Submitted:

10 April 2025

Posted:

11 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Aspects

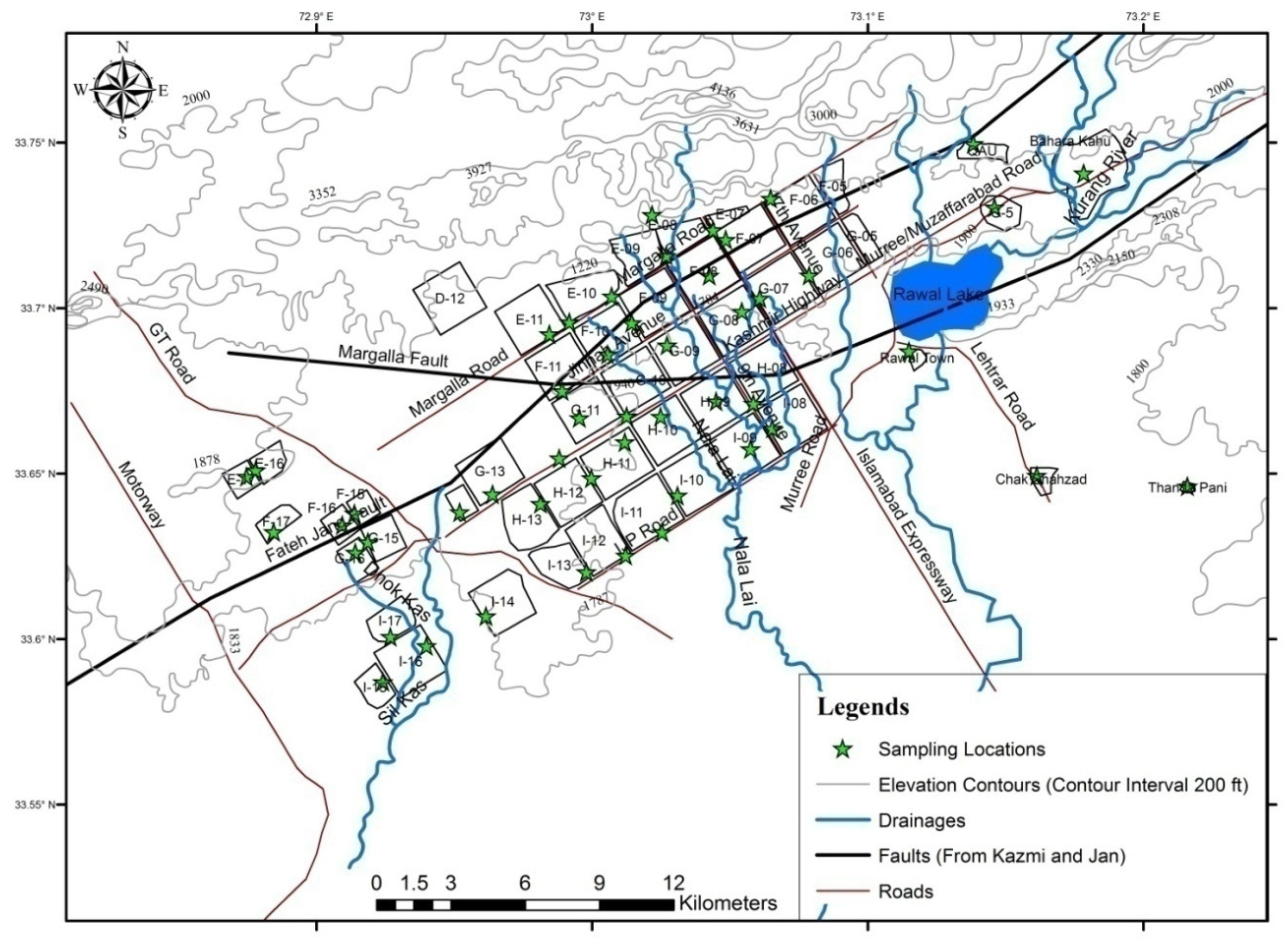

2.1.1. Area of Study

2.1.2. Sample Collection and Measurement

2.2. Mathematical Aspects

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgement

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals |

| TLA | Three letter acronym |

| LD | Linear dichroism |

References

- Manjón, G.; Mantero, J.; Vioque, I.; Díaz-Francés, I.; Galván, J.A.; Chakiri, S.; Choukri, A.; García-Tenorio, R. Natural radionuclides (NORM) in a Moroccan river affected by former conventional metal mining activities. Journal of Sustainable Mining 2019, 18, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeez, H.H.; Mansour, H.H.; Ahmad, S.T. Effect of Using Chemical Fertilizers on Natural Radioactivity Levels in Agricultural Soil in the Iraqi Kurdistan Region. Polish Journal of Environmental Studies 2020, 29, 1059–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullahi, S.; Ismail, A.F.; Samat, S. Determination of indoor doses and excess lifetime cancer risks caused by building materials containing natural radionuclides in Malaysia. Nuclear Engineering and Technology 2019, 51, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Elkader, M.M.; Shinonaga, T.; Sherif, M.M. Radiological hazard assessments of radionuclides in building materials, soils and sands from the Gaza Strip and the north of Sinai Peninsula. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 23251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menshikova, E.; Perevoshchikov, R.; Belkin, P.; Blinov, S. Concentrations of Natural Radionuclides (40K, 226Ra, 232Th) at the Potash Salts Deposit. Journal of Ecological Engineering 2021, 22, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewtubtim, P.; Meeinkuirt, W.; Seepom, S.; Pichtel, J. Radionuclide (226Ra, 232Th, 40K) accumulation among plant species in mangrove ecosystems of Pattani Bay, Thailand. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2017, 115, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Gamal, H.; Hussien, M.T.; Saleh, E.E. Evaluation of natural radioactivity levels in soil and various foodstuffs from Delta Abyan, Yemen. Journal of Radiation Research and Applied Sciences 2019, 12, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deliberations of the United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation at its sixty-seventh session; United Nations, 2000.

- Tzortzis, M.; Tsertos, H. Determination of thorium, uranium and potassium elemental concentrations in surface soils in Cyprus. Journal of Environmental Radioactivity 2004, 77, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myhre, L.G.; Kessler, W.V. Body density and potassium 40 measurements of body composition as related to age. Journal of Applied Physiology 1966, 21, 1251–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avlonitou, E.; Georgiou, E.; Douskas, G.; Louizi, A. Estimation of body composition in competitive swimmers by means of three different techniques. Int. J. Sports Med. 1997, 18, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, K.; Fukushi, M.; Van Le, T.; Tsuruoka, H.; Kasahara, S.; Nimelan, V. Distribution of gamma radiation dose rate related with natural radionuclides in all of Vietnam and radiological risk assessment of the built-up environment. