Submitted:

18 April 2025

Posted:

21 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Research and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Theoretical Research

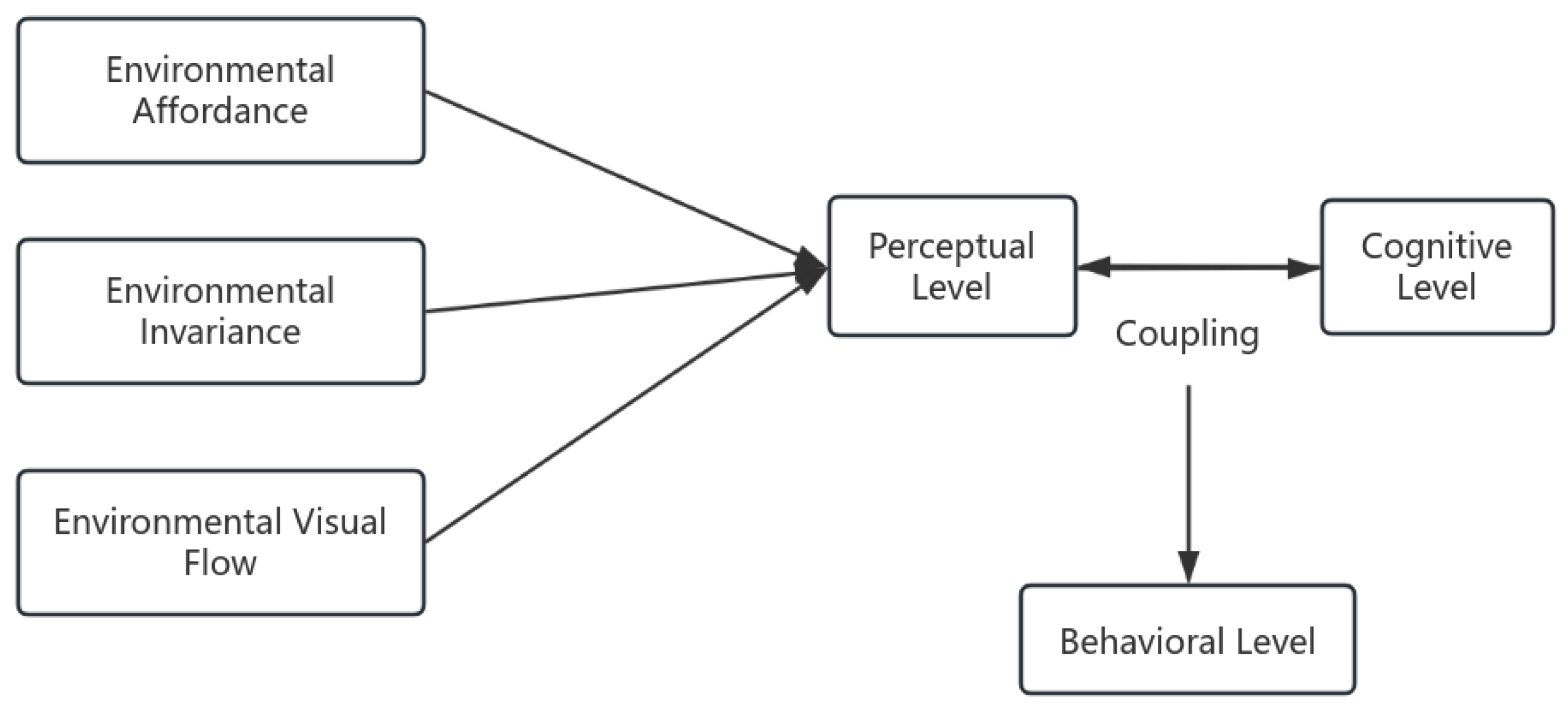

- (1) Gibson's Spatial Aesthetics

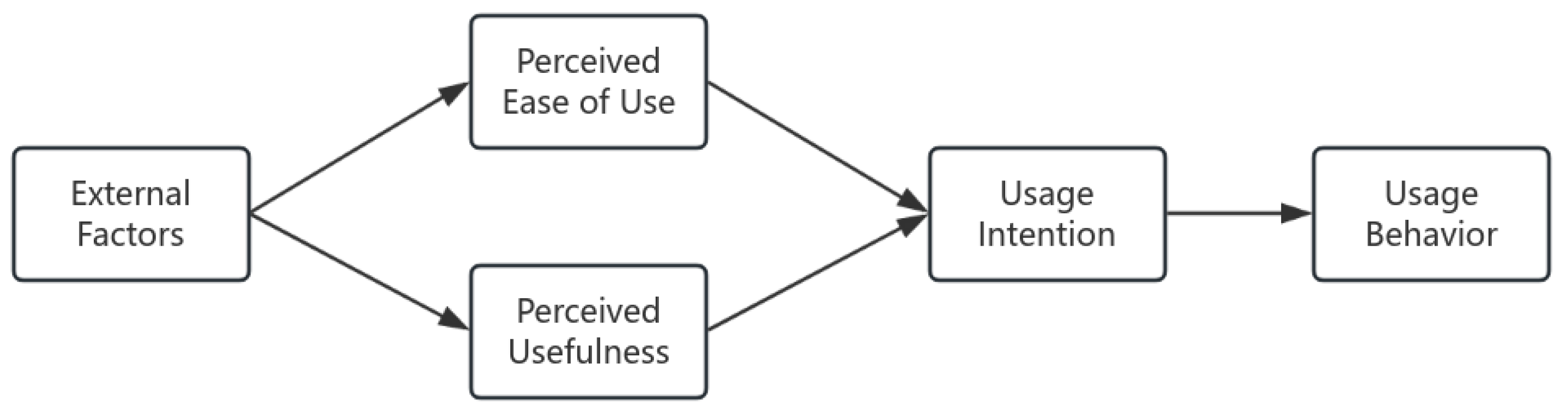

- (2) Technology Acceptance Model (TAM)

