Submitted:

18 April 2025

Posted:

21 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Reliable hybrid supervised and unsupervised learning based on LBP-BoVW features for minimizing error rate.

- Built a new algorithm for reliable learning on image datasets.

- Employ the Apriori algorithm for selecting the robust features and dimensionality reduction.

2. Materials and Methods

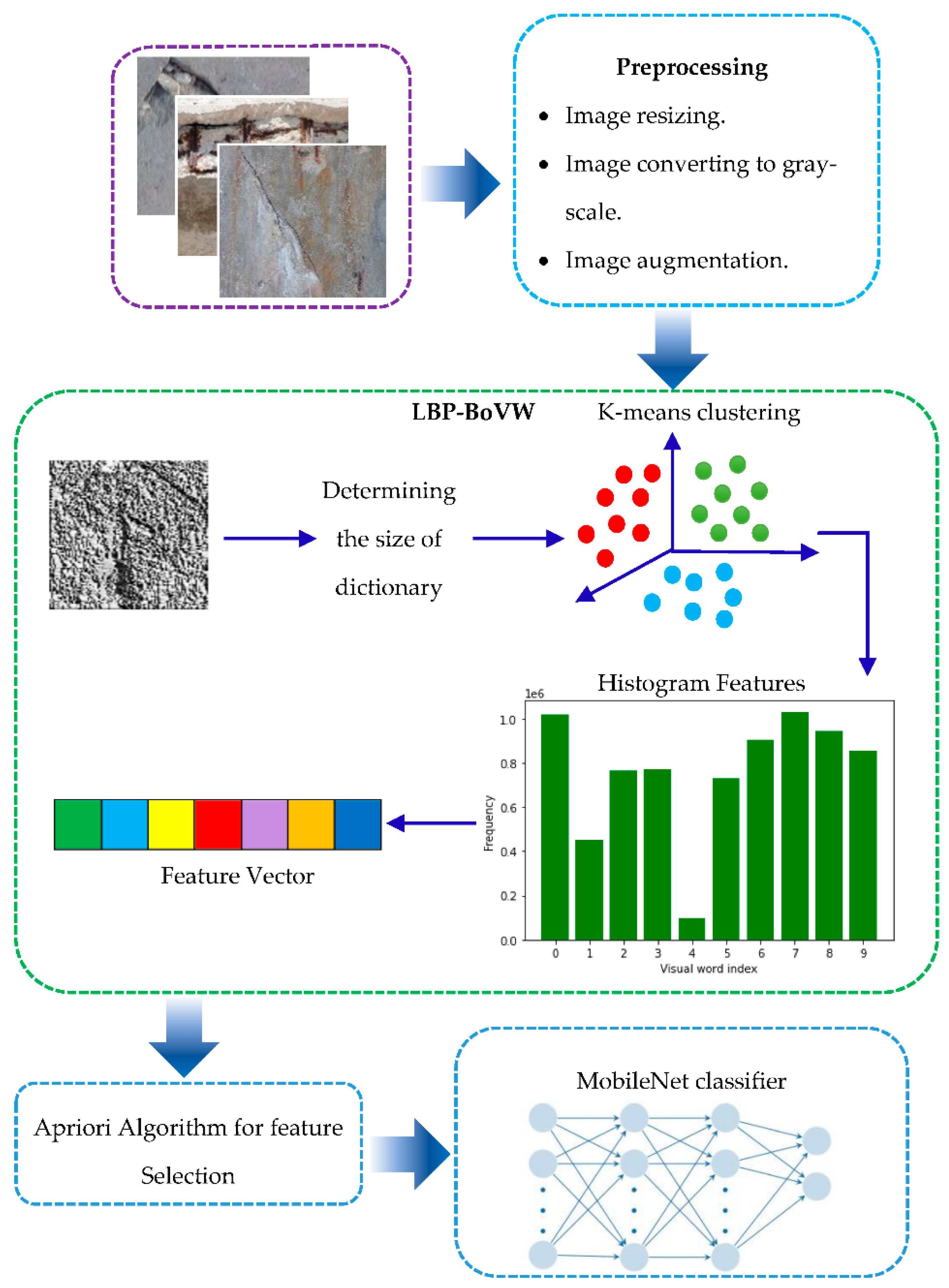

2.1. Preprocessing

- Image resizing works the model correctly; images must be resized to a consistent size. The large image is difficult to process effectively. Therefore, we resized the different sizes of the used datasets to 100 x 100.

