1. Introduction

Data mining is a subfield of artificial intelligence and data analysis that is concerned with extracting useful information from large sets of data [

1]. Through advanced methods, one can establish frequent patterns, unknown relationships, and trends that can be utilized for making informed decisions. Data mining algorithms find extensive applications in diverse areas like business, medicine, finance, and cybersecurity. Association analysis [

2] is a basic data mining technique that allows to find frequent associations between items in transactional databases. The method uses two important measures: support and confidence. Support is an estimate of the frequency of an itemset occurring in the database, and confidence is an estimate of the probability that one item occurs together with another item [

3]. An itemset is classified as frequent if its support exceeds or meets the user-defined threshold value. Association rule mining [

2] generally comprises two distinct steps. Frequent itemsets are identified first based on the support threshold, and association rules are constructed in the second step, with rules with confidence values lower than a user-defined minimum threshold being eliminated to ensure their significance [

4]. These techniques assist in removing non-significant relations and keeping just those with real analytical importance. An association rule is derived from an itemset I = {i

1, i

2, i

3,., i

n}, where I is a set of distinct items. A transactional database DB = {T

1, T

2, T

3,., T

m} contains a set of transactions, and each transaction is a subset of items in I. An association rule is represented as X → Y, where X and Y are subsets of I, satisfying the condition X ∩ Y = ∅, i.e., X and Y have distinct elements. Here, X is the antecedent (the preceding items), and Y is the consequent (the items related to X).

Various algorithms have been suggested to mine these kinds of rules, e.g., Apriori [

3], Apriori-TID [

3], and FP-Growth [

4]. The Apriori algorithm adopts an iterative approach to discover frequent itemsets through the utilization of the anti-monotonicity property of patterns. Its greatest drawback, nonetheless, is the need for multiple scans of the database that significantly increases computational costs. A more efficient version, Apriori-TID, minimizes these scans by organizing transactions into preprocessed sets, thereby conserving memory. The FP-Growth algorithm, on the other hand, presents the tree-based data structure called the FP-Tree to make frequent pattern mining possible in a memory-efficient way without generating candidates. The algorithm is inefficient, however, when there are a very large number of distinct items and trees become memory-intensive to handle. The Eclat algorithm [

5] enhances the itemset mining via iterative intersections, and the High Utility Itemset Mining (HUIM) approach [

6,

7] takes into account the frequency and value of the items.

Further studies have highlighted the necessity for taking special measures over specific fields in order to avoid the production of misleading or irrelevant rules. Additionally, they propose a multi-dimensional methodology for a more insightful analysis of associations, i.e., lift, conviction, leverage, and correlation [

8], to further enhance the ranking or filtering of rules. Other advancements involve constraint-based mining [

3], which incorporates user-specified knowledge to constrain the search space. More recently, information theory-based approaches (e.g., mutual information) [

9] have been applied to quantify the interdependence between itemsets. These approaches are designed to minimize output size but emphasize the most significant rules. There is also increasing acknowledgment in the literature that not all frequent co-occurrences are of equal relevance or usefulness. Additional studies [

10] suggest that the selection of measures is extremely application-dependent, and there is no single measure that works well across all situations. The authors support a combined approach involving both quantitative measures and qualitative observations to enhance the quality and usefulness of the resulting models. Some researchers argue for the importance of semantic relevance and specificity in choosing rules—favoring rules that exhibit strong directional orientation or interpretability, instead of mere statistical correlation [

11,

14]. Nonetheless, this perspective remains inadequately explored in traditional association rule mining processes, which tend to favor quantity over clarity [

10]. The current study concentrated on meticulous refinement of association rule mining algorithms. Mudumba and Kabir [

15] suggest a hybrid approach of various association rule mining techniques with focus on how the performance measures like memory and execution time influence data mining performance. Pinheiro et al. [

16] present the use of association rule mining for enterprise architecture analysis, emphasizing the role of evaluation measures in determining interesting relationships in organizational databases. In a different work, Antonello et al. [

17] present a novel measure for determining the effectiveness of association rules for discovering functional dependencies, which overcomes the drawbacks of conventional measures such as lift and suggests an improved way of quantifying relationships between items. Alhindawi [

18] provides an exhaustive comparison of association rule mining with classification methods, detailing the impact of various measures (support, confidence, specificity) on the usefulness and accuracy of the induced rules.

In spite of significant advances in the research of association rule mining, the discipline continues to be confronted with several fundamental challenges. Traditional algorithms like Apriori and FP-Growth are based on pre-specified support and confidence thresholds, which in many cases are not well correlated with the data distribution. Consequently, the method will generate too many redundant rules when the thresholds are set too low, or miss some interesting associations when the thresholds are set too high. In addition, these algorithms concentrate only on frequency-based measures and hence neglect other important criteria such as semantic relevance, interpretability, and redundancy reduction. Also, they incur high memory and combinatorial explosion in candidate generation, which diminishes their efficiency in adapting dynamically to data variability and in generating rule sets that are compact and meaningful.

To address these limitations, this study proposes a novel approach to the extraction and incremental filtering of association rules, referred to as DMAR (Dynamic Mining of Association Rules). DMAR is designed to generate a compact, interesting, and interpretable set of rules. In contrast to traditional techniques that extract a huge set of rules in a single shot, DMAR relies on a multi-phase methodology incorporating dynamic selection mechanisms at each phase of the process. The DMAR algorithm is developed by extracting frequent meta-patterns, which are evaluated by a stability score to eliminate unreliable structures. A filtering by mutual information is then applied with a dynamic threshold adapted to the properties of the dataset, to retain only the most informative associations. The generated rules are then subjected to a filtering process through a dynamically adjusted confidence threshold, and optimizing via an additional complementary measure, one which preserves logically consistent association rules. The multi-stage strategy is effective in eliminating redundancy and enhancing the semantic quality of the rules while being scalable with large amounts of data. The algorithm is evaluated on various datasets to assess its impact on the quality, interpretability, and redundancy of the rules. The results suggest that an adaptive and contextual evaluation of the rules can significantly improve the relevance of the extracted knowledge and reduce computation time and memory usage, particularly in applications where interpretability and decision support are essential.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 introduces the methods of the proposed algorithm.

Section 3 outlines the results obtained.

Section 4 provides a discussion of the results and presents future research directions. Finally,

Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Methods

In this section, we provide our algorithm DMAR (Dynamic Mining of Association Rules), an adaptive rule filtering, statistical assessment integrating structural pattern optimization with statistical validation. DMAR presents a dynamic and intelligent filtering mechanism impacting selection criteria in terms of dataset features. Our algorithm is described by five prominent phases:

Phase 1- Extraction of Meta-Patterns:

Effective identification of relevant patterns is made possible by a hierarchical arrangement of transactions.

Each meta-pattern acquires a stability score to filter insufficient or inconsistent relations.;

Phase 2- Mutual Information-based filtering:

DMAR examines the real statistical relationship between items instead of depending just on frequency-based measurements.

This approach removes arbitrary or minor patterns that usually coexist without any important correlation.

Phase 3- Adaptive and Dynamic Thresholding:

DMAR dynamically changes this criterion depending on the variance of mutual information values, unlike conventional algorithms using a fixed support threshold.

This adaptive filtering lowers noise in the result and increases the relevance of obtained rules.

Phase 4- Generating Association Rules:

Extracted from validated meta-patterns are candidate rules.

Each rule is assessed using important measure, including confidence, therefore maintaining the identification of excellent relationships.

A dynamic filtering mechanism remains just the most important rules.

Phase 5- Refining Association Rules:

We discuss each phase in detail by providing a detailed explanation of the mathematical principles supporting our approach.

2.1. Extracting Meta-Patterns

The DMAR (Dynamic Mining of Association Rules) algorithm is based on the meta-pattern extraction. This stage is designed to effectively organize the dataset, optimize the identification of frequent itemsets, and reduce computational cost by establishing an efficient structure. DMAR uses hierarchical structuring to combine regularly co-occurring items into meta-patterns, unlike conventional techniques as Apriori and FP-Growth, which produce an extensive number of itemset candidates and need numerous scans of the dataset. Association rule mining is more scalable since this method reduces duplication and enhances computing performance.

Building a transaction tree initially permits condensing and orderly arranging the dataset. Item frequency determines each transaction’s sorting; frequent prefixes are combined into a hierarchical tree. Like the FP-Tree structure [

4], this structuring method drastically lowers redundancy while frequently occurring patterns are grouped together rather than handled individually for each occurrence. Using this tree-based compression assists the technique in improving processing performance by minimizing the number of database scans and memory usage.

DMAR generates candidate meta-patterns by finding itemsets that appear frequently in the structured representation once the transaction tree is built. DMAR uses a more selective strategy, concentrating on patterns showing great co-occurrence and stability, instead of considering all possible subsets as possibilities. Closed itemset mining [

19], where only maximal frequent patterns are retained to decrease redundancy, influenced this technique. This ensures that only significant item combinations are taken into account for additional processing, therefore preventing the exponential expansion of candidates, a typical difficulty in frequent pattern mining.

