1. Introduction

Sodium-ion batteries (SIBs), as a potential alternative or complementary technology to lithium-ion batteries (LIBs), offer advantages including low cost, resource abundance, and independence from scarce metal resources. They also demonstrate exceptional high-rate performance and low-temperature operational capabilities, rendering them promising for applications in large-scale energy storage systems, low-speed electric vehicles and two-wheelers, backup power supplies and base stations, as well as hybrid and entry-level electric vehicles. Nevertheless, compared to mature LIB technologies, SIBs still exhibit limitations in capacity retention and cycle stability. The design and development of high-capacity anode materials, as one of the critical components in SIBs, represent a pivotal approach to address the current challenge of low energy density in SIB industrialization [

1,

2,

3]. Although numerous non-carbon-based anode materials [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12] have been extensively investigated, this review will focus specifically on carbon-based anodes, given the industrial demand for more stable cycling performance and cost-effective manufacturing in practical applications. For comprehensive discussions on non-carbon anode systems, readers are referred to specialized reviews [

13,

14]. Carbon-based anodes have recently emerged as a research hotspot in SIB development. To facilitate a systematic understanding for researchers entering this field, this review will: (1) Elucidate sodium storage mechanisms in carbon matrices, with emphasis on how microstructural and compositional characteristics (e.g., closed pores, graphitic domains, mesopores/micropores, heteroatom doping, and sodiophilic interfaces) govern storage behavior (

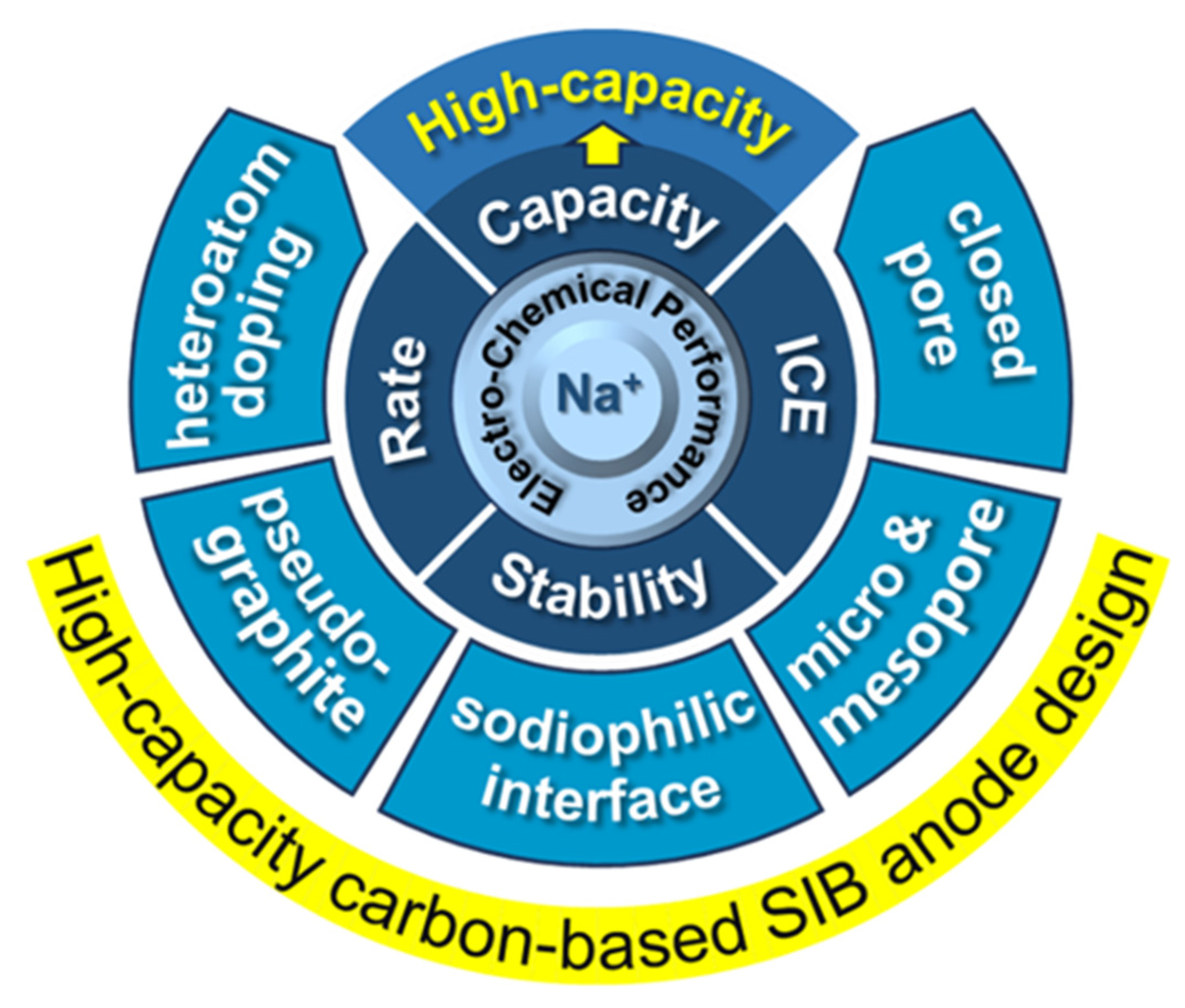

Figure 1); (2) Establish structure-performance relationships between carbon microarchitecture and sodium storage capacity; (3) Analyze recent advances in synthesis methodologies for precise microstructure control and strategies for capacity enhancement; (4) Discuss appropriate characterization techniques for different carbon architectures while addressing common analytical pitfalls; and (5) Provide perspectives on future development directions for high-capacity carbon anodes, proposing actionable pathways for advancing SIB technology.

While numerous reviews on anode materials exist to date, most primarily cater to experienced researchers through detailed methodological descriptions and corresponding electrochemical performance analyses [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. The fundamental objective of this review diverges by specifically addressing the needs of researchers and graduate students newly entering the field of carbon-based anodes. We have deliberately dispensed with conventional formalities and superfluous contextual preliminaries characteristic of traditional reviews, instead presenting a concise yet comprehensive analysis that:

Reveals the fundamental mechanisms enabling sodium storage in carbon matrices

Identifies critical microstructural characteristics and compositional determinants governing sodium storage behavior

Evaluates viable synthesis strategies and characterization methodologies

Establishes rational design principles for carbon-based sodium storage materials

Through this structured approach, we aim to equip readers with a clarified roadmap for future research directions in carbon-based anode development for sodium-ion battery systems.