- Grayscale image: a grayscale instead of color is used in this work to simplify the image's data and lower the processing requirements of algorithms.

- Data augmentation techniques are used to produce new images from existing ones to increase the size of a dataset. It enhances the model's generalization and decreases overfitting.

- The data normalization technique sets pixel intensity values to a predefined range, usually between 0 and 1.

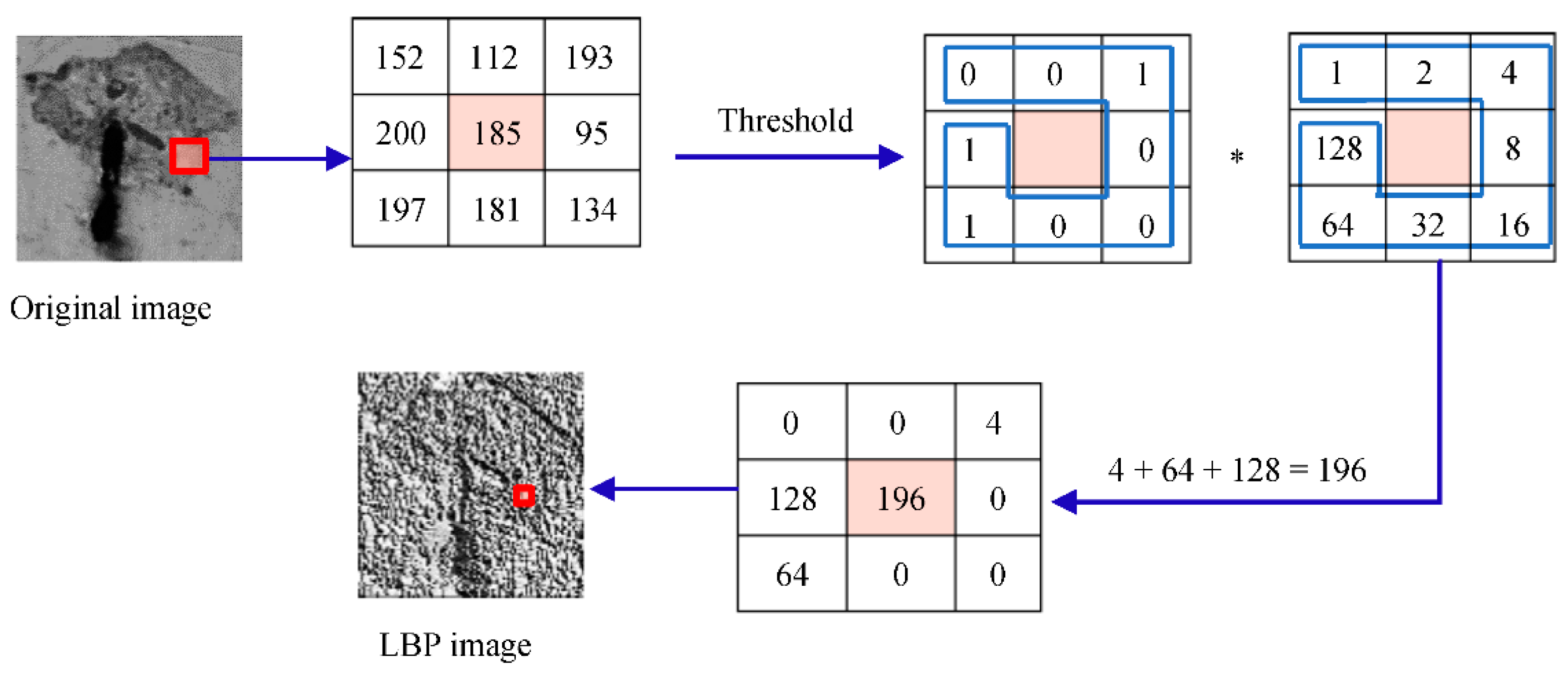

2.2. Local Binary Pattern

2.3. LBP-BoVW

- Determine the number of patches needed to divide each image into patches. Here we used 250 image patches.

- Computed the LBP for each patch.

- To determine the size of the dictionary (k), we used 50, 100, 200, and 300, which represent the number of K-means clusters.

