Submitted:

15 April 2025

Posted:

15 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

- Why does gender-based violence persist in Timor-Leste?

- How do various factors contribute to women’s vulnerability to gender-based violence in Timor-Leste?

2. Methods

2.1. Literature Selection

2.2. Data Extraction and Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Feminist Theory in Post-Conflict Contexts

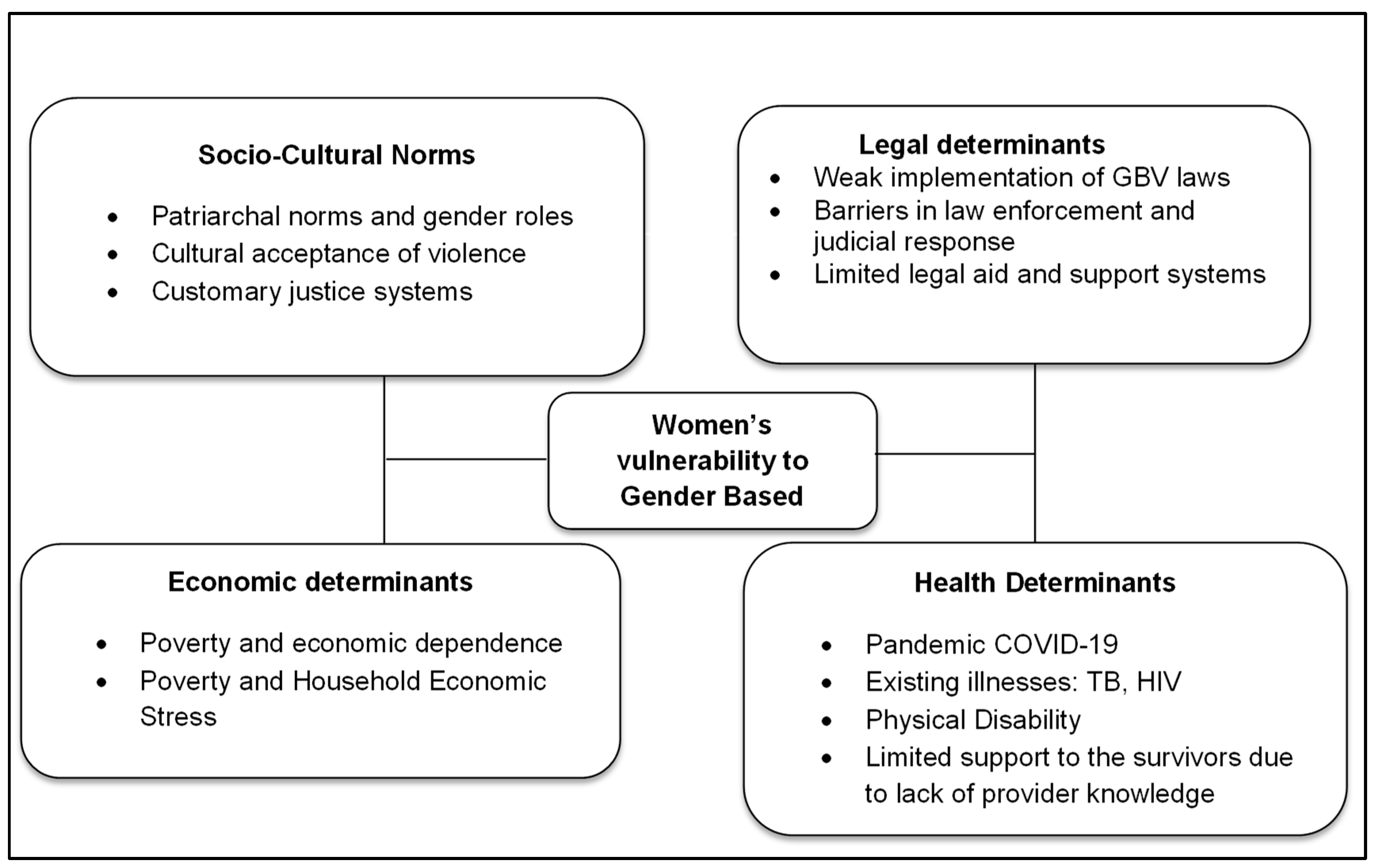

3.2. Intersectional Factors Contributing to Women’s Vulnerability to GBV in Timor-Leste

Socioeconomic Determinants of Gender-Based Violence (GBV)

