1. Introduction

Vibrations, alongside noise, have been extensively studied as critical factors affecting the health of self-propelled agricultural machinery operators. While noise issues have largely been mitigated through the implementation of well-insulated cabs, the same progress has not been achieved with vibrations.

In wheeled tractors, suspension-equipped seats have been the standard for decades and remain the primary component, along with the tyres, for reducing vibrational input to the operator [

1]. However, prolonged exposure to high levels of vibration has been shown to have adverse effects on the health of tractor drivers. It is well-established that tractor drivers experience significant whole-body vibration (WBV) during agricultural activities [

2]. Notably, only more recent tractor models integrate advanced suspension systems, combining seat, cab and front axle suspensions. For older tractors, seat suspension remains the predominant, and often the sole, method for improving operator comfort [

3].

Seat suspension systems may be mechanical, pneumatic, or semi-active in design [

4]. These systems typically incorporate stiffness adjustments to accommodate driver mass, usually ranging from 50 to 130–140 kg. However, such suspension systems do not always provide adequate vibration damping, particularly during demanding tasks such as soil tillage or high-speed transportation on uneven terrain [

5,

6,

7,

8]. To address this limitation, various theoretical models have been developed to enhance the design and functionality of seat suspension systems [

9], as well as cab [

10] and front axle suspension [

11].

Several other factors can influence the transmissibility of vibrations to tractor drivers, including posture (notably neck and lower back alignment) [

12,

13] and the material properties and thickness of the seat cushion [

14].

Nevertheless, proper suspension adjustment, regardless of its type, remains the most critical factor in ensuring optimal vibration attenuation. While suspension can dampen vibrations along the horizontal axes (longitudinal X and transverse Y), they are primarily designed to minimize transmission along the vertical axis Z. Vertical vibrations pose the greatest risk to the spinal column, making them a key contributor to occupational diseases linked to WBV.

Unfortunately, in practice, tractor’ drivers often neglect or overlook the proper adjustment of seat suspension stiffness. This criticism often reduces or entirely negates its benefits. This oversight highlights the need for greater awareness and continued innovation in suspension systems, to better protect operator’s health.

This paper aims to investigate the potential increase in vibration levels experienced by a driver on two tractors travelling on uneven terrain when their seat suspension systems are improperly adjusted.

2. Materials and Methods

The study compared the vibrational levels experienced at the driver’s seat of two mid-range tractors with similar power and technical specifications, while travelling on an inter-farm road. The tests were conducted at the Cascina Baciocca farm in Cornaredo, Milan, Italy, on a straight, 220 m section of a rural unpaved road with a consistent surface.

The road profile was relatively well-maintained and dry, characterized by two compacted tracks on either side, formed by frequent agricultural machinery traffic. The top soil layer (up to 10 cm depth) had a low moisture content (less than 12%) and exhibited moderate unevenness, with elevation differences typically not exceeding ±50 mm. However, some areas contained deeper depressions, with elevation differences reaching ±75 mm. The remaining parts of the road surface were covered in grass, with a maximum height of 250 mm.

Each test condition involved driving the same road section in both directions, to account for variations in vibration caused by the uneven road surface encountered in each direction.

