1. Introduction

Green tides, caused by the extensive growth and accumulation of unattached green macroalgal, have been increasing in both severity and geographical extent globally, primarily driven by the eutrophication of marine environments [

1,

2]. The world’s largest green tide, driven by

Ulva prolifera, have occurred annually in the Yellow Sea since 2007 [

3,

4,

5]. These floating green tides significantly impact marine ecosystems by disturbing zooplankton communities, altering seawater chemistry, reducing phytoplankton biomass, and even modifying the carbonate system [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Additionally, the accumulation of algae on beaches and in coastal waters disrupts the balance of coastal ecosystems, leads to the death of cultured organisms, and affects tourism [

2,

10,

11]. As a result, these events have caused significant economic losses. Between 2008 and 2015, the combined costs of mitigation efforts and aquaculture losses due to green tide blooms were estimated to be approximately 350 million U.S. dollars [

2,

12,

13].

Unlike other green tides around the world, floating algal mats in the Yellow Sea do not remain in their original blooming region, but drifted to the open area driven by surface winds and associated currents [

4,

14,

15,

16,

17]. Eventually, most of these algae wash ashore along the coasts of Shandong and Jiangsu provinces in China, and even the west coast of South Korea [

4,

16,

18]. During their long-distance transport, the green macroalgae rapidly grow under favorable conditions of light, temperature and nutrient [

4,

19,

20,

21], forming large-scale green tides characterized by both extensive affected areas and high biomass production [

4,

21,

22].

The entire process of long-distance movement and the scale of

Ulva prolifera blooms show strong temporal and spatial variability, which is influenced by changing environmental conditions or human activities, such as wind and current patterns, light and nutrient availability, and the management of

Porphyra yezoensis seaweed cultivation [

15,

19,

20,

23,

24]. Understanding these variations and their underlying causes is crucial for assessing the impact of green tides on biogeochemical systems and for developing effective management strategies. Moreover, the spatiotemporal variation of

Ulva prolifera has drawn significant public attention since the first sudden outbreak in 2007, due to its close ties with marine aquaculture and tourism industries.

Satellite tracking methods, which can capture and instantaneously record Earth’s surface information, have provided a comprehensive view of spatiotemporal dynamics of green tides [

3,

5,

12,

23,

25]. In addition, various attempts, including field and laboratory research combined with ecological modeling, has been devoted to explain the observed patterns [

19,

20,

23,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. This review focuses on the current understanding of the unique characteristics of green tides in the Yellow Sea, particularly their long-distance movement and the interannual variability of bloom size. We also briefly discuss the underlying mechanisms driving these fluctuations.

2. Diversified Macroalgae Monitoring Realized by Remote Satellites

Multiple satellite data are used for macroalgae monitoring, with MODIS optical imagery being the most widely used due to its large swath width (2330 km) and frequent revisit capacity (morning and afternoon passes) [

31]. However, its relatively coarse resolution (250m) may miss small macroalgal patches and lead to an overestimation of total macroalgal coverage [

32,

33]. This limitation also applies to green algal detection using COMS GOCI (500m) imagery. To address this issue, satellites with finer resolution, such as the Landsat series, Sentinel 1A/2A, HJ 1A/1B and GF series, are increasingly used for bloom monitoring [

7,

34]. In addition to optical imagery, microware data, with their all-day and all-weather observation capability, serve as an effective supplement for monitoring

Ulva prolifera blooms.

In satellite optical images, macroalgae can be detected using vegetation index threshold method, including the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) [

3], the Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI) [

35] and the Modified Normalized Difference Algae Index (NDAI) [

36]. These indices are effective due to the spectral similarity between macroalgae and terrestrial vegetation [

37]. However, both modified and simple vegetation indices are often less sensitive to variations in environmental and observational conditions, such as aerosols and changes in solar/viewing geometry [

38]. To address these limitations, several specialized algae indices have been developed to improve detection accuracy. These include the Floating Algae Index (FAI) [

38], the Scaled Algae Index (SAI) [

39], the Virtual-Baseline Floating macroAlgae Height (VB-FAH) index [

33], the Difference of Vegetation Index (DVI) [

33] and the Floating Green Algae for GOCI (IGAG) index [

35,

40].

In contrast, macroalgal pixels in microwave imagery can also be extracted using threshold methods, leveraging the distinctive backscattering characteristics of the microwave bands [

31,

32]. It is important to note that macroalgae often appear in the form of stripes or irregularly shaped patches. As a result, the macroalgae pixels identified in satellite images are frequently mixed with surrounding non-algal features [

15,

31].

To address this challenge, alternative approaches, such as the linear pixel unmixing, image composition and machine learning, have been employed to more accurately estimate algae coverage by integrating both moderate- and coarse-resolution data [

23,

31,

41,

42]. Furthermore, a multi-sensor, multi-temporal and multi-spatial (3M) remote sensing strategy has been utilized to monitor macroalgal blooms [

20]. Overall, advancements in methodologies and the application of comprehensive analytical tools have significantly improved the understanding and quantification of the spatial-temporal variations of green tides, with remote sensing technologies playing a crucial role in this progress.

3. Spatio-Temporal Variation in the Long-Distance Transport of Green Tides

3.1. Long-Distance Drifting

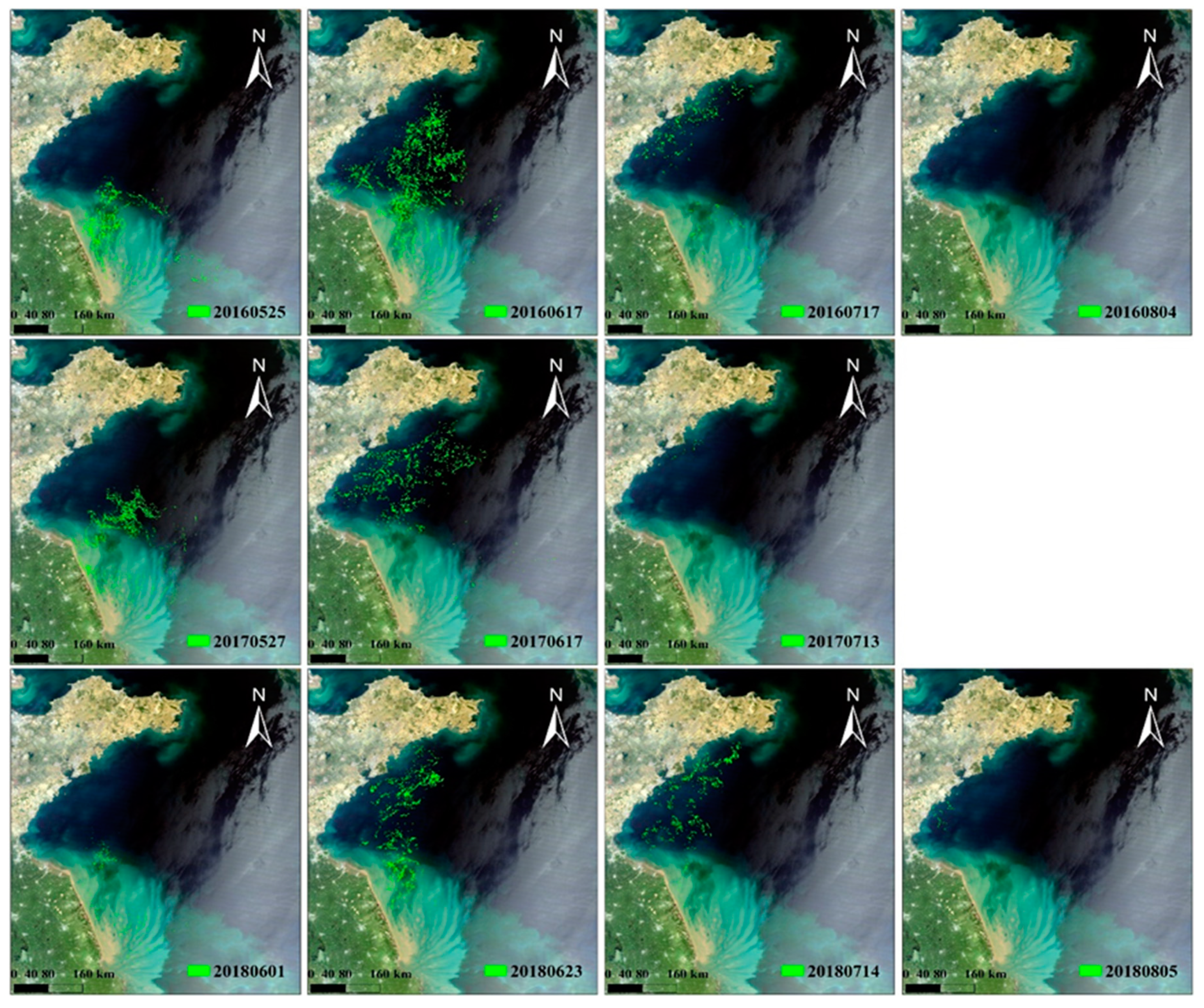

The most distinctive and well-known feature of the green tides in the Yellow Sea is their seasonal long-distance northward transport (

