1. Introduction

Ischemia-reperfusion injury can develop following the restoration of blood flow to tissues subjected to prolonged ischemia and may critically influence the outcome of free tissue transfers, composite tissue allotransplantations, and replantations.1 Ischemia and subsequent reperfusion trigger oxidative stress, causing cellular damage and toxic metabolite accumulation.2 In an excessive oxidative environment, ROS act as signaling molecules that drive inflammation.The infiltration of inflammatory cells and the subsequent release of cytokines further contribute to the pathophysiology of ischemia-reperfusion injury.3 Ischemia-reperfusion (I-R) injury is a major limitation in flap surgery, microvascular free tissue transfers, and composite tissue allotransplantation, despite the high success rates (90-95%) of modern reconstructive techniques. Reperfusion triggers a surge in ROS and inflammatory cytokines, worsening cellular damage, apoptosis, and vascular dysfunction.4 Several treatment methods and drug preparations have shown promising results in reducing I-R injury, but there is no commonly accepted treatment protocol due to the limitations in their use and the occurrence of systemic or local side effects.5-8

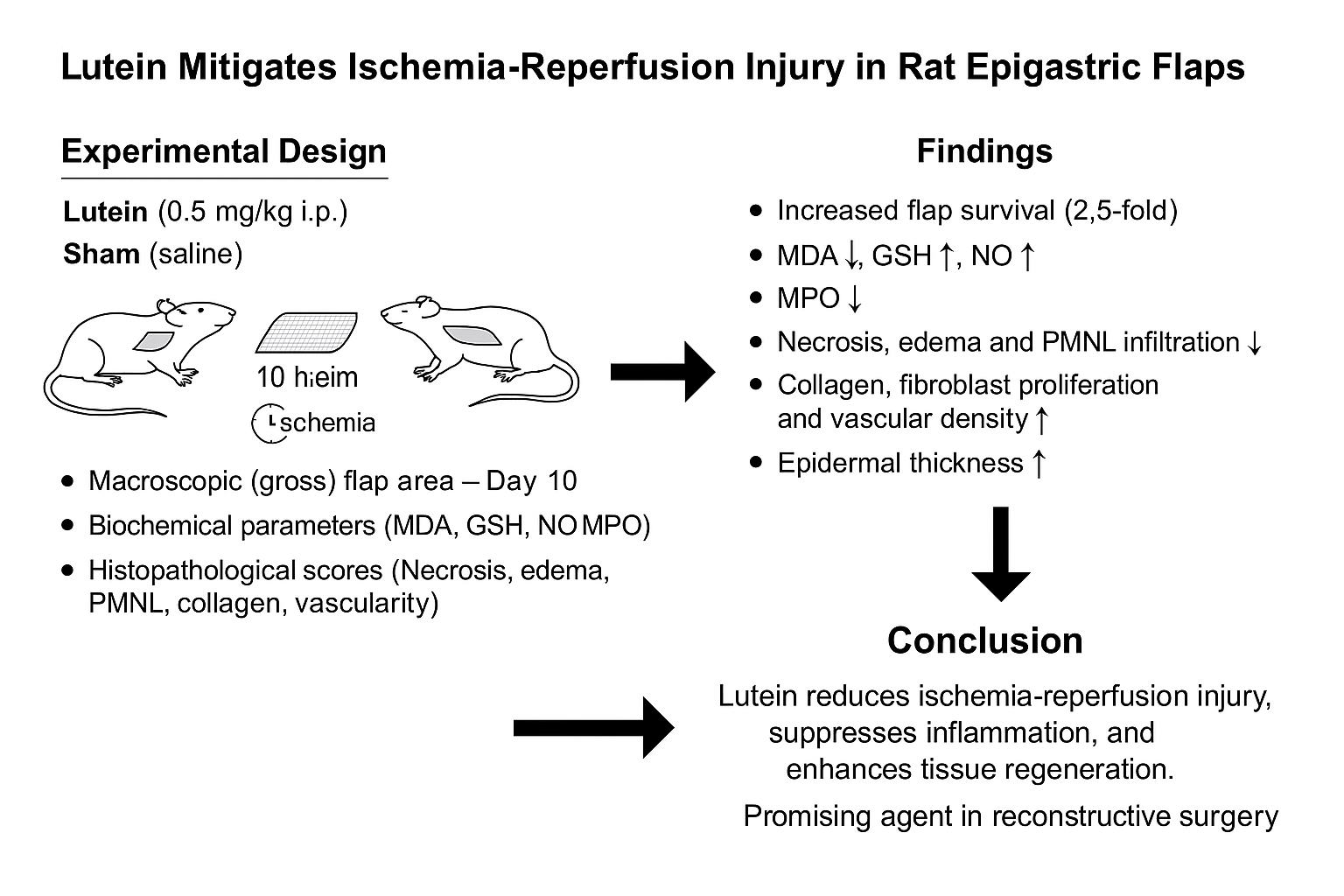

Lutein, a carotenoid produced by plants, bacteria, and algae, is not synthesized by the human body.9 This tetraterpenoid compound is abundantly found in green leafy vegetables, eggs, and various fruits.10 Due to its hydroxyl functional group, lutein interacts with free radicals, exhibiting strong antioxidant properties 11 Numerous studies have demonstrated its potential to mitigate oxidative stress.12-14 Additionally, lutein has been reported to exert anti-inflammatory effects and lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced macrophage inflammation.15-17 Lutein has been shown to exert cytoprotective effects via modulation of key redox-sensitive signaling pathways, such as the activation of the Nrf2/HO-1 axis and inhibition of NF-κB, which are central to antioxidant and anti-inflammatory responses in ischemic tissues. 16 Recent findings further suggest that lutein may confer protective effects against ischemic injury in both the small intestine 18 and the kidneys.19 However, despite its well-documented antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, no studies in the literature have investigated the effects of lutein on ischemia-reperfusion injury in flap tissue. Despite promising results, current pharmacological strategies for I-R injury in plastic surgery lack standardization due to systemic side effects and variable efficacy. Natural antioxidants have been explored as potential therapeutic agents. Lutein, a non-provitamin A carotenoid, has demonstrated potent antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties in various ischemic models but has never been evaluated in the context of reconstructive flap surgery.

