1. Introduction

A chronic infectious disease caused by Leishmania infantum, visceral leishmaniasis (VL), also referred to as kala-azar, is the second largest cause of death of humans in the globe next to malaria [

1]. An estimated 12 million individuals are affected with the disease worldwide in 98 endemic countries, and an additional 350 million are at risk of contracting it [

2]. The vector-borne disease, VL, is transmitted through the bite of a very small flying insect female adult sand-fly. Warm and humid weather is suitable for the sand flies to flourish in[

3]. Different interventions have been implemented in various endemic areas of the world to control the transmission of VL. These include personal protection through the use of clothes that cover as much of the body as possible, avoiding being outside between dusk and dawn, utilizing insecticide-treated bed nets, use of indoor and outdoor spraying of insecticides, using window and door screens to prevent sand flies bites [

4,

5] together with WHO-recommended therapies such as liposomal amphotericin B, Miltefosine, Pentavalent antimonials, and Paromomycin [

6]. However, due to the costs of medicines and the administration route, the VL control strategy continues to be challenging. Mathematical and epidemiological models that consider different intervention mechanisms have been developed to minimize such challenges.

These models are indispensable tools for understanding, predicting, and controlling the spread of infectious diseases. They provide critical insights that inform policy decisions, optimize resource allocation, support emergency response efforts, and drive innovation in disease control strategies. Hence, numerous modeling studies of VL have been conducted to understand the impact of different intervention strategies and to describe and predict how the disease spreads (see [

1,

7,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16] and the reference therein). While the mathematical models of VL are valuable for understanding the disease dynamics, they do not explicitly optimize control strategies. Optimal control models provide more rigorous and efficient tools for designing and implementing effective disease control strategies. However, some studies have been conducted to investigate the optimal control strategies for controlling the spread of VL.

For example, Pantha et al. [

20] developed a mathematical model for VL transmission dynamics involving human, canine, and vector populations. The goal was to identify effective control measures for reducing VL burden and guiding public health interventions in endemic areas. They evaluated three control measures using optimal control theory: personal protection, insecticide spraying, and culling infected canine reservoirs. Simulation results showed that combining these interventions could eliminate VL from the region. Zhao et al. [

19] developed a mathematical model for zoonotic visceral leishmaniasis (ZVL) in Brazil using a modified SEIR-type approach, focusing on dogs as reservoirs. They classified the dog population into susceptible, exposed, infected, and recovered categories and the human and sand fly populations into similar compartments. Mathematical analysis indicated the possibility of backward bifurcation. They introduced three time-dependent controls using optimal control theory: dog vaccination, sand fly control with insecticides, and personal human protection. Numerical simulations showed that vector control via insecticide spraying was the most effective strategy, while culling dogs was ineffective. However, the study lacked validation with real data and did not include cost-effectiveness analysis.

Ghosh et al. [

21] developed a compartmental VL model considering human, animal, sand fly, and non-adult sand fly populations. The human population was divided into six classes, including asymptomatic, symptomatic, and PKDL-infected individuals. Global sensitivity analysis identified key parameters affecting the cost function, and the model was validated with 2013 weekly VL incidence data from South Sudan. The model used three time-dependent controls: treatment of infected individuals, non-adult stage vector control, and adult stage vector control. Cost-effectiveness analysis showed that combining treatment and non-adult stage vector control was the most cost-effective strategy. Augusto et al. [

9] developed a deterministic model for malaria-VL co-infection to understand its dynamics and find cost-effective control strategies. Using the basic model by ELmojtaba [

11], they introduced four time-dependent controls: personal human protection, insecticide-treated bed-nets, culling of infected reservoir animals, and insecticides. Their results show that combining personal protection, indoor residual spraying, and reservoir culling is the most cost-effective approach for controlling malaria-VL co-infection. In several endemic regions of the world, the results of numerous research have demonstrated that males are more severely impacted by VL than females. The observed gender disparity in visceral leishmaniasis is likely influenced by a combination of behavioral, biological, socioeconomic, and environmental factors. Conducting a sex-structured disease dynamics model for visceral leishmaniasis allows for a more comprehensive understanding of transmission dynamics. To address this issue, a sex-structured VL disease transmission model was conducted by Awoke et al. [

10]. However, the research work did not include optimal control and cost-effectiveness analysis. The optimal control plays a crucial role in disease dynamics models. It offers insightful information about the possible effects of various intervention strategies (e.g., insecticide-treated bed nets, vector control, and medical treatment), and supports long-term planning goals by taking the sustainability and feasibility of intervention strategies over extended time horizons into account. Furthermore, it helps public health decision-makers prioritize disease control strategies during resource allocation and maximizes the use of limited resources (for example vaccines, drugs, and medical staff). Since VL treatments are very expensive, it is very important to study sex-structured VL models that incorporate disease control mechanisms and propose cost-effective intervention strategies.

Managing VL poses a financial burden on local communities in countries where the disease is prevalent, perpetuating a cycle of illness and poverty. Strategic allocation of public funds towards control programs could alleviate this burden by reducing the prevalence of VL [

22]. To this end, employing dynamic models that incorporate an optimal control theory is essential for assessing intervention strategies and devising an economically efficient policy to contain the disease. The motivation for this research arises from the considerable public health challenge posed by VL, a disease that predominantly affects males. While many VL models, including those incorporating animal reservoirs and optimal control strategies, have been studied, there remains a gap in analyzing the cost-effectiveness of interventions in sex-structured populations. Building on the VL model developed by Awoke et al. [

10], this article introduces four time-dependent control interventions: the use of insecticide-treated bed nets, vector control through residual spraying and environmental management, medical treatment, and infected animal culling. To the best of the knowledge of the authors, no study has yet explored the cost-effectiveness of such a comprehensive, sex-structured approach to VL control. To evaluate whether sex differences influence optimal control strategies, we incorporated parameters for the use of insecticide-treated bed nets and medical treatment. By addressing this gap, this research will provide crucial insights that can directly benefit both local communities and policymakers. A thorough cost-effectiveness analysis will identify the most cost-effective strategies for reducing VL transmission, helping to optimize limited resources in low-income regions where the disease is prevalent. This research will also equip policymakers with evidence-based recommendations, allowing them to prioritize interventions that offer the greatest health benefits for the lowest cost, ultimately contributing to more sustainable and effective public health strategies. Hence, our study aims to integrate effective preventive and control measures for visceral leishmaniasis (VL) into the existing sex-structured model. We intend to assess the cost-effectiveness of these interventions and propose an optimal control strategy to enhance decision-making processes.

The rest of the manuscript is organized as follows:

Section 2, presents the model formulation, control strategies and analysis of key properties, including positivity, boundedness and the basic reproduction number with controls. This sections also introduces the optimal control problem and its characterization.

Section 3 presents results and discussion. Conclusions are given in

Section 4.

2. Methods

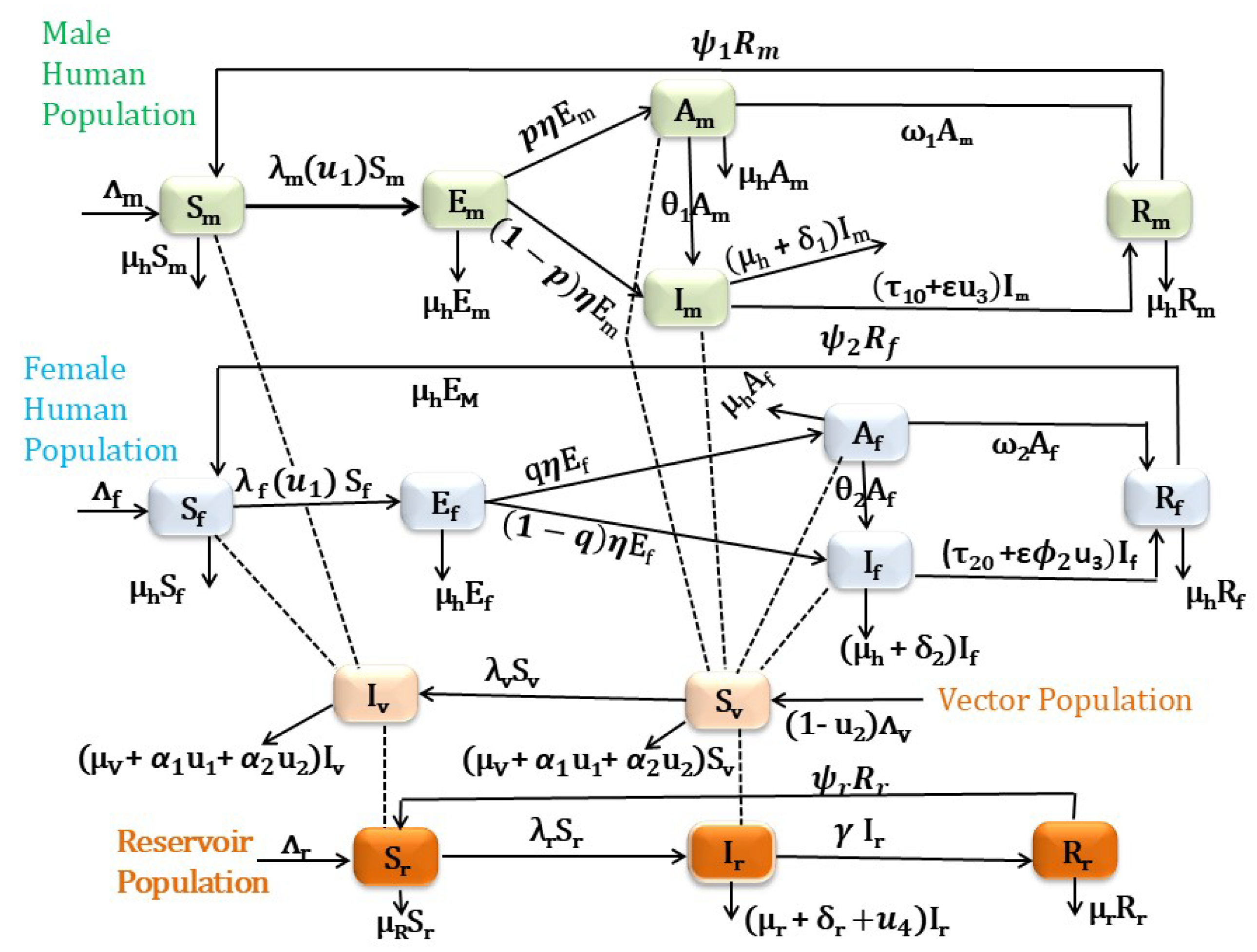

Controlling VL remains challenging in different endemic areas of the world for different reasons, such as the complexity of the transmission, lack of effective vaccine, cost of treatment, and socioeconomic factors. In addition, the disease mainly affects the male human population. Hence, there is a need to develop comprehensive cost-effective control strategies that will address these challenges. By optimizing control measures across different gender groups and considering trade-offs between intervention options, optimal control helps maximize the impact of interventions and improve disease control efforts. The most powerful VL disease transmission control mechanisms are the use of insecticide-treated bed-nets and medical treatment of infected humans together with vector control strategies. In this work, we want to consider these interventions as time-dependent control function and incorporate them into the sex-structured VL model proposed in [

10]. The total human population is initially divided into male and female sub-populations, with each further classified into five compartments: susceptible males and females (

,

), exposed males and females (

,

), asymptomatic males and females (

,

), actively infected males and females (

,

), and recovered males and females (

,

). The sand fly population is split into susceptible (

) and infected (

) groups, while the reservoir population is categorized into susceptible (

), infected (

), and recovered (

) groups. The description of the model parameters are indicated in

Table 1 and for the detail please refer to [

10].

As described in [

23,

33], the possible interventions for visceral leishmaniasis can be categorized as: applying preventive mechanisms through the use of Insecticide Treated Bed Nets (ITNs), vector control with the use of insecticides, treatment of infected individuals and animal culling. The practical applications of these mechanisms, and assumptions used in this work are described below.

-

Preventive mechanisms through the use of ITNs

The WHO recommended VL preventive strategies include the use of insecticide treated sand fly nets [

24]. In order to curb the spread of VL in a study by [

25], the breakthrough in the reduction of the spread of VL was achieved after the introduction of ITNs. Due to its practical applicability, we are considering the use of ITNs as one of the control strategies. Using ITNs reduces the probability of humans being bitten. Furthermore, since the nets are treated with insecticides, they kill vectors. Therefore, we used the following two assumptions formulated in [

9,

28].