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 12428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aközcan, S.; Külahcı, F.; Günay, O.; Özden, S. Radiological risk from activity concentrations of natural radionuclides: Cumulative Hazard Index. Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry 2021, 327, 105–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanovska, Z.; Boev, B. Risk assessment resulting from radionuclides in soils of the Republic of Macedonia. Prilozi - Makedonska Akademija na Naukite i Umetnostite Oddelenie za Prirodno-Matematichki i Biotehnichki Nauki 2019, 40, 161–168. [Google Scholar]

- Devi, V.; Chauhan, R.P. Estimation of natural radionuclide and exhalation rates of environmental radioactive pollutants from the soil of northern India. Nuclear Engineering and Technology 2020, 52, 1289–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakovlev, E.Y.; Zykova, E.N.; Zykov, S.B.; Malkov, A.V.; Bazhenov, A.V. Heavy metals and radionuclides distribution and environmental risk assessment in soils of the Severodvinsk industrial district, NW Russia. Environmental Earth Sciences 2020, 79, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazaroff, W.W.; Nero, A.J. Radon and its decay products in indoor air; John Wiley and Sons, Incorporated: United States, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Elío, J.; Cinelli, G.; Bossew, P.; Gutiérrez-Villanueva, J.L.; Tollefsen, T.; De Cort, M.; Nogarotto, A.; Braga, R. The first version of the Pan-European Indoor Radon Map. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 2019, 19, 2451–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, G.S. Gastric cancer in New Mexico counties with significant deposits of uranium. Arch Environ Health 1985, 40, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjellberg, S.; Wiseman, J.S. The relationship of radon to gastrointestinal malignancies. Am Surg 1995, 61, 822–825. [Google Scholar]

- ; Number 295 in Technical Reports Series, INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY: Vienna, 1989.

- Ibikunle, S.B.; Arogunjo, A.M.; Ajayi, O.S. Characterization of radiation dose and soil-to-plant transfer factor of natural radionuclides in some cities from south-western Nigeria and its effect on man. Scientific African 2019, 3, e00062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPA 1999 National primary drinking water regulations, radon-222 federal register US; Vol. 64, Environmental Protection Agency, 1999; pp. 59245–59294.

