Submitted:

15 April 2025

Posted:

16 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- -

- Uncertainty and quality of data: Accurate forecasting relies on complete, reliable, and up-to-date data on morbidity, demographics, and healthcare accessibility. However, data is often incomplete, outdated, or error-prone, particularly in developing countries or when accounting for informal healthcare sectors [35]

- -

- Dynamic variability of factors: The volume of healthcare services depends on factors like income levels, government policies, epidemiological conditions, and technological innovations, which can change rapidly. Traditional models often assume stability, reducing their applicability in real-world settings [36]

- -

- Complexity of human behavior: Patient behavior (e.g., seeking care, choosing between public and private services, self-treatment) is difficult to predict and formalize, posing challenges for models that cannot fully integrate subjective factors [30]

- -

- Limitations of existing forecasting methods: Methods like time series, exponential smoothing, or Markov chains have inherent weaknesses. For instance, time series struggle with long-term forecasts when trends shift, while Markov chains assume constant transition probabilities, which is rarely realistic in healthcare [37]

- -

- Integration of new technologies and their impact: The rapid rise of artificial intelligence (AI), telemedicine, and wearable devices is reshaping healthcare demand, but their effects are insufficiently studied and hard to quantify in models. [38]

- -

- Regional and social heterogeneity: Differences in healthcare access across regions and social groups (e.g., income, education levels) complicate the development of universal models. Forecasts based on averaged data often fail to reflect local specifics [29]

- -

- Impact of external shocks and crises: Economic downturns, sanctions, epidemics, or conflicts drastically alter healthcare supply and demand. Most models are not equipped to handle such disruptions [27]

- -

- Ethical and legal constraints: Using big data and AI for forecasting faces restrictions related to patient privacy and healthcare regulations, limiting data access and model development [39]

- -

- Possible solutions to these problems include the creation of centralized databases with regular updates and integration of information from different sources (public clinics, private sector, insurance companies), combining traditional methods with machine learning to account for nonlinear dependencies and adapt to changes, developing forecasts taking into account different scenarios (e.g. economic downturn, epidemic) to increase the sustainability of models, as well as developing regional models taking into account the specifics of infrastructure and demographics.

- -

- age-specific mortality rate forecasting

- -

- birth rate forecasting

- -

- population forecasting

- -

- total morbidity forecasting

- -

- Internists and Pediatricians forecasting

- -

- financial need calculation

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

- -

- Historical population data (1991–2023), disaggregated by age, sex, and year.

- -

- Annual birth rates per 1,000 total population for the same period.

- -

- Age-specific mortality rates per 1,000 population for each year from 1991 to 2023.

- -

- Annual number of internal medicine physicians (internists) for 1991-2023

- -

- Annual number of pediatricians for 1991-2023

- -

- Annual total healthcare costs per capita for 1991-2023 (US$)

- -

- These data were sourced from Kazakhstan national statistics bureau.

2.2. Markov Chain-Based Population Forecasting Methodology

- -

- remaining in the same age group.

- -

- transitioning to the next age group due to aging.

- -

- exiting the system due to mortality.