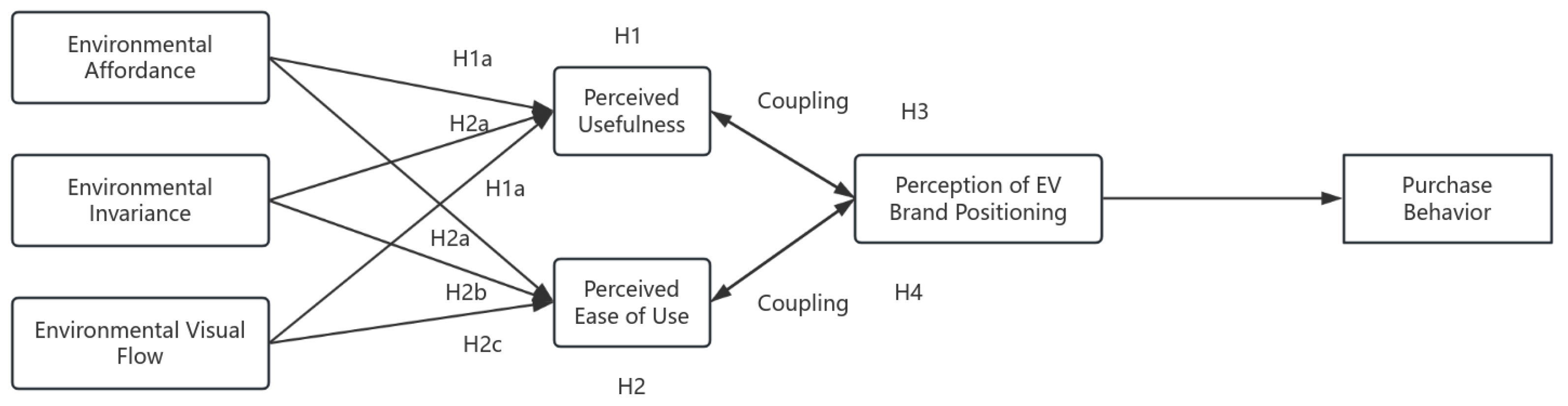

2.2. Research Hypotheses

3. Research Design

3.1. Method of Measurement

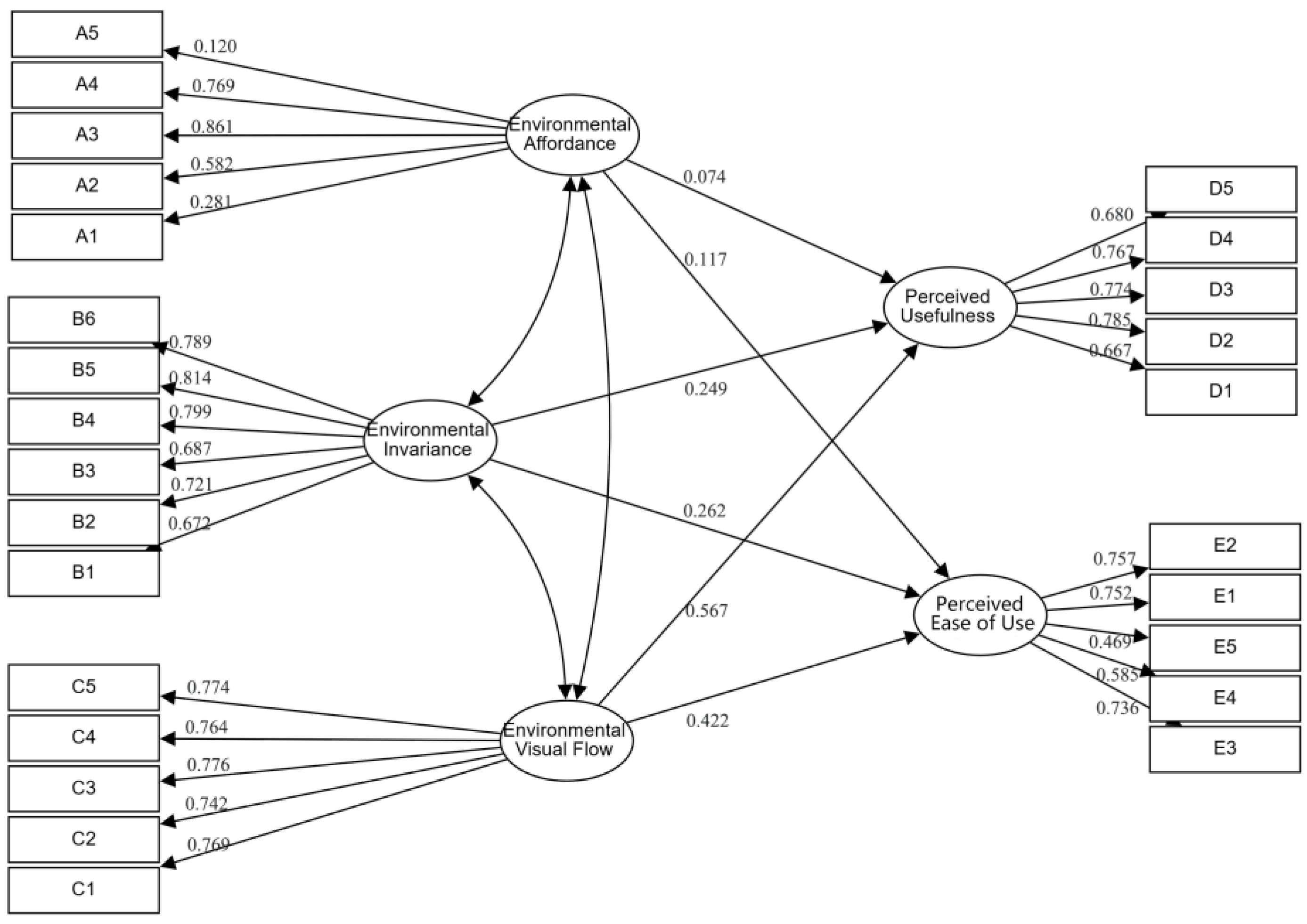

3.2. Model Construction

3.3. Data Collection

3.4. Research Methods

4. Empirical Analysis

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

4.2. Reliability and Validity Testing

4.3. Correlation and VIF Test

4.4. Structural Analysis

3.5. Multiple Regression Analysis

3.6. Further Discussion

5. Suggestion

| 1 | Zhang, Y., Zhang, C., & Kang, W. (2024). An exploration of the development of China’s new energy vehicle industry from the perspective of logistics chains. New Economy Review, (5), 51–58. |

| 2 | Atabani, A.E.; Badruddin, I.A.; Mekhilef, S.; Silitonga, A.S. A review on global fuel economy standards, labels and technologies in the transportation sector. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 4586–4610. |

| 3 | Wang, N.; Tang, L.; Pan, H. Effectiveness of policy incentives on electric vehicle acceptance in China: A discrete choice analysis. Transp. Res. A Policy Pract. 2017, 105, 210–218. |

| 4 | He, X. (2024). User attention analysis on video-based social platforms during the initial launch of Xiaomi SU7: Based on popular video and comment data from Douyin. E-commerce Review, 13(4), 8. |

| 5 | Xia, Y. (2025). An analysis of BYD’s marketing strategies for new energy vehicles. Modernization of Shopping Malls. |

| 6 | Yuan X, Liu X, Zuo J. The development of new energy vehicles for a sustainable future: A review[J]. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2015, 42: 298-305. |

| 7 | Liu Y, Kokko A. Who does what in China’s new energy vehicle industry?[J]. Energy policy, 2013, 57: 21-29. |

