Submitted:

09 April 2025

Posted:

12 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Existing Dietary Cd Exposure Guidelines

| Target/ Endpoint | Tolerable Intake/Exposure Threshold Level | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Kidneys, β2M excretion rate ≥ 300 µg/g creatinine. |

A tolerable intake level of 0.83 μg/kg body weight/day (58 µg per day for a 70 kg person). A cumulative lifetime intake of 2 g. Assumed Cd absorption rate of 3–7%. Threshold level of 5.24 μg/g creatinine. |

JECFA [25] |

| Kidneys, β2M excretion rate ≥ 300 µg/g creatinine. |

A reference dose of 0.36 μg/kg body weight per day (25.2 µg per day for a 70 kg person) Threshold level of 1 μg /g creatinine |

EFSA [26,27] |

| Kidneys, β2M and NAG excretion rates |

A tolerable intake level of 0.28 μg/ kg body weight per day; 16.8 µg/day for a 60 kg person. Threshold levels for the β2M and NAG effects were 3.07 and 2.93 μg/g creatinine, respectively. An average dietary Cd exposure in China was 30.6 μg/day. |

Qing et al. 2021 [28] |

| Bones, Bone mineral density |

A tolerable Cd intake of 0.64 μg/kg body weight per day. Threshold level of 1.71 μg/g creatinine. |

Qing et al. 2021 [29] |

| Bones, Bone mineral density |

A tolerable intake level of 0.35 μg/kg body weight per day. Assumed threshold level of 0.5 μg/g creatinine. |

Leconte et al. 2021 [30] |

| Kidneys and bones, Reverse dosimetry PBPK modeling |

Toxicological reference values were 0.21 and 0.36 μg/ kg body weight per day, assuming a similar threshold level for effects on kidneys and bones of 0.5 μg/g creatinine. | Schaefer et al. 2023 [31] |

