1. Introduction

Heart failure (HF) remains a leading cause of global morbidity and mortality, characterized by complex pathophysiological mechanisms, including impaired cardiac output, neurohormonal activation, systemic congestion, and endothelial dysfunction [

1,

2,

3]. Despite advances in pharmacological and device-based therapies, HF continues to present substantial diagnostic and therapeutic challenges, particularly due to the heterogeneous nature of the syndrome and its overlapping clinical presentations [

4].

One of the most significant contributors to HF progression and symptom burden is hemodynamic congestion. Congestion, resulting from elevated intracardiac filling pressures and impaired fluid redistribution, manifests as pulmonary and peripheral edema, ascites, jugular venous distention, and hepatic congestion [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Its presence is not only associated with acute decompensation but is also a major predictor of rehospitalization and adverse outcomes in both acute and chronic HF [

1,

2,

5]. However, traditional clinical assessment of congestion is often subjective and imprecise, highlighting the critical need for more reliable and dynamic biomarkers [

4].

In this context, endothelial dysfunction has emerged as a pivotal link between hemodynamic stress and clinical deterioration in HF [

11,

12,

13,

14]. The vascular endothelium plays a central role in maintaining vascular tone, permeability, and immune regulation. Disruption of endothelial homeostasis leads to increased vascular permeability, inflammation, and tissue edema, hallmarks of advanced HF [

14,

15]. Biomarkers that capture this vascular component could significantly enhance our ability to diagnose, stratify, and monitor patients with HF more effectively [

1,

16,

17].

CD146, also known as the melanoma cell adhesion molecule (MCAM), is a transmembrane glycoprotein predominantly expressed on endothelial cells, where it functions in cell adhesion, angiogenesis, and the regulation of vascular permeability [

1,

18,

19]. Its soluble form (sCD146), released into the bloodstream under conditions of endothelial stress, has garnered attention as a potential biomarker of systemic congestion and endothelial injury in HF [

1,

20].

2. CD146: Structure, Expression, and Regulation

CD146 was originally identified in 1987 on the surface of melanoma cells. Since then, its physiological relevance has been substantially redefined, with emerging roles in vascular biology, immune modulation, and tissue remodeling. Now considered a critical adhesion molecule of the endothelial junction, CD146 is deeply involved in maintaining vascular integrity, regulating immune cell trafficking, and responding to environmental stressors such as inflammation and mechanical stretch [

16,

20,

21].

2.1. Molecular Structure

Encoded on chromosome 11q23.3 in humans, the CD146 gene spans 16 exons and encodes a 113-kDa transmembrane glycoprotein belonging to the immunoglobulin superfamily, involved in cell adhesion and endothelial signaling [

22,

23]. The mature CD146 protein comprises an N-terminal signal peptide, a large extracellular domain with five immunoglobulin (Ig)-like domains, eight predicted N-glycosylation sites, a 24-amino-acid hydrophobic transmembrane region, and a short cytoplasmic tail that mediates intracellular signaling. These domains work synergistically to mediate cell–cell adhesion, endothelial cohesion, and downstream signaling cascades involved in cell proliferation, migration, and vascular remodeling [

22,

24].

The Ig-like domains within the extracellular region of CD146 facilitate both homophilic CD146–CD146 interactions and heterophilic binding with other adhesion molecules, thereby contributing to endothelial cell–cell cohesion and vascular barrier integrity. Glycosylation motifs support proper protein folding, receptor–ligand interactions, and membrane localization, while the cytoplasmic tail engages intracellular signaling cascades that regulate endothelial responses to inflammatory stimuli and vascular injury [

24].

2.2. Expression Profile

CD146 is predominantly expressed on vascular endothelial cells, particularly at intercellular junctions in both arteries and veins, where it supports endothelial barrier integrity and regulates permeability [

1,

16,

25]. Beyond the endothelium, CD146 is also expressed in vascular smooth muscle cells, where it contributes to vessel remodeling, and in pericytes, which support microvascular stability [

26,

27,

28]. In addition to its vascular localization, CD146 expression has been detected in a variety of extra-vascular tissues, including mesenchymal stromal cells within the bone marrow, trophoblasts in the placenta, and subsets of immune cells such as T cells, B cells, and natural killer (NK) cells. This broad expression profile highlights the multifunctional nature of CD146, encompassing roles in vascular biology, immune surveillance, and tissue regeneration [

23,

29].

2.3. Isoforms of CD146

Three major isoforms of CD146 have been described: the long form (lgCD146), the short form (shCD146), and the soluble form (sCD146) [

23]. The lgCD146 isoform is localized primarily at the intercellular junctions of endothelial cells and is critical for maintaining cell–cell adhesion and the integrity of the endothelial barrier. In contrast, shCD146 is localized apically on endothelial surfaces and is implicated in dynamic processes such as endothelial proliferation, migration, and wound healing [

23].

The third isoform, soluble CD146 (sCD146), is of particular interest in clinical cardiology [

1,

20,

30,

31]. Soluble CD146 (sCD146) is generated through proteolytic cleavage of its membrane-bound form, predominantly mediated by matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), especially MMP-2 and MMP-9. This shedding process is typically induced by pro-inflammatory cytokines or mechanical endothelial stretch, leading to elevated circulating levels of sCD146 in various pathological conditions, including heart failure, systemic inflammation, and certain malignancies [

23,

32]. While sCD146 levels in healthy individuals range between 200 and 400 ng/mL, this reference interval is not yet universally standardized and may be influenced by population demographics, assay specificity, and clinical status [

23,

33].

