Submitted:

13 April 2025

Posted:

15 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Crowd Density and Movement Analysis

2.1. Panic Behavior Detection

3. Methodology

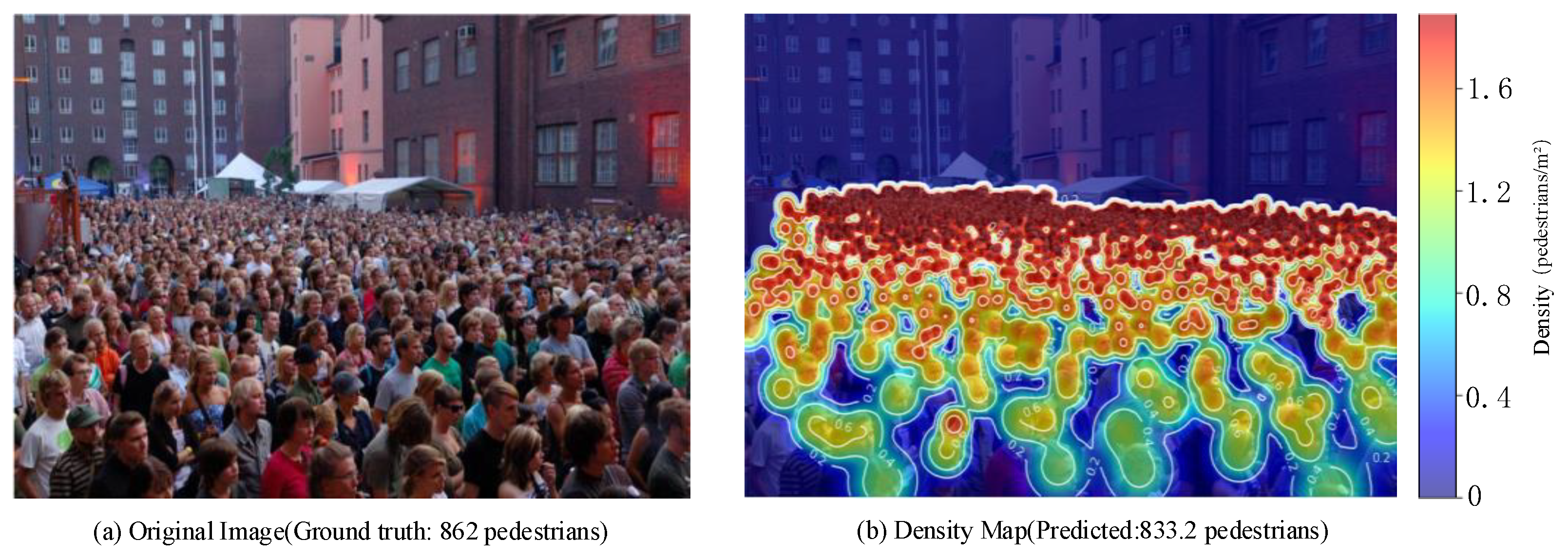

3.1. Crowd Density Measures Panic Risk

