1. Introduction

Prenatal detection of congenital anomalies is an important goal of obstetrical ultrasound examination. The diagnosis of an anomaly has profound implications for counseling about prognosis and for guiding decisions about prenatal care, fetal surveillance, and delivery timing, location, and method.

To maximize prenatal detection of anomalies, standards from the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine [

1,

2] specify 52 required views for detailed fetal anatomy ultrasound examination in the 2

nd or 3

rd trimester of pregnancy. It is often challenging to obtain all the required views. Prior studies have reported that the anatomy exam is incomplete in 4-70% of patients [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. There are several reasons why skilled examiners might be unable to obtain a complete examination, including unfavorable fetal position, early gestational age, maternal obesity, maternal abdominal wall scarring (e.g., prior cesarean delivery), or insufficient time allotted to complete the exam [

3,

4,

6,

7,

9,

10,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. Moreover, examiners may have variable skill-levels for the evaluation of some structures.

Various professional organizations recommend systematic quality review to assure the accuracy of obstetrical ultrasound diagnoses [

18,

19,

20,

21]. Because ultrasound is an imaging modality, quality review must ultimately involve an examination of images. However, image auditing is time consuming, labor intensive, and somewhat subjective. We recently presented quantitative methods for quality review of fetal biometric measurements [

22] and the review of the accuracy of fetal weight estimates [

23]. We showed how image audits could be focused on sonographers or physicians whose measurements varied from the measurements of their peers, thereby saving the time and expense of auditing those whose measurements fell within the expected range. If examiners vary in the accuracy of their biometric measurements, it seems likely that they might also vary in their rate of obtaining a complete fetal anatomy exam.

The objective of the present study was to develop and demonstrate quantitative methods to assess rate of incomplete fetal anatomy exams for an ultrasound practice overall and for individual sonographers and physicians within a practice.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Desing and Setting

A retrospective quality review was undertaken for the cohort of ultrasound exams performed from January through December 2024 at seven referral-based maternal–fetal medicine (MFM) practices affiliated with Pediatrix Medical Group (Sunrise, FL, USA). During the study period, the practices used GE Voluson (GE Healthcare, Wauwatosa, WI, USA) and Philips Affiniti (Philips Ultrasound LLC, Bothell, WA, USA) ultrasound machines with variable-frequency curvilinear transducers (2 to 9 mHz as needed to optimize imaging). The practices used GE Viewpoint software (Version 6) to generate reports and store images and metadata. Sonographers were certified by the American Registry for Diagnostic Medical Sonography. Interpreting physicians were board-certified or board-eligible MFM specialists.

Before we started the study, the Western Institutional Review Board (WIRB) determined that quality review of existing ultrasound data was not considered human subjects research and therefore determined that the study was Exempt.

2.2. Data Extraction, Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Using the Viewpoint query tool, we extracted data for all ultrasound exams meeting these eligibility criteria: singleton pregnancy, detailed fetal anatomy exam using Current Procedural Terminology code 76811 during 2024, fetal cardiac activity present, exam finalized with signed report in Viewpoint. Data were exported from Viewpoint to a comma-separated value file (.CSV format), which was converted into a spreadsheet file (.XLSX format) and imported into Stata statistical software (version BE/18.0, Statacorp, College Station, TX, USA) for analysis.

The extracted data included the required elements of the fetal anatomy survey, an exam identification number, a person identification number, indications for the exam, exam date, patient date of birth (DOB), estimated due date (EDD) based on best obstetrical estimate (typically following consensus guidelines [

25]), sonographer name, and reading physician name. The person identification number was used to identify the first exam for each person; for persons with more than one eligible exam, we kept only the first and excluded any subsequent exam. The EDD was used to calculate gestational age (GA) on the day of the exam. GA is expressed as a decimal fraction rounded to 1 significant digit (e.g., 18 weeks + 4 days is expressed as 18.6 weeks and 23 weeks + 6 days is expressed as 23.9 weeks). The DOB was used to calculate maternal age. Advanced maternal age was defined as age ≥35 years on the EDD. After these calculations and exclusions, the person number, DOB, and EDD were deleted to protect patient anonymity. From the indications, we determined whether there was notation of prior cesarean and whether there was notation of maternal obesity, which was categorized by maternal body mass index (BMI).

2.3. Definitions of Inadequate Views and Incomplete Examination

For each element of the anatomy survey, a text description of the findings was entered in Viewpoint by the sonographer or reading physician when creating the ultrasound report. To simplify data entry, Viewpoint has an option to select “all normal” which initially categorizes every item as normal. Then each entry is modified, if needed, by selecting a different word or phrase from a pull-down list. For analysis, we recoded the entries to fit into one of three categories:

Normal if item was entered as normal, previously documented, seen, or visualized;

Abnormal if entered as abnormal, soft marker seen, or details;

Inadequate if entered as suboptimal, not seen, or not examined or if left blank.

Fetal hands, feet, and lungs have separate entries in Viewpoint for the right and left side. These were each combined into a single element coded as normal if both sides were normal, abnormal if either side was abnormal, and inadequate otherwise. Superior and inferior vena cava views are separate entries in Viewpoint and were similarly combined into a single element.

We defined a fetal anatomy survey as incomplete if there were any items coded as inadequate among the 36 specific elements of fetal anatomy listed in the AIUM Detailed 2

nd Trimester OB imaging checklist [

2]. The checklist also contains 16 other items that we did not consider in the definition of a complete fetal anatomy survey: 2 items of maternal anatomy (uterus-and-cervix, adnexal structures); 6 placental or fetal findings that are not fetal anatomy

per se (placental location, placental cord insertion, fetal number and presentation, amniotic fluid assessment, fetal heart rate, placental vasculature if accessory lobe); 3 fetal anatomy findings for which there is not a corresponding field in Viewpoint (position and architecture of legs and arms, shape and curvature of spine; integrity of spine and overlying tissue); and 5 fetal measurements (head circumference [HC] or biparietal diameter [BPD], abdominal circumference [AC], femur length [FL], nasal bone if GA 15-22 weeks, and nuchal thickness if GA 16-20 weeks). Though not considered in defining whether an anatomy survey was complete or incomplete, we analyzed separately whether the 5 specified fetal measurements were recorded.

2.4. Statistical Analyses

Preliminary exploration was performed on data pooled from all practices combined. We plotted the percentage of inadequate views for each exam element as a function of GA for the entire data set (GA range 14 to 40 weeks). Subsequent analysis was restricted to GA 18.0 to 23.9 weeks for several reasons. First, several organizations recommend that the optimal time for the anatomy survey is between about 18-22 weeks GA for most patients [

1,

25,

26,

27,

28]. Second, patients seen at 24 weeks GA or later are more likely to have been referred for known or suspected abnormalities rather than simply for screening. Third, 75% of all exams were performed within this range of GAs, so exclusion of earlier or later exams would not seriously degrade the sample size for quality review. Finally, for most anatomy elements, the rate of inadequate views was lowest and fairly constant in this GA range.