- on the Effects of Atomic Radiation, U.N.S.C. Sources and Effects of Ionizing Radiation, United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR) 1993 Report; United Nations, 1993.

- Qureshi, A.A.; Tariq, S.; Din, K.U.; Manzoor, S.; Calligaris, C.; Waheed, A. Evaluation of excessive lifetime cancer risk due to natural radioactivity in the rivers sediments of Northern Pakistan. Journal of Radiation Research and Applied Sciences 2014, 7, 438–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzubaidi, G.; Hamid, F.B.S.; Abdul Rahman, I. Assessment of Natural Radioactivity Levels and Radiation Hazards in Agricultural and Virgin Soil in the State of Kedah, North of Malaysia. ScientificWorldJournal 2016, 2016, 6178103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- on the Effects of Atomic Radiation, U.N.S.C. Sources and Effects of Ionizing Radiation, United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR) 2020/2021 Report; United Nations, 2021.

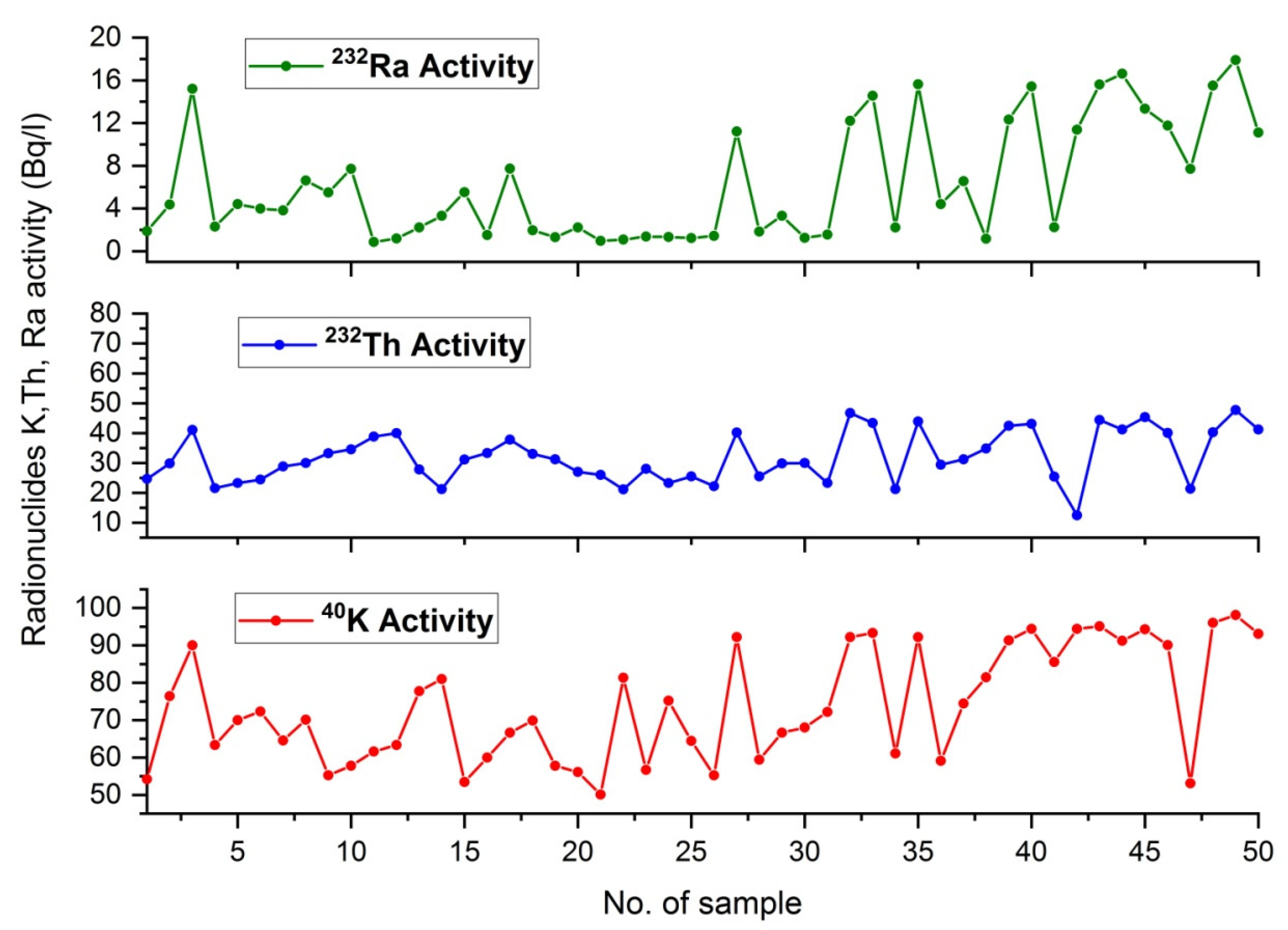

| No. of sample | Sample location | 226Ra () | 232Th () | 40K () | Raeq () | Din () | |