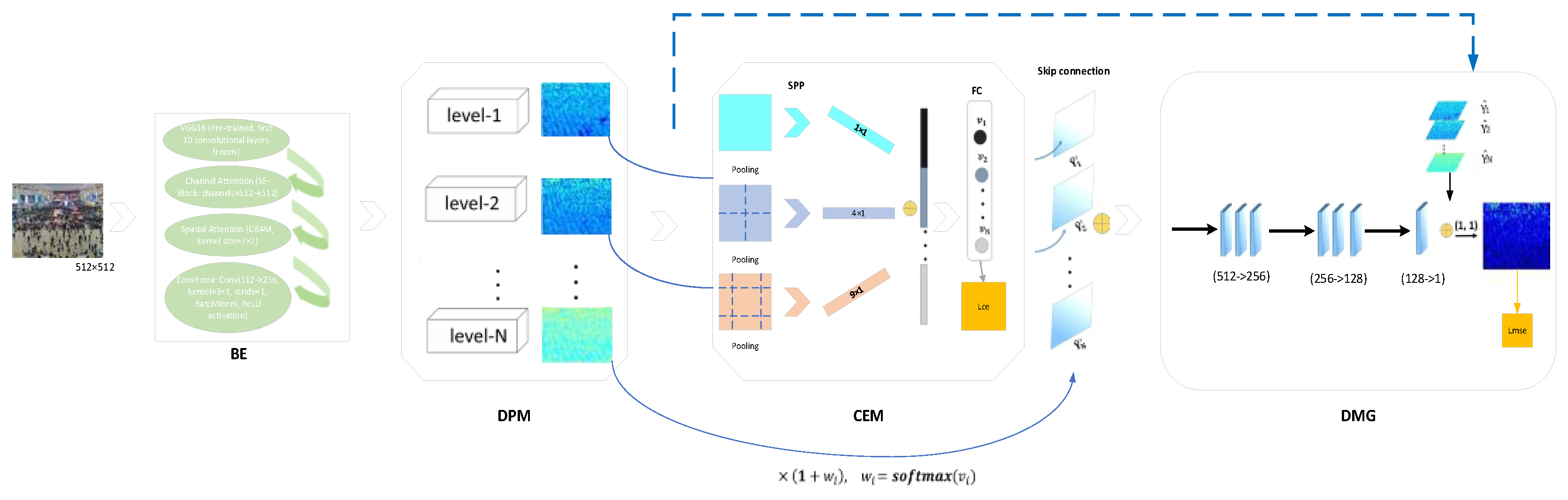

3.1.1. CDNet Framework

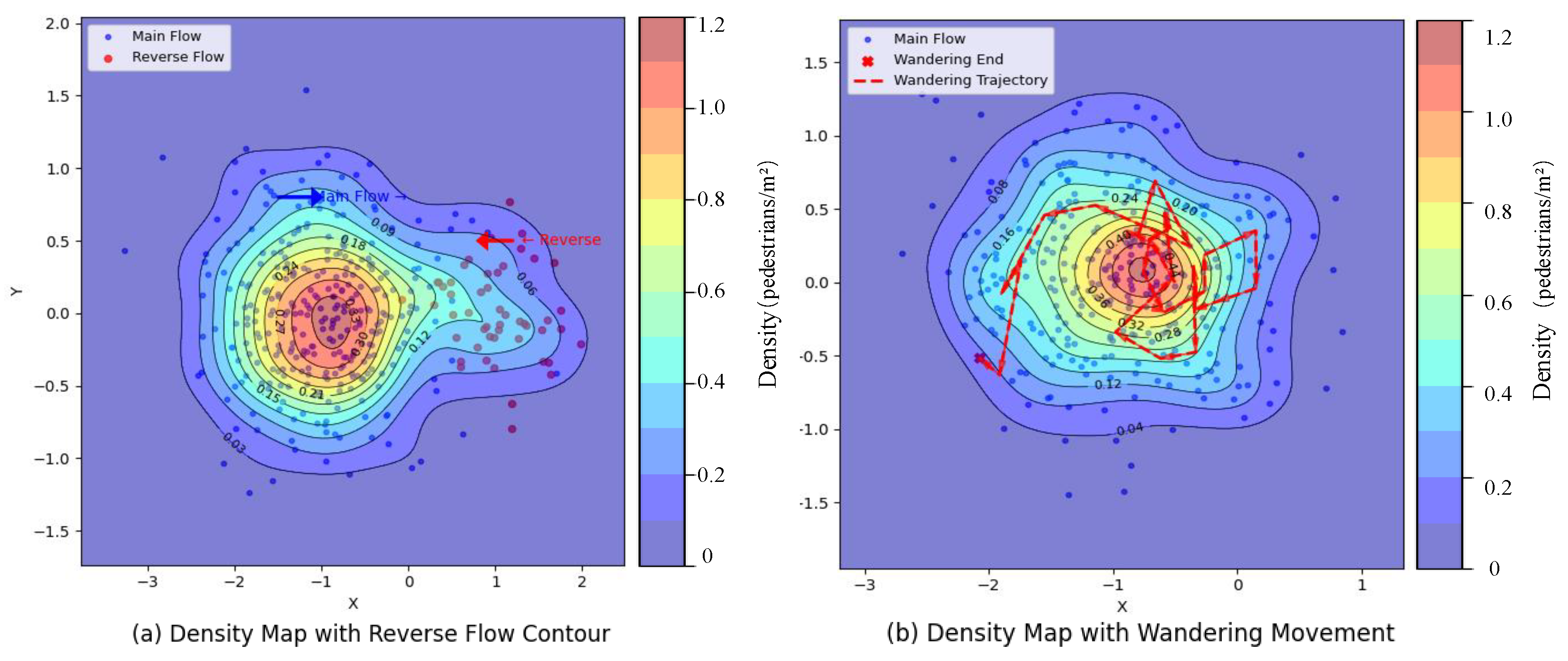

3.1.2. Abnormal Change of Contour Line

- Mathematical Description of Contour Features.

- 2.

- Evaluation Rules of contour line.

