Submitted:

15 April 2025

Posted:

16 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. From Ensemble to Point-Forecasts

2.1. Benchmarking

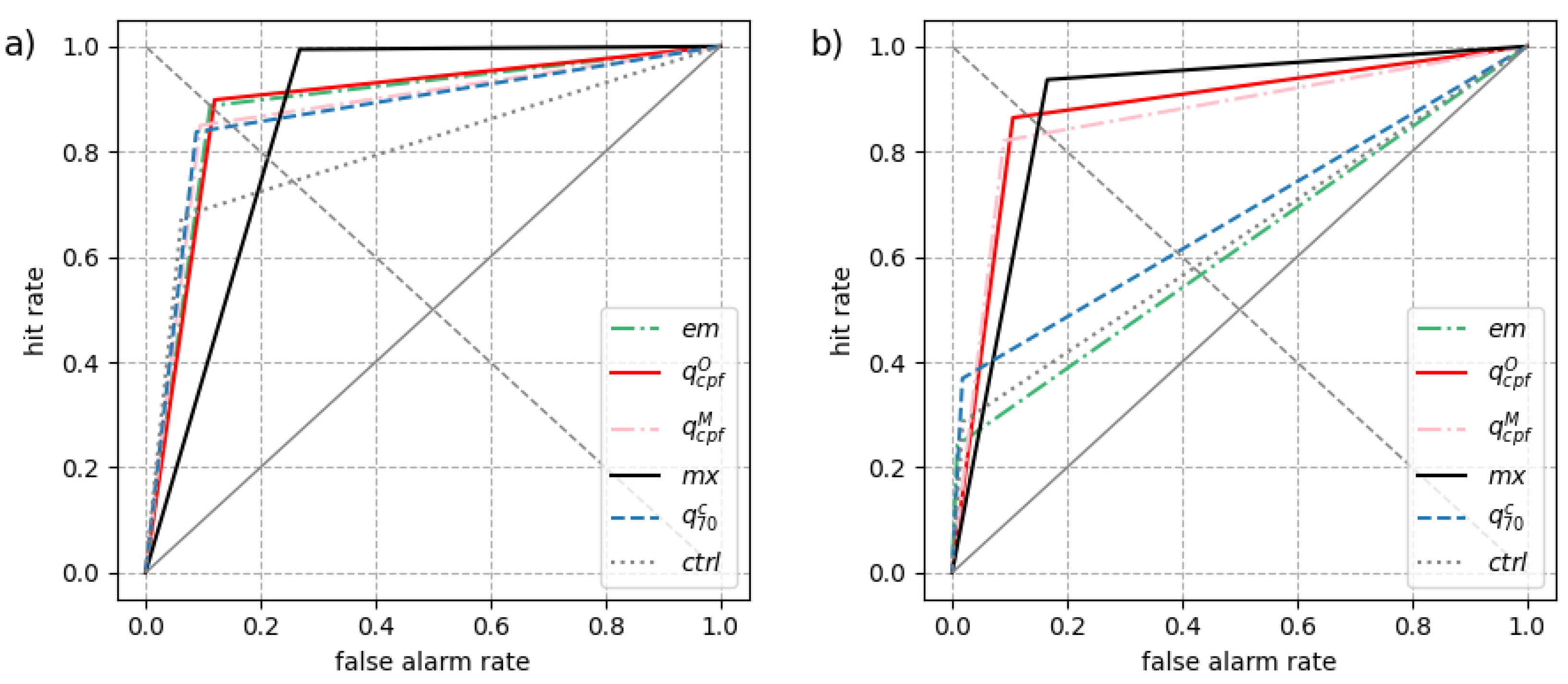

- a deterministic forecast, here the ensemble control member (ctrl),

- the ensemble mean (em), which is typically a smoothed field at longer time ranges as predictability decreases,

- the maximum of all ensemble members (mx), which can also be interpreted as a quantile forecast at probability level with M the ensemble size1,

- the quantile at a probability level of 70% conditioned on that at least half of the ensemble members indicates rain (). This latter is the consensus forecast used at Météo-France as a medium-range precipitation forecast.