For exams from 18.0 to 23.9 weeks GA, we tabulated the rate of normal, abnormal and inadequate views for each of the 36 required anatomy elements in all 7 practices combined. In the pooled data, we evaluated the associations between the rate of incomplete exams and maternal obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2), prior cesarean, advanced maternal age (≥35 years at the EDD), and GA <19 weeks using chi squared test and univariable and multivariable logistic regression.

Next, we stratified the data by practice and tabulated the rate of incomplete exams, rate of exams with 1 or more abnormal views, the number of inadequate views in incomplete exams, and the rates of missing fetal biometry measurements. Between-practice differences were assessed with chi-squared test, Kruskal-Wallis test, and logistic regression adjusting for maternal obesity, prior cesarean, maternal age, and GA <19 weeks.

Finally, we selected the practice with the highest rate of incomplete exams to demonstrate examples of individual-level comparisons between selected sonographers and between selected physicians.

Two-tailed p-values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

For practices that wish to adopt these methods using their own data, Supplemental Files 1-4 provide a spreadsheet file with sample data (.XLSX format), Stata “do-file” analysis scripts (Stata .DO format), and a text file of the scripts readable by those who do not have Stata (.DOCX format).

3. Results

3.1. Included Exams, Gestational Age Considerations

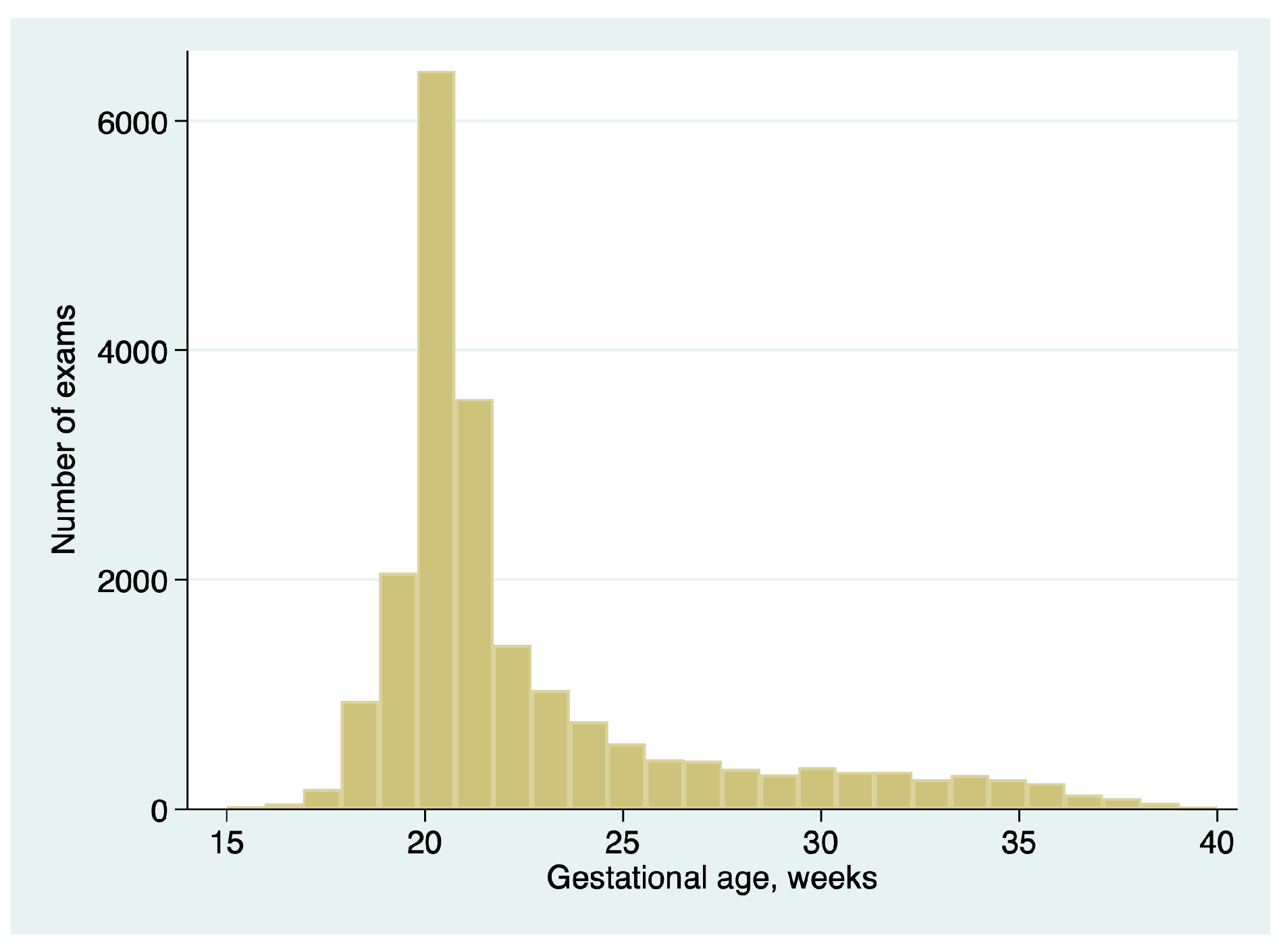

A total of 20,897 exams in 20,897 unique patients from the 7 practices met the inclusion criteria. GA ranged from 14.0 to 39.7 weeks of gestation (median 21.0 weeks, interquartile range 20.0 to 23.6 weeks). The distribution of gestational ages is summarized in

Figure 1.

