Introduction

Acne vulgaris is one of the most common inflammatory skin conditions.(1–7) It primarily affects the face but can involve the chest, back, and shoulders.(1) Due to its relapsing and persistent nature, acne may qualify as a chronic disease as defined by the World Health Organization and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.(8) A major consequence of acne is the formation of scars, affecting up to 95% of patients.(9,10) Scarring is a consistent reminder of past episodes and has a profound impact on quality of life, undermining self-confidence and provoking emotional distress.(6,8,11,12) In fact, the psychological and functional burden associated with acne scarring is comparable to that of debilitating chronic diseases such as asthma and epilepsy.(8) Acne scars result from disruptions in the wound-healing process. Typically, this process begins with inflammation, followed by proliferation and tissue remodeling.(6,10) These phases involve migrating various cell types into the wound, angiogenesis, and reforming the extracellular matrix (ECM). (13–15) When this process is disrupted, an imbalance between collagen production and degradation occurs. Excessive collagen production produces hypertrophic or keloid scars, while insufficient collagen production produces atrophic scars.(6,12,16–18) Most acne scars are atrophic, whereas hypertrophic or keloid scars are less common.(10,12) Due to the variety of scar types, their three-dimensional aspect and their evolution over time, the assessment of acne scars is a challenge that can hinder clinical management. Among the various grading systems used, the Echelle d’Evaluation Clinique des Cicatrices d’acne (ECCA) scale is a quantitative validated framework, with high interobserver reliability.(19) The ECCA grading scale categorizes six specific scar types, each assigned a semi-quantitative score (0–4) and a weighting factor (15–50) to reflect their severity and clinical impact. The overall scar grade is calculated by multiplying the semi-quantitative score by the weighting factor. Two subgrades are defined: one for four atrophic characteristics (V-shaped, U-shaped, M-shaped, and superficial elastolysis) and another for two hypertrophic/keloid characteristics (hypertrophic inflammatory and keloid scars). The total score, referred to as the Global ECCA Score, is obtained by summing the subgrades and ranges from 0 to 540.(20)

A wide range of effective methods for reducing acne scars are available depending on the type of scar, its location, and the depth of the lesions [

6,

10]. The primary focus is on delivering treatments with minimal side effects, enabling patients to quickly resume their daily activities.(6) Energy-based devices are an attractive non-invasive alternative that offers an effective, low-risk therapy for most types of atrophic acne scars.(6,10,12,21) Ablative lasers deliver high energy to the skin, superheating water molecules in the epidermis and vaporizing skin cells in a peeling effect. Below the vaporization zone, thermal damage stimulates skin cells to produce new collagen. Non-ablative lasers deliver energy into the dermis creating thermal coagulation without destroying the overlying epidermis, resulting in fewer side effects and shorter recovery. However, clinical improvement may be moderate. Fractional technology creates pixelated zones of thermal damage, known as Micro Thermal Treatment Zones (MTZs), which consist of affected tissue columns surrounded by intact tissue. The surrounding unaffected tissue promotes rapid repair through epidermal stem cell regeneration and fibroblast-driven neo-collagenesis, leading to effective skin remodeling.(10,12,18,22–25) Despite the wide range of lasers available, acne scars remain challenging, and research into new strategies continues. Combination approaches have been proposed to optimize clinical outcomes [

12], with several studies suggesting that the use of multiple laser wavelengths may improve results. (6) One of the main fractional ablative laser devices currently used for acne scars is the Carbon dioxide (CO2) laser, emitting a 10,600 nm beam. (12)

This study presents a retrospective comparison of acne scar treatment outcomes using two CO2 laser systems.

Materials and Methods

Consecutive patients (≥16 years) attending the San Luca Clinic (Tirana, Albania) for laser-based treatment of acne scars were included in the analysis and prospectively followed up for 6 months between April 2022 and March 2024. Patients with an active local infection at the treatment site, photo-aggravated skin disease, a cultured epithelial autograft at the treatment site, unstable epithelium within a few weeks of injury, or ongoing/within 1 month of completion of isotretinoin treatment were excluded from the study.

Following initial confirmation of patient eligibility, patient records were anonymized before data analysis. Patient demographics, treatment outcomes, and treatment safety information were extracted from the database.

The ProScan scanning applicator (Alma Hybrid, Alma Lasers Ltd.) enables the emission of ablative (10,600 nm) and nonablative (1570 nm) wavelengths in a dual side-by-side fractional manner in a desired ratio. In this study a ratio of 1:1 was used that indicates that each beam of CO2 ablative laser is followed by a beam of 1570 nm of nonablative laser, making 50% of the pixels CO2 and 50% 1570 nm. The settings of each beam includes power (measured in Watts), pulse duration (measured in milliseconds), and energy (mJ), which are derived from multiplying these two parameters. The density of the beams that determines the amount of pixels/cm2 is also customizable. In this study, the 10,600 nm mode was employed at a pulse duration of 1.6-1.8 msec and a power setting of 22-30 Watts, and the 1570 nm mode at a pulse duration of 4 msec and a power setting of 10-12 Watts.

The LiteScan applicator (Alma Pixel CO2, Alma Laser Ltd., Israel) enables minor ablation achieved with extensive coagulation. In this study, the applicator was employed at a pulse duration of 1.6-1.8 msec and a power setting of 20-27 Watts.

