Introduction

Irish Type (“IT”) carbonate-hosted Zn-Pb constitute a world class orefield recognized after the discovery of Tynagh in the early 1960s (Derry et al., 1965) and succeeding discoveries at Silvermines, Gortdrum, Navan, Galmoy and Lisheen. These deposits were all developed into successful mines and over ten, mostly smaller deposits remain undeveloped giving the orefield an endowment of >300Mt of mineralized rock (Ashton et al., 2023). The Central Irish Orefield is an important example of a relatively new metallogenetic tract, with highest concentration of Zn mineralization discovered per sq km globally (Exploration and Mining Division, 2016), found using shallow-soil geochemistry in a populated western European country - that many considered devoid of major mineral deposits. Additionally, it defines a distinct sub-class of carbonate sediment hosted Zn-Pb deposits that has features of both SEDEX and MVT mineralization leading to considerable debate as to their genesis (e.g., Hitzman and Large, 1986; Andrew, 2023; Ashton et al., 2023). While several deposits have been well documented, most research work has been rather localized, resulting from sampling campaigns focused on locally accessible mine areas and drill core. The authors having worked extensively on the Silvermines, Navan and other deposits in the Orefield stress that IT deposits are highly variable and that important aspects of the deposits remain under-researched. This paper addresses an unusual and fascinating silver-rich area in the Silvermines deposit that was not subject to academic research but where old company and consultant reports, and sample collections have been examined to document this occurrence.

Regional Geological Setting and Metallogenesis

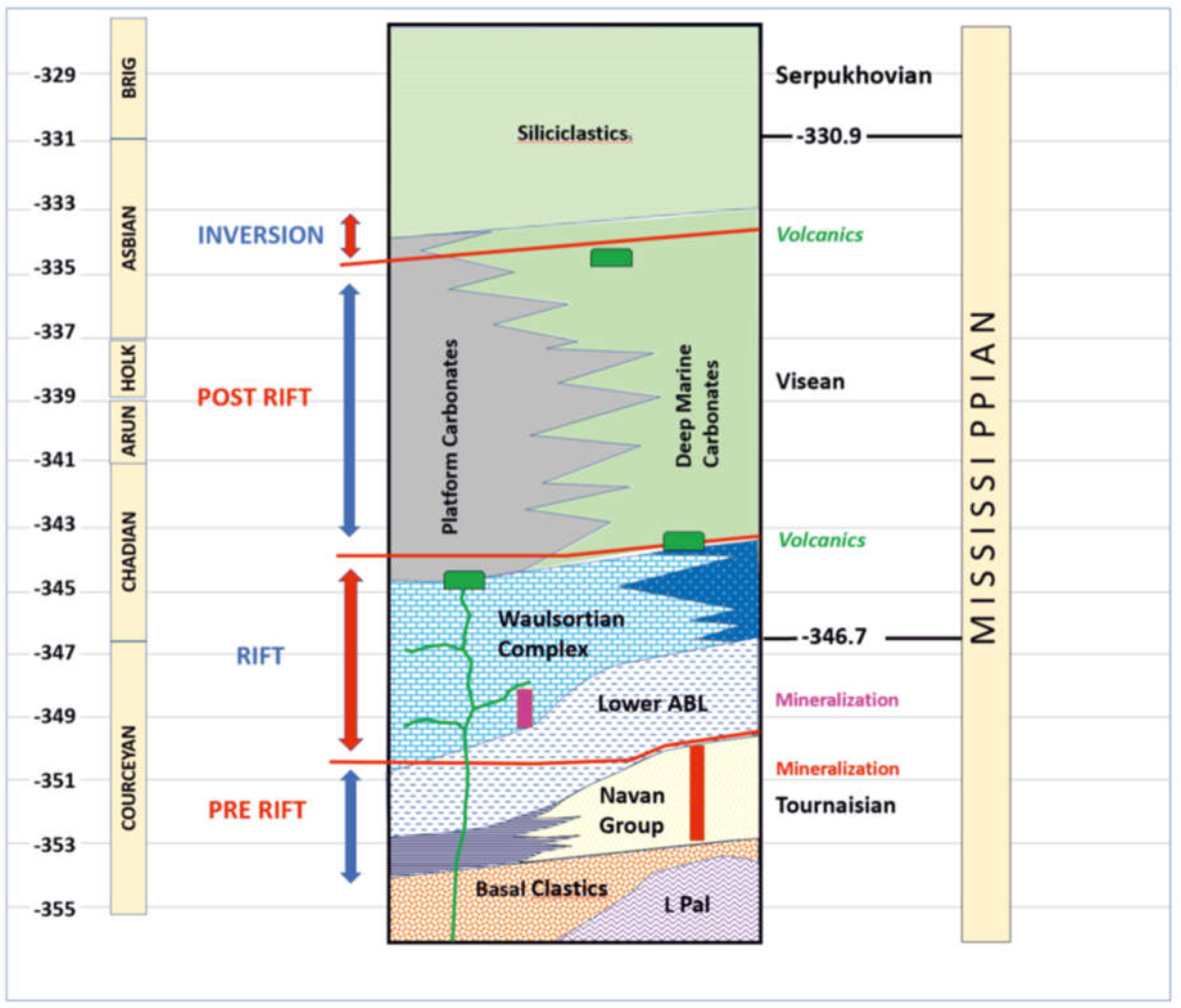

The Central Irish Orefield occupies an area of ca. 23,500 km2 where Zn and Pb deposits, with subsidiary Ag, Cu and Ba occur in stratabound, tabular, locally stratiform lenses hosted within Lower Carboniferous Courceyan to Chadian limestones and dolomites (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). These strata lie conformably on basal Carboniferous and Devonian red bed clastic sandstones and conglomerates that unconformably overlie a complex Lower Paleozoic basement comprising various greywackes, siltstones, shales and volcanics and end Silurian Caledonian granites (

Figure 2). The basement rocks are only weakly metamorphosed but are structurally complex and record the closure of the Iapetus Ocean in which Avalonian and Laurentian terranes became juxtaposed along a wide NE to ENE trending deformation zone running under the general locations of the Navan and Silvermines deposits (Phillips et al., 1976; Beamish and Smythe, 1986; Freeman et al.

, 1988; Chadwick and Holliday, 1991; Todd et al., 1991; Vaughan and Johnston, 1992; McConnell et al., 2020).) and may well have influenced the location of the larger deposits (Ashton et al., 2023). The mineralization generally occurs in the first clean carbonate units above the base of the Carboniferous (generally < 300m), this being the clean pale micrites of the Waulsortian mudbank limestone, (Lees and Miller, 1995) in many of the deposits and the Pale Beds (pale micrites and clean grainstones) in the case of Navan. Generally, the mineralization is associated with significant brecciation, dolomitization, pyritization and locally, early silica-hematite-magnetite alteration. Virtually all deposits are located adjacent to major E-E to NE-SW trending, mostly north dipping normal faults with throws commonly in hundreds of metres. These usually composite structures display complex structural histories and variable local orientations generally showing some evidence of movement contemporaneous with deposition and thickening of the Waulsortian Limestones and overlying rocks with formation of shelf-basin morphology in the Chadian to Arundian. Most fault zones exhibit superimposed wrench and reverse movement phases, that displace the mineralization and are considered to be of late Carboniferous Variscan age.

Mineralization comprises often chaotic multiple generations of usually fine-grained pale brown-yellow sphalerite interlayered with coarser galena and variable amounts of pyrite-marcasite, carbonates and barite though there is very significant inter-deposit variation that can be ascribed to geographical and host-rock variations in addition to the intensity and cyclicity of mineralization at the varying locations. Numerous textural assemblages have been recognized from massive and semi-massive, disseminated, replacement, vein, open-space fill with breccia infill and re-brecciation of sulfides. S isotope and fluid inclusion investigations are both widespread and detailed and demonstrate mixing of bacteriogenically reduced seawater sulphate with metal-carrying hydrothermal fluids carrying a smaller amount of heavy sulfur (Wilkinson and Hitzman, 2015; Andrew, 2023; Gagnevin et al., 2012).

Two models have commonly been proposed for Irish-type Zn-Pb deposits: (1) syngenetic seafloor deposition: such evidence includes stratiform geometry of some deposits, the occurrence of bedded and clastic sulphides exhibiting sedimentary textures, and, where determined, similar ages for mineralization and host rocks; or: (2) diagenetic to epigenetic replacement: such evidence includes replacement and open-space filling textures, lack of laminated sulphides, alteration and mineralization above sulphide lenses, and a claimed lack of seafloor oxidation (Andrew, 2023; Wilkinson et al., 2005, Wilkinson and Hitzman, 2015).

However, the consensus, supported by overwhelming evidence, is that mineralization occurred at depths ranging from the contemporary sediment-water interface to depths of no more than 300m or so and times close to the deposition of host sediments in the late Courceyan and into the Chadian-Arundian (Ashton et al., 2023).

Pb isotopes are interpreted as evidence of metal derivation by leaching of metals from the underlying Lower Palaeozoic basement by convection of sea-water sourced fluids during the extensional activity that promoted normal faulting (Wilkinson and Hitzman, 2015; Andrew, 2023). Extensive fluid inclusion, oxygen and carbon isotope studies have been used to constrain the nature of the ore forming fluids and depositional mechanisms (Wilkinson and Hitzman, 2015). The data is interpreted to indicate mixing of metal - carrying hydrothermal fluid, resulting from deep brine convection, with more locally sourced sulfur-carrying fluids The metal carrying fluids are hypothesized to have formed from dense brines, perhaps from partially evaporated Lower Carboniferous seawater, that was circulated to depth, presumably during extension and resultant fracturing; these fluids were then heated enabling them to more effectively leach metals. The sulfur carrying fluids are considered to have been low temperature, high salinity brines, also hypothesized to have been initially sourced from shallow-evaporitic seawater and involved in the production of reduced sulphur in the near subsurface through biological (bacteriogenic) activity. Most of the academic research on IT deposits has rightly been focused on the Zn-Pb mineralization. However more minor exotic phases of mineralization (Cu, Ag, Ni, Co, Sb and As) are known from several deposits and are important both from economic and ore genetic perspectives but have not been extensively documented. This contribution is focused on the description of one such occurrence of Ag-Ge mineralization at Silvermines deposit.

Introduction to Silver Mineralization at Silvermines

The Silvermines Zn-Pb-Ag-Ba deposits in County Tipperary, Ireland are perhaps the type-example of Irish-type Zn-Pb deposits (Taylor and Andrew, 1978; Taylor, 1983; Andrew, 1986; Ashton et al., 2023; Andrew, 2023).

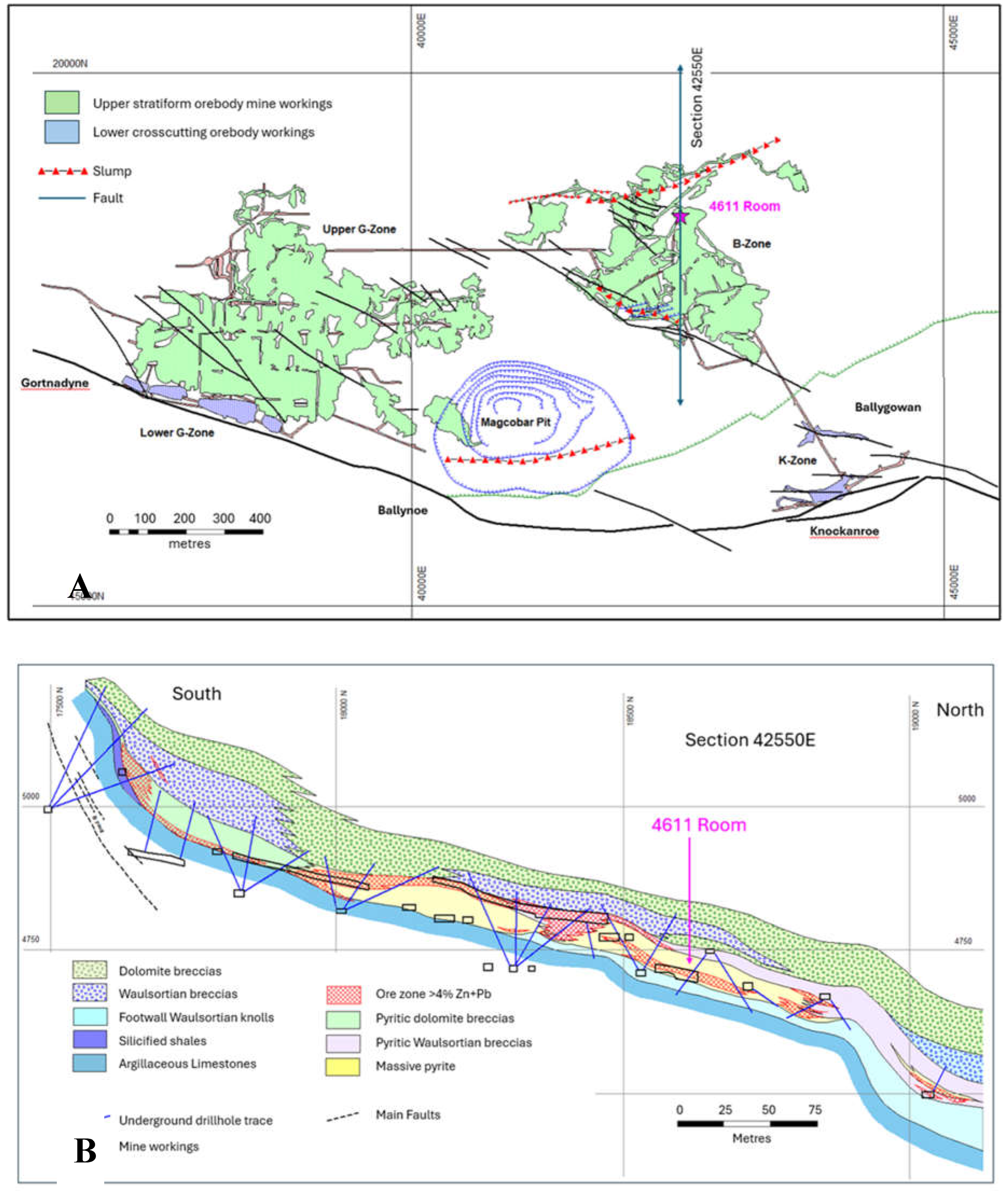

Although the area was mined sporadically over a millennium or so, the principal deposits were discovered in the early 1960s by Mogul of Ireland Ltd. and mined by underground methods, extracting ca. 10.8 Mt @ 7.36% Zn, 2.70% Pb between 1968 and 1982. A further 5.5Mt @ 85% BaSO

4 was extracted from an open pit by Magcobar Ireland Ltd. over a similar period (

Figure 3A).

