Submitted:

11 April 2025

Posted:

14 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Problem Definition

2.2. Adaptation to Research Conditions

2.3. Delimitation of the Study Area as an Operational Context

2.4. Definition of the Operability Variable

2.5. Analysis of the Operability of Marine POETs

3. Results

3.1. Subsection Problem Definition

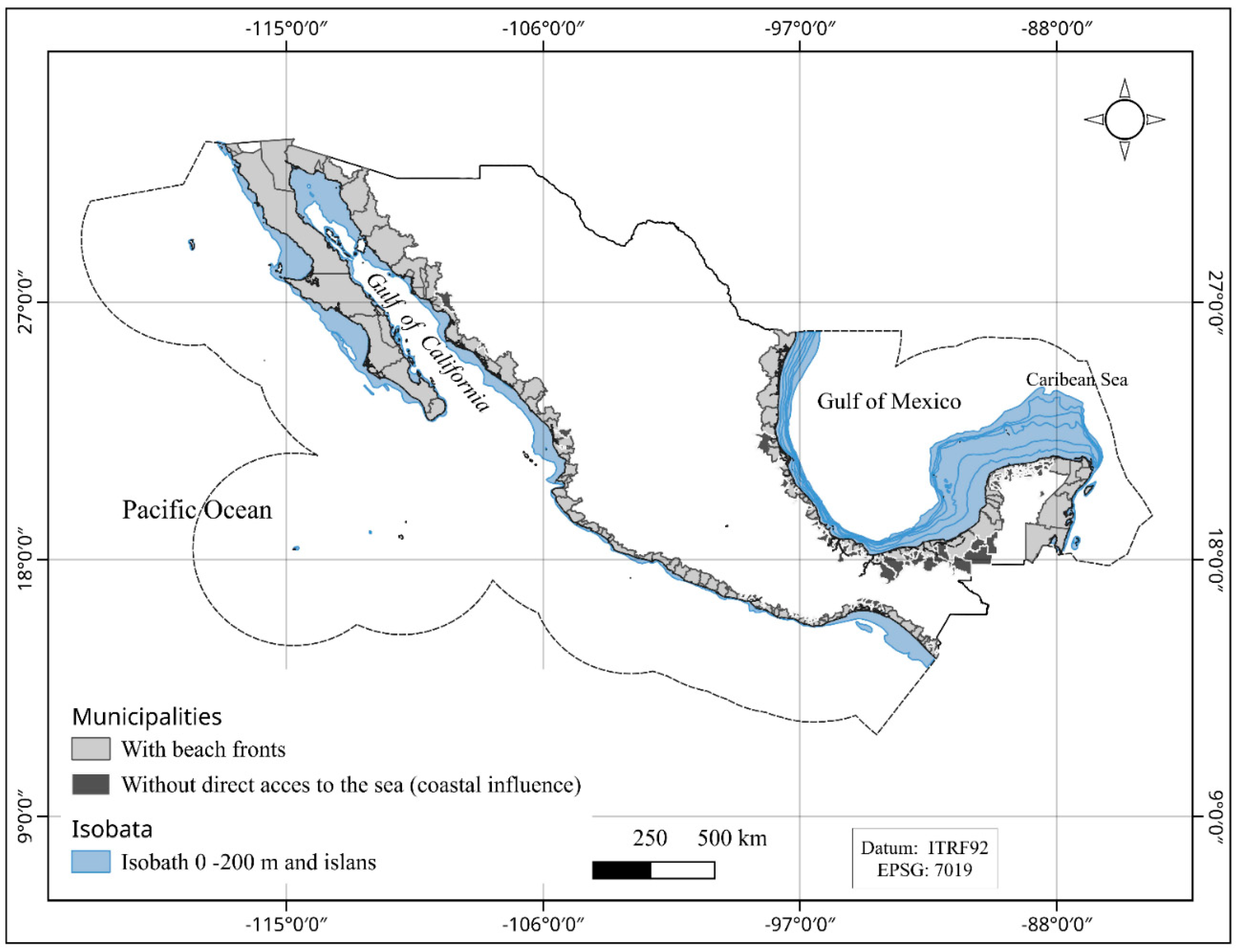

3.2. The Mexican Coastal Zone Context as Operative Condition

3.3. Operability as an Analytical Category

3.4. Analysis of Operational Conditions of Marine POETs in the MCZ

3.4.1 Operational Essential Conditions

3.4.2. Demographic Dimensions

| Coastal states | Municipality | Coastal population | |||

| State | Coastal | % | 2020 | ||

| 1 | Baja California | 7 | 6 | 86 | 3769020 |

| 2 | Baja California Sur | 5 | 5 | 100 | 798447 |

| 3 | Sonora | 72 | 14 | 19 | 2109304 |

| 4 | Sinaloa | 20 | 10 | 50 | 2661190 |

| 5 | Nayarit | 20 | 8 | 40 | 538565 |

| 6 | Jalisco | 125 | 5 | 4 | 936089 |

| 7 | Colima | 10 | 3 | 30 | 334962 |

| 8 | Michoacán | 113 | 3 | 3 | 237701 |

| 9 | Guerrero | 85 | 16 | 19 | 1358340 |

