1. Introduction

The Australian Transition Care Program (TCP) is a national service that provides short-term care and support to older adults who immediately post-discharge from hospital require additional assistance to regain their independence and improve their quality of life after a hospital stay [

1]. The program is available to people aged 65 and over, or those aged 50 years and over who are of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander descent. TCP is delivered in a community-based or residential aged care facility-based setting, or a combination of both [

2]. It is a goal-oriented, slow-stream, and time-limited rehabilitation program lasting up to 12 weeks with a possible extension for a further 6 weeks [

1]. TCP provides a range of services, including allied health services, nursing care, personal care, and domestic assistance. During TCP, a care plan is developed to meet the individual's specific needs and goals. The number of people in TCP has seen a yearly increase since its inception, from approximately 7,000 to more than 25,000 people nationally at its peak. In 2017/18, there were 25,113 care recipients enrolled in the TCP, and the average age of these was 81 years, and 60 per cent were female [

3]. Recipients received care for an average of 60 days [

3].

A key objective of the TCP is to reduce hospital readmissions of older adults [

4]. An initial evaluation of the program in 2008, shortly after its inception [

5], found that, compared to a comparable group of older adults discharged from hospital without receiving TCP (n=2,188), those in TCP (n=2,443) exhibited superior physical function, a reduced risk of hospital readmission, an extended time to readmission, and a diminished risk of entry to residential aged care within 6 months [

6]. Despite significant investment in this program from government health departments, very few evaluations have occurred in the last 15 years, and it remains under-researched. Systematic reviews of similar transition care programs globally indicate their effectiveness in reducing the risk of unplanned hospital readmissions [

4]. Given the costs and resources utilised in TCP, understanding the role of Australian TCP in the reduction of hospital readmissions across different client categories is imperative. The type of goals that clients set may be one such category to examine.

Goal setting is an important component of rehabilitation. It acts as a mechanism to align the objectives of clients with those of their rehabilitation team, ensuring that goals are personally meaningful to clients. By connecting care plans directly to the client’s goals [

1], motivation is enhanced and the likelihood of behaviour change is increased [

7]. Previous work by the research team has demonstrated that goals established by TCP clients align to the World Health Organization International Classification of Functioning Categories. Specifically, 74% of these goals can be categorised as home-based goals (activities within clients’ premises such as cooking and showering) and 26% as community-based goals (activities outside clients’ premises such as attending church, or visiting a friend) [

8,

9]. Additionally, this study also found that approximately 30% of clients set only home-based goals.

This study aimed to investigate whether the type of goals set by older adults, be they home-based or community-based, influences their likelihood of unplanned hospital readmission within 6 months. It is hypothesised that TCP clients who establish community-based goals will exhibit a reduced risk of hospital readmissions compared to those who set home-based goals only. The attainment of community-based goals might be indicative of confidence in setting more diverse domestic and recreational goals coupled with the functional capacity to navigate the community [

9]. This could contribute to enhanced levels of physical activity and increased social engagement, thereby potentially reducing the risk of hospital readmissions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This was a single-site retrospective cohort study in a metropolitan health service that utilised data collected from a local database of the Transitional Care Program at Bayside Health (‘Transdata’) and the health service integrated electronic Medical Record (ieMR).

2.2. Setting

This project was conducted in one of three TCP programs serving residents within the Metro South Health catchment area, Queensland, Australia. Clients discharged from hospital with a stable medical condition were admitted to the Bayside TCP from 1st July 2014 to 31st December 2019 were included in this study. The population in the Redland Health catchment area in 2020 was approximately 160,331, with approximately 19% aged 65 years or older.

The program employed allied health professionals (occupational therapists, physiotherapists, speech pathologists, dietitians), allied health assistants, nurses, and personal care workers. Clinical staff members provided both discipline-specific care and case management services based on client needs., A supplementary brokerage model was utilised to ensure that TCP clients received the required service provided by allied health, nursing, and personal care as agreed in the individual care plan based on the clients’ needs [

2]. The Bayside TCP site had a total of 50 TCP packages, 35 packages in the community and 15 packages in residential aged care facilities (RACF). The average number of clients admitted to the program during the study period was 325 annually.

