Submitted:

17 April 2025

Posted:

19 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Review of the Literature

2.1. Social Cognitive Theory of Self-regulation and Cybernetics Theory

2.2. GenAI Within Business Customer Experience

2.3. Gaps and Shortcomings of GenAI in Business Customer Experience

2.4. Practices in Self-Regulation of GenAI

3. Methodology

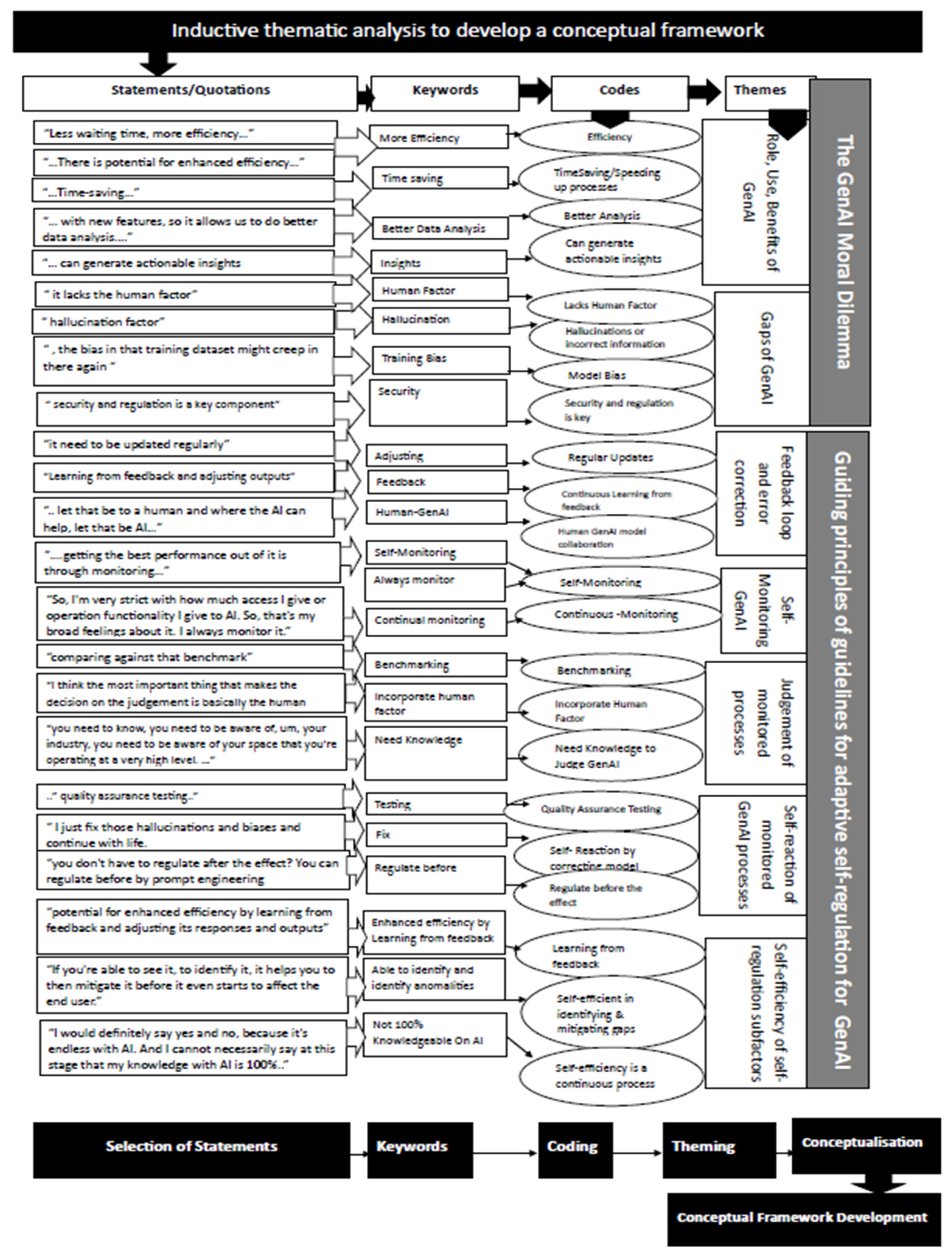

4. Findings of the Study

4.1. Role, Use, and Benefits of GenAI

4.2. Gaps and Shortcomings of GenAI

4.3. Building Blocks to Develop Adaptive Self-Regulation Guidelines

5. Discussion

5.1. Guidelines for Adaptive Self-Regulation Guidelines

- Principle of clarity. The GenAI as a key driver of efficiency, innovation, and competitive advantage (Woolley, 2024). Additionally, GenAI improves efficiencies on transactions initiated by customers, which could improve customer satisfaction (Melise et al., 2024). Strategically leveraging GenAI can also position businesses for a competitive advantage (Oanh, 2024). One the fact that the efficiencies was of GenAI models were capable of responding to customer questions in real-time, and also providing personalised business customer experiences and more (Moura et al., 2021). The predictive capabilities of GenAI models in recalling customer patterns, purchase history, and trends, customers also enjoy the benefits of saving time in decision making (Tiutiu & Dabija, 2023). Although the customer experiences are enhanced from personalised or customised customer experiences, other nefarious consequences including ethical and data privacy side effects exist (Singh et al., 2024). GenAI offers revolutionary strategic business potential by providing analysis that has the potential of boosting customer experiences and sales performance through the continuous monitoring of trends, customer spending patterns, and customised sales and services (Yusuff, 2024). GenAI models enable the analysis of sales performance in the backend, thereby facilitating further enhancements to business customer experiences (Kumar et al., 2024). Research participants were of the opinion that GenAI models have the ability to assist businesses in their decision-making through their objective and readily available insights (İşgüzar et al., 2024). The principle of clarity states that AI systems should operate in a way that is transparent, understandable, and honest about their identity, purpose, and outputs, thus enabling users to make informed, responsible decisions when interacting with or relying on AI.

- Principle of accuracy and fairness-conscious AI design. Bias is unavoidable, and that means that it becomes a gap that needs to be managed by the business and the customers as well. The findings accentuate the importance of acknowledging and addressing the potential gaps and shortcomings associated with GenAI adoption, particularly in business customer experience contexts (Lecocq et al., 2024). Noble (2018) posit that search engine algorithms have been criticised for displaying racially skewed image results when searching for terms like “woman”, highlighting the need for greater diversity and inclusivity in AI design (Noble, 2018). Biases also emerge when a GenAI model is built for Western