Submitted:

15 April 2025

Posted:

16 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Natural Fibers

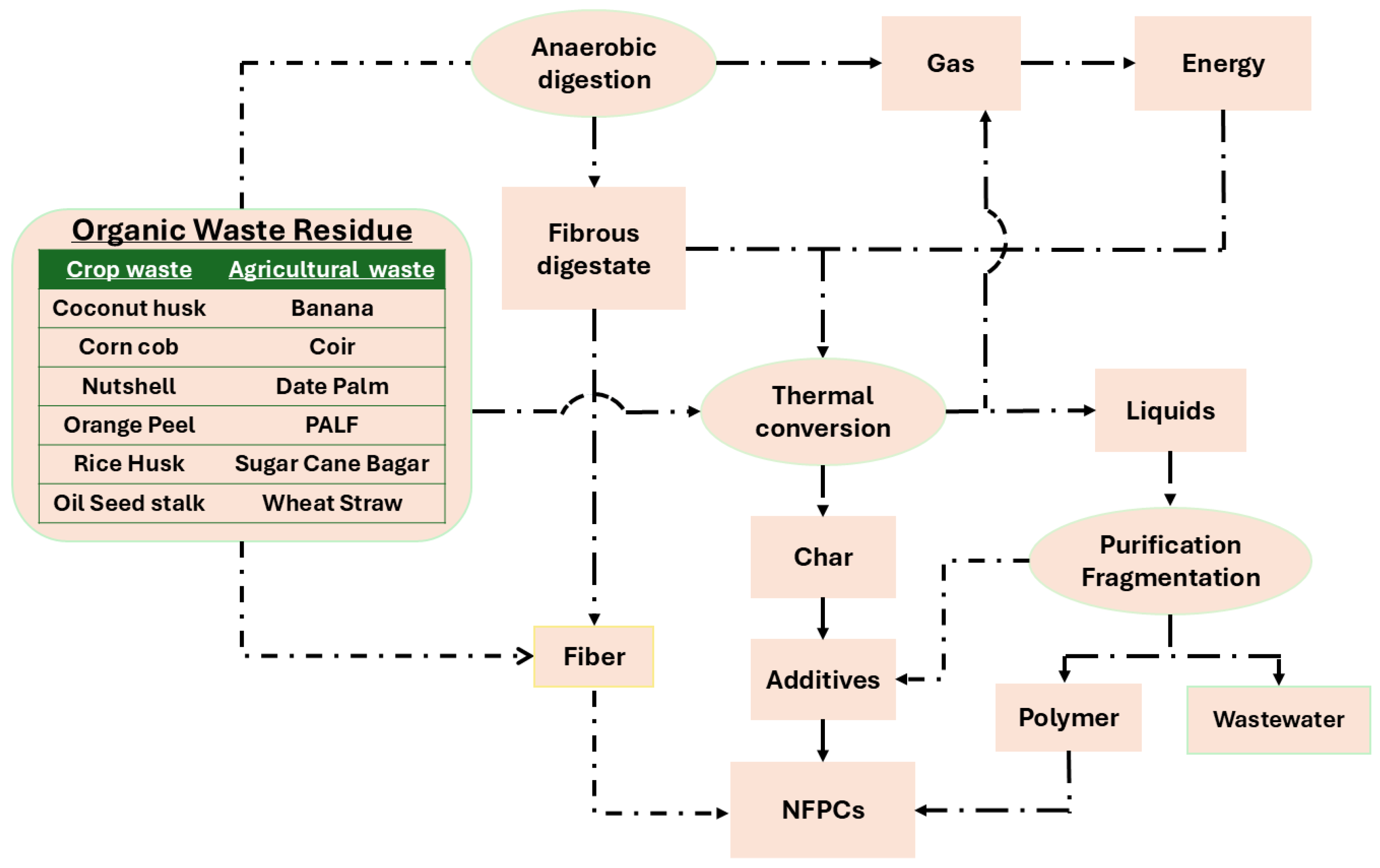

2.1. Sources of Natural Fiber

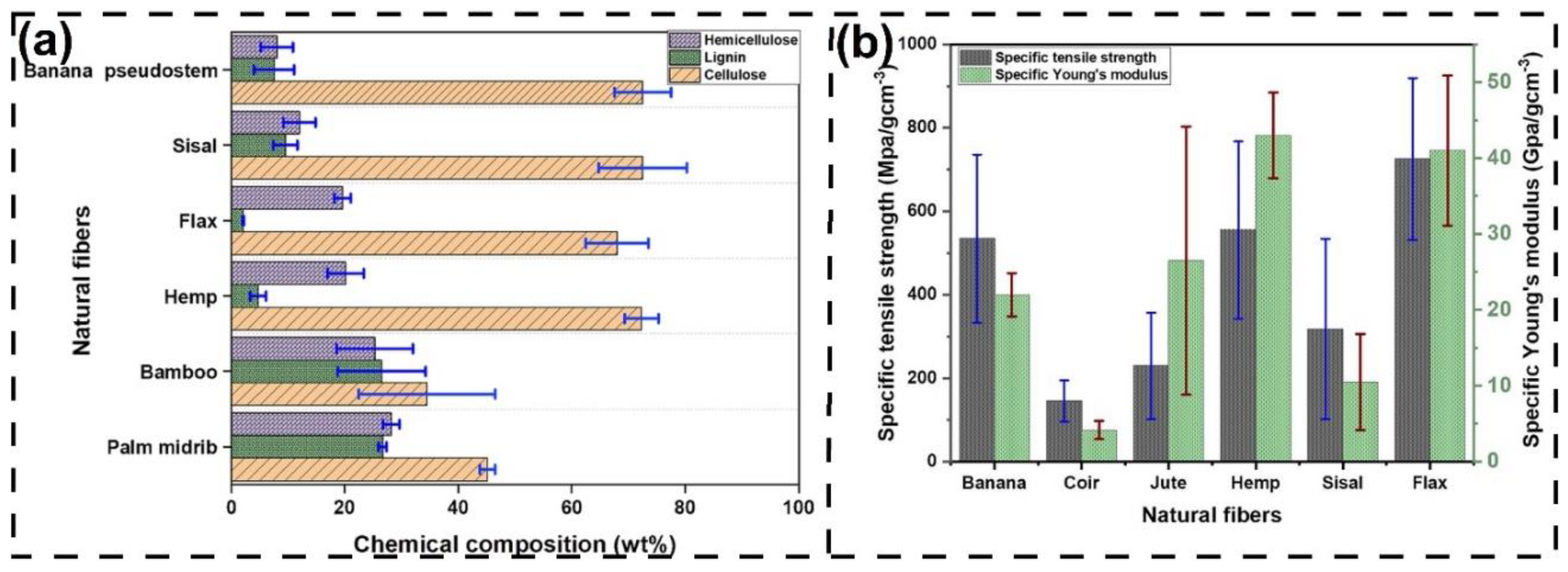

2.2. Constituents and Anatomy of Plant Based Natural Fiber/Filler

3. Different Agricultural Waste Based Natural Fiber/Filler

3.1. Banana Fiber

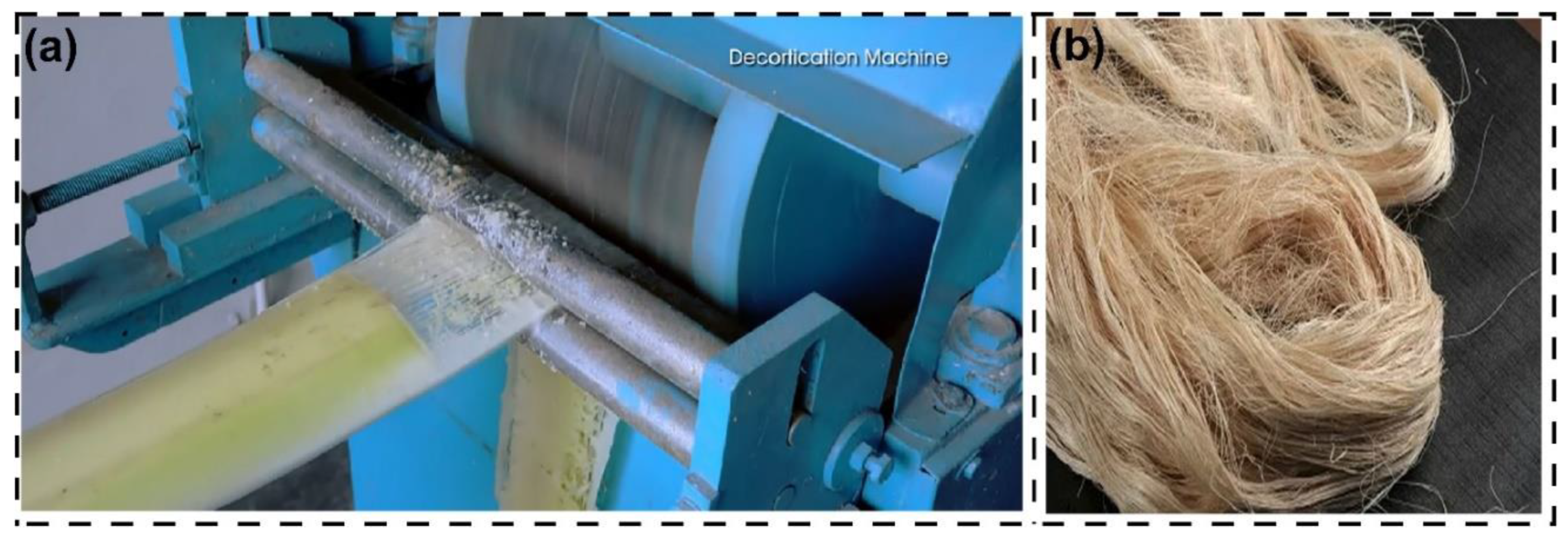

3.1.1. Extraction of Banana Fiber

3.1.2. Properties of Banana Fiber

3.1.3. Properties of Banana Fiber Reinforced Composites

3.2. Coir Fiber

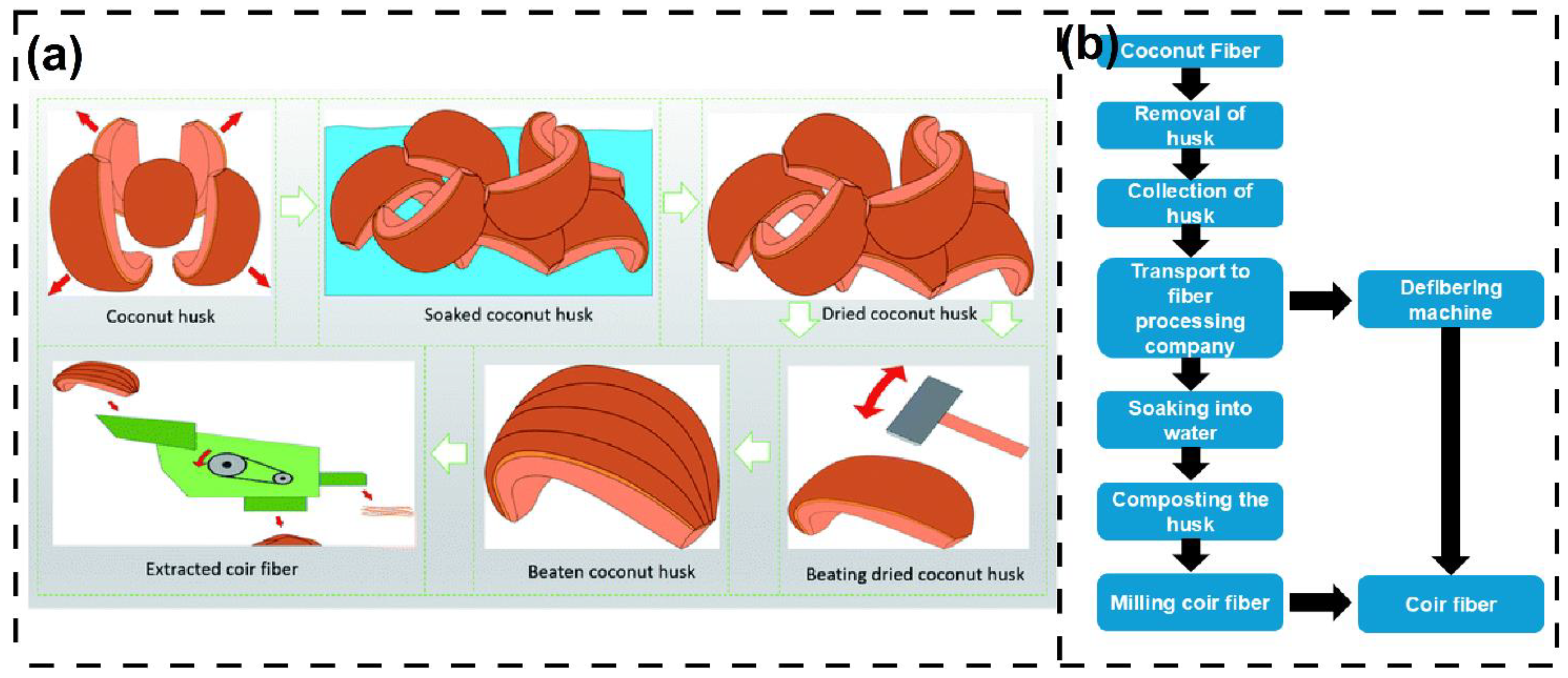

3.2.1. Extraction of Coir

3.2.2. Properties of Coir Fiber

3.2.3. Properties of Coir Fiber Reinforced Composites

3.3. Corncob Waste

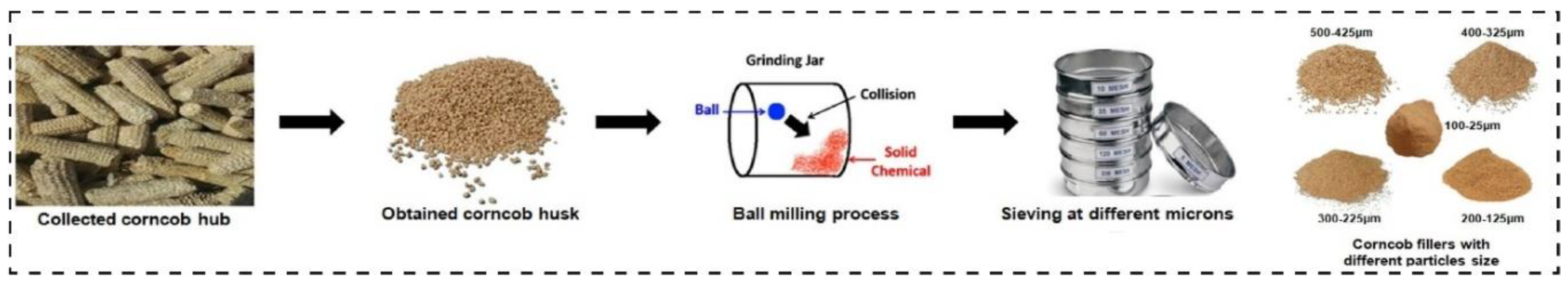

3.3.1. Preparation of Corn filler/fiber

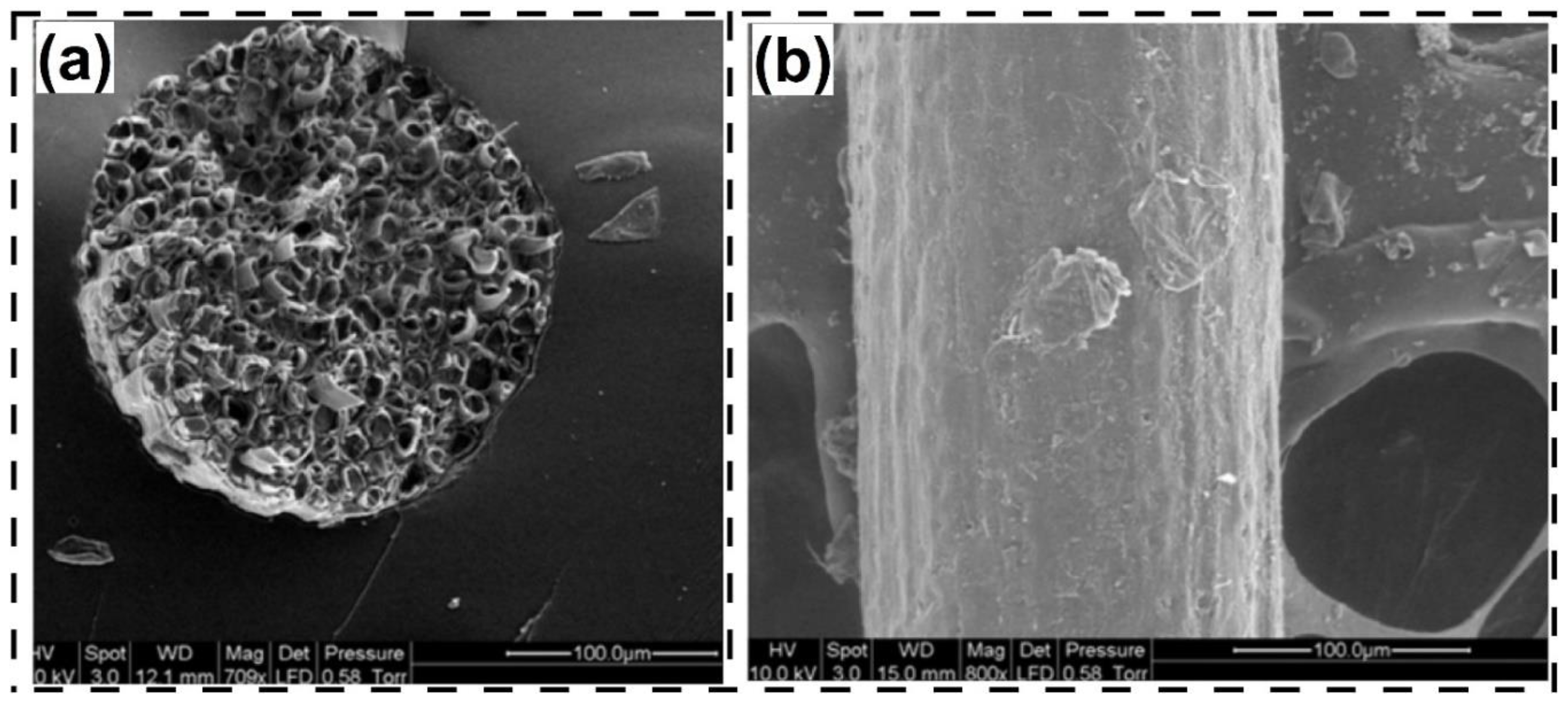

3.3.2. Properties of Corncob Filler/Fiber

3.3.3. Properties of Corncob Reinforced Composite

3.4. Date Plam Fiber

3.4.1. Extraction of Date Plam Fiber

3.4.2. Properties of Date Plam Fiber

3.4.3. Properties of Date Palm Fiber Reinforced Composite

3.5. Pineapple Leaf Fiber

3.5.1. Extraction of PALF

3.5.2. Properties of PALF

3.5.3. Properties of PALF Reinforced Composite

3.6. Sugarcane Bagasse Fiber/Filler

3.6.1. Extraction of Sugarcane Fiber

3.6.2. Properties of Sugarcane Fiber

3.6.3. Properties of Sugarcane Fiber Reinforced Composite

4. Application of Different Biocomposites for Automobile Interior Applications

4.1. Natural Fibers/Fillers in Biocomposites for Automotive Applications

4.2. Biocomposites in Automobiles: Market Trends and Sustainability

4.3. Future Scope of Agriculture Waste Biocomposite in Electric Vehicle (EV)

- Enhancing sustainability by supporting circular economy philosophy: Using agricultural waste-based biomass to reinforce polymers offers a sustainable alternative to synthetic materials. These biocomposites reduce reliance on petroleum-based plastics, minimizing environmental impact and helping meet stringent sustainability regulations in the automotive sector. Additionally, repurposing waste materials promotes a circular economy, tackling the growing issue of agricultural and food waste in India, which contributes to air and water pollution in major cities like New Delhi.

- Light weight energy efficient materials: Agricultural waste-based biomass is lightweight, with a lower density than traditional polymer matrices. Reinforcing polymers with these low-density materials not only reduces the overall weight of the vehicle but also enhances various mechanical properties, helping maintain the vehicle’s structural integrity. This weight reduction improves the driving range and boosts the energy efficiency of electric vehicles (EVs).