| 10 | Oaxaca | 570 | 41 | 7 | 836833 |

| 11 | Chiapas | 124 | 12 | 10 | 790905 |

| 12 | Tamaulipas | 43 | 7 | 16 | 1419067 |

| 13 | Veracruz | 212 | 56 | 26 | 3404748 |

| 14 | Tabasco | 17 | 13 | 76 | 2195916 |

| 15 | Campeche | 13 | 9 | 69 | 839212 |

| 16 | Yucatán | 106 | 51 | 48 | 1737093 |

| 17 | Quintana Roo | 11 | 7 | 64 | 1703424 |

| Total | 1553 | 266 | 17 | 25670816 | |

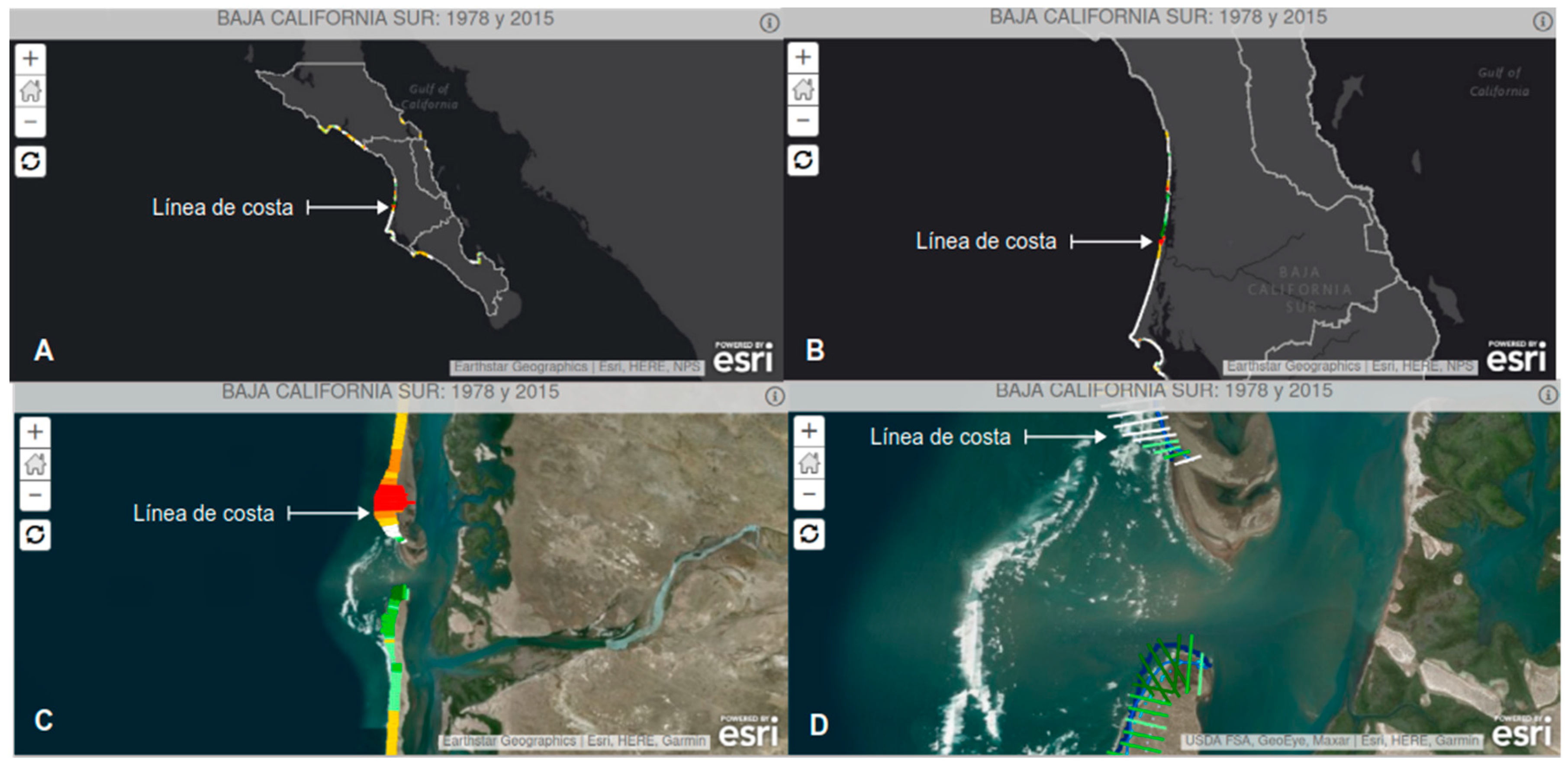

3.4.2. Coastline Dimensions

| Source | Estimation method | Lenght |

| Central Intelligence Agency de EEUU (CIA) [41] | Non identified | 9 330 km |

| National Institute of Statistics and Geography (in Spanish Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografia (INEGI)) [42] | Topographical charts scale 1:250 000 | 11 122 km |

| National Commision for Biodiversity Knowledge and Use (in Spanish Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad de México (CONABIO) [43] | RapidEye satellite imagery, processing level 3A, 5m spatial resolution, scale 1:25,000. * | 15 069 km* |

| Ortiz-Pérez y De la Lanza-Espino (2006) [44] | Topographical charts scale 1:50 000 | 24 945 km |