- a)

The mathematical expression for the use of ITNs in order to reduce human-vector contact rate is described by the relation

where

and

are the maximum and minimum possible number of bites a host population receives per week, respectively. Since most sandfly biting activity occurs during the early evening before most people go to sleep and other limitations of the use of INTs, the maximum control effort is assumed to be

. Hence,

. Applying different interventions, such as treated bed nets and medication, to different sexes (male and female human populations) in the control of VL might raise ethical considerations. However, due to biological and behavioral differences as well as the need to optimize resource allocation, considering differential interventions for both sexes might trigger an ethical question. Males and females often have different exposure risks to the sand fly. In VL-endemic areas, men may work outdoors in high-risk settings where they are more exposed to sand fly bites, while women may spend more time indoors. Tailoring interventions to these behavioral patterns, such as providing stronger protection for men who are more exposed outdoors, may be a targeted and effective strategy for disease control. In addition to these, the availability of limited resources in public health programs often necessitates prioritizing interventions for populations at greater risk. Since data reveals that men are at higher risk of contracting the disease than women, focusing certain interventions like availing treated bed nets or medications on that group can maximize the impact of disease control efforts. Due to these reasons we assumed that the intervention rates for female is reduced by a proportion

for the use of bed nets and by

for the use of medical treatment as compared to that of the male counterparts, where

. In this work, the expression for the use of ITNs is based on the concept formulated in Asfaw et al.[

28]. Therefore, the forces of infection for the male human population (

), female human population (

), and vector population (

) are re-written as follows:

where

. Our model is based on the assumption that vector bites are distributed in fixed proportions among males, females, and reservoir hosts. However, in real-world scenarios, the use of bed nets by a subset of the human population could alter this distribution. Specifically, when some individuals are protected by bed nets, vectors may shift their biting behavior toward unprotected groups, potentially leading to increased exposure among unprotected groups such as reservoir hosts. We acknowledge that this adaptive biting behavior is not captured in our current model.

- b)

Since bed nets are treated with insecticides, they have the capacity of killing vectors that landed on the net. Hence, if the natural death rate of vectors is

, ITNs usage increases the sand fly death rate by

. This is mathematically represented by

where

represents the capability of insecticide-treated bed-nets to kill sand flies and

represents the death rate of adult sand flies due to insecticide-treated bed nets.

-

Vector control: The incidence rate of VL is increasing in some endemic regions of the world, including Kenya, Ethiopia, and Sudan [

32], as a result of the serious side effects of the current VL medications and the lack of an effective vaccination. Programs to eradicate leishmaniasis, therefore, mainly rely on vector control using insecticides and environmental management. The goal of environmental management is to eliminate or make places undesirable for sand flies to nest and rest, as well as to kill the pre-adult stage of vectors. Tree stump clearance, soil and crack filling, routine cleaning of the per-domicile area and animal shelters, and trash removal are common vector control methods through environmental management [

31]. Additionally, the most effective method of controlling sand flies is the use of chemical interventions such as indoor residual spraying (IRS), which is associated with a decrease in the lifespan of sand flies, leading to a subsequent decline in their population [

14,

26,

27]. By reducing the lifespan of sand flies, the vector is less likely to survive long enough to acquire infection and to infect a host again. As the death rate of vectors increases, they spend less time in an infected state. Taking this into account, we incorporate a time-dependent control

that represent an additional vector control effort through the use of environmental management and indoor residual spraying into the VL model. If the current natural mortality rate of vectors is

, then the number of additional deaths of non-adult sand flies after the use of vector control intervention will be

, where

represents the effectiveness of insecticide spraying in killing sand flies. This implies that

of Eq.(

4) will be updated by an additional term

. Such that

Furthermore, the recruitment rate of vectors () will decrease by as the application of insecticides is expected to destroy the breeding cites and kills the non-adult stage sand flies. Hence, is updated by , where . Note here that and must satisfy the condition that

Treating infected individuals: Treatment is an important method to recover from the disease. Treatment has an effective role in preventing and controlling the spreading of the disease. Proper and timely treatment can reduce the total prevalence of the disease. However, treatment alone will not be enough to truly halt the transmission of VL [

29,

30]. The efficacy of VL drugs varies from one endemic area to another. We assume that the efficacy of VL drug is

. If

and

are the recovery rates of male and female human host, then the mathematical expression for the formulation of controls with an additional treatment effort (

) is given by:

and

. Where

represents the natural recovery rate of the male human host,

represents the natural recovery of female human hosts, and

is a modification parameter, as stated before, with

for every time

.

Culling infected animals: Dogs are the most important reservoirs of VL infection in domestic settings, while other animals can serve as a source of VL infection [

33]. As a result, it is believed that having infected dogs increases the risk of VL in people in endemic areas. Culling leishmania-seropositive reservoirs such as dogs has been recommended as a control measure in many VL endemic countries [

34]. It is indicated in [

20] and [

9] that, culling of infected animals is a cost effective VL control strategy together with other interventions. Hence, we consider culling of infected dogs as one of the control strategy. Given

and

, which represent the natural and disease-induced mortality rates of infected dogs,

provides the mathematical expression for the rate at which infected dogs diminish as a result of further culling effort

, where

for every time

.

In general, by considering all these, we incorporate the above four VL intervention strategies in the VL model formulated and analyzed in [

10]. Since most governments cannot implement intervention programs indefinitely, we considered the optimal control problem with a fixed terminal time

, where

T is the final time. The corresponding system of differential equations can be written as in Eq.(

6) once these control parameters have been applied to the model system.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram for VL compartmental model in which the human population is classified based on their sex.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram for VL compartmental model in which the human population is classified based on their sex.

where

and

. with

,

,

and

are as indicated in equations (

2) and (

3).

,

,

, and

. The model system (

6) is appended with initial conditions:

2.1. Model Analysis

2.1.1. Boundedness and Positivity of Solutions with Constant Control Parameters

For the VL model system (

6) to be epidemiologically meaningful, it is important to analyze that all its state variables are non-negative for all time and the region

defined in Theorem 1 is positively invariant.

Theorem 1.

The VL model system (6) is a dynamical system on the biologically feasible region Ω

. Where,

Proof. The proof of Theorem 1 proceeds in a similar manner to the proof of Theorem 1 in Awoke et al. [

10]. For brevity, we omit the details here, as they follow similar reasonings and steps presented in [

10]. □

2.1.2. Disease Free Equilibrium Point (DFE)

The model system (

6) has a disease-free equilibrium (DFE) given by

2.1.3. Basic Reproduction Number with Constant Controls

As indicated in [

35], the basic reproduction number (

) is defined as the average number of secondary infections that occur when one infective is introduced into a completely susceptible host population.

We calculate the basic reproduction number,

of the model system (

6), using the next generation matrix approach proposed by [

35]. To apply this method, we define

as the column-vector of rates of the appearance of new infections in each compartment,

is the column-vector of rates of transfer of individuals into the particular compartment; and

is the column-vector of rates of transfer of individuals out of the particular compartment. Then,

for each compartment, where,

. Considering the system (

6) has eight infected classes, namely

and

we obtain

Evaluating the Jacobian of (

9) at

gives

where

Similarly, the Jacobian of (

10) with respect to

and

at

gives

where

,

,

,

,

,

,

.

The basic reproduction number (

) is then given by the spectral radius of the next generation matrix,

and it is found to be

where

Remark 1. The formula for basic reproduction number with control has three parts and is epidemiologically interpreted as follows.

-

1.

The quantity is associated with the contribution of infected reservoirs,

-

2.

The quantity is associated with the contribution of infected male humans,

-

3.

The quantity is associated with the contribution of infected female humans in the spread of the disease at its initial stage.

Theorem 2. The Disease free equilibrium (DFE) of the model system (6) with control is locally asymptotically stable whenever and unstable if .

Proof. This is an immediate consequence of Theorem 2 in [

35]. □

The epidemiological implication of Theorem 2 is that VL can be effectively controlled in the host and reservoir populations (humans and animal reservoirs) if the initial number of infected humans, reservoirs and vectors are small enough (i.e., in the basin of attraction of the non-trivial disease-free equilibrium, ).

To understand how modifications in controls influence the basic reproduction number (

), we perform partial differentiation of

with respect to each control (

,

,

and

), by keeping the other parameters as a constant:

where

The rate of change of

with respect to each controls (

,

,

and

) are negative. This shows that increasing the values of the controls decreases the value of the basic reproduction number (

). Therefore, employing ITNs for male and female human populations, medical treatment for infected male and infected female human populations, vector control, and removing infected animals will decrease the average number of new infections and, hence, the prevalence of the disease. We can observe from

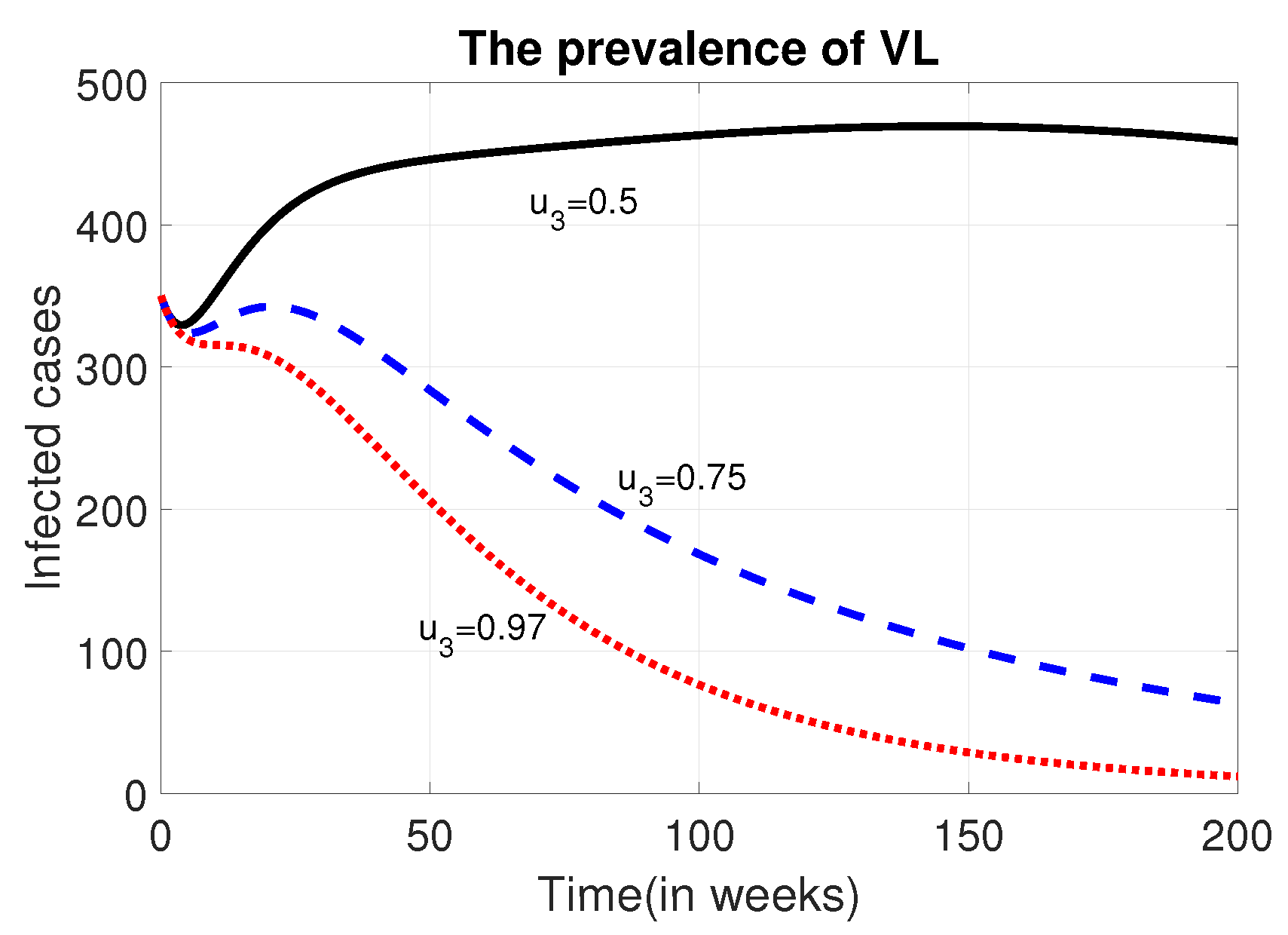

Figure 2 that the use of additional effective medical treatment decreases the disease’s prevalence.

2.2. Optimal Control

2.2.1. Definition of Cost Function

We want to find the controls that minimize the total number of infected human populations and the cost of controls. This implies that finding optimal values of

,

,

and

that minimize the cost function

where,

subject to the differential equations (

6), where T is the final time, the constants

,

,

,

,

,

,

and

are values that will balance the units of measurement and also may indicate the importance of one type of intervention over the other.

,

represent the cost on the population of actively infected male and female individuals as well as

and

represent the cost on the population of asymptomatically infected male and female individuals. Moreover, the term

and

represent the individual treatment costs of male and female human host that receive treatment respectively,

represent the cost of implementing the control on ITNs,

represents the cost of vector control,

represent community level treatment cost related to the preparation and facility set-up for treatment and

represent the cost of removing infected reservoir animals. While the quadratic form of the cost function is mathematically advantageous, it also has practical biological and economic significance. The quadratic dependence on control efforts reflects the fact that as the intensity of interventions increases, costs tend to rise disproportionately. Several factors contribute to this phenomenon. For example, initial interventions, such as moderate dog culling or bed net distribution, might be relatively affordable. However, achieving broader coverage often requires significantly more resources, leading to higher logistical and operational expenses. Additionally, while culling a small number of infected reservoir animals may be manageable, scaling up this effort could encounter increased community resistance, further elevating costs. The quadratic formulation of control costs is widely used in objective functions of optimal control problems, offering a familiar and well-understood approach within the field. We seek to find optimal controls

,

,

and

such that

where the admissible set

Considering the objective function in (

12), we have the optimal control problem:

subject to the system in Eq. (

6) and bounded controls.