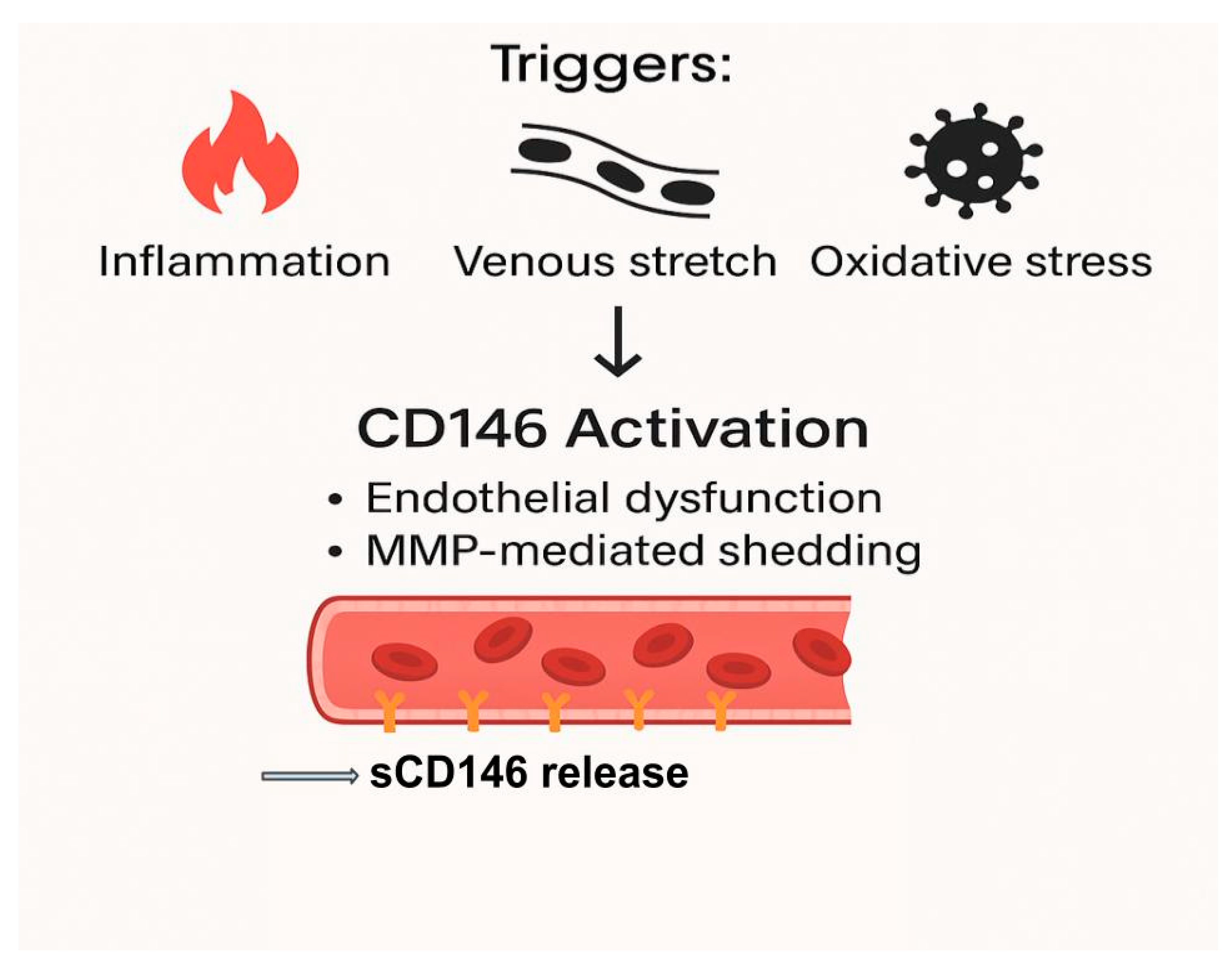

2.4. Regulation of CD146 Expression and Shedding

CD146 expression and its conversion to a soluble form are regulated by a complex interplay of transcriptional and post-translational mechanisms. Pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) are potent inducers of CD146 gene transcription and promote the activation of metalloproteinases that mediate ectodomain shedding [

23]. Oxidative stress, primarily mediated by reactive oxygen species (ROS), contributes to the destabilization of endothelial junctions and promotes the proteolytic shedding of CD146, thereby increasing circulating sCD146 levels in conditions characterized by endothelial dysfunction [

19].

In the context of heart failure, elevated intracardiac and venous pressures result in a mechanical stretch of endothelial cells, a powerful stimulus for CD146 shedding [

23]. Additional factors such as hypoxia, ischemia–reperfusion injury, and oxidized low-density lipoprotein (oxLDL) may synergistically enhance both transcriptional upregulation and post-translational modifications of CD146. Collectively, these regulatory mechanisms underscore the dynamic sensitivity of CD146 expression to diverse pathological stimuli, reinforcing the utility of circulating sCD146 as a biomarker of vascular stress and systemic congestion, as illustrated in

Figure 1 [

19,

32]

.

3. Pathophysiological Role of CD146 in Heart Failure: Mechanisms and Vascular Implications

Heart failure (HF) is not solely a disorder of impaired myocardial function but also a disease of profound vascular involvement. Central to this vascular dysfunction is the activation and shedding of endothelial markers, among which CD146, particularly its soluble form (sCD146), has emerged as both a consequence and indicator of systemic congestion and endothelial barrier disruption [

16,

20,

30]. The release of sCD146 is governed by a complex interplay of hemodynamic, inflammatory, oxidative, and hypoxic stimuli that reflect the severity of vascular involvement in HF. Beyond being a passive biomarker, CD146 may also actively contribute to the pathological cascade that perpetuates vascular permeability and congestion [

20,

21,

23].

3.1. Hemodynamic Stress and Endothelial Activation

Elevated central venous and intracardiac pressures are hallmark features of both acute and chronic HF [

1,

20,

21,

34]. Hemodynamic overload imposes increased mechanical tension on the vascular endothelium, particularly within the highly compliant venous system. Sustained intravascular pressure disrupts endothelial junctional integrity, leading to heightened vascular permeability and facilitating plasma extravasation into the interstitial space. Clinically, this process manifests as peripheral edema, ascites, or pleural effusion, hallmarks of systemic and pulmonary congestion in advanced heart failure [

1,

4].

CD146 is constitutively expressed at the intercellular junctions of endothelial cells, where it contributes to vascular cohesion and barrier integrity. In response to pathological hemodynamic stress, such as venous stretch or elevated arterial afterload, mechanical forces activate matrix metalloproteinases, particularly MMP-2 and MMP-9, which cleave membrane-bound CD146. This proteolytic event releases its extracellular domain into the circulation as soluble CD146 (sCD146), reflecting endothelial perturbation and vascular stress. This release serves as a quantitative marker of endothelial stress, correlating with the degree of vascular strain and systemic congestion [

18,

23,

25].