Although silver was not particularly rich during the historic mining from the 10th to 19th centuries, the high silver content of the oxidized lead ores gave the area its name. A figure of 80 oz. of silver per long ton of smelted lead (~2500 g/t) is quoted by Rutty (1772) and Wynne and Kane (1861), but this almost certainly referred mainly to the oxidized ores, although Apjohn (1860) confirmed the same quantity of silver in galena being mined contemporaneously. Historic mining targeted galena with its subsidiary Ag content and minor Cu in a variety of near-surface mostly vein deposits hosted by Devonian sandstones and basal Lower Carboniferous (Courceyan) sandstones, limestones and dolomites (Rhoden, 1959). Supergene Pb and Zn oxides occur in several areas and zinc oxide mineralization was historically mined in the 1950s with further tonnages discovered by more recent exploration in the 1980s in broadly similar areas (Rhoden, 1959; Boland et al., 1992).

The more extensive mining since the 1960s exploited several large zones of Zn-Pb sulfide and barite mineralization lying on the northern, downthrown flank of the Silvermines Fault at depths of up to several hundred meters. These zones can be broadly classified into cross-cutting and stratiform types. The cross-cutting areas of veining, brecciation and mineralization are clearly structurally controlled near offshoots of the Silvermines Fault but are ‘stratabound’ in that mineralization is largely confined to basal Courceyan siliclastics and dolomitized limestones (Lower G, K, C, P, Gortnadyne and Shallee Zones;

Figure 3A). The stratiform zones (Upper G, B, Magcobar and Cooleen Zones) occur slightly higher in the stratigraphy hosted near the base of a sequence of brecciated and dolomitized Waulsortian limestones of basal Chadian age. Several detailed studies of the stratabound and stratiform zones note the spatial location of the former, stratigraphically below the latter, and outline numerous genetic characteristics to conclude that hydrothermal fluids rose up feeder structures producing the stratabound mineralization and then formed the stratiform mineralization by exhalation of fluids into the Lower Carboniferous sea and by replacement of brecciated Waulsortian limestones (Taylor and Andrew, 1978; Taylor, 1983; Andrew, 1986; Wilkinson and Lee, 2003; Kyne et al., 2019; Andrew, 2023).

We describe previously unpublished data on a small area of Ag-rich mineralization that was found in the B Zone during 1978 and may represent preservation of a relatively high temperature proximal feeder type mineralization within a developing stratiform body.

Values for silver in galena from Silvermines mostly lie in the range 300 to 700 g/t and there is no great difference between galena from the upper stratiform and lower stratabound orebodies. Galena from the Shallee mine contained between 950 to 1350 g/t of silver (production data for 1949 to 1958), and at Gortnadyne between 500 to 620 g/t (Wynne, 1861; Rhoden, 1958). A remarkable feature of the galena at Shallee mine was the multitude of inclusions of bournonite, boulangerite, and tetrahedrite (Rhoden, 1958). In direct contrast, galena at Gortnadyne mine rarely contained any exsolved minerals. Graham (1970) reported that the values for silver in galena from the Upper G-Zone all lay within the range 300 to 700g/t Ag but were slightly higher for the B-Zone at around 800 g/t.

The Mogul of Ireland flotation plant operating between 1968 and 1982 typically only recovered around 28-30% of the contained silver in mill feed producing a lead concentrate containing around 240 g/t Ag with the silver recoveries being low due to oxide lead in the feed and due to complex silver-bearer mineralogy (Carson, 1978; 1979). Some silver also reported to the zinc concentrate and this averaged 20% of the feed for an Ag in concentrate grade of around 50 g/t, however most silver reported to slimes (<5 micron) and as a result, silver recovery was always rather low and as a result the tailings from the Mogul plant typically assayed around 20 g/t Ag and 0.80% Pb, 0.81% Zn, 21% Fe (Carson, 1978, 1979).

During routine mining in July 1978, at a nominal rate of 4,000tpd, unusually high silver grades were recorded in the lead concentrate which rose from a historical norm of between 217 g/t to 310 g/t to around 715 g/t. Shortly after, an unusual podiform mass of white to pale buff crystalline barite within complex sulfides was noted by mine geologists in the 4611 Room (the “4611 Pod”) of the B-Zone. This pod contained a very unusual assemblage of silver minerals returning assays over 1.5m intervals of up to 9.55% silver - not always with commensurately high Zn, Pb values. The dimensions of this small but very high-grade silver-bearing lens suggest a total tonnage of about 500 t potentially containing up to 20 t of silver with significant germanium.

Previous Work

The nature of this rich silver occurrence is unique within the Silvermines orebodies and the diverse and exotic argentian mineralogy is significantly different from that recorded elsewhere in the district by previous authors (Graham, 1970; Rhoden, 1958; Taylor and Andrew, 1978). Very little published material exists on the 4611 Pod apart from a mention in Taylor (1983) who noted that unlike the lead-rich areas of the B-Zone, where higher silver values were associated with minute inclusions of argentian sulfosalts in galena, the 4611 Pod comprised prominent patches of discrete silver and germanium minerals (see also Moreton, 1999). Zakrzewski (1989) described members of the freibergite-argento-tennantite series and associated minerals from the location whilst unpublished company reports by Gasparrini (1978), Hall et al. (1978), Carson (1978, 1979) and Pattrick (1981) identified the mineralogical associations and provided individual mineral analyses. Considerable unpublished data has also been gleaned from notes in the routine daily underground mine geologists’ notebooks of the authors made between 27th February 1978 and 19th July 1979. Further data has been gathered from a series of 11 polished sections made from material collected by the authors.

The B Zone

The geology of the B Zone orebody comprises a tabular body of sphalerite-galena +/- barite mineralization up to 25m in thickness developed at the base of the Waulsortian equivalent breccia sequence extending over an area of approximately 800m by 750m and comprising 4.64 Mt @ 4.53% Zn, 3.38% Pb, 30 g/t Ag (Taylor and Andrew, 1978; Taylor, 1983; Andrew, 1986; Andrew, 2023). The B Zone occurs mostly downdip of the B Zone Fault, a WNW trending normal fault considered to be part of the hanging-wall of the Silvermines Fault complex (Figs. 3A and 3B). The B Zone Fault exhibits a complex slump morphology and was likely a syn-depositionally active structure (Ashton, 1975). No cross-cutting stratabound mineralization is known immediately below the B Zone, though drilling is sparse. Abundant sedimentary features such as syn-sedimentary slump breccias, graded-bedding, interbedding of sulfide and shale layers, and geopetal structures confirm the sedimentary to early diagenetic origin of the stratiform sulfide deposits (Graham, 1970, Ashton, 1975; Taylor and Andrew, 1978; Taylor 1984; Andrew, 1986; Wilkinson and Lee, 2002; Ashton et al., 2023). Sulfide textures in the stratiform orebodies are fine-grained and intricate and indicate rapid precipitation. A wide range of colloform textural fabrics is also evident.

Mineralization occurs in complex lenses and sub-lenses interdigitated and layered within variably pyritized dolomite breccias (and rarely, un-dolomitized Waulsortian limestone breccias) and very distinct areas of massive gangue mineralization comprising barite, pyrite and siderite zones where the baritic material is locally associated with haematite and minor silica. The dolomite breccias are variably pyritized and extend for tens of meters above the ore lenses and represent complex alteration and brecciation of Waulsortian limestones during and after early lithification (Lee and Wilkinson, 2002). The distinct lateral distribution and zonation of gangue mineralogy is considered to represent syndiagenetic mineralization during and after sedimentation of the Waulsortian limestones which were brecciated by syn-depositional faulting and where topographic lows formed between Waulsortian mud-mounds (Taylor and Andrew, 1978). Some authors have envisaged a later, epigenetic model for ore genesis, and this has been extensively discussed over the years (e.g., Reed and Wallace, 2004; Wilkinson and Lee, 2003; Ashton et al., 2023). However, the geometrical relationship of the stratiform B Zone to cross-cutting mineralization in underlying Courceyan limestones is undisputed and implies that mineralization in the B Zone is the result of rising hydrothermal fluids sourced from the Silvermines Fault complex contemporaneous to active sedimentation.