Therefore, this study aims to investigate the effects of lutein on ischemia-reperfusion injury in a rat epigastric flap model, focusing on oxidative stress, inflammation, and tissue regeneration.

2. Materials and Methods

The sample size was determined by the biostatistics department to ensure statistical significance while minimizing the number of animal groups required. This study included sixteen male Sprague-Dawley rats, each weighing between 250 and 290 g. All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Gaziosmanpasa University (Ethical Approval No: 51879863-58/2024) and conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals.

3. Experimental Protocol

3.1. Characteristics of the Experimental Protocol

Sixteen male Sprague-Dawley rats (250-290 g) were randomly divided into two groups (n=8 each):

Lutein Group (LUT): Received 0.5 mg/kg intraperitoneal lutein (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) 60 minutes before ischemia.

Sham Group: Received an equal volume of saline.

A 6 × 4 cm² epigastric island flap was elevated, and ischemia was induced for 10 hours using an Acland V2 microvascular clamp

Oxidative stress markers: MDA, GSH, NO, MPO analyzed spectrophotometrically at 24 hours post-reperfusion)

Flap Survival: Measured 10 days post-surgery using ImageJ software by calculating viable flap area after excluding necrotic regions.

Histopathological parameters: Tissue damage and regeneration were assessed 10 days postoperatively.

3.2. Surgical Procedures

All surgical procedures were performed by the same surgeon (OA) for consistency. Anesthesia and analgesia were induced with intramuscular xylazine (15 mg/kg) and ketamine (50 mg/kg). The rats' abdominal and inguinal areas were shaved and disinfected with cetrimide and chlorhexidine gluconate. The animals were positioned supine on the operating table. A 6 × 4 cm² epigastric flap was marked following previous methods.20-22 In the Lutein (LUT) group, 0.5 mg/kg lutein was administered intraperitoneally 60 minutes before flap elevation. The flap was raised, including the subcutaneous tissue and superficial fascia, and the epigastric artery and vein were dissected and isolated. Ischemia was induced by applying an Acland V2 micro clamp to the vascular pedicle for 10 hours. (Figure 1) Afterward, circulation was restored, confirmed by peristalsis, temperature increase, and color change. The flap was repositioned and sutured using 4–0 polypropylene sutures. In the Sham group, an equivalent saline volume (0.5 mL) was administered, and the flap was elevated similarly, with no further intervention.

Figure 1. The epigastric artery and vein were isolated, and ischemia was induced by applying an Acland V2 micro clamp to the vascular pedicle for 10 hours.

Tissue samples (1×1 cm²) were collected from the same regions of all animals 24 hours after reperfusion for biochemical analysis. On day 10, animals were euthanized, and 1×1 cm samples were collected for histopathological analysis. Epidermal thickness was measured from five consistent points on all flaps.

