Introduction

Forests occupy significant portion of urban landscape, serving as a critical component of urban ecosystems [

1]. They can mitigate urban heat island effects, improve air quality, and provide essential environmental and ecosystem services [

2]. Tree parameters such as tree height (TH), diameter at breast height (DBH), crown diameter (CD), crown width, and above-ground biomass effectively reflect the growth conditions, spatial distribution, and structural features of urban forest resources [

3]. They also serve as important indicators for measuring the carbon sequestration capacity of urban forests and assessing urban ecological functions [

4].

The traditional method for obtaining tree parameters in forest stands involves manual measurements, such as using calipers or diameter tapes to measure the DBH and hypsometers to measure TH, followed by recording and organizing the results. Many researchers consider this method as time-consuming and labor-intensive [

5,

6,

7], particularly for large-scale surveys (e.g., urban forest parks). Additionally, the measurement results are prone to being influenced by human subjective factors [

6]. For instance, in a study of 319 trees in the Evo area of southern Finland, four trained surveyors independently measured the DBH and TH using calipers and clinometers. However, differences in the way the surveyors used the calipers resulted in variations in the measurement results [

8]. 3D reconstruction technology can convert forest scenes into 3D digital models and obtain tree properties from these models using automated procedures instead of manual measurements to improve work efficiency and reduce bias [

9]. In addition, tree models constructed from 3D point clouds can be used for the planning and management of green infrastructure in the development of smart cities [

10].

Terrestrial Laser Scanner (TLS) has been used to obtain high-density 3D point cloud models of forest scenes, from which parameters such as TH and DBH can be derived for individual trees [

11,

12,

13]. Meanwhile, tree structural parameters derived from TLS have been proven to be highly reliable. Reddy

, et al. [

14] validated the DBH and TH estimates automatically derived by TLS in deciduous forests. Compared to field measurements, the DBH had an

R² = 0.96 and

RMSE = 4.1 cm, while the height estimate had an

R² = 0.98 and

RMSE = 1.65 m. Due to the high measurement accuracy of TLS, it can also be used as a benchmark for other remote sensing methods instead of field survey data [

15,

16]. However, because of the limited scanning angles of TLS and occlusion effects, it is challenging to capture complete canopy information for taller parts of trees. Therefore, airborne laser scanners are commonly used to collect canopy point cloud data. Jaskierniak

, et al. [

17] utilized an Airborne Laser Scanning (ALS) system to acquire point cloud data of structurally complex mixed forests and performed individual tree detection and canopy delineation. Liao

, et al. [

18] investigated the role of ALS data in improving the accuracy of tree volume estimation. Their study demonstrated that TH extracted from ALS data are more accurate than those measured manually with a telescoping pole. Combining ALS data with on-site DBH measurements effectively improves the accuracy of tree volume estimates. Although TLS and ALS can acquire large-area point cloud data in a short period, these devices are expensive and require high levels of technical expertise to operate [

19]. Additionally, in many countries flight permits are required for uncrewed aerial vehicle (UAV) operators to carry out drone flights.

With the advancement of image processing algorithms, camera sensors and hardware, close-range photogrammetry (CRP) is now considered as a cost-effective alternative to laser scanning in 3D reconstruction. CRP method has demonstrated significant potential in urban forest survey works [

20,

21,

22] as 3D point cloud can be reconstructed from overlapping images. This allows for the acquisition of 3D model information of trees using only forest scene imagery which is easily available. Compared to TLS and ALS, CRP significantly reduces costs and operational complexity. The current mainstream photogrammetry method is Structure from Motion (SfM) [

23]

+ Multi-view Stereo (MVS) [

24], which involves feature detection, feature matching, and depth fusion between image pairs. SfM uses matching constraints and triangulation principles to obtain 3D sparse point and camera parameters, while MVS densifies the point cloud. Kameyama and Sugiura [

25] used UAV to capture forest images under different conditions, employed the SfM method to create 3D models, and validated the measurement accuracy of tree height and volume. Bayati, et al. [

26] used hand-held digital cameras and SfM-MVS to produce a 3D reconstruction of uneven-aged deciduous forests and successfully extracted individual tree DBH. A high coefficient of the determinant (

R2 = 98%) was observed between DBH derived from field measurements and that from the SfM-MVS technique. Xu

