Submitted:

22 April 2025

Posted:

22 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. State of the Art: Large Language Models (LLMs) and the Semantic Gap

3. Semiotic Foundations I: The Saussurean Sign and LLM Analysis

|

4. Semiotic Foundations II: The Peircean Sign and LLM Analysis

- The Immediate Object is the Object as the sign itself represents it; the idea or schema of the object evoked directly by the sign. It is internal to the sign system in a sense, representing the object’s characteristics as portrayed by the sign.

- The Dynamic Object is the actual object or state of affairs in reality that grounds the sign and the process of semiosis. It is the "really efficient but not immediately present object" ([21] [CP 8.343]) that determines the sign’s representation. This Dynamic Object exists independently of any single interpretation, providing the ultimate referential anchor.

- The Immediate Interpretant is the potential meaning or effect inherent in the sign itself, its ’interpretability’ before any specific act of interpretation.

- The Dynamic Interpretant is the actual effect produced by the sign on a specific interpreter in a specific instance—a thought, feeling, or action.

- The Final Interpretant represents the ultimate, converged-upon meaning or habit of interpretation that would be reached after sufficient investigation and consideration by an ideal community of inquirers. It is the ideal outcome of the semiotic process.

- Icons function through similarity or resemblance (e.g., a portrait resembles its subject, a diagram reflects structural relations).

- Indices function through a direct physical, causal, or existential connection (e.g., smoke is an index of fire, a pointing finger is an index of location, pronouns like ’this’ or ’here’ are indices pointing to elements in the context).

- Symbols function through convention, habit, or learned rule (e.g., most words in a language, mathematical symbols, traffic lights). The connection is arbitrary, similar to Saussure’s concept.

|

|

5. Synthesis: LLMs as Masters of Form, Disconnected from Meaning

- Lack of Conceptual Representation (The Missing Signified): LLMs do not possess internal structures that function equivalently to stable, abstract human concepts or the Saussurean signified. While their embedding vectors capture rich contextual and relational information about how tokens (signifiers) are used relative to each other, these representations remain fundamentally distributional rather than conceptual [19]. They do not encode abstract definitions, necessary and sufficient conditions, prototypical structures, or the rich network of causal and ontological relations that characterize human conceptual knowledge [36]. For instance, an LLM’s representation of "bird" is derived from how the token "bird" co-occurs with tokens like "fly," "nest," "wings," etc., but it lacks an underlying abstract concept of ’birdness’ that includes core properties (e.g., vertebrate, feathers, lays eggs) and allows for reasoning about atypical cases (e.g., penguins don’t fly but are still birds) based on conceptual structure rather than just statistical association. This lack of true conceptual representation severely hinders capabilities requiring deep semantic understanding, such as resolving complex ambiguities that rely on conceptual distinctions rather than surface context, performing nuanced analogical reasoning that involves mapping conceptual structures, interpreting metaphors beyond common usage patterns, and achieving robust compositional generalization where meanings of complex expressions are built systematically from the meanings of their parts [44]. Much of human commonsense reasoning depends heavily on this rich substrate of conceptual knowledge, explaining LLMs’ persistent fragility in this area [16].

- Lack of Referential Grounding (The Missing Dynamic Object): The symbols manipulated by LLMs are fundamentally ungrounded, lacking a systematic connection to the external world – the Peircean Dynamic Object – or even to perceptual experiences of it [7,8]. LLMs learn from vast datasets of text describing the world, but they do not learn from direct interaction with or perception of that world in the way humans do [35]. Their internal representations are thus correlations between signifiers, not representations anchored in non-linguistic reality. Even multimodal LLMs that process images or audio alongside text primarily learn cross-modal correlations rather than achieving deep conceptual grounding; the extent to which associating the signifier "cat" with images of cats imbues the model with the actual concept of a cat remains debatable [9,34]. This critical disconnection from the Dynamic Object is arguably the primary source of LLM unreliability. It prevents them from independently verifying factual claims against external reality, making them prone to generating confident falsehoods or "hallucinations" when statistical patterns deviate from factual states [10,11]. It limits their ability to adapt to novel real-world situations or contexts not adequately represented in their training data, as they lack a causal or physical model of the world to reason from. It also fundamentally restricts their capacity to resolve indexical expressions (like ’this’, ’that’, ’here’, ’now’) reliably, as these depend entirely on the specific, shared spatio-temporal context (the Dynamic Object) which the LLM cannot directly access [6]. Ultimately, the lack of referential grounding undermines the trustworthiness and applicability of LLMs in any scenario where connection to the actual state of the world is critical.

- Ungrounded Interpretation (The Superficial Interpretant): In the Peircean framework, the Interpretant represents the meaning-effect of a sign, ideally leading towards a more refined understanding or habit related to the Object. The outputs generated by LLMs, while superficially resembling interpretations or responses based on understanding, function differently. They are the result of an algorithmic process optimizing for the statistically most probable sequence of signifiers/representamens given the preceding sequence and the model’s training data [5]. This computational effect lacks the cognitive depth and referential grounding of a Peircean interpretant. For instance, when an LLM generates a step-by-step explanation for a reasoning problem (e.g., via chain-of-thought prompting; [43]), it is often replicating common explanatory patterns found in its training data rather than performing genuine logical deduction based on an understanding of the concepts (signifieds) or the situation (object) involved. The resulting "interpretant" is a plausible linguistic form, not necessarily the outcome of a valid meaning-making process grounded in the problem itself. This superficiality limits the potential for LLMs to engage in truly meaningful dialogue, where participants build shared understanding by generating interpretants grounded in shared concepts and references. It also contributes to the perception of LLMs as "stochastic parrots" [18], systems capable of intricate linguistic mimicry but devoid of the underlying intentional and interpretative processes that characterize genuine communication and thought. Their generated interpretants do not reliably refine understanding or converge towards truth about the Dynamic Object because the entire process remains within the closed system of symbolic correlations.

6. Introducing Large Semiosis Models (LSMs): Concept and Vision

-

Explicit Semiotic Modeling: At its heart, an LSM must possess an architecture that deliberately instantiates the relationships central to semiotic theory, rather than relying on these relationships to emerge implicitly from undifferentiated sequence modeling. This involves designing distinct computational components or representational layers corresponding to the Signifier/Representamen (e.g., token processing modules, possibly adapted LLM cores), the Signified/Interpretant (e.g., concept networks, dynamic meaning states), and the Object (e.g., world models, perceptual interfaces), along with explicit mechanisms governing their interaction. For example, instead of merely associating the token "cup" with "coffee" statistically, an LSM architecture might explicitly link the "cup" Representamen to a "Cup" Signified node in a conceptual graph, which in turn has defined relations like contains(Liquid), madeOf(Material), affords(Grasping, Drinking), and crucially, links this concept to potential instances in a world model or perceptual input (the Object).

- –

- Inferential Potential: This explicit modeling allows for inferences impossible or unreliable for standard LLMs. Consider the statement: "The porcelain cup fell off the shelf." An LLM might predict the next word is "broke" based on statistical co-occurrence. An LSM, however, could access the "Cup" Signified, retrieve the madeOf(Porcelain) property, access knowledge associated with "Porcelain" (e.g., isBrittle), consult a basic physics model linked to the "Object" component (gravity causes falling, impact transfers energy), and infer that breaking is a highly probable outcome based on this chain of explicitly modeled semiotic and physical relationships, not just word statistics. This enables reasoning about novel situations (e.g., a cup made of a new, fictional material described as flexible) where statistical patterns are absent but conceptual properties and physical principles still apply.

-

Integrated Grounding Mechanisms: LSMs must incorporate mechanisms that actively and continuously link symbolic representations to non-linguistic sources, thereby addressing the symbol grounding problem [7,8]. This grounding provides the necessary semantic anchor missing in LLMs. Key strategies include:

- –

- Perceptual Grounding: Direct integration with sensory data streams (vision, audio, etc.). Linguistic tokens like "red," "heavy," or "loud" would be dynamically associated with specific patterns of activation in perceptual processing modules analyzing real-time input. This moves beyond static text-image correlations. Inferential Potential: This enables understanding and reasoning about perceptually rich descriptions or instructions. An LLM struggles with "Pick up the slightly heavier of the two identical-looking cubes." An LSM with grounded perception (perhaps via simulated haptic feedback or visual analysis of micro-features correlated with weight) could potentially execute or reason about this task by linking the linguistic comparator "heavier" to actual perceived/simulated sensory data associated with the object referents.

- –

- Interactional/Embodied Grounding: Learning through active engagement with a physical or simulated environment. Associating linguistic commands ("push the button") with motor actions and their perceived consequences (light turns on) creates strong bidirectional grounding [35]. Inferential Potential: This is crucial for robotics and tasks requiring understanding of affordances and causal effects of actions. An LLM might generate plausible instructions for assembling furniture but cannot adapt if the user makes a mistake or encounters an unexpected physical issue. An interactionally grounded LSM could potentially observe the deviation (via perception), update its world model (Object state), understand the physical implications, and provide corrective, contextually relevant instructions based on the actual, unfolding physical situation. It could learn intuitive physics concepts (e.g., stability, friction) through interaction, enabling predictions about physical scenarios not explicitly described in text.

- –

- Knowledge-Based Grounding: Systematically linking linguistic entities to structured representations in knowledge graphs or ontologies [41]. This provides explicit conceptual structure and factual constraints. Inferential Potential: Enables disambiguation and reasoning based on established world knowledge. An LLM might confuse two historical figures named "John Smith" if mentioned closely. An LSM grounded in a knowledge graph could distinguish them by linking each mention to distinct nodes representing individuals with different properties (birth dates, professions, known associates), resolving the ambiguity using explicitly represented knowledge about the distinct "Objects" (the individuals). It could also perform complex multi-hop reasoning over the knowledge graph, guided by linguistic queries, that goes beyond simple fact retrieval.

- –

- Internal World Modeling: Maintaining a dynamic, internal representation of the relevant environment, situation, or domain (the Object state), updated through perception, interaction, or inference [38]. Inferential Potential: This allows for tracking state changes over time and reasoning about hypothetical or future states. An LLM struggles to maintain consistency in long dialogues involving changing object properties or locations. An LSM with an internal world model could interpret statements like "The cat is now on the mat" by updating the location attribute of the cat entity in its internal model. It could then answer questions like "Where was the cat five minutes ago?" by potentially accessing historical states or reasoning backward, enabling much more coherent and stateful interaction and planning capabilities.

-

Rich Meaning Representation (Signified/Interpretant): LSMs require internal representations that go beyond the distributional vectors of LLMs to capture the structure and nuances of concepts (Signified) and enable the generation of grounded, meaningful effects (Interpretants). Exploration areas include:

- –

- Neuro-Symbolic Integration: Combining neural networks’ pattern learning with symbolic logic’s explicit reasoning provides a pathway to represent both fuzzy statistical knowledge and crisp conceptual rules [52]. Inferential Potential: An LSM could use neural components to process perceptual input identifying objects and symbolic components to reason about their properties using formal logic (e.g., "If object X is fragile and force Y exceeds threshold Z, then object X breaks"). This allows for combining data-driven learning with verifiable, rule-based inference, crucial for safety-critical applications or tasks requiring explainable reasoning.

- –

- Structured Concept Spaces: Employing graph structures (learned or predefined) where nodes represent concepts and edges represent semantic relations (e.g., ISA, HASA, CAUSES). Inferential Potential: Facilitates deeper analogical reasoning (mapping relational structures between domains, e.g., understanding "an atom is like a solar system" by mapping the ’orbits’ relation) and compositional semantics (deriving the meaning of "transparent aluminum cup" from the properties of its components and modification rules) in a more systematic way than LLM embeddings typically allow [44].

- –

- Causal and Physical Representations: Incorporating modules that explicitly model causal relationships [45] or simplified physical dynamics. Inferential Potential: Enables genuine causal inference ("Why did the bridge collapse?") by consulting the causal model rather than just correlations, and allows for counterfactual reasoning ("What if the beam had been thicker?") by simulating alternatives based on the physical/causal model. This is critical for tasks like diagnosis, planning under uncertainty, and scientific hypothesis generation.

