Submitted:

19 April 2025

Posted:

21 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

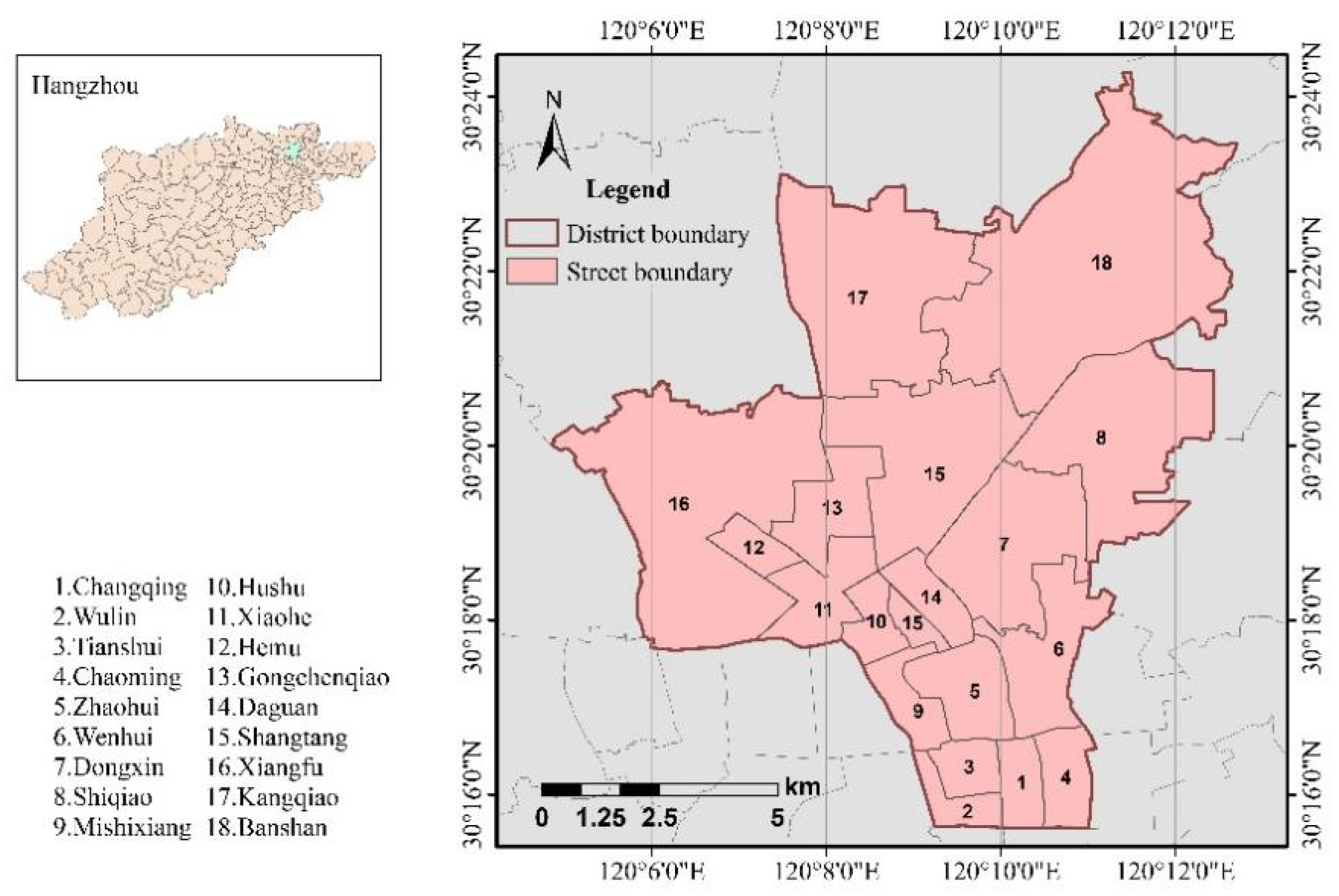

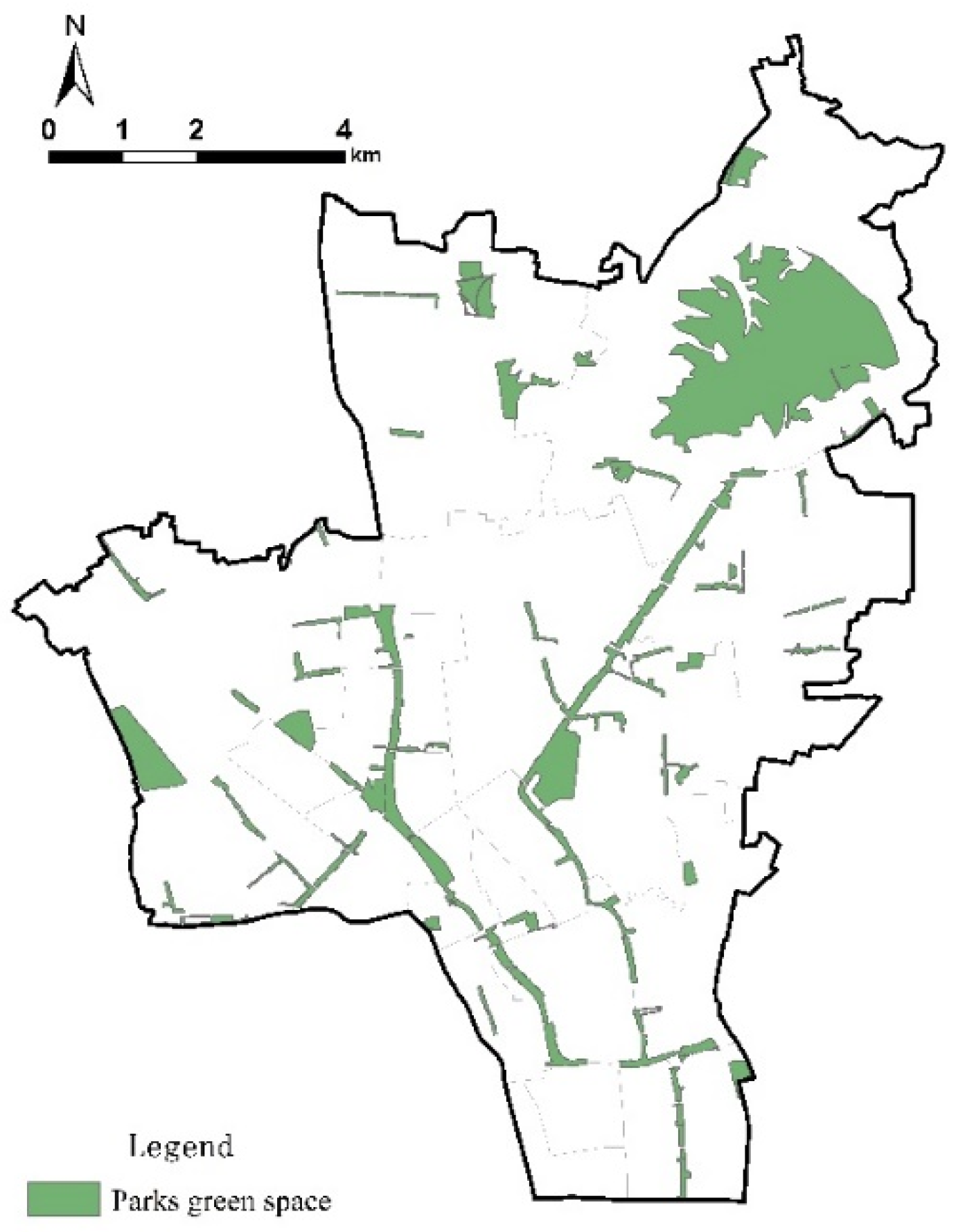

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Signaling Data and Processing

- Leisure time categorization: Weekdays vs weekends;

- Arrival time intervals: 6:00–8:00, 8:00–12:00, 12:00–16:00, 16:00–18:00, 18:00–20:00, 20:00–22:00 (six intervals);