3.2. Inflammatory Cytokines and Oxidative Stress

Inflammation plays a pivotal role in both the initiation and perpetuation of HF pathophysiology. Circulating cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and TGF-β not only contribute to myocardial dysfunction but also trigger endothelial activation, enhance CD146 gene expression, and promote its shedding [

7,

19,

35].

Moreover, the oxidative stress environment in HF, marked by an imbalance between reactive oxygen species (ROS) and antioxidant defenses, directly impairs endothelial integrity and further stimulates MMP activity, potentiating sCD146 release. These inflammatory and oxidative stimuli interact synergistically with mechanical stressors to amplify endothelial injury, linking systemic inflammation to the vascular features of HF [

16,

19,

23,

27].

3.3. CD146 and Endothelial Dysfunction: Amplifying Congestion

Once released, sCD146 not only reflects endothelial stress but may also contribute to its progression. Soluble CD146 (sCD146) can exert paracrine and autocrine effects, promoting endothelial hyperpermeability, enhancing leukocyte transmigration across the endothelium, and amplifying local inflammatory responses. These actions further compromise vascular integrity and contribute to the progression of inflammatory and cardiovascular disorders [

23,

32]. This creates a self-sustaining feedback loop: mechanical and inflammatory stressors release sCD146, which in turn worsens endothelial dysfunction and congestion [

23,

32].

4. Clinical Relevance and Diagnostic Studies

In the evolving landscape of heart failure (HF) diagnosis, the search for biomarkers that reflect not only myocardial strain but also vascular dysfunction and congestion remains a priority [

25]. Soluble CD146 (sCD146), a product of endothelial stress and activation, has emerged as a clinically relevant biomarker that complements traditional cardiac-derived indicators. Unlike natriuretic peptides, which primarily capture myocardial wall stretch, sCD146 reflects endothelial barrier disruption and systemic venous congestion, dimensions central to the pathophysiology of both acute and chronic HF [

1,

31].

4.1. Diagnostic Value in Acute and Chronic Heart Failure

Several key studies have underscored the diagnostic utility of sCD146 in the setting of acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF). One of the most comprehensive was conducted by Gayat et al.. involving a multicenter cohort of patients admitted with ADHF. The study demonstrated that sCD146 concentrations were significantly elevated in patients with clinical and radiographic signs of congestion, independent of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). Notably, sCD146 showed a diagnostic performance comparable to NT-proBNP, and the combination of both biomarkers provided enhanced sensitivity and specificity in identifying volume overload [

20].

These findings were particularly relevant for patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), a group in which the diagnosis is often complicated by inconclusive natriuretic peptide levels. Because sCD146 is independent of systolic function and more reflective of vascular and endothelial strain, it has been proposed as a valuable adjunct biomarker, especially in those with ambiguous or non-specific presentations [

20].

Table 1.

Clinical Applications of sCD146 in Heart Failure.

Table 1.

Clinical Applications of sCD146 in Heart Failure.

| Application |

Details |

| Diagnostic Utility |

Elevated sCD146 levels are associated with systemic and pulmonary congestion, reflecting endothelial dysfunction and vascular strain. It complements traditional biomarkers like NT-proBNP in diagnosing HF. |

| Prognostic Value |

High sCD146 levels predict adverse outcomes, including rehospitalization, disease progression, and mortality. It provides independent prognostic information, especially in conjunction with other biomarkers. |

| Monitoring Therapy |

Serial measurements of sCD146 can be used to monitor treatment response, especially in decongestive therapy. Reductions in sCD146 levels may indicate effective decongestion and improved endothelial function. |

| Utility in HF with Preserved Ejection Fraction (HFpEF) |

sCD146 is valuable in diagnosing and monitoring HFpEF, where traditional markers like NT-proBNP may be less reliable. |

| Identification of Subclinical Congestion |

Persistent elevation of sCD146 levels may indicate residual congestion even after apparent clinical improvement, identifying patients at risk for relapse. |

4.2. Associations with Imaging and Hemodynamic Parameters

The credibility of sCD146 as a congestion marker is further supported by its correlation with objective hemodynamic and imaging parameters. In a study by Kuběna et al. (2016), elevated sCD146 levels were significantly associated with radiographic signs of pulmonary congestion (e.g., alveolar edema, pleural effusion) in patients with acute coronary syndromes, independent of myocardial injury as assessed by troponin levels. This highlighted the vascular-specific signal of sCD146, distinguishing it from cardiac necrosis markers [

31].

Similarly, Van Aelst et al. (2017) observed that sCD146 correlated strongly with echocardiographic markers of systemic congestion, including right atrial enlargement, increased inferior vena cava (IVC) diameter, reduced IVC collapsibility, elevated E/e′ ratio, and increased systolic pulmonary artery pressure (sPAP) [

36]. These relationships validate sCD146 as a surrogate marker of right-sided and pulmonary venous congestion, with relevance for bedside clinical evaluation, especially when echocardiographic assessment is limited or inconclusive [

36].

Elevated sCD146 levels have been strongly associated with radiographic signs of pulmonary congestion, enlarged right atrial size, inferior vena cava dilation, elevated pulmonary artery pressures, and subclinical congestion, even in patients who appear clinically euvolemic [

1,

20,

34,

37]. These correlations confirm the role of sCD146 as a biologically plausible, noninvasive marker of congestion severity that reflects real-time endothelial derangement.

