1. Introduction

Prostaglandin (PG) is released into the cell by chemical and neural stimulation when the cell membrane is stimulated by phospholipase A

2 in the cytoplasm, which decomposes arachidonic acid and releases it into the cell. Arachidonic acid is oxidized by reduced glutathione and cyclooxygenase (COX) to produce prostaglandin G

2 (PGG

2) [

1]. PGG

2 is transformed into PGH

2 by prostaglandin endoperoxidase, from which various substances such as PGE

2, thromboxane A, and PGI are synthesized [

2]. PG, synthesized from polyunsaturated fatty acids and metabolized in a short period, has been shown to suppress cardiovascular disease by promoting muscle contraction and relaxation, lowering blood pressure, weakening or strengthening blood coagulation, promoting ion transport to the cell membrane, and activating inflammatory responses [

3]. PGE

2 promotes wound healing by regulating fibroblasts at the wound site when COX2 increases within the cell when the dermis is damaged [

4] and has a positive therapeutic effect on peptic ulcers by promoting the inhibition of gastric contraction, mucus secretion in the duodenum, and secretion of vascular endothelial growth factor [

5], which is known to be an important mediating factor in hair formation, bone formation, and prevention of peripheral vascular disease [

6]. Wound healing is a complex process involving many interconnected stages, such as hemostasis, inflammatory cell exudation, angiogenesis, graduate fibrosis, and tissue remodeling [

7]. Various factors, including growth factors, cytokines, matrix metalloproteinases, and extracellular matrix proteins, influence the healing process [

8]. For example, fibroblast growth factor, platelet-derived growth factor, interleukin-1α, and epidermal growth factor have been shown to play beneficial roles in wound healing [

9]. Additionally, corticosteroids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs delay wound healing, and this effect is thought to result from the inhibition of PGE

2 biosynthesis [

10].

Quercus mongolica (QM) Fisch. ex Turcz is a deciduous broadleaf tree species and a member of the genus

Quercus. It is primarily distributed in eastern Mongolia, the Russian Far East, northern and northeastern China, Japan, and the Korean Peninsula [

11]. In China, Korea, and Japan, QM leaves have traditionally been used as folk medicine to treat a variety of ailments, including bacterial dysentery, acute gastroenteritis, dyspepsia in children, jaundice, bronchitis, hemorrhoids, burns, wounds, mild diarrhea, fever, enteritis, and minor oral mucosal inflammation [

12]. QM seeds are used for their tonic, astringent, anti-poisoning, and wrinkle-removing properties [

13]. Yin et al. investigated the anti-inflammatory activity of ethanol extracts from QM branches and suggested that these extracts may exert anti-inflammatory effects by suppressing NF-κB and mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways and inducing HO-1 expression in LPS-induced RAW264.7 cells [

14]. The anti-photoaging effects of the phenolic compounds isolated from QM leaves have been evaluated in ultraviolet-irradiated human fibroblasts [

15]. Additionally, the five-alpha reductase inhibitory activity, nitric oxide inhibitory activity, inflammasome inhibitory activity, and anti-acne vulgaris effects of pedunculagin isolated from QM leaves have been studied [

16]. Salminen et al. reported that water-soluble extracts of QM leaves exhibit strong antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory effects because of their high hydrolytic tannin content, including gallotannins and ellagitannins [

17]. Tian et al. studied the essential oil from

Quercus mongolica bark (QMB) for its potential bioactivity and chemical composition, indicating that the essential oil from QMB may act as a potential natural anticoagulant and offer new opportunities for the medicinal development of QMB [

18]. Kong et al., investigated the antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of QM leaf extracts. This study showed that these extracts helped reduce free radicals and inhibit microbial growth of

Staphylococcus aureus, Salmonella typhimurium, Escherichia coli O157, and

Pseudomonas aeruginosa. This indicates that it is important to use hexane and chloroform extracts for medicinal and cosmetic applications [

19]. Eo et al. investigated QMB extracts on the anti-inflammatory activity and their potential signaling pathways in LPS-induced RAW264.7 cells. These results suggest that QMB may exhibit anti-inflammatory activity by suppressing NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways and inducing HO-1 expression [

20]. Although several biological activities of QM leaves and bark have been examined, there is limited information on the wound healing properties of flavonoids obtained from

Quercus mongolica (QMB-flavonoid).

Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the wound healing potential of QMB-flavonoid by investigating cytotoxicity, 15-PGDH inhibitory activity, PGE2 release, mRNA expression of related genes (Cox1/2, PGT, MRP4, LMO2, GATA2, RUNX1, SCL, KDR, and C-MYB), collagen biosynthesis, as well as in vitro and in vivo wound healing activities.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Isolation of QMB-Flavonoid

The isolation of QMB-flavonoid was carried out using a supercritical fluid extraction (SFE-CO₂) system with an ISCO SFX 3560 (Lincoln, NE, USA) dual-pump setup. A total of 1 g of finely ground, dried herb was blended with 5 g of 50–100 mesh sand (SX0075-3, EM Sciences, USA) and placed inside the SFE cartridge. The extraction process included an initial static phase lasting 5 minutes, followed by a 30-minute dynamic extraction. Carbon dioxide (Airgas UN1013, Radnor, PA, USA) was supplied at a rate of 0.5 kg/h. The restrictor was maintained at 40 °C, while the extraction pressure was set to 40 MPa. Extractions were conducted at temperatures of 40, 60, and 80 °C. Setting the restrictor at 60 °C ensured that the extraction occurred within a 20 °C range of the restrictor temperature. Extracts were dissolved in 10 mL of ethanol. Each condition was tested in triplicate, with an extraction duration of 180 minutes and a particle size of 0.4 mm. Additionally, SFE-CO₂ extraction was performed using a 10% (v/v) ethanol modifier, with all other parameters unchanged. The resulting flavonoid extracts were designated as QMB-flavonoid.

2.2. Cell Culture

HaCaT cells were cultured in Dulbeco’s modified eagle’s medium (DMEM) medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% double antibody (mixed liquid of penicillin and streptomycin) in a 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator. The cells observed under a microscope were adherent. 2 mL of 3x105/mL HaCaT cells was added to a 6-well plate, and incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 18 h.

2.3. Cytotoxicity

90 μL of 5x104/mL of human keratinocytes (HaCaT) cells (American Type Culture collection: Manassas, VA, USA) was added to a 96-well plate and incubated at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 18 h. QMB-flavonoids were added and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 48 h. Subsequently, 10 μL of MTT was added, and the incubation was continued for an additional 4 h. Later, 150 μL of DMSO was added, shaken for 10 min, and the absorbance at OD 540nm was detected with a microplate reader.

2.4. 15-PGDH Activity

We obtained the 15-PGDH gene sequence from the NCBI Gene Bank, synthesized it, and designed primers for PCR amplification. The amplified gene was subcloned into the PGEX-4T-1 expression vector after restriction digestion. After double restriction identification, expression vector construction for the 15-PGDH protein was confirmed. The recombinant 15-PGDH vector was transfected into BL21(DE3) Escherichia coli. The bacteria were induced to break, and the protein was separated and purified using glutathione agarose resin to obtain 15-PGDH separated and purified protein. 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 0.1 mM DTT, 0.25 mM NAD+, 10 μg 15-PGDH protein, and 21 μM PGE2 were added, and the content of NADH formed by the reaction was measured with a fluorescence spectrophotometer at the excitation wavelength of 340 nm and emission wavelength of 468 nm. The inhibitory effect of 15-PGDH was measured by the drawn NADH standard curve.