2.2.2. Existence and Characterization of Optimal Control Solution

Examining the conditions that can assure the existence of a solution to our optimum control issue will be the first step. The following theorem shows the existence of the optimal control solution to the above optimal control problem [

36,

41].

Theorem 3. There exists an optimal control , and corresponding solution vector to the state initial value problem (6) that minimizes the objective function of (12) over the set of admissible controls .

Proof. The non-trivial requirements on the set of admissible controls

and on the set of end conditions are verified from Fleming & Rishel’s theorem [

36].

□

2.2.3. Characterization of Optimal Control Solution

To formulate the necessary conditions for optimality, we need to define the Hamiltonian function of the optimal control problem (

14). The Hamiltonian equation with marginal cost function, state variables and adjoint variables is given by

By using Pontryagin’s Maximum Principle [

36], we derive necessary conditions for the optimal controls and corresponding states. That is, it is now possible to determine the optimal control variables,

and

, from the necessary conditions. Now, the necessary conditions are given as follows.

-

Optimality Conditions: The minimization of the Hamiltonian H with respect to the control variables , is the first condition that we will examine from the Pontryagin’s Maximum principle. Since the cost function is convex, if the optimal control occurs in the interior region we must have for . Therefore

- (i)

for the control

we must have,

- (ii)

for the control

we must have,

- (iii)

for the control

we must have,

- (iv)

the control

we must have,

And therefore, the optimal controls on the given bounded intervals are given by

The adjoint (co-state) equations: According to the second condition of Pontryagin’s Maximum Principle, we need to have the optimal controls

for each

. As a result, we must compute and resolve the system,

The transversality conditions

Since the model functions exhibit convexity with respect to the control variables, and considering the predetermined boundedness of the state and adjoint (or co-state) functions, the resulting optimal solution is unique for short duration of time T [

42,

43,

44].

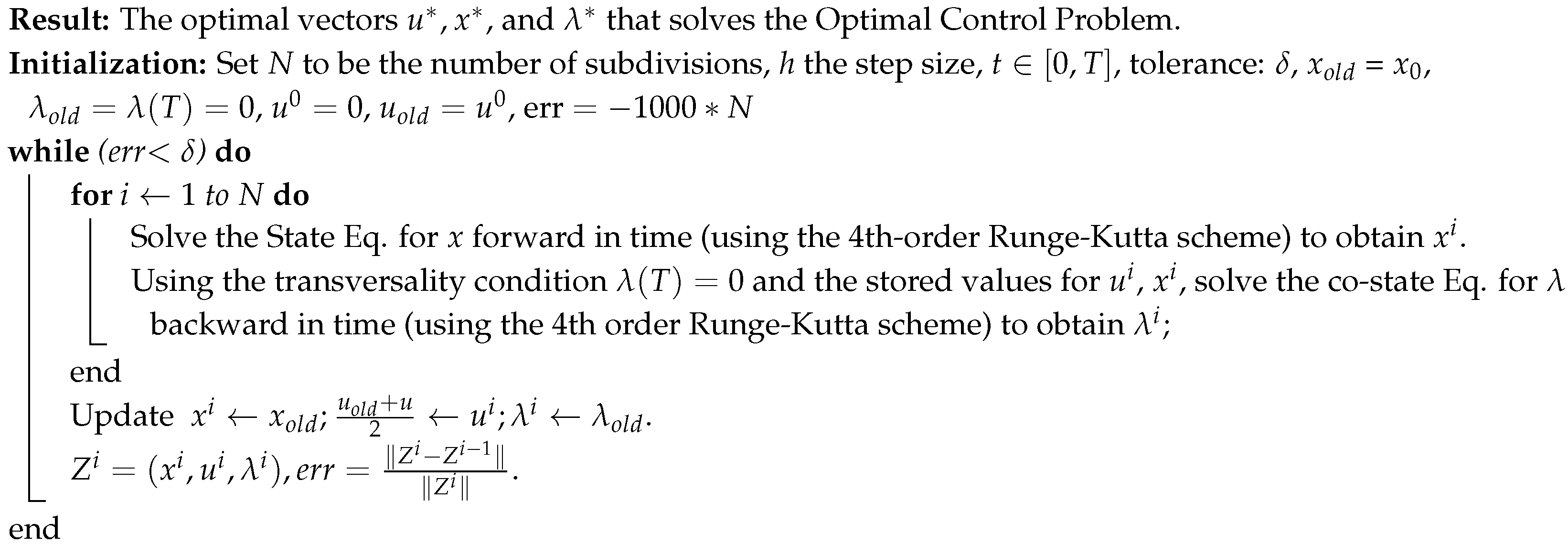

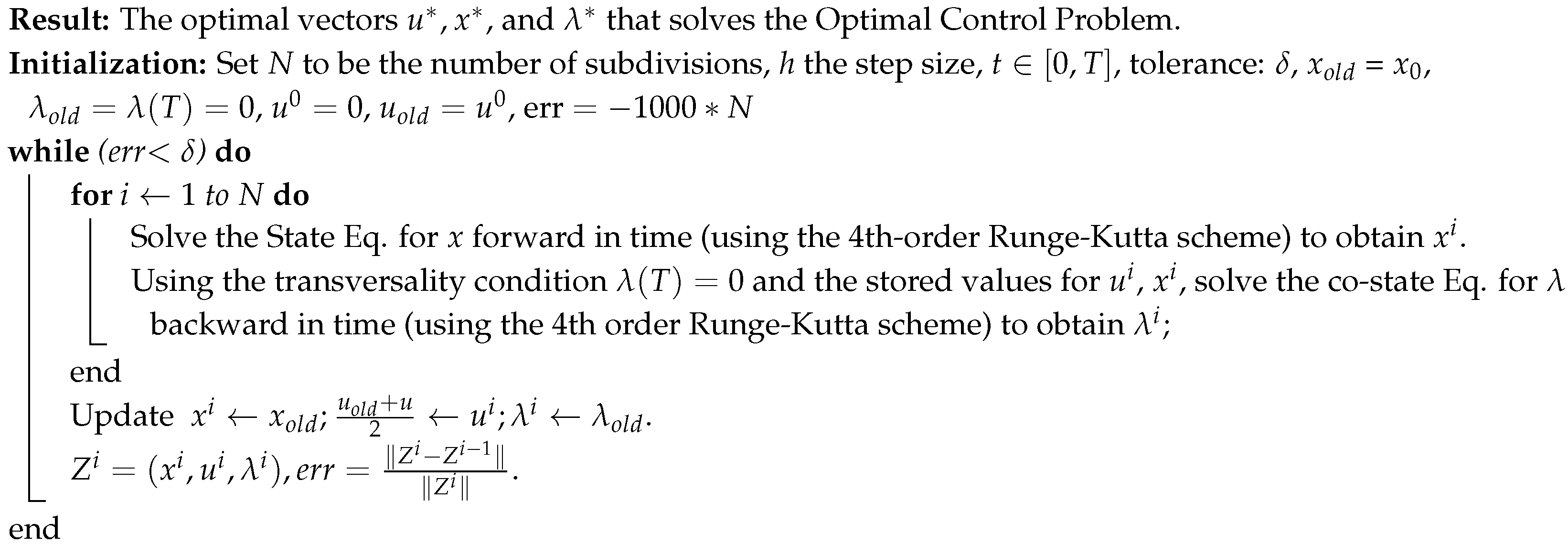

2.3. Numerical Methods

We numerically calculated optimal control strategies based on the iterative method used in [

45] in the interval [0,156] weeks or for three years. Given initial estimates for the controls and initial conditions for the states, the state differential equations (

6) are then solved forward in time using the

order Runge-Kutta method. According to the results of state values and the given final value in Eq. (

16), we solved adjoint values from the adjoint equations backward in time, using the fourth-order Runge-Kutta method. Both updates of state values and adjoint values were utilized to calculate optimal control strategies. The same process is repeated until the current state, adjoint, and control values converge sufficiently [

47]. All our numerical simulations are performed using the MATLAB software. The summary of the algorithm based on [

46] is written as follows:

|

Algorithm 1: Forward-Backward-Sweep Algorithm

|

|

It is challenging to pinpoint the precise cost of pharmaceutical therapy for VL due to a variety of factors, including geographical variations, shifts in medication prices, the nature of the health-care system, and indirect expenses. The majority of the total cost per patient is frequently attributed to prescription prices. However, other elements, including hospitalization, diagnostics, and supportive care, also play a role. Depending on the patient’s location and the availability of WHO drug subsidies, the most effective VL medication, amphotericin B, could cost

per treatment in many endemic counties [

49]. Therefore, in our simulation,

and

are used. The cost of culling an infected dog and its disposal varies based on the dog’s weight, the type of service, and the location of the facility. Considering these, we estimate the coefficient for the cost of dog culling to be

. Hence

is used. The cost of Insecticide-Treated Nets (ITNs) for controlling sand flies, particularly in VL endemic regions, is highly variable based on delivery systems, geography, and program scale. Since there is no pre-estimated cost for ITNs and environmental management as well as indoor residual spraying cost to control sand flies, we have assumed the total direct and indirect cost of those interventions for our numerical simulation to be

,

,

,

,

,

and

.

For numerical simulations, the initial population values are taken from the fitted values at the time of last data recorded in [

10]. These are

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

and

. The other model parameter values are as indicated in

Table 2.