Law and Culture

Limitations

Conclusions

Autor contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UN WOMEN. Facts and figures: Ending violence against women | UN Women – Headquarters [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Apr 1]. Available from: https://www.unwomen.org/en/articles/facts-and-figures/facts-and-figures-ending-violence-against-women.

- Global database on Violence against Women | UN Women Data Hub [Internet]. [cited 2025 Apr 2]. Available from: https://data.unwomen.org/global-database-on-violence-against-women.

- Administrative Data Mapping on Violence Against Women and Girls in Timor-Leste. 2022 [cited 2025 Apr 9]; Available from: https://timor-leste.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/administrative_data_portrait_on_vawg_in_tl_2_feb_2022_0.pdf.

- Violence against women and girls – what the data tell us | World Bank Gender Data Portal [Internet]. [cited 2025 Apr 2]. Available from: https://genderdata.worldbank.org/en/data-stories/overview-of-gender-based-violence.

- UN. Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action Beijing + 5 Political Declaration and [Internet]. 1995. 277 p. Available from: https://www.icsspe.org/system/files/Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action.pdf.

- UN WOMEN. Beijing Women ’ S Rights in Review 25 Years After Beijing. 2025;3(6):33. Available from: https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/ publications/2025/03/womens-rights-in-review-30-years-after-beijing. ISBN:.

- Country Fact Sheet | UN Women Data Hub [Internet]. [cited 2025 Apr 1]. Available from: https://data.unwomen.org/country/timor-leste.

- Greenhalgh T, Thorne S, Malterud K. Time to challenge the spurious hierarchy of systematic over narrative reviews? Eur J Clin Invest [Internet]. 2018;48(6):418–9. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29578574/.

- Ferrari R. Writing narrative style literature reviews. Med Writ [Internet]. 2015;24(4):230–5. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1179/2047480615Z.000000000329.

- Sukhera, J. Narrative Reviews: Flexible, Rigorous, and Practical. J Grad Med Educ [Internet]. 2022 Aug 1 [cited 2025 Apr 1];14(4):414. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9380636/.

- Crenshaw, KW. Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Public Nat Priv Violence Women Discov Abus. 2013;43(6):93–118.

- Hankivsky, O. Women’s health, men’s health, and gender and health: implications of intersectionality. Soc Sci Med [Internet]. 2012 Jun [cited 2025 Apr 14];74(11):1712–20. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22361090/.

- True, J. The Political Economy of Violence against Women [Internet]. The Political Economy of Violence against Women. Oxford University Press; 2012 [cited 2025 Apr 14]. 1–256 p. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/275311359_The_Political_Economy_of_Violence_Against_Women_A_Feminist_International_Relations_Perspective.

- Myrttinen, H. Violence and hegemonic masculinities in Timor-Leste – on the challenges of using theoretical frameworks in conflict-affected societies. Peacebuilding [Internet]. 2024 Oct 1 [cited 2025 Apr 1]; Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/21647259.2024.2384202.

- Mcphail BA, Busch NB, Kulkarni S, Rice G. An Integrative Feminist Model The Evolving Feminist Perspective on Intimate Partner Violence. Violence Against Women [Internet]. 2007 [cited 2025 Apr 1];13:817–41. Available from: http://vaw.sagepub.comhttp//online.sagepub.com.

- Niner, S. Hakat klot, narrow steps: Negotiating gender in post-conflict timor-leste. Int Fem J Polit [Internet]. 2011 Sep [cited 2025 Apr 14];13(3):413–35. Available from: https://scholar.google.com.au/citations?view_op=view_citation&hl=en&user=AGNTYTkAAAAJ&citation_for_view=AGNTYTkAAAAJ:d1gkVwhDpl0C.