2.5. PGE2 Content

To evaluate the PGE₂ release of QMB-flavonoid, 2 mL of 2.5 × 10⁵/mL HaCaT cells were added to a 6-well plate and incubated at 37°C with 5% CO₂ for 18 h. Samples were then added at six sample concentrations, and the cells were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO₂ for an additional 12 h. After incubation, the supernatant was collected and the amount of PGE₂ released was measured using a PGE2 kit.

2.6. Collagen Synthesis

To evaluate the collagen synthesis efficacy of QMB-flavonoid, normal human fibroblast cells were divided into 24 well-plate at 1×104 per well and incubated for approximately 24 h under 37oC, 5% CO2 conditions by adding 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin until approximately 80% confluence was reached. After 48 h of treatment with QMB-flavonoid at various concentrations, the culture supernatant was collected, and collagen synthesis was evaluated using the Procollagen Type I C-Peptide (PIP) EIA Kit (MK101; Takara Shuzo, Kyoto, Japan). The amount of collagen was corrected for the total amount of protein.

2.7. cDNA Synthesis and PCR Amplification

Total cellular RNA was isolated from HaCaT cells using TRI reagent (RNAiso Plus, Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and reverse transcription was performed using a cDNA synthesis kit (Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan). After synthesis, cDNA was amplified using the primer pairs listed in

Table 1. Real-time PCR was performed with the FTC3000 real-time PCR system (Funglyn Biotech, TO, Canada) using the SYBR Green PCR kit (Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Real-time PCR was performed using the following cycling conditions: 4 min at 95

oC, followed by 35 cycles of 94

oC for 20 s, 60

oC for 25 s, and 72

oC for 30 s. Relative mRNA expression levels were expressed as the ratio of the comparative threshold cycle to the expression levels of human β-Actin.

2.8. Wound Healing Test In Vitro

HaCaT cells were cultured in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% double antibody (mixed liquid of penicillin and streptomycin) under 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator. The cells observed under a microscope were adherent. After the control and experimental groups were digested and counted, 8×105 cells were seeded into 35 mm2 Petri dishes and cultured overnight. A marker pen was used to draw a line on the bottom of the dish as a mark, aspirate the culture medium, and a 10 μL pipette tip was used to mark the cells in the dish perpendicularly to the mark. The cells were rinsed with PBS to remove the marked cells and then processed. Each group consisted of 2 replicates. This was placed in a 37°C incubator for cultivation. Pictures were taken at 0 and 48 h after scratching, and the intersection of the line drawn by the marker pen and the cell scratch was observed at a fixed point.

2.9. Wound Healing Test In Vivo

SD rats (purchased from Sibor-Bikai Animal Experiment Center) were adaptively reared for one week, anesthetized with 10% of chloral hydrate at the rate of 4 mL/Kg, and their back hair was shaved using a shaving machine. The skin was wiped with alcohol, and a 1 × 1 cm round wound was cut on the back of the rat. To prevent skin contractions from affecting experimental results, a rubber ring was sewn around the wound to fix the surrounding skin. Blank group: A pipette was used to draw 0.2 mL of sterile sodium chloride solution (0.9%) for the wound every morning and afternoon, and pictures of the wound were taken every three days. The sample dose provided was 500 mg/mL, diluted to a concentration of 0.15 mg/mL (physiological saline) for smear administration (200 µL per administration, that is, 30 µg/mouse/time). Each morning and afternoon, 0.2 mL of the prepared drug solution was drawn onto the wound using a pipette, and pictures of the wound were taken every three days.

2.10. HE Staining

On the fourth and seventh days of surgical treatment, one rat from each group was sacrificed by neck removal, and the unhealed skin of the wound was fixed and embedded in preparation for HE staining. After the experiment, all rats were sacrificed by neck removal, and wound-healing tissues were fixed and embedded in preparation for HE staining. The slides were placed in 65°C oven for 30 min; the slides were then soaked in xylene I for 15 min, before being immersed in xylene II for 15 min. Deparaffinized sections were soaked in 100%, 95%, 85%, and 75% ethanol for 5 min and rinsed with tap water for 10 min. The slices were placed in distilled water, stained in a hematoxylin solution for 5 min, and separated in ammonia water for a few seconds. The sections were rinsed with running water for 15 min and dehydrated in 70% and 90% ethanol for 10 min each. The sections were stained with alcohol-eosin staining solution for 1-2 min, and then dehydrated using pure ethanol. Place the slides in xylene for 3min for transparency (twice), seal the slides with neutral gum, and put them in an oven at 65°C for 15 min. Relevant parts of the samples were collected and analyzed using a microscope.

2.11. Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The results were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) program Ver. 21.0. The statistical significance of the differences between the mean values was determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Duncan’s multiple range test. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Result and Discussion

Flavonoids are polyphenolic compounds abundant in nature, play important roles in plants, and offer various health benefits to humans. Recent studies have shown that flavonoids exert bioactive effects that contribute to disease prevention and health promotion. Flavonoids, such as quercetin and catechins, help neutralize ROS, thus preventing cellular damage. This antioxidant activity can help prevent cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and neurodegenerative disorders [

21]. Flavonoids also suppress inflammation by inhibiting compounds like COX-2 and TNF-α, which trigger inflammation. Epigallocatechin gallate in green tea is particularly effective at reducing inflammation. This anti-inflammatory effect can help prevent conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, asthma, and cardiovascular diseases [

22]. Flavonoids play significant roles in inhibiting cancer cell growth, inducing apoptosis, and preventing metastasis. These studies show that flavonoids can suppress cancer development, with flavonoids exhibiting potent anticancer effects against lung and gastric cancer. Flavonoids may also help reduce the side effects [

23]. In cardiovascular health, flavonoids help to dilate blood vessels, lower blood pressure, and regulate cholesterol levels. They also prevent blood clot formation and contribute to the prevention of CVDs. Flavonoids such as resveratrol have cardioprotective effects [

24]. Flavonoids positively affect the nervous system by reducing brain inflammation, protecting the nerve cells, and promoting nerve regeneration. These results can help prevent and treat neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease, while improving memory and cognitive function [

25]. Although several biological activities of flavonoids have been examined, there is limited information on the wound healing properties of QMB-flavonoids. To evaluate the wound healing effects of QMB-flavonoid, cytotoxicity, 15-PGDH inhibitory activity, PGE

2 release, Cox1/2, PGT, MRP4, LMO2, GATA2, RUNX1, SCL, KDR, and C-MYB expression, collagen biosynthesis, and wound healing activity

in vitro and

in vivo were investigated.

