Submitted:

19 April 2025

Posted:

21 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participantes and Procedure

2.2. Measurements

2.2. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

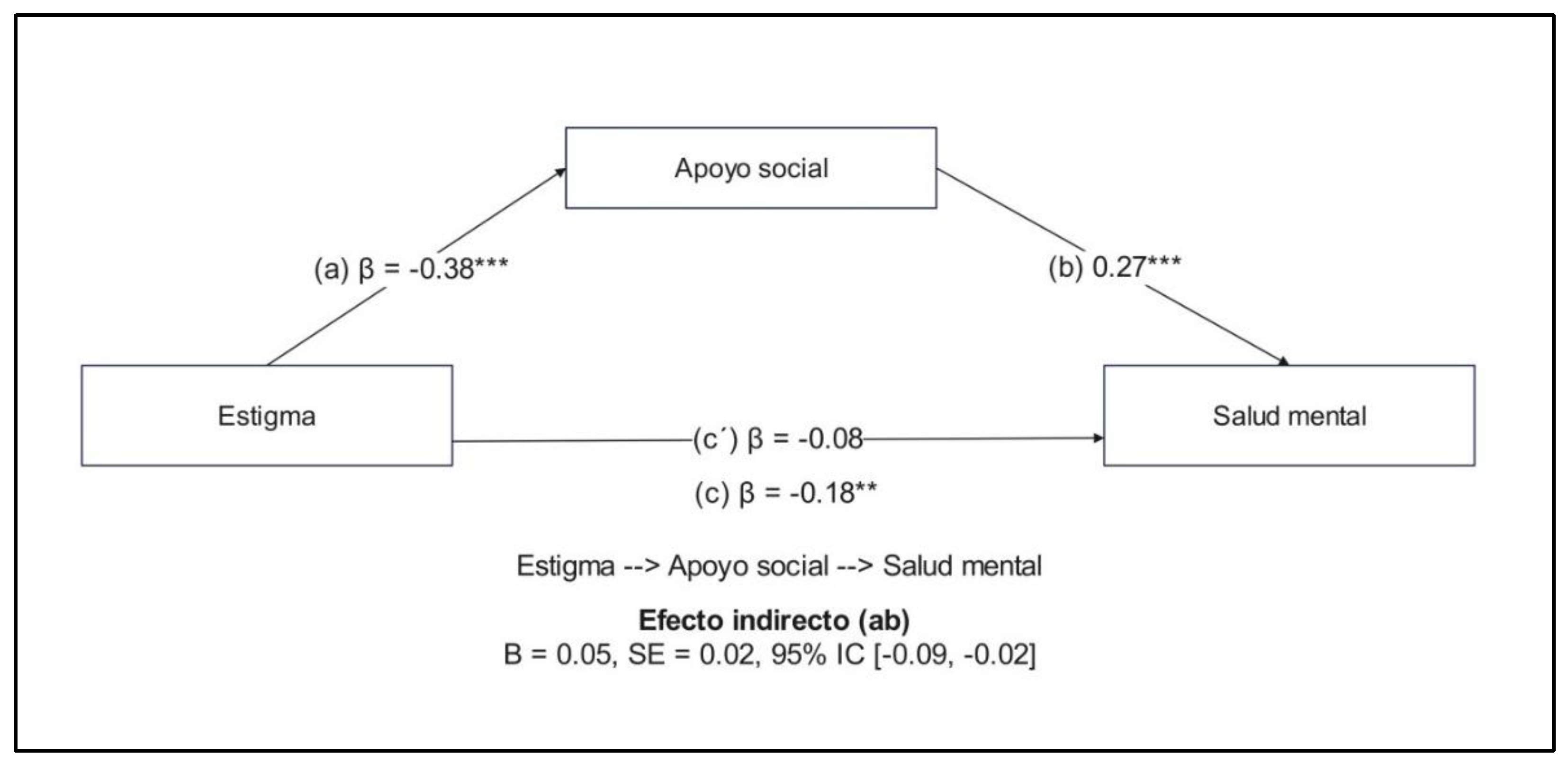

3.2. Mediational Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. VIH y sida; WHO, 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hiv-aids.