3.3. Macroscopic Measurement of the Surviving Flap Area

Ten days postoperatively, photographs of the flaps were captured using a Canon EOS R5 camera positioned at a fixed distance of 25 cm. The viable flap area was then analyzed using the ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, USA). The total flap area was determined, and the necrotic portion was subtracted to calculate the surviving region.21 (Figure 2)

Figure 2. Macroscopic analysis of flap survival. a) Sham group, b) Lutein group. The surviving flap area was determined by ImageJ software, marking the viable area after measurement of the total flap area.

3.4. Biochemical and Histopathological Evaluation

3.4.1. Measurement of Tissue Lipid Peroxidation (MDA)

Lipid peroxidation in tissue samples (~100 mg) was assessed by quantifying malondialdehyde (MDA) levels, which serve as indicators of thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS).23 Tissue samples were treated with trichloroacetic acid and TBARS reagent, mixed, and incubated at 100 °C for 60 minutes. After cooling and centrifugation, absorbance at 535 nm was measured. MDA concentrations were determined using a standard curve and expressed as nmol/g protein.

3.4.2. Measurement of Tissue Protein Levels

The total protein content in tissue samples was quantified using the Bradford assay, with bovine serum albumin (BSA) serving as the reference standard. This colorimetric method relies on the binding of Coomassie Brilliant Blue dye to proteins, resulting in a measurable absorbance shift. The protein concentration was determined by comparing sample absorbance values to a standard calibration curve generated with known BSA concentrations.24

3.4.3. Measurement of Tissue Glutathione (GSH) Levels

The glutathione (GSH) concentration in tissue samples (~100 mg) was determined spectrophotometrically using Ellman’s assay. This method is based on the reaction between thiol groups and 5,5’-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB), resulting in the formation of a yellow-colored anion with a peak absorbance at 412 nm. The GSH levels were quantified by referencing a standard calibration curve and expressed as nmol/mg protein.25

3.4.4. Nitric Oxide Quantification in Tissue

Nitric oxide (NO) levels in tissue samples were assessed using a colorimetric assay based on the Griess reaction. Approximately 100 mg of tissue was collected from the distal region of the muscle and skin paddle 24 hours postoperatively. The assay was performed using a commercially available Nitric Oxide Assay Kit (Abcam), and absorbance was measured spectrophotometrically at 540 nm. NO concentrations were quantified against a standard curve and expressed as micromoles per milligram of tissue.21,22

3.4.5. Assessment of Myeloperoxidase (MPO) Activity

Tissue myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity was evaluated using a modified protocol based on the method described by Hillegas et al. 26Tissue samples were homogenized in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer and centrifuged. The pellet was resuspended in buffer with HTAB, followed by freeze-thaw cycles and sonication. After centrifugation, the supernatant was mixed with a reaction solution, and MPO activity was measured by absorbance change at 460 nm, expressed as U/g tissue.

3.4.6. Peripheral Neutrophil Count Analysis

Peripheral blood samples were collected 24 hours post-procedure for neutrophil assessment using Wright-Giemsa staining. Neutrophil counts were manually determined in five randomly selected high-power fields (200× magnification) per slide. The final circulating neutrophil count was calculated by multiplying the average neutrophil count per field by 1000, providing a standardized estimate of systemic neutrophil levels.21

3.4.7. Histopathological Evaluation

A full-thickness tissue sample, encompassing both viable and necrotic regions, was harvested from the flaps for histopathological evaluation (with all samples procured from a consistent anatomical site). After fixation in 10% buffered formalin for 24 hours, the specimens underwent standard paraffin embedding, and sections approximately 5 μm thick were obtained using a Leica RM2145 microtome (Germany). These sections were subsequently stained with hematoxylin and eosin as well as Mallory Azan. Evaluation of the stained sections was performed under a light microscope (Olympus BX-51 equipped with an Olympus C-5050 digital camera) to assess necrosis, edema, polymorphonuclear leukocyte (PMNL) infiltration, and vascularization, utilizing a modified Verhofstad scoring system (see Table 1).20,21,22,27 Additionally, Mallory Azan and Hematoxylin and Eosin-stained sections were analyzed using Image-Pro Express software (Version 6.0, Media Cybernetics, USA) to measure epidermal thickness, with all assessments performed by a blinded histopathologist, and the averages were calculated.20

For iNOS expression analysis, paraffin sections were deparaffinized in xylene and treated with 3% hydrogen peroxide. Antigen retrieval was performed using heat-induced epitope retrieval in sodium citrate buffer. Sections were incubated with a primary anti-iNOS antibody at 4°C for 24 hours, followed by detection using a secondary antibody and 3,3'-diaminobenzidine. Immunoreactivity was evaluated at 10× and 40× magnifications with an Olympus BX-51 microscope. (Figure 3 & Figure 4)