All laser procedures were performed by the same surgeon. After disinfecting the target area, local anesthesia (lidocaine 100 mg/50 ml) was applied. Laser parameters were first set to the lowest possible setting and gradually adjusted to suit the size and thickness of the scar. Following treatment, the site was cleaned with antiseptics.

The physician evaluated the acne scars using the ECCA grading scale(20), based on semiquantitative, weighted assessments of the scars, before the treatment and again at the follow-up visits, six to twelve months after the final treatment session. In addition, the physician compared photographs taken before the treatment and at the follow-up visit using identical settings.

Clinical efficacy was assessed by comparing the Global ECCA score before and after treatment and evaluating the percentage change in the score, calculated using the formula (Global ECCA score before treatment—Global ECCA score after treatment) / Global ECCA score before treatment) × 100.

Device and procedure-related adverse events were documented.

The analysis was performed using R version 4.3.3. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. Descriptive statistics provide a summary of the dataset. Continuous variables are reported as mean ± SD, and categorical variables as frequencies and percentages. Due to the non-parametric nature of the data, the choice of statistical tests was adjusted to ensure reliable analysis. The Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test was used to compare ECCA Global scores before and after treatment within each group. For comparative analysis, the Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Test was used to assess differences in efficacy between groups. The Chi-square test was used to evaluate differences in the incidence of adverse events between groups.

Results

All patients included in this analysis underwent laser treatment for acne scars. In total, 45 procedures were performed with the Hybrid laser device (Alma Hybrid/ProScan), and 43 procedures were performed with the Pixel CO

2 laser device (Alma Pixel CO

2/LiteScan). The distribution of patients’ age, gender, treated body area, number of treatment sessions, and skin type is presented in

Table 1.

All 88 patients completed the treatments and returned to follow up visits, and overall improvement was achieved with both ablative and combined ablative and non-ablative laser modalities after an average of four sessions.

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 represent the aesthetic improvement observed following the Hybrid/ProScan and CO

2/LiteScan treatments, respectively.

