1. Introduction

Artificial Intelligence tools have been successfully integrated with healthcare [

1], robotics [

2], commerce [

3] and energy [

4]. AI applications span many fields, leveraging vast data sources to derive insights, automate processes, and improve user experiences. In healthcare, AI-driven systems assist in medical imaging analysis, drug discovery, and predictive diagnostics, leading to faster and more accurate treatment plans. AI enhances fraud detection, risk assessment, and algorithmic trading in finance, ensuring secure and efficient transactions. Similarly, autonomous vehicles and intelligent traffic management systems optimize mobility and safety in transportation. AI also plays a pivotal role in cybersecurity, where machine learning models detect anomalies and prevent cyber threats in real time. Additionally, education, retail, and entertainment industries benefit from AI-powered chatbots, recommendation engines, and virtual assistants, making interactions more personalized and seamless. As AI technology advances, its integration into various domains redefines productivity, innovation, and how humans interact with machines.

AI tools have seen a recent foray in education, providing valuable resources to students and educators alike. However, their rapid and vast rise necessitates research that can provide a foothold for policymakers, AI developers, and users alike to better understand the advantages and the issues that arise from their use.

The contributions of this study are threefold:

Categorize AI-based educational support tools into three primary types based on their intended purpose.

Outline an analytical review of the benefits and issues using each categorical tool.

Provide relevant examples of prevalent tools in education.

This study categorizes AI as an educational support tool in three categories.

Figure 1 shows the three primary categories for AI-backed tools.

Significant research has referred to AI-backed tools in various ways, particularly in the last 5 years.

Table 1 reviews recent research published since 2023 that studies AI tools.

2. Taxonomy of AI Tools in Education

The following section categorizes AI-backed education tools into types based on their intended purpose. Based on the primary functionality that the tool provides, the three main categories are outlined below, with a discussion of their generalized working and relevant examples for each tool.

2.1. Category 1: Using AI as solver tools

This category involves giving the AI tool a problem to solve, and they provide solutions. Solver tools are AI applications that can solve problems, answer queries, or perform computations across various domains. In mathematics, these solutions can process symbolic equations, provide step-by-step solutions, and even generate graphs to illustrate results. As a virtual tutor for multiple subject areas, language-based solver tools can interpret questions and produce concise or in-depth responses. Students benefit from instant clarification of complex topics, while educators can use solver outputs as additional examples to supplement instruction. Some solver tools are specialized, focusing on fields like coding, physics, chemistry, or engineering, thus catering to diverse academic needs. These tools employ machine learning or neural network models trained on large data sets to handle broad question types with varying complexity. This capability can help identify misconceptions when the solver includes explanations or breakdowns of the reasoning process. Solver tools are also valuable for generating practice problems, as they can dynamically create new questions and verify the correctness of solutions. However, relying solely on solver outputs might lead to overdependence, so educators often emphasize that AI should be used as a guide rather than a replacement for critical thinking. As these tools evolve, ensuring the reliability and correctness of answers remains paramount, especially in high-stakes academic environments.

Usage issues

Easy access to solver tools can tempt students to submit AI-generated answers without understanding the underlying concepts. While some solvers provide step-by-step results, many merely present final answers, depriving users of the deeper reasoning needed for meaningful learning. Even advanced models can produce incorrect solutions, especially in highly specialized or nuanced domains, leading to confusion or misinformation. Some solver tools operate as black boxes, so educators and learners cannot easily verify how results are generated or whether data sources are credible. Solver tools excel at generating direct answers, but they may not encourage creativity, exploration, or alternative approaches to problem-solving. Some tools store user-submitted queries and solutions, potentially exposing sensitive information about homework assignments, tests, or research.

2.2. Category 2: AI as a Multimedia Creation Tool

This category focuses on using AI to produce or assist in creating digital media, such as images, videos, animations, and audio. Many of these tools leverage generative AI algorithms to synthesize new content from user prompts or existing data sets. In Education, multimedia creation tools can help teachers develop engaging presentations, interactive lessons, and dynamic course materials. They often include editing features to enhance image quality or synchronize audio and video tracks automatically. Tools like AI-driven video generators allow instructors to create personalized video content without needing advanced filming or production skills. Some platforms integrate text-to-speech or voice cloning capabilities that let educators quickly add narration or dialogues in multiple accents and languages. These AI tools can also support student projects, encouraging creativity by letting learners produce audio-visual content for assignments. Multimedia creation tools increasingly incorporate intelligent feedback mechanisms, guiding users toward better design choices or coherent narratives. The rapid improvement of generative models means that media assets created through AI can closely resemble professionally produced work.