Figure 1). Satellites observations have documented that the floating

Ulva prolifera initially originates from the

Porphyra yezoensis cultivation area in the Jiangsu Shoal in late April and early May [

5,

43,

44]. After being released into the sea during facility recycling,

Ulva prolifera drifts out of Subei Shoal and grows rapidly under favorable light, temperature and nutrient conditions [

16,

19,

21]. Driven by the seasonal monsoon and the associated surface currents [

14,

45], large floating mats of

Ulva prolifera aggregate into long, extensive patches, often distributed as irregularly shaped stripes or clusters [

10,

15,

31]. These mats reach their peak size in mid-June, and then land along the southern coast of Shandong province [

46]. Afterward, the

Ulva prolifera green tides begin to decline, with floating mats only being sporadically observed in the coastal areas in early August [

16].

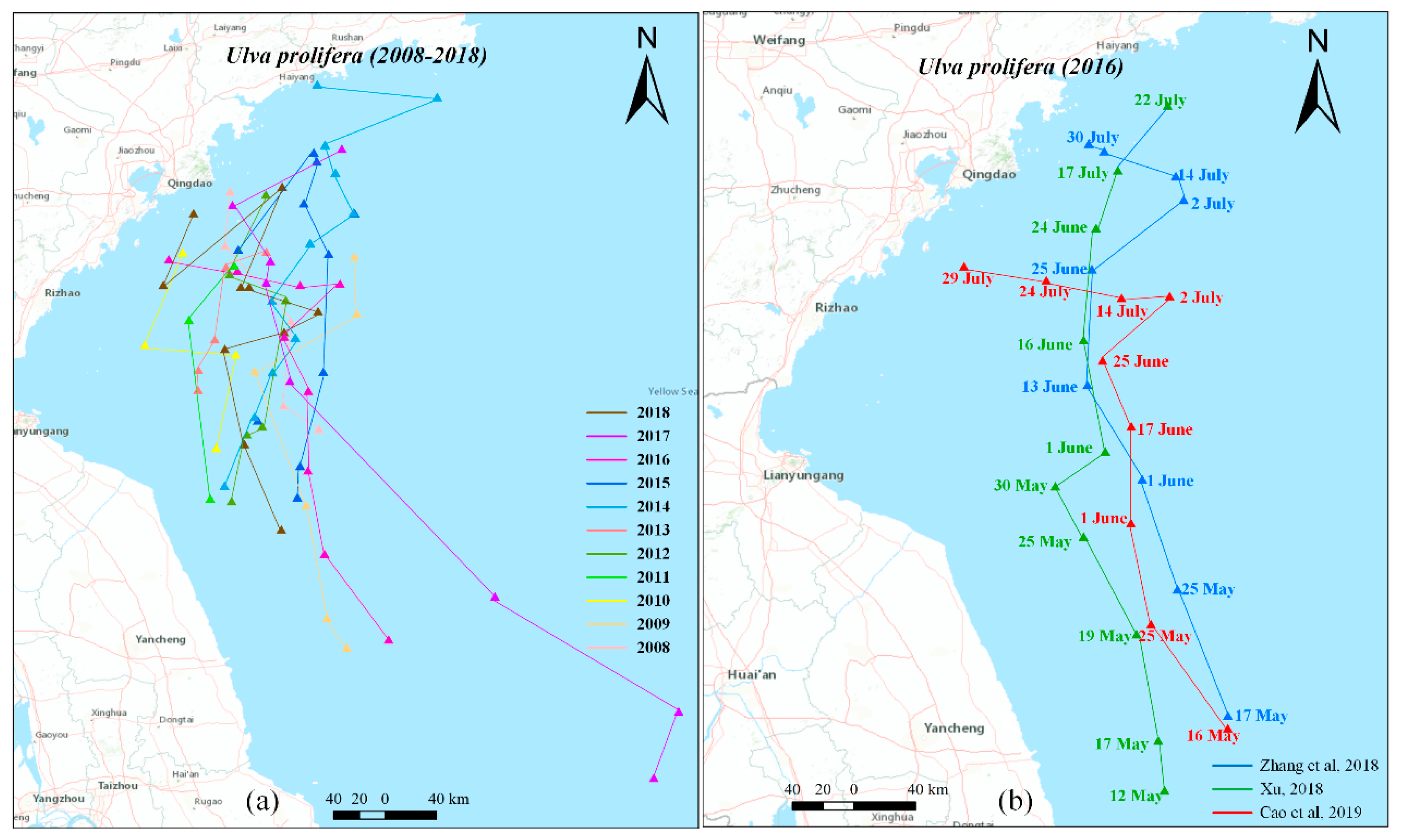

This seasonal northward drift exhibits significant interannual variability in both the spatiotemporal distribution of

Ulva prolifera and the duration of the bloom, as indicated by the sequence of

Ulva prolifera locations identified from satellites images annually (

Figure 1). For example, comparing the extensive

Ulva prolifera blooms of 2016-2018 (

Figure 1), the green tides in 2016 clearly had the widest extension and longest duration, in contrast to 2017 and 2018. When focusing on the comparison of the spatiotemporal distribution of

Ulva prolifera since 2007, the quantified migration trajectory, obtained through calculation of the geometric or barycenter positions, clearly illustrate the interannual variation such as differences in offshore distance or discrepancies in migration along the north-south or east-west direction (

Figure 2a) [

46,

47,

48]. Although there are some discrepancies due to the different approaches used to obtain the spatiotemporal information of green macroalgae, such as the migration trajectory in 2016 (

Figure 2b), the floating path consistently exhibits a trend of gradual northward drift. Furthermore, as shown in

Table 1, the duration of the bloom during this northward movement varies significantly from year to year (

Table 1).