2.3. Participants

Clients were admitted to Bayside TCP community or residential packages were included in the study. Clients must have been discharged from Bayside TCP to be included in the study. That is, not transferred to another TCP, re-admitted for a planned hospital admission, and subsequently discharged without TCP, or died during TCP admission.

Goals

At entry to TCP, a collaborative discussion between the client, case manager and allied health staff to establish goals during the clients’ admission to the program was conducted. There was no standardised goal-setting instrument used but rather SMART (Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Realistic, Timely) goals were applied and recorded in Transdata [

10].

Goals were categorised according to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and health Framework (ICF) [

8]. Community goals were defined as any intended action by the client outside their home boundary, whereas home goals were defined as any intended action by the client inside home boundaries. Based on this definition, ICF categorised goals can be classified as home or community goals. For example, a mobility goal of ‘to walk independently from the bedroom to the bathroom in two weeks’ is a home goal, while ‘to walk independently to the end of the road in four weeks’ is a community goal. Multidisciplinary team case conferences were held once weekly, led by a geriatrician, to discuss client progress and goal attainment. On discharge, goals were classified as ‘did not attain’, ‘partially attained’, or ‘fully attained’ [

8].

2.4. Dataset

Bayside TCP use a local database, developed in 2010, called ‘Transdata’ that includes demographic and clinical variables. Goals statements, category, attainment and likelihood of attainment recorded for each client at entry and program exit. Two researchers (NB and EM) completed data management together and reclassified goals as home-based or community-based goals. A third researcher (SS) was involved in the event of disagreement with goals classification to review and assist with decision-making.