3.2. Panic Trajectory Recognition Criterion

3.2.1. Countercurrent Trajectory Criterion

3.2.2. Nonlinear Motion Trajectory Criterion

3.3. Panic Semantic Recognition Criterion

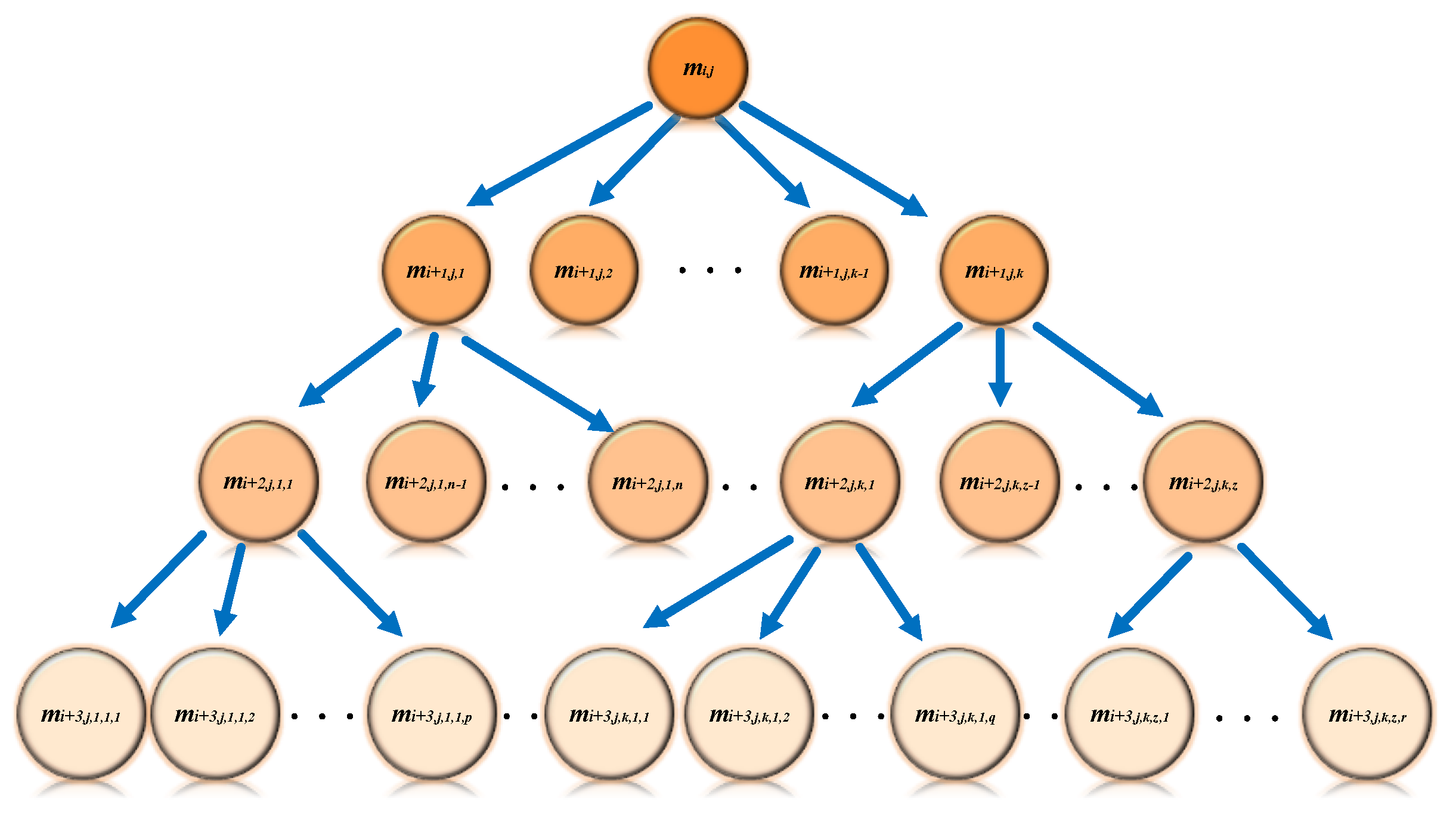

3.4. Fusion-Based Multi-Feature Method for Pedestrian Panic Recognition

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Setup

4.1. Case Analysis

4.1. Evaluation Metrics

4.1.1. Performance Metrics

4.3.2. Ablation Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yanghui H, Yubo B, Xiangxia R, Shenshi H, Wei G. Experimental study on the impact of a stationary pedestrian obstacle at the exit on evacuation. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications. 2023.

- Ahmed BA, Habib U. Panic Detection in Crowded Scenes. Engineering, Technology & Applied Science Research. 2020.

- Melissa De I, Edoardo B, Marco D, Gian Paolo C, Bottino A. Large scale simulation of pedestrian seismic evacuation including panic behavior. Sustainable Cities and Society. 2023.

- Altamimi A, Ullah H. Panic Detection in Crowded Scenes. Engineering, Technology & Applied Science Research. 2020;10:5412-8.

- Deepak Kumar J, Xudong Z, Germán G-A, Chenquan G, Ketan K. Multimodal pedestrian detection using metaheuristics with deep convolutional neural network in crowded scenes. Information Fusion. 2023.

- Antonio, L. Pedestrian Detection Systems. Wiley Encyclopedia of Electrical and Electronics Engineering. 2018.

- Ganga B, Lata B, Venugopal K. Object detection and crowd analysis using deep learning techniques: Comprehensive review and future directions. Neurocomputing. 2024:127932.

