Submitted:

20 April 2025

Posted:

21 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Microscope Imaging

2.2. Statistics

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflict of Interest

References

- Strain, W.D.; Paldanius, P.M. Diabetes, cardiovascular disease and the microcirculation. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2018, 17, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutterman, D.D.; Chabowski, D.S.; Kadlec, A.O.; Durand, M.J.; Freed, J.K.; Ait-Aissa, K.; Beyer, A.M. The Human Microcirculation: Regulation of Flow and Beyond. Circ Res 2016, 118, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reitsma, S.; Slaaf, D.W.; Vink, H.; van Zandvoort, M.A.; oude Egbrink, M.G. The endothelial glycocalyx: composition, functions, and visualization. Pflugers Archiv: European journal of physiology 2007, 454, 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poledniczek, M.; Neumayer, C.; Kopp, C.W.; Schlager, O.; Gremmel, T.; Jozkowicz, A.; Gschwandtner, M.E.; Koppensteiner, R.; Wadowski, P.P. Micro- and Macrovascular Effects of Inflammation in Peripheral Artery Disease-Pathophysiology and Translational Therapeutic Approaches. Biomedicines 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.W.; Zullo, J.A.; Liveris, D.; Dragovich, M.; Zhang, X.F.; Goligorsky, M.S. Therapeutic Restoration of Endothelial Glycocalyx in Sepsis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2017, 361, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Berg, B.M.; Vink, H.; Spaan, J.A. The endothelial glycocalyx protects against myocardial edema. Circ Res 2003, 92, 592–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehlhorn, U.; Geissler, H.J.; Laine, G.A.; Allen, S.J. Myocardial fluid balance. European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery: official journal of the European Association for Cardio-thoracic Surgery 2001, 20, 1220–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, B.F.; Chappell, D.; Jacob, M. Endothelial glycocalyx and coronary vascular permeability: the fringe benefit. Basic Res Cardiol 2010, 105, 687–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotides, N.G.; Poledniczek, M.; Andreas, M.; Hulsmann, M.; Kocher, A.A.; Kopp, C.W.; Piechota-Polanczyk, A.; Weidenhammer, A.; Pavo, N.; Wadowski, P.P. Myocardial Oedema as a Consequence of Viral Infection and Persistence-A Narrative Review with Focus on COVID-19 and Post COVID Sequelae. Viruses 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laine, G.A.; Allen, S.J. Left ventricular myocardial edema. Lymph flow, interstitial fibrosis, and cardiac function. Circ Res 1991, 68, 1713–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K.L.; Mehlhorn, U.; Laine, G.A.; Allen, S.J. Myocardial edema, left ventricular function, and pulmonary hypertension. Journal of applied physiology 1995, 78, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pries, A.R.; Secomb, T.W.; Gaehtgens, P. The endothelial surface layer. Pflugers Archiv: European journal of physiology 2000, 440, 653–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, A.; Berkestedt, I.; Bodelsson, M. Circulating glycosaminoglycan species in septic shock. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2014, 58, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrich, M.; Gruss, M.; Weigand, M.A. Sepsis-induced degradation of endothelial glycocalix. ScientificWorldJournal 2010, 10, 917–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, F.M.; Meneses, G.C.; Sousa, N.E.; Menezes, R.R.; Parahyba, M.C.; Martins, A.M.; Liborio, A.B. Syndecan-1 in Acute Decompensated Heart Failure--Association With Renal Function and Mortality. Circ J 2015, 79, 1511–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansson, P.I.; Stensballe, J.; Rasmussen, L.S.; Ostrowski, S.R. A high admission syndecan-1 level, a marker of endothelial glycocalyx degradation, is associated with inflammation, protein C depletion, fibrinolysis, and increased mortality in trauma patients. Ann Surg 2011, 254, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackermann, M.; Verleden, S.E.; Kuehnel, M.; Haverich, A.; Welte, T.; Laenger, F.; Vanstapel, A.; Werlein, C.; Stark, H.; Tzankov, A.; et al. Pulmonary Vascular Endothelialitis, Thrombosis, and Angiogenesis in Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020, 383, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, Z.; Flammer, A.J.; Steiger, P.; Haberecker, M.; Andermatt, R.; Zinkernagel, A.S.; Mehra, M.R.; Schuepbach, R.A.; Ruschitzka, F.; Moch, H. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID-19. Lancet 2020, 395, 1417–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadowski, P.P.; Piechota-Polańczyk, A.; Andreas, M.; Kopp, C.W. Cardiovascular Disease Management in the Context of Global Crisis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2023, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veraldi, N.; Vivès, R.R.; Blanchard-Rohner, G.; L’Huillier, A.G.; Wagner, N.; Rohr, M.; Beghetti, M.; De Agostini, A.; Grazioli, S. Endothelial glycocalyx degradation in multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children related to COVID-19. Journal of Molecular Medicine 2022, 100, 735–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadowski, P.P.; Panzer, B.; Jozkowicz, A.; Kopp, C.W.; Gremmel, T.; Panzer, S.; Koppensteiner, R. Microvascular Thrombosis as a Critical Factor in Severe COVID-19. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wadowski, P.P.; Jilma, B.; Kopp, C.W.; Ertl, S.; Gremmel, T.; Koppensteiner, R. Glycocalyx as Possible Limiting Factor in COVID-19. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 607306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wadowski, P.P.; Hulsmann, M.; Schorgenhofer, C.; Lang, I.M.; Wurm, R.; Gremmel, T.; Koppensteiner, R.; Steinlechner, B.; Schwameis, M.; Jilma, B. Sublingual functional capillary rarefaction in chronic heart failure. Eur J Clin Invest 2018, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadowski, P.P.; Steinlechner, B.; Zimpfer, D.; Schloglhofer, T.; Schima, H.; Hulsmann, M.; Lang, I.M.; Gremmel, T.; Koppensteiner, R.; Zehetmayer, S.; et al. Functional capillary impairment in patients with ventricular assist devices. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 5909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadowski, P.P.; Kautzky-Willer, A.; Gremmel, T.; Koppensteiner, R.; Wolf, P.; Ertl, S.; Weikert, C.; Schorgenhofer, C.; Jilma, B. Sublingual microvasculature in diabetic patients. Microvasc Res 2020, 129, 103971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.H.; Dane, M.J.; van den Berg, B.M.; Boels, M.G.; van Teeffelen, J.W.; de Mutsert, R.; den Heijer, M.; Rosendaal, F.R.; van der Vlag, J.; van Zonneveld, A.J.; et al. Deeper penetration of erythrocytes into the endothelial glycocalyx is associated with impaired microvascular perfusion. PLoS One 2014, 9, e96477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, R.J.; Vink, H.; van Oostenbrugge, R.J.; Staals, J. Sublingual microvascular glycocalyx dimensions in lacunar stroke patients. Cerebrovascular diseases 2013, 35, 451–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dane, M.J.; Khairoun, M.; Lee, D.H.; van den Berg, B.M.; Eskens, B.J.; Boels, M.G.; van Teeffelen, J.W.; Rops, A.L.; van der Vlag, J.; van Zonneveld, A.J.; et al. Association of kidney function with changes in the endothelial surface layer. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology: CJASN 2014, 9, 698–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machin, D.R.; Gates, P.E.; Vink, H.; Frech, T.M.; Donato, A.J. Automated Measurement of Microvascular Function Reveals Dysfunction in Systemic Sclerosis: A Cross-sectional Study. J Rheumatol 2017, 44, 1603–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donati, A.; Damiani, E.; Domizi, R.; Romano, R.; Adrario, E.; Pelaia, P.; Ince, C.; Singer, M. Alteration of the sublingual microvascular glycocalyx in critically ill patients. Microvasc Res 2013, 90, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groen, B.B.; Hamer, H.M.; Snijders, T.; van Kranenburg, J.; Frijns, D.; Vink, H.; van Loon, L.J. Skeletal muscle capillary density and microvascular function are compromised with aging and type 2 diabetes. Journal of applied physiology 2014, 116, 998–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koning, N.J.; Vonk, A.B.; Vink, H.; Boer, C. Side-by-Side Alterations in Glycocalyx Thickness and Perfused Microvascular Density During Acute Microcirculatory Alterations in Cardiac Surgery. Microcirculation 2016, 23, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poledniczek, M.; Neumayer, C.; Kopp, C.W.; Schlager, O.; Gremmel, T.; Jozkowicz, A.; Gschwandtner, M.E.; Koppensteiner, R.; Wadowski, P.P. Micro- and Macrovascular Effects of Inflammation in Peripheral Artery Disease-Pathophysiology and Translational Therapeutic Approaches. Preprints.org 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlahu, C.A.; Lemkes, B.A.; Struijk, D.G.; Koopman, M.G.; Krediet, R.T.; Vink, H. Damage of the endothelial glycocalyx in dialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 2012, 23, 1900–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wadowski, P.P.; Schorgenhofer, C.; Rieder, T.; Ertl, S.; Pultar, J.; Serles, W.; Sycha, T.; Mayer, F.; Koppensteiner, R.; Gremmel, T.; et al. Microvascular rarefaction in patients with cerebrovascular events. Microvasc Res 2022, 140, 