Promoted by the research of Agrawal et al. [

2] and Han et al. [

4], we employ a score that compares the support of a pattern to its least strong sub-patterns. to refine the selection of meta-patterns. This score enables selecting models without structural coherence in the dataset but maybe frequent. The stability score is computed by the following formula (1):

where Support(X) represents the frequency of a set of elements X in the dataset, and min (Support (Sub-patterns)) corresponds to the lowest support among all subsets of X. The selection criterion is based on a threshold: if the stability score is greater than or equal to 80%, the meta-pattern is retained; otherwise, it is rejected. This choice of an 80% threshold is supported by empirical studies and recommendations from the literature [

20,

21,

10], [

10], to eliminate insufficiently robust patterns while maintaining optimal coverage. This filtering mechanism confirms that only stable, recurrent, and representative patterns are maintained for the next phase of the algorithm. This concept corresponds with the measures of interest applied in data mining [

8], where filtering based on the stability and coherence of patterns boosts the quality of the extracted rules.

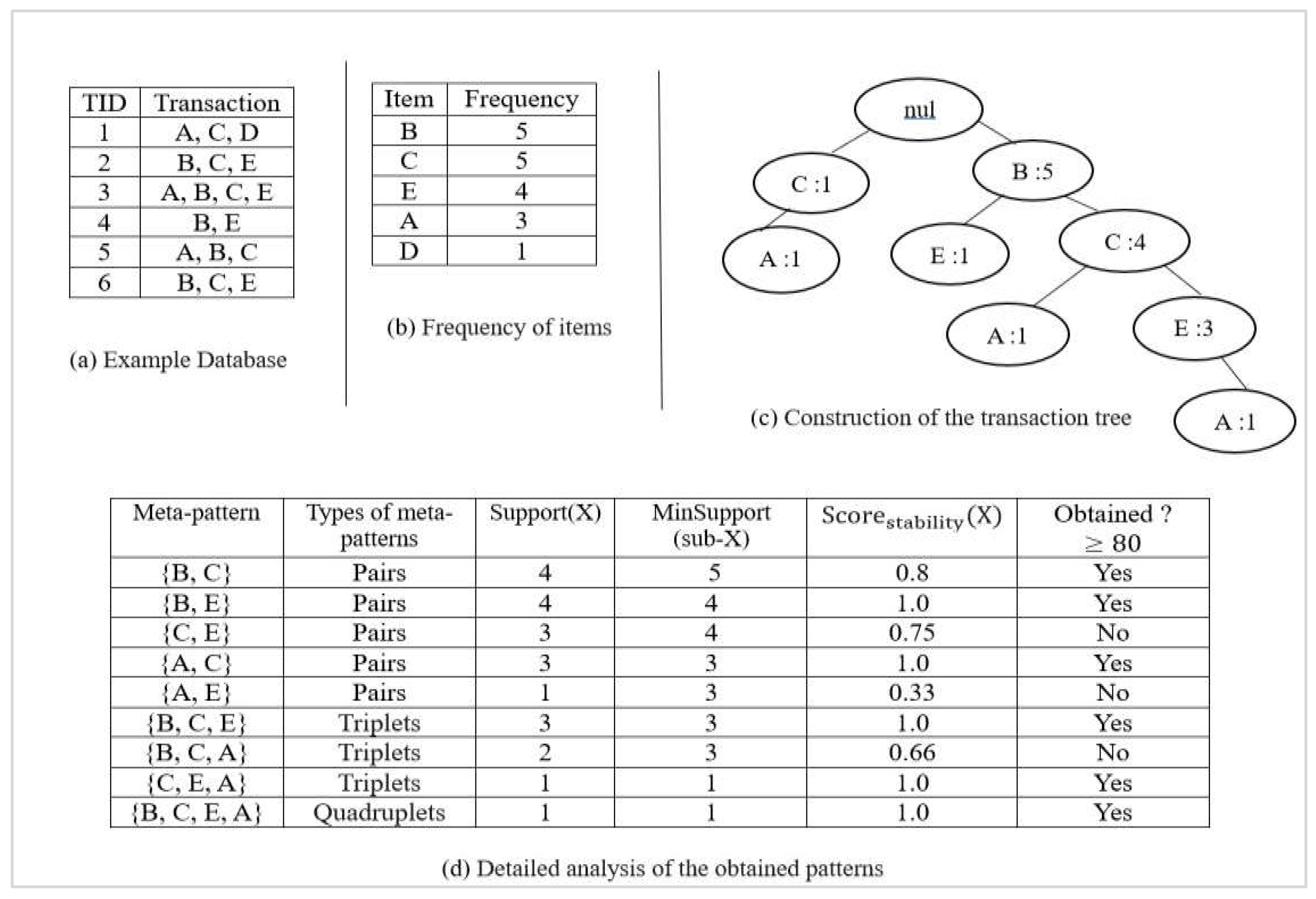

Let a transactional database be shown in

Figure 1a and apply the DMAR method to illustrate the extraction of meta-patterns employing a stability threshold of 80%.

Figure 1b displays the frequency calculation of each item in the database with a minimum support of 2, thereafter a hierarchical transaction tree is constructed in

Figure 1c according to the descending order of frequencies as an FP-tree.

Figure 1d provides a detailed analysis of the obtained patterns and their stability. It presents the different types of meta-patterns, classified into pairs (itemsets of size 2), triplets (size 3), and quadruplets (size 4), thus allowing for the observation of their evolution. For each meta-pattern, the table displays its support, which related to the number of transactions in which it appears, and additionally the minimum support of its sub-patterns, used to calculate the stability score. A meta-pattern is retained as stable and strong if its stability score is either more than or equal to 80%. Conversely, it is deleted if its score falls below this level since it is considered as too unstable or negligible for association rule extraction.

The meta-pattern extraction phase provides an organized, fast, and scalable technique for detecting frequent itemsets. The structured patterns acquired from this stage operate as a foundation for the Mutual Information-based filtering phase, which further benefits the quality of the extracted associations.

2.2. Mutual Information-Based Filtering

Following the stability score (≥ 80%), we first extract and filter the most stable meta-patterns; then, we proceed to the next phase: Mutual Information-based filtering. This stage requires improving the selection of patterns by removing those frequently associated but statistically independent and maintaining just the most significant associations between items. Widely employed in data mining and machine learning [

8] Mutual Information (MI) is a basic measure in information theory [

22] allowing the evaluation of statistical dependency between two items in a transaction. Unlike classical techniques based on support and confidence, which are constrained to the frequency of item occurrence. MI permits assessing the real strength of the relationship between items, surpassing simple frequency. It measures the degree of information one itemset offers about another, that is, how significantly the existence of a single element in a transaction affects the presence of another related item.

Two items A and B possess Mutual Information described as formula (2) [

22]:

P (A, B) denotes the probability that A and B appear together in a transaction. The marginal probabilities of A and B separately are P(A) and P(B).

The Mutual Information allows quantifying the relationship:

If I (A, B) >0, then A and B are statistically correlated, and their relationship is substantial.

If I (A, B) ≈0, then A and B are independent, even if they are frequently associated.

If I (A, B) <0, then the presence of A lowers the probability of the presence of B, which is rarely relevant in association rule mining.

Cover and Thomas [

22] presents generally the Mutual Information for a pattern of N items {X

1, X

2, X

3,., X

n }, as follows:

where P (

) is the probability of joint occurrence of the N items (Support(X) / Total Transactions) and P (

) denotes the individual probability of each item

(Support (

) / Total Transactions).

Several papers have examined the application of MI in the context of data mining, especially for the selection of important and pertinent patterns [

8]. It especially supports avoiding false positives in association rules, which are typical when only support and confidence are applied. Geng and Hamilton [

10] indeed showed that by remaining just those having a real statistical link, the use of MI enhances the quality of the obtained patterns. Commonly used in feature selection, this method facilitates the removal of irrelevant variables in machine learning [

23]. Our method uses MI applied to meta-patterns following the phase of stability filtering. Retaining only the patterns with a strong statistical correlation provides confidence the derived rules are based on meaningful association relations rather than on just frequent co-occurrences. Filtering by mutual information aims to assess the real strength of the relationships among meta-pattern items. Unlike classical approaches based just on support, MI enables statistical reliance between items to be measured and random associations not significant to be eliminated.

2.3. Adaptive and Dynamic Thresholding

The process for applying a fixed threshold on MI can be constrictive in some situations when the distribution of MI values changes based on the dataset. We therefore employ an adaptive technique motivated by adaptive statistical approaches in data mining [

9], which enables to establish a threshold depending on the dispersion of MI values. We evaluate the central tendency and MI value dispersion in the dataset by calculating the average (μ) and the standard deviation (σ). Particularly for data distribution analysis and population parameter estimation, the average is a frequently employed measure in probability theory and statistics [

24]. Within the context of Mutual Information-based filtering, the average permits assessing the general degree of statistical dependency among the obtained items. It is defined as follows:

The MI value for each pattern is denoted by I (

), and N is the total number of meta-patterns that were considered. This statistic shows the average degree of dependence among the generated items, while the average number of MI values can be heterogeneous [

10], we thus additionally utilize the standard deviation to assess the variability of the identified associations. The standard deviation is defined by:

where a small value of σ denotes homogeneity and close proximity to the average, a large value signifies important dispersion among the produced associations.