The 4611 Pod

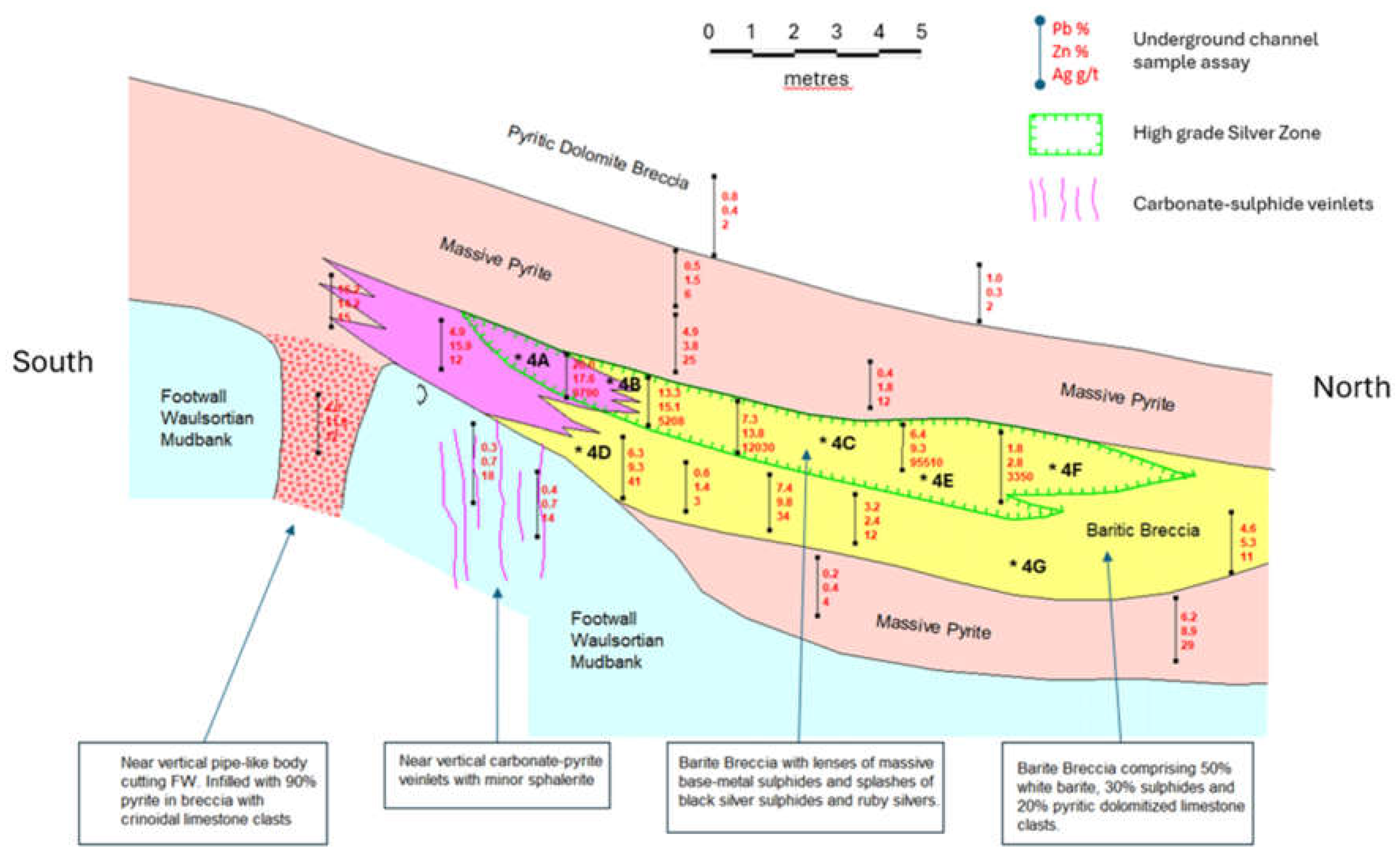

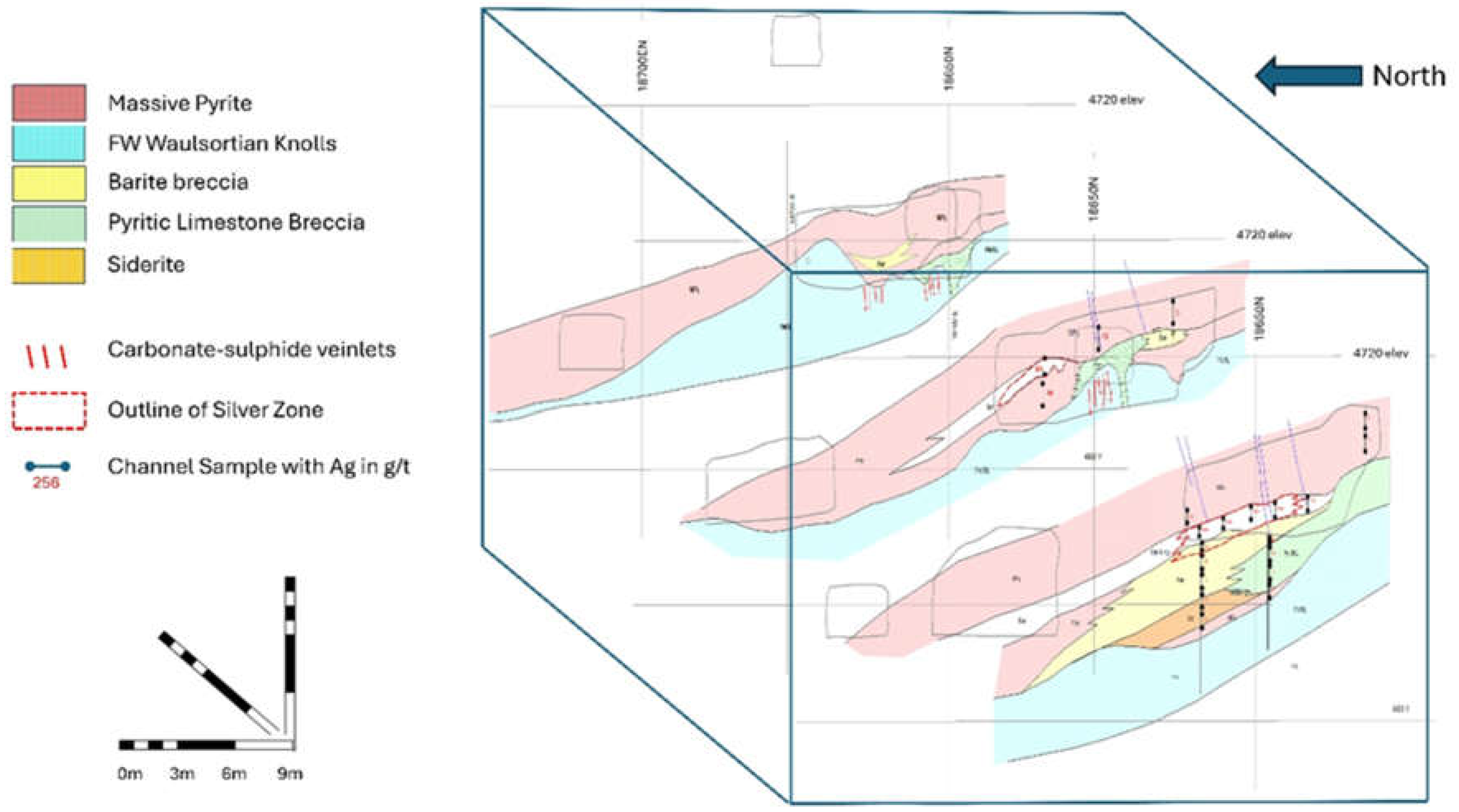

The 4611-mining block is located within the north-central part of the stratiform B Zone orebody within an area of relatively thin, but high grade (>15% Zn+Pb) ore (3-5m thick) hosted within a complex package of massive sulfide, pyritic dolomite breccias and thin lenses of siderite and barite up to a total of 10m in thickness (

Figures 3A, 3B, 4, 5). The footwall to mineralization is formed by knolls up to 15m thick of pale gray undolomitized sparsely crinoidal Waulsortian mudbank micrites with poorly developed stromatactis fabrics. In the thicker, richer sections of the B Zone, mineralization occurs at the base of the Waulsortian equivalent breccias and the 4611 area is on the flank, rather than the center, of a former paleo-topographic low between the mudbanks. This contact can be quite irregular with a distinct relief and locally shows evidence of erosion verging towards Neptunian dyke development. The hanging-wall to the mineralization is gradational and often irregular and patchy within pyritic dolomite breccias with the quantity of pyrite and sparse base metal sulfides diminishing upwards (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5).

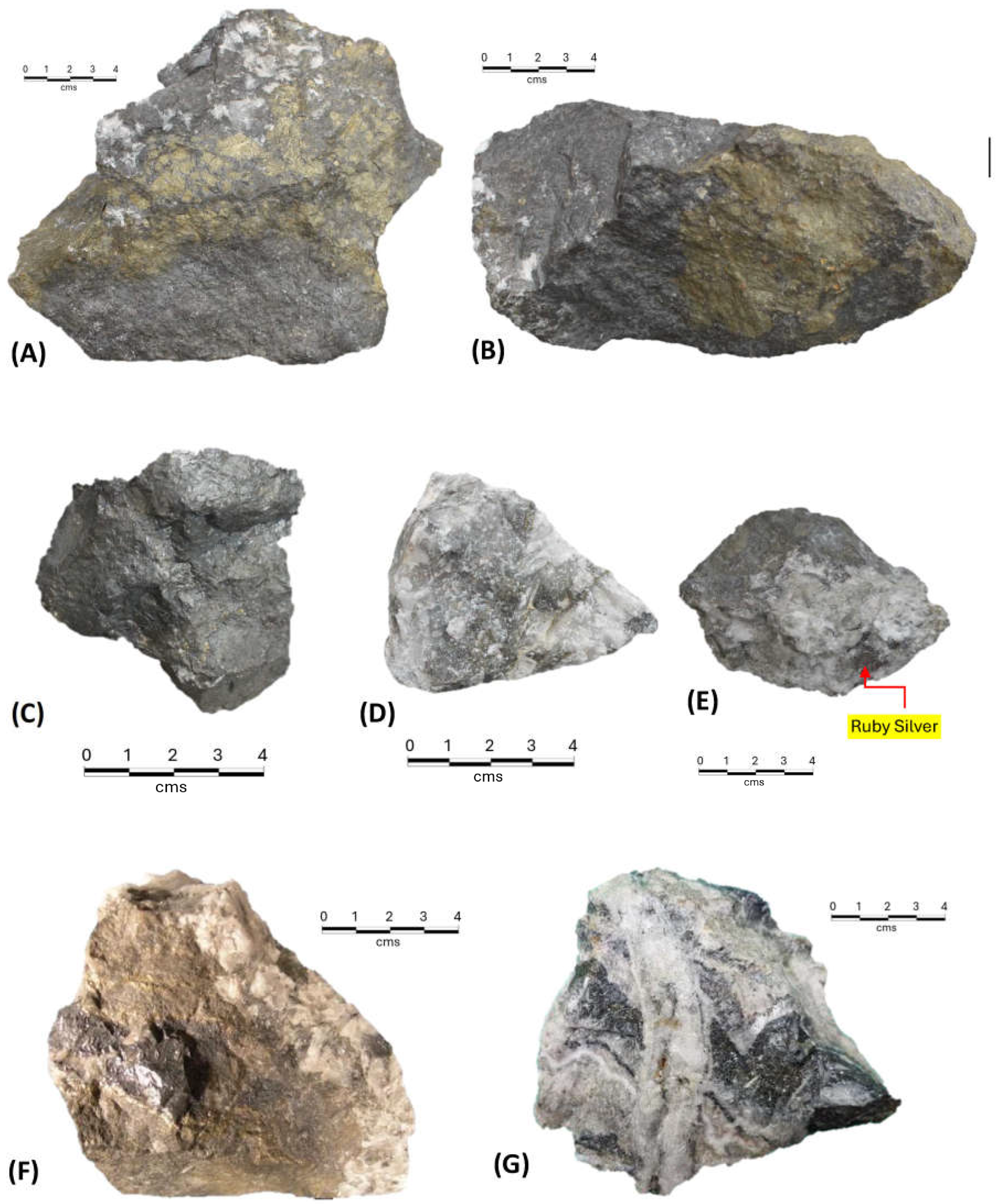

The massive sulfides comprise fine-grained massive, often brassy, pyrite typically comprising up to 90% of the rock mass with patches of rich Zn-Pb sulfides attaining grades of up to 40% metal with Zn:Pb ratios around 1:1 and average silver contents of less than 30g/t (

Figure 6A,B). Within these typical massive sulfides, a lens of buff to white barite, conformable with the overall dip, occurs with a feather edge to the north. This barite dominantly comprises white coarsely crystalline intergrown laths with minor pyrite and clasts of dolomitized and pyritic Waulsortian micrites (

Figure 6D,E). Typically, this zone comprises around 60% barite, 30% sulfides and 10% dolomitized limestone and is up to 1.5m thick. The hanging-wall contact of the barite is relatively sharp and passes upwards via a gradational contact over a few centimeters into fine grained massive sulfides with occasional bladed barite crystals and base-metal sulfides, and which overlaps onto and over the mudbank surface.

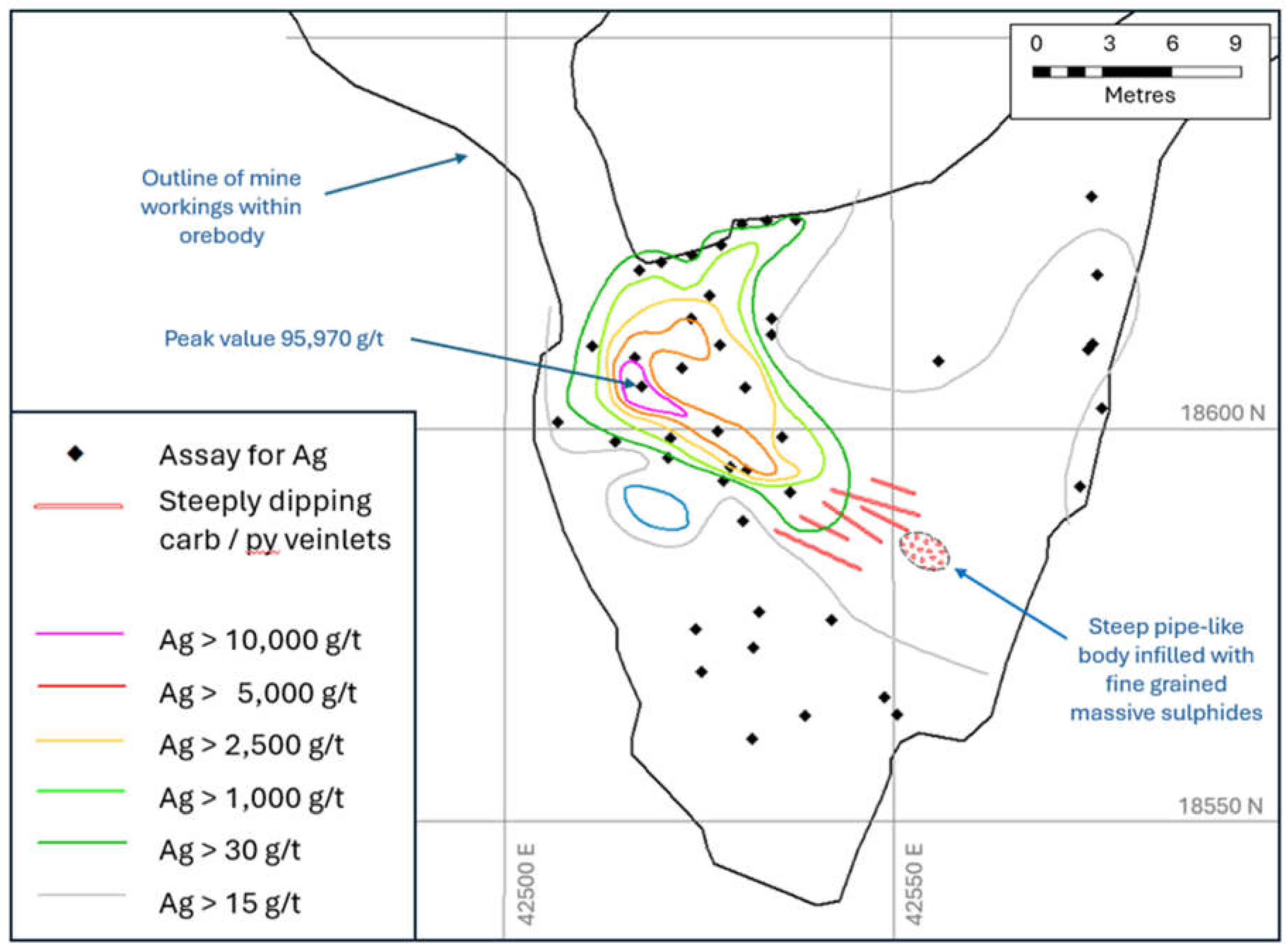

In the 4611 Room the upper part of the white barite lens contains a very localized pod of highly unusual mineralogy extending for approximately 9.5m by 8m with the long axis trending at around 150

o and up to 2m in thickness. Within this pod, masses up to 100cms by 25cms of pyritic dolomitized mudbank micrite breccia occur along with sporadic patches up to 15cm by 10cm of black silver sulfosalts with some blebs of ruby silvers up to 1cm in diameter along with galena and very fine-grained pale buff sphalerite (

Figure 6C, 6E, 6F). Grab samples of this material returned up to 20% Zn+Pb and spectacular silver grades up to 95,000 g/t (9.5% Ag) over vertical intervals of up to 2m. Whilst not analyzed during mining, the content of germanium within the pod is estimated to have exceeded 0.1% Ge based upon the content of argyrodite (Ag

8GeS

6). Below the silver enriched zone, which is up to 2m in thickness, the silver sulfosalt content of the crystalline barite diminishes rapidly with only sparse small blebs of proustite, seemingly commensurate with a fining of crystal size of the barite (

Figure 6G).

Irregular ‘secondary’ cavities up to 50 cms by 25 cms are developed within the coarse white barite and overlying massive sulfides. These cavities are largely infilled with granular pale brown barite “sand” with patches and blebs of black silver sulfosalts and ruby silvers (

Figure 6C). Prominent N-S vertical jointing associated with this cavity development and recrystallization of the barite within these cavities and on joint walls is also often associated with distinctive ruby silver minerals. This is interpreted as localized post-main mineralization groundwater-induced alteration.

