1. Introduction

Postharvest preservation of fruits represents a critical concern in the food industry due to the rapid deterioration that occurs after harvest, leading to significant losses in quality, quantity, and economic value [

1,

2]. Among the most vulnerable tropical fruits is the banana (

Musa paradisiaca), which is highly perishable and prone to changes in texture, color, and nutritional composition during storage [

2,

3]. This situation is particularly relevant in producing countries such as Ecuador, where postharvest losses can reach up to 30%, posing a significant economic, social, and logistical challenge [

4,

5].

The economic impact of these losses affects not only large exporters but also small-scale producers, who rely on the sale of fresh fruit as their primary source of income. The reduced commercial shelf life of the fruit limits its distribution to international markets and increases food waste, which negatively impacts food security and the sustainability of the agri-food system [

5,

6]. For this reason, the development of accessible, sustainable, and effective technologies to prolong banana preservation is a priority research area.

Edible coatings applied to the surface of fruits are considered a promising strategy to extend the shelf life of fruits and vegetables by reducing water loss, controlling respiration, and delaying ripening [

7]. These coatings can be composed of natural and biodegradable ingredients, providing a protective barrier without compromising food safety or nutritional quality [

8]. The composition of the coating is a factor in determining its effectiveness, as each ingredient directly influences the preservation of the fruit’s physicochemical properties [

9,

10].

Several studies have explored different ingredient combinations to develop effective coatings for banana preservation. For instance, previous research has shown that using whey as a principal component in edible coatings enhances moisture retention and provides antimicrobial properties, contributing to extended shelf life [

11]. Similarly, natural polysaccharides such as agar and starch offer notable benefits in the formation of protective films by reducing oxidation and improving the mechanical resistance of the coating, helping preserve the physical appearance of the banana [

12,

13].

Glycerol, widely recognized for its humectant and plasticizing properties, has been identified as a component in edible coating formulations due to its ability to improve film flexibility and prevent cracking or breakage during storage and transport [

14]. When combined with biopolymers such as whey, its effect is enhanced, significantly reducing fruit dehydration and helping preserve firmness—both essential for maintaining postharvest banana quality [

15,

16].

Additionally, in polysaccharide-based systems, glycerol has been shown to reduce mechanical damage and improve the structural stability of fruits under handling and transport conditions [

17,

18]. Several studies agree that the combination of natural ingredients, such as proteins, polysaccharides, and plasticizers, not only preserves the fruit’s organoleptic properties but also enhances its resistance to adverse environmental conditions, supporting prolonged storage [

19,

20].

These formulations have been successfully applied to fruits such as mango, papaya, and grapes, showing significant improvements in firmness, color retention, acid content, and resistance to physical damage [

15,

16,

17]. However, in the specific case of bananas, there remains a need to develop coatings tailored to their physiological characteristics, such as high respiration rates and ethylene sensitivity. Moreover, validating these technologies under refrigerated storage conditions is essential, as these are commonly used in the export supply chain.

A comprehensive evaluation of coatings considering not only their physical properties but also their structural and chemical effects is necessary to understand their influence on parameters such as weight loss, firmness, fruit dimensions, peel color, pH, titratable acidity, and soluble solids content (°Brix). These indicators determine the ripening stage, storage stability, and overall fruit quality, which are essential for assessing the commercial viability of the applied coatings [

21].

This study focuses not only on the formulation of an edible coating but also on a series of physicochemical analyses aimed at evaluating the effectiveness of the developed coatings for future applications. Such detailed characterization is essential for generating solid scientific evidence supporting the use of natural coatings as a postharvest strategy. The evaluated parameters include:

Weight loss percentage, which is fundamental for assessing the coating’s efficiency in moisture retention and dehydration prevention. This parameter directly correlates with water evaporation, and its control helps extend the fruit’s shelf life [

22].

Changes in fruit dimensions (length and peel thickness), which indicate the coating’s effectiveness in preserving structural integrity. Significant changes may reflect accelerated ripening or mechanical damage. Monitoring these parameters helps assess whether the coatings effectively maintain the banana’s physical structure during storage [

23].

Firmness, measured with a penetrometer, evaluates the fruit’s resistance to deformation. An effective coating should help preserve peel firmness, preventing softening and mechanical injury [

24]. Firmness is also linked to consumer perception and visual fruit quality.

Color changes, particularly in peel luminosity and chromaticity (a*, b*), serve as visual indicators of ripening and oxidation. Coatings that slow these changes contribute to improved visual quality and consumer acceptance [

25].

Chemical parameters such as pH, titratable acidity, and soluble solids content provide insight into the fruit’s internal metabolic state. A suitable coating should help delay acidity loss and the increase in soluble sugars, both associated with overripening [

26]. These measurements are fundamental for monitoring the ripening process and determining the coating’s influence on internal fruit chemistry during storage [

16,

27].

This study provides valuable insights into the potential of coatings formulated with whey, agar, starch, and glycerol as a viable solution to extend the postharvest shelf life of bananas. The findings may contribute to the development of new preservation techniques applicable in both the food industry and small-scale agricultural systems, helping reduce food waste and improve food security [

23,

28].

2. Materials and Methods

Banana samples (Musa paradisiaca) were collected in the city of Machala, El Oro province, Ecuador, at an early commercial ripeness stage (ripening stage 1), with uniform size and free from visible defects. The fruits were then transported to the laboratory of the National Polytechnic School, where they were kept under controlled conditions of temperature (13 ± 1 °C) and relative humidity (approximately 95%). All experimental treatments were conducted under these storage conditions.

2.1. Coating Design

Various coating formulations were developed for the preservation of bananas, using whey, agar, starch, and glycerol as base ingredients. To evaluate their impact on the physicochemical properties of the fruit, different combinations of these components were prepared. The compositions of the treatments (T1, T2, T3, T4, T5, T6, and T7) are detailed in

Table 1, where each treatment corresponds to a specific mixture of ingredients (in grams) dissolved in 1 liter of distilled water.

The mixture was homogenized using a magnetic stirrer at room temperature (approximately 25 °C), ensuring complete dissolution of the solids in a uniform solution. Previously selected Musa paradisiaca bananas were immersed in the prepared coating solution for each treatment. All treatments were performed in triplicate to ensure the reliability of the results. After immersion, the fruits were air-dried at room temperature for 12–15 minutes to allow the formation of a uniform coating layer.

The coated bananas were stored for a period of four weeks under continuous monitoring of temperature and relative humidity using a Testo 608-H2 thermo-hygrometer (accuracy ±2% RH and ±0.5 °C). Various physicochemical properties were evaluated, including weight loss, fruit length, peel thickness, color, and texture, to determine the impact of each treatment on fruit preservation. These properties were compared against a control treatment (T7), in which no coating was applied, to assess the effectiveness of the formulated coatings. Samples were taken weekly for analysis.

2.2. Physical Analysis

The physical parameters of the bananas were evaluated weekly using a total of 10 samples per treatment, following standardized methodologies.

2.2.1. Weight Variation

The weight of each banana was individually measured using a BPS 51 Plus precision balance (Boeco, Hamburg, Germany), with an accuracy of 0.01 g and a maximum capacity of 510 g. The initial weight of each fruit was recorded at the time of coating application. Subsequently, periodic measurements were taken throughout the storage period. Weight loss was calculated as the percentage reduction relative to the initial weight, using the following formula [

7]:

This measurement was used to assess the effectiveness of each treatment in water retention and dehydration control, which are critical for postharvest preservation.

2.2.2. Fruit Dimensions

The length and thickness of the banana samples were measured using a digital caliper with a precision of 0.01 mm. Fruit length was determined from the tip to the base, while thickness was measured at the widest point of the fruit, typically in the middle section [

29]. These measurements allowed the evaluation of size variation during storage and its correlation with the applied treatments.

2.2.3. Firmness

Measurements were conducted using a McCormick FT327 penetrometer (Forlì, Italy) equipped with an 8 mm diameter plunger. The instrument has a maximum capacity of 13 kgf and a sensitivity of 0.1 kgf. The evaluation focused on peel firmness, as resistance to deformation is a key indicator of structural integrity and the peel’s ability to protect the pulp during storage [

8,

29]. A constant force was applied to the fruit surface, allowing the probe to penetrate slightly into the pulp at a standardized depth. The force required for penetration was recorded, providing a reliable assessment of peel resistance and insights into fruit quality and ripeness progression over time.

2.2.4. Color

Peel color was determined using a Minolta CR-400 tristimulus colorimeter (Konica Minolta), which records L* (lightness), a* (red–green chromaticity), and b* (yellow–blue chromaticity) values [

10,

14]. Measurements were taken in triplicate at three different points on each banana, avoiding visible defects or blemishes to ensure accuracy. The average value was used to characterize surface color as a variable of ripeness, visual quality, and preservation status during storage.

2.3. Chemical Analysis

Chemical measurements were conducted in triplicate to monitor fruit ripening during storage, following internationally recognized standard procedures.

