Submitted:

21 April 2025

Posted:

21 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

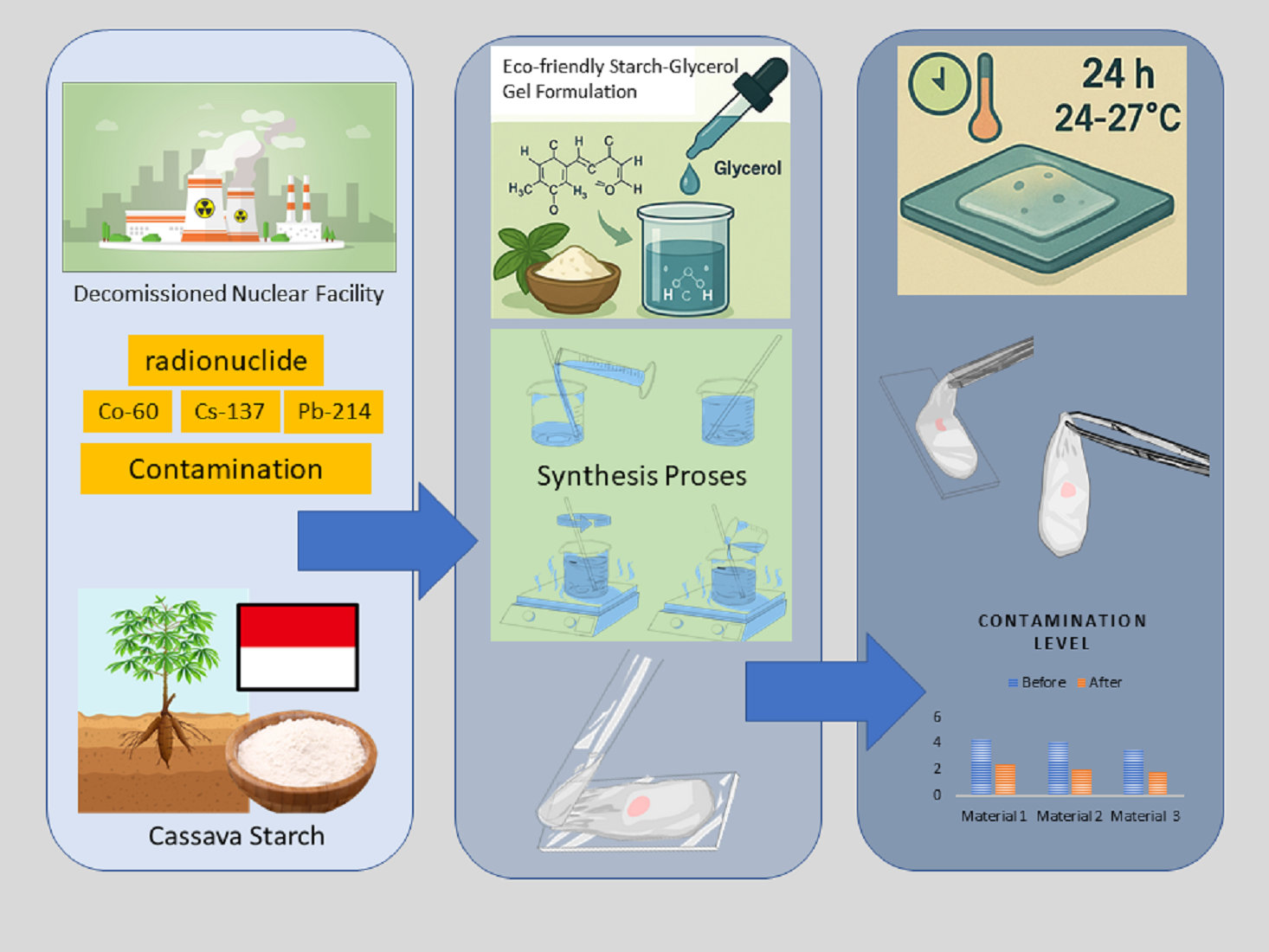