| 1 | QAU | 1.88 | 24.65 | 54.21 | 41.26 | 33.18 | |

| 2 | NLR | 4.36 | 29.9 | 76.44 | 52.95 | 43.02 | |

| 3 | RWD | 15.21 | 41.11 | 90.03 | 80.86 | 66.42 | |

| 4 | E-7 | 2.31 | 21.56 | 63.33 | 37.98 | 30.91 | |

| 5 | E-9 | 4.41 | 23.33 | 69.99 | 43.12 | 35.32 | |

| 6 | CSD | 3.98 | 24.44 | 72.33 | 44.46 | 36.33 | |

| 7 | E-8 | 3.82 | 28.88 | 64.56 | 50.04 | 40.45 | |

| 8 | BKH | 6.61 | 29.99 | 70.09 | 54.84 | 44.68 | |

| 9 | E-9 | 5.51 | 33.3 | 55.23 | 57.33 | 46.12 | |

| 10 | G-16 | 7.71 | 34.56 | 57.77 | 61.53 | 49.73 | |

| 11 | E-16 | 0.87 | 38.88 | 61.61 | 61.15 | 48.5 | |

| 12 | E-17 | 1.19 | 39.99 | 63.33 | 63.19 | 50.15 | |

| 13 | E-10 | 2.21 | 27.88 | 77.77 | 48.02 | 38.92 | |

| 14 | E-12 | 3.31 | 21.23 | 80.99 | 39.87 | 32.88 | |

| 15 | I-13 | 5.53 | 31.21 | 53.46 | 54.23 | 43.7 | |

| 16 | I-11 | 1.52 | 33.33 | 59.99 | 53.75 | 42.86 | |

| 17 | I-14 | 7.72 | 37.87 | 66.66 | 66.95 | 54.09 | |

| 18 | I-8 | 1.96 | 33.09 | 69.87 | 54.61 | 43.79 | |

| 19 | I-17 | 1.31 | 31.23 | 57.77 | 50.37 | 40.18 | |

| 20 | I-9 | 2.21 | 27.04 | 56.09 | 45.15 | 36.26 | |

| 21 | I-15 | 0.96 | 26.05 | 50.09 | 42.03 | 33.55 | |

| 22 | I-10 | 1.08 | 21.11 | 81.33 | 37.49 | 30.72 | |

| 23 | I-16 | 1.36 | 28.08 | 56.66 | 45.83 | 36.67 | |

| 24 | I-12 | 1.33 | 23.33 | 75.22 | 40.44 | 32.9 | |

| 25 | G-5 | 1.22 | 25.54 | 64.44 | 42.66 | 34.37 | |

| 26 | G-6 | 1.44 | 22.22 | 55.23 | 37.43 | 30.19 | |

| 27 | G-10 | 11.21 | 40.2 | 92.21 | 75.73 | 61.91 | |

| 28 | G-7 | 1.83 | 25.55 | 59.4 | 42.9 | 34.54 | |

| 29 | G-14 | 3.32 | 29.87 | 66.66 | 51.12 | 41.24 | |

| 30 | G-12 | 1.25 | 30 | 68.03 | 49.34 | 39.59 | |

| 31 | G-15 | 1.56 | 23.3 | 72.22 | 40.4 | 32.84 | |