2.3.1. pH

Measurements were carried out using a Mettler Toledo SG2-FK digital pH meter (Schwerzenbach, Switzerland), which offers an accuracy of ±0.01 pH units. Prior to each reading, the instrument was calibrated using standard buffer solutions at pH 4.00 and 7.00 to ensure measurement accuracy. Juice was obtained from each fruit by manual or mechanical pressing, and the electrode was immersed directly into the juice to obtain digital readings. The procedure followed AOAC Method 981.12 for pH determination in food products [

30]. The data obtained was used to assess the degree of fruit ripeness and chemical stability during the storage period.

2.3.2. Titratable Acidity

Titration was conducted using 0.1 N NaOH, and the results were expressed as a percentage of citric acid, following AOAC Method 942.15. A Brand Titrette digital burette (accuracy ±0.01 mL) was used to ensure precise volume control during the procedure. Sodium hydroxide was gradually added to the banana juice until the endpoint was reached, as indicated by a color change due to phenolphthalein, confirming neutralization [

31]. All determinations were performed in triplicate to ensure measurement reliability. The average values were used to calculate the citric acid concentration in the juice.

2.3.3. Soluble Solids

Measurements were performed using an Atago PAL-1 digital refractometer (range: 0–53 °Brix; accuracy: ±0.2 °Brix), following AOAC Method 932.12. Results were expressed in degrees Brix (°Brix), representing the percentage of soluble solids in the sample [

32]. This parameter offered valuable insights into the concentration of sugars and other dissolved compounds in banana juice throughout the storage period.

3. Results

The following section presents the results obtained during the storage of Musa paradisiaca fruits treated with edible coatings, in comparison with an uncoated control group. Physicochemical parameters—including weight loss, firmness, peel color, pH, total soluble solids (°Brix), and titratable acidity—were evaluated to determine the effectiveness of the coatings in preserving postharvest quality.

3.1. Physical Analysis

3.1.1. Weight Variation

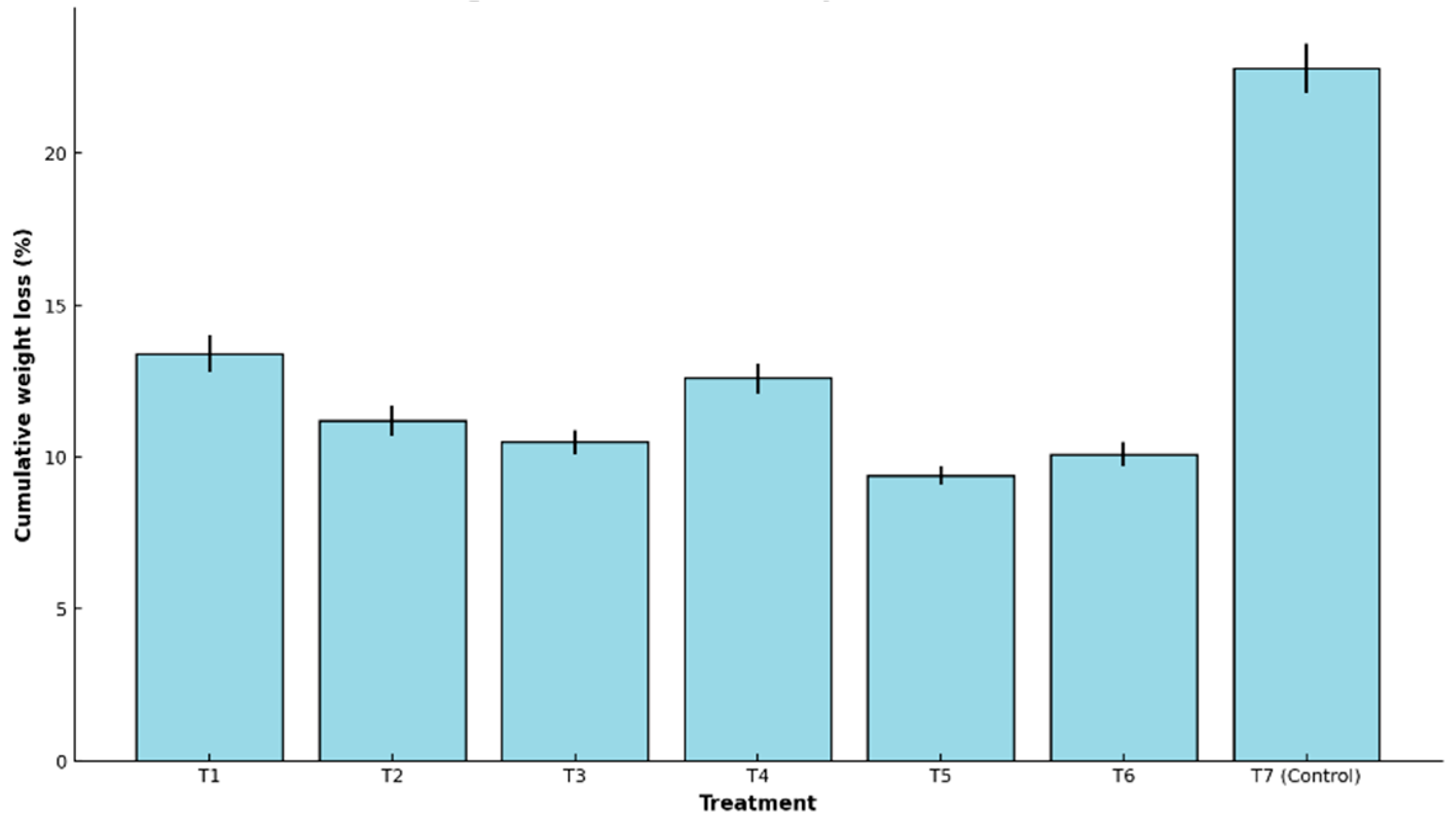

Weight loss is one of the most representative indicators of postharvest deterioration in fresh fruits, as it reflects water loss primarily due to transpiration and respiration. In the present study, the effectiveness of various edible coating formulations in reducing mass loss of Musa paradisiaca fruits was assessed under controlled storage conditions.

Figure 1 shows the final weight loss (%) values recorded for each treatment, revealing significant differences between the control group and the coated samples.

3.1.2. Fruit Dimensions

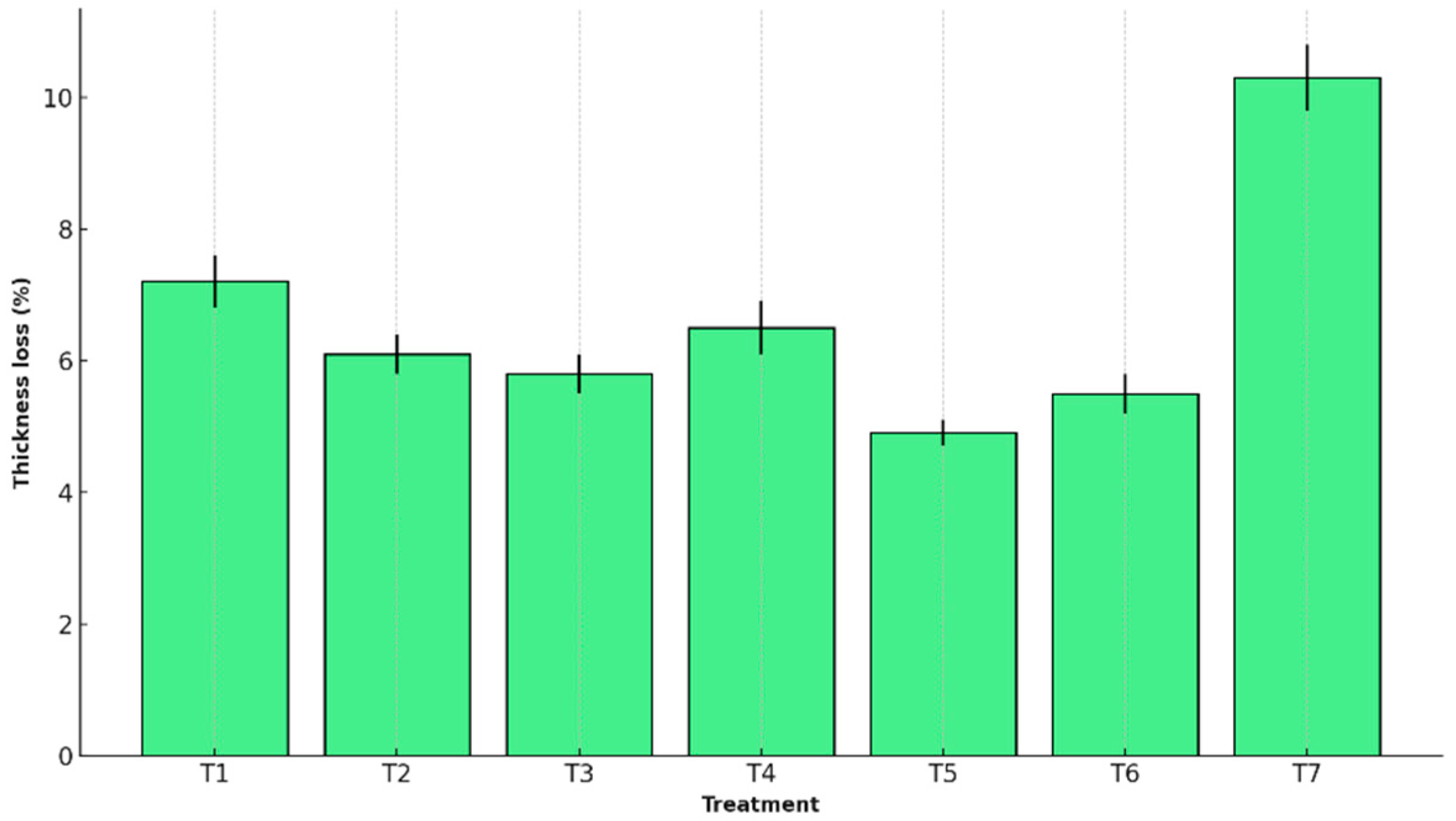

The banana peel serves as a protective barrier against moisture loss and mechanical damage. A reduction in peel thickness during storage can indicate progressive dehydration and structural deterioration. Peel thickness was measured using a digital caliper with a precision of ±0.01 mm. Measurements were taken at three equidistant points around the equatorial region of each fruit, and the average of the readings was recorded as the final value.