cultures, thus creating an inherent bias toward their preferences (Nyaaba et al., 2024). Additionally, the findings highlighted that one of the most common gaps is hallucinations and outdated results (Akolkar, 2024; Latifi, 2024). This concern was also consistently raised by a majority of participants, highlighting the issue of hallucinations and related inconsistencies as a significant and recurring theme affecting business customer experiences (Williamson & Prybutok, 2024). As such, there is a need for a principle of accuracy and fairness-conscious AI design. This principle must emphasise algorithmic fairness and bias mitigation and active awareness of known risks, covering bias and hallucinations. The intention is to make sure that users and the public understand what AI cannot do well. When roles, uses, and benefits are clear, it is easier to trace errors and hallucinations, thus advancing the interlinkage between the principle of clarity and the principle of accuracy and fairness-conscious AI design.

- Principle of security and data protection. In particular, the use of GenAI raises critical issues regarding sensitive data privacy, malicious input, and other ethical shortcomings, necessitating a nuanced consideration of its implications (Golda et al., 2024). As identified by the research participants, there are several security risks that are possible, including the leaking of the customers personal information shared with the GenAI models and also the sharing of sensitive business information by the GenAI with the world, so both the business and the customers are at risk (Sekine, 2025). Businesses that collect personal information face these sort of vulnerabilities and risks in the adoption of GenAI models for their business customer experience (Hinds et al., 2020). Potentially of all the gaps the issue to do with security is not only a business concern but a human rights issue, which has also been a concern highlighted with other technological advancements such as social media sites like Facebook (Meta) (Sieber, 2019). The principle of security and data protection promotes that AI systems must be designed, developed, and deployed in a way that safeguards personal data, ensures system integrity, and prevents unauthorised access or misuse of information throughout the AI lifecycle. This principle is essential for self-regulation, where organisations take proactive responsibility for ethical use of AI without needing external enforcement in every instance.

- Principle of empathy simulation (with limits). The findings show a desire for AI to have warm and empathetic aspects that human beings possess. These limitations underscore the need for improved user education and interface design to facilitate effective human-AI collaboration (Katragadda, 2024). This principle balances emotional intelligence and ethical restraint, helping AI show care without crossing the line into false intimacy or misleading affective behaviour. AI systems designed to simulate empathy must do so responsibly, by acknowledging emotional context, responding in a supportive and respectful tone, while also clearly signalling their non-human nature to avoid emotional manipulation or deception.

- Principle of self-monitoring.