We establish a function that is dependent on the variance of the MI values; this allows for automatic threshold change according to the dataset structure, enabling dynamic filtering threshold adjustment. Several works in data mining and machine learning have investigated the concept of an adaptive threshold based on variance, especially for selecting optimal thresholds in classification and clustering techniques [

8] and optimizing interest measurements of association rules [

10]. Our method computes the dynamic threshold based on the following rules:

Based on statistical analysis of deviation and average, this rule conforms with the rules expressed in much research on adaptive interest measures in data mining [

8,

10]. The dynamic threshold’s choice enables one to maximize the pattern selection and adjust to the distribution of dependency values [

8,

10].

Inspired by data mining and machine learning, statistical and empirical approaches guide the selection of thresholds 0.5, 0.3, and 0.1 for the dynamic adaptation of filtering based on mutual knowledge. These thresholds aim to modify the degree of pattern filtering depending on the dispersion of MI values in the dataset so providing an ideal balance between precision and recall of the produced patterns. When the standard deviation σ is small (σ<0.1×μ), it is reasonable to employ a strict criterion (0.5) because the MI values are similar and around the average in this case. A small dispersion suggests that the recovered associations have a rather homogeneous dependence, which facilitates a more exact filtering to maintain just the most significant associations [

8]. Low variance indicates stability of the derived associations in dynamic threshold approaches in classification and data analysis; hence, this kind of strategy is frequently utilized where a stricter selection criterion is needed [

10]. The threshold is set at 0.3 to permit a certain flexibility of the filtering while maintaining adequate selectivity when the variance is moderate (0.1×μ≤ϼ<0.4×μ). In this scenario, the dispersion is sufficient to show a diversity of dependencies between the elements. This method is compatible with the concepts applied in machine learning, where threshold regularization based on variance minimizes too extensive filtering of possibly relevant patterns [

25]. The MI values are greatly distributed when the variance is substantial (σ ≥ 0.4×μ), indicating that some patterns have extremely high values and others very low. In this case, a 0.1 threshold is used to ensure the most relevant patterns as possible while removing extremely low associations. This method minimizes data loss when the distribution of values shows great variability by using the concepts of adaptive threshold optimization [

10].

Table 1 presents the application of filtering based on MI in our example to the meta-patterns extracted following the stability phase, therefore enabling just the most relevant patterns to be retained for association rule extraction.

La

Table 1 includes highly supported meta-patterns with MI below the threshold due to insufficient statistical dependence, even though these patterns have high support. The pattern {B, C}, for instance, has a negative mutual information of (-0.039), suggesting that there is no statistical relationship between the two items, even if it possesses very high support (4 occurrences out of 6 transactions). In the same way, {C, E, A} indicates total independence between these three elements, with a mutual information of zero (0.000) and a very low support (just 1 occurrence). Therefore, these patterns are not taken into account during the association rule extraction process, since they cannot assist in uncovering meaningful relationships. On the other hand, patterns that show strong correlations between the elements and have mutual information greater than the dynamic threshold (0.1) are saved. For instance, {B, E} shows non-randomly occurring together through sporting a MI value of (0.175). Additionally, {A, C} is preserved with a valid association identified by a MI of (0.131). The high mutual information (0.292) of the pattern {B, C, E} indicates a significant association between the three elements. This implies that the simultaneous presence of B and C significantly influences that of E, so validating their choice for the future stages of the process. The decision to retain or remove {B, C, E, A} is also based on its final MI value. If it’s higher than the dynamic threshold, it will be adopted; else, it will be removed.

This Mutual Information-based filtering facilitates identifying only meaningful patterns, therefore removing random or non-significant correlations. This method assures a more consistent and interpretable rule extraction, thus eliminating the irrelevant associated with frequent co-occurrences.

2.4. Association Rule Generation

After the discovery of robust meta-patterns, the subsequent task is the generation of significant association rules and the employment of a dynamic refining process for retaining only the rules with high informative content. The aim of such an approach is to ensure that the rules chosen are not merely distinguished on the basis of frequency, but also effectively detect true dependence patterns between the items.

Association rules are derived from the meaningful patterns that were discovered previously. Each meta-pattern can be decomposed into several structured rules in the form of: X→Y. where X is a subset of the model, and Y includes the other elements. For example, from the meta-pattern {B, E}; rule extraction produces the relations B→E and E→B. The aim is to mine the rules with a high level of reliability, as quantified using the following measures:

Support [

2]: Estimates the frequency of occurrence of the rule within the set of transactions

Confidence [

2]: Estimate the probability that Y will be visible when X is present by following formula

After the association rules have been generated, it is crucial to use a last filtering step that retains only those with a high value of information. The standard techniques for selecting rules for association are based on predetermined threshold (e.g., confidence ≥50 %), which is ineffective when the distribution of the measures is very different from one dataset to another [

8]. Indeed, low variance in confidence values indicates that the majority of the rules have comparable values and hence can be subjected to a strict threshold. Conversely, high variance implies that too stringent a threshold will exclude potentially beneficial rules. To counter this problem, an adaptive threshold is defined on the basis of the average and the deviation of observed values among the induced rules. This method follows the principles of adaptive statistical techniques applied in data mining and machine learning [

10].

We present an approach that adapts the thresholds based on observed confidence average () and standard deviation () values. The aim is to select only the most significant rules, but also considering the distribution of confidence values and not rejecting potentially useful rules just because of a fixed arbitrarily set threshold.

The average (

) is a measure of central tendency used to estimate the average value of the confidence levels observed in the generated association rules [

26]. It is defined as follows:

where N is the total number of rules generated. The standard deviation (σ), however, provides the range of values from the average and may be utilized in examining the degree of variability of levels of confidence [

26]. It is obtained from the formula:

The utilization of the range allows for dynamic adjustment of the thresholds according to variability in the confidence values, avoiding the arbitrary choice of excessively strict or loose thresholds. In particular, thresholds are varied as a function of the ratio

/

,which is a measure of variability in rules produced. The filtration levels are as follows:

This choice is well grounded in the areas of statistical analysis and machine learning. When the variance is reduced ( <0.1×), it averages that confidences are homogenous, which allows us to use a strict threshold (≥0.7) to retain only the most robust rules. Conversely, if the variance is modest (0.1×≤<0.4×), there are strong disparities among a few rules, which call for an intermediate threshold (≥0). Lastly, with high variance (≥0.4×), there are rules with low confidence values and others with high confidence values. In this case, a less stringent threshold (≥0.3) is established to prevent excluding rules that may be relevant despite having slightly below-average confidence.

Previous work in data mining and machine learning thus influences the thresholds 0.7, 0.5, and 0.3 chosen. While Agrawal and Srikant [

3] recommend a minimum threshold of 50% in traditional association rule extraction methods, the investigations by Tan et al. [

8] reveal that typically considered accurate are association rules when their confidence surpasses 70%. Moreover, Geng and Hamilton [

10] suggest the need for a flexible threshold depending on data variance in order to prevent too strict or too flexible rule choosing. Our method thus depends on these concepts by suggesting an adaptive mechanism able to change the threshold depending on the particular properties of the investigated dataset.

Applying this method permits a flexible selection of association rules, ensuring that only those with real value for knowledge are retained. The suggested strategy assures optimal filtering, unlike fixed methods, which can be useless for datasets with a heterogeneous distribution of confidence values.

We applied our dynamic filtering approach to the subsets of meta-patterns retained from

Table 1{B,E},{A,C},{B,C,E} and identified five retained rules that satisfy the criteria of statistical significance and analytical relevance, after producing the association rules and using our computed dynamic threshold (0.5).To guarantee the validity of the findings, the rules with confidence below 0.5 were deleted; additionally, redundant rules were deleted to prevent the repetition of data previously handled by other associations.

The selected rules are: B→E (Confidence: 0.659), E→B (Confidence: 0.604), C→A (Confidence: 0.706), A→C (Confidence: 0.564), B→E, C (Confidence: 0.535).

By employing dynamic filtering techniques, we were able to filter out only the most reliable criteria so that we could perform an optimum analysis while disregarding the associations with small statistical power. The technique allowed to choose just the most frequent or highly correlated rules without reducing the ambiguity or semantic diversity of an association rule.

2.5. Refining Association Rules

The application of support and confidence measures in our algorithm is not enough to assess association rules; they both suffer from major drawbacks in the detailed examination of the logical consistency of these rules. Even though support identifies rules that are frequent, it does not provide a basis for determining the accuracy or specificity of the rule: a rule that is employed frequently may be insignificant or redundant. Confidence, however, calculates the probability that the consequent is present when the antecedent is known, but it fails to consider the variety of outcomes that a single antecedent can produce. A high level of confidence does not, however, ensure that the antecedent is uniquely associated to the considered consequent. If a rule has a confidence of 0.8 and is associated with multiple other consequences with the same confidence, it indicates that confidence alone cannot discover logical dispersion.

To overcome this limitation, we introduce the Target Concentration Measure (TCM) as an auxiliary measure. Whereas confidence computes the probability of Y given X, the TCM is concerned with the distribution of X across all potential Yi. Consequently, it gives the way to quantify the degree to which X is particularly concentrated around Y. In this case, the TCM supplements support and confidence with a structural and comparative component that assists in establishing well-defined rules, which are logically more powerful. The combined application of all three Measures provides a finer-grained and more comprehensive assessment of the induced rules.