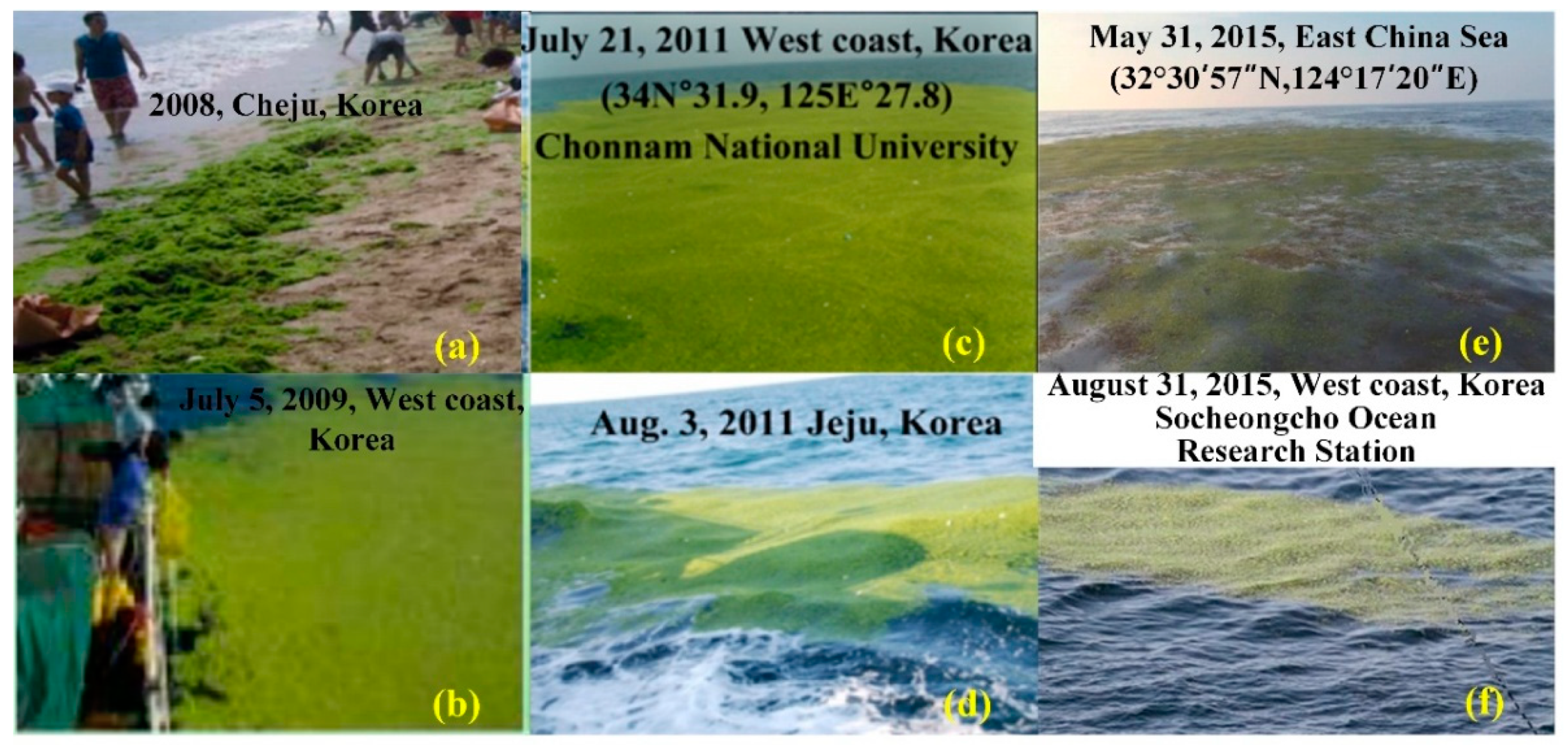

In addition to the primary northward path, rafting green macroalgae has been consistently observed in the eastern Yellow Sea and even off the west coast of Korea (

Figure 3), indicating a new eastward migration route for the green tides. Research has confirmed that this eastward migration occurred in 2008, 2009, 2011, 2012, 2015 and 2016 [

18,

33,

35,

40,

50,

51]. Less than 4% of the green tide areas in the western Yellow Sea (except for 2011 with 44%) was transported to the eastern Yellow Sea [

18]. Along this eastward transport, the area of green tide masses significantly decreased due to limited reproduction and sinking, which may be attributed to the relatively lower nutrient levels in the middle Yellow Sea [

51]. Compared to the main northward drift, the eastward drift of the green algae is characterized by a lower frequency of occurrence and smaller biomass. However, it could lead to problems similar to those experienced in China if the green tide eventually reaches the coast of Korean Peninsula. Little is known about the abnormal eastward transport, including bloom formation and spatiotemporal characteristics of this migration.

3.2. Final Landing and Decomposing Process

The end of the long-distance drift is marked by portions of the floating green algae accumulating along the southern coast of Shandong Province, while the remaining algae in the water sink to the seabed and decompose [

53,

54]. The washing ashore of

Ulva prolifera caused destructive damage to coastal aquaculture, incurred substantial costs for clearing macroalgal biomass, and resulted in indirect negative effects on the tourism industry and environmental problems [

16,

30,

55]. Oxygen depletion, along with the release of sulfide and ammonia during the decomposition of

Ulva prolifera, is responsible for the mortality of abalone and sea cucumbers [

56]. Additionally, the nutrient release during the decay of green tides is suspected to promote blooms of toxic microalgae, commonly known as “red tides” [

57,

58]. Thus, the final landing and decomposition processes are closely linked to human activities and livelihoods. Unfortunately, knowledge regarding the spatiotemporal variation of these processes remains scarce.

Current studies indicate that the landing sequence of green tides is highly variable. An et al. [

59] documented that the order in which macroalgae landed on the coastal cities of Shandong Peninsula can be roughly divided into two patterns. In one pattern, the macroalgae first landed in Rizhao, followed by Qingdao, Rushan, and Haiyang. In the other pattern, the order was reversed. The largest amount of seaweed biomass has typically been washed ashore along the coasts of Qingdao. Since 2015, the coasts of Lianyungang and Rizhao have been severely affected by unprecedent large stranding biomass [

17]. Despite this, other landing variables, such as the duration of the landing and landing volumes biomass, can also vary significantly, however, little is known about these aspects so far.

The final decomposition process of

Ulva prolifera typically concludes in August (

Table 1). According to the distribution pattern of 28-isofucosterol content in August 2015, the potential settlement region was identified in the sea area southeast of the Shandong Peninsula, around 122.66°E, 36.00°N [

54]. Based on spatial distribution of

Ulva prolifera during dissipation phase, An et al. [

59] expanded the potential settlement region to include the coastal waters of the Shandong Peninsula and the central waters of the South Yellow Sea (33°31’N ~ 35°22’ N, 120°14 ‘E ~ 122°8’ E). This study revealed significant yearly variations in the final settlement regions: offshore settlements were located in the central waters of the South Yellow Sea in 2007, 2010, 2014, 2015, and 2019, while inshore settlements were found in the coastal waters of the Shandong Peninsula in other years. Similarly, based on the spatial distribution of green tides over their dissipation periods, Li et al. [

60] suggested that the centers of dissipation of green tides over the years have been located along the coast of the Shandong Peninsula, with a radius of about 80 km, centered around Qingdao. Utilizing remote sensing data with higher spatial resolutions combined with C/N values, Zhang et al. [

61] identified the primary decomposition regions are located in the coastal zone south of the Shandong Peninsula (35.2−37°N, 120.3−123 °E). However, without laboratory measurements to verifies findings, the reliability of the satellite-estimated results remains uncertain.