- The participants identified the crucial role that human oversight plays as a founding principle that initiates the process of self-regulation, and they also recommended the use of self-monitoring systems. These systems can be machine systems where the self-monitoring subfunction is fulfilled (Varsha, 2023). Several conclusions can be drawn from the findings in relation to the role that GenAI self-monitoring plays in the self-regulation of these models in the business customer experience. Self-regulation, in this context, involves the implementation of internal controls and guidelines that govern the control, design, and the deployment of GenAI models in business customer experiences. Businesses cannot afford to lose control of the output and the function of the GenAI customer experiences, as was the case with the Air Canada, where a customer was given a wrongful discount that the business had to pay including legal costs (Cerullo, 2024). A substantial majority of research participants converged in their opinions that self-monitoring plays an active self-regulatory role in GenAI business customer experiences (Holmström & Carroll, 2024). The former highlights the importance of self-monitoring, which enables businesses to maintain a state of control, oversight, awareness, and connectivity with the customer experiences created by their GenAI models (Gupta et al., 2024). Furthermore, oversight is crucial, to protect customers’ privacy through monitoring and staying informed about the data collection and dissemination of the GenAI model, thus promoting transparency (Chavali et al., 2024).

- Principle of judgement of monitored process.

- Judgement in this research refers to judging whether the above-mentioned self-monitored GenAI performances of the model is beneficial or causing gaps in the business customer experience. This is in line with the first two research objectives. Additionally, it was important for the participants to exercise judgement in identifying the benefits of GenAI in business customer experience in order to create a better understanding of the moral dilemma. This supports the role of adaptive self-regulation by ensuring that there are ongoing assessments and discernment of the GenAI customer experience performances. Again, judgement is a subset of personal standards and performance that is evaluated for self-regulation (Bandura, 1986). Some of the discussions of the codes, identified under the theme of judgement, are that judgement is enabled by integrating human intervention, benchmarking and having knowledge.

- Principle of the self-reaction of monitored process

- The principle of self-reaction involves the human agents once they have made their judgements and acknowledged the existence of a gap, they are now participating in undertaking interventions to correct the GenAI models. Participants described that in the event of a wrong result, they were capable of countering that response with the correct response and essentially amending the GenAI model. This plays a role in continuously improving GenAI models. The self-reactive role here is instantaneous as opposed to logging a ticket and awaiting lengthy channels to correct the model. Correcting the model is simply typing back to the GenAI that it has made an error and what the correct information is. However, there is a risk that the model can be amended from the correct information to be trained on incorrect information.

- Principle of self-efficiency of self-regulation.

- Self-efficacy is central to the entire self-regulation process and is the malleable belief that is formed on its cognitive ability to execute the self-regulation function (Stajkovic & Stajkovic, 2019). This belief also partially influences how one views their own abilities in the other subfunction self-monitoring, judgement, and self-reaction. It is so important that there be high levels of self-efficacy as it increases the belief of attaining self-regulation goals (Bandura, 1986). Furthermore, the results further corroborated Bandura’s sentiments that the higher the beliefs one has in their self-regulatory capabilities the greater is the commitment or mastery to their goals (Bandura, 1986; Nabavi & Bijandi, 2012). These sentiments of the integral role self-efficacy in influencing self-regulation underscore the need for enhanced user education to improve self-efficacy levels to facilitate enhanced self-regulation guidelines of the GenAI model (Katragadda, 2024).

5.2. Implications for Management

5.3. Implications for Policymakers

5.3. Theoretical Contribution of the Study

5.4. Limitations and Future Studies

6. Conclusions

Appendix A. Interview Guide

- What is your background including your technological background and how many years of experience do you have in technology and also in GenAI for customer experiences?

- In your own view, what are the current benefits of using GenAI in business customer experiences in South Africa? Explain.

- In your own view, what are the gaps or shortcomings of the use of business customer experience GenAI applications? Explain

- In view of the identified gaps, what do you suggest can be done in terms of GenAI self-regulation?

- In your own opinion, advise the use of GenAI in coding and have you also made use of it? For example, ask GenAI to write code for an application or load code for correction in GenAI tools, such as chatbots. Explain

- Have you developed any GenAI business customer application that was self-regulated adaptively? Explain.

- What is your opinion of adaptive self-regulation of GenAI? Explain.

- In your view, have you mastered the ability to monitor GenAI processes? In other words, are you confident in your ability to keep a close eye on any GenAI business customer experience application and immediately pick up irregularities that contradict regulation measures, and can you immediately address or mitigate any risks effectively?

- How good is your judgement in terms of classifying whether an incident should be regulated especially where it concerns GenAI processes, irregularities, such as biases, inconsistencies, copyright infringements, security breaches and any other undesirable effects?

- Are you self-monitoring the performance of GenAI applications that you interact with through continuously learning on GenAI to stay aware of any new development or threats and engaging in new materials?