- Acoustic and thermal insulator: Agricultural and food wastes, such as date palm and coir fibers, exhibit excellent thermal and acoustic insulation properties, making them ideal for automobile interior applications. These features enhance passenger comfort in electric vehicles (EVs), providing better temperature regulation and noise reduction for a more enjoyable driving experience.

- Customization through aesthetic design: Now a days peoples are looking for customized design inside their automobiles, these kinds of biocomposites can be engineered by incorporating eco-friendly design philosophies of EVs interior.

- Hybridization and advanced functionalization: Incorporating advanced fillers like nanocellulose and graphene alongside agro/food waste-based biomass can significantly enhance fire resistance, mechanical properties, moisture sensitivity, and UV stability. This combination results in materials with an excellent strength-to-weight ratio, making them ideal for high-performance applications in electric vehicles (EVs).

- Industrial adaptation, market trends and regulatory support: Government regulations increasingly emphasize reducing carbon emissions and incorporating renewable materials in automobile manufacturing. Additionally, consumer demand for sustainable vehicles is on the rise, making bio-based or green composites a strategic material choice for automakers. The European Union’s Green Deal is one such initiative aimed at promoting sustainable automotive practices, encouraging the shift toward eco-friendly materials in vehicle production.

4.4. Challenges and Future Research Direction on Waste Based Biocomposites for EV Interiors

- Fiber matrix interfacial interaction: Natural fibers are inherently hydrophilic, while most polymers are hydrophobic. This contrasting nature leads to poor interfacial interaction between the fibers and the matrix in composites. In a composite material, the matrix serves as a binder, transmitting load uniformly from the matrix to the reinforcing fibers. However, when the interfacial interaction is weak, the load transfer becomes inefficient, resulting in a reduction in the mechanical properties of the composite. To address this issue, many researchers use alkalization to enhance the interfacial bonding between fibers and matrix materials. Additionally, other surface treatments, such as silane or enzymatic treatments, may serve as promising directions for future research. For a more sustainable approach, eco-friendly treatments like alkaline water treatment can also be explored. However, challenges remain in optimizing chemical treatment concentrations and addressing variations in surface chemistry, which significantly impact composite fabrication. Establishing proper standards for these treatments is crucial and may be one of the major research works to achieving consistent and effective results.