- Pan American Health Organization. Cuáles son las 10 principales amenazas a la salud en 2019; PAHO/WHO, 2019. Available online: https://www.paho.org/es/noticias/17-1-2019-cuales-son-10-principales-amenazas-salud-2019.

- UNAIDS. Hoja informativa — Últimas estadísticas sobre el estado de la epidemia de sida; UNAIDS, 2022. Available online: https://www.unaids.org/es/resources/fact-sheet.

- Pan American Health Organization. Cuadro de indicadores básicos; PAHO/WHO, 2023. Available online: https://opendata.paho.org/en/core-indicators/core-indicators-dashboard.

- Arrighi, Y.; Ventelou, B. Epidemiological Transition and the Wealth of Nations: the Case of HIV/AIDS in a Microsimulation Model. Rev econ polit 2019, 129, 591–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benade, M.; Long, L.; Rosen, S.; Meyer-Rath, G.; Tucker, J. M.; Miot, J. Reduction in initiations of HIV treatment in South Africa during the COVID pandemic. BMC Health Serv Res 2022, 22, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, A. B.; Jewell, B. L.; Sherrard-Smith, E.; Vesga, J. F.; Watson, O. J.; Whittaker, C.; Hamlet, A.; Smith, J. A.; Winskill, P.; Verity, R.; et al. Potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria in low-income and middle-income countries: a modelling study. Lancet Glob health 2020, 8, e1132–e1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, E. A.; O’Connor, R. C.; Perry, V. H.; Tracey, I.; Wessely, S.; Arseneault, L.; Ballard, C.; Christensen, H.; Cohen Silver, R.; Everall, I.; et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, G. M.; Hong, C.; Wilson, N.; Nutor, J. J.; Harris, O.; Garner, A.; Holloway, I.; Ayala, G.; Howell, S. Persistent disparities in COVID-19-associated impacts on HIV prevention and care among a global sample of sexual and gender minority individuals. Glob Public Health 2022, 17, 827–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paredes, J.; Navarro, R.; Cabrera, D.; Diaz, M.; Mejia, F.; Caceres, C. Los desafíos en la continuidad de atención de personas viviendo con VIH en el Perú durante la pandemia de la COVID-19. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica 2021, 38, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, J.; Bunn, K.; Bertoni, R. F.; Neves, O. A.; Traebert, J. Quality of life of people living with HIV. AIDS Care 2013, 25, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, J. G.; da Rocha Morgan, D. A.; Melo, F. C. M.; Dos Santos, I. K.; de Azevedo, K. P. M.; de Medeiros, H. J.; Knackfuss, M. I. Level of pain and quality of life of people living with HIV/AIDS pain and quality of life in HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care 2017, 29, 1041–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hipolito, R. L.; Oliveira, D. C.; Costa, T. L. D.; Marques, S. C.; Pereira, E. R.; Gomes, A. M. T. Quality of life of people living with HIV/AIDS: temporal, socio-demographic and perceived health relationship. Rev Latino-Am. Enfermagem 2017, 25, e2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, S. C.; de Oliveira, D. C.; Cecilio, H. P. M.; Silva, C. P.; Sampaio, L. A.; da Silva, V. X. P. Evaluating the quality of life of people living with HIV/AIDS: integrative review/Avaliacao da qualidade de vida de pessoas vivendo com HIV/AIDS: revisao integrative/Evaluación de la calidad de vida de personas que viven con VIH/SIDA: revisión integradora. Enfermagem Uerj 2020, 28, e39144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, R. K.; Santos, C. B.; Gir, E. Quality of life among Brazilian women living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care 2011, 24, 626–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Z.; Li, X.; Qiao, S.; Zhou, Y.; Shen, Z. Social support, depression, and quality of life among people living with HIV in Guangxi, China. AIDS Care 2016, 29, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammirati, R. J.; Lamis, D. A.; Campos, P. E.; Farber, E. W. Optimism, well-being, and perceived stigma in individuals living with HIV. AIDS Care 2015, 27, 926–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuster-Ruiz de Apodaca, M. J.; Molero, F.; Sansinenea, E.; Holgado, F.; Magallares, A.; Agirrezabal, A. Perceived discrimination, self-exclusion and well-being among people with HIV as a function of lipodystrophy symptoms. Anal. Psicol. 2018, 34, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, K. E.; Brennan-Ing, M.; Burr, J. A.; Dugan, E.; Karpiak, S. E. HIV Stigma and Older Men’s Psychological Well-Being: Do Coping Resources Differ for Gay/Bisexual and Straight Men? The journals of gerontology: Series B 2019, 74, 685–693. [CrossRef]