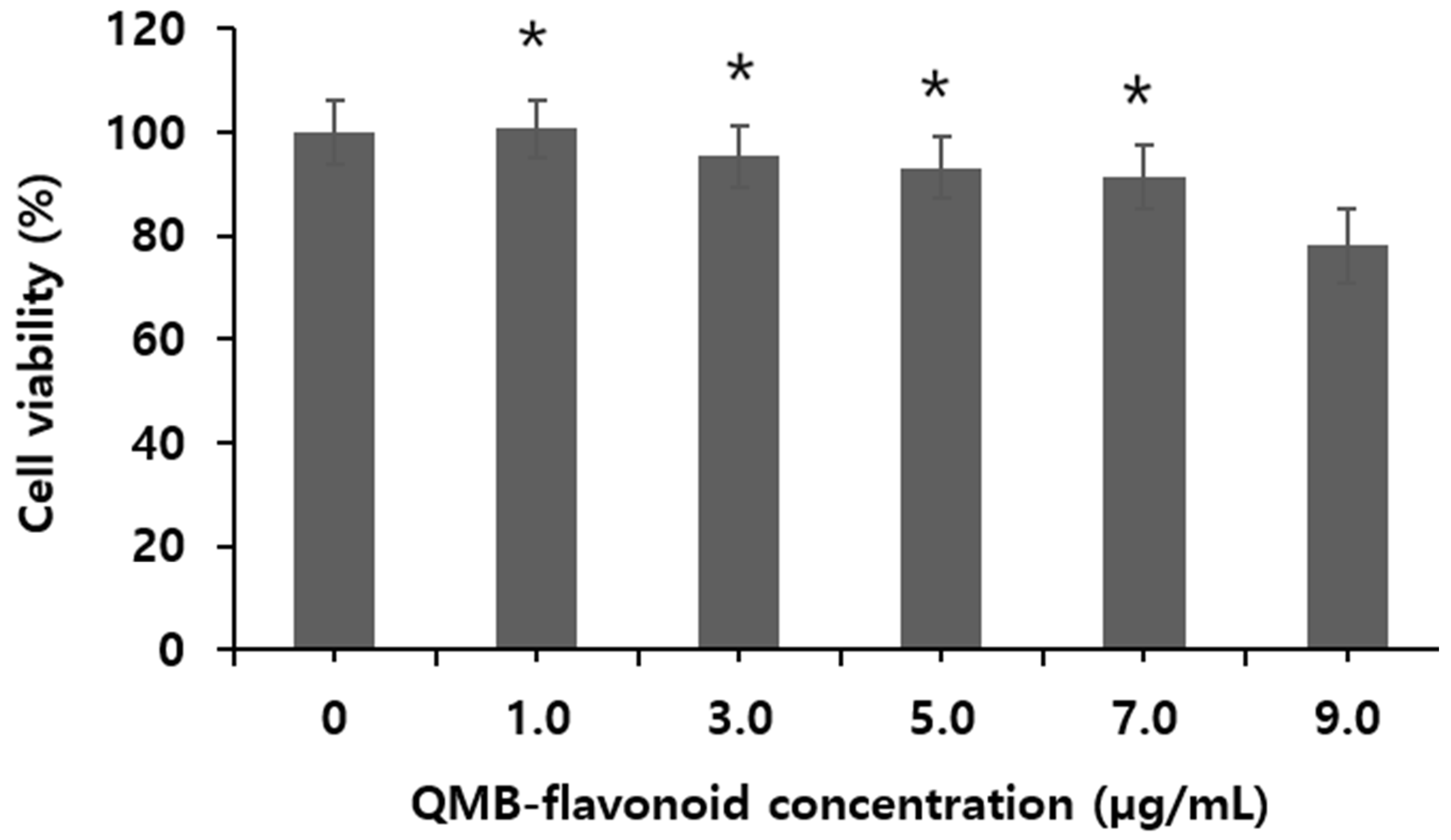

3.1. Cytotoxicity

Figure 1 shows the viability of HaCaT cells treated with QMB-flavonoid obtained from

Quercus mongolica bark. The results indicate that at different concentrations (1.0, 3.0, 5.0, 7.0, and 9.0 μg/mL), QMB-flavonoid maintained over 91.2 ± 3.20 % cell viability at concentrations below 7.0 μg/mL, demonstrating no toxicity in HaCaT cells. Consequently, experiments on 15-PGDH inhibitory efficacy, PGE

2 release, collagen synthesis and wound healing activity were conducted at concentrations under 7.0 μg/mL, which did not exhibit toxicity. The results showed that the toxicity of QMB-flavonoid in HaCaT cells was greater than 7.0 µg/mL.

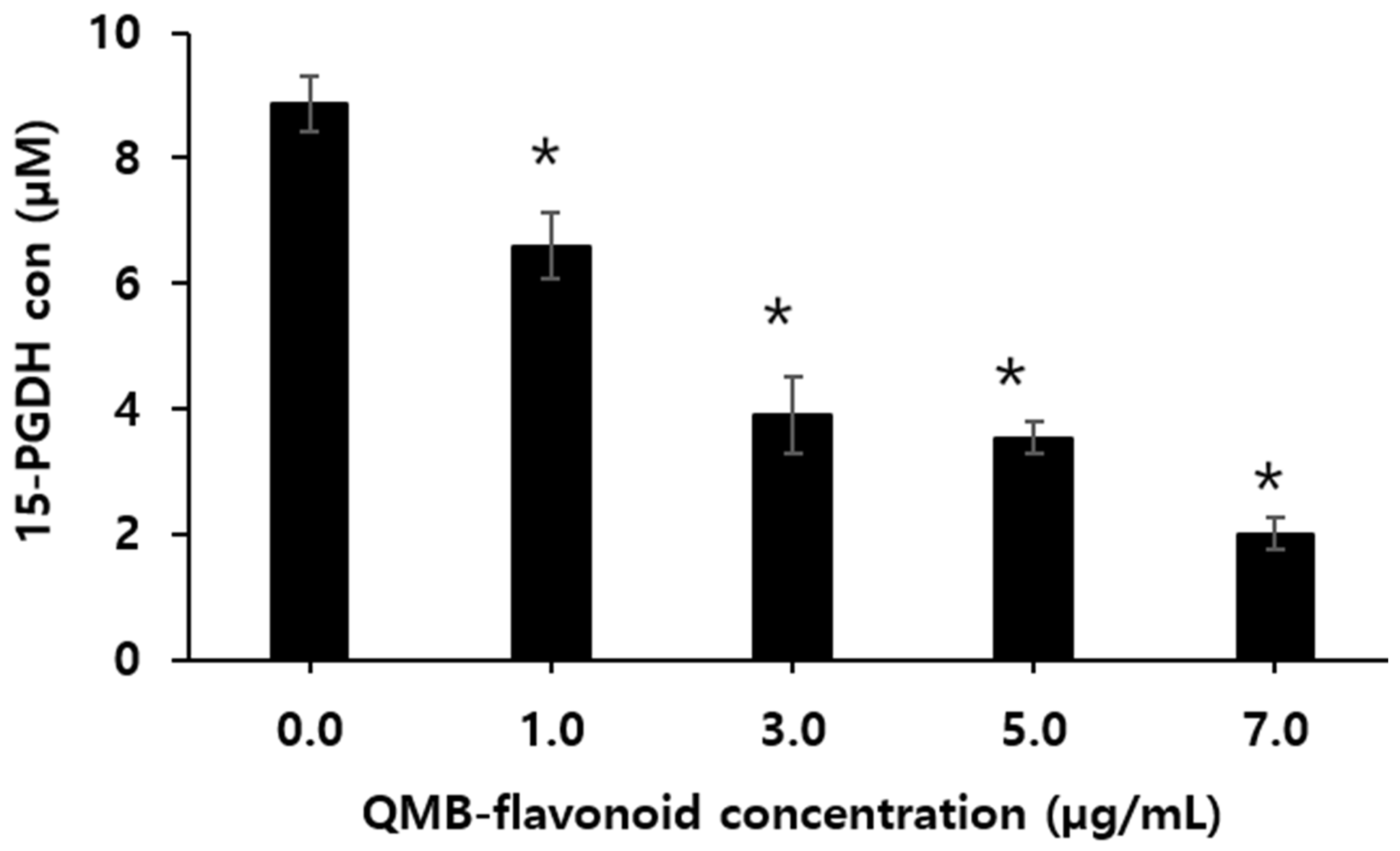

3.2. 15-PGDH Inhibitory Activity

15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase (15-PGDH) is a key enzyme in the biodegradation of prostaglandins, which has a physiological antagonistic effect on COX2, and its expression is related to the occurrence and development of various tumors [