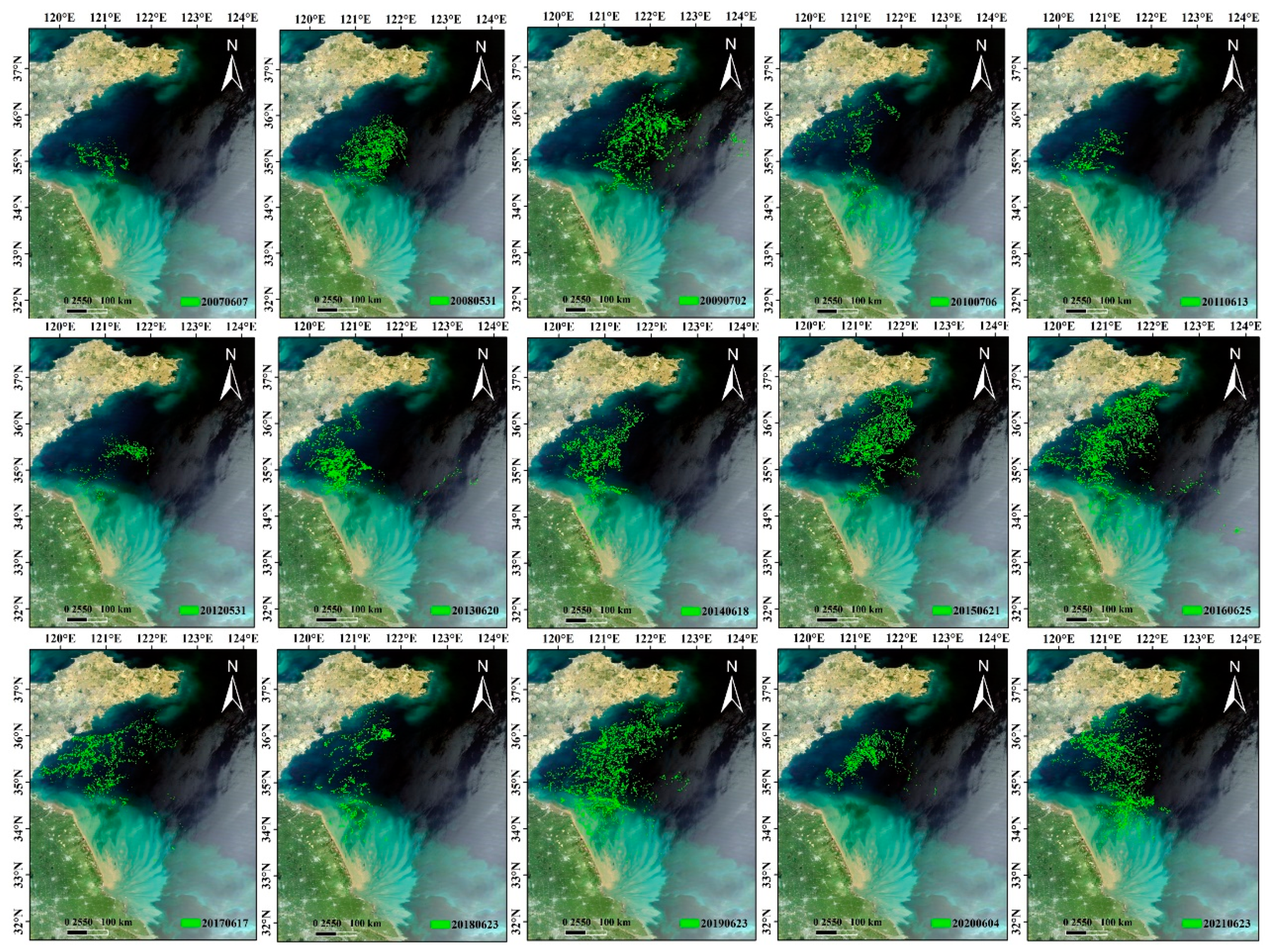

4. Interannual Variability in the Size of Green Tide Bloom

The bloom size, typically expressed by the annual maximum daily macroalgal biomass, can be intuitively displayed through satellite observations. As shown in

Figure 4, the spatiotemporal characteristic of green tides, including their geographical distribution and annual extension patterns, are clearly depicted. In addition to these intuitive and visual representations, another common approach involves quantifying the macroalgal coverage or biomass.

4.1. Macroalgae Coverage

Two common methods are used to quantify the bloom size of

Ulva prolifera: algae-mixed pixel coverage, which represents a collection of pixels corresponding to

Ulva prolifera identified directly from remote sensing images under the pure pixel assumption [

10,

20], and pure algae coverage, which is derived by correcting for the mixed pixel effect [

12,

13,

31,

34]. Using proxies such as the maximum daily

Ulva prolifera algae-mixed pixel coverage or pure algae coverage, several studies have been conducted to explore the interannual variations in bloom size [

10,

23,

31,

34,

63].

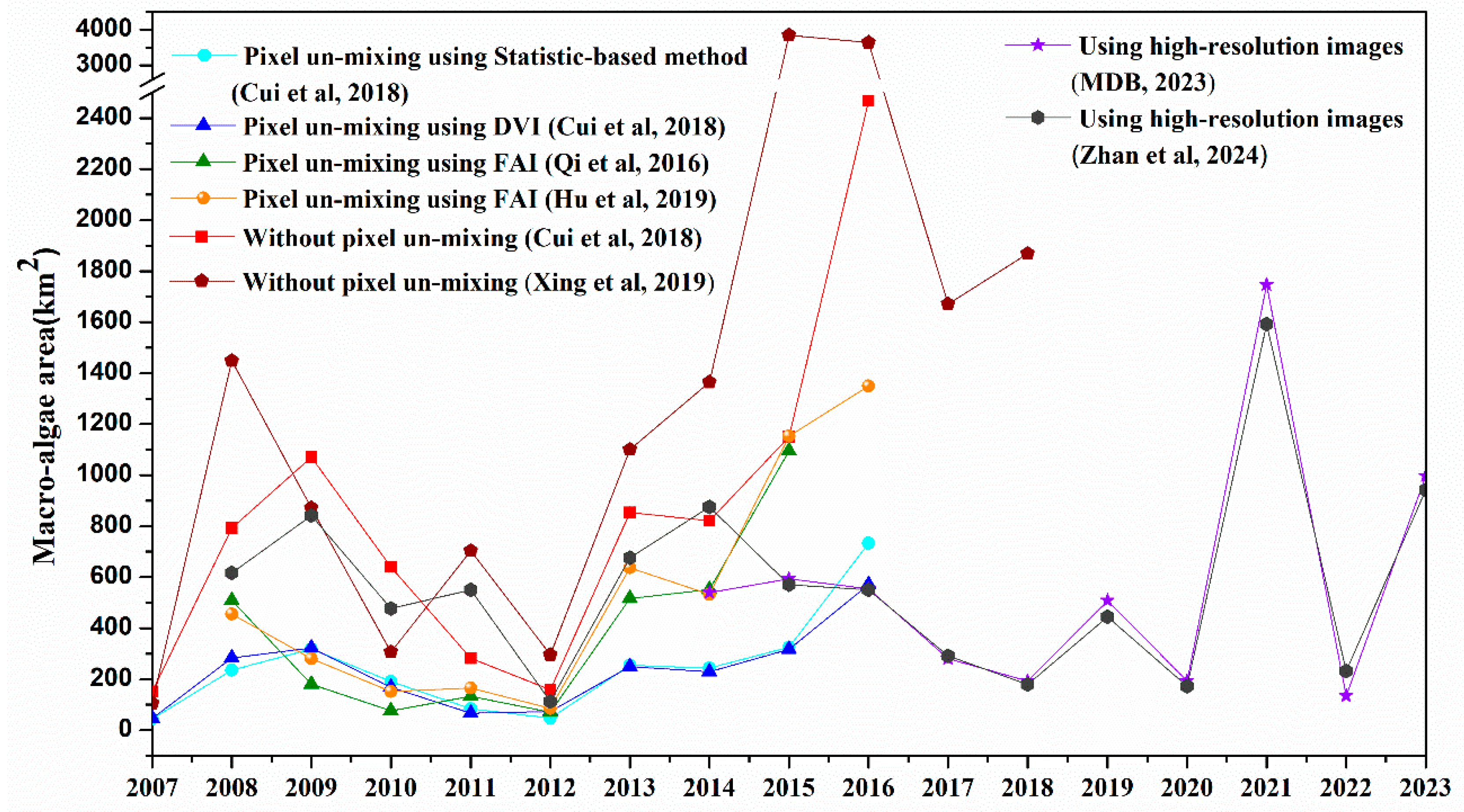

As summarized in

Figure 5, the bloom size of green tides exhibited significant interannual changes, with notable discrepancies observed across years. When comparing the yearly macroalgae coverage expressed in the two areal forms mentioned above, the algae-mixed pixel coverage was found to be 1.5 to 20.0 times higher than the pure algae coverage, likely due to the mixed pixel effect [

31]. After processing the pixel un-mixing, the discrepancies were reduced to no more than 2.0 times for the macroalgae coverage obtained by Cui et al., Qi et al. and Hu et al. from 2008 to 2012 [

23,

31,

34]. However, relatively higher differences, ranging from 2.5 to 3.6 times, were observed in the pure algae coverage from 2013 to 2018. Cui et al. attributed these discrepancies to differences in methodology, such as variations in the indices used, how algae-containing pixels were treated, and the thresholds applied for distinguishing algae from surrounding water during pixel un-mixing [

31]. The extraction area obtained from relatively high-resolution images closely approximated the true value [

64]. Thus, even without pixel unmixing, the extraction areas derived from high-resolution images exhibited a high degree of consistency between MDB [

65] and Zhan et al. [

66] since 2015.

In addition to the most striking numerical difference, the yearly fluctuations also exhibit considerable variation (

Figure 5). For instance, the peak year, either before or after 2012 (which had the lowest algae coverage), varied significantly. Before 2012, studies by Cui et al. [

31] and Zhang et al. [

10] identified a sudden burst in 2009, while other studies reported the peak year as 2008. This inconsistency is also observed in other researches (

Figure 5). After 2012, according to MDB [

65] and Zhan et al. [

66], the maximum daily coverage was in 2021. The distinct methodological differences and inconsistent thresholds, as mentioned above, are certainly responsible for this inconsistency [

67]. Besides, the daily maximum obtained from cloud-free day may be several days or weeks away from the real maximum day, the differences in the identified maximal bloom day across studies may be the main factor contributing to this inconsistency (

Table 2) [

67]. To address this issue, Qi et al. [

41] applied image composition to remove clouds and other artifacts to estimate monthly mean biomass and bloom size.