- Rzeszutek, M.; Gruszczyńska, E.; Pięta, M.; Malinowska, P. HIV/AIDS stigma and psychological well-being after 40 years of HIV/AIDS: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2021, 12, 1990527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Picón R, C.; Benavente-Cuesta, M. H.; Quevedo-Aguado, M. P.; Rodríguez-Muñoz, P. M. The Importance of Positive Psychological Factors among People Living with HIV: A Comparative Study. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heslin, M.; Jewell, A.; Croxford, S.; Chau, C.; Smith, S.; Pittrof, R.; Covshoff, E.; Sullivan, A.; Delpech, V.; Brown, A.; et al. Prevalence of HIV in mental health service users: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e067337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da, W.; Li, X.; Qiao, S.; Zhou, Y.; Shen, Z. Antiretroviral therapy and mental health among people living with HIV/AIDS in China. Psychol, Health Med 2020, 25, 45–52. [CrossRef]

- Dow, D. E.; Turner, E. L.; Shayo, A. M.; Mmbaga, B.; Cunningham, C. K.; O’Donnell, K. Evaluating mental health difficulties and associated outcomes among HIV-positive adolescents in Tanzania. AIDS Care 2016, 28, 825–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sikkema, K. J.; Watt, M. H.; Drabkin, A. S.; Meade, C. S.; Hansen, N. B.; Pence, B. W. Mental health treatment to reduce HIV transmission risk behavior: a positive prevention model. AIDS Behav 2010, 14, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anamaria, P. Informe final: índice de estigma y discriminación hacia las personas con VIH en Perú. Consorcio de organizaciones de personas con VIH en el Perú: Lima, Perú; 2018. https://plataformalac.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/MFOSC89SPa.pdf.

- Earnshaw, V. A.; Lang, S. M.; Lippitt, M.; Jin, H.; Chaudoir, S. R. HIV Stigma and Physical Health Symptoms: Do Social Support, Adaptive Coping, and/or Identity Centrality Act as Resilience Resources? AIDS Behav 2015, 19, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonca, C. J.; Newton-John, T. R. O.; Alperstein, D. M.; Begley, K.; Hennessy, R. M.; Bulsara, S. M. Quality of Life of People Living with HIV in Australia: The Role of Stigma, Social Disconnection and Mental Health. AIDS Behavr 2023, 27, 545–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikus Fido, N.; Aman, M.; Brihnu, Z. HIV stigma and associated factors among antiretroviral treatment clients in Jimma town, Southwest Ethiopia. HIV/AIDS Res. Palliat. Care. 2016, 8, 183–193. [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, S.; Shibanuma, A.; Poudel, K. C.; Nanishi, K.; Koyama Abe, M.; Shakya, S. K.; Jimba, M. Perceived social support, coping, and stigma on the quality of life of people living with HIV in Nepal: a moderated mediation analysis. AIDS Care 2019, 31, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herek, G. M. (2002). Thinking about AIDS and stigma: A psychologist’s perspective. J Law Med Ethics 2002, 30, 594-607. [CrossRef]

- Earnshaw, V. A.; Chaudoir, S. R. From conceptualizing to measuring HIV stigma: a review of HIV stigma mechanism measures. AIDS behav 2009, 13, 1160–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, B. E.; Ferrans, C. E.; Lashley, F. R. Measuring stigma in people with HIV: Psychometric assessment of the HIV stigma scale. Res Nur Health. 2001, 24, 518–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Busthomy Rofi’I, A. Y.; Kurnia, A. D.; Bahrudin, M.; Waluyo, A.; Purwanto, H. Determinant factors correlated with discriminatory attitude towards people living with HIV in Indonesian population: demographic and health survey analysis. HIV AIDS Rev 2023, 22, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, S.; Kakchapati, S. Social stigma, discrimination, and their determinants among people living with HIV and AIDS in Sudurpashchim Province, Nepal. HIV & AIDS Rev. 2022, 21, 230-238. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M. M.; Lemin, A. S.; Pangarah, C. A. Factors affecting discrimination toward people with HIV/AIDS in Sarawak, Malaysia. HIV & AIDS Rev. 2020, 19, 49-55. [CrossRef]