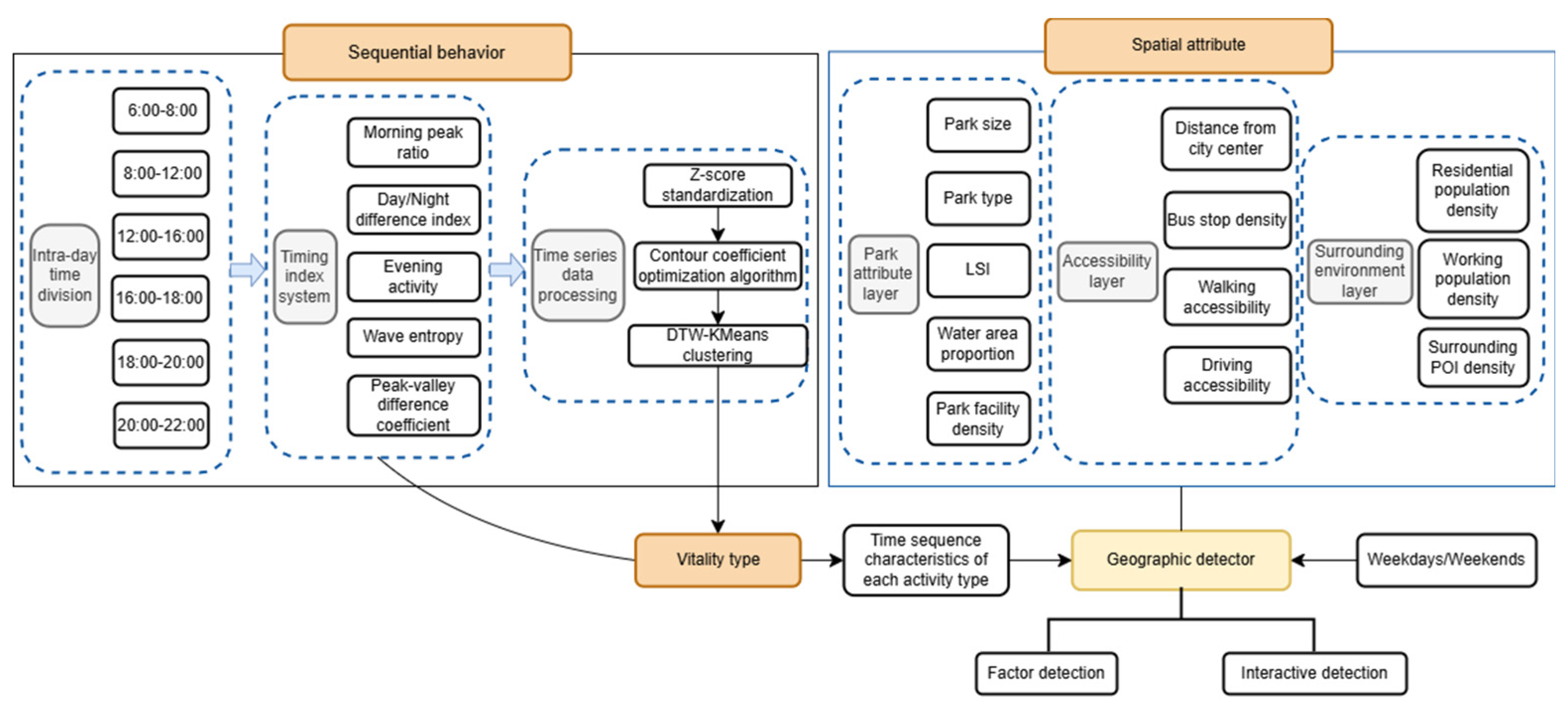

2.3. Integrated Analytical Framework of "Temporal Behavior-Spatial Attribute-Vitality Typology"

- Park-specific attributes: Including park area, park type, landscape morphology index, water area ratio, and facility density;

- Accessibility attributes: Comprising distance to city center, bus stop density, walking accessibility, and driving accessibility;

- Surrounding environment attributes: Encompassing residential population density, employment density, and density of park-related services/facilities.

2.3.1. Constructing the Temporal Feature Matrix of Recreational Behavior

- Morning Peak Ratio (Mmor) : Quantifies vitality intensity during the morning commute (6:00–8:00). Calculated as the ratio of hourly average visitation volume during 6:00–8:00 to the full-day average;

- Day-Night Difference Coefficient (MDN) : Reflects the imbalance between daytime (8:00–16:00) and evening (16:00–22:00) vitality distributions, measured by the ratio of visitation volumes between these periods;

- Evening Activity Level (Meve): Represents the contribution of 18:00–22:00 vitality as the proportion of total visits during this period relative to the full day;

- Fluctuation Entropy (H) : Uses Shannon entropy to measure the disorderliness of visitor flow fluctuations, where higher entropy indicates more random vitality distributions. Measuring the irregularity of hourly visitation volume distributions. Calculated as Shannon entropy of hourly visit distributions;

- Peak-Valley Difference Coefficient (PVR) : Core index to measure the fluctuation intensity of park population flow. Quantifies the amplitude of daily vitality extremes as the ratio of maximum to minimum hourly average visitation volumes.

2.3.2. DTW-based K-Means Clustering

- Temporal Data Preprocessing: Daily visitation volume data for 59 parks were standardized using Z-score normalization to eliminate dimensional differences, constructing a standardized temporal matrix X ∈ R59×6.

- DTW distance replaced traditional Euclidean distance to elastically align temporal waveforms and resolve interference from phase shifts in similarity measurements. The DTW distance is calculated as:

- 3.

- Cluster Number Determination: Cluster quality was evaluated using the Silhouette Score, with grid search identifying the optimal cluster number K=3. The Silhouette Score is calculated as:

- 4.

- Model Training and Optimization: DTW-KMeans was implemented using Python’s tslearn library with parameters: maximum iterations T=100, convergence threshold , and three random initializations to avoid local optima. The algorithm iteratively optimizes cluster centroids and sample assignments to minimize the objective function:

- 5.

- Result Validation: Intra-cluster compactness was validated through intra-cluster average DTW distance (< 60 visitors/hour) and inter-cluster separation (> 220 visitors/hour). Cluster structure significance was confirmed using permutation tests (p < 0.01).

2.3.3. Geographical Detector Model – Indicator Determination and Feature Extraction

- Park-specific Attributes;

- 2.

- Accessibility Features;

- 3.

- Surrounding Environmental Attributes;