- Niner, S. Veterans and Heroes: The Militarised Male Elite in Timor-Leste. Asia Pacific J Anthropol [Internet]. 2020 Mar 14 [cited 2025 Apr 14];21(2):117–39. Available from: https://www.fundasaunmahein.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/Veterans-and-Heroes-The-Militarised-Male-Elite-in-Timor-Leste.pdf.

- Renzetti, CM. Criminal Behavior, Theories of. Encycl Violence, Peace, Confl Vol 1-4, Third Ed [Internet]. 2022 Jan 1 [cited 2025 Apr 6];1:12–21. Available from: https://scholars.uky.edu/en/publications/criminal-behavior-theories-of-2.

- Timor-Leste: Politics, the patriarchy, and the paedophile priest – Monash Lens [Internet]. [cited 2025 Apr 14]. Available from: https://lens.monash.edu/@politics-society/2021/02/26/1382892/timor-leste-political-leadership-patriarchal-relationships-and-the-paedophile-priest.

- Parenting education brings fathers to the front in Timor-Leste | UNICEF Timor-Leste [Internet]. [cited 2025 Apr 14]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/timorleste/stories/parenting-education-brings-fathers-front-timor-leste.

- Martins N, Soares D, Gusmao C, Nunes M, Abrantes L, Valadares D, et al. A qualitative exploration of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on gender-based violence against women living with HIV or tuberculosis in Timor Leste. 2024;1–20. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0306106.

- (ed.) SN. Women and the politics of gender in post-conflict Timor-Leste. Women in Asia Series. 2016.

- Pereira BAT. Women of Timor-Leste: Unyielding in the fight against wechsel oppression and violence. Stift Asienhaus Stift [Internet]. 2020;6. Available from: https://www.asienhaus.de/aktuelles/blickwechsel-women-of-timor-leste-unyielding-in-the-fight-against-oppression-and-violence.

- Mulder, S. Timor&Women_IWDA_Wave: Women and Political Leadership in Timor Leste- Literature Review. 2019;(October). Available from: https://iwda.org.au/assets/files/Women-and-Political-Leadership-Literature-Review-Timor-Leste_publicPDF3_3_2020.pdf.

- Niner SL, Loney H. The Women’s Movement in Timor-Leste and Potential for Social Change. Polit Gend [Internet]. 2020;16(3):874–902. Available from: https://research.ceu.edu/en/publications/the-womens-movement-in-timor-leste-and-potential-for-social-changes.

- From Resistence to Neoliberal Capture: NGOisation of Feminism in Timor-Leste | by Berta Antonieta | Mar, 2025 | Medium [Internet]. [cited 2025 Apr 4]. Available from: https://medium.com/@BertaAntonieta/from-resistence-to-neoliberal-capture-ngoisation-of-feminism-in-timor-leste-b12118b6e553.

- Charlesworth H, Wood M. Women and human rights in the rebuilding of East Timor. Nord J Int Law [Internet]. 2002 [cited 2025 Apr 4];71(2):325–48. Available from: http://journals.kluweronline.com/article.asp?PIPS=5109205.

- Durevall D, Lindskog A, Da Dalt AT, Wild K, Young F, Araujo G De, et al. Women’s Perceptions of Their Agency and Power in Post-Conflict Timor-Leste. J Int Womens Stud [Internet]. 2015;3(1):299–317. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70343-2.

- In Women’s Words | Default Book Series [Internet]. [cited 2025 Apr 4]. Available from: https://www.liverpooluniversitypress.co.uk/doi/abs/10.3828/9781845198916.

- Niner SL, Loney H. The Women’s Movement in Timor-Leste and Potential for Social Change. Polit Gend [Internet]. 2020 Sep 1 [cited 2025 Apr 4];16(3):874–902. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/politics-and-gender/article/abs/womens-movement-in-timorleste-and-potential-for-social-change/32F60D519A349FFEA0B97CEE7F90312F.