- –

- Dynamic Interpretant States: Designing the model’s core processing state to represent not just sequence context but a dynamic, grounded interpretation of the current situation, integrating linguistic input, world model state, and conceptual knowledge. Inferential Potential: This state would serve as the basis for more nuanced and contextually aware decision-making or generation. For example, the interpretation of the command "Be careful!" would depend heavily on this dynamic state – involving perception of hazards, understanding of potential consequences based on the world model, and accessing relevant concepts of danger – leading to contextually appropriate actions or responses far beyond simple textual association.

- Integrated Processing and Semiosis Loop: LSM architectures should facilitate cyclical information flow between components, enabling perception to inform interpretation, interpretation to guide action, and action to update the world state, which then influences subsequent perception and interpretation, mimicking Peircean semiosis. This contrasts with the typically linear, feed-forward processing of autoregressive LLMs. Inferential Potential: This continuous loop enables adaptive behavior, error correction, and learning from interaction in dynamic environments. Consider an LSM controlling a robot exploring a room. It perceives an object (Representamen: visual data), interprets it as a potential obstacle (Interpretant based on world model and concept of ’obstacle’), decides to navigate around it (Action), updates its internal map (Object state), and then perceives the new view (next Representamen), continuing the cycle. This tight integration allows for complex, goal-directed behavior and learning that adapts to unforeseen circumstances, far exceeding the capabilities of LLMs generating static plans based only on initial text prompts. It enables truly interactive learning and collaborative problem-solving [53].

- Reference, Intentionality, and Transparency (Aspirational Goals): While full realization is distant, the LSM principles aim towards these crucial aspects of intelligence. Explicit reference tracking becomes more feasible when symbols are grounded in world models or knowledge graphs, allowing the system (or an external observer) to verify what a symbol refers to. Proto-intentionality could emerge from goal-directed behavior driven by the interaction between grounded interpretations (Interpretants) and the world model (Object state), where actions are selected purposefully to achieve desired changes in the represented world. Transparency is enhanced because the modular nature, with explicit components for meaning, grounding, and world state, potentially allows for clearer debugging and explanation of the system’s reasoning process [54] compared to the monolithic opacity of end-to-end LLMs. Achieving even partial progress towards verifiable reference and interpretable, goal-directed processing based on grounded representations would constitute a major advance in AI trustworthiness and capability.

7. Potentialities and Applications of LSMs

- Enhanced Semantic Understanding and Robust Reasoning: Perhaps the most significant potentiality lies in achieving a deeper level of semantic comprehension. By linking signifiers/representamens to explicit conceptual representations (Signifieds) and grounding them in world models or perception (Objects), LSMs can move beyond surface-level pattern matching. This enables superior ambiguity resolution; for instance, the meaning of "bank" (river vs. financial institution) could be resolved not just by surrounding words but by consulting the LSM’s internal world model or knowledge base to determine the relevant context (e.g., is the discussion about geography or finance?). Similarly, understanding nuance, irony, and metaphor often requires accessing conceptual knowledge and world understanding that LLMs lack. An LSM could potentially interpret "My lawyer is a shark" not just as a common idiom but by mapping relevant conceptual properties (predatory, aggressive) from the ’shark’ concept onto the ’lawyer’ concept within a specific interactional context. Crucially, LSMs promise far more robust reasoning. Equipped with internal world models, causal representations, and potentially integrated symbolic logic modules, they could perform reliable commonsense reasoning (e.g., inferring that putting water in a sieve results in it flowing through, based on object properties and physical principles), causal inference (e.g., diagnosing a system failure by tracing causal chains within its model, not just correlating symptoms described in text; [45,46]), and counterfactual reasoning ("What would have happened if the temperature had been lower?"). This contrasts sharply with LLMs, whose reasoning is often brittle, susceptible to superficial changes in phrasing, and struggles with novel scenarios not explicitly covered by training data patterns [6,14,15]. LSMs could reason about the world, not just from textual descriptions of it.

- Improved Reliability, Trustworthiness, and Factuality: The pervasive issue of hallucination in LLMs [10,11] stems directly from their lack of grounding. LSMs offer potential solutions by design. Grounding mechanisms provide pathways for verification. An LSM asked about the capital of France could potentially verify the answer ("Paris") by cross-referencing its internal knowledge base (knowledge-based grounding) or even, in principle, accessing external, trusted data sources linked to its Object representation layer. Perceptual grounding allows verification against observed reality; an embodied LSM describing a room could ground its statements in its actual visual input. Furthermore, the internal world model enables consistency checking. If an LSM asserts "Object A is inside Box B" and later asserts "Object A is on Table C" without describing a transfer action, its internal world model would register an inconsistency, potentially triggering clarification requests or self-correction, unlike LLMs which can easily contradict themselves across turns. This inherent capacity for verification and consistency maintenance promises significantly higher factual reliability. This is critical for deploying AI in high-stakes domains such as medicine (diagnostics, treatment information), finance (market analysis, advice), legal research, journalism, and education, where the cost of inaccurate or fabricated information generated by current LLMs is unacceptably high [55]. LSMs could become trustworthy sources of information and analysis precisely because their knowledge is structured, grounded, and internally consistent.

- Meaningful Human-AI Interaction and Collaboration: LSMs have the potential to revolutionize human-AI interaction, moving beyond the often stilted and error-prone exchanges with current chatbots. By maintaining a grounded understanding of the shared context (e.g., the state of a collaborative task, the physical environment in robotics, the concepts discussed), LSMs can engage in far more natural and fluid dialogue. The ability to robustly resolve indexical references ("put this block on that one," "referring to her earlier point") becomes feasible when symbols are linked to specific entities or locations within the shared Object representation (internal world model or perceived reality). This allows for seamless integration of language with non-linguistic cues like pointing gestures in embodied systems. LSMs could become true collaborative partners, capable of understanding user intentions not just from literal text but inferred from the shared context and task goals represented internally. They could proactively ask clarifying questions based on their world model ("Do you mean the large red block or the small one?"), offer relevant suggestions grounded in the current situation, and maintain coherent memory of the interaction history tied to evolving states of the world or task. This contrasts with the limitations of LLMs, which often struggle with long context windows, frequently misunderstand pragmatic intent, and lack the shared situational awareness necessary for deep collaboration [5]. LSMs could enable interfaces where language is used naturally to interact with complex systems or engage in joint problem-solving grounded in a shared reality.

- Advanced Robotics and Embodied AI: The realization of truly capable and adaptable robots operating in unstructured human environments hinges on abilities that LSMs are designed to provide. Embodied grounding through perception and interaction is non-negotiable for robotics. An LSM controlling a robot could connect linguistic commands like "Carefully pick up the fragile glass" directly to perceptual input (recognizing the object, assessing its likely fragility based on visual cues or prior knowledge linked to the ’glass’ concept) and appropriate motor control strategies (adjusting grip force). It could understand complex spatial relations ("behind," "underneath," "between") by grounding these terms in its internal spatial representation derived from sensors. The semiosis loop (perception -> interpretation -> action -> updated world state -> perception) becomes the core operational cycle. This enables robots to learn from interaction, adapting their understanding of objects and their own capabilities based on experience (e.g., learning that a specific surface is slippery after detecting slippage). They could potentially handle novel objects by inferring affordances based on perceived shape, material (linked to grounded concepts), and basic physical reasoning. This vision far surpasses the capabilities of robots controlled by LLMs generating static plans from text; LSM-powered robots could dynamically adapt plans based on real-time perception and a continuously updated understanding of the physical world (the Dynamic Object), leading to more robust, flexible, and useful robotic assistants in homes, hospitals, and industries.

- Accelerated Scientific Discovery and Complex Problem Solving: The ability of LSMs to integrate diverse data types and reason based on grounded models holds immense potential for scientific research and complex problem-solving. LSMs could be designed to ingest and fuse information from heterogeneous sources – scientific literature (Representamens), experimental data (grounding in measurement Objects), simulation results (grounding in model Objects), and scientific imagery (perceptual grounding). By building internal models that represent not just statistical correlations but underlying mechanisms and causal relationships (grounded concepts and Object models), LSMs could assist researchers in formulating novel hypotheses. They could potentially design in silico experiments by manipulating their internal models or even suggest real-world experiments. Critically, they could interpret complex experimental results in the context of existing knowledge and their internal models, potentially identifying subtle patterns or inconsistencies missed by human researchers. Fields like drug discovery (modeling molecular interactions and predicting effects), materials science (designing novel materials with desired properties based on physical principles), climate modeling (integrating observational data and complex simulations), and systems biology (understanding intricate biological pathways) could benefit enormously from AI systems capable of this level of integrated, grounded reasoning [45]. Current LLMs can retrieve information from papers but struggle to synthesize it meaningfully or perform novel reasoning grounded in the underlying scientific principles or data.

- Safer and More Interpretable AI: While safety and interpretability remain profound challenges for any advanced AI, the architectural principles of LSMs offer potential advantages over monolithic LLMs. Grounding provides constraints: an AI whose actions are tied to a verifiable internal world model or knowledge base might be less likely to engage in undesirable behavior stemming from purely statistical extrapolation. Rules and constraints could potentially be encoded within the conceptual (Signified) or world model (Object) layers. Furthermore, the envisioned modularity of LSMs—with distinct components for processing signs, representing concepts, modeling the world, and handling grounding—could enhance interpretability. It might become possible to probe the system’s internal world state, inspect the conceptual knowledge being activated, or trace how a particular interpretation (Interpretant) was derived from specific inputs and model components [54]. This contrasts with the often opaque, end-to-end nature of LLMs, where understanding the "reasoning" behind an output is notoriously difficult (the ’black box’ problem). While not a complete solution, this potential for greater transparency could facilitate debugging, identifying failure modes, building trust, and ultimately contribute to developing AI systems that are more aligned with human values and intentions [16].

8. Implementation Pathway I: A Saussurean-Inspired LSM

Conceptual Architecture

- 1.

- Signifier Processing Component (SPC): This component would be responsible for processing the raw linguistic input and generating linguistic output, leveraging the proven strengths of existing LLM technology. It could be implemented using a pre-trained Transformer-based LLM (e.g., variants of GPT, Llama, Gemini) as its core engine. The SPC’s primary function remains the modeling of sequential dependencies and distributional patterns among tokens (Signifiers), capturing the Saussurean langue as represented in text. However, unlike a standard LLM, its internal representations (e.g., token embeddings, hidden states) would be designed to interface directly with the Signified component.

- 2.

-

Signified Representation Component (SRC): This component represents the core innovation of this pathway, designed to explicitly store and structure conceptual knowledge, embodying the Saussurean Signifieds. Several implementation strategies could be explored for the SRC, each with distinct advantages and disadvantages:

- Structured Knowledge Bases (KBs): Utilizing large-scale, curated knowledge graphs like Wikidata, ConceptNet, Cyc, or domain-specific ontologies (e.g., SNOMED CT in medicine). In this approach, Signifieds are represented as nodes (entities, concepts) interconnected by labeled edges representing semantic relations (ISA, HASA, RelatedTo, AntonymOf, etc.). This offers high interpretability, explicit relational structure, and allows leveraging vast amounts of curated human knowledge. Challenges include coverage limitations (KBs are never complete), integration complexity with neural models, potential rigidity, and maintaining consistency.

- Learned Conceptual Embedding Spaces: Creating a dedicated vector space where embeddings represent concepts (Signifieds) rather than just token distributions (Signifiers). These conceptual embeddings could be learned jointly during training or derived from structured KBs using graph embedding techniques (e.g., TransE, GraphSAGE). This approach offers the flexibility and scalability of neural representations but potentially sacrifices the explicit structure and interpretability of symbolic KBs. Defining the appropriate structure and learning objectives for such a space is a key research challenge.

- Hybrid Neuro-Symbolic Representations: Combining elements of both approaches, perhaps using neural embeddings for concepts but constraining their relationships based on an ontological structure or logical rules [52]. This aims to balance flexibility with structure and explicit knowledge.

- 3.