- Tamayo-Zuluaga, B.; Macías-Gil, Y.; Cabrera-Orrego, R.; Henao-Pelaéz, J. N.; Cardona-Arias, J. A. Estigma social en la atención de personas con VIH/SIDA por estudiantes y profesionales de las áreas de la salud, Medellín, Colombia. Rev. Cienc. salud 2015, 13, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Kooij, Y. L.; Kupková, A.; den Daas, C.; van den Berk, G. E. L.; Kleene, M. J. T.; Jansen, H. S. E.; Elsenburg, L. J. M.; Schenk, L. G.; Verboon, P.; Brinkman, K.; et al. Role of Self-Stigma in Pathways from HIV-Related Stigma to Quality of Life Among People Living with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2021, 35, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobre, N.; Pereira, M.; Roine, R. P.; Sutinen, J.; Sintonen, H. HIV-Related Self-Stigma and Health-Related Quality of Life of People Living With HIV in Finland. The Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care 2018, 29, 254–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, C.; Ochoa, A. M.; Wilson, B. D. M.; Wu, E. S. C.; Thomas, D.; Holloway, I. W. The associations between HIV stigma and mental health symptoms, life satisfaction, and quality of life among Black sexual minority men with HIV. Qual Life Res 2023, 32, 1693–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugo, C.; Kohler, P.; Kumar, M.; Badia, J.; Kibugi, J.; Wamalwa, D. C.; Kapogiannis, B.; Agot, K.; John-Stewart, G. C. Effect of HIV stigma on depressive symptoms, treatment adherence, and viral suppression among youth with HIV. AIDS 2023, 37, 813–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, L. M.; Lagos, M. G. Redes de apoyo en los procesos de stigma asociado al VIH en Nuevo León (México). Health and Addictions / Salud y Drogas 2022, 22, 40-54. [CrossRef]

- Wedajo, S.; Degu, G.; Deribew, A.; Ambaw, F. Social support, perceived stigma, and depression among PLHIV on second-line antiretroviral therapy using structural equation modeling in a multicenter study in Northeast Ethiopia. Int J Ment Health Syst 2022, 16, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cobb, S. Social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosom. Med, 1976, 38, 300-314. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1097/00006842-197609000-00003.

- Vaux, A.; Phillips, J.; Holly, L.; Thomson, B.; Williams, D.; Stewart, D. The social support appraisals (SS-A) scale: Studies of reliability and validity. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1986, 14, 195-218. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1007/BF00911821.