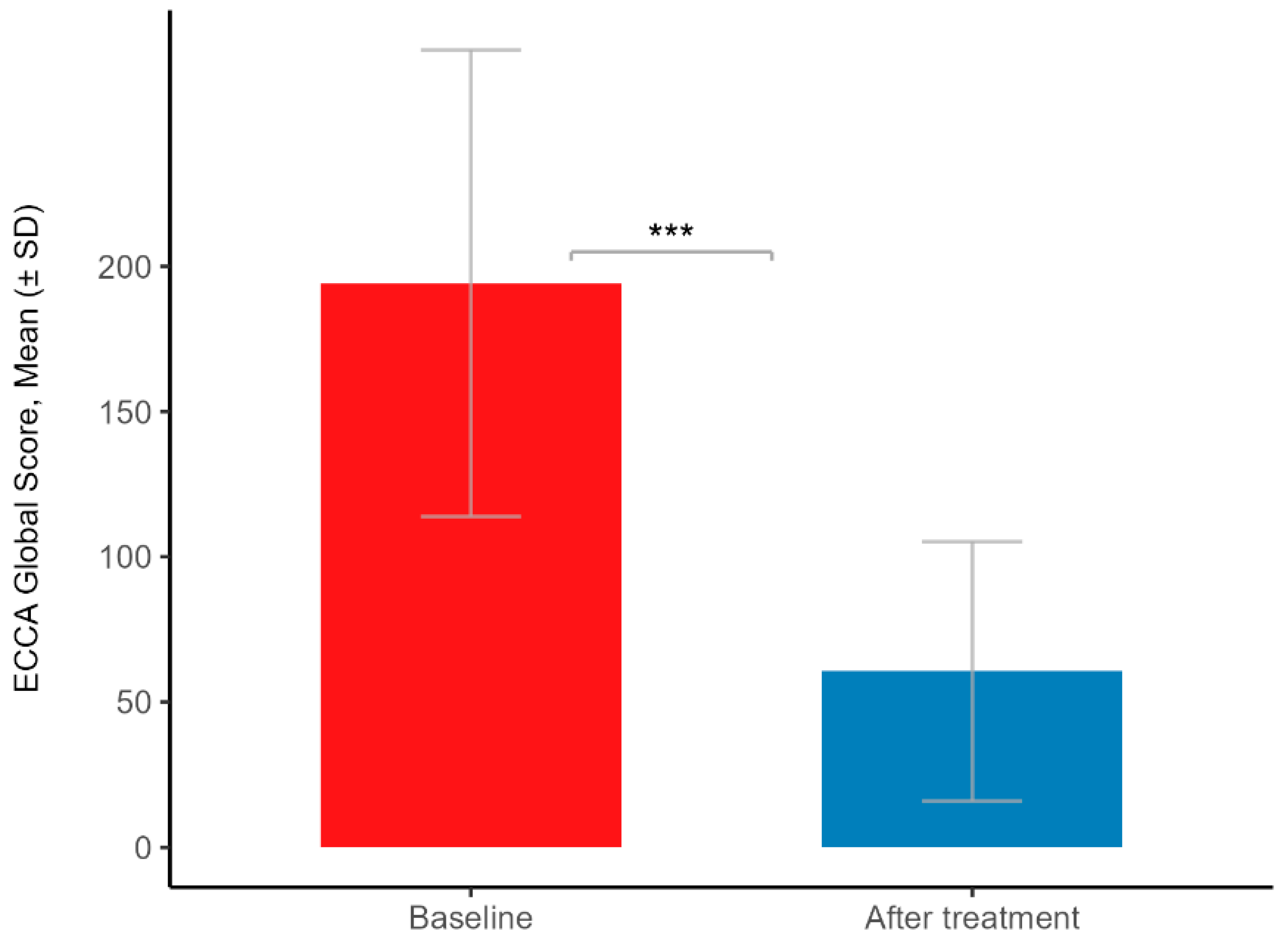

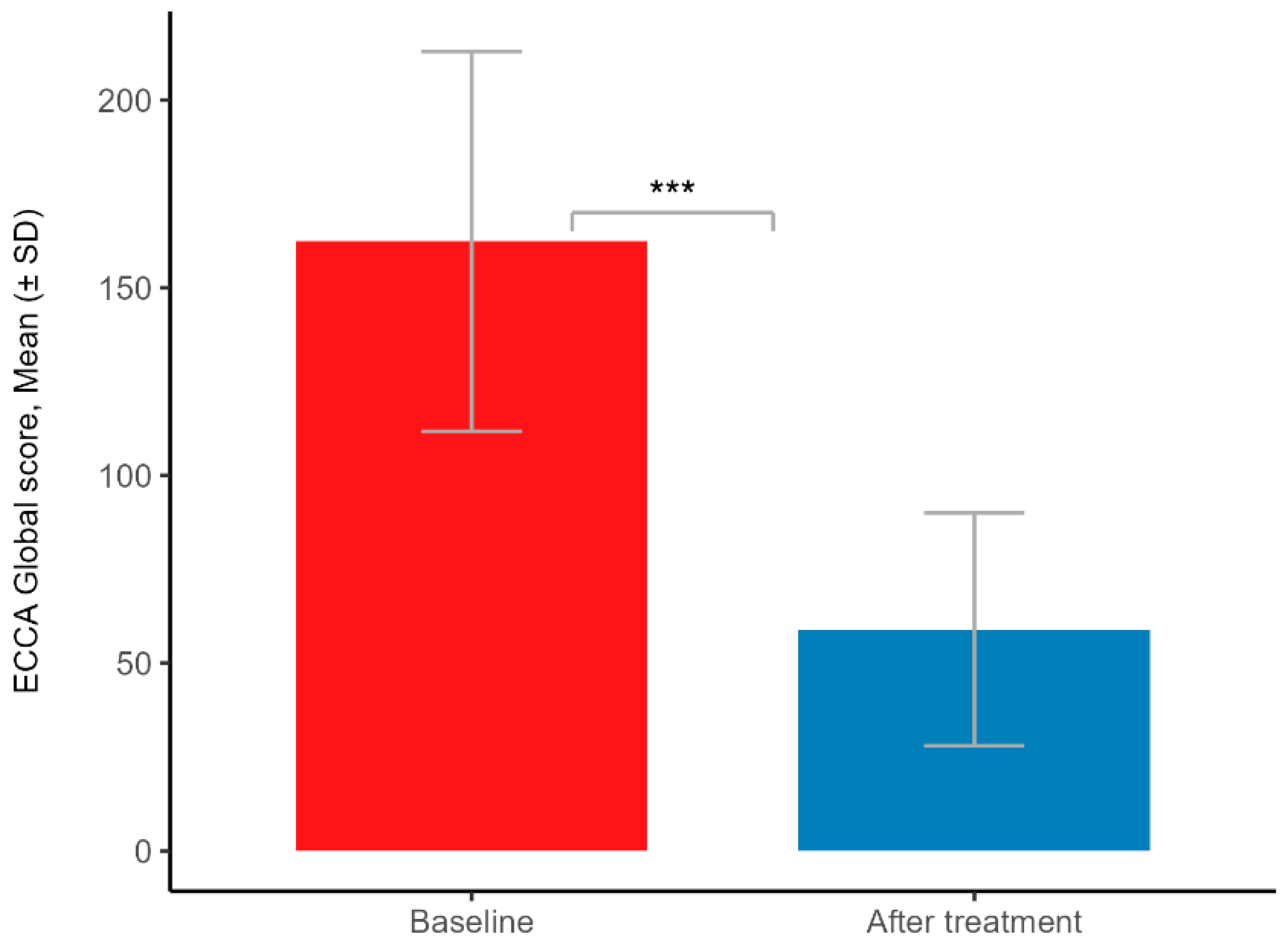

In the ProScan-treated group, the mean percentage change in Global score was 69.4% ± 18.3 (mean ± SD), whereas in the LiteScan-treated group, the mean percentage change in Global score was 64.7% ± 11.1 (mean ± SD). The statistical analysis demonstrated significant differences in Global scores before and after treatment for both groups, with p-values < 0.001 (Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test). In the ProScan group, the mean Global score decreased from 194 ± 80.3 (mean ± SD) at baseline to 60.6 ± 44.6 (mean ± SD) after the treatment, and in the LiteScan group, the mean Global score decreased from 162 ± 50.6 (mean ± SD) at baseline to 59 ± 31 (mean ± SD) after treatment. The results are presented in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4.