- The World Bank. The Timor-Leste Country Gender Action Plan (CGAP) 2021 [Internet]. The Timor-Leste Country Gender Action Plan (CGAP) 2021. 2021. Available from: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099905008122242158/pdf/P172182039349a03b0bd580523c9d4dd50c.pdf.

- World Bank Group. Timor-Leste Economic Report: Moving Beyond Uncertainty [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2020 Jun 9]. Available from:http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/207941557509771185/pdf/Timor-Leste-Economic-Report-Moving-Beyond-Uncertainty.pdf.

- Timor-Leste | World Bank Gender Data Portal [Internet]. [cited 2025 Apr 9]. Available from: https://genderdata.worldbank.org/en/economies/timor-leste.

- The World Bank. The World Bank Research Observer. 2021 [cited 2021 Sep 28]. Timor leste Overview. Available from: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/timor-leste/overview.

- The Asia Foundation. Ending Violence against Women and Children in the Philippines. 2020; Available from:https://asiapacific.unfpa.org/en/publications/ending-violence-against-women-and-children-philippines.

- Madden, J. Engaging with Customary Law in Timor-Leste: Approaches to Increasing Women’s Access to Justice. 2013;1(2). Available from: https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/2024-12/justicereform_report_en_digital_0.pdf.

- Martins N, Soares D, Gusmao C, Nunes M, Abrantes L, Valadares D, et al. A qualitative exploration of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on gender-based violence against women living with HIV or tuberculosis in Timor Leste. PLoS One [Internet]. 2024 Aug 1 [cited 2025 Apr 1];19(8). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39133682/.

- Nazareth De Oliveira B, Bere MA, Wondeng H, Barros O, Gonçalves EC, Xavier J, et al. LEI E PRÁTICA DO PROCESSO PENAL NOS CASOS DE VIOLÊNCIA BASEADA NO GÉNERO EM TIMOR-LESTE Este relatório foi desenvolvido sob o patrocínio da Iniciativa Spotlight Timor-Leste RESPONSÁVEL TÉCNICA E AUTORA PRINCIPAL. [cited 2025 Apr 1]; Available from: www.jus.

- UNDP. Towards better justice Towards better justice. 2024;(May). Available from: https://www.undp.org/timor-leste/publications/towards-better-justice-analysis-and-recommendations-improving-justice-sector-timor-leste-main-report.

- The Asia Foundation. Understanding Violence against Women and Children in Timor-Leste: Findings from the Nabilan Baseline Study. 2016;1–204. Available from: www.asiafoundation.

- Casebolt T, Hardiman M. Experiences of gender based violence and help seeking trends among women with disabilities: an analysis of the demographic and health surveys. Health Sociol Rev [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Apr 8];33(2):125–43. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38832495/.

- Wild KJ, Gomes L, Fernandes A, de Araujo G, Madeira I, da Conceicao Matos L, et al. Responding to violence against women: A qualitative study with midwives in Timor-Leste. Women and Birth [Internet]. 2019 Aug 1 [cited 2025 Apr 1];32(4):e459–66. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30448244/.

- Tackling Gender-Based Violence (GBV) in Timor-Leste - Timor-Leste | ReliefWeb [Internet]. [cited 2025 Apr 9]. Available from: https://reliefweb.int/report/timor-leste/tackling-gender-based-violence-gbv-timor-leste.

- Timor-leste UNIN, On RG, Violence TOG based, Misconduct S. UNITED NATIONS IN TIMOR-LESTE PREVENTION AND RESPONSE TO GENDER-BASED VIOLENCE ( INCLUDING HARASSMENT,. :1–64.

- Sustainable development High-level political forum on sustainable development, convened under the auspices of the Economic and Social Council Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals. 2023 [cited 2025 Apr 14]; Available from: https://sdgs.un.org/goals.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).