3.4.3 Nearshore Dimensions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MCZ | Mexican Coastal Zone |

| ETM | Ecological Territory Management |

| LGEEPA | General Law on Ecological Balance and Environmental Protection (acronym in Spanish) |

| POET | Ecological Territory Management Programs (POET, from the Spanish acronym) |

| MCZ | Mexican Coastal Zone |

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization |

| UGA | Environmental Management Units (acronym in Spanish) |

References

- Ley General del Equilibrio Ecológico y Protección al Ambiente § Capítulo IV § Sección II Diario Oficial de la Federación (DOF) 01-04-2024 [General Law on Ecological Balance and Environmental Protection § Chapter IV § Section II (1988-2024) Official Gazette of the Federation (DOF) 01-04-2024]. Available online: https://www.diputados.gob.mx/LeyesBiblio/pdf/LGEEPA.pdf Acessed 26 January 2025.

- Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos § Artículo 4 [Political Constitution of the United Mexican States § Article 4]. Current text Last reform published Diario Oficial de la Federación 17-01-2025, Mexico City, México. Available online: https://www.diputados.gob.mx/LeyesBiblio/pdf/CPEUM.pdf Acessed 23 January 2025.

- UNESCO-COI/Comisión Europea. Guía internacional de MSPglobal sobre planificación espacial marina/Marítima [MSPglobal International Guide to Marine Spatial Planning/Maritime]V. 2021. París, UNESCO. (Manuales y guías de la COI no 89) Available online: https://www.mspglobal2030.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/MSPglobal_InternationalGuideMSP_ES_HighRes.pdf Accessed 26 January 2025.

- California State Governor’s Office of Planning and Research. General Plan Guides State of California. 2017. Available online: https://lci.ca.gov/docs/OPR_COMPLETE_7.31.17.pdf Accessed 26 January de 2025.

- Milanés-Batista C.; Pereira, C. I. y Botero, C. M. Improving a decree law about coastal zone management in a small island developing state: The case of Cuba. Marine Policy. 2019, 101, 93-107. [CrossRef]

- UNESCO-IOC. 2021. MSPglobal Policy Brief: Ocean Governance and Marine Spatial Planning. Paris, UNESCO. (IOC Policy Brief no 5. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000375723 Accessed 28 January de 2025.

- Carmona-Lara, M. del C. Criterios Normativos para el Ordenamiento Ecológico [Regulatory Criteria for Ecological Planning] Boletín Mexicano de Derecho Comparado. 1993, 78, 819-846. [CrossRef]

- Escofet, A. Marco operativo de macro y mesoescala para estudios de planeación de zona costera en el Pacífico Mexicano [Macro and mesoscale operational framework for coastal zone planning studies in the Mexican Pacific]. In. Rivera A, Evelia, Guillermo.J. Villalobos, Isaac Azuz A. y Francisco Rosado M. (Editores). El manejo costero en México. 2004. Universidad Autónoma de Campeche. Available http://etzna.uacam.mx/epomex/pdf/mancos/cap15.pdf Accessed 12 December 2024.

- Instituto Nacional de Ecología (INE) - Secretaría de Medio Ambiente Recursos Naturales (SEMARNAT). Términos de Referencia Etapas de caracterización y diagnóstico del estudio técnico para el Programa de Ordenamiento Ecológico Marino y Regional del Pacífico Norte [Characterization and diagnostic stages of the technical study for the North Pacific Marine and Regional Ecological Management Program]. Instituto Nacional de Ecología Dirección General de Investigación de Ordenamiento Ecológico y Conservación de Ecosistemas Subsecretaría de Planeación y Política Ambiental. Dirección General de Política Ambiental e Integración Regional y Sectorial. SEMARNAT. 2009. Available online: https://www.semarnat.gob.mx/archivosanteriores/temas/ordenamientoecologico/Documents/documentos%20pacifico%20norte/zip/tdr_poemrpn_anexo_oficio_bcs.pdf Accessed 15 December 2019.

- Gómez Orea, D. I. Marco Conceptual de la Ordenación Territorial [Conceptual Framework for Territorial Planning]. In Ordenación territorial. Madrid: Ediciones Mundi-Prensa/ Editorial Agrícola Española. 2001.