2. Mechanism for Sodium-Ion Storage

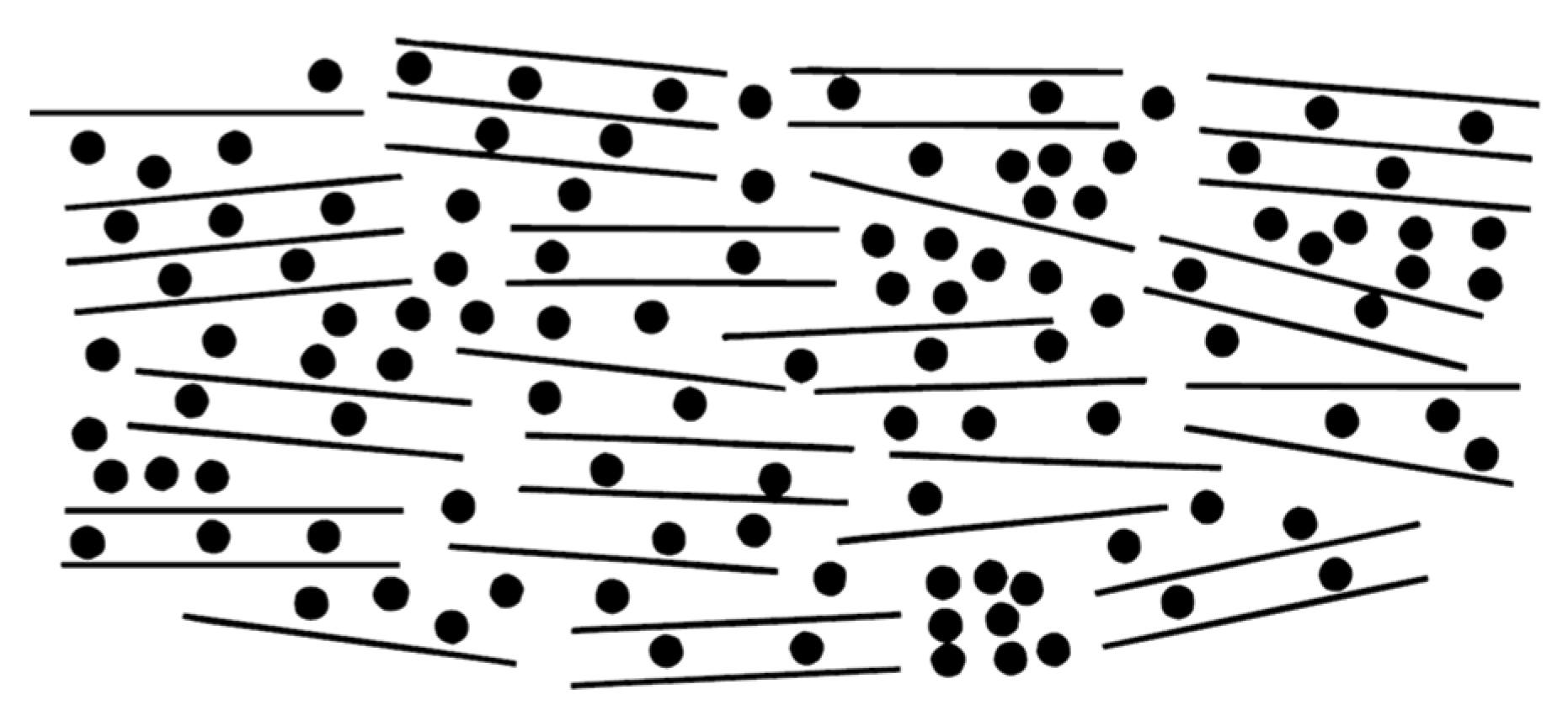

The most prevalent storage mechanism in reversible sodium-ion batteries operates through the rocking-chair principle, where sodium ions serve as charge carriers migrating between cathode and anode during redox reactions. This ion shuttle drives electron flow in the external circuit, enabling interconversion between chemical and electrical energy. Notably, this discussion intentionally excludes alkali metal deposition processes on current collectors, as the inevitable dendrite formation associated with metal plating would significantly compromise cycle stability. Therefore, optimal systems should maintain sodium ions within host structures - materials requiring both sufficient sodium accommodation capacity and efficient ion transport pathways. Stevens and Dahn addressed this dual requirement through their proposed "house of cards" structural model (

Figure 2) [

22]. In this architecture, carbon atomic "bricks" form the walls and corridors of the card-house structure. Current research focuses on engineering these carbon building blocks into optimized configurations that simultaneously maximize sodium storage density and provide unobstructed sodium ion transport pathways.

Natural precursors such as biomass [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27] and anthracite [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32] can spontaneously form sodium-accommodating "host structures" through high-temperature carbonization. However, these naturally derived precursors inherently lack precise control over their resultant carbon microarchitectures. While optimization strategies like pre-oxidation treatments [

33,

34], controlled carbonization protocols [

35,

36], and carbonization atmosphere regulation [

37] have proven effective in enhancing electrochemical performance, the fundamental relationship between carbon microstructure and sodium storage mechanisms remains a subject of ongoing investigation and debate. The inherent compositional and structural variability of natural precursors during pyrolysis often leads to performance degradation through two primary pathways: i) Irreversible sodium trapping at structural defects, which reduces initial Coulombic efficiency (ICE) and diminishes full-cell capacity. This has driven widespread adoption of pre-sodiation strategies in both research and industrial applications to mitigate ICE limitations [

38,

39,

40,

41]; ii) Partial graphitization-induced contraction of interlayer spacing, which compromises ionic conductivity and simultaneously degrades both capacity and rate capability. These challenges highlight the promise of rationally designed carbon composite architectures for high-capacity applications, though precise molecular-level structural engineering remains technically demanding. Recent advances focus on constructing closed-pore and graphitic domain models through precursor composition design and microstructure manipulation, aiming to establish explicit structure-performance correlations [

42,

43,

44,

45]. While these pioneering studies provide novel insights into carbon anode optimization, the realization of ideal sodium storage configurations remains elusive. This review systematically analyzes current research efforts across various model systems to elucidate critical structure-energy storage relationships.

2.1. Graphite

Graphite serves as the foundational carbon material in energy storage systems, with its natural interlayer spacing (~0.335 nm) being optimally suited for smaller Li⁺ ions (ionic radius: 0.076 nm). This configuration enables a theoretical lithium storage capacity of 372 mAh/g, typically represented by the simplified formula LiC₆. However, larger alkali ions such as Na⁺ (0.102 nm) and K⁺ (0.138 nm) face significant challenges in overcoming the π-π interactions between graphene layers. While steric hindrance fundamentally limits intercalation of these larger ions, their insertion behavior is ultimately governed by the thermodynamic-kinetic interplay involving [

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51]: i) Diffusion energy barriers; ii) Formation of stable intercalation phases; iii) Solvation shell effects. For sodium ions specifically, intercalation into graphite induces severe structural degradation due to lattice mismatch, resulting in negligible practical capacity (<35 mAh/g). Interestingly, despite K⁺'s larger ionic radius and more pronounced volumetric expansion (~60% vs. 10% for Li⁺), potassium demonstrates superior storage capability (279 mAh/g, represented as KC₈) through three key mechanisms: i) Lower diffusion barriers enabling faster kinetics; ii) Dynamic interlayer spacing accommodation during insertion; iii) Reversible phase transitions maintaining structural integrity.

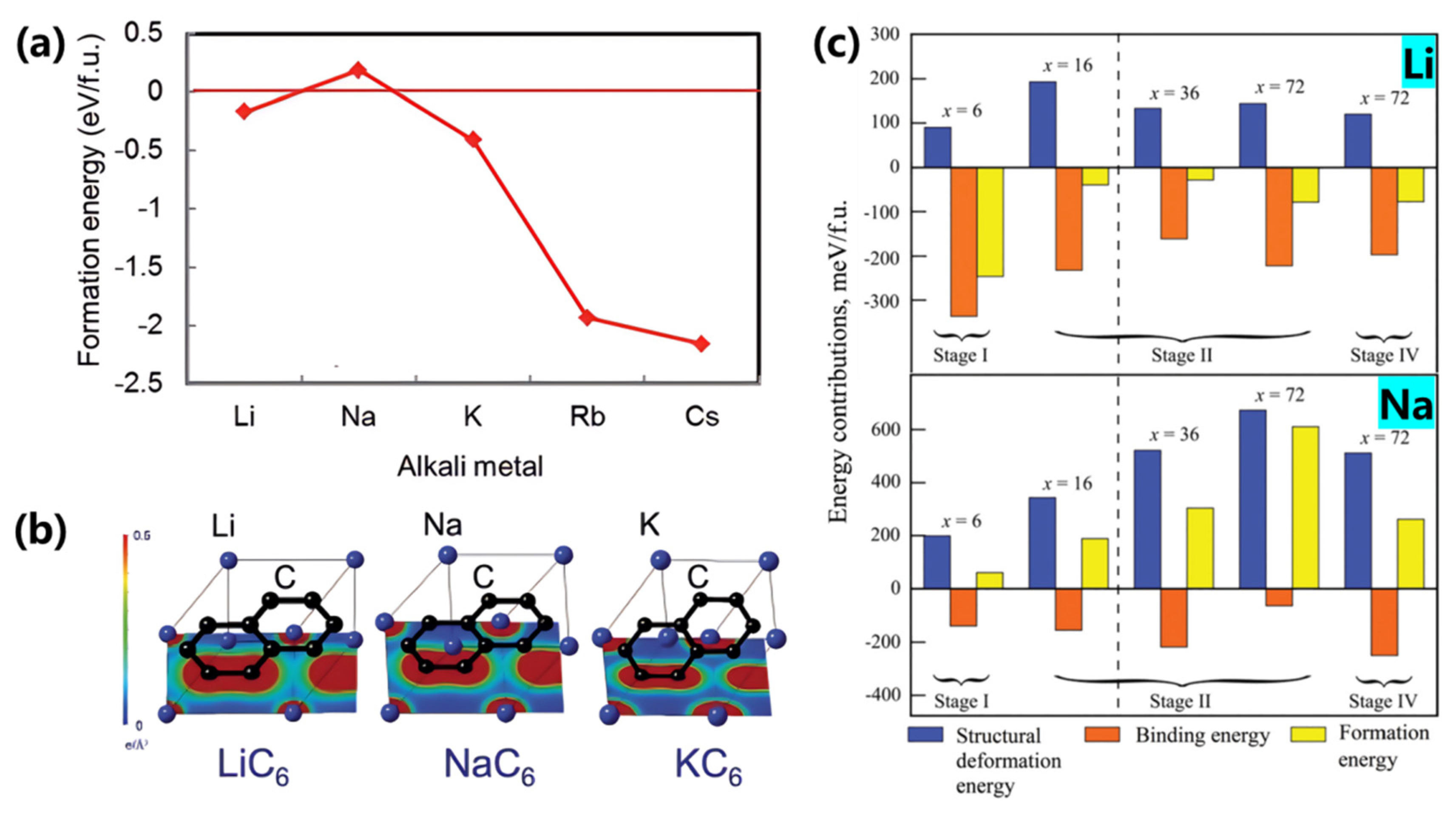

Moriwake et al. [

52] employed density functional theory (DFT) calculations incorporating van der Waals functionals to investigate the formation energy of AmC₆ configurations (where Am = alkali metals) in graphite intercalation compounds (GICs). As shown in

Figure 3, the formation energy between alkali metals and carbon gradually decreases from sodium to cesium, primarily attributed to increasing ionic radii and evolving chemical bonding characteristics. Larger alkali metal ions exhibit enhanced ionic character in metal-carbon bonds, leading to more negative (stable) formation energies. Specifically, sodium ions (Na⁺) demonstrate positive formation energy values, indicating thermodynamic instability of Na-GICs. In contrast, larger alkali metals (K, Rb, Cs) exhibit progressively negative formation energies (

Figure 3a). Notably, lithium deviates from this trend due to its smaller ionic radius and distinct Li-C covalent interactions (

Figure 3b), making sodium the most challenging alkali metal for graphite intercalation.