| 8 | Ren, J. (2018). New energy vehicle in China for sustainable development: Analysis of success factors and strategic implications. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 59, 268-288. |

| 9 | Goldstein E B. The ecology of JJ Gibson's perception[J]. Leonardo, 1981, 14(3): 191-195. |

| 10 | Flach J M, Holden J G. The reality of experience: Gibson's way[J]. Presence, 1998, 7(1): 90-95. |

| 11 | Zaitchik A K. Applying Gibson's Theory of Affordances to Interior Design[J]. The International Journal of Design in Society, 2015, 8(3-4): 1. |

| 12 | Gay F, Cazzaro I. Environmental Affordances: Some Meetings Between Artificial Aesthetics and Interior Design Theory[C]//International Conference Design! OPEN: Objects, Processes, Experiences and Narratives. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, 2022: 354-364. |

| 13 | Folkmann M N. Evaluating aesthetics in design: A phenomenological approach[J]. Design Issues, 2010, 26(1): 40-53. |

| 14 | Environmental aesthetics: Theory, research, and application[M]. Cambridge University Press, 1992. |

| 15 | Crippen M. Aesthetics and action: situations, emotional perception and the Kuleshov effect[J]. Synthese, 2021, 198(Suppl 9): 2345-2363. |

| 16 | Victor G J. Visual Depiction in James Gibson's Ecological Perception: Direct Perception, Imagination, and A-aesthetic Value[D]. Whitman College, 2022. |

| 17 | Riley H. The Domains of Aesthetics and Perception Theories: A Review Relevant to Practice-based Doctoral Theses in the Visual Arts[J]. Journal of Aesthetic Education, 2024, 58(2): 78-126. |

| 18 | Bornstein M H. The ecological approach to visual perception[J]. 1980. |

| 19 | |

| 20 | Momani A M, Jamous M. The evolution of technology acceptance theories[J]. International journal of contemporary computer research (IJCCR), 2017, 1(1): 51-58. |