- Palacio-Prieto J. L.; Sánchez-Salazar M. T.; Casado-Izquierdo, J. M.: Propin-Frejomil, E.; Delgado-Campos, J.; Velázquez-Montes, A.; Chias-Becerril, L.; Ortiz-Álvarez, M. I.; González-Sánchez, J.; Negrete-Fernández, G.; Gabriel-Morales: Márquez-Huitzil, J.: Nieda-Manzano, R., T.; Jiménez-Rosenberg, R.; Muñoz-López, E.; Ocaña-Nava, D.; Juárez-Aguirre, E.; Anzaldo-Gómez, C.; Hernández-Esquivel, J. C.; Valderrama-Campos, K.; Rodríguez-Carranza, J.; Campos-Campuzano, J. M.; Vera-Llamas-Cruz H. and Camacho Ramírez, C. G. Indicadores para la Caracterización y el Ordenamiento Territorial [Indicators for Characterization and Territorial Planning]. Secretaría de Desarrollo Social, Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales Instituto Nacional de Ecología Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. 2004. Available online: http://www.publicaciones.igg.unam.mx/index.php/ig/catalog/download/161/149/818-1?inline=1 Accessed 28 December 2019.

- H. Cámara de Diputados LX Legislatura Comité del Centro de Estudios de Las Finanzas Públicas Centro de Estudios de Las Finanzas Públicas. Plan Nacional de Desarrollo 2007-20012 Escenarios Programas e Indicadores [National Development Plan 2007-2012 Scenarios, Programs and Indicators.]. México. 2007. Available online: https://cefp.gob.mx/intr/edocumentos/pdf/cefp/cefp0962007.pdf Accessed 28 March 2025.

- Gobierno de La República Plan Nacional de Desarrollo 2013-2018 [National Development Plan 2013-2018]. México, 2013. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/32349/plan-nacional-de-desarrollo-2013-2018.pdf Accessed 26 March 2025.

- Gobierno de La República Plan Nacional de Desarrollo 2019-2024 [National Development Plan 2019-2024]. México, 2019. Available online: https://framework-gb.cdn.gob.mx/landing/documentos/PND.pdf Accessed 7 March 2025.

- Angeles-Hernández, M., Rovalo-Otero, M. and Tejado-Gallegos, M. Manual de Derecho Ambiental Mexicano [Mexican Environmental Law Manual] Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México Instituto de Investigaciones Jurídicas. México, 2021. Avaliable online: https://salazarvirtual.sistemaeducativosalazar.mx/assets/biblioteca/ab466cb7a086de51e200aa5ead0118e7-MANUAL%20DEL%20DERECHO%20AMBIENTAL%20MEXICANO_.pdf Accessed 12 January 2025.

- Espinoza-Tenorio, A.; Moreno-Báez, M.; Pech, D.; Villalobos-Zapata, G. J.; Vidal-Hernández, L.; Ramos-Miranda, J. Manuel Mendoza-Carranza, José Alberto Zepeda-Domínguez, Graciela Alcalá-Moya, Juan Carlos Pérez-Jiménez, Fernando Rosete, Cuauhtémoc León, Ileana Espejel. El ordenamiento ecológico marino en México: un reto y una invitación al quehacer científico [Marine ecological management in Mexico: a challenge and an invitation to scientific work]. Latin american journal of aquatic research. 2017, 42, 3, 386-400. Available online: doi:10.3856/vol42-issue3-fulltext-1 Accessed 28 March 2025.

- Reglamento de la Ley General del Equilibrio Ecológico y la Protección al Ambiente en Materia de Ordenamiento Ecológico § Capítulo Quinto [Regulations of the General Law on Ecological Balance and Environmental Protection in the Area of Ecological Planning] § Chapter Five]. Official Gazette of the Federation DOF 31-10-2014. Avaliable online: https://www.diputados.gob.mx/LeyesBiblio/regley/Reg_LGEEPA_MEIA_311014.pdf Accessed 15 January 2025.

- Reglamento para el Uso y Aprovechamiento del Mar Territorial, Vías Navegables, Playas, Zona Federal Marítimo Terrestre y Terrenos Ganados al Mar]. Official Gazette of the Federation DOF 21-08-1991. Available online: https://sidof.segob.gob.mx/notas/4739967 Accesed 01 February 2025.

- Acuerdo por el que se expide el Programa de Ordenamiento Ecológico Marino del Golfo de California [Agreement issuing the Marine Ecological Management Program of the Gulf of California]. Official Gazette of the Federation DOF 15-12-2006. Available online: https://dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=4940652&fecha=15/12/2006#gsc.tab=0 Accesed 28 March 2025.

- Acuerdo por el que se expide la parte marina del Programa de Ordenamiento Ecológico Marino y Regional del Golfo de México y Mar Caribe y se da a conocer la parte regional del propio Programa [Agreement issuing the marine part of the Marine and Regional Ecological Management Program for the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea and announcing the regional part of the Program itself]. Diario Oficial de la Federación DOF 24-11-12. Available online: https://www.diputados.gob.mx/LeyesBiblio/dof/2012/nov/DOF_24nov12.pdf Accesed 28 March 2025.