- Are you able to take steps that show initiative to self-regulate the use of GenAI effectively?

- Any other comments related to the subject matter under discussion?

References

- Abdullah, S.M. Social Cognitive Theory : A Bandura Thought Review published in 1982-2012. Psikodimensia 2019, 18, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, S.M. Social Cognitive Theory : A Bandura Thought Review published in 1982-2012. Psikodimensia 2019, 18, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin Akhtar, Z. Generative artificial intelligence (GAI): From large language models (LLMs) to multimodal applications towards fine tuning of models, implications, investigations. Comput. Artif. Intell. 2024, 1498–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akolkar, H. R. (2024). Examining the Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Customer Satisfaction in the Banking Sector: A Quantitative Analysis [D.B.A., Westcliff University]. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2937182457/abstract/986BB7E52F64062PQ/5.

- Ameen, N.; Tarhini, A.; Reppel, A.; Anand, A. Customer experiences in the age of artificial intelligence. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 114, 106548–106548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archibald, M.M.; Ambagtsheer, R.C.; Casey, M.G.; Lawless, M. Using Zoom Videoconferencing for Qualitative Data Collection: Perceptions and Experiences of Researchers and Participants. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2019, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory (pp. xiii, 617). Prentice-Hall, Inc.

- Banh, L.; Strobel, G. Generative artificial intelligence. Electron. Mark. 2023, 33, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolotskikh, M. , Dorokhova, M., & Serov, I. (2024). Generative AI in the BRICS+ Countries: Trends and Outlook. https://www.yakovpartners.com/upload/iblock/a35/ft76bknzh09znv71qpvyr9k7q7c3wsxc/210125_generative_AI_BRICS_ENG.pdf.

- Breidbach, C.F. Responsible algorithmic decision-making. Organ. Dyn. 2024, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzozowska, M.; Kolasińska-Morawska, K.; Sułkowski, Ł.; Morawski, P. Artificial-intelligence-powered customer service management in the logistics industry. Entrep. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2023, 11, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capgemini. (2023). Imagining A new era of customer experience with Generative AI. https://www.capgeminicom/us-en/insights/research-library/imagining-a-new-era-of-customer-experience-with-generative-ai/.

- Capraro, V.; Lentsch, A.; Acemoglu, D.; Akgun, S.; Akhmedova, A.; Bilancini, E.; Bonnefon, J.-F.; Brañas-Garza, P.; Butera, L.; Douglas, K.M.; et al. The impact of generative artificial intelligence on socioeconomic inequalities and policy making. PNAS Nexus 2023, 3, pgae191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S.; Scheier, M.F. On the Self-Regulation of Behavior: Principles of Feedback Control; Cambridge University Press: 1998; pp. 10–28. [CrossRef]

- Cerullo, M. (2024, February 19). Air Canada chatbot costs airline discount it wrongly offered customer—CBS News. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/aircanada-chatbot-discount-customer/.

- Chadha, K.S. Bias and Fairness in Artificial Intelligence: Methods and Mitigation Strategies. Int. J. Res. Publ. Semin. 2024, 15, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavali, D. , Baburajan, B., Kumar, V., & Katari, S. C. (2024). Regulating Artificial Intelligence Developments and Challenges. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 02, 1250–1261. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10898480. [CrossRef]

- Dana, N. , & Zwiegelaar, J. (2023). The implementation of AI Technology on banks interactions creating differentiated customer offerings. International Conference on Information Systems 2023 Special Interest Group on Big Data Proceedings. https://aisel.aisnet.org/sigbd2023/1.

- Abu Daqar, M.A.; Smoudy, A.K.A. The role of artificial intelligence on enhancing customer experience. Int. Rev. Manag. Mark. 2019, 9, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espejo, R.; Reyes, A. On Control and Communication: Self-regulation and Coordination of Actions; Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2011; pp. 21–32. [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, E. Fairness and Bias in Artificial Intelligence: A Brief Survey of Sources, Impacts, and Mitigation Strategies. Sci 2024, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrario, B.; Stantcheva, S. Eliciting People’s First-Order Concerns: Text Analysis of Open-Ended Survey Questions. AEA Pap. Proc. 2022, 112, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, C.; Demsar, V.; Sands, S.; Restrepo, M.; Campbell, C. The paradoxes of generative AI-enabled customer service: A guide for managers. Bus. Horizons 2024, 67, 549–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feuerriegel, S.; Hartmann, J.; Janiesch, C.; Zschech, P. Generative AI. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2024, 66, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funa, A.A.; Gabay, R.A.E. Policy guidelines and recommendations on AI use in teaching and learning: A meta-synthesis study. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2025, 11, 101221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gans, J.S. (2018). Self-regulating Artificial General Intelligence. http://www.nber.org/papers/w24352.