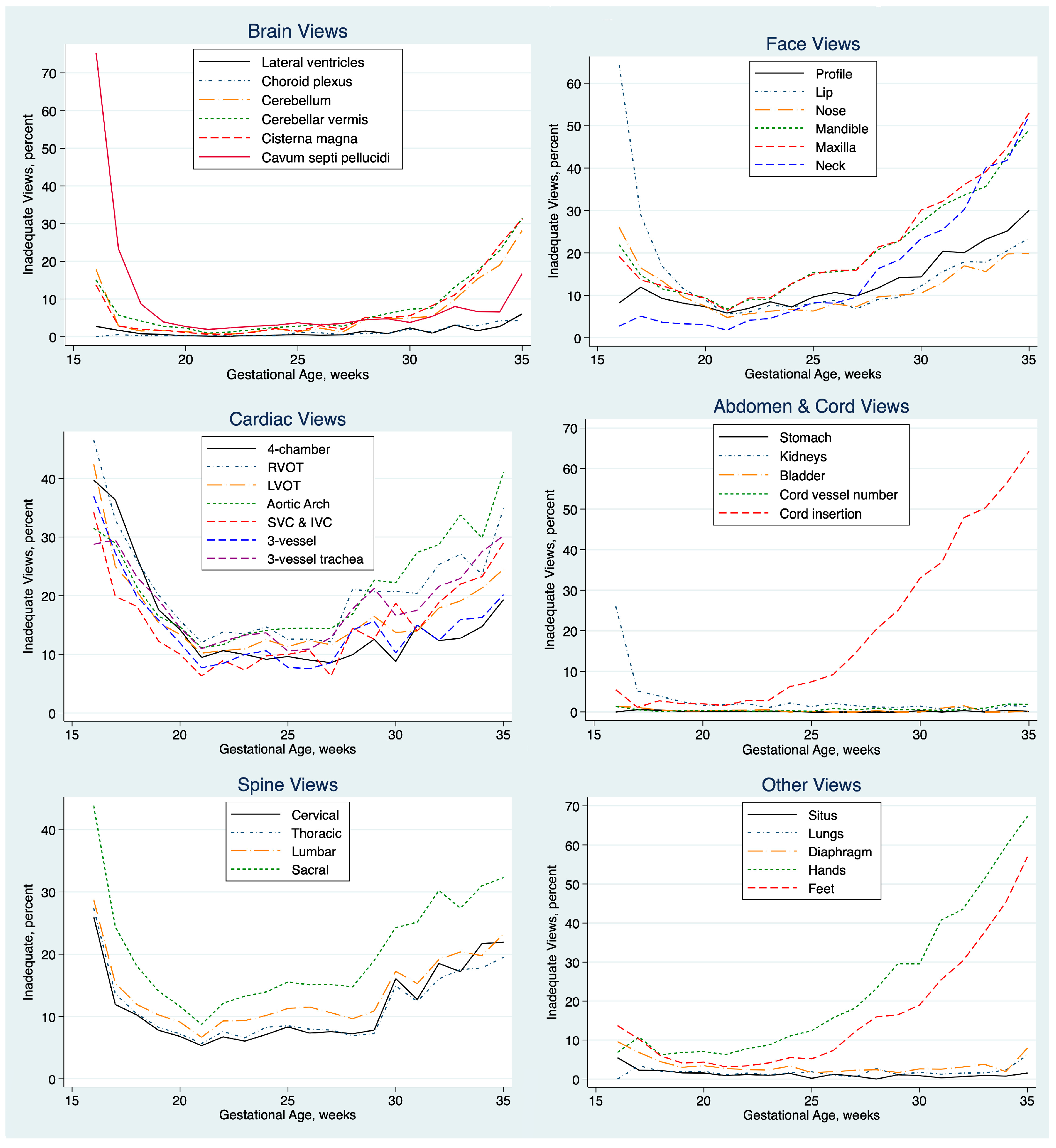

The percentage of exams with inadequate views of specific elements of the anatomy varied with GA, as shown in

Figure 2. For most elements, the percentage was lowest and fairly constant between 18 and about 28 weeks GA. We focused our quality review on exams from 18.0 to 23.9 weeks of gestation for all subsequent analyses.

The percentage of normal, abnormal, and inadequate views for each element of the anatomy exam at 18.0 to 23.9 weeks GA is shown in

Table 1. The percentage of inadequate views varied by anatomical region, tending to be low for fetal brain, lungs, and abdomen and high for fetal heart, face, and spine views.

3.2. Clinical Factors Associated with Incomplete Exams

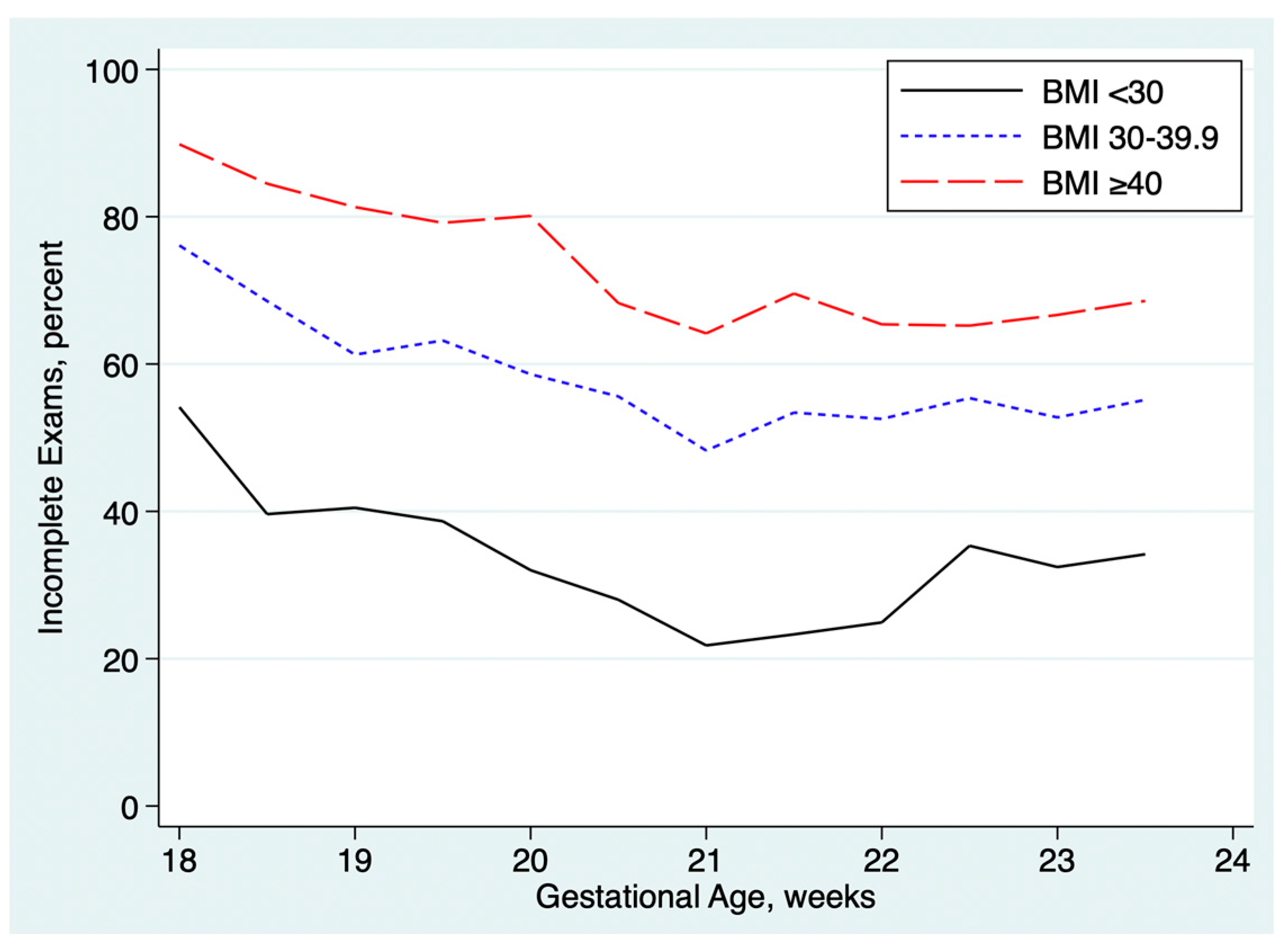

Table 2 summarizes the associations between incomplete exams and maternal obesity, prior cesarean delivery, advanced maternal age, and gestational age at the time of the anatomy ultrasound exam. The rate of incomplete exams was higher in obese patients and rose with increasing BMI, as shown in