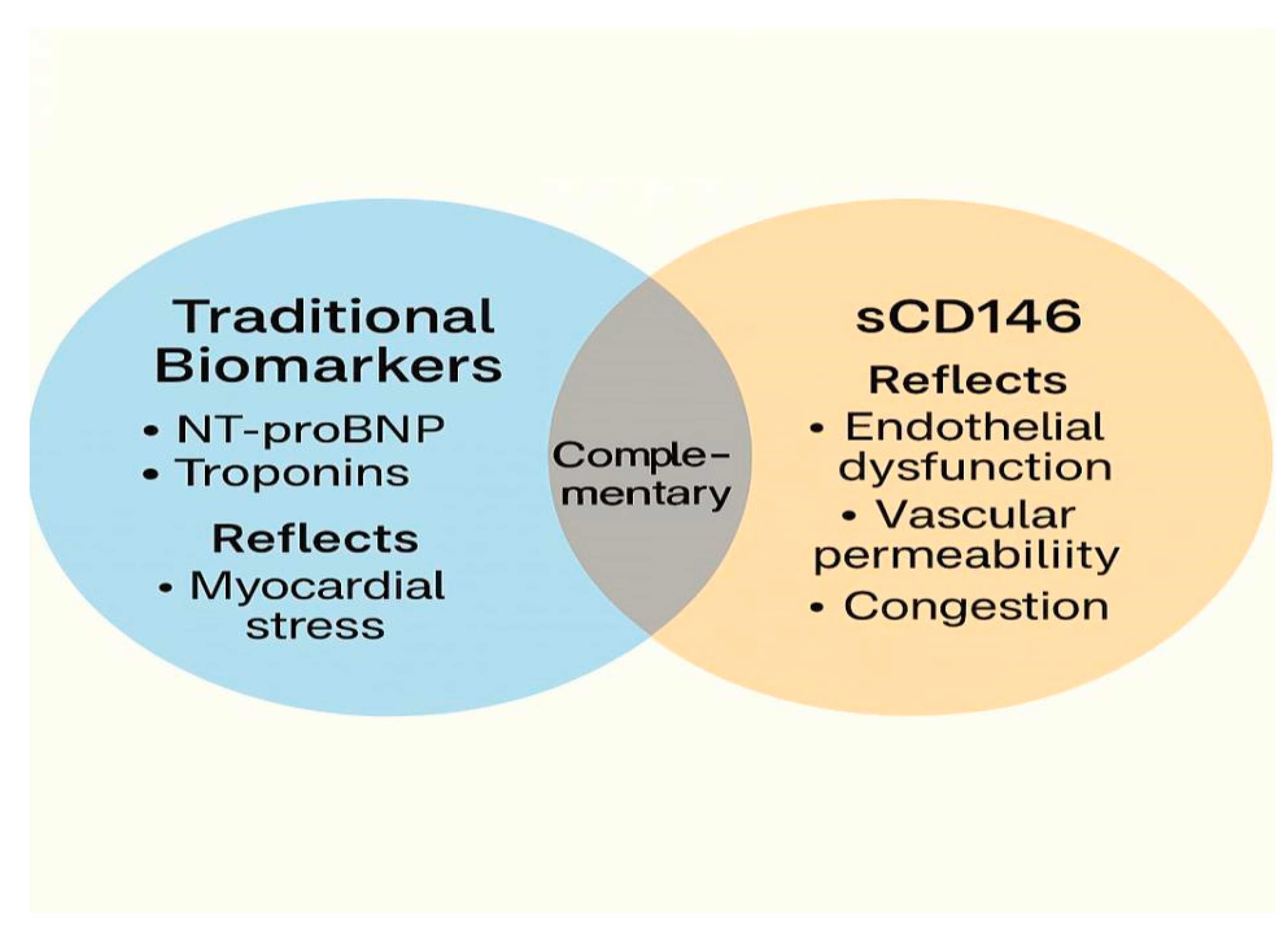

4.3. Complementarity to Established Biomarkers

Rather than serving as a replacement for established biomarkers such as NT-proBNP or troponins, sCD146 should be viewed as complementary, offering distinct yet synergistic information about vascular congestion and endothelial integrity, a depicted in

Figure 2 [

20,

34,

36,

38]. When combined with NT-proBNP, sCD146 has been shown to improve diagnostic precision in patients with borderline or ambiguous presentations, particularly those with multiple comorbidities or non-specific dyspnea [

20].

This diagram illustrates the role of soluble CD146 (sCD146) as a biomarker for endothelial dysfunction and systemic congestion in heart failure (HF). The figure shows how sCD146 is released in response to various pathophysiological triggers, such as venous and arterial stretch, oxidative stress, and inflammatory cytokine activation. It highlights the cascade of events leading to endothelial cell activation, proteolytic shedding of sCD146, and its subsequent elevation in circulation. The figure also emphasizes the clinical relevance of sCD146 in diagnosing and monitoring congestion and endothelial integrity, correlating with traditional biomarkers like NT-proBNP and contributing to diagnostic precision in HF management.

5. Comparative Analysis: CD146 vs. Traditional Biomarkers in Heart Failure

Heart failure (HF) is a complex and heterogeneous syndrome characterized by a range of overlapping pathophysiological processes, myocardial stress, systemic congestion, neurohormonal activation, inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction [

6,

7,

35,

37,

39]. No single biomarker can comprehensively reflect all these components. Therefore, evaluating how soluble CD146 (sCD146) compares with and complements established HF biomarkers is essential to appreciating its unique and additive value in clinical practice.

Table 2 presents a comparative analysis between biomarkers.

Among the traditional biomarkers, natriuretic peptides, namely B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) and N-terminal proBNP (NT-proBNP), remain the cornerstone of HF diagnosis and monitoring. Unlike natriuretic peptides (e.g., NT-proBNP), which are secreted by cardiac myocytes in response to chamber stretch, sCD146 reflects vascular and endothelial components of HF pathology [

1,

20,

40]. This distinction is critical, especially in HFpEF, where myocardial biomarkers may be misleadingly normal, elderly or obese patients, in whom NT-proBNP levels may be attenuated, post-treatment or residual congestion, where cardiac markers normalize faster than vascular integrity [

41]. Cardiac troponins, on the other hand, are highly specific markers of myocardial injury. Their elevation reflects acute or chronic myocardial cell damage and plays a vital role in distinguishing HF with concomitant ischemia or myocardial infarction. Nevertheless, they do not convey information regarding volume status, congestion, or endothelial function [

42,

43,

44].

Emerging biomarkers, including galectin-3, soluble ST2, and MR-proADM, have gained attention for their ability to reflect fibrosis, inflammation, or neurohormonal dysregulation, expanding the biomarker landscape. Yet, they also face challenges regarding specificity and clinical implementation [

1,

16,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49].