3. Imprecisions in Measuring Internal Cd Doses and Adverse Outcomes

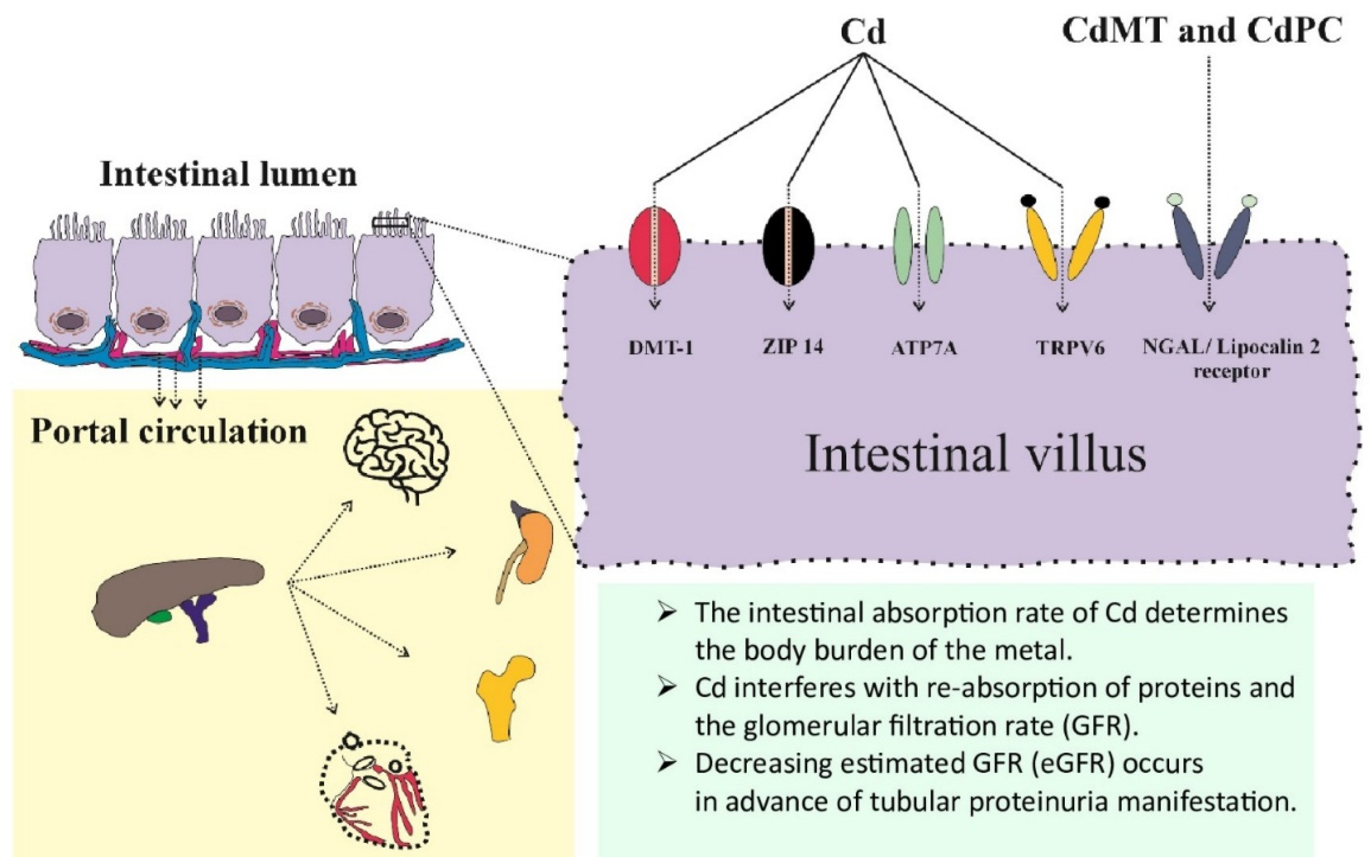

3.1. Assimilation of Cd and Its Determinants

3.2. Use of Blood Cd Concentration in Toxicological Risk Assessment

3.3. Urinary Cd Excretion as an Indicator of Body Burden

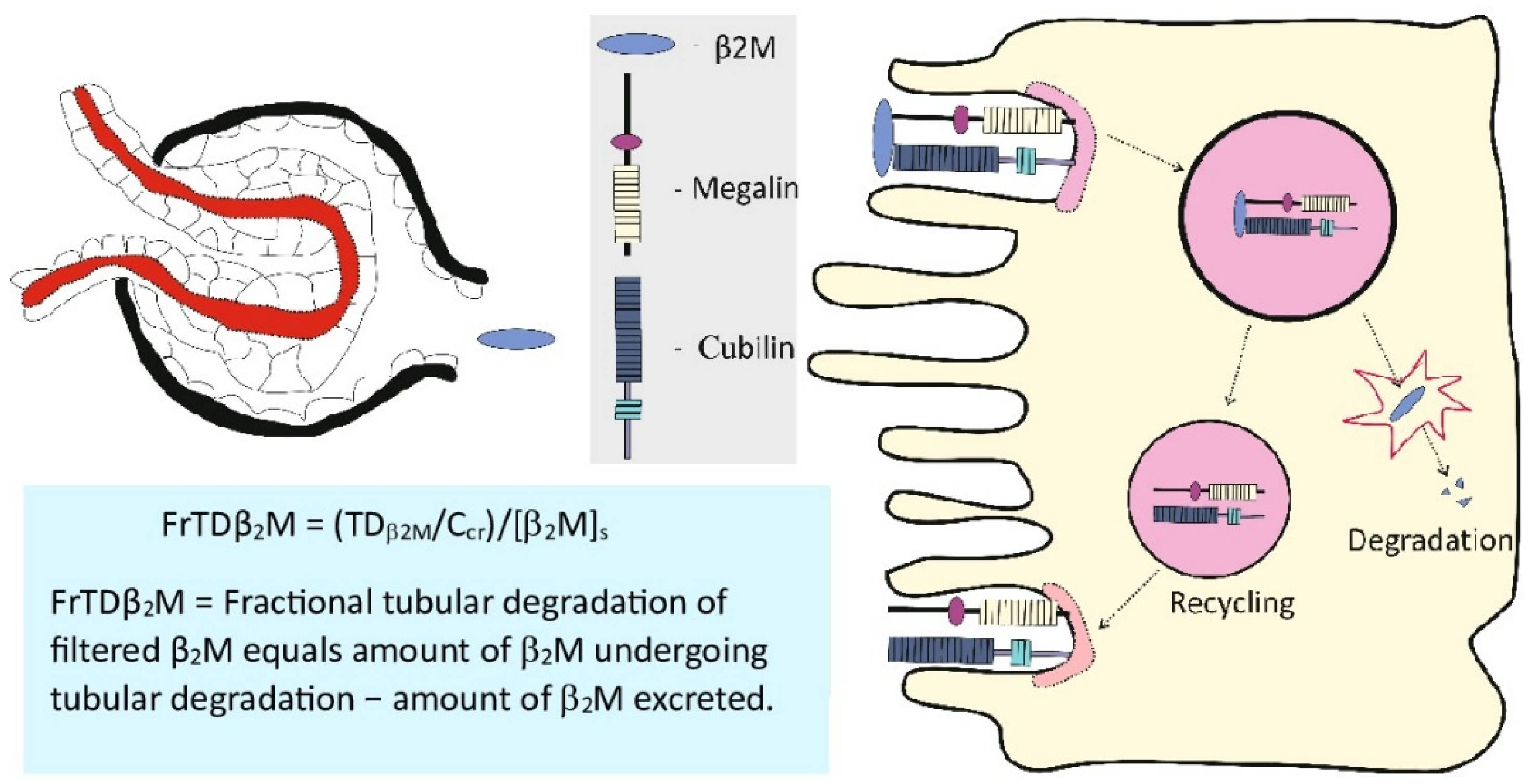

3.4. Use of Urinary β2M in Measuring Cd effect on Tubular Reabsorptive Function

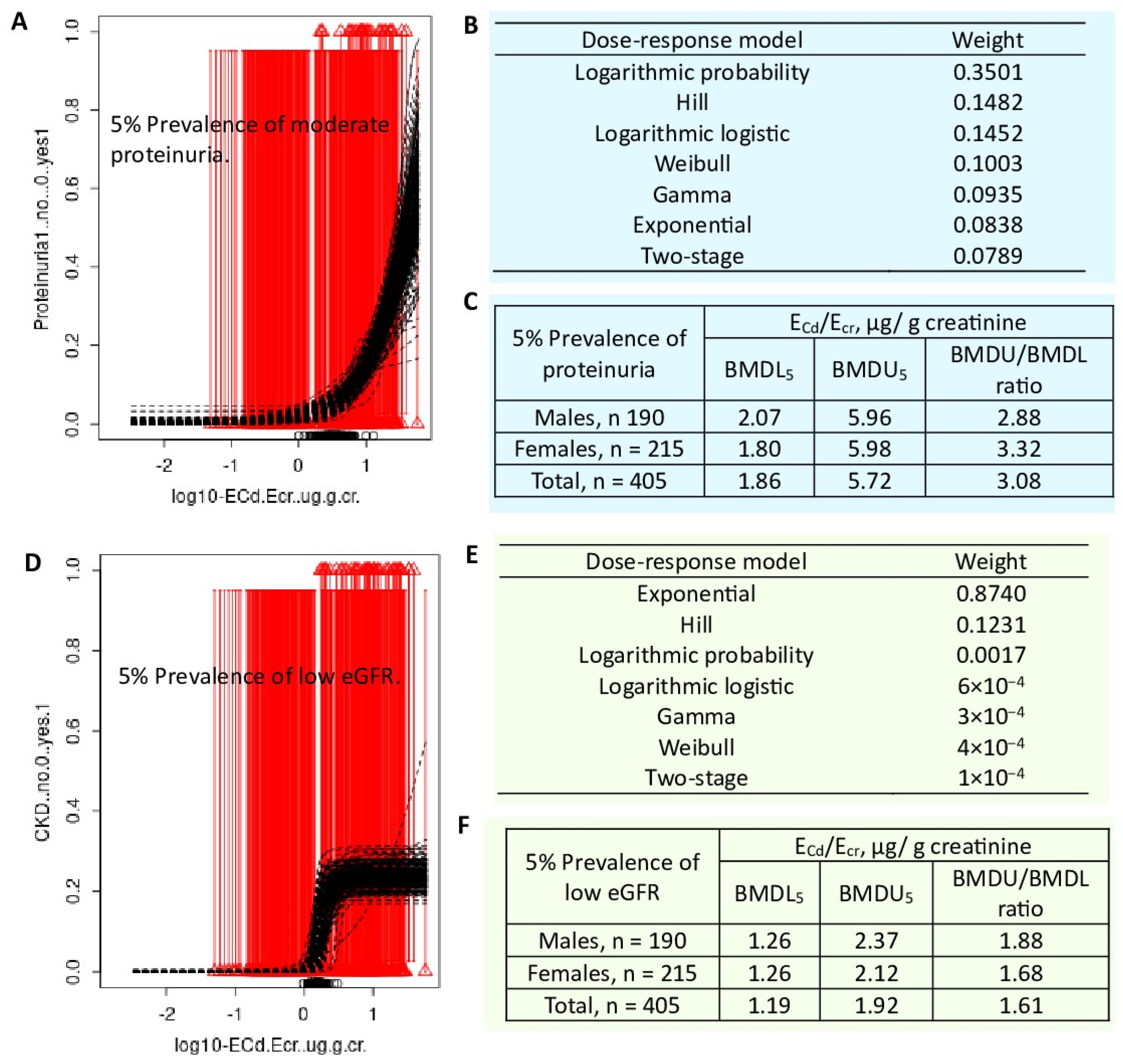

4. Benchmark Dose Modeling of Cd Exposure and Its Nephrotoxicity

4.1. Mathematical Models for Dose-Response Relationship Appraisal

4.1.1. Identification of POD, BMDL/BMDU, and NOAEL Equivalent of Cd Exposure

4.1.2. Exposure Threshold Identification, BMDL5/BMDL10

4.2. Dose-Response Relationship

4.3. The PROAST Software for BMD Modeling

4.4. Comparing Reposretd BMD Values for Different Nephrotoxic Endpoints

4.5. BMDL5 and BMDL10 Values of Cd Exposure Derived from Ecr- and Ccr Normalized Data

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moffett, D.B.; Mumtaz, M.M.; Sullivan, D.W., Jr.; Whittaker, M.H. Chapter 13, General Considerations of Dose-Effect and Dose-Response Relationships. In Handbook on the Toxicology of Metals, 5th ed.; Volume I: General Considerations; Nordberg, G., Costa, M., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 299–317. [Google Scholar]

- Sand, S.; Filipsson, A.F.; Victorin, K. Evaluation of the benchmark dose method for dichotomous data: model dependence and model selection. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2002, 36, 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slob, W.; Moerbeek, M.; Rauniomaa, E.; Piersma, A.H. A statistical evaluation of toxicity study designs for the estimation of the benchmark dose in continuous endpoints. Toxicol. Sci. 2005, 84, 167–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slob, W.; Setzer, R.W. Shape and steepness of toxicological dose-response relationships of continuous endpoints. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2014, 44, 270–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slob, W. A general theory of effect size, and its consequences for defining the benchmark response (BMR) for continuous endpoints. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2017, 47, 342–351. [Google Scholar]

- EFSA Scientific Committee. Update: Use of the benchmark dose approach in risk assessment. EFSA J. 2017, 15, 4658. [Google Scholar]

- Waalkes, M.P.; Rehm, S. Chronic toxic and carcinogenic effects of cadmium chloride in male DBA/2NCr and NFS/NCr mice: Strain-dependent association with tumors of the hematopoietic system, injection site, liver, and lung. Fundam. Appl. Toxicol. 1994, 23, 21–31. [Google Scholar]

- Huff, J.; Lunn, R.M.; Waalkes, M.P.; Tomatis, L.; Infante, P.F. Cadmium-induced cancers in animals and in humans. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Health 2007, 13, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokar, E.J.; Benbrahim-Tallaa, L.; Waalkes, M.P. Metal ions in human cancer development. Met. Ions Life Sci. 2011, 8, 375–401. [Google Scholar]

- Callan, A.; Hinwood, A.; Devine, A. Metals in commonly eaten groceries in Western Australia: A market basket survey and dietary assessment. Food Addit. Contam. Part A Chem. Anal. Control Expo. Risk Assess. 2014, 31, 1968–1981. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, T.; Kataoka, Y.; Hayashi, K.; Matsuda, R.; Uneyama, C. Dietary Exposure of the Japanese General Population to Elements: Total Diet Study 2013-2018. Food Saf. (Tokyo) 2022, 10, 83–101. [Google Scholar]