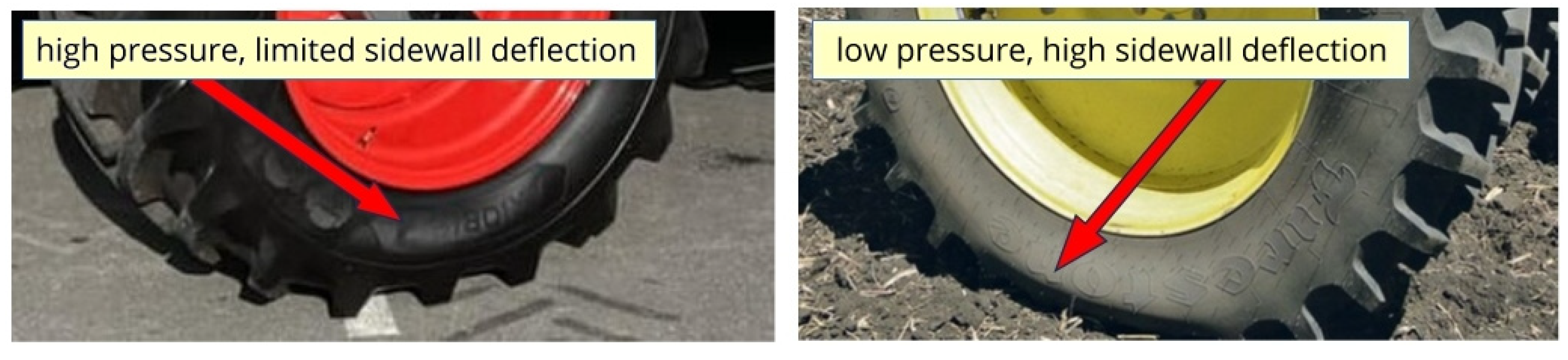

Vibration data were collected while both the tractor maintained a steady speed, excluding brief acceleration and deceleration phases at the beginning and end of each run. The tests were conducted at three different speeds (5, 10 and 15 km/h) and with two tyre inflation pressure settings: normal pressure (170 kPa at the front and 150 kPa at the rear) and very low pressure (60 kPa for both front and rear), to take into account the different damping action of tyres. To keep the tests consistent, the tractors engine speed was held steady during all tests, by selecting the appropriate gear ratios.

Both seat suspension systems were initially configured to the reference stiffness setting, followed by incorrect adjustments, to the maximum and minimum stiffness levels respectively. In more detail, the tests were performed with a driver with a body mass of 84 kg, with the seat suspensions initially settled exactly to his reference value, and subsequently adjusted to extreme, non-calibrated settings, representing the maximum (130 kg) and minimum (50 kg) achievable stiffness configurations (

Table 1).