3. Results and Discussion

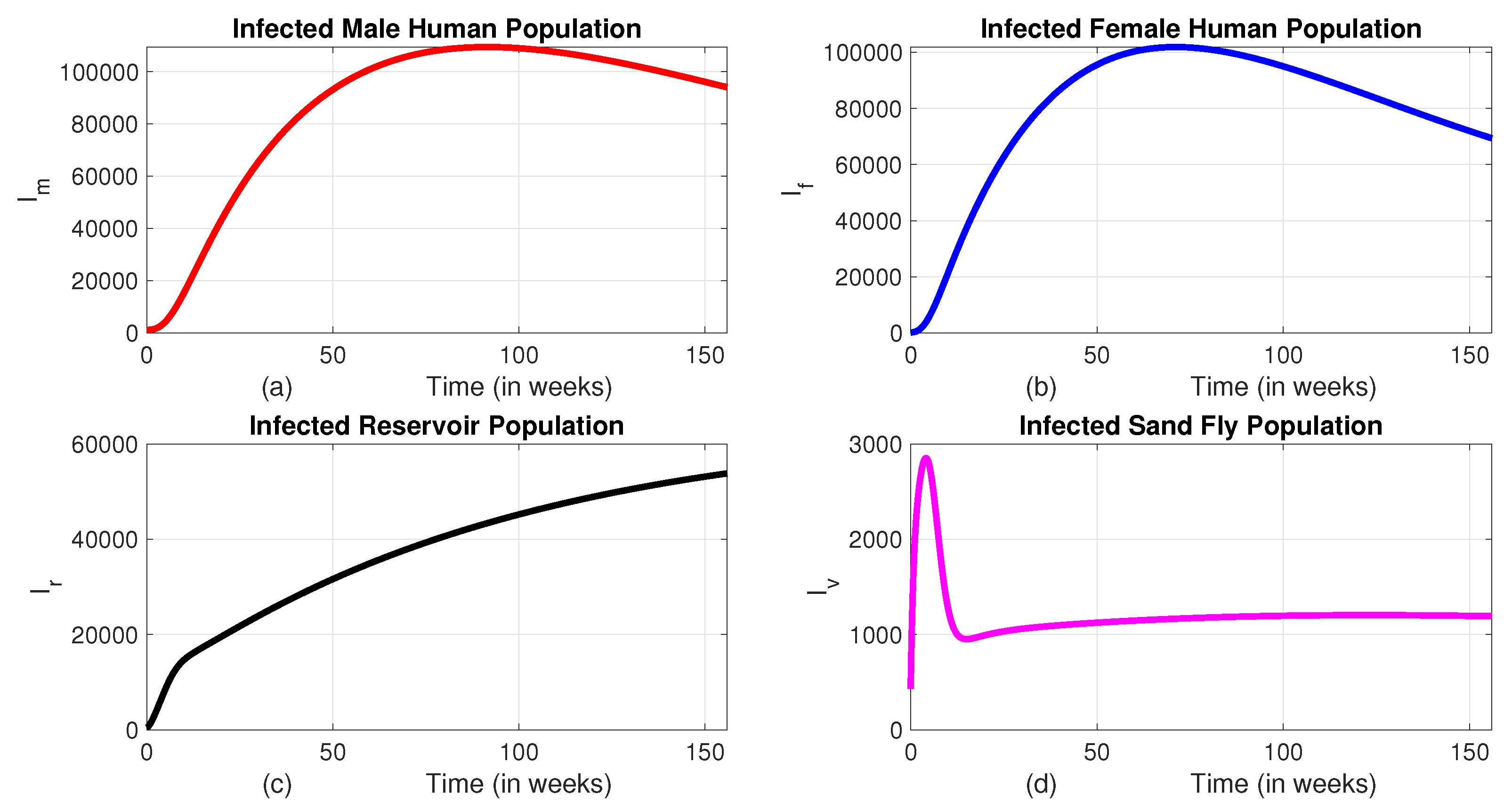

3.1. Various Interventions/Control Strategies

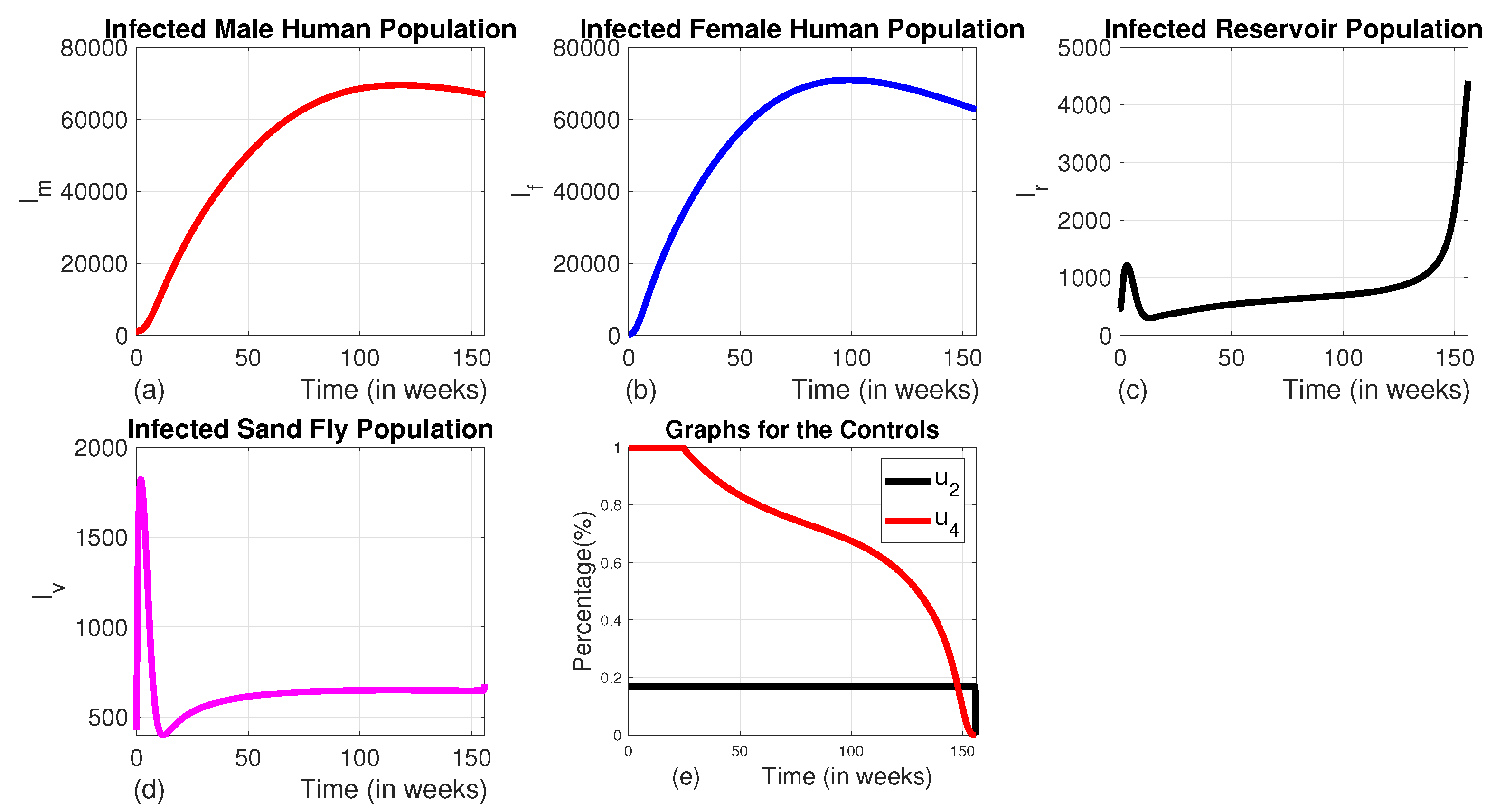

We have introduced different possible combinations of strategies in our model and numerically compared their effects on the total number of infected populations. The time profile of infected classes when no intervention is applied are indicated in

Figure 3.

We can observe from

Figure 3 that, in the absence of interventions, the disease continues to spread and remains persistent within the community. This persistence highlights the robustness of the transmission dynamics and the difficulty in achieving natural eradication. Without targeted measures, the disease remains endemic and may lead to long-term health and socio-economic impacts. Therefore, it becomes essential to implement a range of intervention strategies, such as insecticide-treated bed nets, vector control through indoor residual spraying, treatment programs, and screening and culling of infected reservoirs, to reduce disease prevalence significantly. In the following sections, we will see the impact of different interventions in reducing the number of infected populations.

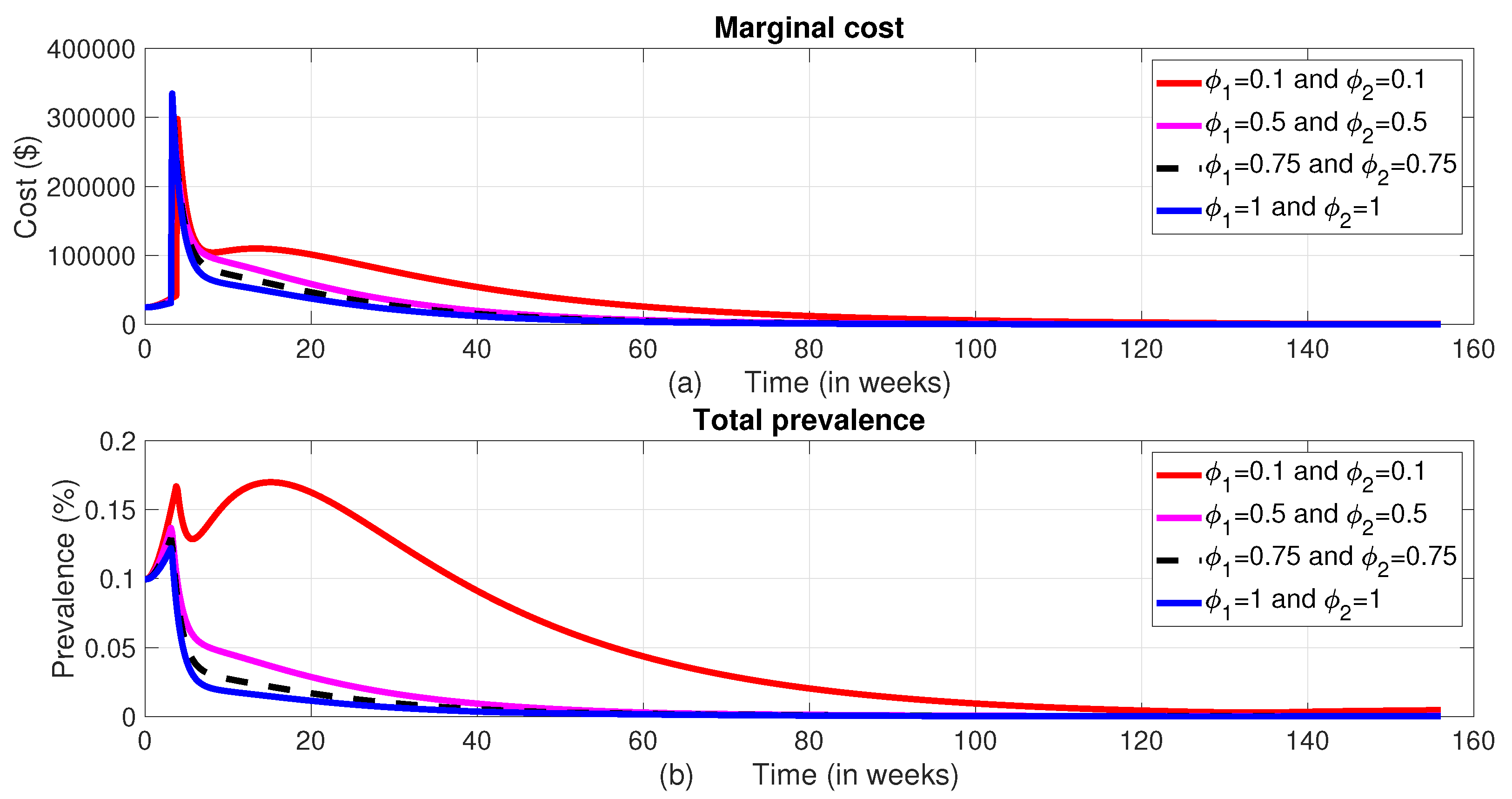

Despite the ethical concerns, we simulated the total prevalence and corresponding costs to assess the impact of applying control interventions at varying rates for both male and female humans. When the proportion of treatment and ITNs used for the female human population as compared to their male counterpart is set at

,

, or

, there is no significant difference in the total prevalence or intervention costs (see

Figure 4). However, when the proportion is reduced to 10%, a noticeable difference in prevalence is observed. Therefore, to optimize resource use and reduce prevalence, it is advisable to take this proportion into consideration.

We now analyse the effect of various possible combinations of intervention mechanisms, in reducing the burden of the disease. In each of these combinations, we assumed that only

of the controls

and

are implemented to the female humans. This is based on the information from

Figure 4.

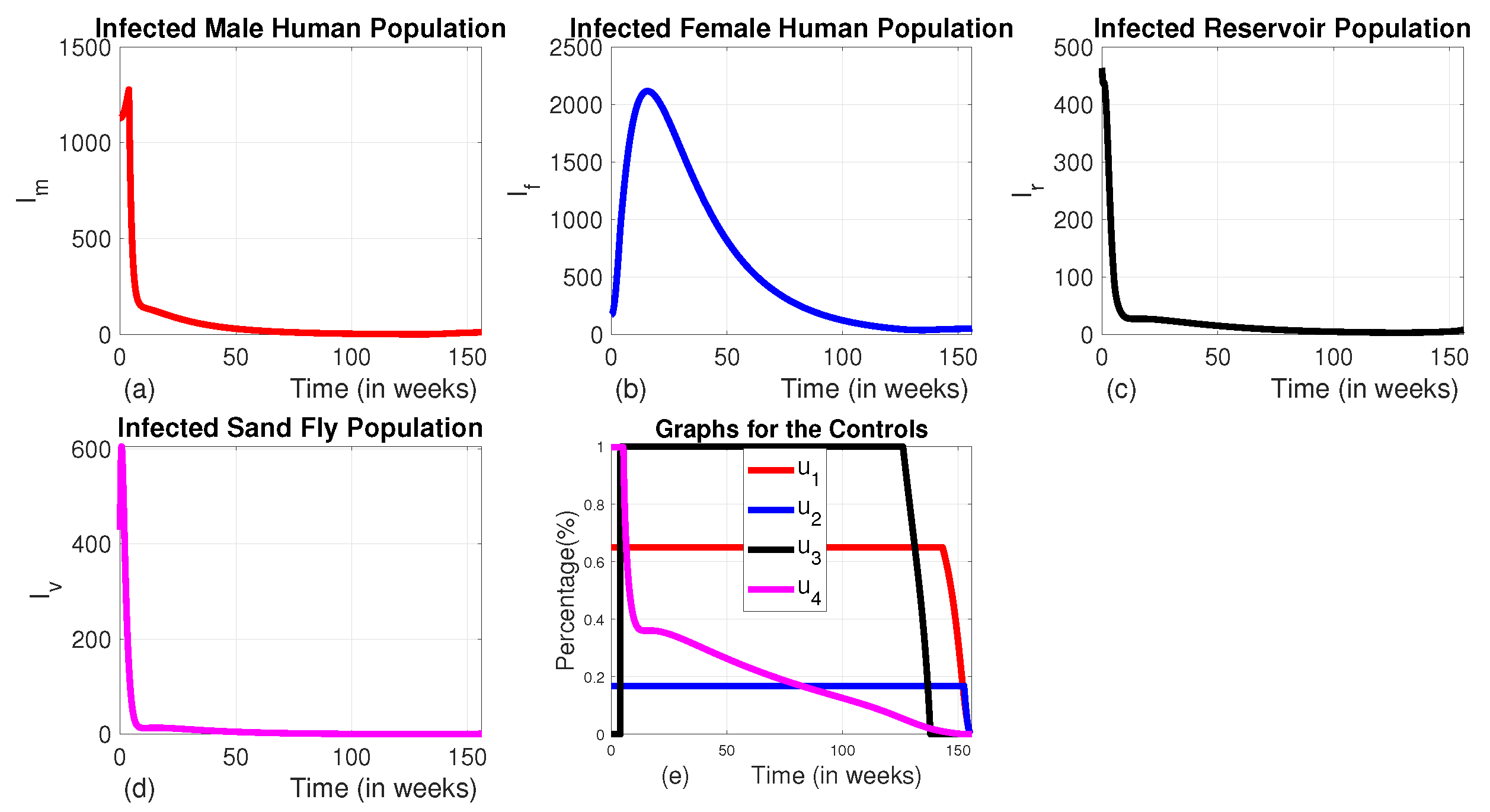

3.1.1. Strategy A (All Controls i.e., the Combination of the Use of Treated Bed-Nets, Vector Control, Treatment of Infected Individuals

and Culling Infected Reservoir Animals

In this approach, we applied all the four control variables,

,

,

and

, to optimize the objective function

J in Eq.(

12). When comparing strategy A to the scenario without any control measures, the number of infected male humans (

), the infected sand fly population (

), and the number of infected reservoirs (

) show an exponential decline (refer to

Figure 5 (a), (c) and (d) respectively). Whereas the number of infected female human population increases for the first about 16 weeks and goes down and becomes optimum at week 130 (

Figure 5 (b)). When analyzing the control profile (

Figure 5 (e)), it is clear that the first three controls (

,

and

) remain at their maximum levels (

) for approximately 126 weeks. In contrast, the fourth control (

) remains at the maximum level for the first five weeks and drops from its peak by

at the fifth week and gradually decreases to zero by the end of the intervention period.