Mollenhauer et al. [

53] further analyzed formation energy differences in Li/Na/K-GICs through first-principles calculations (

Figure 3c), defining total formation energy as the sum of structural deformation energy and metal-carbon binding energy. The strong covalent interaction between small Li⁺ ions and carbon atoms creates significant orbital overlap, while larger Na atoms exhibit negligible covalent bonding. This fundamental distinction explains why lithium breaks the alkali metal size trend in GICs.

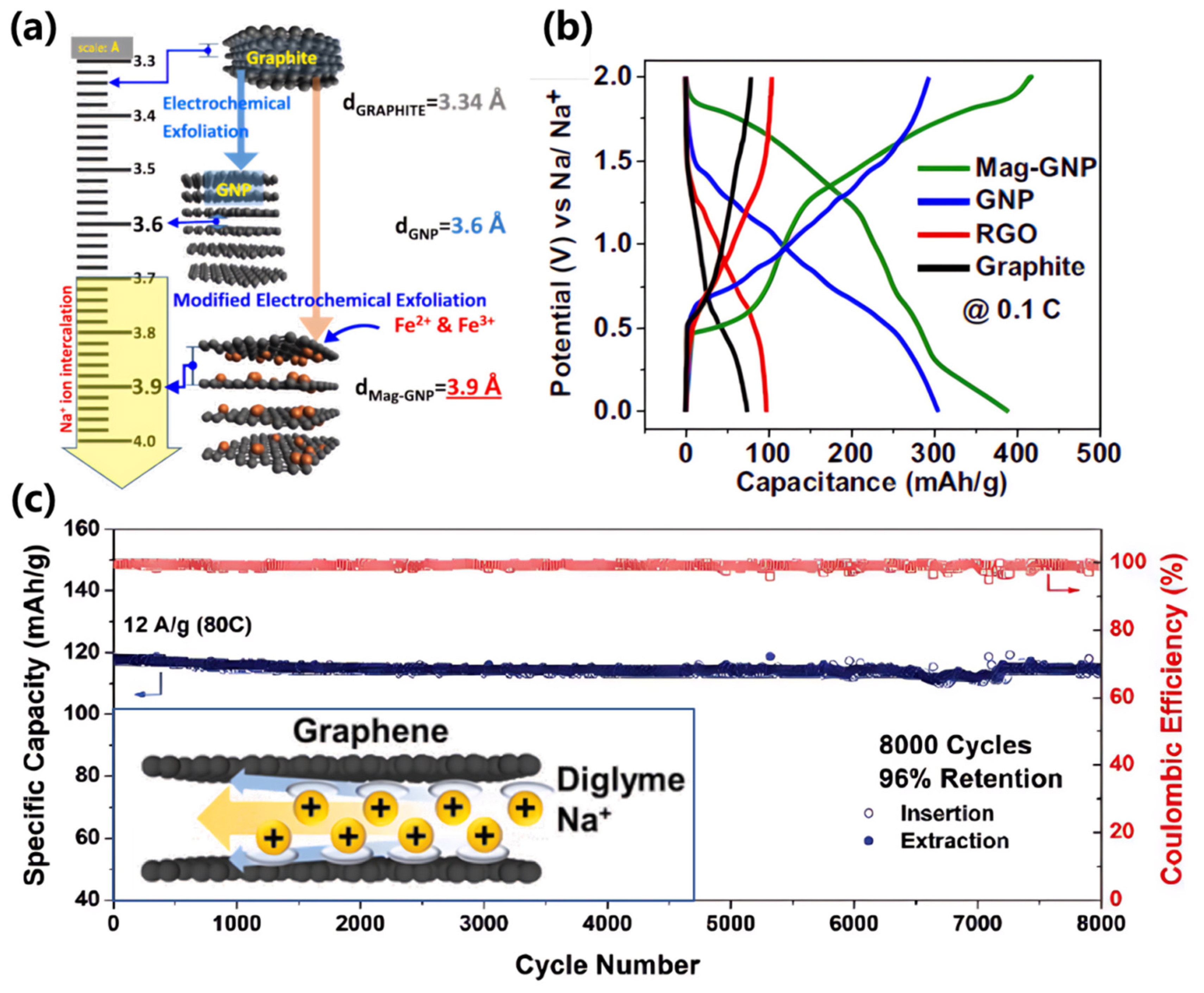

The inherent instability of Na-GICs - stemming from weak binding energy and substantial structural deformation requirements - precludes direct application in sodium-ion battery anodes. However, interlayer spacing expansion strategies can effectively reduce deformation energy and enhance capacity to 200-300 mAh/g. Current approaches include: i) Intercalation-mediated expansion: Inserting metal ions, solvent molecules, or polymers to enlarge interlayer spacing while enhancing sodium binding energy (

Figure 4a) [

54]. Ii) Chemical oxidation: Treating graphite with strong oxidizers (HNO₃, H₂SO₄) to generate oxygen-containing functional groups (carboxyl, epoxy), expanding interlayer spacing to 0.4-0.45 nm. Reduced graphene oxide (rGO) demonstrates reversible capacities of 200-300 mAh/g (

Figure 4c) [

55]. These methodologies will be further discussed in subsequent sections addressing heteroatom doping and pseudo-graphitic domain engineering.

2.2. Pseudo-Graphite

Compared to graphite anodes discussed in the preceding section, hard carbon is recognized as the optimal anode material for sodium-ion batteries (SIBs), delivering a specific capacity of 300-400 mAh/g [

56]. Concurrently, achieving lower sodium insertion voltage plateaus has become a critical research focus to enhance full-cell operating voltage. The observed plateau capacity is predominantly attributed to contributions from pseudo-graphitic domains and closed pores. However, the stochastic formation of these structures during precursor carbonization makes it inherently challenging to definitively distinguish their respective sodium storage mechanisms. Recent efforts employ molecular design strategies to synthesize hard carbons with enriched pseudo-graphitic domains or closed-pore architectures, aiming to elucidate their distinct electrochemical signatures [

57].

Pseudo-graphitic domains are characterized by interlayer spacings (d

002) of 0.36-0.40 nm, facilitating sodium ion intercalation/deintercalation and manifesting as voltage plateaus [

58]. Notably, interlayer spacing alone cannot serve as a definitive criterion for pseudo-graphitic identification. Karunarathna et al. demonstrated this limitation through Fe

2+/Fe

3+-intercalated graphite via electrochemical exfoliation, achieving expanded interlayer spacings (0.36-0.39 nm) without exhibiting the characteristic low-voltage plateau (<0.1 V vs. Na

+/Na) observed in hard carbons (

Figure 4b). This underscores that pseudo-graphitic structures in hard carbons derive not merely from increased d

002 spacing, but also from structural distortions induced by heteroatom doping, irregular carbon layer stacking, or lattice defects. These structural modifications enhance electrochemical performance by: i) Providing additional active sites for sodium storage, ii) Improving structural resilience during cycling, and iii) Optimizing sodium diffusion pathways. In contrast to closed-pore storage mechanisms, pseudo-graphitic domains primarily operate through intercalation-based sodium storage. This process involves reversible insertion/extraction of sodium ions between carbon layers, mediated by dynamic interactions between Na+ and the carbon matrix. The sodium storage capacity and kinetics of pseudo-graphitic structures are critically dependent on: i) Interlayer spacing optimization, ii) Structural defect engineering, and iii) Electron/ion transport synergy. Well-designed pseudo-graphitic architectures enable rapid sodium ion diffusion while maintaining structural integrity, significantly enhancing rate capability and cycling stability compared to conventional graphite-based systems.