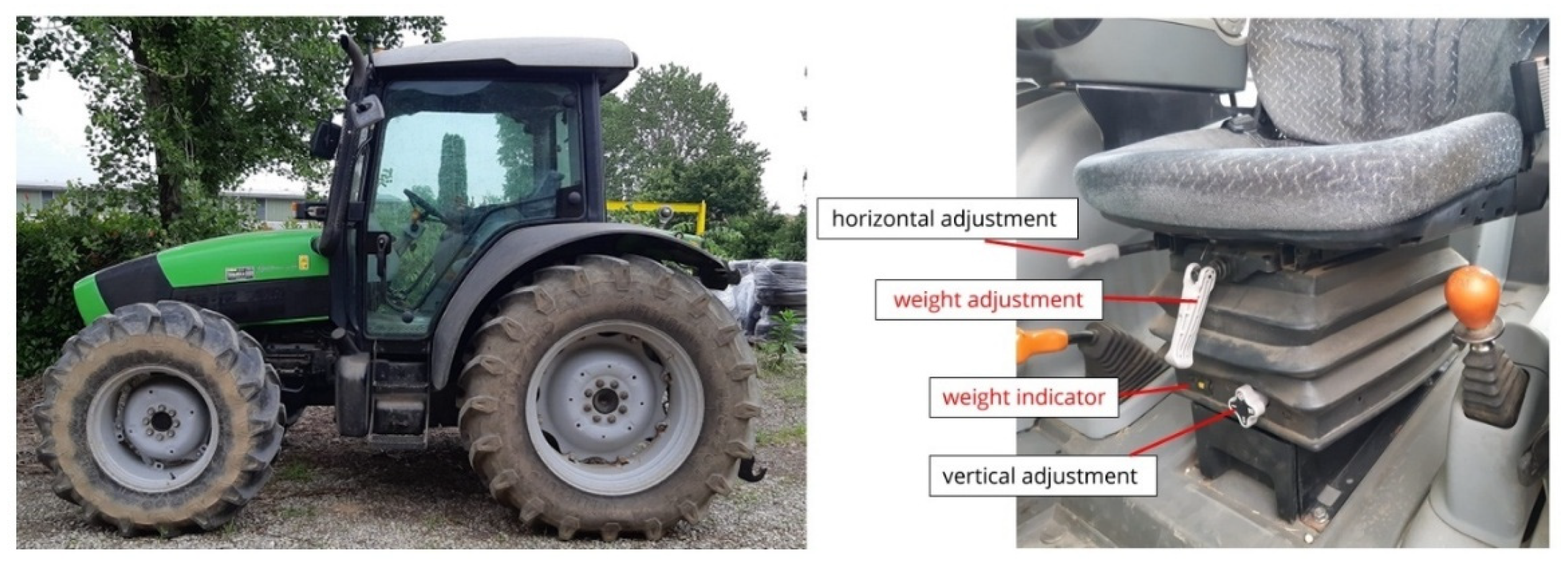

The comparison of seat suspension systems performance was conducted using two tractors: a Deutz-Fahr Agrofarm 430 (in the following, named “tractor A”) and a New Holland T5.90 S (in the following, named “tractor B”).

The Deutz-Fahr Agrofarm 430, a 4WD mid-range model with an engine output of 80 kW (109 CV), was manufactured by Same Deutz-Fahr (Treviglio, Italy). It is equipped with 420/70R24 130 A8 front tyres and 480/70R34 134 A8 rear tyres. The tractor had a total unballasted mass of 4480 kg, with 1720 kg (38.4 %) on the front axle and 2760 kg (61.6 %) on the rear axle.