The contact between the footwall Waulsortian mudbank micrite and massive sulfides or barite is gradational with diminishing mineralization and brecciation downwards. Dislocation of the breccia clasts is commonplace as demonstrated by rotated stromatactis fabrics. Within the footwall Waulsortian mudbank limestones a zone of strongly developed narrow (<1cm) veins of crustiform carbonate and pyrite trending around 160

o (±5

o) and dipping steeply NE are developed. Parallel to these veinlets a steeply dipping irregular elongate “pipe” up to around 1.5m by 2.0m in diameter, also orientated with its long axis at around 160

o (±5

o) is present. It is infilled with brecciated fine grained granular pyrite with disseminated zinc dominant base-metal sulfides assaying up to 15% combined metal with silver values around 12g/t (

Figure 4 and

Figure 7). Occasional angular clasts of crinoidal limestone are present and some carbonate occurs as intraclast cavity infill. The contacts of the pipe are sharp and there is no evidence of faulting controlling its location. It was not possible to follow it vertically for more than a few meters due to lack of exposure in mine workings and drilling. It is notable that the veinlets in the footwall trend in the same direction as the minor post-mineral faulting seen in the western part of the B Zone.

Mineralogy

In addition to Zakrzewski (1989) several unpublished reports and company memoranda on the mineralogy of the 4611 Pod exist. Reports by Hall et al. (1978), Gasparrini (1978) and Patrick (1981) utilized reflected light microscopy, electron microprobe analysis and X-Ray diffraction analysis. The pod comprised approximately 50% of coarsely crystalline white translucent barite with around 30% as lenses of very fine-grained pyrite with sphalerite and 20% comprised galena-sphalerite intergrowths and patches within dolomitized breccias. Initial examination of the pod in 1978 included analysis of several large (~10 kg) samples of representative material from within the pod and its immediate environs.

A very rich ore sample (#33308) assaying 57.05% Pb, 12.09% Zn, 4.30% Fe and 0.29% Ag (2950 g/t) was collected from the main ore horizon immediately adjacent to the apparent bounds of the silver-pod and comprised mainly of a coarse intergrowth of galena and sphalerite with veinlets and irregular crystals of pyrite. (Andrew, 1978). Radiating spheroidal dendritic intergrowths of galena in sphalerite (50–100 μm diameter) also occur and the galena contains abundant bladed inclusions of geocronite-jordanite, similar to that described by Graham (1970) from the Upper G Zone. Sample #33403 taken from the silver pod comprises gray, fine grained massive sulfides assaying 24.85% Pb, 27.40% Zn, 6.00% Fe, 0.86% Ag (8553 g/t) 0.28% Sb, 23.8% S, 1.01% Ni, 2.6% Ca, 0.11% Mg and 0.09% Mn. Pyrite is poorly crystallized (melnikovite) in patches and contains abundant inclusions of galena and sphalerite. Argyrodite is associated with sphalerite and galena and close to the argyrodite, pyrite is replaced by marcasite and gersdorffite. Intergrowths of pyrite and barite are also present and inclusions of a K, Ba, Al, Si -phase (hyalophane) occur within the pyrite (Andrew, 1978). Sample #33309 comprised white crystalline barite with pyrite, argentite-acanthite and visible blebs of ruby silvers and assayed 6.79% Pb, 8.59% Zn, 8.20% Fe, 5.8% Ag, 0.29% Sb, 1.70% As, 0.45% Cu, 1.70% As, 0.76% Ni, 0.26% Mn. This sample contains abundant sulfides in mosaic carbonate with laths of barite. Coarse- grained pyrite with patches of melnikovite are rimmed by marcasite. The iron-sulfides are veined by galena and sphalerite and contain abundant inclusions of proustite. Fine “graphic” intergrowths of pyrite and proustite were present and visible to the naked eye. Sphalerite and galena are associated in a variety of intergrowths - colloform texture, fine radiating dendritic spheroids (~ 50 μm diameter), emulsion texture (galena grains ~ 1 mm) and fine disseminations. Sphalerite also occurs as large colloform areas (1,000 μm diameter) of radiating acicular sphalerite crystals (Andrew, 1978).

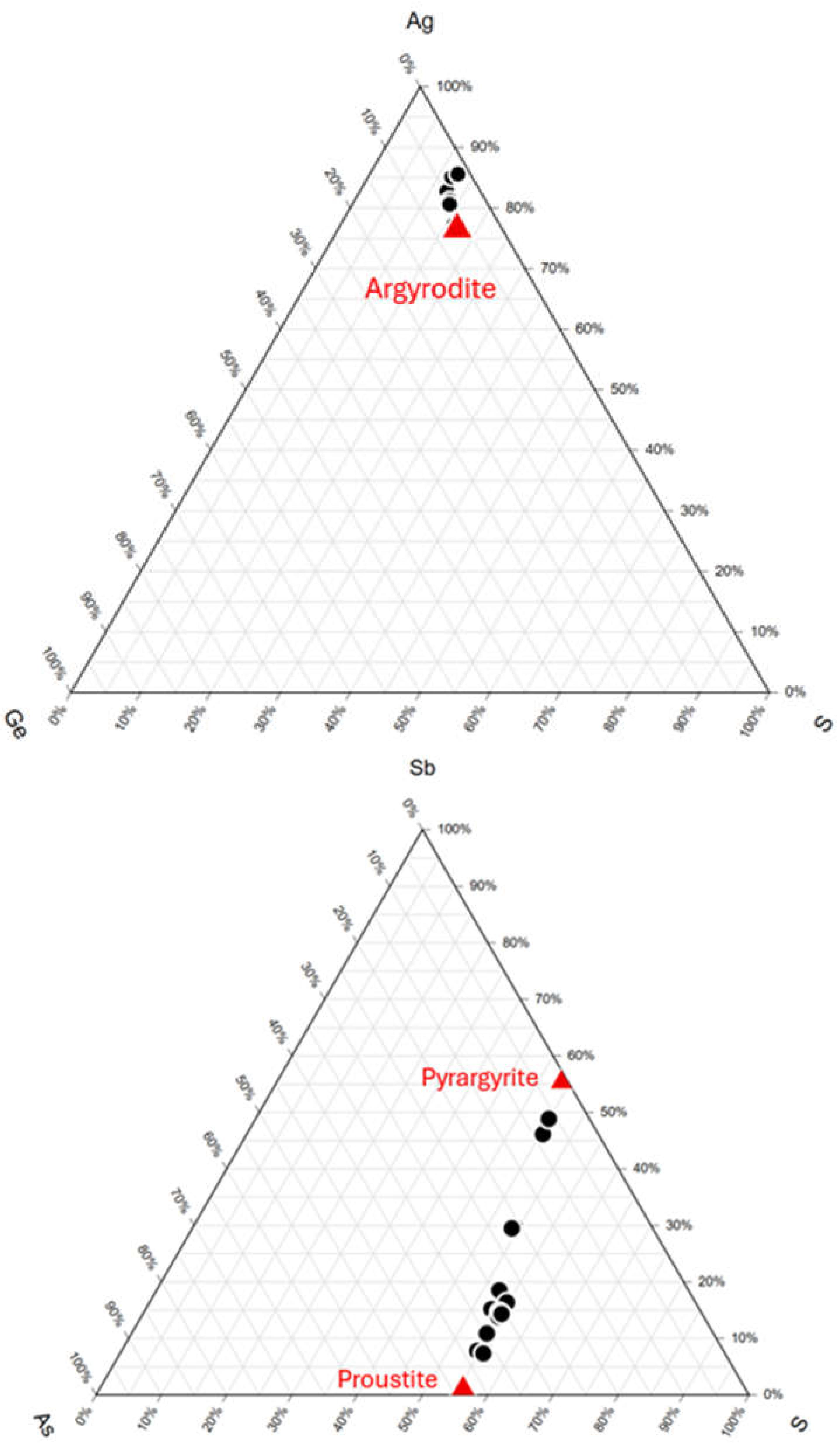

The principal silver minerals identified by subsequent investigations include members of the ruby silvers. Despite their similarity, at least five distinct species of these minerals have been recognized. They include proustite-pyrargyrite, xanthoconite and two other minerals tentatively identified, but close in composition and optical properties to smithite and arsenian miargyrite. Argentite-acanthite, argyrodite, geocronite-jordanite, diaphorite, arsenian boulangerite, argento-tetrahedrite-tennantite (freibergite) and gersdorffite have also been identified. (Hall et al., 1978; Gasparrini, 1978; Pattrick, 1981; Zakrzewski, 1989).

Minerals of the argentite-acanthite type are very abundant, locally forming in excess of 10% of the ore as large blebs of almost colloform aggregates intergrown with argyrodite up to 10cms in diameter and as finer grains occur enclosed in the major sulfides Proustite and pyrargyrite with occasional intergrowths of xanoconite, smithite and arsenian miargyrite usually form <1 vol % of the mineralization.

The germanium-silver mineral argyrodite is relatively abundant occurring as discrete blebs up to several centimeters in diameter and occurs both myrmekitically intergrown with argentite-acanthite or as monomineralic blebs which exhibit very little internal structure with narrow diffuse replacive margins to earlier sulfosalts and sulfides.

Gersdorffite mostly occurs as dense fine-grained intergrowths with geocronite and galena and as idiomorphic crystals up to 20 μm associated with myrmekitic intergrowths of proustite-pyrargyrite and galena, and, locally, as overgrowths on pyrite.

In general, the mineralization assemblage is dominated by antimonial silver minerals although arsenical variants are present. Copper and bismuth-bearing sulfosalts are sparse. Other minerals observed are sphalerite, galena and pyrite-marcasite. In some samples massive fine-grained sphalerite with up to 10 mm thick crusts of fractured marcasite is overgrown by up to 4mm sized yellowish-white crystalline barite with some of the fractures in the marcasite being infilled by ruby silvers. Galena occurs in aggregates up to several mm in diameter within the sphalerite.

Zakrzewski (1989) recorded that the minerals recognized macroscopically in paragenetic sequence comprise: galena, white dolomite, ’honeyblende’ sphalerite, and tetrahedrite as crystals up to 10 mm in size - interpreted as being a recrystallized. Textural evidence indicates that marcasite and pyrite precipitated first as colloform crusts or as granular masses. Iron sulfides are generally of a colloform fabric, occurring as complete spheroids or fragments of radially crystalline masses. Minor amounts of pyritohedral crystals and crystal aggregates are also evident within larger masses of argyrodite. Radial schallenblende-type, typically dark brown, sphalerite replaces the iron sulfides and forms botryoidal masses. Both minerals are invaded by coarse-grained first-generation galena that replaces sphalerite. Geocronite and gersdorffite crystallized together with galena whilst tetrahedrite and ruby silvers were among the later-forming phases. A second generation of galena, in the form of myrmekitic exsolutions within proustite-pyrargyrite and tetrahedrite also formed at this stage. Subsequent recrystallization produced the coarse crystals of galena, sphalerite and tetrahedrite interstitial to the host rock dolomite breccia clasts. Tetrahedrite, geocronite and gersdorffite occur as anhedral grains up to 50 μm in diameter, intergrown with geocronite, proustite-pyrargyrite and galena. They appear to replace geocronite and may be replaced by proustite-pyrargyrite (Zakrzewski, 1989).

The minerals of the ruby-silver type are all rather similar in optical properties and qualitative compositions and, apart from areas where grains of two different species were close and a comparison of the optical properties was possible, it was difficult to differentiate one from the other. A description of the individual minerals is provided as an Appendix 1:

