Submitted:

10 April 2025

Posted:

11 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

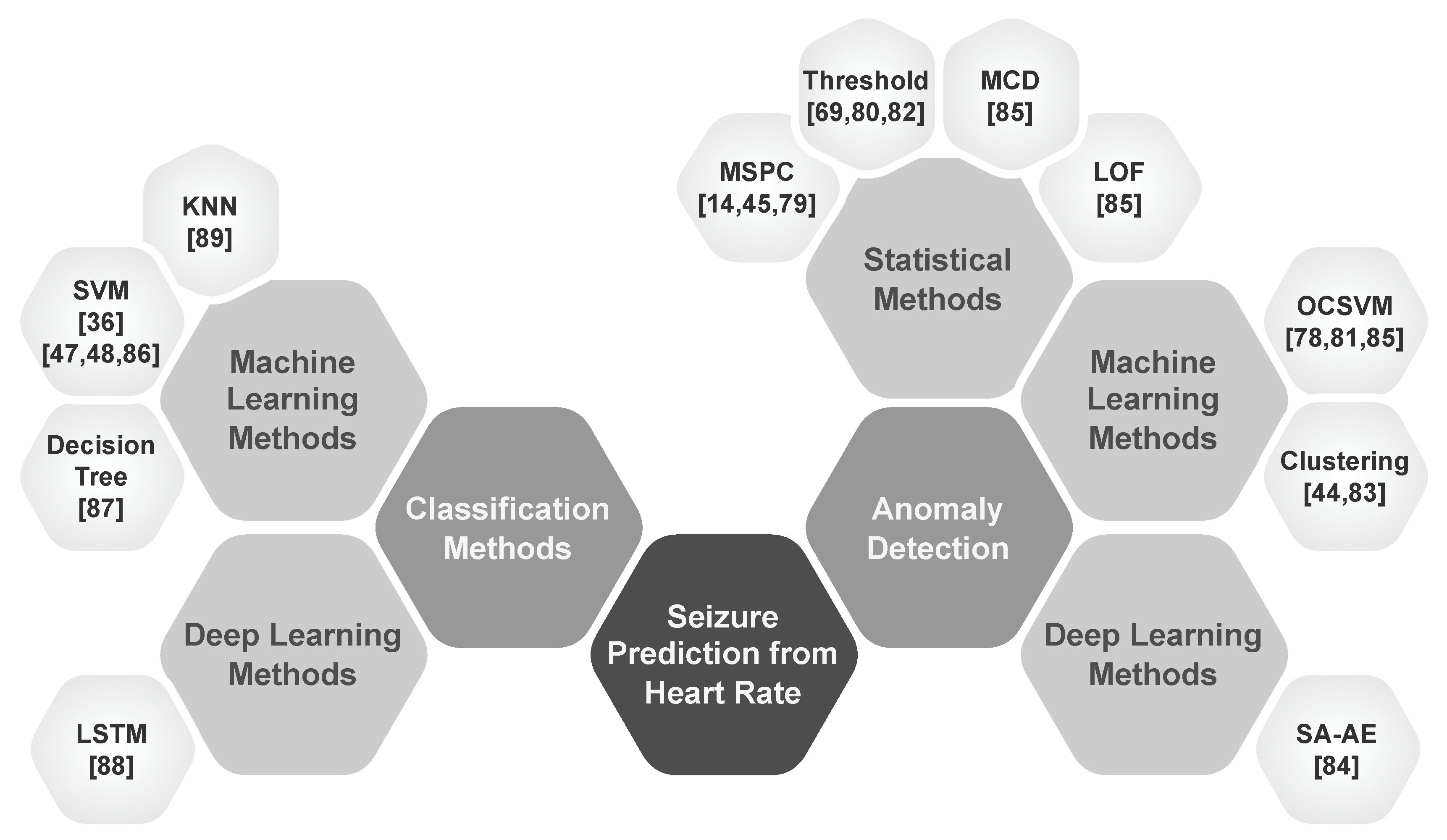

- Classification: Studies that develop models to classify seizure states by leveraging heart rate features to discriminate initial seizure states.

- Anomaly Detection: Studies that explore anomalies in heart rate linked to pre-ictal ANS activity as early indicators of impending seizures.