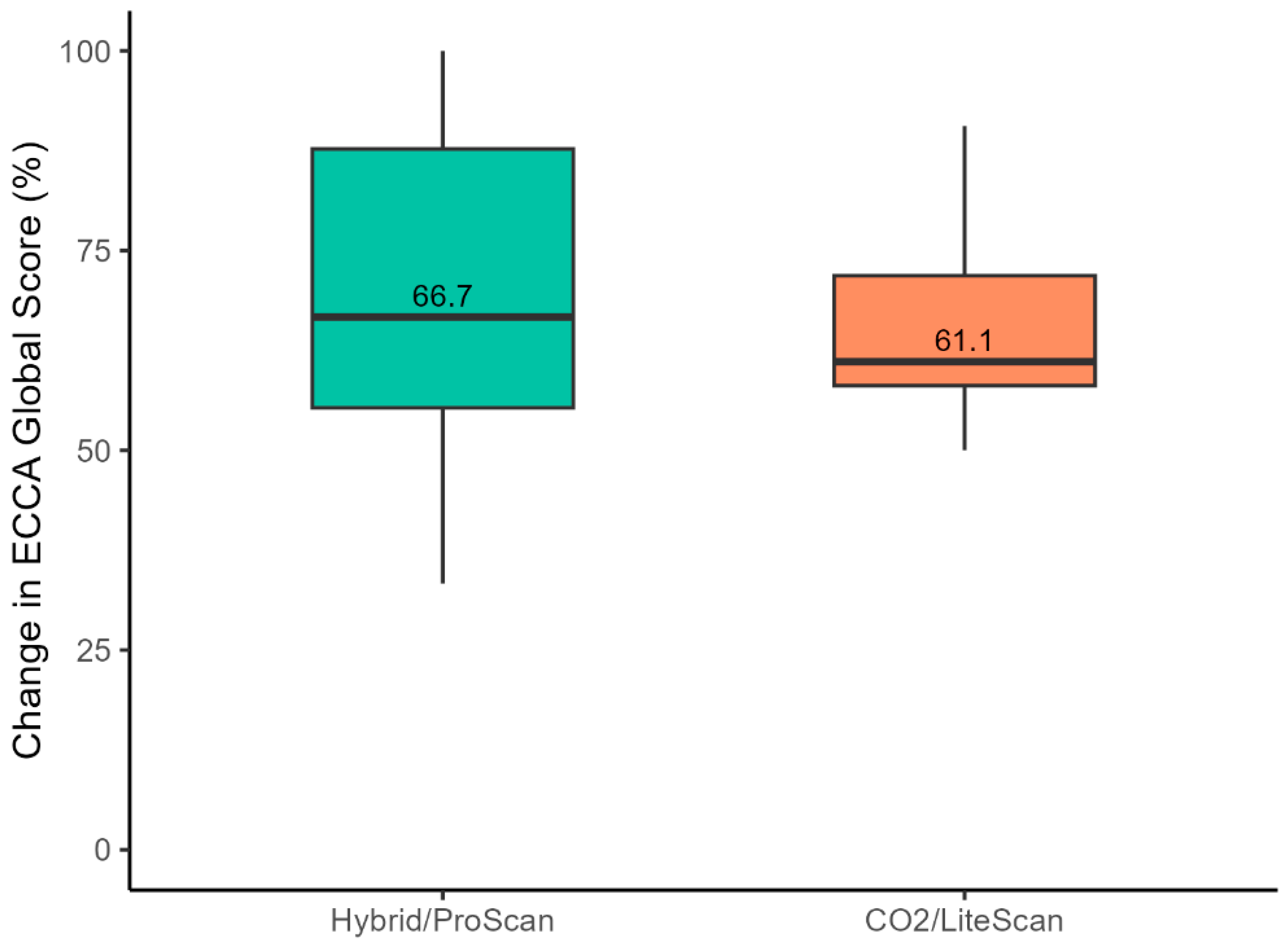

Comparative outcomes between groups: Visible improvements in acne scar severity were observed after 7-8 weeks in the Hybrid/ProScan group, while results in the CO

2/LiteScan group appeared after approximately 3 months. The statistical analysis revealed no significant difference in the percentage change in ECCA Global scores from baseline to post-treatment between the groups, with p-value >0.05 (Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Test). The median percentage change was 66.7% (IQR: 55.3 – 88.7%) in the Hybrid/ProScan group and 61.1% (IQR: 58.1 - 71.8%) in the CO

2/LiteScan group.

Figure 5 presents the results.

No unanticipated adverse events (AEs) were reported in either treatment group. Anticipated treatment reactions observed in some patients were mild and transient erythema or post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH), which resolved within a few days. The frequency of these anticipated treatment reactions was calculated for both treatment groups. In the Hybrid/ProScan-treated group, the frequency was 15.56%, with 7 out of 45 participants experiencing side effects, while in the CO2/LiteScan-treated group, the frequency was 16.28%, with 7 out of 43 participants. A Chi-square test indicated no statistically significant difference between the treatment groups in terms of side effects occurrence (p-value > 0.05). Recovery time was shorter in the Hybrid/ProScan-treated group, with the treatment generally being more tolerable and less painful compared to the CO2/LiteScan-treated group.