Definition of TCM (Target Concentration Measure):

Consider a rule of association labeled R:X→Y, and let

= {

,

,…,

} denote the set of consecutive items

for which there exists a rule of the form X→

. The Target Concentration Measure is defined as follows:

The numerator Support(X∪Y) measures the simultaneous frequency of the sets X and Y.

The denominator represents the total frequency of X occurring with all its potential outcomes.

This measure assesses the proportion of antecedent X to consequent Y in relation to all other potential consequences of X.

Formal demonstration of the validity of the Target Concentration Measure (TCM):

-

Hypothesis

Let D be a collection of transactions, and let a set of association rules be derived in the form X, where X is a subset of I X⊆I, and= {,,…,} is the collection of consequences obtained for the corresponding antecedent X.

We refer to; Support(A) is the count (or percentage) of transactions with itemset A. The expression X∪refers to the co-occurrence of X with a consequence. The aim is to quantify the focus of X towards a target within complete set of.

-

Justification by analogy with a normalized distribution

Partial support vs. conditioned total support: The measure Support(X∪Y) defines the absolute frequency for the co-occurrence of X and Y. Conversely, the sum is the overall frequency of the occurrence of X across all rules produced regardless of the consequent.

Specific vs global ratio: Considering the ratio; / One counts the frequency with which X is directly followed by Y, in relation to all the cases in which X produces some .

This report is a normalized distribution of outcomes with regard to X and thus guarantees a probabilistic interpretation according to the following Lemma 1:

Lemma 1.

Let X be a given antecedent andthe set of consequences for which X

rules have been extracted. Then:

Proof of Lemma 1. By definition of TCM, for each i:

- 3

-

Properties justifying the validity of the formula:

The TCM, as a ratio of frequencies, is bounded in the interval [0, 1], allowing for a consistent interpretation across rules.

Maximality (TCM = 1) is obtained when X is only associated to Y, thus giving proof that the measure successfully detects exclusive concentration.

Minimality (TCM = 0) if X weakly relates to Y; the formula accurately represents logical dispersion.

Invariance in relation to the size of the database is observed because the TCM relies on relative frequencies, thus staying valid irrespective of the number of transactions or density of the DataSets.

The TCM formula incorporates a principle of conditional normalization that ensures an equitable and comparative measure across rules with an identical antecedent. This is unlike traditional measure (e.g., confidence) that emphasizes the degree of focus of an antecedent towards a single consequent, which is important in situations where the interpretability and precision of rules are important.

Proof of Theorem 1. The numerator and denominator of TCM are positive, and the numerator is a component of the sum in the denominator. So, the ratio is necessarily within [0, 1] ⇒ TCM (X→) ∈ [0,1].

Proof of Theorem 1. If X is only followed by

, then:

Conversely, if TCM(X

)=1, then the support of all other

with i≠j must be zero

j,

)=0.

Proof of Theorem 3. If X is distributed across many

, but

is very rare frequent, then:

The perspective offered by TCM is especially useful in situations where an antecedent is implicated in numerous unrelated rules. An individual rule can exhibit high confidence; however, if X is also associated to a number of other results, the rule X⇒Y is logically uncertain and ambiguous. In that instance, only TCM enables the determination of the degree to which Y is favored compared to other consequences and hence makes it possible to identify the most precise or deterministic rules.

To effectively filter the most potential association rules with the Target Concentration Measure (TCM), we apply a dynamic filtering scheme, where the selection threshold is dynamically determined according to the statistical distribution of the scores. The dynamic threshold is formulated as follows: θ=μ+λ⋅σ.

where μ represents the average of the TCM scores, σ their standard deviation, and λ is a selectivity parameter. It is an important parameter as it provides the possibility to modulate filtering stringency according to analytical context and to data variability. The choice of range λ ∈ [0.5, 1.5] is based on solid statistical grounds derived from the empirical rule distribution associated with the normal distribution [

27,

28]. The value of λ is selected according to the stringency level that the selection of the rules requires, combined with the extent of the variability discovered within the data. In fact:

When λ = 0.5, threshold is set at μ + 0.5σ, and it retains approximately 30 to 35% of the most interesting rules. This flexible filtering procedure is especially appropriate at exploratory stages, or in high variance situations where one would like to retain varied candidate rules.

For λ=1.0, the threshold equals μ+σ, retaining approximately 16% of the most promising rules. This default value offers a trade-off between coverage and strictness, appropriate for semi-supervised, decision-making, or explanatory tasks.

Lastly, setting λ=1.5 involves placing the threshold at μ+1.5σ, which represents a statistical area encompassing just 6–7% of the densest rules. This level of stringent filtering is warranted in situations demanding absolute precision, e.g., personalized recommendation, medical diagnosis, or sensitive analysis.

The interval λ ∈ [0.5, 1.5] is giving a systematic degree of flexibility in regard to the threshold selection, supported on a robust statistical basis. It permits the varying strength of the filter to meet specific requirements of use (ranging over exploration, explanation, or recommendation) without compromising the mathematical integrity of the process. This approach eliminates the use of arbitrary thresholds by adhering to the actual score distribution, therefore providing a consistent probabilistic meaning. This method gives the user or the algorithm a degree of control over the density of rules retained, based on the goal of the analysis. The suggested approach is characterized by its generality, statistical validity, and straightforward integration with intelligent rule extraction procedures.

The Target Concentration Measure (TCM), based on dynamic filtering, adds structural and logical information to enable the discrimination of the most consistent rules, enhancing the semantic quality of the associations discovered. TCM is not intended to substitute traditional measures like support and confidence, but tries to supplement them. In fact, whereas support is the general frequency of a given rule within the database, and confidence calculates the probability of Y given X, TCM clarifies another crucial aspect: the specificity of antecedent X with respect to a singular consequent Y. In this way, a rule with both high confidence and high TCM is both probabilistically and precisely defined and therefore has greater explanatory power. On the contrary, a rule having high confidence and low TCM indicates a dispersion of the logical relation, i.e., X tends to have various consequences and therefore renders the rule less informative. The TCM offers a novel perspective of choice founded on discrimination of consequences and consequently is an effective tool for the purposes of explanation for decision-making.

The following

Table 2 gives a comparative overview of methods employed in our research. It emphasizes the explanatory value of the TCM Measure as a supplement to conventional measures, especially in testing the specificity and logical coherence of the rules produced.

The pseudocode of our DMAR (Dynamic Mining of Association Rules) approach is shown in Algorithm 1.

DMAR is based on a five-phase process designed to extract compact and pertinent association rules. The process starts with the organization of transactions into a meta-pattern tree, which is later filtered through a stability score. Then, a mutual information threshold is dynamically adjusted according to the data variance to identify the most significant associations. The rules are initially defined according to chosen meta-patterns and subsequently refined according to confidence measures using a second dynamic threshold. A logical concentration Measure (TCM) then enhances the outcome by giving precedence to rules with high semantic targeting. This method eliminates irrelevant information, enhances logical coherence, and maintains scalability when applied to big datasets.

|

Algorithm 1: DMAR (Dynamic Mining of Association Rules). |

Input:

DB : Transaction Database minsup: Minimum support threshold minMI: Initial minimum Mutual Information threshold minconf: Minimum confidence threshold to validate rules λ ∈ [0.5, 1.5]: Selectivity parameter for dynamic threshold for TCM

|

|

Output:

|

| 1.1 Initialize a Transaction Tree T. |

| 1.2 For each transaction t in DB: |

| Insert into T by merging similar items. |

| 1.3 Extract frequent meta-patterns X with support ≥ . |

1.4 For each meta-pattern X:

Calculate (X) = Support(X) / (Sub-patterns). If StabilityScore (X) ≥ 80%, retain X.

- 2.

Filtering meta-patterns by Mutual Information with Dynamic Threshold:

|

2.1 For each meta-pattern X = {A, B, C, ...}:

Calculate MI, I (A, B, C) = P (A, B, C) * log (P (A, B, C) / (P(A) * P(B) * P(C))).

If I (A, B, C) ≥ minMI, retain X.

|

| 2.2 Calculate the average μ and standard deviation σ of MI values for meta-patterns X. |

2.3 Calculate a Dynamic Adaptive Threshold for each meta-pattern X:

If σ < 0.1 μ, then = 0.5 (Strict threshold).

If 0.1 μ ≤ σ < 0.4 μ, then = 0.3 (Moderate threshold).

If σ ≥ 0.4 μ, then = 0.1 (Strong threshold).

|

|

Retain X. |

- 3.

Generation of Association Rules: |

| 3.1 Initialize R (set of association rules of the form X ⇒ Y). |

3.2 For each meta-pattern X:

Decompose X into possible subsets (A) → (B). Calculate Confidence (A → B) = Support (A, B) / Support(A).

If Confidence (A → B) ≥ , add A → B to R.

- 4.

Dynamic Adjustment of Rule Filtering Threshold:

|

| 4.1 Calculate the average and standard deviation of Mutual Information values for generated rules. |

4.2 Define a Dynamic Adaptive Threshold to filter rules:

If , then = 0.7 (Strict filtering).

If , then = 0.5 (Moderate filtering).

If ≥0.4× , then =0.3 (Strong filtering).

|

| 4.3 Apply this threshold to dynamically filter generated association rules R. |

- 5.