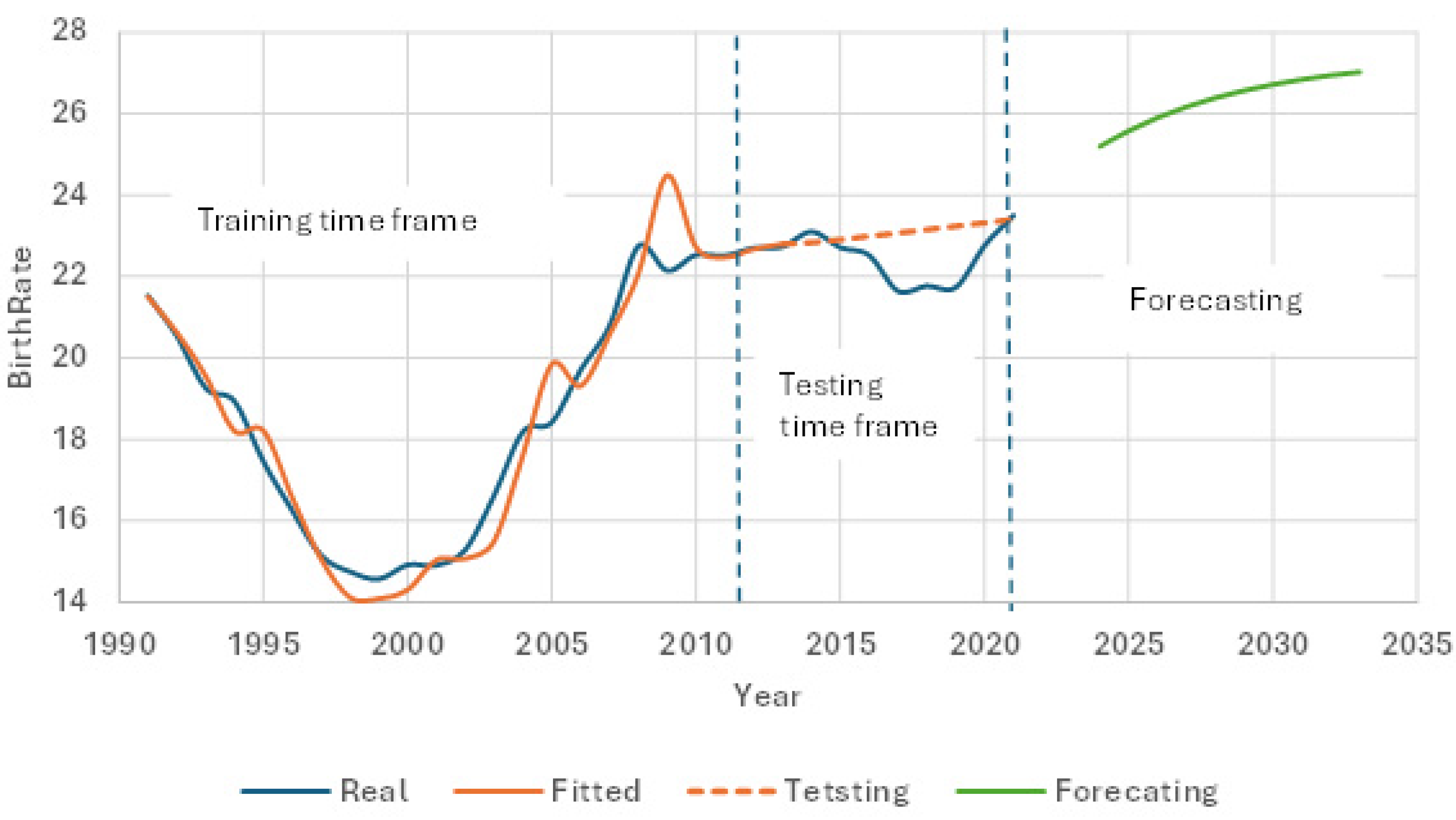

2.3. Birth Rate Forecasting

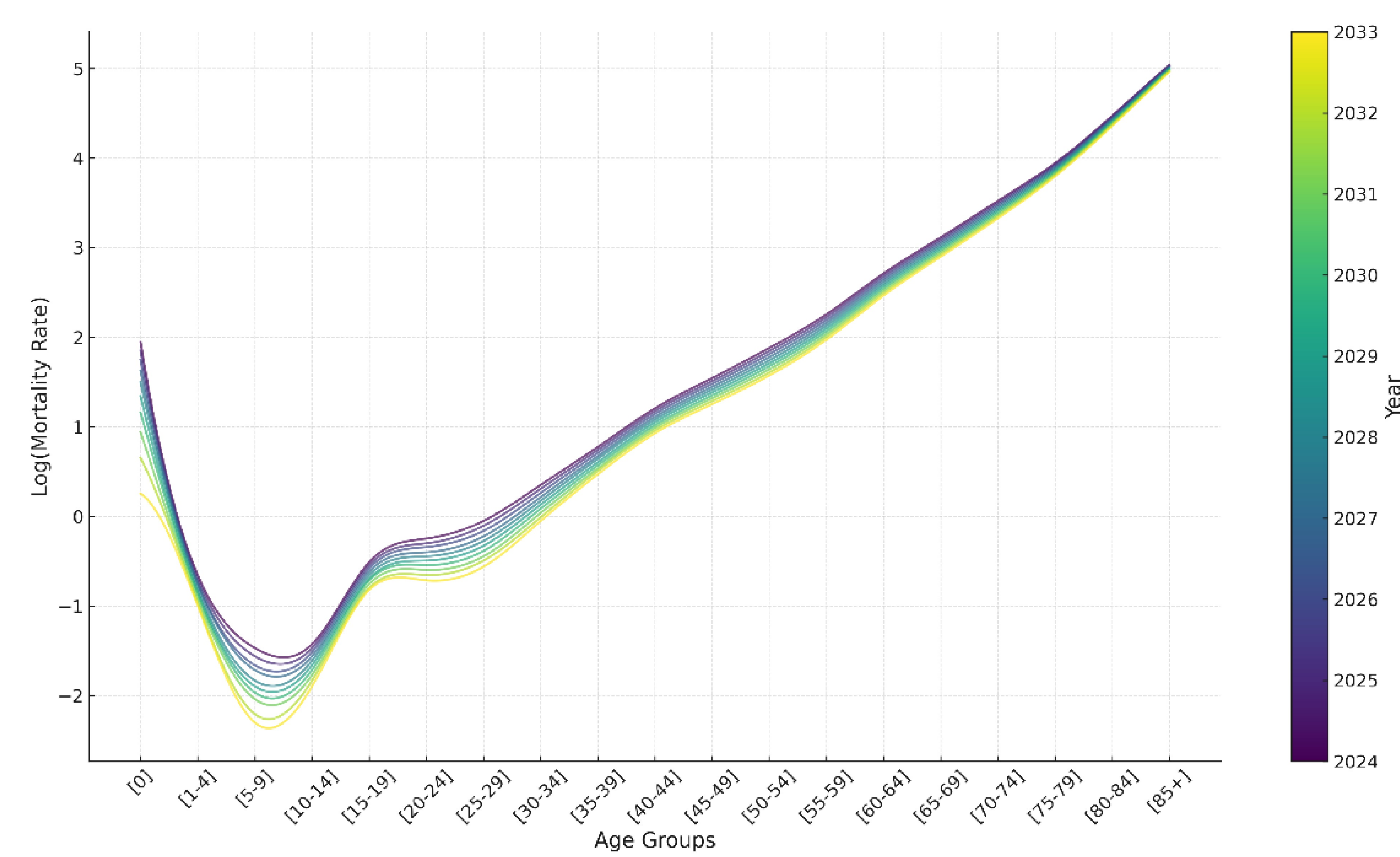

2.4. Age-specific Mortality Rate Forecasting

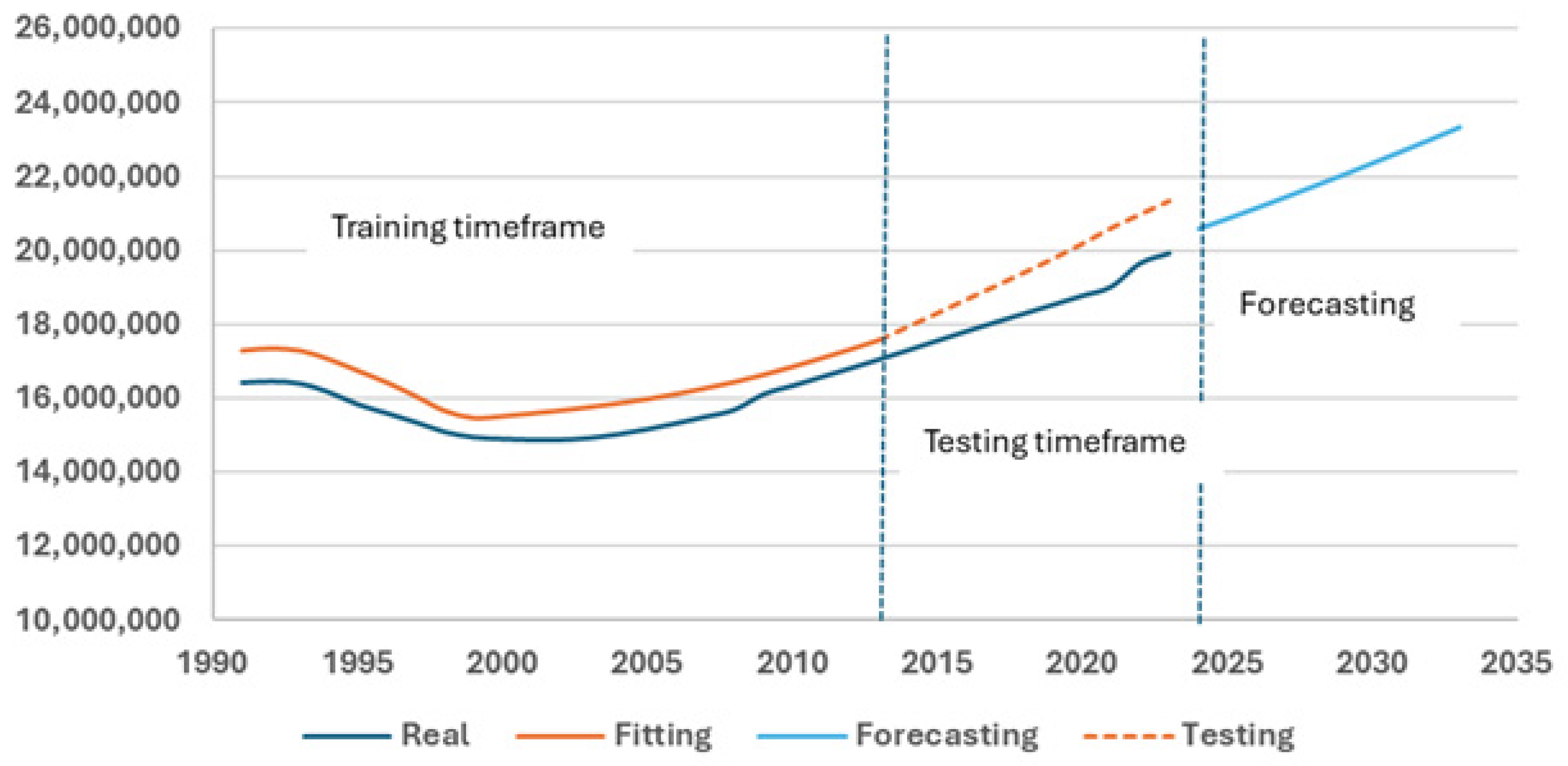

2.5. Population Forecasting

2.6. Healthcare Demand Forecasting

2.7. Model Fitting and Validation

3. Results

3.1. Population Model Fitting and Validity

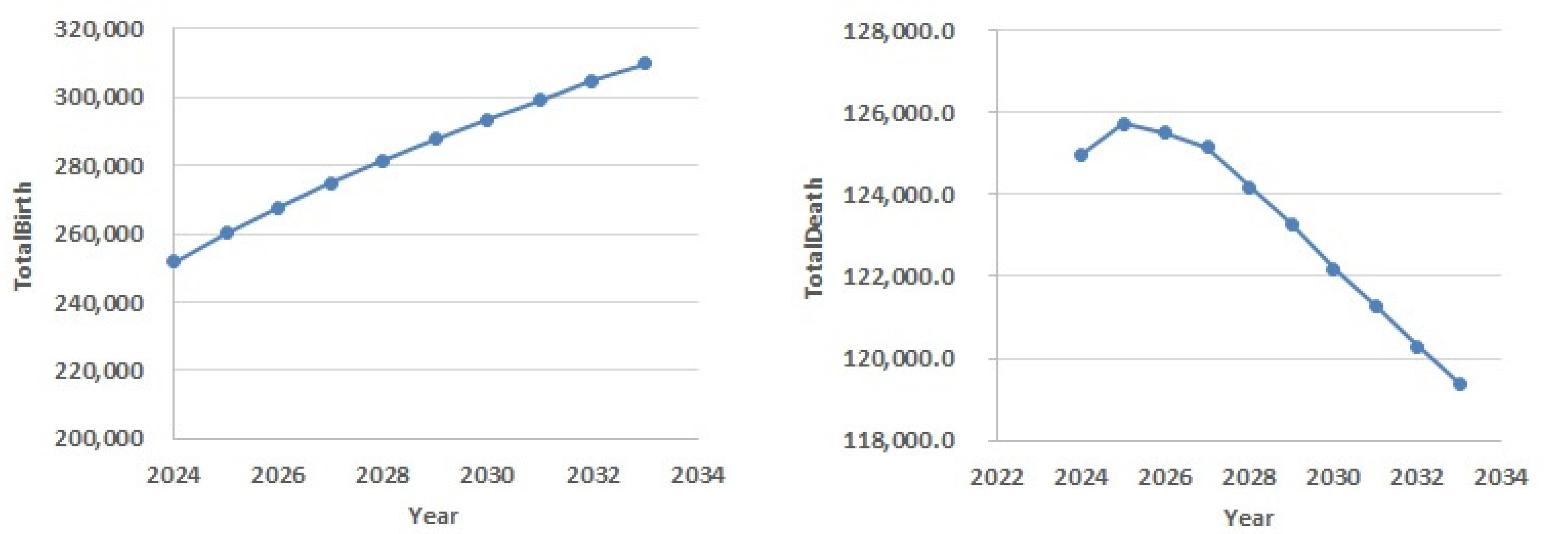

3.2. Population Forecast to 2033

3.2.1. Birth Rate Forecasting Model

3.2.2. Mortality Forecasting Model

3.3.3. Population Forecasting Model

| Age | 0-14 | 15-64 | 65-85+ |

| Year | % | ||

| 2023 | 29.5 | 62.2 | 8.3 |

| 2024 | 22.4 | 65.7 | 12.0 |

| 2025 | 24.3 | 64.4 | 11.3 |

| 2026 | 26.2 | 63.2 | 10.7 |

| 2027 | 28.0 | 61.9 | 10.1 |

| 2028 | 29.7 | 60.8 | 9.5 |

| 2029 | 31.4 | 59.6 | 9.0 |

| 2030 | 33.0 | 58.4 | 8.6 |