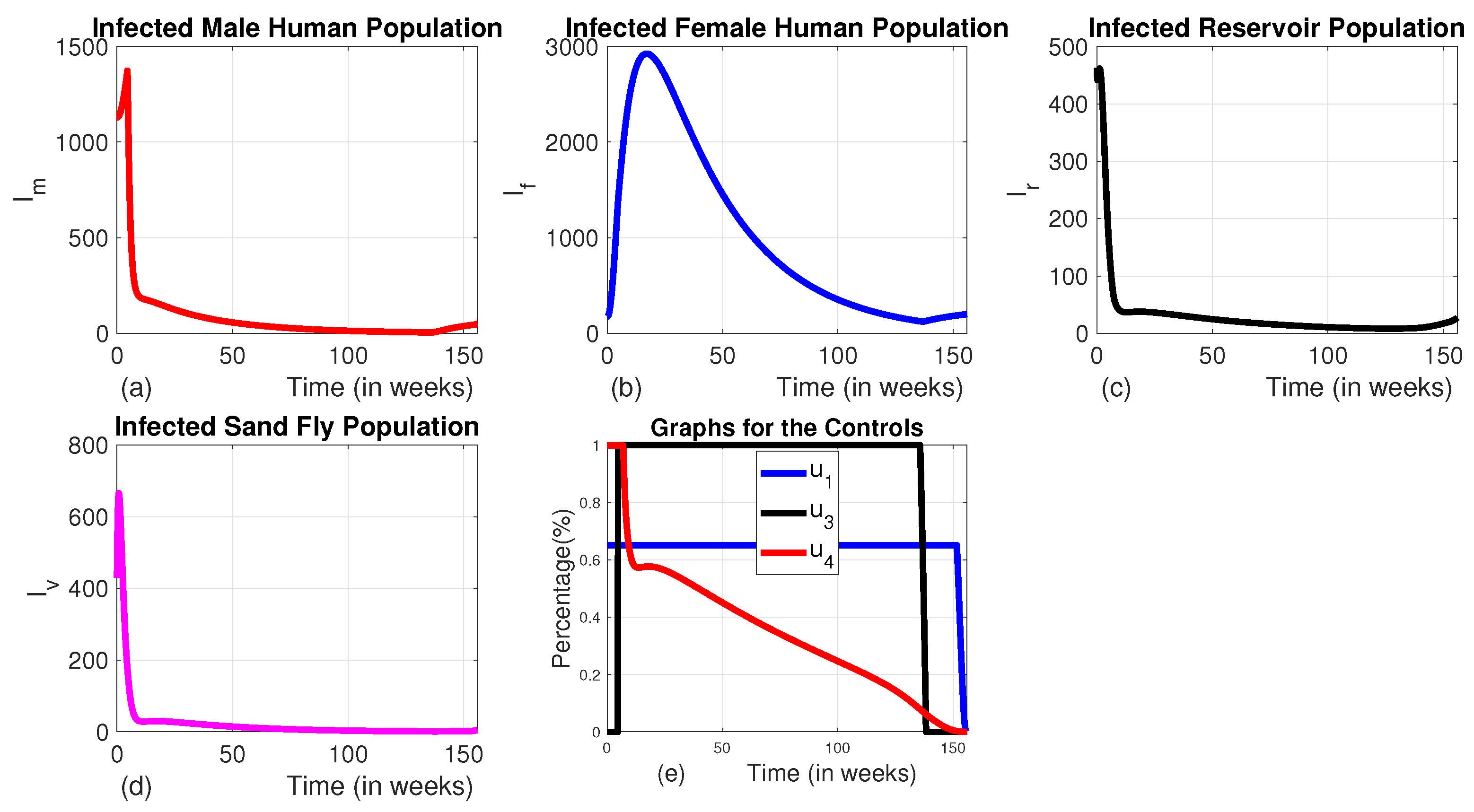

3.1.2. Strategy B (the Combination of the Use of Medical Treatment for Infected Individuals

and Animal Culling Without Using Insecticide-Treated Bed Nets and Vector Controls ( and )

In this strategy, we applied the combination of medical treatment(

) and culling infected animals (

) without the use of insecticide-treated bed-net (

) and vector controls (

). When comparing Strategy B to an uncontrolled scenario, it can be observed that the population of infected male humans increases during the first 8 weeks, then drops by 62.5% over the following about 4 weeks, then decreases slowly until 133 weeks. Then the number of infected male increases exponentially for the rest of the intervention period (

Figure 6 (a)). Similarly, the population of infected female humans initially rises for the first 24 weeks, then decreases until weeks 133 and goes up like the number of males (

Figure 6 (b)). This pattern is due to the therapy starting at a low level for the first 8 weeks before reaching its maximum (see

Figure 6 (e)). As we can see in

Figure 6 (c) and (d), although this strategy decreases the number of reservoir and infected sand fly, it can’t decrease these variables to their lowest possible level like that of Strategy A. When the therapy intensifies, the number of infected individuals starts to decrease, but as the treatment level reduces, the infected populations of both male and female humans begin to rise again. Maintaining animal culling at its maximum level for the first 133 weeks ensures that the number of infected reservoirs remains at an optimal low level throughout this period.

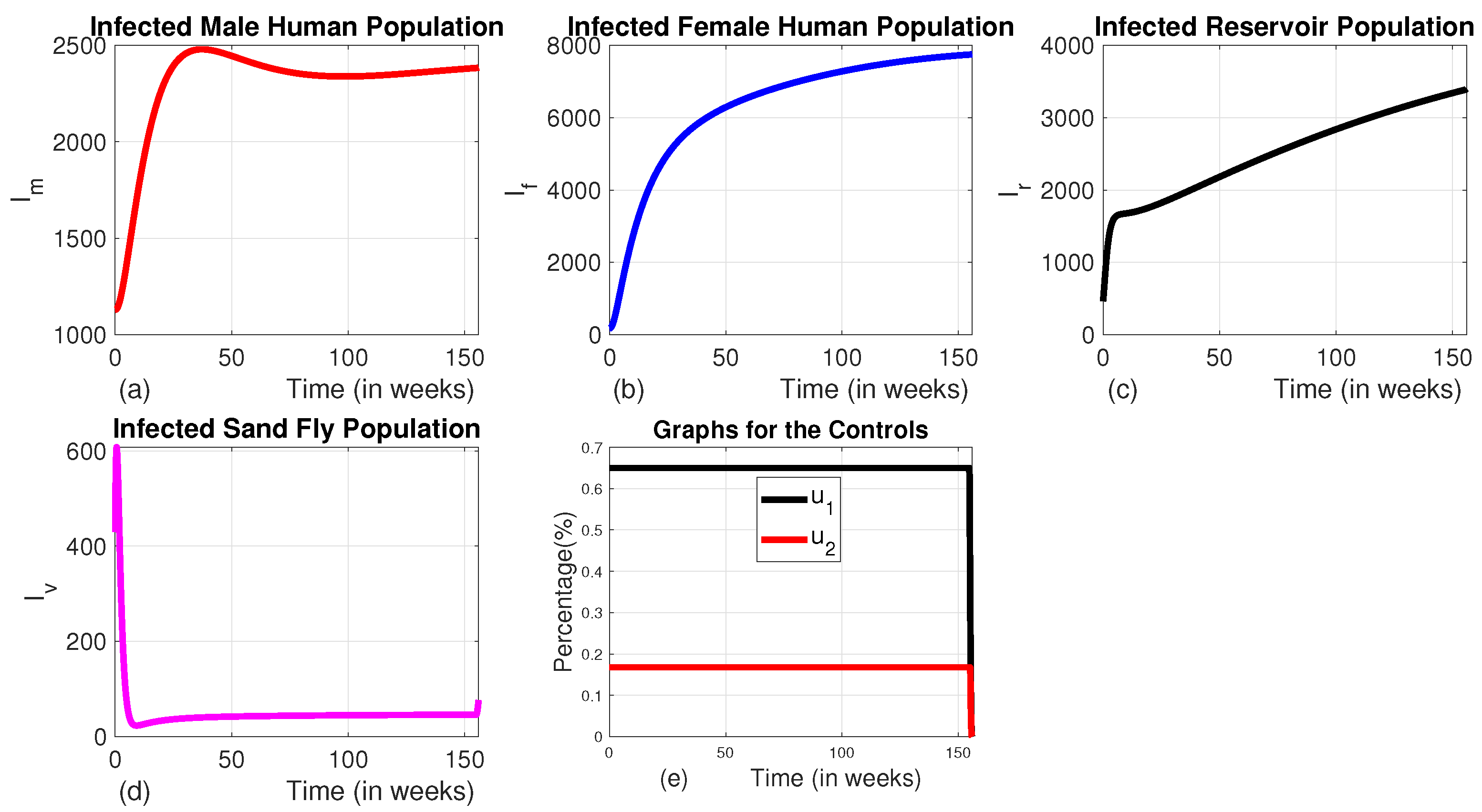

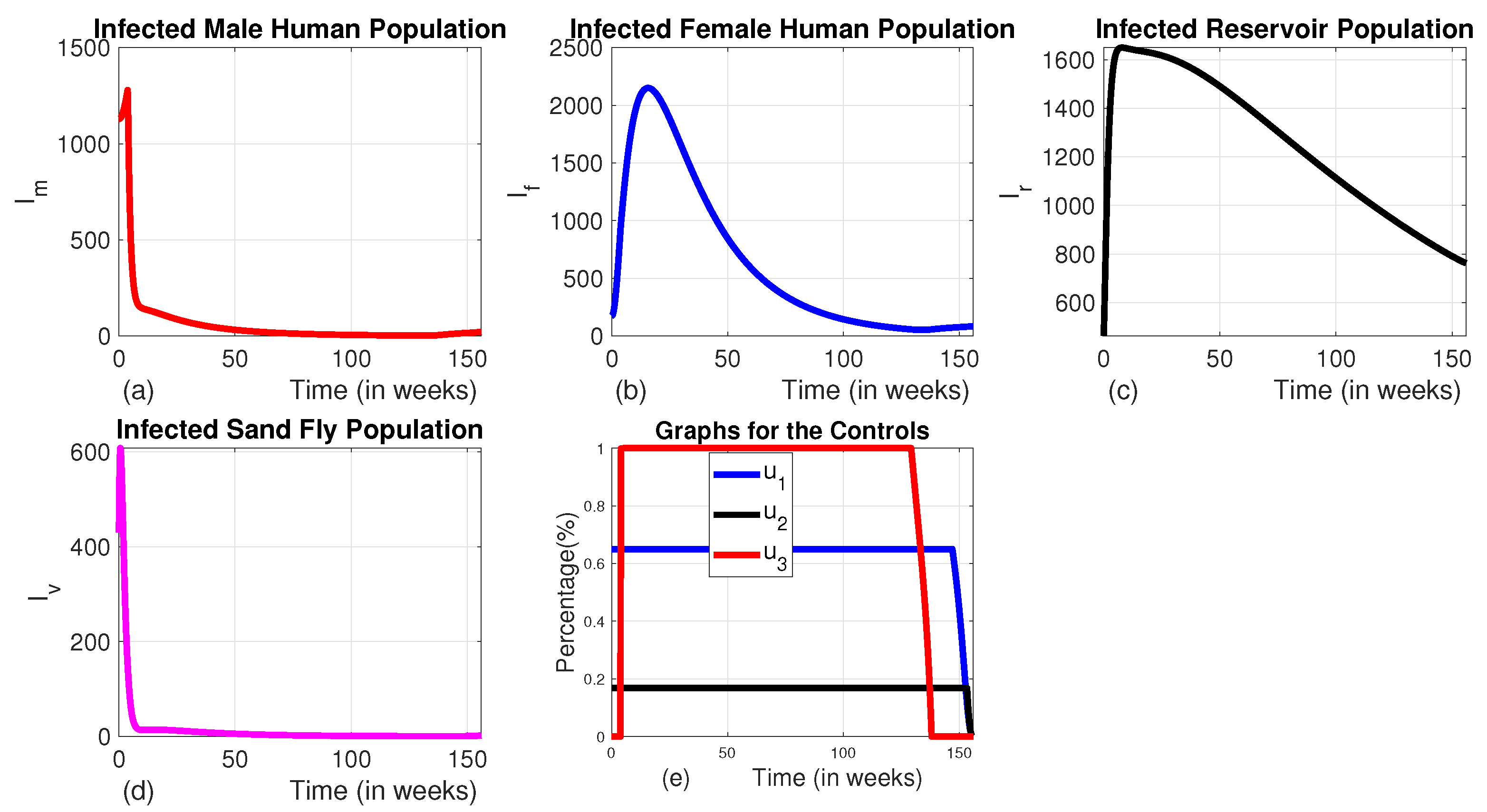

3.1.3. Strategy C (the Combination of the Use of Insecticide-Treated Bed Nets and Vector Control Without the Use of Medical Treatment and Animal Culling ( and )

In strategy C, we employed a combination of insecticide-treated bed nets and vector control, while other interventions like medical treatment and culling of infected animals were set to zero. This strategy results in a significant reduction by

of the number of infected males (

Figure 7 (a)) from the baseline by the end of the intervention period. Although it also reduces the number of infected females significantly (by

) as compared to the scenario without any control measures, the decline is lower than that of males (

Figure 7 (b)). This could be due to the

use of the control

for the female human population. With the use of this Strategy, one can observe that the number of infected vectors and infected reservoirs also decrease by

and

respectively compared to the baseline at the end of the intervention period

7 (c) and (d)).