- Hamid, A.A.; Monadjemi, S.A.; Shoushtarian, B. ABDviaMSIFAT: Abnormal Crowd Behavior Detection utilizing a Multi-Source Information Fusion Technique. IEEE Access 2024, PP, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazaridis, L.; Dimou, A.; Daras, P. Abnormal Behavior Detection in Crowded Scenes Using Density Heatmaps and Optical Flow. 2018 26th European Signal Processing Conference (EUSIPCO). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, ItalyDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 2060–2064.

- Sharma, V.K.; Mir, R.N.; Singh, C. Scale-aware CNN for crowd density estimation and crowd behavior analysis. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2023, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Shen, W.; Zeng, D.; Zhang, Z. Unusual event detection in crowded scenes by trajectory analysis. ICASSP 2015 - 2015 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, AustraliaDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 1300–1304.

- Miao, Y.; Yang, J.; Alzahrani, B.; Lv, G.; Alafif, T.; Barnawi, A.; Chen, M. Abnormal Behavior Learning Based on Edge Computing toward a Crowd Monitoring System. IEEE Netw. 2022, 36, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, B.; Nigam, S.; Singh, R. A Review of Deep Learning Techniques for Crowd Behavior Analysis. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2022, 29, 5427–5455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baidu AI Open Platform. Available online: https://ai.baidu.com/ (accessed on 11 November 2020).

- Muhammad Asif K, Hamid M, Ridha H. LCDnet: a lightweight crowd density estimation model for real-time video surveillance. Journal of Real-time Image Processing. 2023.