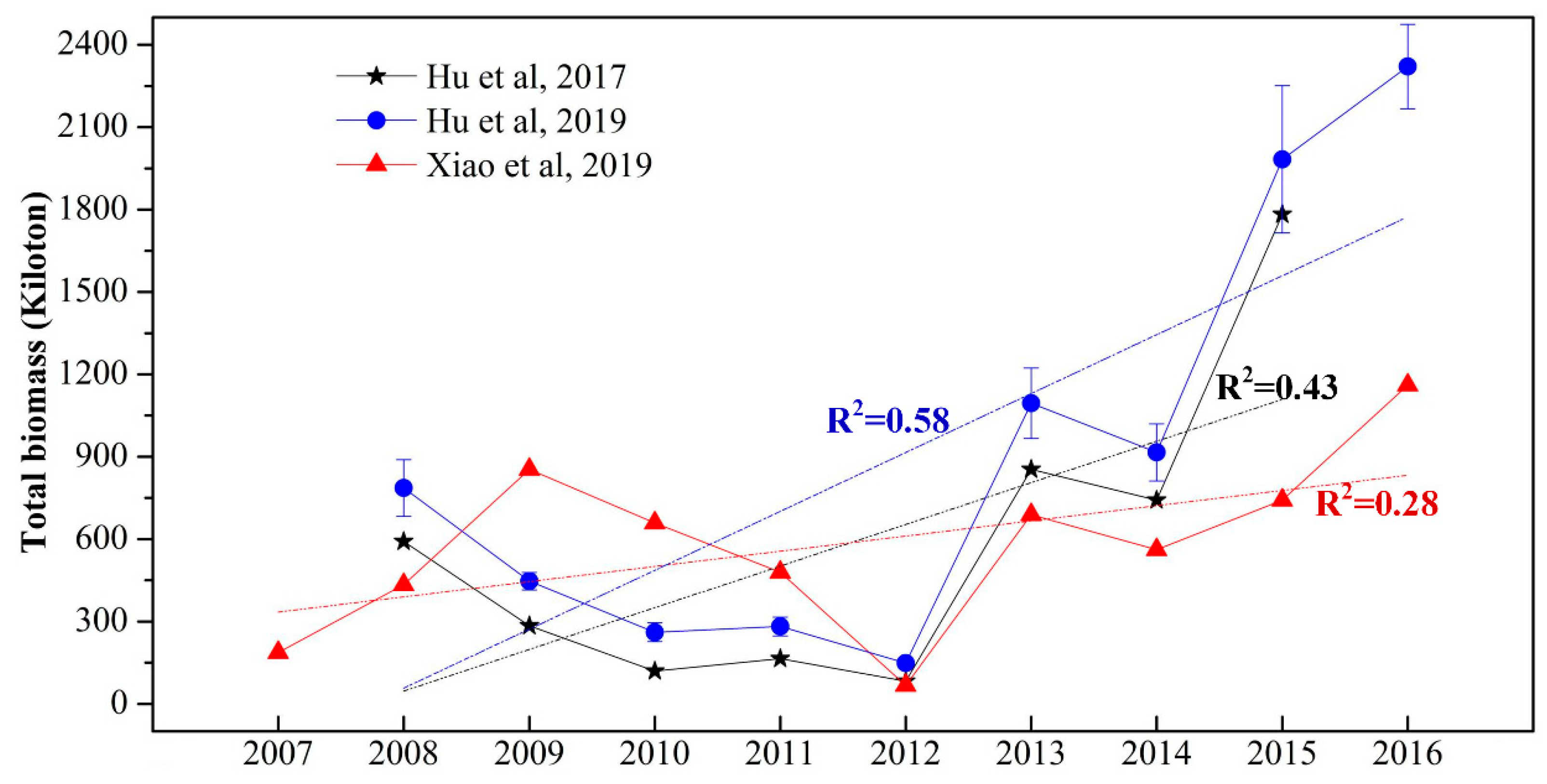

4.2. Macroalgae Biomass

Total biomass, compared to the coverage area, provides a more reliable indicator of the severity of green tide blooms. However, while extensive research has focused on the macroalgae coverage, studies on biomass estimation remain relatively scarce [

12,

13,

34]. In practice, the biomass of green tides is mostly derived by converting pure algae coverage using specific conversion equations. Thus, the interannual patterns (

Figure 6) of macro-algal biomass closely resemble those of macro-algal coverage. Similar to coverage, significant discrepancies exist in these biomass estimates. For instance, the maximum biomass for 2016, estimated by Hu et al. [

34] at around 2321±154 kilotons, is nearly twice the biomass estimate (approximately 1190 kilotons) reported by Xiao et al. [

13]. Meanwhile, there is also clear increasing trend in the quantified macro-algal biomass, with R2 value ranging from 0.28 to 0.58 (

Figure 6).

Significantly, all the algal biomass estimates made so far have neglected the influence of floating algae thickness on estimation accuracy. Lu et al. indicated that the thickness effects contribute approximately 36% to the uncertainty in total biomass estimation, while around 43% of the overall uncertainty is attributed to a few pixels with high MODIS-derived FAI values (FAI >0.05) [

69].

5. Factors Leading to the Variations

5.1. Abiotic Factors

Nutrient supply is the most powerful driver of fast growth of marine macroalgae [

70]. Coastal eutrophication along the Jiangsu shoal, as indicated by the area-weighted nutrient pollution (AWCPI-NP) index, increased by 45% from 2007-2012 compared to that of 2001-2006. This rise was primarily driven by nutrient loading from river runoff, excessive agricultural fertilization, and intensive mariculture, which have been identified as critical factors contributing to green tides blooms [

10,

24,

71,

72]. The increased concentrations of nutrients species, particularly dissolved inorganic nitrogen (DIN), have favored the large extent and prolonged duration of green tides, thereby determining their seasonal pattern [

22,

72,

73,

74]. As documented by Li et al. [

75], the biomass of

Ulva prolifera shows a positive correlation with DIN concentrations (Spearman correlations, r = 0.84, P<0.001) from late March to April. Assuming the Sheyang river is a vital nutrients source for the Yellow Sea, Xiao et al. inferred the river might provide a key nutritional foundation supporting the outbreak of

Ulva prolifera [

13]. This conclusion was drawn from the significant positive correlation (r = 0.52, P < 0.01) between the annual maximum biomass of

Ulva prolifera and the total nutrient load from the Sheyang River. However, rather than river discharge factors, nutrient inputs from human activities contribute more significantly to the interannual variation of nutrients along the Jiangsu coast [

72,

76]. Therefore, the correlation found by Xiao et al. [

13] is insufficient to explain the interannual variation. To date, the role of nutrients in these interannual variation remains unclear due to the lack of longtime nutrient data [

23].

Temperature has a significant impact on

Ulva germination and vegetative growth [

77]. Under nutrient-rich conditions, temperature is the key abiotic factor that influences biomass accumulation and species succession during the initial phase [

27,

29,

78]. The initial biomass of

Ulva prolifera showed a strong correlation with SST in March from 2011 to 2016, whereas no significant correlation was found between climatological variables in April [

19]. From May to July, water temperature ranges from 15℃ to 25℃, creating suitable conditions for the growth of green macroalgal [

58], among which the growth rate of

Ulva prolifera was fastest when temperatures ranged from 17℃ to 22℃ [

66]. But, extreme high temperature, such as the prolonged heatwave (>30℃) that lasted for more than a month in 2017, greatly inhibited algal growth [

18] and slowed the expansion of the algal blooms [

63]. However, changes in SST in the Yellow Sea was not significantly correlated with the interannual variability of the floating

Ulva prolifera biomass [

23,

46].