| 21 | Taherdoost H. A review of technology acceptance and adoption models and theories[J]. Procedia manufacturing, 2018, 22: 960-967. |

| 22 | Alomary A, Woollard J. How is technology accepted by users? A review of technology acceptance models and theories[J]. 2015. |

| 23 | Sohn K, Kwon O. Technology acceptance theories and factors influencing artificial Intelligence-based intelligent products[J]. Telematics and Informatics, 2020, 47: 101324. |

| 24 | Venkatesh V. Technology acceptance model and the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology[J]. Wiley encyclopedia of management, 2015: 1-9. |

| 25 | Wang N, Tian H, Zhu S, et al. Analysis of public acceptance of electric vehicle charging scheduling based on the technology acceptance model[J]. Energy, 2022, 258: 124804. |

| 26 | Müller J M. Comparing technology acceptance for autonomous vehicles, battery electric vehicles, and car sharing—A study across Europe, China, and North America[J]. Sustainability, 2019, 11(16): 4333. |

| 27 | Thilina D K, Gunawardane N. The effect of perceived risk on the purchase intention of electric vehicles: an extension to the technology acceptance model[J]. International Journal of Electric and Hybrid Vehicles, 2019, 11(1): 73-84. |

| 28 | Shanmugavel N, Micheal M. Exploring the marketing related stimuli and personal innovativeness on the purchase intention of electric vehicles through Technology Acceptance Model[J]. Cleaner Logistics and Supply Chain, 2022, 3: 100029. |

| 29 | Yousif R O, Alsamydai M J. Perspective of Technological Acceptance Model toward Electric Vehicle[J]. International Journal of Mechanical and Production Engineering Research and Development, 2019, 9(5): 873-884. |

| 30 | Roemer E, Henseler J. The dynamics of electric vehicle acceptance in corporate fleets: Evidence from Germany[J]. Technology in Society, 2022, 68: 101938. |

| 31 | Kaur N, Sahdev S L, Bhutani R S. Analyzing adoption of electric vehicles in India for sustainable growth through application of technology acceptance model[C]//2021 International Conference on Innovative Practices in Technology and Management (ICIPTM). IEEE, 2021: 255-260. |

| 32 | Bektaş B C, Akyıldız Alçura G. Understanding Electric Vehicle Adoption in Türkiye: Analyzing User Motivations Through the Technology Acceptance Model[J]. Sustainability, 2024, 16(21): 9439. |

| 33 | Zhang B S, Ali K, Kanesan T. A model of extended technology acceptance for behavioral intention toward EVs with gender as a moderator[J]. Frontiers in Psychology, 2022, 13: 1080414. |

| 34 | Will C, Schuller A. Understanding user acceptance factors of electric vehicle smart charging[J]. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 2016, 71: 198-214. |

| 35 | Davis F D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology[J]. MIS quarterly, 1989: 319-340. |

| 36 | Davis F D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology[J]. MIS quarterly, 1989: 319-340. |

| 37 | Keller K L. Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity[J]. Journal of marketing, 1993, 57(1): 1-22. |

| 38 | Aaker D A. Measuring brand equity across products and markets[J]. California management review, 1996, 38(3). |

References

- Zhang, Y., Zhang, C., & Kang, W. (2024). An exploration of the development of China’s new energy vehicle industry from the perspective of logistics chains. New Economy Review, (5), 51–58.

- Atabani, A.E.; Badruddin, I.A.; Mekhilef, S.; Silitonga, A.S. A review on global fuel economy standards, labels and technologies in the transportation sector. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 4586–4610. [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Tang, L.; Pan, H. Effectiveness of policy incentives on electric vehicle acceptance in China: A discrete choice analysis. Transp. Res. A Policy Pract. 2017, 105, 210–218. [CrossRef]

- He, X. (2024). User attention analysis on video-based social platforms during the initial launch of Xiaomi SU7: Based on popular video and comment data from Douyin. E-commerce Review, 13(4), 8.

- Xia, Y. (2025). An analysis of BYD’s marketing strategies for new energy vehicles. Modernization of Shopping Malls.

- Yuan X, Liu X, Zuo J. The development of new energy vehicles for a sustainable future: A review[J]. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2015, 42: 298-305. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Kokko A. Who does what in China’s new energy vehicle industry?[J]. Energy policy, 2013, 57: 21-29.

- Ren, J. (2018). New energy vehicle in China for sustainable development: Analysis of success factors and strategic implications. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 59, 268-288. [CrossRef]

- Goldstein E B. The ecology of JJ Gibson's perception[J]. Leonardo, 1981, 14(3): 191-195.

- Flach J M, Holden J G. The reality of experience: Gibson's way[J]. Presence, 1998, 7(1): 90-95.

- Zaitchik A K. Applying Gibson's Theory of Affordances to Interior Design[J]. The International Journal of Design in Society, 2015, 8(3-4): 1.

- Gay F, Cazzaro I. Environmental Affordances: Some Meetings Between Artificial Aesthetics and Interior Design Theory[C]//International Conference Design! OPEN: Objects, Processes, Experiences and Narratives. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, 2022: 354-364.