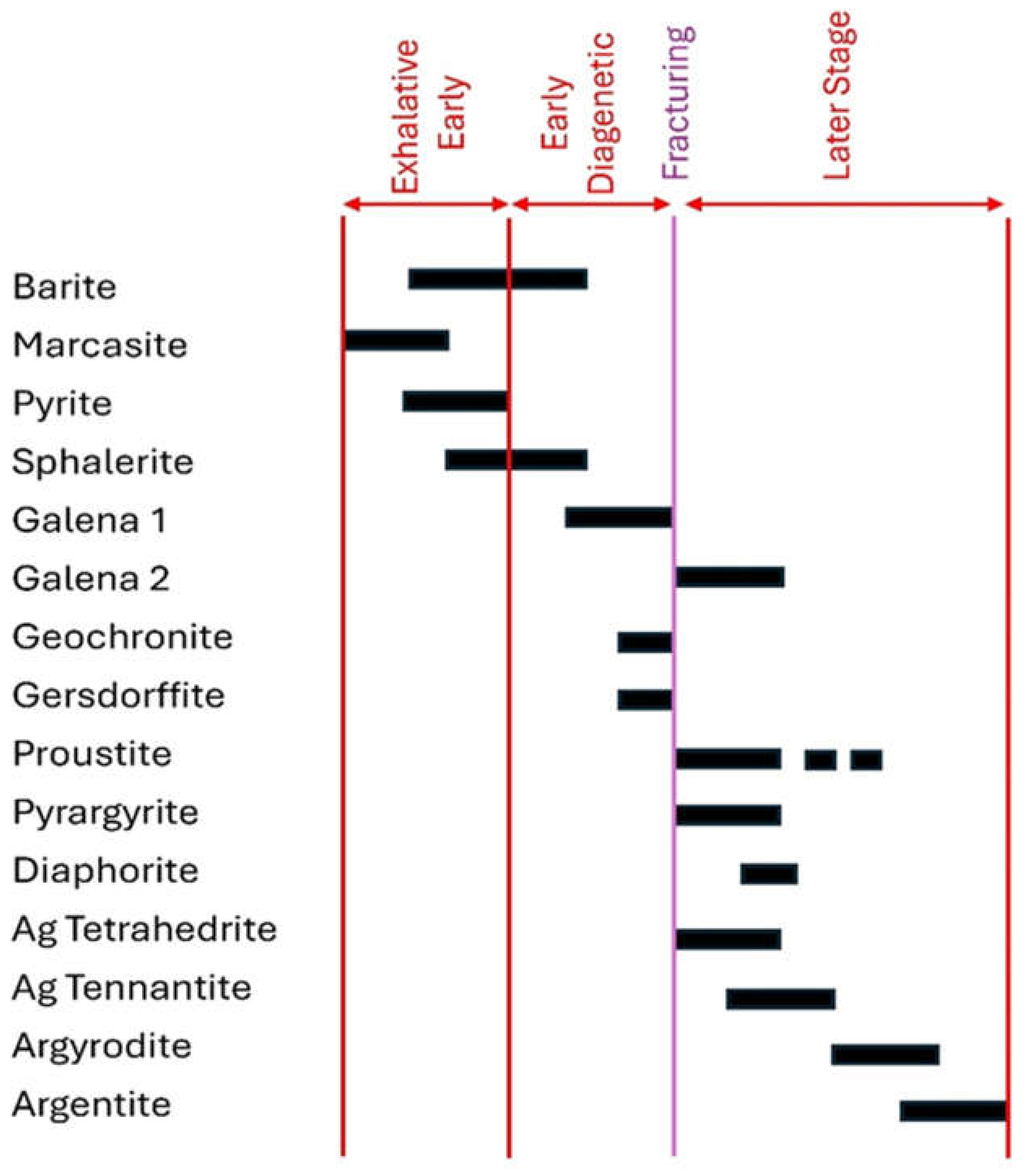

Paragenesis

Examination of several new polished sections under reflected light has confirmed the general paragenesis established by Zakrzewski (1989). Early marcasite-pyrite is followed by pale sphalerite, galena (with geochronite and gersdorffite) before a second phase of galena with ruby silvers and diaphorite-tetrahedrite: argyrodite is late with a final phase of argentite-acanthite (

Figure 9). The silver minerals show successive enrichment in Ag indicative of a sequential increase in Ag activity and possible temperature reduction of the hydrothermal fluids (

Figure 10A). In parallel with the increase in silver in the mineral species there is an equivalent reduction in the Sb content and increase in the As contents (

Figure 10B).

Many of the Sb-As species show a general paragenetic trend from antimonial to arsenian over time (

Figure 9). This compositional variation is likely to be in response to spatial and temporal changes of fluid chemistry.

Discussion

The mineralogically complex silver-rich 4611 Pod is apparently unique within the stratiform ore bodies at Silvermines although similar pods could have been mined without detection or remain undiscovered. This chemically and texturally complex assemblage of a large variety of fine-grained, intimately mixed minerals rich in silver, germanium, arsenic, antimony, bismuth and nickel, and the associated relatively high Pb-Zn ratio, suggest that the silver pod is developed where a small feeder structure channeled high temperature fluids into the developing B Zone stratiform orebody - perhaps defining a small exhalative center. High silver grades are restricted to a small area and diminish rapidly both laterally and vertically to levels typical of the overall orebody. This suggests close controls on the deposition of the silver minerals. The concentration of silver minerals within the white crystalline barite and immediately enveloping massive sulfides suggests a specific and unusual control on the silver deposition and a highly localized up-flow of silver-antimony-germanium rich hydrothermal fluid. Hall et al. (1978) postulated that the high silver grades suggested proximity to a feeder conduit as did Taylor (1983) who also suggested that concentrations of sulfosalts of copper, arsenic, and antimony provide evidence of feeder zones. Taylor and Andrew, 1978; Taylor, 1983; Andrew, 1986; Lee and Wilkinson, 2002; and Kyne et al., 2019 have all used Zn:Pb ratios to show that the positions of the large exhalative centers are most likely controlled by west north-west trending structures. However, the location of the 4611 Pod is enigmatic in that it is not located close to a known structure nor is it contained within a distinct area of bulk high lead to zinc ratios, although

localized patches of high Pb mineralization are a characteristic of the pod (

Figure 10A,

Figure 10B and

Figure 11).

In the 4611 Pod the assemblage of Ag-Ge-Sb rich minerals appears to have been superimposed upon the earlier Zn-Pb-Ba mineralization in a localized fashion. It is conceivable therefore that any feeder at 4611 was not only localized but developed later in the mineralizing process. This may have comprised a small extensional center following early movement on the B Zone Fault that allowed the development of a brine pool within a quiescent depositional environment - where early barite was replaced by argentian and base-metal sulfides as suggested by Rajabi et al. (2024) at Mehdiabad and elsewhere in the Malayer-Esfahan metallogenetic belt.

Both the silver and germanium contents of the 4611 Pod are the highest recorded in the Irish Orefield. Elsewhere in the Irish Midlands carbonate-hosted IT deposits contain generally moderate silver values. The Ge grade of Zn ores from the northernmost Navan Group hosted deposits is low (a few tens ppm Ge in sphalerite samples); but inc reases in the southern Silvermines–Lisheen group of deposits, attaining grades in sphalerite samples of above 100 ppm Ge (Eyre, 1998). Wilkinson et al. (2005) reported Ge grades from drill core samples within the Lisheen deposit of 400 to 900ppm in sphalerite: 200 to 1300ppm in galena, and 200 to 1000ppm in tennantite. Recently Group Eleven Resources have reported significant Ge values from drilling at the Ballywire prospect largely range between 23 g/t Ge and 79 g/t Ge. (Group Eleven Resources Corp - PG West – press releases). Does the extreme concentration of both Ag and Ge in the 4611 Pod indicate a localized specific source of these metals?

Ge is uncommon, but not an extremely rare element in bulk continental crust averaging 1.5 ppm for oceanic crust and 1.6 ppm for continental crust (Holl et al., 2007). Little is known about the behavior of Ge in S-bearing hydrothermal fluids, and it seems that there are two types of sulfide ore deposits which may be distinguished: (a) those where Ge is concentrated in sphalerite (up to 3000 ppm Ge) and those where Ge forms its own sulfide minerals or substitutes for metal atoms (mainly As and Sn) in sulfosalts. The behavior of Ge appears to be dependent on the sulfur activity where Ge enters ZnS in low to moderate sulfur activity environments and forms its own phases under higher fugacity of sulfur (Tamas et al., 2006). fO2 and fS2 conditions may play a key role as well in the remobilization of Ge, as this will control which Ge-mineral crystallizes. High fO2 (and low fS2) have an essential impact on remobilization of Ge in sphalerite to form Ge oxide, which is thermodynamically stable under highly oxidizing conditions (Johan and Oudin, 1986; Bernstein, 1985).

The mineralogical assemblage in the 4611 Pod is unusual and there are few analogs in the literature. Most recorded instances of the of argyrodite occur in 1) low-temperature polymetallic deposits with silver sulfosalts (Freiberg, Germany); 2) in high-temperature Sn-Ag deposits (Bolivia) and 3) in epithermal vein Au-Ag base-metal deposits (Chil Suip So et al., 1993; Zhurakova et al., 2015, Pažout et al., 2019). Studies on the physico-chemical conditions for the deposition of similar silver - germanium mineral assemblages at Himmelfurst and Bräunsdorf, Freiberg, Saxony, Germany (Martin, 1970; Burisch et al., 2019) have shown that depositional temperatures of between 180 to 220 °C existed. Chil Sup So et al. (1993) concluded that Ge deposition in the Weolyu Ag-Au vein deposit was mainly a result of cooling of hydrothermal fluids (down to 175°~210℃), due to increasing involvement of cooler meteoric waters in the epithermal system. Zhurakova et al. (2015) established that in the complex naumannite acanthite, argyrodite, galena and sphalerite ores of the Rogovik Au-Ag deposit that the Ag sulfo-selenides of the acanthite series were formed later then naumannite but within the same range of logfO2 values at temperatures below 110-177 °C from solutions with a high S concentration. The Daliangzi Pb-Zn deposit in China is one of the Ge-rich Pb-Zn deposits in the Sichuan-Yunnan-Guizhou Pb-Zn polymetallic metallogenic triangle area and the trace element signature of the sphalerite indicates that the temperature of the deposit is low-moderate: the formation temperature of the Ge-bearing sphalerite in stage II is 86–213 °C (134 °C on average) ∼ 106–238 °C (170 °C on average) (Guomeng Li et al., 2023). All of this thermometric data falls within the range of depositional temperatures well established for the Silvermines mineralization (Samson and Russell, 1983).

Conclusions

The 4611 Pod Ag occurrence is unique in the Central Irish Orefield, it probably reflects an unusual phase of hydrothermal fluid uprise from depth into the exhalative and near sea-floor mineralizing environment that controlled widespread Zn-Pb-Ba-Fe mineralization in stratiform ore zones at Silvermines. Fine-grained intergrowths, colloform and emulsion textures are interpreted as indicative of slight recrystallization of fine sulfide mud or gel whereas coarse-grained phases have either formed by more extensive recrystallization or by direct crystallization from hydrothermal solution. The large number of minerals of complex chemistry and their textural associations is compatible with a chaotic and telescoped mode of deposition and seems to be good evidence of the near- surface, exhalative-pipe interpretation of the silver- rich pod. Ore microscope and electron microprobe investigations on Zn-Pb-Ag ores from B Zone in Silvermines, Ireland, have shown the presence of two As-Sb-Ag phases; a tetrahedrite-group mineral (jalpaite argentian tetrahedrite) and proustite-pyrargyrite. It is postulated that both phases inherited their As and Sb from primary geochronite and that they are metastable (Zakrzewski (1989). The enrichment in Ni in the ores is due to very fine to submicroscopic intergrowths of gersdorffite with geochronite and with galena. The silver-germanium mineralization seems to be temporally related to a phase of minor WNW-ESE trending fracturing that post-dates the major movement on the Silvermines fault complex and the principal early exhalative and near seafloor pyrite-barite-siderite hosted Zn-Pb mineralization (

Figure 5 and

Figure 11). Why this extremely rich closely constrained small body contains such high silver and germanium grades remains a mystery.

Acknowledgments

The 4611-Room silver pod is known in industry circles, but little data has been written up on this intriguing part of the Silvermines orebodies. Both authors were mine geologists at Silvermines when mining operations intersected and extracted the pod now over 45 years ago and felt that the discovery merited description and publication. Fortunately, we kept a good representative collection of samples from the pod and also had numerous contemporary notebooks, internal reports and historic analytical data available to form the basis of this paper. Thanks, are also due to the various mine geologists and samplers at Silvermines and especially to Stewart Taylor, former Chief Geologist at the mine.

Appendix – Description of Minerals

Proustite – Pyrargyrite, Ag

3(AsSb)S

3 - occurs in most samples and forms exsolutions in the sphalerite and is intergrown with galena, pyrite and antimonial sulfosalts. It was also observed enclosed within white barite. Where it occurs as disseminations with the common sulfides the proustite is finer grained (100 - 200 μm in size), however in barite it often forms coarser crystalline grains up to 1cm in diameter. Zakrzewski (1989) noted that ruby silvers occur as veinlets and irregular masses between other minerals and myrmekitic intergrowths with galena are common. Ruby silvers usually form <1 vol % of the mineralization but, along with argentite and argyrodite - because of their high silver content - are the main silver carriers. Proustite-pyrargyrite contains between 61.77 and 67.26% Ag (n=17) and exhibit a semi-continuous trend between the antimonial and arsenical end members - with samples returning between 2.38 to 18.11% Sb and 2.31 to 12.38% As (Pattrick, 1981; Zakrzewski, 1989), (see

Figure 8).

Xanthoconite, Ag3AsS3 is dimorphous with proustite. Under reflected light it is pale bluish in color but slightly less blue than the proustite. The internal reflection is yellowish- brown rather than blood red and looks tarnished when compared to the proustite. According to Gasparrini (1978) the mineral is fairly abundant in some samples.

Smithite, AgAsS2 is grayish – white under reflected light with a pale bluish tint, anisotropic with red internal reflections and shows the light etching property of tarnishing when exposed to the microscope light.

Arsenian miargyrite, Ag(As,Sb)S3 was observed by Gasparrini (1978) in one sample where it comprised the major silver- bearing phase. The mineral shows a deeper blue color under reflected light than the proustite-pyrargyrite and forms exsolutions in, and intergrowths with other sulfosalts.

Argentite-acanthite Ag2S is generally associated with the argyrodite, proustite, galena and barite. These two minerals are polymorphs and difficult to distinguish. Minerals of the argentite-acanthite type are very abundant, locally forming in excess of 10% of the ore as large blebs of almost colloform aggregates intergrown with argyrodite up to 10cms in diameter and as finer grains occur enclosed in the major sulfides. They were observed in smaller amounts associated with proustite, galena, barite and hyalophane by Gasparrini (1978).

Argyrodite Ag

8GeS

6 occurs as blebs and massive dark gray to black aggregates with a purplish tinge (it is photosensitive and darkens under exposure to light). The mineral forms quite discrete monomineralic blebs up to a few centimeters across and exhibits very little internal structure with diffuse replacive margins to earlier sulfosalts and sulfides. Argyrodite is the end-member of the series argyrodite - canfieldite (Ag

8GeS

6-Ag

8SnS

6) however SEM microanalysis by Gasparrini (1978) revealed that only silver, germanium and sulfur are present in the material from the 4611 Pod. Analysis of argyrodite samples returned an average (n=8) of 76.51% Ag and 6.44% Ge (Pattrick, 1981; Zakrzewski, 1989), (

Figure 8 and

Table 1).