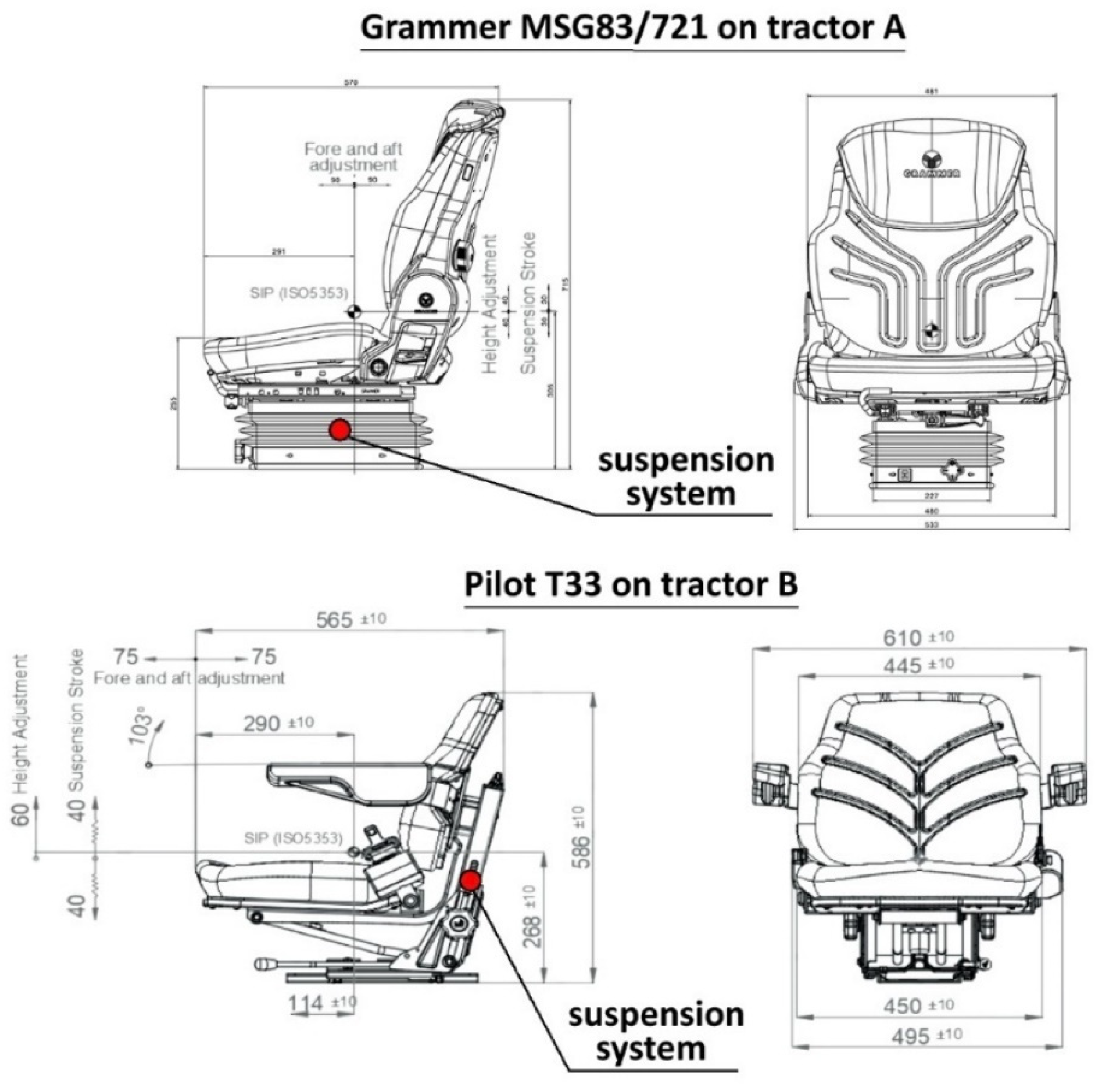

The seat installed on this tractor was a Grammer MSG 83/721, featuring a mechanical suspension system, manufactured by Grammer (Waregem, Belgium) (

Figure 1).

The second tractor used in the study was a 4WD mid-range model with an engine output of 66 kW (90 CV), manufactured by New Holland (Turin, Italy), in the following, named “tractor B”. It was equipped with 250/85R28 112 A8 front tyres and 320/85R38 143 D rear tyres. The tractor had a total unballasted mass of 3900 kg, with 1545 kg (39.6 %) on the front axle and 2365 kg (61.4 %) on the rear axle. The seat installed on this tractor was a mechanical suspension model T33, manufactured by Pilot (Bursa, Turkey) (

Figure 2).

Main specifications of both seats are provided in

Table 2, while the main dimensions and adjustments are shown in

Figure 3.

Vibration levels were evaluated in accordance with the most recent version of the ISO 2631-4 standard, “Mechanical Vibration and Shock – Evaluation of Human Exposure to Whole-Body Vibration – Part 4: Guidelines for the Evaluation of the Effects of Vibration and Rotational Motion on the Comfort of Passengers and Crew in Fixed Guideway Transport Systems”. Relevance was given to vibrations along the Z-axis (vertical), as these have the most significant impact on the driver’s spinal column. Additionally, the study incorporated broader assessments based on operator exposure guidelines outlined in Directive 2002/44/EC and Italian Legislative Decree 81/08 (commonly referred to as the “Consolidated Occupational Health and Safety Act”).

Vibration levels were measured using a 4-channel portable analyzer, model HD 2030, manufactured by Senseca-Deltaohm (Caselle di Selvazzano - PD, Italy). The analyzer was paired with a tri-axial accelerometer, model 5313M2, manufactured by Ditran (Chatsworth, USA). To ensure accurate data acquisition, the accelerometer was inserted within a rubber pad and located on the seat cushion (

Figure 4).

For each test run, the overall equivalent continuous acceleration level (Leq, m/s²) of the vibrations was recorded. The initial analysis, described in this paper, concentrated specifically on vertical vibrations (Z-axis), given the predominant damping effect of typical seat suspension systems in this direction.

Both suspension systems are equipped with a spring-damper assembly, integrated into a mechanical supporting structure. More in detail, the Grammer MSG 83/721 seat installed on tractor A features a scissor suspension system, located beneath the seat cushion. In contrast, the Bursa T33 seat mounted on tractor B is equipped with an articulated quadrilateral suspension system, cantilevered behind the backrest.

Regardless of other structural differences, while both systems serve the same damping function, the design of these suspension types may exhibit different performance levels in response to the same vibrational input. This observation prompted further comparative investigation, considering that the two tractors, although similar in structure and overall mass, were equipped with tyres of significantly different cross-sections, a technical feature that undoubtedly affects the vehicle’s mechanical response to terrain-induced stress.