- Acuerdo por el que se da a conocer el Programa de Ordenamiento Ecológico Marino y Regional del Pacífico Norte [Agreement announcing the North Pacific Marine and Regional Ecological Management Program]. Official Gazette of the Federation DOF 09-08-18. Available online: https://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5534289&fecha=09/08/2018#gsc.tab=0 Accesed 28 March 2025.

- Acuerdo mediante el cual se expide la Política Nacional de Mares y Costas de México [Agreement by which the National Policy of Seas and Coasts of Mexico is issued.]. Official Gazette of the Federation DOF 30-11-18. Available online: https://dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5545511&fecha=30/11/2018#gsc.tab=0 Accesed 28 March 2025.

- Sánchez-Salazar, M.T., Bocco-Verdinelli, G. and Casado-Izquierdo J. M. La política de ordenamiento territorial en México: de la teoría a la práctica. Reflexiones sobre sus avances y retos a futuro [Land use policy in Mexico: from theory to practice. Reflections on progress and future challenges.]. 2013, 19-43. Avaliable online: https://publicaciones.geografia.unam.mx/index.php/ig Accessed March 2025.

- Rivera-Arriaga, E. and Escofet, A. Gobernanza socio-ambiental de las zonas costeras y marinas. Las costas mexicanas, contaminación, impacto ambiental, vulnerabilidad y cambio climático [Socio-environmental governance of coastal and marine areas. Mexican coasts, pollution, environmental impact, vulnerability, and climate change]. UNAM, UAC. 2019, p. 465-492.

- Reguero B. G.; Secaira F.; Toimil A.; Escudero M.; Díaz-Simal P.; Beck M. W; Silva R.; Storlazzi C. and Losada I. J. The Risk Reduction Benefits of the Mesoamerican Reef in Mexico. Front. Earth Sci. 2019, 7, 125. [CrossRef]

- García-Aguirre, M. C. and Graciela Pérez-Villegas. Una Visión Global del Deterioro de los Recursos Bióticos Terrestres en México [Una Visión Global del Deterioro de los Recursos Bióticos Terrestres en México]. Revista Geográfica, 2002, 131: 41–77. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40992824. Accessed: 13 December 2015.

- Ortiz-Pérez, M. O., and A. M. Linares. Vulnerabilidad al ascenso del nivel del mar y sus implicaciones en las costas bajas del Golfo de México y Mar Caribe. El Manejo Costero en México, Centro EPOMEX Universidad A. De Campeche, Campeche, México 2004, 307-320. Available online http://etzna.uacam.mx/epomex/pdf/mancos/cap20.pdf Accesed 28 March 2025.

- Escudero, M.; Silva R. and Mendoza E. Beach Erosion Driven by Natural and Human Activity at Isla del Carmen Barrier Island, Mexico, Journal of Coastal Research. 2014, 71:62-74. [CrossRef]

- Aragón, M. M. Impactos ambientales generados por el caso Malecón, Cancún (Proyecto Tajamar), Quintana Roo, México. Reflexiones para el desarrollo sustentable del turismo [Environmental impacts generated by the Malecón case, Cancún (Tajamar Project), Quintana Roo, Mexico. Reflections on sustainable tourism development]. Ciencia y Mar. 2017, 21, 62, p 37-55. Avaliable online: https://shorturl.at/V3pJh Accessed 28 March 2025.

- Córdova-Tapia, F.; Zambrano-González, L.; Acosta-Sinencio, S. D.; Levy-Gálvez, K.; Ornelas-García, C. P.; Figueroa-Díaz., M. F. Análisis de la Manifestación de Impacto Ambiental del Proyecto “Cabo Dorado” 03BS2014T0002" [Analysis of the Environmental Impact Statement for the "Cabo Dorado" Project 03BS2014T0002]. 2014. Available online: https://shorturl.at/HsCWf Accessed 28 March 2025.

- Garver, G., and Podhora, A. Transboundary environmental impact assessment as part of the North American Agreement on Environmental Cooperation. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal. 2008, 26.4, 253-263. Available online: https://doi.org/10.3152/146155108x366013 Accessed 28 March 2025.

- Nava-Fuentes, J. C.; Arenas-Granados, P. and Cardoso-Martins, F. Integrated coastal management in Campeche, Mexico; a review after the Mexican marine and coastal national policy. Ocean & Coastal Management. 2018. 154, 34–45. [CrossRef]

- Gardner, H. (1973) The contribution of operativity to naming capacity in aphasic patients. Neuropsychologia. 11, 213-220. [CrossRef]

- Howard, D., Best, W., Bruce, C., y Gatehouse, C. Operativity and animacy effects in aphasic naming. European journal of disorders of communication. 1995, 30, 3, 286-302. [CrossRef]

- Dul, J. Necessary condition analysis (NCA) logic and methodology of necessary but not sufficient causality. Organizational Research Methods. 2016, 19.1, 10-52. [CrossRef]

- Löfstedt, R. E. The swing of the regulatory pendulum in Europe: from precautionary principle to (regulatory) impact analysis. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty. 2004, 28, p 237-260. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/B:RISK.0000026097.72268.8d Accessed 28 March 2025.