- Dimensional stability and moisture absorption behaviour: The hydrophilic nature of lignocellulosic materials is responsible for the moisture absorption observed in agricultural and food waste. This property not only affects the fibers themselves but also impacts the water uptake behavior of biocomposites, leading to swelling and dimensional instability. To address this issue, future research should focus on strategies to reduce the moisture absorption of these fibers. Potential approaches include hybridizing natural fibers with a small proportion of synthetic fibers or developing hydrophobic coatings for the fibers. These methods could significantly improve the dimensional stability and durability of biocomposites, offering promising directions for sustainable material development.

- Optimization of mechanical properties: The reinforcement of waste biomass exhibits lower mechanical strength compared to traditional synthetic fibers or fillers. Therefore, optimizing the biomass reinforcement percentage is crucial. Additionally, hybridization with nano- or micro-fillers offers a promising approach to enhance the mechanical properties of the developed composites. Significant research can be conducted on incorporating various organic and inorganic fillers alongside biomass fibers to achieve desirable properties.

- Quality control through standardization: Most biomaterials are adaptive in nature, leading to variations in their properties. For mass production, it is essential to standardize material variability, including fiber diameter, length, and composition. Extensive research is needed to establish standardized testing protocols and define industrial requirements. Further studies on these properties will facilitate global acceptance and regulatory compliance.

- Development towards scalable process: Composites with waste-based biofibers can be manufactured using thermoplastic polymers through injection molding and 3D printing or with thermosetting polymers via hand lay-up and compression molding techniques. While these methods are well established, their standardization for large-scale industrial production remains limited. Extensive research is needed to enhance process scalability and industrial feasibility. Developing an efficient supply chain is essential to bridge the gap between laboratory-scale innovation and market-ready products. This involves streamlining the transition through industrial collaboration, ensuring scalability, and optimizing logistics for commercial viability.

- End life management and recyclability analysis: Biocomposites or green composites are not fully biodegradable; instead, they are better described as biocompostable. Extensive research is needed on end-of-life management strategies for these materials. Additionally, a significant research gap exists in life cycle analysis and understanding how their properties change under varying natural conditions such as pressure, temperature, and humidity.

- Integration of specific properties required for EVs and Smart vehicle: The next generation of electric vehicles should be smarter, featuring self-health monitoring, compatibility with electronic equipment, superior shock and sound absorption, and an advanced thermal management architecture. Research is needed to explore how these properties can be achieved using waste-based materials in future automotive applications.

5. Conclusion

CRediT Authorship Contribution Statement

Declaration of Competing Interest

Acknowledgments

Data Availability

References

- Oh E, Godoy Zúniga MM, Nguyen TB, Kim B-H, Trung Tien T, Suhr J. Sustainable green composite materials in the next-generation mobility industry: review and prospective. Advanced Composite Materials 2024:1–52. [CrossRef]

- Choi JY, Jeon JH, Lyu JH, Park J, Kim GY, Chey SY, et al. Current Applications and Development of Composite Manufacturing Processes for Future Mobility. International Journal of Precision Engineering and Manufacturing - Green Technology 2023;10:269–91. [CrossRef]

- Tang C, Tukker A, Sprecher B, Mogollón JM. Assessing the European Electric-Mobility Transition: Emissions from Electric Vehicle Manufacturing and Use in Relation to the EU Greenhouse Gas Emission Targets. Environ Sci Technol 2023;57:44–52. [CrossRef]

- Shahzad M, Shafiq MT, Douglas D, Kassem M. Digital Twins in Built Environments: An Investigation of the Characteristics, Applications, and Challenges. Buildings 2022;12. [CrossRef]

- Pelegov D V., Chanaron JJ. Electric Car Market Analysis Using Open Data: Sales, Volatility Assessment, and Forecasting. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2023;15. [CrossRef]

- İnci M, Büyük M, Demir MH, İlbey G. A review and research on fuel cell electric vehicles: Topologies, power electronic converters, energy management methods, technical challenges, marketing and future aspects. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2021;137. [CrossRef]

- Zeng X, Li M, Abd El-Hady D, Alshitari W, Al-Bogami AS, Lu J, et al. Commercialization of Lithium Battery Technologies for Electric Vehicles. Adv Energy Mater 2019;9. [CrossRef]

- S. Rangarajan S, Sunddararaj SP, Sudhakar AVV, Shiva CK, Subramaniam U, Collins ER, et al. Lithium-Ion Batteries—The Crux of Electric Vehicles with Opportunities and Challenges. Clean Technologies 2022;4:908–30. [CrossRef]

- Wazeer A, Das A, Abeykoon C, Sinha A, Karmakar A. Composites for electric vehicles and automotive sector: A review. Green Energy and Intelligent Transportation 2023;2. [CrossRef]

- Mata TM, Correia D, Andrade S, Casal S, Ferreira IMPLVO, Matos E, et al. Fish Oil Enzymatic Esterification for Acidity Reduction. Waste Biomass Valorization 2020;11:1131–41. [CrossRef]

- Mata TM, Smith RL, Young DM, Costa CAV. Life cycle assessment of gasoline blending options. Environ Sci Technol 2003;37:3724–32. [CrossRef]

- Robinson AL, Taub AI, Keoleian GA. Fuel efficiency drives the auto industry to reduce vehicle weight. MRS Bull 2019;44:920–2. [CrossRef]

- Zhang W, Xu J. Advanced lightweight materials for Automobiles: A review. Mater Des 2022;221. [CrossRef]

- Kothawale C, Varma P, Kandasubramanian B. Innovations in biodegradable materials: Harnessing Spirulina algae for sustainable biocomposite production. Bioresour Technol Rep 2024;28. [CrossRef]

- Krishna VS, Subashini V, Hariharan A, Chidambaram D, Raaju A, Gopichandran N, et al. Role of crosslinkers in advancing chitosan-based biocomposite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering: A comprehensive review. Int J Biol Macromol 2024;283. [CrossRef]

- Saha A, Kumar S, Zindani D, Bhowmik S. Micro-mechanical analysis of the pineapple-reinforced polymeric composite by the inclusion of pineapple leaf particulates. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part L: Journal of Materials: Design and Applications 2021;235:1112–27. [CrossRef]

- Saha A, Kumar S, Kumar A. Influence of pineapple leaf particulate on mechanical, thermal and biodegradation characteristics of pineapple leaf fiber reinforced polymer composite. Journal of Polymer Research 2021;28. [CrossRef]

- Saha A, Kulkarni ND, Kumar M, Kumari P. The structural, dielectric, and dynamic properties of NaOH-treated Bambusa tulda reinforced biocomposites—an experimental investigation. Biomass Convers Biorefin 2023. [CrossRef]

- Saha A, Kumari P. Effect of alkaline treatment on physical, structural, mechanical and thermal properties of Bambusa tulda (Northeast Indian species) based sustainable green composites. Polym Compos 2023;44:2449–73. [CrossRef]

- Saha A, Kulkarni ND, Kumari P. Development of Bambusa tulda-reinforced different biopolymer matrix green composites and MCDM-based sustainable material selection for automobile applications. Environ Dev Sustain 2023. [CrossRef]

- Saha A, Kulkarni ND, Kumari P. Development of Bambusa tulda fiber-micro particle reinforced hybrid green composite: A sustainable solution for tomorrow’s challenges in construction and building engineering. Constr Build Mater 2024;441. [CrossRef]

- Shanmugam V, Mensah RA, Försth M, Sas G, Restás Á, Addy C, et al. Circular economy in biocomposite development: State-of-the-art, challenges and emerging trends. Composites Part C: Open Access 2021;5. [CrossRef]

- McCormick K, Kautto N. The Bioeconomy in Europe: An Overview. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2013;5:2589–608. [CrossRef]

- Väisänen T, Haapala A, Lappalainen R, Tomppo L. Utilization of agricultural and forest industry waste and residues in natural fiber-polymer composites: A review. Waste Management 2016;54:62–73. [CrossRef]

- Saha, Abir, and Poonam Kumari. “Effect of alkaline treatment on physical, structural, mechanical and thermal properties of Bambusa tulda (Northeast Indian species) based sustainable green composites.” Polymer Composites 2023, 44; 4, 2449-2473. [CrossRef]

- Vijay R, Lenin Singaravelu D, Vinod A, Sanjay MR, Siengchin S, Jawaid M, et al. Characterization of raw and alkali treated new natural cellulosic fibers from Tridax procumbens. Int J Biol Macromol 2019;125:99–108. [CrossRef]

- Madhu P, Sanjay MR, Jawaid M, Siengchin S, Khan A, Pruncu CI. A new study on effect of various chemical treatments on Agave Americana fiber for composite reinforcement: Physico-chemical, thermal, mechanical and morphological properties. Polym Test 2020;85. [CrossRef]

- Madhu P, Sanjay MR, Pradeep S, Subrahmanya Bhat K, Yogesha B, Siengchin S. Characterization of cellulosic fibre from Phoenix pusilla leaves as potential reinforcement for polymeric composites. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2019;8:2597–604. [CrossRef]

- Chen L, Chen Z, Xie Z, Wei L, Hua J, Huang L, et al. Recent developments on natural fiber concrete: A review of properties, sustainability, applications, barriers, and opportunities. Developments in the Built Environment 2023;16. [CrossRef]

- Elfaleh I, Abbassi F, Habibi M, Ahmad F, Guedri M, Nasri M, et al. A comprehensive review of natural fibers and their composites: An eco-friendly alternative to conventional materials. Results in Engineering 2023;19. [CrossRef]

- Chen L, Chen Z, Xie Z, Wei L, Hua J, Huang L, et al. Recent developments on natural fiber concrete: A review of properties, sustainability, applications, barriers, and opportunities. Developments in the Built Environment 2023;16. [CrossRef]

- Saha A, Kumari P. Functional fibers from Bambusa tulda (Northeast Indian species) and their potential for reinforcing biocomposites. Mater Today Commun 2022;31. [CrossRef]

- Siqueira G, Bras J, Dufresne A. Cellulosic bionanocomposites: A review of preparation, properties and applications. Polymers (Basel) 2010;2:728–65. [CrossRef]

- Ramesh M, Palanikumar K, Reddy KH. Plant fibre based bio-composites: Sustainable and renewable green materials. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2017;79:558–84. [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni ND, Saha A, Kumari P. The development of a low-cost, sustainable bamboo-based flexible bio composite for impact sensing and mechanical energy harvesting applications. J Appl Polym Sci 2023;140. [CrossRef]

- Bourmaud A, Beaugrand J, Shah DU, Placet V, Baley C. Towards the design of high-performance plant fibre composites. Prog Mater Sci 2018;97:347–408. [CrossRef]