Figure 3. Exams performed at <18.0 to 18.9 weeks GA were about twice as likely to be incomplete as exams performed at ≥19.0 weeks GA. Prior cesarean was associated with a small but statistically significant increased rate of incomplete exams. Advanced maternal age was associated with a slightly lower rate of incomplete exams, both in univariable analysis and after multivariable adjustment for the other factors.

3.3. Practice-Level Variation in Exam Completeness.

The results stratified by practice are summarized in

Table 3. There was wide variation between practices in the percentage of exams that were incomplete, ranging from 1% in one practice to 50% or more in 2 practices. There was also wide variation in the percent of exams in which an abnormality was identified, ranging from 2% to 10.0%.

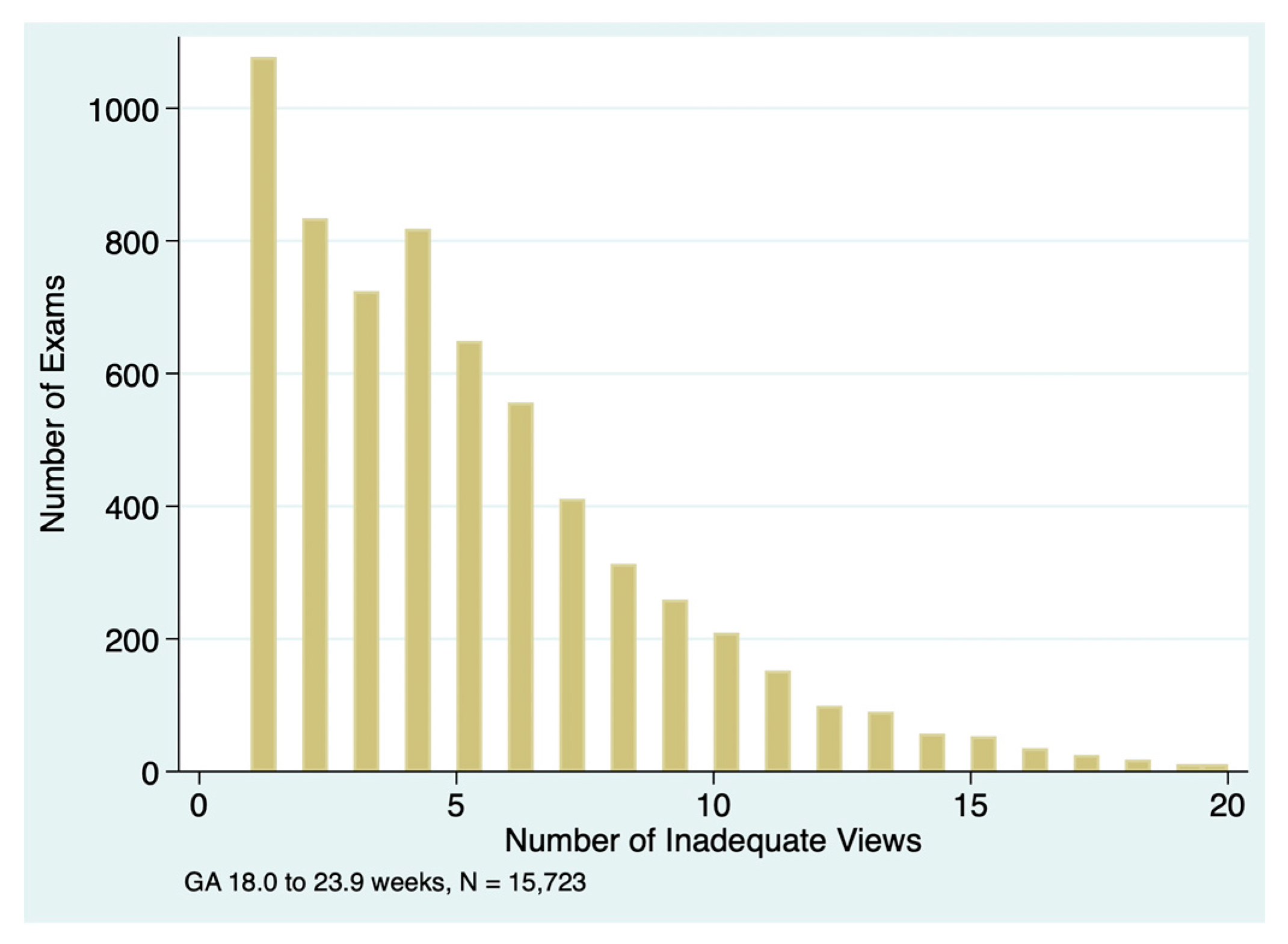

If the anatomy exam was incomplete, there were often multiple inadequate views, as illustrated in

Figure 4. The median number of inadequate views was 4 (IQR 2 to 7) in incomplete exams for all practices combined, with significant variations between practices as shown in

Table 3. In exams with only one inadequate view, the most common elements coded as inadequate were aortic arch (n=135), venae cavae (n=95), 3-vessel-trachea view (n=63), and profile (n=41).

The basic fetal biometry measurements (BPD or HC, AC, FL) were recorded in virtually all exams, with only 4 missing measurements in 20,897 exams (0.02%), as shown in

Table 3.

Nuchal fold measurement was not recorded in 2.8% of exams at ≤20 weeks GA, with significant variation between practices (ranging from 0 to 9.4% missing measurements). This measurement was missing in 20.1% of exams when the neck views was inadequate (35 of 174) versus 2.1% when neck view was adequate (109 of 4,995, p<0.001, Fisher’s exact text) .

Nasal bone measurement was not recorded in 38.4% of exams at ≤22 weeks GA, again with significant variation between practices (ranging from 9.9% to 100% missing measurements). This measurement was missing in 85.3% of exams when the profile view was recorded as inadequate (840 of 985) versus 34.8% when profile was adequate (4,405 of 12,644, p < 0.001, Fisher’s exact test).