- Pokharel, A.; Wu, F. Dietary exposure to cadmium from six common foods in the United States. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2023, 178, 113873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boon, P.E.; Pustjens, A.M.; Te Biesebeek, J.D.; Brust, G.M.H.; Castenmiller, J.J.M. Dietary intake and risk assessment of elements for 1- and 2-year-old children in the Netherlands. Food Chem Toxicol. 2022, 161, 112810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almerud, P.; Zamaratskaia, G.; Lindroos, A.K.; Bjermo, H.; Andersson, E.M.; Lundh, T.; Ankarberg, E.H.; Lignell, S. Cadmium, total mercury, and lead in blood and associations with diet, sociodemographic factors, and smoking in Swedish adolescents. Environ. Res. 2021, 197, 110991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, D.T.; Jandev, V.; Petroni, M.; Atallah-Yunes, N.; Bendinskas, K.; Brann, L.S.; Heffernan, K.; Larsen, D.A.; MacKenzie, J.A.; Palmer, C.D.; et al. Airborne levels of cadmium are correlated with urinary cadmium concentrations among young children living in the New York state city of Syracuse, USA. Environ. Res. 2023, 223, 115450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satarug, S.; Vesey, D.A.; Gobe, G.C.; Phelps, K.R. Estimation of health risks associated with dietary cadmium exposure. Arch. Toxicol. 2023, 97, 329–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egger, A.E.; Grabmann, G.; Gollmann-Tepeköylü, C.; Pechriggl, E.J.; Artner, C.; Türkcan, A.; Hartinger, C.G.; Fritsch, H.; Keppler, B.K.; Brenner, E.; et al. Chemical imaging and assessment of cadmium distribution in the human body. Metallomics 2019, 11, 2010–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cirovic, A.; Satarug, S. Toxicity Tolerance in the Carcinogenesis of Environmental Cadmium. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satarug, S.; Garrett, S.H.; Somji, S.; Sens, M.A.; Sens, D.A. Aberrant Expression of ZIP and ZnT Zinc Transporters in UROtsa Cells Transformed to Malignant Cells by Cadmium. Stresses 2021, 1, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandjean, P.; Budtz-Jørgensen, E. Total imprecision of exposure biomarkers: implications for calculating exposure limits. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2007, 50, 712–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoshima, K. Epidemiology of renal tubular dysfunction in the inhabitants of a cadmium-polluted area in the Jinzu River basin in Toyama Prefecture. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 1987, 152, 151–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horiguchi, H.; Aoshima, K.; Oguma, E.; Sasaki, S.; Miyamoto, K.; Hosoi, Y.; Katoh, T.; Kayama, F. Latest status of cadmium accumulation and its effects on kidneys, bone, and erythropoiesis in inhabitants of the formerly cadmium-polluted Jinzu River Basin in Toyama, Japan, after restoration of rice paddies. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2010, 83, 953–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurata, Y.; Katsuta, O.; Doi, T.; Kawasuso, T.; Hiratsuka, H.; Tsuchitani, M.; Umemura, T. Chronic cadmium treatment induces tubular nephropathy and osteomalacic osteopenia in ovariectomized cynomolgus monkeys. Vet. Pathol. 2014, 51, 919–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, C.; Roberts, S.M.; Saab, I.N. Review of regulatory reference values and background levels for heavy metals in the human diet. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2022, 130, 105122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JECFA. Summary and Conclusions. In Proceedings of the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives and Contaminants, Seventy-Third Meeting, Geneva, Switzerland, 8–17 June 2010; JECFA/73/SC. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations/World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44521 (accessed on 22 March 2025).

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) Scientific opinion on cadmium in food. EFSA J. 2009, 980, 1–139.

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) Statement on tolerable weekly intake for cadmium. EFSA J. 2011, 9, 1975.

- Qing, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zheng, W.; Wu, M.; He, G. Dose-response evaluation of urinary cadmium and kidney injury biomarkers in Chinese residents and dietary limit standards. Environ. Health 2021, 20, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qing, Y.; Yang, J.; Chen, Y.; Shi, C.; Zhang, Q.; Ning, Z.; Yu, Y.; Li, Y. Urinary cadmium in relation to bone damage: Cadmium exposure threshold dose and health-based guidance value estimation. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 226, 112824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leconte, S.; Rousselle, C.; Bodin, L.; Clinard, F.; Carne, G. Refinement of health-based guidance values for cadmium in the French population based on modelling. Toxicol. Lett. 2021, 340, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, H.R.; Flannery, B.M.; Crosby, L.M.; Pouillot, R.; Farakos, S.M.S.; Van Doren, J.M.; Dennis, S.; Fitzpatrick, S.; Middleton, K. Reassessment of the cadmium toxicological reference value for use in human health assessments of foods. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2023, 144, 105487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouillot, R.; Farakos, S.S.; Spungen, J.; Schaefer, H.R.; Flannery, B.M.; Van Doren, J.M. Cadmium physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models for forward and reverse dosimetry: Review, evaluation, and adaptation to the U.S. population. Toxicol. Lett. 2022, 367, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzóska, M.M.; Moniuszko-Jakoniuk, J. Disorders in bone metabolism of female rats chronically exposed to cadmium. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2005, 202, 68–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brzóska, M.M.; Moniuszko-Jakoniuk, J. Bone metabolism of male rats chronically exposed to cadmium. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2005, 207, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brzóska, M.M.; Moniuszko-Jakoniuk, J. Effect of low-level lifetime exposure to cadmium on calciotropic hormones in aged female rats. Arch. Toxicol. 2005, 79, 636–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faroon, O.; Keith, S.; Mumtaz, M.; Ruiz, P. Minimal Risk Level Derivation for Cadmium: Acute and Intermediate Duration Exposures. J. Exp. Clin. Toxicol. 2017, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NTP, NIH Publication 95–3388: NTP technical report on toxicity studies of cadmium oxide (CAS No. 1306–19-0) Administered by Inhalation to F344/N Rats and B6C3F1 Mice, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. National Institutes of Health. National Toxicology Program, Research Triangle Park, NC, 1995.