- Luo, L.; Xie, S.; Yin, H.; Peng, C.; Ong, Y.-S. Detecting and Quantifying Crowd-Level Abnormal Behaviors in Crowd Events. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2024, 19, 6810–6823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alashban, A.; Alsadan, A.; Alhussainan, N.F.; Ouni, R. Single Convolutional Neural Network With Three Layers Model for Crowd Density Estimation. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 63823–63833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Wang, Y.; Jia, P.; Zhu, W.; Li, C.; Ma, Y.; Li, M. Abnormal Behavior Detection Based on Dynamic Pedestrian Centroid Model: Case Study on U-Turn and Fall-Down. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 8066–8078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korbmacher, R.; Dang, H.-T.; Tordeux, A. Predicting pedestrian trajectories at different densities: A multi-criteria empirical analysis. Phys. A: Stat. Mech. its Appl. 2023, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.-Z.T.; Xu, J.; Zhu, B.; Tang, T.-Q.; Lo, S.; Zhang, B.; Tian, Y. Advancing crowd forecasting with graphs across microscopic trajectory to macroscopic dynamics. Inf. Fusion 2024, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A.; Rajakumaran, G.; Mahdal, M.; Usharani, S.; Rajasekharan, V.; Vincent, R.; Sugavanan, K. Live Event Detection for People’s Safety Using NLP and Deep Learning. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 6455–6472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li N HY, Huang ZQ. Implementation of a Real-time Fall Detection Algorithm Based on Body's Acceleration [Article in Chinese]. Journal of Chinese Computer Systems. 2012;33(11):2410-3.

- Pan, D.; Liu, H.; Qu, D.; Zhang, Z. Human Falling Detection Algorithm Based on Multisensor Data Fusion with SVM. Mob. Inf. Syst. 2020, 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing L, Qingwang H, Yingjun D, Xiantong Z, Shengyong C, Ling S. Variational Abnormal Behavior Detection With Motion Consistency. IEEE transactions on image processing. 2022.

- Shuqiang G, Qianlong B, Song G, Yaoyao Z, Ai-Quan L. An Analysis Method of Crowd Abnormal Behavior for Video Service Robot. IEEE Access. 2019.

- FZ, H. Research on evacuation of people in panic state considering rush behavior [Article in Chinese]. Journal of Safety Science and Technology. 2022;18(10):203-9.

- S, Z. Panic Crowd Behavior Detection Based on Intersection Density of Motion Vector [Article in Chinese]. Computer Systems & Applications. 2017;26(07):210-4.

- Chang, C.-W.; Lin, Y.-Y. A hybrid CNN and LSTM-based deep learning model for abnormal behavior detection. Multimedia Tools Appl. 2022, 81, 11825–11843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiefan Q, Xing-Gang Y, Wei W, Wei W, Kai F. Skeleton-Based Abnormal Behavior Detection Using Secure Partitioned Convolutional Neural Network Model. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics. 2022.

- Vinothina V, George A, editors. Recognizing Abnormal Behavior in Heterogeneous Crowd using Two Stream CNN. 2024 Asia Pacific Conference on Innovation in Technology (APCIT); 2024: IEEE.

- Zhang Y, Zhou D, Chen S, Gao S, Ma Y, editors. Single-Image Crowd Counting via Multi-Column Convolutional Neural Network. 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016 27-. 30 June.

- Kyoo-Man, H. Reviewing the Itaewon Halloween crowd crush, Korea 2022: Qualitative content analysis. F1000Research. 2023.

- Haroon I, Muhmmad T, Kishan A, Dong Z, Somaya AM, Nasir R, Mubarak S. Composition Loss for Counting, Density Map Estimation and Localization in Dense Crowds. arXiv (Cornell University). 2018.