Figure 3. Histopathological examination of the two groups. a. Sham group histopathological view, hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining, original magnification × 20 (black arrow: discolored collagen bundles; blue arrow: epidermal structure; *polymorphonuclear leukocyte [PMNL] infiltration). b. Sham group histopathological view, Mallory Azan (MA) staining, original magnification × 20 (black arrow: discolored collagen bundles; blue arrow: epidermal structure). c. Sham group anti-inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) staining, original magnification × 40 (red arrow: anti-iNOS [+] endothelial cell). d. Lutein group histopathological view, H&E staining, original magnification × 20 (black arrow: significant difference in collagen structure compared to the Lutein group; blue arrow: epidermal structure; Hf significantly different in hair follicle degeneration compared to the Lutein group). e. Lutein group histopathological view, MA staining, original magnification × 20 (black arrow: significant difference in collagen structure compared to the Lutein group; blue arrow: epidermal structure; Hf significantly different in hair follicle degeneration compared to the Lutein group). f. Lutein group anti-iNOS staining, original magnification × 40 (red arrow: anti-iNOS [+] endothelial cell).

Figure 4. Example of epidermal thickness measurements performed using Image-Pro Express software. a) Sham group, b) Lutein group. Five measurements of epidermal thickness were taken for each section.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (Version 21.0, IBM Corp., USA). Data normality was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Parametric data were analyzed using the independent t-test, while non-parametric data were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Results

Throughout the study, no mortality or complications were observed in the rats.

4.1. Flap Survival Area

Lutein significantly improved flap survival area compared to the Sham group (21.18 ± 0.88 cm² vs. 8.42 ± 1.15 cm², p < 0.05).(Table 2)

4.2. Biochemical Assessments

Lutein administration significantly reduced MDA (58.1 ± 8.6 vs. 132.4 ± 15.3 nmol/g, p < 0.01) and MPO activity (12.7 ± 2.3 vs. 29.1 ± 4.5 U/g, p < 0.05), indicating decreased oxidative stress and inflammation. Elevated GSH levels (3.1 ± 0.4 vs. 1.3 ± 0.6 nmol/g, p < 0.05) reflected enhanced antioxidant defense, while increased NO levels (53.3 ± 6.1 vs. 17.8 ± 2.5 µM/mg, p < 0.01) suggested improved endothelial function. A significant reduction in neutrophil count (15,200 ± 2,760 vs. 25,300 ± 1,440 cells/µL, p < 0.05) further supported the anti-inflammatory effects of lutein.(Table 3)

4.3. Histopathological Evaluation

Histopathological evaluation was performed on tissue samples from 16 subjects (n=8 per group, Sham and Lutein), assessing necrosis, oedema, PMNL and lymphocyte infiltration, collagen density, fibroblast proliferation, and vascular density. Scoring was conducted by a blinded histopathologist using a 0–3 scale. The Lutein group showed significantly lower scores for necrosis (0.12 ± 0.35 vs. 2.87 ± 0.35), oedema (0.25 ± 0.46 vs. 2.87 ± 0.35), and PMNL infiltration (0.75 ± 0.66 vs. 3.00 ± 0.00) compared to the Sham group (all p < 0.01), indicating reduced tissue damage and acute inflammation. Lymphocyte infiltration was higher in the Lutein group (1.87 ± 0.78 vs. 1.12 ± 0.59, p < 0.05), possibly reflecting an adaptive immune response.Tissue repair parameters were also significantly enhanced in the Lutein group, with increased collagen density (2.62 ± 0.48 vs. 0.50 ± 0.53), fibroblast proliferation (2.50 ± 0.53 vs. 0.37 ± 0.51), and vascular density (2.50 ± 0.75 vs. 0.25 ± 0.46; all p < 0.05), indicating improved regeneration and angiogenesis.(Table 4) Additionally, dermo-epidermal thickness was significantly greater in the Lutein group (54.31 ± 14.36 µm) than in the Sham group (13.04 ± 3.75 µm, p < 0.01), based on five measurements per section using both Mallory Azan and H&E staining. These findings support the protective and reparative effects of lutein treatment.(Table 5).