| 32 | G-11 | 12.21 | 46.76 | 92.22 | 86.1 | 70.05 | |

| 33 | G-13 | 14.56 | 43.44 | 93.33 | 83.8 | 68.65 | |

| 34 | G-8 | 2.21 | 21.22 | 61.11 | 37.23 | 30.26 | |

| 35 | G-9 | 15.63 | 43.89 | 92.22 | 85.42 | 70.04 | |

| 36 | H-12 | 4.41 | 29.44 | 59.11 | 51.01 | 41.17 | |

| 37 | H-11 | 6.55 | 31.23 | 74.44 | 56.89 | 46.33 | |

| 38 | H-10 | 1.16 | 34.87 | 81.44 | 57.24 | 45.94 | |

| 39 | H-8 | 12.32 | 42.44 | 91.32 | 79.97 | 65.32 | |

| 40 | H-9 | 15.43 | 43.14 | 94.44 | 84.32 | 69.2 | |

| 41 | H-13 | 2.24 | 25.44 | 85.58 | 45.17 | 36.89 | |

| 42 | F-8 | 11.37 | 12.44 | 94.44 | 36.41 | 31.7 | |

| 43 | F-9 | 15.61 | 44.41 | 95.12 | 86.37 | 70.82 | |

| 44 | F-10 | 16.61 | 41.23 | 91.22 | 82.53 | 67.93 | |

| 45 | F-15 | 13.33 | 45.33 | 94.31 | 85.34 | 69.67 | |

| 46 | F-16 | 11.76 | 40.11 | 90.09 | 75.99 | 62.15 | |

| 47 | F-17 | 7.71 | 21.33 | 53.11 | 42.27 | 34.81 | |

| 48 | F-6 | 15.51 | 40.33 | 96.01 | 80.51 | 66.31 | |

| 49 | F-11 | 17.89 | 47.74 | 98.09 | 93.64 | 76.82 | |

| 50 | F-7 | 11.11 | 41.22 | 93.07 | 77.15 | 63.01 |

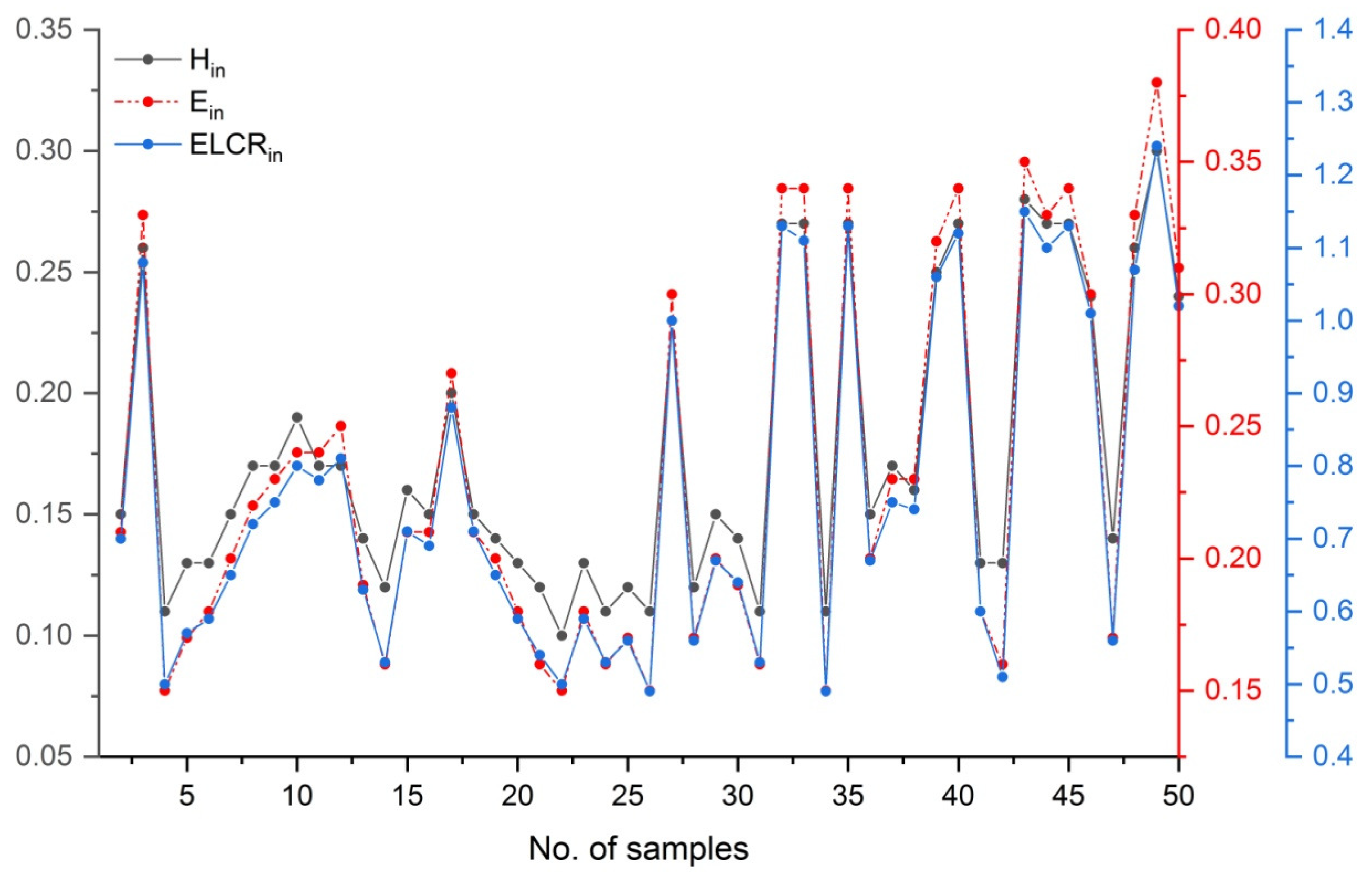

| No. of sample | Sample Name | Hin | Ein (mSv) | ELCRin ×10-3 |

| 1 | QAU | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.54 |

| 2 | NLR | 0.15 | 0.21 | 0.7 |

| 3 | RWD | 0.26 | 0.33 | 1.08 |

| 4 | E-7 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.5 |

| 5 | E-9 | 0.13 | 0.17 | 0.57 |

| 6 | CSD | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.59 |

| 7 | E-8 | 0.15 | 0.2 | 0.65 |

| 8 | BKH | 0.17 | 0.22 | 0.72 |

| 9 | E-9 | 0.17 | 0.23 | 0.75 |

| 10 | G-16 | 0.19 | 0.24 | 0.8 |

| 11 | E-16 | 0.17 | 0.24 | 0.78 |

| 12 | E-17 | 0.17 | 0.25 | 0.81 |