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

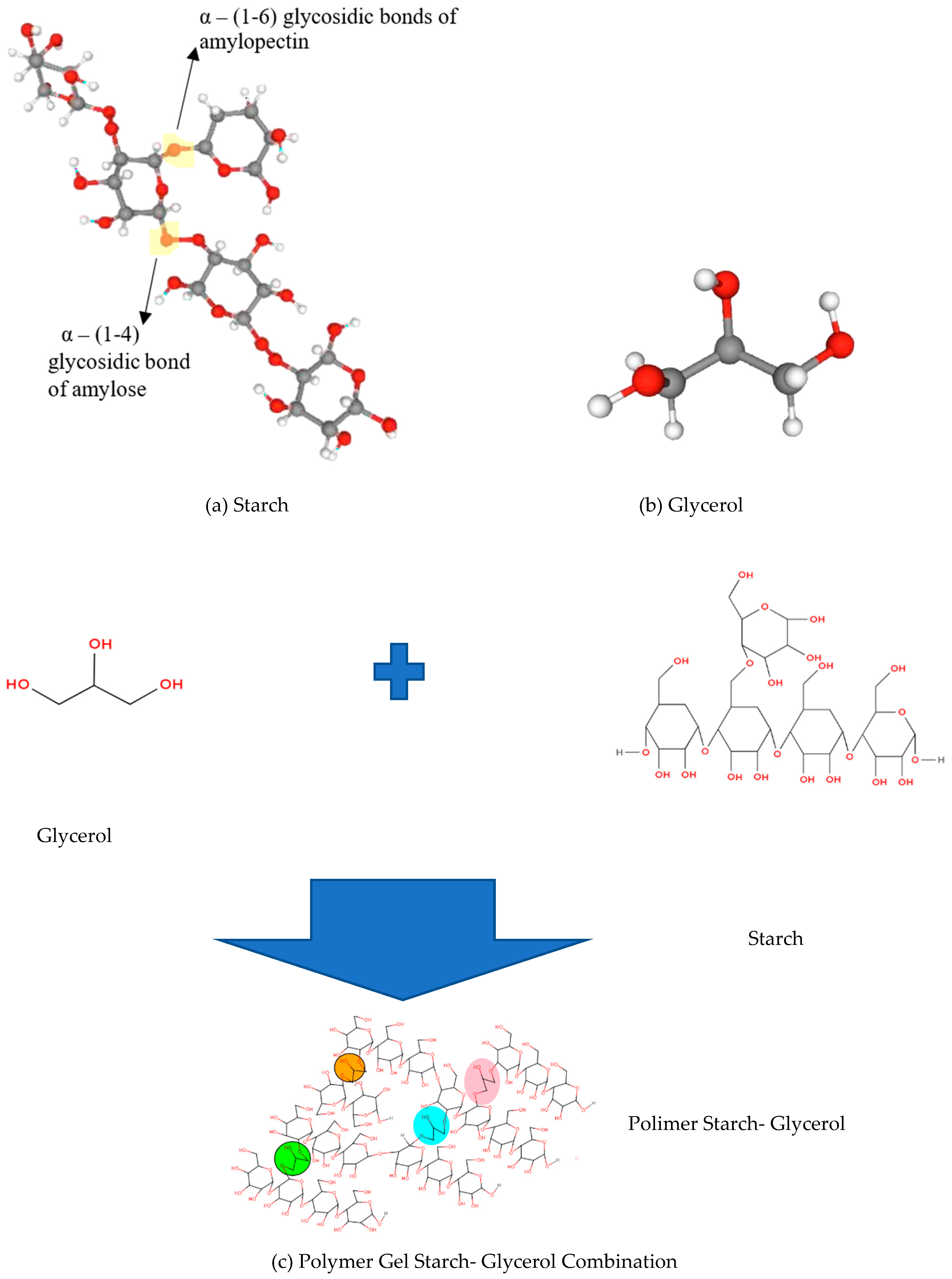

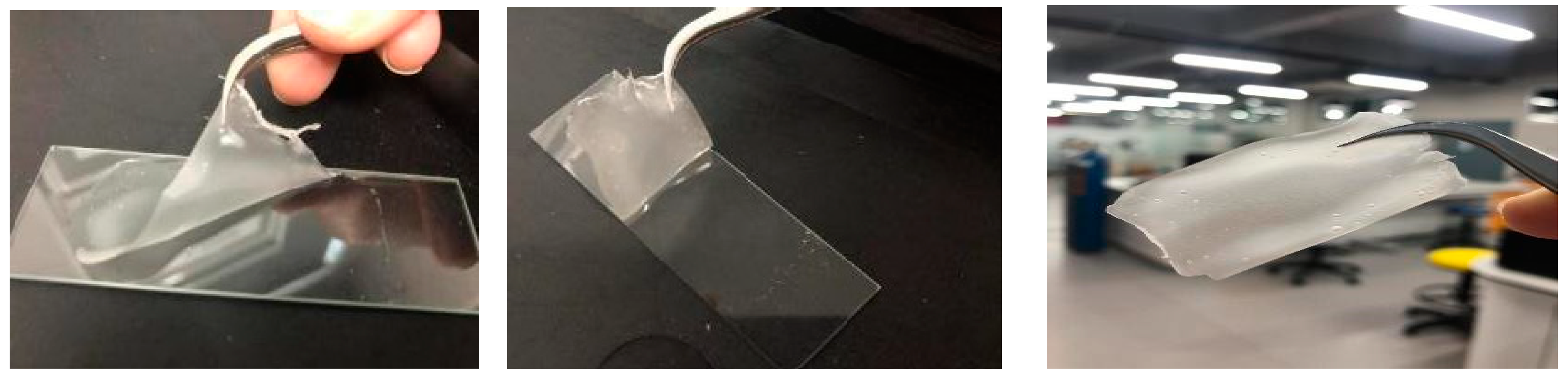

2.1. Pati Gel