3. Results

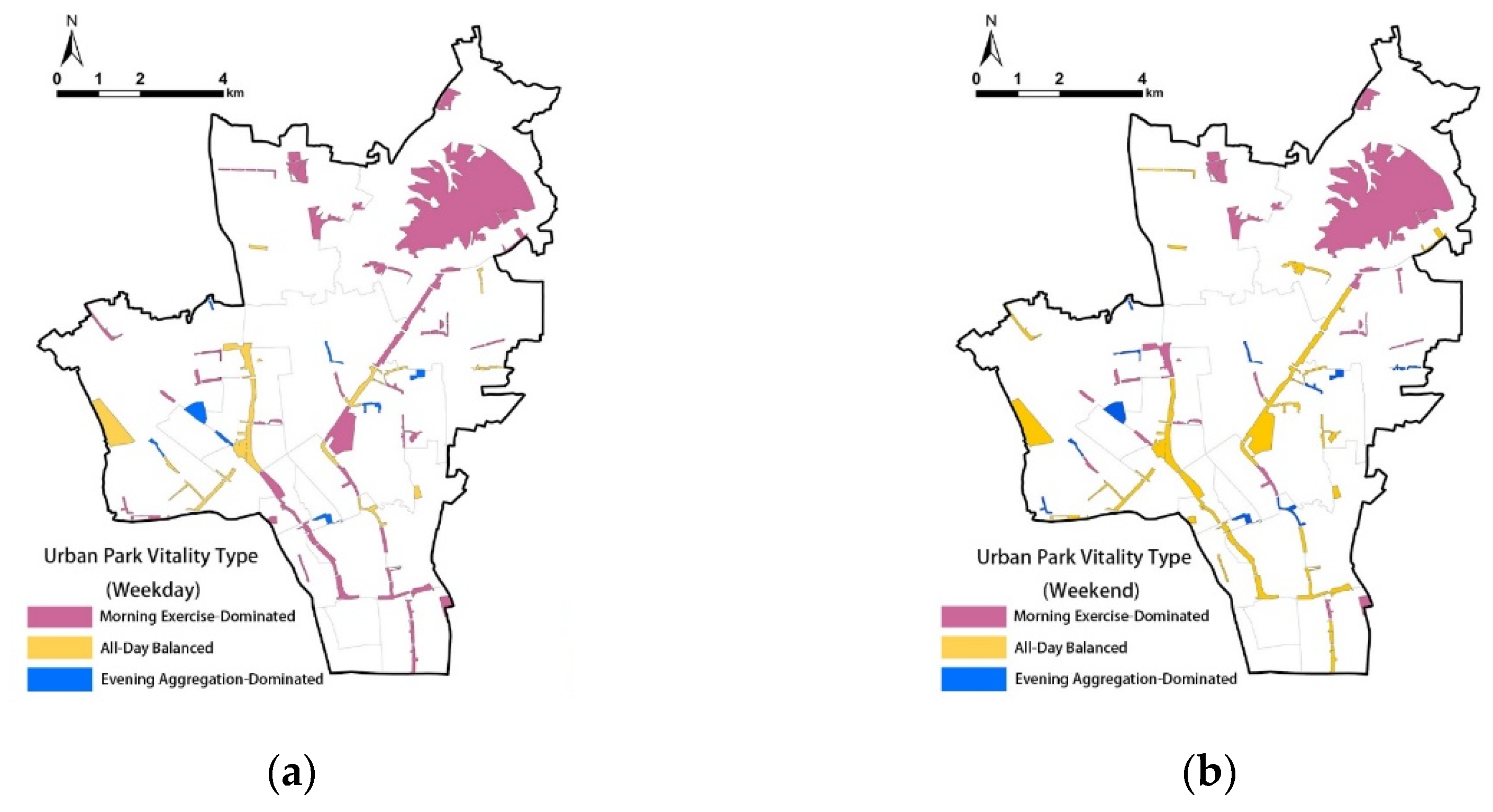

3.1. Urban Park Vitality Typologies

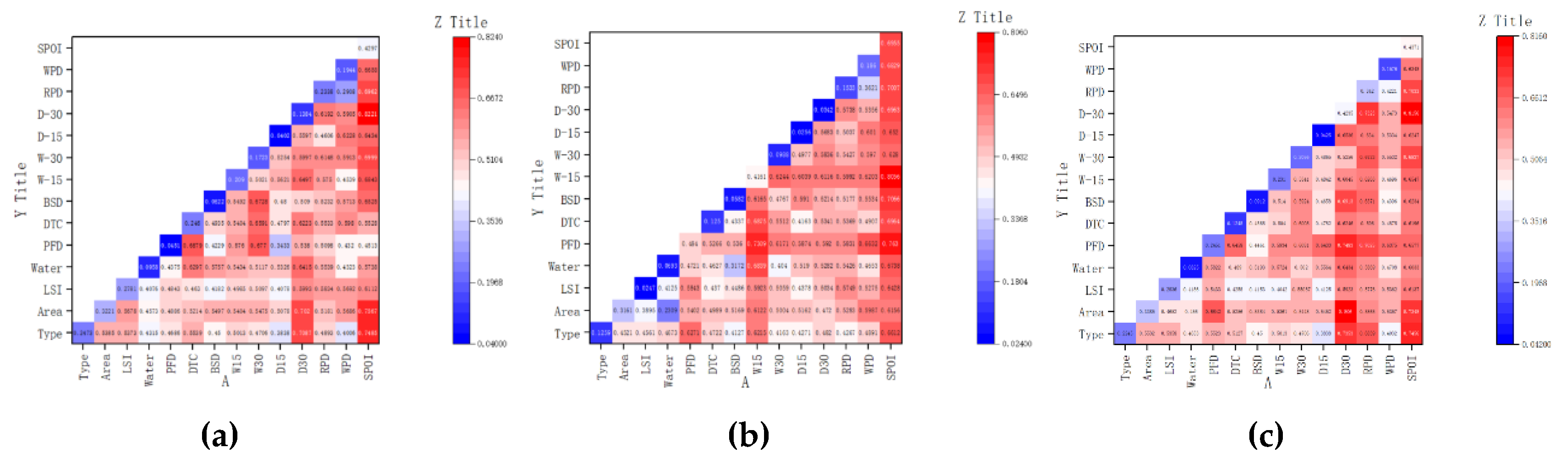

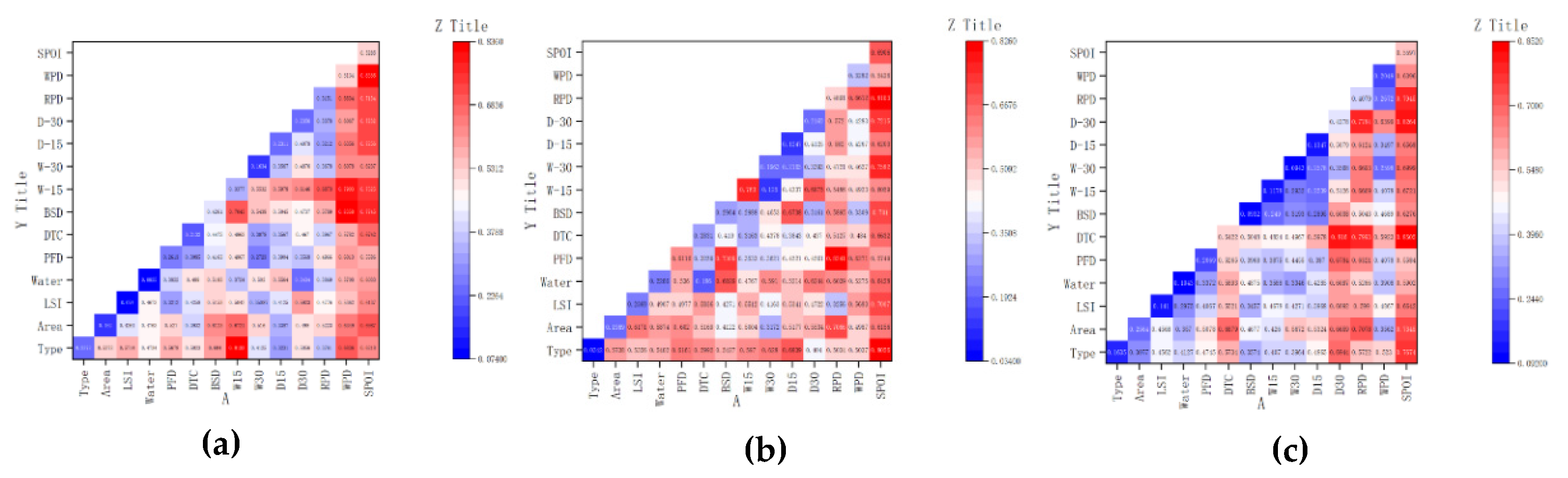

3.2. Results of Geographical Detector Model

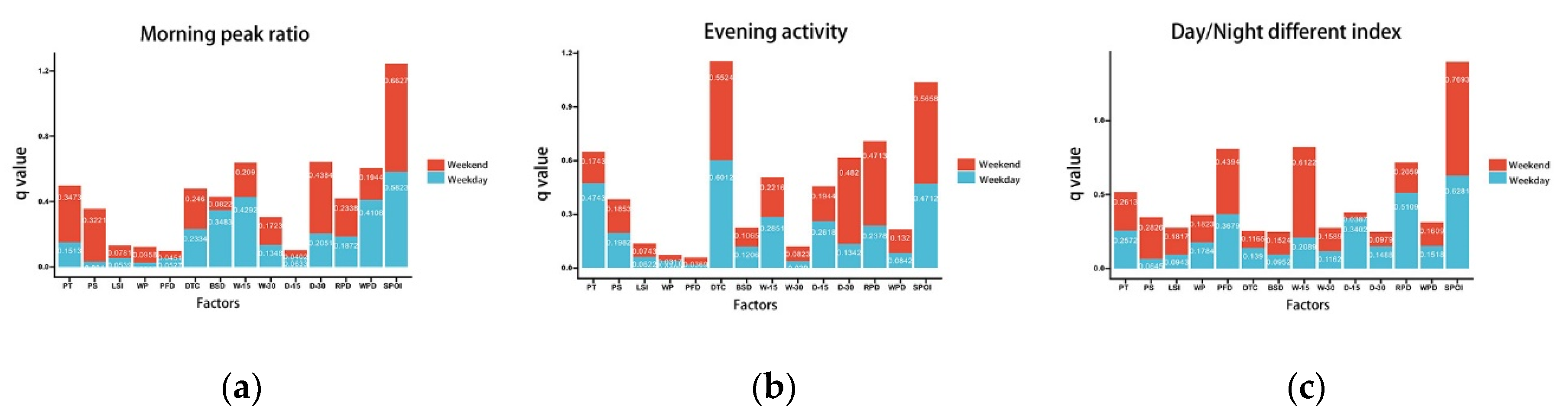

3.2.1. Main Influencing Factors on Weekends

3.2.2. Main Influencing Factors on Weekdays

3.3. Influencing Factors of Vitality Types in Different Time Periods

4. Discussion

- "Morning Exercise-Dominated" parks: Addressing temporal fragmentation to unlock the temporal value of suburban parks.