26]. Because prostaglandins can cause strong uterine contractions, they have been used in term pregnancy induction, artificial abortion, and contraception, and have achieved certain effects [

27]. However, PGE

2 has a very short half-life in the body and is rapidly metabolized and inactivated by the NAD

+-dependent 15-PGDH. 15-PGDH is an enzyme that decomposes PG, which is increased in tissues in which 15-PGDH is not expressed and decreased in tissues in which 15-PGDH is activated. Therefore, when 15-PGDH is suppressed, the concentration of PG increases and its pharmacological action is further enhanced [

28]. Monika et al. [

29] suggested that inhibiting the activity of 15-PGDH increases the intracellular levels of PGE₂, indicating the potential of 15-PGDH inhibitors to be broadly used as therapeutics for promoting tissue regeneration in various organs, including after organ resection, in bone marrow diseases, inflammatory bowel disease, and in the skin and accessory organs. Therefore, enhancing PGE₂ levels in damaged tissues during trauma or surgical procedures could promote cell differentiation and aid in tissue regeneration, potentially leading to faster recovery. Therefore, it is necessary to develop drugs targeting the inhibition of 15-PGDH, which deactivates PGE₂ is necessary.

Figure 2 shows the effect of QMB-flavonoid on 15-PGDH inhibition according to concentration. The inhibitory effect on 15-PGDH increased with the concentrations. Especially, the PGDH activity was 2.06 ± 0.070 µM when QMB-flavonoid concentration was 7.0 µg/mL. In contrast, when no QMB flavonoid was added, it was 8.87 µM. This suggests that QMB-flavonoid possesses strong 15-PGDH inhibitory activity.

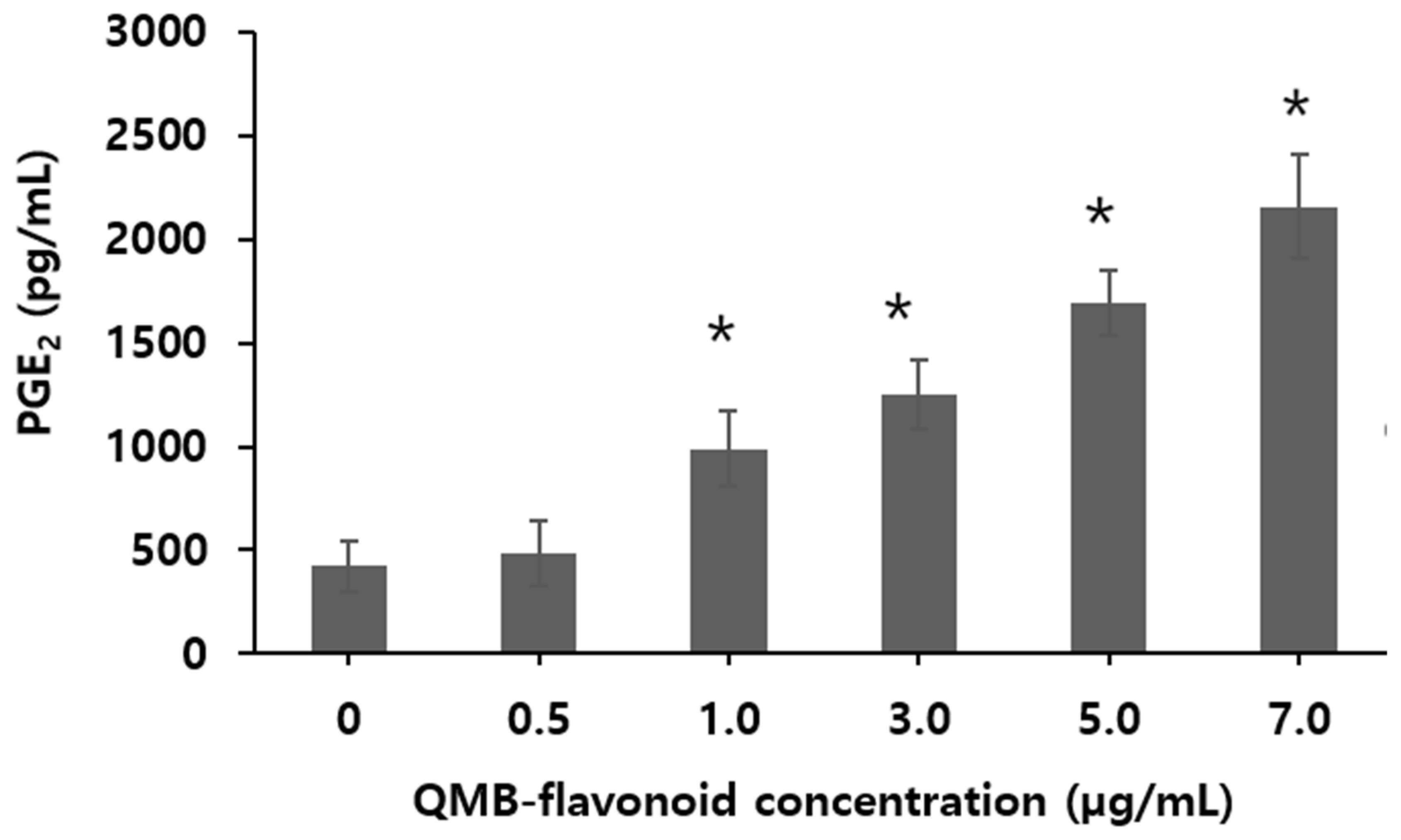

3.3. PGE2 Release

Prostaglandins have a variety of physiological effects. In particular, Prostaglandin E₂ (PGE₂) is a cell growth and regulatory factor produced through a series of enzyme-linked reactions involving arachidonic acid (AA), which is present in various tissues, organs, and body fluids [

30]. Under the catalysis of phospholipase A₂, AA in the cell membrane phospholipids is oxidized and cyclized, then released as free AA. This free AA is transported to the endoplasmic reticulum or nuclear membrane [

31], where it is catalyzed by the rate-limiting enzyme cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) to form Prostaglandin H₂. Prostaglandin H₂ is then converted to PGE₂ by PGE₂ synthase [

32]. High levels of PGE₂ in the body are closely associated with tumor cell proliferation, apoptosis, invasion, metastasis, angiogenesis, chemotherapy resistance, and microenvironmental alterations [

33]. To investigate the PGE₂ release using QMB-flavonoid in HaCaT cells, a range of 0.5 to 7.0 µg/mL were used. The results of PGE

2 release from QMB-flavonoids are shown in

Figure 3. When QMB-flavonoid concentration was increased from zero to 0.5 µg/mL, the release concentration of PGE

2 was not increased. However, from over 1.0 µg/mL of QMB-flavonoid, the concentration of PGE

2 released by QMB- flavonoid increased with the increase of QMB-flavonoid concentration. Especially, when the QMB-flavonoid concentration was increased 5.0 to 7.0 μg/mL, the release concentration of PGE

2 was significantly increased from 1,700 ± 51.3 to 2,500 ± 99.60 pg/mL which was increased by 5.76 times compared with the control group. This result indicated that PGE

2 release was strongly affected by QMB flavonoid concentration.