-

Signifier-Signified Linking Mechanism (SSLM): This is arguably the most crucial and technically challenging component. The SSLM must establish a dynamic, bidirectional bridge between the representations generated by the SPC (contextualized token embeddings/hidden states) and the representations within the SRC (concept nodes/embeddings). Its function is to map instances of Signifiers encountered in the input text to their corresponding Signified representations in the SRC, and conversely, to allow activated Signifieds in the SRC to influence the generation of Signifiers by the SPC. Potential mechanisms include:

- Cross-Attention Mechanisms: Employing attention layers (similar to those within Transformers) that allow the SPC to "attend" to relevant concepts in the SRC when processing input tokens, and conversely, allow the SRC to attend to relevant textual context when activating concepts. This enables context-dependent mapping between signifiers and signifieds.

- Projection Layers and Shared Spaces: Training projection layers to map SPC hidden states into the SRC’s conceptual space (or vice-versa), potentially enforcing alignment through contrastive learning objectives that pull representations of related signifiers and signifieds closer together.

- Multi-Task Learning Frameworks: Training the entire system jointly on multiple objectives, including standard language modeling (predicting the next Signifier) and auxiliary tasks like predicting the correct Signified concept(s) associated with input tokens/phrases or generating text conditioned on specific input Signifieds from the SRC.

- Explicit Entity Linking / Concept Mapping Modules: Incorporating dedicated modules, potentially based on traditional NLP techniques or specialized neural networks, designed specifically to perform entity linking or concept mapping between mentions in the text (Signifiers) and entries in the SRC (Signifieds).

Training Methodologies

- Joint Training: Training the SPC and SRC components simultaneously, possibly with a shared objective function that includes both language modeling loss (predicting Signifiers) and a concept alignment loss (e.g., maximizing similarity between SPC representations of a word and SRC representation of its linked concept, using datasets annotated with word-concept links like WordNet or KB entity links).

- Pre-training followed by Alignment: Pre-training the SPC (LLM core) and potentially pre-training the SRC (e.g., graph embeddings on a KB) separately, followed by a dedicated alignment phase focusing on learning the SSLM parameters using aligned text-concept data.

- Data Requirements: Training would benefit significantly from large datasets where textual mentions are explicitly linked to concepts in a target knowledge base or ontology. Resources like Wikipedia (with its internal links and connections to Wikidata), annotated corpora, or large-scale dictionaries/thesauri could be leveraged. Generating pseudo-aligned data might also be explored.

- Concept-Conditioned Generation: Training the model not only to predict text but also to generate text that accurately reflects or elaborates on specific input concepts provided from the SRC. This forces the model to learn the mapping from Signified back to appropriate Signifiers.

Operational Flow

- Input Processing: Input text (sequence of Signifiers) is processed by the SPC (LLM core).

- Conceptual Activation: As the SPC processes the input, the SSLM dynamically identifies key Signifiers and maps them to corresponding Signified representations within the SRC. This might involve activating specific nodes in a KB or producing context-dependent conceptual embeddings. The strength or relevance of activated concepts could be modulated by the textual context processed by the SPC.

- Conceptual Reasoning/Enrichment (Optional): Depending on the sophistication of the SRC, limited reasoning might occur within the conceptual layer itself (e.g., traversing relations in a KB to infer related concepts or properties not explicitly mentioned in the text). Activated concepts might also retrieve associated factual knowledge.

- Informed Generation: The activated conceptual representations in the SRC, along with the processed textual context from the SPC, jointly inform the generation of the output text. The SPC’s generation process would be modulated or constrained by the active Signifieds, ensuring the output is not only linguistically plausible but also conceptually coherent and potentially factually consistent with the activated knowledge. For instance, when generating text about a "penguin," the activated "Penguin" concept in the SRC (linked to properties like ISA(Bird), Habitat(Antarctic), Ability(Swim), Cannot(Fly)) could guide the SPC to produce relevant and accurate statements, potentially overriding purely statistical textual patterns that might incorrectly associate penguins with flying due to the general association between "bird" and "fly."

Limitations of This Pathway

- Indirect Grounding: The grounding achieved is primarily conceptual rather than referential or perceptual. The Signifieds within the SRC, especially if based on KBs or learned purely from text-aligned data, might themselves lack direct connection to the Peircean Dynamic Object (real-world referents or sensory experience). The system understands the concept of "red" as defined within its SRC (e.g., related to ’color,’ opposed to ’blue’), but it doesn’t perceive red in the world.

- Potential Brittleness of KBs: If relying heavily on curated KBs for the SRC, the system’s performance can be limited by the coverage, accuracy, and consistency of the KB itself. Integrating and updating massive KBs also poses significant engineering challenges.

- Abstractness: This approach is better suited for tasks involving abstract knowledge, factual recall, and conceptual reasoning than for tasks requiring direct interaction with a dynamic, physical environment or understanding based on real-time perception.

9. Implementation Pathway II: A Peircean-Inspired LSM

Conceptual Architecture

- 1.

-

Representamen Processing Component (RPC): Analogous to the SPC in the Saussurean pathway, this component handles the processing of sign vehicles. Given the Peircean emphasis on diverse sign types, the RPC must be inherently multimodal. It would likely incorporate:

- A powerful language processing core (e.g., an LLM architecture) for handling symbolic Representamens (text, speech).

- Sophisticated perception modules (e.g., Computer Vision networks like CNNs or Vision Transformers, audio processing networks) capable of extracting features and representations from sensory data, which also function as Representamens (specifically Icons and Indices derived from perception).

- Mechanisms for fusing information from different modalities, potentially using cross-attention or dedicated fusion layers. The RPC’s output would be rich, contextualized representations of the incoming signs, irrespective of their modality.

- 2.

-

Object Representation Component (ORC): This component is the cornerstone of the Peircean pathway, tasked with representing the Dynamic Object – the external reality or situation the signs refer to. This is the primary locus of grounding. Implementing the ORC is a major research challenge, likely involving a combination of approaches:

- Direct Perceptual Interface: Direct connections to sensors (cameras, microphones, LIDAR, tactile sensors) providing real-time data about the immediate environment. This data stream is the most direct representation of the Dynamic Object available to the system at any given moment.

- Simulation Engine Integration: For virtual agents, tight integration with a high-fidelity physics or environment simulator (e.g., Unity, Unreal Engine, Isaac Sim, MuJoCo). The state of the simulation serves as the Dynamic Object representation, allowing the LSM to interact with and observe the consequences of actions within a controlled, dynamic world.

-

Internal World Model: A dynamically maintained internal representation of the environment’s state, entities, properties, and relations, constructed and updated based on perceptual input, interaction history, and inferential processes. This model might employ various formalisms:

- –

- Scene Graphs: Representing objects, their properties (color, shape, location, pose), and spatial relationships in a structured graph format.

- –

- Factor Graphs or Probabilistic Models: Representing uncertain knowledge about the world state and enabling probabilistic inference.

- –

- State Vector Representations: Using embedding vectors to capture the state of objects or the entire environment, potentially learned end-to-end.

- –

- Knowledge Graphs (Dynamic): Employing knowledge graphs where nodes represent specific object instances and properties, with mechanisms for updating these based on new information or actions.

The ORC must be dynamic, capable of reflecting changes in the external world or simulation over time, either through direct updates from perception/simulation or through internal predictive modeling based on actions and physical laws.

- 3.

-

Interpretant Generation Component (IGC): This component is responsible for producing the meaning-effect (Interpretant) of a sign (Representamen) in the context of the current Object state as represented by the ORC. The Interpretant is not merely a textual output but represents the system’s situated understanding or disposition to act. Implementing the IGC might involve:

- Dynamic System State: Treating the overall activation state of the LSM’s internal network, influenced by RPC input and ORC context, as the substrate of the Dynamic Interpretant. Specific patterns of activation would correspond to different interpretations.

- Goal Representation Modules:* Translating interpreted inputs (e.g., linguistic commands, perceived goal states) into explicit internal goal representations that drive subsequent behavior.

- Grounded Reasoning Modules: Incorporating modules capable of performing inference directly over the representations within the ORC (world model) and integrated conceptual knowledge (potentially a sophisticated SRC from the Saussurean pathway, now grounded via the ORC). This could include causal reasoning engines [45], spatial reasoners, or physical simulators.

- Planning and Policy Modules: Utilizing techniques from AI planning or reinforcement learning to generate sequences of actions (motor commands, linguistic utterances) aimed at achieving goals derived from the Interpretant, considering the constraints and dynamics represented in the ORC.

- 4.

-

Semiosis Loop and Action Execution: The architecture must explicitly implement the cyclical flow of Peircean semiosis.

- Interpretation: The IGC generates an Interpretant based on input from the RPC (Representamen) and the current state of the ORC (Object).

- Action Selection: Based on the Interpretant (e.g., derived goal, situational assessment), an action is selected or generated (this could be a linguistic output generated via the RPC, or a motor command sent to actuators/simulation).

- Execution & Effect: The action is executed in the environment (real or simulated).

- Feedback/Observation: The consequences of the action on the Dynamic Object are observed via the perceptual interface or simulation feedback, leading to updates in the ORC.

- Iteration: This updated Object state then informs the interpretation of subsequent Representamens entering the RPC, closing the loop and allowing for continuous adaptation and learning.

Training Methodologies

- Reinforcement Learning (RL): RL is a natural fit for training the semiosis loop. The LSM agent receives rewards based on achieving goals, accurately predicting environment dynamics, successfully interpreting commands, or maintaining consistency between its internal model and observed reality. This allows the system to learn optimal policies for interpretation and action through trial-and-error interaction with its environment [53,56]. Intrinsic motivation objectives (e.g., curiosity-driven exploration) might also be crucial for learning rich world models.

- Imitation Learning / Behavioral Cloning: Training the LSM to mimic successful behaviors demonstrated by humans or expert systems within the target environment. This can bootstrap the learning process, especially for complex motor skills or interaction protocols.

- Self-Supervised Learning on Interaction Data: Leveraging the vast amount of data generated during interaction for self-supervised objectives. Examples include predicting future perceptual states given current state and action, learning inverse dynamics (predicting action needed to reach a state), ensuring cross-modal consistency (predicting textual description from visual input, or vice-versa), or learning affordances by observing interaction outcomes.

- Curriculum Learning: Gradually increasing the complexity of the environment, the tasks, or the required semiotic reasoning to facilitate stable learning, starting with simple object interactions and progressively moving towards more complex scenarios.

- Leveraging Pre-trained Components: While interaction is key, pre-trained models (e.g., vision encoders, LLM cores for the RPC) can provide valuable initial representations and accelerate learning, followed by extensive fine-tuning within the interactive loop.

Operational Flow

- Multimodal Input: Receives input via RPC (e.g., spoken command "Bring me the red apple from the table" + visual input of the scene).

- Grounded Perception & Object Update: RPC processes sensory data; ORC updates its internal world model (identifies objects like ’apple’, ’table’, notes their properties like ’red’, location).

- Representamen Grounding: Links linguistic Representamens ("red apple," "table") to specific entities identified within the ORC’s world model. Resolves indexicals based on perception and world state.

-

Interpretant Generation: IGC interprets the command in the context of the grounded world state, generating an internal goal (e.g., Goal: Possess(Agent, Object_Apple1) whereApple1.color=red AND Apple1.location=Table2).

- Planning/Action Selection: A planning module uses the goal and the ORC’s model (including physical constraints, affordances) to generate a sequence of motor actions (navigate to table, identify correct apple, grasp, return).

- Execution & Monitoring: Executes actions, continuously monitoring perceptual feedback via RPC/ORC to detect errors, confirm success, or adapt the plan dynamically if the world state changes unexpectedly (e.g., apple rolls).

- Goal Completion & Reporting: Upon successful execution, updates the ORC (agent now possesses apple) and potentially generates a linguistic Representamen via RPC ("Here is the red apple").

Advantages and Challenges

- Complexity: The architecture is significantly more complex than standard LLMs or even the Saussurean pathway, requiring tight integration of perception, language, reasoning, world modeling, and action components.

- World Modeling: Building accurate, scalable, and efficiently updatable world models (ORC) remains a major AI research frontier.

- Perception: Robust real-world perception is still challenging, susceptible to noise, occlusion, and ambiguity.