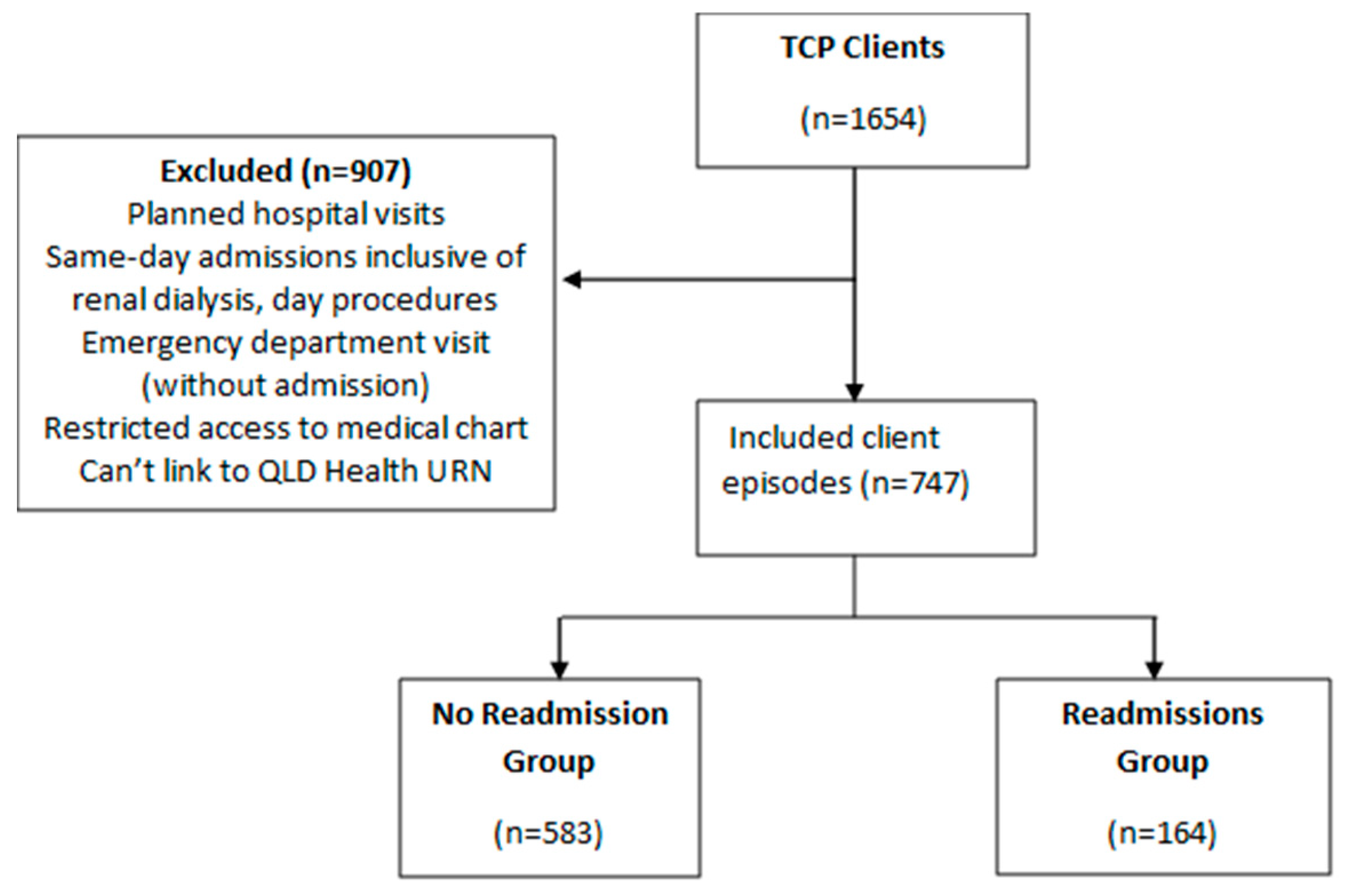

Dataset Linking

Two researchers (NB and AK) used demographic data to link Transdata with ieMR using Unique Record Numbers (URNs). Unplanned hospital admission via a public hospital emergency department within six months of TCP discharge was obtained from ieMR. Planned hospital admissions, admissions for renal dialysis, admissions for elective surgery or day therapy e.g. infusion, and emergency department presentations not requiring hospital admission were excluded. Clients with restricted access to their medical chart or monitored chart in ieMR were also excluded.

2.5. Measures

At TCP admission, demographic and clinical characteristics information were obtained including age, gender, living arrangement, length of hospital stay, reason for TCP admission, number of comorbidities, carer availability, hospital readmission while receiving TCP, TCP discharge disposition and services. The length of TCP admission was also calculated. The Modified Barthel Index (MBI; a single measure of independence in activity of daily living (scale, 0 [severe functional dependence] to 100 [functional independence]) [

11] was completed at entry and exit of the program by the case manager. The goals’ ICF category, type of goal (home vs community), number of goals, and number of goals attained were also recorded.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Goal attainment was categorised as attained and not attained, collapsing partially attained to attained. Continuous variable means were compared using t-tests and categorical variables were compared using chi-square tests; non-parametric tests were used for non-normally distributed data. Logistic regression was utilised to examine predictors of 6 months hospital readmissions (dependent variable). The independent variables included in the analysis were age, gender, entry MBI, MBI change, number of community goals achieved, number of home goals achieved, TCP length of stay, inpatient length of stay, client carer, and number of comorbidities. The variables with significant (

p<0.05) relationship with the outcome were included in the final logistic regression model. The Area Under the Curve (AUC) was calculated for the final model to determine predictive ability [

12]. All statistical analyses were performed at SPSS version 27.

3. Results

3.1. Client Characteristics

Out of 1654 TCP episodes, 747 client episodes were linked to QLD health with Unique Record Numbers (URN). From these, 583 (78%) were not readmitted to hospital during the observation period, while 164 (22%) were readmitted to hospital (

Figure 1).

In total, patients had a mean age of 80.3 years (SD = 8.1 years), predominantly female (66.8%), and the majority did not have a carer (74.1%). Analyses indicated significant differences between clients readmitted to hospital and those that were not. Readmitted clients exhibited a lower exit MBI (74.2 vs 75.9;

P = 0.001), and a smaller change in MBI (11.5 vs 14.4;

P = 0.005) (

Table 1).

3.2. Client Goals

Table 2 shows the differences in the number and type of goals set by clients eventually readmitted to hospital versus those that remained at home. Those readmitted set a lower number of overall goals (3.64 vs 4.03;

P= 0.006), achieved a fewer number of goals by discharge from TCP (2.80 vs 3.40;

P < 0.001), including fewer community-based goals (0.60 vs 0.83;

P= 0.001).