5. Discussion

Reconstructive surgery following trauma or cancer is essential for patient recovery and quality of life. However, flap necrosis remains a major complication, primarily due to impaired blood flow (arterial insufficiency or venous congestion) and reperfusion injury.28 Ischemia-reperfusion injury involves acute apoptosis, primarily triggered by leukocyte–endothelial interactions, ROS generation, and impaired microvascular perfusion.27 Neutrophils play a key role by producing ROS, releasing proteolytic enzymes, and promoting pro-inflammatory cytokines, leading to endothelial dysfunction and capillary blockage.29 Natural antioxidants help counteract oxidative stress by neutralizing free radicals and reducing tissue damage.30,31 Consequently, therapeutic strategies targeting ischemia-reperfusion injury have increasingly focused on the use of antioxidants, anticoagulants, anti-inflammatory agents, and anti-apoptotic compounds to mitigate tissue damage and improve clinical outcomes .32,33

Lutein (C40H56O2), a carotenoid classified within the xanthophyll group, is naturally abundant in various dietary sources, particularly dark green leafy vegetables and certain fruits..18 Extensive research has demonstrated that lutein exerts its biological effects primarily through its potent antioxidant activity, effectively reducing oxidative stress responses. Beyond its antioxidative properties, lutein has been reported to exhibit pharmacological activities, including anti-inflammatory and anticancer effects. 12,13,15,16,18 Numerous studies have demonstrated that lutein enhances endogenous antioxidant capacity across various tissues while simultaneously reducing lipid peroxidation. 9,13,14,,15,19,34 In our study, animals in the treatment group receiving lutein were subjected to ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury and administered lutein at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg via intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection 1 hour before reperfusion. The dosage was determined based on previously conducted studies.19,35

To achieve this, 6 × 4 cm epigastric flaps were surgically elevated in rats, followed by a comprehensive analysis that included biochemical, histopathological, and macroscopic evaluations after a 10-hour ischemic period. This methodology was implemented in accordance with the approach used in previous studies. 20,21,22,27,36 Although an intraperitoneal route was used, clinical application would require oral or topical delivery. A standardized 10-hour global ischemia was applied to all skin flaps. Biochemical analyses were conducted 24 hours post-reperfusion, when oxidative stress peaks. On day 10, histopathological evaluations—including necrosis, edema, PMNL and lymphocyte infiltration, collagen density, fibroblast proliferation, vascular density, and epidermal thickness—were assessed using the Verhofstad scoring system.20,27,36

Flap survival is a key factor in reconstructive surgery, with I/R injury posing a major limitation. In this study, lutein significantly improved flap survival area compared to the Sham group, indicating its protective effect against I/R-induced damage. Survival rates with lutein were also statistically higher than those observed in previous studies with edaravone, trimetazidine, and carnitine. Unlike synthetic agents, lutein is a natural carotenoid with a well-documented safety profile. 20-22 This finding suggests that lutein may possess a more potent protective effect against ischemia-reperfusion injury. Unlike edaravone and trimetazidine, which require pharmacological approval for clinical use, lutein is a naturally occurring carotenoid with a strong safety profile and is already widely consumed as a dietary supplement.

Oxidative stress is a key contributor to I/R injury. In this study, lutein significantly reduced MDA levels compared to the Sham group (p < 0.01), indicating strong antioxidant activity. This finding supports previous evidence that lutein mitigates oxidative stress by scavenging ROS and inhibiting lipid peroxidation..37,38 Similarly, MPO activity, a marker of neutrophil infiltration and oxidative stress, was significantly lower in the Lutein group compared to the Sham group, indicating that lutein reduces both oxidative stress and neutrophil-mediated tissue damage. In addition, neutrophil count was significantly lower in the Lutein group (15,200 ± 2,760 cells/µL) than in the Sham group (25,300 ± 1,440 cells/µL; p < 0.05), suggesting effective suppression of systemic inflammation. These findings are consistent with previous studies highlighting lutein's anti-inflammatory effects in conditions such as atherosclerosis and UV-induced skin inflammation.30,10 Lutein administration significantly increased GSH levels, an essential antioxidant, compared to the Sham group (p <0.05). This suggests that lutein enhances cellular resilience against oxidative stress by boosting antioxidant capacity, which is consistent with previous studies highlighting lutein’s role in upregulating endogenous antioxidant systems.39 A significant increase in NO levels was observed in the lutein-treated group compared to the Sham group (p <0.01). As a key regulator of vascular homeostasis and endothelial function, this elevation suggests that lutein may improve microvascular circulation and endothelial protection, ultimately enhancing flap survival.

Our findings are consistent with previous studies demonstrating the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of lutein in various tissues. For instance, Kim et al. 37 reported that lutein reduced oxidative stress and inflammation in liver and eye tissues, supporting our observations in flap tissue. Given its strong antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, lutein could be considered as an adjunctive treatment in reconstructive surgery, particularly for high-risk flaps or compromised vascular territories.