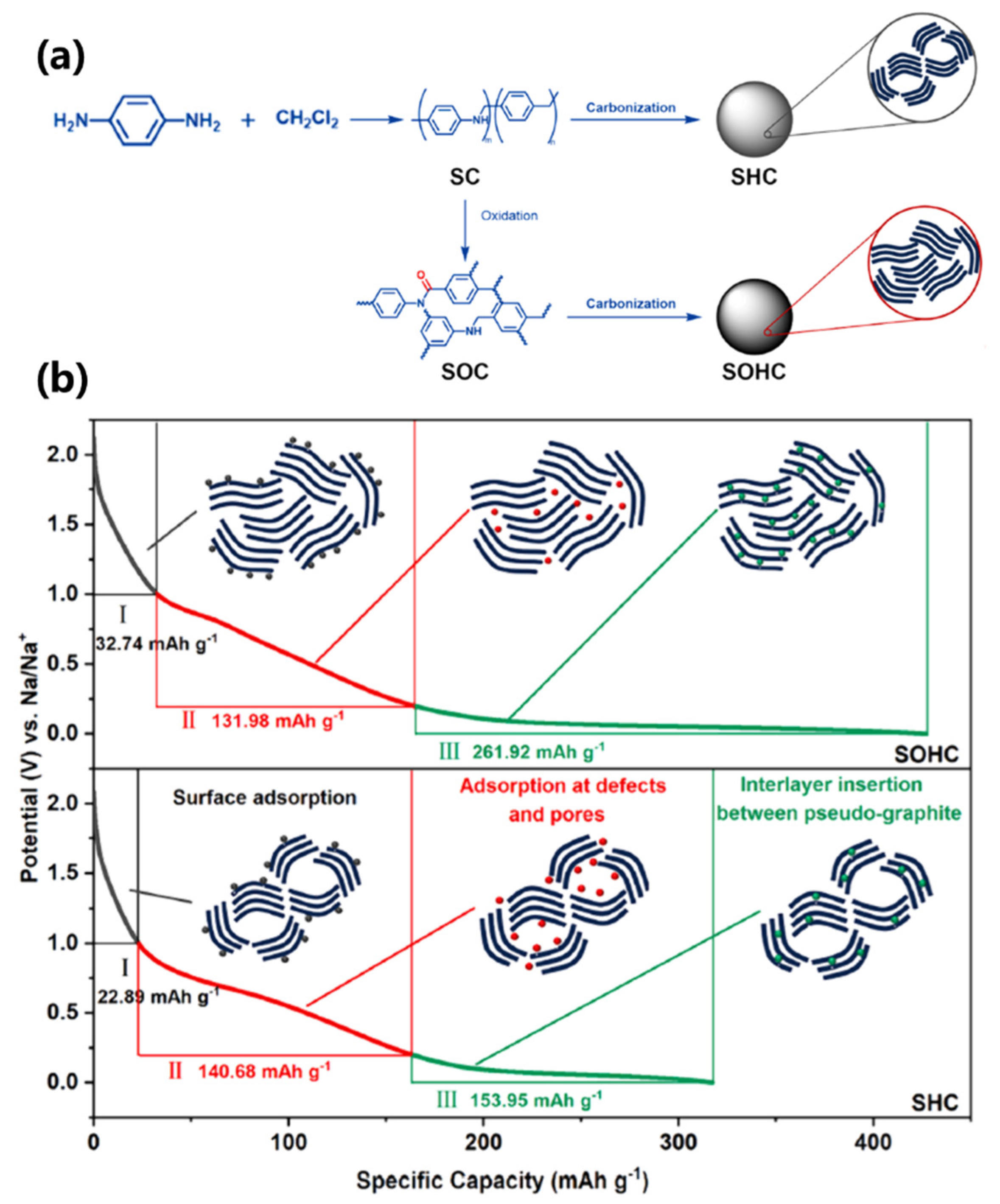

The sodium ion intercalation behavior within pseudo-graphitic layers involves diffusion-limited kinetics, typically manifested in low-voltage plateau regions where diffusion coefficients exhibit rapid decline [

59]. This phenomenon arises from the constrained ion transport through narrow interlayer spacings during NaCx compound formation, resulting in distinct voltage plateaus below 0.1 V [

60]. In recent mechanistic studies, Zhao et al. [

61] synthesized two distinct hard carbon microspheres using p-phenylenediamine and dichloromethane precursors through halogenated amination reaction, oxidative polymerization, and controlled carbonization (

Figure 5a). The pseudo-graphitic-rich microspheres demonstrated a total capacity of 339 mAh/g, with 262 mAh/g attributed to plateau capacity from pseudo-graphitic domains (

Figure 5b). This model conclusively demonstrates the dominant contribution of pseudo-graphitic domains to plateau capacity.

Wang et al. [

62] further advanced this understanding through pre-oxidation treatment of lignin derivatives. The introduced oxygen-containing functional groups effectively truncated long side chains in lignin's aromatic units, promoting crosslinking during pyrolysis to form three-dimensional network structures. This approach enabled precise control over pseudo-graphitic/closed-pore ratios, revealing that increased pseudo-graphitic content significantly enhances both plateau capacity and rate performance. The expanded interlayer spacing in pseudo-graphitic structures (compared to conventional graphite) reduces structural deformation energy requirements during sodium intercalation, fundamentally altering sodium diffusion kinetics and storage behavior.

To optimize sodium storage capacity and kinetics, three primary pseudo-graphitic engineering strategies have emerged: i) Thermal treatment optimization: Precise control of carbonization temperatures (800-1600°C) and heating rates (2-10°C/min) enables tailored graphitization degrees and pseudo-graphitic domain formation [

35,

63]; ii) Heteroatom doping: Strategic incorporation of metal ions (e.g., Fe, Co) or non-metallic elements (e.g., N, S) enhances graphitization efficiency and stabilizes pseudo-graphitic architectures [

3,

64]; iii) Pre-oxidation engineering: Controlled oxidation of precursors using O2 or H2O2 introduces oxygen functional groups that modify pyrolysis pathways, promoting crosslinking reactions that simultaneously increase pseudo-graphitic domains and functional closed pores [

65,

66]. These synergistic approaches enable coordinated optimization of pseudo-graphitic domains and closed-pore architectures, achieving enhanced sodium storage capacity (300-400 mAh/g) with improved rate capability (>80% capacity retention at 2C).

2.3. Closed Pore

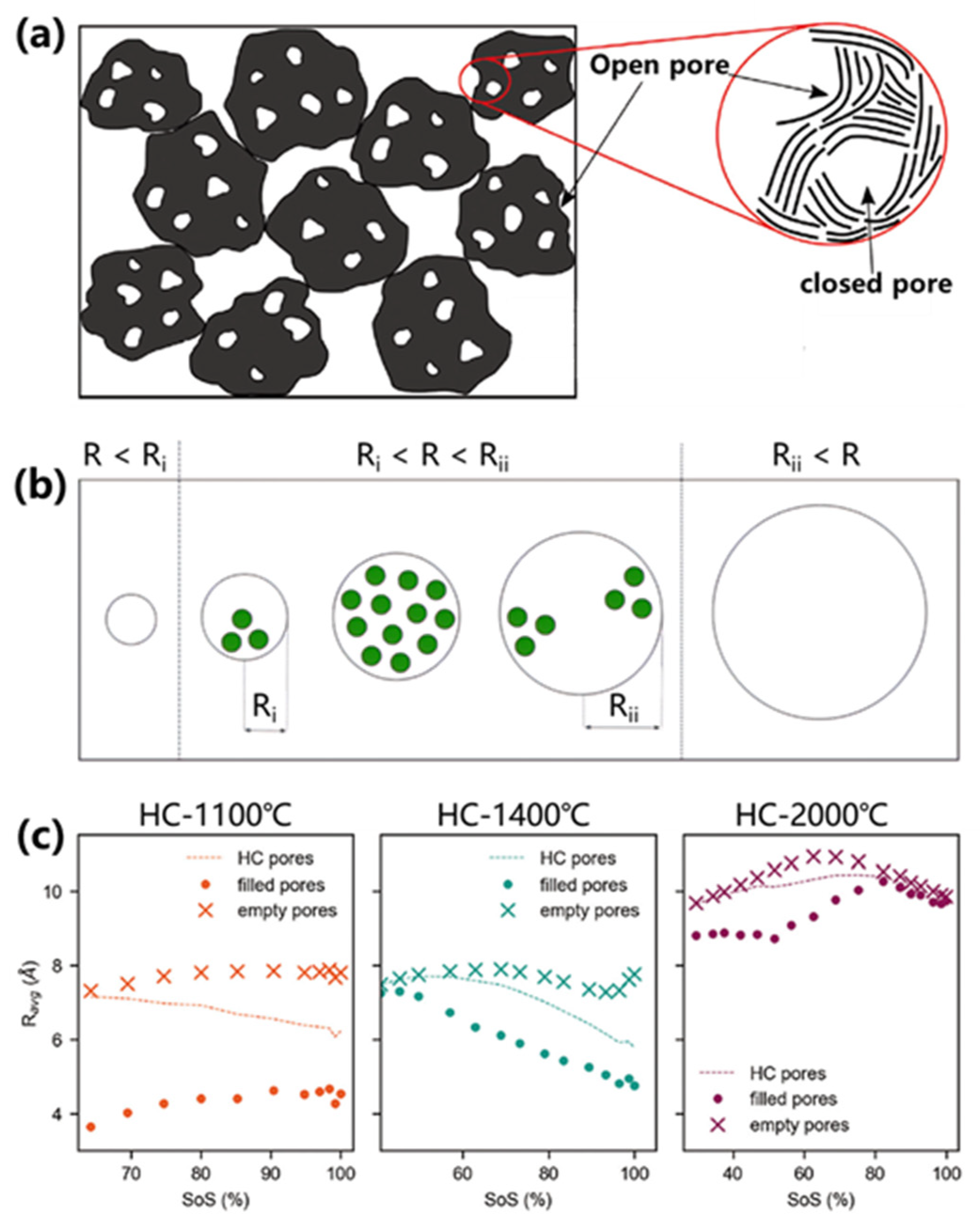

In describing the microscopic molecular or elemental composition of hard carbon materials, researchers typically seek definitive theoretical models for mechanistic understanding. A conventional conceptualization portrays closed/open pores in hard carbon as idealized void spaces (