3.3. Association Between Community-Goals and Readmission to Hospital

Table 3 shows the adjusted logistic regression analysis examining the association between the number of community goals achieved and hospital readmission. Adjusting for age, sex, change in MBI status, number of home goals achieved, carer status, and number of comorbidities, each additional community goals achieved was associated with a 30% reduction in risk of hospital readmission (OR=0.699; 95% CI:0.558, 0.875,

P=0.002). The ROC AUC for this model was 0.64; 95% CI 0.59 to 0.68,

P<0.001.

4. Discussion

This study observed that, after adjusting for demographic and clinical variables, each additional community-based goal achieved was associated with a 30% reduction in the risk of hospital readmission. Home-based goal attainment, change in function or clinical variables were not associated with hospital readmission in adjusted models.

One possible mechanism for how setting and attaining community-based goals is associated with a lower risk of hospital readmission is through increases in incidental and planned physical activity. Time spent in hospital can result in hospital-acquired muscle deconditioning, leading to lower levels of physical activity and poor outcomes [

13]. A previous study led by this study’s lead researcher utilised an accelerometer to objectively assess activity patterns in TCP clients and found that the clients, on average, spend only 35 minutes walking each day [

14]. This same study also found emerging evidence that a higher amount of walking time was associated with the achievement of more goals, although the association did not reach statistical significance.

Regular physical activity is strongly associated with better health outcomes for all ages [

15]. There is a strong association between regular physical activity and reduced all-cause mortality, even if the physical activity is at a moderate level [

16]. Moderate intensity exercise for 30 minutes (or approx. 3,000 additional steps [

17] on most days of the week lowers the risk of developing a range of chronic and life-threatening conditions, including dementia, obesity, cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, stroke, dementia, osteoporosis, as well as some cancers [

18]. In addition, regular physical activity has been shown to improve both mood and cognitive function in older adults, and as such physical exercise is utilised in the management of chronic conditions such as depression, anxiety, chronic obstructive airway disease, arthritis, and chronic pain [

19]. An increase of 30 minutes of physical activity on most days of the week also aligns with the Australian Physical Activity Guidelines for older adults [

20].

Increasing physical activity, both incidental and planned, is crucial for older Australians participating in a TCP to reduce hospital readmissions. However, strategies to encourage older adults to increase their physical activity often prove to be ineffective. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of physical activity programs for older people in the community receiving home care services found that adherence rates to the examined programs were low, mostly at 50% or less [

21]. Identifying and setting personal goals for their rehabilitation journey may help older adults increase their incidental physical activity [

22].

A second potential mechanism as to how attainment of community-based goals is associated with a lower risk of hospital readmission is through increases in the depth and frequency of social interactions. Social support, reduced loneliness or social isolation, and a sense of belonging are strong predictors of health and quality of life [

23]. The risk of loneliness on mortality has been compared to that of obesity or smoking [

24]. Furthermore, studies suggest a potential bi-directional relationship between social isolation and physical impairments, such as low physical function can lead to social isolation, and social isolation or loneliness can also result in poorer functional status [

25]. Community-based goals, such as visiting friends, attending church, and generally participating in the community, may alleviate some of the negative consequences [

26].

Strength and Limitations

Strengths of this study include a relatively large dataset and the use of a robust method via ICF classification for TCP goals to classify home versus community goals via two research team members and a third member in case of disagreement. However, the study was based on a single site in a metropolitan area of Brisbane, Australia, and findings may not be generalisable to other areas. The data was collected retrospectively, and the visibility of readmissions for clients outside of Queensland Health was limited, potentially missing clients who were readmitted to private or interstate hospitals. Another limitation of this study is its cross-sectional nature, meaning conclusions cannot be drawn about the causality of the identified relationships. While the analyses adjusted for baseline participant characteristics related to function and comorbidities, it remains plausible that more robust participants were the ones able to set and achieve community goals, rather than the community goals directly influencing outcomes. The data for the nutrition and cognitive assessment was not uniformly collected throughout the period. The subsequent step would involve empirically testing the causality of this relationship through a randomised controlled trial.

5. Conclusions

The study’s results reveal that for each community-based goal attained by the older adult, the likelihood of hospital readmission decreases by 30%. This suggests that establishing community-based goals may enhance the effectiveness of TCP participation. These findings reiterate the importance of underlying mechanisms associated with community participation, namely physical activity and social connectedness to promote achievement of key TCP objectives such as independence, companionship and quality of life [

27,

28].