Despite their benefits, responsible use of these tools involves addressing potential copyright issues and verifying that generated content is accurate and ethical. By providing AI with personal details, such as the user’s background, location, or family context, it can generate a more personalized and relevant support resource. For example, if an individual’s background includes specific cultural or regional aspects, the AI can tailor advice, examples, or solutions that resonate with their experiences [

7]. When the AI tool can access details like specific interests, family dynamics, or emotional tones, it can craft more engaging and supportive resources. For instance, if the user has a baby, the AI could generate parenting tips or resources relevant to their child’s age and stage, ensuring that the advice is more relevant and practical for their unique situation [

7]. AI can be provided with details such as the user’s cultural background, location, or family dynamics. By knowing this information, the AI can tailor its responses to the user’s context, offering more relevant and meaningful suggestions or resources [

19]. AI can adapt its support to reflect the unique preferences and lifestyle of the user, whether it is adjusting the tone, style of communication, or providing suggestions that resonate with the user’s personal experiences, such as parenting tips or community engagement based on their social network [

20]. AI systems can adapt to changing user conditions and requirements, providing updated or modified support based on evolving circumstances, ensuring that the assistance remains relevant and valuable [

19]. While LLMs were the first foray of AI use for content generation, a recent upgrade to their capabilities involves models that now can generate media such as images, videos, and sound. Common frameworks for image generation include Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), and diffusion models (like Stable Diffusion and DALL-E). These models are trained on vast datasets of labeled images. For text-to-image tools like Midjourney or DALL-E, the model learns associations between words and visual patterns—for instance, linking "sunset" to warm colors, horizon lines, and silhouettes. Photos of the beach often exhibit a distinctive demarcation between the blue water and sandy beaches, prompting the AI to learn about these patterns and reuse them to answer future prompts. Neural networks can identify deeper image characteristics such as pixels, shapes, textures, saturation, and contextual elements. After this process, the generation model usually uses a technique such as diffusion models that add noise to an image in the form of random pixels during training and then reverse the process, gradually refining noise into coherent images based on the input prompt. These are then upgraded using techniques like Contrastive Language-Image Pre-training (CLIP) that uses a pair of NNs, one to understand images and one to understand text [

21].

Usage issues

Many AI-driven content generators are trained on large datasets without explicit attribution, raising questions about who owns the final product and whether usage may infringe on original creators’ rights. Sophisticated generative AI models can produce highly realistic images or videos (sometimes referred to as "deepfakes"), which can be used unethically to spread false information. The ease of manipulating visuals and audio raises issues around consent and the ethics of altering or fabricating people’s likenesses or voices. While AI tools can produce impressive outputs, the results may lack the nuance or authenticity that professional multimedia creators can offer, leading to subpar or overly generic materials. Users relying too heavily on AI for design decisions or creative direction may reduce their critical thinking and creativity capacity. Many platforms collect user data (including images or voice samples) to train and improve models, which can lead to concerns about storage, security, and consent.