, et al. [

27] compared the accuracy of forest structure parameters extracted from SfM and Backpack LiDAR Scanning (BLS) point clouds. Their results showed that SfM point cloud models are well-suited for extracting DBH, but there is still a gap in the accuracy of TH extraction. This discrepancy depends on the quality of the point cloud model, which is influenced not only by the robustness of the algorithm but also by the quality of the acquired images and feature matching. In complex forest environments, there are often occlusions and varying lighting conditions between trees, which affect the quality of image data. Furthermore, similar shape and texture patterns between trees pose challenges for feature matching. To improve the quality of forest scene images, Zhu

, et al. [

28] compared three image enhancement algorithms and concluded that the Multi-Scale Retinex algorithm is more suitable for 3D reconstruction of forest scenes. Although these enhancements can improve the quality of forest scene reconstruction to some extent, there are still discrepancies in data accuracy compared to that of obtained from TLS, and there remains significant room for improvement in terms of time efficiency.

Recently, Novel View Synthesis (NVS) technology has become an active research topic in computer vision. Mildenhall

, et al. [

29] first introduced a deep learning-based rendering method called Neural Radiance Fields (NeRF). NeRF implicitly renders complex static scenes in 3D using a fully connected network. Since then NeRF have drawn the attention of many researchers, leading to various improvements [

30–32]. Müller, et al. [

30] introduced a hash mapping technique to enhance the sampling point positional encoding method, effectively accelerating network training. In terms of reconstruction accuracy, Barron, et al. [

31] used conical frustums instead of ray sampling to address aliasing issues at different distances. Wang, et al. [

32] replaced the Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) with Signed Distance Functions (SDF) for geometric representation, achieving high-precision geometric reconstruction. These improvements have pushed research on NeRF into practical applications, providing high-quality 3D rendering perspectives for fields like autonomous driving [

33] and 3D city modeling [

34]. NeRF is not only capable of synthesizing novel view images but can also be used to reconstruct 3D models. Currently reported applications in 3D reconstruction include cultural heritage [

35] and plants and trees. In the context of plant 3D reconstruction and phenotypic research, Hu

, et al. [

36] evaluated the application of NeRF in the 3D reconstruction of low-growing plants. The results demonstrated that NeRF introduces a new paradigm in plant phenotypic analysis, providing a powerful tool for 3D reconstruction. Zhang

, et al. [

37] proposed the NeRF-Ag model, which realized the 3D reconstruction of orchard scenes and effectively improved the modeling accuracy and efficiency. Huang

, et al. [

38] evaluated NeRF's ability to generate dense point clouds for individual trees of varying complexity, providing a novel example for NeRF-based single tree reconstruction. Nevertheless, NeRF still faces challenges in achieving high-resolution real-time rendering and efficient dynamic scene editing. 3D Gaussian Splatting (3DGS) [

39] brought a technological breakthrough to the field. Unlike NeRF, 3DGS utilizes an explicit Gaussian point representation to precisely capture and present information about 3D scenes. In terms of optimization and rendering speed, 3DGS significantly outperforms the original NeRF method [

40], advancing NVS technology to a new level. The results of the 3DGS algorithm were compared with the state-of-the-art Mip-NeRF360 method and performed better on standard metrics [

41]. 3DGS technology has become a transformative force driving innovations in related fields with notable achievements in areas such as novel view rendering [

42] and dynamic scene reconstruction [

43]. However, the application of 3DGS to plants and forest scenes reconstruction and generation of dense point cloud models of tree have not yet been fully explored and evaluated.

Compared to individual trees, forest stands consisting of multiple trees exhibit substantial self-occlusion and increasing complexity, posing greater challenges for image acquisition and 3D reconstruction. Research on the application of NVS technology in this area remains scarce, lacking a complete reconstruction workflow and detailed evaluation results. Therefore, this study applies NeRF and 3DGS technologies to the 3D reconstruction of trees in urban forest stands to obtain dense 3D point cloud models. The generated point cloud models are then compared and evaluated against photogrammetric methods using TLS point cloud as reference. The specific research objectives are as follows:

(1) Comparing the practical application of NVS techniques and photogrammetric reconstruction methods in complex urban forest stands;

(2) Evaluating the ability of different NVS methods (one based on implicit neural networks: NeRF;another on explicit Gaussian point clouds: 3DGS) in reconstructing trees and generating dense point clouds;

(3) Comparing tree parameters extracted from various 3D point cloud models and assessing whether NVS techniques can replace or supplement photogrammetric methods, potentially becoming a new tool for forest scene reconstruction and forest resource surveys.