Figure 6a) [

67], where closed pores provide sodium storage "containers" bounded by carbon walls. However, the actual structural complexity far exceeds these simplified representations, and the precise definition of closed pores remains debated. Key unresolved questions include: i) Are closed pores formed by wrinkled graphene stacking? ii) Do they originate from localized carbon defects? iii) Could folded graphite sheets or fullerene-like cavities (C60, C70) qualify as closed pores? Even with comparable pore sizes detected via small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS), microstructural variations inevitably lead to divergent sodium storage behaviors. Nevertheless, consensus has emerged that closed pores are predominantly filled during low-voltage plateau regions. Current research focuses on engineering optimized closed-pore architectures by controlling pore size distribution, carbon wall crystallinity, defect density, and sodium filling mechanisms.

Recent breakthroughs demonstrate these principles. Song et al. [

68] ingeniously employed zinc gluconate (ZG) precursors with ZnO templates to construct 0.45-4 nm open frameworks, subsequently converted to closed pores through high-temperature carbonization (

Figure 6b). Sodium clusters formed within these closed pores during low-voltage plateaus (<0.1 V), achieving a remarkable capacity of 481.5 mAh/g with 81% plateau contribution (389 mAh/g). This performance enhancement correlated with increased closed-pore density at elevated carbonization temperatures. Complementary studies by Toney et al. revealed critical size effects (

Figure 6c) [

23,

69]. Controlled annealing (1100-2000°C) progressively enlarged closed pores from 5.1 Å to 9.2 Å while enhancing sodium storage capacity. Optimal performance occurred at <1 nm pore sizes, where reduced defect density and minimized sodium surface exposure synergistically lowered deposition overpotentials and improved rate capability. DFT simulations further identified maximum sodium adsorption energy at 0.45 nm pore diameters [

70], underscoring the importance of nanoscale confinement effects.

Beyond capacity enhancement, closed-pore architectures mitigate volume expansion during cycling through mechanical buffering. Effective closed-pore formation requires sufficient graphitic domain lengths and curvature-capable carbon structures.

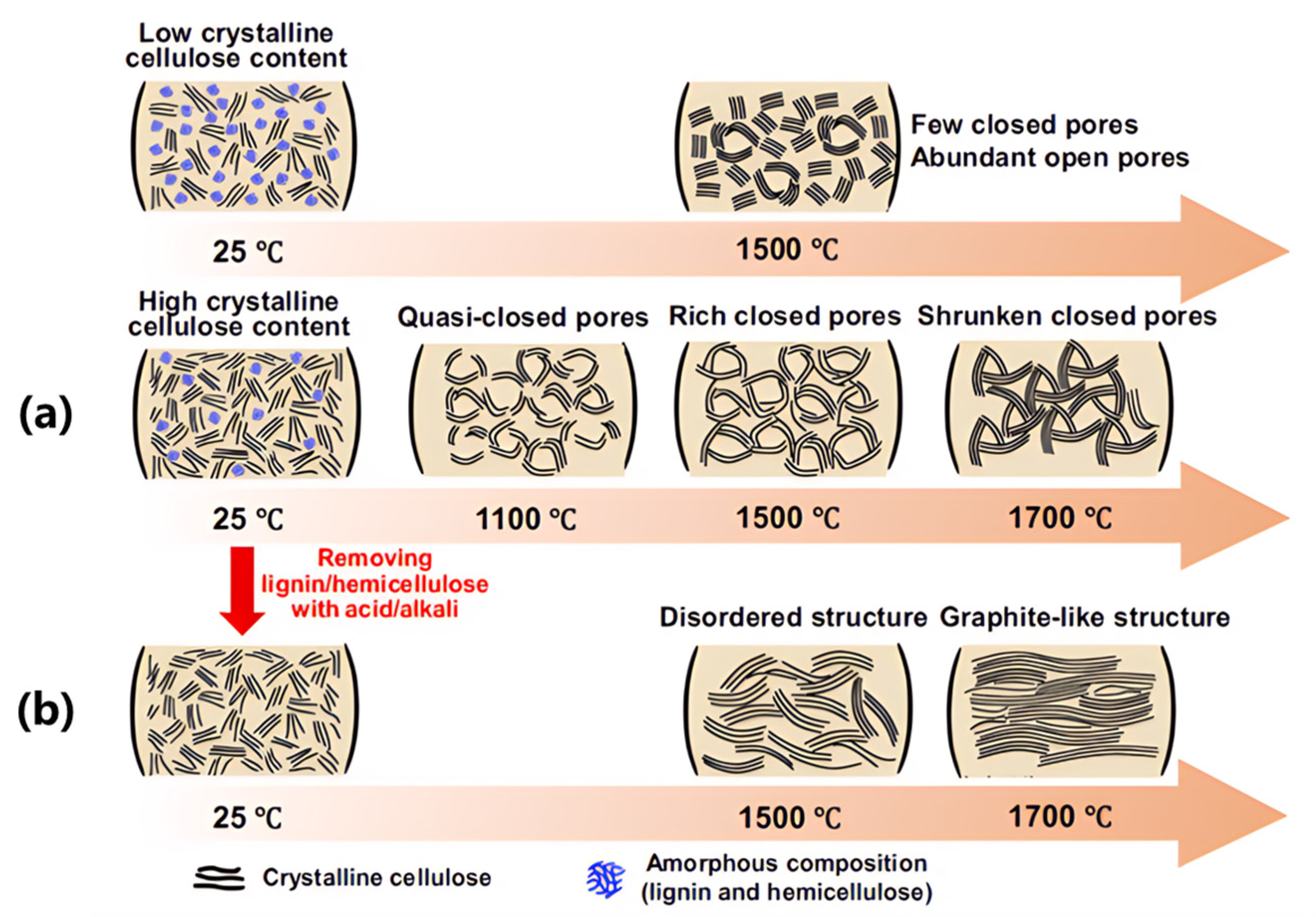

Figure 7 illustrates this principle through cellulose carbonization [

23]: i) Amorphous lignin components prevent excessive graphitization while creating active sites; ii) Crystalline cellulose domains form elongated graphitic walls enclosing closed pores; iii) Removal of lignin disrupts pore formation, yielding non-porous carbon (

Figure 7b). These findings validate the dual-control strategy of precursor composition (cellulose/lignin ratio) and annealing temperature (800-1600°C) for closed-pore engineering [

3,

42,

71,

72].

2.4. Micro- and Mesoporous Structure

Beyond the dominant plateau capacity, carbon anode materials exhibit additional sloping capacity contributions within the 2.0-0.1 V vs. Na+/Na voltage range. While some researchers propose an "intercalation-adsorption" mechanism attributing sloping capacity to Na⁺ intercalation in graphitic-like layers and plateau capacity to micropore filling/deposition [

22,

73], the prevailing consensus associates sloping capacity with Na⁺ adsorption at defect sites and carbon surfaces (including micro/mesoporous interfaces), supported by substantial theoretical and experimental evidence [

17,

74]. The strategic design of mesoporous architectures enhances electrochemical performance through improved ion transport kinetics. Yang and Lv et al. [82] demonstrated that optimized mesoporosity in hard carbons increases active site accessibility and sodium diffusion rates. However, micro/mesoporous structures inherently reduce tap density and introduce surface defects that irreversibly trap sodium ions, thereby compromising initial Coulombic efficiency (ICE). This creates a critical design challenge: balancing pore architecture (size/distribution) with defect engineering to maximize capacity while minimizing irreversible losses. Pore entrance diameter significantly impacts sodium transport dynamics. While narrow micropore entrances (<0.7 nm) may hinder solvated Na⁺ ingress, desolvated ions can permeate through ultramicropores (<0.5 nm) via size-exclusion effects, enabling high-rate performance. Advanced pore engineering strategies include: i) Chemical vapor deposition (CVD) for pore filling in activated carbons; ii) Polyethylene glycol (PEG)-assisted mesopore sealing; and iii) Pitch-derived carbon coatings for selective pore modification [

76,

77,

78]. These approaches effectively suppress detrimental open porosity while preserving functional micropores.