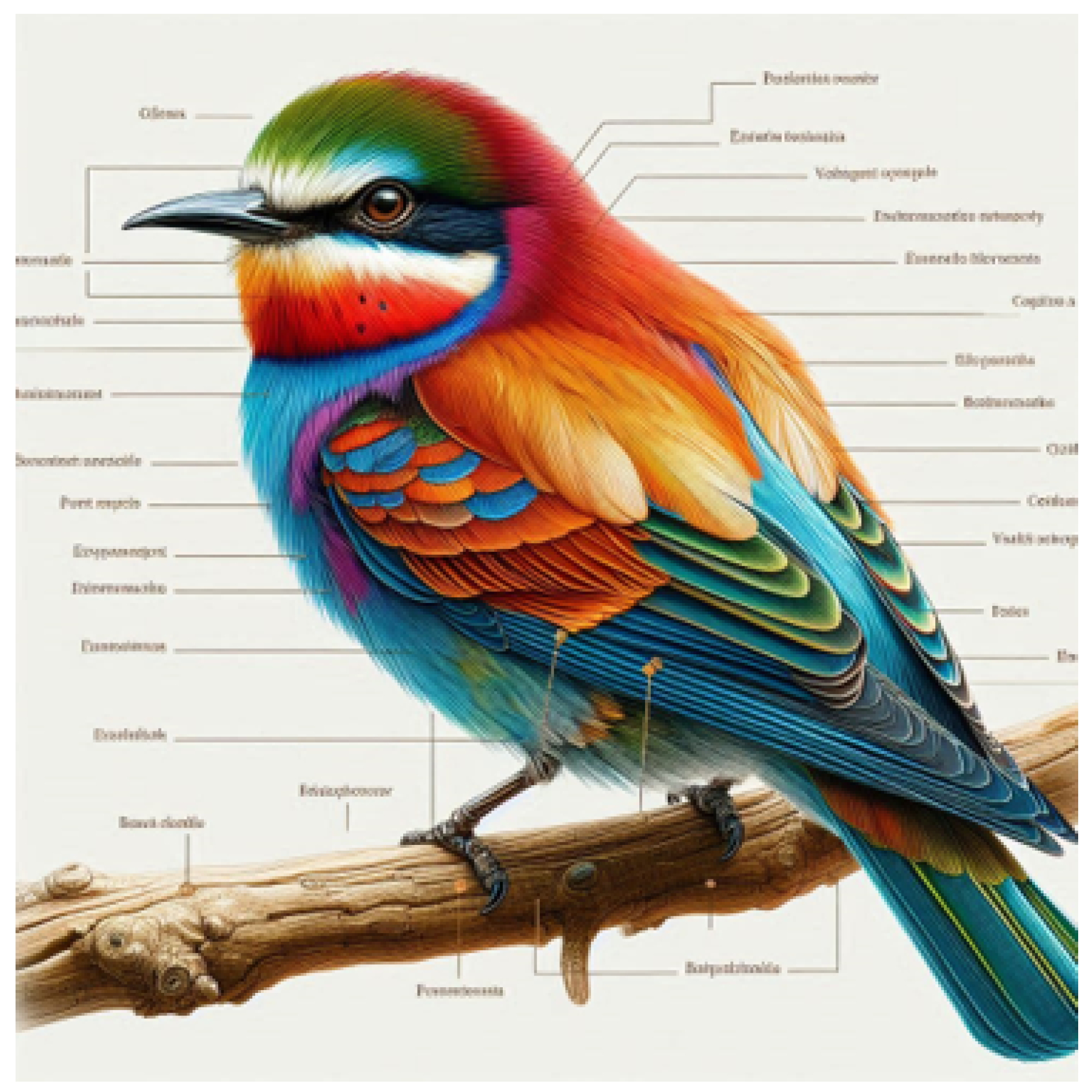

Some apparent signs in AI-generated images are anatomical, functional, and sociocultural implausibility and violation of physics rules. Additionally, AI tools with the primary function of image generation also struggle with generating clear, legible text within images as their training involves focusing on visual elements of the input figures and not understanding language.

Figure 2 shows one such image. The prompt given to the image generation model was to “generate a figure of a bird and clearly label all its body parts.” While minor issues with the bird’s anatomy, such as the arrangement and color combination of the plumage, can still be observed, the bird has been represented accurately. However, the model has generated gibberish text for body part labels. This demonstrates the deficiency of image generation algorithms when understanding grammar and language manipulation nuances.

AI image creation and manipulation tools have also affected research fields such as medicine, biology, chemistry, and computer science [

22]. Recently, an article with an AI-generated image of a mouse [

23] was published in a peer-reviewed journal, “Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology”. The image in question is anatomically inaccurate and displays extremely disproportionate body parts, in addition to issues in the label text. The paper and the image in question have been the subject of various articles that question the authenticity of the peer-review process and the risks of using AI-generated images in medicine and biology journals. The question remains as to how the image missed reviewer and editor detection in multiple rounds of review.

2.3. Category 3: AI as a Feedback & Rephrasing Tool

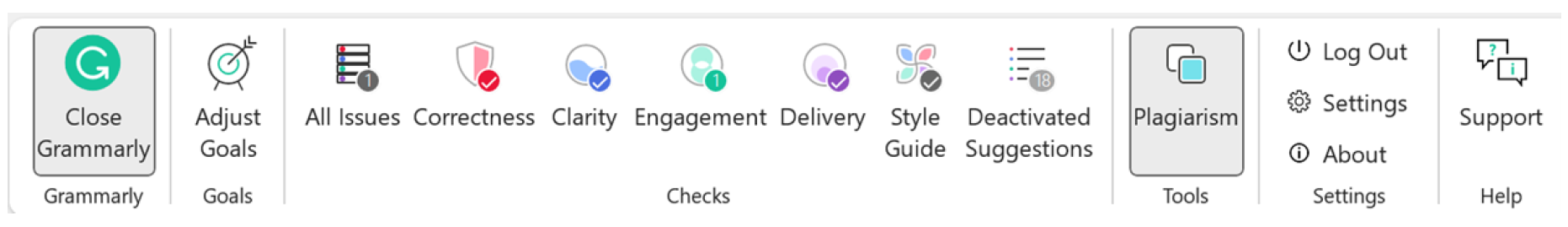

This category covers AI solutions that give users real-time suggestions on grammar, style, structure, or clarity in written content. Many systems use natural language processing to identify errors and propose corrections or improvements. They can offer multiple rephrasing options, enabling users to choose the version that best fits the intended tone or purpose. These tools are particularly useful in education, as students can receive immediate feedback on their writing rather than wait for manual grading. By highlighting specific issues in the text, AI-driven feedback fosters a more proactive approach to revision and learning. Advanced features sometimes include plagiarism detection, which assists students in maintaining originality in their work. Some tools also enhance contextual vocabulary, helping writers expand their word choices and refine expressions. Instructors can use these tools to streamline the grading process, focusing on higher-level feedback instead of minor language corrections. One such popular tool is Grammarly

[https://www.grammarly.com], which provides all the above features.

Figure 3 shows a screenshot of Grammarly’s word plug-in that examines content entered in the word processor and immediately suggests corrections and improvements to the language. Students who use these platforms often report improved confidence in their writing skills, as they see tangible progress over time. Nevertheless, responsible adoption requires balancing AI-driven feedback with human mentorship, ensuring learners develop genuine writing proficiency.