4. Discussion

In this study, we applied three image-based 3D reconstruction techniques in forest stands, including a photogrammetry pipeline (SfM+MVS in COLMAP) and novel view synthesis-based methods (NeRF and 3DGS). By comparing the dense point cloud models generated by these three methods with the reference TLS point clouds, we analyzed the reconstruction efficiency and point cloud model quality of different methods for reconstructing forest stands.

The difficulty in successfully reconstructing multi-view 3D models of forest stands typically lies in the fact that trees of the same species have similar texture structures, making it challenging for algorithms to distinguish (detect and match) tree features. Additionally, due to the occlusion of tree branches and canopies, the views could change dramatically even between two adjacent images. The first step for photogrammetry, NeRF, and 3DGS is to obtain accurate camera poses and calibrated images through SfM. If the results of SfM are inaccurate, it will affect the subsequent dense reconstruction outcomes, for example, duplicated (phantom) trunks can appear at the same location with a small offset. In the COLMAP pipeline, the steps of SfM include feature extraction, feature matching, and triangulation of points. During our SfM experiments, we found that the results of feature matching are related to the completeness of the camera pose estimation. By default, COLMAP uses Exhaustive matching (where all images are matched pairwise). Using this method for matching the images of Plot_1_UAV and Plot_2_UAV, SfM was only able to successfully solve for the poses of 173 images (out of total input of 268 images) and 268 images (input of 322 images), respectively, along with generating a sparse point cloud for parts of the scene. However, COLMAP also supports other matching methods, such as spatial matching (which requires images to have positional information, such as GPS data). Considering that the UAV images of Plot_1 and Plot_2 contain positioning information, using spatial matching allows for the successful retrieval of the complete camera pose information for all input images (Plot_1_UAV: 268 images, Plot_2_UAV: 322 images) and a more complete feature point cloud. The results of downstream dense reconstruction (MVS, NVS) depend to large extent on the accuracy of the upstream SfM results, which is why spatially matched SfM results are used during the dense reconstruction phase. To reduce dependence on SfM, some studies have utilized optical flow and point trajectory principles for camera pose estimation [

46]. Others have integrated the camera pose estimation step into the 3DGS network training framework, simultaneously optimizing both 3DGS and camera poses [

47]. Additionally, the scene regression-based ACE0 [

48] method and the general-purpose global SfM method GLOMAP [

49] significantly improve operational efficiency and achieve SfM estimates comparable to COLMAP. More robust feature matching methods, such as LoFTR [

50] and RCM [

51], can also replace the feature matching step in SfM to improve matching accuracy.

MVS utilizes the corresponding images and camera parameters obtained from sparse reconstruction to reconstruct a dense point cloud model through multi-view stereopsis. This process involves calculating depth information for each image and fusing depth maps. Typically, the time required to compute depth information occupies the majority of the MVS dense reconstruction time. Moreover, the time consumption increases with the size, complexity of the scene, and the number of images. In previous study on single tree reconstruction, the MVS dense reconstruction of a single tree (with 107-237 input images) usually took 50 to 100 minutes on a single 3090 GPU [

38]. However, in this study, despite using the more computationally efficient 4090 GPU, the reconstruction of forest plot scenes (with 268-322 input images) still took 450 to 700 minutes. The average processing time per input image increases from 0.43-0.83 minutes to 1.40-2.70 minutes, an approximate increase of about 3.3 times. But the COLMAP processing time for Plot_2_UAV (more images and higher total resolution) was shorter than that for Plot_1_UAV. This may be because the scene in Plot_1 was relatively simpler and had clearer textures, which led to a larger number of detectable feature points, thereby increasing the time required for reconstruction. The efficiency of reconstruction is influenced by multiple factors, and further experiments and analysis are needed to better understand these effects. In contrast, efficient deep learning networks like NeRF and 3DGS can significantly reduce the reconstruction time, usually completing within 20 minutes, and the time required appears to be independent of the scene size and the number of images.