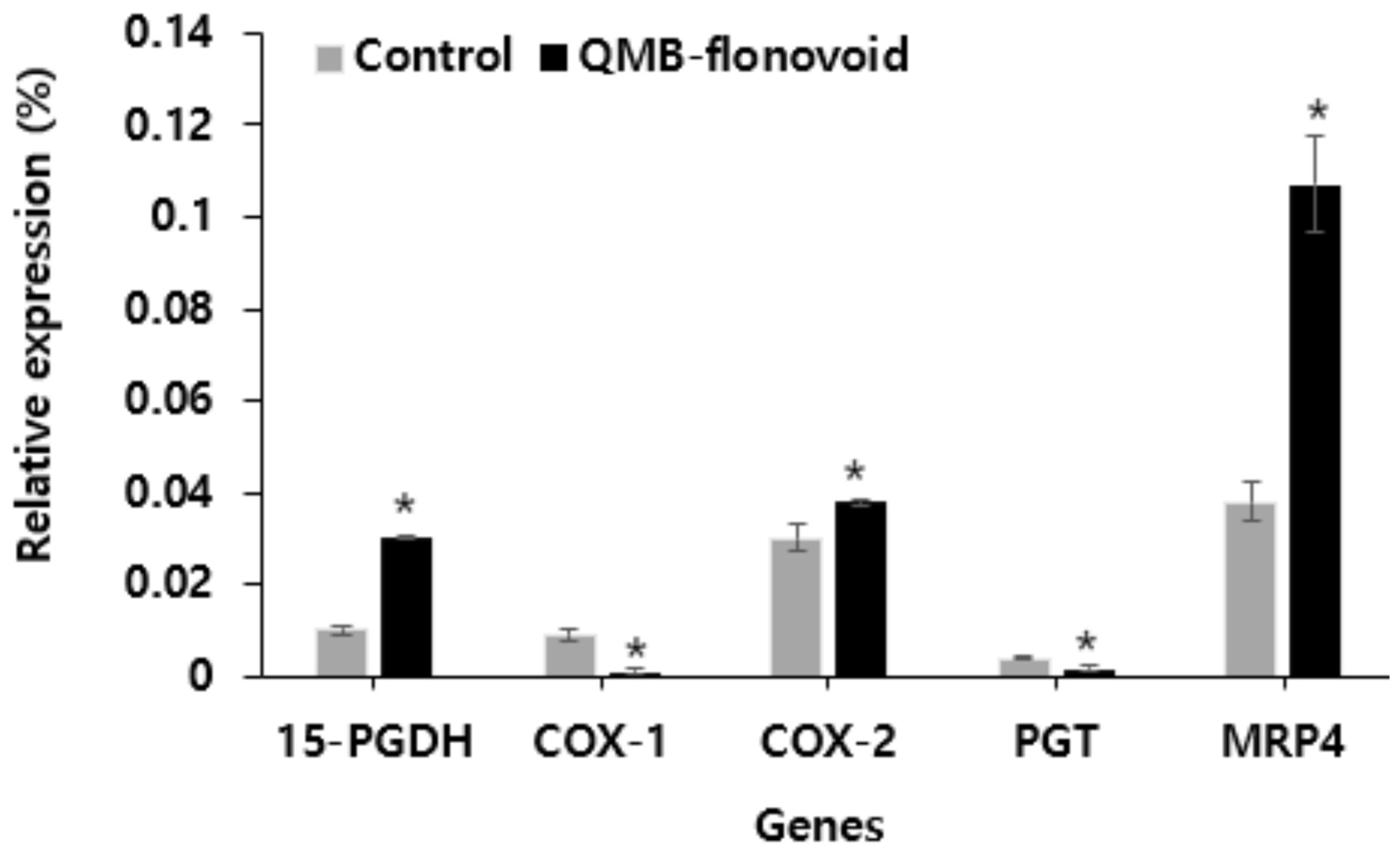

3.4. Cox1/2, PGT and MRP4 Gene Expression

In this study, the effects of QMB-flavonoid on the expression of 15-PGDH, Cox1/2, PGT, and MRP4 in HaCaT cells were investigated. 15-PGDH, Cox1/2, PGT, and MRP4 are involved in the release of PGE

2. The expression levels of these genes were detected using fluorescence quantitative PCR. The results are shown in

Figure 4. Gene expression analysis after QMB-flavonoid treatment. The expression levels of 15-PGDH, COX-1, and PGT were lower than those in the control group. The expression of COX-2 increased slightly compared to that in the control group. Conversely, the expression of MRP4 released into cells was significantly increased compared to that in the control group. This result indicates that QMB-flavonoids increased the expression of MRP4 in cells by inhibiting 15-PGDH, thereby increasing the amount of PGE

2 released outside the cell.