2.3.1. Using AI-enabled co-editors for IDE (Integrated Development Environments

AI-powered plug-ins in the IDE help with coding by predicting your next steps. They catch syntax mistakes early and can take care of repetitive tasks, helping developers focus on solving real problems [

24]. Modern Integrated Development Environments (IDEs) powered by AI use machine learning to identify potential bugs by detecting patterns in the code. These tools provide real-time suggestions for fixing code, which helps developers minimize debugging time [

25]. AI-enabled tools analyze code structure and identify redundant or inefficient algorithm patterns. They offer automated code and performance optimization recommendations, enhancing software maintainability and boosting performance while ensuring IT industry compliance and best practices [

26]. AI models generate comments and documentation. This automated documentation process ensures that existing code remains readable even as new features are introduced [

27]. Automated AI-based code review systems analyze coding patterns, enforce best practices, and highlight potential conflicts before merging code. These tools help maintain high-quality standards and ensure compliance with organizational coding guidelines by incorporating machine learning algorithms using built-in plug-ins in the IDE [

28]. AI-powered search capabilities in IDEs allow developers to find relevant code snippets for modules and libraries quickly. This process helps reduce the developer’s time searching for documentation or external resources, streamlining the development process[

29]. Developers can use AI-powered coding assistants using normal language queries to create complex regular expressions and SQL statements, which enables them to generate code snippets without manually writing complex logic. This feature is handy for beginners and helps to create prototypes by translating human instructions into executable code [

27]. AI-driven tools can automatically generate unit test cases for a given module by analyzing module functionalities and expected outputs, improving code accuracy. This reduces the manual effort required for writing test cases and ensures test coverage, leading to fewer defects in production [

30]. AI-driven IDEs can analyze code for security vulnerabilities using plug-ins like SONAR or SNYK to detect potential threats and suggest resolution strategies before deployment.