3. Results and Discussion

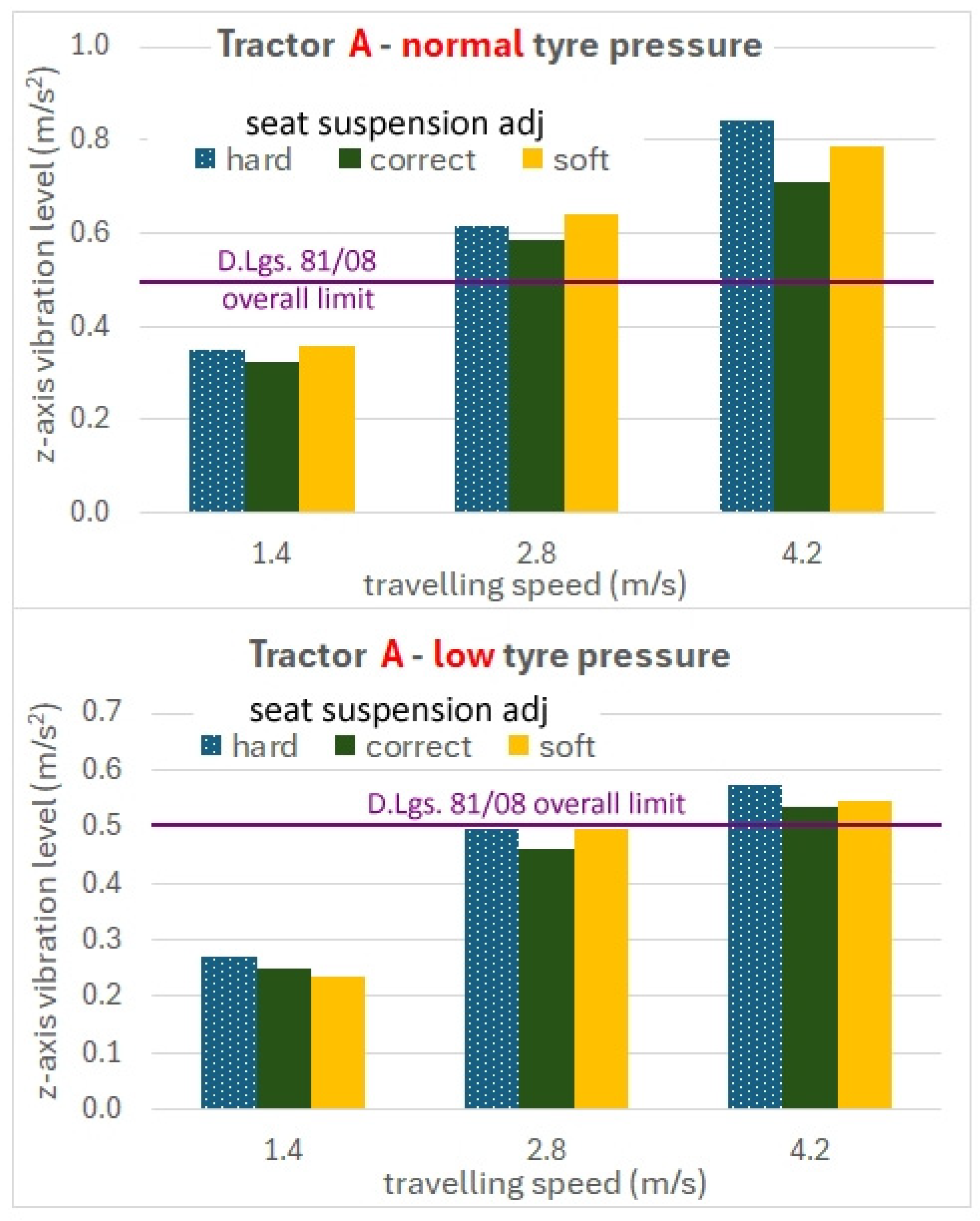

For tractor A, in comparison to the correct suspension setting, adjustments to both the softest and hardest stiffness settings consistently resulted in higher levels, typically ranging between about 3% and 18%, with only one exception observed (

Figure 5).