- Golda, A.; Mekonen, K.; Pandey, A.; Singh, A.; Hassija, V.; Chamola, V.; Sikdar, B. Privacy and Security Concerns in Generative AI: A Comprehensive Survey. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 48126–48144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groumpos, P.P. The Cybernetic Artificial Intelligence (CAI): A new scientific field for modelling and controlling Complex Dynamical Systems. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2024, 58, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guetterman, T. C. (2015). Descriptions of Sampling Practices Within Five Approaches to Qualitative Research in Education and the Health Sciences. http://www.qualitative-research.net/.

- Gupta, P.; Ding, B.; Guan, C.; Ding, D. Generative AI: A systematic review using topic modelling techniques. Data Inf. Manag. 2024, 8, 100066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harinie, L.T.; Sudiro, A.; Rahayu, M.; Fatchan, A. Study of the Bandura’s Social Cognitive Learning Theory for the Entrepreneurship Learning Process. Soc. Sci. 2017, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinds, J.; Williams, E.J.; Joinson, A.N. “It wouldn't happen to me”: Privacy concerns and perspectives following the Cambridge Analytica scandal. Int. J. Human-Computer Stud. 2020, 143, 102498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, D. (2021). Business Data Ethics: Emerging Trends in the Governance of Advanced Analytics and AI Final Report. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/351046077_Business_Data_Ethics_Emerging_Trends_in_the_Governance_of_Advanced_Analytics_and_AI.

- Holmström, J.; Carroll, N. How organizations can innovate with generative AI. Bus. Horizons 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isguzar, S.; Fendoglu, E.; SimSek, A.I. Innovative Applications in Businesses: An Evaluation on Generative Artificial Intelligence. www.amfiteatrueconomic.ro 2024, 26, 511–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawarkar, R. K. (2022). The consequences of algorithmic decision making. https://www.abacademies.org/articles/the-consequences-of-algorithmic-decisionmaking.pdf.

- Katragadda, V. (2024). Leveraging Intent Detection and Generative AI for Enhanced Customer Support. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/381767053_Leveraging_Intent_Detection_and_Generative_AI_for_Enhanced_Customer_Support.

- Kaushik, P.; Garg, V.; Priya, A.; Kant, S. Financial Fraud and Manipulation: The Malicious Use of Deepfakes in Business; 2024; pp. 173–196. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. Investigating the effects of generative-ai responses on user experience after ai hallucination. In Proceedings of the MBP 2024 Tokyo International Conference on Management & Business Practices, 18-19 January 2024; pp. 92–101. [Google Scholar]

- Kirova, V.D.; Ku, C.S.; Laracy, J.R.; Marlowe, T.J. The Ethics of Artificial Intelligence in the Era of Generative AI. J. Syst. Cybern. Inform. 2023, 21, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kshetri, N.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Davenport, T.H.; Panteli, N. Generative artificial intelligence in marketing: Applications, opportunities, challenges, and research agenda. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2023, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Ashraf, A.R.; Nadeem, W. AI-powered marketing: What, where, and how? Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2024, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latifi, H. Challenges of Using Artificial Intelligence in the Process of Shi’i Ijtihad. Religions 2024, 15, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, M. (2024, April 4). Generative AI is Reshaping the World of Customer Experience. https://technologymagazine.com/articles/generative-ai-is-reshaping-the-world-of-customer-experience.

- Lecocq, X.; Warnier, V.; Demil, B.; Plé, L. Using Artificial Intelligence (AI) Generative Technologies For Business Model Design with IDEATe Process: A Speculative Viewpoint. J. Bus. Model. 2024, 12, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marie, J. , & Mathews, J. (2021). A Self-regulatory Framework for AI Ethics: Opportunities and challenges. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/354969383_A_Self-regulatory_Framework_for_AI_Ethics_-_opportunities_and_challenges.

- McKnight, M.A.; Gilstrap, C.M.; Gilstrap, C.A.; Bacic, D.; Shemroske, K.; Srivastava, S. Generative Artificial Intelligence in Applied Business Contexts: A Systematic Review, Lexical Analysis, and Research Framework. J. Appl. Bus. Econ. 2024, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peruchini, M.; da Silva, G.M.; Teixeira, J.M. Between artificial intelligence and customer experience: a literature review on the intersection. Discov. Artif. Intell. 2024, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meskó, B.; Topol, E.J. The imperative for regulatory oversight of large language models (or generative AI) in healthcare. npj Digit. Med. 2023, 6, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mindell, D. (2000). Cybernetics. https://web.mit.edu/esd.83/www/notebook/Cybernetics.PDF.