Besides nutrients and temperature, several abiotic factors, such as salinity [

29,

79], light intensity [

80,

81] and pH [

73,

75], also influence the productivity of

Ulva prolifera. However, none of these factors alone can fully explain the spatial-temporal variability in the growth of

Ulva prolifera [

29].

Ulva prolifera exhibits a strong capacity to adapt to a wide range of environmental conditions [

11]. Therefore, the variation in

Ulva prolifera species may be influenced by a range of environmental factors acting in a complex and non-linear manner. Moreover, as reported by Jin et al. [

19], different abiotic factors played different roles during different growth phases of

Ulva prolifera. Thus, comprehensive and multi-disciplinary field studies are essential for understanding the annual variations.

5.2. The Rapid Expansion and Cultivation of Porphyra Mariculture in Jiangsu Province

Ulva prolifera in the Yellow Sea is believed to have originated from the raft frames used for Porphyra cultivation along the coast of Jiangsu Province [

13,

33,

82]. Annually, approximately 6500 tons of

Ulva prolifera detach from the Porphyra rafts, with 62% floating on the surface water, ultimately leading to the formation of massive green tide blooms [

16]. The Porphyra aquaculture area showed a sharp increase since 2007, with rapid expansion occurring in the Sansha regions on offshore tidal flats located approximately 30-60 km from the coastline. In these areas, attached

Ulva prolifera, once detached, can quickly drift into the Northern Yellow Sea [

20,

83]. Statistically, the maximum daily

Ulva prolifera shows a relatively high coefficient (r = 0.63) with the Porphyra cultivation area in the northern part of the Jiangsu Shoal [

20], indicating its significant role in the interannual variation of

Ulva prolifera.

In addition to the Porphyra cultivation area, Xing et al. suggested that the timing of Porphyra facility recycling [

20], which is related to early macroalgal biomass, may also be a key factor influencing the interannual biomass of

Ulva prolifera. Shao et al. [

84] documented that geographical features and farming patterns of Porphyra in Subei Shoal triggered the formation of massive floating

Ulva prolifera. However, without statistically meaningful evidence, the extent to which it contributes to interannual variation remains unclear.

5.3. Monsoons and Ocean Currents

The southeastward monsoons prevail in the Yellow Sea from May to July, driving the movement of surface ocean particles and thus facilitating the northward migration of green tides [

14,

85]. Thus, the interannual variation in the local monsoon wind field, which is controlled by or lags behind the climatological variation of atmospheric-oceanic system [

85], is one of the key factors influencing the migration direction and distribution patterns of green tides [

47]. In addition, the wind-induced Subei Coastal Current, residual tidal cycles, and tidal movements also influence the movement of green tides [

86]. Therefore, monsoons and wind-driven current systems help explain the interannual variation in the migration trajectories of macroalgae.

6. Concluding Remarks and Research Perspectives

Green tides have consecutively appeared every summer in the Yellow Sea for the past 16 years. Extensive studies have significantly enhanced our understanding of their spatiotemporal variations, the interannual variability in bloom size, and possible factors driving these fluctuations. However, many questions still remain unanswered.

1) There are still significant gaps in our understanding of the long-distance movement of Ulva prolifera. Satellites monitoring of macroalgal has identified new eastward drifts of green tides in 2008, 2009, 2011, 2015 and 2016. However, more detailed information on these eastward drifts, including their spatial-temporal dynamics, underlying causes, and migration mechanisms, remains unclear. Even for the more common northward movement, there is a lack of a reliable and effective quantitative method to clearly depict the interannual variations in this movement. Additionally, important knowledge gaps persist regarding the final landing and decomposition processes of Ulva prolifera.

2) The quantified

Ulva prolifera areal coverage and corresponding biomass estimates vary significantly. The macroalgae are typically distributed in patches of different sizes or in banded stripes with various shapes [

15,

25,

31]. As a result, the pattern of macroalgal distribution, and thus the estimated coverage area derived from images with different resolutions, can differ substantially. This raises the question: which data is reliable? A simultaneous field investigation may be necessary to explore a more reliable and universal method for estimating algae coverage or biomass. Moreover, there is an urgent need for robust automatic macroalgal detection systems that are less influenced by subjective factors. Furthermore, ongoing research into the spatial distribution of the thickness of floating

Ulva prolifera will enhance the accuracy of biomass estimates in the Yellow Sea.

3) The dynamic factors outlined above, and their interactions, are responsible for the interannual variability in bloom size, the sudden outbreak in 2007, and the sharp decline in 2017. However, while there is compelling evidence that seaweed aquaculture influences the scale of green tides, other mechanisms driving these variations need to be further explored to develop effective control strategies. Therefore, comprehensive, multidisciplinary field studies, laboratory research, and ecological modeling are essential for a deeper understanding of Ulva biology and physiology, in order to clarify the observed patterns.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization- writing-original draft preparation, F.Q. and F.W.; writing-review and editing, L.M.; visualization-funding acquisition, T.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (42406193) and Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province, China (ZR2023MD046; ZR2020QD092).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Smetacek, V.; Zingone, A. Green and golden seaweed tides on the rise. Nat. 2013, 504, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, N.; Zhang, X.; Mao, Y.; Liang, C.; Xu, D.; Zou, J.; Zhuang, Z.; Wang, Q. ‘Green tides’ are overwhelming the coastline of our blue planet: taking the world’s largest example. Ecol. Res. 2011, 26, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; He, M. Origin and Offshore Extent of Floating Algae in Olympic Sailing Area. Trans., Am. Geophys. Union. 2008, 89, 302–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Keesing, J.; Xing, Q.; Shi, P. World’s largest macroalgal bloom caused by expansion of seaweed aquaculture in China. Marine Pollution Bulletin. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2009, 58, 888–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Q.; Wu, L.; Tian, L.; Cui, T.; Li, L.; Kong, F.; Gao, X.; Wu, M. Remote sensing of early-stage green tide in the Yellow Sea for floating-macroalgae collecting campaign. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 133, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Liu, C.; Yang, G.; Zhang, H. The response of the carbonate system to a green algal bloom during the post-bloom period in the southern Yellow Sea. Cont. Shelf Res. 2015, 94, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Xing, Q.; Li, X.; Yu, D.; Zhang, J.; Zou, J. Assessment of the Impacts From the World’s Largest Floating Macroalgae Blooms on the Water Clarity at the West Yellow Sea Using MODIS Data (2002–2016). IEEE-J-STARS. 2018, 11, 1397–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhang, G.; Sun, X.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, X. Temporal variability in zooplankton community in the western Yellow Sea and its possible links to green tides. PeerJ. 2019, 7, e6641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Q.; Tosi, L.; Braga, F.; Gao, X.; Gao, M. Interpreting the progressive eutrophication behind the world’s largest macroalgal blooms with water quality and ocean color data. Nat. Hazard. 2015, 78, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; He, P.; Li, H.; Li, G.; Liu, J.; Jiao, F.; Zhang, J.; Huo, Y.; Shi, X.; Su, R.; et al. Ulva prolifera green-tide outbreaks and their environmental impact in the Yellow Sea, China. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2019, 6, 825–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Song, Y.; Liu, D.; Keesing, J.; Gong, J. Macroalgal blooms favor heterotrophic diazotrophic bacteria in nitrogen-rich and phosphorus-limited coastal surface waters in the Yellow Sea. Estuarine, Coastal Shelf Sci. 2015, 163, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Hu, C.; Ming-Xia, H.E. Remote estimation of biomass of Ulva prolifera macroalgae in the Yellow Sea. Remote Sens Environ. 2017, 192, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Cui, T.; Gong, J.; Liu, R.; Chen, X.; Liang, X. Remote sensing estimation of the biomass of floating Ulva prolifera and analysis of the main factors driving the interannual variability of the biomass in the Yellow Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 140, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Pang, I.; Moon, I.; Ryu, J. On physical factors that controlled the massive green tide occurrence along the southern coast of the Shandong Peninsula in 2008: A numerical study using a particle-tracking experiment. J. Geophys. Res.:Oceans. 2011, 116, C12036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, F.; Dai, D.; Simpson, J.; Svendsen, H. Banded structure of drifting macroalgae. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2009, 58, 1792–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xiao, J.; Fan, S.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, D. Who made the world’s largest green tide in China? —an integrated study on the initiation and early development of the green tide in Yellow Sea. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2015, 60, 1105–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Huang, J.; Ding, Y.; Liu, G.; Huang, S.; Gao, S.; Yuan, C.; Xu, J.; Wu, P.; Huang, R.; et al. Analysis on the causes of massive stranding of Yellow Sea green tide on Lianyungang and Rizhao coasts in 2022. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 2024, 42, 816–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Shin, J.; Kim, K.Y.; Ryu, J. Long-Term Trend of Green and Golden Tides in the Eastern Yellow Sea. J. Coastal Res. 2019, 90, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Liu, Y.; Sun, C.; Wei, X.; Li, H.; Han, Z. A study of the environmental factors influencing the growth phases of Ulva prolifera in the southern Yellow Sea, China. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 135, 1016–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Q.; An, D.; Zheng, X.; Wei, Z.; Wang, X.; Li, L.; Tian, L.; Chen, J. Monitoring seaweed aquaculture in the Yellow Sea with multiple sensors for managing the disaster of macroalgal blooms. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 231, 111279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Liu, D.; Anderson, D.; Valiela, I. Introduction to the Special Issue on green tides in the Yellow Sea. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2015, 163, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Keesing, J.; Dong, Z.; Zhen, Y.; Di, B.; Shi, Y.; Fearns, P.; Shi, P. Recurrence of the world’s largest green-tide in 2009 in Yellow Sea, China: Porphyra yezoensis aquaculture rafts confirmed as nursery for macroalgal blooms. Mar Pollut Bull. 2010, 60, 1423–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; Hu, C.; Xing, Q.; Shang, S. Long-term trend of Ulva prolifera blooms in the western Yellow Sea. Harmful Algae. 2016, 58, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Q.; Hu, C.; Tang, D.; Tian, L.; Tang, S.; Wang, X.; Lou, M.; Gao, X. World’s Largest Macroalgal Blooms Altered Phytoplankton Biomass in Summer in the Yellow Sea: Satellite Observations. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 12297–12313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, T.; Li, F.; Wei, Y.; Yang, X.; Xiao, Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, R.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, J. Super-resolution optical mapping of floating macroalgae from geostationary orbit. Appl. Opt. 2020, 59, C70–C77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, Y.; Han, H.; Shi, H.; Wu, H.; Zhang, J.; Yu, K.; Xu, R.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, K.; et al. Changes to the biomass and species composition of Ulva sp. on Porphyra aquaculture rafts, along the coastal radial sandbank of the Southern Yellow Sea. Mar Pollut Bull. 2015, 93, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, Y.; Han, H.; Hua, L.; Wei, Z.; Yu, K.; Shi, H.; Kim, J.K.; Yarish, C.; He, P. Tracing the origin of green macroalgal blooms based on the large scale spatio-temporal distribution of Ulva microscopic propagules and settled mature Ulva vegetative thalli in coastal regions of the Yellow Sea, China. Harmful Algae. 2016, 59, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keesing, J., Liu, D. Annually recurrent macroalgal blooms (Ulva prolifera) resulting in the world’s largest green-tides caused by expansion of coastal aquaculture in the Yellow Sea off China. European Geosciences Union General Assembly, 7-12 April 2013; Vienna, Austria, 2013; pp. 13419.