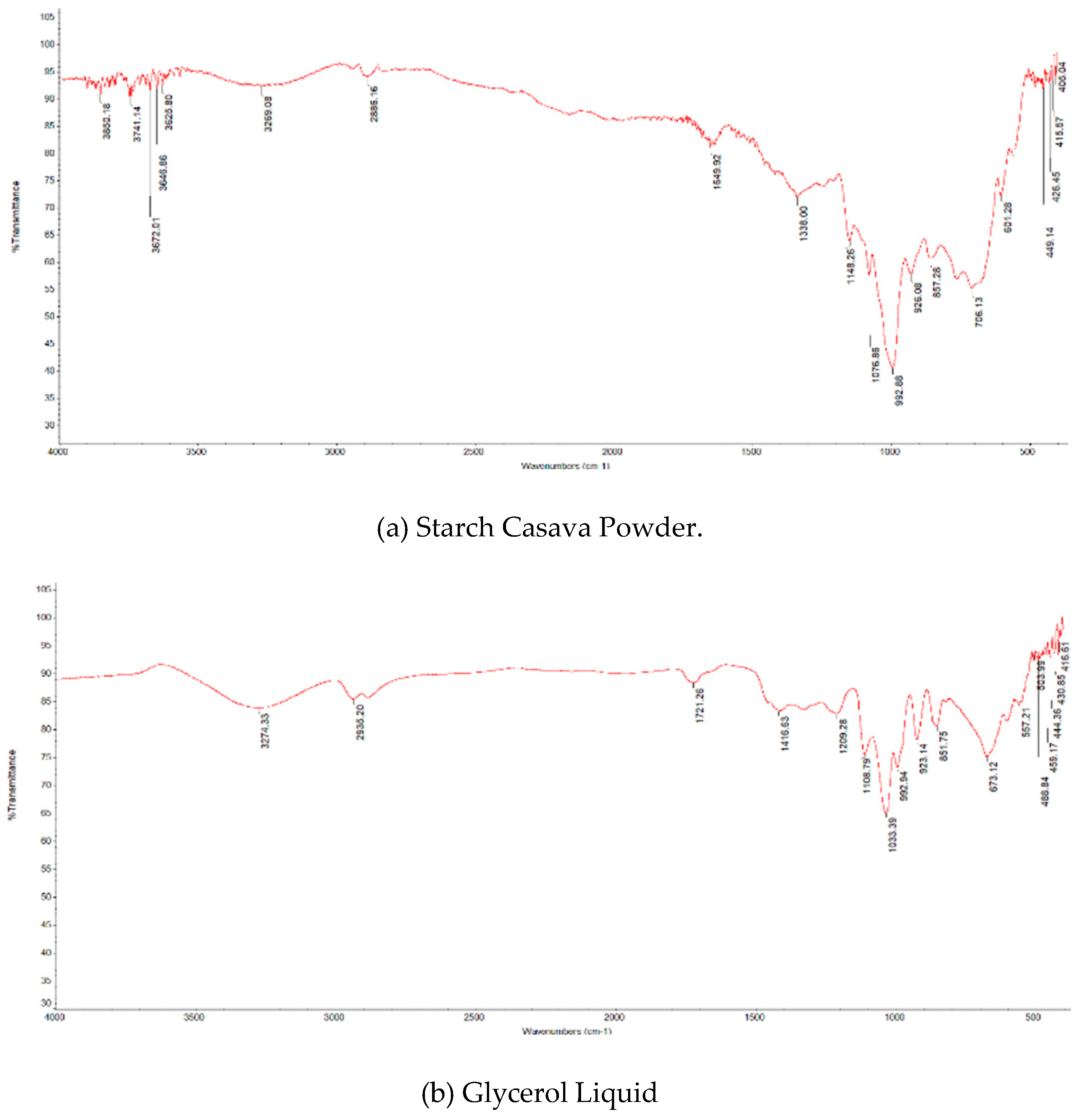

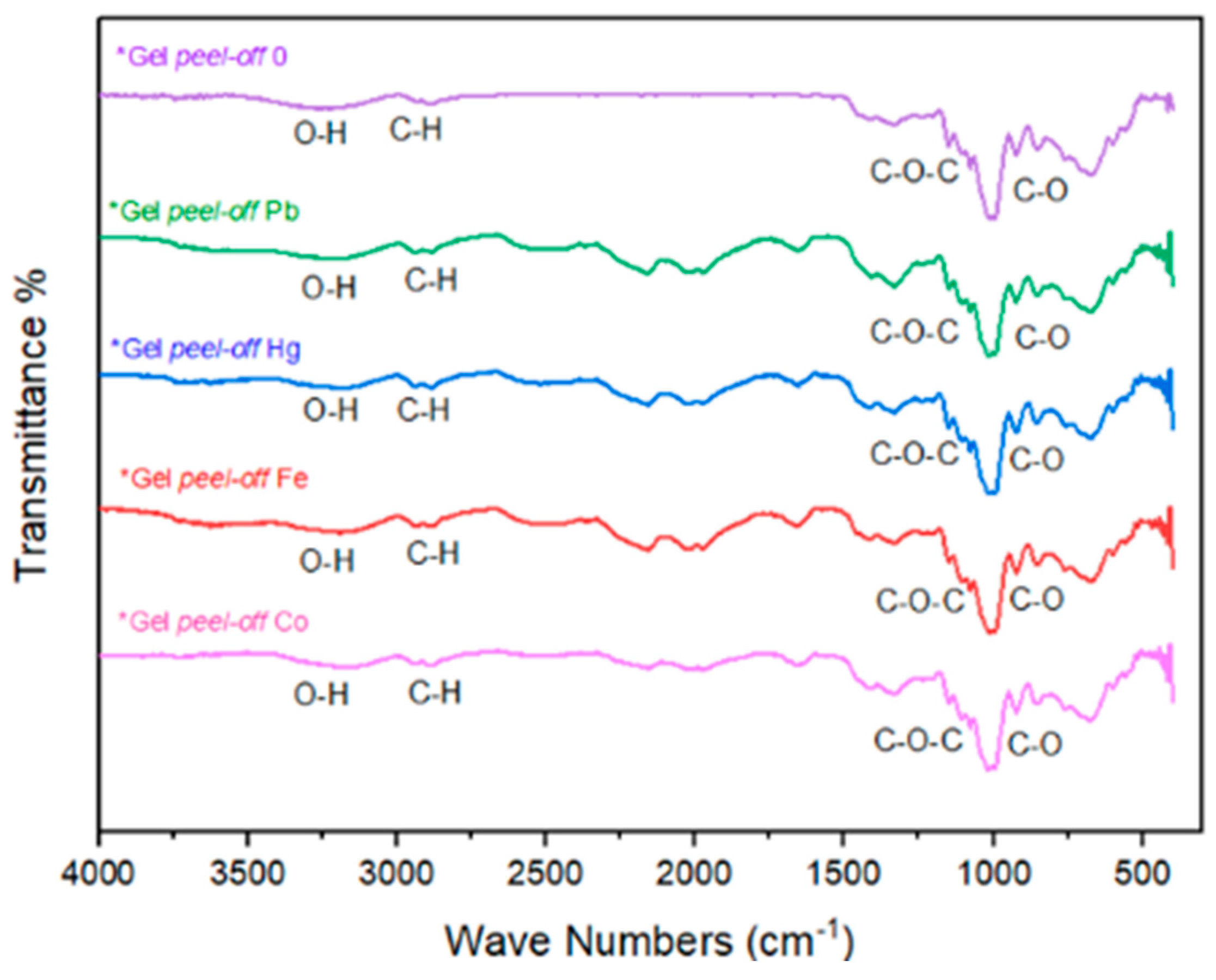

2.2. FTIR Analysis

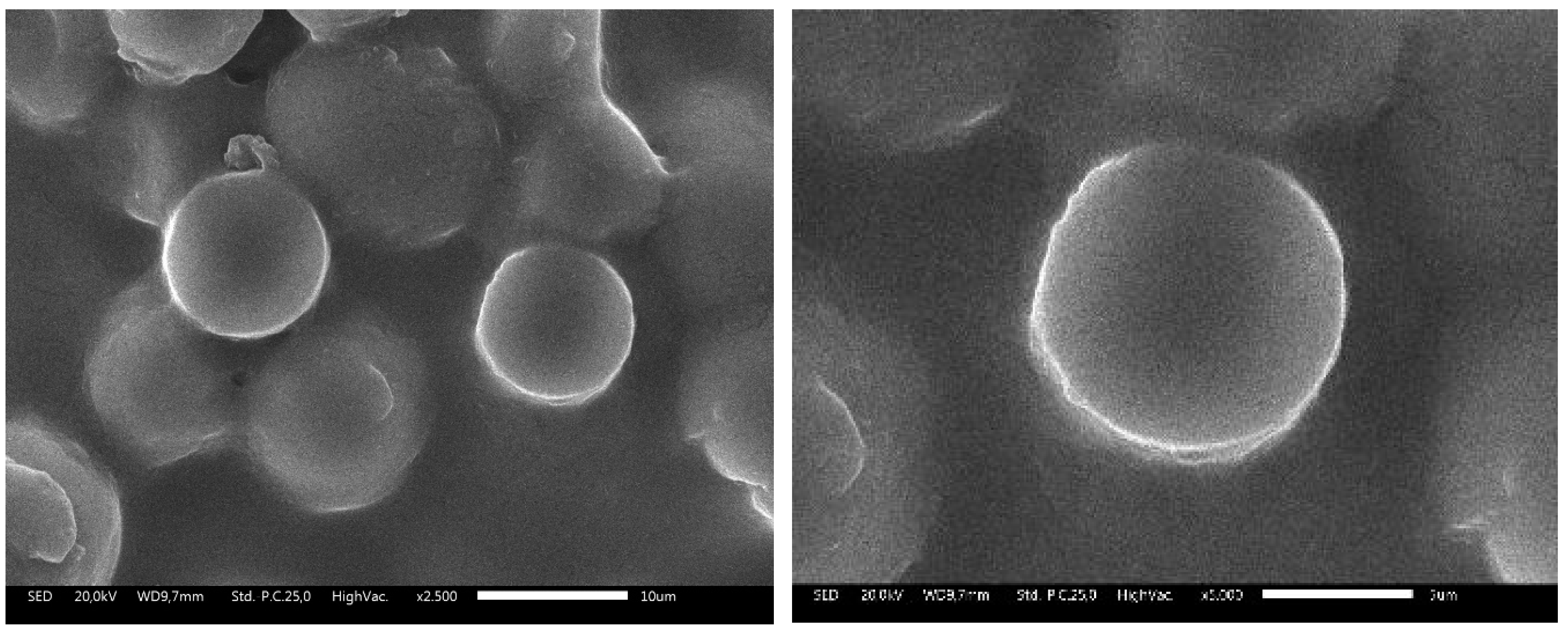

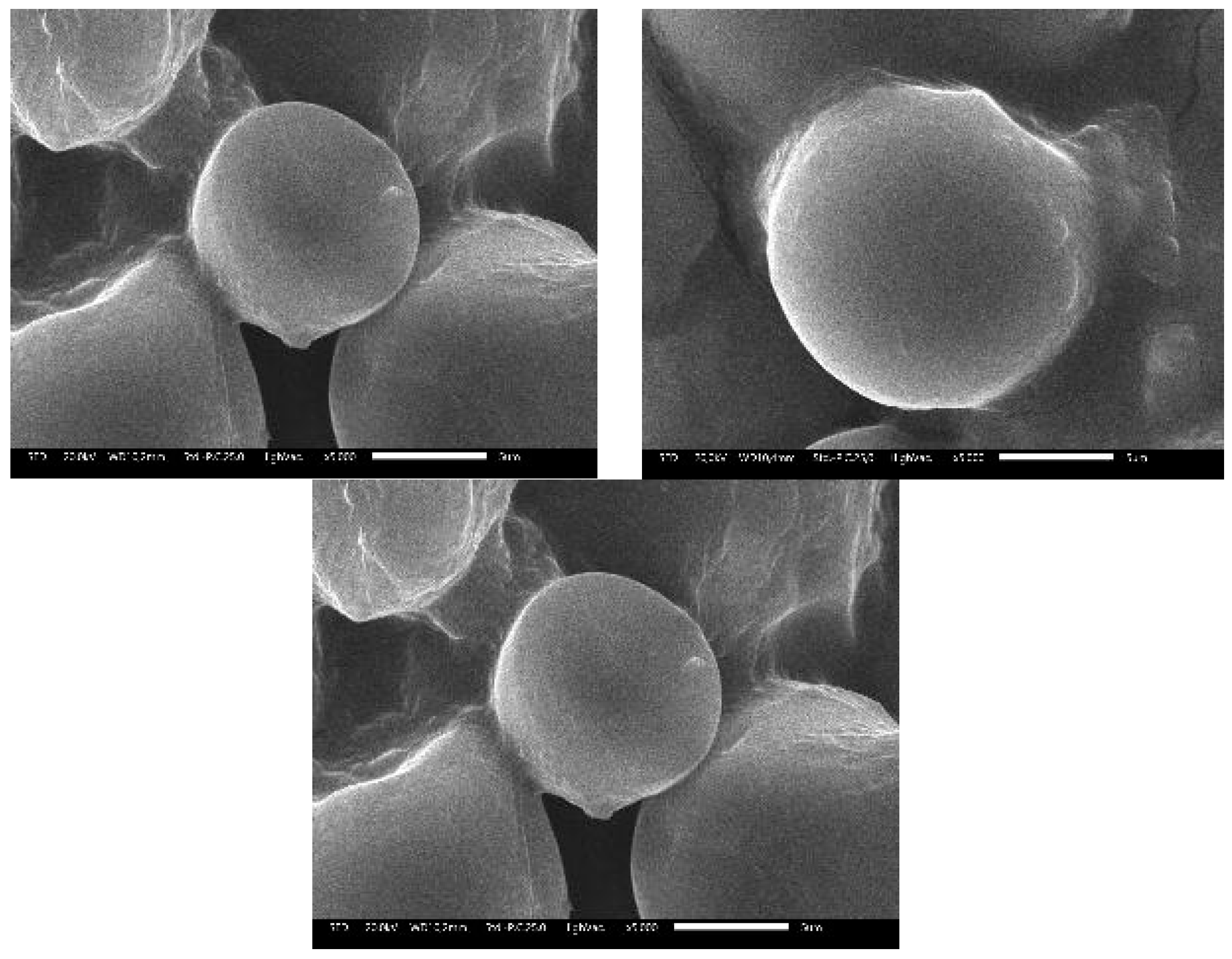