Computing TCM and Filtering Association Rules: |

| 5.1 Group all generated association rules R by their antecedent X |

5.2 For each group of rules with the same antecedent X:

Let , , ..., be all consequents such that for each i∈{1,..,k}, the rule X ⇒ ∈

-

For each rule X →:

= Sum of over all

-

For each rule X ⇒ :

|

| 5.3 Build the list = {TCM(r) for all r ∈ R} |

| 5.4 Compute μ = Average () and Compute σ =Deviation (). |

| 5.5 Compute dynamic threshold θ = μ + λ × σ |

| 5.6 = {r ∈ R | TCM(r) ≥ θ} |

|

Return

|

3. Results

In this section, we present the results obtained from applying our Dynamic Mining of Association Rules (DMAR). We compare the results with that of conventional algorithms such as Apriori and FP-Growth based on several performance measures. We have taken into account 3 crucial factors in Analysis of Results:

Number of rules generated: produce a concise yet pertinent and significant collection of association rules.

Effect of TCM measurement on the logical integrity of rules.

Computational efficiency: Execution time and memory consumption compared to other methods.

The experiments were conducted on a Windows 11 machine with an Intel® Core™ i7-10875H processor clocked at 2.80 GHz, 16 GB RAM, and running Windows 11. The algorithms were implemented in Java with the NetBeans IDE.

3.1. Dataset Overview

Three datasets were selected from the UCI Machine Learning Repository [

29]:

Mushroom Dataset: The dense dataset contains descriptions of ~8,124 mushroom samples, and has ~119 various items. Categorical attributes were converted into transactions, and each feature is considered an item.

Adult Dataset: Also called the “Census Income” dataset, this dense dataset contains ~48,842 instances with ~95 attributes and aims to predict whether a person’s annual income is above $50,000. The numerical attributes were discretized into discrete classes and then translated to transactions.

Online Retail II Dataset: The sparse dataset includes all the transactions carried out between December 1, 2009, and December 9, 2011, by a United Kingdom-based online retailer. It has ~53,628 records with ~5305 attributes. It is typically used for sales pattern detection, customer segmentation, and market basket analysis.

Retail Dataset: This sparse dataset, available at the SPMF website [

30], contains~ 88,162 retail transactions, widely used in frequent pattern mining and association rule mining, and ~16,470 items.

3.2. Analysis of Results

3.2.1. Number of Rules Generated

One of the primary objectives of the DMAR algorithm is to generate a more compact but more relevant set of association rules by pruning those that are too general, redundant, or uninformative. The λ parameter is integral to this task because it enables adaptive adjustment of the threshold selection based on the distribution of the TCM scores, as provided by the following formula: θ=μ+λ⋅σ.

Table 3 presents the summary of the number of final rules generated for varying values of λ, in comparison with the standard Apriori and FP-Growth algorithms, on four different datasets.

The results reveal a consistent and methodical decrease in the number of rules acquired as λ increases:

At λ=0.5, DMAR produces approximately 50% fewer rules compared to Apriori or FP-Growth.

For λ=1.0, this reduction is approximately 65–70%.

With λ=1.5, only 10 to 15% of the initial rules remain.

This implies that the influence of λ is correctly scaled; each increase gives a similar decrease, without any abrupt threshold effect or substantial loss. This effect substantiates the argument that parameter λ is critical in determining selectivity and provides the scope for adjusting the degree of demand according to user or application need. An increase in λ corresponds to a more stringent selection process, which efficiently decreases the total number of rules while preserving the most precise ones.

Analysis by dataset:

Mushroom (defined by density and structure): even at λ=1.5, a high number of rules (615) is still retained, which proves that DMAR preserves the logical consistency of frequent associations and reduces redundancy.

Adult (large base, low density): the contrast between DMAR and Apriori is especially significant. DMAR removes rules that result from opportunistic but not very specific combinations, thereby demonstrating the value of TCM in low semantic concentration data.

Retail and Online Retail II (sparse transactions, long tail): DMAR with λ=1.5 maintains just a nucleus of very specific rules, which is perfect for targeted recommendation systems, where the importance is relevance rather than abundance.

The qualitative advantage compared to Apriori and FP-Growth:

Unlike Apriori and FP-Growth, which considerably generate all possible rules satisfying pre-specified support and confidence levels, DMAR uses several levels of semantic filtering:

Structural meta-pattern filtering

Dynamic Mutual Information Filtering (elimination of uninformative meta-patterns).

Confidence filtering using a threshold computed dynamically from the data.

Filtering by TCM, threshold θ controlled by λ. Even at λ=0.5, DMAR generates considerably less logical noise while still maintaining exploitable rules.

Flexibility to corporate needs:

The λ parameter provides a simple and interpretable tuning:

λ = 0.5 → exploratory tasks, visualization, or human decision support

λ = 1.0 → for evenly balanced use cases (recommendation, labeling, intermediate classification),

λ = 1.5 → for high-stakes scenarios (diagnosis, fraud detection, highly targeted recommendations), where only the highest possible rule quality is acceptable.

The results presented in

Table 3 obviously indicate that application of a λ-based dynamic threshold in the DMAR algorithm allows proper control of the quantity and quality of generated rules. In contrast to the traditional approaches such as Apriori and FP-Growth, which generate numerous unfiltered rules, DMAR uses a multi-stage information- as well as logic parameter-guided filtering mechanism with all the while retaining the provision for as-needed adjustments. This aspect renders DMAR especially appropriate for association mining settings, in which relevance is more desirable than unselective completeness.

3.2.2. Impact of the TCM Measure on the logical quality of the rules

Target Concentration Measure (TCM) was developed to overcome the inherent drawback of conventional approaches: the inability to quantify the logical consistency of a rule beyond frequency or statistical validity. In contrast to popular measures like support and confidence, which consider only the general associations between the antecedent and consequent, TCM concentrates on the capacity of the antecedent to effectively identify one prevailing consequent.

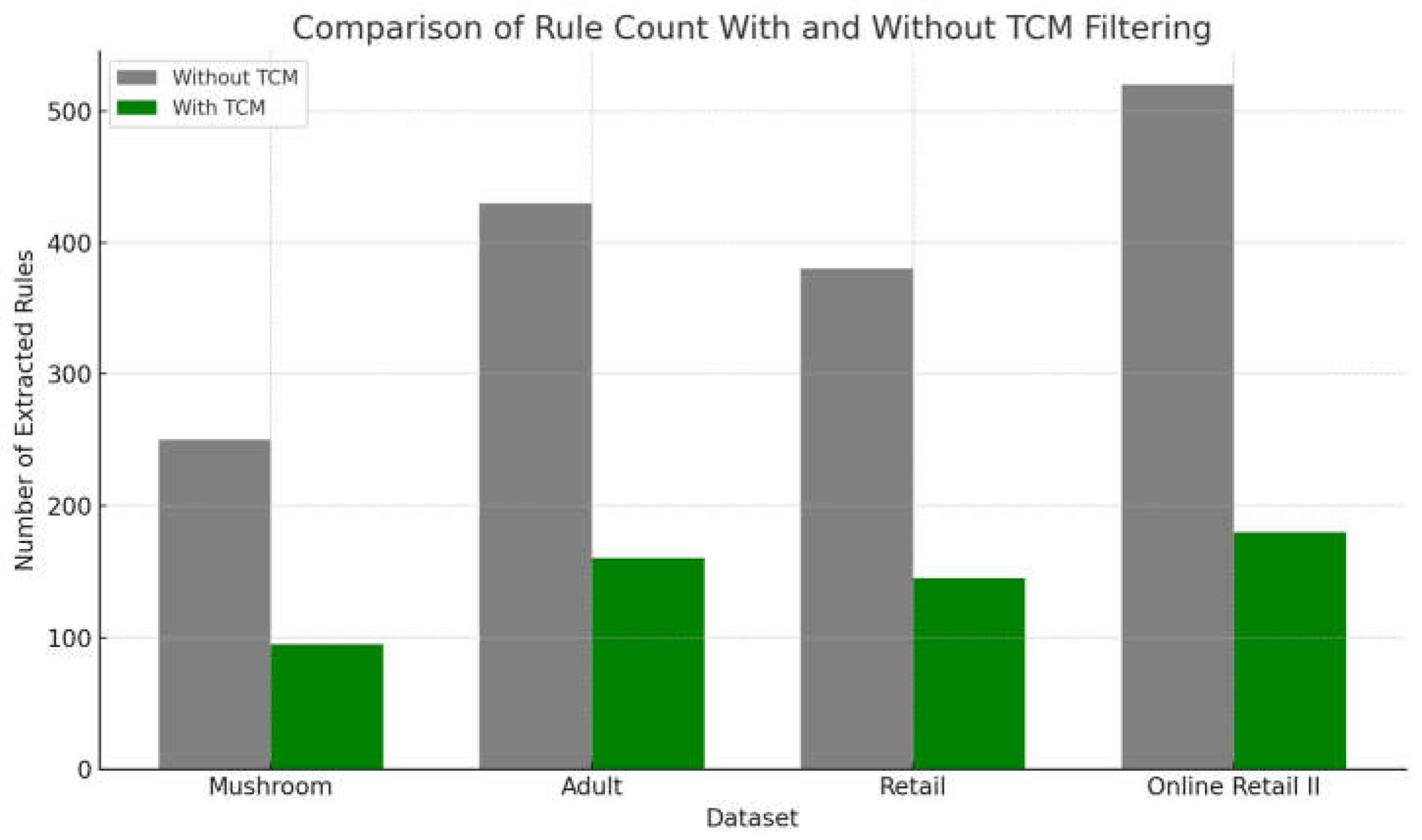

Figure 2 illustrates a graph comparing the number of rules obtained with TCM filtering and those obtained without it. The outcomes indicate a noteworthy decrease in the total number of rules for every dataset, hence demonstrating that TCM is successful in filtering non-specific or weakly focused rules.