Figure 2 shows the peel thickness loss measured for each treatment.

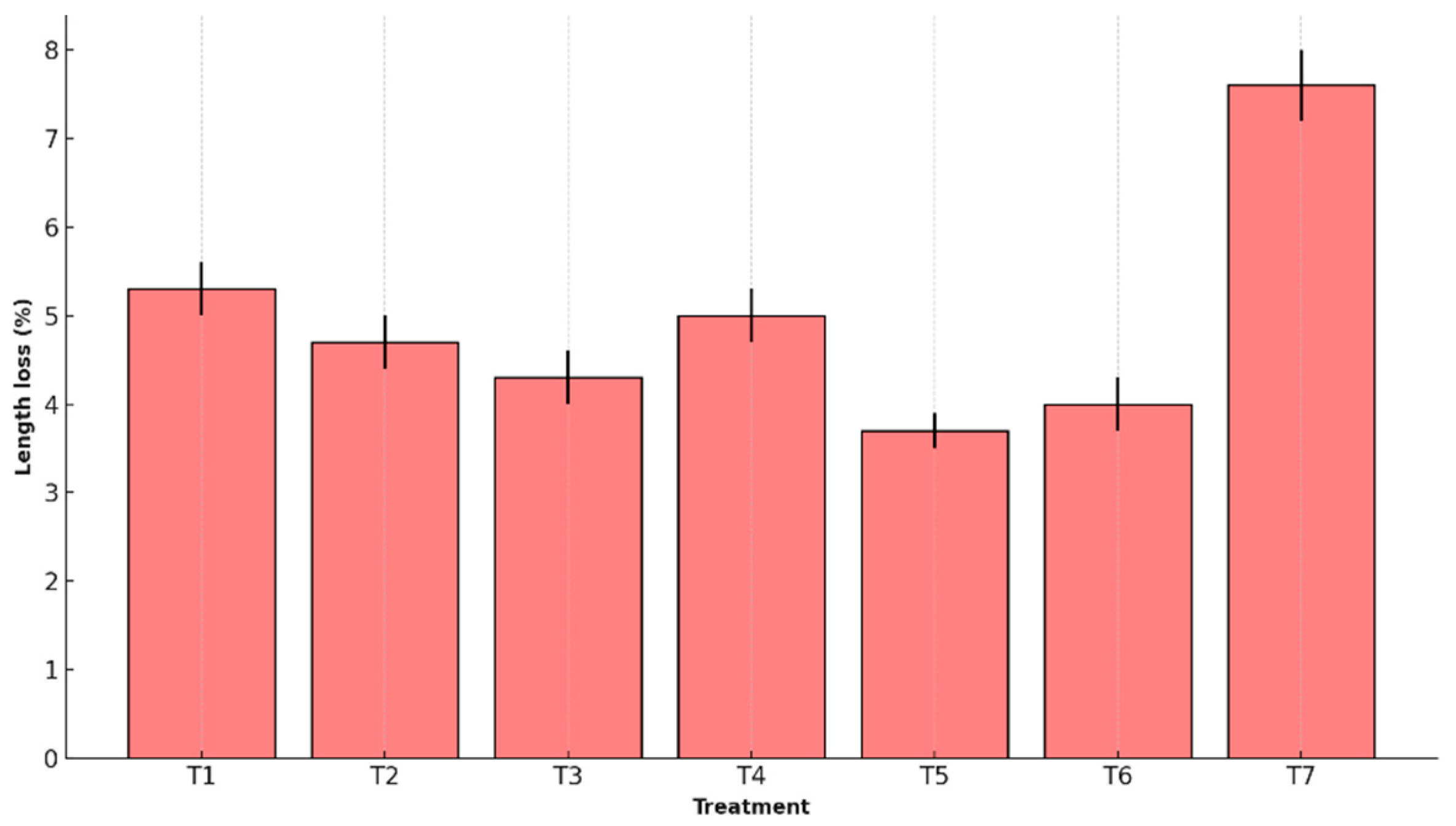

Fruit length is another physical parameter associated with the structural integrity of bananas. Its reduction may be related to loss of cell turgor and tissue contraction, which are common during advanced ripening or dehydration.

Figure 3 shows the percentage reduction in fruit length, comparing the effectiveness of different coatings in preserving this dimension.

3.1.3. Firmness

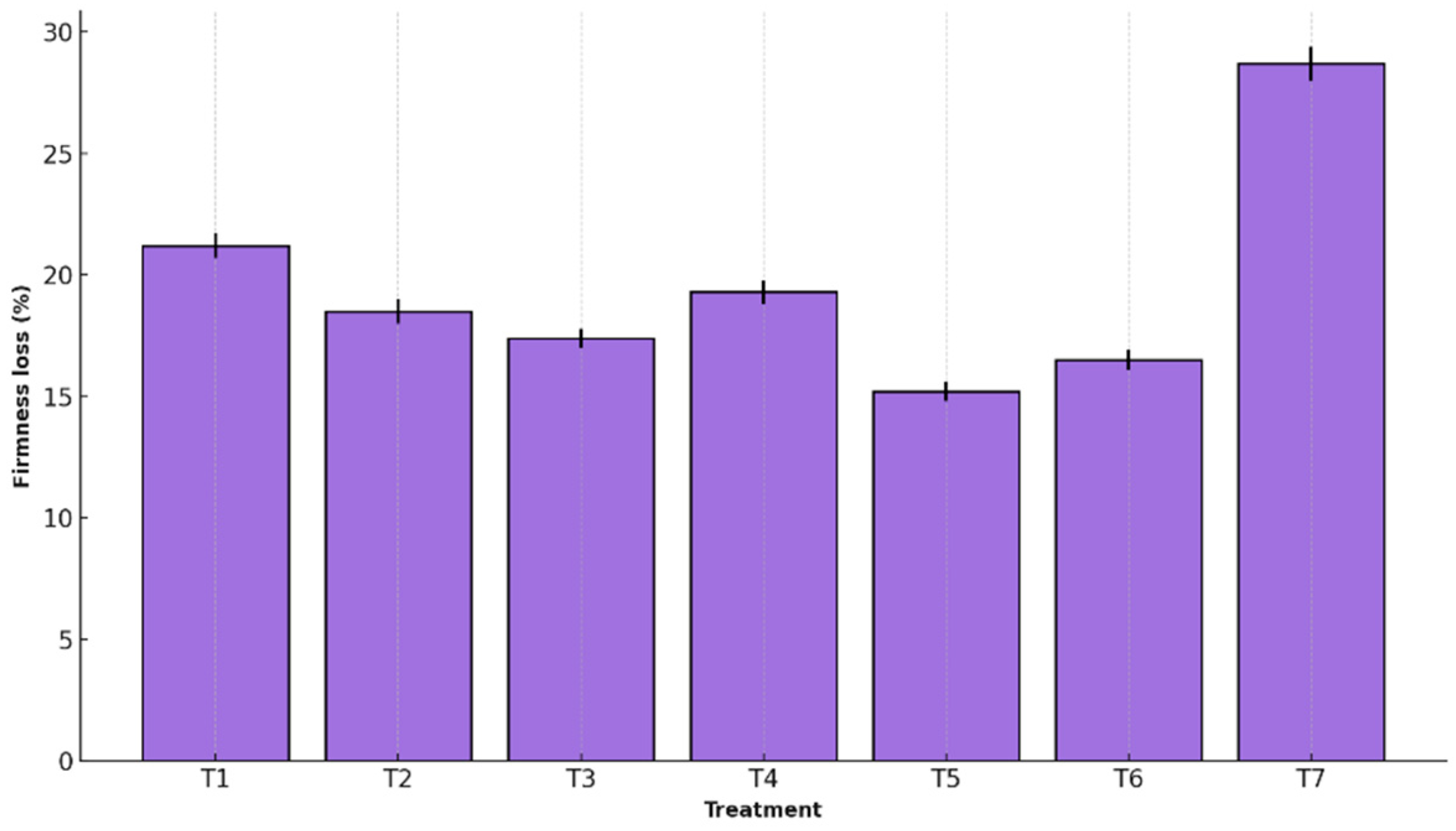

Figure 4 presents the percentage of firmness loss for each treatment, enabling a comparative evaluation of the effectiveness of edible coatings in preserving this structural parameter.