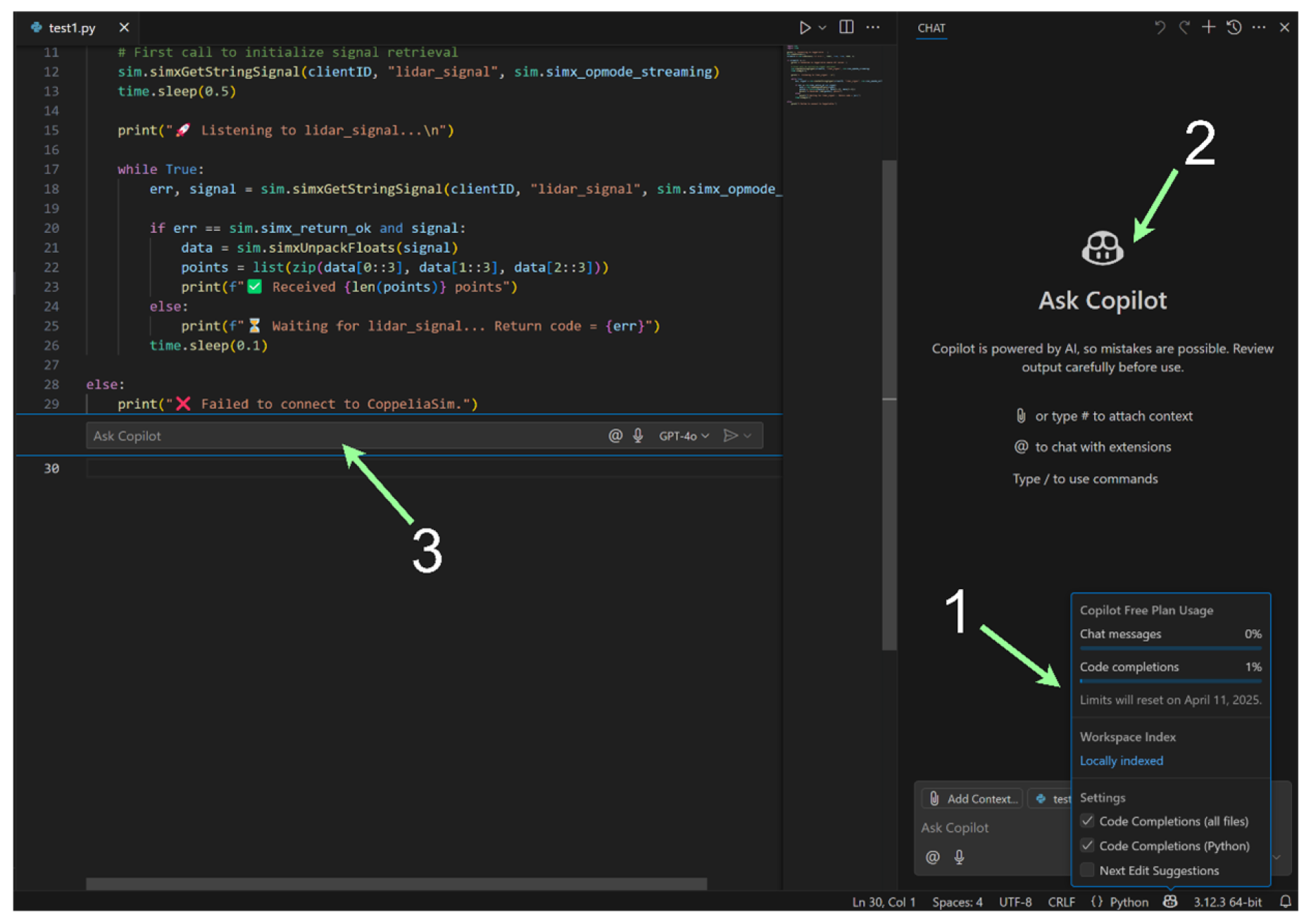

Figure 4 shows a screenshot of the Visual Studio IDE. The three numbered windows represent the availability of AI assistance to assist the coder. The in-code window labeled as (1) allows the coder to ask code-specific questions to the Copilot AI code tool. The tool can then make changes directly to the code. The dedicated chat window labeled as (2) shows a separate chat window where the user can ask additional questions to the AI tool, make changes to the code, ask for suggestions, improvements, and even discuss the addition of more functionality to the code. Label (3) shows the user the number of chat messages and code completion allowances available to the user. While free tiers offer limited uses per day/month, higher paid tiers may have larger or unlimited usage allowances.

These plug-ins can be manually configured to include and exclude rules as per organization standards. This approach increases code security by preventing vulnerabilities like SQL injection, buffer overflows, and unauthorized access [

31]. While sentence and paragraph rephrasing technically falls under category 2: Using AI as a content creation tool, we see this ability as a sub-feature of AI tools primarily used for grammar correction.

2.3.2. Using AI as a Personalized Tutor

AI can personalize lessons according to a student’s strengths, weaknesses, and pace of learning. Whether a student needs additional help to grasp a concept or they are looking for more advanced challenges, AI can cater to their requirements, ensuring they learn at a pace that works best for them. This makes it a versatile tool for diverse learners, helping everyone achieve their fullest potential in a way that fits their learning journey [

32]. One of the most significant advantages of AI-powered tutoring is its round-the-clock availability, unlike traditional methods often bound by fixed schedules. Students can access help whenever needed, whether at night or during their lunch break. Instant feedback, immediate explanations, and practice exercises ensure that learning never stops, making it easier for students to stay on track without time constraints or availability[

32]. AI makes it possible to provide personalized learning experiences to many students at once, a significant advantage in today’s classrooms. This scalability means that while students receive tailored content suited to their learning needs, teachers are freed from the logistical challenge of managing large groups.

The ability to reach so many learners simultaneously while addressing different learning paces and styles enhances the overall educational experience for all students involved [

33]. AI systems continuously track and analyze student performance, providing valuable insights into student progress. This data can highlight strengths and pinpoint areas needing further attention, allowing for more strategic and targeted teaching. By processing this data, AI can guide educators in making informed decisions about lesson planning and suggest resources to help students improve in specific areas[

33]. AI-driven learning platforms often incorporate gamified elements, interactive quizzes, and simulations to make learning more engaging and enjoyable. This approach helps students feel more invested in their learning process and increases motivation. With interactive tools and activities, students are encouraged to participate actively, which leads to a deeper understanding and retention of the material [

33]. AI can adjust the content delivery to fit their evolving needs by tracking a student’s progress. This ability to personalize the learning experience means that students are always presented with the right level of challenge, neither too easy nor too difficult, ensuring they remain engaged and motivated. Whether providing extra resources for areas where they struggle or offering advanced material to challenge them further, AI ensures the learning pathway aligns perfectly with each student’s unique journey [

29].

AI’s ability to analyze performance data over time helps educators see patterns in a student’s strengths and weaknesses. This data-driven approach allows teachers to adjust their strategies and curricula based on real insights, providing more effective interventions where needed. With AI, instruction can become more personalized and refined, ensuring students’ learning experiences are tailored to their progress [

29]. AI-powered learning platforms can provide personalized feedback and set up challenges that motivate and engage students. With gamified elements and progress rewards, students are encouraged to push themselves further and stay focused on their academic growth. This interactive, rewarding learning experience helps maintain a sense of accomplishment and excitement, ultimately driving continued learning and improvement [

29].

Automated question generation tools can analyze input data, such as textbooks, notes, or PDFs, to automatically generate multiple-choice, true/false, or short-answer questions. Some advanced tools use AI to create questions, replicating exam patterns [

34]. Additionally, many quiz-based tools use AI for creating learning content and generating feedback based on quizzes and exams. It can also adjust difficulty levels based on user performance. If a student struggles with specific topics, the tool generates more questions in those areas to ensure better understanding [

34].