The examination of the figure discloses the uniform and remarkable decrease in the quantity of rules extracted following TCM filtering in each dataset. For the Mushroom dataset, the number of rules decreases from 250 to 95, denoting a decrease of more than 60%. For Adult, the count drops from 430 down to 160, whereas Retail drops from 380 to 145, and Online Retail II from 520 to 180. These outcomes show that TCM is able to filter out over half of the rules generated initially, only preserving those with higher logical focus. This remarkable reduction not only reduces the overall output complexity but also increases the relevance and practical applicability of the resulting rules. TCM’s performance is accounted for by the fact that it manages to preserve just those rules that have an extremely high degree of logical coherence, with the antecedent considering primarily a dominant consequent. Through the elimination of redundant, general, or poorly discriminative rules, TCM assists in the production of a smaller, more accurate, and operational rule set. This fact is always realized in datasets of different sizes and levels of sparsity. Hence, the figure not only reveals the ability of TCM to decrease informational noise but also demonstrates its role in the overall quality of the induced rules, enhancing their interpretability and usefulness in decision-making contexts.

3.2.3. Execution Time

The performance of our DMAR algorithm with Apriori and FP-growth varies drastically in the case of the given datasets. We suggest comparing the runtimes of the mentioned algorithms across the 4 datasets.

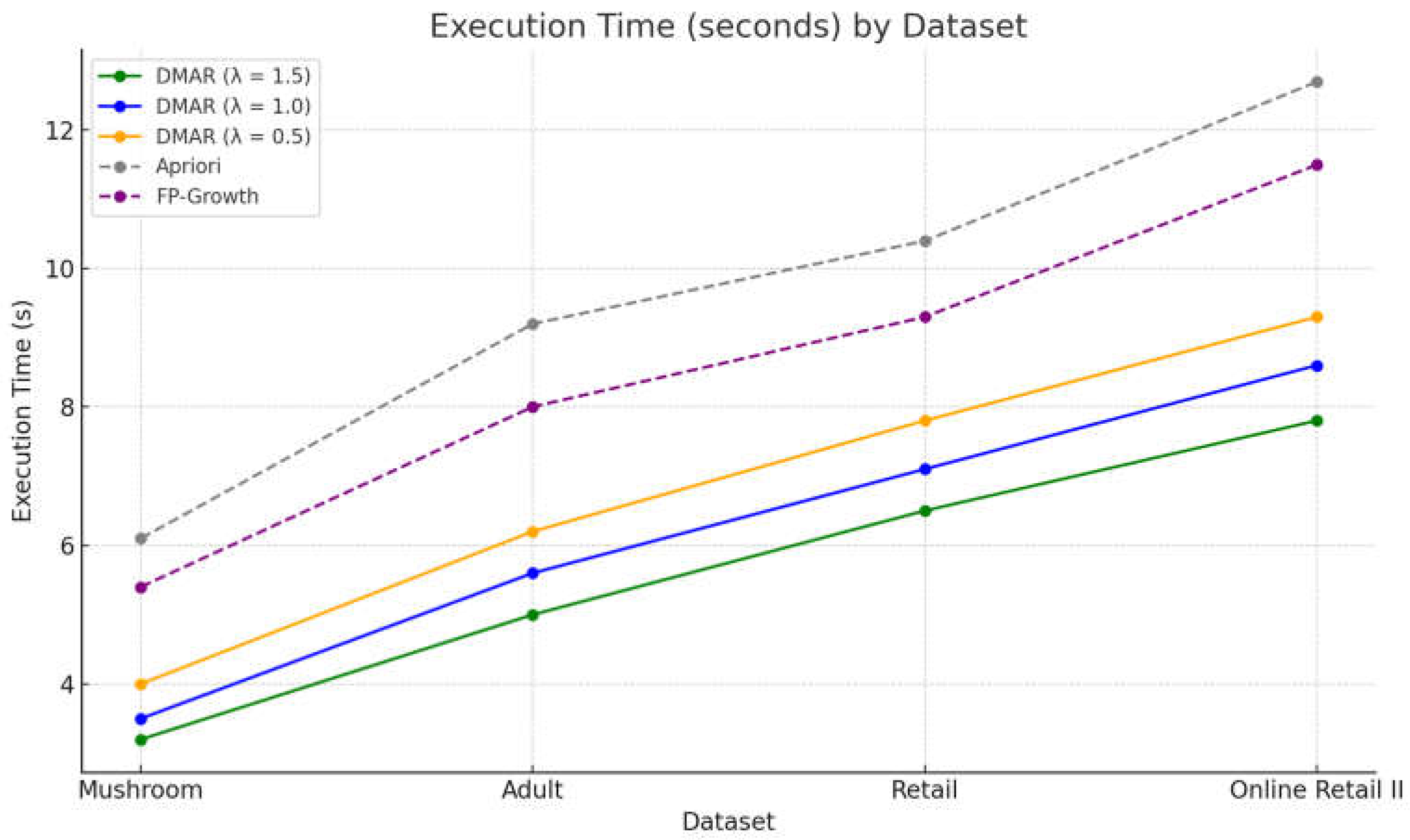

Figure 3 illustrates the execution times (in seconds) of the DMAR algorithm on four benchmark datasets—Mushroom, Adult, Retail, and Online Retail II—for various values of dynamic selectivity parameter λ ∈ {0.5, 1.0, 1.5}. The results are contrasted with the output obtained from the traditional Apriori and FP-Growth algorithms, which are commonly employed in association mining.

The graph indicates a uniform trend in execution time that is based on the type of datasets and filtering level employed by the DMAR algorithm. In the Mushroom dataset, which is characterized by its compactness and denseness, all algorithms register lower execution times. However, DMAR with a high threshold (λ=1.5) is the quickest, taking advantage of highly selective filtering that severely restricts the generation of rules. The performances for λ=1.0 and λ=0.5 exhibit an increasing trend, thereby indicating that a less strict threshold corresponds to a longer processing time. While the Apriori and FP-Growth algorithms are effective for simple scenarios, they are found to be less effective compared to DMAR in this context because of their exhaustive nature.

With the extension of the analysis to the medium-sized Adult dataset, there is a moderate escalation of execution times; yet, the hierarchical character of the structure is relatively stable. DMAR continues to record shorter execution times than FP-Growth, and to an even greater extent, Apriori, whose limits it reveals with the growth in the complexity of the data structure. The control provided by λ continues to demonstrate its impact, with a noticeable prolongation of processing time being registered when the filtering conditions are more permissive.

The impacts are even more noticeable when taking the Retail dataset, which has high sparsity and larger volume. In this situation, the necessity of DMAR reduction processes is even more strongly highlighted. The algorithm efficiently eliminates irrelevant rules early in the process, thereby ensuring a reasonable execution time, even for relatively low λ. FP-Growth and Apriori, however, which do not use this kind of semantic filtering, experience an explosive growth in their computation times.

Lastly, for the Online Retail II dataset, characterized by its enormous size and high sparsity, DMAR shows its capacity to be efficient in high-workload settings. Processing time remains acceptable for every λ value, especially for high-threshold settings. Conversely, both Apriori and FP-Growth reach their limits in this scenario, causing significantly higher execution times as a result of a combinatorial explosion in the number of candidate rules.

In short, the curve displayed evidently demonstrates that DMAR adjusts to the data complexities with an acceptable running time due to its modular structure with dynamic standards and well-defined filtering parameters. Parameter λ is essential in tuning the aggressiveness of the sorting process, and therefore provides fine-grained control between efficiency and quality of the produced rules.

Although it is designed to surpass the speed of Apriori, primarily because of its effective tree structure (the FP-tree), FP-Growth generates all frequent rules systematically without employing any sophisticated filtering techniques.

As a result: On dense datasets (like Mushroom), FP-Growth is efficient, However, in extensive and sparse databases such as Retail or Online Retail II, there are many more rules, causing a significant rise in execution time. Conversely, DMAR integrates multiple mechanisms for volume reduction from the initial point:

Targeted extraction by meta-patterns,

Dynamic Mutual Information Semantic Filtering.

Selection by confidence, also under dynamic control.

Logical filtering by TCM, with a dynamic threshold.

This hierarchical method enables DMAR to greatly decrease the search space, hence the reason why it continues to outperform FP-Growth and Apriori on all data sets even when adding extra analytical steps.

The execution time analysis points out one of DMAR’s most significant advantages: it is an algorithm with semantic robustness as well as performance efficiency, primarily because of its adaptive λ-filtering mechanism. The ability of an algorithm such as DMAR to dynamically adjust analytical depth is very significant since it can then accommodate the data structure and provide an ideal balance between rule quality, processing time, and algorithm scalability.