2. Epileptic Seizure and Cardiovascular System

2.1. Physiological Impacts of Epileptic Seizures

2.1.1. Autonomic Nervous System Dysfunction

2.1.2. Catecholamine Surge During Seizures

2.1.3. Direct Cortical and Subcortical Effects on Cardiovascular Regulation

2.1.4. Respiratory Compromise and Acidosis

2.2. Seizures Activities and Heart Rate

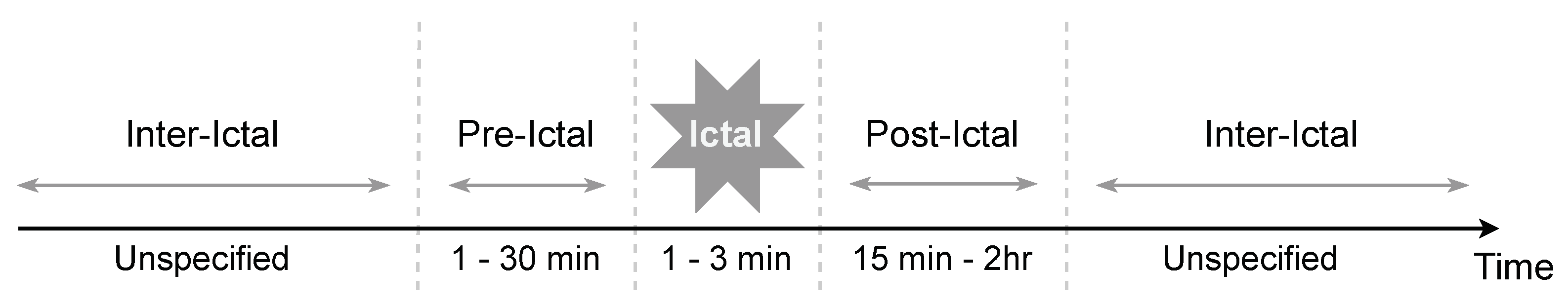

2.3. Seizure Stages and Heart Rate

2.3.1. Pre-Ictal Phase

2.3.2. Ictal Phase

2.3.3. Post-Ictal Phase

2.3.4. Inter-Ictal Phase

2.4. Impact of Seizure Types on Prediction

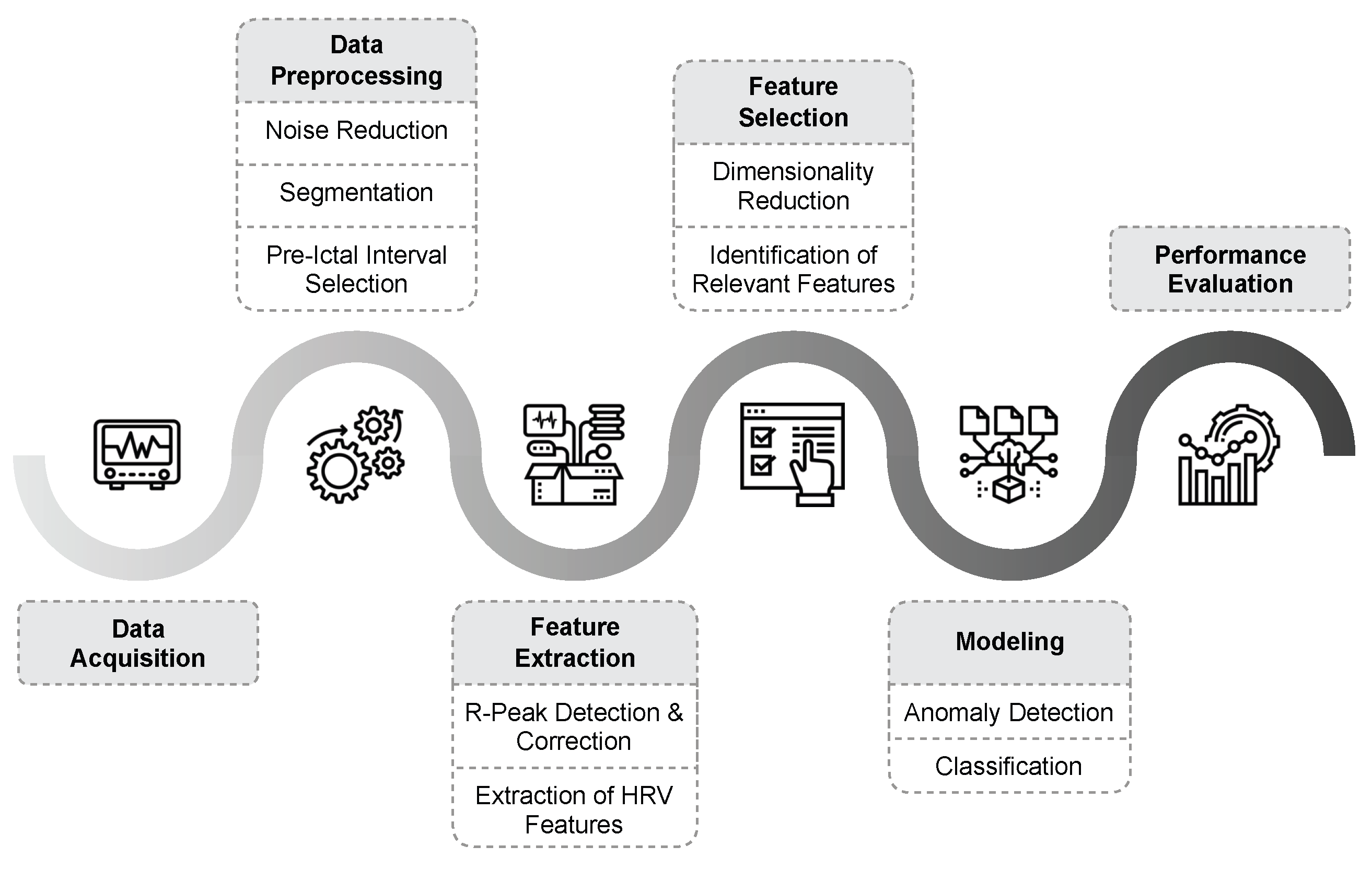

3. Epileptic Seizure Prediction

3.1. Data Acquisition

3.2. Data Preprocessing

3.2.1. Denoising and Filtering

3.2.2. Data Segmentation

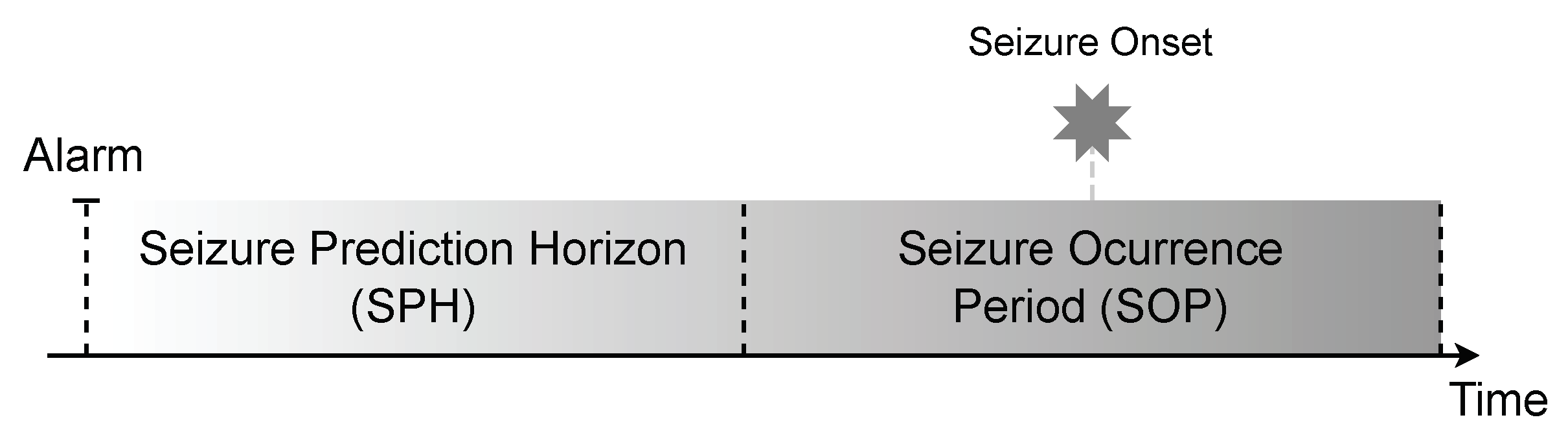

3.2.3. Pre-Ictal Interval Selection

3.3. Feature Extraction