There was no evident relationship between the practice-level percentage of incomplete anatomy exams, missing nuchal fold measurement, or missing nasal bone measurements. For example, Practice 1 had the lowest rate of incomplete anatomy but the highest rate of missing nuchal fold and nasal bone measurements. Practice 7 had the second lowest rate incomplete anatomy exams but one of the highest rates of missing nasal bone measurements and not a single case of missing nuchal fold measurement.

3.4. Sonographer-Level Variation in Exam Completeness

Table 4 summarizes results from 10 of the 42 sonographers from a single practice. This practice and these sonographers were hand-selected to illustrate several types of quality issues that can be explored using our methods; they are not a random sample and are not intended to be comprehensive. Individual sonographers’ rates of incomplete exams varied from 13.6% to 83.2%. Each sonographer’s rate of incomplete exams was compared to the rate of the rest of the practice using logistic regression adjusting for the factors in

Table 3. In this analysis, sonographers 1 through 3 had significantly lower rates of incomplete exams than the rest of the practice and sonographers 6 through 10 had significantly higher rates. There was also significant between-sonographer variation in the number inadequate views in incomplete exams, with medians ranging from 2 to 5 inadequate views per incomplete exam.

Measurements of nuchal fold thickness were missing in 0 to 16% of exams, a significant between-sonographer variation. There was no evident relationship between a sonographer’s rate of incomplete anatomy exams and the rate of missing nuchal fold measurements. For example, sonographers 8 and 10 had two of the highest rates of incomplete anatomy exams, but no missing nuchal fold measurements. In contrast, sonographers 6 and 7 had intermediate rates of incomplete anatomy exams but the highest rates of missing nuchal fold measurement.

Measurements of nose bone length were missing in 4.9 to 99.8% of exams, a significant between-sonographer variation. There was some tendency for sonographers with high rates of incomplete anatomy exams to also have high rates of missing nose bone measurement. For example, sonographers 9 and 10 had the highest rate of incomplete anatomy exams and two of the highest rates of missing nose bone measurements; sonographer 1 had the lowest rate of both incomplete anatomy exams and missing nose bone measurement. Sonographer 5 was an exception to this general trend, with an intermediate rate of incomplete anatomy exams but a high rate of missing nose bone measurement. There was no obvious relationship between the rate of missing nuchal fold measurement and the rate of missing nose bone measurement.

3.5. Physicain-Level Variation in Exam Completeness

Table 5 summarizes results from 7 of the 14 physicians from the same practice as the sonographers in

Table 4. As with

Table 4, these physicians were hand-picked to illustrate some of the quality issues that can be explored with our methods. Similar to the results for the sonographers, there were significant between-physician differences in the rate of incomplete anatomy exams and the rates of missing measurements for nuchal fold and nose bone.

3.6. Focused Review of Inadequate Elements by Selected Examiners

To explore which elements of the anatomy survey were often classified as inadequate, we focused on the two sonographers in

Table 4 with the highest rate of incomplete exams. This practice has multiple offices across a large metropolitan area and the sonographers and physicians work in select offices preferentially. As a result, each sonographer tends to work with only a few physicians and vice versa. For example, 91% of exams by Sonographer 10 were signed by Physician 7 and 63% of exams signed by Physician 7 were performed by Sonographer 10. Similarly, 90% of exams by Sonographer 9 were signed by Physician 2 and 40% of exams signed by Physician 2 were performed by Sonographer 9. Thus, in

Table 6, we include rates of inadequate views for Sonographers 9 and 10 and for their most common reading physicians (Physicians 7 and 2, respectively).

Inspection of

Table 6 reveals that both Sonographer 10 and Physician 7 had inadequate views of the fetal hands in >60% of exams, remarkably higher rates than Sonographer 9 and Physician 2 (both <5%). Sonographer 9 had inadequate views of fetal maxilla, mandible, and neck in >40% of exams, substantially higher rates than the other examiners shown.

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal Findings

The rate of incomplete anatomy exams and missing measurements varied widely between practices and between individual examiners within a practice.

Incomplete exams occur because of inadequate views of one or more specific elements of the anatomy. We found that views of fetal cardiac anatomy, face, and spine were inadequate more often than views of the brain, abdominal organs, and cord. This confirms prior reports suggesting that it is often more difficult to obtain adequate images of the heart, face, and spine [

5,

6,

12,

15]. Our finding that incomplete exams were more common with maternal obesity, abdominal scarring associated with prior cesarean delivery, and earlier gestational age also confirms prior reports [

3,

4,

6,

7,

9,

10,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16].

4.2. Clinical Consequences of Incomplete Exams

If the anatomy is incompletely evaluated, it is possible that a congenital anomaly will be missed. For this reason, it is recommended that a repeat examination be performed to reexamine the anatomy views not adequately seen on the initial exam [

16]. A single follow-up exam will usually yield adequate images of the views not seen on the index exam [

5,

7,

9,

12,

14,

15]. It is debatable whether repeated follow-up exams improve completion rates if the anatomy evaluation remains incomplete after the first follow-up [

5,

8,

9,

12,

15,

29,

30]. This is especially problematic with maternal obesity: 11% of patients with BMI >30 kg/m

2 and 25% of patients with BMI >50 kg/m

2 failed to have a complete evaluation of the fetal anatomy by the time of birth despite multiple repeated attempts [

16,

29].

One study found that inadequate views were associated with an increased incidence of congenital anomalies [

12], but this was not confirmed by others [

7,

15]. If an anomaly is found, management options depend on the GA at which the diagnosis is suspected or confirmed. Detection at the earliest possible GA usually provides the most options for confirmatory testing, advanced imaging such as fetal echocardiogram or magnetic resonance imaging, and pregnancy termination.

Even if the anatomy survey is ultimately completed and found to be normal, follow-up exams are inevitably costly to the patient in terms of time and inconvenience and potentially have direct financial costs for patients or payers. Incomplete anatomy exams also cause significant patient anxiety [

11].

4.3. Ideal Rate of Incomplete Exams

There is no benchmark or “gold standard” to establish an ideal rate of incomplete exams. Rates reported in prior studies vary widely, from less than 4% [

5] to 57% [

4], with several studies reporting rates in the range of 10-20% [

7,

8,

9,

11,

14].

When using ultrasound to screen for congenital anomalies, there is an inevitable trade-off between sensitivity and specificity. To maximize sensitivity for detection of anomalies, sonographers or physicians may be unwilling to call a view adequate unless it is very clear. The higher an examiner’s threshold for deciding that a view is adequate, the more likely that examiner is to finish the exam with inadequate views, rendering the exam incomplete and resulting in the recommendation for a follow-up exam. While this will increase sensitivity, it decreases specificity; that is, incomplete exams become non-specific findings, resulting in the need for follow-up exam for many patients with normal fetuses.