Our preliminary findings might also provide a strategic direction to generate robust evidence regarding community goal setting based on: (i) the effectiveness of setting goals in achieving TCP objectives, (ii) adoption among older adults, (iii) implementation across TCPs with different socio-cultural demographics and (iv) maintenance over time in TCP care.31 Future randomised controlled trials should primarily be planned to understand the effectiveness of setting community-based goals (versus home-based goals) to achieve improved health-related outcomes supported by increased incidental physical activity and social connectedness among older adults. The assessment of setting community-based goals in terms of acceptability, ease of implementation and chances of maintenance in the long term is also needed to determine the feasibility of uniformly incorporating goal-setting as a strategy in regular TCP care plan across Australia.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study’s conception and design. SS, AK, and NB performed material preparation, data collection and analysis. The first draft of the manuscript was written by AK and NB, and critically reviewed by SS and NR. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study obtained ethics approval from Metro South Health Research Ethics Board: Reference number HREC/2020/QMD/63442.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy reasons.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the contributions of Kasey Owen, Advanced Health Practitioner, Redland Hospital, Queensland Health, who helped with data management and data cleaning; Wendy Marshall, NUM Bayside TCP, Queensland Health, for helping export data from the transdata database; and, Doctor Elizabeth McCourt, Pharmacist, Department of Clinical Pharmacy, Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, for data management and obtaining ethics approval.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AUC |

Area Under the Curve |

| ICF |

International Classification of Functioning |

| ieMR |

Integrated electronic Medical Record |

| LOS |

Length of Stay |

| MBI |

Modified Barthel Index |

| OR |

Odds Ratio |

| QLD |

Queensland |

| RACF |

Residential Aged Care Facility |

| TCP |

Transition Care Program |

| URN |

Unique Record Number |

References

- Bailey, R.R. Goal Setting and Action Planning for Health Behavior Change. Am J Lifestyle Med 2019, 13, 615-618. [CrossRef]

- Gray, L.C.; Peel, N.M.; Crotty, M.; Kurrle, S.E.; Giles, L.C.; Cameron, I.D. How effective are programs at managing transition from hospital to home? A case study of the Australian transition care program. BMC Geriatrics 2012, 12, 6. [CrossRef]

- KPMG. Review of the Transition Care Programme. Department of Health Final Report; 2019.

- Fønss Rasmussen, L.; Grode, L.B.; Lange, J.; Barat, I.; Gregersen, M. Impact of transitional care interventions on hospital readmissions in older medical patients: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e040057. [CrossRef]

- Masters, S.; Halbert, J.; Crotty, M.; Cheney, F. What are the first quality reports from the Transition Care Program in Australia telling us? Australas J Ageing 2008, 27, 97-102. [CrossRef]

- Flinders Consulting. National evaluation of the Transition Care Program: final evaluation report; Department of Health (Australia): Canberra, Australia, 2008.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Twenty years of population change.; ABS: Canberra, 2020.

- Salih, S.A.; Peel, N.M.; Marshall, W. Using the I nternational C lassification of Functioning, Disability and Health framework to categorise goals and assess goal attainment for transition care clients. Australasian Journal on Ageing 2015, 34, E13-E16.

- Boland, N.; McCourt, E.; Owen, K.; Salih, S. Differences in Clients Who Develop Home-Based or Community-Based Goals in a Transition Care Program: A Retrospective Cohort Study. International Journal of Geriatrics and Gerontology 2023, 7.

- Beristain Iraola, A.; Álvarez Sánchez, R.; Hors-Fraile, S.; Petsani, D.; Timoleon, M.; Díaz-Orueta, U.; Carroll, J.; Hopper, L.; Epelde, G.; Kerexeta, J.; et al. User Centered Virtual Coaching for Older Adults at Home Using SMART Goal Plans and I-Change Model. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Kim, D.Y.; Sohn, M.K.; Lee, J.; Lee, S.G.; Shin, Y.I.; Kim, S.Y.; Oh, G.J.; Lee, Y.H.; Lee, Y.S.; et al. Determining the cut-off score for the Modified Barthel Index and the Modified Rankin Scale for assessment of functional independence and residual disability after stroke. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0226324. [CrossRef]