- Cohen, S.; Syme, L. Social support and health; Academic Press: Florida, United States, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S.; Underwood, L.; Gottlieb, B. Social support measurement and intervention; Oxford University Press: Oxford, England, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Vaux, A. Social support: theory, research, and intervention; Praeger publishers: New York, United States, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Vaux, A.; Harrison, D. Support network characteristics associates with support satisfaction and perceived support. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1985, 13, 245–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, T. T. H.; Bonner, A. Exploring the relationships between health literacy, social support, self-efficacy and self-management in adults with multiple chronic diseases. BMC Health Serv Res 2023, 23, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Held, M. L.; First, J. M.; Huslage, M. Effects of COVID-19, Discrimination, and Social Support on Latinx Adult Mental Health. J Immigrant Minority Health 2022, 24, 1446–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Zhao, Y.; Long, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ma, Y. The Effect of Perceived Social Support on the Mental Health of Homosexuals: The Mediating Role of Self-Efficacy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, D. D.; Pack, A.; Uhrig Castonguay, B.; Stewart, J. L.; Schalkoff, C.; Cherkur, S.; Schein, M.; Go, M.; Devadas, J.; Fisher, E. B.; et al. Validity of Social Support Scales Utilized Among HIV-Infected and HIV-Affected Populations: A Systematic Review. AIDS Behav 2019, 23, 2155–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakimuli-Mpungu, E.; Musisi, S.; Katabira, E.; Nachega, J.; Bass, J. Prevalence and factors associated with depressive disorders in an HIV+ rural patient population in southern Uganda. J. Affect. Disord. 2011, 135, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weldesenbet, A. B.; Kebede, S. A.; Tusa, B. S. The Effect of Poor Social Support on Depression among HIV/AIDS Patients in Ethiopia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Depress Res Treat 2020, 6633686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Luo, B.; Qin, L.; Gong, H.; Chen, Y. Suicidal ideation of people living with HIV and its relations to depression, anxiety and social support. BMC Psychol 2023, 11, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, M. A. Apoyo social, autoestima y calidad de vida entre las personas que viven con el VIH / SIDA en Jammu y Cachemira, India. Anal. Psicol. 2020, 36, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, B.; Song, B.; Feng, S.; Lin, Y.; Du, J.; Shao, H.; Chi, Z.; Yang, Y.; Wang, F. The relationship of social support, mental health, and health-related quality of life in human immunodeficiency virus-positive men who have sex with men: From the analysis of canonical correlation and structural equation model: A cross-sectional study. Medicine 2018, 97, e11652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemu, A.; Meskele, M.; Darebo, T. D.; Beyene Handiso, T.; Abebe, A.; Paulos, K. Perceived HIV Stigma and Associated Factors Among Adult ART Patients in Wolaita Zone, Southern Ethiopia. HIV/AIDS 2022, 14, 487–501. [CrossRef]

- Brittain, K.; Mellins, C. A.; Phillips, T.; Zerbe, A.; Abrams, E. J.; Myer, L.; Remien, R. H. Social Support, Stigma and Antenatal Depression Among HIV-Infected Pregnant Women in South Africa. AIDS Behav 2017, 21, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Hernansaiz, H.; Heylen, E.; Bharat, S.; Ramakrishna, J.; Ekstrand, M. L. Stigmas, symptom severity and perceived social support predict quality of life for PLHIV in urban Indian context. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2016, 14, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, D.; Shrivastava, P. Mediation effect of social support on the association between hardiness and immune response. Asian J Psychiatr 2017, 26, 52–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Mo, P. K.; Wu, A. M.; Lau, J. T. Roles of Self-Stigma, Social Support, and Positive and Negative Affects as Determinants of Depressive Symptoms Among HIV Infected Men who have Sex with Men in China. AIDS Behav 2017, 21, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, M.; Truszczynski, N.; Newbold, J.; Coffman, R.; King, A.; Brown, M. J.; Radix, A.; Kershaw, T.; Kirklewski, S.; Sikkema, K.; et al. The mediating role of social support between HIV stigma and sexual orientation-based medical mistrust among newly HIV-diagnosed gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men. AIDS Care 2022, 35, 696–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Jang, S.; Rim, H. D.; Kim, S. W.; Chang, H. H.; Woo, J. Attachment Insecurity and Stigma as Predictors of Depression and Anxiety in People Living With HIV. Psychiatry Investig 2023, 20, 418–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhao, M.; Ren, J.; Qi, X.; Sun, H.; Qu, L.; Yan, C.; Zheng, T.; Wu, Q.; Cui, Y. Identifying factors associated with depression among men living with HIV/AIDS and undergoing antiretroviral therapy: a cross-sectional study in Heilongjiang, China. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2018, 16, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travaglini, L. E.; Himelhoch, S. S.; Fang, L. J. HIV Stigma and Its Relation to Mental, Physical and Social Health Among Black Women Living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Behav 2018, 22, 3783–3794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, G. L. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science 1977, 196, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, D. T.; Halligan, P. W. The biopsychosocial model of illness: a model whose time has come. Clin. Rehabil. 2017, 31, 995–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballester, R. Aportaciones desde la psicología al tratamiento de las personas con infección por VIH/SIDA. Revista de Psicopatología y Psicología Clínica 2005, 10, 53–69. [CrossRef]

- Cantú Guzmán, R.; Álvarez Bermúdez, J.; Torres López, E.; Sulvarán, O. M. Impacto psicosocial en personas que viven con VIH-sida en Monterrey, México. Psicología y Salud 2012, 22, 136–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, E. J.; Harrington, K. M.; Clark, S. L.; Miller, M. W. Sample size requirements for structural equation models: An evaluation of power, bias, and solution propriety. Educ Psychol Meas 2013, 73, 913–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soper, D. S. A-priori Sample Size Calculator for Structural Equation Models. Free Statistics Calculators. 2020. http://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc.