CD146 is fundamentally different in origin and scope. Unlike NT-proBNP or troponins, which are cardiomyocyte-derived, CD146 is endothelial in origin, reflecting vascular stress, junctional disruption, and permeability alterations. This pathophysiological lens allows sCD146 to offer unique diagnostic and prognostic insights, especially in contexts where endothelial dysfunction plays a central role, such as HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), systemic congestion, or comorbid inflammatory states [

29,

31,

33,

34].

sCD146 provides a vascular-centric biomarker that broadens the interpretative lens in heart failure and, when used in combination with traditional cardiac markers, contributes to a more comprehensive and individualized assessment of disease burden.

6. Limitations and Confounding Conditions

Despite its growing recognition as a biomarker of endothelial dysfunction and vascular congestion, soluble CD146 (sCD146) remains an investigational tool in managing heart failure. Several important limitations must be acknowledged when considering its application in research or practice, particularly in the absence of large-scale prospective validation studies [

50].

One of the most notable challenges lies in the lack of standardization across available assays for sCD146. Differences in analytical methods, sample preparation, and calibration procedures may lead to inconsistent results between laboratories, complicating the establishment of universal reference ranges or diagnostic thresholds. Moreover, the current literature reflects a heterogeneous mix of study populations, assay types, and clinical endpoints, further limiting the generalizability of existing findings [

51].

In addition to methodological concerns, biological variability introduces the potential for misinterpretation. sCD146 levels may be influenced by age, sex, renal function, and systemic inflammatory conditions, factors commonly encountered in heart failure populations. In particular, non-cardiac elevations have been reported in malignancies, autoimmune diseases, and infectious states. CD146 was originally described as a melanoma cell adhesion molecule and is overexpressed in a range of solid tumors, including breast, prostate, and hepatocellular carcinoma. In such contexts, elevated sCD146 may reflect oncological or immunological processes rather than cardiovascular pathology, thus reducing its specificity as a congestion biomarker [

37,

45]. Furthermore, the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying sCD146 elevation are still incompletely understood. While mechanical stretch, inflammation, and oxidative stress are known triggers of CD146 shedding, the temporal dynamics and interactions between these stimuli remain to be fully clarified. This gap in mechanistic understanding limits the clinical interpretability of sCD146 in borderline or multifactorial cases, particularly in polymorbid patients with overlapping disease processes. sCD146 has demonstrated correlations with markers of congestion and prognosis in observational studies, it has yet to be tested in prospective biomarker-guided interventional trials [

16,

52,

53]. Its role in therapeutic decision-making, patient stratification, or treatment response remains speculative at this stage.

7. Conclusions

CD146, particularly in its soluble form (sCD146), has emerged as a compelling biomarker at the intersection of vascular biology and heart failure pathophysiology. Its expression on endothelial cells and regulated release in response to mechanical, inflammatory, and oxidative stimuli provide a unique window into the endothelial response to systemic congestion, a central yet often underappreciated feature of heart failure progression [

6,

16,

52].

Unlike traditional biomarkers, such as natriuretic peptides, which predominantly reflect myocardial stretch and intracardiac pressure, sCD146 captures an endothelial and vascular perspective [

26,

34,

54]. This distinction is especially valuable in diagnostically ambiguous cases, such as those with preserved ejection fraction, obesity, renal dysfunction, or residual subclinical congestion, where conventional markers may fall short [

1,

16,

34].

While the current evidence underscores the diagnostic and prognostic promise of sCD146, its use in clinical practice remains limited by biological variability, assay non-standardization, and a lack of prospective interventional data. Nonetheless, its consistent associations with congestion markers, endothelial dysfunction, and adverse outcomes support further investigation and integration into multi-marker strategies for a more nuanced assessment of heart failure [

17].

Moving forward, validation in large-scale cohorts, mechanistic elucidation, and biomarker-guided therapeutic studies are needed to define the clinical role of CD146. If successfully integrated, CD146 could help personalize heart failure care by refining diagnosis, enhancing prognostication, and guiding decongestive management, ultimately aligning with the goals of precision medicine in cardiovascular disease [

1].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.M, R.J, A.U. and R.I.L.; writing—original draft preparation, D.M, R.J, A.U. and R.I.L., writing—review and editing, D.M.; visualization, D.M., R.J., D.A.J., I.G., D.F.B., M.P., A.U. .; supervision, A.U., M.P.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

The APC received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the author(s) used ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-4, March 2025) to assist with language editing and phrasing. The authors have reviewed and edited the AI-generated content and take full responsibility for the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ |

Directory of open access journals |

| TLA |

Three letter acronym |

| LD |

Linear dichroism |

References

- Mocan, D.; Lala, R. I.; Puschita, M.; Pilat, L.; Darabantiu, D. A.; Pop-Moldovan, A. The Congestion “Pandemic” in Acute Heart Failure Patients. Biomedicines 2024, 12 (5), 951. [CrossRef]

- Mocan, D.; Jipa, R.; Jipa, D. A.; Lala, R. I.; Rasinar, F. C.; Groza, I.; Sabau, R.; Sulea Bratu, D.; Balta, D. F.; Cioban, S. T.; Puschita, M. Unveiling the Systemic Impact of Congestion in Heart Failure: A Narrative Review of Multisystem Pathophysiology and Clinical Implications. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2025, 12 (4), 124. [CrossRef]

- Shahim, B.; Kapelios, C. J.; Savarese, G.; Lund, L. H. Global Public Health Burden of Heart Failure: An Updated Review. Card. Fail. Rev. 2023, 9, e11. [CrossRef]

- Ambrosy, A. P.; Pang, P. S.; Khan, S.; Konstam, M. A.; Fonarow, G. C.; Traver, B.; Maggioni, A. P.; Cook, T.; Swedberg, K.; Burnett, J. C.; Grinfeld, L.; Udelson, J. E.; Zannad, F.; Gheorghiade, M.; on behalf of the EVEREST trial investigators. Clinical Course and Predictive Value of Congestion during Hospitalization in Patients Admitted for Worsening Signs and Symptoms of Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction: Findings from the EVEREST Trial. Eur. Heart J. 2013, 34 (11), 835–843. [CrossRef]

- Martens, P.; Mullens, W. How to Tackle Congestion in Acute Heart Failure. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2018, 33 (3), 462–473. [CrossRef]