| 2031 | 34.6 | 57.3 | 8.1 |

| 2032 | 36.1 | 56.2 | 7.7 |

| 2033 | 37.5 | 55.2 | 7.3 |

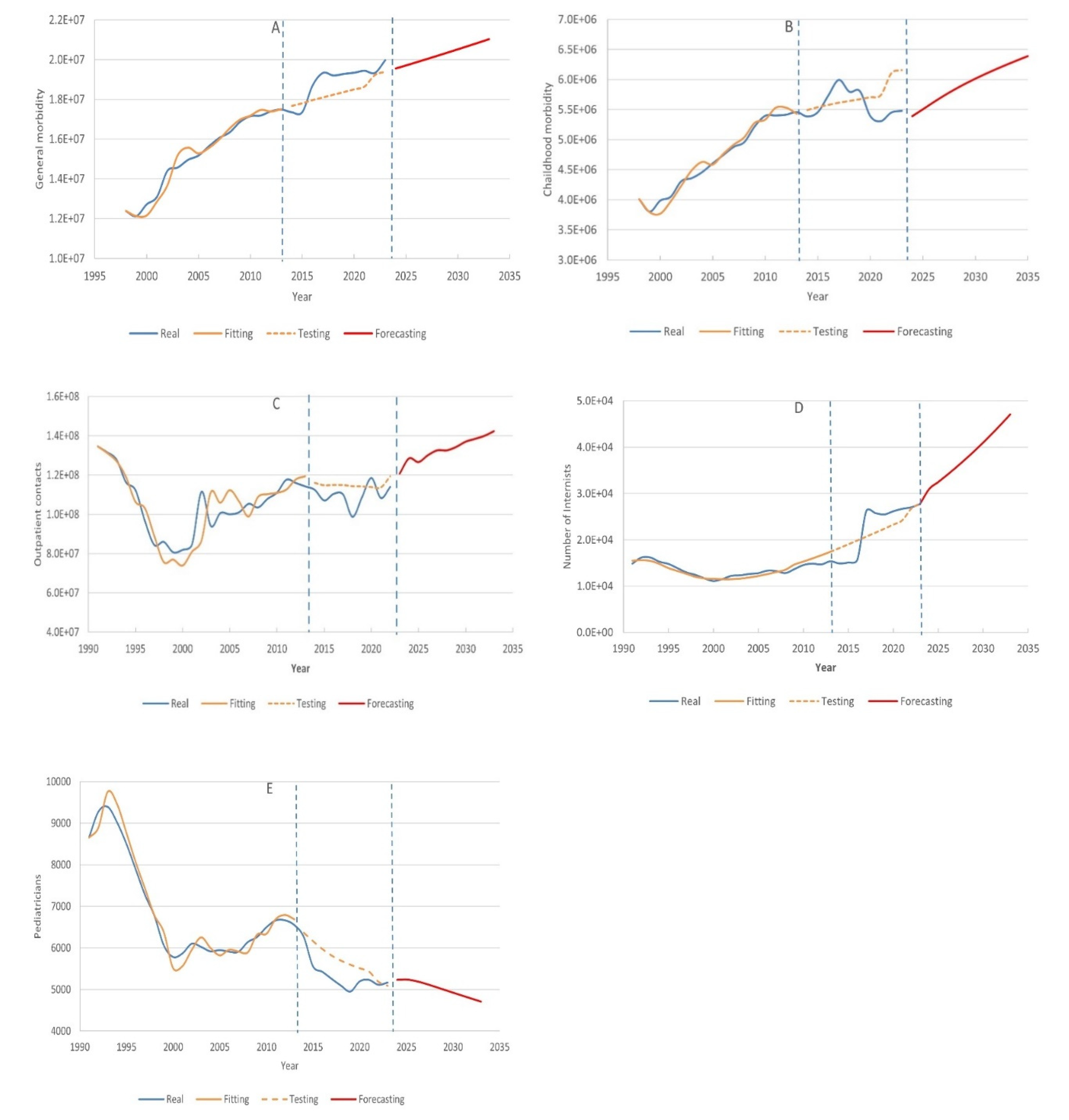

3.3. Assessment of Kazakhstan Healthcare Demand to 2033

- Intervention Indicator: Binary variable (0 for 1991–2016, 1 for 2017 onward).

- Population: Exogenous variable for demographic influence.

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jalalpour M, Gel Y, Levin S. Forecasting demand for health services: Development of a publicly available toolbox. Operations Research for Health Care 2015;5:1–9. [CrossRef]

- Soyiri IN, Reidpath DD. An overview of health forecasting. Environ Health Prev Med 2013;18:1–9. [CrossRef]

- Lee JT, Crettenden I, Tran M, Miller D, Cormack M, Cahill M, et al. Methods for health workforce projection model: systematic review and recommended good practice reporting guideline. Hum Resour Health 2024;22:25. [CrossRef]