Geochronite - Jordanite Pb₁₄(Sb, As)

7S₂ is always associated with galena. It occurs as grains up to 200 μm, often poly-synthetically twinned and also as unusual intergrowths of geocronite with gersdorffite that are discussed below. The As/(As+Sb) ratios from assays fall in the range of 0.42 to 0.48 indicating that the samples analysed lie almost exactly between jordanite and geochronite (Pattrick, 1981), (

Table 1).

Diaphorite, Pb

2Ag

3Sb

3S

8 also always occurs within galena where it occurs as rounded grains possibly exsolving from the lead sulfide. Very thin rinds of microcrystalline ruby-silvers are common with traces of argyrodite. the diaphorite contains up to 0.6% Cu seemingly at the expense of sulfur whilst Ag averages (n=4) 24.83% (Pattrick, 1981; Zakrzewski, 1989), (See

Table 1.)

Boulangerite Pb

5(Sb, As)

4S

11 is essentially antimonial with Sb:As ratios all within the range of 40-230. The boulangerites also contain minor amounts of silver averaging 1.17% (n=14). (Pattrick, 1981; Zakrzewski, 1989). The silver content seems to increase in parallel with zinc (

Table 1).

Gersdorffite (Ni,Fe)AsS mostly occurs as dense fine-grained, homogeneously distributed, intergrowths with geocronite and galena, as idiomorphic crystals up to 20μm associated with myrmekitic intergrowths of proustite-pyrargyrite and galena, and as overgrowths on pyrite; but in most cases as dense fine-grained, homogeneously distributed, intergrowths with geocronite and galena. Individual grains of gersdorffite show considerable analytical variations of the Ni/Fe ratios from 1.1 to 3.0, but they are too small to observe any zonation. The average Ni content (n=7) is 21.64% but there is quite a wide variation from 18.99% to 25.90% (Pattrick, 1981; Zakrzewski, 1989). Complex very fine-grained intergrowths of gersdoffite, geochronite and galena analysed up to 0.86% Ag and 14.28% Ni (see

Table 2) (Pattrick, 1981).

Pyrite/Marcasite (FeS2) appears from assay data to be relatively stoichiometric but differs slightly from the overall orebody average in that in limited analytical data the Co:Ni ratio rises above the norm to 1.89 whereas the Co and Ni content in the colloform pyrite from different parts of the orebody does not show much variation and the Co:Ni ratio is consistently less than one. The framboidal pyrite has slightly more Ni and a very low Co:Ni ratio (Graham, 1970; Carson, 1978; 1979).

Sphalerite (ZnS2) analyses returned Cd values up to 0.49% and Fe values up to 0.47% (Graham, 1970; Pattrick, 1981). No anomalous Ge values were detected in the sphalerite in the 4611 Pod, unlike at Gortdrum where Steed (1975) recognized a sympathetic increase in Ge with Fe and darker sphalerite color from ~5ppm to ~50ppm Ge.

Tetrahedrite – Tennantite (Cu,Fe,Ag,Zn)

12(As,Sb)

4S

13 is relatively common forming replacive masses within the massive pyrite. Analytical data shows that Cu and Ag combine to run between 40.4 and 45.18% with Cu:Ag ratios varying from 0.70 to 23.53 whilst (As/As+Sb) ratios range between 0.09 to 0.46 (n=8) (Pattrick, 1981; Zakrzewski, 1989). Tetrahedrite – tennantite has As/As+Sb ratios from between 0.09 and 0.46 with two distinct groupings of Sb contents at around 23% and 14% suggesting two distinct phases. Copper and silver seem to be inter-related with Cu:Ag ratios clustered around 1 and between 12-24 although apparently unrelated to As/Sb (Pattrick, 1981; Zakrzewski, 1989), (

Table 1). All analyses of the Ag-As-rich tetrahedrites from Silvermines have more than 3 Ag atoms per formula unit and could be classified as members of the freibergite – argento-tennantite series. Analyses yield As/(As+Sb) ratios ranging from 0.11 to 0.83 and therefore could be characterized as ranging from stibian argento-tennantite to arsenian freibergite (Pattrick, 1981; Zakrzewski, 1989). Many of the Sb-As species show a general paragenetic trend from antimonial to arsenian over time (

Figure 9). This compositional variation is likely to be in response to spatial and temporal changes of fluid chemistry.

Figure 12.

Contoured silver content of the B-Zone showing the location of silver highs coincident with high lead mineralization (see

Figure 10) on the hanging-wall of the B-Fault. Also shown the outline of the >4% Pb+Zn orebody and principal structures in red. Note the location of the 4611 Room silver pod. Data from surface and underground diamond drilling intercepts where Ag assays completed.

Figure 12.

Contoured silver content of the B-Zone showing the location of silver highs coincident with high lead mineralization (see

Figure 10) on the hanging-wall of the B-Fault. Also shown the outline of the >4% Pb+Zn orebody and principal structures in red. Note the location of the 4611 Room silver pod. Data from surface and underground diamond drilling intercepts where Ag assays completed.

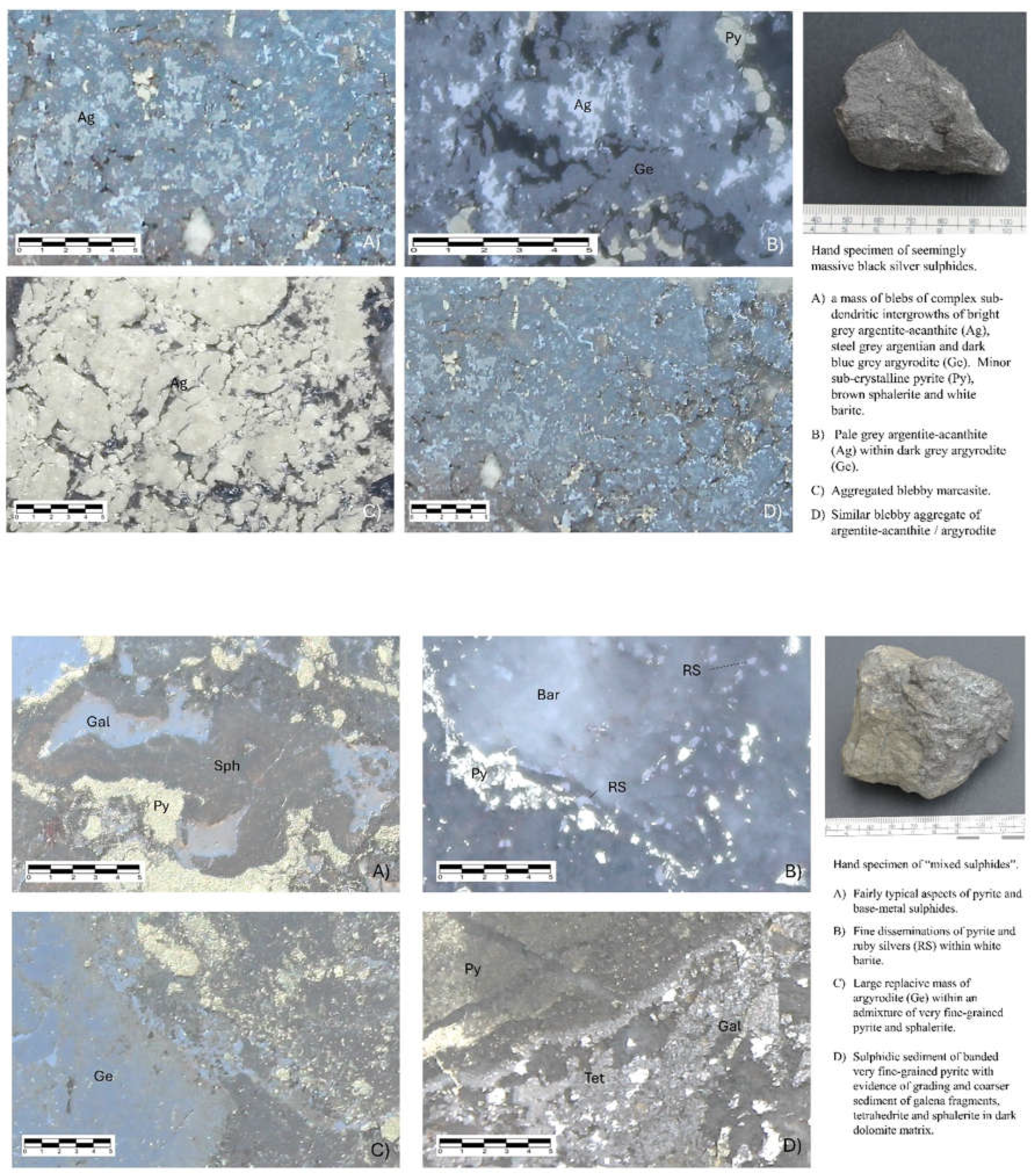

Figure 13.

Photomicrographs of textures from the silver mineralization. All scale bars in mm. 13A) Hand specimen of high-grade silver bearing massive sulphide. (1) Broken pyrite crystals set in black dolomite against a complex mixture of tetrahedrite and boulangerite. (2) Diffuse almost felted aggregates of set within black dolomite and crystalline pyrite. (3) Blebby recrystallized framboidal pyrite being replaced by grey tetrahedrite with minor white galena. (4) Coarse grained yellow pyrite in dolomite matrix in contact with complex intergrowth of tetrahedrite and boulangerite. 13B) Hand specimen of dominantly white crystalline barite with visible ruby silvers. (1) Pyrargyrite forming along cleavage planes within white barite and granular sector zoned marcasite. (2) Colour enhanced photo A) to enhance ruby silvers. (3) Bleb of pyrargyrite within white barite adjacent to recrystallized framboidal pyrite and replacive sphalerite. (4) Colour enhanced photo C) to enhance ruby silvers. 13C) Hand specimen of seemingly massive black silver sulphides. (1) a mass of blebs of complex sub-dendritic intergrowths of bright grey argentite-acanthite (Ag), steel grey argentian and dark blue grey argyrodite (Ge). Minor sub-crystalline pyrite (Py), brown sphalerite and white barite. (2) Pale grey argentite-acanthite (Ag) within dark grey argyrodite (Ge). (3) Aggregated blebby marcasite. (4) Similar blebby aggregate of argentite-acanthite/argyrodite; 13D) Hand specimen of “mixed sulphides”. (1) Fairly typical aspects of pyrite and base-metal sulphides. (2) Fine disseminations of pyrite and ruby silvers (RS) within white barite. (3) Large replacive mass of argyrodite (Ge) within an admixture of very fine-grained pyrite and sphalerite. (4) Sulphidic sediment of banded very fine-grained pyrite with evidence of grading and coarser sediment of galena fragments, tetrahedrite and sphalerite in dark dolomite matrix.

Figure 13.

Photomicrographs of textures from the silver mineralization. All scale bars in mm. 13A) Hand specimen of high-grade silver bearing massive sulphide. (1) Broken pyrite crystals set in black dolomite against a complex mixture of tetrahedrite and boulangerite. (2) Diffuse almost felted aggregates of set within black dolomite and crystalline pyrite. (3) Blebby recrystallized framboidal pyrite being replaced by grey tetrahedrite with minor white galena. (4) Coarse grained yellow pyrite in dolomite matrix in contact with complex intergrowth of tetrahedrite and boulangerite. 13B) Hand specimen of dominantly white crystalline barite with visible ruby silvers. (1) Pyrargyrite forming along cleavage planes within white barite and granular sector zoned marcasite. (2) Colour enhanced photo A) to enhance ruby silvers. (3) Bleb of pyrargyrite within white barite adjacent to recrystallized framboidal pyrite and replacive sphalerite. (4) Colour enhanced photo C) to enhance ruby silvers. 13C) Hand specimen of seemingly massive black silver sulphides. (1) a mass of blebs of complex sub-dendritic intergrowths of bright grey argentite-acanthite (Ag), steel grey argentian and dark blue grey argyrodite (Ge). Minor sub-crystalline pyrite (Py), brown sphalerite and white barite. (2) Pale grey argentite-acanthite (Ag) within dark grey argyrodite (Ge). (3) Aggregated blebby marcasite. (4) Similar blebby aggregate of argentite-acanthite/argyrodite; 13D) Hand specimen of “mixed sulphides”. (1) Fairly typical aspects of pyrite and base-metal sulphides. (2) Fine disseminations of pyrite and ruby silvers (RS) within white barite. (3) Large replacive mass of argyrodite (Ge) within an admixture of very fine-grained pyrite and sphalerite. (4) Sulphidic sediment of banded very fine-grained pyrite with evidence of grading and coarser sediment of galena fragments, tetrahedrite and sphalerite in dark dolomite matrix.

References

- Andrew, C.J., 1978, Investigation into anomalous silver values in head grade: Mogul of Ireland Internal Memo, 15th July 1978.

- Andrew, C.J., 1986, The tectono-stratigraphic controls to mineralization in the Silvermines area, County Tipperary, Ireland, in: Andrew, C.J., Crowe, R.W.A., Finlay, S., Pennell, W. and Pyne, J.F., eds., Geology and genesis of mineral deposits in Ireland: Irish Association for Economic Geology, Dublin, p. 377-417: . [CrossRef]

- Andrew, C.J., 2023, Irish Zn-Pb deposits – a review of the evidence for the timing of mineralization. Constraints of stratigraphy and basin development, in: Andrew, C.J., Hitzman, M.W. and Stanley, G., eds., Irish-type deposits around the world: Irish Association for Economic Geology, Dublin, p. 169-210: . [CrossRef]

- Apjohn, J., 1860, On the occurrence of electric calamine at the Silver Mines, County of Tipperary: Jour. Geol. Soc. Dublin.

- Ashton, J.H., 1975, A geological study of the B Zone base metal deposit at the Mogul of Ireland mine, Silvermines, Eire: Unpublished B.Sc. Thesis, University of London.