- Bader QA, Al-Sharify ZT, Dhabab JM, Zaidan HK, Rheima AM, Athair DM, et al. Cellulose nanomaterials in oil and gas industry and bio-manufacture: Current situation and future outlook. Case Studies in Chemical and Environmental Engineering 2024;10. [CrossRef]

- Baley C, Gomina M, Breard J, Bourmaud A, Davies P. Variability of mechanical properties of flax fibres for composite reinforcement. A review. Ind Crops Prod 2020;145. [CrossRef]

- Abolore RS, Jaiswal S, Jaiswal AK. Green and sustainable pretreatment methods for cellulose extraction from lignocellulosic biomass and its applications: A review. Carbohydrate Polymer Technologies and Applications 2024;7. [CrossRef]

- Sharma R, Nath PC, Mohanta YK, Bhunia B, Mishra B, Sharma M, et al. Recent advances in cellulose-based sustainable materials for wastewater treatment: An overview. Int J Biol Macromol 2024;256. [CrossRef]

- Azwa ZN, Yousif BF, Manalo AC, Karunasena W. A review on the degradability of polymeric composites based on natural fibres. Mater Des 2013;47:424–42. [CrossRef]

- Akil HM, Omar MF, Mazuki AAM, Safiee S, Ishak ZAM, Abu Bakar A. Kenaf fiber reinforced composites: A review. Mater Des 2011;32:4107–21. [CrossRef]

- John MJ, Francis B, Varughese KT, Thomas S. Effect of chemical modification on properties of hybrid fiber biocomposites. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf 2008;39:352–63. [CrossRef]

- Huang J, Yu C. Determination of cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin content using near-infrared spectroscopy in flax fiber. Textile Research Journal 2019;89:4875–83. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Y, Yue J, Tao L, Liu Y, Shi SQ, Cai L, et al. Effect of lignin on the self-bonding of a natural fiber material in a hydrothermal environment: Lignin structure and characterization. Int J Biol Macromol 2020;158:1135–40. [CrossRef]

- Wijaya CJ, Ismadji S, Gunawan S. A review of lignocellulosic-derived nanoparticles for drug delivery applications: Lignin nanoparticles, xylan nanoparticles, and cellulose nanocrystals. Molecules 2021;26. [CrossRef]

- Thielemans W, Wool RP. Kraft lignin as fiber treatment for natural fiber-reinforced composites. Polym Compos 2005;26:695–705. [CrossRef]

- Saha A, Kumar S, Zindani D. Investigation of the effect of water absorption on thermomechanical and viscoelastic properties of flax-hemp-reinforced hybrid composite. Polym Compos 2021;42:4497–516. [CrossRef]

- Saha A, Kumar S, Kumar A. Influence of pineapple leaf particulate on mechanical, thermal and biodegradation characteristics of pineapple leaf fiber reinforced polymer composite. Journal of Polymer Research 2021;28. [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Pérez F, Steigerwald H, Schülke S, Vieths S, Toda M, Scheurer S. The Dietary Fiber Pectin: Health Benefits and Potential for the Treatment of Allergies by Modulation of Gut Microbiota. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2021;21. [CrossRef]

- Chokshi S, Parmar V, Gohil P, Chaudhary V. Chemical Composition and Mechanical Properties of Natural Fibers. Journal of Natural Fibers 2022;19:3942–53. [CrossRef]

- Beukema M, Faas MM, de Vos P. The effects of different dietary fiber pectin structures on the gastrointestinal immune barrier: impact via gut microbiota and direct effects on immune cells. Exp Mol Med 2020;52:1364–76. [CrossRef]

- Sgriccia N, Hawley MC, Misra M. Characterization of natural fiber surfaces and natural fiber composites. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf 2008;39:1632–7. [CrossRef]

- Xiong X, Shen SZ, Hua L, Liu JZ, Li X, Wan X, et al. Finite element models of natural fibers and their composites: A review. Journal of Reinforced Plastics and Composites 2018;37:617–35. [CrossRef]

- Ye H, Zhang Y, Yu Z, Mu J. Effects of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin on the morphology and mechanical properties of metakaolin-based geopolymer. Constr Build Mater 2018;173:10–6. [CrossRef]

- Dorez G, Ferry L, Sonnier R, Taguet A, Lopez-Cuesta JM. Effect of cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin contents on pyrolysis and combustion of natural fibers. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 2014;107:323–31. [CrossRef]

- Lila MK, Komal UK, Singh Y, Singh I. Extraction and Characterization of Munja Fibers and Its Potential in the Biocomposites. Journal of Natural Fibers 2022;19:2675–93. [CrossRef]

- Saha, S, Kumar S, Mahakur K V, Sharma S, and Saha A. Development and machine learning based prediction of carbon/hemp/ramie sandwich composite as sustainable and ecofriendly solution for automobile application. Materials Today Communications, 2024, 110817, 41. [CrossRef]

- Das O, Sarmah AK, Bhattacharyya D. Nanoindentation assisted analysis of biochar added biocomposites. Compos B Eng 2016;91:219–27. [CrossRef]

- Das O, Sarmah AK, Bhattacharyya D. Nanoindentation assisted analysis of biochar added biocomposites. Compos B Eng 2016;91:219–27. [CrossRef]

- Väisänen T, Das O, Tomppo L. A review on new bio-based constituents for natural fiber-polymer composites. J Clean Prod 2017;149:582–96. [CrossRef]

- Qaiss A, Bouhfid R, Essabir H. Effect of Processing Conditions on the Mechanical and Morphological Properties of Composites Reinforced by Natural Fibres. Manufacturing of Natural Fibre Reinforced Polymer Composites, Springer International Publishing; 2015, p. 177–97. [CrossRef]

- Scott GJ. A review of root, tuber and banana crops in developing countries: past, present and future. Int J Food Sci Technol 2021;56:1093–114. [CrossRef]

- Kumara A, Kanchana K, Senerath A, Thiruchchelvan N. Use of maturity traits to identify optimal harvestable maturity of banana Musa AAB cv. “embul” in dry zone of Sri Lanka. Open Agric 2021;6:143–51. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes ERK, Marangoni C, Souza O, Sellin N. Thermochemical characterization of banana leaves as a potential energy source. Energy Convers Manag 2013;75:603–8. [CrossRef]

- Meya AI, Ndakidemi PA, Mtei KM, Swennen R, Merckx R. Optimizing soil fertility management strategies to enhance banana production in volcanic soils of the Northern Highlands, Tanzania. Agronomy 2020;10. [CrossRef]

- Maseko KH, Regnier T, Meiring B, Wokadala OC, Anyasi TA. Musa species variation, production, and the application of its processed flour: A review. Sci Hortic 2024;325. [CrossRef]

- Akatwijuka O, Gepreel MAH, Abdel-Mawgood A, Yamamoto M, Saito Y, Hassanin AH. Overview of banana cellulosic fibers: agro-biomass potential, fiber extraction, properties, and sustainable applications. Biomass Convers Biorefin 2024;14:7449–65. [CrossRef]

- Hasan KMF, Horváth PG, Bak M, Alpár T. A state-of-the-art review on coir fiber-reinforced biocomposites. RSC Adv 2021;11:10548–71. [CrossRef]

- Kumar S, Saha A. Effects of particle size on structural, physical, mechanical and tribology behaviour of agricultural waste (corncob micro/nano-filler) based epoxy biocomposites. J Mater Cycles Waste Manag 2022;24:2527–44. [CrossRef]

- Okeke FO, Ahmed A, Imam A, Hassanin H. A review of corncob-based building materials as a sustainable solution for the building and construction industry. Hybrid Advances 2024;6:100269. [CrossRef]

- Shokrollahi S, Shavandi A, Valentine Okoro O, Denayer JFM, Karimi K. Sustainable biorefinery development for valorizing all wastes from date palm agroindustry. Fuel 2024;358. [CrossRef]

- Raza M, Mustafa J, Al-Marzouqi AH, Abu-Jdayil B. Isolation and characterization of cellulose from date palm waste using rejected brine solution. International Journal of Thermofluids 2024;21. [CrossRef]

- FN A, M Y. Co-Substrating of Peanut Shells with Cornstalks Enhances Biodegradation by Pleurotus ostreatus. J Bioremediat Biodegrad 2016;07. [CrossRef]

- Sathiparan N, Anburuvel A, Selvam VV. Utilization of agro-waste groundnut shell and its derivatives in sustainable construction and building materials – A review. Journal of Building Engineering 2023;66. [CrossRef]

- Yaradoddi JS, Banapurmath NR, Ganachari S V., Soudagar MEM, Sajjan AM, Kamat S, et al. Bio-based material from fruit waste of orange peel for industrial applications. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2021. [CrossRef]

- Tsouko E, Maina S, Ladakis D, Kookos IK, Koutinas A. Integrated biorefinery development for the extraction of value-added components and bacterial cellulose production from orange peel waste streams. Renew Energy 2020;160:944–54. [CrossRef]

- Asim M, Abdan K, Jawaid M, Nasir M, Dashtizadeh Z, Ishak MR, et al. A review on pineapple leaves fibre and its composites. Int J Polym Sci 2015;2015. [CrossRef]

- Abbas A, Ansumali S. Global Potential of Rice Husk as a Renewable Feedstock for Ethanol Biofuel Production. Bioenergy Res 2010;3:328–34. [CrossRef]

- Wu G, Qu P, Sun E, Chang Z, Xu Y, Huang H. Composted rice husk properties. vol. 10. 2015.

- Mubarak AA, Ilyas RA, Nordin AH, Ngadi N, Alkbir MFM. Recent developments in sugarcane bagasse fibre-based adsorbent and their potential industrial applications: A review. Int J Biol Macromol 2024;277. [CrossRef]

- Qasim U, Ali Z, Nazir MS, Ul Hassan S, Rafiq S, Jamil F, et al. Isolation of Cellulose from Wheat Straw Using Alkaline Hydrogen Peroxide and Acidified Sodium Chlorite Treatments: Comparison of Yield and Properties. Advances in Polymer Technology 2020;2020. [CrossRef]

- Alejandro Ortiz-Ulloa J, Fernanda Abril-González M, Raúl Pelaez-Samaniego M, Silvana Zalamea-Piedra T. Biomass yield and carbon abatement potential of banana crops (Musa spp.) in Ecuador n.d. [CrossRef]

- Preparation of Cellulose Nanocrystals Bio-Polymer From Agro-Industrial Wastes: Separation and Characterization. n.d.