These tools can improve practice exams by personalizing them with user information, such as incorporating the user’s name or family context into the questions and scenarios. For example, using first names can help create relatable scenarios or context-based questions with which the user can connect [

35]. Additionally, some tools emphasize the importance of integrating data about the user’s social or community environment. In that case, it can generate questions about community roles, family support, and emotional intelligence, which may be valuable for social studies or psychology practice exams [

35].

Usage concerns

When students or professionals rely too heavily on AI for writing support, they may not develop essential language, grammar, and critical editing skills. Additionally, AI-driven suggestions can occasionally misinterpret context and recommend incorrect or awkward phrasing despite advances. Underlying training data can contain cultural or linguistic biases, resulting in feedback skewed toward particular dialects, styles, or norms. Users often submit entire drafts or personal writing to AI tools, raising questions about data security and how the text is stored or analyzed. AI tools can inadvertently introduce borrowed phrases or unintentional plagiarism if they pull from large, publicly available data sets. Ideally, AI-driven feedback should complement human expertise; educators and editors still play a critical role in delivering contextual, nuanced guidance.

3. AI tools for the detection of AI use

The prevalence of AI tools and the ease of their access has prompted their widespread use by students to complete assignments for coursework. The growing concern among educators and the progression of natural development has promoted a new category of tools. These have been created specifically to detect the use of AI in submitted written text, particularly in submitted assignments at the school and university levels. These tools check if student assignments or papers in academic settings have been generated with the assistance of AI. These tools evaluate the writing style, structure, and content patterns to identify AI-generated work, helping to maintain academic integrity. (Evaluating the efficacy of AI content detection tools in differentiating between human and AI-generated text). A sub-category of tools can also analyze programming patterns, syntax, and logic structures to determine whether a human or an AI model wrote a code. These tools help ensure originality and maintain coding integrity in professional and academic settings. (Testing of detection tools for AI-generated text)

Initial tools were not AI-based; they worked more on specific rules and attempted to recognize signatures and AI behavior patterns. Eventually, these AI usage detection tools themselves were also AI-based, creating an AI police for AI scenarios. AI-generated content exhibited common characteristics in the generated content. These tools use various techniques, including predictability analysis, linguistic and styling patterns, AI fingerprinting, and watermarks left by the AI generation tools.

AI-generated text tends to be highly predictable, while human writing is more varied. Examining the variation in sentence structure and complexity is also a good indicator of AI use. Human writers naturally vary sentence length and style, while AI produces more uniform patterns. AI-generated text often lacks personal voice, emotion, and nuanced argumentation. There is a lack of personal experience backed by real-world details in the generated content. These tools examine word choice, sentence structure, and writing style to detect unnatural patterns. Some tools compare text against a database of AI-generated outputs from models like GPT, BERT, or others. They assess how likely a given sentence was produced by an AI model based on token probability. Some AI models embed detectable watermarks in text, allowing AI detectors to flag content as machine-generated. These watermarks may involve specific word frequency patterns or subtle changes in sentence structures. Detection tools can also be trained on large datasets containing human and AI-generated text. These models use deep learning techniques to identify patterns that distinguish AI-generated content from human writing.

Table 2 lists some of the popular AI detection tools available. While these tools can be practical, they are not foolproof. They may flag human-written text as AI-generated (false positives) or fail to detect sophisticated AI outputs (false negatives). There is a large set of concerns with the use of AI detection tools that have effectively created a new area of research [

36,

37,

38]. As AI models evolve, detection tools must continually improve to keep up with increasingly human-like text generation.

4. Broader and Unaddressed Concerns with AI

Despite significant excitement in the rapid and broad adoption of various AI models, this area is still relatively nascent compared to many other well-established technologies. Below, we identify several concerns that may have particularly significant implications in the context of educational applications of AI, including AI misinformation and AI guardrail abuse. These concerns emerge from a common underlying thread related to the halting problem in computer science. The complexity of this underlying issue warrants further consideration when exploring these concerns in academic contexts.

There are times when AI models will provide an answer with completely falsified and incorrect information, a phenomenon reported in the mainstream news [

34] and has emerged as a theme in published research. Many terms have referred to this phenomenon. However, it has commonly been described as AI hallucinations, occurring 3,747 times across 14 academic articles and databases over ten years [

39]. Despite the prevalence of this term, there are arguments to refer to the phenomena with more accurate naming, instead referring to it as AI Misinformation [

40,

41]. In educational contexts, such as universities, this can create issues with the quality of the knowledge that students are acquiring. These problems can negatively impact academic work quality and integrity, among other topics [

42].

Another concern that has emerged with AI models is that they can be used to generate information that may be unsafe or inappropriate in varying contexts, specifically regarding the safety of human users and societies. Given this problem, work has been done to generate "AI Guardrails," which seek to provide a filter that restricts access to such information by filtering the prompting inputs and the generated outputs [

43]. Despite this work, there are still common reports of being able to bypass or jailbreak against guardrails [

44,

45]. Underlying both of these phenomena is the halting problem [

46], which has led some researchers to go as far as to say that these problems will not go away [

47]. Given such a conclusion, future research should continue to explore the positive capabilities that AI can provide in educational contexts; however, it should do so with knowledge and awareness of some of the fundamental limitations.