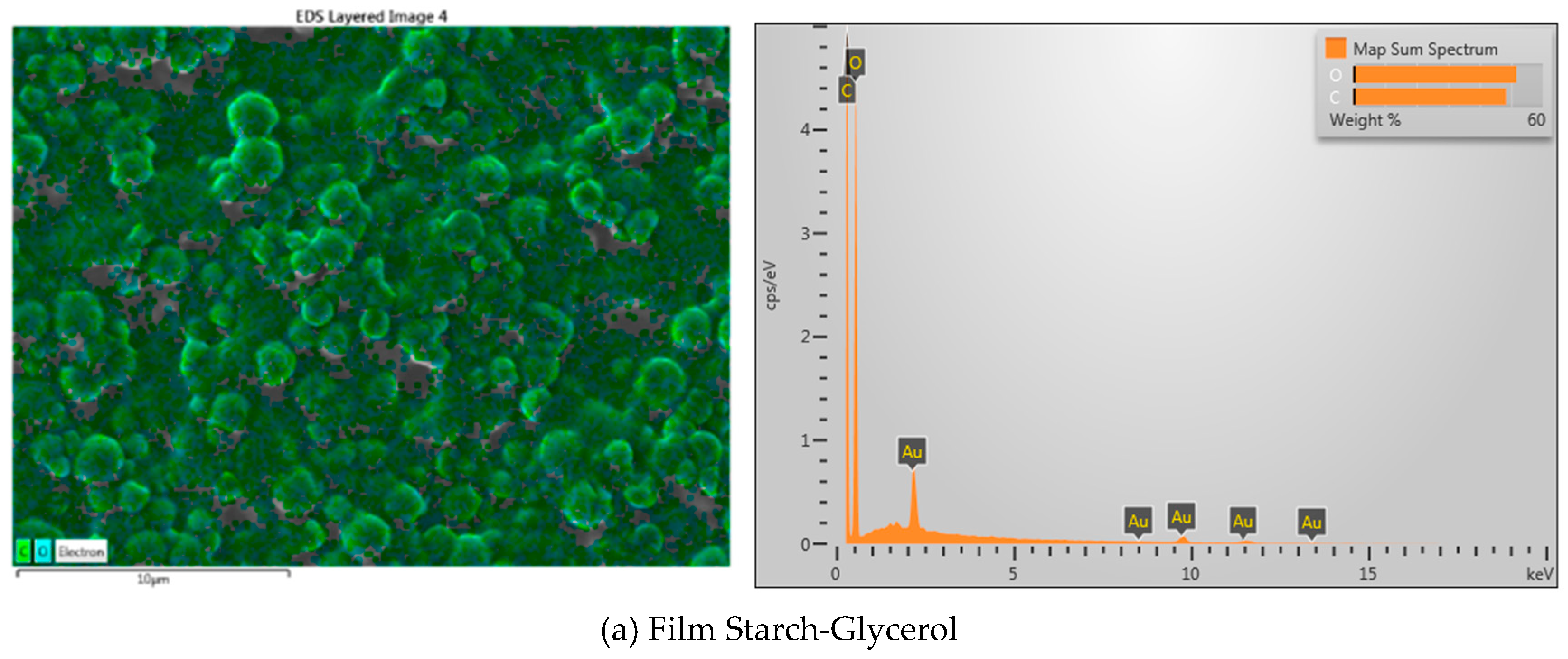

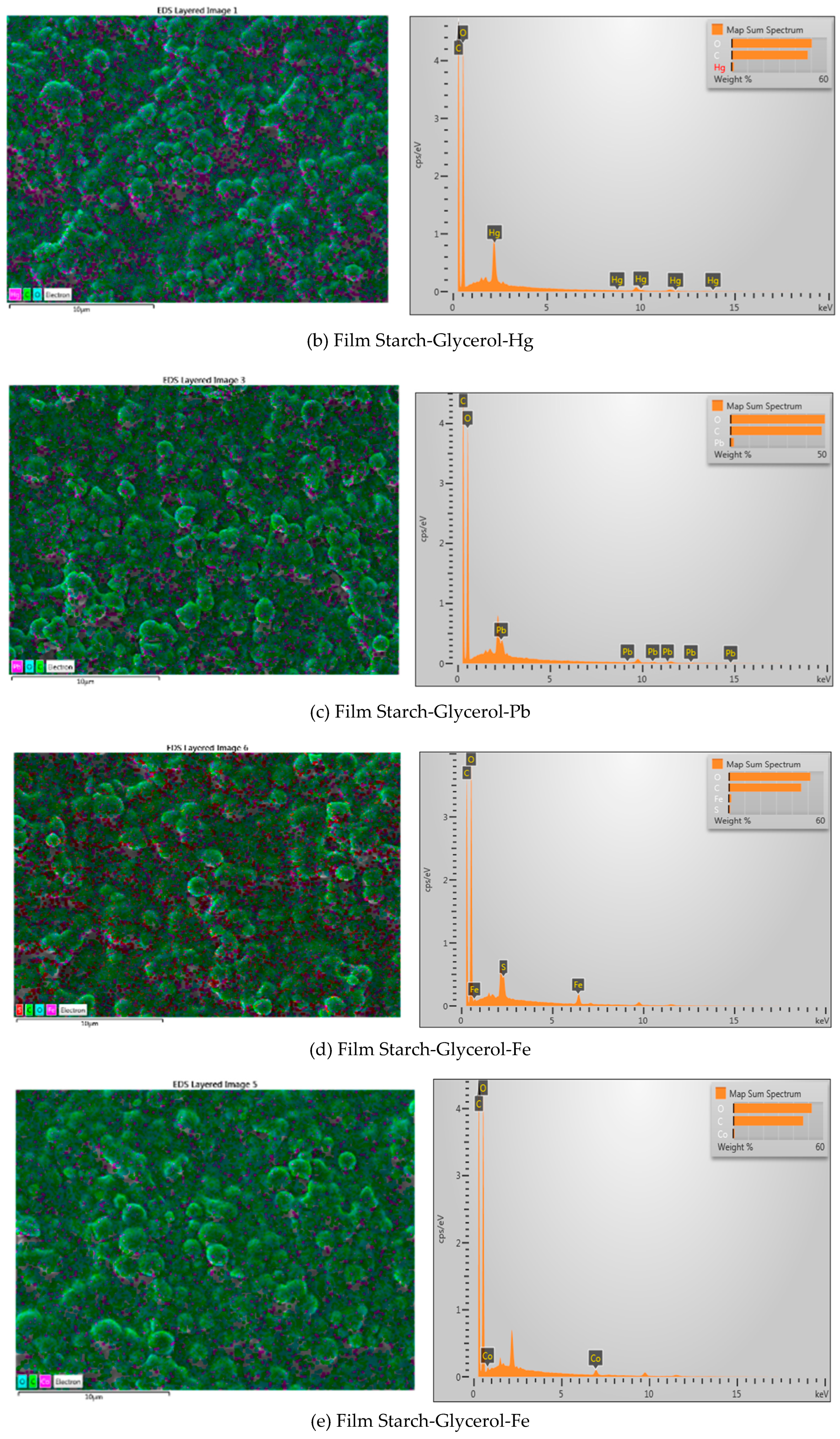

2.3. SEM Analysis

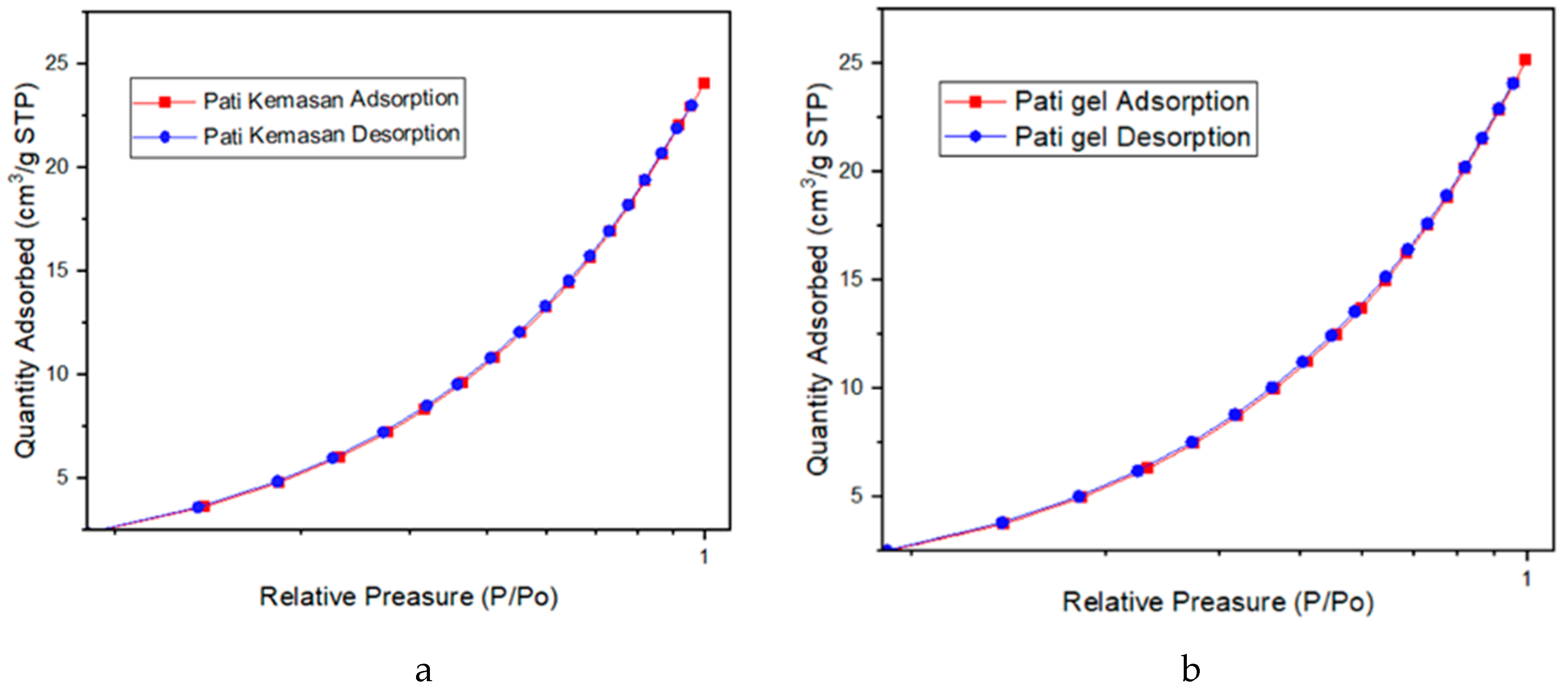