- Training: Training via RL in complex environments is notoriously data-hungry, computationally expensive, and can suffer from instability and exploration problems. Defining appropriate reward functions is difficult.

- Simulation Gap: Transferring models trained in simulation to the real world often faces challenges due to discrepancies between simulated and real physics/sensor data.

- Evaluation: Defining metrics to evaluate "grounded understanding" or the quality of the internal Interpretant remains difficult.

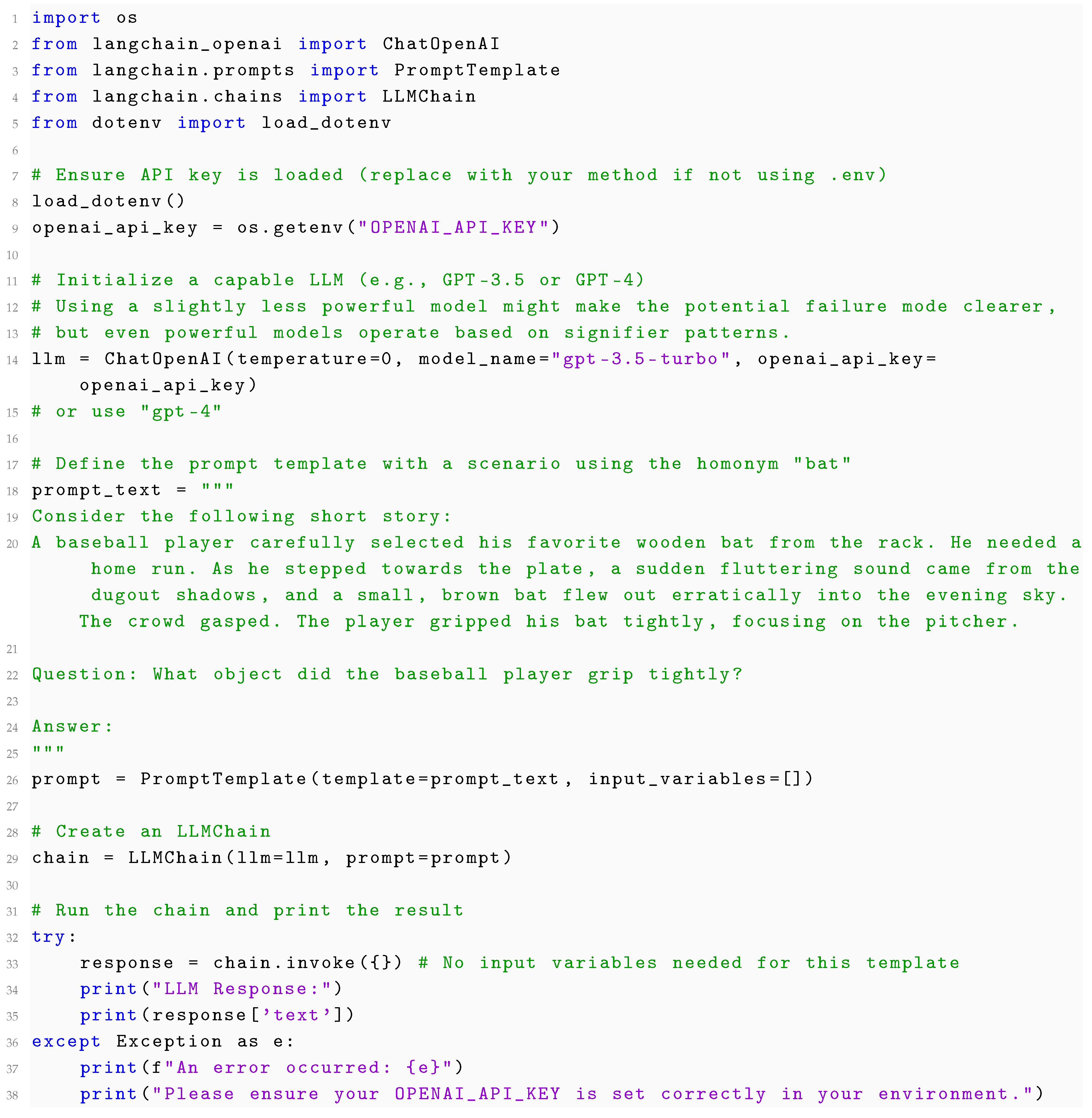

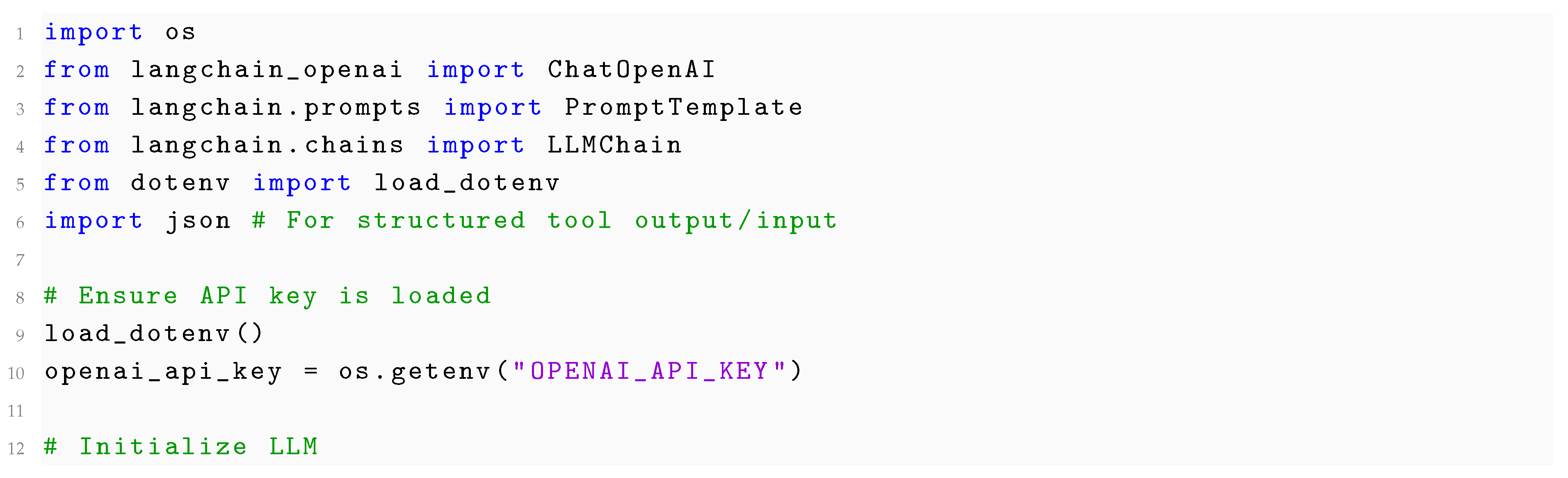

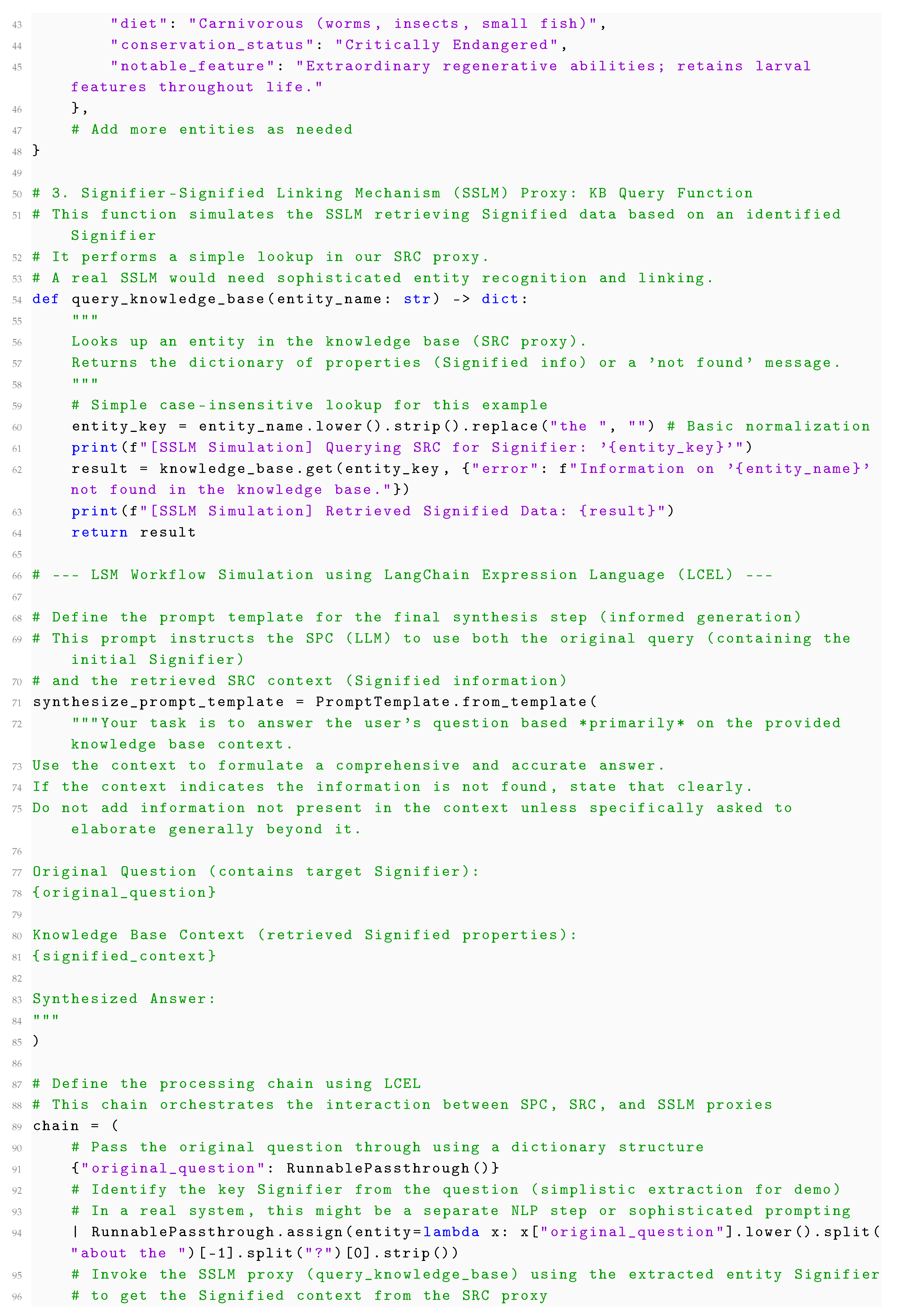

10. Practical Example: Adapting LangChain for Saussurean Semiosis (Python Sketch)

Goal and Scenario

Implementation Using LangChain

|

|

|

- 1.

-

Code Explanation:

- The ChatOpenAI instance (llm) acts as the SPC, responsible for processing the final prompt and generating the textual response.

- The knowledge_base dictionary serves as a simplified proxy for the SRC, storing structured data representing the properties associated with specific concepts (Signifieds like ’Quokka’ or ’Axolotl’).

- The query_knowledge_base function, wrapped in RunnableLambda, acts as the core of the SSLM simulation. It takes an identified entity name (a potential Signifier extracted from the user query) and retrieves the corresponding structured information (Signified properties) from the SRC proxy.

- The LangChain Expression Language (LCEL) sequence orchestrates the workflow. It first extracts a simplified entity/Signifier ("quokka") from the input question. Then, it calls the SSLM proxy (query_knowledge_base) to fetch the relevant Signified data from the SRC proxy. Finally, it formats the synthesize_prompt_template with both the original question and the retrieved Signified context, feeding this combined information to the SPC (llm) for the final answer generation. The StrOutputParser ensures a clean text output.

- 2.

-

Semiotic Interpretation:

- Signifier Input: The user query ("Tell me about the Quokka?") provides the initial Signifier ("Quokka").

-

SSLM Action: The chain structure, specifically the RunnableLambda calling query_knowledge_base after entity extraction, simulates the SSLM linking the identified Signifier ("quokka") to its corresponding entry in the SRC proxy.