Histopathological evaluation of rat epigastric island flaps treated with lutein showed significant improvements in tissue survival and regeneration. Lutein reduced necrosis, edema, and PMNL infiltration, while enhancing collagen deposition, fibroblast proliferation, lymphocyte infiltration, and vascular density. These results suggest that lutein prevents oxidative damage and inflammation, promoting tissue healing and remodeling.These results are consistent with studies on other pharmacological agents used in ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury models.20-22 The significant reduction in necrosis (mean score: Lutein group vs. Sham group; p < 0.01) is particularly noteworthy.This reduction indicates that lutein plays a crucial role in preventing tissue damage induced by I/R. Similarly, edema was significantly lower in the Lutein group compared to the Sham group (p < 0.01). These findings highlight lutein’s ability to prevent cellular injury and maintain tissue integrity during reperfusion. These results are more consistent and pronounced compared to the protective effects observed with other agents such as Propionyl-L-carnitine and trimetazidine in I/R injury models.20,22 Additionally, PMNL infiltration, a marker of acute inflammatory response in I/R injury, was significantly reduced in the Lutein group compared to the Sham group (p < 0.01). This indicates that lutein plays a critical role in modulating the inflammatory cascade, thereby preventing further tissue damage during reperfusion and ischemia phases. 40 Interestingly, lymphocyte infiltration was slightly higher in the Lutein group compared to the Sham group (p < 0.05), which may suggest a potential adaptive immune response.While neutrophils are major players during the acute inflammation phase, lymphocytes, particularly T cells, are critical in the later stages of immune response and tissue repair. The increased lymphocyte infiltration observed in the Lutein group suggests that lutein may facilitate the transition from acute inflammation to a more regulated immune response aimed at healing. This is consistent with findings from other studies that highlight lutein’s role in modulating immune responses and promoting inflammation resolution.15,20,22,27,35,38 Moreover, collagen density, fibroblast proliferation, and vascular density were significantly higher in the Lutein group (p < 0.05) compared to the Sham group, confirming that lutein enhances tissue regeneration and angiogenesis.These findings support our previous studies on other antioxidants like Propionyl-L-carnitine and trimetazidine, which have demonstrated regenerative effects in ischemia-related tissues.20,22 Lutein’s ability to promote collagen synthesis and vascularization plays a critical role in the healing process following ischemic injury. Greater epidermal thickness (54.31 ± 14.36 μm vs. 13.04 ± 3.75 μm, p < 0.01), confirming accelerated tissue regeneration.

This increase in thickness suggests enhanced tissue remodeling and epithelial proliferation, key components of the healing and tissue repair process. These findings align with the observed effects of other pharmacological agents that promote tissue regeneration following I/R injury.20,36 The histopathological results strongly indicate that lutein significantly reduces I/R-induced tissue damage, suppresses inflammation, and promotes tissue regeneration in a rat epigastric island flap model. The reductions in necrosis, edema, and PMNL infiltration, along with increases in collagen density, fibroblast proliferation, and vascularization, highlight its protective effects. Increased lymphocyte infiltration suggests lutein may aid in transitioning from acute inflammation to healing. The observed increase in dermo-epidermal thickness further supports its role in tissue regeneration. In contrast, the Sham group showed significant epidermal thinning and localized loss. These findings suggest that lutein could be a promising therapeutic agent in reconstructive surgery, particularly for I/R injury. Future clinical trials are needed to evaluate its efficacy in humans.

This study has several limitations. First, the small sample size may limit the generalizability of the findings. Second, as the study was conducted in an animal model, further research is needed to confirm these results in humans. Finally, the long-term effects of lutein treatment were not evaluated, warranting future studies. Nevertheless, the results demonstrate that lutein administration significantly mitigates I/R injury in a rat epigastric island flap model, with protective effects seen in improved flap survival, reduced oxidative stress, decreased neutrophil infiltration, and enhanced tissue regeneration.

6. Conclusions

Lutein mitigates I-R injury in epigastric flaps by reducing oxidative stress, suppressing inflammation, and enhancing tissue regeneration. It may serve as a promising adjunct in flap surgery to improve tissue survival and reduce ischemic complications in high-risk patients. Future trials should assess lutein’s efficacy in human microvascular free tissue transfers, its role in preventing partial flap necrosis, and its potential in combination with established pharmacologic agents.

Author Contributions

Ovunc Akdemir, M.D.: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Atilla Eyuboglu, M.D.: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Methodology, Investigation. Emel Oyku Cetin, Ph.D.: Data Collection and Processing, Design, Writing – review & editing, Methodology. Yigit Uyanikgil, Ph.D.: Data Collection and Processing, Analysis and Interpretation, Writing – review & editing, Critical Review.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the Gaziosmanpasa University Ethical Committee (Study number #51879863-58/2024 and conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional/national research committee.

Data Availability

The data supporting this study will be made available upon request. There are no publicly available repositories for the data.