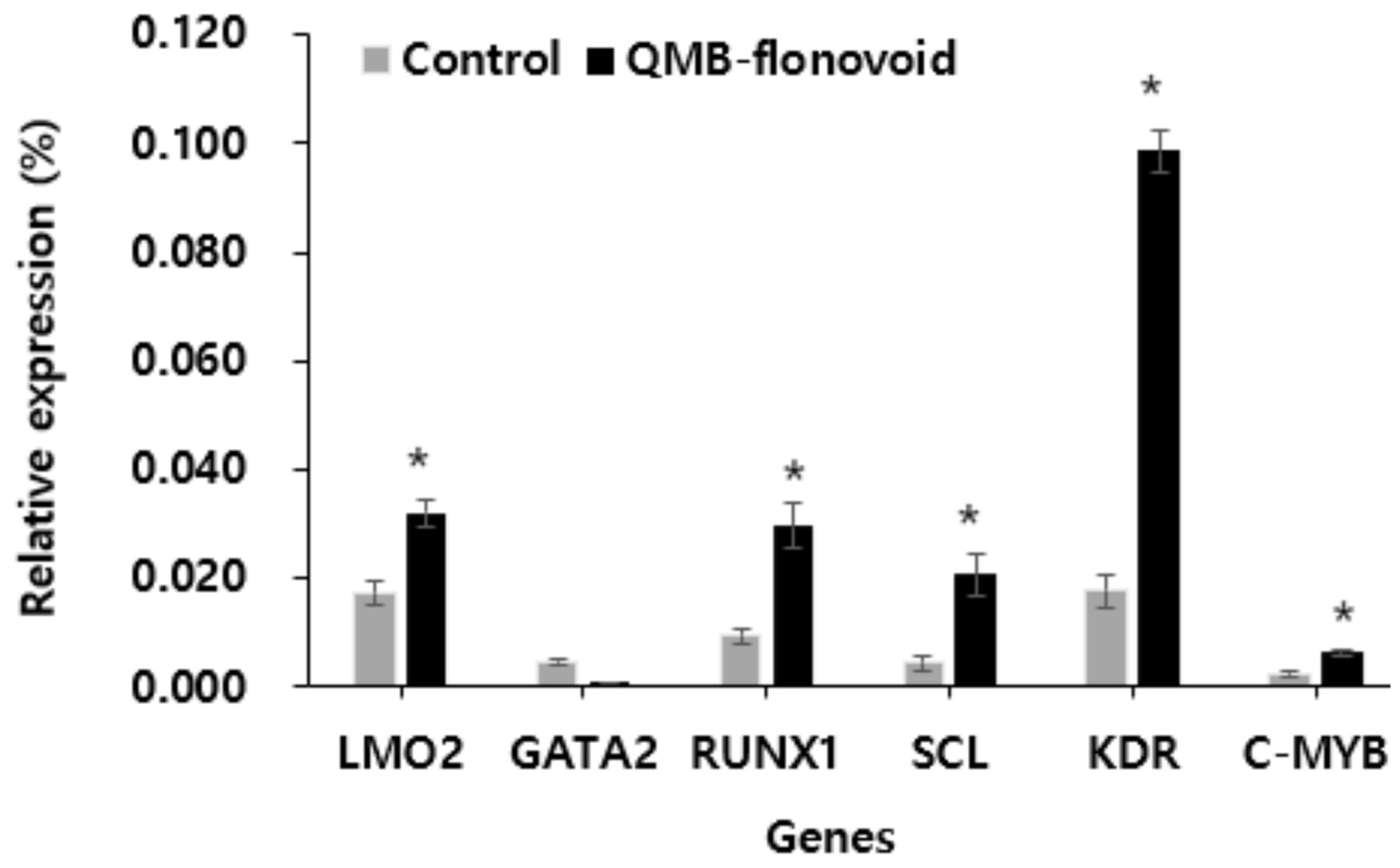

3.5. LMO2, GATA2, RUNX1, SCL, KDR and C-MYB Gene Expression

LMO2, GATA2, RUNX1, SCL, KDR, and c-MYB are involved in cell proliferation. In this study, fluorescence quantitative PCR was used to detect the gene expression of QMB-flavonoid in HaCaT cells. The results are shown in

Figure 5. Gene expression after QMB flavonoid treatment. The expression levels of LMO2, RUNX1, SCL, KDR, and MYB were higher than in the control group. Especially the expression of KDR was significantly increased, which was changed to about 5.1 times compared to the control group. In contrast, the gene expression of GATA2 decreased compared to that in the control group. These results showed that QMB-flavonoids could be used in wound-healing therapy without scar formation.

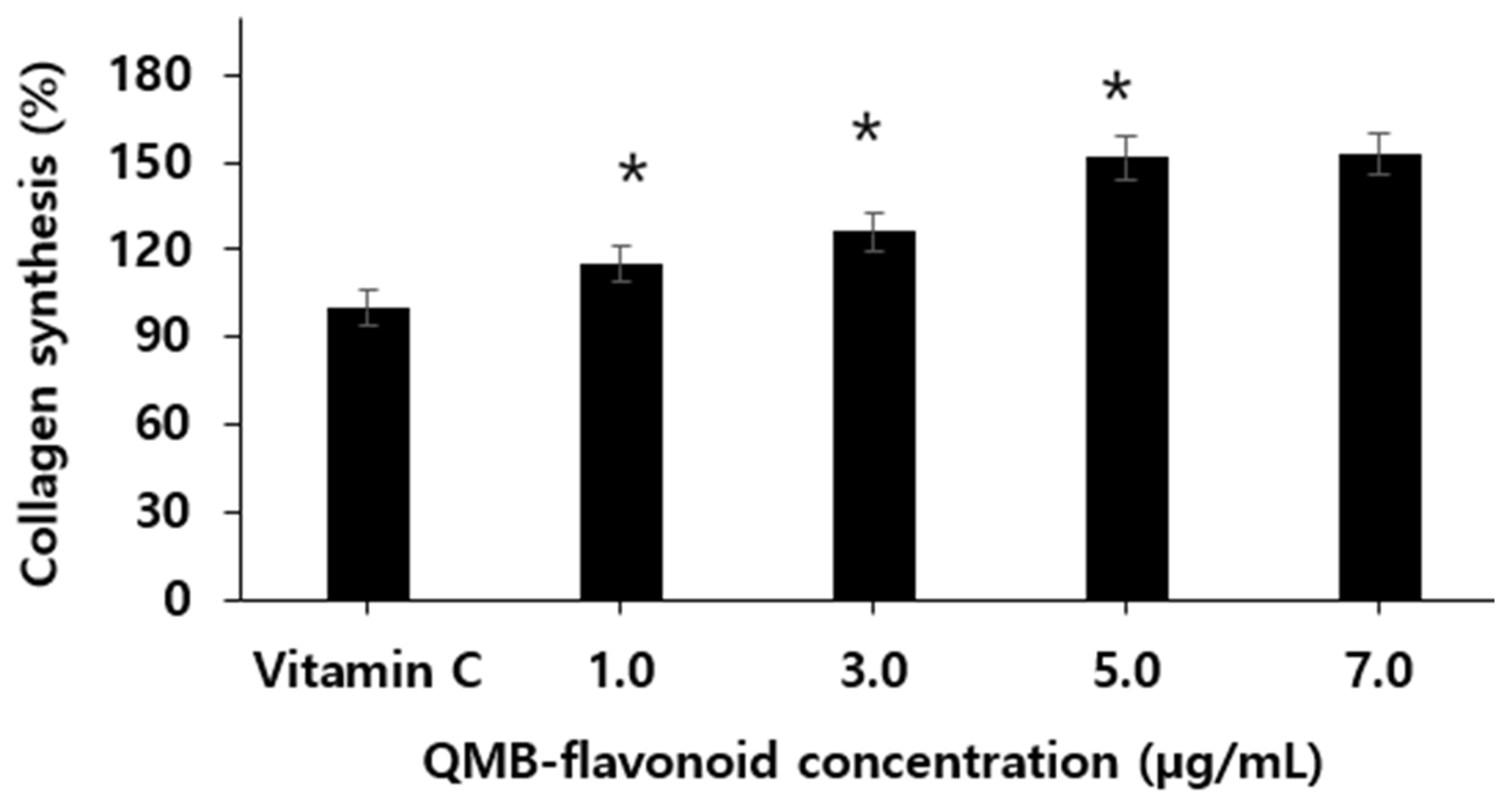

3.6. Collagen Biosynthesis

Collagen, the main protein in the skin, is produced by procollagen in fibroblasts present in the dermis. Procollagen synthesized in fibroblasts is secreted as an extracellular matrix, and C-peptide is decomposed by the procollagen peptidase present on the cell surface and converted into active collagen through a polymerization process [

34,

35]. Using this principle, the rate of increase in collagen production was treated with QMB flavonoids in newborns with human skin fibroblasts, and the amount of procollagen-type IC peptides was measured using an ELISA kit. The results are shown in

Figure 6. When QMB-flavonoid was treated at concentrations of 1.0, 3.0, 5.0, and 7.0 µg/mL, we found that collagen synthesis increased in a concentration-dependent manner. In particular, when the Vitamin C as control group was considered, QMB-flavonoid 5.0 µg/mL increased by more than 151.4 ± 6.90 % compared to the control group, and it was confirmed that QMB-flavonoid promotes collagen synthesis. However, when QMB-flavonoid was treated with 7.0 µg/mL, the collagen content did not significantly increase compared to the concentration of 5.0 µg/mL. From the above results, it can be estimated that QMB-flavonoid can have an effective wound healing effect in preventing skin wrinkles by promoting collagen synthesis.