- Folkmann M N. Evaluating aesthetics in design: A phenomenological approach[J]. Design Issues, 2010, 26(1): 40-53. [CrossRef]

- Environmental aesthetics: Theory, research, and application[M]. Cambridge University Press, 1992.

- Crippen M. Aesthetics and action: situations, emotional perception and the Kuleshov effect[J]. Synthese, 2021, 198(Suppl 9): 2345-2363.

- Victor G J. Visual Depiction in James Gibson's Ecological Perception: Direct Perception, Imagination, and A-aesthetic Value[D]. Whitman College, 2022.

- Riley H. The Domains of Aesthetics and Perception Theories: A Review Relevant to Practice-based Doctoral Theses in the Visual Arts[J]. Journal of Aesthetic Education, 2024, 58(2): 78-126. [CrossRef]

- Bornstein M H. The ecological approach to visual perception[J]. 1980.

- Momani A M, Jamous M. The evolution of technology acceptance theories[J]. International journal of contemporary computer research (IJCCR), 2017, 1(1): 51-58.

- Taherdoost H. A review of technology acceptance and adoption models and theories[J]. Procedia manufacturing, 2018, 22: 960-967. [CrossRef]

- Alomary A, Woollard J. How is technology accepted by users? A review of technology acceptance models and theories[J]. 2015.

- Sohn K, Kwon O. Technology acceptance theories and factors influencing artificial Intelligence-based intelligent products[J]. Telematics and Informatics, 2020, 47: 101324. [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh V. Technology acceptance model and the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology[J]. Wiley encyclopedia of management, 2015: 1-9.

- Wang N, Tian H, Zhu S, et al. Analysis of public acceptance of electric vehicle charging scheduling based on the technology acceptance model[J]. Energy, 2022, 258: 124804. [CrossRef]

- Müller J M. Comparing technology acceptance for autonomous vehicles, battery electric vehicles, and car sharing—A study across Europe, China, and North America[J]. Sustainability, 2019, 11(16): 4333. [CrossRef]

- Thilina D K, Gunawardane N. The effect of perceived risk on the purchase intention of electric vehicles: an extension to the technology acceptance model[J]. International Journal of Electric and Hybrid Vehicles, 2019, 11(1): 73-84.

- Shanmugavel N, Micheal M. Exploring the marketing related stimuli and personal innovativeness on the purchase intention of electric vehicles through Technology Acceptance Model[J]. Cleaner Logistics and Supply Chain, 2022, 3: 100029. [CrossRef]

- Yousif R O, Alsamydai M J. Perspective of Technological Acceptance Model toward Electric Vehicle[J]. International Journal of Mechanical and Production Engineering Research and Development, 2019, 9(5): 873-884.

- Roemer E, Henseler J. The dynamics of electric vehicle acceptance in corporate fleets: Evidence from Germany[J]. Technology in Society, 2022, 68: 101938. [CrossRef]

- Kaur N, Sahdev S L, Bhutani R S. Analyzing adoption of electric vehicles in India for sustainable growth through application of technology acceptance model[C]//2021 International Conference on Innovative Practices in Technology and Management (ICIPTM). IEEE, 2021: 255-260.

- Bektaş B C, Akyıldız Alçura G. Understanding Electric Vehicle Adoption in Türkiye: Analyzing User Motivations Through the Technology Acceptance Model[J]. Sustainability, 2024, 16(21): 9439.

- Zhang B S, Ali K, Kanesan T. A model of extended technology acceptance for behavioral intention toward EVs with gender as a moderator[J]. Frontiers in Psychology, 2022, 13: 1080414. [CrossRef]

- Will C, Schuller A. Understanding user acceptance factors of electric vehicle smart charging[J]. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 2016, 71: 198-214. [CrossRef]

- Davis F D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology[J]. MIS quarterly, 1989: 319-340.

- Davis F D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology[J]. MIS quarterly, 1989: 319-340.

- Keller K L. Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity[J]. Journal of marketing, 1993, 57(1): 1-22.

- Aaker D A. Measuring brand equity across products and markets[J]. California management review, 1996, 38(3). [CrossRef]

| Open Coding (Original Empirical Concepts) | Principal Axis Coding (Mid-Level Categories) | Selective Coding (Core Theoretical Categories) | Main Category |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Sitting Posture, Spatial Fit | Spatial Configuration Accessibility | Adaptability of Spatial Aesthetics to Behavioral Guidance | Environmental affordance |

| Steering Wheel Feel, Control Matching | Matching of Interface Structure and Physical Naturalness | Enhancement of Driving Behavior Naturalness Through Spatial Operation Design | |

| Operational Intuition, Blind Operation Friendliness, Button Layout Logic | Operational Accessibility and Information Acquisition | The Embodiment Mechanism of Intuitive Operability in Spatial Interaction | |

| Logical placement of interface information, reducing cognitive load | Intuitiveness of the human-computer interaction | Guidance of functional layout to enhance user perception efficiency | |

| Long-term riding support, ergonomic design, and physiological seat matching | Adaptation of the spatial physical structure | Aesthetic support from the cockpit structure for the user's physiological needs | |

| Information stability during scene transitions | Stable visual recognition across multiple contexts | Visual constancy of the spatial structure during dynamic use | Environmental invariance |