- ¿Qué es la Administración Pública Federal? [What is Federal Public Administration?] March 28, 2025. URL: https://www.gob.mx/gobierno.

- Leyes y Normas del Sector Medio Ambiente [Environmental Sector Laws and Regulations]. March 28, 2025. URL: https://www.gob.mx/semarnat/acciones-y-programas/leyes-y-normas-del-sector-medio-ambiente).

- INEGI. Censo de Población y Vivienda 2020: Datos de municipios [Conjunto de datos][ Census of Population and Housing 2020: Municipalities data [Dataset]]. Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. 2020. Available Online https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/ccpv/2020/ Accesed 20 March 2021.

- Azuz-Adeath, I. and Rivera-Arriaga, E. Descripción de la dinámica poblacional en la zona costera mexicana durante el periodo 2000-2005 [Description of the population dynamics in the Mexican coastal zone during the period 2000-2005]. Papeles de población. 2009, 15, 62, 75-107. Available onlie: http://scielo.unam.mx/pdf//pp/v15n62/v15n62a3.pdf Accessed 28 March 2025.

- The World Fact Book Field Listing Coastline. November 21 de noviembre de 2022. https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/field/coastline/.

- INEGI Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática. Anuario Estadístico de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos 2011 [Statistical Yearbook of the United Mexican States 2011]. Mexico. 2012. Available online: http://internet.contenidos.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/Productos/prod_serv/contenidos/espanol/bvinegi/productos/integracion/pais/aeeum/2011/Aeeum11_1.pdf Accesed 28 March 2025.

- Línea de costa de la República Mexicana (2011 -2014) [Coastline of the Mexican Republic (2011 –2014]. November 21, 2022 http://geoportal.conabio.gob.mx/metadatos/doc/html/lc2018gw.html.

- Ortiz-Pérez. M. A, and de la Lanza-Espino G. Diferenciación del Espacio Costero de México: un Inventario Regional. Serie Textos Universitarios Núm. 3. Available online: https://publicaciones.geografia.unam.mx/index.php/ig/catalog/book/29 Accesed 17 November 2024.

- Ley Orgánica de la Armada de México § Capítulo II § Artículo 2. [Organic Law of the Mexican Navy § Chapter II § Article 2. Official Gazette of the Federation DOF 01-12-2023]. Available online: https://www.diputados.gob.mx/LeyesBiblio/pdf/LOAM.pdf Acessed 28 March 2025.

- Cortina-Segovia, S.; Brachet-Barro, G.; Ibáñez de la Calle, M. and Quiñones-Valadez, L. Océanos y costas. Análisis del marco jurídico e instrumentos de política ambiental. Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (SEMARNAT) México .2007. 233 p. Available oline: https://biblioteca.semarnat.gob.mx/janium/Documentos/Ciga/Libros2013/CD002182.pdf Accesed 28 March 2025.

- Merino, M. The coastal zone of Mexico. Coastal Management. 1987, 15, 1, p 27-42. [CrossRef]

- Padilla y Sotelo, L. S.; Juárez-Gutiérrez, M. del C. and Propín-Frejomil, E.. Población y economía en el territorio costero de México. 2009. Available online: http://coralito.umar.mx:8383/jspui/bitstream/123456789/1384/1/Poblaci%c3%b3n%20y%20econom%c3%ada%20en%20el%20territorio%20costero%20de%20M%c3%a9xico.pdf Accesed 28 March 2025.

- De la Lanza Espino, G. Gran escenario de la zona costera y oceánica de México [Great scenery of Mexico's coastal and oceanic zone]. Ciencias, 2004, 076. Available onlline: file:///home/yvsa/Escritorio/_astrid_sg,+CNS07602.pdf Accesed 28 March 2025.

- Yáñez-Arancibia, A. México 62% Mar. Boletín Informativo Red Ibermar Iberoamericana. 2015, 9, 7-10. Available onlline: https://hum117.uca.es/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/BOLETIN-09-IBERMAR.pdf Accessed 23 December 2016.

- Ohenhen, L. O., Shirzaei, M., Ojha, C., Sherpa, S. F., & Nicholls, R. J. Disappearing cities on US coasts. Nature. (2024), 627, 8002, 108-115. [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Romero, J. G., Pressey, R. L., Ban, N. C., Torre-Cosío, J., and Aburto-Oropeza, O. (2013). Marine conservation planning in practice: lessons learned from the Gulf of California. Aquatic Conservation: marine and freshwater ecosystems, 23(4), 483-505.