- Identify each cluster's center. These centers are the visual words. The size of the visual word vector is equal to K.

- Computed the histograms for each image to create the local feature vectors.

2.4. Feature Selection and Dimensionality Reduction

- We can reduce overfitting by eliminating redundant or unnecessary features from the model, especially when working with high-dimensional data.

- Dimensionality and feature reduction can produce a simpler, more interpretable model that is easier to comprehend and explain.

- Reducing execution time by shrinking the model's size, data pruning assists in speeding up the training and inference processes.

- By eliminating noisy or unnecessary features, the ability of a model to generalize to previously unobserved data can be enhanced.

- By data pruning, the best trade-off between model size and performance is achieved, resulting in a balance between accuracy and complexity.

- Feature reduction helps to enhance model performance and lower the chance of overfitting.

2.5. MobileNet

3. Experimental Results

3.1. Experimental Environment

3.2. Datasets

- DIMEC-Crack Database: Lopez Droguett et al. [28] developed a new dataset for crack semantic segmentation. The dataset contains images extracted from video captured by the Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) equipped with high-resolution cameras for several concrete bridges. Each image has a resolution of 1920 x 1080; in their study, they extracted non-overlapping patches of 96 x 96 pixels from each raw image, but we will use the original raw images. The dataset contains 10,092 high-resolution images separated into two classes: 7872 crack and 2220 non-crack images.

- CODEBRIM Dataset: Mundt et al. [29] introduced a novel concrete defect bridge image (CODEBRIM) dataset. CODEBRIM includes images of 30 distinct bridges, excluding bridges without defects. The bridges were selected based on their levels of general degradation, severity, number of defects, and surface appearance, such as roughness and color. Images were captured in different weather conditions to encompass damp or soiled surfaces using numerous cameras at various magnifications. Due to the small size of the defects, high-resolution images were required. An UAV obtained a portion of the dataset due to the inaccessibility of certain bridge areas. Four distinct cameras with high resolution and huge focal lengths collected the dataset, capturing images from various distances and perspectives. Furthermore, to uniformly brighten the darkest sections of the bridge, they employed diffused flash. The additional material contains precise information about the specific camera models and their accompanying technical specifications. The collection comprises 7455 high-resolution photos of 30 distinct bridges obtained at various sizes and resolutions. We divided it into two classes: defects and background. The defects have 4388 images, while the background contains 3067 images.

- Bridge Concrete Damage (BCD): Xu et al. [19] introduced dataset, which includes 2068 images of bridge cracks and non-cracks. They captured the images using the Phantom 4 Pro's CMOS surface array camera, boasting a resolution of 1024x1024. The images underwent two reductions, first to dimensions of 512×512 and then to a size of 224×224 to produce the dataset. This dataset consists of 4057 photos with cracks and 2013 images without cracks.

- Bridge Datasets: The dataset created by Zoubir et al. [17] yielded a total of 1304 cracked and 1806 non-cracked RGB bridge images at a resolution of 200 × 200. These images depict various concrete surfaces and cracks from the actual bridge examination. In order to minimize crack-like noise, the images were pre-processed using a 3 x 3 median filter after being converted to grayscale