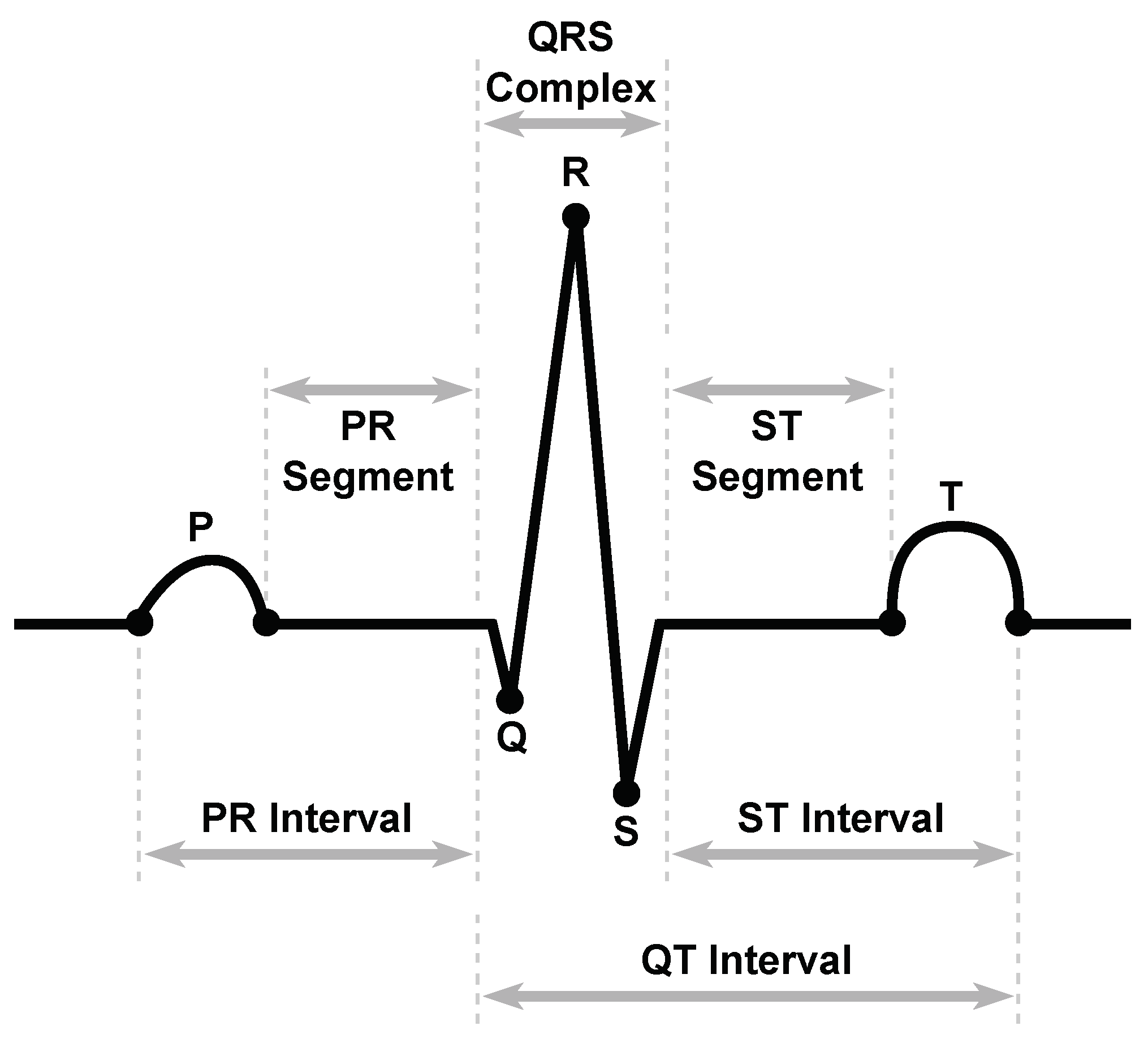

3.3.1. RR Interval Detection

3.3.2. RR Interval Correction

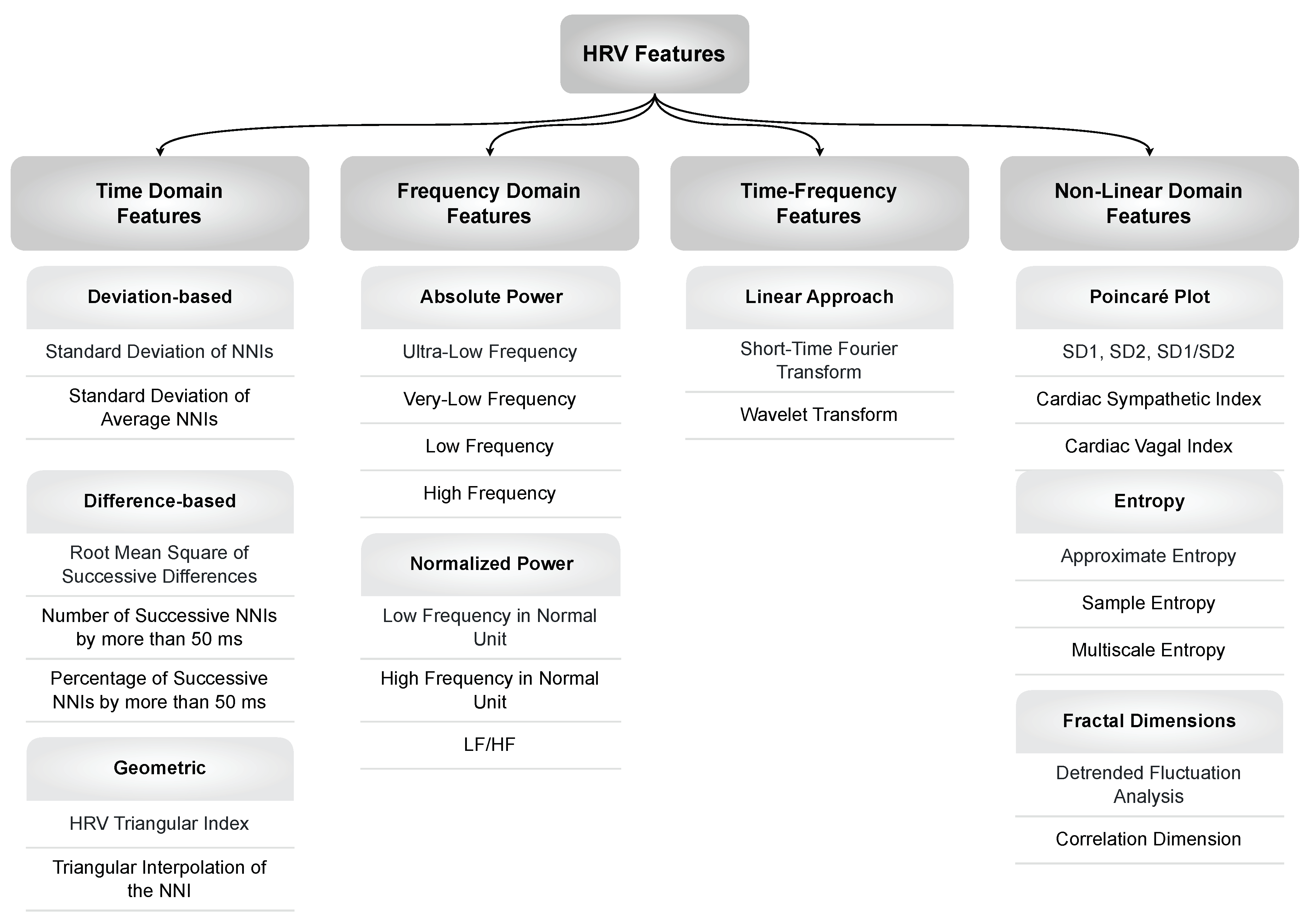

3.3.3. HRV Features

Time Domain Features

- Deviation-based features are based on the deviations between Interbeat Intervals (IBIs) from a moving average. These features can provide insight into the balance between the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems.

- Difference-based features make use of variations or differences between successive heart rate intervals. An analysis of these features may be useful for determining the patterns and trends of changes in HRV over time.

- Geometric features analyze the geometric patterns and structures of HRV and provide valuable knowledge about the overall dynamics of HRV, including short-term and long-term variations.

