Submitted:

21 April 2025

Posted:

22 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

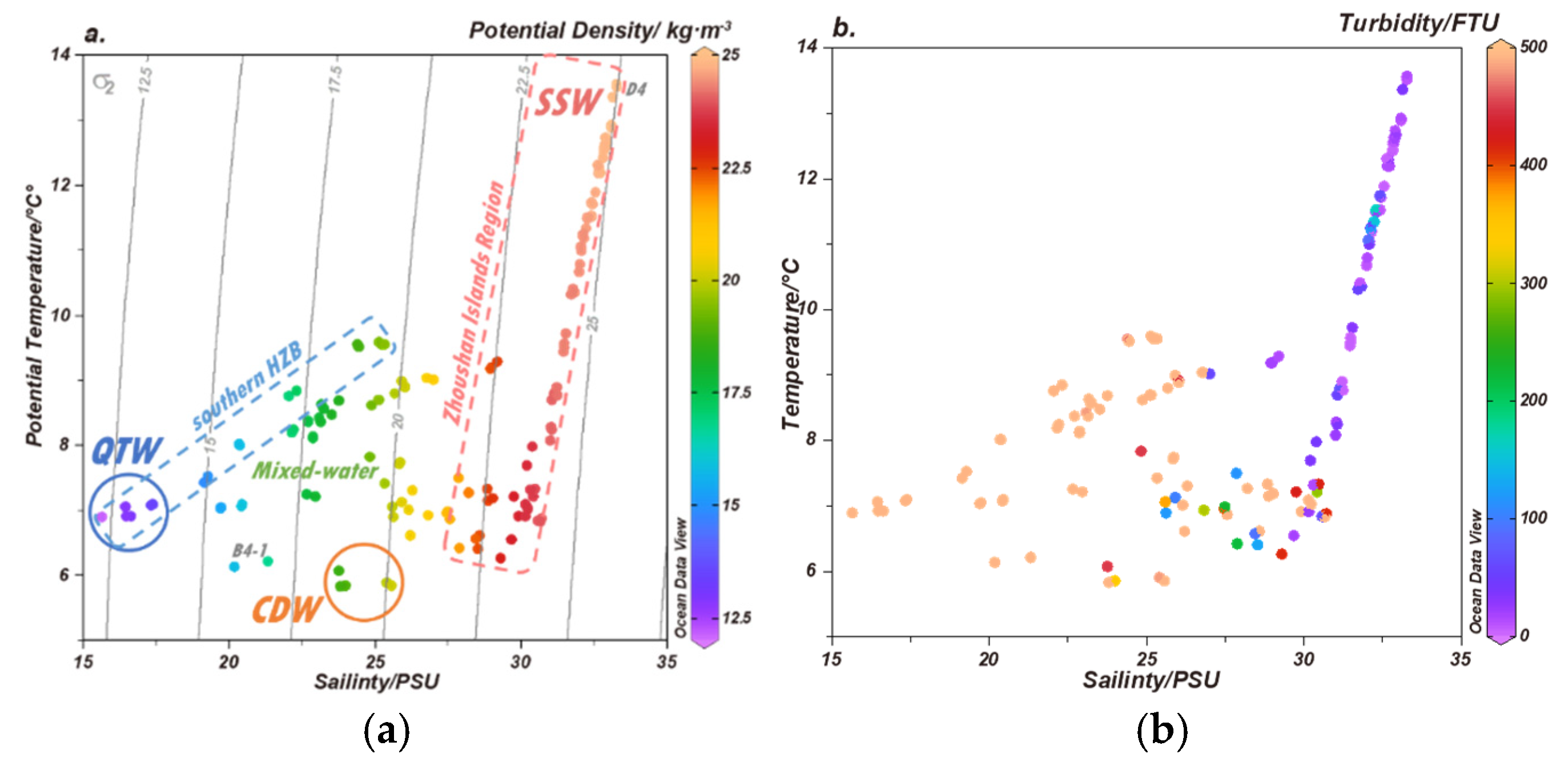

2.1. Hydrological and Hydrochemical Parameters in HZB and Adjacent Seas

2.2. Distributions of DOC in HZB and Adjacent Seas

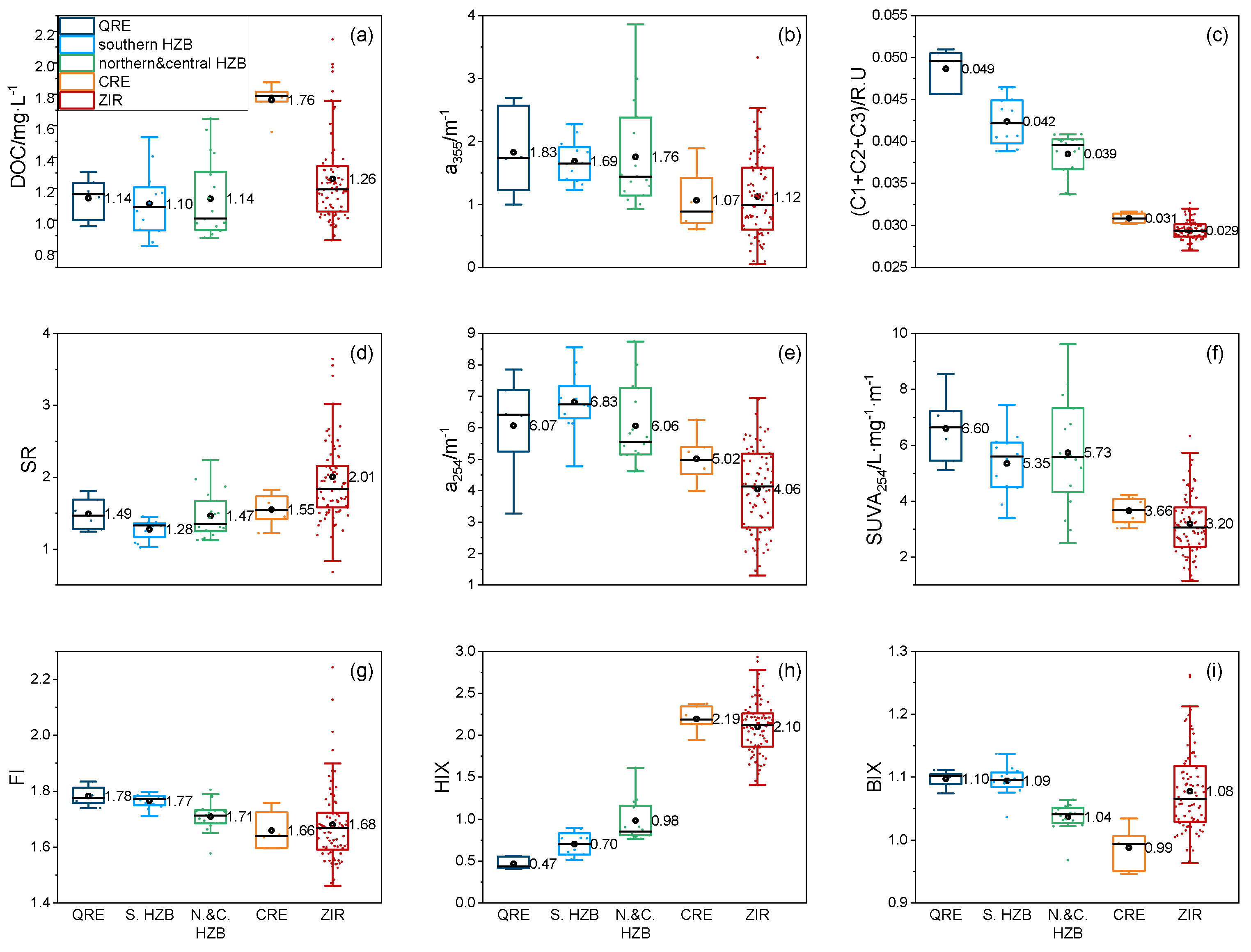

2.3. CDOM and FDOM Properties in HZB and Adjacent Seas

2.3.1. CDOM Coefficients

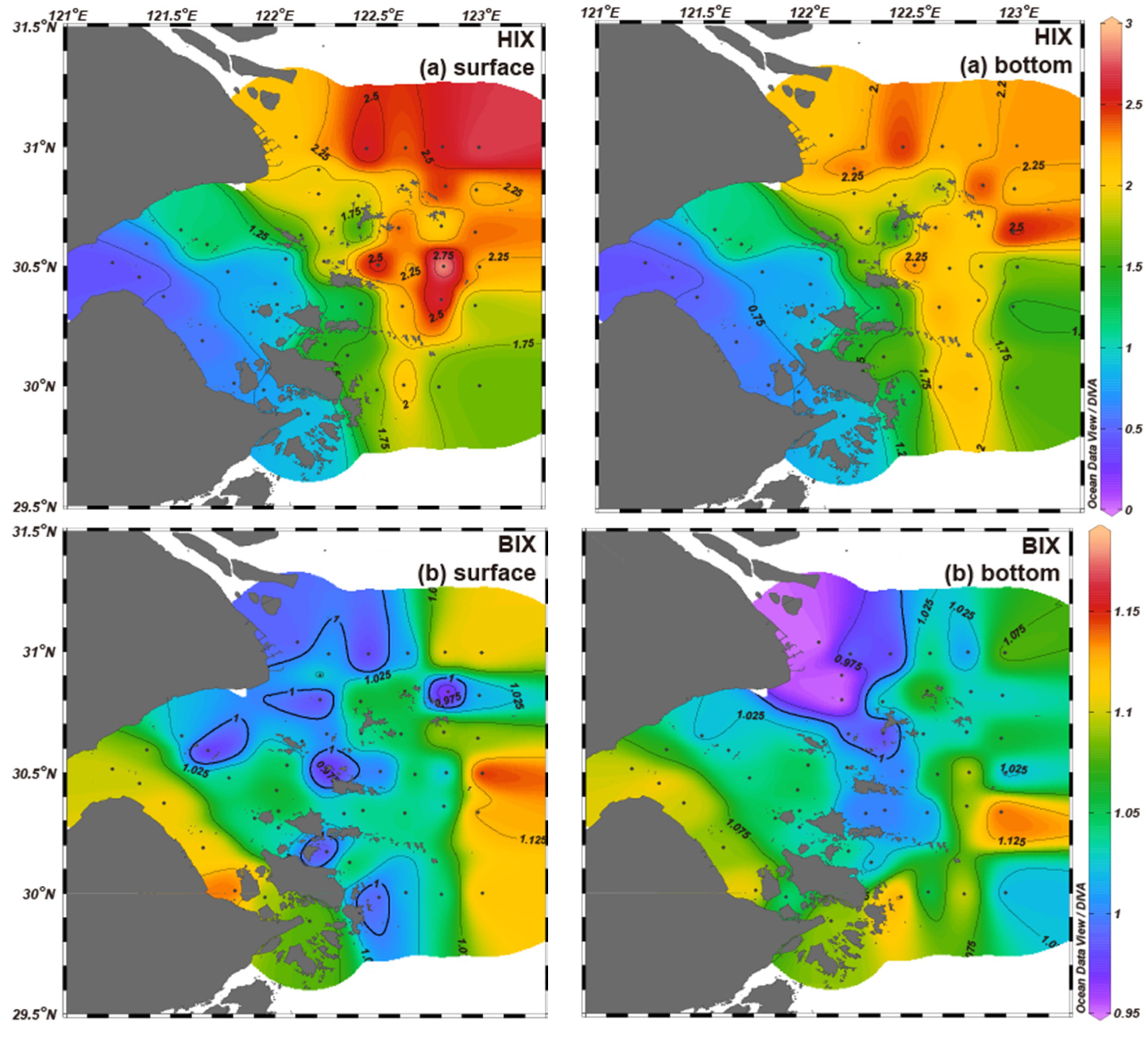

2.3.2. FDOM Indexes

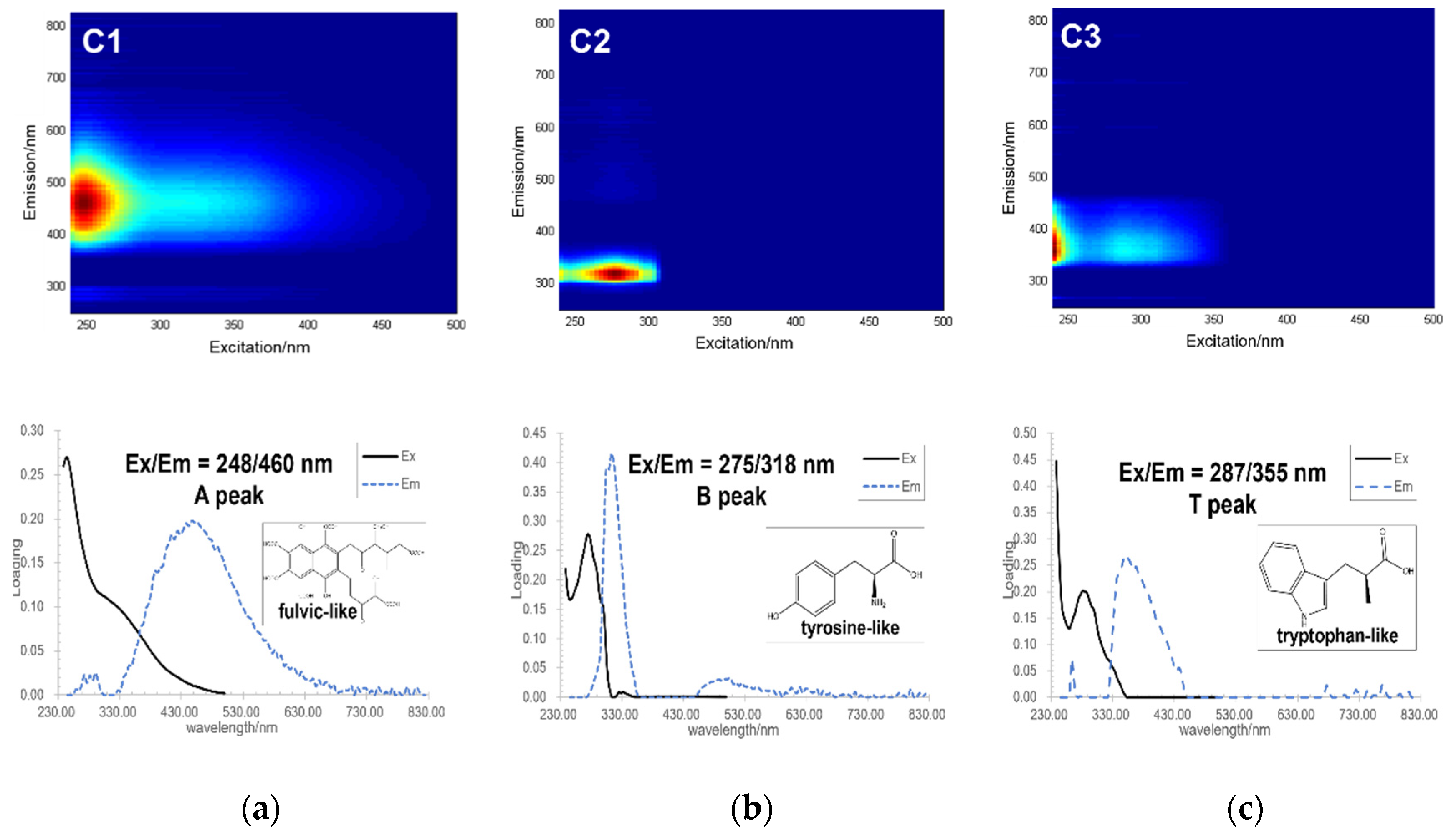

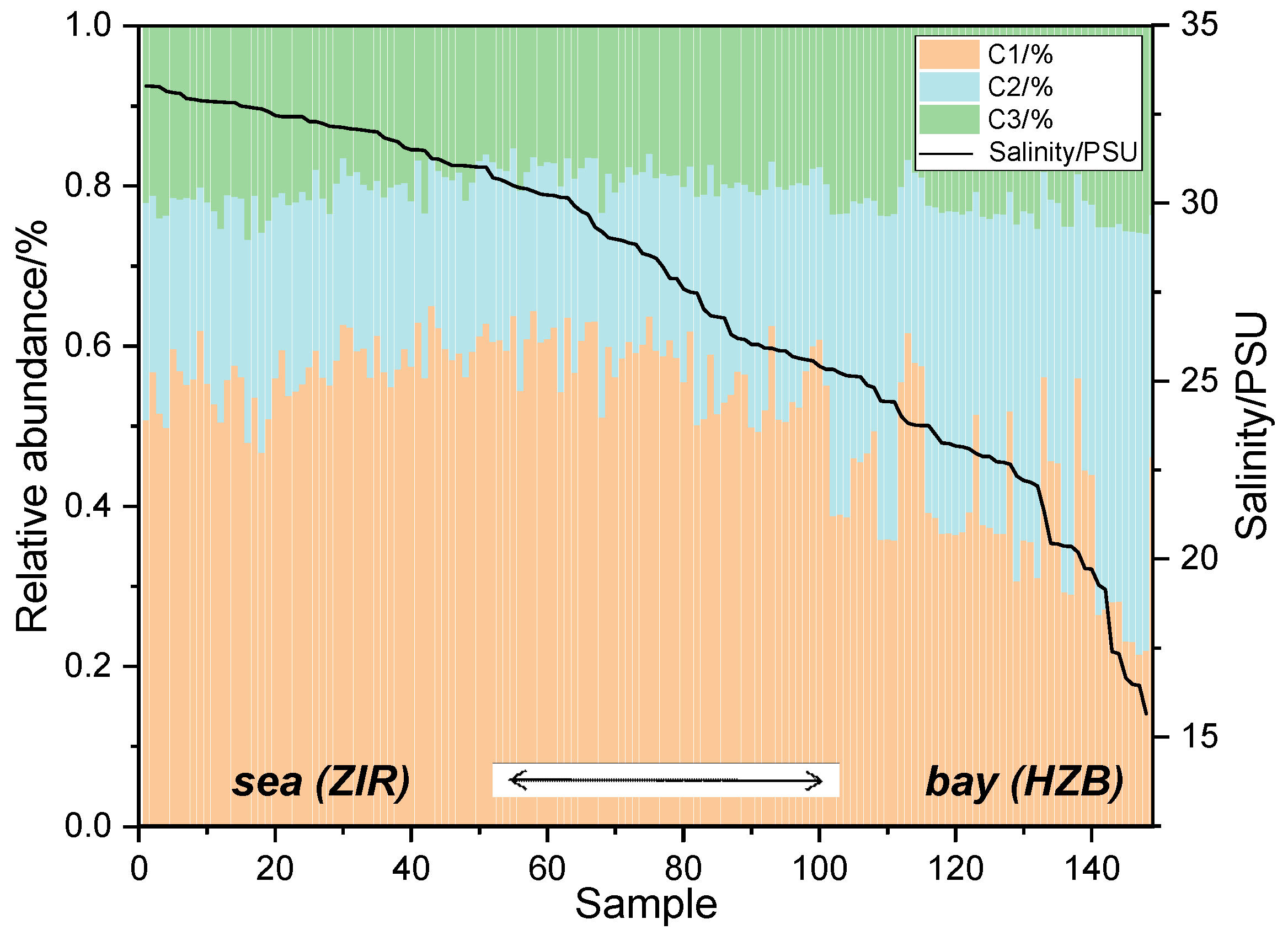

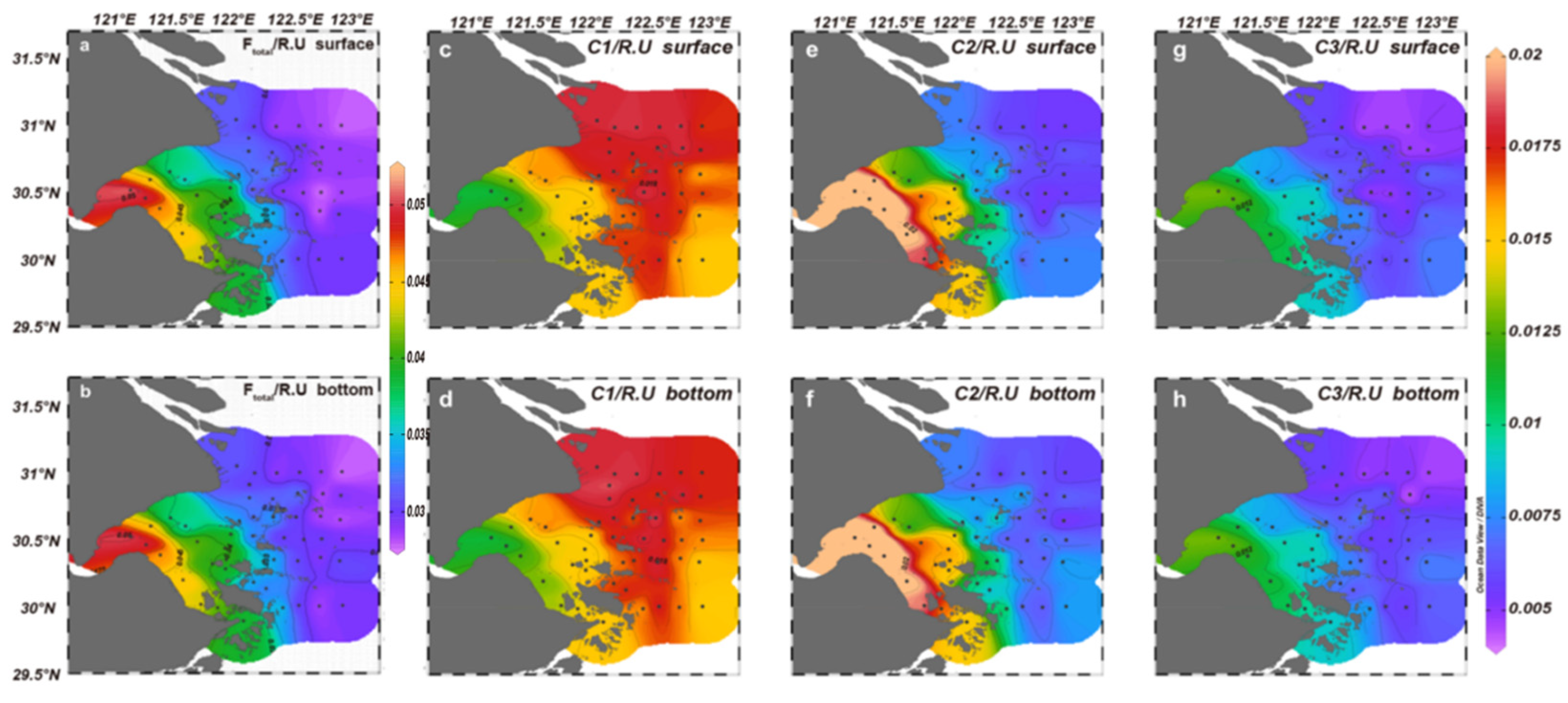

2.3.3. PARAFAC Analysis Results

3. Discussion

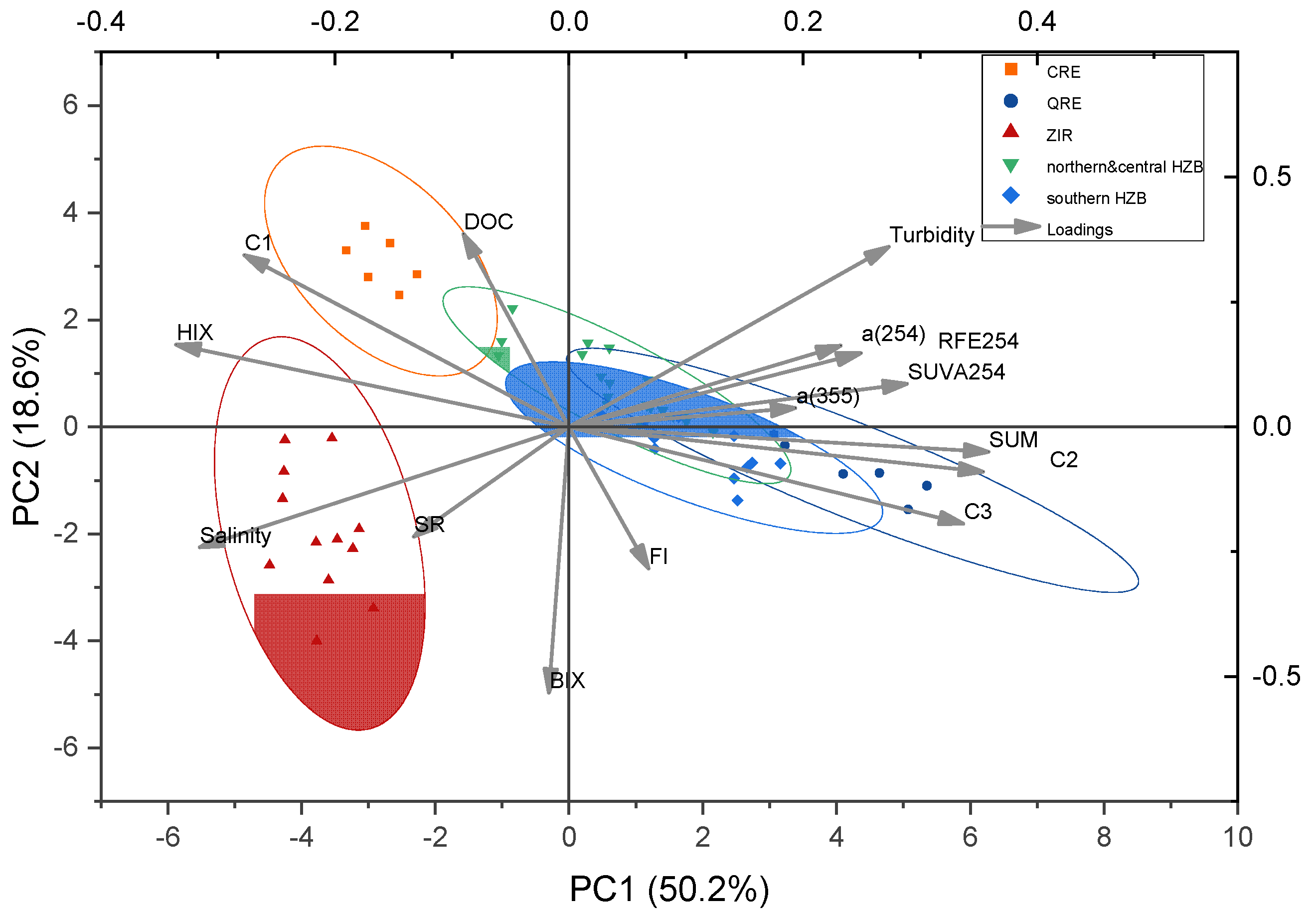

3.1. Composition and Characteristics of DOM in HZB and Adjacent Seas

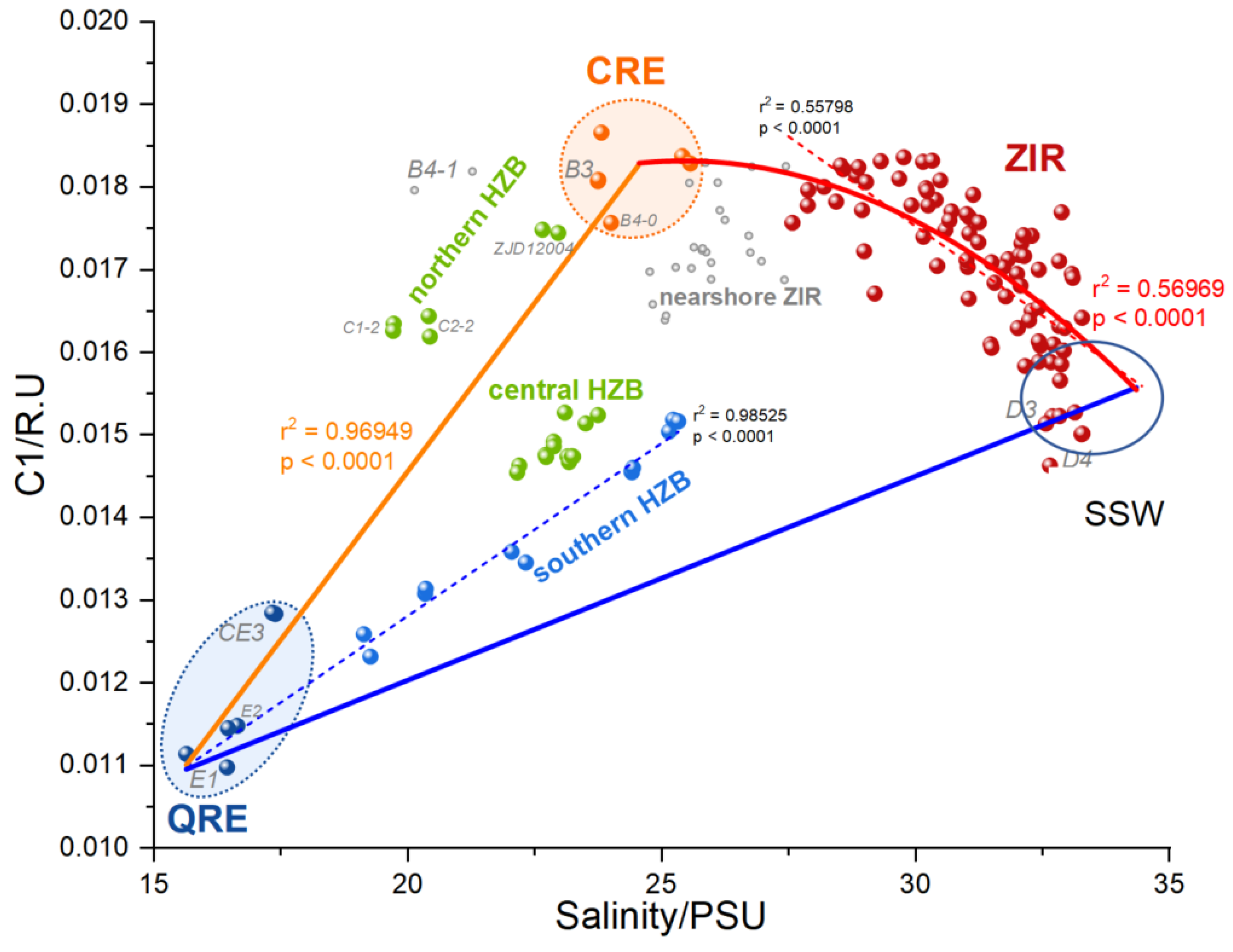

3.2. Sources of DOM in HZB

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Area and Sampling Sites

4.2. Sample Collection

4.3. DOC Concentration Analysis

4.4. CDOM and FDOM Optical Analyses