By comparing the number of points, overall view and detailed vertical profiles of the point cloud tree models, we highlight the advantages and disadvantages of the three image-based reconstruction methods. The COLMAP method can generate models with the highest number of points, but it tends to introduce more noise in the trunk and canopy layers. Comparing the COLMAP models of Plot_1_Phone and Plot_1_UAV, the UAV provides more image data for the canopy, which reduces noise in the UAV_COLMAP model's canopy region. However, a significant amount of noise remains. In contrast, the NeRF model exhibits less noise in the canopy. When there is ground occlusion or limited viewpoints, such as in the case of Plot_1_Phone, the NeRF model exhibits missing or erroneous reconstructions in the ground regions. The 3DGS model contains the fewest points, with fewer than 2 million points overall, resulting in a sparse and low-quality point cloud model that fails to represent real-world accurately. This indicates that the ability of 3DGS to generate dense point cloud models is inferior to that of COLMAP and NeRF. In the more complex scene of Plot_2, NeRF can produce point cloud models closest to those obtained from Lidar, compared to COLMAP and 3DGS models. NeRF reconstructs colored and more detailed trunks, and captures more complete canopies. This advantage may be attributed to NeRF's differentiable implicit volumetric representation, which optimizes camera poses through backpropagated loss gradients. This approach significantly reduces pose estimation errors even with imperfect input data, thereby enhancing scene clarity and detail representation to achieve high-quality reconstruction. Meanwhile, the COLMAP model occasionally shows intersecting trunks or multiple overlapping trees. These observations demonstrate that NeRF is better suited to handling complex forest stand, but requires complete viewing angle coverage during data acquisition..

When selecting plots and collecting data, different types of plots and data acquisition methods were chosen with the aim of comparing and illustrating how these factors might affect the results. We selected two plots with different tree species and canopy morphologies: Plot_1 consisted of leafless trees with simple branch structures and less occlusion between trees, resulting in more complete tree point cloud models reconstructed by all three methods. In contrast, Plot_2 has dense foliage and more occlusions, which led to incomplete tree trunks and missing canopies in the middle of the plot. However, compared to the other two methods, NeRF was better able to handle occluded scenes, producing tree point cloud models with more detailed trunk structures and more complete canopies. For Plot_1, image data were collected using both a smartphone (capturing lower-resolution images from the ground only) and a UAV (capturing higher-resolution images from both ground and aerial perspectives). The UAV images, which provided more viewpoints, resulted in more complete tree point cloud models with fewer noise points in the canopy. Furthermore, models generated from higher-resolution images contained more detailed tree features. The quality of the models also significantly impacted the accuracy of subsequent individual tree structure parameter extraction. For example, the tree crown diameter extracted by the UAV model in Plot_1 is more accurate than that by the phone, with R² increasing by 0.041–0.081 and RMSE decreasing by 0.06 m–0.35 m.