- Morgan, R.L.; Florez, I.; Falavigna, M.; Kowalski, S.; Akl, E.A.; Thayer, K.A.; Rooney, A.; Schünemann, H.J. Development of rapid guidelines: 3. GIN-McMaster Guideline Development Checklist extension for rapid recommendations. Heal. Res. Policy Syst. 2018, 16, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morse, J.M.; Barrett, M.; Mayan, M.; Olson, K.; Spiers, J. Verification Strategies for Establishing Reliability and Validity in Qualitative Research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2002, 1, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, S. , Reis, J. L., & Rodrigues, L. S. (2021). The Artificial Intelligence in the Personalisation of the Customer Journey – a literature review. https://aisel.aisnet.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1008&context=capsi2021.

- Nabavi, R. T. , & Bijandi, M. S. (2012). (2) (PDF) Bandura’s Social Learning Theory & Social Cognitive Learning Theory. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/267750204_Bandura’s_Social_Learning_Theory_Social_Cognitive_Learning_Theory.

- Naeem, M.; Ozuem, W.; Howell, K.; Ranfagni, S. A Step-by-Step Process of Thematic Analysis to Develop a Conceptual Model in Qualitative Research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2023, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Naqbi, H.; Bahroun, Z.; Ahmed, V. Enhancing Work Productivity through Generative Artificial Intelligence: A Comprehensive Literature Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicklin, J.M.; Williams, K.J. Self-Regulation of Goals and Performance: Effects of Discrepancy Feedback, Regulatory Focus, and Self-Efficacy. Psychology 2011, 02, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, S.U. Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism; JSTOR: New York, NY, United States, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nowell, L.S.; Norris, J.M.; White, D.E.; Moules, N.J. Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2017, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyaaba, M. , Wright, A., & Choi, G. (2024). Generative AI and Digital Neocolonialism in Global Education: Towards an Equitable Framework. [CrossRef]

- Oanh, V.T.K. Evolving Landscape Of E-Commerce, Marketing, and Customer Service: the Impact of Ai Integration. J. Electr. Syst. 2024, 20, 1125–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, D.; Jacobs, C. Developing guiding principles: an organizational learning perspective. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2007, 20, 813–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaniappan, K.; Lin, E.Y.T.; Vogel, S. Global Regulatory Frameworks for the Use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in the Healthcare Services Sector. Healthcare 2024, 12, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Research, Thoughts; Pandey, P.; Pandey, M.M. American Research Thoughts; Pandey, P.; Pandey, M.M.(2024). Research methodology: Tools & techniques.

- Rajaram, K.; Tinguely, P.N. Generative artificial intelligence in small and medium enterprises: Navigating its promises and challenges. Bus. Horizons 2024, 67, 629–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rane, N. , Paramesha, M., Choudhary, S., & Rane, J. (2024). Artificial Intelligence in Sales and Marketing: Enhancing Customer Satisfaction, Experience and Loyalty. SSRN Electronic Journal. [CrossRef]

- Rivas, E.O.D.; Chiappe, A.; Sagredo, A.V. Cybernetics of self-regulation, homeostasis, and fuzzy logic: foundational triad for assessing learning using artificial intelligence. 33, 2024; 33, e0254918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas, E.O.D.; Chiappe, A.; Sagredo, A.V. Cybernetics of self-regulation, homeostasis, and fuzzy logic: foundational triad for assessing learning using artificial intelligence. 33, 2025; 33, e0254918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sai, S.; Gaur, A.; Sai, R.; Chamola, V.; Guizani, M.; Rodrigues, J.J.P.C. Generative AI for Transformative Healthcare: A Comprehensive Study of Emerging Models, Applications, Case Studies, and Limitations. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 31078–31106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, L.R.; Peeples, S.F.; Brooks, M.E. (2024). Generative AI Ethical Considerations and Discriminatory Biases on Diverse Students Within the Classroom (pp. 191–213). [CrossRef]

- Saunders. (2016). Research Methods for Business Students. www.pearson.com/uk.

- Schunk, D.H.; DiBenedetto, M.K. (2020). Social Cognitive Theory, Self-Efficacy, and Students with Disabilities: Implications for Students with Learning Disabilities, Reading Disabilities, and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Scott, W.D.; Cervone, D.; Ebiringah, O.U. The social-cognitive clinician: On the implications of social cognitive theory for psychotherapy and assessment—Scott—2024—International Journal of Psychology—Wiley Online Library. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full10.1002/ijop.13125.