Discussion

This study demonstrates the high efficacy and safety of both laser devices in the treatment of acne scars, with significant improvement in post-treatment scar grading compared to baseline. Treatment with the Alma Hybrid/ProScan showed better improvement than the Pixel CO2 /LiteScan, but the difference was not statistically significant. Nevertheless, the improvement in the hybrid group was evident after a much shorter period of time. There were no AEs, and only mild and transient anticipated side effects were observed, with a low frequency in both groups and an even lower frequency in the Hybrid group, although not statistically significant. However, the recovery time was shorter, and the treatment was more tolerable in the Hybrid group than in the CO2 group for the same CO2 laser mode parameters. This suggests a potential trend toward improved safety and efficacy with the Hybrid device, but further research is needed to substantiate these observations.

Improvement rates for acne scars treated with ablative laser resurfacing, as measured by the ECCA scale, can vary, typically ranging from 40% to as high as 75%. While higher rates of improvement are possible, they may be associated with a greater likelihood of adverse events. For example, Dai et al. (2023) investigated the comparative efficacy and safety of Nd:YAG picosecond lasers (P-MLA) and ablative fractional 2940-nm Er:YAG lasers (AF-Er) in a controlled, split-face study with ECCA percent reductions recorded at 39.11% for picosecond lasers and 43.73% for ablative fractional lasers.(26) Similarly, Ding et al. (2023) achieved a 60% improvement in 68 patients with facial acne scars treated with fractional CO2 laser.(27) Additionally, Zhang et al. (2023), in a randomized split-face design, evaluated thirty-three Asian patients treated for acne scars and reported ECCA score reductions of 56.4% for Microplasma Radio Frequency technology and 59.2% for the fractional CO2 laser system.(28) Yuan et al. (2023) compared the effects of different fluences and densities in fractional CO2 laser treatment of acne scars in 20 patients. Using the ECCA grading scale, results showed up to 75% improvement with higher densities or fluences. However, side effects were more pronounced and lasted longer in patients treated with higher densities or fluences.(29) In the current study, the improvements in ECCA scores (mean 69.4% and 64.7% for LiteScan and ProScan, respectively) are relatively high compared to those reported in the literature. Given the high safety profile demonstrated by both devices with no associated adverse events, these improvement rates are remarkable.

An exaggerated wound-healing response is closely associated with acne scarring.(30) Wound repair includes re-epithelialization, angiogenesis, and remodeling of the ECM - a dynamic network of macromolecules and proteolytic enzymes that, along with cells such as fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and keratinocytes, form the skin.[

14] Dysregulated ECM remodeling is considered to be a fundamental cause of scarring.(11,14) The ECM participates in wound healing go through direct and indirect interactions with growth factors such as fibroblast growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor, epidermal growth factor, bone morphogenetic proteins, and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β),(14,31) with the latter playing a central role in ECM remodeling. (14,30–33) TGF-β regulates the production of several ECM components, including collagens, the most abundant proteins of the ECM. Collagens form a relaxed network of cross-linked, long-chain fibers that provide the strength and elasticity of normal tissue.(14) It has been suggested that TGF-β promotes a compensatory recovery of collagen I over collagen III, thereby increasing the ratio of type I to type III collagen.(34) A low ratio of collagen I to collagen III in scarless fetal skin suggests that an adequate level of collagen III is critical to prevent scarring. Consistent with these findings, Moon et al. (2019) observed an elevated ratio of collagen I to collagen III, along with substantially higher levels of TGF-β1, in patients prone to acne scarring compared to those not prone to scarring. They proposed that these factors, leading to an unbalanced configuration of the ECM, may be at the root of atrophic acne scarring.(11) Restoring the dermal matrix to resemble unwounded tissue could improve scar quality, enhancing tensile strength and elasticity.(14,31) Ablative fractional resurfacing facilitates deep skin remodeling by penetrating to the low reticular dermis. It may reduce aberrant wound healing through the regulation of cytokine and growth factor secretion, promoting proper ECM organization.(35,36) The fractional pattern, characterized by the creation of Micro ThermalMicro Thermal zones (MTZs), supports re-epithelialization and collagen remodeling by stimulating the adjacent unaffected skin.(21,25,32) Histological evidence from multiple studies has shown modulation of cytokines and other extracellular matrix components, including collagen remodeling, following fractional ablative CO

2 laser treatment.(37–39) Specifically, in the case of acne scars, the fractional CO

2 laser is well-established as an effective treatment, with numerous studies validating its efficacy.(18,27,40–45) In recent years, research efforts have mainly focused on optimizing treatment parameters,(25,29) and exploring combination strategies with CO

2 laser to further enhance efficacy and safety.(32,46,47)