- Heller, G.; Seshan, V.E.; Moskowitz, C.S.; Gönen, M. Inference for the difference in the area under the ROC curve derived from nested binary regression models. Biostatistics 2017, 18, 260-274. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Almirall-Sánchez, A.; Mockler, D.; Adrion, E.; Domínguez-Vivero, C.; Romero-Ortuño, R. Hospital-associated deconditioning: Not only physical, but also cognitive. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2022, 37. [CrossRef]

- Salih, S.A.; Peel, N.M.; Enright, D.; Marshall, W. Physical Activity Levels of Older Persons Admitted to Transitional Care Programs: An Accelerometer-Based Study. Journal for the Measurement of Physical Behaviour 2019, 2, 263-267. [CrossRef]

- Borodulin, K.; Anderssen, S. Physical activity: associations with health and summary of guidelines. Food Nutr Res 2023, 67. [CrossRef]

- Warburton, D.E.; Nicol, C.W.; Bredin, S.S. Health benefits of physical activity: the evidence. Cmaj 2006, 174, 801-809. [CrossRef]

- Tudor-Locke, C.; Craig, C.L.; Brown, W.J.; Clemes, S.A.; De Cocker, K.; Giles-Corti, B.; Hatano, Y.; Inoue, S.; Matsudo, S.M.; Mutrie, N.; et al. How many steps/day are enough? for adults. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 2011, 8, 79. [CrossRef]

- Lear, S.A.; Hu, W.; Rangarajan, S.; Gasevic, D.; Leong, D.; Iqbal, R.; Casanova, A.; Swaminathan, S.; Anjana, R.M.; Kumar, R.; et al. The effect of physical activity on mortality and cardiovascular disease in 130 000 people from 17 high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries: the PURE study. Lancet 2017, 390, 2643-2654. [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Olds, T.; Curtis, R.; Dumuid, D.; Virgara, R.; Watson, A.; Szeto, K.; O'Connor, E.; Ferguson, T.; Eglitis, E.; et al. Effectiveness of physical activity interventions for improving depression, anxiety and distress: an overview of systematic reviews. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2023, 57, 1203-1209. [CrossRef]

- Sims, J.; Hill, K.; Hunt, S.; Haralambous, B. Physical activity recommendations for older Australians. Australas J Ageing 2010, 29, 81-87. [CrossRef]

- Burton, E.; Farrier, K.; Galvin, R.; Johnson, S.; Horgan, N.F.; Warters, A.; Hill, K.D. Physical activity programs for older people in the community receiving home care services: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Interv Aging 2019, 14, 1045-1064. [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.N.; Fields, S.M. Changes in older adults' impairment, activity, participation and wellbeing as measured by the AusTOMs following participation in a Transition Care Program. Aust Occup Ther J 2020, 67, 517-527. [CrossRef]

- Czaja, S.J.; Moxley, J.H.; Rogers, W.A. Social Support, Isolation, Loneliness, and Health Among Older Adults in the PRISM Randomized Controlled Trial. Front Psychol 2021, 12, 728658. [CrossRef]

- Holt-Lunstad, J.; Smith, T.B.; Layton, J.B. Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med 2010, 7, e1000316. [CrossRef]

- Gyasi, R.M.; Peprah, P.; Abass, K.; Pokua Siaw, L.; Dodzi Ami Adjakloe, Y.; Kofi Garsonu, E.; Phillips, D.R. Loneliness and physical function impairment: Perceived health status as an effect modifier in community-dwelling older adults in Ghana. Preventive Medicine Reports 2022, 26, 101721. [CrossRef]

- Matuska, K.; Giles-Heinz, A.; Flinn, N.; Neighbor, M.; Bass-Haugen, J. Outcomes of a pilot occupational therapy wellness program for older adults. Am J Occup Ther 2003, 57, 220-224. [CrossRef]

- Gough, C.; Lewis, L.K.; Barr, C.; Maeder, A.; George, S. Community participation of community dwelling older adults: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 612. [CrossRef]

- Lindsay Smith, G.; Banting, L.; Eime, R.; O’Sullivan, G.; van Uffelen, J.G.Z. The association between social support and physical activity in older adults: a systematic review. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 2017, 14, 56. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).