Unexplained variation between examiners or between practices can lead to bias and may be an indicator of a quality problem [

31]. Outlier providers or outlier practices, by definition, are those that deviate from the “norm” established by providers or practices whose rate of incomplete exams falls closer to the middle. Closer scrutiny of the adequacy of images may be warranted for these outliers. For example, the 1.3% rate of incomplete exams in Practice 1 may reflect a predisposition to accept as “normal” some images that other examiners might find suboptimal; the low rate of reported abnormal views in this practice reinforces that notion. For Practice 2, on the other hand, the 52.7% rate of incomplete exams may reflect a practice-wide tendency to call views “suboptimal” though other examiners may accept those views as adequate for diagnostic purposes. In the absence of a benchmark, it is not possible to conclude that one approach is better than the other.

On the other hand, there is clearly a quality problem if a high percentage of measurements of nuchal fold or nasal bone are missing. Increased nuchal thickness is one of the strongest sonographic markers of Down syndrome [

32,

33] and is also associated with other chromosomal anomalies [

34,

35,

36,

37]. A short or absent nose bone is associated with Down syndrome, other aneuploidies, and a variety of other anomalies [

32,

38,

39]. We believe these measurements should be obtainable in virtually all exams at ≤22 weeks GA, with occasional exceptions due to fetal position or extremely high maternal BMI.

4.4. Possible Strategies to Reduce the Rate of Incomplete Exams

Exams at GA 18.0 to 18.9 weeks were incomplete about twice as often as exams at GA 19.0 to 23.9 weeks. Although several organizations recommend that the routine anatomy exam be performed at 18-22 weeks [

25,

26,

27,

28], some fetal anatomy elements are difficult to image adequately during week 18. It is noteworthy that Practice 7, which had one of the lowest rates of incomplete exams, performed only 0.6% of their detailed anatomy exams during week 18, compared to 7.1% in the other practices.

We suggest that practices should avoid routinely scheduling the anatomy exam before 19 weeks GA. Occasional exceptions may be warranted in clinical circumstances where an earlier evaluation is needed, such as evaluation of bleeding or suspicion of an anomaly.

For obese patients, we agree with the suggestion that the anatomy exam should usually be scheduled slightly later, at 20-22 weeks GA, to reduce the rate of incomplete exams [

26]. To accomplish this, scheduling staff will need information about patient BMI. Further delay beyond the 20-22 week window is unlikely to reduce the rate of incomplete exams further (

Figure 3) and will decrease management options if an abnormality is found.

Another strategy to reduce the rate of incomplete exams might be to increase the amount of time routinely allotted for a detailed anatomy exam. There is no established benchmark or standard regarding the time that should be allotted, so practices generally set their schedules based on historic precedent. But the number of required views has increased over the past decades, so perhaps the allotted time should be proportionately increased. One study found that increasing the allotted time from 30 minutes to 45 minutes was associated with a decrease in the rate of incomplete exams from 46% to 20% and a significant reduction in the rate of repeat exams to complete the anatomy survey [Ashimi Balogun 2024]. Increasing the scheduled exam time to 60 minutes might reduce the rate even further. For example, Practice 7, which had one of the lowest rates of incomplete exams in our cohort, allots 60 minutes for a routine detailed exam and 70 minutes if a transvaginal cervical length assessment is anticipated because of a prior spontaneous preterm birth.

4.5. Evaluation of Individual-Level Variance

A prior study found that sonographer-level and physician-level variation was responsible for much of the variance in the rate of incomplete anatomy evaluation and the rate of recommendation for repeat examination [

15]. We confirm that there is a large variance between examiners in the rate of incomplete exams.

Without performing a quantitative quality review, sonographers and physicians have no way of knowing how their performance compares to their peers. The practice-wide assessment of exam completion, as illustrated in

Table 4 and

Table 5, provides a high-level overview of individual performance. As with many quality review processes, the initial reaction of many providers is often denial that there is an issue; providers often believe that their patients are at higher risk for incomplete exams for one reason or another. For that reason, we performed a multivariable adjustment for known the known covariates: obesity, prior cesarean, maternal age, and GA <19 weeks. Even after adjustment, statistically significant differences between examiners persisted.

As shown by the examples in

Table 6, a detailed individual assessment of inadequate views may yield insights into elements of the anatomy exam where examiners are uncomfortable and may need additional training or supervision. For example, Sonographer 9 appears to have an issue with views of the maxilla, mandible, and neck.

The high rate of inadequate views of the hands for Sonographer 10 and Physician 7 is more difficult to interpret. It may be that Sonographer 10 is having trouble imaging the hands or it may be that Physician 7 has a low threshold to call hand images inadequate. A clue that the high rate of inadequate hand images was being driven by the physician is that over one-third of Physician 7’s exams were performed by other sonographers, yet the Physician’s overall rate was still >60%, meaning that this physician’s exams had a high rate of inadequate hand views no matter which sonographer performed the exam. An image review may yield further insights.

We suggest that sonographers and physicians should be rotated so that each sonographer has the opportunity to work with multiple physicians and vice versa. Working with different people may help to minimize the development of bad habits.

4.6. Strengths and Limitations

A strength of our quantitative approach is that it provides a broad overview of the performance of an entire practice and of individual personnel. For examiners with a large number of exams, the method is highly sensitive to small between-provider variations, readily identifying outliers for focused review. Once the analysis script is written, the quantitative analysis can be performed rapidly and repeated periodically. For those who wish to use these methods, we have provided a sample spreadsheet with sample data (Supplementary File 1) and sample Stata scripts (Supplementary Files 2 and 3) that will perform the basic analyses for

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6 and generate graphs like

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4.

A limitation is that the analysis is based entirely on findings stated in the reports rather than review of the adequacy of the images. We recommend an audit of images to evaluate outlier personnel, but we believe that a labor-intensive, time-consuming image audit is unlikely to be informative for the majority of examiners whose performance is in line with others in their practice. Further, we believe that a report showing the exam as incomplete likely reflects a truly incomplete exam. Because Viewpoint offers an option to select “all normal” for the anatomy elements, a complete exam is typically the default condition. It requires a deliberate action to convert an element to anything other than normal. This is unlikely to happen unless the sonographer or physician truly finds the view to be abnormal or suboptimal.

Ultimately, the true accuracy of the fetal anatomy exam should be measured by the rate of correct determination of the presence or absence of congenital anomalies at birth or in infancy. But there are serious practical limitations to evaluating accuracy this way. The first limitation is a sample size consideration: Let us assume that the incidence of anomalies is about 4%, and one examiner has a detection rate of 75% of anomalies (or 3% of exams) while another has a detection rate of 25% of anomalies (or 1% of exams), a 3-fold difference in detection rate. To have 80% power for this difference to reach statistical significance at p <0.05, a sample of 769 exams per sonographer would be required. The is more than double the number of exams performed annually by our busiest sonographers. The second limitation is that assessment accuracy of anomaly detection would require considerable effort to obtain newborn data from the several hospitals throughout a wide region where our referring providers deliver their patients. The third limitation is that some anomalies might be diagnosed later in infancy and may not be evident in the newborn hospital record.