- Ashton, J.H., Andrew, C.J. and Hitzman, M.W., 2023, Irish-type Zn-Pb deposits - What are they and can we find more? in: Andrew, C.J., Hitzman, M.W. and Stanley, G., eds., Irish-type deposits around the world’: Irish Association for Economic Geology, Dublin, p. 95-146:. [CrossRef]

- Beamish, D. & Smythe, D.K. (1986) Geophysical images of the deep crust: the Iapetus suture. Journal of the Geological Society, London, v. 143, 489-497. [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, L.R.,1985, Germanium geochemistry and mineralogy: Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, v. 49, p. 2409–2422.

- Boland, M.B., Clifford, J.A., Meldrum, A.H. and Poustie, A., 1992, Residual base metal and barite mineralization at Silvermines, Co. Tipperary, Ireland, in: Bowden, A.A., Earls, G., O’Connor, P.G. and Pyne, J.F., eds., The Irish Minerals Industry 1980-1990: Irish Association for Economic Geology, Dublin, p. 247-260.

- Burisch, M., Hartmann, A., Bach, W., Krolop, P. Krause, J. and Gutzmer, J., 2019, Genesis of hydrothermal silver-antimony-sulfide veins of the Bräunsdorf sector as part of the classic Freiberg silver mining district, Germany: Mineralium Deposita, v. 54, p. 263–280. [CrossRef]

- Carson, D., 1978, Mogul of Ireland silver recoveries: Internal Memo, Mogul of Ireland Ltd., Dec. 6th, 1978.

- Carson, D., 1979, Mogul of Ireland silver recoveries: Internal Memo, Mogul of Ireland Ltd., Feb. 16th, 1979.

- Chadwick, R.A. & Holliday, D.W. (1991). Deep crustal structure and Carboniferous basin development within the Iapetus convergence zone, northern England. Journal Geol. Soc. London, v.148, 41-53. [CrossRef]

- Chil Sup So, Seong Taek Yun and Seon Gyu Choi., 1993, Occurrence and geochemistry of argyrodite, a germanium-bearing mineral (Ag8Ge6) from the Weolyu Ag-Au hydrothermal vein deposits: Korean Society of Natural Resources and Environmental Geology, Resources, Environment and Geology, v. 26 (2).

- Derry, D.R, Clark, G.R. and Gillatt, N., 1965, The Northgate Base-Metal Deposit at Tynagh, County Galway, Ireland - A Preliminary Geological Study: Economic Geology, v. 60, p. 1218-1237.

- Exploration and Mining Division, 2016, Zinc and Lead in Ireland: Department of Communications, Climate Action and Environment, Dublin, 6 p.

- Eyre, S.L., 1998, Geochemistry of dolomitization and Zn–Pb mineralization in the Rathdowney Trend, Ireland: Unpublished Ph. D. Thesis, University of London, 418 p.

- Freeman, B., Klemperer, S.L. & Hobbs R.W. (1988). The deep structure of northern England and the Iapetus Suture zone from BIRPS deep seismic reflection profiles. Journal of the Geological Society, London, v.145, 727-740. [CrossRef]

- Gagnevin, G., Boyce, A.J., Barie, C.D., Menuge, J.F. and Blakeman R.J. 2012 Zn, Fe and S fractionation in a large hydrothermal system. Geochim et Cosmochimica Actya, 88, p183-198.

- Gasparrini, C., 1978, Identification and description of the silver-bearing minerals in ten sulphide samples from Ireland: Confidential report prepared for Noranda Mines Ltd. by MinMet Scientific, Toronto, Canada, 22 Nov 1978.

- Graham R. A. F., 1970. The Mogul base metal deposits, Co. Tipperary, Ireland: Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, University of Western Ontario.

- Guomeng Li, Zhixin Zhao, Junhao Wei, and Ulrich, T., 2023, Mineralization processes at the Daliangzi Zn-Pb deposit, Sichuan-Yunnan-Guizhou metallogenic province, SW China: Insights from sphalerite geochemistry and zoning textures: Ore Geology Reviews, v. 161, October 2023. [CrossRef]

- Hall, A.J., Pattrick, R.A. and Russell, M.J., 1978, Economic implications of the origin of the silver-rich mass in ‘B Zone’ (Room 4611) Silvermines: Confidential Report prepared for Mogul of Ireland Ltd. by Dept. of Applied Geology, University of Strathclyde, Scotland. 15 Dec 1978.

- Hitzman, M.W. and Large, D., 1986, Carbonate-hosted base metal deposits, in: Andrew, C.J., Crowe, R.W.A., Finlay, S., Pennell, W.M. and Pyne, J.F., eds., Geology and Genesis of Mineral Deposits in Ireland: Dublin, Irish Association for Economic Geology, p. 217-238.

- Höll, R., Kling, M. and Schroll, E., 2007, Metallogenesis of germanium - a review: Ore Geology Reviews, v. 30, p. 145 - 180.

- Johan, Z., and Oudin, E., 1986, Présence de grenats, Ca3Ga2(GeO4)3, Ca3Al2((Ge, Si)O4)3 et d’un équivalent ferrifère, germanifère et gallifère de la sapphirine, Fe4(Ga, Sn, Fe)4(Ga, Ge)6O20, dans la blende des gisements de la zone axiale pyrénéenne. Conditions de la formation des phases germanifères et gallifères: Comptes Rendus de l’Académie des Sciences, Series IIA (Earth and Planetary Science), v. 303, p. 811–816.

- Kyne, R., Torremans, K., Güven, G., Doyle, D. and Walsh, J., 2019, 3-D Modeling of the Lisheen and Silvermines Deposits, County Tipperary, Ireland: Insights into Structural Controls on the Formation of Irish Zn-Pb Deposits: Economic Geology, v. 114, no. 1, p. 93-116.

- Lee, M.J. and Wilkinson, J.J., 2002, Cementation, hydrothermal alteration, and Zn-Pb mineralization of carbonate breccias in the Irish Midlands: textural evidence from the Cooleen Zone, near Silvermines, County Tipperary: Economic Geology, v. 97, p. 653-662.

- Lees, A. & Miller, J. (1995) Waulsortian banks. In: Monty CLV, Bosence DWJ, Bridges PH, Pratt BR (eds) Carbonate mudmounds. International Association of Sedimentologists Spec Publ 23. Blackwell Science, Oxford, 191–271.

- Martin, D.K., 1970, Die Himmelsfürst-Fundgrube hinter Erbisdorf bei Freiberg/Sachsen: Der Aufschluss, v. 21(10), p. 332-337.

- Moreton, S., 1999, The Silvermines District – Co Tipperary, Ireland: The Mineralogical Record, 30 March-April 1999, v. 99-106.

- McConnell, B., Riggs, N. & Fritschle, T. (2020) Tectonic history across the Iapetus suture zone in Ireland. In: Murphy, J. B., Strachan, R. A. and Quesada, C. (eds.). Pannotia to Pangaea: Neoproterozoic and Paleozoic Orogenic Cycles in the Circum-Atlantic Region. Geological Society, London, Special Publication. 503. 333–345.

- Pattrick, R., 1981, Internal correspondence to Mogul of Ireland dated 21 October 1981.

- Pažout, R., Sejkora, J. and Šrein, V., 2019, Ag-Pb-Sb Sulfosalts and Se-rich Mineralization of Anthony of Padua Mine near Poličany - Model Example of the Mineralization of Silver Lodes in the Historic Kutná Hora Ag-Pb Ore District, Czech Republic: Minerals 2019, v. 9(7), p. 430. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, W.E.A., Stillman, C. J. & Murphy, T., (1976) A Caledonian plate tectonic model. Journal of the Geological Society, London, v.132, p. 579 - 609. [CrossRef]

- Rajabi, A., Mahmoodi, P., Alfonso, P., Canet, C., Andrew, C., Azhdari, S., Rezaei S., Alaminia Z., Tamarzadeh S., Yarmohammadi A., Khan Mohammadi G., and Rasoul Saeidi 2024 Barite Replacement as a Key Factor in the Genesis of Sediment-Hosted Zn-Pb±Ba and Barite-Sulfide Deposits: Ore Fluids and Isotope (S and Sr) Signatures from Sediment-Hosted Zn-Pb±Ba Deposits of Iran Minerals 2024, 14, 671. [CrossRef]

- Reed, C.P. and Wallace, M.W., 2004, Zn–Pb mineralization in the Silvermines district, Ireland: a product of burial diagenesis: Mineralium Deposita, v. 39, p. 87-102.

- Rhoden, N. H., 1959. Structure and Economic Mineralization of the Silvermines District, Co. Tipperary, Eire: Trans. Inst. Min. Metall, v. 68, P. 67–94.

- Rutty, J., 1772, An essay towards a natural history of the County of Tipperary: Dublin Soc., v. 2.

- Samson I.M. and Russell, M. J., 1983, Fluid inclusion data from the Silvermines Zn + Pb + BaSO4 deposits, Ireland: Inst. Mining Metallurgy Trans., v. 92, sec. B, p. 67-71.

- Steed, G.M., 1975, The Geology and Mineralization of the Gortdrum District: PhD Thesis, University of London, 332 p.

- Tamas, C.G., Bailly, L., Ghergari, L., O’Connor, G. and Minut, A., 2006, New occurrences of tellurides and argyrodite in Rosia Montana, Apuseni Mountains, Romania, and their metallogenetic significance: The Canadian Mineralogist, v. 44, p. 367-383.

- Taylor, S. and Andrew, C.J., 1978, Silvermines orebodies, Co. Tipperary, Ireland: Trans. Inst. Mining and. Metall. (Sect. B: Appl. Earth sci.), v. 87, B111-124.

- Taylor, S., 1984, Structural and palaeotopographic controls of lead-zinc mineralization in the Silvermines orebodies, Republic of Ireland: Economic Geology, v. 79, p. 529-548.

- Todd, S.P., Murphy, F.C. & Kennan, P.S. (1991). On the trace of the Iapetus suture in Ireland and Britain. Journal of the Geological Society, London, v.148, 869-880. [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, A. & Johnston, J. D. (1992). Structural constraints on closure geometry across the Iapetus suture in eastern Ireland. Journal of the Geological Society of London, v.149, 65 - 74. [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, J.J. and Lee, M.J., 2003, Cementation, hydrothermal alteration, and Zn-Pb mineralization of carbonate breccias in the Irish Midlands: textural evidence from the Cooleen zone, near Silvermines, County Tipperary - a reply: Economic Geology, v. 98, 194-198.

- Wilkinson, J.J. and Hitzman, M.W., 2015, The Irish Zn-Pb Orefield: The View from 2014, in: Archibald, S.M. and Piercey, S.J., eds., Current perspectives on zinc deposits: Dublin, Irish Association of Economic Geology, Special Publication, p. 59-72.

- Wilkinson, J.J., Eyre, S.L., and Boyce, A.J., 2005, Ore-forming processes in Irish-type carbonate-hosted Zn–Pb deposits: evidence from mineralogy, chemistry, and isotopic composition of sulfides at the Lisheen Mine. Economic Geology, v. 100, 63–86.

- Wynne, A.B. and Kane, G.H., 1861, Memoir to accompany 1” Sheet No. 154, Mem. Geol. Surv. Ireland, 52p.

- Zakrzewski, M.A., 1989, Members of the freibergite-argentotennantite series and associated minerals from Silvermines, County Tipperary, Ireland: Mineralogical Magazine, June 1989, v. 53, p. 293-298.

- Zhuravkova, T.V., Palyanova, G.A. and Kravtsova, R.V., 2015, Physicochemical formation conditions of silver sulfoselenides at the Rogovik deposit, Northeastern Russia: Geology of Ore Deposits, V. 57, p 313–330.

Figure 1.

Geological map of Ireland showing distribution of principal Zn, Pb (Cu,Ag,Ba) deposits in lower Carboniferous limestones (after the Geological Survey of Ireland) and the location of Silvermines. Approx. Carboniferous basin locations after Strogen et al. (1996).

Figure 1.

Geological map of Ireland showing distribution of principal Zn, Pb (Cu,Ag,Ba) deposits in lower Carboniferous limestones (after the Geological Survey of Ireland) and the location of Silvermines. Approx. Carboniferous basin locations after Strogen et al. (1996).

Figure 2.

Diagrammatic stratigraphic column through the Lower Carboniferous of Central Ireland (after Andrew, 2023).

Figure 2.

Diagrammatic stratigraphic column through the Lower Carboniferous of Central Ireland (after Andrew, 2023).

Figure 3.

A). Plan of the 20th Century mine workings at Silvermines and location of the 4611-Room. B). Section 42550E facing west showing principal ore horizon geology and position of 4611 Room.

Figure 3.

A). Plan of the 20th Century mine workings at Silvermines and location of the 4611-Room. B). Section 42550E facing west showing principal ore horizon geology and position of 4611 Room.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram showing a compilation of underground observations and channel sample assays of the silver pod in 4611 Room. (drawn to scale from contemporary underground notebooks). Locations shown *4A to *4G refer to approximate locations of samples shown in

Figure 6.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram showing a compilation of underground observations and channel sample assays of the silver pod in 4611 Room. (drawn to scale from contemporary underground notebooks). Locations shown *4A to *4G refer to approximate locations of samples shown in

Figure 6.

Figure 5.

Isometric plot of three sections across the 4611 Room part of the B-Zone showing mine workings.

Figure 5.

Isometric plot of three sections across the 4611 Room part of the B-Zone showing mine workings.

Figure 6.