This physical attribute is critical for determining the postharvest quality of bananas, as it directly influences sensory acceptability and resistance to handling during transport and marketing. Loss of firmness is typically associated with cell wall degradation, a decline in turgor pressure, and the natural progression of ripening.

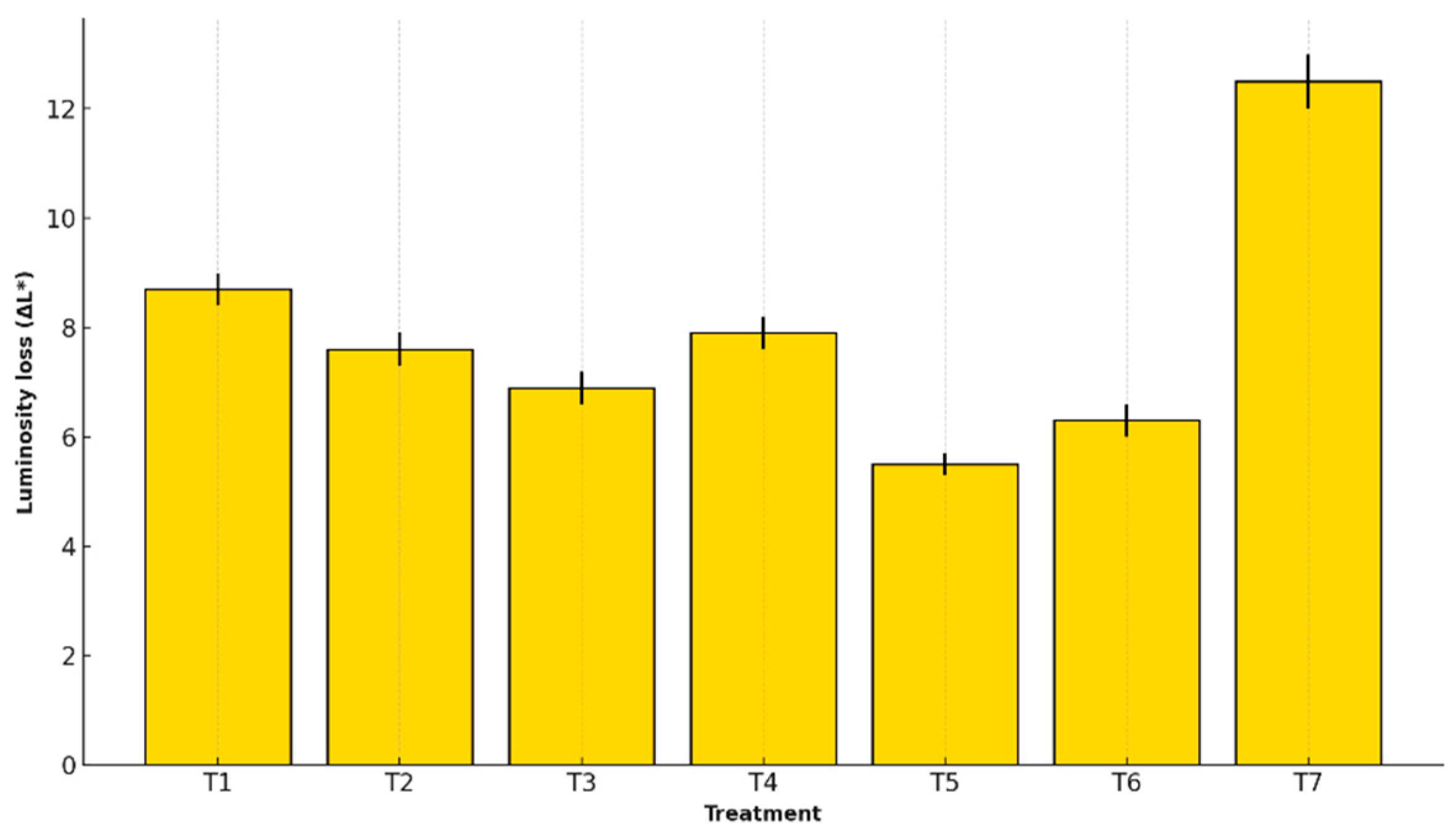

3.1.4. Color

The L value (luminosity) of the banana peel surface is closely related to its visual appearance and ripening stage. A decrease in luminosity (ΔL*) reflects enzymatic browning and pigment oxidation processes, both of which negatively impact the commercial quality of the fruit.

Figure 5 presents the L* loss values for each treatment, allowing for analysis of the effect of edible coatings on the preservation of the fruit’s external color.

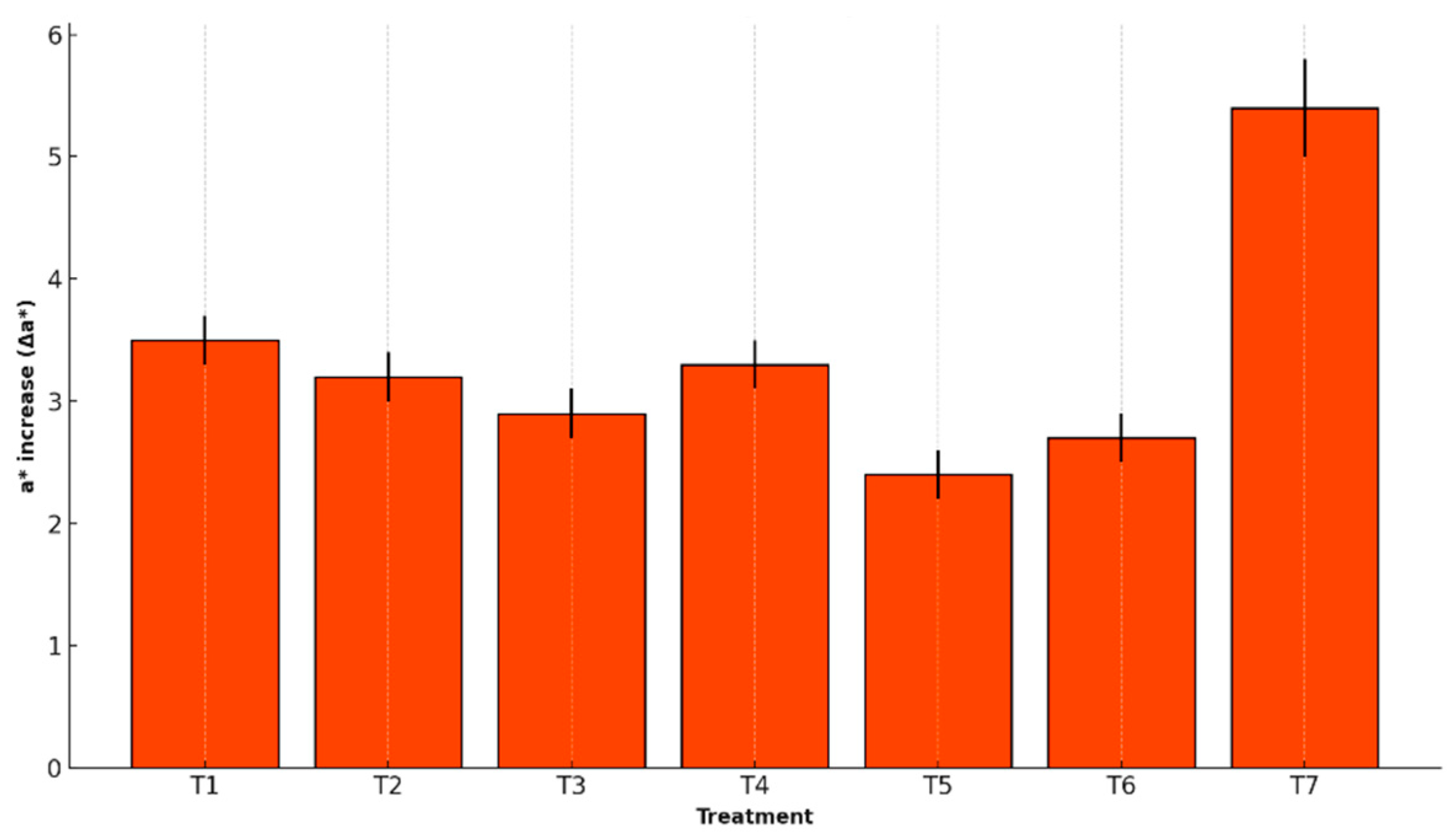

The a* chromaticity value represents the tendency of banana peel color toward red or brown hues. An increase in this parameter (Δa*) is associated with the progression of visual browning during ripening and the oxidation of phenolic compounds. It is particularly useful for detecting undesirable changes in the fruit’s appearance. The increase in a* was analyzed after refrigerated storage as a variable indicating the shift toward darker colors.