- Fujita, Y.; el Belbasi, H.I.; Min, K.S.; Onosaka, S.; Okada, Y.; Matsumoto, Y.; Mutoh, N.; Tanaka, K. Fate of cadmium bound to phytochelatin in rats. Res. Commun. Chem. Pathol. Pharmacol. 1993, 82, 357–365. [Google Scholar]

- Langelueddecke, C.; Roussa, E.; Fenton, R.A.; Thévenod, F. Expression and function of the lipocalin-2 (24p3/NGAL) receptor in rodent and human intestinal epithelia. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e71586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langelueddecke, C.; Lee, W.K.; Thévenod, F. Differential transcytosis and toxicity of the hNGAL receptor ligands cadmium-metallothionein and cadmium-phytochelatin in colon-like Caco-2 cells: Implications for in vivo cadmium toxicity. Toxicol. Lett. 2014, 226, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, S.N.; Liu, Z.; Wang, B.; Miller, M.L.; Afton, S.E.; Soleimani, M.; Nebert, D.W. Oral cadmium in mice carrying 5 versus 2 copies of the Slc39a8 gene: Comparison of uptake, distribution, metal content, and toxicity. Int. J. Toxicol. 2014, 33, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujishiro, H.; Himeno, S. New insights into the roles of ZIP8, a cadmium and manganese transporter, and its relation to human diseases. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2019, 42, 1076–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thévenod, F.; Fels, J.; Lee, W.K.; Zarbock, R. Channels, transporters and receptors for cadmium and cadmium complexes in eukaryotic cells: Myths and facts. Biometals 2019, 32, 469–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohta, H.; Ohba, K. Involvement of metal transporters in the intestinal uptake of cadmium. J. Toxicol. Sci. 2020, 45, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kikuchi, Y.; Nomiyama, T.; Kumagai, N.; Dekio, F.; Uemura, T.; Takebayashi, T.; Nishiwaki, Y.; Matsumoto, Y.; Sano, Y.; Hosoda, K.; et al. Uptake of cadmium in meals from the digestive tract of young non-smoking Japanese female volunteers. J. Occup. Health 2003, 45, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horiguchi, H.; Oguma, E.; Sasaki, S.; Miyamoto, K.; Ikeda, Y.; Machida, M.; Kayama, F. Comprehensive study of the effects of age, iron deficiency, diabetes mellitus, and cadmium burden on dietary cadmium absorption in cadmium-exposed female Japanese farmers. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2004, 196, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satarug, S.; Vesey, D.A.; Ruangyuttikarn, W.; Nishijo, M.; Gobe, G.C.; Phelps, K.R. The Source and Pathophysiologic Significance of Excreted Cadmium. Toxics 2019, 7, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Li, C.; Zhao, D.; Huang, L. Associations of micronutrients exposure with cadmium body burden among population: A systematic review. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 256, 114878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, M.K.; Lozoff, B.; Meeker, J.D. Blood cadmium is elevated in iron deficient U.S. children: A cross-sectional study. Environ Health 2013, 12, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schildroth, S.; Friedman, A.; Bauer, J.A.; Claus Henn, B. Associations of a metal mixture with iron status in U.S. adolescents: Evidence from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. New Dir. Child Adolesc. Dev. 2022, 2022, 67–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flanagan, P.R.; McLellan, J.S.; Haist, J.; Cherian, G.; Chamberlain, M.J.; Valberg, L.S. Increased dietary cadmium absorption in mice and human subjects with iron deficiency. Gastroenterol. 1978, 74 Pt 1, 841–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meltzer, H.M.; Brantsaeter, A.L.; Borch-Iohnsen, B.; Ellingsen, D.G.; Alexander, J.; Thomassen, Y.; Stigum, H.; Ydersbond, T.A. Low iron stores are related to higher blood concentrations of manganese, cobalt and cadmium in non-smoking, Norwegian women in the HUNT 2 study. Environ. Res. 2010, 110, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, J.C.; Brown, K.H.; Gibson, R.S.; Krebs, N.F.; Lowe, N.M.; Siekmann, J.H.; Raiten, D.J. Biomarkers of nutrition for development (BOND)-zinc review. J. Nutr. 2015, 146, 858S–885S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trame, S.; Wessels, I.; Haase, H.; Rink, L. A short 18 items food frequency questionnaire biochemically validated to estimate zinc status in humans. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2018, 49, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, N.M.; Hall, A.G.; Broadley, M.R.; Foley, J.; Boy, E.; Bhutta, Z.A. Preventing and controlling zinc deficiency across the life course: A call to action. Adv. Nutr. 2024, 15, 100181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cirovic, A.; Cirovic, A. Factors moderating cadmium bioavailability: Key considerations for comparing blood cadmium levels between groups. Food Chem Toxicol. 2024, 191, 114865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Maele-Fabry, G.; Lombaert, N.; Lison, D. Dietary exposure to cadmium and risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Int. 2016, 86, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, S.C.; Orsini, N.; Wolk, A. Urinary cadmium concentration and risk of breast cancer: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2015, 182, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Zhang, F.; Lei, Y. Dietary intake and urinary level of cadmium and breast cancer risk: A meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol. 2016, 42, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adokwe, J.B.; Pouyfung, P.; Kuraeiad, S.; Wongrith, P.; Inchai, P.; Yimthiang, S.; Satarug, S.; Khamphaya, T. Concurrent Lead and Cadmium Exposure Among Diabetics: A Case-Control Study of Socio-Demographic and Consumption Behaviors. Nutrients 2025, 17, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, G.G.; Il’yasova, D.; Ivanova, A. Urinary cadmium, impaired fasting glucose, and diabetes in the NHANES III. Diabetes Care 2003, 26, 468–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallia, A.; Allen, N.B.; Badon, S.; El Muayed, M. Association between urinary cadmium levels and prediabetes in the NHANES 2005-2010 population. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2014, 217, 854–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Zhi, X.; Xu, M.; Li, B.; Zhang, Z. Gender-specific differences of interaction between cadmium exposure and obesity on prediabetes in the NHANES 2007-2012 population. Endocrine 2018, 61, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barregard, L.; Fabricius-Lagging, E.; Lundh, T.; Mölne, J.; Wallin, M.; Olausson, M.; Modigh, C.; Sallstenm, G. Cadmium, mercury, and lead in kidney cortex of living kidney donors: Impact of different exposure sources. Environ. Res. 2010, 110, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akerstrom, M.; Barregard, L.; Lundh, T.; Sallsten, G. The relationship between cadmium in kidney and cadmium in urine and blood in an environmentally exposed population. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2013, 268, 286–293. [Google Scholar]