2.4. BET Analysis

2.5. XRF Analysis

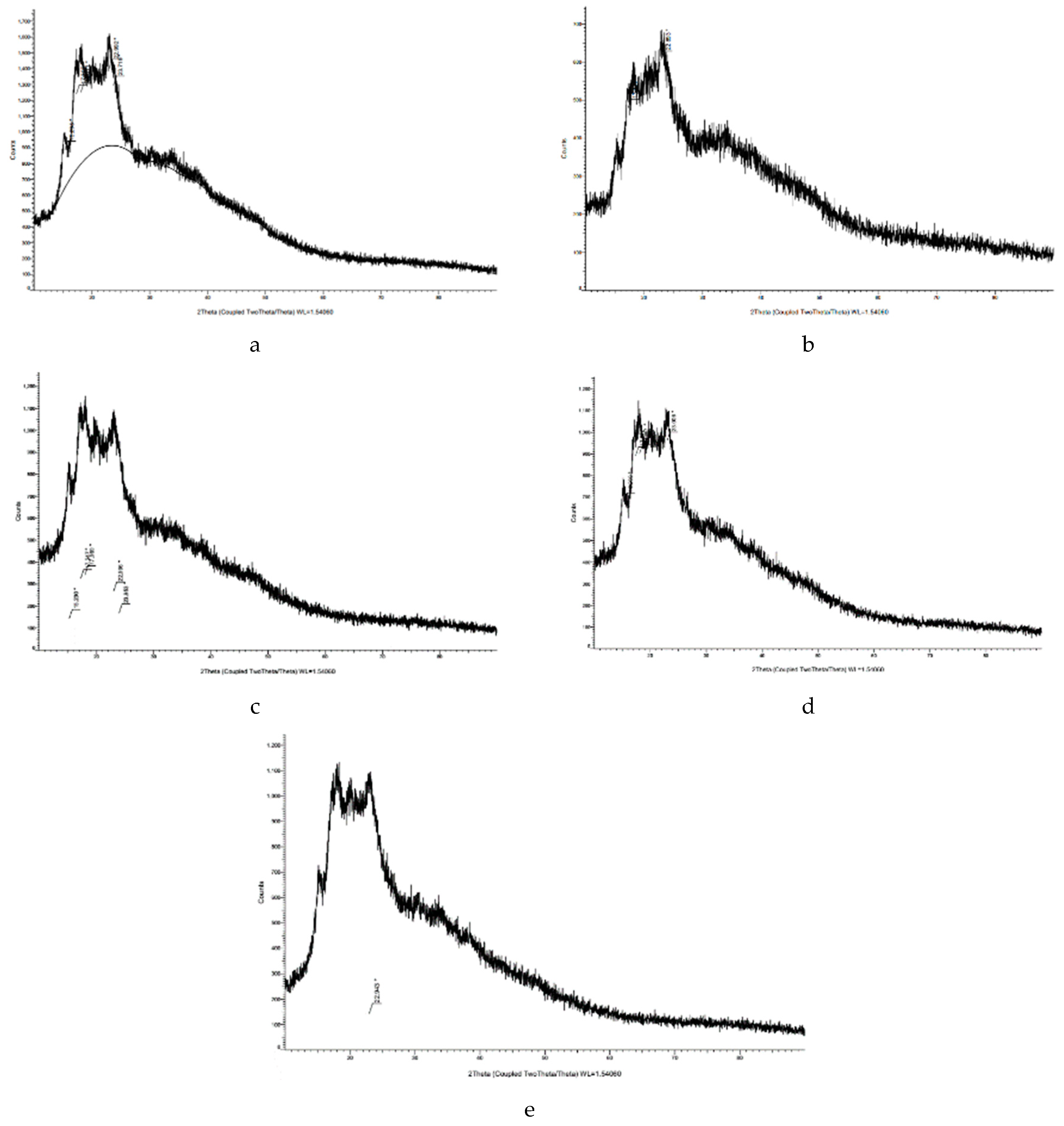

2.6. XRD Analysis

3. Material and Method

4. Conclusion

Acknowledgements

References

- Badan Tenaga Nujklir Nasional (BATAN). Buku Putih Pemanfaatan Reaktor Riset BATAN; BATAN: Jakarta, 2016; 1–66p. [Google Scholar]