| 13 | E-10 | 0.14 | 0.19 | 0.63 |

| 14 | E-12 | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.53 |

| 15 | I-13 | 0.16 | 0.21 | 0.71 |

| 16 | I-11 | 0.15 | 0.21 | 0.69 |

| 17 | I-14 | 0.2 | 0.27 | 0.88 |

| 18 | I-8 | 0.15 | 0.21 | 0.71 |

| 19 | I-17 | 0.14 | 0.2 | 0.65 |

| 20 | I-9 | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.59 |

| 21 | I-15 | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.54 |

| 22 | I-10 | 0.1 | 0.15 | 0.5 |

| 23 | I-16 | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.59 |

| 24 | I-12 | 0.11 | 0.16 | 0.53 |

| 25 | G-5 | 0.12 | 0.17 | 0.56 |

| 26 | G-6 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.49 |

| 27 | G-10 | 0.23 | 0.3 | 1 |

| 28 | G-7 | 0.12 | 0.17 | 0.56 |

| 29 | G-14 | 0.15 | 0.2 | 0.67 |

| 30 | G-12 | 0.14 | 0.19 | 0.64 |

| 31 | G-15 | 0.11 | 0.16 | 0.53 |

| 32 | G-11 | 0.27 | 0.34 | 1.13 |

| 33 | G-13 | 0.27 | 0.34 | 1.11 |

| 34 | G-8 | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.49 |

| 35 | G-9 | 0.27 | 0.34 | 1.13 |

| 36 | H-12 | 0.15 | 0.2 | 0.67 |

| 37 | H-11 | 0.17 | 0.23 | 0.75 |

| 38 | H-10 | 0.16 | 0.23 | 0.74 |

| 39 | H-8 | 0.25 | 0.32 | 1.06 |

| 40 | H-9 | 0.27 | 0.34 | 1.12 |

| 41 | H-13 | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.6 |

| 42 | F-8 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.51 |

| 43 | F-9 | 0.28 | 0.35 | 1.15 |

| 44 | F-10 | 0.27 | 0.33 | 1.1 |

| 45 | F-15 | 0.27 | 0.34 | 1.13 |

| 46 | F-16 | 0.24 | 0.3 | 1.01 |

| 47 | F-17 | 0.14 | 0.17 | 0.56 |

| 48 | F-6 | 0.26 | 0.33 | 1.07 |

| 49 | F-11 | 0.3 | 0.38 | 1.24 |

| 50 | F-7 | 0.24 | 0.31 | 1.02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).