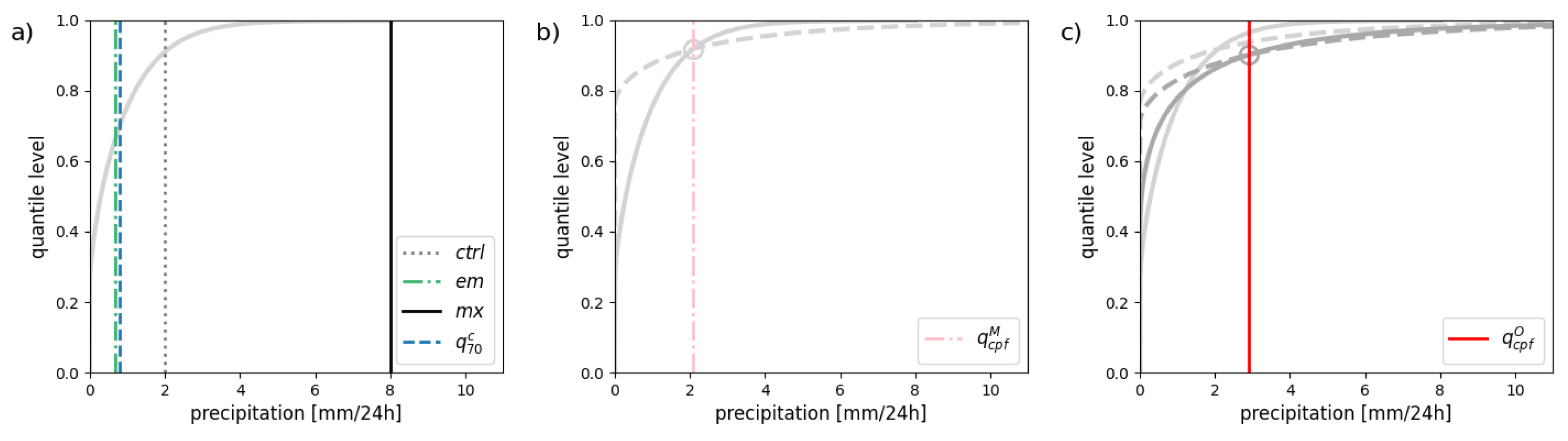

2.2. Self-Adaptive Quantiles

2.3. The Optimal Forecast in Terms of PSS

3. A Qualitative Assessment

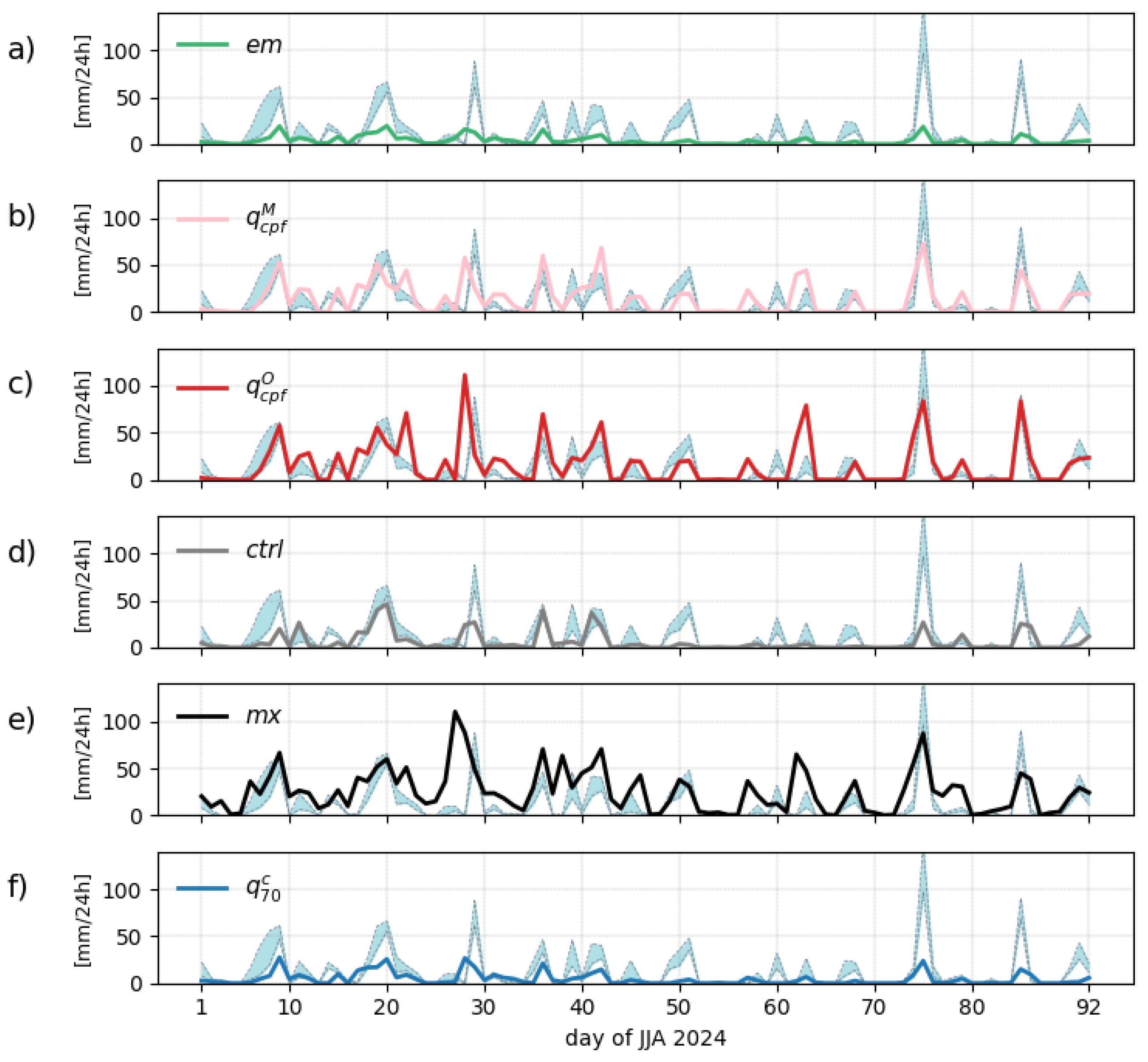

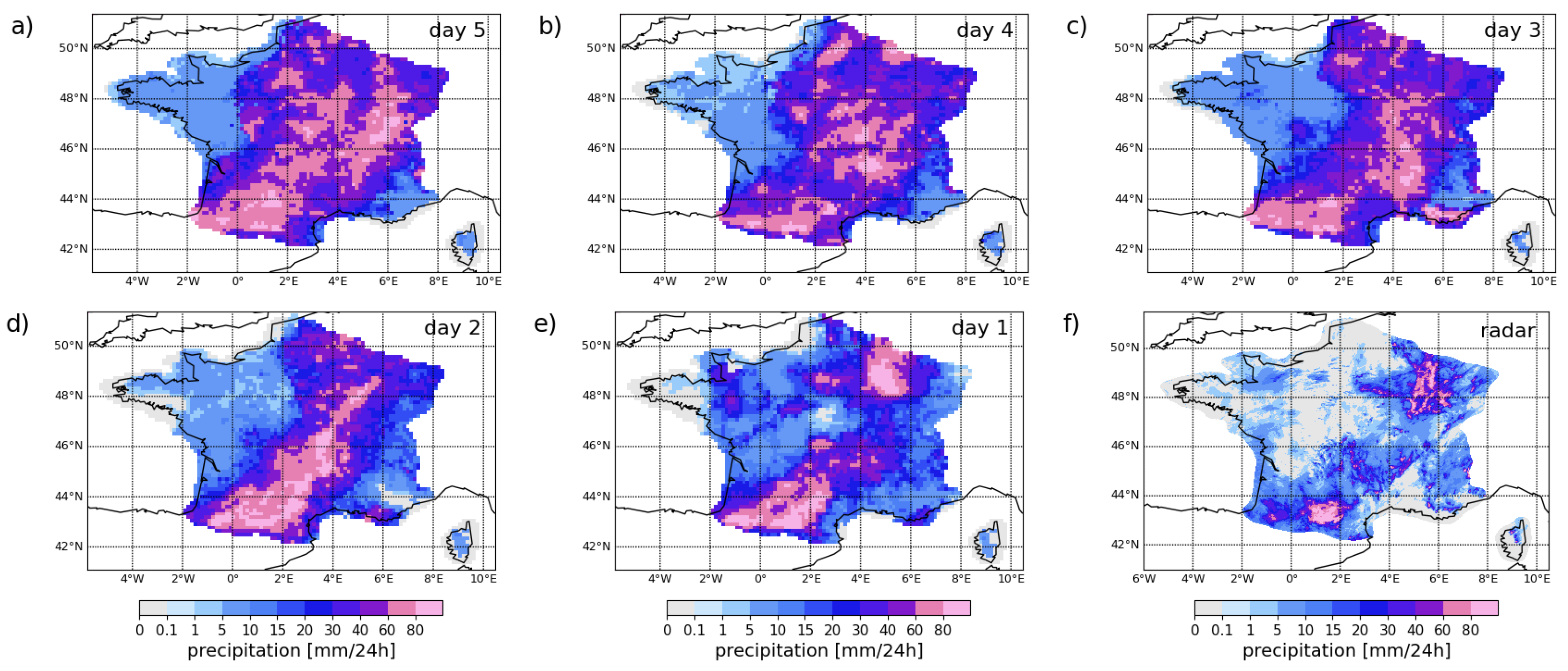

3.1. Time Series

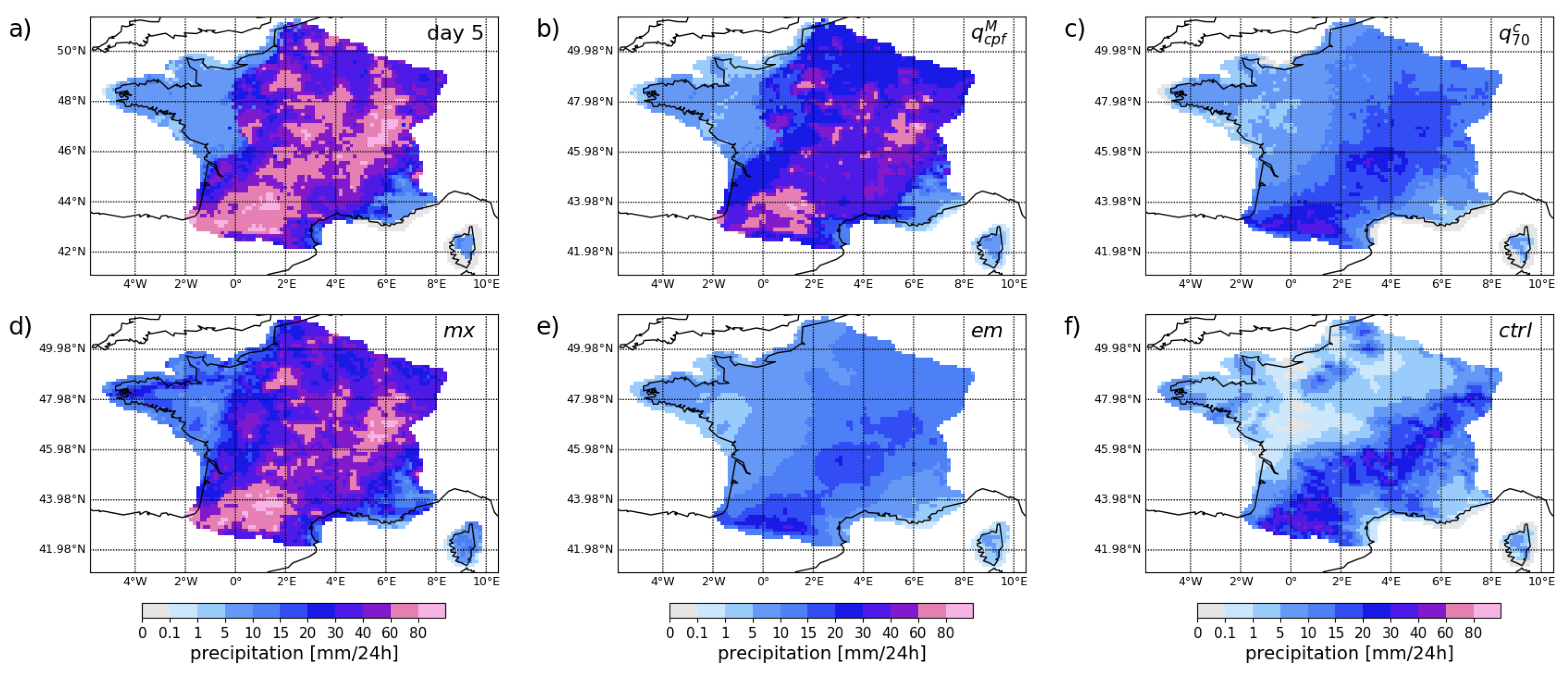

3.2. Maps

3.3. Forecast Consistency

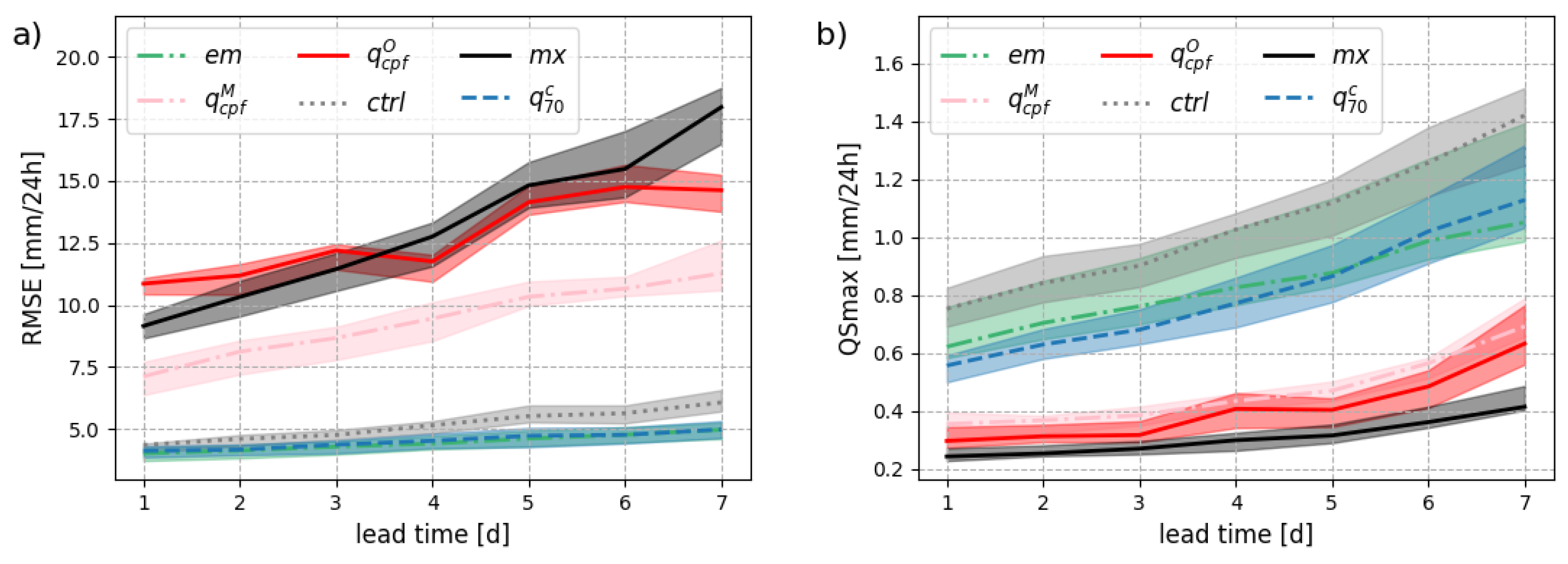

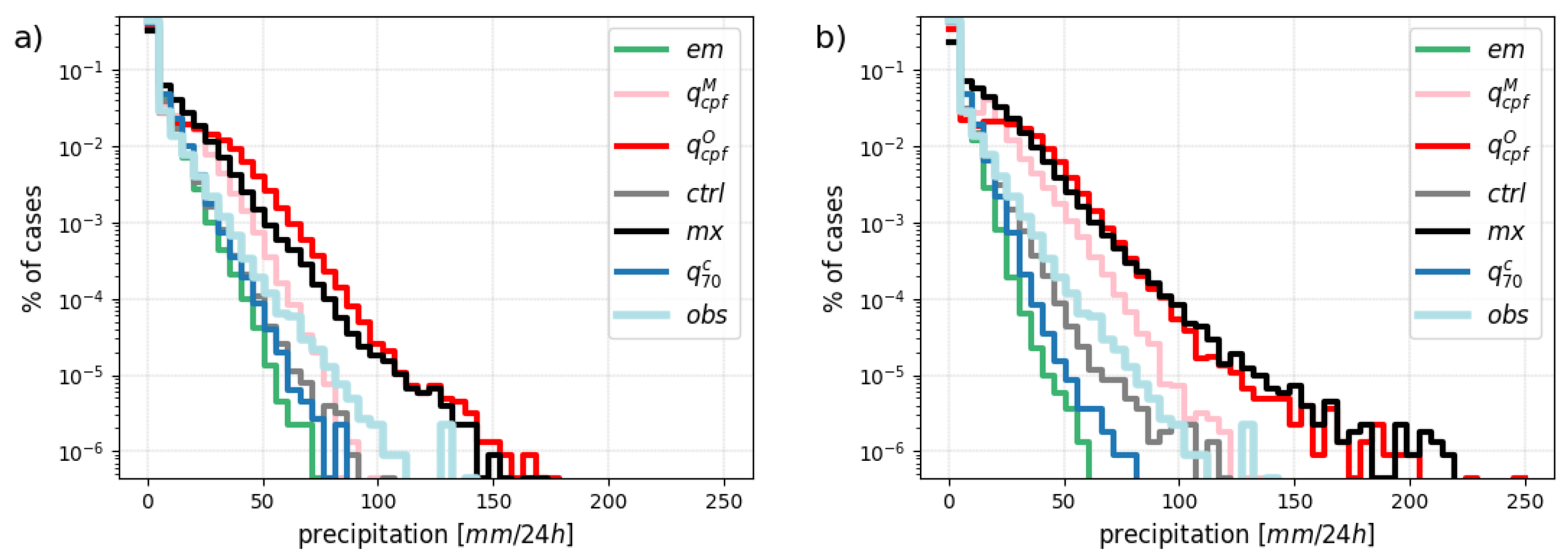

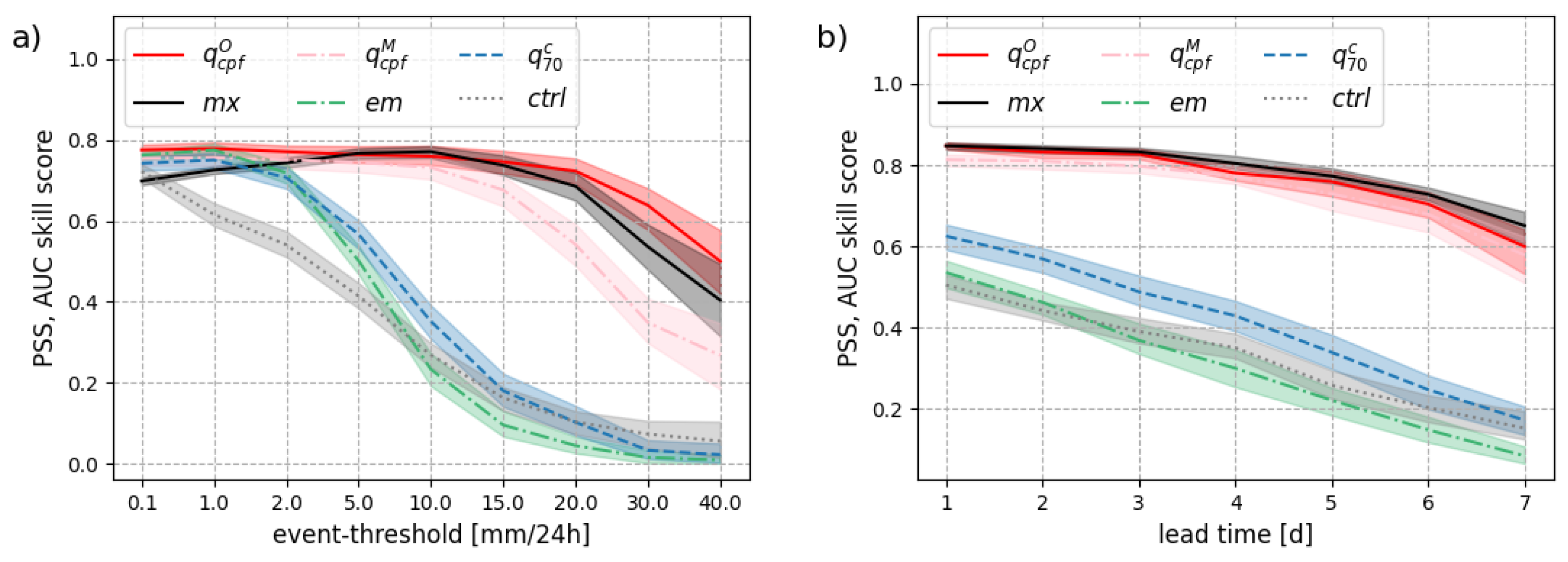

4. A Quantitative Assessment

4.1. Optimal Point-Forecasts

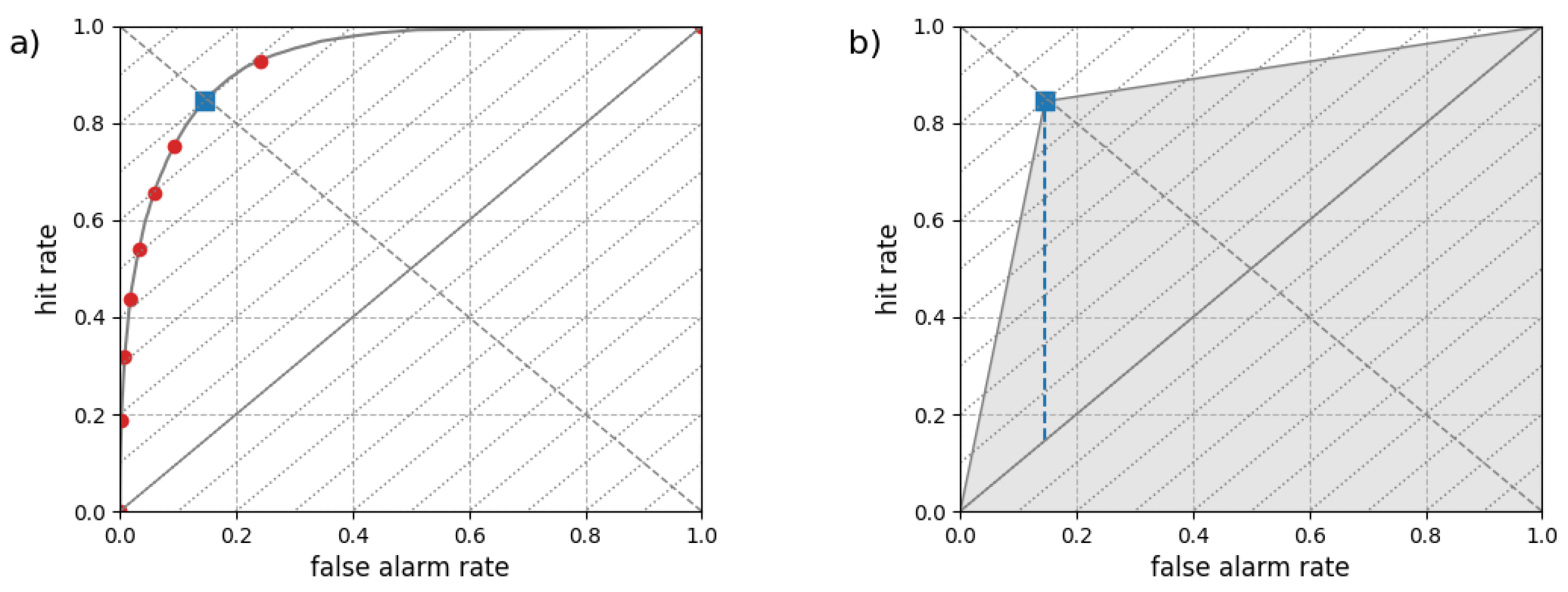

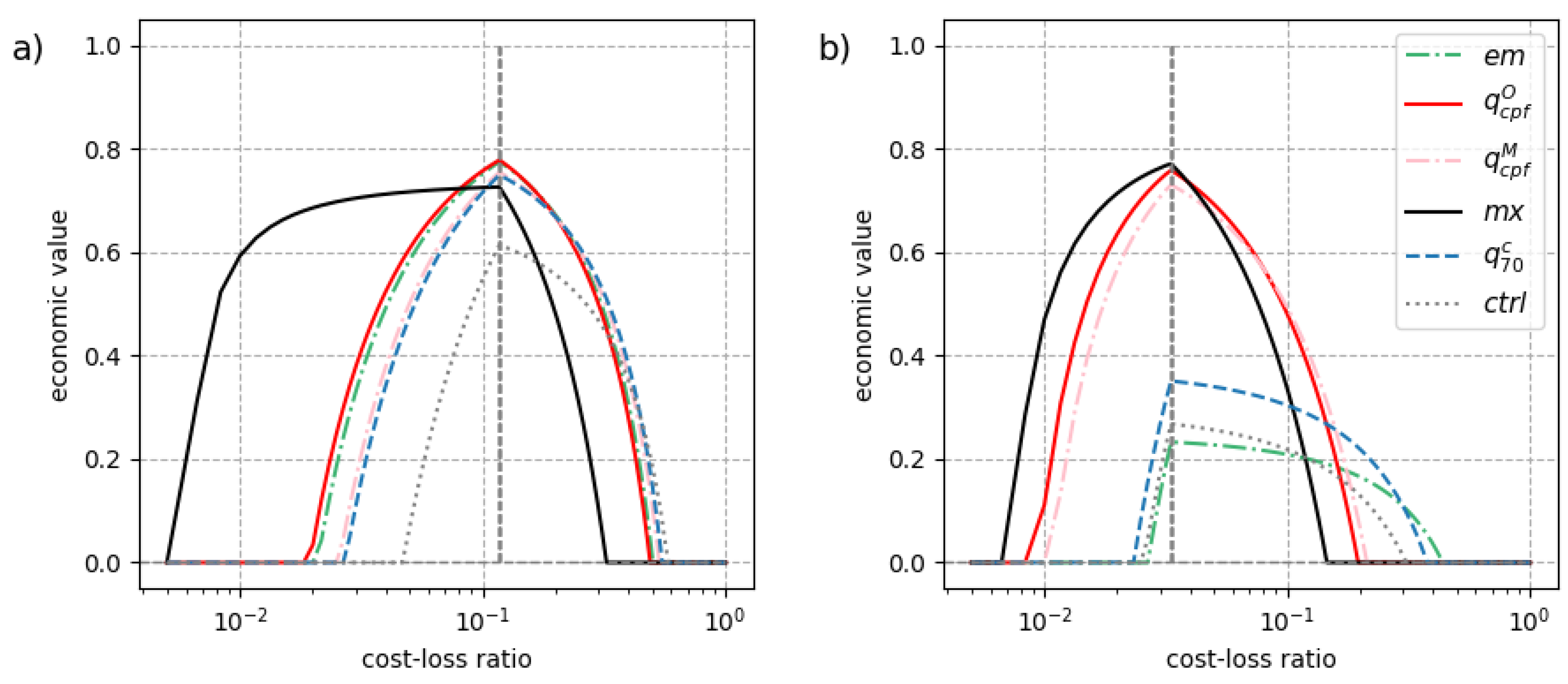

4.2. Economic Value

5. Summary and Outlook