- Alamsyah, R.; Yudhi Pristianto, A.P. Infrastuktur Keselamatan Dekomisioning Fasilitas Nuklir di Indonesia. In Prosiding Seminar Nasional Teknologi Pengelolaan Limbah XV-2017; Tanggerang, 2017; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Anggakusuma, R.; Utama, G.L.; Zain, M.K.; Megasari, K. Reducing the Radioactive Surface Contamination Level of Cobalt-60-Contaminated Material with PVA-Glycerol-EDTA Combination Gel. Gels 2025, 11, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Septilarso, A.; Kawasaki, D.; Yanagihara, S. Radioactive waste inventory estimation of a research reactor for decommissioning scenario development. J Nucl Sci Technol. 2020, 57, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utami, S.B.; Putero, S.H. Regulatory Framework for the Decommissioning of Indonesian Nuclear Facilities. Journal of Nuclear Engineering and Radiation Science 2017, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauridsen, K. 11 - Recent experience in decommissioning research reactors. In Advances and Innovations in Nuclear Decommissioning; Laraia, M., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing, 2017; pp. 315–343, (Woodhead Publishing Series in Energy). [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, I.F. A nuclear inspector’s perspective on decommissioning at UK nuclear sites. J Radiol Prot [Internet] 1999, 19, 203–212. Available online: http://iopscience.iop.org/0952-4746/19/3/201. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locatelli, G.; Mancini, M. Competitiveness of small-medium, new generation reactors: A comparative study on decommissioning. J Eng Gas Turbine Power 2010, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldas Neto, A.B.; Silva, A.T. Strategies for decommissioning small nuclear reactors in Brazil. Nuclear Engineering and Design 2023, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardtenschlager, R.; Bottger, D.; Gasch, A.; Majohr, N. Decommissioning of Light-Water Reactor Nuclear Power Plants. Nuclear Engineering and Design 1978, 1–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, Y.A.; Hornibrook, C.; Yim, M.S. Decisions on nuclear decommissioning strategies: Historical review. Progress in Nuclear Energy [Internet] 2018, 106, 34–43. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0149197018300234. [CrossRef]

- Mariani, C.; Mancini, M. Selection of projects’ primary and secondary mitigation actions through optimization methods in nuclear decommissioning projects. Nuclear Engineering and Design 2023, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Invernizzi, D.C.; Locatelli, G.; Brookes, N.J. How benchmarking can support the selection, planning and delivery of nuclear decommissioning projects. Progress in Nuclear Energy 2017, 99, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Invernizzi, D.C.; Locatelli, G.; Brookes, N.J. Managing social challenges in the nuclear decommissioning industry: A responsible approach towards better performance. International Journal of Project Management 2017, 35, 1350–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De, P.L. Costs of decommissioning nuclear power plants: A report on recent international estimates. March 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; He, Y.; Xie, H.; Ge, Y.; Lin, Y.; Yao, Z.; et al. A State-of-the-Art Review of Radioactive Decontamination Technologies: Facing the Upcoming Wave of Decommissioning and Dismantling of Nuclear Facilities. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Atomic Energy Agency. Global Status of Decommissioning of Nuclear Instalation [Internet]. Vienna. March 2023. Available online: www.iaea.org/publications.

- Gurau, D.; Deju, R. Radioactive decontamination technique used in decommissioning of nuclear facilities [Internet]. Article in Romanian Journal of Physics. 2014. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280920950.

- Liu, S.; He, Y.; Xie, H.; Ge, Y.; Lin, Y.; Yao, Z.; et al. A State-of-the-Art Review of Radioactive Decontamination Technologies: Facing the Upcoming Wave of Decommissioning and Dismantling of Nuclear Facilities. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koryakovskiy, Y.S.; Doilnitsyn, V.A.; Akatov, A.A. Improving the efficiency of fixed radionuclides’ removal by chemical decontamination of surfaces in situ. Nuclear Energy and Technology 2019, 5, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Hong, S.; Nam, S.; Kim, W.S.; Um, W. Decontamination of concrete waste from nuclear power plant decommissioning in South Korea. Ann Nucl Energy 2020, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahm, I.; Kim, D.; Ryu, H.J.; Choi, S. A multi-criteria decision-making process for selecting decontamination methods for radioactively contaminated metal components. Nuclear Engineering and Technology 2023, 55, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertel, N.; Buttram, C.; Ervin, P.; Lunberg, L.; Marske, S. Research Reactor Decommissioning Planning—It is Never Too Early to Start. Sydney. March 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, M.T.; Green, T.H.; Adsley, I. Characterisation of radioactive materials in redundant nuclear facilities: Key issues for the decommissioning plan. In Nuclear Decommissioning; Elsevier, 2012; pp. 87–116. [Google Scholar]

- Gurau, D.; Deju, R. Radioactive decontamination technique used in decommissioning of nuclear facilities. Article in Romanian Journal of Physics [Internet] 2014, 59, 912–919. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280920950.

- Zhong, L.; Lei, J.; Deng, J.; Lei, Z.; Lei, L.; Xu, X. Existing and potential decontamination methods for radioactively contaminated metals-A Review. Progress in Nuclear Energy 2021, 139, 103854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellani, R.; Poulesquen, A.; Goettmann, F.; Marchal, P.; Choplin, L. A topping gel for the treatment of nuclear contaminated small items. Nuclear Engineering and Design 2014, 278, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.J.; Raine, T.P.; Jenkins, A.; Livens, F.R.; Law, K.A.; Morris, K.; et al. Decontamination of caesium and strontium from stainless steel surfaces using hydrogels. React Funct Polym. 2019, 142, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gossard, A.; Lilin, A.; Faure, S. Gels, coatings and foams for radioactive surface decontamination: State of the art and challenges for the nuclear industry. Progress in Nuclear Energy 2022, 149, 104255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminski, M.D.; Lee, S.D.; Magnuson, M. Wide-area decontamination in an urban environment after radiological dispersion: A review and perspectives. In Journal of Hazardous Materials; Elsevier B.V., 2016; Volume 305, pp. 67–86. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, S.; Sadegh, H.; Monajjemi, M.; Hamdy, A.S.; Ali, G.A.M.; Memar, A.O.H.; et al. Efficient removal of toxic bromothymol blue and methylene blue from wastewater by polyvinyl alcohol. J Mol Liq. 2016, 218, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, C.H.; Moon, J.K.; Won, H.J.; Lee, K.W.; Kim, C.K. Chemical Gel for Surface Decontamination. Transactions of the Korean Nuclear Society Autumn Meeting Jeju.

- Ma, L.; Wang, J.; Han, L.; Lu, C. Research Progress of Chemical Decontamination Technology in the Decommissioning of Nuclear Facilities. International Core Journal of Engineering 2020, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Purna Yudha, E.; Salsabila, A.; Haryati, T. ANALISIS DAYA SAING EKSPOR KOMODITAS UBI KAYU INDONESIA, THAILAND DAN VIETNAM DI PASAR DUNIA. JURNAL MANEKSI 2023, 12, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardyani, N.P.; Gunawan, B.; Harahap, J. Ekologi Politik Budidaya Singkong di Kecamatan Arjasari Kabupaten Bandung Provinsi Jawa Barat. Aceh Anthropological Journal 2022, 6, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathoni, A.; Hartati, N.S.; Wahyuni, H.F.; Rahman, N.; Harmoko, R.; Perwitasari, U. Characterization of cassava starch and its potential for fermentable sugar production. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; Institute of Physics Publishing, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Mhaske, P.; Farahnaky, A.; Kasapis, S.; Majzoobi, M. Cassava starch: Chemical modification and its impact on functional properties and digestibility, a review. In Food Hydrocolloids; Elsevier B.V., 2022; Volume 129. [Google Scholar]