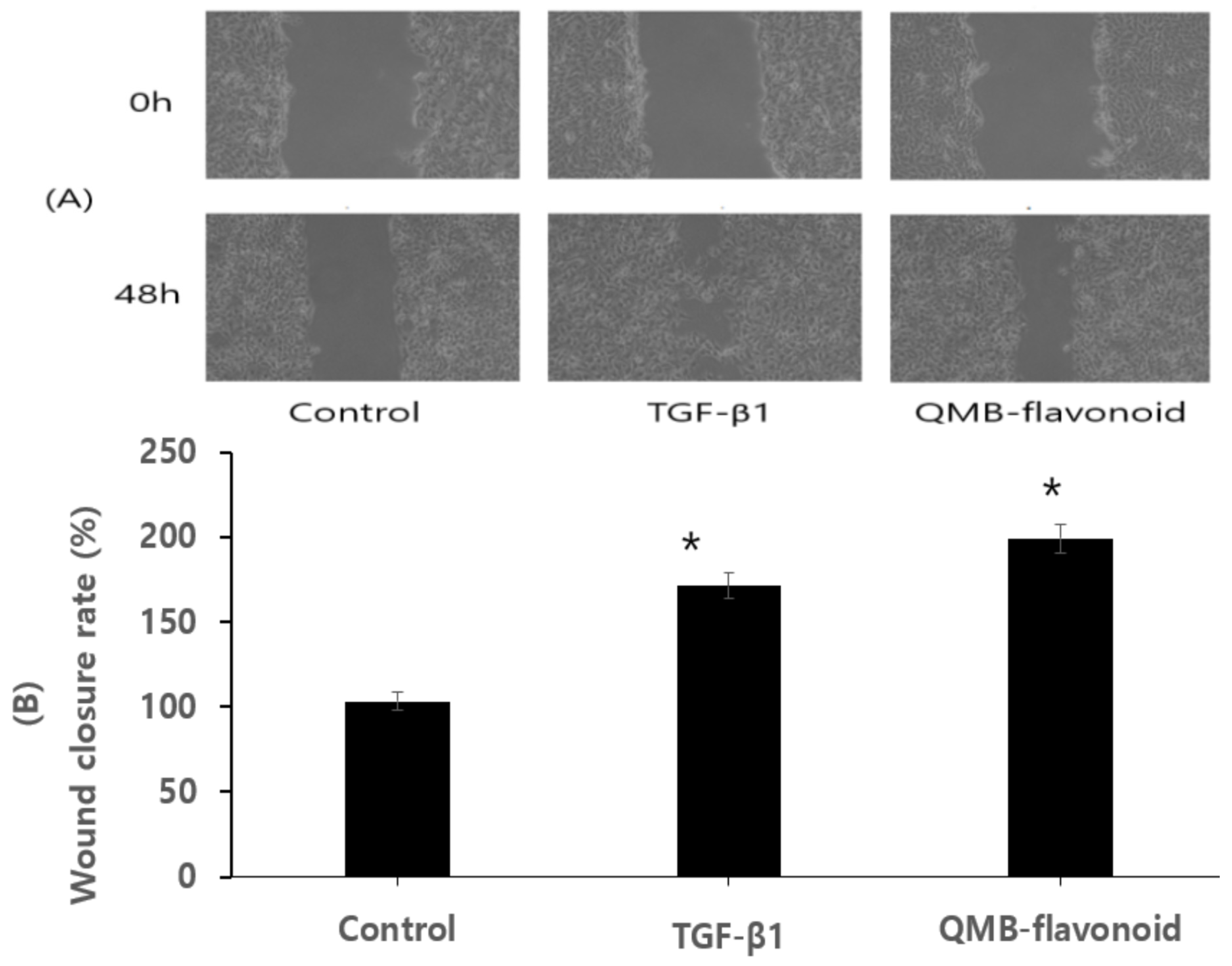

3.7. Wound Healing Effect In Vitro

Re-epithelialization is necessary for wound healing. Wound healing is a complicated process that involves remodeling, extracellular matrix deposition, clot formation, granulation tissue accumulation, and inflammatory responses [

36]. In addition to several mediators released from fibroblasts, inflammatory cells, [

37] and keratinocytes, cellular interactions in the dermis and epidermis play crucial roles in wound healing process [

8]. The wound healing process is affected by various factors such as extracellular matrix proteins, growth factors, metalloproteinases, and cytokines [

38,

39]. Exogenous application of these factors has been verified to support wound regeneration [

40]. To study the effect of QMB-flavonoid on wound healing

in vitro, HaCaT cells were scratched and pictures were taken at 0 and 48 h. In this study, QMB-flavonoid was screened for 15-PGDH inhibitor and used in the experimental group, and TGF-β1 was used as the positive control group.

Figure 7-A showed that the cell growth effects in the TGF-β1 as a positive control group and QMB-flavonoid group was significantly better than that of the control group.

Figure 7-B showed the wound healing efficiency of the control group, TGF-β1 group, and QMB-flavonoid group. After 48 h, TGF-β1 as a positive control group had a 173.6 ± 8.90 % cell growth effect relative to the control group, and QMB-flavonoid group had 199.3 ± 9.95 % cell growth relative to the control group.

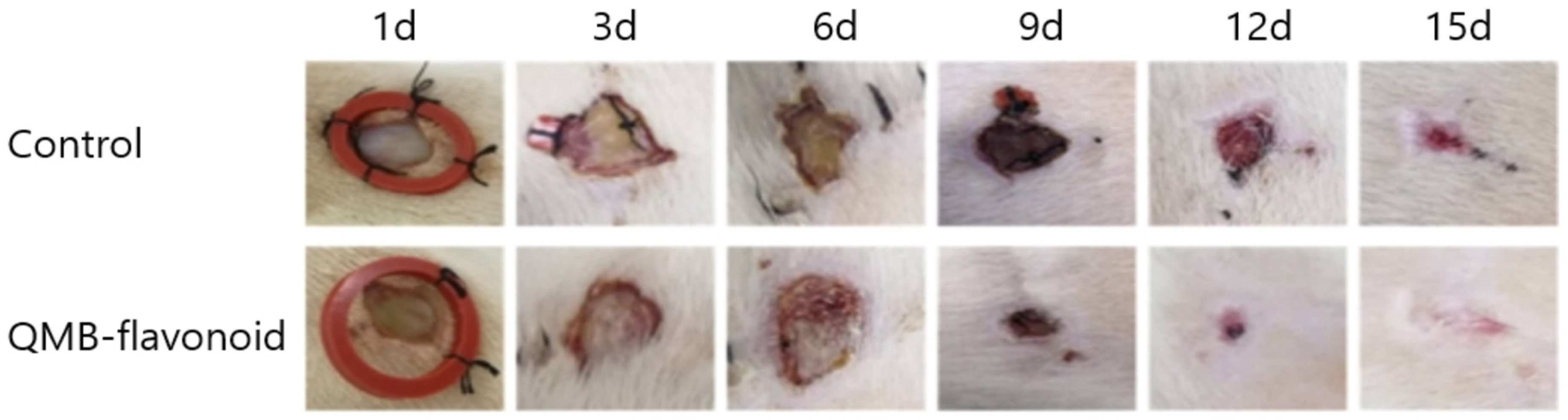

3.8. Wound Healing Effect In Vivo

To evaluate the wound healing effect of QMB-flavonoids

in vivo, especially the effect of epithelial tissue regeneration, perforation biopsy was used to cause skin defects on the backs of SD rats, and pictures were taken every three days. On days 3th, 6th, 9th, 12th, and 15th days, wound-healing tissue was collected, fixed, embedded, and stained with HE.