Frequency Domain Features

Time-Frequency Domain Features

Non-Linear Domain Features

3.4. Feature Selection

3.5. Seizure Prediction Models

3.5.1. Performance Evaluation

| Metric | Definition | Formula |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Percentage of correct predictions out of total predictions | |

| Precision | Percentage of true positive predictions out of all positive predictions | |

| Recall (Sensitivity) | Percentage of true positive predictions out of all actual positive cases | |

| Specificity | Percentage of true negative predictions out of all actual negative cases | |

| False Positive Rate (FPR) | Percentage of false positive predictions out of all actual negative cases | |

| F-measure | Harmonic mean of precision and recall |

| Authors | Year | Dataset | Patients | Features | Feature Selection | Window Size | Model | Evaluation | Detection time prior to onset | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specificity (%) | Sensitivity (%) | FPR (hr) | |||||||||

| Pre-Ictal Identification using Anomaly Detection Methods | |||||||||||

| Hashimoto et al. [14] | 2013 | TMDU | 5 | meanHR, SDNN, RMSSD, NN50, pNN50, HTI Total Power, LF, HF, LF/HF |

- | 3 min | Multivariate Statistical Process Control | - | - | - | At least one minute |

| Fujiwara et al. [78] | 2014 | TMDU | 5 | meanHR, SDNN, RMSSD, NN50, HTI Total Power, LF, HF, LF/HF |

- | 3 min | One-Class SVM | - | - | - | At least three minutes |

| Fujiwara et al. [79] | 2016 | Local | 14 | meanHR, SDNN, RMSSD, NN50 Total Power, LFnu, HFnu, LF/HF |

PCA | 3 min | Multivariate Statistical Process Control | - | 91% | 0.7/h | Up to 15 minutes |

| Behbahani et al. [80] | 2016 | EPILEPSIA | 16 | mean RRI HF, LF, LF/HF SD2/SD1 |

- | 5 min | Thresholding | - | 78.59% | 0.21/h | - |

| Smirnov et al. [81] | 2017 | Local | 31 | meanHR, SDNN, RMSSD, NN50 Total Power, LFnu, HFnu, LF/HF |

- | 3 min | One-Class SVM | 92% | 100% | - | - |

| Moridani et al. [82] | 2017 | PIHROPE | 7 | meanHR LF, HF, LF/HF Poincaré plot features |

- | 5 min | Thresholding | 86.20% | 88.30% | - | - |

| Yamakawa et al. [45] | 2020 | Local | 7 | meanHR, SDNN, RMSSD, NN50 Total Power, LF, HF, LF/HF |

- | 3 min | Multivariate Statistical Process Control | - | 85.70% | 0.62/h | About five minutes |

| Gagliano et al. [83] | 2020 | Local | 9 | meanHR, SDNN, RMSSD, NN50, pNN50, SDSD | - | - | 2-Class K-Means | - | - | - | Between 3.5 and 6.5 minutes |

| Ode et al. [84] | 2022 | Local | 39 | RRI | - | 45 sec | Self-Attentive Autoencoder | - | 74% | 0.85/h | - |

| Karasmanoglou et al. [85] | 2023 | PIHROPE | 7 | RMSSD SampEn, Poincaré Plot Features, KFD LF, HF, LF/HF, LFPeak, HFPeak |

PCA | - | Local Outlier Factor Minimum Covariance Determinant One-Class SVM |

93.1% 87.8% 96.6% |

95.6% 91.1% 92.4% |

- | Between 6 and 30 minutes |

| Behbahani et al. [69] | 2024 | EPILEPSIA | 16 | Poincaré Plot | - | 1-6 min | Thresholding | - | 80.42%, 75.19% | 0.15 | - |

| Discrimination between Inter-Ictal and Pre-Ictal using Classification Methods | |||||||||||

| Popov et al. [47] | 2017 | Local | 14 | 112 Features including Statistical Features Power Spectral Density-Based Features Non-Linear Features |

- | 1-10 min | SVM | 72.52% | 72.52% | - | - |

| Pavei et al. [48] | 2017 | Local PIHROPE |

12 | SDNN, RMSSD LF, HF SampEn, CSI and CVI from Lorenz Plot |

PCA | - | SVM | - | 94.10% | 0.49 | - |

| Billeci et al. [86] | 2018 | Siena | 15 | 20 Features including Statistical Features Frequency Features Non-Linear Features |

SRA | 3 min 1 min overlap |

Cost-Sensitive SVM | 89.34% | 89.06% | 0.41 | - |

| Giannakakis et al. [36] | 2019 | Heraklion | 9 | SDNN Total Power, LF/HF, LFnu, HFnu |

MRMR | - | SVM | Accuracy of 77.1% | 21.8 seconds | ||

| Perez-Sanchez et al. [87] | 2020 | PIHROPE | 7 | Wavelet Packet Transform (WPT) 17 Statistical Time Features |

KW | 1 min | Decision Tree | Accuracy of 100% | 15 minutes | ||

| Hadipour et al. [88] | 2021 | PIHROPE | 7 | meanHR, SDNN, RMSSD, total power past, next RRI, meanRRI, Five past Plus Five next RRI |

- | Assess iteratively | LSTM | 92% | 99% | - | - |

| Perez-Sanchez et al. [89] | 2024 | PIHROPE | 7 | Wavelet Packet Transform, Homogeneity Index | KW | 1 min | KNN | Accuracy of 93.25% | 20 minutes | ||

3.5.2. Anomaly Detection

3.5.3. Classification

4. Discussion

4.1. Challenges and Limitations

4.1.1. Limitation of Classification-Based Approaches

4.1.2. Limitation of Anomaly Detection-Based Approaches

4.2. Future Prospects

T-Wave Heterogeneity as a Biomarker

Data Labeling and Representation Learning

Anomaly Detection with Advanced Deep Learning Models

Automated Threshold Selection

Increasing Interpretability of the Decision-Making Process

5. Conclusion

References

- Robert S. Fisher, Carlos Acevedo, Alexis Arzimanoglou, Alicia Bogacz, J. Helen Cross, Christian E. Elger, Jerome Engel, Lars Forsgren, Jacqueline A. French, Mike Glynn, Dale C. Hesdorffer, B. I. Lee, Gary W. Mathern, Solomon L. Moshé, Emilio Perucca, Ingrid E. Scheffer, Torbjörn Tomson, Masako Watanabe, and Samuel Wiebe. ILAE Official Report: A Practical Clinical Definition of Epilepsy. Epilepsia, 55(4):475–482, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Milind Natu, Mrinal Bachute, Shilpa Gite, Ketan Kotecha, and Ankit Vidyarthi. Review on Epileptic Seizure Prediction: Machine Learning and Deep Learning Approaches. Computational and Mathematical Methods in Medicine, 2022:7751263, 2022. ISSN 1748-670X. [CrossRef]

- Elie Bou Assi, Laura Gagliano, Sandy Rihana, Dang K. Nguyen, and Mohamad Sawan. Bispectrum Features and Multilayer Perceptron Classifier to Enhance Seizure Prediction. Scientific Reports, 8(1):15491, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Nazanin Mohammadkhani Ghiasvand and Foad Ghaderi. Epileptic Seizure Prediction from Spectral, Temporal, and Spatial Features of EEG Signals Using Deep Learning Algorithms. The Neuroscience Journal of Shefaye Khatam, 9(1):110–119, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Sándor Beniczky, Philippa Karoly, Ewan Nurse, Philippe Ryvlin, and Mark Cook. Machine Learning and Wearable Devices of the Future. Epilepsia, 62 Suppl 2:S116–S124, 2021. S: 2. [CrossRef]

- Maeike Zijlmans, Danny Flanagan, and Jean Gotman. Heart Rate Changes and ECG Abnormalities During Epileptic Seizures: Prevalence and Definition of An Objective Clinical Sign. Epilepsia, 43(8):847–854, 2002. [CrossRef]