- Haq, F.; Yu, H.; Wang, L.; Teng, L.; Haroon, M.; Khan, R.U.; et al. Advances in chemical modifications of starches and their applications. In Carbohydrate Research; Elsevier Ltd., 2019; Volume 476, pp. 12–35. [Google Scholar]

- Sakhaei Niroumand, J.; Peighambardoust, S.J.; Mohammadi, R. Tetracycline decontamination from aqueous media using nanocomposite adsorbent based on starch-containing magnetic montmorillonite modified by ZIF-67. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, A.; Foroutan, R.; Esmaeili, H.; Peighambardoust, S.J.; Hemmati, S.; Ramavandi, B. Montmorillonite clay/starch/CoFe2O4 nanocomposite as a superior functional material for uptake of cationic dye molecules from water and wastewater. Mater Chem Phys. 2022, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edhirej, A.; Sapuan, S.M.; Jawaid, M.; Zahari, N.I. Preparation and characterization of cassava bagasse reinforced thermoplastic cassava starch. Fibers and Polymers 2017, 18, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Lei, J.; Deng, J.; Lei, Z.; Lei, L.; Xu, X. Existing and potential decontamination methods for radioactively contaminated metals-A Review. Progress in Nuclear Energy 2021, 139, 103854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurau, D.; Deju, R. Radioactive decontamination technique used in decommissioning of nuclear facilities [Internet]. Article in Romanian Journal of Physics. 2014. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280920950.

- Fan, M.; Hu, T.; Zhao, S.; Xiong, S.; Xie, J.; Huang, Q. Gel characteristics and microstructure of fish myofibrillar protein/cassava starch composites. Food Chem. 2017, 218, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Barros, N.R.; dos Santos, R.S.; Miranda, M.C.R.; Bolognesi, L.F.C.; Borges, F.A.; Schiavon, J.V.; et al. Natural latex-glycerol dressing to reduce nipple pain and healing the skin in breastfeeding women. Skin Research and Technology 2019, 25, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condon, J.B. Surface area and porosity determinations by physisorption: Measurement, classical theories and quantum theory; Elsevier, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S. Cooperative adsorption on solid surfaces. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2015, 450, 224–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jannesarahmadi, S.; Aminzadeh, M.; Helmig, R.; Or, D.; Shokri, N. Quantifying Salt Crystallization Impact on Evaporation Dynamics From Porous Surfaces. Geophys Res Lett. 2024, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchese, C.L.; Spada, J.C.; Tessaro, I.C. Starch content affects physicochemical properties of corn and cassava starch-based films. Ind Crops Prod. 2017, 109, 619–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kılınç, Ö.; Toplan, N. Amorf Polimerler. ALKU Journal of Science 2023, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.; Peng, G.; Li, T.; Yu, G.; Deng, S. Au(III) adsorption and reduction to gold particles on cost-effective tannin acid immobilized dialdehyde corn starch. Chemical Engineering Journal 2019, 370, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Bai, R.; Chen, B.; Suo, Z. Hydrogel Adhesion: A Supramolecular Synergy of Chemistry, Topology, and Mechanics. In Advanced Functional Materials; Wiley-VCH Verlag, 2020; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Qamruzzaman, M.; Ahmed, F.; Mondal, M.I.H. An Overview on Starch-Based Sustainable Hydrogels: Potential Applications and Aspects. In Journal of Polymers and the Environment; Springer, 2022; Volume 30, pp. 19–50. [Google Scholar]

- Toader, G.; Stănescu, P.O.; Zecheru, T.; Rotariu, T.; El-Ghayoury, A.; Teodorescu, M. Water-based strippable coatings containing bentonite clay for heavy metal surface decontamination. Arabian Journal of Chemistry 2019, 12, 4026–4034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahrous, S.S.; Mansy, M.S. Experimental study for the decontamination of various surfaces from 99Mo using PVA/Borax/Al(OH)3 strippable hydrogel. Applied Radiation and Isotopes 2024, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahrous, S.S.; Borai, E.H.; Mansy, M.S. Polymeric gel for surface decontamination of long-lived gamma and beta-emitting radionuclides. Applied Radiation and Isotopes 2023, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chousidis, N. Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)-based films: Insights from crosslinking and plasticizer incorporation. Engineering Research Express 2024, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pemerintah Republik Indonesia. Peraturan Presiden Republik Indonesia No. 78 Tahun 2021 tentang Badan Riset dan Inovasi Nasional. 2021; pp. 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Badan Riset dan Inovasi Nasional. PERATURAN BADAN RISET DAN INOVASI NASIONAL REPUBLIK INDONESIA NOMOR 6 TAHUN 2021 TENTANG TUGAS, FUNGSI, DAN STRUKTUR ORGANISASI RISET TENAGA NUKLIR; BRIN Indonesia, 2021; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Badan Riset dan Inovasi Nasional. PERATURAN BADAN RISET DAN INOVASI NASIONAL REPUBLIK INDONESIA NOMOR 1 TAHUN 2021 TENTANG ORGANISASI DAN TATA KERJA BADAN RISET DAN INOVASI NASIONAL; BRIN Indonesia, 2021; pp. 1–127. [Google Scholar]

- Badan Pengawas Tenaga Nuklir. Keputusan Kepala Badan Pengawas Tenaga Nuklir No. 500/IO/Ka-BAPETEN/29-V/2017 tentang Perpanjangan Izin Operasi Reaktor Triga 2000 Bandung; BAPETEN: Jakarta, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tyas, R.L.; Deswandri, D.; Intaningrum, D.; Purba, J.H. RISK ASSESSMENT ON THE DECOMMISSIONING STAGE OF INDONESIAN TRIGA 2000 RESEARCH REACTOR. JURNAL TEKNOLOGI REAKTOR NUKLIR TRI DASA MEGA 2022, 24, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamsyah, R.; Yudhi Pristianto, A.P. INFRASTRUKTUR KESELAMATAN DEKOMISIONING FASILITAS NUKLIR DI INDONESIA. In Prosiding Seminar NasionalTeknologic; BATAN: Serpong, 2017. [Google Scholar]

| Material name | Surface area (m2/gram) | Mean Pore Diameter (nm) | Total Pore Volume (cm3/gram) |

| Powder even cassava | 1202,047 | 0.1774 | 1,064 |

| Starch-glycerol film | 33703.643 | 0.1776 | 2,993 |

| No. | Metal Ions | Concentration solution (ppm) | Values read on the resulting film decontamination of media: | ||

| Glass | Ceramics | Alumunium | |||

| 1. | Aquadest | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | Hg | 10,000 | 6600 | 19957 | 4309 |

| 3. | Pb | 5.000 | 18362 | 6081 | 8552 |

| 4. | Fe | 10.000 | 68419 | 123001 | 111970 |

| 5 | Co | 20.000 | 28761 | 16222 | 64587 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).