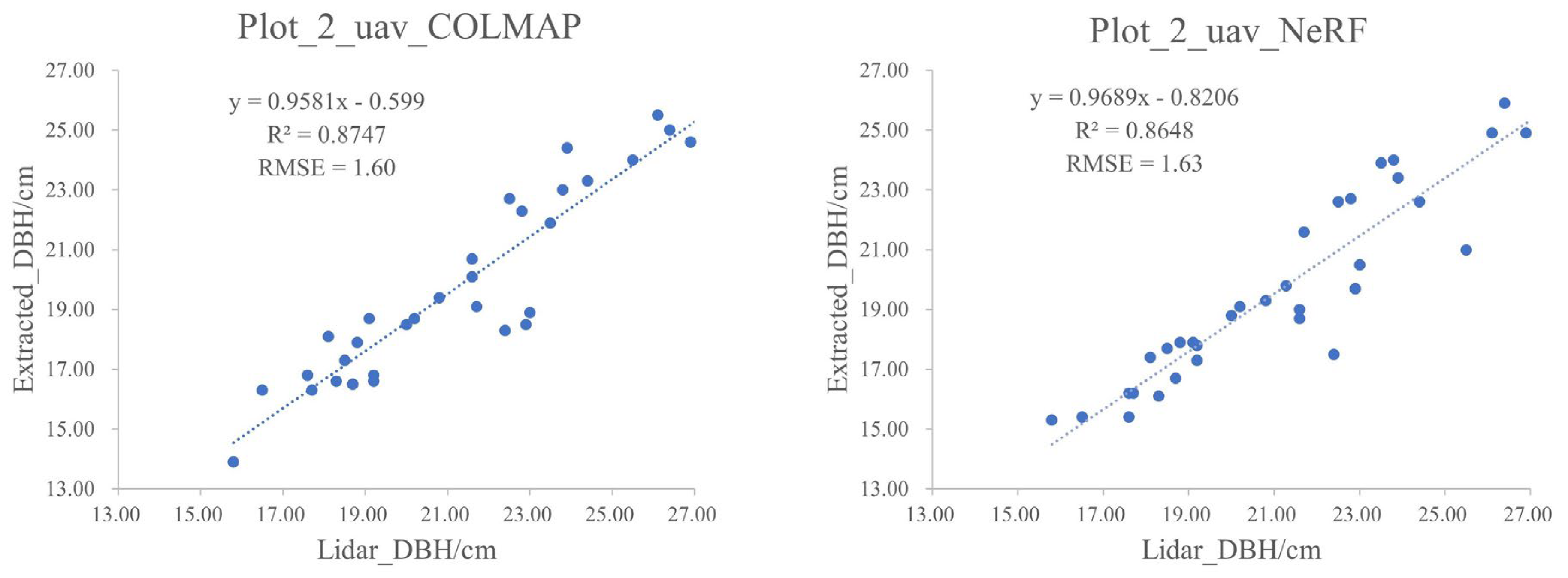

We performed individual tree segmentation on different point cloud models and extracted TH, DBH and CD as individual tree structural parameters for comparison. During the individual tree segmentation process, the number of trees in the Plot_2_COLMAP model exceeded the actual count. This could be attributed to the high similarity in texture features and partial occlusion among trees in this plot, which reduces the number of feature points and results in mismatches, causing a single tree to be represented by multiple duplicated models. Therefore, the conventional photogrammetry algorithm (SfM+MVS) sometimes is unable to handle more complex forest plot scenes. In terms of TH parameters, all three methods achieve high accuracy in terms of RMSE and R2, with estimates from the NeRF model generally outperforming those from the COLMAP and 3DGS models. In terms of DBH estimation, the models generated from lower-resolution smartphone images show poorer accuracy, while the models reconstructed from higher-resolution UAV images demonstrate higher precision. Among them, the COLMAP model provides better DBH estimates; however, in the extracted individual COLMAP tree models, some phantom tree trunks often intersect each other, which may cause the estimated DBH values to be larger than the actual ones. The NeRF method has slightly lower estimation accuracy compared to the photogrammetry approach and tends to underestimate the DBH values. The 3DGS method yields the least accurate DBH estimates, as its reconstructed points are relatively sparse and trunk points tend to clustering together, leading to DBH estimates that are significantly lower than the reference Lidar DBH values. In terms of the crown width parameter, for the simple canopies in Plot_1, all three methods achieve relatively accurate crown diameters, with UAV models showing higher R² values than Phone models, indicating that images collected by drones result in more complete tree canopies during reconstruction. Compared to Plot_1, the denser canopy in Plot_2 shows that COLMAP and NeRF produce denser canopy point clouds, while 3DGS has sparser canopies and lower R² values for crown diameter. The above results indicate that photogrammetry can provide more accurate DBH estimations in relatively simple forest plots, though it yields lower-quality tree point clouds. In contrast, NeRF achieves higher-quality point cloud reconstructions,thus more accurate estimations of TH and CD. These findings also demonstrate that higher-resolution and more comprehensive UAV imagery can enhance the quality of reconstructed tree point clouds and improve the accuracy of structural parameter extraction.

We acknowledge that this research is limited in scope, as the current study was conducted in only two small plots with homogeneous tree species and limited terrain variation. However, our findings suggest that NeRF holds greater potential than photogrammetry for applications in complex forest environments. Therefore, future studies will expand the scope to include larger and more complex forest plots. Additionally, when extending this approach to other forest scenarios, attention should be paid to the resolution of the collected images, and careful planning of data acquisition routes is necessary to ensure complete image coverage of the study area.

Through this study, we have gained a deeper understanding of the practical applications of NeRF and 3DGS methods in forest scenes and the properties of the dense point cloud data generated by these methods, provided answers to the questions raised in the introduction earlier. At the same time, we outline prospects for future research: how to improve the accuracy of sparse point clouds and camera pose parameters obtained from upstream SfM, potentially by using more robust feature matching techniques and alternative SfM solutions, and by enhancing feature matching success rates through image enhancement methods; how to enhance the ability of NeRF and 3DGS to generate dense point clouds. Equipping NVS technology into lightweight devices (such as smartphones and drones) through dedicated applications to achieve real-time, online 3D tree reconstruction and structural parameter acquisition is also one of our goals. We expect the emergence of more powerful software tools and carefully designed strategies that will enable efficient and highly accurate 3D reconstruction of forest scenes, providing convenience for urban tree management.