- Kuznets, S. History of Economic Thought-History of Economic Analysis, by Joseph A. Schumpeter. Edited from manuscript by Elizabeth Boody Schumpeter. New York: Oxford University Press, 1954. Pp. xxv, 1260. The Journal of Economic History, 15, 3, 323-325. [CrossRef]

- Comisión Reguladora de Energía (CRE). Evaluación de impacto ambiental del proyecto Energía Costa Azul Investigación y Consultas. Gobierno de México. 2022. Available online: https://www.diputados.gob.mx/documentos/mayo/290411.pdf Accesed. 30 March 20205.

- Sandifer, P. A. Linking coastal environmental and health observations for human wellbeing. Frontiers in Public Health. 2023, 11, p. 1202118. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/public-health/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1202118/full Accesed 30 March 20205.

- Costanzo, S.D., Blancard, C., Davidson, S., Dennison, W.C., Escurra, J., Freeman, S., Fries, A., Kelsey, R.H., Krchnak, K., Sherman, J., Thieme, and M. Vargas-Nguyen, V. Practitioner's Guide to Developing River Basin Report Cards. IAN Press. Cambridge MD USA. (2017). Available online: https://shorturl.at/R7Hxk Accesed 30 March 2025.

- Qué son las tarjetas de reporte? [What are transportation cards?]. March 30 2025. URL: https://www.lanresc.mx/publicaciones/tarjetas_reporte/.

- Orozco-Garibay, P. A. El Estado Mexicano. Su estructura constitucional. Jurídicas. Biblioteca Jurídica Virtual del Instituto de Investigaciones Jurídicas de la UNAM. 2004. Available online: http://historico.juridicas.unam.mx/publica/librev/rev/mexder/cont/6/cnt/cnt1.pdf Accesed 22 d November 2020.

| Marine Ecoregions | POET | Year of decree | ||

| Name | Area (km²) | Percentage (%) | ||

| Gulf of California | 262,284 | 8.31 | Gulf of California | 2006 |

| Gulf of México North | 75,298 | 2.39 | Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea |

2012 |

| Gulf of México South | 663,182 | 21.01 | Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea | 2012 |

| Caribbean Sea | 95,534 | 3.03 | Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea | 2012 |

| Central American Pacific | 148,923 | 4.72 | None | None |

| Sud Californian Pacific | 808,154 | 25.61 | North Pacific | 2018 |

| Transitional Pacific of Monterey | 65,225 | 2.07 | North Pacific | 2018 |

| Mexican Transitional Pacific | 1,037,587 | 32.87 | None | None |

| Total | 1,969,677.28 | 62.4 | ||

| Municipal Scope |

| CON-1 The territorial scope of application of the POET includes the municipalities of the MCZ. CON-2 The administrative organizational structure of coastal municipalities includes agencies that regulate productive activities in the coastal zone under municipal jurisdiction. CON-3 The operators of the agencies responsible for municipal land use control are aware of the technical, administrative, and legal capacities to apply ecological criteria of the POET and its complementary instruments. The operators of the agencies responsible for municipal land use control have the technical competencies to interpret the ecological guidelines and criteria of the POET. CON-5 The operators of the agencies responsible for municipal land use control have timely access to information on the state of the coastal territory subject to pressure from land use change, which allows them to apply environmental criteria. CON-6 Stakeholders, users, owners, or interested parties of the MCZ space under municipal jurisdiction are aware of the POET and its land use regulatory role. CON-7 Stakeholders, users, owners, or interested parties of the MCZ under municipal jurisdiction have a point of contact with the agencies responsible for land use control that guides them on applying the POET's ecological guidelines and criteria CON-8 The POET has clear and measurable ecological guidelines. They include goals or general statements that reflect the desired environmental status of an environmental management unit. CON-9 The operators of the agencies responsible for municipal land use control have the technical capacity to construct guidelines based on other similar elements, such as environmental policies, ecological criteria, or other components that express in some way the goals or objectives to be achieved in the area subject to pressure from land use change. CON-10 The actors, users, owners, or interested parties of the MCZ space under municipal jurisdiction carry out changes in land use if and only if they have authorization. CON-11 Stakeholders, users, owners, or interested parties in the MCZ under municipal jurisdiction that do not carry out land use changes are sanctioned by the corresponding authorities. CON-12 The land use change control mechanisms of coastal municipalities have mechanisms to compensate for unauthorized changes and the resulting environmental damage. CON-13 There is basic reference information for the operators of the agencies responsible for land use control in coastal municipalities to consult or generate environmental indicators of pressure, status, and response. CON-14 The operators of the agencies responsible for land use control in coastal municipalities are aware of their territorial jurisdiction in terms of land use regulation. CON-15 The operators of the agencies responsible for land use control in coastal municipalities are limited to acting within their territorial scope of jurisdiction in land use regulation. CON-16 When the operators of the agencies responsible for land use control in coastal municipalities detect that a stakeholder does not know to which agency he/she should apply for a land use change, they guide and direct him/her to the corresponding agency. CON-17 The municipal governments, through their agencies, promote urban development based on sustainability criteria through an administrative framework congruent between environmental policy and urban development that induces the creation of territorial reserves and the location of productive and commercial activities with a logic of sustainability. CON-18 The operators of the agencies responsible for the control of municipal land use have both administrative and technical faculties and competencies to carry out inspection and surveillance tasks of land use in the MCZ. CON-19 The knowledge and information about the characteristics, dynamics, and state of the environment in the MCZ is available in such a way that the operators of the agencies responsible for municipal land use control can consult it in an agile and expeditious manner. CON-20 The operators of the agencies responsible for municipal land use control have sufficient material, legal, administrative, and financial resources to carry out land use inspection and surveillance tasks in the MCZ. CON-21 The operators of the agencies responsible for municipal land use control have the working conditions that allow them to perform their duties adequately, effectively, and efficiently. CON-22 The POET has implementation instruments at the municipal level that coordinate its efforts with the state and federal levels. CON-23 The operators of the agencies responsible for land use control in coastal municipalities are aware of the POET implementation instruments that coordinate the efforts of the three levels of government. CON-24 There are instruments for the effective promotion of social participation in the POET implementation process at the municipal level. CON-25 There are effective and efficient instruments for the follow-up of POET implementation actions that are operated by the agencies responsible for land use control at the municipal level. |