Tractor A was equipped with radial tyres of wide section for this model; consequently, the condition of low inflation pressure notably improved the overall situation at all speeds, confirming that in this operating condition tyres play a primary role in reducing vibration transmission. This effect is particularly pronounced when the tyre wall elasticity is enhanced by very low-pressure values (60 kPa) (

Figure 6).

In any case, considering only vibrations along the vertical axis, the limit established by D.Lgs. 81/08 is already exceeded at speeds of 10 and 15 km/h with standard tyre pressure (and sometime also at low pressure), regardless of suspension stiffness settings. This suggests that, as expected, travel speed significantly affects vibrational input, even at values that are almost always exceeded during typical road transfers within the farm.

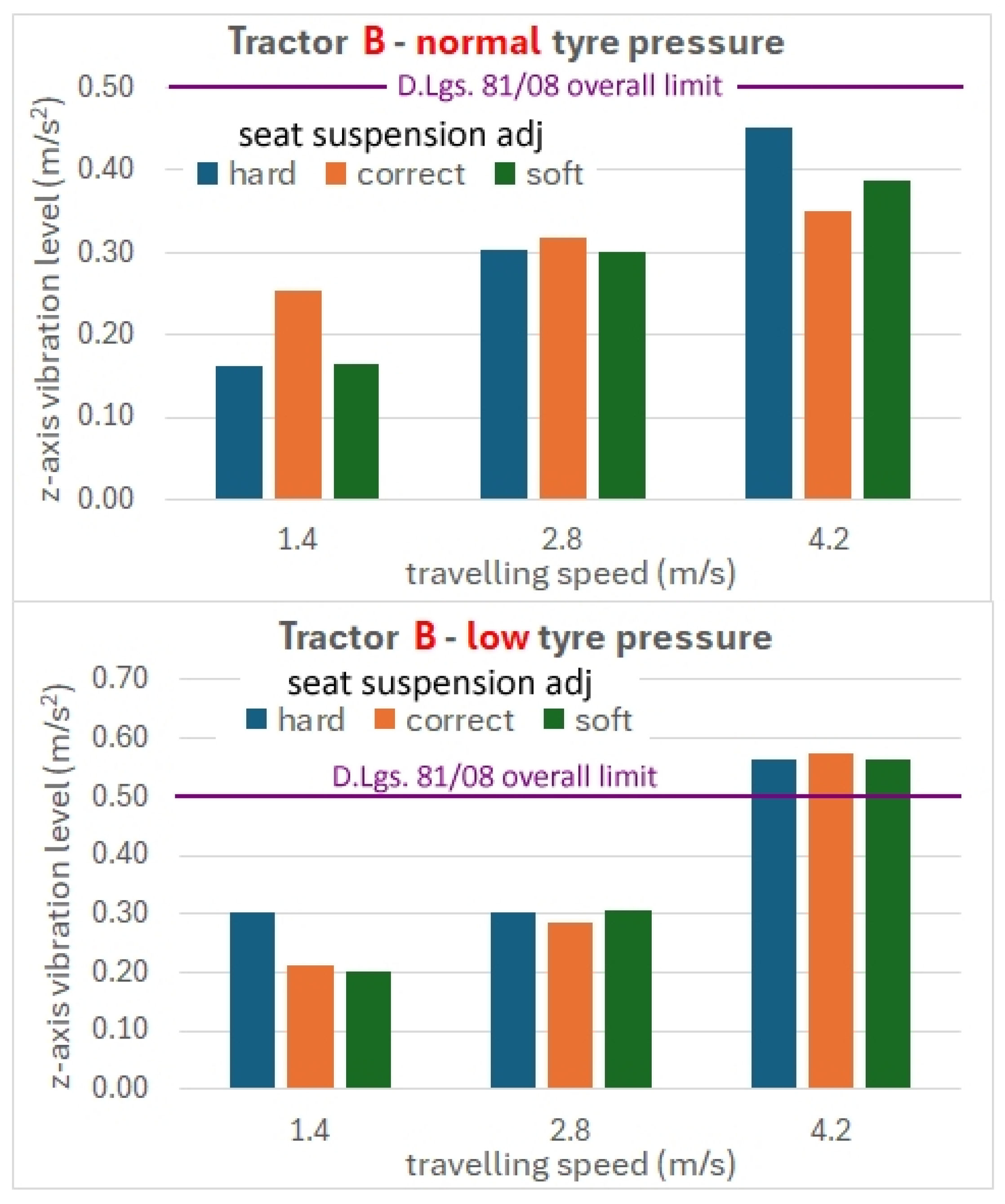

The similar analysis for tractor B revealed different results (

Figure 7). Specifically, at normal tyre pressure (

Table 5) and low speeds (5 and 10 km/h), proper adjustment of the seat suspension does not resulted in a reduction in vibration levels in comparison with the softest and the hardest. However, it is worth noting that vertical-axis vibration levels remain always low, below the threshold established by D. Lgs 81/08. This is likely because the oscillatory input is minimal and does not effectively trigger the damping action of the seat suspension.

Conversely, at a speed of 15 km/h, improper seat suspension adjustment, whether excessively soft or overly stiff, leads to a significant increase in vibration disturbance. Again, given that typical cruise speeds during transfer, including on farm roads, are progressively increasing and currently reach or exceed 20 km/h, this finding underscores the importance of proper seat suspension adjustment.

In contrast, with all the tyres of tractor B inflated to a very low pressure (60 kPa), improper suspension adjustment exacerbates the situation, particularly at low speeds (

Table 6), where vibration levels increase significantly by approximately 43%. However, at higher speeds, the differences are negligible, indicating that the tyres absorb most of the terrain irregularities, while the seat suspension has a much smaller effect. Tractor B was equipped with narrow section radial tyres, which inherently have a smaller internal air volume in comparison with wide tyres. As a result, at low pressure in respect to the normal pressure, their beneficial effect is amplified, while at higher speeds, the effect diminishes, likely due to the higher intensity of the vibrational input.