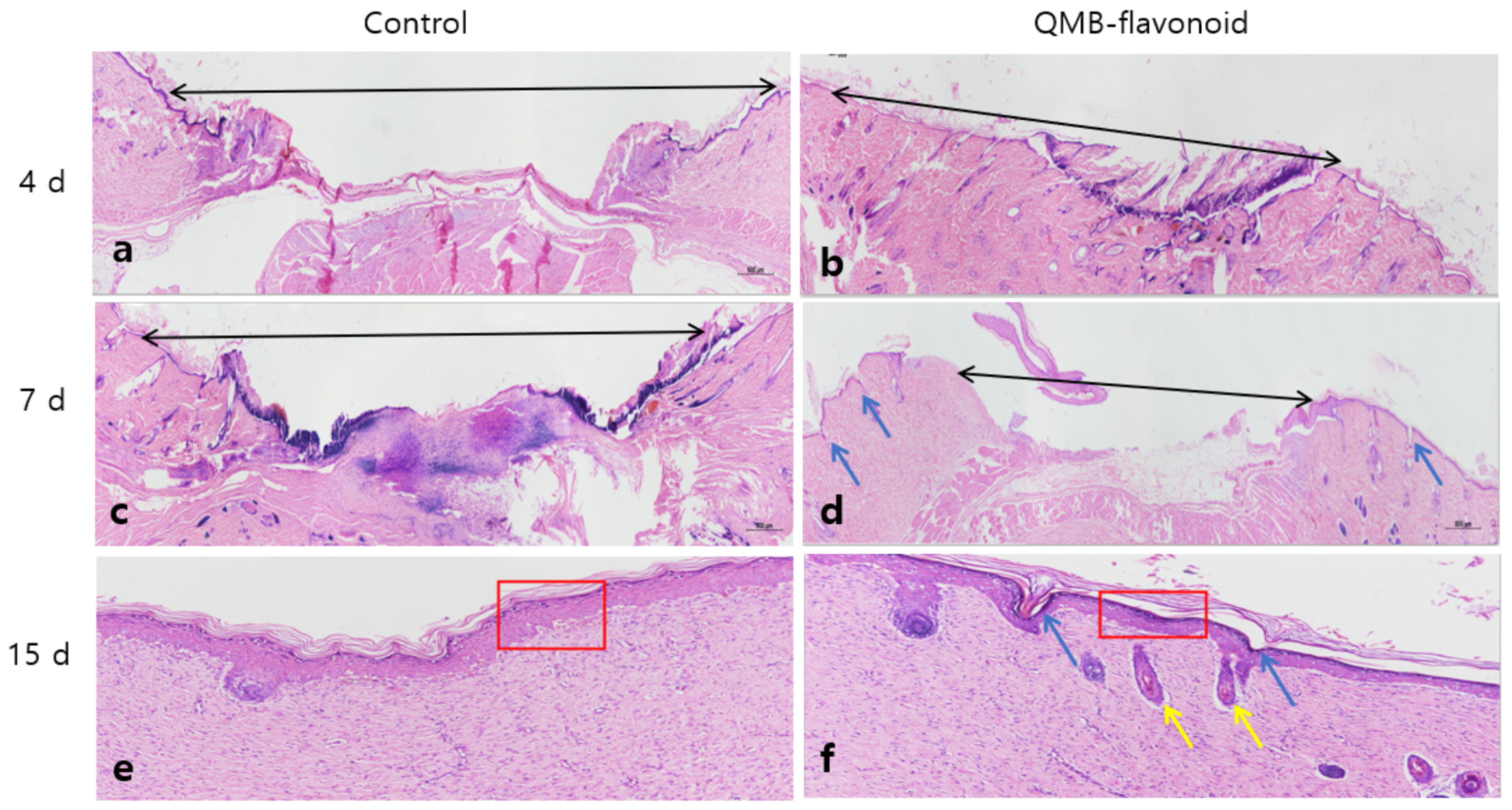

Figure 8 shows that the QMB-flavonoid group, compared to the control group, had an obvious wound healing effect from the 3rd days, and the wounds in the QMB-flavonoid group were healed by the 15th days. The wound healing effect in the QMB-flavonoid group was significantly better than that in the control group. As shown in

Figure 9. HE staining on days 4th and 7th days showed that the wounds in the QMB-flavonoid group were significantly smaller than those in the control group. On the 15th day, the wounds in the QMB-flavonoid group had more cysts and hair bulbs than those in the control group, and the QMB-flavonoid group had a thinner epidermis than that in the control group, indicating that QMB-flavonoid had a good wound healing effect. This result shows that wound healing improvement was greatly affected by QMB-flavonoid in rats.

4. Conclusion

QMB-flavonoid, demonstrated no toxicity in HaCaT cells at concentrations below 7.0 μg/mL, maintaining over 91.2 ± 3.20 % cell viability. Subsequent experiments on 15-PGDH inhibition, PGE2 release, collagen synthesis, and wound healing were conducted within this non-toxic concentration range. It was found that QMB-flavonoid inhibited 15-PGDH activity in a concentration-dependent manner, with a significant reduction in 15-PGDH activity at 7.0 μg/mL. The release of PGE2 also increased with higher concentrations of QMB-flavonoid, showing a marked rise from 1,700 ± 51.3 to 2,500 ± 99.60 pg/mL when the concentration was between 5.0 and 70 μg/mL. Gene expression analysis revealed that QMB-flavonoid treatment resulted in decreased expression of 15-PGDH, COX-1, and PGT, whereas the expression of MRP4 was significantly increased. Additionally, QMB-flavonoid upregulated the expression of several genes related to cell proliferation, including LMO2, RUNX1, SCL, KDR, and MYB, with KDR showing a remarkable 5.1-fold increase. In terms of collagen synthesis, QMB-flavonoid promoted collagen production in a concentration-dependent manner, particularly at 5.0 µg/mL, where it increased collagen synthesis by 51.4 ± 2.34% compared to the control group. Moreover, the wound healing effects of QMB-flavonoids were evaluated and showed significant improvement in cell growth and wound closure. The QMB-flavonoid group demonstrated a 199.3 ± 9.95 % cell growth rate compared to the control, and by day 15, the wounds in the QMB-flavonoid-treated group were almost fully healed, with better tissue regeneration and a thinner epidermis compared to the blank group. These findings highlight the promising wound healing properties of QMB-flavonoid, suggesting its potential use in skin regeneration therapies. These results suggest that QMB-flavonoid has a positive effect on wound healing, showing promising potential for skin regeneration therapy. However, further research is needed to evaluate the long-term safety and efficacy of QMB-flavonoid and confirm their effects on various skin diseases.