- Mushasha R, El Bcheraoui C. Comparative effectiveness of financing models in development assistance for health and the role of results-based funding approaches: a scoping review. Global Health 2023;19:39. [CrossRef]

- Merkuryeva G, Valberga A, Smirnov A. Demand forecasting in pharmaceutical supply chains: A case study. Procedia Computer Science 2019;149:3–10. [CrossRef]

- Keskinocak P, Savva N. A review of the healthcare-management (Modeling) literature published in manufacturing & service operations management. M&SOM [Internet]. 2020 Jan [cited 2025 Apr 1];22(1):59–72. [CrossRef]

- McRae S. Long-term forecasting of regional demand for hospital services. Operations Research for Health Care [Internet]. 2021 Mar [cited 2025 Apr 1];28:100289. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2211692321000059.

- Jones SA, Joy MP, Pearson J. [No title found]. Health Care Management Science [Internet]. 2002 [cited 2025 Apr 1];5(4):297–305. [CrossRef]

- Forecasting demand for regional healthcare. In Spatial and Syndromic Surveillance for Public Health John Wiley & Sons, N-Y, 2005(pp. 123-140).

- Milner PC. Ten-year follow-up of ARIMA forecasts of attendances at accident and emergency departments in the Trent region. Statist Med 1997;16:2117–25. [CrossRef]

- Overview of the cohort-component method. In: State and Local Population Projections. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2002. p. 43–8. [CrossRef]

- Alders M, Keilman N, Cruijsen H. Assumptions for long-term stochastic population forecasts in 18 European countries: Hypothèses de projections stochastiquesàlong terme des populations de 18 pays européens. Eur J Population . 2007 Mar;23(1):33–69. Available from: https://link.springer.com/. [CrossRef]

- Raftery AE, Ševčíková H. Probabilistic population forecasting: Short to very long-term. International Journal of Forecasting . 2023 Jan;39(1):73–97. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0169207021001394.

- Basellini U, Camarda CG, Booth H. Thirty years on: A review of the Lee–Carter method for forecasting mortality. International Journal of Forecasting . 2023 Jul;39(3):1033–49. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0169207022001455.

- Hyndman RJ, Shahid Ullah Md. Robust forecasting of mortality and fertility rates: A functional data approach. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis . 2007 Jun;51(10):4942–56. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0167947306002453.