The Hybrid ProScan handpiece used in this study combines an Ablative Fractional Laser (AFL) and a Non-Ablative Fractional Laser (NAFL) in a single modality. The combination of ablative and non-ablative lasers is recognized as an effective approach for improving cosmetic outcomes. This dual-energy technique utilizes the precision and efficacy of ablative laser to target deep tissue and stimulate robust collagen remodeling alongside the gentler effects of non-ablative laser, which support skin healing. Such synergistic effects have been widely documented across various dermatological conditions.(48–50) Specifically for the treatment of acne scars, Kim et al (2009), in a split face comparative study, used a non-ablative 1,064-nm Nd:YAG laser treatment following an AFL CO2 laser treatment on one facial half and AFL CO2 laser treatment on the contralateral facial half in twenty subjects with mild to severe acne scars. Results showed that the combination of AFL treatment with NAFL treatment produced superior scar improvement with fewer complications than AFL treatment alone.(51) Recent advances in laser technology have further refined this concept by enabling the seamless integration of AFL and NAFL within a single device. This innovation not only preserves the proven benefits of combining these wavelengths in one treatment but also enhances treatment efficiency, safety, and convenience. For example, Belletti et al. (2023), in a pilot study, demonstrated that a dual-wavelength laser combining CO2 and 1540 nm effectively improved facial atrophic acne scars. Patients reported excellent to slight improvements, minimal side effects, short downtime (5.8 ± 0.5 days), and a low risk of scarring or hypopigmentation.(52) Similarly, Naranjo and Lopez (2024) demonstrated in 16 patients that a multimodal CO2 and 1570 nm laser system effectively improved facial acne scars. Reductions were observed in scar volume (47.0 ± 7.9% mm3) and affected area (43.2 ± 8.6% mm2). Additionally, high satisfaction and no serious adverse reactions were reported.(53)

In this study, both the Hybrid and CO2 Pixel devices provided safe treatment options. Although the Hybrid laser device exhibited a slightly lower frequency of post-treatment reactions compared to the CO2 Pixel, the difference was not statistically significant. However, the Hybrid group experienced shorter recovery times, and the treatment was generally more tolerable and less painful compared to the Pixel group. While definitive conclusions about a superior safety profile for either device cannot be drawn, this study adds to the existing evidence supporting the efficacy of combining AFL and NAFL energies for treating acne scars. Based on previous research indicating a high safety profile for these treatments, we hypothesize that larger study groups will be necessary to more effectively investigate potential safety differences, particularly due to the low incidence of treatment side effects.

Limitations

Limitations of this study include its retrospective design and the absence of a control group. Despite these limitations, statistically significant improvements in scarring were observed in both treatment groups, indicating that both devices are effective. However, further well-controlled, long-term studies are necessary to assess the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of laser-based therapies for the treatment of acne scarring. Future research should also incorporate objective measures to evaluate treatment outcomes more accurately and compare the performance of each device.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that fractional CO2 laser devices provide safe and effective treatment options for the treatment of acne scars. Statistically significant improvements were observed in both groups following treatment with two different CO2 laser systems. The incorporation of non-ablative fractional laser as part of the treatment may enhance both safety and efficacy, warranting further investigation in future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Arminda Avdulaj; Methodology, Arminda Avdulaj; Investigation, Arminda Avdulaj, Shaked Menashe, Yoad Govrin-Yehudain, Eran Hadad, Sharon Moscovici, Omer Dor, and Lior Heller; Resources, Arminda Avdulaj, Shaked Menashe, Yoad Govrin-Yehudain, Eran Hadad, Sharon Moscovici, Omer Dor, and Lior Heller; Writing—original draft preparation, Arminda Avdulaj; Writing—review and editing, Shaked Menashe, Yoad Govrin-Yehudain, Eran Hadad, Sharon Moscovici, Omer Dor, and Lior Heller. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Funding

No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Shamir Medical Center, Approval # 0083-23-ASF, date: 20 June 2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. The authors affirm that human research participants provided informed consent for the publication of the images in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available and were provided as part of the submitted data materials.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the statistical analysis and text editing services of Merav Cohen. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wilcock J, Kuznetsov L, Ravenscroft J, Rafiq MI, Healy E. New NICE guidance on acne vulgaris: implications for first-line management in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2021 Nov 26;71(713):568–70. [CrossRef]

- Alexis A, Tan J, Rocha M, Kerob D, Demessant A, Ly F, et al. Is Acne the Same Around the World? J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2024 Sep;17(9):16–22.

- Cong TX, Hao D, Wen X, Li XH, He G, Jiang X. From pathogenesis of acne vulgaris to anti-acne agents. Arch Dermatol Res. 2019 Jul;311(5):337–49. [CrossRef]

- Dréno B. What is new in the pathophysiology of acne, an overview. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017 Sep;31 Suppl 5:8–12. [CrossRef]

- Rocha MA, Bagatin E. Skin barrier and microbiome in acne. Arch Dermatol Res. 2018 Apr;310(3):181–5. [CrossRef]

- Chilicka K, Rusztowicz M, Szyguła R, Nowicka D. Methods for the Improvement of Acne Scars Used in Dermatology and Cosmetology: A Review. J Clin Med. 2022 May 12;11(10). [CrossRef]

- Kim HJ, Kim YH. Exploring Acne Treatments: From Pathophysiological Mechanisms to Emerging Therapies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2024 Jan;25(10):5302. [CrossRef]

- Layton AM, Gupta G, Seukeran D, Maruthappu T, Gaillard S, Whitehouse H, et al. What’s New After NICE Acne Guidelines. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2024 Oct 1;14(10):2727–38.