4. Conclusions

The results obtained present a contrasting scenario. For Tractor A, equipped with wide tyres, improper adjustment of the seat mechanical suspension typically results in an increase in vibration levels. Conversely, for Tractor B, particularly when its narrow tyres are inflated to low pressure, vibration levels often do not increase and may even decrease under conditions of both maximum and minimum suspension stiffness. This is likely attributable to the reduced internal air volume of the tyres, where the elasticity of the sidewalls, and their associated damping effect, effectively mitigates vibrations, thereby lessening or substantially reducing the impact of incorrect suspension settings.

Nevertheless, it is unequivocal that higher travel speeds consistently exacerbate the disturbances perceived by the operator. Notably, even when considering only vertical-axis (z) vibration values, when travelling at the maximum test speed of 15 km/h (4.2 m/s) the threshold established by D.Lgs 81/08 was frequently exceeded. This is particularly concerning, as overall vibration levels, that are including those along the longitudinal and transverse axes, are inherently higher. Furthermore, actual travel speeds on inter-farm roads increasingly surpass those examined in this study.

To achieve a comprehensive assessment of vibration risk levels, additional data collection campaigns are necessary in future investigations. This should include measurements taken during operations involving implements attached to the tractor, whether mounted on the three-point linkage or towed via the hitch. Emphasis should be placed on high-risk activities, such as deep soil tillage, owing to the impacts of working tools on the soil, and haymaking, given the typically high operating speeds on irregular field surfaces.

Finally, to thoroughly assess the adverse effects of improper seat suspension adjustment on the operator’s exposure to vibrations, it will be essential to properly quantify the time allocated to each operation. This will allow for the calculation of a comprehensive weighted average, which can then be compared against the exposure limits established by Directive 2002/44/EC at the EU level and implemented in Italy through Legislative Decree 81/08.