Figure 6 presents the Δa* values for each treatment, allowing for evaluation of the effective coatings in reducing or delaying visual deterioration in bananas.

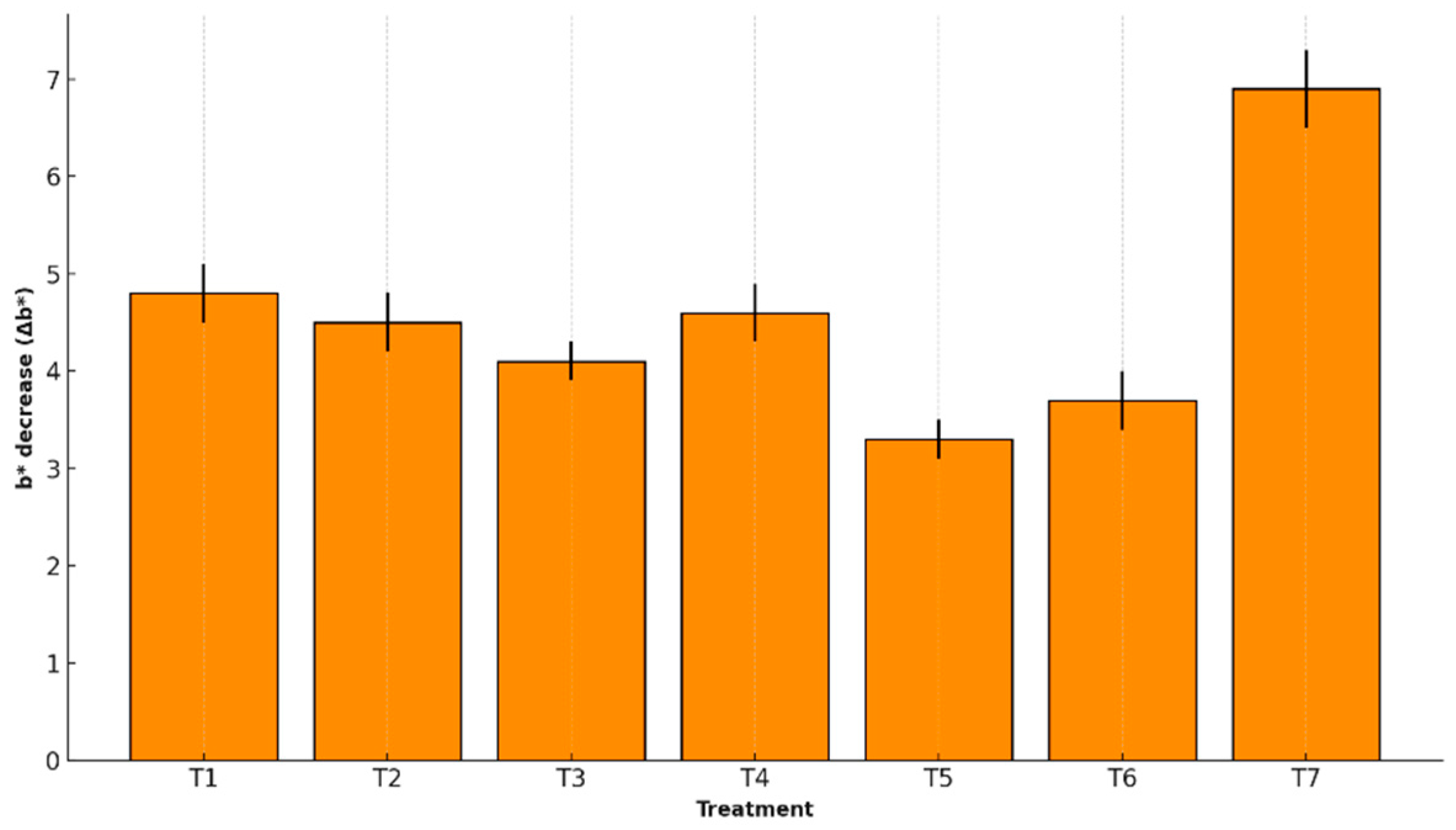

The b* chromaticity value is associated with the intensity of the characteristic yellow color of banana peel. A decrease in this parameter (Δb*) reflects a loss of warm pigmentation, typically linked to aging, senescence, and carotenoid oxidation. In this study, b* variation was measured after storage to evaluate the effect of edible coatings on preserving the fruit’s yellow coloration.

Figure 7 presents the Δb* values for each treatment.

3.2. Chemical Analysis

All chemical analyses were conducted in triplicate to monitor the progression of fruit ripening during storage, in accordance with internationally recognized standards.

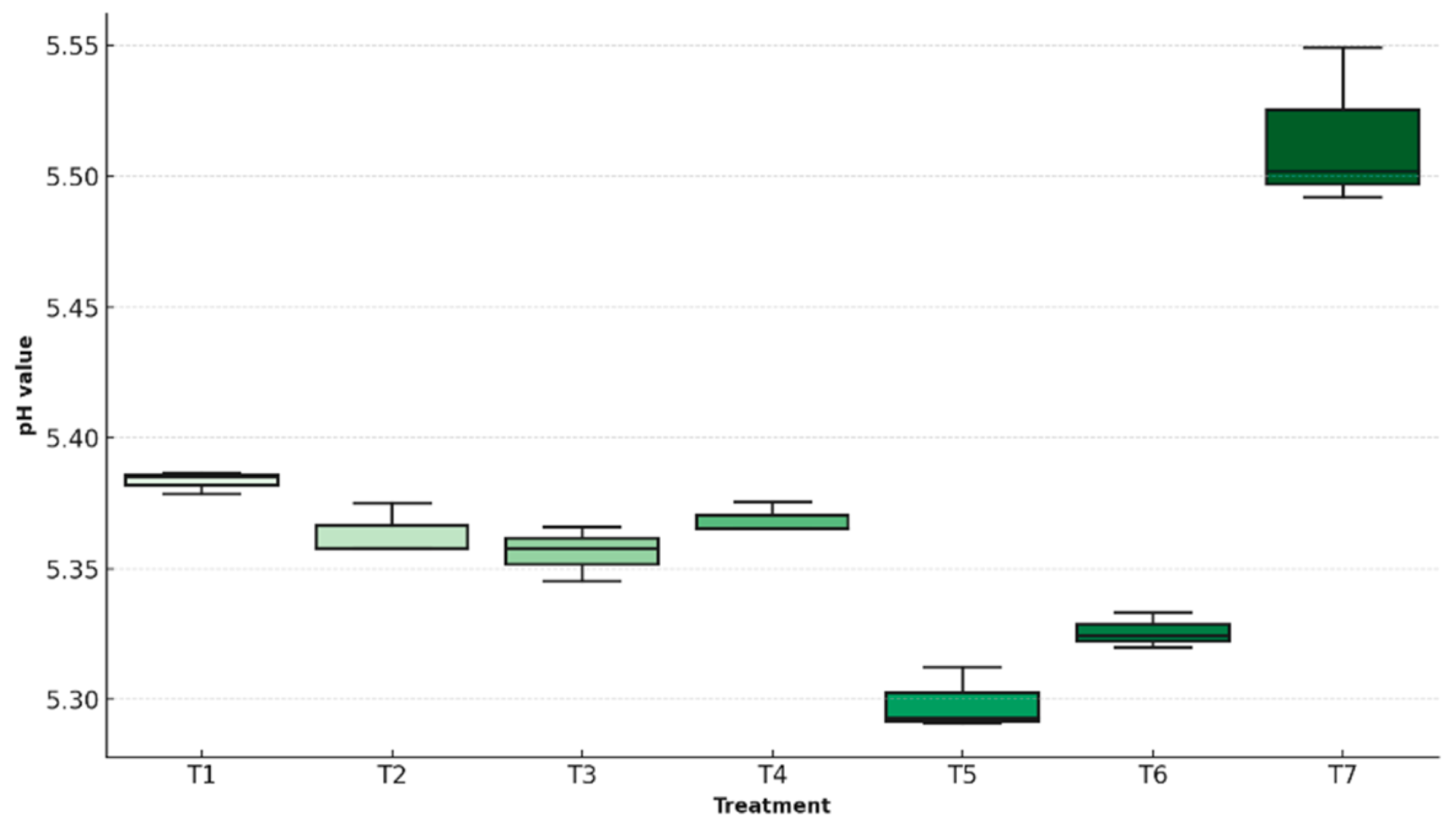

3.2.1. pH

This chemical parameter serves to assess the physiological status of fruit during storage, as increased values are typically associated with the breakdown of organic acids and the progression of ripening. More stable pH levels reflect reduced internal alteration and improved regulation of postharvest metabolic processes. In this study, the final pH of the fruits was measured.

Figure 8 presents a comparative boxplot of the treatments, illustrating data dispersion, central tendencies, and statistical differences in pH stability based on the coating formulation applied.