- Rachel E. Stirling, David B. Grayden, Wendyl D’Souza, Mark J. Cook, Ewan Nurse, Dean R. Freestone, Daniel E. Payne, Benjamin H. Brinkmann, Tal Pal Attia, Pedro F. Viana, Mark P. Richardson, and Philippa J. Karoly. Forecasting Seizure Likelihood with Wearable Technology. Frontiers in Neurology, 12:704060, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Roland D Thijs. The Autonomic Signatures of Epilepsy: Diagnostic Clues and Novel Treatment Avenues. Clinical Autonomic Research, 29:131–133, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Raffaele Manni, Gianpaolo Toscano, and Michele Terzaghi. Epilepsy and Cardiovascular Function: Seizures and Antiepileptic Drugs Effects. Brain and heart dynamics, pages 507–515, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Giorgio Costagliola, Alessandro Orsini, Monica Coll, Ramon Brugada, Pasquale Parisi, and Pasquale Striano. The Brain-Heart Interaction in Epilepsy: Implications for Diagnosis, Therapy, and SUDEP Prevention. Annals of Clinical and Translational Neurology, 8(7):1557–1568, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Claire Ufongene, Rima El Atrache, Tobias Loddenkemper, and Christian Meisel. Electrocardiographic Changes Associated with Epilepsy Beyond Heart Rate and Their Utilization in Future Seizure Detection and Forecasting Methods. Clinical Neurophysiology, 131(4):866–879, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Kenneth A. Myers, Shobi Sivathamboo, and Piero Perucca. Heart Rate Variability Measurement in Epilepsy: How Can We Move from Research to Clinical Practice? Epilepsia, 59(12):2169–2178, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Cristian Sevcencu and Johannes J. Struijk. Autonomic Alterations and Cardiac Changes in Epilepsy. Epilepsia, 51(5):725–737, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Hirotsugu Hashimoto, Koichi Fujiwara, Yoko Suzuki, Miho Miyajima, Toshitaka Yamakawa, Manabu Kano, Taketoshi Maehara, Katsuya Ohta, Tetsuo Sasano, Masato Matsuura, et al. Heart Rate Variability Features for Epilepsy Seizure Prediction. In 2013 Asia-Pacific Signal and Information Processing Association Annual Summit and Conference, pages 1–4. IEEE, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Federico Mason, Anna Scarabello, Lisa Taruffi, Elena Pasini, Giovanna Calandra-Buonaura, Luca Vignatelli, and Francesca Bisulli. Heart Rate Variability as a Tool for Seizure Prediction: A Scoping Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(3):747, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Soroor Behbahani. A Review of Significant Research on Epileptic Seizure Detection and Prediction Using Heart Rate Variability. Türk Kardiyoloji Derneği Arşivi, 46(5), 2018. [CrossRef]

- Eryse Amira Seth, Jessica Watterson, Jue Xie, Alina Arulsamy, Hadri Hadi Md Yusof, Irma Wati Ngadimon, Ching Soong Khoo, Amudha Kadirvelu, and Mohd Farooq Shaikh. Feasibility of Cardiac-Based Seizure Detection and Prediction: A Systematic Review of Non-Invasive Wearable Sensor-Based Studies. Epilepsia Open, 9(1):41–59, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Marije Van der Lende, Rainer Surges, Josemir W Sander, and Roland D Thijs. Cardiac Arrhythmias During or After Epileptic Seizures. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 87(1):69–74, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Fergus J Rugg-Gunn, Robert J Simister, Mark Squirrell, Diana R Holdright, and John S Duncan. Cardiac Arrhythmias in Focal Epilepsy: A Prospective Long-Term Study. The Lancet, 364(9452):2212–2219, 2004. [CrossRef]

- S Shmuely, M Van der Lende, RJ Lamberts, JW Sander, and Roland D Thijs. The Heart of Epilepsy: Current Views and Future Concepts. Seizure, 44:176–183, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Stephen M Oppenheimer and David F Cechetto. Cardiac Chronotropic Organization of the Rat Insular Cortex. Brain research, 533(1):66–72, 1990. [CrossRef]

- Adriana Leal, Maria da Graça Ruano, Jorge Henriques, Paulo de Carvalho, and César Teixeira. On the Viability of ECG Features for Seizure Anticipation on Long-Term Data. In 2017 IEEE 3rd International Forum on Research and Technologies for Society and Industry (RTSI), pages 1–5. IEEE, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Andrea Romigi and Nicola Toschi. Cardiac Autonomic Changes in Epilepsy. Complexity and Nonlinearity in Cardiovascular Signals, pages 375–386, 2017. [CrossRef]

- K. Jansen and L. Lagae. Cardiac Changes in Epilepsy. Seizure, 19(8):455–460, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Fedele Dono, Giacomo Evangelista, Valerio Frazzini, Catello Vollono, Claudia Carrarini, Mirella Russo, Camilla Ferrante, Vincenzo Di Stefano, Luciano P Marchionno, Maria V De Angelis, et al. Interictal Heart Rate Variability Analysis Reveals Lateralization of Cardiac Autonomic Control in Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Frontiers in neurology, 11:842, 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. Lüders, J. Acharya, C. Baumgartner, S. Benbadis, A. Bleasel, R. Burgess, D. S. Dinner, A. Ebner, N. Foldvary, E. Geller, H. Hamer, H. Holthausen, P. Kotagal, H. Morris, H. J. Meencke, S. Noachtar, F. Rosenow, A. Sakamoto, B. J. Steinhoff, I. Tuxhorn, and E. Wyllie. A New Epileptic Seizure Classification Based Exclusively on Ictal Semiology. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica, 99(3):137–141, 1999. ISSN 1600-0404. [CrossRef]

- Renzo Guerrini and Carmen Barba. Classification, Clinical Symptoms, and Syndromes. Oxford Textbook of Epilepsy and Epileptic Seizures, pages 70–80, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Katherine S. Eggleston, Bryan D. Olin, and Robert S. Fisher. Ictal Tachycardia: The Head-Heart Connection. Seizure, 23(7):496–505, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Paolo Detti. Siena Scalp EEG Database. PhysioNet, 10:493, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Paolo Detti, Giampaolo Vatti, and Garazi Zabalo Manrique de Lara. EEG Synchronization Analysis for Seizure Prediction: A Study on Data of Noninvasive Recordings. Processes, 8(7):846, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Ary L. Goldberger, Luis an Amaral, Leon Glass, Jeffrey M. Hausdorff, Plamen Ch Ivanov, Roger G. Mark, Joseph E. Mietus, George B. Moody, Chung-Kang Peng, and H. Eugene Stanley. Physiobank, Physiotoolkit, And Physionet: Components of A New Research Resource for Complex Physiologic Signals. circulation, 101(23):e215–e220, 2000. [CrossRef]

- I. C. Al-Aweel, K. B. Krishnamurthy, J. M. Hausdorff, J. E. Mietus, J. R. Ives, A. S. Blum, D. L. Schomer, and A. L. Goldberger. Postictal Heart Rate Oscillations in Partial Epilepsy. Neurology, 53(7):1590–1592, 1999. [CrossRef]