- Mullens, W.; Damman, K.; Harjola, V.; Mebazaa, A.; Brunner-La Rocca, H.; Martens, P.; Testani, J. M.; Tang, W. H. W.; Orso, F.; Rossignol, P.; Metra, M.; Filippatos, G.; Seferovic, P. M.; Ruschitzka, F.; Coats, A. J. The Use of Diuretics in Heart Failure with Congestion — a Position Statement from the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2019, 21 (2), 137–155. [CrossRef]

- Dupont, M.; Mullens, W.; Tang, W. H. W. Impact of Systemic Venous Congestion in Heart Failure. Curr. Heart Fail. Rep. 2011, 8 (4), 233–241. [CrossRef]

- Aelst, L. V.; Arrigo, M.; Plácido, R.; Akiyama, E.; Girerd, N.; Zannad, F.; Manivet, P.; Rossignol, P.; Badoz, M.; Sadoune, M.; Launay, J.; Gayat, É.; Lam, C. S.; Cohen-Solal, A.; Mebazaa, A.; Séronde, M.-F. Acutely Decompensated Heart Failure With Preserved and Reduced Ejection Fraction Present With Comparable Haemodynamic Congestion. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2017, 20 (4), 738–747. [CrossRef]

- Alevroudis, I.; Kotoulas, S.-C.; Tzikas, S.; Vassilikos, V. Congestion in Heart Failure: From the Secret of a Mummy to Today’s Novel Diagnostic and Therapeutic Approaches: A Comprehensive Review. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 13 (1), 12. [CrossRef]

- Boorsma, E. M.; Ter Maaten, J. M.; Damman, K.; Dinh, W.; Gustafsson, F.; Goldsmith, S.; Burkhoff, D.; Zannad, F.; Udelson, J. E.; Voors, A. A. Congestion in Heart Failure: A Contemporary Look at Physiology, Diagnosis and Treatment. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2020, 17 (10), 641–655. [CrossRef]

- Colombo, P. C.; Doran, A. C.; Onat, D.; Wong, K. Y.; Ahmad, M.; Sabbah, H. N.; Demmer, R. T. Venous Congestion, Endothelial and Neurohormonal Activation in Acute Decompensated Heart Failure: Cause or Effect? Curr. Heart Fail. Rep. 2015, 12 (3), 215–222. [CrossRef]

- Pirrotta, F.; Mazza, B.; Gennari, L.; Palazzuoli, A. Pulmonary Congestion Assessment in Heart Failure: Traditional and New Tools. Diagnostics 2021, 11 (8), 1306. [CrossRef]

- Rosenkranz, S.; Howard, L. S.; Gomberg-Maitland, M.; Hoeper, M. M. Systemic Consequences of Pulmonary Hypertension and Right-Sided Heart Failure. Circulation 2020, 141 (8), 678–693. [CrossRef]

- Drera, A.; Rodella, L.; Brangi, E.; Riccardi, M.; Vizzardi, E. Endothelial Dysfunction in Heart Failure: What Is Its Role? J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13 (9), 2534. [CrossRef]

- Paulus, W. J.; Tschöpe, C. A Novel Paradigm for Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 62 (4), 263–271. [CrossRef]

- Núñez, J.; De La Espriella, R.; Rossignol, P.; Voors, A. A.; Mullens, W.; Metra, M.; Chioncel, O.; Januzzi, J. L.; Mueller, C.; Richards, A. M.; De Boer, R. A.; Thum, T.; Arfsten, H.; González, A.; Abdelhamid, M.; Adamopoulos, S.; Anker, S. D.; Gal, T. B.; Biegus, J.; Cohen-Solal, A.; Böhm, M.; Emdin, M.; Jankowska, E. A.; Gustafsson, F.; Hill, L.; Jaarsma, T.; Jhund, P. S.; Lopatin, Y.; Lund, L. H.; Milicic, D.; Moura, B.; Piepoli, M. F.; Ponikowski, P.; Rakisheva, A.; Ristic, A.; Savarese, G.; Tocchetti, C. G.; Van Linthout, S.; Volterrani, M.; Seferovic, P.; Rosano, G.; Coats, A. J. S.; Bayes-Genis, A. Congestion in Heart Failure: A Circulating Biomarker-based Perspective. A Review from the Biomarkers Working Group of the Heart Failure Association, European Society of Cardiology. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2022, 24 (10), 1751–1766. [CrossRef]

- Al-Sadawi, M.; Saad, M.; Ayyadurai, P.; Shah, N. N.; Bhandari, M.; Vittorio, T. J. Biomarkers in Acute Heart Failure Syndromes: An Update. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 2022, 18 (3), e090921196330. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhai, C.; Yang, X.; Li, H.; Wu, L.; Li, L. Knockdown of CD146 Promotes Endothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition via WNT/Β-Catenin Pathway. Plos One 2022, 17 (8), e0273542. [CrossRef]

- Joshkon, A.; Heim, X.; Dubrou, C.; Bachelier, R.; Traboulsi, W.; Stalin, J.; Fayyad-Kazan, H.; Badran, B.; Foucault-Bertaud, A.; Leroyer, A. S.; Bardin, N.; Blot-Chabaud, M. Role of CD146 (MCAM) in Physiological and Pathological Angiogenesis—Contribution of New Antibodies for Therapy. Biomedicines 2020, 8 (12), 633. [CrossRef]

- Gayat, E.; Caillard, A.; Laribi, S.; Mueller, C.; Sadoune, M.; Seronde, M.-F.; Maisel, A.; Bartunek, J.; Vanderheyden, M.; Desutter, J.; Dendale, P.; Thomas, G.; Tavares, M.; Cohen-Solal, A.; Samuel, J.-L.; Mebazaa, A. Soluble CD146, a New Endothelial Biomarker of Acutely Decompensated Heart Failure. Int. J. Cardiol. 2015, 199, 241–247. [CrossRef]