| Nighttime visibility, backlight adjustment, and adaptability to low-light environments | Brightness perception stability | Aesthetic support for stable information perception in low-light conditions | |

| Anti-glare screen, sunlight shielding strategy, and daytime visual impairment avoidance mechanism | Brightness adapts to ambient light intensity | Visual interference adjustment mechanism supporting spatial constancy | |

| Use of anti-reflective materials and driving vision continuity | Visual information integrity under interfering factors | Field-of-view stabilization mechanism in dynamic environments | |

| Brightness perception self-regulation system with light-sensitive feedback | Consistent system visual feedback | Support path of the environmental visual adjustment mechanism for information recognition | |

| Simple navigation interface and HUD synchronization function | Efficient key information acquisition | Consistent information availability across different environments | |

| Dynamic spatial design, visual triggering of speed sensation | The mechanism by which visual fluidity evokes driving rhythm | Spatial aesthetics' role in the perceptual guidance of driving behavior | Environmental visual flow |

| Interface animation fluency and visual rhythm representing speed feedback | Dynamic visual guidance mechanism | The guiding path of dynamic information display on the perception of driving rhythm | |

| Light source distribution and its spatial guidance function | The construction mechanism of a sense of security under the guidance of light and shadow | The guiding function of the lighting system in direction recognition | |

| Multi-material integration, construction of visual depth layers, and expression of spatial layering | Visual multi-dimensional structural sense | The mechanism for creating visual three-dimensionality | |

| Sense of information linkage, consistency between speed and visual feedback | Synchronization mechanism of information movement rhythm | Perceptual docking mechanism between visual dynamics and physical movement |

| MEASUREMENT ITEM | QUESTION | NO. |

|---|---|---|

| ENVIRONMENTAL AFFORDANCE | Do you think the overall layout of the electric car cabin meets your driving needs? | A1 |

| Do the size and shape of the steering wheel fit your grip habits? | A2 | |

| Are the physical buttons inside the car positioned reasonably for intuitive operation? | A3 | |

| Is the layout of the touchscreen interface convenient for quickly finding the functions you need? | A4 | |

| Do you find that the comfort and positioning of the Seat meet your body's support needs? | A5 | |

| ENVIRONMENTAL INVARIANCE | In various driving scenarios (e.g., city, highway, mountainous areas), can you still clearly identify the in-car operation interface? | B1 |

| When driving at night, are the Dashboard, touchscreen, and center console information clearly readable? | B2 | |

| Does the in-car screen maintain good visibility under strong light (e.g., direct sunlight on a sunny day)? | B3 | |

| Does the window glass effectively reduce reflections or external light interference to maintain a clear view? | B4 | |

| Can the brightness of the in-car screen automatically adjust to adapt to different ambient lighting conditions? | B5 | |

| Does the in-car information (navigation, dashboard, HUD display, etc.) help you quickly obtain key information in different driving states? | B6 | |

| ENVIRONMENTAL VISUAL FLOW | Do you think the visual design of the electric car cockpit helps you better perceive changes in speed? | C1 |

| Are the in-car screen animations (such as dashboard RPM, navigation interface changes) smooth and do they enhance your sense of driving rhythm? | C2 | |

| When driving at night, do the interior and exterior lights (dashboard, ambient lighting, headlights, etc.) help enhance your sense of direction and security? | C3 | |

| Do the materials inside the car (such as the seats, dashboard, and door panels) visually enhance the spatial layering, making the cockpit more three-dimensional? | C4 | |

| Do you think the animation of the in-car information display is well-coordinated with the driving status (e.g., turning, acceleration, and braking)? | C5 |

| Measurement Dimension | Questionnaire Items | Literature Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived usefulness of spatial aesthetics | 1. I believe this electric car can effectively improve my daily commuting efficiency. | Davis (1989)35 | D1 |

| 2. Using this electric car helps to reduce travel costs. | D2 | ||

| 3. This electric car enhances my driving experience. | D3 | ||

| 4. This model provides the core functionalities I need for daily commuting. | D4 | ||

| 5. This product is significantly helpful in my life or work. | D5 | ||

| Perceived ease of use of spatial aesthetics | 1. Learning how to operate this electric car is easy for me. | Davis (1989)36 | E1 |

| 2. Using the functions of this electric car is not confusing. | E2 | ||

| 3. I can quickly find the functions or information I need when operating this car. | E3 | ||

| 4. This electric car has a clear and intuitive interface design. | E4 | ||

| 5. I believe that driving this car daily does not require excessive effort or instruction. | E5 | ||

| Brand positioning perception | 1. I believe this brand, to some extent, represents a certain type of electric car. | Keller (1993);37 Aaker (1996)38 | F1 |

| 2. The brand's market positioning has made a strong impression on me. | F2 | ||

| 3. Compared to other brands, this brand's positioning is clearer and more defined. | F3 | ||

| 4. The brand's models effectively reflect the brand image promoted in its advertising. | F4 | ||

| 5. When I think of electric cars, this brand is the first to come to mind. | F5 | ||

| 6. This brand's product characteristics align with my expectations regarding its positioning. | F6 |

| Name | Option | Frequency

|

Percentage (%)