- Wright, K.; Naar-King, S.; Lam, L.; Templin, T.; Frey, M. Stigma scale revised: reliability and validity of a brief measure of stigma for HIV+ youth. J Adolesc Helath. 2007, 40, 96–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjit, Y. S.; Krishnan, A.; Earnshaw, V. A.; Weikum, D.; Ferro, E. G.; Sanchez, J.; Altice, F. L. Psychometric evaluation and validation of the HIV Stigma Scale in Spanish among men who have sex with men and transgender women. Stigma and Health 2021, 8, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nava Quiroz, C. N.; Bezies, R.; Vega, C. Z. Adaptación y validación de la escala de percepción de apoyo social de vaux. Liberabit 2015, 21, 49–58, http://www.scielo.org.pe/scielo.php?pid=S1729-48272015000100005&script=sci_arttext&tlng=pt. [Google Scholar]

- Cárdenas, M.; Barrientos, J.; Ricci, E. Estructura factorial de la escala de soporte social subjetivo: validación en una muestra de estudiantes universitarios chilenos. Act. Colom. Psicol. 2015, 18, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manrique-Millones, D. L. M.; Rivalles, R. M.; Lara, S. D.; Marín, C. P.; Pino, O. M. Apoyo social en educación superior: evidencias de validez y confiabilidad en el contexto peruano. Universitas Psychologica 2020, 19, 1-11. https://doi-org/1. 10.11144/Javeriana.upsy19.sshe.

- Veit, C. T.; Ware, J. E. The structure of psychological distress and well-being in general populations. J Consult. Clin Psychol. 1983, 51, 730–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berwick, D. M.; Murphy, J. M.; Goldman, P. A.; Ware Jr, J. E.; Barsky, A. J.; Weinstein, M. C. Performance of a five-item mental health screening test. Medical Care 1991, 169-176. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3766262.

- Merino-Soto, C.; Cuba-Canales, Y.; Rojas-Aquiño, L. Inventario de Salud Mental-5 (MHI-5) en adolescentes peruanos: estudio preliminar de validación. Rev. salud pública 2019, 21, 439–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Commun. Monogr. 2017, 85, 4–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Jaarsveld, D. D.; Walker, D. D.; Skarlicki, D. P. The role of job demands and emotional exhaustion in the relationship between customer and employee incivility. J Managet 2010, 36, 1486–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovakov, A.; Agadullina, E. Empirically derived guidelines for effect size interpretation in social psychology. European Journal of Social Psychology 2021, 51, 485–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logie, C. H.; Wang, Y.; Lacombe-Duncan, A.; Wagner, A. C.; Kaida, A.; Conway, T.; Webster, K.; de Pokomandy, A.; Loutfy, M. R. HIV-related stigma, racial discrimination, and gender discrimination: Pathways to physical and mental health-related quality of life among a national cohort of women living with HIV. Preventive Medicine 2018, 107, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Li, X.; Li, J.; Wang, W.; Yang, Y.; Yao, X.; Yang, N.; Li, S. Association between perceived HIV stigma, social support, resilience, self-esteem, and depressive symptoms among HIV-positive men who have sex with men (MSM) in Nanjing, China. AIDS Care 2019, 31, 1069–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orza, L.; Bewley, S.; Logie, C. H.; Crone, E. T.; Moroz, S.; Strachan, S.; Vazquez, M.; Welbourn, A. How does living with HIV impact on women’s mental health? Voices from a global survey. J Int AIDS Soc 2015, 18, 20289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, I. H. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin 2023, 129, 674–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rueda, S.; Mitra, S.; Chen, S.; Gogolishvili, D.; Globerman, J.; Chambers, L.; Wilson, M.; Logie, C. H.; Shi, Q.; Morassaei, S.; et al. Examining the associations between HIV-related stigma and health outcomes in people living with HIV/AIDS: a series of meta-analyses. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gesesew, H. A.; Tesfay Gebremedhin, A.; Demissie, T. D.; Kerie, M. W.; Sudhakar, M.; Mwanri, L. Significant association between perceived HIV related stigma and late presentation for HIV/AIDS care in low and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One 2017, 12, e0173928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras Jara, B.; Cordero Álvarez, F.; Pino Morales, V.; Ávalos Blaser, J. Adherencias al tratamiento antiretroviral de la persona adulta viviendo con VIH/SIDA. Benessere – Revista de Enfermería 2021, 6, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Song, H. Structural stigma and mental health among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults: Policy protection and cultural acceptance. Soc. Sci. Med. 2025, 373, 117985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollack, T. M.; Duong, H. T.; Nhat Vinh, D. T.; Phuong, D. T.; Thuy, D. H.; Nhung, V. T. T.; Uyen, N. K.; Linh, V. T.; Van Truong, N.; Le Ai, K. A.; Ninh, N. T.; Nguyen, A.; Canh, H. D.; Cosimi, L. A. Un diseño pretest-postest para evaluar la eficacia de una intervención para reducir el estigma y la discriminación relacionados con el VIH en entornos sanitarios de Vietnam. J Int AIDS Soc 2022, 25, e25932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stangl, A. L.; Lloyd, J. K.; Brady, L. M.; Holland, C. E.; Baral, S. A systematic review of interventions to reduce HIV-related stigma and discrimination from 2002 to 2013: how far have we come? J Int AIDS Soc 2013, 16, 18734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | (n=303) |