- Arrigo, M.; Truong, Q. A.; Onat, D.; Szymonifka, J.; Gayat, E.; Tolppanen, H.; Sadoune, M.; Demmer, R. T.; Wong, K. Y.; Launay, J. M.; Samuel, J.-L.; Cohen-Solal, A.; Januzzi, J. L.; Singh, J. P.; Colombo, P. C.; Mebazaa, A. Soluble CD146 Is a Novel Marker of Systemic Congestion in Heart Failure Patients: An Experimental Mechanistic and Transcardiac Clinical Study. Clin. Chem. 2017, 63 (1), 386–393. [CrossRef]

- Bardin, N.; Blot-Chabaud, M.; Despoix, N.; Kebir, A.; Harhouri, K.; Arsanto, J.-P.; Espinosa, L.; Perrin, P.; Robert, S.; Vely, F.; Sabatier, F.; Le Bivic, A.; Kaplanski, G.; Sampol, J.; Dignat-George, F. CD146 and Its Soluble Form Regulate Monocyte Transendothelial Migration. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2009, 29 (5), 746–753. [CrossRef]

- Leroyer, A. S.; Blin, M. G.; Bachelier, R.; Bardin, N.; Blot-Chabaud, M.; Dignat-George, F. CD146 (Cluster of Differentiation 146): An Adhesion Molecule Involved in Vessel Homeostasis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2019, 39 (6), 1026–1033. [CrossRef]

- Bardin, N.; Anfosso, F.; Massé, J.-M.; Cramer, E.; Sabatier, F.; Bivic, A. L.; Sampol, J.; Dignat-George, F. Identification of CD146 as a Component of the Endothelial Junction Involved in the Control of Cell-Cell Cohesion. Blood 2001, 98 (13), 3677–3684. [CrossRef]

- Piek, A.; Du, W.; De Boer, R. A.; Silljé, H. H. W. Novel Heart Failure Biomarkers: Why Do We Fail to Exploit Their Potential? Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2018, 55 (4), 246–263. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, N.; Du, X.; Xu, G.; Yan, X. CD146, from a Melanoma Cell Adhesion Molecule to a Signaling Receptor. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5 (1), 148. [CrossRef]

- Mußbacher, M.; Schossleitner, K.; Kral-Pointner, J. B.; Salzmann, M.; Schrammel, A.; Schmid, J. A. More Than Just a Monolayer: The Multifaceted Role of Endothelial Cells in the Pathophysiology of Atherosclerosis. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2022, 24 (6), 483–492. [CrossRef]

- Kratzer, A.; Chu, H. W.; Salys, J.; Moumen, Z.; Leberl, M.; Bowler, R. P.; Zamora, M. R.; Tarasevičienė-Stewart, L. Endothelial Cell Adhesion Molecule CD146: Implications for Its Role in the Pathogenesis of COPD. J. Pathol. 2013, 230 (4), 388–398. [CrossRef]

- Espagnolle, N.; Guilloton, F.; Deschaseaux, F.; Gadelorge, M.; Sensébé, L.; Bourin, P. CD 146 Expression on Mesenchymal Stem Cells Is Associated with Their Vascular Smooth Muscle Commitment. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2014, 18 (1), 104–114. [CrossRef]

- Simonavičius, J.; Mikalauskas, A.; Rocca, H.-P. B. Soluble CD146—an Underreported Novel Biomarker of Congestion: A Comment on a Review Concerning Congestion Assessment and Evaluation in Acute Heart Failure. Heart Fail. Rev. 2020, 26 (3), 731–732. [CrossRef]

- Kubena, P.; Arrigo, M.; Parenica, J.; Gayat, E.; Sadoune, M.; Ganovska, E.; Pavlusova, M.; Littnerova, S.; Spinar, J.; Mebazaa, A.; GREAT Network. Plasma Levels of Soluble CD146 Reflect the Severity of Pulmonary Congestion Better Than Brain Natriuretic Peptide in Acute Coronary Syndrome. Ann. Lab. Med. 2016, 36 (4), 300–305. [CrossRef]

- Stalin, J.; Harhouri, K.; Hubert, L.; Subrini, C.; Lafitte, D.; Lissitzky, J.-C.; Elganfoud, N.; Robert, S.; Foucault-Bertaud, A.; Kaspi, E.; Sabatier, F.; Aurrand-Lions, M.; Bardin, N.; Holmgren, L.; Dignat-George, F.; Blot-Chabaud, M. Soluble Melanoma Cell Adhesion Molecule (sMCAM/sCD146) Promotes Angiogenic Effects on Endothelial Progenitor Cells through Angiomotin. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288 (13), 8991–9000. [CrossRef]

- Bardin, N.; Moal, V.; Anfosso, F.; Daniel, L.; Brunet, P.; Sampol, J.; George, F. Soluble CD146, a Novel Endothelial Marker, Is Increased in Physiopathological Settings Linked to Endothelial Junctional Alteration. Thromb. Haemost. 2003, 90 (11), 915–920. [CrossRef]

- Juknevičienė, R.; Simonavičius, J.; Mikalauskas, A.; Čerlinskaitė-Bajorė, K.; Arrigo, M.; Juknevičius, V.; Alitoit-Marrote, I.; Kablučko, D.; Bagdonaitė, L.; Vitkus, D.; Balčiūnas, M.; Zuozienė, G.; Barysienė, J.; Žaliaduonytė, D.; Stašaitis, K.; Kavoliūnienė, A.; Mebazaa, A.; Čelutkienė, J. Soluble CD146 in the Detection and Grading of Intravascular and Tissue Congestion in Patients with Acute Dyspnoea: Analysis of the Prospective Observational Lithuanian Echocardiography Study of Dyspnoea in Acute Settings (LEDA) Cohort. BMJ Open 2022, 12 (9), e061611. [CrossRef]

- Dick, S. A.; Epelman, S. Chronic Heart Failure and Inflammation: What Do We Really Know? Circ. Res. 2016, 119 (1), 159–176. [CrossRef]

- Van Aelst, L. N. L.; Arrigo, M.; Placido, R.; Akiyama, E.; Girerd, N.; Zannad, F.; Manivet, P.; Rossignol, P.; Badoz, M.; Sadoune, M.; Launay, J.; Gayat, E.; Lam, C. S. P.; Cohen-Solal, A.; Mebazaa, A.; Seronde, M. Acutely Decompensated Heart Failure with Preserved and Reduced Ejection Fraction Present with Comparable Haemodynamic Congestion. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2018, 20 (4), 738–747. [CrossRef]