3.3. Evolution Metrics

3.4. Cross-Validation

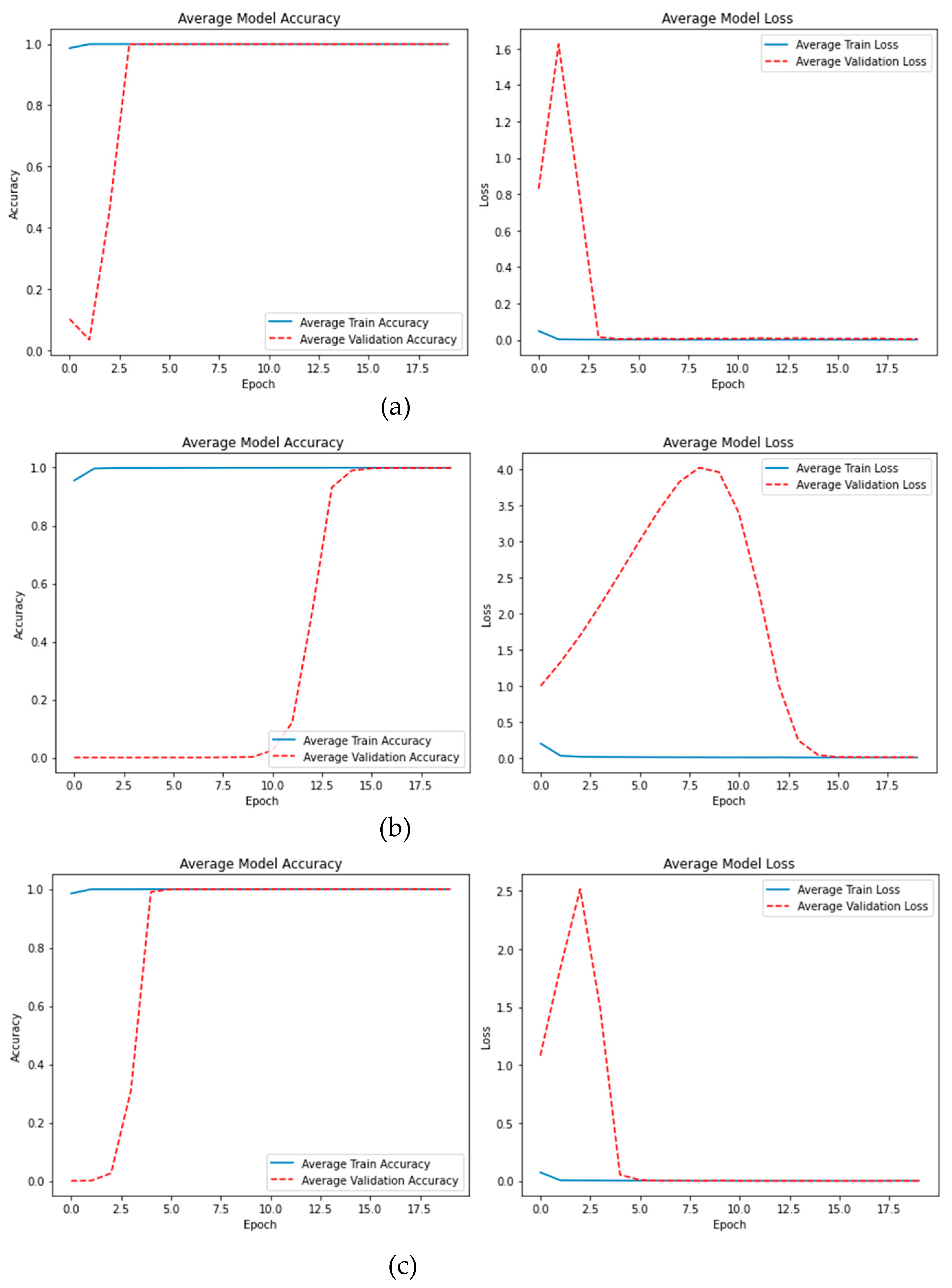

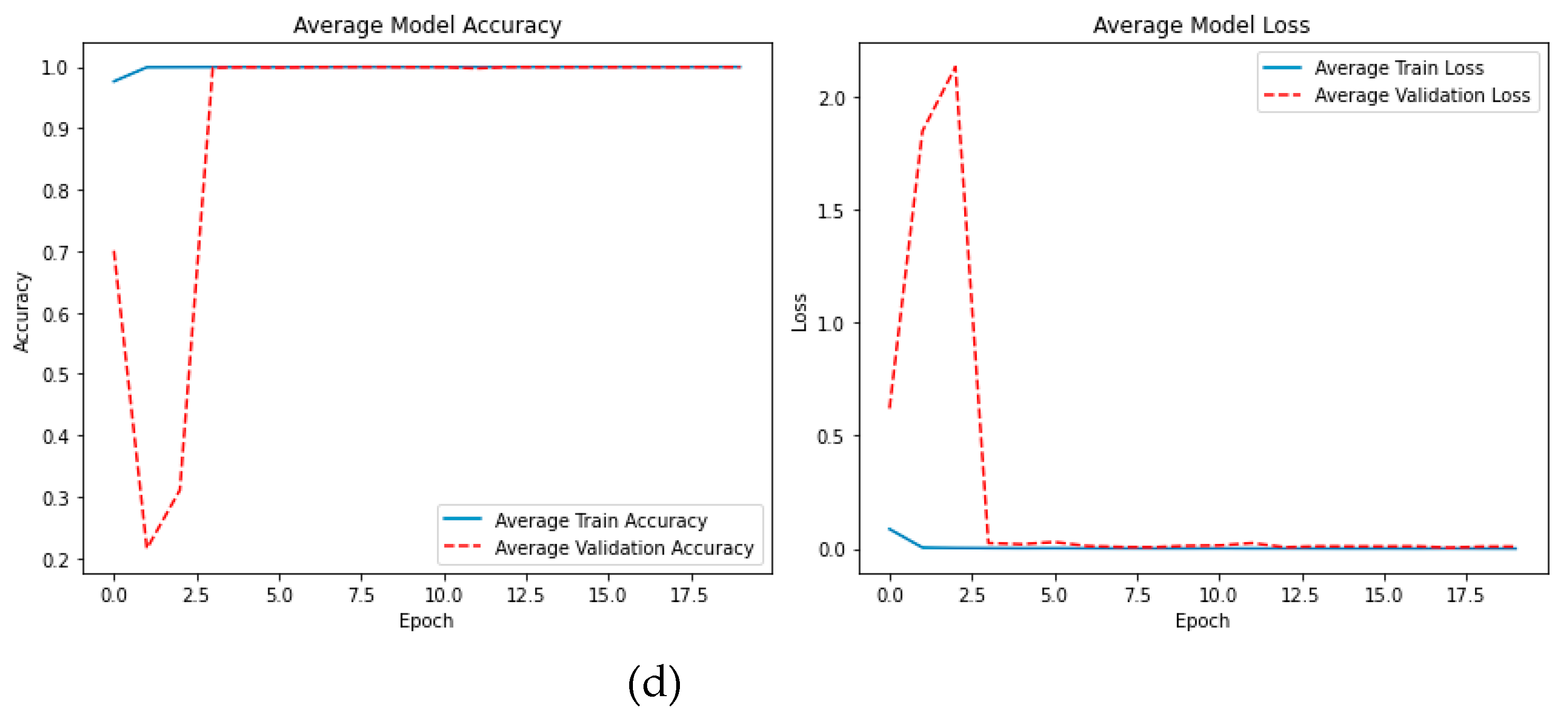

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nasr, A.; Kjellström, E.; Björnsson, I.; Honfi, D.; Ivanov, O. L., &Johansson, J. Bridges in a changing climate: a study of the potential impacts of climate change on bridges and their possible adaptations. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 2020, 16, pp. 738-749. [CrossRef]

- Ni, Y.; Mao, J.; Fu, Y.; Wang, H.; Zong, H., &Luo, K. Damage Detection and Localization of Bridge Deck Pavement Based on Deep Learning. sensors 2023, 23, p. 5138. [CrossRef]

- Bi, Q.; Goodman, K. E.; Kaminsky, J., &Lessler, J. What is Machine Learning? A Primer for the Epidemiologist. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 188, pp. 2222-2239. [CrossRef]

- Krahe, C.; Kalaidov, M.; Doellken, M.; Gwosch, T.; Kuhnle, A.; Lanza, G., &Matthiesen, S. AI-Based knowledge extraction for automatic design proposals using design-related patterns. Procedia CIRP 2021, 100, pp. 397-402.

- Cao, J.; Huang, Z., &Shen, H. T. Local deep descriptors in bag-of-words for image retrieval. . ACM Multimedia 2017, pp. 52-58. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, R. Q.; Sultani, Z. N., &Dhannoon, B. N. Content-Based Image Retrieval System using Color Moment and Bag of Visual Words with Local Binary Pattern. KIJOMS 2023, 9. [CrossRef]

- Ngoc, V. T. N.; Agwu, A. C.; Son, L. H.; Tuan, T. M.; Nguyen Giap, C.; Thanh, M. T. G.; Duy, H. B., &Ngan, T. T. The combination of adaptive convolutional neural network and bag of visual words in automatic diagnosis of third molar complications on dental x-ray images. Diagnostics 2020, 10, p. 209. [CrossRef]