- Isguzar, S.; Fendoglu, E.; SimSek, A.I. Innovative Applications in Businesses: An Evaluation on Generative Artificial Intelligence. www.amfiteatrueconomic.ro 2024, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekine, T. (2025). Security Risks of Generative AI and Countermeasures, and Its Impact on Cybersecurity. NTT DATA. https://www.nttdata.com/global/en/insights/focus/security-risks-of-generative-ai-and-countermeasures.

- Shukla, S. (2023, August 16). Four Reasons Regulations on Generative AI May Do More Harm than Good. IEEE Computer Society. https://www.computer.org/publications/tech-news/community-voices/regulations-on-generative-ai/.

- Sieber, A. Does Facebook Violate Its Users’ Basic Human Rights? NanoEthics 2019, 13, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A. (2021). An Introduction to Experimental and Exploratory Research. SSRN Electronic Journal. [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Chatterjee, S.; Mariani, M. Applications of generative AI and future organizational performance: The mediating role of explorative and exploitative innovation and the moderating role of ethical dilemmas and environmental dynamism. Technovation 2024, 133, 103021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South Africa’s National AI Policy Framework. (2024). South Africa’s National AI Policy Framework. https://fwblaw.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/South-Africa-National-AI-Policy-Framework.pdf.

- Stajkovic, A. , & Stajkovic, K. (2019). Social Cognitive Theory. [CrossRef]

- Tiutiu, M.; Dabija, D.-C. Improving Customer Experience Using Artificial Intelligence in Online Retail. Proc. Int. Conf. Bus. Excel. 2023, 17, 1139–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzafestas, S. G. (2017). Systems, Cybernetics, Control, and Automation. https://www.riverpublishers.com/book_details.php?book_id=455.

- Ullah, A. (2023). Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Customer Experience. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/383561910_Impact_of_Artificial_Intelligence_on_Customer_Journey_Mapping_and_Experience_Design.

- Usher, E.L.; Schunk, D.H. (2017). Social Cognitive Theoretical Perspective of Self-Regulation (pp. 19–35). Routledge, 19–35. [CrossRef]

- Varsha, P. S. How can we manage biases in artificial intelligence systems – A systematic literature review. Int. J. Inf. Manag. Data Insights 2023, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, L.; Letheren, K.; Mulcahy, R. The Rise of Deepfakes: A Conceptual Framework and Research Agenda for Marketing. Australas. Mark. J. 2021, 29, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiener, N. (1948). CYBERNETICS. J. Wiley. https://books.google.co.zw/books/about/Cybernetics.html?id=9ntYxAEACAAJ&redir_esc=y.

- Williamson, S.M.; Prybutok, V. The Era of Artificial Intelligence Deception: Unraveling the Complexities of False Realities and Emerging Threats of Misinformation. Information 2024, 15, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolley, D. (2024). South African organisations are embracing GenAI as a catalyst for innovation. Bizcommunity. https://www.bizcommunity.com/article/south-african-organisations-are-embracing-genai-as-a-catalyst-for-innovation-231017a.

- Yan, W.; Nakajima, T.; Sawada, R. Benefits and Challenges of Collaboration between Students and Conversational Generative Artificial Intelligence in Programming Learning: An Empirical Case Study. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuff, M. (2024). GenAI-Driven Insights for Proactive Performance Monitoring in Omnichannel Systems. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/386451958_GenAI-Driven_Insights_for_Proactive_Performance_Monitoring_in_Omnichannel_Systems.

- Zhai, C.; Wibowo, S.; Li, L.D. The effects of over-reliance on AI dialogue systems on students' cognitive abilities: a systematic review. Smart Learn. Environ. 2024, 11, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuboff, S. (2017). The Age of Surveillance Capitalism. https://www.hachettebookgroup.com/titles/shoshana-zuboff/the-age-of-surveillance-capitalism/9781610395694/?lens=publicaffairs.

| Feature | Social Cognitive Theory | Cybernetics Theory |

| Focus | Human learning, behaviour and cognition, self-regulation (Schunk & DiBenedetto, 2020; Scott et al., 2024; Usher & Schunk, 2017) |

Control and communication through feedback loops (Carver & Scheier, 1998; Mindell, 2000) |

| Origin | Psychology & Education (Bandura, 1986) |

Engineering, Systems Theory, Cybernetics (Wiener, 1948) |

| Key Mechanism | Observational learning, self-efficacy, cognitive processes (Scott et al., 2024) | Feedback loops, control systems, error correction (Espejo & Reyes, 2011) |

| Core Concept | Reciprocal determinism: Behaviour, cognition, and environment influence each other (Abdullah, 2019) | Feedback and regulation: Input, output, and correction to maintain system balance (Mindell, 2000) |

| Agency | Individuals are active agents with goals and self-regulation Scott et al., 2024; (Usher & Schunk, 2017) | Systems may be mechanical, biological, or social, with or without agency ((Tzafestas, 2017) |

| Learning Process | Through observation, imitation, and internal motivation (Harinie et al., 2017) |