Figure 7 (e) indicates that the control profile for insecticide-treated bed nets and vector control should continue at their full intensity for the whole planning period.

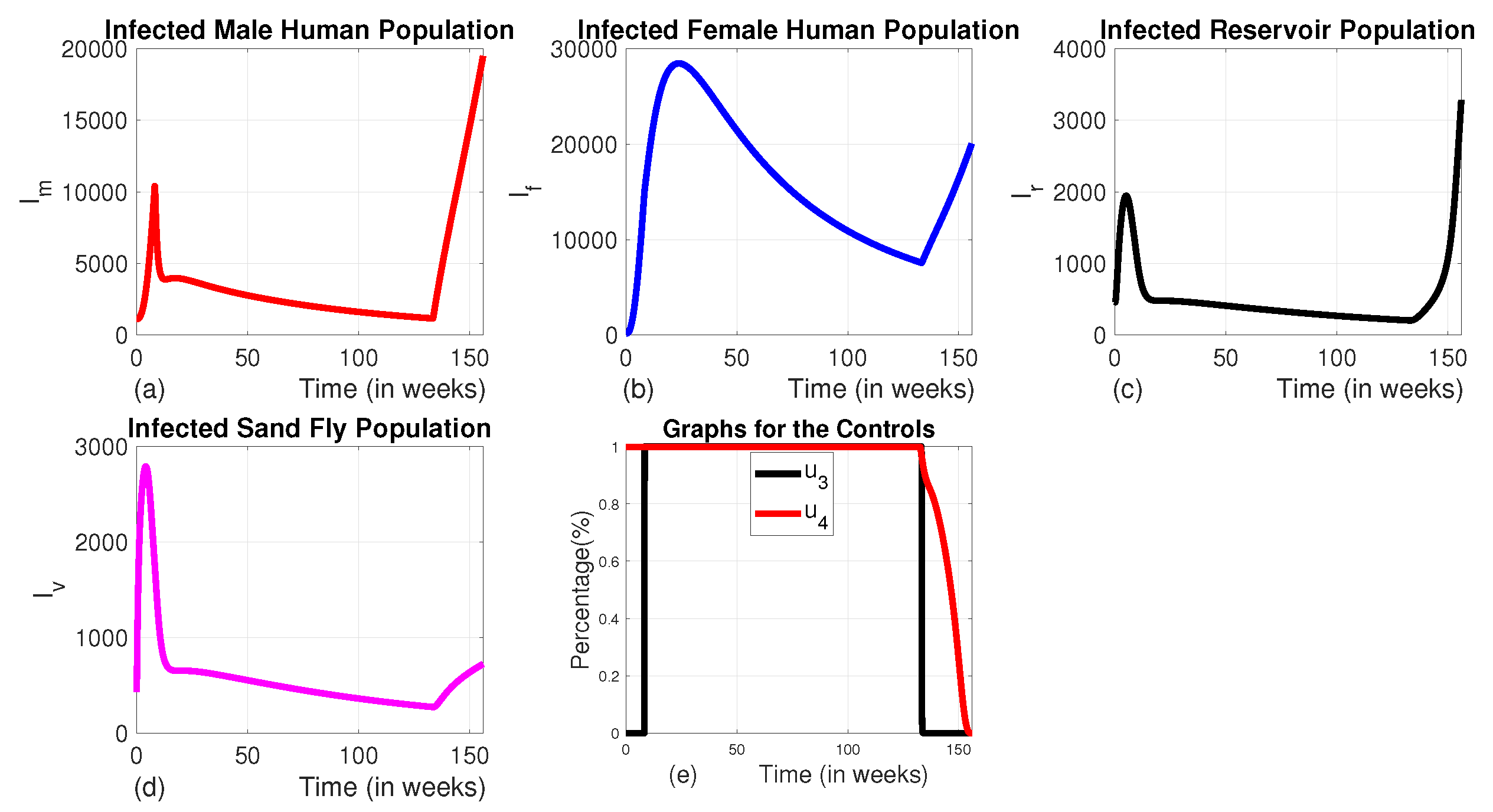

3.1.4. Strategy D (the Combination of Use of Vector Control and Animal Culling Without Insecticide Treated Bed-Nets and Medical Treatment ( and )

Here, we employed the combination of the use of vector control and animal culling without insecticide-treated bed nets and medical treatment. When comparing the effect of Strategy D to the uncontrolled scenario, there is an exponential decline in the number of infected male and female humans, as well as sand fly populations (see

Figure 8 (a), (b) and (c)). The number of infected reservoirs increases for the first three weeks and decreases until week 14, then rises (

Figure 7 (d)). To achieve this, vector control is maintained at its maximum levels for the whole planning period, and animal culling is also at its maximum level for the first 25 weeks before going to the minimum, as shown in

Figure 7 (e)).

3.1.5. Strategy E (the Combination of the Use of Insecticide-Treated Bed-Nets, Medical Treatment, and Animal Culling Without the Use of Vector Control ()

In this strategy, the combination of the use of ITNs, vector control, and animal culling is employed without the use of medical treatment.

We can observe from

Figures 9 (a), (b), (c), and (d)) that this strategy significantly reduces the number of all infected classes like that of Strategy A. However, it takes a long time for the number of infected sand flies to reach the minimum level as compared to that of strategy A due to the absence of a vector control strategy in this approach. The number of infected female human populations also does not reach the minimum possible level in the intervention period as to that of Strategy A. The profile of control graphs is also similar to Strategy A.

3.1.6. Strategy F (the Combination of the Use of Insecticide-Treated Bed Nets, Vector Control and Medical Treatment Without the Use of Animal Culling ()

In this approach, we employed the combination of the three controls

,

, and

without using infected animal culling. In this strategy, the number of infected reservoirs increases exponentially for the first 7.8 weeks and turns to decrease. Whereas the number of infected male, female, and sand fly populations decrease significantly (

Figures 10 (a), (b), (c) and (d)).

The intervention Strategies have been implemented for 156 weeks or three years following the VL data recorded in the study by Awoke et al. [

10].

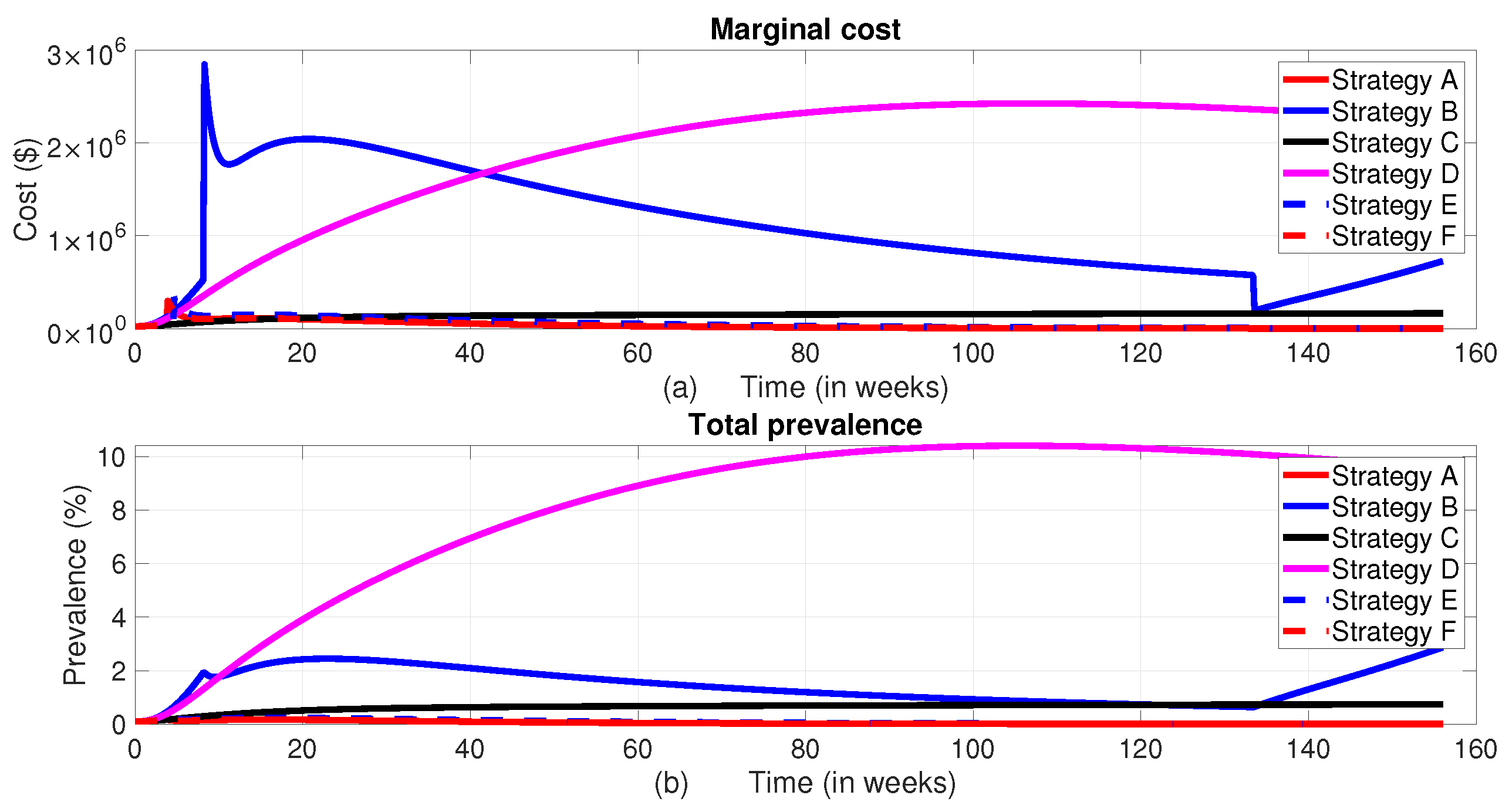

When all control measures are implemented, the total disease prevalence reaches its optimal level. As shown in

Figure 11, Strategy F and Strategy E also prove to be effective in reducing the total prevalence, ranking just below Strategy A in terms of the level of total prevalence and their corresponding total cost. On the other hand, Strategy D does not seem to help in controlling the disease, as both the disease prevalence and associated costs increase during the planning period unlike the others. The cost-effectiveness of these strategies will be analyzed in the subsection below.

3.1.7. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of the Proposed Strategies

Cost-effectiveness analysis is a method used to compare the relative costs and outcomes of different interventions or strategies. In the context of optimal control strategies, cost-effectiveness analysis evaluates whether the benefits achieved by implementing a particular control strategy outweigh its costs. In order to understand the cost-effectiveness of each of the optimal combinations, the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) is calculated for each strategy. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) is the additional cost per health outcome [

8]. It is the ratio of the difference in total cost between one strategy and the next best alternative to the difference in total number of averted infections through each strategy [

46,

48]. The number of infections averted is the difference between the total number of infected individuals without control and the total count of infected individuals with control obtained during the control period. To implement the ICER, we simulate the model corresponding to each of the six intervention strategies and apply the formula in Eq.(

17). Using these simulation results, we rank the control strategies in increasing order of effectiveness based on infection averted as indicated in

Table 3. Accurately estimating the costs associated with interventions that prevent infections and connecting those costs to the Quality Life Adjusted Years (QALYs) gained is crucial for ICER calculation. However, associating the computation of ICER with QALYs is complicated due to the indirect costs, opportunity costs, and variations in health-care systems, as well as other factors. As a result, we did not express ICER in terms of QALYs in this study.

After arranging the Strategies in ascending order based on the total infections averted, the Incremental Cost-Effectiveness Ratio (ICER) is calculated using the method outlined by [

9]. The ICER values are then compared pairwise to identify the most cost-effective strategy.

The pairwise comparisons of the calculated ICER for the different scenarios and corresponding total cost are given in

Table 4.

From ICER of D and ICER of B, it is evident that Strategy B’s ICER is lower than that of Strategy D. This demonstrates that Method D is less successful in saving lives and more costly. As a result, Strategy B saves more lives than Strategy D. Strategy D was omitted as a competing strategy, and we calculated the ICER for the remaining strategies, B, C, E, F and A, following the same procedure as in the above, and the result is as shown in

Table 5.