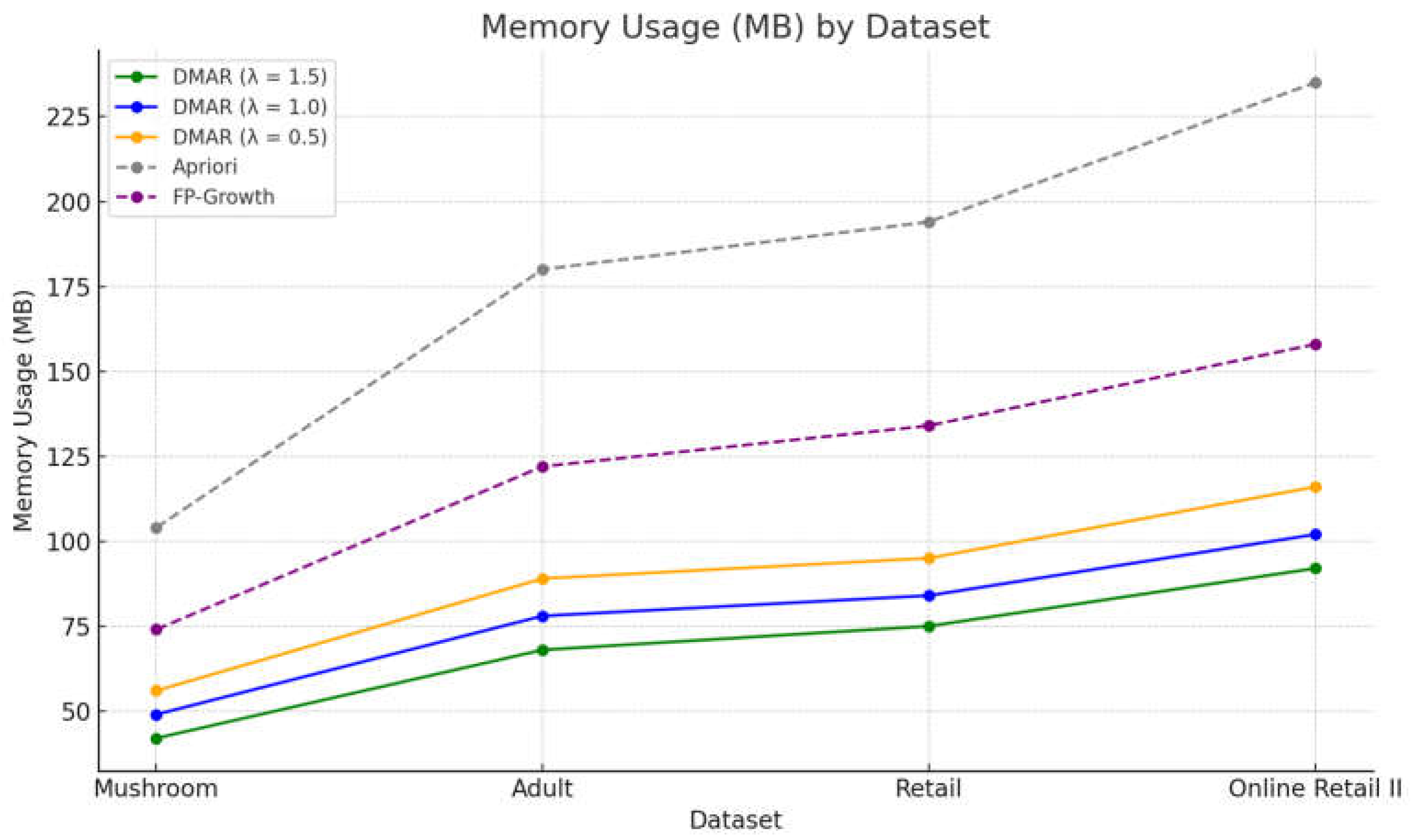

Figure 4 presents a graphical comparison of the memory usage of Apriori, FP-Growth, and DMAR algorithms on various datasets.

On Mushroom, DMAR utilizes 42 MB (λ=1.5) to 56 MB (λ=0.5), whereas FP-Growth utilizes 74 MB and Apriori 104 MB. In Adult, DMAR’s used memory ranges between 68 and 89 MB, while FP-Growth reaches up to 122 MB and Apriori up to 180 MB. On Retail, the memory usage goes up to 75–95 MB for DMAR, 134 MB for FP-Growth, and 194 MB for Apriori. Finally, on Online Retail II, DMAR remains within 92 to 116 MB, whereas FP-Growth reaches up to 158 MB, and Apriori up to 235 MB.

The memory analysis demonstrates dramatic variation among the various algorithms compared. As anticipated, DMAR consumes much less memory compared to the standard Apriori and FP-Growth algorithms, independent of the dataset examined. This is attributable to the multi-level filtering approach of DMAR, which recursively decreases the volume of candidate rules stored in memory through the utilization of a combination of meta-patterns, mutual information, and the Target Concentration Measure (TCM).

The influence of the selectivity parameter λ can be seen clearly here: at λ=1.5, the filtering process is stricter, and less specific rules can be eliminated quickly. This, in turn, results in a reduction in memory usage, even for large databases. With a less strict parameter (λ=0.5), on the contrary, it results in more rule retention and, consequently, in higher memory usage. This adaptive control is a significant benefit of DMAR, as it permits flexible tuning of memory load based on analytic demands.

Among the conventional techniques, the Apriori algorithm is notable for its very high resource consumption, particularly in the Retail and Online Retail II datasets. This excessive overhead is inherent in its mechanism of work, involving candidate itemset generation and testing, which demands the utilization of multiple intermediate structures in memory. While more advanced, the FP-Growth technique also features a high resource demand, as it produces all frequent rules without any allowance for prior reduction or logical organization. Generally, the curve shows how DMAR achieves precise memory control with integrity preserved on the derived rules. The fact that it can adjust to data sizes and complexities makes it a particularly suitable option for settings characterized by small resources or high volume.

3.3. Comparison with Related Algortihm

A comparison between the performance, flexibility, and quality of output of the DMAR, FP-Growth, and Apriori algorithms reveals significant differences in their respective characteristics.

Execution time: DMAR consistently has execution times shorter than FP-Growth, and more significantly, than Apriori. This is because of its iterative filtering design (meta patterns → MI → confidence→ TCM), which precludes the large generation of poor or irrelevant rules, thereby reducing the computational overhead. In contrast, while FP-Growth handles small datasets efficiently, its performance deteriorates with growing dataset size or sparsity. In contrast, however, the Apriori algorithm incurs the largest costs, which are due to its approach of generating and examining all potential itemsets.

Scalability: DMAR is very scalable, especially for large databases such as Retail or Online Retail II. Its efficiency comes from the early pruning of the search space, so it is solid for each combinatorial case. FP-Growth has linear increments in memory usage and processing time when the quantity of frequent patterns grows. Apriori, characterized by its exponential complexity, very rapidly becomes unfeasible for large real-world data sets.

Logical quality of extracted rules: One significant benefit of DMAR is that it can generate rules of high-logical-quality. Through the use of the TCM measure, DMAR tends to support rules that link a single antecedent to a single consequent. This makes it possible to minimize broad rules and ambiguity. FP-Growth and Apriori, in contrast, due to the lack of semantic filtering, tend to generate numerous non-discriminative rules.

Integrated semantic filtering: DMAR particularly incorporates an advanced filtering strategy in which the evaluation of rules is performed according to their structural form (meta-patterns), mutual information, contextual confidence, and logical density computed by TCM. FP-Growth and Apriori only consider support and confidence measures and disregard the semantic context.

Reduction of redundancy: By utilizing several filtering stages, DMAR effectively restricts the production of redundant rules. This aspect is vital in giving concise, readable, and actionable outputs. Apriori and FP-Growth, however, tend to produce numerous variations of rules containing the same information and therefore complicate the subsequent processing.

User control (dynamic λ): The introduction of the parameter λ in DMAR provides the user with a convenient way to dynamically adjust the level of selectivity. It is an effective method to manage the compromise between the number of rules and the targeted level of quality, an operation that is not possible with conventional techniques.

In summary, DMAR excels over traditional methods in all the important dimensions: speed, scalability, qualitative assessment, and flexibility. It is a solid and adaptive solution for association rule mining in applications where the quality and relevance of the knowledge gained are most paramount.

4. Discussion

General interpretation of DMAR’s performance: A detailed comparison of the efficiency of the DMAR algorithm demonstrates that experimental results achieve notable enhancements in computational efficiency and logical consistency of extracted rules, as opposed to current techniques such as Apriori and FP-Growth. In terms of execution time, DMAR excels by effectively lowering the processing expenses, specifically for processing very large datasets (Retail, Online Retail II). This relies on a multi-stage filtering at the high level: the initial discovery of meta-patterns, structuring through Mutual Information (MI) with dynamic thresholding, and ultimately selection through the Target Concentration Measure (TCM). This incremental architecture facilitates the removal of redundant or uninformative rules upstream, thus preventing the computational burden found in traditional methods.

Memory consumption follows a similar trend: DMAR consistently requires less memory than Apriori and FP-Growth. This is evidence of the structural and semantic reductionism built into the algorithm not only saving time but also hardware resources, a precious commodity when dealing with online or distributed analysis situations.