Hu et al. [

79] provided mechanistic clarity through combined DFT calculations and experimental validation. DFT simulations of alkali metal edge adsorption on graphene revealed a zigzag Na configuration with gradually decreasing adsorption energy, consistent with sloping region behavior. Bader charge analysis of sodiated wedge pores showed ≈20% valence electron density transfer to the carbon matrix, localized primarily within pores. This electron redistribution, coupled with density of states (DOS) profiles, confirms the quasi-metallic nature of confined sodium species. The sloping region's storage mechanism involves rapid Na⁺ intercalation and surface diffusion processes. The steep voltage decline reflects efficient sodium insertion into hard carbon's nanostructured pores, forming metastable sodiation phases. This process is governed by nanoscale porosity facilitating fast ion transport, optimized particle size distributions reducing diffusion paths, and iii) defect engineering enhancing adsorption kinetics. During discharge, sodium ions dynamically migrate and accumulate within interconnected pore networks, forming stable interfacial layers that enable high-capacity retention even at elevated rates (>2C). The synergistic combination of rapid ion mobility and confined metallic sodium clusters underpins the sloping region's exceptional rate capability and cycling stability.

3. Conclusion and Perspectives

Current research advancements demonstrate that integrating closed-pore architecture design with pseudo-graphitic configurations represents the cornerstone for developing high-performance carbon-based anodes, simultaneously addressing capacity enhancement and rate capability optimization. The strategic development of closed-pore enriched hard carbon anodes, which synergistically deliver high capacity and cycling stability, has emerged as the dominant paradigm for next-generation sodium-ion battery systems. Future optimization efforts for hard carbon anodes should prioritize: i) Initial Coulombic efficiency improvement; ii) Precise closed-pore diameter control; iii) Defect engineering; iv) Sodium deposition overpotential reduction; and v) Specific surface area minimization. Building upon current precursor selection and carbonization temperature optimization, the following methodologies show potential to advance carbon anode development (

Figure 8):

a) AI-accelerated Molecular Dynamics (AI-MD) for sodium storage mechanism

Current mechanistic studies on sodium storage in hard carbon anodes primarily rely on conventional computational approaches including density functional theory (DFT), Monte Carlo (MC) thermodynamic simulations, and molecular dynamics (MD). While effective for analyzing equilibrium microstructures, these methods face limitations in modeling dynamic sodium transport through complex porous architectures across spatiotemporal scales. Recent breakthroughs in machine-learned interatomic potentials, particularly deep potential models, offer transformative solutions by maintaining quantum-mechanical accuracy while enabling orders-of-magnitude efficiency gains. This computational revolution holds critical significance for establishing a comprehensive theoretical framework of sodium storage mechanisms.

b) Innovative equipment with multi-parameter optimization

Pioneering work by Zhang and Wu [

80] demonstrates that instantaneous sintering thermal pulse technology enables precise control over local graphitization degree and closed nanopore growth in hard carbons. This approach not only extends low-voltage plateau duration but also enhances energy density. Inspired by graphite's sp²-to-sp³ transition under ultrahigh pressure, advanced hot-pressing apparatus could revolutionize carbon microstructure control. Furthermore, this methodology permits low-temperature fabrication of heteroatom-doped carbons with high carbonization degrees, effectively mitigating dopant evaporation during conventional high-temperature treatments.

c) Sodiophilic modification for closed pores

As established in previous sections, closed pores <1 nm facilitate optimal sodium deposition, while larger pores degrade capacity. To harness the potential of expanded pores (1-2 nm), strategic precursor modification through metal doping can introduce sodiophilic sites. These engineered interfaces reduce sodium deposition overpotentials in microporous architectures, enabling high-capacity carbon anodes through enhanced pore-filling efficiency.

d) Novel precursor-engineered fabrication of graphite-like materials with controlled closed-pore architectures

Most hard carbon synthesis follows empirical trial-and-error approaches, evaluating post-carbonization structures and electrochemical performance to identify viable precursors. However, fundamental understanding of closed-pore formation mechanisms during carbonization remains limited - a critical knowledge gap hindering sodium storage optimization. Systematic investigation into carbonization-induced pore evolution represents an essential foundational direction for unlocking the full potential of carbon-based anodes.

e) Metal doping to generate pseudo-graphite

While heteroatom doping has been widely adopted for carbon modification (particularly in porous carbons and catalytic materials), conventional hard carbon synthesis at 1300-1600°C typically causes dopant evaporation. Innovative doping strategies using silicon or transition metals during high-temperature processing offer new pathways for engineering pseudo-graphitic domains and closed-pore architectures. The retained dopants additionally function as overpotential-reducing sites for sodium deposition.

Author Contributions

Y. Z. writing—original draft preparation, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, project administration, funding acquisition; Z. S.: writing—review and editing.

Conflicts of Interest

Declare conflicts of interest or state “The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”