- Afonso, L. C.; Pereira, C. R.; Weber, S. A.; Hook, C.; Falcão, A. X., && Papa, J. P. Hierarchical learning using deep optimum-path forest. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 2020, 71. [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, S.; Singh, S. K., &Kuan, L. H. Bag of Visual Words (BoVW) with Deep Features--Patch Classification Model for Limited Dataset of Breast Tumours. arXiv preprint arXiv:.10701 2022. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M. D.; Babaie, M.; Zhu, S.; Kalra, S., &Tizhoosh, H. R. A comparative study of CNN, BoVW and LBP for classification of histopathological images. SSCI 2017. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H., & Xu, K. Combing Triple-Part Features of Convolutional Neural Networks for Scene Classification in Remote Sensing. Remote Sens. 2019, 11. [CrossRef]

- Olaode, A., & Naghdy, G. Local Image Feature Extraction using Stacked-Autoencoder in the Bag-of-Visual Word modelling of Images. ICCC 2019, December, pp. 1744-1749. [CrossRef]

- Govender, D., & Tapamo, J.-R. Spatio-temporal scale coded bag-of-words. Sensors 2020, 20, p. 6380. [CrossRef]

- Sultani, Z. N., & Dhannoon, B. Modified Bag of Visual Words Model for Image Classification. ANJS 2021, 24, pp. 78-86. [CrossRef]

- Bhalaji Kharthik, K. S.; Onyema, E. M.; Mallik, S.; Siva Prasad, B. V. V.; Qin, H.; Selvi, C., &Sikha, O. K. Transfer learned deep feature based crack detection using support vector machine: a comparative study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, p. 14517. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Shi, W.; Chen, J., &Lin, W. Deep convolution neural network-based transfer learning method for civil infrastructure crack detection. Autom Constr 2020, 116, p. 103199. [CrossRef]

- Zoubir, H.; Rguig, M.; El Aroussi, M.; Chehri, A., &Saadane, R. Concrete Bridge Crack Image Classification Using Histograms of Oriented Gradients, Uniform Local Binary Patterns, and Kernel Principal Component Analysis. Electronics (Basel) 2022, 11, p. 3357. [CrossRef]

- Zoubir, H.; Rguig, M., &Elaroussi, M. Crack recognition automation in concrete bridges using Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. MATEC Web of Conferences 2021, 349, p. 03014.

- Xu, H.; Su, X.; Wang, Y.; Cai, H.; Cui, K., &Chen, X. Automatic Bridge Crack Detection Using a Convolutional Neural Network. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, p. 2867. [CrossRef]

- Ojala, T.; Pietikainen, M., &Maenpaa, T. Multiresolution gray-scale and rotation invariant texture classification with local binary patterns. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2002, 24, pp. 971-987. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Cai, R.; Cui, Y.; Liu, X.; Hu, Y., &Kot, A. C. Rethinking vision transformer and masked autoencoder in multimodal face anti-spoofing. Int J Comput Vis 2024, 132, pp. 1-22. [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, R.; Imielinski, T., &Swami, A. Database mining: A performance perspective. TKDE 1993, 5, pp. 914-925. [CrossRef]

- Zakur, Y., & Flaih, L. Apriori Algorithm and Hybrid Apriori Algorithm in the Data Mining: A Comprehensive Review. E3S Web of Conferences 2023, 448, p. 02021. [CrossRef]

- Kharsa, R., & Aghbari, Z. A. Association rules based feature extraction for deep learning classification. icSoftComp2022 2022, December, pp. 72-83. [CrossRef]

- Mamdouh Farghaly, H., & Abd El-Hafeez, T. A high-quality feature selection method based on frequent and correlated items for text classification. Soft Comput. 2023, 27, pp. 11259-11274. [CrossRef]

- Howard, A. G.; Zhu, M.; Chen, B.; Kalenichenko, D.; Wang, W.; Weyand, T.; Andreetto, M., &Adam, H. Mobilenets: Efficient convolutional neural networks for mobile vision applications. arXiv preprint arXiv:.04861 2017. [CrossRef]

- Howard, A.; Sandler, M.; Chu, G.; Chen, L. C.; Chen, B.; Tan, M., &Adam, H. Searching for mobilenetv3. IEEE/CVF 2019. [CrossRef]

- Lopez Droguett, E.; Tapia, J.; Yanez, C., &Boroschek, R. Semantic segmentation model for crack images from concrete bridges for mobile devices. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. O 2022, 236, pp. 570-583. [CrossRef]

- Mundt, M.; Majumder, S.; Murali, S.; Panetsos, P., &Ramesh, V. Meta-learning convolutional neural architectures for multi-target concrete defect classification with the concrete defect bridge image dataset. CVPR 2019. [CrossRef]

- Brzezinski, D., & Stefanowski, J. Prequential AUC: properties of the area under the ROC curve for data streams with concept drift. Knowl Inf Syst 2017, 52, pp. 531-562. [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.-G., & Dong, W.-M. A study on cost behaviors of binary classification measures in class-imbalanced problems. arXiv preprint arXiv:.04861 2014,. [CrossRef]

- Tran, T. X., "The high confidence data classification method with near zero classification error," The University of Alabama in Huntsville, 2021.