4.4.1. CDOM Analysis: Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) Absorbance

4.4.2. FDOM Analysis: Fluorescence Excitation Emission Matrices (EEMs)

2.4.3 The 3D Fluorescence - PARAFAC Analysis

4.5. Statistical Analyses

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DOM | Dissolved Organic Matter |

| CDOM | Chromophoric dissolved organic matter |

| FDOM | Fluorescent dissolved organic matter |

| DOC | Dissolved organic carbon |

| TSM | The total suspended matter |

| HZB | Hangzhou Bay |

| QRE | Qiantang River Estuary |

| CRE | Changjiang River Estuary |

| ZIR | Zhoushan Islands region |

| ECS | East China Sea |

| QTW | Qiantang Estuary water |

| CDW | Changjiang Diluted Water |

| SSW | Shelf seawater |

| FI | The fluorescence index |

| HIX | The humification index |

| BIX | The biological index |

| EEMs | Excitation emission matrices |

| PARAFAC | Parallel factor analysis |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

References

- Hajima, T.; Kawamiya, M.; Ito, A.; Tachiiri, K.; Jones, C. D.; Arora, V.; Brovkin, V.; Séférian, R.; Liddicoat, S.; Friedlingstein, P.; Shevliakova, E. Consistency of global carbon budget between concentration- and emission-driven historical experiments simulated by CMIP6 Earth system models and suggestions for improved simulation of CO2 concentration. Biogeosciences 2025, 22, 1447–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, J. E.; Cai, W.; Raymond, P. A.; Bianchi, T. S.; Hopkinson, C. S.; Regnier, P. A. G. The changing carbon cycle of the coastal ocean. Nature 2013, 504, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, W. Estuarine and Coastal Ocean Carbon Paradox: CO2 Sinks or Sites of Terrestrial Carbon Incineration. In Annual Review of Marine Science, Carlson, C. A.; Giovannoni, S. J., Eds. 2011; Vol. 3, p 123.

- Dai, M.; Su, J.; Zhao, Y.; Hofmann, E. E.; Cao, Z.; Cai, W.; Gan, J.; Lacroix, F.; Laruelle, G. G.; Meng, F.; Mueller, J. D.; Regnier, P. A. G.; Wang, G.; Wang, Z. Carbon fluxes in the coastal ocean: synthesis, boundary processes, and future trends. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 2022, 50, 593–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetzel, R. G. Death, detritus, and energy-flow in aquatic ecosystems. Freshwater Biology 1995, 33, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zigah, P. K.; McNichol, A. P.; Xu, L.; Johnson, C.; Santinelli, C.; Karl, D. M.; Repeta, D. J. Allochthonous sources and dynamic cycling of ocean dissolved organic carbon revealed by carbon isotopes. Geophysical Research Letters 2017, 44, 2407–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Z.; He, H.; Lurling, M.; Chen, M.; Zhang, Y. Composition of dissolved organic matter controls interactions with La and Al ions: Implications for phosphorus immobilization in eutrophic lakes. Environmental Pollution 2019, 248, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubbins, A.; Spencer, R. G. M.; Chen, H.; Hatcher, P. G.; Mopper, K.; Hernes, P. J.; Mwamba, V. L.; Mangangu, A. M.; Wabakanghanzi, J. N.; Six, J. Illuminated darkness: Molecular signatures of Congo River dissolved organic matter and its photochemical alteration as revealed by ultrahigh precision mass spectrometry. Limnology and Oceanography 2010, 55, 1467–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernes, P. J.; Benner, R. Photochemical and microbial degradation of dissolved lignin phenols: Implications for the fate of terrigenous dissolved organic matter in marine environments. Journal of Geophysical Research-Oceans 2003, 108, (C9).

- Repeta, D. J. Chemical Characterization and Cycling of Dissolved Organic Matter. 2015; p 21-63.

- Hansell, D. A.; Carlson, C. A. Biogeochemistry of Marine Dissolved Organic Matter, 2nd Edition. 2015.

- Hansen, A. M.; Kraus, T. E. C.; Pellerin, B. A.; Fleck, J. A.; Downing, B. D.; Bergamaschi, B. A. Optical properties of dissolved organic matter (DOM): Effects of biological and photolytic degradation. Limnology and Oceanography 2016, 61, 1015–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coble, P. G. Characterization of marine and terrestrial DOM in seawater using excitation-emission matrix spectroscopy. Marine Chemistry 1996, 51, 325–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stedmon, C. A.; Bro, R. Characterizing dissolved organic matter fluorescence with parallel factor analysis: a tutorial. Limnology and Oceanography-Methods 2008, 6, 572–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, Y.; Yao, X.; Ding, W.; Zhang, Y.; Jeppesen, E.; Zhang, Y.; Podgorski, D. C.; Chen, C.; Ding, Y.; Wu, H.; Spencer, R. G. M. Response of chromophoric dissolved organic matter dynamics to tidal oscillations and anthropogenic disturbances in a large subtropical estuary. Science of The Total Environment 2019, 662, 769–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Liang, S.; Wang, X.; Pan, X. Distribution and dynamics of dissolved organic matter in the Changjiang Estuary and adjacent sea. Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences 2021, 126, e2020JG006161.