- Xu W, Sinaki DG, Tang Y, Chen Y, Zhang Y, Zhang Z. Acne-induced pathological scars: pathophysiology and current treatments. Burns & Trauma. 2024 Jan 1;12:tkad060. [CrossRef]

- Bhargava S, Cunha PR, Lee J, Kroumpouzos G. Acne Scarring Management: Systematic Review and Evaluation of the Evidence. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018 Aug;19(4):459–77. [CrossRef]

- Moon J, Yoon JY, Yang JH, Kwon HH, Min S, Suh DH. Atrophic acne scar: a process from altered metabolism of elastic fibres and collagen fibres based on transforming growth factor-β1 signalling. British Journal of Dermatology. 2019 Dec 1;181(6):1226–37. [CrossRef]

- Sadick NS, Cardona A. Laser treatment for facial acne scars: A review. Journal of Cosmetic and Laser Therapy. 2018 Nov 17;20(7–8):424–35. [CrossRef]

- Karppinen SM, Heljasvaara R, Gullberg D, Tasanen K, Pihlajaniemi T. Toward understanding scarless skin wound healing and pathological scarring. F1000Res. 2019 Jun 5;8:787. [CrossRef]

- Xue M, Jackson CJ. Extracellular Matrix Reorganization During Wound Healing and Its Impact on Abnormal Scarring. Advances in Wound Care. 2015 Mar;4(3):119–36. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Guarino M, Hernández-Bule ML, Bacci S. Cellular and Molecular Processes in Wound Healing. Biomedicines. 2023 Sep 13;11(9):2526. [CrossRef]

- Kurokawa I, Layton AM, Ogawa R. Updated Treatment for Acne: Targeted Therapy Based on Pathogenesis. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021 Aug;11(4):1129–39. [CrossRef]

- Liu L, Xue Y, Chen Y, Chen T, Zhong J, Shao X, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of acne scars in patients with acne vulgaris. Skin Res Technol. 2023 Jun;29(6):e13386. [CrossRef]

- Xu Y, Deng Y. Ablative Fractional CO2 Laser for Facial Atrophic Acne Scars. Facial plast Surg. 2018 Apr;34(02):205–19. [CrossRef]

- Clark AK, Saric S, Sivamani RK. Acne Scars: How Do We Grade Them? Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018 Apr 1;19(2):139–44.

- Dreno B, Khammari A, Orain N, Noray C, Mérial-Kieny C, Méry S, et al. ECCA Grading Scale: An Original Validated Acne Scar Grading Scale for Clinical Practice in Dermatology. Dermatology. 2007;214(1):46–51. [CrossRef]

- Salameh F, Shumaker PR, Goodman GJ, Spring LK, Seago M, Alam M, et al. Energy-based devices for the treatment of Acne Scars: 2022 International consensus recommendations. Lasers Surg Med. 2022 Jan;54(1):10–26. [CrossRef]

- Miao L, Ma Y, Liu Z, Ruan H, Yuan B. Modern techniques in addressing facial acne scars: A thorough analysis. Skin Research and Technology. 2024;30(2):e13573. [CrossRef]

- Laubach HJ, Tannous Z, Anderson RR, Manstein D. Skin responses to fractional photothermolysis. Lasers Surg Med. 2006 Feb;38(2):142–9. [CrossRef]

- Hantash BM, Mahmood MB. Fractional photothermolysis: a novel aesthetic laser surgery modality. Dermatol Surg. 2007 May;33(5):525–34. [CrossRef]

- Arsiwala SZ, Desai SR. Fractional Carbon Dioxide Laser: Optimizing Treatment Outcomes for Pigmented Atrophic Acne Scars in Skin of Color. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2019;12(2):85–94. [CrossRef]

- Dai R, Cao Y, Su Y, Cai S. Comparison of 1064-nm Nd:YAG picosecond laser using fractional micro-lens array vs. ablative fractional 2940-nm Er:YAG laser for the treatment of atrophic acne scar in Asians: a 20-week prospective, randomized, split-face, controlled pilot study. Front Med. 2023 Nov 16;10:1248831. [CrossRef]

- Ding Z, Pan Z, Tang Y, Wang S, Hua H, Hou Z, et al. Effectiveness and safety of the modified multiple mode procedures versus traditional multiple mode procedures on treating facial atrophic acne scars: a propensity score matching retrospective cohort study. Lasers Med Sci. 2024 Oct 19;39(1):260. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Z, Fei Y, Chen X, Lu W, Chen J. Comparison of a Fractional Microplasma Radio Frequency Technology and Carbon Dioxide Fractional Laser for the Treatment of Atrophic Acne Scars: A Randomized Split-Face Clinical Study. Dermatologic Surgery. 2013 Apr;39(4):559. [CrossRef]

- Yuan XH, Zhong SX, Li SS. Comparison Study of Fractional Carbon Dioxide Laser Resurfacing Using Different Fluences and Densities for Acne Scars in Asians: A Randomized Split-Face Trial. Dermatologic Surgery. 2014 May;40(5):545–52. [CrossRef]

- Jennings T, Duffy R, McLarney M, Renzi M, Heymann WR, Decker A, et al. Acne scarring-pathophysiology, diagnosis, prevention and education: Part I. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024 Jun;90(6):1123–34.

- Schultz GS, Wysocki A. Interactions between extracellular matrix and growth factors in wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2009;17(2):153–62. [CrossRef]

- Mu YZ, Jiang L, Yang H. The efficacy of fractional ablative carbon dioxide laser combined with other therapies in acne scars. Dermatol Ther. 2019 Nov;32(6):e13084. [CrossRef]

- Varga J, Rosenbloom J, Jimenez SA. Transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) causes a persistent increase in steady-state amounts of type I and type III collagen and fibronectin mRNAs in normal human dermal fibroblasts. Biochemical Journal. 1987 Nov 1;247(3):597–604. [CrossRef]

- Creely JJ, DiMari SJ, Howe AM, Haralson MA. Effects of transforming growth factor-beta on collagen synthesis by normal rat kidney epithelial cells. Am J Pathol. 1992 Jan;140(1):45–55.