- Pitchayya Pillai G, Manimaran P, Vignesh V. Physico-chemical and Mechanical Properties of Alkali-Treated Red Banana Peduncle Fiber. Journal of Natural Fibers 2021;18:2102–11. [CrossRef]

- Manimaran P, Pillai GP, Vignesh V, Prithiviraj M. Characterization of natural cellulosic fibers from Nendran Banana Peduncle plants. Int J Biol Macromol 2020;162:1807–15. [CrossRef]

- Manimaran P, Sanjay MR, Senthamaraikannan P, Jawaid M, Saravanakumar SS, George R. Synthesis and characterization of cellulosic fiber from red banana peduncle as reinforcement for potential applications. Journal of Natural Fibers 2019;16:768–80. [CrossRef]

- Manimaran P, Jeyasekaran AS, Purohit R, Pitchayya Pillai G. An Experimental and Numerical Investigation on the Mechanical Properties of Addition of Wood Flour Fillers in Red Banana Peduncle Fiber Reinforced Polyester Composites. Journal of Natural Fibers 2020;17:1140–58. [CrossRef]

- Bar M, Belay H, Alagirusamy R, Das A, Ouagne P. Refining of Banana Fiber for Load Bearing Application through Emulsion Treatment and Its Comparison with Other Traditional Methods. Journal of Natural Fibers 2022;19:5956–73. [CrossRef]

- Jayaprabha JS, Brahmakumar M, Manilal VB. Banana pseudostem characterization and its fiber property evaluation on physical and bioextraction. Journal of Natural Fibers 2011;8:149–60. [CrossRef]

- Mumthas ACSI, Wickramasinghe GLD, Gunasekera USW. Effect of physical, chemical and biological extraction methods on the physical behaviour of banana pseudo-stem fibres: Based on fibres extracted from five common Sri Lankan cultivars. J Eng Fiber Fabr 2019;14. [CrossRef]

- Jose S, Mishra L, Basu G, Kumar Samanta A. Study on Reuse of Coconut Fiber Chemical Retting Bath. Part II---Recovery and Characterization of Lignin. Journal of Natural Fibers 2017;14:510–8. [CrossRef]

- Saha A, Kumar S. Effects of graphene nanoparticles with organic wood particles: A synergistic effect on the structural, physical, thermal, and mechanical behavior of hybrid composites. Polym Adv Technol 2022;33:3201–15. [CrossRef]

- Kumar S, Saha A. Graphene nanoplatelets/organic wood dust hybrid composites: physical, mechanical and thermal characterization. Iranian Polymer Journal (English Edition) 2021;30:935–51. [CrossRef]

- Kohli P, Gupta R. Application of calcium alginate immobilized and crude pectin lyase from Bacillus cereus in degumming of plant fibres. Biocatal Biotransformation 2019;37:341–8. [CrossRef]

- Chen S, Zhang X, Singh D, Yu H, Yang X. Biological pretreatment of lignocellulosics: Potential, progress and challenges. Biofuels 2010;1:177–99. [CrossRef]

- Awedem Wobiwo F, Alleluya VK, Emaga TH, Boda M, Fokou E, Gillet S, et al. Recovery of fibers and biomethane from banana peduncles biomass through anaerobic digestion. Energy for Sustainable Development 2017;37:60–5. [CrossRef]

- Balda S, Sharma A, Capalash N, Sharma P. Banana fibre: a natural and sustainable bioresource for eco-friendly applications. Clean Technol Environ Policy 2021;23:1389–401. [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan S, Wickramasinghe GLD, Wijayapala US. Investigation on improving banana fiber fineness for textile application. Textile Research Journal 2019;89:4398–409. [CrossRef]

- Karuppuchamy A, K. R, R. S. Novel banana core stem fiber from agricultural biomass for lightweight textile applications. Ind Crops Prod 2024;209. [CrossRef]

- Amutha K, Sudha A, Saravanan D. Characterization of Natural Fibers Extracted from Banana Inflorescence Bracts. Journal of Natural Fibers 2022;19:872–81. [CrossRef]

- Sango T, Cheumani Yona AM, Duchatel L, Marin A, Kor Ndikontar M, Joly N, et al. Step–wise multi–scale deconstruction of banana pseudo–stem (Musa acuminata) biomass and morpho–mechanical characterization of extracted long fibres for sustainable applications. Ind Crops Prod 2018;122:657–68. [CrossRef]

- Ronald Aseer J, Sankaranarayanasamy K, Jayabalan P, Natarajan R, Priya Dasan K. Morphological, Physical, and Thermal Properties of Chemically Treated Banana Fiber. Journal of Natural Fibers 2013;10:365–80. [CrossRef]

- Pickering KL, Efendy MGA, Le TM. A review of recent developments in natural fibre composites and their mechanical performance. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf 2016;83:98–112. [CrossRef]

- Neher B, Hossain R, Fatima K, Gafur MA, Hossain MdA, Ahmed F. Study of the Physical, Mechanical and Thermal Properties of Banana Fiber Reinforced HDPE Composites. Materials Sciences and Applications 2020;11:245–62. [CrossRef]

- Satapathy S, Kothapalli RVS. Mechanical, Dynamic Mechanical and Thermal Properties of Banana Fiber/Recycled High Density Polyethylene Biocomposites Filled with Flyash Cenospheres. J Polym Environ 2018;26:200–13. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh R, Ramakrishna A, Reena G, Ravindra A, Verma A. Water Absorption Kinetics and Mechanical Properties of Ultrasonic Treated Banana Fiber Reinforced-vinyl Ester Composites. Procedia Materials Science 2014;5:311–5. [CrossRef]

- Prasad N, Agarwal VK, Sinha S. Banana fiber reinforced low-density polyethylene composites: effect of chemical treatment and compatibilizer addition. Iranian Polymer Journal (English Edition) 2016;25:229–41. [CrossRef]

- Das H, Saikia P, Kalita D. Physico-mechanical properties of banana fiber reinforced polymer composite as an alternative building material. Key Eng Mater 2015;650:131–8. [CrossRef]

- Gowda S KB. Investigation of Water Absorption and Fire Resistance of Untreated Banana Fibre Reinforced Polyester Composites. vol. 4. 2017.

- Amir N, Abidin KAZ, Shiri FBM. Effects of Fibre Configuration on Mechanical Properties of Banana Fibre/PP/MAPP Natural Fibre Reinforced Polymer Composite. Procedia Eng, vol. 184, Elsevier Ltd; 2017, p. 573–80. [CrossRef]

- Laxshaman Rao B, Makode Y, Tiwari A, Dubey O, Sharma S, Mishra V. Review on properties of banana fiber reinforced polymer composites. Mater Today Proc, vol. 47, Elsevier Ltd; 2021, p. 2825–9. [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekar M, Siva I, Kumar TSM, Senthilkumar K, Siengchin S, Rajini N. Influence of Fibre Inter-ply Orientation on the Mechanical and Free Vibration Properties of Banana Fibre Reinforced Polyester Composite Laminates. J Polym Environ 2020;28:2789–800. [CrossRef]

- Pujari S, Srikiran S, Subramonian S. Recent Advances in Material Sciences. n.d.

- Moshi AAM, Madasamy S, Bharathi SRS, Periyanayaganathan P, Prabaharan A. Investigation on the mechanical properties of sisal - Banana hybridized natural fiber composites with distinct weight fractions. AIP Conf Proc, vol. 2128, American Institute of Physics Inc.; 2019. [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan T, Suresh G, Santhoshpriya K, Chidambaram CT, Vijayakumar KR, Munaf AA. Experimental analysis on mechanical properties of banana fibre/epoxy (particulate) reinforced composite. Mater Today Proc, vol. 45, Elsevier Ltd; 2021, p. 1285–9. [CrossRef]

- Vishnu Vardhini KJ, Murugan R, Surjit R. Effect of alkali and enzymatic treatments of banana fibre on properties of banana/polypropylene composites. Journal of Industrial Textiles 2018;47:1849–64. [CrossRef]

- Mohan TP, Kanny K. Compressive characteristics of unmodified and nanoclay treated banana fiber reinforced epoxy composite cylinders. Compos B Eng 2019;169:118–25. [CrossRef]

- Chavali PJ, Taru GB. Effect of Fiber Orientation on Mechanical and Tribological Properties of Banana-Reinforced Composites. Journal of Failure Analysis and Prevention 2021;21:1–8. [CrossRef]

- Laxshaman Rao B, Makode Y, Tiwari A, Dubey O, Sharma S, Mishra V. Review on properties of banana fiber reinforced polymer composites. Mater Today Proc, vol. 47, Elsevier Ltd; 2021, p. 2825–9. [CrossRef]

- Ranakoti L, Gangil B, Rajesh PK, Singh T, Sharma S, Li C, et al. Effect of surface treatment and fiber loading on the physical, mechanical, sliding wear, and morphological characteristics of tasar silk fiber waste-epoxy composites for multifaceted biomedical and engineering applications: fabrication and characterizations. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2022;19:2863–76. [CrossRef]

- Shivamurthy B, Thimmappa BHS, Monteiro J. Sliding wear, mechanical, flammability, and water intake properties of banana short fiber/Al(OH)3/epoxy composites. Journal of Natural Fibers 2020;17:337–45. [CrossRef]

- Pu Y, Ma F, Zhang J, Yang M. Optimal Lightweight Material Selection for Automobile Applications Considering Multi-Perspective Indices. IEEE Access 2018;6:8591–8. [CrossRef]

- Kumar S, Saha A. Utilization of coconut shell biomass residue to develop sustainable biocomposites and characterize the physical, mechanical, thermal, and water absorption properties. Biomass Convers Biorefin 2024;14:12815–31. [CrossRef]

- Kumaran P, Mohanamurugan S, Madhu S, Vijay R, Lenin Singaravelu D, Vinod A, et al. Investigation on thermo-mechanical characteristics of treated/untreated Portunus sanguinolentus shell powder-based jute fabrics reinforced epoxy composites. Journal of Industrial Textiles 2020;50:427–59. [CrossRef]

- Udaya Kumar PA, Ramalingaiah, Suresha B, Rajini N, Satyanarayana KG. Effect of treated coir fiber/coconut shell powder and aramid fiber on mechanical properties of vinyl ester. Polym Compos 2018;39:4542–50. [CrossRef]

- Vishnudas S, Savenije HHG, Van Der Zaag P, Anil KR, Balan K. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences The protective and attractive covering of a vegetated embankment using coir geotextiles. vol. 10. 2006.

- Abraham E, Deepa B, Pothen LA, Cintil J, Thomas S, John MJ, et al. Environmental friendly method for the extraction of coir fibre and isolation of nanofibre. Carbohydr Polym 2013;92:1477–83. [CrossRef]

- Basu G, Mishra L, Jose S, Samanta AK. Accelerated retting cum softening of coconut fibre. Ind Crops Prod 2015;77:66–73. [CrossRef]

- Manilal VB, Ajayan MS, Sreelekshmi S V. Characterization of surface-treated coir fiber obtained from environmental friendly bioextraction. Journal of Natural Fibers 2010;7:324–33. [CrossRef]

- Prashant Y, Gopinath C, Ravichandran V. DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT OF COCONUT FIBER EXTRACTION MACHINE. vol. 64. 2014.