Author Contributions

conceptualization, D.Pessina and L.E.Galli.; methodology, D. Pessina.; validation, D.Pessina and L.E.Galli.; formal analysis, D.Pessina.; investigation, D.Pessina and L.E.Galli.; resources, D. Pessina; data curation, L.E. Galli; writing—original draft preparation, L.E.Galli; writing—review and editing, D.Pessina, supervision, D.Pessina. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Funding

this research received no external funding

Data Availability Statement

not applicable

Acknowledgments

the Authors extend their sincere thanks to Mr. Marco Gibin for his effective support during the execution of the tests

Conflicts of Interest

the authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- Deboli, R.; Calvo, A.; Preti, C. Whole-body vibration: Measurement of horizontal and vertical transmissibility of an agricultural tractor seat. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2017, 58, 69-78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ergon.2017.02.002. [CrossRef]

- Scarlett, A.J.; Price, J.S.; Stayner, R.M. Whole-body vibration: Evaluation of emission and exposure levels arising from agricultural tractors. J. Terramech. 2007, 44, 65-73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jterra.2006.01.006. [CrossRef]

- Ermatova, D.I.; Matmurodov, F.M.; Imomov, Sh.J.; Aynakulov, Sh.A. Measure for extinguishing vertical vibrations on the seat of a wheel tractor when moving along a random profile of the path. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 868, 012003. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/868/1/012003. [CrossRef]

- Giordano, D.M.; Facchinetti, D.; Pessina, D. Comfort efficiency of the front axle suspension in off-road operations of a medium-powered agricultural tractor. Contemp. Eng. Sci. 2015, 8, 1311–1325. http://dx.doi.org/10.12988/ces.2015.56186. [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Deng, J.; Yue, R.; Han, G.; Zhang, J.; Ma, M.; Zhong, X. Design and verification of a seat suspension with variable stiffness and damping. Smart Mater. Struct. 2019, 28, 065015. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-665X/ab18d4. [CrossRef]

- Sorainen, E.; Penttinen, J.; Kallio, M.; Rytkönen, E.; Taattola, K. Whole-body vibration of tractor drivers during harrowing. Am. Ind. Hyg. Assoc. J. 1998, 59, 642-644. https://doi.org/10.1080/15428119891010820. [CrossRef]

- Servadio, P.; Belfiore, N.P. Influence of tyres characteristics and travelling speed on ride vibrations of a modern medium powered tractor. CIGR J. 2013, 15, 4. https://cigrjournal.org/index.php/Ejounral/article/view/2543.

- Servadio, P.; Marsili, A.; Belfiore, N.P. Analysis of driving seat vibrations in high forward speed tractors. Biosyst. Eng. 2007, 97, 171-180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2007.03.004. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Samuel, S.; Singh, H.; Kumar, Y.; Prakash, C. Evaluation and analysis of whole-body vibration exposure during soil tillage operation. Safety 2021, 7, 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety7030061. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wei, W.; Chen, X.; Xu, L.; Cao, Y. Vibration performance analysis and multi-objective optimization design of a tractor scissor seat suspension system. Agriculture 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture13010048. [CrossRef]

- Pobedin, V.; Dolotov, A.A.; Shekhovtsov, V.V. Decrease of the vibration load level on the tractor operator working place by means of using of vibrations dynamic dampers in the cabin suspension. Procedia Eng. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2016.07.136. [CrossRef]

- Pope, M.H.; Hansson, T.H. Vibration of the spine and low back pain. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1992, 279, 49-59. PMID: 1534724. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1534724. [PubMed]

- Kim, J.H.; Dennerlein, J.T.; Johnson, P.W. The effect of a multi-axis suspension on whole body vibration exposures and physical stress in the neck and low back in agricultural tractor applications. Appl. Ergon. 2018, 68, 80-89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2017.10.021. [CrossRef]

- Adam, S.A.; Abdul Jalil, N.A.; Rezali, K.A.; Ng, Y.G. The effect of posture and vibration magnitude on the vertical vibration transmissibility of tractor suspension system. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ergon.2020.103014. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).