- Innovative Maintenance Management:

- Planning Strategies:

- Synergy with Surrounding Elements:

- 2.

- "All-Day Balanced" parks (e.g., Xiaohezhi Street Greenway, Ying’ergang Greenway, green spaces around West Lake Cultural Square): Reconfiguring urban functional networks to create sustainable vitality hubs.

- Upgraded Maintenance Management:

- Planning Strategies:

- Synergy with Surrounding Elements:

- 3.

- "Evening Aggregation-Dominated" parks (e.g., Mishixiang Cultural Square): Precisely responding to residential needs to build inclusive vitality units.

- Innovative Maintenance Management:

- Planning Strategies:

- Synergy with Surrounding Elements:

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UN-Habitat - a Better Urban Future | UN-Habitat. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/ (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Healey, P. Urban Complexity and Spatial Strategies: Towards a Relational Planning for Our Times; Routledge: London, 2006; ISBN 978-0-203-09941-4. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Liu, B.; Li, S.; Jiang, B.; Wang, X.; Lu, W.; Hu, Y.; Wen, T.; Feng, Y. Actual Supply-Demand of the Urban Green Space in a Populous and Highly Developed City: Evidence Based on Mobile Signal Data in Guangzhou. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 169, 112839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haselsteiner, E.; Smetschka, B.; Remesch, A.; Gaube, V. Time-Use Patterns and Sustainable Urban Form: A Case Study to Explore Potential Links. Sustainability 2015, 7, 8022–8050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Making Strategic Spatial Plans; Healey, P., Ed.; Routledge: London, 2006; ISBN 978-0-203-45150-2. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Yu, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Chen, C.; Wan, Y.; Zhao, B.; Vejre, H. Evaluating the Disparities in Urban Green Space Provision in Communities with Diverse Built Environments: The Case of a Rapidly Urbanizing Chinese City. Build. Environ. 2020, 183, 107170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y; Lu, H. Research on recreation rules and spatial correlation of community parks based on multi-source data: A case study of Shanghai. Landsc. Archit. 2024, 31, 32–40.

- de Jalon, S.G.; Chiabai, A.; Quiroga, S.; Suarez, C.; Scasny, M.; Maca, V.; Zverinova, I.; Marques, S.; Craveiro, D.; Taylor, T. The Influence of Urban Greenspaces on People’s Physical Activity: A Population-Based Study in Spain. Landsc. URBAN Plan. 2021, 215, 104229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L; Yang, S. A preliminary study on the behavior characteristics of residents' activities and the correlation of spatial layout in community public space: A case study of Suzhou Park Neighborhood Center. Huazhong Archit. 2018, 82–86. [CrossRef]

- Ekkel, E.D.; de Vries, S. Nearby Green Space and Human Health: Evaluating Accessibility Metrics. Landsc. URBAN Plan. 2017, 157, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. Factors influencing the activity volume of urban community public space. J. Shenzhen Univ. Sci. Eng. 2016, 33, 180–187. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, Z. The Study of Quantification Method on Urban Greenspace Configuration. Doctoral dissertation, Nanjing University, Nanjing, 2011.

- Kimpton, A. A Spatial Analytic Approach for Classifying Greenspace and Comparing Greenspace Social Equity. Appl. Geogr. 2017, 82, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, W.H. The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces. STPH, 2016; ISBN 978-7-5327-7051-9.

- Park, K.; Ewing, R. The Usability of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) for Measuring Park-Based Physical Activity. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 167, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X; Xu J; Liu, X; Zhu, X. Study on physical activity and spatial distribution of urban parks in winter based on UAV observation: A case study of four parks in Harbin. CLA 2019, 35, 40–45. [CrossRef]

- Matisziw, T.C.; Nilon, C.H.; Wilhelm Stanis, S.A.; LeMaster, J.W.; McElroy, J.A.; Sayers, S.P. The Right Space at the Right Time: The Relationship between Children’s Physical Activity and Land Use/Land Cover. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 151, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reades, J.; Calabrese, F.; Sevtsuk, A.; Ratti, C. Cellular Census: Explorations in Urban Data Collection. IEEE Pervasive Comput. 2007, 6, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B; Zhen, F; Zhang, H. Study on dynamic change and regionalization of urban activity time based on check-in data. Scient. Geogr. Sin. 2015, 35, 151–160. [CrossRef]

- He, X; Yuan, Q; Lu, J; Li, G. A study on the spatio-temporal patterns and influencing mechanisms of foreign tourists' visits to urban parks: A case study of Guangzhou. S. Archit. 2024, 32–43.