- Bettini SHP, Bicudo ABLC, Augusto IS, Antunes LA, Morassi PL, Condotta R, et al. Investigation on the use of coir fiber as alternative reinforcement in polypropylene. J Appl Polym Sci 2010;118:2841–8. [CrossRef]

- Saw SK, Sarkhel G, Choudhury A. Surface modification of coir fibre involving oxidation of lignins followed by reaction with furfuryl alcohol: Characterization and stability. Appl Surf Sci 2011;257:3763–9. [CrossRef]

- Jayavani S, Deka H, Varghese TO, Nayak SK. Recent development and future trends in coir fiber-reinforced green polymer composites: Review and evaluation. Polym Compos 2016;37:3296–309. [CrossRef]

- Chollakup R, Smitthipong W, Kongtud W, Tantatherdtam R. Polyethylene green composites reinforced with cellulose fibers (coir and palm fibers): Effect of fiber surface treatment and fiber content. J Adhes Sci Technol, vol. 27, 2013, p. 1290–300. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Fonseca AA, Arellano M, Rodrigue D, González-Núñez R, Robledo-Ortíz JR. Effect of coupling agent content and water absorption on the mechanical properties of coir-agave fibers reinforced polyethylene hybrid composites. Polym Compos 2016;37:3015–24. [CrossRef]

- Haque M, Rahman R, Islam N, Huque M, Hasan M. Mechanical properties of polypropylene composites reinforced with chemically treated coir and abaca fiber. Journal of Reinforced Plastics and Composites 2010;29:2253–61. [CrossRef]

- Arrakhiz FZ, El Achaby M, Kakou AC, Vaudreuil S, Benmoussa K, Bouhfid R, et al. Mechanical properties of high density polyethylene reinforced with chemically modified coir fibers: Impact of chemical treatments. Mater Des 2012;37:379–83. [CrossRef]

- Essabir H, Bensalah MO, Rodrigue D, Bouhfid R, Qaiss A. Structural, mechanical and thermal properties of bio-based hybrid composites from waste coir residues: Fibers and shell particles. Mechanics of Materials 2016;93:134–44. [CrossRef]

- Morandim-Giannetti AA, Agnelli JAM, Lanças BZ, Magnabosco R, Casarin SA, Bettini SHP. Lignin as additive in polypropylene/coir composites: Thermal, mechanical and morphological properties. Carbohydr Polym 2012;87:2563–8. [CrossRef]

- Arrakhiz FZ, El Achaby M, Malha M, Bensalah MO, Fassi-Fehri O, Bouhfid R, et al. Mechanical and thermal properties of natural fibers reinforced polymer composites: Doum/low density polyethylene. Mater Des 2013;43:200–5. [CrossRef]

- Arrakhiz FZ, Malha M, Bouhfid R, Benmoussa K, Qaiss A. Tensile, flexural and torsional properties of chemically treated alfa, coir and bagasse reinforced polypropylene. Compos B Eng 2013;47:35–41. [CrossRef]

- Siakeng R, Jawaid M, Ariffin H, Salit MS. Effects of Surface Treatments on Tensile, Thermal and Fibre-matrix Bond Strength of Coir and Pineapple Leaf Fibres with Poly Lactic Acid. J Bionic Eng 2018;15:1035–46. [CrossRef]

- Dong Y, Ghataura A, Takagi H, Haroosh HJ, Nakagaito AN, Lau KT. Polylactic acid (PLA) biocomposites reinforced with coir fibres: Evaluation of mechanical performance and multifunctional properties. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf 2014;63:76–84. [CrossRef]

- Yan L, Chouw N, Huang L, Kasal B. Effect of alkali treatment on microstructure and mechanical properties of coir fibres, coir fibre reinforced-polymer composites and reinforced-cementitious composites. Constr Build Mater 2016;112:168–82. [CrossRef]

- Rout J, Tripathy SS, Nayak SK, Misra M, Mohanty AK. Scanning electron microscopy study of chemically modified coir fibers. J Appl Polym Sci 2001;79:1169–77. [CrossRef]

- Azaman MD, Sapuan SM, Sulaiman S, Zainudin ES, Khalina A. Processability of wood fibre-filled thermoplastic composite thin-walled parts using injection moulding. Manufacturing of Natural Fibre Reinforced Polymer Composites, Springer International Publishing; 2015, p. 351–67. [CrossRef]

- Verma D. The Manufacturing of Natural Fibre-Reinforced Composites by Resin-Transfer Molding Process. Manufacturing of Natural Fibre Reinforced Polymer Composites, Springer International Publishing; 2015, p. 267–90. [CrossRef]

- Saba N, Paridah MT, Jawaid M, Abdan K, Ibrahim NA. Manufacturing and Processing of Kenaf Fibre-Reinforced Epoxy Composites via Different Methods. Manufacturing of Natural Fibre Reinforced Polymer Composites, Springer International Publishing; 2015, p. 101–24. [CrossRef]

- Ketabchi MR, Hoque ME, Khalid Siddiqui M. Critical Concerns on Manufacturing Processes of Natural Fibre Reinforced Polymer Composites. Manufacturing of Natural Fibre Reinforced Polymer Composites, Springer International Publishing; 2015, p. 125–38. [CrossRef]

- Julkapli NM, Bagheri S, Sapuan SM. Bio-nanocomposites from natural fibre derivatives: Manufacturing and properties. Manufacturing of Natural Fibre Reinforced Polymer Composites, Springer International Publishing; 2015, p. 233–64. [CrossRef]

- Narendar R, Priya Dasan K, Nair M. Development of coir pith/nylon fabric/epoxy hybrid composites: Mechanical and ageing studies. Mater Des 2014;54:644–51. [CrossRef]

- Haque MM, Hasan M, Islam MS, Ali ME. Physico-mechanical properties of chemically treated palm and coir fiber reinforced polypropylene composites. Bioresour Technol 2009;100:4903–6. [CrossRef]

- Watt E, Abdelwahab MA, Mohanty AK, Misra M. Biocomposites from biobased polyamide 4,10 and waste corn cob based biocarbon. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf 2021;145. [CrossRef]

- Mohanty AK, Vivekanandhan S, Pin J-M, Misra M. Composites from renewable and sustainable resources: Challenges and innovations. n.d.

- Ikram S, Das O, Bhattacharyya D. A parametric study of mechanical and flammability properties of biochar reinforced polypropylene composites. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf 2016;91:177–88. [CrossRef]

- Naik TP, Singh I, Sharma AK. Processing of polymer matrix composites using microwave energy: A review. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf 2022;156. [CrossRef]

- Brinchi L, Cotana F, Fortunati E, Kenny JM. Production of nanocrystalline cellulose from lignocellulosic biomass: Technology and applications. Carbohydr Polym 2013;94:154–69. [CrossRef]

- Chun KS, Husseinsyah S. Polylactic acid/corn cob eco-composites: Effect of new organic coupling agent. Journal of Thermoplastic Composite Materials 2014;27:1667–78. [CrossRef]

- Guan J, Hanna MA. Functional properties of extruded foam composites of starch acetate and corn cob fiber. Ind Crops Prod 2004;19:255–69. [CrossRef]

- Gandam PK, Chinta ML, Pabbathi NPP, Velidandi A, Sharma M, Kuhad RC, et al. Corncob-based biorefinery: A comprehensive review of pretreatment methodologies, and biorefinery platforms. Journal of the Energy Institute 2022;101:290–308. [CrossRef]

- Kumar S, Saha A. Effects of particle size on structural, physical, mechanical and tribology behaviour of agricultural waste (corncob micro/nano-filler) based epoxy biocomposites. J Mater Cycles Waste Manag 2022;24:2527–44. [CrossRef]

- Jiang F, Hsieh Y Lo. Cellulose nanocrystal isolation from tomato peels and assembled nanofibers. Carbohydr Polym 2015;122:60–8. [CrossRef]

- Alemdar A, Sain M. Isolation and characterization of nanofibers from agricultural residues - Wheat straw and soy hulls. Bioresour Technol 2008;99:1664–71. [CrossRef]

- Chen YW, Lee HV, Juan JC, Phang SM. Production of new cellulose nanomaterial from red algae marine biomass Gelidium elegans. Carbohydr Polym 2016;151:1210–9. [CrossRef]

- El Halal SLM, Colussi R, Deon VG, Pinto VZ, Villanova FA, Carreño NLV, et al. Films based on oxidized starch and cellulose from barley. Carbohydr Polym 2015;133:644–53. [CrossRef]

- Pelissari FM, Andrade-Mahecha MM, Sobral PJ do A, Menegalli FC. Nanocomposites based on banana starch reinforced with cellulose nanofibers isolated from banana peels. J Colloid Interface Sci 2017;505:154–67. [CrossRef]

- Lenhani GC, dos Santos DF, Koester DL, Biduski B, Deon VG, Machado Junior M, et al. Application of Corn Fibers from Harvest Residues in Biocomposite Films. J Polym Environ 2021;29:2813–24. [CrossRef]

- Gandam PK, Chinta ML, Pabbathi NPP, Velidandi A, Sharma M, Kuhad RC, et al. Corncob-based biorefinery: A comprehensive review of pretreatment methodologies, and biorefinery platforms. Journal of the Energy Institute 2022;101:290–308. [CrossRef]

- Yeng CM, Husseinsyah S, Ting SS. Modified Corn Cob Filled Chitosan Biocomposite Films. Polymer - Plastics Technology and Engineering 2013;52:1496–502. [CrossRef]

- Fuqua MA, Chevali VS, Ulven CA. Lignocellulosic byproducts as filler in polypropylene: Comprehensive study on the effects of compatibilization and loading. J Appl Polym Sci 2013;127:862–8. [CrossRef]

- Silvério HA, Flauzino Neto WP, Dantas NO, Pasquini D. Extraction and characterization of cellulose nanocrystals from corncob for application as reinforcing agent in nanocomposites. Ind Crops Prod 2013;44:427–36. [CrossRef]

- Tioua T, Kriker A, Barluenga G, Palomar I. Influence of date palm fiber and shrinkage reducing admixture on self-compacting concrete performance at early age in hot-dry environment. Constr Build Mater 2017;154:721–33. [CrossRef]

- Shalwan A, Yousif BF. Influence of date palm fibre and graphite filler on mechanical and wear characteristics of epoxy composites. Mater Des 2014;59:264–73. [CrossRef]

- Elbadry EA. Agro-Residues: Surface Treatment and Characterization of Date Palm Tree Fiber as Composite Reinforcement. J Compos 2014;2014:1–8. [CrossRef]

- Al-Oqla FM, Sapuan SM. Natural fiber reinforced polymer composites in industrial applications: Feasibility of date palm fibers for sustainable automotive industry. J Clean Prod 2014;66:347–54. [CrossRef]

- Benallel A, Tilioua A, Garoum M. Development of thermal insulation panels bio-composite containing cardboard and date palm fibers. J Clean Prod 2024;434. [CrossRef]

- Chkala H, Kirm I, Ighir S, Ourmiche A, Chigr M, El Mansouri NE. Preparation and characterization of eco-friendly composite based on geopolymer and reinforced with date palm fiber. Arabian Journal of Chemistry 2024;17. [CrossRef]

- El-Shekeil YA, AL-Oqla FM, Refaey HA, Bendoukha S, Barhoumi N. Investigating the mechanical performance and characteristics of nitrile butadiene rubber date palm fiber reinforced composites for sustainable bio-based materials. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2024;29:101–8. [CrossRef]

- Saada K, Zaoui M, Amroune S, Benyettou R, Hechaichi A, Jawaid M, et al. Exploring tensile properties of bio composites reinforced date palm fibers using experimental and Modelling Approaches. Mater Chem Phys 2024;314. [CrossRef]

- Elhadi A, Amroune S, Slamani M, Arslane M, Jawaid M. Assessment and analysis of drilling-induced damage in jute/palm date fiber-reinforced polyester hybrid composite. Biomass Convers Biorefin 2024. [CrossRef]