4.7. Future Directions – Software Enhancements

Viewpoint and other ultrasound reporting software can be configured to require mandatory responses in many exam fields. It would be useful if nuchal fold and nasal bone measurements could be so configured, thereby greatly reducing the rate of exams missing these measurements. These measurements are only required at a restricted range of GA (16-20 weeks for nuchal fold, 15-22 weeks for nasal bone). Unfortunately, Viewpoint cannot currently be configured to make an entry mandatory only in certain GA ranges. Future versions of the software should allow this.

It would be ideal if software developers would include quality review tools in future versions of their product. Practice-wide and provider specific rates of incomplete exams and inadequate views would be useful if the tools were straightforward to operate. Although our sample data and Stata scripts in the Supplementary Files may save practices the considerable time it would take to develop and debug the analysis routines, there is still time and effort involved in querying the database, downloading the results, exporting to spreadsheets, and importing into Stata. Other quality review tools might also be built into the reporting software, such as a provider-specific quantitative review of fetal biometry measurements and accuracy of estimated fetal weight, as we outlined in prior reports [

22,

23].

Finally, software developers are currently directing considerable effort to develop artificial intelligence (AI) techniques to guide sonographers through the exam and to help physicians determine whether specific views are normal, abnormal, or inadequate. We hypothesize that use of AI will decrease the rate of incomplete exams. This hypothesis needs to be tested as new suites of AI software are introduced.

5. Conclusions

There is considerable variation between practices and between examiners in the rate of incomplete anatomy exams and the rate of missing nuchal fold and nasal bone measurements. For examiners with a high rate of incomplete exams, tabulation of which views are inadequate may help to guide education and quality improvement. Some of our practices and some individuals need a quality improvement effort starting with feedback and education regarding the importance of measuring nuchal fold and nose bone as a standard part of the second trimester anatomy exam.

We believe it is important for every ultrasound practice to perform a quality review such as this. We have demonstrated a method and provided tools to allow practices to perform a similar evaluation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1. File S1: “EXCEL Anatomy & Indications.xlsx”; File S2: “DO-FILE Anatomy Quality Review.do”; File S3: “DO-FILE-Itemrecode.do”; File S4: “WORD version of Stata scripts.docx”.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.A.C., O.A.B, J.V, S.A.; methodology, C.A.C.; software, C.A.C.; validation, O.A.B., JV and S.A.; formal analysis, C.A.C.; investigation, all authors; data curation, C.A.C.; writing—original draft preparation, C.A.C.; writing—review and editing, all authors; visualization, supervision, and project administration, C.A.C.; funding acquisition, none. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was reviewed by the Western Institutional Review Board (WIRB). This quality review study was considered not to be human subjects research and was determined to be Exempt (December 14, 2017).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the Exempt status of the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw datasets presented in this article are not readily available because they include protected patient health information and the names of individual healthcare personnel. As an alternative, we provide a sample dataset in Supplementary File S1 with anonymized patient and personnel identifiers and random jitter added to dates and measurements. The purpose of providing this data is to facilitate the development and debugging of data analysis programs like those provided in Supplementary Files S2 and S3. Requests to access the original datasets should be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The Pediatrix Center for Research, Education, Quality & Safety (CAC) received funds from Sonio, Inc. for providing ultrasound images for training and validation of artificial intelligence software to detect fetal anomalies and enhance exam completeness. No artificial intelligence was used in the present studies or in preparing this manuscript for publication. Sonio had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AC |

Abdominal Circumference (fetal) |

| AIUM |

American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine |

| BMI |

Body Mass Index |

| BPD |

Biparietal Diameter (fetal) |

| DOB |

Date of Birth (maternal) |

| EDD |

Estimated Date of Delivery (the date when gestational age = 40 weeks) |

| FL |

Femur Length (fetal) |

| GA |

Gestational Age |

| HC |

Head Circumference (fetal) |

| IQR |

Interquartile Range |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

References

- American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine. AIUM practice parameter for the performance of standard diagnostic obstetric ultrasound. J. Ultrasound Med. 2024, 43, E20–E32. [Google Scholar]

- Case study submission requirements: detailed 2nd trimester OB (includes OB standard), updated 7/24/24. Available online: https://www.aium.org/docs/default-source/accreditation/case-study-requirements/76811.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Lantz, M.E.; Chisholm, C.A. The preferred timing of second-trimster obstetric sonography based on maternal body mass index. J Ultrasound Med 2004, 1019–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thornburg, L.L.; Miles, K.; Ho, M.; Pressman, E.K. Fetal anatomic evaluation in the overweight and obese gravida. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2009, 33, 670–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padula, F.; Gulino, F.A.; Capriglione, S.; Giorlandino, M.; Cignini, P.; Mastrandrea, M.L.; D’Emidio, L.; Giorlandino, C. What is the rate of incomplete fetal anatomic surveys during a second-trimester scan? Retrospective observational study of 4000 noonobese pregnant women. J Ultrasound Med 2014, 34, 2187–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasko, D.N.; Wood, S.L.; Jenkins, S.M.; Owen, J.; Harper, L.M. Completion and sensitivitry of the second-trimester fetal anatomic survey in obese gravidas. J Ultrasound Med 2016, 35, 2449–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestri, M.T.; Pettker, C.M.; Raney, J.H.; Xu, X.; Ross, J.S. Frequency and importance of incomplete screening fetal anatomic sonography in pregnancy. J Ultrasound Med 2016, 35, 2665–2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, K.; Shainker, S.A.; Modest, A.M.; Spiel, M.H.; Resetkova, N.; Shah, N.; Hacker, M.R. Cost analysis of following up incomplete low-risk fetal anatomy ultrasounds. Birth 2017, 44, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.L.; Owen, J.; Jenkins, S.M.; Harper, L.M. The utility of repeat midtrimester anatomy ultrasound for anomaly detection. Am J Perinatol 35(4), 1346–1351. [CrossRef]

- Simmons, P.M.; Wendel, M.P.; Whittington, J.R.; San Miguel, K.; Ounpraseuth, S.T.; Magann, E.F. Accuracy and completion rate of the fetal anatomic survey in the super obese parturient. J Ultrasound Med 40, 2047-–2051. [CrossRef]