- SRC Activation: The retrieval of the dictionary {"type": "Small macropod...", ...} represents the activation or fetching of the structured information associated with the Signified concept ’Quokka’ within our SRC proxy. This retrieved data embodies the conceptual properties Saussure associated with the signified, albeit in a simple, structured format here.

- Informed SPC Generation: The final LLM call is crucial. Unlike a standard LLM which would answer based solely on its internal, distributional knowledge of the Signifier "Quokka" (learned from its vast training data, potentially containing inaccuracies or missing details), this setup forces the SPC (llm) to use the explicitly provided Signified context from the SRC proxy. The prompt directs it to base the answer primarily on this context. The LLM’s task shifts from pure pattern completion based on signifier statistics to synthesizing a response grounded in the provided conceptual (Signified) information. This demonstrates the core principle of the Saussurean-inspired LSM: leveraging an explicit conceptual layer to inform and constrain language generation.

- Handling Absence: When queried about "Blobfish" (assuming it’s not in knowledge_base), the SSLM proxy returns an error message. The final prompt includes this error message as the context. The SPC, guided by the prompt, correctly reports that the information was not found in the knowledge base, demonstrating graceful handling when a Signifier cannot be linked to a known Signified within the SRC. A standard LLM might hallucinate information about a Blobfish based on its general training data.

- Contrast with Standard LLM: A direct query to a standard LLM about "Quokka" might yield a similar-sounding answer, derived from its vast internal distributional knowledge (langue). However, that knowledge lacks the explicit structure and verifiability of our SRC proxy. The LLM’s answer could be subtly inaccurate, incomplete, or even hallucinated, reflecting the statistical nature of its knowledge about the Signifier rather than access to a defined Signified concept. The LSM sketch, by incorporating the SRC lookup, introduces a layer of explicit conceptual grounding (within the limits of the SRC’s accuracy and coverage), making the answer generation process more constrained and potentially more reliable regarding the specific facts stored in the SRC.

- 3.

- Limitations of the Sketch: This example significantly simplifies the components of a true Saussurean LSM. The SRC is merely a small dictionary, not a vast, dynamic knowledge graph or learned concept space. The SSLM is rudimentary, relying on simple string matching for entity linking, whereas a real system would need sophisticated Named Entity Recognition (NER) and Entity Disambiguation. The integration via prompting is a common technique but differs from deeper architectural fusion involving cross-attention or shared embedding spaces as envisioned in Section 8.