References

- Kim, D.; Kang, S.-H.; Slater, M.; Rood, S.; Vaughey, J. T.; Karan, N.; Balasubramanian, M.; Johnson, C. S. Enabling Sodium Batteries Using Lithium-Substituted Sodium Layered Transition Metal Oxide Cathodes. Adv. Energy Mater. 2011, 1, 333–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, B. L.; Nazar, L. F. Sodium and sodium-ion energy storage batteries. Curr. Opin. Solid St. M. 2012, 16, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; He, X.-X.; Lai, W.-H.; Yang, Z.; Liu, X.-H.; Li, L.; Qiao, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Li, L.; Wu, X.; Chou, S.-L. Catalytic Defect-Repairing Using Manganese Ions for Hard Carbon Anode with High-Capacity and High-Initial-Coulombic-Efficiency in Sodium-Ion Batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2023, 13, 2300444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Park, Y.; Choi, A.; Choi, N.-S.; Kim, J.; Lee, J.; Ryu, J. H.; Oh, S. M.; Lee, K. T. An Amorphous Red Phosphorus/Carbon Composite as a Promising Anode Material for Sodium Ion Batteries. Adv. Mater. 2013, 25, 3045–3049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Hu, S.; Luo, X.; Li, Z.; Sun, X.; Li, M.; Liu, F.; Yu, Y. Confined Amorphous Red Phosphorus in MOF-Derived N-Doped Microporous Carbon as a Superior Anode for Sodium-Ion Battery. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1605820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Sun, C.; Yin, X.; Shen, L.; Shi, Q.; Zhao, K.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, J. FeP Quantum Dots Confined in Carbon-Nanotube-Grafted P-Doped Carbon Octahedra for High-Rate Sodium Storage and Full-Cell Applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 1909283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Kopold, P.; Wu, C.; van Aken, P. A.; Maier, J.; Yu, Y. Uniform yolk–shell Sn4P3@C nanospheres as high-capacity and cycle-stable anode materials for sodium-ion batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 2015, 8, 3531–3538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, K.; Zheng, J.; Wang, G.; Fu, W.; Hao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Cao, X.; Lin, Z.; Liu, J.; Zhang, M.; Shen, Z. FeSe2 Graphite Intercalation Compound as Anode Materials for Sodium Ion Batteries. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2023, 5, 6964–6973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Y.-S.; Li, H.; Zhou, Z.; Armand, M.; Chen, L. Disodium Terephthalate (Na2C8H4O4) as High Performance Anode Material for Low-Cost Room-Temperature Sodium-Ion Battery. Adv. Energy Mater. 2012, 2, 962–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Han, X.; Liu, Y.; Hu, X.; Zhao, Q.; Chen, J. 3D Porous γ-Fe2O3@C Nanocomposite as High-Performance Anode Material of Na-Ion Batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2015, 5, 1401123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Sarkar, S.; Shi, S.; Huang, Q.-A.; Zhao, H.; Yan, L.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, J. Recent Progress in Advanced Organic Electrode Materials for Sodium-Ion Batteries: Synthesis, Mechanisms, Challenges and Perspectives. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 1908445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Ye, J.; Pan, Y.; Liu, K.; Liu, X.; Shui, J. Necklace-Like Sn@C Fiber Self-Supporting Electrode for High-Performance Sodium-Ion Battery. Energy Technol-ger. 2022, 10, 2101024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, F.; Ming, F.; Alshareef, H. N. Sodium-ion battery anodes: Status and future trends. EnergyChem. 2019, 1, 100012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, L. P.; Sougrati, M. T.; Feng, Z.; Leconte, Y.; Fisher, A.; Srinivasan, M.; Xu, Z. A Review on Design Strategies for Carbon Based Metal Oxides and Sulfides Nanocomposites for High Performance Li and Na Ion Battery Anodes. Adv. Energy Mater. 2017, 7, 1601424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Lin, S.; Shu, C.; Tang, Z.; Wang, X.; Wu, Y.; Tang, W. Advances and perspectives of hard carbon anode modulated by defect/hetero elemental engineering for sodium ion batteries. Mater. Today 2025. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Liu, J.; Chen, Y.; Li, S.; Tang, P.; Xie, Y.; Xie, S.; Miao, Z.; Zhu, J.; Yan, X. Graphitization Induction Effect of Hard Carbon for Sodium-Ion Storage. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2424629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, N. Hard carbon for sodium storage: Mechanism and performance optimization. Nano Res 2024, 17, 6038–6057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Ji, S.; Liu, F.; Zhu, Z.; Xiao, J.; Liu, K.; Zhang, Y.; Liao, S.; Zeng, X. A review of the preparation and characterization techniques for closed pores in hard carbon and their functions in sodium-ion batteries. Energy Materials 2025, 5, 500030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Zhang, H.; Gao, F.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Shang, Z.; Gao, C.; Luo, L.; Terrones, M.; Wang, Y. Overview of hard carbon anode for sodium-ion batteries: Influencing factors and strategies to extend slope and plateau regions. Carbon 2024, 228, 119354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wu, C.; He, X.-X.; Zhao, J.; Yang, Z.; Li, L.; Wu, X.; Li, L.; Chou, S.-L. Boosting the Development of Hard Carbon for Sodium-Ion Batteries: Strategies to Optimize the Initial Coulombic Efficiency. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2302277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Togonon, J. J. H.; Chiang, P.-C.; Lin, H.-J.; Tsai, W.-C.; Yen, H.-J. Pure carbon-based electrodes for metal-ion batteries. Carbon Trends 2021, 3, 100035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, D. A.; Dahn, J. R. High Capacity Anode Materials for Rechargeable Sodium-Ion Batteries. J Electrochem Soc. 2000, 147, 1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Zhang, R.; Wang, H.; Zhou, S.; Pan, Z.; Huang, Y.; Sun, D.; Tang, Y.; Ji, X.; Amine, K.; Shao, M. Revealing the closed pore formation of waste wood-derived hard carbon for advanced sodium-ion battery. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Q.; Chen, H.; Chen, X.; Zheng, J.; Que, L.; Yu, F.; Zhao, J.; Xie, Y.; Huang, M.; Lu, C.; Meng, J.; Zhang, X. Tea-Derived Sustainable Materials. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2310226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, S.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, J.; Deng, Q.; Sun, Z.; Cao, D.; Liu, T.; Amine, K.; Yang, C. Hard carbon with an opened pore structure for enhanced sodium storage performance. Energy Environ. Sci. 2024, 17, 8189–8197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izanzar, I.; Dahbi, M.; Kiso, M.; Doubaji, S.; Komaba, S.; Saadoune, I. Hard carbons issued from date palm as efficient anode materials for sodium-ion batteries. Carbon 2018, 137, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Wang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Ji, K.; Wang, C.; Ruan, D.; Xia, Y. Engineering hard carbon with high initial coulomb efficiency for practical sodium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources. 2021, 492, 229656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, R.; Fan, C.; Liu, J.; Liu, J. Anode of Anthracite Hard Carbon Hybridized by Phenolic Epoxy Resin toward Enhanced Performance for Sodium-Ion Batteries. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2024, 7, 6704–6716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, D.; Lin, Y.; Zhu, X. Sucrose-anthracite composite supplemented by KOH&HCl washing strategy for high-performance carbon anode material of sodium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources. 2025, 628, 235924. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Hu, Z.; Zhou, W.; Gao, P.; Liu, Z.; Liu, J.; Fan, C.; Liu, J. Advanced Structural Engineering Design for Tailored Microporous Structure via Adjustable Graphite Sheet Angle to Enhance Sodium-Ion Storage in Anthracite-Based Carbon Anode. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2405174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Sun, F.; Wang, H.; Wu, D.; Chao, Y.; Gao, J.; Zhao, G. Altering Thermal Transformation Pathway to Create Closed Pores in Coal-Derived Hard Carbon and Boosting of Na+ Plateau Storage for High-Performance Sodium-Ion Battery and Sodium-Ion Capacitor. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2203725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hu, Y.-S.; Qi, X.; Rong, X.; Li, H.; Huang, X.; Chen, L. Advanced sodium-ion batteries using superior low cost pyrolyzed anthracite anode: towards practical applications. Energy Storage Mater. 2016, 5, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Cui, Y.; Niu, P.; Ge, L.; Zheng, R.; Liang, S.; Xing, W. Biomass-derived hard carbon material for high-capacity sodium-ion battery anode through structure regulation. Carbon 2025, 231, 119733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Tian, X.; Qiao, Y.; Han, P. Regulation plateau capacity and initial coulombic efficiency of furfural residues-derived hard carbon via components engineering. J. Power Sources. 2025, 625, 235664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Lu, H.; Fang, Y.; Sushko, M. L.; Cao, Y.; Ai, X.; Yang, H.; Liu, J. Low-Defect and Low-Porosity Hard Carbon with High Coulombic Efficiency and High Capacity for Practical Sodium Ion Battery Anode. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1703238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Tang, Z.; Pan, Z.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, X.; Sun, D.; Tang, Y.; Dhmees, A. S.; Wang, H. Regulating closed pore structure enables significantly improved sodium storage for hard carbon pyrolyzing at relatively low temperature. SusMat 2022, 2, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Yi, Z.; Xu, R.; Chen, J.; Cheng, J.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Q.; Guo, Q.; Xie, L.; Chen, C. Towards enhanced sodium storage of hard carbon anodes: Regulating the oxygen content in precursor by low-temperature hydrogen reduction. Energy Storage Mater. 2022, 51, 620–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Cao, R.; Pu, X.; Zhao, A.; Chen, W.; Song, C.; Fang, Y.; Cao, Y. Access to advanced sodium-ion batteries by presodiation: Principles and applications. J. Energy Chem. 2024, 92, 162–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wang, R.; He, B.; Jin, J.; Gong, Y.; Wang, H. Recent advances on pre-sodiation in sodium-ion capacitors: A mini review. Electrochem Commun 2021, 129, 107090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Zhang, H.; Shu, C.; Hua, W.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Luo, J.; Tang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Tang, W. Research Progress and Perspectives on Pre-Sodiation Strategies for Sodium-Ion Batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2409628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lu, J.; Dai, W.; Cheng, X.; Zuo, J.; Lei, H.; Liu, W.; Fu, Z. On the Practicability of the Solid-State Electrochemical Pre-Sodiation Technique on Hard Carbon Anodes for Sodium-Ion Batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2403841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, K.; Zheng, J.; Zhao, Y.; Cai, X.; Liu, C.; Zhang, M.; Shen, Z. Closed-Pore Hard Carbon Nanospheres via Aldol Condensation for Sodium Storage. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2025, 8, 2785–2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zheng, J.; Lin, Y.; Liu, C.