- Matthias Ihle, Hinnerk Feldwisch-Drentrup, César A. Teixeira, Adrien Witon, Björn Schelter, Jens Timmer, and Andreas Schulze-Bonhage. EPILEPSIAE - A European Epilepsy Database. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, 106(3):127–138, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Juliane Klatt, Hinnerk Feldwisch-Drentrup, Matthias Ihle, Vincent Navarro, Markus Neufang, Cesar Teixeira, Claude Adam, Mario Valderrama, Catalina Alvarado-Rojas, Adrien Witon, Michel van Quyen, Francisco Sales, Antonio Dourado, Jens Timmer, Andreas Schulze-Bonhage, and Bjoern Schelter. The EPILEPSIAE Database: An Extensive Electroencephalography Database of Epilepsy Patients. Epilepsia, 53(9):1669–1676, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Hirotsugu Hashimoto, Koichi Fujiwara, Yoko Suzuki, Miho Miyajima, Toshitaka Yamakawa, Manabu Kano, Taketoshi Maehara, Katsuya Ohta, Tetsuo Sasano, Masato Matsuura, and Eisuke Matsushima. Epileptic Seizure Monitoring by Using Multivariate Statistical Process Control. IFAC Proceedings Volumes, 46(31):249–254, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Giorgos Giannakakis, Manolis Tsiknakis, and Pelagia Vorgia. Focal Epileptic Seizures Anticipation Based on Patterns of Heart Rate Variability Parameters. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, 178:123–133, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Iwona Cygankiewicz and Wojciech Zareba. Heart Rate Variability. Handbook of clinical neurology, 117:379–393, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Sarang L Joshi, Rambabu A Vatti, and Rupali V Tornekar. A Survey on ECG Signal Denoising Techniques. In 2013 International Conference on Communication Systems and Network Technologies, pages 60–64. IEEE, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Shubhojeet Chatterjee, Rini Smita Thakur, Ram Narayan Yadav, Lalita Gupta, and Deepak Kumar Raghuvanshi. Review of Noise Removal Techniques in ECG Signals. IET Signal Processing, 14(9):569–590, 2020. ISSN 1751-9675. [CrossRef]

- Rahul Kher and Vallabh Vidyanagar. Signal Processing Techniques for Removing Noise from ECG Signals. Biomedical Engineering and Research, 3(1):1–9, 2019.

- Francisco P. Romero, David C. Piñol, and Carlos R. Vázquez-Seisdedos. DeepFilter: An ECG Baseline Wander Removal Filter Using Deep Learning Techniques. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control, 70:102992, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Siti Nurmaini, Annisa Darmawahyuni, Akhmad Noviar Sakti Mukti, Muhammad Naufal Rachmatullah, Firdaus Firdaus, and Bambang Tutuko. Deep Learning-Based Stacked Denoising and Autoencoder for ECG Heartbeat Classification. Electronics, 9(1):135, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Qiang Yin, Dai Shen, and Qian Ding. Influence of Sliding Time Window Size Selection Based on Heart Rate Variability Signal Analysis on Intelligent Monitoring of Noxious Stimulation under anesthesia. Neural Plasticity, 2021:6675052, 2021. ISSN 2090-5904. [CrossRef]

- Adriana Leal, Mauro F. Pinto, Fábio Lopes, Anna M. Bianchi, Jorge Henriques, Maria G. Ruano, Paulo de Carvalho, António Dourado, and César A. Teixeira. Heart Rate Variability Analysis for the Identification of the Preictal Interval in Patients with Drug-Resistant Epilepsy. Scientific Reports, 11(1):5987, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Toshitaka Yamakawa, Miho Miyajima, Koichi Fujiwara, Manabu Kano, Yoko Suzuki, Yutaka Watanabe, Satsuki Watanabe, Tohru Hoshida, Motoki Inaji, and Taketoshi Maehara. Wearable Epileptic Seizure Prediction System with Machine-Learning-Based Anomaly Detection of Heart Rate Variability. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland), 20(14), 2020. [CrossRef]

- Mojtaba Bandarabadi, Jalil Rasekhi, César A Teixeira, Mohammad R Karami, and António Dourado. On the Proper Selection of Preictal Period for Seizure Prediction. Epilepsy & Behavior, 46:158–166, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Anton Popov, Oleg Panichev, Yevgeniy Karplyuk, Yaroslav Smirnov, Sebastian Zaunseder, and Volodymyr Kharytonov. Heart Beat-To-Beat Intervals Classification for Epileptic Seizure Prediction. In 2017 Signal Processing Symposium (SPSympo), pages 1–4. IEEE, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Jonatas Pavei, Renan G. Heinzen, Barbora Novakova, Roger Walz, Andrey J. Serra, Markus Reuber, Athi Ponnusamy, and Jefferson L. B. Marques. Early Seizure Detection Based on Cardiac Autonomic Regulation Dynamics. Frontiers in Physiology, 8:765, 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Malik, J. T. Bigger, A. J. Camm, R. E. Kleiger, A. Malliani, A. J. Moss, and P. J. Schwartz. Heart Rate Variability: Standards of Measurement, Physiological Interpretation, and Clinical Use. European Heart Journal, 17(3):354–381, 1996. ISSN 0195-668X. [CrossRef]

- Tam Pham, Zen Juen Lau, S. H. Annabel Chen, and Dominique Makowski. Heart Rate Variability in Psychology: A Review of HRV Indices and an Analysis Tutorial. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland), 21(12):3998, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Anita Miftahul Maghfiroh, Syevana Dita Musvika, Levana Forra Wakidi, Lamidi Lamidi, Sumber Sumber, Muhmmad Ridha Mak’ruf, Andjar Pudji, and Dyah Titisari. State-of-the-Art Method to Detect R-Peak on Electrocardiogram Signal: A Review. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Electronics, Biomedical Engineering, and Health Informatics: ICEBEHI 2020, 8-9 October, Surabaya, Indonesia, pages 321–329. Springer, 2021. [CrossRef]

- TI Amani, SSN Alhady, UK Ngah, and ARW Abdullah. A Review of ECG Peaks Detection and Classification. In 5th Kuala Lumpur International Conference on Biomedical Engineering 2011: (BIOMED 2011) 20-23 June 2011, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, pages 398–402. Springer, 2011. [CrossRef]

- STEVEN E. DOBBS, NEIL M. SCHMITT, and HALUK S. OZEMEK. QRS Detection by Template Matching Using Real-Time Correlation on A Microcomputer. Journal of Clinical Engineering, 9(3):197, 1984. ISSN 0363-8855. [CrossRef]

- J. Pan and W. J. Tompkins. A Real-Time QRS Detection Algorithm. IEEE transactions on bio-medical engineering, 32(3):230–236, 1985. ISSN 0018-9294. [CrossRef]

- Ivaylo I. Christov. Real Time Electrocardiogram QRS Detection Using Combined Adaptive Threshold. BioMedical Engineering OnLine, 3(1):28, 2004. ISSN 1475-925X. [CrossRef]

- L. V. Rajani Kumari, Y. Padma Sai, and N. Balaji. R-Peak Identification in ECG Signals using Pattern-Adapted Wavelet Technique. IETE Journal of Research, pages 1–10, 2021. ISSN 0377-2063. [CrossRef]

- Jaeseong Jang, Seongjae Park, Jin-Kook Kim, Junho An, and Sunghoon Jung. CNN-Based Two Step R Peak Detection Method: Combining Segmentation and Regression. In 2022 44th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), pages 1910–1914. IEEE, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed Amine Belkadi, Abdelhamid Daamouche, and Farid Melgani. A Deep Neural Network Approach to QRS Detection Using Autoencoders. Expert Systems with Applications, 184:115528, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Xueyu Wu, Zhonghua Wang, Bo Xu, and Xibo Ma. Optimized Pan-Tompkins Based Heartbeat Detection Algorithms. In 2020 Chinese Control And Decision Conference (CCDC), pages 892–897. IEEE, 2020. [CrossRef]