- Chkala H, Kirm I, Ighir S, Ourmiche A, Chigr M, El Mansouri NE. Preparation and characterization of eco-friendly composite based on geopolymer and reinforced with date palm fiber. Arabian Journal of Chemistry 2024;17. [CrossRef]

- Mahomoodally MF, Khadaroo SK, Hosenally M, Zengin G, Rebezov M, Ali Shariati M, et al. Nutritional, medicinal and functional properties of different parts of the date palm and its fruit (Phoenix dactylifera L.)–A systematic review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2024;64:7748–803. [CrossRef]

- Rajeshkumar G, Hariharan V, Devnani GL, Prakash Maran J, Sanjay MR, Siengchin S, et al. Cellulose fiber from date palm petioles as potential reinforcement for polymer composites: Physicochemical and structural properties. Polym Compos 2021;42:3943–53. [CrossRef]

- Hachaichi A, Kouini B, Kian LK, Asim M, Jawaid M. Extraction and Characterization of Microcrystalline Cellulose from Date Palm Fibers using Successive Chemical Treatments. J Polym Environ 2021;29:1990–9. [CrossRef]

- Hassan R, Alluqmani AE, Badawi AK. An eco-friendly solution for greywater treatment via date palm fiber filter. Desalination Water Treat 2024;317. [CrossRef]

- Faiad A, Alsmari M, Ahmed MMZ, Bouazizi ML, Alzahrani B, Alrobei H. Date Palm Tree Waste Recycling: Treatment and Processing for Potential Engineering Applications. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2022;14. [CrossRef]

- Fenta EW, Tsegaw AA. Study the effects of fiber loading and orientation on the tensile properties of date palm fiber-reinforced polyester composite. Polymer Bulletin 2024;81:1549–62. [CrossRef]

- AL-Oqla FM, Hayajneh MT, Al-Shrida MM. Mechanical performance, thermal stability and morphological analysis of date palm fiber reinforced polypropylene composites toward functional bio-products. Cellulose 2022;29:3293–309. [CrossRef]

- Bezazi A, Boumediri H, Garcia del Pino G, Bezzazi B, Scarpa F, Reis PNB, et al. Alkali Treatment Effect on Physicochemical and Tensile Properties of Date Palm Rachis Fibers. Journal of Natural Fibers 2022;19:3770–87. [CrossRef]

- Priyadharshini GS, Velmurugan T, Suyambulingam I, Sanjay MR, Siengchin S, Vishnu R. Characterization of cellulosic plant fiber extracted from Waltheria indica Linn. stem. Biomass Convers Biorefin 2024;14:20773–86. [CrossRef]

- AL-Oqla FM, Hayajneh MT, Al-Shrida MM. Mechanical performance, thermal stability and morphological analysis of date palm fiber reinforced polypropylene composites toward functional bio-products. Cellulose 2022;29:3293–309. [CrossRef]

- Al-Hasni M, Waly M, Al-Habsi N, Al-Khalili M, Rahman MS. Functional Characterization of Alkaline Digested Date-Pits: Residue and Supernatant Fibers. Waste Biomass Valorization 2023;14:1057–68. [CrossRef]

- Al-Mamari A, Al-Habsi N, Al-Khalili M, Rahman MS. Extraction and characterization of residue fibers from defatted date-pits after alkaline-acid digestion: effects of different pretreatments. J Therm Anal Calorim 2022;147:9405–16. [CrossRef]

- Khlif M, Chaari R, Bradai C. Physico-mechanical characterization of poly (butylene succinate) and date palm fiber-based biodegradable composites. Polymers and Polymer Composites 2022;30. [CrossRef]

- Subhash AJ, Bamigbade GB, Ayyash M. Current insights into date by-product valorization for sustainable food industries and technology. Sustainable Food Technology 2024;2:331–61. [CrossRef]

- Dhakal HN, Khan SH, Alnaser IA, Karim MR, Saifullah A, Zhang Z. Potential of Date Palm Fibers (DPFs) as a Sustainable Reinforcement for Bio- Composites and its Property Enhancement for Key Applications: A Review. Macromol Mater Eng 2024. [CrossRef]

- Awad S, Hamouda T, Midani M, Zhou Y, Katsou E, Fan M. Date palm fibre geometry and its effect on the physical and mechanical properties of recycled polyvinyl chloride composite. Ind Crops Prod 2021;174. [CrossRef]

- Khoudja D, Taallah B, Izemmouren O, Aggoun S, Herihiri O, Guettala A. Mechanical and thermophysical properties of raw earth bricks incorporating date palm waste. Constr Build Mater 2021;270. [CrossRef]

- Alshammari BA, Saba N, Alotaibi MD, Alotibi MF, Jawaid M, Alothman OY. Evaluation of mechanical, physical, and morphological properties of epoxy composites reinforced with different date palm fillers. Materials 2019;12. [CrossRef]

- Sair S, Oushabi A, Kammouni A, Tanane O, Abboud Y, Oudrhiri Hassani F, et al. Effect of surface modification on morphological, mechanical and thermal conductivity of hemp fiber: Characterization of the interface of hemp -Polyurethane composite. Case Studies in Thermal Engineering 2017;10:550–9. [CrossRef]

- Sethupathi M, Khumalo MV, Skosana SJ, Muniyasamy S. Recent Developments of Pineapple Leaf Fiber (PALF) Utilization in the Polymer Composites—A Review. Separations 2024;11. [CrossRef]

- Akter M, Uddin MH, Anik HR. Plant fiber-reinforced polymer composites: a review on modification, fabrication, properties, and applications. Polymer Bulletin 2024;81:1–85. [CrossRef]

- Todkar SS, Patil SA. Review on mechanical properties evaluation of pineapple leaf fibre (PALF) reinforced polymer composites. Compos B Eng 2019;174. [CrossRef]

- Jose S, Salim R, Ammayappan L. An Overview on Production, Properties, and Value Addition of Pineapple Leaf Fibers (PALF). Journal of Natural Fibers 2016;13:362–73. [CrossRef]

- Sethy DP, Sahoo S. A comprehensive review on different leaf fiber loading on PLA polymer matrix composite. Journal of Thermoplastic Composite Materials 2024. [CrossRef]

- Asim M, Abdan K, Jawaid M, Nasir M, Dashtizadeh Z, Ishak MR, et al. A review on pineapple leaves fibre and its composites. Int J Polym Sci 2015;2015. [CrossRef]

- Jain J, Sinha S. Pineapple Leaf Fiber Polymer Composites as a Promising Tool for Sustainable, Eco-friendly Composite Material: Review. Journal of Natural Fibers 2022;19:10031–52. [CrossRef]

- Jose S, Salim R, Ammayappan L. An Overview on Production, Properties, and Value Addition of Pineapple Leaf Fibers (PALF). Journal of Natural Fibers 2016;13:362–73. [CrossRef]

- Mishra S, Misra M, Tripathy SS, Nayak SK, Mohanty AK. Potentiality of pineapple leaf fibre as reinforcement in PALF-polyester composite: Surface modification and mechanical performance. Journal of Reinforced Plastics and Composites 2001;20:321–34. [CrossRef]

- Jain J, Sinha S. Pineapple Leaf Fiber Polymer Composites as a Promising Tool for Sustainable, Eco-friendly Composite Material: Review. Journal of Natural Fibers 2022;19:10031–52. [CrossRef]

- Santulli C, Palanisamy S, Kalimuthu M. Pineapple fibers, their composites and applications. Plant Fibers, their Composites, and Applications, Elsevier; 2022, p. 323–46. [CrossRef]

- Mishra S, Mohanty AK, Drzal LT, Misra M, Hinrichsen G. A review on pineapple leaf fibers, sisal fibers and their biocomposites. Macromol Mater Eng 2004;289:955–74. [CrossRef]

- Ng LF, Yahya MY, Leong HY, Parameswaranpillai J, Dzulkifli MH. Evaluation of physical and mechanical properties of pineapple leaf and kenaf fabrics as potential reinforcement in bio-composites. Biomass Convers Biorefin 2023. [CrossRef]

- Hadi AE, Siregar JP, Cionita T, Norlaila MB, Badari MAM, Irawan AP, et al. Potentiality of Utilizing Woven Pineapple Leaf Fibre for Polymer Composites. Polymers (Basel) 2022;14. [CrossRef]

- Shih YF, Ou TY, Chen ZT, Chang CW, Lau EM. Curing kinetics study of chemically modified pineapple leaf fiber/epoxy composite. Polymers from Renewable Resources 2024;15:90–106. [CrossRef]

- Nassar MMA, Alzebdeh KI, Al-Hinai N, Safy M Al. Enhancing mechanical performance of polypropylene bio-based composites using chemically treated date palm filler. Ind Crops Prod 2024;220. [CrossRef]

- Gunasekhar B, Rajendran S. A comparative study on impact strength of pineapple (Ananas comosus) fiber vinyl ester based on hybrid composite with and without rice husk filler particle. Interactions 2024;245. [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan V;, Subbarayan, Sathiyamurthy. Studies on Mechanical, Morphological, and Water Absorption Properties of Agro Residues Reinforced Polyester Hybrid Composites. vol. 43. 2024.

- Rahman H, Yeasmin F, Khan SA, Hasan MZ, Roy M, Uddin MB, et al. Fabrication and analysis of physico-mechanical characteristics of NaOH treated PALF reinforced LDPE composites: Effect of gamma irradiation. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 2021;11:914–28. [CrossRef]

- Rahman H, Alimuzzaman S, Sayeed MMA, Khan RA. Effect of gamma radiation on mechanical properties of pineapple leaf fiber (PALF)-reinforced low-density polyethylene (LDPE) composites. International Journal of Plastics Technology 2019;23:229–38. [CrossRef]

- Vinoth V, Sathiyamurthy S, Ananthi N, Jayabal S. Mechanical characterization and study on morphological properties: Natural and agro waste utilization of reinforced polyester hybrid composites. Proc Inst Mech Eng C J Mech Eng Sci 2024. [CrossRef]

- Mubarak AA, Ilyas RA, Nordin AH, Ngadi N, Alkbir MFM. Recent developments in sugarcane bagasse fibre-based adsorbent and their potential industrial applications: A review. Int J Biol Macromol 2024;277. [CrossRef]

- Hiranobe CT, Gomes AS, Paiva FFG, Tolosa GR, Paim LL, Dognani G, et al. Sugarcane Bagasse: Challenges and Opportunities for Waste Recycling. Clean Technologies 2024;6:662–99. [CrossRef]

- Chougala V, Gowda AC, Nagaraja S, Ammarullah MI. Effect of Chemical Treatments on Mechanical Properties of Sugarcane Bagasse (Gramineae Saccharum Officinarum L) Fiber Based Biocomposites: A Review. Journal of Natural Fibers 2025;22. [CrossRef]

- Theodore T, Mozer C, Joseph P, Njie J, Clins N, Parfait ZE, et al. Extraction and Characterization of Bagasse Fibres from Sugar Cane (<i>Saccharum officinarum</i>) for Incorporation into a Mortar. Open Journal of Applied Sciences 2020;10:521–33. [CrossRef]