- Keesing, J.; Liu, D.; Shi, Y.; Wang, Y. Abiotic factors influencing biomass accumulation of green tide causing Ulva spp. on Pyropia culture rafts in the Yellow Sea, China. Mar Pollut Bull. 2016, 105, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, X.; Xiao, J.; Pang, M.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; Miao, J.; Li, Y.J.M.p. Effect of the large-scale green tide on the species succession of green macroalgal micro-propagules in the coastal waters of Qingdao, China. Mar Pollut Bull. 2017, 126, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, T.; Liang, X.; Gong, J.; Tong, C.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, R.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J. Assessing and refining the satellite-derived massive green macro-algal coverage in the Yellow Sea with high resolution images. ISPRS J. Photogramm. 2018, 144, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, T.; Zhang, J.; Sun, L.; Jia, Y.; Zhao, W.; Wang, Z.; Meng, J. Satellite monitoring of massive green macroalgae bloom (GMB): imaging ability comparison of multi-source data and drifting velocity estimation. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2012, 33, 5513–5527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Q.; Hu, C. Mapping macroalgal blooms in the Yellow Sea and East China Sea using HJ-1 and Landsat data: Application of a virtual baseline reflectance height technique. Remote Sens Environ. 2016, 178, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Zeng, K.; Hu, C.; He, M.-X. On the remote estimation of Ulva prolifera areal coverage and biomass. Remote Sens Environ. 2019, 223, 194–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, Y.; Min, J.; Ryu, J. Detecting massive green algae (Ulva prolifera) blooms in the Yellow Sea and East China Sea using Geostationary Ocean Color Imager (GOCI) data. Ocean Sci. J. 2012, 47, 359–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Wang, M. Green macroalgae blooms in the Yellow Sea during the spring and summer of 2008. J. Geophys. Res. 2009, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, R.; Fearns, P.; Keesing, J.; Liu, D. Quantification of floating macroalgae blooms using the scaled algae index. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans. 2013, 118, 26–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C. A novel ocean color index to detect floating algae in the global oceans. Remote Sens Environ. 2009, 113, 2118–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keesing, J.; Liu, D.; Fearns, P.; Garcia, R. Inter- and intra-annual patterns of Ulva prolifera green tides in the Yellow Sea during 2007–2009, their origin and relationship to the expansion of coastal seaweed aquaculture in China. Mar Pollut Bull. 2011, 62, 1169–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, Y.; Choi, B.; Kim, Y.; Park, Y. Tracing floating green algae blooms in the Yellow Sea and the East China Sea using GOCI satellite data and Lagrangian transport simulations. Remote Sens Environ. 2015, 156, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; Hu, C.; Barnes, B.B.; Lapointe, B.E.; Chen, Y.; Xie, Y.; Wang, M. Climate and Anthropogenic Controls of Seaweed Expansions in the East China Sea and Yellow Sea. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2022, 49, e2022GL098185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Q.; Liu, H.; Li, J.; Hou, Y.; Meng, M.; Liu, C. A Novel Approach of Monitoring Ulva pertusa Green Tide on the Basis of UAV and Deep Learning. Water. 2023, 15, 3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Zhou, M. Green Tides of the Yellow Sea: Massive Free-Floating Blooms of Ulva prolifera. In Global Ecology and Oceanography of Harmful Algal Blooms; Glibert, P.M., Berdalet, E., Burford, M.A., Pitcher, G.C., Zhou, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2018; pp. 317–326. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, X. A review of the green tides in the Yellow Sea, China. Mar. Environ. Res. 2016, 119, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, F.; Wang, G.; Lü, X.; Dai, D. Drift characteristics of green macroalgae in the Yellow Sea in 2008 and 2010. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2011, 56, 2236–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Zhang, H.; Ju, L.; Chen, M. Interannual variability of Ulva prolifera blooms in the Yellow Sea. Int J Remote Sens. 2014, 35, 4099–4113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Wu, Y.; Fang, Z.; Cui, X.; Liang, J.; Song, X. Spatiotemporal Patterns and Morphological Characteristics of Ulva prolifera Distribution in the Yellow Sea, China in 2016–2018. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; wu, M.; Sun, X.; Zhao, D.; Xing, Q.; Liang, F. The inter-annual drift and driven force of ulva prolifera bloom in the southern yellow sea. Oceanologia et Limnologia Sinica. 2018, 49, 1084–1093. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xu, F. The UAV and Multi-resource data-based research on green tide monitoring in the Yellow Sea. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China, 2018. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Choi, D.; Noh, J.; Ryu, J.; Lee, J.; Jang, P.; Lee, T.; Choi, D. Occurrence of Green Macroalgae (Ulva prolifera) Blooms in the Northern East China Sea in Summer 2008. Ocean Polar Res. 2010, 32, 351–359. (In Korean) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, S.; Oh, H.; Hwang, J.; Suh, Y.; Park, M.; Shin, J.; Kim, W.J.J.o.r.s. Tracking the Movement and Distribution of Green Tides on the Yellow Sea in 2015 Based on GOCI and Landsat Images. Korean Journal of Remote Sensing. 2017, 33, 97–109. (In Korean) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harun-Al-Rashid, A.; Yang, C. Hourly variation of green tide in the Yellow Sea during summer 2015 and 2016 using Geostationary Ocean Color Imager data. Int J Remote Sens. 2018, 39, 4402–4415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Su, R.; Zhou, F.; Zhang, C.; Shi, X. Extraction and identification of toxic organic substances from decaying green alga Ulva prolifera. Harmful Algae. 2020, 93, 101786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, H.; Yu, R.; Zhang, Q.; Yan, T.; Kong, F.; Zhou, M. Tracing the settlement region of massive floating green algae in the Yellow Sea. J. Ocean. Limnol. 2019, 37, 1555–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Liu, T.; Liu, C.Y.; Liang, S.; Hu, Y.; Jin, Y.; Wang, X.J.M.E.P.S. Effects of Ulva prolifera blooms on the carbonate system in the coastal waters of Qingdao. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2018, 605, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yu, R.; Zhou, M. Acute toxicity of live and decomposing green alga Ulva (Enteromorpha) prolifera to abalone Haliotis discus hannai. Chin. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 2011, 29, 541–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yu, R.; Zhou, M.-J. Effects of the decomposing green macroalga Ulva (Enteromorpha) prolifera on the growth of four red-tide species. Harmful Algae. 2012, 16, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Wu, M.; Zhao, J.; Luan, S.; Wang, D.; Jiang, W.; Xue, M.; Liu, J.; Cui, Y. Effects of Ulva prolifera dissipation on the offshore environment based on remote sensing images and field monitoring data. Acta Oceanol Sin. 2023, 42, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, D. The spatiotemporal variation research of Ulva prolifera blooms dissipation in the Southern Yellow Sea. Ph.D. Dissertation, (In Chinese). University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Gao, Z.; Xu, F. Research on the dissipation of green tide and its influencing factors in the Yellow Sea based on Google Earth Engine. Mar Pollut Bull. 2021, 172, 112801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; He, Y.; Niu, L.; Wu, M.; Kaufmann, H.; Liu, J.; Liu, T.; Kong, Q.; Chen, B. Identification of Green Tide Decomposition Regions in the Yellow Sea, China: Based on Time-Series Remote Sensing Data. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. The research of multi-scale observation and variation of green tide in the Yellow Sea based on multi-source satellite remote sensing images. Master’s Dissertation, . University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China, 2022. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Shi, J.; Gao, S.; Huo, Y.; Cui, J.; Shen, H.; Liu, G.; He, P. Annual patterns of macroalgal blooms in the Yellow Sea during 2007-2017. PLoS One. 2019, 14, e0210460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Yuen, K.-V.; Gu, X.; Sun, C.; Gao, L. Influences of environmental factors on the dissipation of green tides in the Yellow Sea, China. Mar Pollut Bull. 2023, 189, 114737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Natural Resources of the People’s Republic of China. 2023 Bulletin of China Marine Disaster. 2024.