- Gross, M.S.; Ju, H.; Osborne, L.M.; Jelin, E.B.; Sekar, P.; Jelin, A.C. Inteterminate prenatal ultrasounds and maternal anxiety: a prospective cohort study. Matern Child Health J 2021, 25, 802–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, S.A.; O’Connell, K.; Carter, A.; Gravett, M.G.; Dighe, M.; Richardson, M.L.; Dubinsky, T.J. Incidence of fetal anomalies after incomplete anatomic surveys between 16 and 22 weeks. Ultrasound Quarterly 2013, 29, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adekola, H.; Soto, E.; Dai, J.; Lam-Rachlin, J.; Gill, N.; Leon-Peters, J.; Puder, K.; Abramowicz, J.S. Optimal visualization of the fetal four-chamber and outflow tract views with transabdominal ultrasound in the morbidly obese: are we there yet? J Clin Ultrasound 2015, 43, 548–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eastwood, K.-A.; Daly, C.; Hunter, A.; McCance, D.; Young, I.; Holmes, V. The impact of maternal obesity on completion of fetal anomaly screening. J Perinat Med 2017, 45, 1061–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lendrum, T.L.; Shaffer, R.K.; Heyborne, K.D. Repeat anatomic surveys performed for an initial incomplete study: the sonographer and physician factors. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2022, 4, 100567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buskmiller, C.; Huntley, E.; Blackburn, B.; Sanchez, D.; Hernandez-Andrade, E. Completion of fetal anaomy evaluations in women with doy mass index ≥50 kg/m2. J Ultrasound Med 2023, 42, 2839–2844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashimi Balogun, O.; Behnia, F.; Chelliah, A.; Luo, J.; Chauhan, S.P.; Samuel, A. Comprehensive detailed anatomic ultrasound: allotted time of 30 vs 45 minutes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2024, 230, S212–S213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benacerraf BF, Minton KK, Benson CB, Bromley BS, Coley BD, Doubilet PM, Lee W, Maslak SH, Pellerito JS, Perez JJ, et al. Proceedings: Beyond Ultrasound First Forum on improving the quality of ultrasound imaging in obstetrics and gynecology. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018, 218, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Executive summary: Workshop on developing an optimal maternal-fetal medicine ultrasound practice, February 7-8, 2023, cosponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, American Institue of Ultrasound in Medicine, American Registry for Diagnostic Medical Sonography, Internation Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology, Gottesfeld-Hohler Memorial Foundation, and Perinatal Quality Foundation. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2023, 229, B20–4. [Google Scholar]

- American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine. Standards and guidelines for the accreditation of ultrasound practices. June 16, 2020. Available online: https://www.aium.org/resources/official-statements/view/standards-and-guidelines-for-the-accreditation-of-ultrasound-practices (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- American College of Radiology. Available online: https://accreditationsupport.acr.org/support/solutions/articles/11000068451-physician-qa-requirements-ct-mri-nuclear-medicine-pet-ultrasound-revised-9-7-2021- (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Combs, C.A.; Amara, S.; Kline, C.; Ashimi Balogun, O.; Bowman, Z.S. Quantitative approach to quality review of prenatal ultrasound examinations: fetal biometry. J Clin Med 2024, 13, 4860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combs, C.A.; Lee, R.C.; Lee, S.Y.; Amara, S.; Ashimi Balogun, O. Quantitative approach to quality review of prenatal ultrasound examinations: estimated fetal weight and fetal sex. J Clin Med 2024, 13, 6895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologist, American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Methods for Estimating the due date. Committee Opinion number 700. Obstet Gynecol 2017, 129, e150–e154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NHS England. Public health functions to be exercised by NHS England. Service specification no. 17. NHS Fetal anomaly screening programme, November, 2013. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a759b7be5274a545822cd2e/17_nhs_fetal_anomaly.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Reddy UM, Abuhamad AZ, Levine D, Saade GR, for the Fetal Imiging Workshop Invited Participants. Fetal imaging: executive summary of a joint Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Intitue of Child Health and Human Development, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, American College of Radiology, Society for Pediatric Radiology, and Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound Fetal Imaging Workshop. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014, 210(5), 387–397. [Google Scholar]

- Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada. SOGC Clinical practice guideline no. 223 – Content of a complete routine second trimester obstetrical ultrasound examination and report. J Obstet Gynecol Can 2017, 39, d144–e149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISUOG Clinical Standards Committee. ISUOG Practice Guidelines (updated): performance of the routine mid-trimester fetal ultrasound scan. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2022, 59, 840–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendler, I.; Blackwell, S.C.; Bujold, E.; Treadwell, M.C.; Mittal, P.; Sokol, R.J.; Sorokin, Y. Suboptimal second-trimester ultrasonographic visualization of the fetal heat in obese women. Should we repeat the examination? J Ultrasound Med 2005, 24, 1205–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, J.J.; Morgan, J.L.; Twickler, D.M.; McIntire, D.D.; Dashe, J.S. Utility of follow-up standard sonography for fetal anomaly detection. Am J Obstet Gtnecol 2020, 222, 615.e1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Skinner, J.; Bynum, J.; Sutherland, J.; Wennberg, J.E.; Fisher, E.S. Regional variations in diagnostic practices. N Engl J Med 2010, 363, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agathathakleous, M.; Chaveeva, P.; Poon, L.C.Y.; Kosinski, P.; Nicolaides, K.H. Meta-analysis of second-trimester markers for trisomy 21. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2013, 41, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataguiri, M.R.; Junior, E.A.; Silva Bussamra, L.C.; Machado Nardozza, L.M.; Fernandes Moron, A.F. Influence of second-trimester ultrasound markers for Down syndrome in pregnant women of advanced maternal age. J Pregnancy 2014, 2014, 785730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benacerraf, B.R.; Laboda, L.A.; Frigoletto, F.D. Thickened nuchal fold in fetuses not at risk for aneuploidy. Radiol 1992, 184, 239–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Fu, F.; Li, R.; Liu, Z.; Liao, C. Prenatal diagnosis an dpregnancy outcome analysis of thickened nuchal fold in the second trimester. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018, 97, 46. [Google Scholar]

- Kievskaya JK, Shilova NV, Kaniets IV, Kudryavtseva EV, Pyankov DV, Korostelev SA. SNP-based chromosomal microarray analysis for detecting DNA copy number variations in fetuses with a thickened nuchal fold. Sovremennye Tehnologii v Med 2021, 13, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Wu, J.; Liang, D.; Yuan, J.; Wang, J.; Shen, Y.; Lu, J.; Xia, A.; Li, J.; Wu, L. Association analysis between chromosomal abnormalities and fetal ultrasonographic soft markers based on 15,263 fetuses. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2023, 5, 101072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moczulska, H.; Serafin, M.; Wojda, K.; Borowiec, M.; Sieroszewski, P. Fetal nasal bone hypoplasia in the second trimester as a karker of multiple genetic syndromes. J Clin Med 2022, 11, 1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusick, W.; Provenzano, J.; Sullivan, C.A.; Gallousis, F.M.; Rodis, J.F. Fetal nasal bone length in euploid and aneuploid fetuses between 11 and 2o weeks’ gestation. A prospective study. J Ultrasound Med 2024, 23, 1327–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).