- Van Aelst, L. N. L.; Arrigo, M.; Placido, R.; Akiyama, E.; Girerd, N.; Zannad, F.; Manivet, P.; Rossignol, P.; Badoz, M.; Sadoune, M.; Launay, J.; Gayat, E.; Lam, C. S. P.; Cohen-Solal, A.; Mebazaa, A.; Seronde, M. Acutely Decompensated Heart Failure with Preserved and Reduced Ejection Fraction Present with Comparable Haemodynamic Congestion. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2018, 20 (4), 738–747. [CrossRef]

- Omar, H. R.; Guglin, M. The Emerging Role of New Biomarkers of Congestion in Heart Failure. J. Lab. Precis. Med. 2017, 2, 24–24. [CrossRef]

- Farmakis, D.; Parissis, J.; Papingiotis, G.; Filippatos, G. Acute Heart Failure; Oxford University Press, 2018; Vol. 1. [CrossRef]

- Castiglione, V.; Aimo, A.; Vergaro, G.; Saccaro, L.; Passino, C.; Emdin, M. Biomarkers for the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure. Heart Fail. Rev. 2022, 27 (2), 625–643. [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.-I.; Lee, M. Y.; Oh, B. K.; Lee, S. J.; Kang, J. G.; Lee, S. H.; Lee, J.-Y.; Kim, B. J.; Kim, B. S.; Kang, J. H.; Sung, K.-C. Effects of Age, Sex, and Obesity on N-Terminal Pro B-Type Natriuretic Peptide Concentrations in the General Population. Circ. J. 2021, 85 (5), 647–654. [CrossRef]

- Berkmen, Y. M.; Lande, A. Chest Roentgenography as a Window to the Diagnosis of Takayasu’s Arteritis. Am. J. Roentgenol. Radium Ther. Nucl. Med. 1975, 125 (4), 842–846. [CrossRef]

- Peacock, W. F.; De Marco, T.; Fonarow, G. C.; Diercks, D.; Wynne, J.; Apple, F. S.; Wu, A. H. B. Cardiac Troponin and Outcome in Acute Heart Failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 358 (20), 2117–2126. [CrossRef]

- Januzzi, J. L.; Filippatos, G.; Nieminen, M.; Gheorghiade, M. Troponin Elevation in Patients with Heart Failure: On Behalf of the Third Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction Global Task Force: Heart Failure Section. Eur. Heart J. 2012, 33 (18), 2265–2271. [CrossRef]

- Zaborska, B.; Sikora-Frąc, M.; Smarż, K.; Pilichowska-Paszkiet, E.; Budaj, A.; Sitkiewicz, D.; Sygitowicz, G. The Role of Galectin-3 in Heart Failure—The Diagnostic, Prognostic and Therapeutic Potential—Where Do We Stand? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24 (17), 13111. [CrossRef]

- Riccardi, M.; Myhre, P. L.; Zelniker, T. A.; Metra, M.; Januzzi, J. L.; Inciardi, R. M. Soluble ST2 in Heart Failure: A Clinical Role beyond B-Type Natriuretic Peptide. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2023, 10 (11), 468. [CrossRef]

- Voors, A. A.; Kremer, D.; Geven, C.; Ter Maaten, J. M.; Struck, J.; Bergmann, A.; Pickkers, P.; Metra, M.; Mebazaa, A.; Düngen, H.; Butler, J. Adrenomedullin in Heart Failure: Pathophysiology and Therapeutic Application. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2019, 21 (2), 163–171. [CrossRef]

- Pandhi, P.; Ter Maaten, J. M.; Emmens, J. E.; Struck, J.; Bergmann, A.; Cleland, J. G.; Givertz, M. M.; Metra, M.; O’Connor, C. M.; Teerlink, J. R.; Ponikowski, P.; Cotter, G.; Davison, B.; Van Veldhuisen, D. J.; Voors, A. A. Clinical Value of Pre-discharge Bio-adrenomedullin as a Marker of Residual Congestion and High Risk of Heart Failure Hospital Readmission. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2020, 22 (4), 683–691. [CrossRef]

- Rademaker, M. T.; Cameron, V. A.; Charles, C. J.; Lainchbury, J. G.; Nicholls, M. G.; Richards, A. M. Adrenomedullin and Heart Failure. Regul. Pept. 2003, 112 (1–3), 51–60. [CrossRef]

- Pellicori, P.; Kallvikbacka-Bennett, A.; Dierckx, R.; Zhang, J.; Putzu, P.; Cuthbert, J.; Boyalla, V.; Shoaib, A.; Clark, A. L.; Cleland, J. G. F. Prognostic Significance of Ultrasound-Assessed Jugular Vein Distensibility in Heart Failure. Heart 2015, 101 (14), 1149–1158. [CrossRef]

- El-Kenawy, H. A.; Altuwayhir, A. K. I.; Fatani, D. A. q.; Barayan, N. N. A.; Alshahrani, M. S.; Sabbagh, A. A.; Alnemer, M. A. M.; AlAhmad, Z. A.; Albakri, A. A.; Kabrah, N. L. K.; Mughram, K. H. A.; Alhayek, H. J.; Alkathim, A. M. Overview on Congestive Heart Failure Imaging. Saudi Med. Horiz. J. 2022, 3 (1), 21–28. [CrossRef]

- Arrigo, M.; Parissis, J. T.; Akiyama, E.; Mebazaa, A. Understanding Acute Heart Failure: Pathophysiology and Diagnosis. Eur. Heart J. Suppl. 2016, 18 (suppl G), G11–G18. [CrossRef]

- Naddaf, N. Point of Care Ultrasound (POCUS) in the Management of Heart Failure: A Narrative Review. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14 (7), 766. [CrossRef]

- Banach, J.; Grochowska, M.; Gackowska, L.; Buszko, K.; Bujak, R.; Gilewski, W.; Kubiszewska, I.; Wołowiec, Ł.; Michałkiewicz, J.; Sinkiewicz, W. Melanoma Cell Adhesion Molecule as an Emerging Biomarker with Prognostic Significance in Systolic Heart Failure. Biomark. Med. 2016, 10 (7), 733–742. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).