Acknowledgments

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Vedder, NB. Flap physiology. In: Mathes SJ, Hentz VR, eds. Mathes Plastic Surgery. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2006:483-506.

- Teng, D.; Hornberger, T.A. Optimal Temperature for Hypothermia Intervention in Mouse Model of Skeletal Muscle Ischemia Reperfusion Injury. Cell. Mol. Bioeng. 2011, 4, 717–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avci, G.; Kadioglu, H.; Sehirli, A.O.; Bozkurt, S.; Guclu, O.; Arslan, E.; Muratli, S.K. Curcumin Protects Against Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury in Rat Skeletal Muscle. J. Surg. Res. 2012, 172, e39–e46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrovics, L.; Nagy, T.; Hardi, P.; Bognar, L.; Pavlovics, G.; Tizedes, G.; Takacs, I.; Jancso, G. The effect of trimetazidine in reducing the ischemia-reperfusion injury in rat epigastric skin flaps. Clin. Hemorheol. Microcirc. 2018, 69, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardakani, M.R.; Al-Dam, A.; Rashad, A.; Moghadam, A.S. Effect of Systemic Antioxidant Allopurinol Therapy on Skin Flap Survival. 2017, 6, 54–61.

- Wang, W.Z.; Baynosa, R.C.; Zamboni, W.A. Update on Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury for the Plastic Surgeon. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2011, 128, 685e–692e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buemi, M.; Galeano, M.; Sturiale, A.; Ientile, R.; Crisafulli, C.; Parisi, A.; Catania, M.; Calapai, G.; Impal, P.; Aloisi, C.; et al. RECOMBINANT HUMAN ERYTHROPOIETIN STIMULATES ANGIOGENESIS AND HEALING OF ISCHEMIC SKIN WOUNDS. Shock 2004, 22, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong JP, Kwon H, Chung YK, Jung SH. The effect of hyperbaric oxygen on ischemia-reperfusion injury: an experimental study in a rat musculocutaneous flap. Ann Plast Surg. 2003;51(5):478-487.

- Krinsky, N.I.; Landrum, J.T.; Bone, R.A. BIOLOGIC MECHANISMS OF THE PROTECTIVE ROLE OF LUTEIN AND ZEAXANTHIN IN THE EYE. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2003, 23, 171–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommerburg O, Keunen JE, Bird AC, van Kuijk FJ. Fruits and vegetables that are sources for lutein and zeaxanthin: the macular pigment in human eyes. Br J Ophthalmol. 1998;82(8):907-910.

- Carpentier S, Knaus M, Suh M. Associations between lutein, zeaxanthin, and age-related macular degeneration: an overview. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2009;49(4):313-326.

- Li, S.-Y.; Fu, Z.-J.; Ma, H.; Jang, W.-C.; So, K.-F.; Wong, D.; Lo, A.C.Y. Effect of Lutein on Retinal Neurons and Oxidative Stress in a Model of Acute Retinal Ischemia/Reperfusion. Investig. Opthalmology Vis. Sci. 2009, 50, 836–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chucair, A.J.; Rotstein, N.P.; SanGiovanni, J.P.; During, A.; Chew, E.Y.; Politi, L.E. Lutein and Zeaxanthin Protect Photoreceptors from Apoptosis Induced by Oxidative Stress: Relation with Docosahexaenoic Acid. Investig. Opthalmology Vis. Sci. 2007, 48, 5168–5177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonocore G, Tei M, Perrone S. Lutein as protective agent against neonatal oxidative stress. JPNIM. 2014;3:e030244.

- Kim, J.E.; Leite, J.O.; Deogburn, R.; Smyth, J.A.; Clark, R.M.; Fernandez, M.L. A Lutein-Enriched Diet Prevents Cholesterol Accumulation and Decreases Oxidized LDL and Inflammatory Cytokines in the Aorta of Guinea Pigs, J. Nutr. 2011, 141, 1458–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim JH, Na HJ, Kim CK, et al. The non-provitamin A carotenoid, lutein, inhibits NF-kappaB-dependent gene expression through redox-based regulation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/PTEN/Akt and NF-kappaB-inducing kinase pathways: role of H(2)O(2) in NF-kappaB activation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;45(6):885-896.