- Zhao, C.; Zhou, Y.; Pang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, W.; Wang, Y.; He, D. The optical and molecular signatures of DOM under the eutrophication status in a shallow, semi-enclosed coastal bay in southeast China. Science China Earth Sciences 2021, 64, 1090–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; He, D.; He, C.; Li, P.; Fan, D.; Wang, A.; Zhang, K.; Chen, B.; Zhao, C.; Wang, Y.; Shi, Q.; Sun, Y. Spatial changes in molecular composition of dissolved organic matter in the Yangtze River Estuary: Implications for the seaward transport of estuarine DOM. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 759, 143531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Chen, X.; Chen, Z. L.; Zhu, P.; Huang, Z.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, L.; He, D. Unraveling the impact of Spartina alterniflora invasion on greenhouse gas production and emissions in coastal saltmarshes: New insights from dissolved organic matter characteristics and surface-porewater interactions. Water Research 2024, 262, 122120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Liang, H.; Qu, F.; Han, Z.-s.; Shao, S.; Chang, H.; Li, G. Impact of dataset diversity on accuracy and sensitivity of parallel factor analysis model of dissolved organic matter fluorescence excitation-emission matrix. Scientific Reports 2015, 5, 10207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Nie, L.; Xi, B.; Gao, H.; Yang, F.; Yu, H. A novel-approach for identifying sources of fluvial DOM using fluorescence spectroscopy and machine learning model. npj Clean Water 2024, 7, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Chen, J.; Wang, B.; Jin, H.; Shou, L.; Lin, H.; Miao, Y.; Sun, Q.; Jiang, Z.; Meng, Q.; Zeng, J.; Zhou, F.; Cai, W. Hypoxia Triggered by Expanding River Plume on the East China Sea Inner Shelf During Flood Years. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 2024, 129, e2024JC021299.

- Chen, C. T. A. Rare northward flow in the Taiwan Strait in winter: a note. Continental Shelf Research 2003, 23, (3-4), 387-391.

- Che, Y.; He, Q.; Lin, W. Q. The distributions of particulate heavy metals and its indication to the transfer of sediments in the Changjiang Estuary and Hangzhou Bay, China. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2003, 46, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, B.; Li, Y.; Li, D.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Chen, Q.; Huang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Zeng, J.; Zhou, F.; Jin, H.; Xu, J.; Chen, J. Influence of suspended particulate matters on P dynamics and eutrophication in the highly turbid estuary: A case study in Hangzhou Bay, China. Marine Pollution Bulletin 2024, 207, 116793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Chen, J.; Jin, H.; Li, H.; Ji, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, B.; Cao, Z.; Chen, Q. Tracing nitrate sources in one of the world’s largest eutrophicated bays (Hangzhou Bay): insights from nitrogen and oxygen isotopes. Acta Oceanologica Sinica 2024, 43, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, J.; Su, J.; Ren, F. Study on fluctuations of plume front and turbidity maximum in the Hangzhou Bay by remote sensing data. Acta Oceanologica Sinica 1993, (1), 51. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, F.; Ji, Z.; Wang, K.; Jin, H.; Loh, P. S. The Distribution of Sedimentary Organic Matter and Implication of Its Transfer from Changjiang Estuary to Hangzhou Bay, China. Open Journal of Marine Science 2016, 6, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Wang, C.; Xu, J.; Jiao, T.; Lin, Z. A review on the spectral analysis of marine organic matter. Marine Science Bulletin 2018, 37, 601–614. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Pérez, A. M.; Nieto-Cid, M.; Osterholz, H.; Catalá, T. S.; Reche, I.; Dittmar, T.; Álvarez-Salgado, X. A. Linking optical and molecular signatures of dissolved organic matter in the Mediterranean Sea. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 3436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stedmon, C. A.; Markager, S. Tracing the production and degradation of autochthonous fractions of dissolved organic matter by fluorescence analysis. Limnology and Oceanography 2005, 50, 1415–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Fang, Y.; Sun, X. Research progress of organic matter based on three-dimensional fluorescence spectroscopy-parallel factor analysis (EEM-PARAFAC). Water Purification Technology (in Chinese) 2022, 41, 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Cory, R. M.; McKnight, D. M. Fluorescence Spectroscopy Reveals Ubiquitous Presence of Oxidized and Reduced Quinones in Dissolved Organic Matter. Environmental Science & Technology 2005, 39, 8142–8149. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, N.; Baker, A.; Reynolds, D. Fluorescence analysis of dissolved organic matter in natural, waste and polluted waters—a review. River Research and Applications 2007, 23, 631–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downing, B. D.; Boss, E.; Bergamaschi, B. A.; Fleck, J. A.; Lionberger, M. A.; Ganju, N. K.; Schoellhamer, D. H.; Fujii, R. Quantifying fluxes and characterizing compositional changes of dissolved organic matter in aquatic systems in situ using combined acoustic and optical measurements. Limnology and Oceanography: Methods 2009, 7, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K. R.; Stedmon, C. A.; Wenig, P.; Bro, R. OpenFluor- An online spectral library of auto-fluorescence by organic compounds in the environment. Analytical Methods 2014, 6, 658–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whisenhant, E. A.; Zito, P.; Podgorski, D. C.; McKenna, A. M.; Redman, Z. C.; Tomco, P. L. Unique Molecular Features of Water-Soluble Photo-Oxidation Products among Refined Fuels, Crude Oil, and Herded Burnt Residue under High Latitude Conditions. ACS ES&T Water 2022, 2, 994–1002. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, H.; Guo, L. Variations in Colloidal DOM Composition with Molecular Weight within Individual Water Samples as Characterized by Flow Field-Flow Fractionation and EEM-PARAFAC Analysis. Environmental Science & Technology 2020, 54, 1657–1667. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.; Kim, S.-H.; Jung, H.-J.; Hyun, J.-H.; Choi, J. H.; Lee, H.-J.; Huh, I.-A.; Hur, J. Dynamics of dissolved organic matter in riverine sediments affected by weir impoundments: Production, benthic flux, and environmental implications. Water Research 2017, 121, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Andrilli, J.; Junker, J. R.; Smith, H. J.; Scholl, E. A.; Foreman, C. M. DOM composition alters ecosystem function during microbial processing of isolated sources. Biogeochemistry 2019, 142, 281–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helms, J. R.; Stubbins, A.; Ritchie, J. D.; Minor, E. C.; Kieber, D. J.; Mopper, K. Absorption spectral slopes and slope ratios as indicators of molecular weight, source, and photobleaching of chromophoric dissolved organic matter. Limnology and Oceanography 2008, 53, 955–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, D. M.; Boyer, E. W.; Westerhoff, P. K.; Doran, P. T.; Kulbe, T.; Andersen, D. T. Spectrofluorometric characterization of dissolved organic matter for indication of precursor organic material and aromaticity. Limnology and Oceanography 2001, 46, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohno, T. Fluorescence inner-filtering correction for determining the humification index of dissolved organic matter. Environmental Science & Technology 2002, 36, 742–746. [Google Scholar]