- L Sathyapriya, L Murali, and T Manigandan. Analysis and Detection R-Peak Detection Using Modified Pan-Tompkins Algorithm. In 2014 IEEE International Conference on Advanced Communications, Control and Computing Technologies, pages 483–487. IEEE, 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Z. Fariha, R. Ikeura, S. Hayakawa, and S. Tsutsumi. Analysis of Pan-Tompkins Algorithm Performance with Noisy ECG Signals. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1532(1):012022, 2020. ISSN 1742-6596. [CrossRef]

- Dib Nabil and F. Bereksi Reguig. Ectopic Beats Detection and Correction Methods: A Review. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control, 18:228–244, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Mirja A. Peltola. Role of Editing of R-R Intervals in the Analysis of Heart Rate Variability. Frontiers in Physiology, 3:148, 2012. ISSN 1664-042X. [CrossRef]

- N. Lippman, K. M. Stein, and B. B. Lerman. Comparison of Methods for Removal of Ectopy in Measurement of Heart Rate Variability. The American journal of physiology, 267(1 Pt 2):H411–8, 1994. ISSN 0002-9513. [CrossRef]

- Davide Morelli, Alessio Rossi, Massimo Cairo, and David A Clifton. Analysis of the Impact of Interpolation Methods of Missing RR-intervals Caused by Motion Artifacts on HRV Features Estimations. Sensors, 19(14):3163, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Marcus Karlsson, Rolf Hörnsten, Annika Rydberg, and Urban Wiklund. Automatic Filtering of Outliers in RR Intervals Before Analysis of Heart Rate Variability in Holter Recordings: A Comparison with Carefully Edited Data. BioMedical Engineering OnLine, 11(1):2, 2012. ISSN 1475-925X. [CrossRef]

- Laurita dos Santos, Joaquim J. Barroso, Elbert E. N. Macau, and Moacir F. de Godoy. Application of An Automatic Adaptive Filter for Heart Rate Variability Analysis. Medical Engineering & Physics, 35(12):1778–1785, 2013. ISSN 1350-4533. [CrossRef]

- M. B. Malarvili, Mostefa Mesbah, and Boualem Boashash. Time-Frequency Analysis of Heart Rate Variability for Neonatal Seizure Detection. Australasian physical & engineering sciences in medicine, 29(1):67–72, 2006. ISSN 0158-9938. [CrossRef]

- Soroor Behbahani, Nader Jafarnia Dabanloo, Ali Motie Nasrabadi, and Antonio Dourado. Epileptic Seizure Prediction Based on Features Extracted from Lagged Poincaré Plots. International Journal of Neuroscience, 134(4):381–397, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Svante Wold, Kim Esbensen, and Paul Geladi. Principal Component Analysis. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems, 2(1-3):37–52, 1987. ISSN 0169-7439. [CrossRef]

- R. R. Hocking. A Biometrics Invited Paper. The Analysis and Selection of Variables in Linear Regression. Biometrics, 32(1):1, 1976. ISSN 0006341X. [CrossRef]

- Gary Smith. Step away from stepwise. Journal of Big Data, 5(1):1–12, 2018. ISSN 2196-1115. [CrossRef]

- Chris Ding and Hanchuan Peng. Minimum Redundancy Feature Selection from Microarray Gene Expression Data. Journal of bioinformatics and computational biology, 3(2):185–205, 2005. ISSN 0219-7200. [CrossRef]

- William H. Kruskal and W. Allen Wallis. Use of Ranks in One-Criterion Variance Analysis. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 47(260):583, 1952. ISSN 01621459. [CrossRef]

- Hossin M and Sulaiman M.N. A Review on Evaluation Metrics for Data Classification Evaluations. International Journal of Data Mining & Knowledge Management Process, 5(2):01–11, 2015. ISSN 2231-007X. ISSN 2231-007X. [CrossRef]

- Ž Vujović et al. Classification Model Evaluation Metrics. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications, 12(6):599–606, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Thomas Maiwald, Matthias Winterhalder, Richard Aschenbrenner-Scheibe, Henning U. Voss, Andreas Schulze-Bonhage, and Jens Timmer. Comparison of Three Nonlinear Seizure Prediction Methods by Means of the Seizure Prediction Characteristic. Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena, 194(3-4):357–368, 2004. ISSN 0167-2789. [CrossRef]

- Koichi Fujiwara, Erika Abe, Yoko Suzuki, Miho Miyajima, Toshitaka Yamakawa, Manabu Kano, Taketoshi Maehara, Katsuya Ohta, and Tetsuo Sasano. Epileptic Seizure Monitoring by One-Class Support Vector Machine. In Signal and Information Processing Association Annual Summit and Conference (APSIPA), 2014 Asia-Pacific, pages 1–4. IEEE, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Koichi Fujiwara, Taeko Sasai-Sakuma, Tetsuo Sasano, Masato Matsuura, Eisuke Matsushima, Miho Miyajima, Toshitaka Yamakawa, Erika Abe, Yoko Suzuki, Yuriko Sawada, Manabu Kano, Taketoshi Maehara, and Katsuya Ohta. Epileptic Seizure Prediction Based on Multivariate Statistical Process Control of Heart Rate Variability Features. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering, 63(6):1321–1332, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Soroor Behbahani, Nader Jafarnia Dabanloo, Ali Motie Nasrabadi, and Antonio Dourado. Prediction of Epileptic Seizures Based on Heart Rate Variability. Technology and Health Care, 24(6):795–810, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Yaroslav Smirnov, Anton Popov, Oleg Panichev, Yevgeniy Karplyuk, and Volodymyr Kharytonov. Epileptic Seizure Prediction Based on Singular Value Decomposition of Heart Rate Variability Features. In 2017 Signal Processing Symposium (SPSympo), pages 1–4. IEEE, 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. K. Moridani and H. Farhadi. Heart Rate Variability as A Biomarker for Epilepsy Seizure Prediction. Bratislavske lekarske listy, 118(1):3–8, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Laura Gagliano, E Bou Assi, Dènahin Hinnoutondji Toffa, Dang Khoa Nguyen, and Mohamad Sawan. Unsupervised Clustering of HRV Features Reveals Preictal Changes in Human Epilepsy. In 2020 42nd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), pages 698–701. IEEE, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Rikumo Ode, Koichi Fujiwara, Miho Miyajima, Toshikata Yamakawa, Manabu Kano, Kazutaka Jin, Nobukazu Nakasato, Yasuko Sawai, Toru Hoshida, Masaki Iwasaki, Yoshiko Murata, Satsuki Watanabe, Yutaka Watanabe, Yoko Suzuki, Motoki Inaji, Naoto Kunii, Satoru Oshino, Hui Ming Khoo, Haruhiko Kishima, and Taketoshi Maehara. Development of An Epileptic Seizure Prediction Algorithm Using R-R Intervals with Self-Attentive Autoencoder. Artificial Life and Robotics, pages 1–7, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Apostolos Karasmanoglou, Marios Antonakakis, and Michalis Zervakis. ECG-Based Semi-Supervised Anomaly Detection for Early Detection and Monitoring of Epileptic Seizures. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(6):5000, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Lucia Billeci, Daniela Marino, Laura Insana, Giampaolo Vatti, and Maurizio Varanini. Patient-Specific Seizure Prediction Based on Heart Rate Variability and Recurrence Quantification Analysis. PLOS ONE, 13(9):e0204339, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Andrea V. Perez-Sanchez, Carlos A. Perez-Ramirez, Martin Valtierra-Rodriguez, Aurelio Dominguez-Gonzalez, and Juan P. Amezquita-Sanchez. Wavelet Transform-Statistical Time Features-Based Methodology for Epileptic Seizure Prediction Using Electrocardiogram Signals. Mathematics, 8(12):2125, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Sarah Hadipour, Ala Tokhmpash, Bahram Shafai, and Carey Rappaport. Seizure Prediction and Heart Rate Oscillations Classification in Partial Epilepsy. In Advances in Computer Vision and Computational Biology: Proceedings from IPCV’20, HIMS’20, BIOCOMP’20, and BIOENG’20, pages 473–483. Springer, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Andrea V Perez-Sanchez, Juan P Amezquita-Sanchez, Martin Valtierra-Rodriguez, and Hojjat Adeli. A New Epileptic Seizure Prediction Model Based on Maximal Overlap Discrete Wavelet Packet Transform, Homogeneity Index, And Machine Learning Using ECG signals. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control, 88:105659, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ronald L. Allen and Duncan Mills. Signal Analysis: Time, Frequency, Scale, and Structure. John Wiley & Sons, 2004.