- DeLong, E. R.; DeLong, D. M., &Clarke-Pearson, D. L. Comparing the Areas under Two or More Correlated Receiver Operating Characteristic Curves: A Nonparametric Approach. Biometrics 1988, 44, pp. 837-845. [CrossRef]

| Datasets | No. LBP-BoVW feature | ||||

| 50 | 100 | 200 | 300 | ||

| No. features after Apriori feature selection | DIMEC-Crack Database | 21 | 19 | 18 | 17 |

| CODEBRIM | 21 | 20 | 22 | 20 | |

| BCD | 21 | 17 | 14 | 14 | |

| Bridge | 20 | 19 | 18 | 18 | |

| Datasets | Performance Metrics | Number of visual words | |||

| 50 | 100 | 200 | 300 | ||

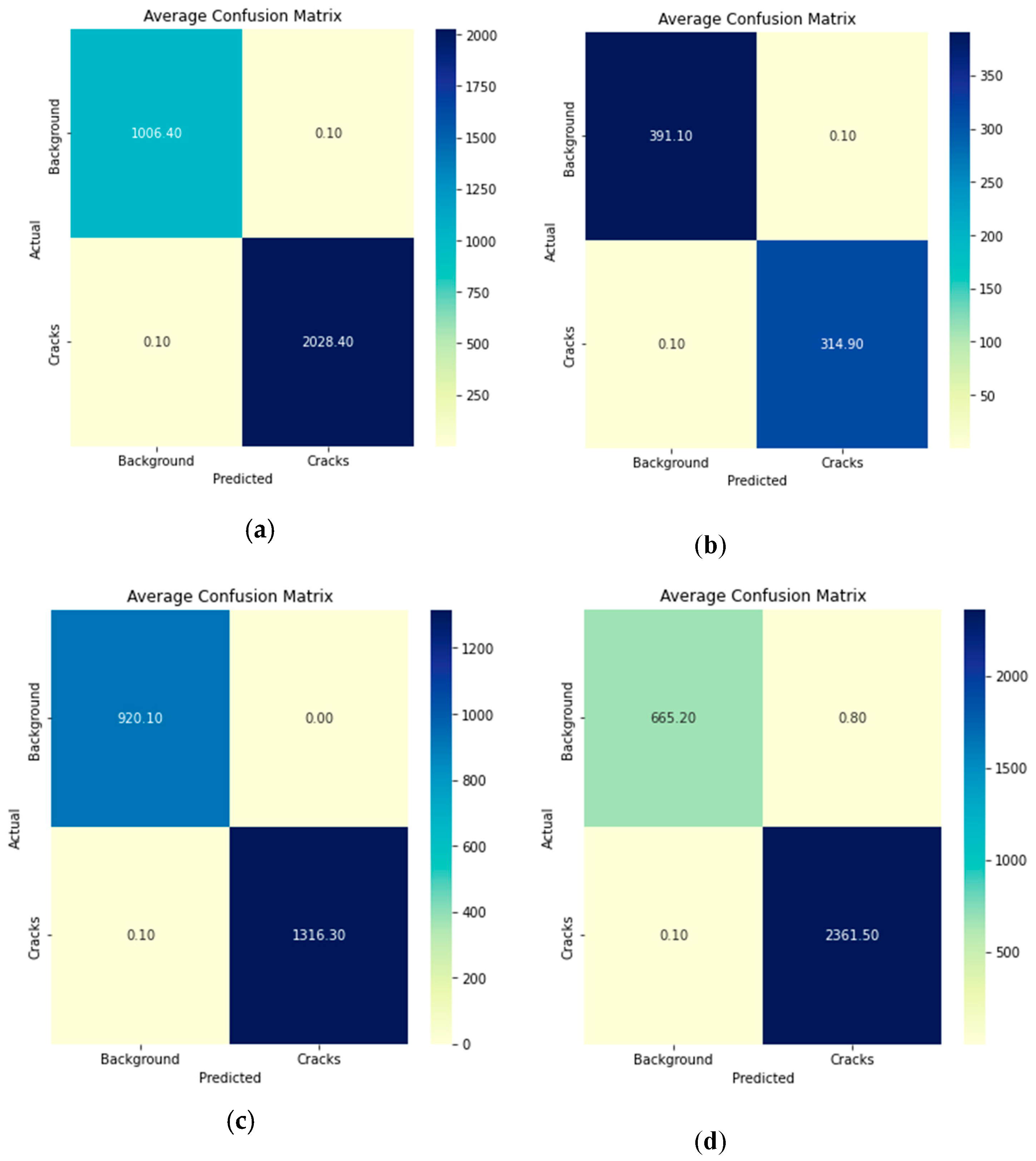

| BCD | Accuracy | 99.98 | 99.99 | 99.98 | 99.97 |

| Precision | 99.97 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| Recall | 100 | 99.99 | 99.97 | 99.97 | |

| F1-score | 99.99 | 100 | 99.98 | 99.98 | |

| ROC-AUC | 99.97 | 99.99 | 99.98 | 99.98 | |

| Error rate | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | |

| Bridge Dataset | Accuracy | 99.82 | 99.84 | 99.96 | 99.97 |

| Precision | 99.78 | 99.90 | 99.97 | 99.97 | |

| Recall | 99.81 | 99.75 | 99.94 | 99.97 | |

| F1-score | 99.79 | 99.83 | 99.95 | 99.97 | |

| ROC-AUC | 99.82 | 99.83 | 99.96 | 99.97 | |

| Error rate | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.04 | 0.03 | |

| CODEBRIM | Accuracy | 99.93 | 99.94 | 100 | 98.27 |

| Precision | 99.96 | 99.92 | 100 | 99.97 | |

| Recall | 99.92 | 99.98 | 99.99 | 97.09 | |

| F1-score | 99.94 | 99.95 | 100 | 98.28 | |

| ROC-AUC | 99.93 | 99.93 | 100 | 98.52 | |

| Error rate | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0 | 1.73 | |