- Huguet, A.; Vacher, L.; Relexans, S.; Saubusse, S.; Froidefond, J. M.; Parlanti, E. Properties of fluorescent dissolved organic matter in the Gironde Estuary. Organic Geochemistry 2009, 40, 706–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, N.; Herndl, G. J.; Hansell, D. A.; Benner, R.; Kattner, G.; Wilhelm, S. W.; Kirchman, D. L.; Weinbauer, M. G.; Luo, T.; Chen, F.; Azam, F. Microbial production of recalcitrant dissolved organic matter: long-term carbon storage in the global ocean. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2010, 8, 593–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonborg, C.; Carreira, C.; Jickells, T.; Anton Alvarez-Salgado, X. Impacts of Global Change on Ocean Dissolved Organic Carbon (DOC) Cycling. Frontiers in Marine Science 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, P. M.; Seidel, M.; Ward, N. D.; Carpenter, E. J.; Gomes, H. R.; Niggemann, J.; Krusche, A. V.; Richey, J. E.; Yager, P. L.; Dittmar, T. Fate of the Amazon River dissolved organic matter in the tropical Atlantic Ocean. Global Biogeochemical Cycles 2015, 29, 677–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Song, G.; Xie, H. The apparent quantum yields of dissolved organic matter photobleaching and photomineralization in the Changjiang River Estuary. Haiyang Xuebao (in Chinese) 2016, 38, 120–129. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Shen, J.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, L. Characteristics of the Changjiang plume and its extension along the Jiangsu Coast. Continental Shelf Research 2014, 76, 108–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stedmon, C. A.; Seredynska-Sobecka, B.; Boe-Hansen, R.; Le Tallec, N.; Waul, C. K.; Arvin, E. A potential approach for monitoring drinking water quality from groundwater systems using organic matter fluorescence as an early warning for contamination events. Water Research 2011, 45, 6030–6038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benner, R.; Strom, M. A critical evaluation of the analytical blank associated with DOC measurements by high-temperature catalytic oxidation. Marine Chemistry 1993, 41, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegau, W. S.; Gray, D.; Zaneveld, J.; V. , R. Absorption and attenuation of visible and near-infrared light in water: dependence on temperature and salinity. Appl. Opt. 1997, 36, 6035–6046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Chen, L.; Zhang, W.; Huang, Q. Spatiotemporal distribution, sources, and photobleaching imprint of dissolved organic matter in the Yangtze Estuary and its adjacent sea using fluorescence and parallel factor analysis. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0130852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twardowski, M. S.; Boss, E.; Sullivan, J. M.; Donaghay, P. L. Modeling the spectral shape of absorption by chromophoric dissolved organic matter. Marine Chemistry 2004, 89, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traina, S. J.; Novak, J.; Smeck, N. E. An ultraviolet absorbance method of estimating the percent aromatic carbon content of humic acids. Journal of Environmental Quality 1990, 19, 151–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weishaar, J. L.; Aiken, G. R.; Bergamaschi, B. A.; Fram, M. S.; Fujii, R.; Mopper, K. Evaluation of specific ultraviolet absorbance as an indicator of the chemical composition and reactivity of dissolved organic carbon. Environmental Science & Technology 2003, 37, 4702–4708. [Google Scholar]

- Larsson, T.; Wedborg, M.; Turner, D. Correction of inner-filter effect in fluorescence excitation-emission matrix spectrometry using Raman scatter. Analytica Chimica Acta 2007, 583, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zepp, R. G.; Sheldon, W. M.; Moran, M. A. Dissolved organic fluorophores in southeastern US coastal waters: correction method for eliminating Rayleigh and Raman scattering peaks in excitation-emission matrices. Marine Chemistry 2004, 89, (1-4), 15-36.

- Lawaetz, A. J.; Stedmon, C. A. Fluorescence intensity calibration using the Raman scatter peak of water. Applied Spectroscopy 2009, 63, 936–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cory, R. M.; McNeill, K.; Cotner, J. P.; Amado, A.; Purcell, J. M.; Marshall, A. G. Singlet Oxygen in the Coupled Photochemical and Biochemical Oxidation of Dissolved Organic Matter. Environmental Science & Technology 2010, 44, 3683–3689. [Google Scholar]

| Water Masses | Temperature /℃ |

Salinity /PSU |

Turbidity /FTU |

TSM /mg·L-1 |

Chl-a /μg·L-1 |

DO /mg·L-1 |

pH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QTW | 7.0 ± 0.1 | 16.66 ± 0.59 | 492.42 ± 0.01 | (746 – 4616) | 4.40 ± 0.15 | 10.83 ± 0.08 | 6.87 ± 0.00 |

| CDW | 5.9 ± 0.1 | 24.39 ± 0.79 | 451.33 ± 50.25 | (256 – 1475) | 2.12 ± 0.50 | 10.76 ± 0.05 | 6.86 ± 0.01 |

| SSW | 10.2 ± 2.2 | 31.31 ± 1.80 | 5.44 - 293 | (6 – 1184) | 0.58 ± 0.18 (0.36 – 1.37) |

9.20 ± 0.61 (8.29 - 10.38) |

6.89 ± 0.03 (6.83 - 6.97) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).