- Zhan, Y.; Qiu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Su, Y.; Li, Y.; Cui, Y.; Qu, S.; Wang, P.; Rong, X. Long-Term Spatiotemporal Characteristics of Ulva prolifera Green Tide and Effects of Environmental Drivers on Its Monitoring by Satellites: A Case Study in the Yellow Sea, China, from 2008 to 2023. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Qi, L.; Hu, L.; Cui, T.; Xing, Q.; He, M.; Wang, N.; Xiao, Y.; Sun, D.; Lu, Y.; et al. Mapping Ulva prolifera green tides from space: A revisit on algorithm design and data products. Int J Appl Earth Obs Geoinf. 2023, 116, 103173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Wu, M.; Zhou, M.; Zhao, L. The seasonal dissipation of Ulva prolifera and its effects on environmental factors: based on remote sensing images and field monitoring data. Geocarto Int. 2022, 37, 860–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Lu, Y.; Hu, L.; Jiao, J.; Zhang, M.; Liu, Y. Uncertainty in the optical remote estimation of the biomass of Ulva prolifera macroalgae using MODIS imagery in the Yellow Sea. Opt. Express. 2019, 27, 18620–18627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merceron, M.; Morand, P. Existence of a deep subtidal stock of drifting Ulva in relation to intertidal algal mat developments. J. Sea Res. 2004, 52, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Tang, H.; Shi, X.; Zhang, C.; Wang, X. Increased nutrient loads from the Changjiang (Yangtze) River have led to increased Harmful Algal Blooms. Harmful Algae. 2014, 39, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, C.; Han, X.; Shi, X. Changes in concentrations of oxygen, dissolved nitrogen, phosphate, and silicate in the southern Yellow Sea, 1980–2012: Sources and seaward gradients. Estuarine, Coastal Shelf Sci. 2015, 163, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; Han, X.; Shi, X.; Rivkin, R.; Legendre, L. Growth responses of Ulva prolifera to inorganic and organic nutrients: Implications for macroalgal blooms in the southern Yellow Sea, China. Sci Rep. 2016, 6, 26498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Qi, M.; Tang, H.; Han, X. Spatial and temporal nutrient variations in the Yellow Sea and their effects on Ulva prolifera blooms. Estuarine, Coastal Shelf Sci. 2015, 163, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, H.; Shi, X.; Rivkin, R.B.; Legendre, L. Spatiotemporal variations of inorganic nutrients along the Jiangsu coast, China, and the occurrence of macroalgal blooms (green tides) in the southern Yellow Sea. Harmful Algae. 2017, 63, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yu, Z.; Fu, Y.; Dong, M.; Zhang, J.; Yao, Q. Seasonal and interannual variations of nutrients in the Subei Shoal and their implication for the world’s largest green tide. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 951, 175390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodhead, P.; Moss, B.L.J.E.J.o.P. The effects of light and temperature on settlement and germination of Enteromorpha. Br. phycol. J. 1975, 10, 269–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Peng, K.; Xiao, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, X.; Fu, M.; Fan, S.; Zhu, M.; Li, R. Effects of temperature on the germination of green algae micro-propagules in coastal waters of the Subei Shoal, China. Estuarine, Coastal Shelf Sci. 2015, 163, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Fu, M.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Song, W.; Li, Y.; Liu, G.; Shi, X.; Wang, X.; Zhu, M. Temporal variation of green macroalgal assemblage on Porphyra aquaculture rafts in the Subei Shoal, China. Estuarine, Coastal Shelf Sci. 2015, 163, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Zhang, J.; Huo, Y.; Zhou, L.; Wu, Q.; Chen, L.; Yu, K.; He, P. Adaptability of free-floating green tide algae in the Yellow Sea to variable temperature and light intensity. Mar Pollut Bull. 2015, 101, 660–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, S.; Liu, C.; Zhang, L.; Ji, X.; Song, W.; Xu, R.; He, P. An adjustment mechanism to high light intensity for free-floating Ulva in the Yellow Sea. Journal of Shanghai Ocean University. 2016, 25, 97–105. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D.; Keesing, J.K.; He, P.; Wang, Z.; Shi, Y.; Wang, Y. The world’s largest macroalgal bloom in the Yellow Sea, China: Formation and implications. Estuarine, Coastal Shelf Sci. 2013, 129, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhao, P.; Huo, Y.; Yu, K.; He, P. The fast expansion of Pyropia aquaculture in “Sansha” regions should be mainly responsible for the Ulva blooms in Yellow Sea. Estuarine, Coastal Shelf Sci. 2017, 189, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, K.; Gong, N.; Shen, L.; Han, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, K.; Kong, D.; Pan, X.; Cong, P. Why did the world’s largest green tides occur exclusively in the southern Yellow Sea? Mar. Environ. Res. 2024, 200, 106671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.; Liu, Y.; Hou, Y.; Yin, Y. An early forecasting method for the drift path of green tides: A case study in the Yellow Sea, China. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. 2018, 71, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, M.; Guan, W.; Yang, Y.; Cao, Z.; Chen, Q. Drifting trajectories of green algae in the western Yellow Sea during the spring and summer of 2012. Estuarine, Coastal Shelf Sci. 2015, 163, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).