- Antunes F, Mota IF, da Silva Burgal J, Pintado M, Costa PS. A review on the valorization of lignin from sugarcane by-products: From extraction to application. Biomass Bioenergy 2022;166. [CrossRef]

- Valizadeh Kiamahalleh M, Gholampour A, Ngo TD, Ozbakkaloglu T. Mechanical, durability and microstructural properties of waste-based concrete reinforced with sugarcane fiber. Structures 2024;67. [CrossRef]

- Mubarak AA, Ilyas RA, Nordin AH, Ngadi N, Alkbir MFM. Recent developments in sugarcane bagasse fibre-based adsorbent and their potential industrial applications: A review. Int J Biol Macromol 2024;277. [CrossRef]

- Zafeer MK, Menezes RA, Venkatachalam H, Bhat KS. Sugarcane bagasse-based biochar and its potential applications: a review. Emergent Mater 2024;7:133–61. [CrossRef]

- Sharma P, Sharma S, Sharma SK, Jain A, Shrivastava K. Review on recent advancement of adsorption potential of sugarcane bagasse biochar in wastewater treatment. Chemical Engineering Research and Design 2024;206:428–39. [CrossRef]

- Mehrzad S, Taban E, Soltani P, Samaei SE, Khavanin A. Sugarcane bagasse waste fibers as novel thermal insulation and sound-absorbing materials for application in sustainable buildings. Build Environ 2022;211. [CrossRef]

- Zafeer MK, Prabhu R, Rao S, Mahesha GT, Bhat KS. Mechanical Characteristics of Sugarcane Bagasse Fibre Reinforced Polymer Composites: A Review. Cogent Eng 2023;10. [CrossRef]

- Prabhath N, Kumara BS, Vithanage V, Samarathunga AI, Sewwandi N, Maduwantha K, et al. A Review on the Optimization of the Mechanical Properties of Sugarcane-Bagasse-Ash-Integrated Concretes. Journal of Composites Science 2022;6. [CrossRef]

- Madhu S, Devarajan Y, Natrayan L. Effective utilization of waste sugarcane bagasse filler-reinforced glass fibre epoxy composites on its mechanical properties - waste to sustainable production. Biomass Convers Biorefin 2023;13:15111–8. [CrossRef]

- Shabbirahmed AM, Haldar D, Dey P, Patel AK, Singhania RR, Dong C Di, et al. Sugarcane bagasse into value-added products: a review. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2022;29:62785–806. [CrossRef]

- Kusuma HS, Permatasari D, Umar WK, Sharma SK. Sugarcane bagasse as an environmentally friendly composite material to face the sustainable development era. Biomass Convers Biorefin 2023. [CrossRef]

- Chandgude S, Salunkhe S. In state of art: Mechanical behavior of natural fiber-based hybrid polymeric composites for application of automobile components. Polym Compos 2021;42:2678–703. [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi V, Ghosh A, Garg A, Avashia V, Vishwanathan SS, Gupta D, et al. India’s pathway to net zero by 2070: status, challenges, and way forward. Environmental Research Letters 2024;19. [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra S, Pohit S. Charting the path to a developed India: Viksit Bharat 2047. 2024.

- Angel Hernandez M Del, Bakthavatchaalam V. Circular economy as a strategy in European automotive industries to achieve Sustainable Development: A qualitative study. n.d.

- Balcioglu YS, Sezen B, İşler AU. Evolving preferences in sustainable transportation: a comparative analysis of consumer segments for electric vehicles across Europe. Social Responsibility Journal 2024;20:1664–96. [CrossRef]

- Mohit, Pawar R. Driving sustainable energy in India: The role of demand-side management in power optimization and environmental conservation. Energy Sources, Part A: Recovery, Utilization and Environmental Effects 2024;46:14089–117. [CrossRef]

- Robinson AL, Taub AI, Keoleian GA. Fuel efficiency drives the auto industry to reduce vehicle weight. MRS Bull 2019;44:920–2. [CrossRef]

- Kopparthy SDS, Netravali AN. Review: Green composites for structural applications. Composites Part C: Open Access 2021;6. [CrossRef]

- Barman P, Dutta L, Bordoloi S, Kalita A, Buragohain P, Bharali S, et al. Renewable energy integration with electric vehicle technology: A review of the existing smart charging approaches. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2023;183. [CrossRef]

- Mata TM, Smith RL, Young DM, Costa CAV. Environmental analysis of gasoline blending components through their life cycle. J Clean Prod, vol. 13, Elsevier Ltd; 2005, p. 517–23. [CrossRef]

- Giammaria V, Capretti M, Del Bianco G, Boria S, Santulli C. Application of Poly(lactic Acid) Composites in the Automotive Sector: A Critical Review. Polymers (Basel) 2024;16. [CrossRef]

- Yang Y, Wan H, Wang B, Wang B, Chen K, Tan H, et al. Preparation and properties of bamboo fiber/polylactic acid composite modified with polycarbodiimide. Ind Crops Prod 2024;218. [CrossRef]

- Sanivada UK, Mármol G, Brito FP, Fangueiro R. Pla composites reinforced with flax and jute fibers—a review of recent trends, processing parameters and mechanical properties. Polymers (Basel) 2020;12:1–29. [CrossRef]

- Fang X, Li Y, Zhao J, Xu J, Li C, Liu J, et al. Improved interfacial performance of bamboo fibers/polylactic acid composites enabled by a self-supplied bio-coupling agent strategy. J Clean Prod 2022;380. [CrossRef]

- Bajpai PK, Singh I, Madaan J. Development and characterization of PLA-based green composites: A review. Journal of Thermoplastic Composite Materials 2014;27:52–81. [CrossRef]

- Roy P, Defersha F, Rodriguez-Uribe A, Misra M, Mohanty AK. Evaluation of the life cycle of an automotive component produced from biocomposite. J Clean Prod 2020;273. [CrossRef]

- Melo de Lima LR, Dias AC, Trindade T, Oliveira JM. A comparative life cycle assessment of graphene nanoplatelets- and glass fibre-reinforced poly(propylene) composites for automotive applications. Science of the Total Environment 2023;871. [CrossRef]

- Maurya AK, Manik G. Advances towards development of industrially relevant short natural fiber reinforced and hybridized polypropylene composites for various industrial applications: a review. Journal of Polymer Research 2023;30. [CrossRef]

- Qiao Y, Fring LD, Pallaka MR, Simmons KL. A review of the fabrication methods and mechanical behavior of continuous thermoplastic polymer fiber–thermoplastic polymer matrix composites. Polym Compos 2023;44:694–733. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal J, Sahoo S, Mohanty S, Nayak SK. Progress of novel techniques for lightweight automobile applications through innovative eco-friendly composite materials: A review. Journal of Thermoplastic Composite Materials 2020;33:978–1013. [CrossRef]

- Delogu M, Zanchi L, Dattilo CA, Pierini M. Innovative composites and hybrid materials for electric vehicles lightweight design in a sustainability perspective. Mater Today Commun 2017;13:192–209. [CrossRef]

- Gupta P, Toksha B, Patel B, Rushiya Y, Das P, Rahaman M. Recent Developments and Research Avenues for Polymers in Electric Vehicles. Chemical Record 2022;22. [CrossRef]

- Prasanth SM, Kumar PS, Harish S, Rishikesh M, Nanda S, Vo DVN. Application of biomass derived products in mid-size automotive industries: A review. Chemosphere 2021;280. [CrossRef]

- Yousaf A, Al Rashid A, Polat R, Koç M. Potential and challenges of recycled polymer plastics and natural waste materials for additive manufacturing. Sustainable Materials and Technologies 2024;41. [CrossRef]

- Shanmugam V, Mensah RA, Försth M, Sas G, Restás Á, Addy C, et al. Circular economy in biocomposite development: State-of-the-art, challenges and emerging trends. Composites Part C: Open Access 2021;5. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho D, Ferreira N, França B, Marques R, Silva M, Silva S, et al. Advancing sustainability in the automotive industry: Bioprepregs and fully bio-based composites. Composites Part C: Open Access 2024;14. [CrossRef]

- Singh V, Singh V, Vaibhav S. Analysis of electric vehicle trends, development and policies in India. Case Stud Transp Policy 2021;9:1180–97. [CrossRef]

- Mittal G, Garg A, Pareek K. A review of the technologies, challenges and policies implications of electric vehicles and their future development in India. Energy Storage 2024;6. [CrossRef]

- Nagaraja S, Anand PB, Mohan Kumar K, Ammarullah MI. Synergistic advances in natural fibre composites: a comprehensive review of the eco-friendly bio-composite development, its characterization and diverse applications. RSC Adv 2024;14:17594–611. [CrossRef]

- Gupta P, Toksha B, Patel B, Rushiya Y, Das P, Rahaman M. Recent Developments and Research Avenues for Polymers in Electric Vehicles. Chemical Record 2022;22. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed M, Oleiwi JK, Mohammed AM, Jawad AJM, Osman AF, Adam T, et al. A Review on the Advancement of Renewable Natural Fiber Hybrid Composites: Prospects, Challenges, and Industrial Applications. J Renew Mater 2024;12:1237–90. [CrossRef]

- Islam T, Chaion MH, Jalil MA, Rafi AS, Mushtari F, Dhar AK, et al. Advancements and challenges in natural fiber-reinforced hybrid composites: A comprehensive review. SPE Polymers 2024. [CrossRef]

| Fiber/Filler | Annual Production (Dry Metric Tons Per Year) |

Cellulose (%) |

Hemicellulose (%) | Lignin (%) |

Pectin (%) |

Waxes (%) |

Extractive (%) |

Moisture Content (%) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Banana Fiber | 1,19,000 | 60–85 | 6-8 | 5-10 | 2.5-4 | -- | -- | 10-12 | [68] |

| Coconut Coir | 3,50,000 | 32-43 | 4-12 | 40-49 | 3-8 | -- | -- | 4-8 | [69] |

| Corn Cob | 1,15,000 | 55-65 | 5-8 | 15-18 | -- | -- | 5-8 | 10-13 | [70,71] |

| Date Palm | 4,80,000 | 39.90 | 31.50 | 22.50 | -- | -- | -- | -- | [72,73] |

| Ground nutshell | 3,00,000 | 37 | 9 | 41 | -- | -- | 13 | -- | [74,75] |

| Orange Peel | 5,00,000 | 9.2 | 5.4 | 1.2 | 22.0 | 0.7 | 2.0 | 79.1 | [76,77] |

| PALF | 13,18,000 | 70-80 | 10-15 | 5-12 | 1-1.2 | 3.3 | 6.6 | 2-5 | [17,78] |

| Rice Husk | 120,000,000 | 35-40 | 15-20 | 20-25 | 3-5 | -- | 5-8 | -- | [79,80] |

| Sugarcane Bagasse | 1,50,000 | 36-50 | 16-25 | 25-29 | -- | 0.6-5 | 3-5 | -- | [81] |

| Wheat Straw | 720,000,000 | 33–45 | 19–32 | 8–16 | -- | -- | -- | -- | [82] |

| Wood Floor | 1,750,000,000 | 40–45 | 30 | 25-35 | 0-1 | 0.4-0.5 | 2-5 | -- | [25] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).