflammatory and Antitumor Potential. Plants (Basel) 2025, 13, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakou, S.; Tragkola, V.; Paraskevaidis, I.; Plioukas, M.; Trafalis, D.T.; Franco, R.; Pappa, A.; Panayiotidis, M.I. Chemical Characterization and Biological Evaluation of Epilobium parviflorum Extracts in an In Vitro Model of Human Malignant Melanoma. Plants (Basel) 2023, 12, 1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatefi Kia, B.; Kazemi Noureini, S.; Vaezi Kakhki, M.R. The Extracts of Epilobium Parviflorum Inhibit MCF-7 Breast Cancer Cells. Iran J Toxicol 2021, 15, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, X.; Xiao, J.; Wei, G.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, F.; Xiong, Z.; Lu, L.; Wang, X.; Pang, G.; Jiang, Y.; Jiang, L. Oenothein B inhibits human non-small cell lung cancer A549 cell proliferation by ROS-mediated PI3K/Akt/NF-κB signaling pathway. Chem Biol Interact 2019, 298, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmid, D.; Gruber, M.; Piskaty, C.; Woehs, F.; Renner, A.; Nagy, Z.; Kaltenboeck, A.; Wasserscheid, T.; Bazylko, A.; Kiss, A.K.; Moeslinger, T. Inhibition of NF-κB-dependent cytokine and inducible nitric oxide synthesis by the macrocyclic ellagitannin oenothein B in TLR-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages. J Nat Prod 2012, 75, 870–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramstead, A.G.; Schepetkin, I.A.; Quinn, M.T.; Jutila, M.A. Oenothein B, a cyclic dimeric ellagitannin isolated from Epilobium angustifolium, enhances IFNγ production by lymphocytes. PLoS One 2012, 7, e50546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramstead, A.G.; Schepetkin, I.A.; Todd, K.; Loeffelholz, J.; Berardinelli, J.G.; Quinn, M.T.; Jutila, M.A. Aging influences the response of T cells to stimulation by the ellagitannin, oenothein B. Int Immunopharmacol 2015, 26, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caillon, A.; Mian, M.O.R.; Fraulob-Aquino, J.C.; Huo, K.G.; Barhoumi, T.; Ouerd, S.; Sinnaeve, P.R.; Paradis, P.; Schiffrin, E.L. γδ T Cells Mediate Angiotensin II-Induced Hypertension and Vascular Injury. Circulation 2017, 135, 2155–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias-Aguirre, C.E.; García-Villalba, R.; Beltrán, D.; Frutos-Lisón, M.D.; Espín, J.C.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A.; Selma, M.V. Gut Bacteria Involved in Ellagic Acid Metabolism To Yield Human Urolithin Metabotypes Revealed. Agric Food Chem 2023, 71, 4029–4035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garat, C.V.; Majka, S.M.; Sullivan, T.M.; Crossno, J.T.; Jr Reusch, J.E.B.; Klemm, D.J. CREB depletion in smooth muscle cells promotes medial thickening, adventitial fibrosis and elicits pulmonary hypertension. Pulm Circ 2020, 10, 2045894019898374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiermann, A.; Reidlinger, M.; Juan, H.; Sametz, W. Isolierung des antiphlogistischen Wirkprinzips von Epilobium angustifolium [Isolation of the antiphlogistic principle from Epilobium angustifolium]. Planta Med 1991, 57, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreger, M.; Adamczak, A.; Foksowicz-Flaczyk, J. Antibacterial and Antimycotic Activity of Epilobium angustifolium L. Extracts: A Review. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2023, 16, 1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battinelli, L.; Tita, B.; Evandri, M.G.; Mazzanti, G. Antimicrobial activity of Epilobium spp. extracts. Farmaco 2001, 56, 345–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhou, A.; Liu, Z.; Xiao, J.; Wang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Wang, L. Inhibitory mechanism of lactoferrin on antibacterial activity of oenothein B: isothermal titration calorimetry and computational docking simulation. J Sci Food Agric 2020, 100, 2494–2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolodziej, H.; Kayser, O.; Kiderlen, A.F.; Ito, H.; Hatano, T.; Yoshida, T.; Foo, L.Y. Antileishmanial activity of hydrolyzable tannins and their modulatory effects on nitric oxide and tumour necrosis factor-alpha release in macrophages in vitro. Planta Med 2001, 67, 825–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, G.D.; Ferri, P.H.; Santos, S.C.; Bao, S.N.; Soares, C.M.; Pereira, M. Oenothein B inhibits the expression of PbFKS1 transcript and induces morphological changes in Paracoccidioides brasiliensis. Med Mycol 2007, 45, 609–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Plant | Material | Model (ex vivo/in vitro) |

Intervention | Duration | Parameters measured | Effect | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isla et al. 2024 [10] |

Cuphea carthagenensis (Jacq.) J. F. Macbr (Lythraceae) |

aqueous extract (AE) | Supplementation to rats | 0.5 and 1.0 g/kg/day | 1-week | systolic blood pressure (the non-invasive tail-cuff method) |

hypotensive effect | unknown, ellagitannin independent due to the low oral bioavailability of ellagitannins |

| oenothein B woodfordin C eucalbanin B isolated from AE | Ex vivo – rat aortic rings pre-contracted with vasoconstrictor noradrenaline | 20 – 180 µM | vasorelaxation | concentration-related vasorelaxation | Endothelium dependent, via activating NO synthesis/NO release from endothelial cells without alteration of Ca2+ influx in vascular smooth muscle preparations |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).