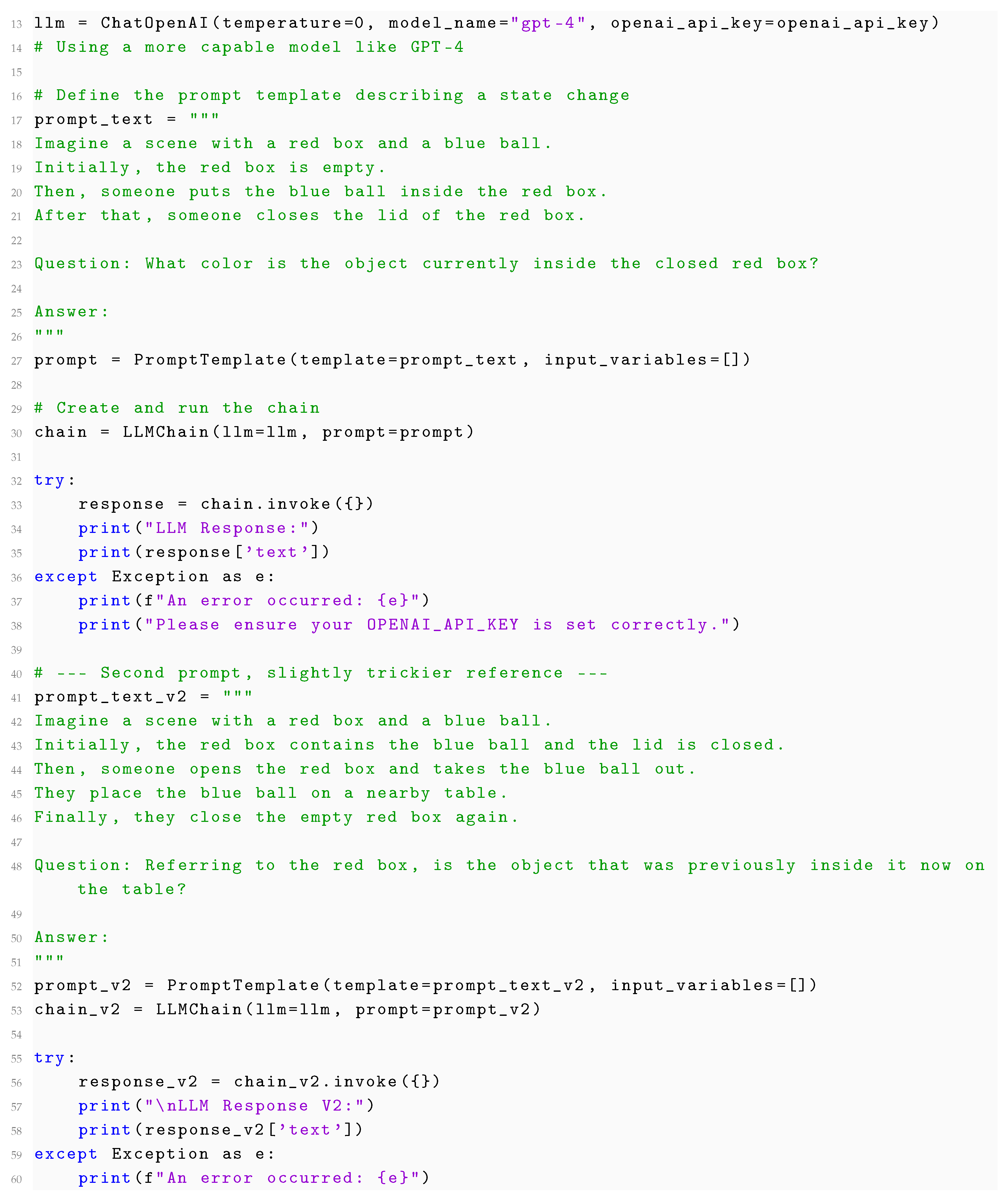

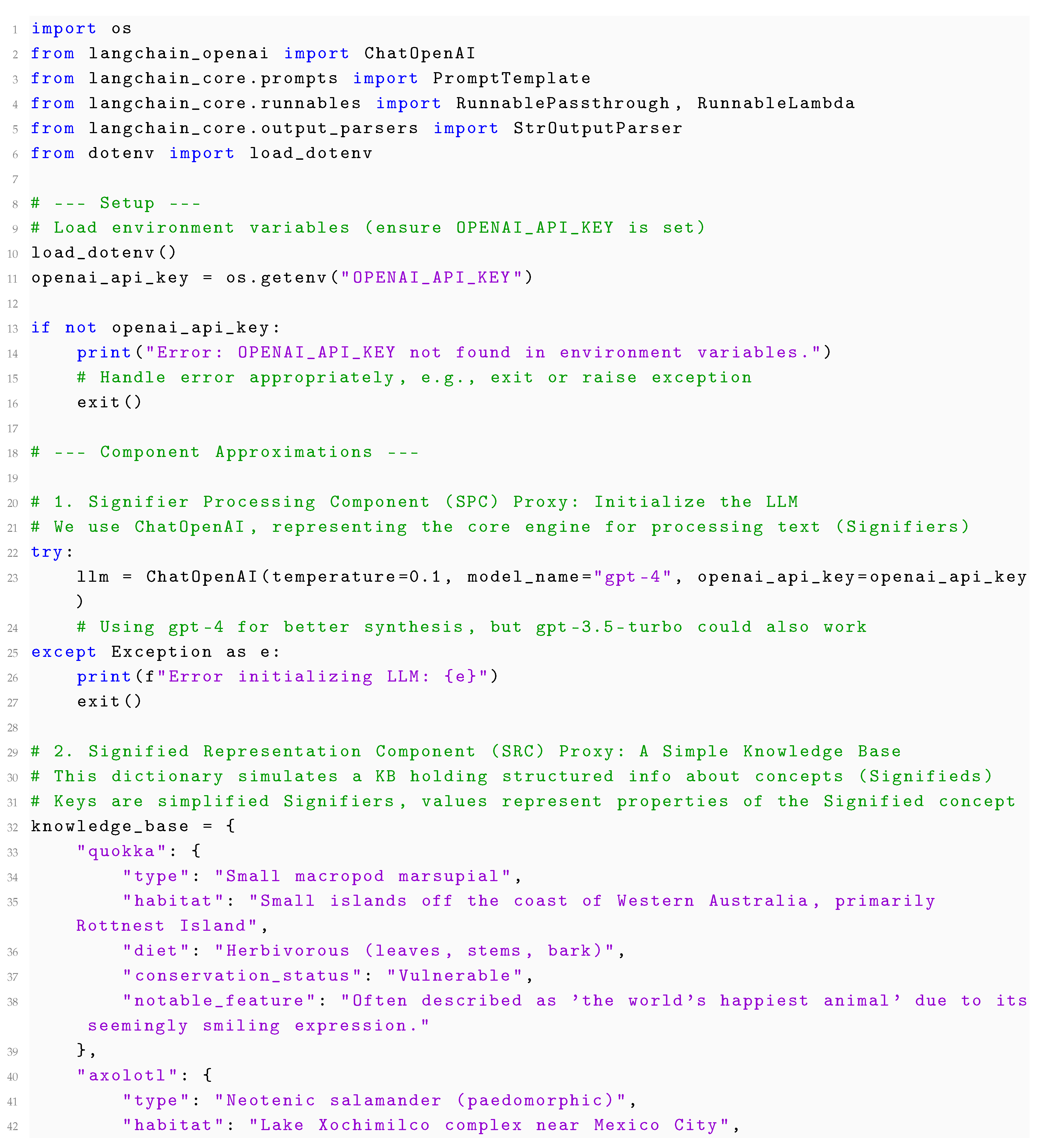

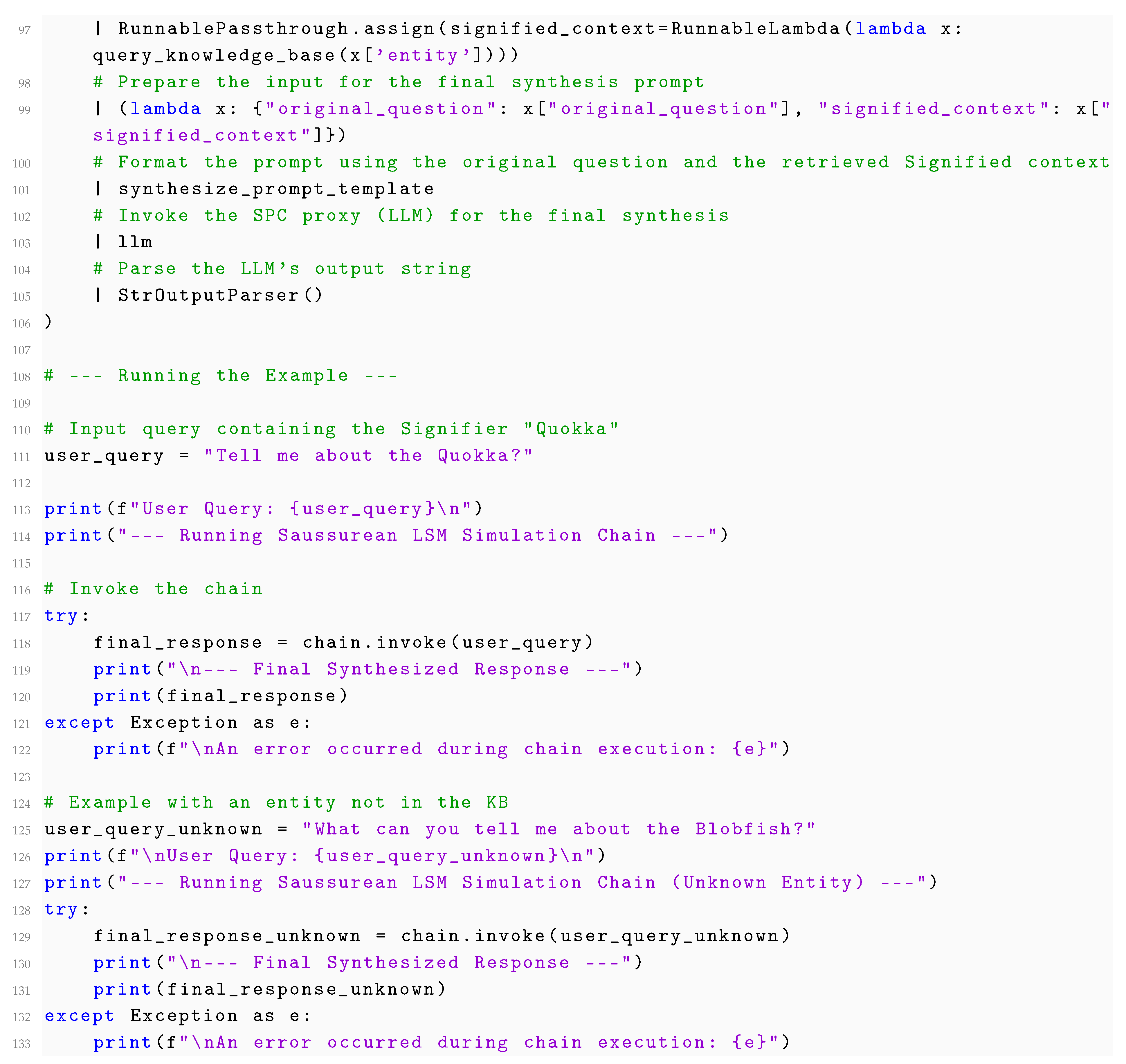

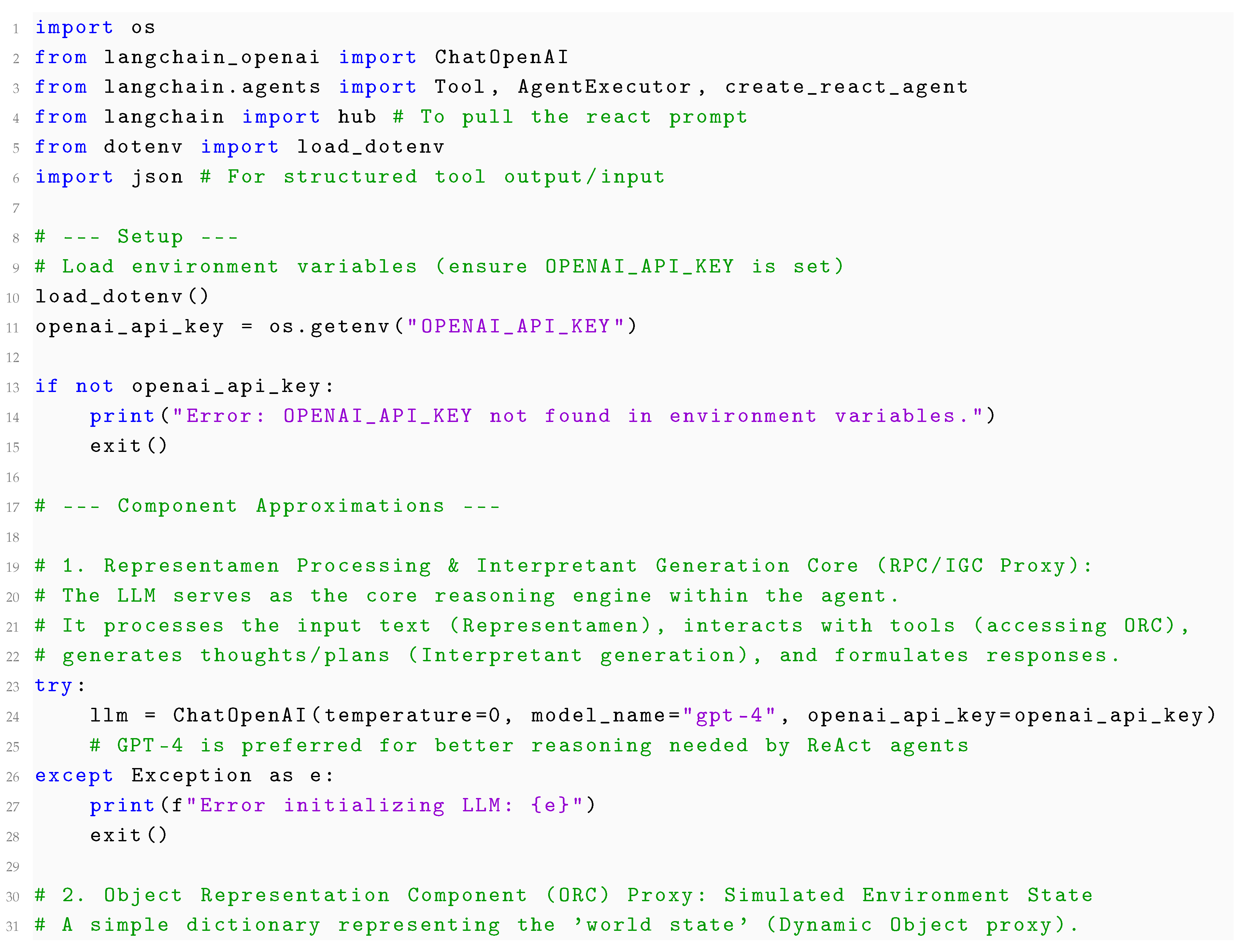

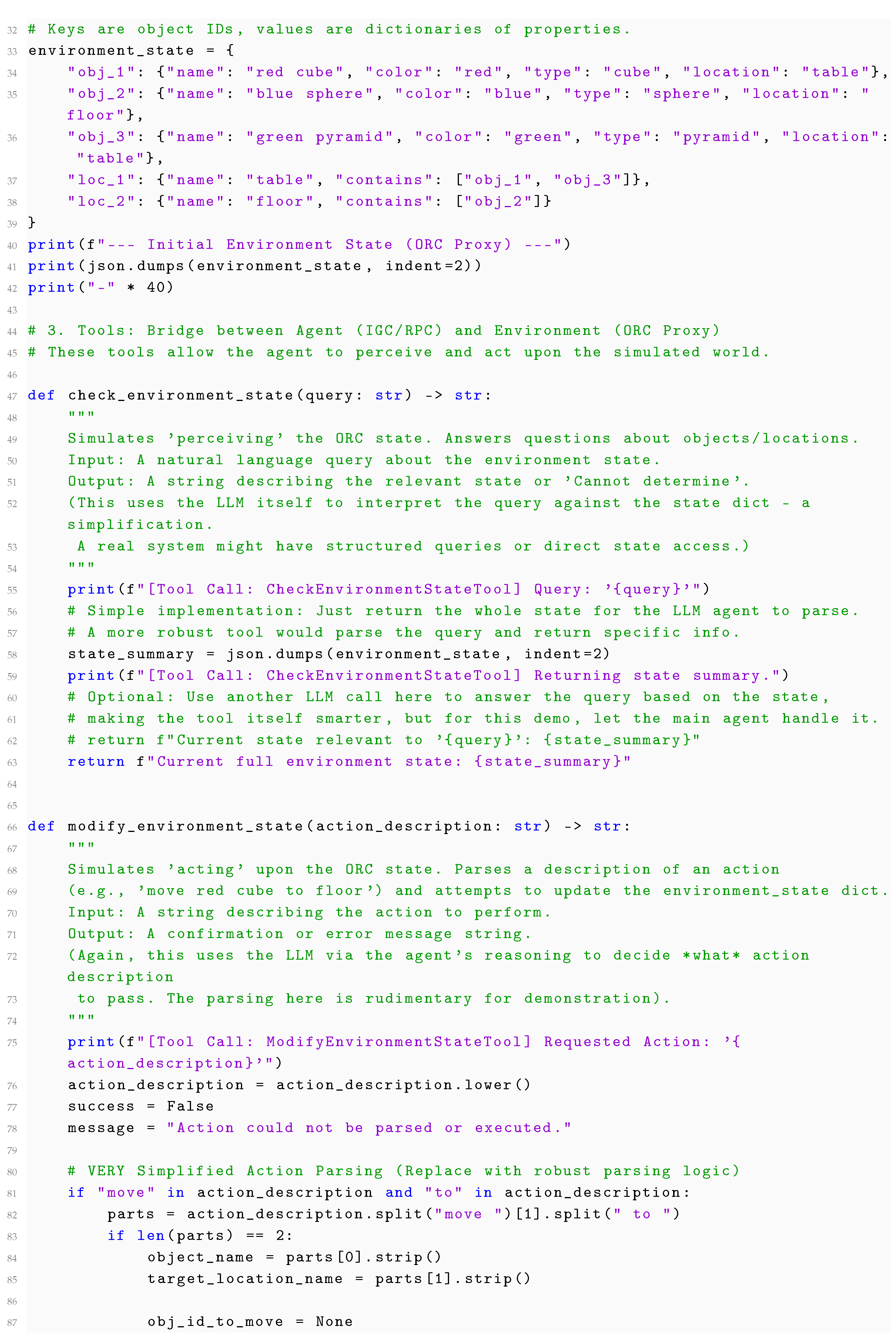

11. Practical Example: Adapting LangChain for Peircean Semiosis (Python Sketch)

Goal and Scenario

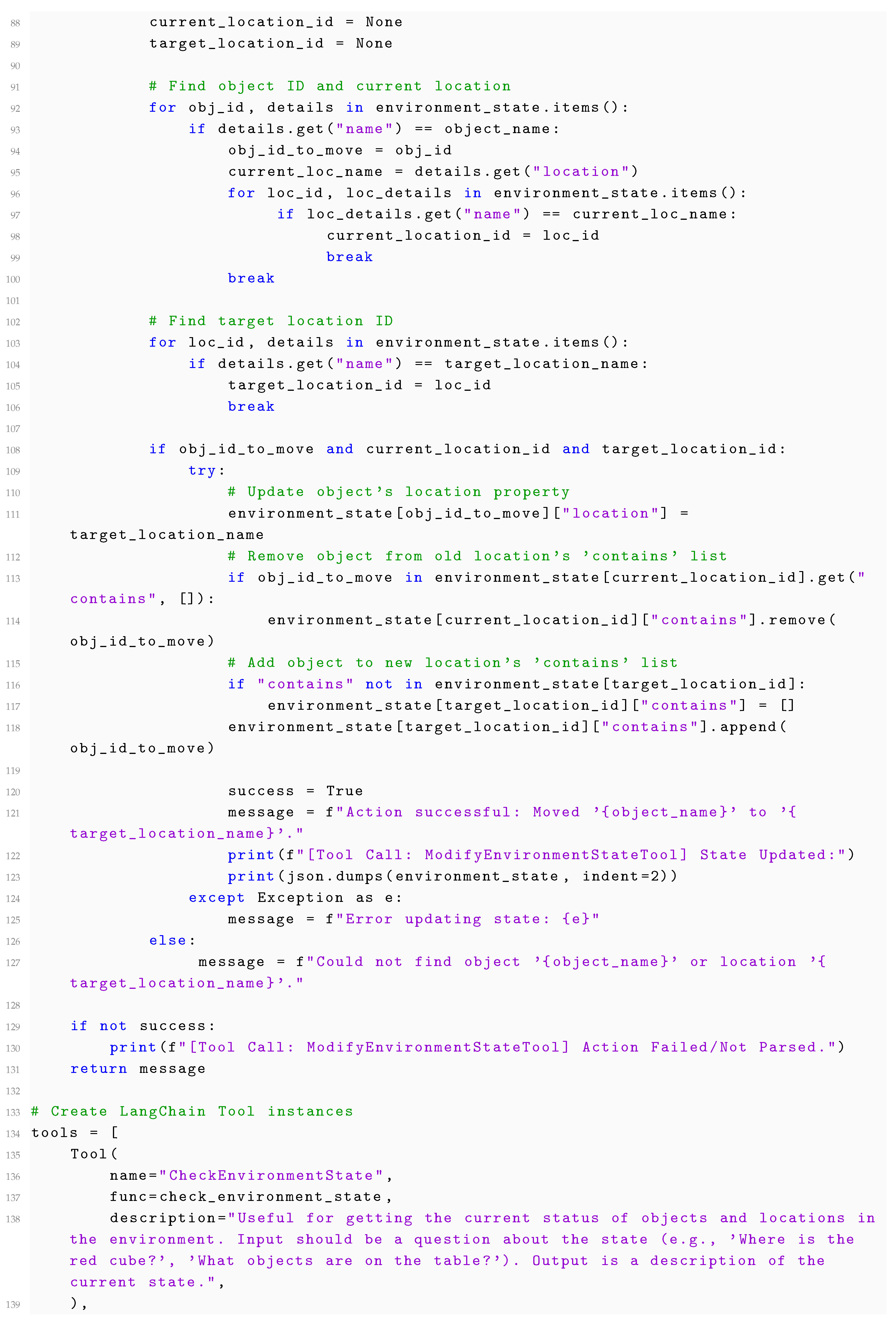

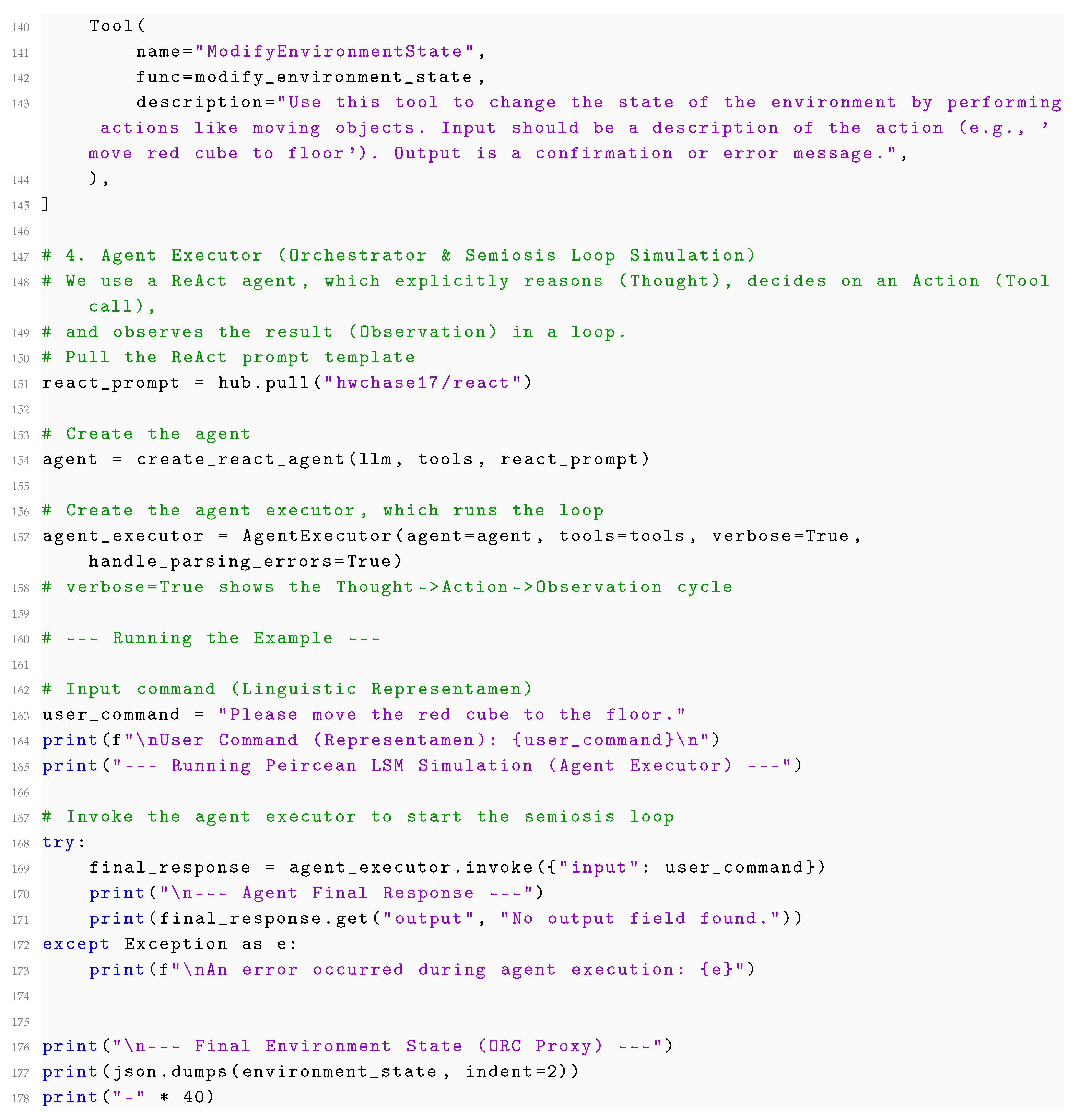

Implementation Using LangChain Agents and Custom Tools

|

|

|

|

- 1.

-

Code Explanation:

- The ChatOpenAI instance (llm) acts as the reasoning core within the LangChain Agent. It processes the user command (Representamen), generates internal reasoning steps ("Thoughts," approximating Interpretant generation), decides which Tool (Action) to use, and formats the final response. It serves roles in both the RPC and IGC.

- The environment_state dictionary acts as the ORC proxy, storing the current state of the simulated world (the Dynamic Object proxy).

- The CheckEnvironmentStateTool allows the agent to "perceive" the state of the ORC. When called, it returns the current state description. This simulates the agent accessing information about the Dynamic Object.

- The ModifyEnvironmentStateTool allows the agent to "act" upon the ORC proxy. It takes an action description formulated by the agent’s reasoning process, parses it (simplistically here), and updates the environment_state dictionary. This simulates the agent’s action affecting the Dynamic Object.

-

The AgentExecutor with a ReAct agent orchestrates the Semiosis Loop. verbose=True allows us to observe the cycle:

- –

- Thought: The LLM reasons about the input command and the current goal.

- –

-

Action: The LLM decides to use a tool (CheckEnvironmentState orModifyEnvironmentState) and specifies the input for that tool.

- –

- Observation: The agent receives the output from the executed tool (either the state description or the action confirmation/error).

- –

- This Observation feeds back into the next Thought step, allowing the agent to reassess, plan further actions, or formulate the final answer.

- 2.

-

Semiotic Interpretation:

- Representamen Input: The user command ("Please move the red cube to the floor.") serves as the initial linguistic Representamen.

-

Object Consultation (ORC Access): The agent will likely first use the CheckEnvironmentStateTool (Action) to understand the current layout (Observation). This step represents accessing the Object representation (ORC proxy) to ground the interpretation of the command. The LLM processes this state information.

- Interpretant Generation (IGC Simulation): Based on the input Representamen and the retrieved Object state, the LLM generates internal reasoning ("Thoughts"). This involves identifying the target object ("red cube"), its current location ("table"), the target location ("floor"), and formulating a plan to use the modification tool. This thought process simulates the generation of a situated, grounded Interpretant – an understanding of the required action in context.

-

Action on Object (Affecting Dynamic Object): The agent decides to use the ModifyEnvironmentStateTool (Action) with an input like "move red cube to floor". The tool’s execution successfully updates the environment_state dictionary (the ORC proxy). This step directly models the agent’s action impacting the Dynamic Object (proxy).

- Feedback and Loop Continuation: The agent receives the confirmation message from the tool (Observation: "Action successful..."). This feedback confirms the state change. The agent might perform a final check or, concluding the task is done, formulate the final response. This feedback loop is crucial for dynamic interaction and error handling (though error handling is minimal in this sketch).

- Final Output (Representamen): The agent generates a final textual response (e.g., "Okay, I have moved the red cube to the floor."), which is another Representamen communicating the outcome.

- Grounding Demonstrated: Unlike the Saussurean example which focused on linking Signifiers to abstract concepts (Signifieds), this Peircean example demonstrates grounding by linking linguistic Representamens ("red cube", "floor") to specific entities and locations within an explicit world state representation (ORC proxy). The agent’s interpretation and action are directly dependent on and affect this grounded state. It reasons about the state of the ORC proxy, not just about correlations between words.

- 3.

-

Limitations of the Sketch: This example offers a glimpse into Peircean principles but is highly simplified.