| State Scope |

| CON-26 The operators of state agencies that promote land use changes in areas of the MCZ are aware of the POET. CON-27 State agency operators promote land use changes in MCZ areas if and only if they are compatible with the POET management model. CON-28 The operators of the state agencies responsible for managing sectorial activities have technical, administrative, and legal capacities to apply the ecological criteria of the POET and its complementary instruments. CON-29 The operators of the state agencies promote the development of the sectorial activities they manage if and only if they are compatible and contribute to the POET management model. CON-30 The operators of the state agencies promote the development of sectorial activities if and only if these, in turn, promote socioeconomic development based on sustainability criteria through a congruent administrative framework between environmental policy and development. CON-31 The operators of the state agencies responsible for managing sectorial activities have administrative and technical powers and competencies to conduct inspections and surveillance of land use in the MCZ CON-32 When the operators of the agencies responsible for the management of sectorial activities detect changes in land use that contravene the POET provisions, they notify the corresponding authorities. CON-33 The POET relies on instruments of execution at the state level to coordinate its efforts with those of the municipal and federal levels. CON-34 The operators of the state agencies that promote the development of sectorial activities are aware of the POET execution instruments that coordinate the efforts of the three levels of government. CON-35 Effective and efficient instruments exist for adequately promoting social participation in the POET execution process at the state level. CON-36 There are effective and efficient instruments for the follow-up of POET implementation actions that are operated by the agencies responsible for land use control at the state level. |

| Federal Scope |

| CON-37 The operators of the federal agencies with powers to authorize the use of marine waters, their elements and natural resources, their adjacent federal zones and the insular territory in areas of the MCZ are aware of the POET. CON-38 The users of marine waters, their elements and natural resources, their adjacent federal zones and the insular territory in areas of the MCZ promote and authorize uses if and only if they are compatible with the management model of the POET. CON-39 The operators of the federal agencies responsible for the management of sectorial activities that affect marine waters, their adjacent federal zones and the insular territory in areas of the MCZ have technical, administrative and legal capacities to apply the ecological criteria of the POET and its complementary instruments. CON-40 The operators of the federal agencies responsible for the management of sectorial activities that affect marine waters, their adjacent federal zones and the insular territory in areas of the MCZ have both administrative and technical faculties and competencies to carry out inspection and surveillance tasks of land use in the MCZ. CON-41 Knowledge and information about the characteristics, dynamics and state of the environment in marine waters, their adjacent federal zones and the insular territory in areas of the MCZ is available in such a way that the operators of the federal agencies responsible for their management can consult it in an agile and expeditious manner. CON-42 The operators of the federal agencies responsible for the management of sectorial activities that affect marine waters, their adjacent federal zones and the insular territory in areas of the MCZ have sufficient material, legal, administrative and financial resources to carry out inspection and surveillance tasks of land use in the MCZ. CON-43 The operators of the federal agencies responsible for the management of sectorial activities that affect marine waters, their adjacent federal zones and the insular territory in areas of the MCZ have the working conditions that allow them to carry out their tasks in an adequate, effective and efficient manner. CON-44 The POET has instruments of execution at federal level that coordinate its efforts with the municipal and state levels. CON-45 The operators of the federal agencies responsible for the management of sectorial activities that affect marine waters, their adjacent federal zones and the insular territory in areas of the MCZ are aware of the POET implementation instruments that coordinate the efforts of the three levels of government. CON-46 There are effective and efficient instruments for the effective promotion of social participation in the POET execution process at the federal level. CON-47 There are effective and efficient instruments for the follow-up of POET implementation actions that are operated by the agencies responsible for land use control at the federal level. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).