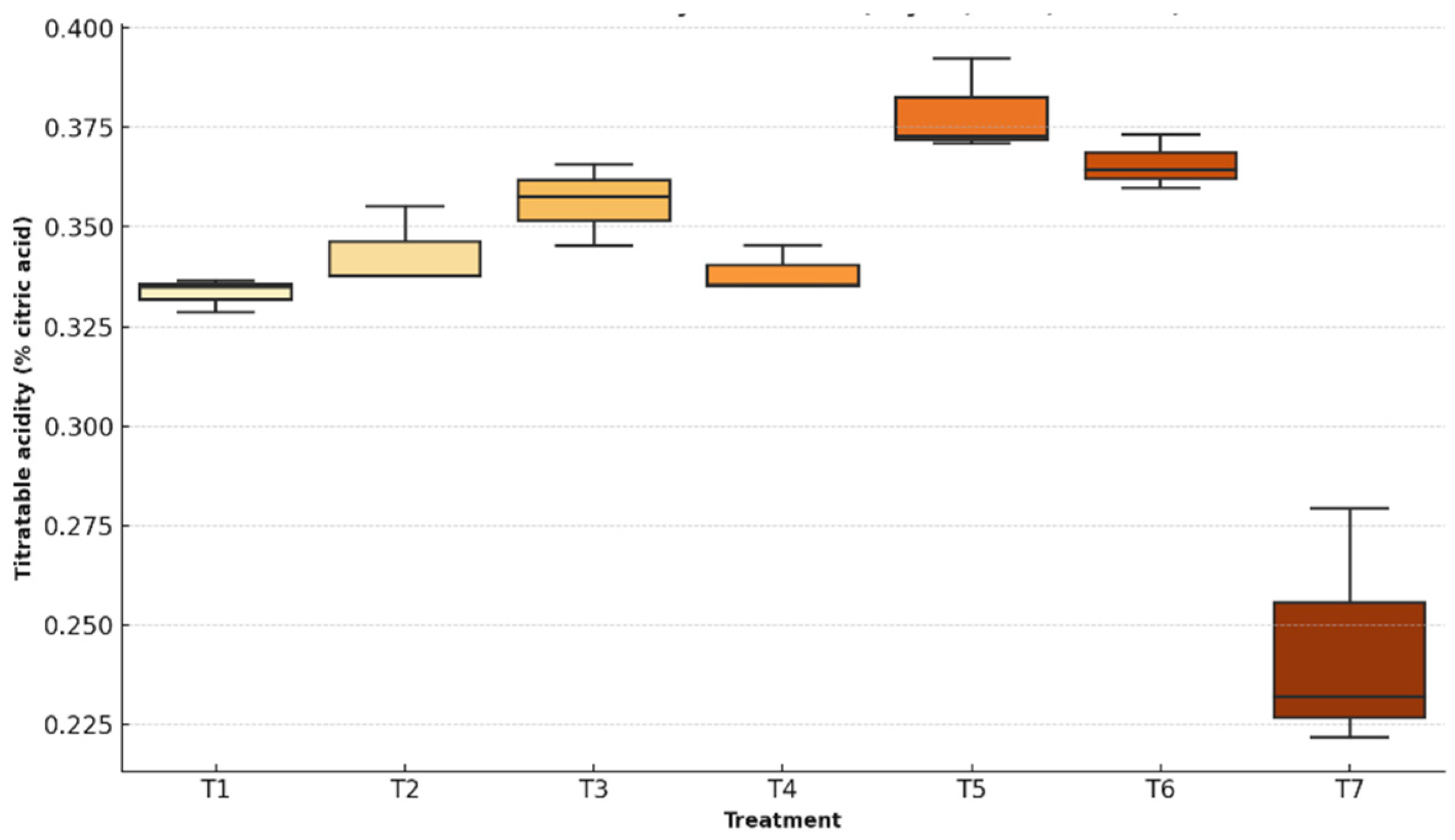

3.2.2. Titratable Acidity

Expressed as a percentage of citric acid, titratable acidity is an important indicator of fruit maturity and chemical stability during storage. Its progressive decline typically reflects the consumption of organic acids through respiratory and fermentative processes. An effective coating should help maintain stable acidity levels, thereby delaying fruit senescence.

Figure 9 shows a boxplot comparing the values between coated and uncoated fruits, highlighting the impact of each treatment on the preservation of the fruit’s acid profile.

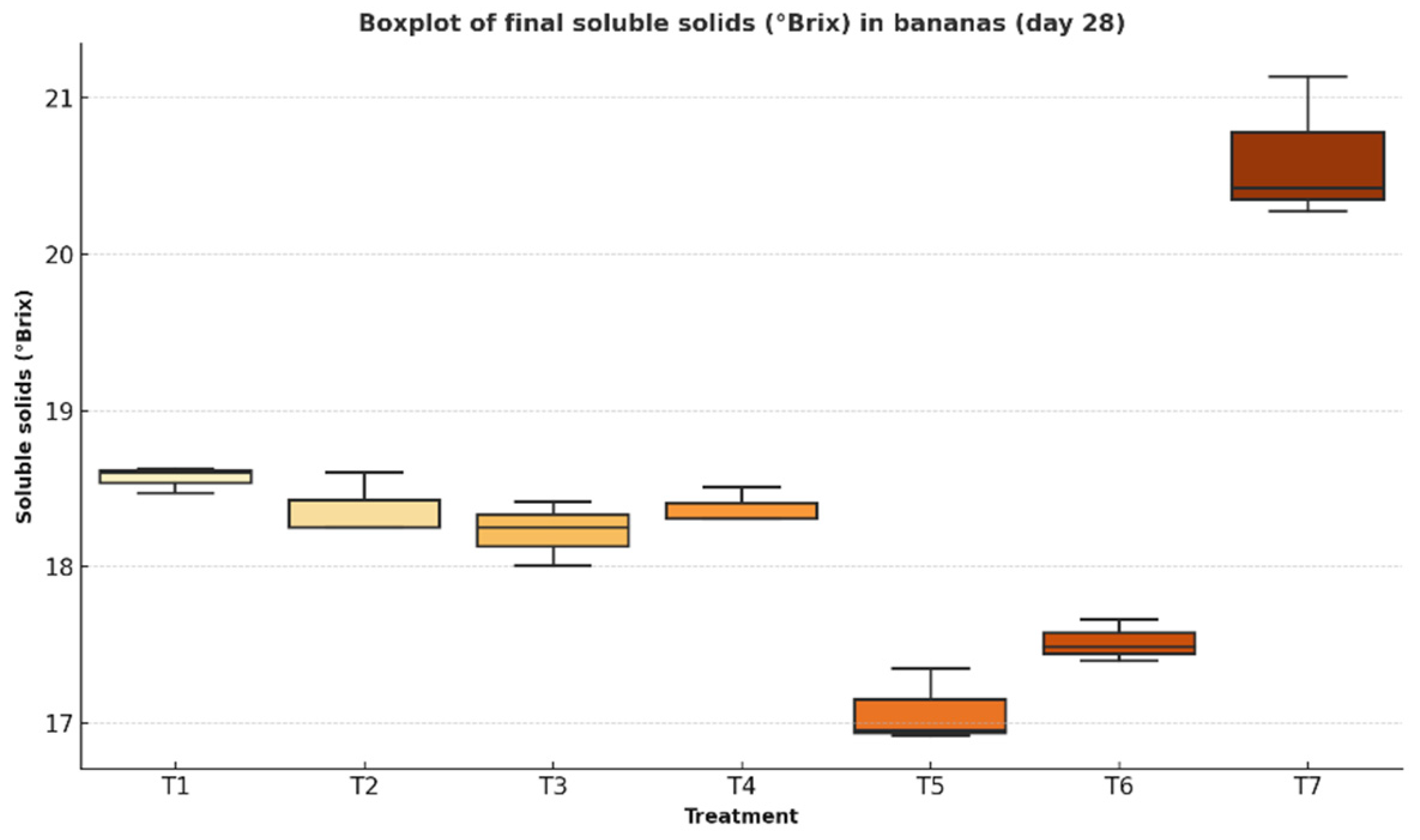

3.2.3. Soluble Solids

This parameter, expressed in degrees Brix (°Brix), reflects the concentration of soluble sugars in the fruit and is closely associated with the ripening process. A rapid increase in °Brix may indicate accelerated starch-to-sugar conversion, which can shorten the fruit’s shelf life.

Figure 10 presents a comparative boxplot of the treatments, allowing for the evaluation of each formulation’s effect on sugar accumulation and the modulation of ripening metabolism.

4. Discussion

The results obtained in this study demonstrate that the application of edible coatings had a significant effect on preserving the physicochemical properties of Musa paradisiaca fruits during storage, in comparison to the untreated control. The coatings contributed to maintaining structural integrity and slowing down biochemical changes associated with ripening and senescence.The following section provides a comprehensive discussion of the main findings, highlighting the behavior of each evaluated parameter

4.1. Physical Analysis

4.1.1. Weight Loss

All treatments showed progressive weight loss throughout storage. However, Treatment T5 was the most effective, recording the lowest cumulative loss (9.4% ± 0.3), in contrast to the control (T7), which exhibited a significantly higher loss (22.8% ± 0.8).