- Yuchun Tang, Yan-Qing Zhang, Nitesh V Chawla, and Sven Krasser. SVMs Modeling for Highly Imbalanced Classification. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Part B (Cybernetics), 39(1):281–288, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Paul Geladi and Bruce R Kowalski. Partial Least-Squares Regression: A Tutorial. Analytica chimica acta, 185:1–17, 1986. [CrossRef]

- Sotiris Kotsiantis, Dimitris Kanellopoulos, Panayiotis Pintelas, et al. Handling Imbalanced Datasets: A Review. GESTS international transactions on computer science and engineering, 30(1):25–36, 2006.

- Gen Li and Jason J. Jung. Deep Learning for Anomaly Detection in Multivariate Time Series: Approaches, Applications, And Challenges. Information Fusion, 91:93–102, 2023. ISSN 1566-2535. [CrossRef]

- Trudy D Pang, Bruce D Nearing, Richard L Verrier, and Steven C Schachter. T-Wave Heterogeneity Crescendo in the Surface EKG is Superior to Heart Rate Acceleration for Seizure Prediction. Epilepsy & Behavior, 130:108670, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Yuanhao ZOU, Yufei ZHANG, and Xiaodong ZHAO. Self-Supervised Time Series Classification Based on LSTM and Contrastive Transformer. Wuhan University Journal of Natural Sciences, 27(6):521–530, 2022. ISSN 1993-4998. [CrossRef]

- Yikai Yang, Nhan Duy Truong, Jason K. Eshraghian, Armin Nikpour, and Omid Kavehei. Weak Self-Supervised Learning for Seizure Forecasting: A Feasibility Study. Royal Society Open Science, 9(8):220374, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Yikai Gao, Aiping Liu, Lanlan Wang, Ruobing Qian, and Xun Chen. A Self-Interpretable Deep Learning Model for Seizure Prediction Using a Multi-Scale Prototypical Part Network. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering, 31:1847–1856, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Imene Jemal, Neila Mezghani, Lina Abou-Abbas, and Amar Mitiche. An Interpretable Deep Learning Classifier for Epileptic Seizure Prediction Using EEG Data. IEEE Access, 10:60141–60150, 2022. ISSN 2169-3536. [CrossRef]

- Mauro Pinto, Tiago Coelho, Adriana Leal, Fábio Lopes, António Dourado, Pedro Martins, and César Teixeira. Interpretable EEG Seizure Prediction Using a Multiobjective Evolutionary Algorithm. Scientific Reports, 12(1):4420, 2022. ISSN 2045-2322. [CrossRef]

| Datasets | Year | Recording Types |

Number of Patients |

Number of Seizures |

Seizure Types |

Sampling Frequency (Hz) |

Total Duration (H) |

Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Siena | 2020 | EEG ECG |

14 | 47 | Focal | 512 | 128 | [29,30,31] |

| PIHROPE | 2000 | ECG | 7 | 10 | Partial | 200 | > 16 | [31,32] |

| EPILEPSIA | 2010 | EEG ECG |

275 | > 2400 | Focal Generalized |

250 - 2500 | > 40000 | [33,34] |

| Heraklion | 2019 | ECG | 9 | 42 | Focal | 256 | > 1900 | [36] |

| Noise Type | Noise Source | Frequency Range (Hz) | Common Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Powerline Interference | Electrical appliances | 50/60 and harmonics | Notch filter |

| Baseline Wander | Body movement and Respiration | < 0.5 | High-Pass Filter |

| Electromyographic | Muscle activity | > 100 | Low-Pass or Band-Stop Filter |

| Electrode Motion | Electrode displacement | < 200 | Electrode Placement |

| Features | Unit | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Key Features | ||

| HR | bpm | The average number of heartbeats per minute. |

| RRI | ms | The time interval between two consecutive R-peaks |

| NNI | ms | Similarly, the time interval between two consecutive normal heartbeats. |

| Deviation-Based Features | ||

| SDNN | ms | Standard deviation of NN intervals |

| SDANN | ms | Standard deviation of short-term segments calculated from average NNIs. |

| Deviation-Based Features | ||

| RMSSD | ms | Root mean square of successive NN interval differences |

| NN50 | count | Counts the number of pairs of adjacent NNIs that differ by more than 50 ms. |

| pNN50 | % | Percentage of NNIs that differ by more than 50 ms. |

| Geometric Features | ||

| HTI | - | Integral of the density of the NN interval histogram divided by its height |

| TINN | ms | Baseline width of the triangular interpolation of the highest peak of all NN intervals |

| Features | Unit | Description | Frequency Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Key Features | |||

| TP | Total variance of HRV | ≤ 0.4 Hz | |

| Absolute Power | |||

| ULF | Power in the range of ultra-low frequencies | ≤ 0.003 Hz | |

| VLF | Power in the range of very low frequencies | 0.003 - 0.04 Hz | |

| LF | Power in the range of low frequencies | 0.04 - 0.15 Hz | |

| HF | Power in the range of high frequencies | 0.15 - 0.4 Hz | |

| Normalized Power | |||

| LFnu | % | Normalized power in the low frequency band | - |

| HFnu | % | Normalized power in the high frequency band | - |

| LF/HF | - | Ratio of LF to HF power | - |

| Non-linear Domain Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Poincaré Plot | |

| Standard Deviation 1 (SD1) | Represents the dispersion of points along the identity line in the Poincaré plot. |

| Standard Deviation 2 (SD2) | Represents the dispersion of points perpendicular to the identity line in the Poincaré plot. |

| SD1/SD2 ratio | The ratio of short-term to long-term variability in the Poincaré plot. |

| Cardiac Sympathetic Index (CSI) | Measures the irregularity of HRV dynamics. |

| Cardiac Vagal Index (CVI) | Reflects the tendency of the heart to transition from stable to unstable dynamics. |

| Entropy | |

| Approximate Entropy (ApEn) | Quantifies the regularity and complexity of HRV time series. |

| Sample Entropy (SampEn) | Similar to ApEn, quantifies HRV irregularity and complexity, robust to noise. |

| Multiscale Entropy (MSE) | Measures HRV complexity over multiple timescales, including short and long-term dynamics. |

| Fractal Dimensions | |

| Detrended Fluctuation Analysis (DFA) | Identifies fluctuations in HRV correlations, providing insight into long-term self-similarity. |

| Correlation Dimension (CD) | Characterize HRV complexity and structure using phase space reconstruction. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).