- Elicitation. The link between crossing-point forecast and PSS is similar to the link between mean forecast and RMSE, or median forecast and MAE. Indeed, we demonstrate that the crossing-point quantile is the optimal forecast in terms of PSS (and equivalently in terms of ROC area) for any event. Further, the crossing-point quantile links the PSS with the Diagonal score, which can be interpreted as a weighted average of AUC, as shown in Appendix A.4.

- Extreme events. Optimality for any event includes optimality for rare and extreme events. We showcase the crossing-point performance with case studies and statistical analysis that support our theoretical findings. The predictive power of the crossing-point forecast for extreme events is also explored in [27].

- Condition of optimality. The necessary condition for optimality is calibration. The ensemble or probabilistic forecast needs to be well-calibrated to ensure a theoretical guarantee of optimality. When necessary, statistical post-processing can be applied to reach that goal [28].

- Model climate. When post-processing is used to calibrate the forecast, there is no need to build an M-climate based on reforecasts (which can be expensive). After calibration in the observation space, the climate distribution used to build the CPF would be directly estimated from observations for consistency. In the case of a well-calibrated system, model and observation have the same climatology.

- Observation climatology. The estimation of climate percentiles can be a moving target due to natural variability and anthropogenic climate change. When one build a climatology with limited observation records, one could consider using extreme value theory to better capture the tail of the distribution. For example, non-negative precipitation amounts can be fitted with an Extended Pareto Distribution as in Naveau et al. [29].

- Interpretation. Like any other quantile forecast, a self-adaptive quantile forecast based on the CPF is not a physically consistent spatial or temporal scenario. A crossing-point quantile forecast should be interpreted at each location (grid-point) as a local “probabilistic worst-case scenario”. In simple terms, the forecast indicates the most extreme event such that its likelihood is larger in the forecast than in the climatology [19].

- Usage. Self-adaptive quantile forecasts are particularly well-suited for users whose cost-loss ratio is unfocused, that is with a cost-loss ratio that decreases as the rarity of the event increases. As revealed by our economic value analysis, the crossing-point quantile forecast is not suitable for all users. In particular, users sensitive to false alarms might consider instead using the ensemble mean which displays large values only when the forecast uncertainty is small.

- Loss function. In principle, weighted proper scores could be used as loss functions to train weather forecasting models based on machine learning. For example, one could consider the Diagonal score which is consistent with the crossing-point forecast as a performance metric. The link between Diagonal score, PSS, and the coefficient of predictive ability [CPA, 30] is developed in Appendix A.4.

- Outlook. The quality of the CPF predominantly depends on the quality of the underlying ensemble prediction system. So, improvement for this new type of prediction would lie in 1) better raw (or post-processed) ensemble forecasts, and 2) more ensemble members for a finer estimation of the intersection point between distributions. Machine learning could help achieve these objectives in a near future.

Acknowledgments

Appendix A.