104300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwdorp, M.; Meuwese, M.C.; Vink, H.; Hoekstra, J.B.; Kastelein, J.J.; Stroes, E.S. The endothelial glycocalyx: a potential barrier between health and vascular disease. Curr Opin Lipidol 2005, 16, 507–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panzer, B.; Kopp, C.W.; Neumayer, C.; Koppensteiner, R.; Jozkowicz, A.; Poledniczek, M.; Gremmel, T.; Jilma, B.; Wadowski, P.P. Toll-like Receptors as Pro-Thrombotic Drivers in Viral Infections: A Narrative Review. Cells 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadowski, P.P.; Piechota-Polanczyk, A.; Andreas, M.; Kopp, C.W. Cardiovascular Disease Management in the Context of Global Crisis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netuka, I.; Litzler, P.Y.; Berchtold-Herz, M.; Flecher, E.; Zimpfer, D.; Damme, L.; Sundareswaran, K.S.; Farrar, D.J.; Schmitto, J.D.; Investigators, E.T. Outcomes in HeartMate II Patients With No Antiplatelet Therapy: 2-Year Results From the European TRACE Study. Ann Thorac Surg 2017, 103, 1262–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tromp, J.; van der Pol, A.; Klip, I.T.; de Boer, R.A.; Jaarsma, T.; van Gilst, W.H.; Voors, A.A.; van Veldhuisen, D.J.; van der Meer, P. Fibrosis marker syndecan-1 and outcome in patients with heart failure with reduced and preserved ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail 2014, 7, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curry, F.E.; Michel, C.C. The Colloid Osmotic Pressure Across the Glycocalyx: Role of Interstitial Fluid Sub-Compartments in Trans-Vascular Fluid Exchange in Skeletal Muscle. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasques-Novoa, F.; Angelico-Goncalves, A.; Alvarenga, J.M.G.; Nobrega, J.; Cerqueira, R.J.; Mancio, J.; Leite-Moreira, A.F.; Roncon-Albuquerque, R., Jr. Myocardial oedema: pathophysiological basis and implications for the failing heart. ESC Heart Fail 2022, 9, 958–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Targosz-Korecka, M.; Kubisiak, A.; Kloska, D.; Kopacz, A.; Grochot-Przeczek, A.; Szymonski, M. Endothelial glycocalyx shields the interaction of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein with ACE2 receptors. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 12157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Illibauer, J.; Clodi-Seitz, T.; Zoufaly, A.; Aberle, J.H.; Weninger, W.J.; Foedinger, M.; Elsayad, K. Diagnostic potential of blood plasma longitudinal viscosity measured using Brillouin light scattering. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2024, 121, e2323016121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretorius, E.; Vlok, M.; Venter, C.; Bezuidenhout, J.A.; Laubscher, G.J.; Steenkamp, J.; Kell, D.B. Persistent clotting protein pathology in Long COVID/Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC) is accompanied by increased levels of antiplasmin. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2021, 20, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotides, N.G.; Zimprich, F.; Machold, K.; Schlager, O.; Muller, M.; Ertl, S.; Loffler-Stastka, H.; Koppensteiner, R.; Wadowski, P.P. A Case of Autoimmune Small Fiber Neuropathy as Possible Post COVID Sequelae. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotides, N.G.; Poledniczek, M.; Andreas, M.; Hulsmann, M.; Kocher, A.A.; Kopp, C.W.; Piechota-Polanczyk, A.; Weidenhammer, A.; Pavo, N.; Wadowski, P.P. Myocardial Oedema as a Consequence of Viral Infection and Persistence-A Narrative Review with Focus on COVID-19 and Post COVID Sequelae. Preprints.org 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Bohm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Celutkiene, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. 2023 Focused Update of the 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 2023, 44, 3627–3639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mach, F.; Baigent, C.; Catapano, A.L.; Koskinas, K.C.; Casula, M.; Badimon, L.; Chapman, M.J.; De Backer, G.G.; Delgado, V.; Ference, B.A.; et al. 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Eur Heart J 2020, 41, 111–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, B.; Agarwal, R.; Anker, S.D.; Ruilope, L.M.; Rossing, P.; Ahlers, C.; Brinker, M.; Joseph, A.; Lambelet, M.; Lawatscheck, R.; et al. Association of Finerenone Use With Reduction in Treatment-Emergent Pneumonia and COVID-19 Adverse Events Among Patients With Type 2 Diabetes and Chronic Kidney Disease: A FIDELITY Pooled Secondary Analysis. JAMA Netw Open 2022, 5, e2236123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Follow up period of one year | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Death n=10 | Overall Survival n=40 | p-Value | |