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, K.; Shen, Z. Designing Spherical Sucrose-Derived Hard Carbon Materials with Abundant Closed Pores via Amino-Aldehyde Condensation. Energy Fuels 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, W.; Cao, Q.; Liu, S.; Zhang, T.; Song, Z.; Song, C.; Weng, Z.; Jian, X.; Hu, F. Replacing “Alkyl” with “Aryl” for inducing accessible channels to closed pores as plateau-dominated sodium-ion battery anode. SusMat 2022, 2, 319–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Xie, L.; Su, F.; Yi, Z.; Guo, Q.; Chen, C.-M. New insights into the effect of hard carbons microstructure on the diffusion of sodium ions into closed pores. Chinese Chem. Lett. 2024, 35, 109266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobuhara, K.; Nakayama, H.; Nose, M.; Nakanishi, S.; Iba, H. First-principles study of alkali metal-graphite intercalation compounds. J. Power Sources. 2013, 243, 585–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Ma, R.; Zhang, Q.; Jia, X.; Lu, B. Graphite Anode for a Potassium-Ion Battery with Unprecedented Performance. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 10500–10505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Fan, X.; Ji, X.; Gao, T.; Hou, S.; Zhou, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, F.; Yang, C.; Chen, L.; Wang, C. Intercalation of Bi nanoparticles into graphite results in an ultra-fast and ultra-stable anode material for sodium-ion batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 2018, 11, 1218–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Lim, K.; Yoon, G.; Park, J.-H.; Ku, K.; Lim, H.-D.; Sung, Y.-E.; Kang, K. Exploiting Lithium–Ether Co-Intercalation in Graphite for High-Power Lithium-Ion Batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2017, 7, 1700418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komaba, S.; Hasegawa, T.; Dahbi, M.; Kubota, K. Potassium intercalation into graphite to realize high-voltage/high-power potassium-ion batteries and potassium-ion capacitors. Electrochem Commun 2015, 60, 172–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jache, B.; Adelhelm, P. Use of Graphite as a Highly Reversible Electrode with Superior Cycle Life for Sodium-Ion Batteries by Making Use of Co-Intercalation Phenomena. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 10169–10173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moriwake, H.; Kuwabara, A.; Fisher, C. A. J.; Ikuhara, Y. Why is sodium-intercalated graphite unstable? Rsc Adv. 2017, 7, 36550–36554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenchuk, O.; Adelhelm, P.; Mollenhauer, D. New insights into the origin of unstable sodium graphite intercalation compounds. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21, 19378–19390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunarathna, R.; Ranasinghe Arachchige, H.; Karunarathne, S.; Wijesinghe, W. P. S. L.; Sandaruwan, C.; Mantilaka, M. M. M. P. G.; Kannangara, Y. Y.; Abdelkader, A. M. Intercalating Graphite-Based Na-Ion Battery Anodes with Integrated Magnetite. Small Sci. 2025, 5, 2400405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohn, A. P.; Share, K.; Carter, R.; Oakes, L.; Pint, C. L. Ultrafast Solvent-Assisted Sodium Ion Intercalation into Highly Crystalline Few-Layered Graphene. Nano Lett. 2016, 16, 543–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiyama, A.; Kubota, K.; Igarashi, D.; Youn, Y.; Tateyama, Y.; Ando, H.; Gotoh, K.; Komaba, S. MgO-Template Synthesis of Extremely High Capacity Hard Carbon for Na-Ion Battery. Angew Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 5114–5120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Tian, J.; Li, P.; Fang, Y.; Fang, Y.; Liang, X.; Feng, J.; Dong, J.; Ai, X.; Yang, H.; Cao, Y. An Overall Understanding of Sodium Storage Behaviors in Hard Carbons by an “Adsorption-Intercalation/Filling” Hybrid Mechanism. Adv. Energy Mater. 2022, 12, 2200886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, N.; Guan, Z.; Liu, Y.; Cao, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Liu, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, P.; Xu, B. Extended “Adsorption–Insertion” Model: A New Insight into the Sodium Storage Mechanism of Hard Carbons, Adv. Energy Mater. 2019, 1901351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, M.; Zheng, L.; Gong, Y.; Zhang, R.; Wu, F.; Wu, C.; Bai, Y. Unlocking the local structure of hard carbon to grasp sodium-ion diffusion behavior for advanced sodium-ion batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 2024, 17, 1387–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Johnson, I.; Lu, Z.; Kudo, A.; Chen, M. Effect of Local Atomic Structure on Sodium Ion Storage in Hard Amorphous Carbon. Nano Lett. 2021, 21, 6504–6510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zheng, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, K.; Fu, W.; Wang, G.; Wang, H.; Hao, Y.; Lin, Z.; Cao, X.; Liu, J.; Zhang, M.; Shen, Z. ; Designing hard carbon microsphere structure via halogenation amination and oxidative polymerization reactions for sodium ion insertion mechanism investigation. J. Colloid Interf. Sci. 2024, 668, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Jiang, D.; Fu, Z.; Zhou, J.; Liu, R.; Zhang, R.; Sun, D.; Dhmees, A. S.; Tang, Y.; Wang, H. Regulating Pseudo-Graphitic Domain and Closed Pores to Facilitate Plateau Sodium Storage Capacity and Kinetics for Hard Carbon. Small Methods 2024, 8, 2400509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Chen, L.; Wei, J.; Diao, C.; Li, F.; Du, C.; Bai, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Malyi, O. I.; Chen, X.; Tang, Y.; Bao, X. Pushing slope-to plateau-type behavior in hard carbon for sodium-ion batteries via local structure rearrangement. Energy Environ. Sci. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Zhang, G.; Xu, C.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, B.; Wang, A.; Sun, K. Tailored Regulation of Graphite Microcrystals via Tandem Catalytic Carbonization for Enhanced Electrochemical Performance of Hard Carbon in the Low-Voltage Plateau. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2416061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Wang, F.; Cheng, Y.; Chen, M.; Hou, J.; Yang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, W.; Liu, G.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Li, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, J. Identifying the importance of functionalization evolution during pre-oxidation treatment in producing economical asphalt-derived hard carbon for Na-ion batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 2024, 73, 103808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Xu, Z.; Lin, P.; Zhong, Y.; Wang, X.; Yuan, Y.; Tu, J. Oxygen-Crosslinker Effect on the Electrochemical Characteristics of Asphalt-Based Hard Carbon Anodes for Sodium-Ion Batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2025, 15, 2403084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, L. K.; Antonio, E. N.; Martinez, T. D.; Zhang, L.; Zhuo, Z.; Weigand, S. J.; Guo, J.; Toney, M. F. Revealing the Sodium Storage Mechanisms in Hard Carbon Pores, Adv. Energy Mater. 2023, 13, 2302171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, C.; Li, A.; Qiu, D.; Wu, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, J.; Yuan, R.; Jiang, Z.; Liu, X.; Chen, X.; Song, H. ; One-Step Construction of Closed Pores Enabling High Plateau Capacity Hard Carbon Anodes for Sodium-Ion Batteries: Closed-Pore Formation and Energy Storage Mechanisms. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 11941–11954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Vasileiadis, A.; Zhou, Q.; Lu, Y.; Meng, Q.; Li, Y.; Ombrini, P.; Zhao, J.; Chen, Z.; Niu, Y.; Qi, X.; Xie, F.; van der Jagt, R.; Ganapathy, S.; Titirici, M.-M.; Li, H.; Chen, L.; Wagemaker, M.; Hu, Y.-S. Origin of fast charging in hard carbon anodes. Nat. Energy 2024, 9, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Zhao, L.; Sun, P.; Zhao, K.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Z.; Ma, Z.; Zheng, F.; Yang, Y.; Lu, C.; Peng, C.; Xu, C.; Xiao, Z.; Ma, X. Rationally Regulating Closed Pore Structures by Pitch Coating to Boost Sodium Storage Performance of Hard Carbon in Low-voltage Platforms. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2403642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yi, Z.; Xie, L.; Mao, Y.; Ji, W.; Liu, Z.; Wei, X.; Su, F.; Chen, C.-M. Releasing Free Radicals in Precursor Triggers the Formation of Closed Pores in Hard Carbon for Sodium-Ion Batteries. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2401249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Shi, P.; Wang, H.; Meng, Q.; Qi, X.; Ai, G.; Xie, F.; Rong, X.; Xiong, Y.; Lu, Y.; Hu, Y.-S. Unlocking plateau capacity with versatile precursor crosslinking for carbon anodes in Na-ion batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 2024, 70, 103543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, D. A.; Dahn, J. R. An In Situ Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering Study of Sodium Insertion into a Nanoporous Carbon Anode Material within an Operating Electrochemical Cell. J. Electrochem Soc. 2000, 147, 4428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Xiao, L.; Sushko, M. L.; Wang, W.; Schwenzer, B.; Xiao, J.; Nie, Z.; Saraf, L. V.; Yang, Z.; Liu, J. Sodium ion insertion in hollow carbon nanowires for battery applications. Nano Lett. 2012, 12, 3783–3787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Hu, M.; Zhang, H.; Yang, W.; Lv, R. Pore structure regulation of hard carbon: Towards fast and high-capacity sodium-ion storage. J. Colloid Interf. Sci. 2020, 566, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Sawut, N.; Chen, K.; Li, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Yang, M.; Tang, G.; Ai, X.; Yang, H.; Fang, Y.; Cao, Y. Filling carbon: a microstructure-engineered hard carbon for efficient alkali metal ion storage. Energy Environ. Sci. 2023, 16, 4041–4053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.-Y.; Liu, H.-H.; Cao, J.-M.; Yang, J.-L.; Su, M.-Y.; Wang, X.-Y.; Gu, Z.-Y.; Wang, J.; Li, B.; Wang, Y.; Wu, X.-L. Microstructure reconstruction via confined carbonization achieves highly available sodium ion diffusion channels in hard carbon. Energy Storage Mater. 2024, 73, 103839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.-R.; Yi, Z.-L.; Su, F.-Y.; Xie, L.-J.; Zhang, X.-F.; Li, X.-F.; Cheng, J.-Y.; Chen, J.-P.; Chen, C.-M. , Regulating the Pore Structure of Activated Carbon by Pitch for High-Performance Sodium-Ion Storage. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 17553–17562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Vasileiadis, A.; Zhou, Q.; Lu, Y.; Meng, Q.; Li, Y.; Ombrini, P.; Zhao, J.; Chen, Z.; Niu, Y.; Qi, X.; Xie, F.; Jagt, R. van der; Ganapathy, S.; Titirici, M.-M.; Li, H.; Chen, L.; Wagemaker, M.; Hu, Y.-S. ; Origin of fast charging in hard carbon anodes, Nat. Energy 2024, 9, 134–142. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; You, Y.; Huang, L.; Zheng, Q.; Sun, Z.; Fang, K.; Sha, L.; Liu, M.; Zhan, X.; Zhao, J.; Han, Y.-C.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, Y.; Wu, S.; Zhang, L. Precisely Tunable Instantaneous Carbon Rearrangement Enables Low-Working-Potential Hard Carbon Toward Sodium-Ion Batteries with Enhanced Energy Density. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2407369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).