| NO. | Reference | Method | Data Source | Feature | Susceptible factor |

| 1 | Zhao, R.Y.et al.[18] | Open pose, dynamic centroid model | Experiment Volunteers, a set of falling activity records | Acceleration, mass inertial of human body subsegments, and internal constraints | Simple group behavior patterns |

| 2 | Li N.et al.[22] | Decision tree classifier | Experiment Volunteers, a set of falling activity records | Acceleration, tilting angle, and still time | Environment |

| 3 | D. Pan et al.[23] | Multisensory data fusion with Support Vector Machine (SVM) | Experiments of 100 Volunteers | Acceleration | Multi-noise or multi-source environments |

| 4 | J. Li et al.[24] | Variational abnormal behavior detection (VABD) | UCSD, CUHK, Corridor, ShanghaiTech | Motion consistency | Sensitivity |

| 5 | S. Guo et al.[25] | Improved k-means | UMN | Velocity vector | Sensitivity |

| 6 | Huo, F.Z et al.[26] | Simulation | / | Move probability | Sensitivity |

| 7 | Zhong, S et al.[27] | LK optical flow method | UMN | Intersection density | Environment |

| 8 | CW et al.[28] | CNN and LSTM | Fall Detection Dataset | Fall, down | Real-time |

| 9 | Qiu. J.F. et al.[29] | Partitioned Convolutional Neural Network | / | Cognitive impairment | Simple group behavior patterns |

| 10 | Vin V et al.[30] | Two-stream CNN | Avenue Dataset | Racing, tossing objects, and loitering | False positives |

| NO. | Event type | Key word | Turnout | Weight | NO. | Event type | Key word | Turnout | Weight | |||||||||

| 1 | Medical accident | Murder | 152 | 0.51 | 2 | Stampede | Let me out | 13 | 0.04 | |||||||||

| 3 | Medical accident | Stabbing | 76 | 0.25 | 4 | Stampede | Don't push me | 32 | 0.11 | |||||||||

| 5 | Medical accident | Help | 21 | 0.07 | 6 | Stampede | Someone fell | 57 | 0.19 | |||||||||

| 7 | Medical accident | Pay with your life | 38 | 0.13 | 8 | Stampede | Trampled to death | 73 | 0.24 | |||||||||

| 9 | Medical accident | Black-hearted | 2 | 0.01 | 10 | Stampede | Crushed to death | 53 | 0.18 | |||||||||

| 11 | Medical accident | Disregard for human life | 7 | 0.02 | 12 | Stampede | Can't breathe | 50 | 0.17 | |||||||||

| 13 | Medical accident | Misdiagnosis | 4 | 0.01 | 14 | Stampede | Help | 22 | 0.07 | |||||||||

| 15 | Disaster event | Landslide | 32 | 0.11 | 16 | Terrorist attack | Kidnapping | 42 | 0.14 | |||||||||

| 17 | Disaster event | Earthquake | 57 | 0.19 | 18 | Terrorist attack | Explosion | 36 | 0.12 | |||||||||

| 19 | Disaster event | Fire | 28 | 0.09 | 20 | Terrorist attack | Bomb | 48 | 0.16 | |||||||||

| 21 | Disaster event | Mudslide | 23 | 0.08 | 22 | Terrorist attack | Gun | 47 | 0.16 | |||||||||

| 23 | Disaster event | Flood | 45 | 0.15 | 24 | Terrorist attack | Poison gas | 35 | 0.11 | |||||||||

| 25 | Disaster event | Tornado | 42 | 0.14 | 26 | Terrorist attack | Dead body | 26 | 0.09 | |||||||||

| 27 | Disaster event | Tsunami | 73 | 0.24 | 28 | Terrorist attack | Murder | 66 | 0.22 | |||||||||

| Dataset | Videos | Density(pedestrians/) | Panic Events |

| Stampede in Itaewon | 30 | 8.7 | 47 |

| UCF Crowd | 150 | 2.8 | 24 |

| Simulated Data | 160 | 4.0 | 15 |

| Model Configuration |

Accuracy (%) |

F1-score (%) |

Inference Speed (FPS) |

| Density-Only | 74.5 | 76.3 | 50 |

| Trajectory-Only | 77.2 | 79.1 | 48 |

| Semantic-Only | 72.8 | 74.9 | 53 |

| Density + Trajectory | 81.6 | 83.4 | 45 |

| Density + Semantic | 78.9 | 80.7 | 47 |

| Trajectory + Semantic | 76.5 | 78.2 | 49 |

| Full Model | 91.7 | 88.2 | 40 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).