| Age | 69 (62-76) | 70 (59- 77) | 0.952 |

| Sex (m/f) | 8/2 | 36/4 | 0.384 |

| BMI | 29 (24- 32) | 28 (24-32) | 0.574 |

| Fibrinogen (g/L) | 4.2 (3.6 -4.7) | 4.0 (3.6-4.6) | 0.700 |

| Leukocytes (*109/L) | 7.7 (6.5 -9.0) | 7.6 (6.3 -9.1) | 0.849 |

| Platelets (*109/L) | 215 (162 -255) | 200 (180-238) | 0.926 |

| NT-proBNP (pg/mL) | 4005 (2826- 7937) | 2599 (1527-4549) | 0.201 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 42.6 (37.3- 45.3) | 43.4 (40.4- 45.3) | 0.925 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (µmol/s·l) | 0.28 (0.21-0.32) | 0.37 (0.28-0.48) | 0.019 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (µmol/s·l) | 0.35 (0.28 -0.45) | 0.43 (0.32-0.50) | 0.138 |

| Total bilirubin (µmol/L) | 9.9 (5.9 -16.9) | 12.3 (7.2 -19.9) | 0.586 |

| C- reactive protein (mg/L) | 4.2 (3.1 -7.5) | 5.3 (1.7 -8.9) | 0.780 |

| Serum creatinine (µmol/ L) | 115.8 (98.6- 333.3) | 120.7 (95.3 - 176.8) | 0.432 |

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate (ml/min) | 50.2 (17.1 -62.4) | 51.5 (33.1- 73.4) | 0.343 |

| Follow up period of two years | |||

| Overall Death n=16 | Overall Survival n=34 | p-Value | |

| Age | 74 (65-80) | 70 (57-75) | 0.134 |

| Sex (m/f) | 14/2 | 30/4 | 0.941 |

| BMI | 28.2 (24.6 -31.5) | 27.9 (24.1-32.3) | 0.803 |

| Fibrinogen (g/L) | 4.2 (3.7-5.0) | 4.0 (3.5-4.5) | 0.174 |

| Leukocytes (*109/L) | 7.7 (6.4- 9.2) | 7.6 (6.1-8.8) | 0.542 |

| Platelets (*109/L) | 215 (176-244) | 196 (178-240) | 0.706 |

| NT-proBNP (pg/mL) | 4693 (3377- 11425) | 2202 (1483-4243) | 0.004 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 41.6 (37.4- 44.3) | 44.2 (40.9- 45.9) | 0.037 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (µmol/s·l) | 0.28 (0.23-0.35) | 0.37 (0.28-0.49) | 0.033 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (µmol/s·l) | 0.35 (0.28-0.48) | 0.43 (0.30-0.50) | 0.275 |

| Total bilirubin (µmol/L) | 10.6 (7.4-16.9) | 12.2 (6.8 -20.3) | 0.881 |

| C- reactive protein (mg/L) | 7.3 (3.9-1.7) | 3.5 (1.6-7.9) | 0.026 |

| Serum creatinine (µmol/ L) | 165 (108-294) | 113 (95 -151) | 0.066 |

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate (ml/min) | 38.8 (19.5-56.1) | 56.8 (42.2-75.8) | 0.045 |

| Follow up period of one year | |||

| Overall Death n=10 | Overall Survival n=40 | p-Value | |

| PBR (µm) | 2.05 (1.88-2.14) | 1.87 (1.66 -2.03) | 0.042 |

| RBC filling % | 71 (70-74) | 74 (71-78) | 0.087 |

| Functional capillary density (µm/mm2) | 2732 (1820-3141) | 2407 (2085-2736) | 0.369 |

| Total capillary density (µm/mm2) | 3525 (2410-6435) | 3538 (3043-4497) | 0.971 |