- Niu, X; Kang, N. Spatial and temporal characteristics and influencing factors of tourist activities in Shanghai Country Parks: a study based on mobile phone signaling data. CLA 2021, 37, 39–43. [CrossRef]

- Dong, W. Spatial and temporal vitality characteristics and influencing factors of urban parks based on multi-source data: A case study of Yanqing District, Beijing. C. Constr. Metal Struct. 2023, 141–143, 149. [CrossRef]

- Long, F; Shi, L; Peng, Z; Yang, J; Zhang, S. Urban park service evaluation based on mobile signaling data. Urban Probl. 2018, 88–92. [CrossRef]

- Fang, J; Liu, S; Wang, D; Zhang, Y. Analysis of supply and demand service of Shanghai urban park based on mobile signaling data. Landsc. Archit. 2017, 35–40. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H; Hu, Y; Liang, F. Study on recreational behavior of street side green space users in summer in Binhai New Area, Tianjin. J Beijing Univ Agric. 2013, 28, 74–77.

- Yang, G. Research on recreation behavior in lake-type park based on behavioral observation. Archit. & Cult. 2018, 171–172.

- Yang, B; Yin, M; Zheng, S; Gao, R. Study on day and night recreation activity of high-density urban park green space based on mobile phone signaling and POI big data: A case study of typical park green space in Shanghai. Landsc. Archit. 2023, 40, 35–42.

- Rizwan, M.; Wan, W.; Cervantes, O.; Gwiazdzinski, L. Using Location-Based Social Media Data to Observe Check-In Behavior and Gender Difference: Bringing Weibo Data into Play. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2018, 7, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Huang, B.; Cai, J.; Chen, B. Dynamic Assessments of Population Exposure to Urban Greenspace Using Multi-Source Big Data. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 634, 1315–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Liu, C. Exploring Factors Affecting Urban Park Use from a Geospatial Perspective: A Big Data Study in Fuzhou, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2023, 20, 4237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J; Zhao, Y; Zhong, K; Ruan, H; Sun, C. Correlation analysis of temperature and NDVI concentration density based on geographical weighting and least square linear regression model. Trop. Geogr. 2017, 37, 269–276. [CrossRef]

- Hu, X; Li, T. Spatial and temporal distribution characteristics of urban park population based on vitality perspective: A case study of Suzhou Central City. Landsc. Archit. 2022, 39, 90–97.

- Tao, Z; Ding, J; Wang, L; Chen, D. A spatial-temporal heterogeneity study on the influence of urban park characteristics on recreation vitality. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2023, 39, 108–113. [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Qiu, H. Exploring Affecting Factors of Park Use Based on Multisource Big Data: Case Study in Wuhan, China. J. URBAN Plan. Dev. 2021, 147, 05020037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X; Yuan, Q; Lu, J; Li, G. Spatial and temporal activity patterns and planning strategies of urban park population in Guangzhou based on multi-source big data. Mod. Urban Res. 2025, 7–14.

- Hägerstraand, T. WHAT ABOUT PEOPLE IN REGIONAL SCIENCE? Pap. Reg. Sci. 1970, 24, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J; Xu, C. Geodetectors: Principles and prospects. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2017, 72, 116–134.

- Li, F.; Yao, N.; Liu, D.; Liu, W.; Sun, Y.; Cheng, W.; Li, X.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Y. Explore the Recreational Service of Large Urban Parks and Its Influential Factors in City Clusters – Experiments from 11 Cities in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 314, 128261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Gao, W.; Wang, R.Y.; Li, Y.; Tu, W. Emerging Social Media Data on Measuring Urban Park Use. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 31, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, F.; Zhang, L. Using Multi-Source Big Data to Understand the Factors Affecting Urban Park Use in Wuhan. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 43, 126367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dade, M.C.; Mitchell, M.G.E.; Brown, G.; Rhodes, J.R. The Effects of Urban Greenspace Characteristics and Socio-Demographics Vary among Cultural Ecosystem Services. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 49, 126641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Baggethun, E.; Barton, D.N. Classifying and Valuing Ecosystem Services for Urban Planning. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 86, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Q.; Wu, C.; Luo, G. Research on flexible land use planning. TCSAE. 2006, 65–68. [Google Scholar]

- Bolund, P.; Hunhammar, S. Ecosystem Services in Urban Areas. Ecol. Econ. 1999, 29, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Work Summary and Work Plan for 2022 and 2023 of the Municipal Bureau of Planning and Natural Resources -- Public Disclosure of Implementation Status. Available online: https://www.sz.gov.cn/szzt2010/wgkzl/jggk/lsqkgk/content/post_10568888.html (accessed on 14 April 2025).

| Variables | Description | Unit | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Park-specific Attributes | PS | Park size | Ha | |

| PT | Park type | - | Comprehensive park(=7) Specialized park(=5) Community park(=3) Mini park(=1) |

|

| (LSI) Landscape shape index |

The landscape shape index | - | LSI=2 Si represents the area of the urban park I in hectares and Ci signifies the circumference of the park I in meters. |

|

| WP | Water proportion to the urban park area | water area / park area | ||

| (PFD) Park facilities density |

The density of park service, such as playgrounds, themed plazas, lounge corridors, restaurants, shops, toilets, and parking lots | n/ha | POI screening + map comparison | |

| Accessibility Features | (DTC) Distance to the city center |

The distance from the park to the city center | m | Euclidean distance from the city center (Wulin Square) to an urban park centroid |

| (BSD) Bus station density |

The density of the bus stations within buffer areas of each park. | n/ha | Buffer analysis was conducted based on data from AMAP POI(accessed on Apirl,2023) | |