Figure 1.

The structures and shapes of two plots used in this study. Upper panel: (a, b) Plot_1 with leafless trees as observed from two views from mid-air; Lower panel: (c, d) Plot_2 with leafy trees viewed from mid-air and from overhead position.

Figure 1.

The structures and shapes of two plots used in this study. Upper panel: (a, b) Plot_1 with leafless trees as observed from two views from mid-air; Lower panel: (c, d) Plot_2 with leafy trees viewed from mid-air and from overhead position.

Figure 2.

Overview of 3D Gaussian Splatting workflow (from [

39]).

Figure 2.

Overview of 3D Gaussian Splatting workflow (from [

39]).

Figure 3.

Camera positions obtained using COLMAP for two plots. For each plot, the left shows an aerial top-down view, while the right shows the scene from a ground-level perspective. From top panel to bottom, the camera positions of Plot_1 images captured by a smartphone camera and a camera on UAV are shown in red and yellow, respectively. The camera positions of images captured by the UAV in Plot_2 are displayed in blue.

Figure 3.

Camera positions obtained using COLMAP for two plots. For each plot, the left shows an aerial top-down view, while the right shows the scene from a ground-level perspective. From top panel to bottom, the camera positions of Plot_1 images captured by a smartphone camera and a camera on UAV are shown in red and yellow, respectively. The camera positions of images captured by the UAV in Plot_2 are displayed in blue.

Figure 4.

Complete workflow of this study. Data Acquisition involves taking sequential images from various angles using different cameras, as well as laser scanning to obtain reference point cloud; during 3D reconstruction images were processed with SfM in COLMAP to obtain camera poses and sparse point clouds, which were further fed into three separate reconstruction methods: photogrammetry (COLMAP), NeRF, and 3DGS to generate dense points. Finally, these dense point clouds are registered and compared with reference point cloud obtained from TLS for a comprehensive evaluation of the point cloud models.

Figure 4.

Complete workflow of this study. Data Acquisition involves taking sequential images from various angles using different cameras, as well as laser scanning to obtain reference point cloud; during 3D reconstruction images were processed with SfM in COLMAP to obtain camera poses and sparse point clouds, which were further fed into three separate reconstruction methods: photogrammetry (COLMAP), NeRF, and 3DGS to generate dense points. Finally, these dense point clouds are registered and compared with reference point cloud obtained from TLS for a comprehensive evaluation of the point cloud models.

Figure 5.

Overall comparison of the reconstruction results for Plot_1 presented from two opposing viewing angles. TLS Lidar point cloud with intensity values displayed in red and green for trunks and branches, respectively; COLMAP and NeRF models with color in RGB; 3DGS model with color in green.

Figure 5.

Overall comparison of the reconstruction results for Plot_1 presented from two opposing viewing angles. TLS Lidar point cloud with intensity values displayed in red and green for trunks and branches, respectively; COLMAP and NeRF models with color in RGB; 3DGS model with color in green.

Figure 6.

Detailed comparison of the reconstruction results from Plot_1_Phone. This includes single tree models extracted from the forest point clouds of Lidar (TLS), COLMAP, NeRF, and 3DGS, as well as their vertical point distributions and the trunk cross-section profile at a height of 1.3 meters.

Figure 6.

Detailed comparison of the reconstruction results from Plot_1_Phone. This includes single tree models extracted from the forest point clouds of Lidar (TLS), COLMAP, NeRF, and 3DGS, as well as their vertical point distributions and the trunk cross-section profile at a height of 1.3 meters.

Figure 7.

Detailed comparison of Plot_1_UAV reconstruction results. This includes single tree models extracted from the forest point clouds of Lidar (TLS), COLMAP, NeRF, and 3DGS, as well as their vertical point distributions and the trunk cross-section profile at a height of 1.3 meters.

Figure 7.

Detailed comparison of Plot_1_UAV reconstruction results. This includes single tree models extracted from the forest point clouds of Lidar (TLS), COLMAP, NeRF, and 3DGS, as well as their vertical point distributions and the trunk cross-section profile at a height of 1.3 meters.