- Carniol PJ, Hamilton MM, Carniol ET. Current Status of Fractional Laser Resurfacing. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2015;17(5):360–6. [CrossRef]

- Nowak KC, McCormack M, Koch RJ. The effect of superpulsed carbon dioxide laser energy on keloid and normal dermal fibroblast secretion of growth factors: a serum-free study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000 May;105(6):2039–48. [CrossRef]

- Tretti Clementoni M, Galimberti M, Tourlaki A, Catenacci M, Lavagno R, Bencini PL. Random fractional ultrapulsed CO2 resurfacing of photodamaged facial skin: long-term evaluation. Lasers Med Sci. 2013 Feb;28(2):643–50. [CrossRef]

- Clementoni MT, Lavagno R, Munavalli G. A new multi-modal fractional ablative CO2 laser for wrinkle reduction and skin resurfacing. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2012 Dec;14(6):244–52. [CrossRef]

- Prignano F, Campolmi P, Bonan P, Ricceri F, Cannarozzo G, Troiano M, et al. Fractional CO2 laser: a novel therapeutic device upon photobiomodulation of tissue remodeling and cytokine pathway of tissue repair. Dermatol Ther. 2009 Nov;22 Suppl 1:S8-15. [CrossRef]

- Li B, Ren K, Yin X, She H, Liu H, Zhou B. Efficacy and adverse reactions of fractional CO2 laser for atrophic acne scars and related clinical factors: A retrospective study on 121 patients. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022 May;21(5):1989–97. [CrossRef]

- Chan NPY, Ho SGY, Yeung CK, Shek SYN, Chan HH. Fractional ablative carbon dioxide laser resurfacing for skin rejuvenation and acne scars in Asians. Lasers Surg Med. 2010 Nov;42(9):615–23. [CrossRef]

- Majid I, Imran S. Fractional CO2 Laser Resurfacing as Monotherapy in the Treatment of Atrophic Facial Acne Scars. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2014 Apr;7(2):87–92. [CrossRef]

- Chapas AM, Brightman L, Sukal S, Hale E, Daniel D, Bernstein LJ, et al. Successful treatment of acneiform scarring with CO2 ablative fractional resurfacing. Lasers Surg Med. 2008 Aug;40(6):381–6. [CrossRef]

- Qian H, Lu Z, Ding H, Yan S, Xiang L, Gold MH. Treatment of acne scarring with fractional CO 2 laser. Journal of Cosmetic and Laser Therapy. 2012 Aug;87(6):162–5.

- Reinholz M, Schwaiger H, Heppt M, Poetschke J, Tietze J, Epple A, et al. Comparison of Two Kinds of Lasers in the Treatment of Acne Scars. Facial plast Surg. 2015 Nov 18;31(05):523–31. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Xu F, Lin H, Ma Y, Hu Y, Meng Q, et al. Efficacy of fractional CO2 laser therapy combined with hyaluronic acid dressing for treating facial atrophic acne scars: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Lasers Med Sci. 2023 Sep 19;38(1):214. [CrossRef]

- Galal O, Tawfik AA, Abdalla N, Soliman M. Fractional CO2 laser versus combined platelet-rich plasma and fractional CO2 laser in treatment of acne scars: Image analysis system evaluation. J of Cosmetic Dermatology. 2019 Dec;18(6):1665–71. [CrossRef]

- Belletti S, Pennati BM, Madeddu F. A sequential CO2 and 1540 nm laser for the treatment of neck skin laxity. Skin Research and Technology. 2023 Sep 18;29(9):e13469. [CrossRef]

- Mezzana P, Valeriani M, Valeriani R. Combined fractional resurfacing (10600 nm/1540 nm): Tridimensional imaging evaluation of a new device for skin rejuvenation. Journal of Cosmetic and Laser Therapy. 2016 Oct 2;18(7):397–402. [CrossRef]

- Fiorentini F, Fusco I. Synergistic Sequential Emission of Fractional 1540 nm and 10 600 Lasers for Abdominal Postsurgical Scar Management: A Clinical Case Report. Am J Case Rep [Internet]. 2022 Dec 20 [cited 2023 May 14];24. Available from: https://www.amjcaserep.com/abstract/index/idArt/938607. [CrossRef]

- Kim S, Cho KH. Clinical Trial of Dual Treatment with an Ablative Fractional Laser and a Nonablative Laser for the Treatment of Acne Scars in Asian Patients. Dermatol Surg. 2009 Jul;35(7):1089. [CrossRef]

- Belletti S, Madeddu F, Amoruso GF, Provenzano E, Nisticò SP, Fusco I, et al. An Innovative Dual-Wavelength Laser Technique for Atrophic Acne Scar Management: A Pilot Study. Medicina. 2023 Nov 15;59(11):2012. [CrossRef]

- García PN, Andrino RL. Resurfacing of atrophic facial acne scars with a multimodality CO2 and 1570 nm laser system. Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology. 2024;23(S1):13–8. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).