Through feedback and adaptation to reduce deviation (Rivas et al., 2025) |

| Role of Feedback | Used for self-regulation, self-reflection (Nicklin & Williams, 2011; Schunk & DiBenedetto, 2020) | Central to system functioning and stability (Espejo & Reyes, 2011) |

| Participant ID | Technological Background | Years Experience | Years Experience in GenAI |

| Participant 1 | IT Lecturer | 12 | 2 |

| Participant 2 | Tech entrepreneur | 6 | 1 |

| Participant 3 | Entrepreneur in Technology | 12 | 3 |

| Participant 4 | Storage Engineer | 30 | 0 |

| Participant 5 | Doctorate in Machine Learning and Head of Technology | 8 | 3 |

| Participant 6 | Owner of a Tech Company | 20 | 2 |

| Participant 7 | Founder of a Tech Company | 7 | 2 |

| Participant 8 | Managing Director of a Tech Company | 16 | 5 |

| Participant 9 | Software Development in electrical engineering | 18 | 5 |

| Participant 10 | Application testing specialist | 5 | 1 |

| Participant 11 | Head of Operations in a Technology Company | 18 | 2 |

| Participant 12 | Project Manager in a Technology Company | 15 | 2 |

| Participant 13 | Coding and Development | 6 | 2 |

| Participant 14 | Systems Integration Specialist | 10 | 1 |

| Participant 15 | IT Personnel | 15 | 4 |

| Participant 16 | Tech Training and Development | 10 | 2 |

| Participant 17 | Software Engineering | 10 | 2 |

| Participant 18 | Information Systems student and software developer | 6 | 1 |

| Participant 19 | Head of Training and Development of a Tech Company | 24 | 15* |

| Participant 20 | Tech entrepreneur | 6 | 1 |

| Participant 21 | Modeler | 5 | 1 |

| Topic | Description and rationale | Features, characteristics and mechanisms | ||

| Focus | Mechanism | Learning process | ||

|

Clarifies what GenAI is designed to do, sets expectations to assist users understand what GenAI can and cannot do, and makes it clear whether a user is engaging with a human or a GenAI system. | Clarity, learning | Observational learning, Standard Operating Procedures (SOP), Manual | Human Learning and Understanding of GenAI from the SOP, manuals and interactions with the model |

|

Ensures that GenAI-generated outcomes (texts, decisions, predictions) are as factually accurate and relevant as possible. Promotes equity and inclusion by identifying and reducing algorithmic bias and encourages intentional, ethical design that reflects fairness across diverse demographics. | Accuracy | Self-Monitoring algorithm, performance logs, Feedback loops | Algorithm learning data, Performance Logs, Feedback |

|

Protects users’ rights and privacy by ensuring AI does not leak, misuse, or over-collect personal data, maintains trust by minimising vulnerabilities and risk of data breaches, and ensures legal compliance with privacy, and mitigates reputational and operational risks linked to security failures. | Security | Data Security Control Systems | Observational Learning, |

|

GenAI systems to respond to user emotions in ways that feel human-sensitive, while avoiding over-personification of AI, which can mislead users into forming attachments or expecting understanding AI cannot truly offer. | Empathy | Cognitive processes (empathy) | Observational Learning and Imitation |

|

GenAI system performance to be self-monitored to identify any gaps and any anomalies such as bias, hallucinations and security gaps | Self-monitoring | Observation of GenAI models | Observational learning of the patterns and behaviour of the model to mitigate any gaps |

|

Judging the performance of the GenAI model to discern the quality of output to determine whether business and customers are benefitting or gaps are being created | Judgement | The imitation of business standards as personal judgement can be biased or subjective | Objective learning of business ethics, standards and principles and benchmarking performance in line with expected business standards not personal values |

|

Reacting to performance after discerning the quality. For example, if the GenAI model hallucinates the model requires re-training | Self-Reaction | Cognitive processes and internal motivation to initiate interventions that regulate the GenAI model | Control systems over the GenAI to be able to correct the model when it is malfunctioning |

|

The belief in the ability to self-regulate the GenAI model | Self-efficacy | Cognitive process and internal motivation to become efficient | Based on the belief and motivation and confidence that one is efficient and able to self-regulate; making interventions to self-regulate and being efficient in the self-regulation of GenAI model |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).