The effectiveness of T5 is attributed to the synergistic combination of whey, agar, cassava starch, and glycerol. The film-forming ability of starch and agar creates an effective moisture barrier, while glycerol improves flexibility without inducing stickiness [

14]. Whey contributes antimicrobial and antioxidant properties, which may reduce respiration rates and enhance fruit integrity. Conversely, coatings with excessive glycerol (e.g., T3 and T6) showed intermediate losses, suggesting that high plasticizer concentrations may weaken film structure and barrier capacity.

These observations align with prior research showing that cassava starch–beeswax coatings reduced papaya weight loss by 40% over 21 days [

33], and that chitosan–starch blends reduced banana weight loss to levels comparable with T2 and T3 [

34]. Also found reduced mass loss in plums using pectin and essential oils, highlighting the potential for further enhancement through bioactive compounds [

35].

Statistical analysis confirmed a highly significant treatment effect (F = 190.71, p < 0.0001). T5 outperformed all other treatments in reducing water loss, due to its balanced composition of hydrophilic polymers and plasticizers, which produced a cohesive, semipermeable film that effectively regulated transpiration and gas exchange.

4.1.2. Fruit Dimensions

Structural parameters such as peel thickness and fruit length provide insights into tissue dehydration and shrinkage, which affect overall fruit integrity and postharvest quality [

36].

ANOVA indicated highly significant effects of coating type on both peel thickness loss (F = 123.88, p < 0.0001) and length reduction (F = 84.66, p < 0.0001). Model assumptions were validated (Shapiro–Wilk and Levene’s tests), ensuring statistical robustness.

T5 preserved structure most effectively, with minimal peel thickness (4.9% ± 0.2) and length reduction (3.7% ± 0.2). The control (T7) showed the greatest contraction (10.3% ± 0.5 and 7.6% ± 0.4, respectively), with statistically significant differences.

This performance is attributed to the structural cohesion of the T5 matrix, formed by interactions among starch, agar, glycerol, and whey proteins, which reinforce the mechanical integrity of the coating and reduce cellular collapse during storage [

37]. Comparable outcomes were reported in mangoes and litchis coated with polysaccharide- and protein-based films [

38,

39].

4.1.3. Firmness

Firmness, a quality attribute, declined in all treatments due to cell wall degradation and turgor loss. ANOVA revealed a significant treatment effect (F = 139.41, p < 0.0001), with assumptions satisfied (Shapiro–Wilk: p = 0.787; Levene: p = 0.775).

T5 maintained the highest firmness (15.2% ± 0.4 loss) versus T7 (28.7% ± 0.7), likely due to its ability to reduce enzymatic activity (e.g., pectinases) and water loss. The film also contributed to a stable microenvironment that mitigated senescence [

40]. Overall, T5 proved highly effective in preserving tissue integrity and delaying softening, confirming its potential as a functional postharvest technology for tropical fruits [

41].

Previous research supports these findings: coatings based on polysaccharides and proteins preserved firmness in strawberries and bananas [

34,

41]. Glycerol’s plasticizing effect likely helped prevent cracking, maintaining barrier function [

16].

4.1.4. Color Parameters

The L* value, representing luminosity, declined in all treatments. Treatment T5 preserved brightness best (ΔL* = 5.5 ± 0.2), while T7 exhibited the greatest loss (ΔL* = 12.5 ± 0.5). ANOVA confirmed a significant effect (F = 152.28, p < 0.0001), with validated assumptions.

The reduced browning in T5-treated fruits may result from its oxygen-limiting film, which inhibits PPO activity and delays pigment oxidation [

42]. These results are consistent with earlier studies using protein- and polysaccharide-based coatings to limit chromatic degradation [

25,

39].

Chromaticity a* (Δa*) also increased with storage, indicating browning. T5 again showed the smallest change (2.4 ± 0.2) versus T7 (5.4 ± 0.4), supporting its role in limiting enzymatic oxidation.

Chromaticity b* (Δb*) measures yellow intensity. T5 minimized its reduction (3.3 ± 0.2) compared to the control (6.9 ± 0.4), indicating better carotenoid preservation. Similar outcomes have been reported for tropical fruits like papaya and mango coated with biopolymers [

34,

39,

43].

Together, these results confirm treatment T5 is effective in preserving visual attributes— for consumer acceptance and marketability.

4.2. Chemical Analysis

4.2.1. pH

This parameter serves as an indicator of the fruit’s physiological and microbiological condition during storage. A noticeable increase is typically associated with the degradation of organic acids and the onset of fermentative metabolic pathways linked to ripening.

One-way ANOVA revealed a highly significant effect of treatment on final pH values (F = 70.87, p < 0.0001). Model assumptions were validated by the Shapiro–Wilk test (W = 0.921, p = 0.090) and Levene’s test (F = 0.696, p = 0.657), confirming the robustness of the statistical approach. The T5 treatment exhibited the most stable pH, ending at 5.31 ± 0.01—closely aligned with its initial value of 5.20. In contrast, the uncoated control (T7) rose to 5.52 ± 0.02, indicating increased metabolic degradation.

These findings are consistent with previous studies reporting that edible coatings reduce pH shifts during storage by forming semipermeable barriers that limit gas exchange, thereby slowing acid loss and respiration [

41,

44]. The ability of T5 to maintain acid–base equilibrium reinforces its value in postharvest preservation.

4.2.2. Titratable Acidity

Closely tied to flavor and microbial stability, this parameter tends to decline as organic acids are consumed in respiratory processes and converted into volatiles during ripening.

Analysis of variance revealed highly significant differences among treatments (F = 29.11, p < 0.0001), with the Shapiro–Wilk test (W = 0.921, p = 0.090) and Levene’s test (F = 0.696, p = 0.657) confirming statistical assumptions. T5 showed the smallest reduction, with acidity decreasing from 0.45% to 0.39% citric acid. By contrast, the control group (T7) dropped from 0.38% to 0.25%, evidencing a higher degree of metabolic activity.

Previous literature supports these results. Fruits coated with starch, chitosan, or Aloe vera exhibited slower declines in acidity due to the restricted gas diffusion afforded by these biopolymers [

34,

41,

44]. The preservation of organic acids in T5-treated fruits strengthens its profile as a coating capable of extending freshness and flavor retention.

4.2.3. Soluble Solids

The accumulation of soluble sugars during ripening is reflected in °Brix values, which increase as enzymatic hydrolysis transforms starch reserves into simple sugars.

Treatments differed significantly in their °Brix progression (F = 67.00, p < 0.0001). Statistical assumptions were validated (Shapiro–Wilk W = 0.946, p = 0.282; Levene F = 0.478, p = 0.814). While all treatments experienced increases over the storage period, T5 showed the most moderate rise, from 15.7 to 17.3 ± 0.2 °Brix. In contrast, the control (T7) reached 20.7 °Brix, indicating faster ripening and complete starch conversion.

These results align with previous studies where chitosan- or starch-based coatings delayed sugar accumulation and modulated the ripening rate by reducing respiration and restricting ethylene exposure [

34,

38,

39]. The slower sugar conversion in T5 highlights its effectiveness in prolonging postharvest freshness.

4.3. Statistical Analysis

Across all physicochemical variables—weight loss, firmness, structural integrity, color, titratable acidity, pH, and °Brix—treatment T5 consistently demonstrated superior performance. It minimized deterioration while maintaining internal stability, indicating effective modulation of metabolic and physiological processes.

Tukey’s HSD post-hoc test (α = 0.05) confirmed statistically significant differences between T5 and the control (T7) in nearly every parameter. T5 was consistently grouped with the top-performing treatments, confirming its robustness and versatility.

The success of T5 can be attributed to the balanced formulation of whey, agar, cassava starch, and glycerol. This combination produced a functional semipermeable barrier that reduced gas exchange, limited enzymatic degradation, and preserved moisture content—delaying ripening without compromising fruit quality.

In summary, the evidence supports the use of T5 as a functional and sustainable edible coating for extending the shelf life of bananas. Nonetheless, further trials under commercial transport and market conditions, and with different cultivars, are recommended to validate its scalability and commercial potential.

5. Conclusions

The findings of this study demonstrate that the application of edible coatings significantly enhances the postharvest preservation of bananas (Musa paradisiaca). Among the formulations tested, the treatment composed of 5 g of whey, 5 g of agar, 10 g of cassava starch, and 10 g of glycerol proved to be the most effective in maintaining the physicochemical quality of the fruit.

This formulation notably reduced weight loss, preserved firmness, and minimized structural changes—such as peel thickness reduction and fruit length shrinkage—when compared to uncoated control. It also contributed to better color retention (lower loss of luminosity and chromaticity), moderated the increase in pH and decline in titratable acidity, and limited the rise in total soluble solids (°Brix), all of which indicate a slower and more controlled ripening process.

Statistical analyses, including ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD post-hoc test, confirmed that this formulation (referred to as T5) produced statistically significant differences across most evaluated variables. Its consistent performance highlights its efficacy in preserving the physicochemical properties of bananas during storage. These results support the use of this coating as a functional, sustainable, and low-impact postharvest strategy capable of extending shelf life without compromising sensory attributes or commercial value.