References

- S. Ustymenko and A. Phadke, “Promise and challenges of generative ai in healthcare information systems,” Proceedings of the 2024 ACM Southeast Conference on ZZZ. 2024; 223–228. [CrossRef]

- A. Phadke, A. Hadimlioglu, T. Chu, and C. Sekharan, “Integrating large language models for uav control in simulated environments: A modular interaction approach,”. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:arXiv:2410.17602. [CrossRef]

- R. Bawack, S. Wamba, K. Carillo, and S. Akter, “Artificial intelligence in e-commerce: a bibliometric study and literature review,”. Electronic markets 2022, 32, 297–338. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- T. Ahmad, D. Zhang, C. Huang, H. Zhang, N. Dai, Y. Song, and H. Chen, “Artificial intelligence in sustainable energy industry: Status quo, challenges and opportunities,” Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 289, p. 12 5834, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Zayoud, S. Oueida, P. Awad, and S. Proceedings of the International Conference of Management and Industrial Engineering, 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. Motlagh, M. Khajavi, A. Sharifi, and M. Ahmadi, “The impact of artificial intelligence on the evolution of digital education: A comparative study of openai text generation tools including chatgpt, bing chat, bard, and ernie,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2309. arXiv 2023, arXiv:arXiv:2309.02029. [CrossRef]

- R. Sajja, Y. Sermet, M. Cikmaz, D. Cwiertny, and I. Demir, “Artificial intelligence-enabled intelligent assistant for personalized and adaptive learning in higher education,” Information, vol. 2024; 15. [CrossRef]

- J. H. von Garrel and H. O. Mayer, “A smart decision support system for engineering education based on an ensemble learning approach,” Smart Learning Environments, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 1–28, 2023.

- L. Labadze, M. L. Labadze, M. Grigolia, and L. Machaidze, “Role of ai chatbots in education: systematic literature review,” International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, vol. 2023; 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, N. My Duyen, N. Khoa, and N. Dien, “Perceptions of university students on using quizlet in self-study,”. TEM Journal, pp. – 2023, 1706–1712. [CrossRef]

- H. Jian, “Effectiveness of chatgpt in english teaching and research writing at college level: Evidence from china,” Computer Assisted Language Learning. 2023; 1–25. [CrossRef]

- H. Aljuaid, “The impact of artificial intelligence tools on academic writing instruction in higher education: A systematic review,” Arab World English Journal, vol. 1, pp. 2024; 55. [CrossRef]

- M. Khalifa and M. Albadawy, “Using artificial intelligence in academic writing and research: An essential productivity tool,” Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine Update. 2024; 5. [CrossRef]

- S. Wang, F. Wang, Z. Zhu, J. Wang, T. Tran, and Z. Du, “Artificial intelligence in education: A systematic literature review,” Expert Systems with Applications. 2024; 252. [CrossRef]

- C. Yeung, J. Yu, K. Cheung, T. Wong, C. Chan, K. Wong, and K. Fujii, “A zero-shot llm framework for automatic assignment grading in higher education,”. arXiv 2025, arXiv:arXiv:2501.14305. [CrossRef]

- G. Kestin, K. Miller, A. Klales, T. Milbourne, and G. Ponti, “Ai tutoring outperforms active learning,”. arXiv preprint arXiv:rs.3.rs-4243877/v1, 4243; v1, arXiv:rs.3. [CrossRef]

- E. Evangelista, “Ensuring academic integrity in the age of chatgpt: Rethinking exam design, assessment strategies, and ethical ai policies in higher education,” Contemporary Educational Technology. 2025; 17. [CrossRef]

- R. Praba and S. Sanjai, “Ai-powered interactive learning platforms for modern education,” International Journal of Scientific Research in Computer Science, Engineering and Information Technology, vol. 11, pp. 1687– 1692, 2025. [CrossRef]

- J. Sreerama and G. Krishnamoorthy, “Ethical considerations in ai addressing bias and fairness in machine learning models,” Journal of Knowledge Learning and Science Technology, vol. 1. 2022; 130–138. [CrossRef]

- R. Luckin, “Towards artificial intelligence-based assessment systems,”. Nature Human Behaviour, vol. 1, p. 0028, 2017. [CrossRef]

- H. 0 2746, 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. Dash, V. Mehta, and P. Kharat, “We are entering a new era of problems: Ai-generated images in research manuscripts,”. Oral Oncology Reports, vol. 10, p. 10 0289, 2024. [CrossRef]

- F. Landymore, “Scientific article with insane ai-generated images somehow passes peer review,” Futurism, 2024, https://futurism.com/the-byte/scientific-article-ai-generated-images.