- Satarug, S.; Vesey, D.A.; Nishijo, M.; Ruangyuttikarn, W.; Gobe, G.C.; Phelps, K.R. The Effect of Cadmium on GFR Is Clarified by Normalization of Excretion Rates to Creatinine Clearance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelps, K.R.; Gosmanova, E.O. A generic method for analysis of plasma concentrations. Clin. Nephrol. 2020, 94, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navar, L.G.; Maddox, D.A.; Munger, K.A. Chapter 3: The renal circulations and glomerular filtration. In Brenner and Rector’s the Kidney, 11th ed.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 80–114. [Google Scholar]

- Argyropoulos, C.P.; Chen, S.S.; Ng, Y.-H.; Roumelioti, M.-E.; Shaffi, K.; Singh, P.P.; Tzamaloukas, A.H. Rediscovering Beta-2 Microglobulin As a Biomarker across the Spectrum of Kidney Diseases. Front. Med. 2017, 4, 73. [Google Scholar]

- Sivanathan, P.C.; Ooi, K.S.; Mohammad Haniff, M.A.S.; Ahmadipour, M.; Dee, C.F.; Mokhtar, N.M.; Hamzah, A.A.; Chang, E.Y. Lifting the Veil: Characteristics, Clinical Significance, and Application of β-2-Microglobulin as Biomarkers and Its Detection with Biosensors. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 8, 3142–3161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelps, K.R.; Yimthiang, S.; Pouyfung, P.; Khamphaya, T.; Vesey, D.A.; Satarug, S. Homeostasis of β2-Microglobulin in Diabetics and Non-Diabetics with Modest Cadmium Intoxication. Scierxiv 2025, 2025, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murton, M.; Goff-Leggett, D.; Bobrowska, A.; Garcia Sanchez, J.J.; James, G.; Wittbrodt, E.; Nolan, S.; Sörstadius, E.; Pecoits-Filho, R.; Tuttle, K. Burden of Chronic Kidney Disease by KDIGO Categories of Glomerular Filtration Rate and Albuminuria: A Systematic Review. Adv. Ther. 2021, 38, 180–200. [Google Scholar]

- Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Jafar, T.H.; Nitsch, D.; Neuen, B.L.; Perkovic, V. Chronic kidney disease. Lancet 2021, 398, 786–802. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Farrell, D.R.; Vassalotti, J.A. Screening, identifying, and treating chronic kidney disease: Why, who, when, how, and what? BMC Nephrol. 2024, 25, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Z.; Taylor, A.W.; Riley, M.; Byles., J.; Liu, J.; Noakes, M. Association between dietary patterns, cadmium intake and chronic kidney disease among adults. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 37, 276–284. [Google Scholar]

- Satarug, S.; Đorđević, A.B.; Yimthiang, S.; Vesey, D.A.; Gobe, G.C. The NOAEL equivalent of environmental cadmium exposure associated with GFR reduction and chronic kidney disease. Toxics 2022, 10, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, X.; Zhou, R.; Jiang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Chen, C. Analysis of cadmium accumulation in community adults and its correlation with low-grade albuminuria. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 834, 155210. [Google Scholar]

- Grau-Perez, M.; Pichler, G.; Galan-Chilet, I.; Briongos-Figuero, L.S.; Rentero-Garrido, P.; Lopez-Izquierdo, R.; Navas-Acien, A.; Weaver, V.; García-Barrera, T.; Gomez-Ariza, J.L.; et al. Urine cadmium levels and albuminuria in a general population from Spain: A gene-environment interaction analysis. Environ. Int. 2017, 106, 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Byber, K.; Lison, D.; Verougstraete, V.; Dressel, H.; Hotz, P. Cadmium or cadmium compounds and chronic kidney disease in workers and the general population: A systematic review. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2016, 46, 191–240. [Google Scholar]

- Jalili, C.; Kazemi, M.; Cheng, H.; Mohammadi, H.; Babaei, A.; Taheri, E.; Moradi, S. Associations between exposure to heavy metals and the risk of chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2021, 51, 165–182. [Google Scholar]