- Oh, J.; Kim, J.H.; Park, J.G.; Yi, Y.-S.; Park, K.W.; Rho, H.S.; Lee, M.-S.; Yoo, J.W.; Kang, S.-H.; Hong, Y.D.; et al. Radical Scavenging Activity-Based and AP-1-Targeted Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Lutein in Macrophage-Like and Skin Keratinocytic Cells. Mediat. Inflamm. 2013, 2013, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.-G.; Qi, Z.-C.; Liu, W.-L.; Wang, W.-Z. Lutein protects against ischemia/reperfusion injury in rat kidneys. Mol. Med. Rep. 2014, 11, 2179–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, Y.; Kobayashi, M.; Itagaki, S.; Hirano, T.; Noda, T.; Mizuno, S.; Sugawara, M.; Iseki, K. Protective effect of lutein after ischemia-reperfusion in the small intestine. Food Chem. 2011, 127, 893–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akdemir, O.; Tatar, B.E.; Gökhan, A.; Şirin, C.; Çavuşoğlu, T.; Erbaş, O.; Uyanıkgil, Y.; Çetin, E.Ö.; Zhang, F.; Lineaweaver, W. Preventive effect of trimetazidine against ischemia-reperfusion injury in rat epigastric island flaps: an experimental study. Eur. J. Plast. Surg. 2020, 44, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdemi̇r, O.; Tatar, B.E.; UYANIKGİL, Y.; Erbaş, O.; Zhang, F.; Li̇neaweaver, W.C. Preventive Effect of Edaravone Against Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury in Rat Epigastric Island Flaps: An Experimental Study. 33. [CrossRef]

- Eyuboglu, A.A.; Akdemir, O.; Erbas, O.; Isken, M.T.; Zhang, F.; Lineaweaver, W.C. Propionyl-l-carnitine mitigates ischemia-reperfusion injury in rat epigastric island flaps. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janero, D.R. Malondialdehyde and thiobarbituric acid-reactivity as diagnostic indices of lipid peroxidation and peroxidative tissue injury. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1990, 9, 515–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradford, MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248-254.

- Ellman, G.L. Tissue sulfhydryl groups. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1959, 82, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillegass, L.; Griswold, D.; Brickson, B.; Albrightson-Winslow, C. Assessment of myeloperoxidase activity in whole rat kidney. J. Pharmacol. Methods 1990, 24, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdemir O, Hede Y, Zhang F, Lineaweaver WC, Arslan Z, Songur E. Effects of taurine on reperfusion injury. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2011;64(7):921-928.

- Kuroki, T.; Takekoshi, S.; Kitatani, K.; Kato, C.; Miyasaka, M.; Akamatsu, T. Protective Effect of Ebselen on Ischemia-reperfusion Injury in Epigastric Skin Flaps in Rats. Acta Histochem. ET Cytochem. 2022, 55, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutteridge, J.C.M.; Halliwell, B. Free Radicals and Antioxidants in the Year 2000: A Historical Look to the Future. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2006, 899, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Roche, L.; Mesta, F. Oxidative Stress as Key Player in Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (SARS-CoV) Infection. Arch. Med Res. 2020, 51, 384–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henricks PA, Nijkamp FP. Reactive oxygen species as mediators in asthma. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2001;14(6):409-420.

- MacNee, W. Oxidative stress and lung inflammation in airways disease. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2001, 429, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu J, Yang CF, Wasser S, et al. Protection of Salvia miltiorrhiza against aflatoxin-B1-induced hepatocarcinogenesis in Fischer 344 rats: dual mechanisms of antioxidant and detoxification. Int J Cancer. 2001;93(6):837-844.

- Stahl, W.; Sies, H. Bioactivity and protective effects of natural carotenoids. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Mol. Basis Dis. 2005, 1740, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, F.; Zhang, Q.; Yan, F.-F.; Wan, J.-F.; Lin, C.-S. Lutein protects against ischemia/reperfusion injury in rat skeletal muscle by modulating oxidative stress and inflammation. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2015, 37, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyid, M.; Tiftikcioglu, Y.; Erdem, M.; Akdemir, O.; Tatar, B.E.; Uyanıkgil, Y.; Ercan, G. The Effect of Ceruloplasmin Against Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury in Epigastric Island Flap in Rats. J. Surg. Res. 2021, 267, 627–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim JE, Clark RM, Park Y, Lee J, Fernandez ML. Lutein decreases oxidative stress and inflammation in liver and eyes of guinea pigs fed a hypercholesterolemic diet. Nutr Res. 2012;32(4):264-273.

- Zhou R, Liu W, Zhuang X, Song Z. Lutein prevents high glucose-induced oxidative stress and inflammation in retinal pigment epithelial cells. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018;46(4):1724-1735.

- Huang YS, Chang SJ, Chao YC, Chiang BL. The immunomodulatory effects of lutein on the murine model of atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128(7):1736-1745.

- Friedrichs J, Rauscher S, Stangl V, et al. Lutein and its effects on inflammatory processes. Biochimie. 2015;118:13-17.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).