| DIMEC-Crack | Accuracy | 99.98 | 99.99 | 99.98 | 99.97 |

| Precision | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99.99 | |

| Recall | 99.97 | 99.99 | 99.98 | 99.97 | |

| F1-score | 99.99 | 99.99 | 99.99 | 99.98 | |

| ROC-AUC | 99.99 | 99.99 | 99.99 | 99.97 | |

| Error rate | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | |

| Refrences | Method | K-fold CV | No. of Epochs | Datasets | |||

| BCD | Bridge | CODEBRIM | DIMEC-Crack | ||||

| Bhalaji Kharthik et al. [15] | VGG16 | - | - | 99.83 | - | - | - |

| VGG19 | 99.67 | - | - | - | |||

| Xception | 99.67 | - | - | - | |||

| ResNet 50 | 99.67 | - | - | - | |||

| ResNet 101 | 99.5 | - | - | - | |||

| ResNet 152 | 99.83 | - | - | - | |||

| InceptionV3 | 99.83 | - | - | - | |||

| InceptionResNet V2 | 99.5 | - | - | - | |||

| MobileNet | 99.83 | - | - | - | |||

| MobileNetV2 | 99.83 | - | - | - | |||

| DenseNet121 | 99.67 | - | - | - | |||

| EfficientNetB0 | 99.83 | - | - | - | |||

| Yang et al. [16] | TL model | - | 20 | 99.72 | - | - | - |

| Zoubir et al. [18] | TL model | 5-fold | 10 | - | 95.89 | - | - |

| Zoubir et al. [17] | HOG + ULBP + KPCA+ SVM | 5-fold | - | - | 99.29 | - | - |

| Xu et al. [19] | atrous convolution, ASPP, and depthwise separable convolution | - | 300 | 96.37 | - | - | - |

| MobileNetV3_Large | 10-fold | 20 | 82.14 | 72.59 | 77.53 | 91.51 | |

| Proposed Method | LBP-BoVW+ Appriori+ MobileNetV3_Large | 10-fold | 20 | 99.99 | 99.97 | 100 | 100 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).