- Doccioli, C.; Sera, F.; Francavilla, A.; Cupisti, A.; Biggeri, A. Association of cadmium environmental exposure with chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 906, 167165. [Google Scholar]

- Satarug, S.; Vesey, D.A.; Đorđević, A.B. The NOAEL equivalent for the cumulative body burden of cadmium: focus on proteinuria as an endpoint. J. Environ. Expo. Assess. 2024, 3, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Qing, Y.; Li, Y.; Cai, X.; He, W.; Liu, S.; Ji, Y.; Jiang, M.; Yang, L.; Wang, J.; Ping, S.; et al. Assessment of Cadmium Concentrations in Foodstuffs and Dietary Exposure Risk Across China: A Metadata Analysis. Exposure and Health 2023, 15, 951–961. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Li, Y.; Zhu, C.; Dong, Z.; Zhang, K.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, Y. Benchmark dose for cadmium exposure and elevated N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase: A meta-analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2016, 23, 20528–20538. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, H.D.; Chiu, W.A.; Jo, S.; Kim, J. Benchmark Dose for Urinary Cadmium based on a Marker of Renal Dysfunction: A Meta-Analysis. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0126680. [Google Scholar]

- Suwazono, Y.; Sand, S.; Vahter, M.; Filipsson, A.F.; Skerfving, S.; Lidfeldt, J.; Akesson, A. Benchmark dose for cadmium-induced renal effects in humans. Environ. Health Perspect. 2006, 114, 1072–1076. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Feng, L.; Tong, Y.; Chen, Z.; Ying, S.; Chen, T.; Li, T.; Xia, H.; Jiang, Z.; et al. Application of the benchmark dose (BMD) method to identify thresholds of cadmium-induced renal effects in non-polluted areas in China. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0161240. [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi, T.; Nogawa, K.; Watanabe, Y.; Kido, T.; Sakurai, M.; Nakagawa, H.; Suwazono, Y. Benchmark Dose of Urinary Cadmium for Assessing Renal Tubular and Glomerular Function in a Cadmium-Polluted Area of Japan. Toxics 2024, 12, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satarug, S.; Vesey, D.A.; Gobe, G.C.; Đorđević, A.B. The Validity of Benchmark Dose Limit Analysis for Estimating Permissible Accumulation of Cadmium. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 15697. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, S.; Perrais, M.; Golshayan, D.; Wuerzner, G.; Vaucher, J.; Thomas, A.; Marques-Vidal, P. Association between urinary heavy metal/trace element concentrations and kidney function: a prospective study. Clin. Kidney J. 2024, 18, sfae378. [Google Scholar]

- Satarug, S.; Vesey, D.A.; Gobe, G.C.; Yimthiang, S.; Buha Đorđević, A. Health Risk in a Geographic Area of Thailand with Endemic Cadmium Contamination: Focus on Albuminuria. Toxics 2023, 11, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satarug, S. Urinary N-acetylglucosaminidase in People Environmentally Exposed to Cadmium Is Minimally Related to Cadmium-Induced Nephron Destruction. Toxics 2024, 12, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| a Low eGFR | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model A | POR | 95% CI | p | |

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Log2[(ECd/Ecr) × 103], µg/g creatinine | 1.470 | 1.276 | 1.692 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 1.632 | 0.885 | 3.008 | 0.117 |

| Gender | 1.029 | 0.528 | 2.002 | 0.934 |

| Smoking | 1.232 | 0.637 | 2.383 | 0.536 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | ||||

| 12-18 | Referent | |||

| 19-23 | 1.058 | 0.459 | 2.439 | 0.894 |

| ≥ 24 | 2.810 | 1.118 | 7.064 | 0.028 |

| Age, years | ||||

| 16-45 | Referent | |||

| 46-55 | 14.23 | 1.867 | 108.4 | 0.010 |

| 56-65 | 28.21 | 3.538 | 224.9 | 0.002 |

| 66-87 | 141.2 | 17.87 | 1116 | <0.001 |

| Model B | POR | Lower | Upper | p |

| Log2[(ECd/Ccr) × 105], µg/L filtrate | 1.962 | 1.589 | 2.422 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 1.735 | 0.916 | 3.287 | 0.091 |

| Gender | 0.840 | 0.410 | 1.719 | 0.633 |

| Smoking | 0.944 | 0.474 | 1.879 | 0.869 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | ||||

| 12-18 | Referent | |||

| 19-23 | 1.109 | 0.452 | 2.717 | 0.822 |

| ≥ 24 | 3.150 | 1.181 | 8.400 | 0.022 |

| Age, years | ||||

| 16-45 | Referent | |||

| 46-55 | 9.951 | 1.305 | 75.88 | 0.027 |

| 56-65 | 34.57 | 4.312 | 277.2 | 0.001 |

| 66-87 | 198.6 | 24.59 | 1605 | <0.001 |

| Low eGFR a | Proteinuria b | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model A | POR (95% CI) | p | POR (95% CI) | p |

| Age, years | 1.121 (1.080, 1.165) | <0.001 | 1.068 (1.028, 1.110) | 0.001 |

| Log10[(ECd/Ecr) ×103], µg/g creatinine | 2.638 (0.969, 7.182) | 0.058 | 3.685 (1.027, 13.22) | 0.045 |