| (W-15) Walking in an isochronous circle (15min) |

Area accessibility from walking for 15 min in non-peak hours on weekdays from the park | m2 | Used real-time path planning tool to obtain a grid file describing the time distance to the park. | |

| (W-30) Walking in an isochronous circle (30min) |

Area accessibility from walking for 30 min in non-peak hours on weekdays from the park | m2 | Used real-time path planning tool to obtain a grid file describing the time distance to the park. | |

| (D-15) Driving in an isochronous circle (15min) |

Area accessibility from driving for 15 min in non-peak hours on weekdays from the park | m2 | Used real-time path planning tool to obtain a grid file describing the time distance to the park. | |

| (D-30) Driving in an isochronous circle (30min) |

Area accessibility from driving for 30 min in non-peak hours on weekdays from the park | m2 | Used real-time path planning tool to obtain a grid file describing the time distance to the park. | |

| Surroundings Environmental Attributes | (RPD) Residential population density |

The density of the residential population within the buffer areas of each park | Population/ha | Buffer analysis was conducted based on mobile phone signaling data |

| (WPD) Working population density |

The density of the working population within the buffer areas of each park | Population/ha | Buffer analysis was conducted based on mobile phone signaling data | |

| SPOI | The density of surrounding services and POI in the buffer areas of each park | n/ha | Buffer analysis was conducted based on data from AMAP in 2023 |

| (A) Morning peak ratio | ||||||||||||||

| Factor | PT | PS | LSI | WP | PFD | DTC | BSD | W-15 | W-30 | D-15 | D-30 | RPD | WPD | SPOI |

| q statistic | 0.3473 | 0.3221 | 0.0781 | 0.0958 | 0.0451 | 0.2460 | 0.0822 | 0.2090 | 0.1723 | 0.0402 | 0.4384 | 0.2338 | 0.1944 | 0.6627 |

| p value | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.26 | 0.57 | 0.69 | 0.40 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.10 | 0.00 |

| (B) Evening activity | ||||||||||||||

| Factor | Type | Area | LSI | WP | PFD | DTC | BSD | W-15 | W-30 | D-15 | D-30 | RPD | WPD | SPOI |

| q statistic | 0.2613 | 0.2826 | 0.1817 | 0.1823 | 0.4394 | 0.1165 | 0.1524 | 0.6122 | 0.1589 | 0.0387 | 0.0979 | 0.2059 | 0.1609 | 0.7693 |

| p value | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.18 | 0.82 | 0.04 | 0.34 | 0.66 | 0.00 | 0.22 | 0.13 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.17 | 0.01 |

| (C) Day/Night difference index | ||||||||||||||

| Factor | Type | Area | LSI | WP | PFD | DTC | BSD | W-15 | W-30 | D-15 | D-30 | RPD | WPD | SPOI |

| q statistic | 0.1743 | 0.1853 | 0.0743 | 0.0317 | 0.0369 | 0.5524 | 0.1065 | 0.2216 | 0.0823 | 0.1944 | 0.4820 | 0.4713 | 0.1320 | 0.5658 |

| p value | 0.88 | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.87 | 0.95 | 0.02 | 0.64 | 0.08 | 0.28 | 0.23 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.03 |

| (A) Morning peak ratio | ||||||||||||||

| Factor | PT | PS | LSI | WP | PFD | DTC | BSD | W-15 | W-30 | D-15 | D-30 | RPD | WPD | SPOI |

| q statistic | 0.1513 | 0.034 | 0.0539 | 0.0263 | 0.0527 | 0.2334 | 0.3483 | 0.4292 | 0.1348 | 0.0633 | 0.2051 | 0.1872 | 0.4108 | 0.5823 |

| p value | 0.30 | 0.16 | 0.06 | 0.56 | 0.66 | 0.38 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.24 | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| (B) Evening activity | ||||||||||||||

| Factor | Type | Area | LSI | WP | PFD | DTC | BSD | W-15 | W-30 | D-15 | D-30 | RPD | WPD | SPOI |

| q statistic | 0.2572 | 0.0645 | 0.0943 | 0.1784 | 0.3679 | 0.1390 | 0.0952 | 0.2089 | 0.1162 | 0.3402 | 0.1488 | 0.5109 | 0.1518 | 0.6281 |

| p value | 0.11 | 0.79 | 0.08 | 0.82 | 0.03 | 0.25 | 0.57 | 0.10 | 0.20 | 0.03 | 0.58 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.00 |

| (C) Day/Night difference index | ||||||||||||||

| Factor | Type | Area | LSI | WP | PFD | DTC | BSD | W-15 | W-30 | D-15 | D-30 | RPD | WPD | SPOI |

| q statistic | 0.4743 | 0.1982 | 0.0622 | 0.0409 | 0.0216 | 0.6012 | 0.1206 | 0.2851 | 0.0390 | 0.2618 | 0.1342 | 0.2378 | 0.0842 | 0.4712 |

| p value | 0.01 | 0.23 | 0.12 | 0.79 | 0.90 | 0.01 | 0.53 | 0.06 | 0.31 | 0.24 | 0.18 | 0.06 | 0.28 | 0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).