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 834 | 52.92 |

| Female | 742 | 47.08 | |

| Age | 18-25 years | 75 | 4.76 |

| 26-35 years | 680 | 43.15 | |

| 36-45 years | 478 | 30.33 | |

| 46-55 years | 325 | 20.62 | |

| Over 55 years | 18 | 1.14 | |

| Educational Background | High school or below | 174 | 11.04 |

| High school | 131 | 8.31 | |

| Bachelor's Degree | 730 | 46.32 | |

| Master's degree | 411 | 26.08 | |

| Doctorate | 330 | 20.94 | |

| Car brand positioning preference | Performance-oriented | 636 | 40.36 |

| Safety-oriented | 108 | 6.85 | |

| Technology-oriented | 214 | 13.58 | |

| Energy-saving and environmentally friendly | 264 | 16.75 | |

| Luxury and prestige model | 354 | 22.46 | |

| Monthly Income | Below 5,000 yuan | 328 | 20.81 |

| 5,001-15,000 yuan | 624 | 39.59 | |

| 15,001-50,000 yuan | 445 | 28.24 | |

| Above 50,001 yuan | 179 | 11.36 |

| Name | Cronbach's α coefficient

|

Average Variance Extracted (AVE) Value | Composite Reliability (CR) Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental affordance | 0.870 | 0.354 | 0.678 |

| Environmental invariance | 0.898 | 0.562 | 0.885 |

| Environmental visual flow | 0.891 | 0.590 | 0.878 |

| Perceived usefulness of spatial aesthetics | 0.868 | 0.542 | 0.855 |

| Perceived ease of use of spatial aesthetics | 0.796 | 0.447 | 0.796 |

| Brand positioning perception | 0.804 | 0.419 | 0.786 |

| Mean | Standard Deviation | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | VIF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental affordance | 3.070 | 0.690 | 1 | 1.538 | |||||

| Environmental invariance | 3.515 | 0.976 | 0.580** | 1 | 2.614 | ||||

| Environmental visual flow | 3.610 | 0.970 | 0.439** | 0.701** | 1 | 2.486 | |||

| Perceived usefulness of spatial aesthetics | 3.607 | 0.936 | 0.466** | 0.663** | 0.709** | 1 | 2.454 | ||

| Perceived ease of use of spatial aesthetics | 3.288 | 1.182 | 0.054* | 0.111** | 0.135** | 0.236** | 1 | 1.085 | |

| Brand positioning perception | 4.129 | 0.777 | 0.249** | 0.359** | 0.292** | 0.379** | 0.201** | 1 | 1.222 |

| * p<0.05 ** p<0.01 | |||||||||

| X | → | Y | Standardized regression coefficient | SE | z (CR value) | p |

| Environmental Affordance | → | Perceived Usefulness | 0.074 | 0.067 | 2.900 | 0.004 |

| Environmental Affordance | → | Perceived Ease of Use | 0.117 | 0.093 | 3.853 | 0.000 |

| Environmental Invariance | → | Perceived Usefulness | 0.249 | 0.034 | 6.157 | 0.000 |

| Environmental Invariance | → | Perceived Ease of Use | 0.262 | 0.045 | 5.676 | 0.000 |

| Environmental Visual Flow | → | Perceived Usefulness | 0.567 | 0.036 | 13.234 | 0.000 |

| Environmental Visual Flow | → | Perceived Ease of Use | 0.422 | 0.043 | 9.351 | 0.000 |