| Gender | 1.082 (0.490, 2.390) | 0.845 | 1.096 (0.475, 2.528) | 0.829 |

| Smoking | 1.425 (0.596, 3.406) | 0.426 | 1.678 (0.627, 4.486) | 0.303 |

| Hypertension | 2.211 (1.017, 4.805) | 0.045 | 1.113 (0.432, 2.867) | 0.824 |

| Model B | POR (95% CI) | p | POR (95% CI) | p |

| Age, years | 1.118 (1.073, 1.165) | <0.001 | 1.061 (1.022, 1.102) | 0.002 |

| Log10[(ECd/Ccr) ×105], mg/ L filtrate | 12.24 (3.729, 40.20) | <0.001 | 7.143 (2.133, 23.92) | 0.001 |

| Gender | 0.802 (0.346, 1.861) | 0.608 | 1.117 (0.482, 2.587) | 0.796 |

| Smoking | 1.335 (0.546, 3.262) | 0.527 | 1.947 (0.725, 5.234) | 0.186 |

| Hypertension | 2.734 (1.204, 6.207) | 0.016 | 1.018 (0.410, 2.530) | 0.969 |

| Endpoints/Population | Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| NAG and eGFR n = 790 women, 53–64 years, Sweden |

BMDL (BMD) values of ECd/Ecr were 0.5 (0.6) and 0.7 (1.1) μg/g creatinine the NAG and eGFR endpoints, respectively. |

Suwazono et al. 2006[86] |

| RBP, β2M and NAG n = 934 (469 men, 465 women), 10–71+ years, Jiangshan City, Zhejiang, China |

BMDL values of ECd/Ecr at 5% (10%) BMR in men were 0.89 (1.59), 0.62 (1.30), 0.49 (1.04) μg/g creatinine for the RBP, β2M, and NAG endpoints, respectively. Corresponding BMDL values of ECd/Ecr in women were 0.76 (1.53), 0.64 (1.34), 0.65 (1.37) μg/g creatinine for the RBP, β2M, and NAG endpoints. |

Wang et al. 2016 [87] |

| β2M, TRβ2M and eGFR (or Ccr) n = 112 (Cd-polluted area, n = 74, non-polluted area, n =38) Japan |

BMDL values of ECd/Ecr in men were 1.8, 1.8, and 3.6 μg/g creatinine for the β2M endpoint and decreases in TRβ2M by 5% and 10%, respectively. Corresponding BMDL values of ECd/Ecr in women were 2.5, 2.6, and 3.9 μg/g creatinine. BMDL values of ECd/Ecr for the eGFR (Ccr) endpoint in men and women were 2.9 and 3.5 μg/g creatinine, respectively |

Hayashi et al. 2024 [88] |

| NAG, β2M, and eGFR n = 734 (Bangkok, n = 200, Mae Sot, n = 534), 16–87 years, Thailand |

BMDL/BMDU values of ECd/Ecr in men were 0.060/0.504 µg/g creatinine for the NAG, while BMDL10/BMDU10 values were 0.469/0.973 and 3.26/7.46 µg/g creatinine for the β2-microglobulinuria and low eGFR a, respectively. Corresponding BMDL/BMDU values of ECd/Ecr in women were 0.069/0.537 µg/g creatinine for NAG, while BMDL10/BMDU10 were 0.733/1.29 and 4.98/9.68 µg/g creatinine for the β2-microglobulinuria and low eGFR. |

Satarug et al. 2022 [89] |

| Protein excretion and low eGFR n = 405 (Bangkok, n =100, Mae Sot, n = 215), 19–87 years, Thailand |

BMDL/BMDU values of ECd/Ecr for protein loss in men were 0.021/0.757 µg/g creatinine, while BMDL5/BMDU5 values for proteinuria were 2.07/5.96 µg/g creatinine. Corresponding BMDL/BMDU values of ECd/Ecr in women were 0.023/0.913 µg/g creatinine, while BMDL5/BMDU5 values for proteinuria were 1.80/5.98 µg/g creatinine. In a whole group, BMDL/BMDU values of ECd/Ecr for protein loss were 0.054/0.872 µg/g creatinine, while BMDL5/BMDU5 values were 1.86/5.72 and 1.19/1.92 µg/g creatinine for proteinuria and low eGFR, respectively. |

Satarug et al. 2024 [82] |

| Prevalence of Adverse Outcome |

ECd/Ecr, µg/ g creatinine | (ECd/Ccr) ×100, µg/L filtrate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5% Albuminuria a | BMDL5 | BMDU5 | BMDU5/BMDL5 | BMDL5 | BMDU5 | BMDU5/BMDL5 |

| Males | 3.06 ×10−3 | 36.7 | 1.2 ×102 | 0.163 | 13 | 80 |

| Females | 1.22 ×10−2 | 3.05 ×105 | 2.5×107 | 0.718 | 154 | 60 |

| 10% Albuminuria | BMDL10 | BMDU10 | BMDU10/BMDL10 | BMDL10 | BMDU10 | BMDU10/BMDL10 |

| Males | 0.55 | 337 | 612 | 1.65 | 20 | 12 |

| Females | 2.52 | 1.74 ×106 | 6.7 ×105 | 3.55 | 2.12 | 60 |

| 5% CKD b | BMDL5 | BMDU5 | BMDU5/BMDL5 | BMDL5 | BMDU5 | BMDU5/BMDL5 |

| Males | 1.47 | 10.6 | 7.7 | 3.22 | 9.64 | 2.90 |

| Females | 1.93 | 15.6 | 8.08 | 3.33 | 9.20 | 2.26 |

| 10% CKD | BMDL10 | BMDU10 | BMDU10/BMDL10 | BMDL10 | BMDU10 | BMDU10/BMDL10 |

| Males | 3.92 | 15.7 | 4.00 | 5.61 | 13.4 | 2.39 |

| Females | 5.31 | 23.6 | 4.44 | 5.88 | 12.9 | 2.19 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).