- ORC Simplicity: The environment_state dictionary is extremely basic. A real ORC would need to handle complex geometries, physics, uncertainty, continuous states, and potentially learn object properties dynamically.

- Lack of True Perception/Action: The "perception" (CheckEnvironmentStateTool) and "action" (ModifyEnvironmentStateTool) are simulated through function calls manipulating a dictionary based on text descriptions processed by the LLM. There’s no actual vision, robotics, or physics simulation. The grounding is symbolic-to-symbolic (text command -> dictionary state -> text output).

- Rudimentary IGC: The agent’s reasoning (Interpretant generation) relies entirely on the LLM’s capabilities within the ReAct framework. It lacks dedicated modules for robust planning, causal reasoning, or specialized spatial understanding as envisioned for a full Peircean LSM. Tool input/output parsing is also simplistic.

- Limited Semiosis: The loop is demonstrated, but the complexity of real-world, continuous semiosis involving multiple asynchronous inputs, uncertainty, and deep learning from interaction is not captured.

12. Conclusion and Future Directions

- Architectural Complexity and Integration: Designing and implementing architectures that seamlessly integrate heterogeneous components—neural sequence processors, perceptual modules, symbolic knowledge bases or reasoners, dynamic world models, reinforcement learning agents—is extraordinarily complex. Ensuring efficient communication, coherent information flow, and end-to-end differentiability (where needed for training) across these diverse computational paradigms remains a formidable challenge requiring novel architectural blueprints.

- Robust Grounding Mechanisms: While various grounding strategies were proposed (perceptual, interactional, knowledge-based), achieving robust, scalable, and truly effective grounding remains an open research problem. How can symbols be reliably linked to noisy, high-dimensional perceptual data? How can abstract concepts be grounded effectively? How can knowledge-based grounding avoid the brittleness and incompleteness of current KBs? Solving the symbol grounding problem [7] in practice is central to the LSM endeavor.

- Scalable World Modeling: The Peircean pathway, in particular, relies heavily on the ability to build and maintain accurate, dynamic internal world models (the ORC). Developing representations that can capture the richness of real-world environments, including object persistence, physical dynamics, causality, uncertainty, and affordances, at scale and efficiently update them based on partial or noisy observations, is one of the most profound challenges in AI [38,57].

- Rich and Flexible Meaning Representation: Moving beyond distributional embeddings to represent conceptual knowledge (Signifieds) and generate grounded Interpretants requires significant advances in knowledge representation. Finding formalisms that combine the flexibility and learning capability of neural networks with the structure, compositionality, and reasoning power of symbolic systems (neuro-symbolic AI; [52]) is a critical research avenue. How can concepts be represented to support both classification and deep reasoning?

- Effective Learning Paradigms: Training LSMs, especially Peircean-inspired ones involving interaction loops, demands learning paradigms beyond supervised learning on static datasets. While RL [56], self-supervised learning on interaction data, and imitation learning are promising directions, significant challenges remain in sample efficiency, exploration strategies, reward design (especially for complex cognitive tasks), and ensuring safe learning in real-world or high-fidelity simulated environments. How can LSMs learn effectively from limited interaction or generalize robustly from simulation to reality (the sim-to-real gap)?

- Computational Resources: LSMs, integrating multiple complex components and potentially requiring extensive interaction-based training, are likely to be even more computationally demanding than current large-scale LLMs, posing significant resource challenges for development and deployment. Research into efficient architectures and training methods will be crucial.

- Evaluation Metrics: Current NLP benchmarks primarily evaluate performance on text-based tasks, often focusing on linguistic fluency or specific skills in isolation. Evaluating the core capabilities envisioned for LSMs—such as the degree of grounding, the robustness of reasoning across contexts, situational awareness, the coherence of the internal world model, or the meaningfulness of interaction—requires the development of entirely new evaluation methodologies, benchmarks, and theoretical frameworks [9].