- Nikitovic V. Functional data analysis in forecasting Serbian fertility. STANOVNISHTVO . 2011;49(2):73–89. Available from: https://idn.org.rs/ojs3/stanovnistvo/index.php/STNV/article/view/127.

- Patil RS, Ubale DrPV. A coherent functional demographic model approach for stochastic population forecasting. Int J Stat Appl Math . 2022 May 1;7(3):129–35. Available from: https://www.mathsjournal.com/archives/2022/vol7/issue3/PartB/7-3-10.

- Barker RJ, Sauer JR. Modelling population change from time series data. In: McCullough DR, Barrett RH, editors. Wildlife 2001: Populations . Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 1992 . p. 182–94. [CrossRef]

- Bravo, JM & Coelho, E 2019, 'Forecasting subnational demographic data using seasonal time series methods', Atas da Conferencia da Associacao Portuguesa de Sistemas de Informacao. Forecasting subnational demographic data using seasonal time series methods. / Bravo, Jorge M.; Coelho, Edviges. In: Atas da Conferencia da Associacao Portuguesa de Sistemas de Informacao, 2019.

- Levantesi S, Pizzorusso V. Application of machine learning to mortality modeling and forecasting. Risks . 2019 Feb 26 [cited 2025 Apr 1];7(1):26. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9091/7/1/26.

- Tzitiridou-Chatzopoulou M, Zournatzidou G, Kourakos M. Predicting future birth rates with the use of an adaptive machine learning algorithm: a forecasting experiment for scotland. IJERPH . 2024 Jun 27 [cited 2025 Apr 1];21(7):841. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/21/7/841.

- Tanmoy FM, Hossain Z, Tasfia O, Abrar Hamim Md, Sadekur Rahman Md, Tarek Habib Md. Machine learning modeling for population forecasting. In: Kalam A, Mekhilef S, Williamson SS, editors. Innovations in Electrical and Electronics Engineering . Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore; 2025. p. 213–28. [CrossRef]

- Şahinarslan FV, Tekin AT, Çebi F. Application of machine learning algorithms for population forecasting. IJDS 2021;6:257. [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, D.J., Stochastic Models for Social Processes. 3rd ed., Wiley, New York, USA, 1982.

- Lee RD, Tuljapurkar S. Stochastic Population Forecasts for the United States: Beyond High, Medium, and Low. Journal of the American Statistical Association 1994;89:1175–89. [CrossRef]

- Alho, J.M., Spencer, B.D., Statistical Demography and Forecasting, Springer, New York, USA, 2005.

- Chiang, C.L., An Introduction to Stochastic Processes in Biostatistics, Wiley, New York, USA, 1980.

- Keyfitz N. On Future Population. Journal of the American Statistical Association 1972;67:347–63. [CrossRef]

- Billari FC, Prskawetz A, editors. Agent-based computational demography: using simulation to improve our understanding of demographic behaviour . Heidelberg: Physica-Verlag HD; 2003. (Müller WA, Bihn M, editors. Contributions to Economics). [CrossRef]

- https://www.undp.org/kazakhstan/press-releases/who-and-undp-join-forces-kazakhstan-new-initiative-boost-pandemic-preparedness-and-health-infrastructure.

- https://www.adb.org/projects/57315-001/main.

- Saduyeva F., Vlassova A., Kalbekov Zh. Analysis of satisfaction with hospitalization in the gynecology department: service design project. Medicine and ecology. 2024;(4):124-130. (In Russ.). [CrossRef]

- Interrupted time series analysis of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and compulsory social health insurance system on fertility rates: a study of live births in Kazakhstan, 2019–2023. Indira Karibayeva, Sharapat Moiynbayeva, Valikhan Akhmetov, Sandugash Yerkenova, Kuralay Shaikova, Gaukhar Moshkalova, Dina Mussayeva, Bibinur Tarakova Front Public Health. 2024; 12.

- Semenova Y, Pivina L, Khismetova Z, Auyezova A, Nurbakyt A, Kauysheva A, Ospanova D, Kuziyeva G, Kushkarova A, Ivankov A, Glushkova N. Anticipating the Need for Healthcare Resources Following the Escalation of the COVID-19 Outbreak in the Republic of Kazakhstan. J Prev Med Public Health. 2020 Nov;53(6):387-396. [PubMed]

- Smith, S.K., Tayman, J., Swanson, D.A., 2001. "State and local population projections: Methodology and analysis," Springer Science & Business Media.