|---|---|

| Sex (%) | |

| Woman | 223 (73.6%) |

| Man | 80 (26.4%) |

| Sexual orientation (%) | |

| Heterosexual | 163 (53.8%) |

| Homosexual | 108 (35.6%) |

| Bisexual | 26 (8.6%) |

| Other | 6 (2.0%) |

| Age (M ± SD) | 40.55 ± 11.17 |

| Educational level (%) | |

| Primary school | 32 (10.6%) |

| Secondary school | 131 (43.2%) |

| Higher technical | 57 (18.8%) |

| Higher education | 83 (27.4%) |

| Marital status (%) | |

| Single | 190 (62.7%) |

| Married / live-in partner | 95 (31.4%) |

| Divorced / separated | 18 (5.9%) |

| Employment status (%) | |

| Employed | 231 (76.2%) |

| Unemployed | 57 (18.8%) |

| Student | 14 (4.6%) |

| Retired | 1 (0.3%) |

| Time of diagnosis (M ± SD) | 81.8 ± 129.34 |

| Variable | M | SD | Min | Max | 1 | 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Stigma | 21.23 | 5.43 | 10 | 58 | - | |

| 2. Social support | 48.03 | 7.12 | 18 | 91 | -0.377** | - |

| 3. Mental health | 15.69 | 2.87 | 6 | 20 | -0.175** | 0.293** |

| Model routes | Estimated effect | SE | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effects | ||||

| Stigma --> Mental health | -0.08 | 0.03 | -0.10, 0.02 | 0.2094 |

| Stigma --> Social support | -0.38 | 0.02 | -0.63, -0.36 | <0.001*** |

| Social --> Mental health | 0.27 | 0.09 | 0.06, 0.15 | <0.001*** |

| Indirect effect | ||||

| Stigma --> Social support--> Mental health | -0.05 | 0.02 | -0.09, - 0.02 | <0.001*** |

| Total effect | -0.18 | 0.03 | -0.15, -0.03 | 0.0023** |

| Variables | Stigma | Social support | Mental health |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.073 b | 0.003 b | -0.265 b ** |

| Age | 0.011 a | -0.055 a | -0.025 a |

| Orientation | 0.001 c | 0.031 c | 0.003 c |

| Educational level | 0.047 c | 0.072 c | 0.009 c |

| Marital status | 0.003 c | 0.000 c | 0.004 c |

| Employment status | 0.025 c | 0.022 c | 0.024 c |

| Time of diagnosis | 0.021 a | -0.036 a | 0.002 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).