It is recommended that this coating be further validated under real-world storage and commercialization conditions. In addition, cost–benefit analyses should be conducted to assess its practical feasibility across different production systems. Optimizing the formulation by adjusting ingredient concentrations or incorporating bioactive compounds could further enhance its performance and broaden its applicability to other tropical fruits.

Future research should also include sensory evaluation and microbiological analyses to assess the coating’s potential in inhibiting fungal and bacterial growth during storage. A more comprehensive evaluation would provide robust evidence of the coating’s safety, effectiveness, and commercial potential as a postharvest preservation technology.

Author Contributions

All the mentioned authors have significantly contributed to the development and writing of this article. All authors have read and accepted the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the support of DECAB – Escuela Politécnica Nacional.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Capa Benítez, L.B.; Alaña Castillo, T.P.; Benítez Narváez, R.M. Importancia de la producción de banano orgánico. Caso: Provincia El Oro, Ecuador. Revista Universidad y Sociedad 2016, 8, 64–71. [Google Scholar]

- Agronomía, C. Tecnología Poscosecha. Agronomía Costarricense 2005, 29, 207–9. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. State of Food and Agriculture 2020: Moving Forward on Food Loss and Waste. FAO, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Boulos, M.; Lacey, M. Role of essential oils in food preservation: A review. Food Control 2020, 111, 203–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Medina, M.D.; Ruales, J. Postharvest Alternatives in Banana Cultivation. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, C.; Sánchez, S. Postharvest losses in banana production: A challenge for sustainable agriculture. Agricultural Systems 2021, 43, 58–64. [Google Scholar]

- Bello-Lara, J.E.; Balois-Morales, R.; Universidad Autónoma de Nayarit; Juárez-López, P.; Alia-Tejacal, I.; et al.; Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos Coatings based on starch and pectin from ‘Pear’ banana (Musa ABB), and chitosan applied to postharvest ‘Ataulfo’ mango fruit. Rchsh 2016, XXII, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arce Ortiz, K.L.; Ortega Villalba, K.J.; Ochoamartinez, C.I.; Vélez Pasos, C. Postharvest properties of banana gross michel coated with whey protein and chitosan. Vitae 2016, 23, S749–53. [Google Scholar]

- de la Fuente, A.; Rodríguez, A. Edible coatings: Applications and challenges for postharvest fruit preservation. Food Research International 2018, 107, 77–89. [Google Scholar]

- González, S.; Pérez, L. Uso de recubrimientos comestibles para la conservación postcosecha de frutas. Revista Latinoamericana de Tecnología Postcosecha 2017, 14, 34–45. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, S.; Lee, J. Effect of whey protein-based edible coatings on the shelf life of bananas. Food Chemistry 2016, 210, 120–5. [Google Scholar]

- Kurek, M.; Rybak, K. The role of agar in food packaging and preservation. Food Packaging and Shelf Life 2015, 6, 89–95. [Google Scholar]

- Ariza, R.; Martínez, F. Recubrimientos comestibles para la conservación de frutas tropicales. Revista Brasileira de Fruticultura 2018, 40, 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, M.; Ávila, J.; Ruales, J. Diseño de un recubrimiento comestible bioactivo para aplicarlo en la frutilla (Fragaria vesca) como proceso de postcosecha. 2016, 17, 276–287. [Google Scholar]

- López, E.M.; Díaz Rodríguez, F. Optimization of edible coatings for bananas: Effects on firmness and color retention. Food Science and Technology International 2019, 25, 592–601. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, P.J.; González Martínez, L. Incorporating glycerol in edible coatings for bananas: Effects on quality preservation. Food Science and Technology 2020, 41, 38–44. [Google Scholar]

- Assis, O.B.G.; de Britto, D. Revisão: coberturas comestíveis protetoras em frutas: fundamentos e aplicações. Braz J Food Technol 2014, 17, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaya-Esparza, L.M.; Pérez-Larios, A.; Ruvalcaba-Gómez, J.M.; Sánchez-Burgos, J.A.; Romero-Toledo, R.; Montalvo-González, E.; et al. Funcionalización de los recubrimientos a base de quitosano para la conservación postcosecha de frutas y hortalizas. TIP Revista especializada en ciencias químico-biológicas 2020, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, A.R.; González. Effect of edible coatings on postharvest quality of bananas. Journal of Food Science 2019, 83, 1245–52. [Google Scholar]

- Pothitirat, A.W.; Arnone. Color evaluation of coated bananas during postharvest storage. Postharvest Biology and Technology 2020, 163, 111106. [Google Scholar]

- Chiriboga, J. Hacia una agricultura más sostenible: recubrimientos comestibles naturales para extender la vida útil de las frutas. VITSC 2025, 2, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, P.E.; González Pérez, R. Effect of glycerol on banana quality during storage with edible coatings. Journal of Food Science 2018, 83, 1801–8. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. In Food Loss and Waste in the Context of Sustainable Development Goals; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2021.

- López, E.M.; Díaz. Effect of whey protein edible coatings on banana quality during storage. Food Packaging and Shelf Life 2020, 21, 21–7. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, F.A.; González. Effects of polysaccharide-based edible coatings on banana shelf life. Postharvest Biology and Technology 2018, 142, 60–7. [Google Scholar]

- Chicaiza Sangoquiza, A.A. Impacto de los recubrimientos comestibles en la calidad y vida de útil de frutas y verduras frescas. VITSC 2025, 1, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Kacem; et al. M. Effect of edible coatings on weight loss and texture of bananas during storage. Food Science and Technology 2020, 38, 212–8. [Google Scholar]

- FAO, Italia. Prevencion de Perdidas de Alimentos Poscosecha: Frutas, Hortalizas, Raices y Tuberculos. Manual de Capacitacion; Food & Agriculture Org., 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Borges, C.V.; Amorim, E.P.; Leonel, M.; Gomez Gomez, H.A.; Santos TPRdos Ledo CAda, S.; et al. Post-harvest physicochemical profile and bioactive compounds of 19 bananas and plantains genotypes. Bragantia 2018, 78, 284–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International, A. AOAC 981.12: pH of Food, 15th ed; AOAC International: Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- International, A. AOAC 942.15: Titratable Acidity in Fruits, 16th ed.; AOAC International: Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- International, A. Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International, 16th ed.; Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Arlington, VA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- González-Rodríguez, M.S. Manejo postcosecha del plátano (Musa X paradisiaca AAA subgroup Cavendish) en Tecomán, Colima, México. Agro Productividad 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqbool, M.; Ali, A.; Ramachandran, S.; Smith, D.R.; Alderson, P.G. Control of postharvest anthracnose of banana using a new edible composite coating. Crop Protection 2010, 29, 1136–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, D.; Aguilar, P.; Wong, J.; Rojas, R. Aplicación de recubrimientos comestibles a base de pectina, glicerol y cera de candelilla en frutos cultivados en la Huasteca Potosina. Ciencias Naturales y Agropecuarias 2017, 4, 20–28. [Google Scholar]

- de Lorena, M. Almidón modificado: Propiedades y usos como recubrimientos comestibles para la conservación de frutas y hortalizas frescas. 2018, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Valdés, D.; Bautista Baños, S.; Fernández Valdés, D.; Ocampo Ramírez, A.; García Pereira, A.; Falcón Rodríguez, A. Películas y recubrimientos comestibles: una alternativa favorable en la conservación poscosecha de frutas y hortalizas. Revista Ciencias Técnicas Agropecuarias 2015, 24, 52–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, A.; Muhammad, M.T.M.; Sijam, K.; Siddiqui, Y. Effect of chitosan coatings on the physicochemical characteristics of Eksotika II papaya (Carica papaya L.) fruit during cold storage. Food Chemistry 2010, 118, 620–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oms-Oliu, G.; Soliva-Fortuny, R.; Martín-Belloso, O. Using polysaccharide-based edible coatings to maintain quality of fresh-cut Fuji apples. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2008, 41, 146–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mera, G.C.; Tandalla, J.V.G.; Carvajal, E.R.C.; Ordoñez, O.A.A. Factores determinantes en el proceso de maduración y su relación con los diferentes cambios en frutas y hortalizas. Reciena 2024, 4, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivas, G.I.; Barbosa-Cánovas, G.V. Edible coatings for fresh-cut fruits. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2008, 48, 496–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, L.F.A.; Maya, C.F.H.; Troya, E.T.T.; Luzuriaga, S.A.G. Estudio del efecto del pardeamiento enzimático en la calidad nutricional del banano (musa paradisiaca L.) . Reciena 2023, 3, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, M.; Khan, M.R.; Hussain, S. Impact of edible coatings on the preservation of postharvest fruit quality. International Journal of Food Science and Technology 2020, 55, 3424–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero, D.; Serrano, M.; Martínez-Romero, D.; Guillén, F.; Castillo, S.; Zapata, P.; et al. Improving the flavour of table grapes by preharvest and postharvest practices. Food Science and Technology International 2003, 9, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).