- Sanderson, W.C., Scherbov, S., Lutz, W., O'Neill, B. (2004). Applications of probabilistic population forecasting. In: The End of World Population Growth in the 21st Century. Eds. Lutz, W., Sanderson, W.C. & Scherbov, S. , pp. 85-120. London, Taylor & Francis. [CrossRef]

- Land KC. Methods for National Population Forecasts: A Review. Journal of the American Statistical Association 1986;81:888–901. [CrossRef]

- Topol, E.J. High-performance medicine: the convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nat Med 25, 44–56 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Mittelstadt BD, Floridi L. The Ethics of Big Data: Current and Foreseeable Issues in Biomedical Contexts. Sci Eng Ethics 2016;22:303–41. [CrossRef]

- Huang Y, Xu C, Ji M, Xiang W, He D. Medical service demand forecasting using a hybrid model based on ARIMA and self-adaptive filtering method. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak . 2020 Dec [cited 2025 Apr 1];20(1):237. Available from: https://bmcmedinformdecismak.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12911-020-01256-1.

- Perrott GStJ, Holland DF. Population Trends and Problems of Public Health. Milbank Quarterly 2005;83:569–608. [CrossRef]

| Year | Population | Predicted_Population | Absolute_Error | APE (%) |

| 2014 | 17816285 | 17919559.35 | 103274.3519 | 0.58 |

| 2015 | 18084169 | 18283637.78 | 199468.7808 | 1.10 |

| 2016 | 18363599.5 | 18652202.51 | 288603.0074 | 1.57 |

| 2017 | 18651931 | 19012257.6 | 360326.597 | 1.93 |

| 2018 | 18932726.5 | 19382085.49 | 449358.9948 | 2.37 |

| 2019 | 19209555 | 19758244.43 | 548689.4309 | 2.86 |

| 2020 | 19482117 | 20161328.53 | 679211.5306 | 3.49 |

| 2021 | 19743603 | 20585776.19 | 842173.1883 | 4.27 |

| 2022 | 20034609 | 20959048.86 | 924439.8649 | 4.61 |

| 2023 | 20330104 | 21317695.14 | 987591.1431 | 4.86 |

| Model | Fitting MAPE | Testing MAPE |

| General morbidity model | 1.6 | 3.7 |

| Child morbidity model | 1.7 | 5.6 |

| Outpatient contacts model | 5.9 | 5.9 |

| Internists number model | 2.9 | 2.8 |

| Pediatricians number model | 2.2 | 7.0 |

| Year | Total Population | General morbidity (absolute value) | General childhood morbidity (absolute value) | Outpatient contacts | Internists number | Pediatricians | Total health care costs, US$ |

| 2024 | 20,599,934 | 13,258,205 | 16050229 | 128,445,597 | 28,744 | 5,232 | 9,166,970,630 |

| 2025 | 20,878,139 | 13,512,632 | 16275963 | 126,578,353 | 29,195 | 5,240 | 9,290,771,855 |

| 2026 | 21,163,924 | 13,773,990 | 16507847 | 130,087,539 | 29,655 | 5,204 | 9,417,946,180 |

| 2027 | 21,456,581 | 14,041,634 | 16745307 | 132,588,596 | 30,121 | 5,143 | 9,548,178,545 |

| 2028 | 21,755,514 | 14,315,017 | 16987860 | 132,562,648 | 30,594 | 5,071 | 9,681,203,730 |

| 2029 | 22,060,460 | 14,593,900 | 17235291 | 134,337,063 | 31,073 | 4,997 | 9,816,904,700 |

| 2030 | 22,370,980 | 14,877,879 | 17487245 | 137,009,352 | 31,558 | 4,923 | 9,955,086,100 |

| 2031 | 22,686,915 | 15,166,811 | 17743593 | 138,454,550 | 32,048 | 4,850 | 10,095,677,175 |

| 2032 | 23,008,129 | 15,460,571 | 18004224 | 140,018,868 | 32,543 | 4,778 | 10,238,617,405 |

| 2033 | 23,334,397 | 15,758,953 | 18268956 | 142,389,116 | 33,043 | 4,706 | 10,383,806,665 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).