As we can see from

Table 5, when we compare the ICERs of Strategy B and Strategy C, Strategy C has a lower ICER than Strategy B. This shows that Strategy B is strongly dominated by the lower ICER over Strategy C. In other words, compared to Strategy C, Strategy B is less successful and costs more. As a result, Strategy B is excluded in the list of options. Following the same procedures, we have computed the ICERs values as indicated in

Table 6.

From

Table 6, by comparing the ICERs of Strategy C and Strategy E, we can observe that Strategy E has a lower ICER and is hence cost effective than Strategy C.

By repeating this process, we can identify the next most cost-effective strategy. From this analysis, Strategy E is found to be the next in line, followed by Strategy F. A final comparison of Strategies F and A shows that Strategy F is strongly dominant, which means it is both more expensive and less effective than Strategy A. Therefore, Strategy A, which is the combination of all four controls, i.e., insecticide-treated bed nets, vector control, treatment of infected human populations, and infected animal culling, emerges as the most cost-effective disease control strategy, as it has the lowest ICER.

The cost-effectiveness analysis results of this study align with those of a study conducted by Agusto et al. [

9] even if our control Strategy proposes only

of the controls in insecticide-treated bed-nets and treatment to be provided to the female humans as compared to the one to be given to the male counterpart. Their findings indicate that the most cost-effective intervention strategy for controlling the transmission of malaria-VL co-infection involves using personal protection measures, insecticide-treated bed nets, culling infected animal reservoirs, and applying insecticides.

According to the calculated ICER, Strategy F, which involves all control strategies except animal culling, is the second cost-effective intervention. This finding is consistent with the results of Zhao et al. [

19], who state that animal culling is an ineffective VL control strategy. The third most cost-effective strategy, according to our comparison result, includes using insecticide-treated be nets, medical treatment, and animal culling without using vector control or Strategy E.

4. Conclusions

In this paper, a mathematical model for the dynamics of sex-structured visceral leishmaniasis transmission model is presented and analyzed. We have added four time-dependent control variables to establish optimal disease control strategies. These control variables include treating infected male and female human populations, vector control, using bed-nets treated with insecticide and culling of infected animals. Positivity and boundedness of the solution, as well as the basic reproduction number with constant control, are computed. We derived and analyzed the necessary conditions for the optimal control problem by using Pontryagin’s maximum principle. The numerical simulations show that the overall prevalence of the disease will decrease over time with the inclusion of each of these control techniques into the model. Cost-effectiveness analysis is employed to evaluate the economic implications of the various combinations of the four control measures for VL. To investigate the cost-effectiveness of every possible strategies, we have computed the Incremental Cost-Effectiveness Ratio (ICER). We did a pairwise comparison of the ICER of each strategy and identified the strategy with a smaller ICER, which averts more infections in humans and utilizes the smallest possible cost of intervention.

The result shows a comprehensive evaluation of various intervention strategies aimed at reducing disease transmission and prevalence. The findings show that the most effective and cost-efficient approach is Strategy A, which combines all the four key controls: insecticide-treated bed nets, vector control, medical treatment of infected individuals, and culling of infected animal reservoirs. This strategy leads to a significant and sustained reduction in the number of infected male and female humans, vectors (e.g., sand flies), and animal reservoirs. The intervention’s success is attributed to the simultaneous targeting of multiple transmission pathways, ensuring that disease prevalence decreases rapidly and remains low throughout the intervention period.

Cost-effectiveness analysis, using the Incremental Cost-Effectiveness Ratio (ICER), further validates Strategy A as the optimal solution, providing the greatest reduction in disease prevalence for the lowest cost. Strategy E, which excludes vector control, and Strategy F, which omits animal culling, are also effective but rank lower in cost-effectiveness. These strategies reduce disease prevalence but do not achieve the same level of control as Strategy A. The study highlights that strategies like B (medical treatment and culling without bed nets or vector control) and D (vector control and culling without bed nets or medical treatment) are less efficient. Although they reduce some components of the infected population, they fail to maintain low infection levels over the intervention period and are more costly, making them suboptimal.

Our findings emphasize the importance of a multi-pronged approach for VL control. Strategies that focus on just one or two interventions, or that limit the application of controls to certain populations, are less successful and more expensive in the long term. The analysis was done by applying a 50% control strategy to the female humans, compared to their male counterparts. As can be seen from the evaluation, it can still effectively eliminate the burden of VL from the entire population within the planning period. Integrated intervention strategies, like Strategy A provides the most effective means of reducing both disease prevalence and long-term socio-economic impacts. Furthermore, the study underscores the need for a careful balance between cost and effectiveness, as shown by the ICER analysis, to optimize resource allocation in public health programs to control persistent infectious diseases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Kassa S. M. and Awoke T.D.; Methodology, Awoke T.D. and Kassa S. M.; Software, Awoke T.D. and Kassa S. M.; Validation, Awoke T.D., Kassa S. M. and Tsidu G.M.; Formal analysis, Awoke T. D.; Investigation, Awoke T. D.; Writing - original draft, Awoke T. D.; Writing - review and editing, Awoke T. D., Kassa S. M., Morupisi K. S. and Tsidu G.M.; Supervision, Kassa S. M., Morupisi K. S. and Tsidu G.M.; Funding acquisition, Tsidu G.M.; Project administration, Tsidu G.M.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge that this work was carried out with the aid of a grant from the O.R. Tambo Africa Research Chairs Initiative as supported by the Botswana International University of Science and Technology, the Ministry of Tertiary Education, Science and Technology; the National Research Foundation of South Africa (NRF); the Department of Science and Innovation of South Africa (DSI); the International Development Research Centre of Canada (IDRC); and the Oliver & Adelaide Tambo Foundation (OATF).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Song, H; Tian, D; Shan, C. Modeling the effect of temperature on dengue virus transmission with periodic delay differential equations. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2020; 17, 4147-64. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lockard, R. D.; Wilson, M. E.; Rodríguez, N. E. Sex-related differences in immune response and symptomatic manifestations to infection with Leishmania species. Journal of immunology research 2019, 2019: 4103819. [CrossRef]

- Moncaz, A.; Faiman, R.; Kirstein, O.; Warburg, A. Breeding sites of Phlebotomus sergenti, the sand fly vector of cutaneous leishmaniasis in the Judean Desert. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 2012, 6, e1725. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, B.; Maroli, M. Control of phlebotomine sandflies. Medical and veterinary entomology 2003, 17, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maroli, M.; Khoury, C. Prevention and control of leishmaniasis vectors: current approaches. Parassitologia 2004, 46, 211-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montenegro, Quiñonez C.A.; Runge-Ranzinger, S.; Rahman, K.M.; Horstick, O. Effectiveness of vector control methods for the control of cutaneous and visceral leishmaniasis: A meta-review. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2021, 15, e0009309. [CrossRef]

- Alvar, J.; Vélez, I.D.; Bern, C.; Herrero, M.; Desjeux, P.; Cano, J.; Jannin, J.; Boer, M.D. WHO Leishmaniasis Control Team. Leishmaniasis worldwide and global estimates of its incidence. PloS one 2012, 7, e35671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agusto, F. B. Optimal isolation control strategies and cost-effectiveness analysis of a two-strain avian influenza model. Biosystems 2013, 113, 155-64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agusto, F.B.; ELmojtaba, I.M. Optimal control and cost-effective analysis of malaria/visceral leishmaniasis co-infection. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0171102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awoke, T.D.; Kassa, S.M.; Morupisi, K.S.; Tsidu, G.M. Sex-structured disease transmission model and control mechanisms for visceral leishmaniasis (VL). Plos one 2024, 19, e0301217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ELmojtaba IM. Mathematical model for the dynamics of visceral leishmaniasis–malaria co-infection. Mathematical Methods in the Applied Sciences 2016, 39, 4334-53. [CrossRef]

- Shimozako, H.J.; Wu, J.; Massad, E. Mathematical modelling for Zoonotic Visceral Leishmaniasis dynamics: A new analysis considering updated parameters and notified human Brazilian data. Infectious Disease Modelling 2017, 2, 143-60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S. Mathematical modeling of visceral leishmaniasis and control strategies. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals 2017, 104, 546-56. [CrossRef]

- Rock, K.S.; le Rutte, E.A.; de Vlas, S.J.; Adams, E.R.; Medley, G.F.; Hollingsworth, T.D. Uniting mathematics and biology for control of visceral leishmaniasis. Trends in parasitology 2015, 31, 251-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramanian, A.; Singh, V.; Sarkar, R.R. Understanding visceral leishmaniasis disease transmission and its control-a study based on mathematical modeling. Mathematics 2015, 3, 913-44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.; Chen, J.; Ruan, S. Modeling and analyzing the transmission dynamics of visceral leishmaniasis. Mathematical Biosciences & Engineering 2017, 14, 1585-604. [CrossRef]

- Alvar, J.; Molina, R.; San Andrés, M.; Tesouro, M.; Nieto, J.; Vitutia, M.; González, F.; San Andrés, M.D.; Boggio, J.; Rodriguez, F.; Sainz, A. Canine leishmaniasis: clinical, parasitological and entomological follow-up after chemotherapy. Annals of Tropical Medicine & Parasitology 1994, 88, 371-8. [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, R; Panicker, K.N. Laboratory observations on the biology of the phlebotomid sandfly, Phlebotomus papatasi (Scopoli, 1786). Southeast Asian journal of tropical medicine and public health 1993, 24, 536-539. [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.; Kuang, Y.; Wu, C.H.; Ben-Arieh, D. Ramalho-Ortigao, M.; Bi, K. Zoonotic visceral leishmaniasis transmission: modeling, backward bifurcation, and optimal control. Journal of mathematical biology 2016, 73, 1525-60. [CrossRef]

- Pantha, B.; Agusto, F.B.; Elmojtaba, I.M. Optimal control applied to a visceral leishmaniasis model. Electronic Journal of Differential Equations 2020, 80, 1-24. https://hdl.handle.net/1808/33378.

- Ghosh, I.; Sardar, T.; Chattopadhyay, J. A mathematical study to control visceral leishmaniasis: an application to South Sudan. Bulletin of mathematical biology 2017, 79, 1100-34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DebRoy, S.; Prosper, O.; Mishoe, A.; Mubayi, A. Challenges in modeling complexity of neglected tropical diseases: a review of dynamics of visceral leishmaniasis in resource limited settings. Emerging themes in epidemiology 2017, 14, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockdale, L.; Newton, R. A review of preventative methods against human leishmaniasis infection. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 2013, 7(6), e2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization, VL fact sheet. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/leishmaniasis (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Chapman, L.A.; Dyson, L.; Courtenay, O,; Chowdhury, R.; Bern, C.; Medley, G.F.; Hollingsworth, T.D. Quantification of the natural history of visceral leishmaniasis and consequences for control. Parasites & vectors 2015, 8, 1-3. [CrossRef]

- Joshi, A.B.; Das, M.L.; Akhter, S.; Chowdhury, R.; Mondal, D.; Kumar, V.; Das, P.; Kroeger, A.; Boelaert, M.; Petzold, M. Chemical and environmental vector control as a contribution to the elimination of visceral leishmaniasis on the Indian subcontinent: cluster randomized controlled trials in Bangladesh, India and Nepal. BMC medicine 2009, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, A. L.; Courtenay, O.; Kelly-Hope, L.A.; Scott, T.W.; Takken, W.; Torr, S.J.; Lindsay, S.W. The importance of vector control for the control and elimination of vector-borne diseases. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 2020, 14(1), e0007831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asfaw, M.D.; Buonomo, B.; Kassa, S.M. Impact of human behavior on ITNs control strategies to prevent the spread of vector borne diseases. Atti della Accademia Peloritana dei Pericolanti-Classe di Scienze Fisiche, Matematiche eNaturali 2018, 96(S3), 2. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, B.N,; Nabi, S.G,; Rahman, M.; Selim, S.; Bashar, A.; Rashid, M.M.; Lira, F.Y.; Choudhury, T.A.; Mondal, D. Kala-azar (visceral leishmaniasis) elimination in Bangladesh: successes and challenges. Current Tropical Medicine Reports 2014, 1, 163-9. [CrossRef]

- Matlashewski, G.; Arana, B.; Kroeger, A.; Battacharya, S.; Sundar, S.; Das, P.; Sinha, P.K.; Rijal, S.; Mondal, D.; Zilberstein, D.; Alvar, J. Visceral leishmaniasis: elimination with existing interventions. The Lancet infectious diseases 2011, 11(4), 322-5. [CrossRef]

- Balaska, S.; Fotakis, E.A.; Chaskopoulou, A.; Vontas, J. Chemical control and insecticide resistance status of sand fly vectors worldwide. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 2021, 15(8), e0009586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaria Consortium. Leishmaniasis control in eastern africa: Past and present efforts and future needs. Situation and gap analysis 86 (2010).

- Maia, C.; Dantas-Torres, F.; Campino, L. Parasite Biology: The Reservoir Hosts. In The Leishmaniases: Old Neglected Tropical Diseases Bruschi, F., Gradoni, L., Eds.; Springer Nature, Gewerbestrasse, Switzerland, 2018, pp. 79-106.