- Development of Novel Architectures: Research into hybrid neuro-symbolic architectures, modular designs integrating diverse reasoning and representation systems, and architectures explicitly supporting dynamic world modeling and grounding loops.

- Learnable World Models: Advancing research in unsupervised or self-supervised learning of causal models, intuitive physics, object permanence, and spatial relations directly from sensory and interaction data.

- Multimodal Grounding Research: Improving techniques for fusing information across modalities and developing robust methods for linking linguistic symbols to perceptual data and embodied experiences beyond simple correlation.

- Advanced Learning Algorithms: Designing RL and interactive learning algorithms that are more sample-efficient, handle sparse rewards, support hierarchical task decomposition, enable safe exploration, and facilitate transfer learning between simulation and reality.

- Data Curation and Simulation Environments: Creating rich, large-scale datasets that explicitly link language to perception, action, and structured knowledge; developing high-fidelity, interactive simulation environments suitable for training and evaluating embodied or situated LSMs.

- New Evaluation Benchmarks: Designing challenging benchmarks that specifically probe for grounded understanding, robust reasoning across diverse contexts, situational awareness, compositional generalization, and meaningful interaction, moving beyond purely text-based metrics.

- Theoretical Foundations: Further developing the theoretical understanding of grounding, meaning representation, and semiosis within computational systems, potentially drawing deeper insights from cognitive science, linguistics, and philosophy of mind alongside semiotics.

- Ethical Considerations: Proactively investigating the ethical implications of potentially more capable, grounded, and autonomous AI systems enabled by the LSM paradigm, focusing on issues of safety, alignment, bias amplification through grounded representations, and societal impact.

References

- OpenAI. GPT-4 Technical Report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.08774 2023, [2303.08774].

- Gemini Team.; Google. Gemini: A Family of Highly Capable Multimodal Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.11805 2023, [2312.11805].

- Anthropic. Introducing the next generation of Claude. Anthropic News, 2024. Accessed May 15, 2024.

- Meta AI. Introducing Meta Llama 3: The most capable openly available LLM to date. Meta AI Blog, 2024. Accessed May 15, 2024.

- Mitchell, M.; Krakauer, D.C. The fallacy of AI functionality. Science 2023, 379, 1190–1191. [CrossRef]

- Stokke, A. Why Large Language Models Are Poor Reasoners. Inquiry 2024, pp. 1–21. Advance online publication. [CrossRef]

- Harnad, S. The Symbol Grounding Problem. Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena 1990, 42, 335–346. [CrossRef]

- Bisk, Y.; Holtzman, A.; Thomason, J.; Andreas, J.; Bengio, Y.; Chai, J.; et al. Experience Grounds Language. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.11776 2023, [2309.11776].

- Frank, M.C. Symbolic behavior in networks and the emergence of grounding. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 2024, 47, e32. [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z.; Lee, N.; Frieske, R.; Yu, T.; Su, D.; Xu, Y.; et al. Survey of Hallucination in Natural Language Generation. ACM Computing Surveys 2023, 55, 1–38. [CrossRef]

- Rawte, V.; Sheth, A.; Das, A. A Survey of Hallucination in Large Foundation Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.05922 2023, [2309.05922].

- Varshney, L.R.; Alemzadeh, H.; Chen, F. Hallucination Detection: Robust and Efficient Detection of Large Language Model Hallucinations using Entropy and Variance-Based Metrics. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.14406 2024, [2402.14406].

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Cui, L.; Cai, D.; Liu, L.; Wang, W.Y. Mitigating Hallucinations of Large Language Models via Knowledge Consistent Alignment. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.01307 2024, [2401.01307].

- Valmeekam, K.; Marquez, M.A.R.; Mustafa, M.; Sreedharan, S.; Kambhampati, S. Can LLMs Plan? On the Logical Reasoning Capabilities of Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.15771 2023, [2305.15771].

- Liu, Z.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Wu, C.H.; Fung, P. Evaluating the Logical Reasoning Ability of Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.06940 2024, [2402.06940].

- Ullman, S. Large language models and the alignment problem. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2023, 378, 20220143. [CrossRef]

- Gendron, N.; Larochelle, H.; Bengio, Y. Towards Biologically Plausible Models of Reasoning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.06409 2024, [2401.06409].

- Bender, E.M.; Gebru, T.; McMillan-Major, A.; Shmitchell, S. On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big? In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, New York, NY, USA, 2021; FAccT ’21, pp. 610–623. https://doi.org/10.1145/3442188.3445922.

- Pavlick, E. The Illusion of Understanding in Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.14747 2023, [2311.14747].

- de Saussure, F. Course in General Linguistics; Philosophical Library, 1959. Original work published 1916.

- Peirce, C.S. Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce; Vol. 1–8, Harvard University Press, 1931–1958.

- Chase, H. LangChain Python Library. GitHub Repository, 2023.

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; et al. Attention is All You Need. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30 (NIPS 2017); Guyon, I.; Luxburg, U.V.; Bengio, S.; Wallach, H.; Fergus, R.; Vishwanathan, S.V.N.; Garnett, R., Eds. Curran Associates, Inc., 2017, pp. 5998–6008.

- Gu, A.; Dao, T. Mamba: Linear-Time Sequence Modeling with Selective State Spaces. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.00752 2023, [2312.00752].

- Kim, Y.; Lee, H.; Kim, G. Probing Attention Patterns in State-of-the-Art Transformers. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2024, Vol. 38.

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers), Minneapolis, Minnesota, 2019; pp. 4171–4186. [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.B.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.; Dhariwal, P.; et al. Language Models are Few-Shot Learners. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33 (NeurIPS 2020); Larochelle, H.; Ranzato, M.; Hadsell, R.; Balcan, M.F.; Lin, H.T., Eds. Curran Associates, Inc., 2020, pp. 1877–1901.

- Ouyang, L.; Wu, J.; Jiang, X.; Almeida, D.; Wainwright, C.L.; Mishkin, P.; et al. Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 35 (NeurIPS 2022); Koyejo, S.; Mohamed, S.; Agarwal, A.; Belgrave, D.; Cho, K.; Oh, A., Eds. Curran Associates, Inc., 2022, pp. 27730–27744.

- Rafailov, R.; Sharma, A.; Mitchell, E.; Ermon, S.; Manning, C.D.; Finn, C. Direct Preference Optimization: Your Language Model is Secretly a Reward Model. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 36 (NeurIPS 2023); Globerson, A.; Saenko, K.; Zhang, C.; Mandt, S., Eds., 2023.

- Kaplan, J.; McCandlish, S.; Henighan, T.; Brown, T.B.; Chess, B.; Child, R.; et al. Scaling Laws for Neural Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2001.08361 2020, [2001.08361].

- Hoffmann, J.; Borgeaud, S.; Mensch, A.; Buchatskaya, E.; Cai, T.; Rutherford, E.; et al. Training Compute-Optimal Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.15556 2022, [2203.15556].

- Li, X.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, C.; Liu, Y.; Jin, Q. The Era of Big Small Language Models: A Survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.17919 2024, [2401.17919].

- Chan, S.C.Y.; Santoro, A.; Lampinen, A.K.; Wang, J.X.; Singh, S.; Hill, F. Data Distributional Properties Drive Emergent Few-Shot Learning in Transformers. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 35 (NeurIPS 2022); Koyejo, S.; Mohamed, S.; Agarwal, A.; Belgrave, D.; Cho, K.; Oh, A., Eds. Curran Associates, Inc., 2022, pp. 28169–28181.

- Yuksekgonul, M.; Jurafsky, D.; Zou, J. Attribution and Alignment: Effects of Preference Optimization on the Referential Capabilities of Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.00903 2024, [2402.00903].

- Barsalou, L.W. Grounded cognition. Annual Review of Psychology 2008, 59, 617–645. [CrossRef]

- Lake, B.M.; Murphy, G.L. Word meaning in minds and machines. Psychological Review 2021, 128, 401–420. [CrossRef]

- Marcus, G. The Next Decade in AI: Four Steps Towards Robust Artificial Intelligence. arXiv preprint arXiv:2002.06177 2020, [2002.06177].

- Chen, Z.; Wang, W. Emergent World Models in Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.08788 2024, [2402.08788].

- Marcus, G.; Davis, E. GPT-4’s successes, and GPT-4’s failures. Marcus on AI Substack, 2023.

- Lewis, P.; Perez, E.; Piktus, A.; Petroni, F.; Karpukhin, V.; Goyal, N.; et al. Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Knowledge-Intensive NLP Tasks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33 (NeurIPS 2020); Larochelle, H.; Ranzato, M.; Hadsell, R.; Balcan, M.F.; Lin, H.T., Eds. Curran Associates, Inc., 2020, pp. 9459–9474.

- Pan, S.; Luo, L.; Wang, Y.; Chen, C.; Wang, J.; Wu, X. Unifying Large Language Models and Knowledge Graphs: A Roadmap. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.08302v3 2024, [2306.08302].

- Azaria, A. A Theoretical Framework for Hallucination Mitigation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.03407 2024, [2402.03407].

- Wei, J.; Wang, X.; Schuurmans, D.; Bosma, M.; Chi, E.; Le, Q.; Zhou, D. Chain-of-Thought Prompting Elicits Reasoning in Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 35 (NeurIPS 2022); Koyejo, S.; Mohamed, S.; Agarwal, A.; Belgrave, D.; Cho, K.; Oh, A., Eds. Curran Associates, Inc., 2022, pp. 24824–24837.

- Dziri, N.; Milton, S.; Yu, M.; Zaiane, O.; Reddy, S. Faith and Fate: Limits of Transformers on Compositionality. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 36 (NeurIPS 2023); Globerson, A.; Saenko, K.; Zhang, C.; Mandt, S., Eds., 2023.

- Kıcıman, E.; Ness, R.; Sharma, A.; Tan, C. Causal Reasoning and Large Language Models: Opening a New Frontier for Causality. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.00050 2023, [2305.00050].

- Zečević, M.; Singh M., D.D.S.; Kersting, K. Evaluating Causal Reasoning Capabilities of Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.12517 2023, [2305.12517].

- Jin, Z.; Feng, J.; Xu, R.; Zheng, W.; Liu, S.; Chen, J.; et al. Can Large Language Models Truly Understand Causal Statements? A Study on Robustness. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.10249 2024, [2402.10249].

- Mikolov, T.; Sutskever, I.; Chen, K.; Corrado, G.S.; Dean, J. Distributed representations of words and phrases and their compositionality. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 26 (NeurIPS 2013); Burges, C.J.C.; Bottou, L.; Welling, M.; Ghahramani, Z.; Weinberger, K.Q., Eds. Curran Associates, Inc., 2013, pp. 3111–3119.

- Pennington, J.; Socher, R.; Manning, C.D. GloVe: Global Vectors for Word Representation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), Doha, Qatar, 2014; pp. 1532–1543. [CrossRef]

- Manning, C.D.; Schütze, H. Foundations of Statistical Natural Language Processing; MIT Press, 1999.

- Santaella, L. Teoria Geral dos Signos: Como as linguagens significam as coisas; Pioneira, 2000.

- Garcez, A.S.d.; Lamb, L.C. Neurosymbolic AI: The 3rd Wave. arXiv preprint arXiv:2012.05876 2020, [2012.05876].

- Schmidhuber, J. Deep learning in neural networks: An overview. Neural Networks 2015, 61, 85–117. [CrossRef]

- Pan, A.; Kushman, N.; Liang, P.; Pasupat, P. Logic and Language Models. 2024, [2401.08143].

- Lin, B.Y.; Lee, W.; Liu, J.; Ren, P.; Yang, Z.; Ren, X. Generating Benchmarks for Factuality Evaluation of Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.08491 2023, [2311.08491].

- Sutton, R.S.; Barto, A.G. Reinforcement learning: An introduction, 2nd ed.; MIT Press, 2018.

- Lake, B.M.; Ullman, T.D.; Tenenbaum, J.B.; Gershman, S.J. Building machines that learn and think like people. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 2017, 40, E253. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).