- D. Zhang, “Ai-powered coding tools: A study of advancements, challenges, and future directions,”. Science and Technology of Engineering, Chemistry and Environmental Protection, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Staron, S. Abrahão, G. Gay, and A. Serebrenik, “Testing, debugging, and log analysis with modern ai tools,” IEEE Software, vol. 41, 2024; 99–102. [CrossRef]

- A. Nanda, “Revolutionizing software development with ai-based code refactoring techniques,” International Journal of Scientific Research & Engineering Trends. 2023; 9. [CrossRef]

- K. Kumar, M. K. Kumar, M. Syed, S. Bhargava, L. Mohakud, M. Serajuddin, and M. Lourens, “Natural language processing: Bridging the gap between human language and machine understanding,” in Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Trends in Quantum Computing and Emerging Business Technologies, 2024, pp. 6. [CrossRef]

- H. Lal and G. Pahwa, “Code review analysis of software system using machine learning techniques,” in Proceedings of the 2017 11th International Conference on Intelligent Systems and Control (ISCO). 2017; 13, 8–13. [CrossRef]

- Y. Almeida, D. Albuquerque, E. Filho, F. Muniz, K. de Farias Santos, M. Perkusich, H. Almeida, and A. Perkusich, “Aicodereview: Advancing code quality with ai-enhanced reviews,” SoftwareX. 2024; 26. [CrossRef]

- M. Islam, F. Khan, S. Alam, and M. Hasan, “Artificial intelligence in software testing: A systematic review,” in Proceedings of the TENCON 2023 - 2023 IEEE Region 10 Conference (TENCON), 2023. 524–529. [CrossRef]

- R. Kaur, D. R. Kaur, D. Gabrijelčič, and T. Klobučar, “Artificial intelligence for cybersecurity: Literature review and future research directions,” Information Fusion, vol. 2023; 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Pularia and S. Jacoba, “Research insights on the ethical aspects of ai-based smart learning environments: Review on the confluence of academic enterprises and ai,”. 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. Łuczaka, A. Greńczuka, I. Chomiak-Orsaa, and E. Piwoni-Krzeszowskaa, “Enhancing academic tutoring with ai – a conceptual framework,”. Procedia Computer Science 2024, 246, 5555–5564. [CrossRef]

- R. McGee, “Creating a quiz using artificial intelligence: An experimental study,”. A: McGee, “Creating a quiz using artificial intelligence, 2024. [CrossRef]

- N.-T. Le, T. N.-T. Le, T. Kojiri, and N. Pinkwart, “Automatic question generation for educational applications – the state of art,” in Advanced Computational Methods for Knowledge Engineering, ser. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing. Springer, 2014, pp. 325–338.

- S. Kar, T. Bansal, S. Modi, and A. Singh, “How sensitive are the free ai-detector tools in detecting ai-generated texts? a comparison of popular ai-detector tools,”. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine 7934, 0, 0253717624124. [CrossRef]

- M. Coccoli and G. Patanè, “Ai vs. ai: The detection game,” in Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 8th Forum on Research and Technologies for Society and Industry Innovation (RTSI), 2024. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- G. Gritsai, A. G. Gritsai, A. Voznyuk, A. Grabovoy, and Y. Chekhovich, “Are ai detectors good enough? 2024; arXiv:2410.14677. [Google Scholar]

- Y. Sun, D. Sheng, Z. Zhou, and Y. Wu, “Ai hallucination: towards a comprehensive classification of distorted information in artificial intelligence-generated content,”. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 2024, 11, 1278. [CrossRef]

- S. Monteith, T. Glenn, J. Geddes, P. Whybrow, E. Achtyes, and M. Bauer, “Artificial intelligence and increasing misinformation,” The British Journal of Psychiatry, vol. 224. 2024, 224, 33–35. [CrossRef]

- N. Maleki, B. N. Maleki, B. Padmanabhan, and K. Dutta, “Ai hallucinations: A misnomer worth clarifying,” in Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Conference on Artificial Intelligence (CAI), 2024. 133–138. [CrossRef]

- H. Kamel, “Understanding the impact of ai hallucinations on the university community,”. 2024; 111–134. [CrossRef]

- Y. Dong, R. Mu, G. Jin, Y. Qi, J. Hu, X. Zhao, J. Meng, W. Ruan, and X. Huang, “Building guardrails for large language models,” 2024, arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.01822. arXiv:2402.01822.

- H. Jin, A. Zhou, J. Menke, and H. Wang, “Jailbreaking large language models against moderation guardrails via cipher characters,” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 37, pp. 59 408–59 435, 2024.

- X. Shen, Z. Chen, M. Backes, Y. Shen, and Y. Zhang, “"do anything now”: Characterizing and evaluating in-the-wild jailbreak prompts on large language models,” 2024, uRL https://arxiv.org/abs/2308.03825.

- N. Kremer-Herman, A. Gupta, and E. Severson, “Blueprints for machine ethics: A digital terrarium for socio-ethical artificial agent decisionmaking,”. IEEE Access, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Banerjee, A. Agarwal, and S. Singla, “Llms will always hallucinate, and we need to live with this,”. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:arXiv:2409.05746.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).