Appendix A.1. Model and Radar Climatology

Appendix A.2. Ensemble Calibration

Appendix A.3. Optimal forecast and frequency bias

Appendix A.4. Diagonal score, Peirce skill score, and universal ROC

References

- Bjerknes, V. Das Problem der Wettervorhersage, betrachtet vom Standpunkte der Mechanik und der Physik. Meteor. Z. 1904, 21, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L. A review of the applications of ensemble forecasting in fields other than meteorology. Weather 2024, 79, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leith, C.E. Theoretical skill of Monte Carlo forecasts. Monthly weather review 1974, 102, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, E. Forecasts and verifications in Western Australia. Monthly Weather Review 1906, 34, 23–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roulston, M.S.; Smith, L.A. The boy who cried wolf revisited: The impact of false alarm intolerance on cost–loss scenarios. Weather and Forecasting 2004, 19, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morss, R.E.; Lazo, J.K.; Brown, B.G.; Brooks, H.E.; Ganderton, P.T.; Mills, B.N. Societal and economic research and applications for weather forecasts: Priorities for the North American THORPEX program. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 2008, 89, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joslyn, S.; Savelli, S. Communicating forecast uncertainty: Public perception of weather forecast uncertainty. Meteorological Applications 2010, 17, 180–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fundel, V.J.; Fleischhut, N.; Herzog, S.M.; Göber, M.; Hagedorn, R. Promoting the use of probabilistic weather forecasts through a dialogue between scientists, developers and end-users. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society 2019, 145, 210–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagano, T.C.; Pappenberger, F.; Wood, A.W.; Ramos, M.H.; Persson, A.; Anderson, B. Automation and human expertise in operational river forecasting. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Water 2016, 3, 692–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, K. Clustering Technique Suitable for Eulerian Framework to Generate Multiple Scenarios from Ensemble Forecasts. Weather and Forecasting 2023, 38, 833–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roulston, M.S.; Smith, L.A. Combining dynamical and statistical ensembles. Tellus A: Dynamic Meteorology and Oceanography 2003, 55, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bright, D.R.; Nutter, P.A. Identifying the “best” ensemble member. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 2004, 85, 13–13. [Google Scholar]

- Roebber, P.J. Seeking consensus: A new approach. Monthly weather review 2010, 138, 4402–4415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhshaii, A.; Stull, R. Deterministic ensemble forecasts using gene-expression programming. Weather and Forecasting 2009, 24, 1431–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, C.S.; Romine, G.S.; Smith, K.R.; Weisman, M.L. Characterizing and optimizing precipitation forecasts from a convection-permitting ensemble initialized by a mesoscale ensemble Kalman filter. Weather and Forecasting 2014, 29, 1295–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouttier, F.; Marchal, H. Probabilistic short-range forecasts of high precipitation events: optimal decision thresholds and predictability limits. EGUsphere 2024, 2024, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegel, J.F. Coherence and elicitability. Mathematical Finance 2016, 26, 901–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peirce, C. The numerical measure of the success of predictions. Science 1884, 4, 453–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Bouallègue, Z. On the verification of the crossing-point forecast. Tellus A: Dynamic Meteorology and Oceanography 2021, 73, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Bouallègue, Z.; Haiden, T.; Richardson, D.S. The diagonal score: Definition, properties, and interpretations. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society 2018, 144, 1463–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bröcker, J. Evaluating raw ensembles with the continuous ranked probability score. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society 2012, 138, 1611–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzato, A. A Note On the Maximum Peirce Skill Score. Wea. Forecasting 2006, 22, 1148–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, D.S. Economic value and skill. In Forecast Verification: A Practitioner’s Guide in Atmospheric Science; Jolliffe, I.T.; Stephenson, D.B., Eds.; John Wiley and Sons, 2011; pp. 167–184.

- Ben Bouallègue, Z.; Pinson, P.; Friederichs, P. Quantile forecast discrimination ability and value. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc. 2015, 141, 3415–3424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabary, P.; Dupuy, P.; L’Henaff, G.; Gueguen, C.; Moulin, L.; Laurantin, O. A 10-year (1997―2006) reanalysis of Quantitative Precipitation Estimation over France: methodology and first results. IAHS-AISH publication 2012, 1, 255–260. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, D.S. Skill and relative economic value of the ECMWF ensemble prediction system. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2000, 126, 649–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Bouallègue, Z. Seamless prediction of high-impact weather events: a comparison of actionable forecasts. Tellus A: Dynamic Meteorology and Oceanography 2024, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vannitsem, S.; Bremnes, J.B.; Demaeyer, J.; Evans, G.R.; Flowerdew, J.; Hemri, S.; Lerch, S.; Roberts, N.; Theis, S.; Atencia, A.; et al. Statistical postprocessing for weather forecasts: Review, challenges, and avenues in a big data world. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 2021, 102, E681–E699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveau, P.; Huser, R.; Ribereau, P.; Hannart, A. Modeling jointly low, moderate, and heavy rainfall intensities without a threshold selection. Water Resources Research 2016, 52, 2753–2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gneiting, T.; Walz, E.M. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) movies, universal ROC (UROC) curves, and coefficient of predictive ability (CPA). Machine Learning 2022, 111, 2769–2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | If one would like to optimise the continuous ranked probability score, the ensemble members must be interpreted as quantile forecasts at probability levels with according to [21]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).