Figure 8.

Overall comparison of the reconstruction results for Plot_2 viewing from two perspectives. TLS Lidar point cloud with intensity values displayed in red for trunks and branches and green for leaves; COLMAP and NeRF models with color in RGB; 3DGS model with color in green.

Figure 8.

Overall comparison of the reconstruction results for Plot_2 viewing from two perspectives. TLS Lidar point cloud with intensity values displayed in red for trunks and branches and green for leaves; COLMAP and NeRF models with color in RGB; 3DGS model with color in green.

Figure 9.

Detailed comparison of the reconstruction results in Plot_2. This includes single tree models extracted from the forest point clouds of Lidar (TLS), COLMAP, NeRF, and 3DGS, their vertical point distributions, and the top-down view of the forest plot model.

Figure 9.

Detailed comparison of the reconstruction results in Plot_2. This includes single tree models extracted from the forest point clouds of Lidar (TLS), COLMAP, NeRF, and 3DGS, their vertical point distributions, and the top-down view of the forest plot model.

Figure 10.

Linear fitting results of tree height (TH) extracted from Plot_1_Phone and Plot_1_UAV models compared to those derived from Lidar (TLS) reference values.

Figure 10.

Linear fitting results of tree height (TH) extracted from Plot_1_Phone and Plot_1_UAV models compared to those derived from Lidar (TLS) reference values.

Figure 11.

Linear fitting results of DBH extracted from Plot_1_Phone and Plot_1_UAV models compared to those derived from Lidar (TLS) reference values.

Figure 11.

Linear fitting results of DBH extracted from Plot_1_Phone and Plot_1_UAV models compared to those derived from Lidar (TLS) reference values.

Figure 12.

Linear fitting results of crown diameter (CD) extracted from the Plot_1_Phone and Plot_1_UAV models compared with those derived from Lidar (TLS) reference values.

Figure 12.

Linear fitting results of crown diameter (CD) extracted from the Plot_1_Phone and Plot_1_UAV models compared with those derived from Lidar (TLS) reference values.

Figure 13.

Linear fitting results of tree height (TH) and crown diameter (CD) extracted from Plot_2_UAV model compared to those derived from Lidar (TLS) reference values.

Figure 13.

Linear fitting results of tree height (TH) and crown diameter (CD) extracted from Plot_2_UAV model compared to those derived from Lidar (TLS) reference values.

Figure 14.

Linear fitting results of DBH extracted from the Plot_2_UAV model compared with those derived from Lidar (TLS) reference values.

Figure 14.

Linear fitting results of DBH extracted from the Plot_2_UAV model compared with those derived from Lidar (TLS) reference values.

Table 1.

Image data information for two forest stand plots.

Table 1.

Image data information for two forest stand plots.

| Image Dataset |

Number of Images |

Image Resolution |

| Plot_1_Phone |

279 |

3840×2160 |

| Plot_1_UAV |

268 |

5472×3648 |

| Plot_2_UAV |

322 |

5472×3648 |

Table 2.

Computation time (minutes) of dense reconstruction for different image datasets and dense reconstruction methods.

Table 2.

Computation time (minutes) of dense reconstruction for different image datasets and dense reconstruction methods.

| |

Plot_1_Phone |

Plot_1_UAV |

Plot_2_UAV |

| COLMAP |

544.292 |

724.495 |

453.834 |

| NeRF |

15.0 |

14.0 |

12.0 |

| 3DGS |

18.23 |

17.39 |

17.46 |

Table 3.

Number of points in the tree point cloud models.

Table 3.

Number of points in the tree point cloud models.

| Plot ID |

Model ID |

Number of Point |

| Plot_1 |

Plot_1_Lidar |

25,617,648 |

| Plot_1_Phone_COLMAP |

20,200,476 |

| Plot_1_Phone_NeRF |

4,548,307 |

| Plot_1_Phone_3DGS |

1,555,984 |

| Plot_1_UAV_COLMAP |

53,153,623 |

| Plot_1_UAV_NeRF |

2,573,330 |

| Plot_1_UAV_3DGS |

806,149 |

| Plot_2 |

Plot_2_Lidar |

9,053,897 |

| Plot_2_UAV_COLMAP |

55,861,268 |

| Plot_2_UAV_NeRF |

5,465,952 |

| Plot_2_UAV_3DGS |

831,164 |