| Environmental Affordance | → | A5 | 0.120 | 0.134 | 3.936 | 0.000 |

| Environmental Affordance | → | A4 | 0.769 | 0.302 | 9.948 | 0.000 |

| Environmental Affordance | → | A3 | 0.861 | 0.423 | 9.974 | 0.000 |

| Environmental Affordance | → | A2 | 0.582 | 0.309 | 9.512 | 0.000 |

| Environmental Affordance | → | A1 | 0.281 | - | - | - |

| Environmental Invariance | → | B6 | 0.789 | 0.038 | 26.859 | 0.000 |

| Environmental Invariance | → | B5 | 0.814 | 0.038 | 27.564 | 0.000 |

| Environmental Invariance | → | B4 | 0.799 | 0.038 | 27.148 | 0.000 |

| Environmental Invariance | → | B3 | 0.687 | 0.035 | 23.838 | 0.000 |

| Environmental Invariance | → | B2 | 0.721 | 0.039 | 24.869 | 0.000 |

| Environmental Invariance | → | B1 | 0.672 | - | - | - |

| Environmental Visual Flow | → | C5 | 0.774 | 0.032 | 30.698 | 0.000 |

| Environmental Visual Flow | → | C4 | 0.764 | 0.032 | 30.260 | 0.000 |

| Environmental Visual Flow | → | C3 | 0.776 | 0.033 | 30.786 | 0.000 |

| Environmental Visual Flow | → | C2 | 0.742 | 0.032 | 29.241 | 0.000 |

| Environmental Visual Flow | → | C1 | 0.769 | - | - | - |

| Perceived Usefulness | → | D5 | 0.680 | 0.046 | 23.012 | 0.000 |

| Perceived Usefulness | → | D4 | 0.767 | 0.046 | 25.447 | 0.000 |

| Perceived Usefulness | → | D3 | 0.774 | 0.047 | 25.645 | 0.000 |

| Perceived Usefulness | → | D2 | 0.785 | 0.047 | 25.914 | 0.000 |

| Perceived Usefulness | → | D1 | 0.667 | - | - | - |

| Perceived Ease of Use | → | E2 | 0.757 | 0.037 | 26.973 | 0.000 |

| Perceived Ease of Use | → | E1 | 0.752 | - | - | - |

| Perceived Ease of Use | → | E5 | 0.469 | 0.041 | 16.764 | 0.000 |

| Perceived Ease of Use | → | E4 | 0.585 | 0.043 | 20.955 | 0.000 |

| Perceived Ease of Use | → | E3 | 0.736 | 0.037 | 26.298 | 0.000 |

| Note: → indicates a regression influence or measurement relationship | ||||||

| The hyphen '-' indicates that the item serves as a reference | ||||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Constant | 1.249**(6.149) | 0.546**(2.846) | -0.307(-1.570) |

| Perceived Usefulness of Spatial Aesthetics * Brand Positioning Perception Coupling | 0.086**(3.701) | 0.044*(2.261) | 0.050**(2.803) |

| Gender | -0.235**(-5.140) | -0.243**(-5.806) | |

| Age | 0.479**(22.118) | 0.310**(12.673) | |

| Educational Background | 0.387**(11.839) | ||

| Car brand positioning preference | 0.111**(8.209) | ||

| Monthly Income | -0.143**(-7.200) | ||

| Sample Size | 1576 | 1576 | 1576 |

| R 2 | 0.319 | 0.323 | 0.435 |

| F value | F (1,1574)=13.695,p=0.000 | F (3,1572)=250.467,p=0.000 | F (6,1569)=201.673,p=0.000 |

| Note: Dependent variable = Purchase Intention | |||

| * p<0.05 ** p<0.01 (t-values in parentheses) | |||

| (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Constant | -0.762**(-5.398) | -0.468**(-2.580) | -0.223(-1.096) |

| Perceived Ease of Use of Spatial Aesthetics * Brand Positioning Perception Coupling | 0.209**(12.951) | 0.212**(13.135) | 0.184**(11.652) |

| Gender | -0.058(-1.100) | -0.095(-1.860) | |

| Age | -0.080**(-3.247) | 0.136**(4.426) | |

| Educational Background | 0.041(1.002) | ||

| Car brand positioning preference | -0.117**(-7.109) | ||

| Monthly Income | -0.197**(-6.587) | ||

| Sample Size | 1576 | 1576 | 1576 |

| R 2 | 0.096 | 0.102 | 0.168 |

| F value | F (1,1574)=167.739,p=0.000 | F (3,1572)=59.754,p=0.000 | F (6,1569)=52.942,p=0.000 |

| Note: Dependent variable = A1 | |||

| * p<0.05 ** p<0.01 (t-values in parentheses) | |||

| Overall | Performance-oriented | Safety-oriented | Technology-oriented | Energy-saving and environmentally friendly | Luxury and prestige model | |||

| Constant | 0.315(1.471) | 0.365(0.567) | 1.181(2.565) | 0.320(0.510) | 0.147(0.296) | 1.402(-2.031) | ||

| Perceived Usefulness of Spatial Aesthetics * Brand Positioning Perception Coupling | 0.043*(2.284) | 0.118*(1.500) | 0.478*(1.517) | 0.027*(0.365) | 0.033*(0.640) | 0.773*(2.588) | ||

| Perceived Ease of Use of Spatial Aesthetics * Brand Positioning Perception Coupling | 0.036**(2.590) | 0.128*(1.302) | 0.610*(0.170) | 0.091(1.106) | -0.030(-0.763) | 0.748**(2.683) | ||

| Gender | -0.237**(-5.571) | -0.261(-1.775) | -0.236**(-2.912) | -0.153(-1.401) | -0.361**(-4.378) | -0.152(-1.681) | ||

| Age | 0.303**(12.245) | 0.385**(3.923) | 0.351**(7.878) | 0.344**(5.474) | 0.268**(5.331) | 0.217**(4.027) | ||

| Education | 0.387**(11.697) | 0.404**(3.607) | 0.417**(6.062) | 0.291**(3.162) | 0.353**(6.239) | 0.493**(6.632) | ||

| Monthly Income | 0.127**(9.424) | 0.096(1.789) | 0.104**(4.255) | 0.146**(4.002) | 0.129**(4.676) | 0.143**(5.135) | ||

| Sample Size | 1576 | 636 | 108 | 214 | 264 | 354 | ||

| R 2 | 0.423 | 0.481 | 0.463 | 0.415 | 0.431 | 0.395 | ||

| Adjusted R 2 | 0.421 | 0.458 | 0.453 | 0.398 | 0.421 | 0.384 | ||

| F value | F (7,1568)=164.266,p=0.000 | F (7,162)=21.421,p=0.000 | F (7,381)=46.934,p=0.000 | F (7,245)=24.791,p=0.000 | F (7,369)=40.006,p=0.000 | F (7,379)=35.335,p=0.000 | ||

| * p<0.05 ** p<0.01 | ||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).