The semantic value of rules and semantic superiority: In addition to its technical performance, DMAR carries an essential qualitative benefit. Through the application of the TCM Measure, it facilitates the extraction of logically meaningful rules, i.e., those for which the antecedent is strongly related to a particular consequent. Such specificity isn’t easily expressed by standard measures such as confidence or lift, which tend to be influenced by biases resulting from high marginal frequencies. The sophisticated extraction procedure of DMAR enables the production of more interpretable rules, which are applicable in decision-making activities and adhere more to the anticipated demands of various application domains, including marketing, healthcare, and recommendations. FP-Growth and Apriori, on the contrary, tend to produce a high number of general rules with minimal value, thereby making them hard to be interpreted by humans and adding noise to computerized systems.

Contextualization in terms of the existing literature: Several earlier efforts have suggested only algorithmic enhancements or new measures aimed at enhancing association rule mining [

4,

31]. Yet, none of these efforts attempt the multi-level strategy incorporating structure, information, and logic, which DMAR accomplishes. Besides, the concept of a dynamic threshold governed by a selectivity parameter λ has not been thoroughly analyzed in earlier academic literature, although there is awareness that adaptive methods are advantageous in a range of contexts [

10,

32]. The novelty of DMAR is essentially that it can integrate statistical features (MI), structural features (meta-patterns), and semantic features (TCM), thereby both improving simultaneously the accuracy and robustness of the generated rules.

Limits and constraints of the approach: In spite of its promising performance, the DMAR method has some limitations. Firstly, the success of the rules partially depends on the quality of the mined meta-patterns in the first place; if they are too general or too specific, the process suffers from a lack of flexibility. Secondly, the selection of the parameter λ, while statistically grounded, can greatly influence the outcome and might need more accurate contextual adjustment. Furthermore, the DMAR algorithm exhibits sensitivity to extreme levels of sparsity, which may result in the premature exclusion of certain significant patterns. Lastly, while the dynamic strategy enhances relevance, it simultaneously adds a degree of tuning complexity for users lacking expertise.

Research perspectives: Numerous extensions can be considered as a follow-up to this study. First, the implementation of DMAR in a distributed setting (using Spark or MapReduce) would enable real-time processing of large-scale datasets. Also, the introduction of dynamic meta-patterns that are responsive to individual profiles or domains would serve to further personalize the mining process. It would also be applicable to examine the integration of TCM with other measures (e.g., causality, stability, business cost) within a multi-criteria scoring system. Lastly, a promising direction for research would be the integration of DMAR with user feedback mechanisms, allowing automatic calibration of thresholds or filters according to the estimated utility of the rules produced.

5. Conclusions

We have introduced in this paper DMAR (Dynamic Meta-pattern Association Rule mining), a novel algorithm for the extraction of interesting association rules, grounded on a hierarchical combination of structural, informational, and semantic filtering processes. Through progressive incorporation of meta-patterns, Mutual Information with dynamic thresholding, and Target Concentration Measure (TCM), DMAR is able to extract rules that are characterized by conciseness, specificity, and interpretability.

The experimental results on four datasets with growing complexity demonstrate that DMAR outperforms traditional methods such as Apriori and FP-Growth significantly in terms of both running time and memory usage. Moreover, the logical adequacy of the extracted rules exhibits considerable improvement, especially regarding emphasis on very dense rules, as quantified by the TCM.

The introduction of the control parameter λ, allowing dynamic and adaptive filtering, offers a further mechanism to tailor completeness versus accuracy to the analytical objectives of the user. This flexibility positions DMAR especially favorably in contemporary data mining settings, where scalability and rule intelligibility have emerged as significant issues.

In spite of the potential, the method has some specific limitations, i.e., concerning the reliance on meta-pattern quality and optimization of parameter λ. Future work may take into account extension in distributed or online settings, as well as incorporation of user input in order to refine filtering criteria for real applications.

Ultimately, DMAR is a valuable addition to the research area of association rule mining, integrating algorithmic correctness, semantic consistency, and dynamic flexibility.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DMAR |

Dynamic Mining of Association Rules |

| MI |

Mutual information |

| TCM |

Target Concentration Measure |

References

- Frawley, W.J.; Piatetsky-Shapiro, G.; Matheus, C.J. Knowledge discovery in databases: an overview. AI Mag. 1992, 13, 57–70. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, R.; Imieliński, T.; Swami, A. Mining association rules between sets of items in large databases. In Proceedings of the 1993 ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data, Washington, DC, USA, 25–28 May 1993; pp. 207–216. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, R.; Srikant, R. Fast algorithms for mining association rules in large databases. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Very Large Data Bases (VLDB), Santiago de, Chile, Chile, 12–15 September 1994; pp. 487–499. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.; Pei, J.; Yin, Y. Mining frequent patterns without candidate generation. In Proceedings of the 2000 ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data, Dallas, TX, USA, 16–18 May 2000; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Zaki, M.J. Fast Mining of Sequential Patterns in Very Large Databases; University of Rochester, Department of Computer Science: Rochester, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Liao, W.K.; Choudhary, A. A two-phase algorithm for fast discovery of high utility itemsets. In Advances in Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; Dai, H., Srikant, R., Zhang, C., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; pp. 689–695. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, C.F.; Tanbeer, S.K.; Jeong, B.S.; Lee, Y.K. Efficient tree structures for high utility pattern mining in incremental databases. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2009, 21, 1708–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, P.-N.; Kumar, V.; Srivastava, J. Selecting the right interestingness measure for association patterns. Inf. Syst. 2004, 29, 293–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brin, S.; Motwani, R.; Ullman, J.D.; Tsur, S. Dynamic itemset counting and implication rules for market basket data. In Proceedings of the 1997 ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data, Tucson, AZ, USA, 13–15 May 1997; pp. 255–264. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, L.; Hamilton, H.J. Interestingness measures for data mining: A survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2006, 38, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silberschatz, A.; Tuzhilin, A. What makes patterns interesting in knowledge discovery systems? IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 1996, 8, 970–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavrač, N.; Flach, P.; Zupan, B. Rule evaluation measures: A unifying view. In Proceedings of the 9th International Workshop on Inductive Logic Programming (ILP 1999), Bled, Slovenia, 24–27 June 1999; Flach, P., Lavrač, N., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999; Volume 1634, pp. 174–185. [Google Scholar]

- Hilderman, R.J.; Hamilton, H.J. Knowledge Discovery and Interestingness Measures: A Survey; University of Regina: Regina, SK, Canada, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lenca, P.; Meyer, P.; Vaillant, B.; Lallich, S. On selecting interestingness measures for association rules: User oriented description and multiple criteria decision aid. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2008, 184, 610–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudumba, B.; Kabir, M.F. Mine-first association rule mining: An integration of independent frequent patterns in distributed environments. Decis. Anal. J. 2024, 10, 100434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, C.; Guerreiro, S.; Mamede, H.S. A survey on association rule mining for enterprise architecture model discovery: State of the art. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2024, 66, 777–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonello, F.; Baraldi, P.; Zio, E.; Serio, L. A novel metric to evaluate the association rules for identification of functional dependencies in complex technical infrastructures. Environ. Syst. Decis. 2022, 42, 436–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhindawi, N. Metrics-based exploration and assessment of classification and association rule mining techniques: A comprehensive study. In Studies in Systems, Decision and Control; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 503, pp. 171–184. [Google Scholar]

- Pasquier, N.; Bastide, Y.; Taouil, R.; Lakhal, L. Discovering frequent closed itemsets for association rules. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Database Theory (ICDT), Jerusalem, Israel, 10–12 January 1999; pp. 398–416. [Google Scholar]

- Zaki, M.J. Scalable algorithms for association mining. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2000, 12, 372–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, S.; Luengo, J.; Herrera, F. Data Preprocessing in Data Mining; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cover, T.M.; Thomas, J.A. Elements of Information Theory, 2nd ed.; Wiley-Interscience: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, H.; Long, F.; Ding, C. Feature selection based on mutual information: Criteria of max-dependency, max-relevance, and min-redundancy. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2005, 27, 1226–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casella, G.; Berger, R.L. Statistical Inference, 2nd ed.; Duxbury Press: Pacific Grove, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R.; Friedman, J. The Elements of Statistical Learning, 2nd ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wackerly, D.D.; Mendenhall, W.; Scheaffer, R.L. Mathematical Statistics with Applications, 7th ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Freund, J.E.; Perles, B.M. Statistics: A First Course, 8th ed.; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.; Pei, J.; Kamber, M. Data Mining: Concepts and Techniques, 3rd ed.; Morgan Kaufmann: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- UCI Machine Learning Repository; University of California, Irvine, School of Information and Computer Sciences: Irvine, CA, USA, 2017. Available online: https://archive.ics.uci.edu/ (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- SPMF: A Java open-source pattern mining library. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2016, 15, 3569–3573, Available online: https://www.philippe-fournier-viger.com/spmf/index.php?link=datasets.php (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Aggarwal, C.C.; Yu, P.S. A new framework for itemset generation. In Proceedings of the 20th ACM SIGMOD-SIGACT-SIGART Symposium on Principles of Database Systems (PODS 2001), Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 21–23 May 2001; pp. 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.; Hsu, W.; Ma, Y. Integrating classification and association rule mining. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (KDD ‘98), New York, NY, USA, 27–31 August 1998; pp. 80–86. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).