| Ratio (%) | 73 (60-85) | 71 (57 -76) | 0.331 |

| Follow up period of two years | |||

| Overall Death n=16 | Overall Survival n=34 | p-Value | |

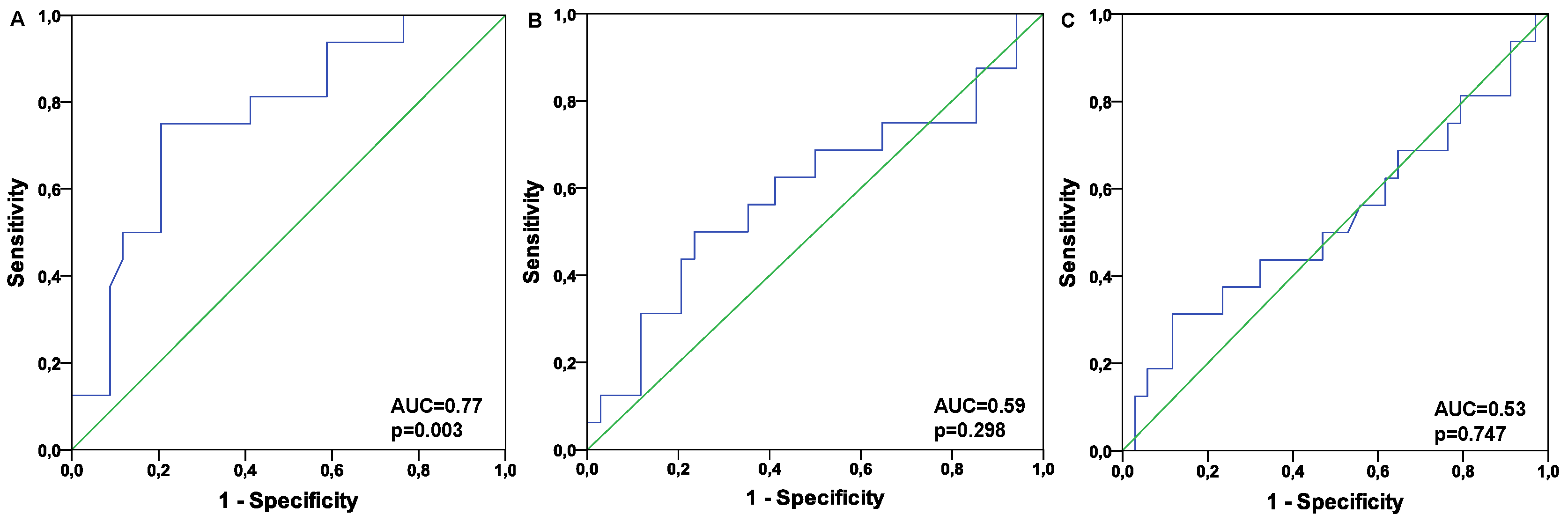

| PBR (µm) | 2.04 (1.93-2.11) | 1.84 (1.62-1.97) | 0.003 |

| RBC filling % | 71 (70-74) | 75 (71-79) | 0.028 |

| Functional capillary density (µm/mm2) | 2630 (2028-2974) | 2403 (2068-2688) | 0.298 |

| Total capillary density (µm/mm2) | 3568 (2963-5339) | 3538 (3021-4397) | 0.747 |

| Ratio (%) | 73 (57-78) | 71 (57 -77) | 0.771 |

| One year | Two years | |||||

| B | CI | P | B | CI | P | |

| PBR | 4.8 | 0.5-27684 | 0.087 | 5.5 | 1.4-38820.5 | 0.036 |

| Functional capillary density | 0.03 | 1.0-1.1 | 0.083 | 0.3 | 1.0-1.1 | 0.048 |

| Total capillary density | -0.01 | 0.98-1.0 | 0.149 | -0.01 | 0.98-1.0 | 0.064 |

| NT-proBNP | 0 | 1.0-1.0 | 0.487 | 0.0 | 1.0-1.0 | 0.489 |

| Creatinine | -0.002 | 0.98-1.0 | 0.762 | -0.01 | 0.98-1.0 | 0.224 |

| C- reactive protein | -0.05 | 0.4-2.6 | 0.915 | 0.3 | 0.8-2.6 | 0.285 |

| Albumin | 0.1 | 0.8-1.6 | 0.448 | -0.03 | 0.8-1.2 | 0.793 |

| Alanine aminotransferase | -8,3 | 0.0-5.0 | 0.101 | -4.9 | 0-2.5 | 0.099 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).