- Costa, C.H.; How effective is dog culling in controlling zoonotic visceral leishmaniasis? a critical evaluation of the science, politics and ethics behind this public health policy. em Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2011, 44, 232-42. [CrossRef]

- Van den Driessche, P.; Watmough, J. Reproduction numbers and sub-threshold endemic equilibria for compartmental models of disease transmission. Mathematical biosciences 2002, 180(1-2), 29-48. [CrossRef]

- Fleming, W.H., Rishel, R.W. 1st edt.; Deterministic and stochastic optimal control, Springer Verlag: New York Heidelberg, Switzerland, 2012.

- Earl, A.C.; Norman, L.; Teichmann, T. Theory of Ordinary Differential Equations. Physics Today 1956, 9 (2), 18. [CrossRef]

- Awoke, T.D.; Kassa, S.M.; Morupisi, K.S.; Tsidu, G.M. Sex-structured disease transmission model and control mechanisms for visceral leishmaniasis (VL). Plos one 2024, 19(4), e0301217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbu, V.; Precupanu, T. Convexity and optimization in Banach spaces, Springer Science & Business Media: New York, 2012.

- Pedregal, P. Variational Problems and Dynamic Programming. In Introduction to Optimization. Texts in Applied Mathematics, Marsden, J.E., Sirovich, L., Antman, S. S., Eds.; Springer, New York, NY, vol 46, 2004, pp. 137-194.

- Kassa, S.M.; Hove-Musekwa, S.D. Optimal control of allocation of resources and the economic growth in HIV-infected communities. Optimal Control Applications and Methods 2014, 35(6), 627-46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fister, K.R.; Lenhart, S.; McNally, J.S. Optimizing chemotherapy in an hiv model. Electronic Journal of Differential Euquations 1998, 1998(32), 1-12.

- Gaff, H.; Schaefer, E. Optimal control applied to vaccination and treatmentstrategies for various epidemiological models. Mathematical biosciences & engineering 2009, 6(3), 469-92. [CrossRef]

- Kassa, S.M.; Ouhinou, A. The impact of self-protective measures in the optimal interventions for controlling infectious diseases of human population. Journal of Mathematical Biology 2015, 70, 213-36. [CrossRef]

- Blayneh, K.W.; Gumel, A.B.; Lenhart, S.; Clayton, T. Backward bifurcation and optimal control in transmission dynamics of West Nile virus. Bulletin of mathematical biology 2010, 72, 1006-28. [CrossRef]

- Berhe, H.W.; Makinde, O.D.; Theuri, D.M. Co-dynamics of measles and dysentery diarrhea diseases with optimal control and cost-effectiveness analysis. Applied Mathematics and Computation 2019, 347, 903-21. [CrossRef]

- Lenhart, S.; Workman, J.T. Optimal control applied to biological models. 1st edt.; Chapman and Hall/CRC: New York, 2007.

- Workineh, Y.H.; Kassa, S.M. Optimal control of the spread of meningitis: in the presence of behaviour change of the society and information dependent vaccination. Commun. Math. Biol. Neurosci bf 2021, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Chappuis, F.; Sundar, S.; Hailu, A.; Ghalib, H.; Rijal, S.; Peeling, R.W.; Alvar, J.; Boelaert, M. Visceral leishmaniasis: what are the needs for diagnosis, treatment and control?. Nature reviews microbiology 2007, 5(11), 873-82. [CrossRef]

- Wamai, R.G.; Kahn, J.; McGloin, J.; Ziaggi, G. Visceral leishmaniasis: a global overview. Journal of Global Health Science 2020, 2(1). [CrossRef]

Figure 2.

The effect of on prevalence of VL.

Figure 2.

The effect of on prevalence of VL.

Figure 3.

The dynamics of infected classes without an intervention.

Figure 3.

The dynamics of infected classes without an intervention.

Figure 4.

The dynamics of the total prevalence and control costs at different values of and .

Figure 4.

The dynamics of the total prevalence and control costs at different values of and .

Figure 5.

The dynamics of infected populations with Strategy A and the graph of controls profile. a) the number of infected male human populations with Strategy A, b) the number of infected female human populations with Strategy A, c) the number of infected reservoir populations with Strategy A, d) the number of infected sand fly populations with Strategy A, and e) the graph of controls profile.

Figure 5.

The dynamics of infected populations with Strategy A and the graph of controls profile. a) the number of infected male human populations with Strategy A, b) the number of infected female human populations with Strategy A, c) the number of infected reservoir populations with Strategy A, d) the number of infected sand fly populations with Strategy A, and e) the graph of controls profile.

Figure 6.

The dynamics of infected populations with Strategy B and the graph of controls profile. a) the number of infected male human populations with Strategy B, b) the number of infected female human populations with Strategy B, c) the number of infected reservoir populations with Strategy B, d) the number of infected sand fly populations with Strategy B, e) the graph of controls profile.

Figure 6.

The dynamics of infected populations with Strategy B and the graph of controls profile. a) the number of infected male human populations with Strategy B, b) the number of infected female human populations with Strategy B, c) the number of infected reservoir populations with Strategy B, d) the number of infected sand fly populations with Strategy B, e) the graph of controls profile.

Figure 7.

The dynamics of infected populations with Strategy C and the graph of controls profile. a) the number of infected male human populations with Strategy C, b) the number of infected female human populations with Strategy C, c) the number of infected reservoir populations with Strategy C, d) the number of infected sand fly populations with Strategy C, and e) the graphs of the controls profile.

Figure 7.

The dynamics of infected populations with Strategy C and the graph of controls profile. a) the number of infected male human populations with Strategy C, b) the number of infected female human populations with Strategy C, c) the number of infected reservoir populations with Strategy C, d) the number of infected sand fly populations with Strategy C, and e) the graphs of the controls profile.

Figure 8.

The dynamics of infected populations with Strategy D and the graph of controls profile. a) the number of infected male human populations with Strategy D, b) the number of infected female human populations with Strategy D, c) the number of infected reservoir populations with Strategy D, d) the number of infected sand fly populations with Strategy D, and e) the graph of controls profile.

Figure 8.

The dynamics of infected populations with Strategy D and the graph of controls profile. a) the number of infected male human populations with Strategy D, b) the number of infected female human populations with Strategy D, c) the number of infected reservoir populations with Strategy D, d) the number of infected sand fly populations with Strategy D, and e) the graph of controls profile.

Figure 9.

The dynamics of infected populations with Strategy E and the graph of controls profile. a) the number of infected male human populations with Strategy E b) the number of infected female human populations with Strategy E c) the number of infected reservoir populations with Strategy E d) the number of infected sand fly populations with Strategy E e) the graph of controls profile.

Figure 9.

The dynamics of infected populations with Strategy E and the graph of controls profile. a) the number of infected male human populations with Strategy E b) the number of infected female human populations with Strategy E c) the number of infected reservoir populations with Strategy E d) the number of infected sand fly populations with Strategy E e) the graph of controls profile.

Figure 10.

The dynamics of infected populations with Strategy F and the graph of controls profile. a) the number of infected male human populations with Strategy E b) the number of infected female human populations with Strategy E c) the number of infected reservoir populations with Strategy E d) the number of infected sand fly populations with Strategy E e) the graph of controls profile.

Figure 10.

The dynamics of infected populations with Strategy F and the graph of controls profile. a) the number of infected male human populations with Strategy E b) the number of infected female human populations with Strategy E c) the number of infected reservoir populations with Strategy E d) the number of infected sand fly populations with Strategy E e) the graph of controls profile.

Figure 11.

The dynamics of the total prevalence of the disease and total intervention cost.

Figure 11.

The dynamics of the total prevalence of the disease and total intervention cost.

Table 1.

Definition of model parameters.

Table 1.

Definition of model parameters.

| Parameters |

Description of parameters |

|

recruitment rate of men and women human population |

|

recruitment rate of reservoir (Animal), vector (sand fly) population |

|

life expectancy of human, vector(sand fly), reservoir population |

|

force of infection for human, sand fly and reservoir population |

|

progression rate from asymptomatic to symptomatic |

|

disease induced death rates of men, women and reservoir population |

|

recovery rate of men & women human population from Asymptomatic |

|

recovery rate of men and women human population from symptomatic |

|

inverse of incubation period in human population |

|

lose of Immunity rate of male, female human, and reservoir population |

|

recovery rate of reservoirs |

| p |

the proportion of exposed men who join class from class. |

| q |

the proportion of exposed women who join class from class. |

|

,

|

the probability that susceptible humans, and reservoirs become infected |

| |

through a single bite of an infected sand flies respectively |

|

,

|

the probability that a susceptible sand fly becomes infected when |

| |

feeding on an infected human, and reservoirs respectively |

|

the number of bites that a reservoir host receives per week |

|

the number of times a single vector feeds on a reservoir host |

|

Modification parameters |

|

The capability of insecticide-treated bed-nets and insecticide |

| |

spraying to kill sand flies respectively. |

|

Modification parameters |

Table 2.

Parameter values used in the numerical simulations.

Table 2.

Parameter values used in the numerical simulations.

| Para. |

Description |

Unit |

Value |

Source |

|

recruitment rate of men human population |

persons

|

|

[10] |

|

recruitment rate of women human population |

persons

|

|

[10] |

|

natural mortality rate of human |

|

|

[10] |

|

natural mortality rate of reservoirs(dog) |

|

|

[10] |

|

natural mortality rate of sand flies |

|

|

[18] |

|

progression rate of male from to

|

proportion |

0.147 |

[25] |

|

progression rate of female from to

|

proportion |

0.147 |

[25] |

|

recovery rate of male from asymptomatic stage |

|

0.027525 |

[25] |

|

recovery rate of female from asymptomatic stage |

|

0.020094 |

[25] |

|

recovery rate of male from symptomatic stage |

|

0.028902 |

[25] |

|

recovery rate of female from symptomatic stage |

|

0.021098 |

[25] |

|

Rate of losing immunity of males |

|

0.001527 |

[25] |

|

Rate of losing immunity of females |

|

0.002077 |

[25] |

|

Rate of losing immunity of reservoirs. |

|

0.055556 |

[17] |

|

Inverse of incubation period of human population |

|

0.0625 |

[50] |

|

recruitment rate of reservoir (Animal)population |

reservoirs

|

491.04294 |

[10] |

|

recruitment rate of vector (sand fly) population |

vectors

|

691.95421 |

[10] |

| p |

proportion of exposed male who join Am from Em |

proportion |

0.64033 |

[10] |

| q |

proportion of exposed female who join Am from Em |

proportion |

0.16619 |

[10] |

|

the probability that becomes infected by

a single bite |

proportion |

0.01311 |

[10] |

|

the probability that becomes infected by

a single bite |

proportion |

0.15080 |

[10] |

|

the probability of becomes infected from human |

proportion |

0.16093 |

[10] |

|

the probability of becomes infected from reservoir |

proportion |

0.05090 |

[10] |

|

the number of bites in which a reservoir hosts receive |

per head

|

4.93540 |

[10] |

|

the number of times a single vector feeds on a reservoir |

per head

|

1.06446 |

[10] |

|

modification parameter |

proportion |

1.07488 |

[10] |

|

modification parameter |

proportion |

1.24648 |

[10] |

|

modification parameter |

proportion |

4.93806 |

[10] |

|

disease induced death rate of male |

proportion |

0.000035 |

[10] |

|

disease induced death rate of female |

proportion |

0.00264 |

[10] |

|

recovery rate of reservoirs |

|

0.00516 |

[10] |

|

disease induced death rate of reservoir |

proportion |

0.00031 |

[10] |

|

capability of ITNs to kill sand flies |

proportion |

0.25 |

Assumed |

|

effectiveness of insecticide spraying in killing sand flies |

proportion |

0.55 |

Assumed |

|

efficacy of VL drugs |

proportion |

|

Assumed |

|

Modification parameter |

proportion |

|

Assumed |

|

Modification parameter |

proportion |

|

Assumed |

Table 3.

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio in increasing order of total infection averted.

Table 3.

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio in increasing order of total infection averted.

| Strategies |

Total infection averted |

Cost ($) |

| D |

33,743 |

|

| B |

123, 876.3 |

|

| C |

153, 269.1 |

|

|

| E |

163, 154.8 |

|

| F |

163, 299.81 |

|

| A |

163, 340.15 |

|

Table 4.

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio in increasing order of total infection averted.

Table 4.

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio in increasing order of total infection averted.

| Strategies |

Total infection averted |

Cost ($) |

ICER |

| D |

33,743 |

|

|

| B |

123, 876.3 |

|

|

| C |

153, 269.1 |

|

|

| E |

163, 154.8 |

|

|

| F |

163, 299.81 |

|

|

| A |

163, 340.15 |

|

|

Table 5.

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio in increasing order of total infection averted.

Table 5.

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio in increasing order of total infection averted.

| Strategies |

Total infection averted |

Cost ($) |

ICER |

| B |

123, 876.3 |

|

|

| C |

153, 269.1 |

|

|

| E |

163, 154.8 |

|

|

| F |

163, 299.81 |

|

|

| A |

163, 340.15 |

|

|

Table 6.

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio in increasing order of total infection averted.

Table 6.

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio in increasing order of total infection averted.

| Strategies |

Total infection averted |

Cost ($) |

ICER |

| C |

153, 269.1 |

|

|

| E |

163, 154.8 |

|

|

| F |

163, 299.81 |

|

|

| A |

163, 340.15 |

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).