Photographs of samples from the 4611 Room silver pod. A). Large sample of massive sulfides comprising pyrite, and dark gray mixed silver sulfosalts, argyrodite and gersdorffite. Intergrown with bladed white barite in upper segment. B) Large sample of dark massive sulfides comprising galena, sphalerite, argyrodite, tetrahedrite and other silver sulfosalts with an expected silver content of > 5% Ag enveloping a pyrite dominated clast. C) Mass of argyrodite and argentite/acanthite with argentian tetrahedrite. D) White crystalline barite. E) White barite with a bleb of ruby silver. F) Brownish barite and a mass of black argyrodite enveloped by radial crystalline white barite. G) White barite showing different crosscutting fabrics with crystalline masses of silver sulfosalts in darker bands.

Figure 6.

Photographs of samples from the 4611 Room silver pod. A). Large sample of massive sulfides comprising pyrite, and dark gray mixed silver sulfosalts, argyrodite and gersdorffite. Intergrown with bladed white barite in upper segment. B) Large sample of dark massive sulfides comprising galena, sphalerite, argyrodite, tetrahedrite and other silver sulfosalts with an expected silver content of > 5% Ag enveloping a pyrite dominated clast. C) Mass of argyrodite and argentite/acanthite with argentian tetrahedrite. D) White crystalline barite. E) White barite with a bleb of ruby silver. F) Brownish barite and a mass of black argyrodite enveloped by radial crystalline white barite. G) White barite showing different crosscutting fabrics with crystalline masses of silver sulfosalts in darker bands.

Figure 7.

Contoured silver grades from underground channel sampling within the 4611 Room pod, the location of the sulfide infilled pipe and the crosscutting veinlets swarm.

Figure 7.

Contoured silver grades from underground channel sampling within the 4611 Room pod, the location of the sulfide infilled pipe and the crosscutting veinlets swarm.

Figure 8.

Analytical data for argyrodite and ruby silvers (proustite – pyrargyrite) plotted as ternary Ag-Ge-S and Sb-As-S plots respectively from the 4611 Room pod. Analytical data from Pattrick (1981 and Zakrzewski (1989) is tabulated in

Table 1. Theoretical compositions shown by red triangles.

Figure 8.

Analytical data for argyrodite and ruby silvers (proustite – pyrargyrite) plotted as ternary Ag-Ge-S and Sb-As-S plots respectively from the 4611 Room pod. Analytical data from Pattrick (1981 and Zakrzewski (1989) is tabulated in

Table 1. Theoretical compositions shown by red triangles.

Figure 9.

Simplified general paragenetic diagram of the 4611 Pod mineralization.,.

Figure 9.

Simplified general paragenetic diagram of the 4611 Pod mineralization.,.

Figure 10.

Diagrams to show the apparent paragenesis derived from polished section analyses showing A) the increase in silver and B) reduction in antimony in the sequential species. Analytical data from Pattrick (1981 and Zakrzewski (1989).

Figure 10.

Diagrams to show the apparent paragenesis derived from polished section analyses showing A) the increase in silver and B) reduction in antimony in the sequential species. Analytical data from Pattrick (1981 and Zakrzewski (1989).

Figure 11.

A) Pb to Zn ratios for the B-Zone area. B) Identical Pb to Zn ratio plot showing the outline of the >4% Pb+Zn orebody and significant structures. Note the correlation between high Pb ratios and the principal B Fault defining the southern boundary to the orebody. Data from surface and underground diamond drilling intercepts.

Figure 11.

A) Pb to Zn ratios for the B-Zone area. B) Identical Pb to Zn ratio plot showing the outline of the >4% Pb+Zn orebody and significant structures. Note the correlation between high Pb ratios and the principal B Fault defining the southern boundary to the orebody. Data from surface and underground diamond drilling intercepts.

Table 1.

Analytical data for argyrodite and ruby silvers (proustite – pyrargyrite) from the 4611 Room pod. Analytical data from Pattrick (1981) and Zakrzewski (1989). See ternary plots in

Figure 8.

Table 1.

Analytical data for argyrodite and ruby silvers (proustite – pyrargyrite) from the 4611 Room pod. Analytical data from Pattrick (1981) and Zakrzewski (1989). See ternary plots in

Figure 8.

| Argyrodite |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Ag |

Ge |

S |

Total |

|

Ag/Ge |

| |

SVF 1Z |

77.34 |

6.50 |

16.26 |

100.1 |

|

11.9 |

| |

SVF 1Y |

82.62 |

5.25 |

13.16 |

101.3 |

|

15.7 |

| |

SVF lX |

80.87 |

4.67 |

12.19 |

97.71 |

|

17.3 |

| |

SVF 1U |

79.83 |

5.04 |

13.41 |

98.28 |

|

15.8 |

| |

SVF 1V |

80.19 |

5.46 |

13.86 |

99.51 |

|

14.7 |

| |

SVF 1U |

81.71 |

2.81 |

11.49 |

96.01 |

|

29.1 |

| |

SVF 1V |

77.05 |

6.28 |

17.19 |

100.52 |

|

12.3 |

| |

SVF 1T |

82.38 |

1.73 |

12.15 |

96.26 |

|

47.6 |

| Ideal Composition |

76.51 |

6.44 |

17.05 |

100.00 |

|

11.9 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Proustite - Pyrargyrite |

| |

Ag |

Sb |

As |

S |

Total |

|

As/(As+Sb) |

| SVF 1D |

66.78 |

2.51 |

11.86 |

18.07 |

99.22 |

|

0.83 |

| SVF lE |

65.74 |

3.57 |

11.39 |

17.85 |

98.55 |

|

0.76 |

| SVF IF |

66.24 |

2.56 |

12.38 |

17.88 |

99.06 |

|

0.83 |

| SVF 1G |

66.39 |

2.38 |

12.01 |

18.06 |

98.84 |

|

0.83 |

| W6 CD |

62.66 |

17.34 |

3.19 |

17.05 |

100.24 |

|

0.16 |

| W6 CA |

61.41 |

18.11 |

2.31 |

16.65 |

98.48 |

|

0.11 |

| SVF 1ZC |

64.79 |

6.29 |

9.84 |

17.84 |

98.76 |

|

0.61 |

| SVF 1ZD |

65.06 |

4.87 |

10.64 |

17.97 |

98.54 |

|

0.69 |

| SVF Z1Z |

66.75 |

5.17 |

10.84 |

18.02 |

100.78 |

|

0.68 |

| SVF Z1Y |

65.92 |

5.45 |

9.62 |

18.22 |

99.21 |

|

0.64 |

| SVF Z1X |

67.06 |

4.89 |

10.31 |

18.19 |

100.45 |

|

0.68 |

| SVF Z1Y |

67.12 |

4.59 |

10.44 |

18.19 |

100.34 |

|

0.69 |

| SVF Z1T |

67.23 |

4.71 |

10.06 |

18.00 |

100.00 |

|

0.68 |

| SVF Z1S |

66.97 |

4.67 |

10.02 |

17.91 |

99.57 |

|

0.68 |

| Zak 11 |

61.10 |

11.00 |

7.80 |

18.30 |

98.20 |

|

0.41 |

| Zak 12 |

61.50 |

10.90 |

8.10 |

18.50 |

99.00 |

|

0.43 |

| Zak 13 |

61.40 |

11.20 |

8.20 |

18.60 |

99.40 |

|

0.42 |

| Ideal Composition |

65.42 |

0 |

15.14 |

19.44 |

100.00 |

|

|

Table 2.

Analytical data for diaphorite, geochronite, boulangerite, tetrahedrite, fine grained intergrowths of gersdorffite, geochronite and galena and gersdorffite. Analytical data from Pattrick (1981) and Zakrzewski (1989).

Table 2.

Analytical data for diaphorite, geochronite, boulangerite, tetrahedrite, fine grained intergrowths of gersdorffite, geochronite and galena and gersdorffite. Analytical data from Pattrick (1981) and Zakrzewski (1989).

| Diaphorite |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Cu |

Ag |

Pb |

Sb |

S |

Total |

| |

SF 5D |

0.59 |

24.81 |

30.92 |

26.91 |

17.69 |

100.82 |

| |

SF 5F |

0.58 |

24.62 |

31.58 |

26.60 |

17.69 |

101.07 |

| |

W6CC |

0 |

25.03 |

29.43 |

26.76 |

18.33 |

99.55 |

| |

W6CB |

0 |

24.86 |

29.63 |

26.18 |

18.31 |

98.98 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Geochronite |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Pb |

Sb |

As |

S |

Total |

| |

SVF 1H |

69.26 |

6.39 |

5.81 |

16.67 |

98.13 |

| |

SVF 1K |

68.31 |

6.48 |

5.71 |

17.63 |

98.13 |

| |

SVF 1L |

68.31 |

6.70 |

5.67 |

18.08 |

98.76 |

| |

Zak 8 |

69.40 |

7.70 |

5.50 |

17.20 |

99.80 |

| |

Zak 9 |

70.50 |

6.90 |

6.00 |

17.20 |

100.60 |

| |

Zak 10 |

70.20 |

6.70 |

5.90 |

17.30 |

100.10 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Boulangerite |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Ag |

Zn |

Pb |

Sb |

As |

S |

Total |

| |

SVF5 B1 |

0.33 |

0 |

58.30 |

24.75 |

0.20 |

17.08 |

100.33 |

| |

SVF5 B2 |

0.93 |

0 |

58.03 |

24.15 |

0.22 |

16.67 |

99.07 |

| |

SVF5 B3 |

1.27 |

0 |

58.10 |

23.90 |

0.28 |

16.45 |

98.73 |

| |

SVF5 E1 |

0.42 |

0 |

58.34 |

24.51 |

0.24 |

17.33 |

100.42 |

| |

SVF5 E2 |

0.25 |

0 |

58.54 |

24.54 |

0.00 |

17.17 |

100.25 |

| |

SVF5 H |

0.63 |

0 |

57.86 |

25.15 |

0.20 |

17.42 |

100.63 |

| |

SVF5 L |

2.98 |

0.89 |

55.79 |

25.10 |

0.00 |

16.58 |

98.36 |

| |

SVF5 L |

2.91 |

0.70 |

55.23 |

24.38 |

0.00 |

17.14 |

97.45 |

| |

W6A C |

0.89 |

0.00 |

56.58 |

24.12 |

0.93 |

17.48 |

99.11 |

| |

W6A B |

0.47 |

0 |

57.13 |

24.94 |

0.68 |

17.72 |

100.47 |

| |

W9B A |

0.96 |

0 |

56.07 |

24.62 |

0.37 |

17.98 |

99.04 |

| |

SVF5 Z |

1.80 |

0 |

56.17 |

24.73 |

0.31 |

16.99 |

98.20 |

| |

SVF5 Y |

1.02 |

0 |

56.34 |

24.75 |

0.27 |

17.62 |

98.98 |

| |

SVF5 X |

1.45 |

0 |

56.17 |

24.64 |

0.29 |

17.45 |

98.55 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Tetrahedrite |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Cu |

Ag |

Zn |

Fe |

Sb |

As |

S |

Total |

| |

SVF IS |

18.68 |

26.5 |

4.36 |

2.55 |

23.70 |

2.42 |

21.37 |

99.58 |

| |

Zak 1 |

23.30 |

20.60 |

4.04 |

3.54 |

14.90 |

9.20 |

23.10 |

98.68 |

| |

Zak 2 |

22.90 |

22.00 |

5.57 |

3.02 |

14.60 |

8.60 |

23.30 |

99.99 |

| |

Zak 3 |

23.90 |

21.10 |

4.79 |

2.88 |

14.90 |

8.30 |

23.40 |

99.27 |

| |

Zak 4 |

22.10 |

23.90 |

5.05 |

3.01 |

14.70 |

8.30 |

22.70 |

99.76 |

| |

Zak 5 |

22.60 |

22.50 |

4.22 |

2.83 |

14.70 |

9.10 |

22.90 |

98.85 |

| |

Zak 6 |

37.50 |

2.90 |

5.00 |

2.43 |

22.40 |

4.90 |

24.40 |

99.53 |

| |

Zak 7 |

40.00 |

1.70 |

4.93 |

2.87 |

13.30 |

11.20 |

26.80 |

100.80 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Intergrowth Gersdorffite, Geocronite and Galena |

| |

|

Ag |

Fe |

Ni |

Pb |

As |

Sb |

S |

Total |

| |

SF 1ZL |

0.86 |

3.20 |

12.61 |

45.79 |

26.00 |

0.00 |

11.06 |

99.52 |

| |

SF 1ZM |

0.88 |

3.76 |

13.35 |

44.58 |

27.84 |

0.84 |

12.12 |

103.37 |

| |

SF 1ZN |

0.81 |

4.48 |

14.28 |

36.76 |

29.88 |

0.00 |

12.95 |

99.16 |

| |

SF 1Z P |

0.57 |

7.15 |

14.09 |

39.61 |

28.58 |

0.00 |

14.64 |

104.64 |

| |

Zak 22 |

0.00 |

1.35 |

3.00 |

60.40 |

11.60 |

6.30 |

16.90 |

99.55 |

| |

Zak 23 |

0.05 |

1.89 |

5.00 |

68.80 |

9.50 |

0.20 |

14.10 |

99.54 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Gersdorffite |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Fe |

Ni |

Cd |

As |

S |

Total |

| |

SVF 1ZA. |

16.60 |

18.99 |

0.42 |

38.77 |

24.21 |

98.99 |

| |

SVF 1ZB |

15.09 |

21.06 |

0 |

41.56 |

22.67 |

100.38 |

| |

SVF lZW |

14.32 |

22.03 |

0 |

45.35 |

19.92 |

101.62 |

| |

SVF 1ZU |

14.07 |

22.29 |

0 |

45.63 |

19.20 |

101.19 |

| |

Zak 14 |

14.30 |

19.50 |

0 |

43.50 |

20.20 |

97.50 |

| |

Zak 15 |

8.60 |

25.90 |

0 |

45.60 |

19.50 |

99.60 |

| |

Zak 16 |

12.60 |

21.70 |

0 |

43.50 |

19.90 |

97.70 |

|