3.2. Statistical Analysis of Results

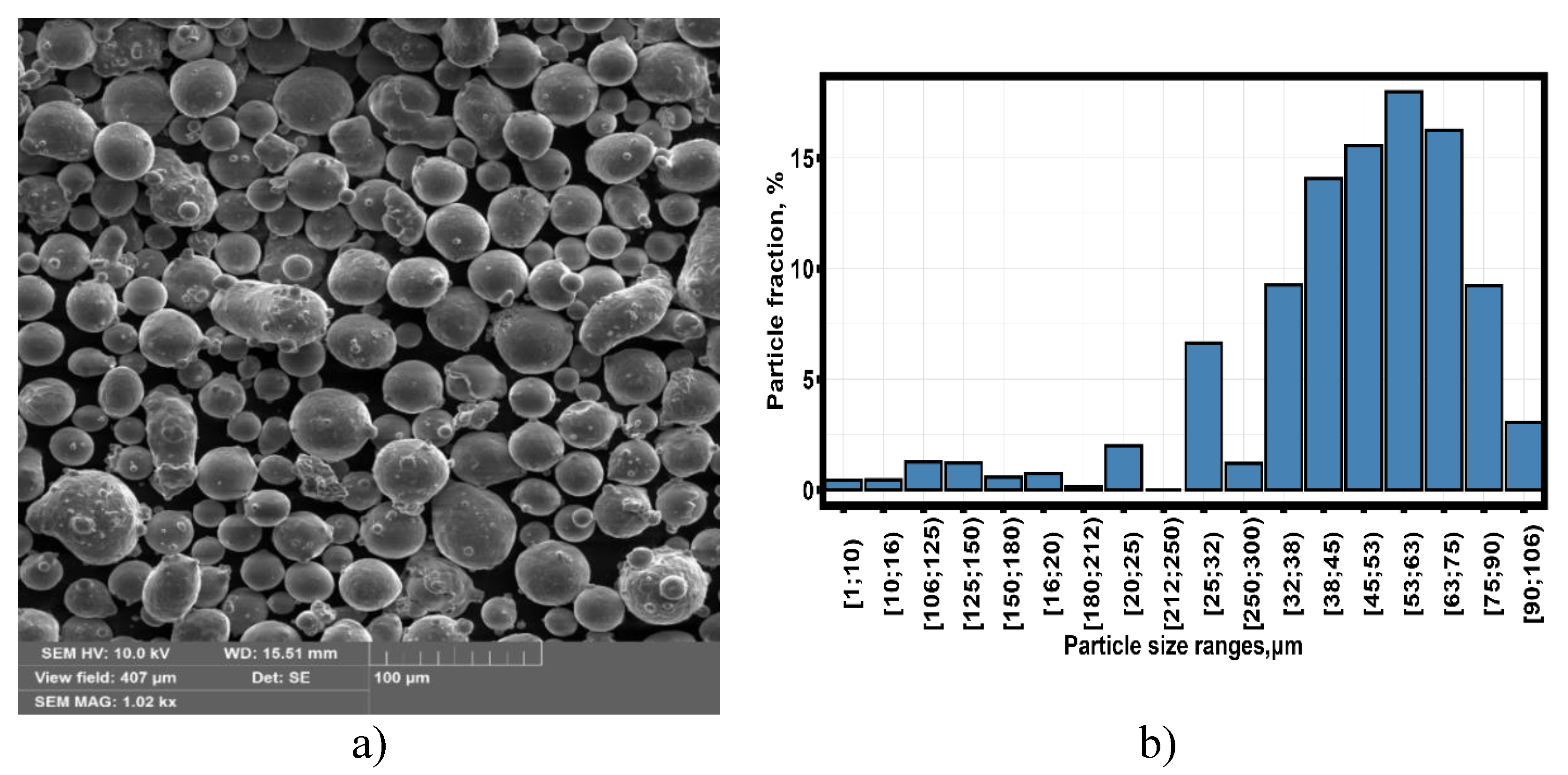

Appendix B presents calculations of basic statistical quantities of mechanical properties of thin-walled samples obtained by selective laser melting technology from Al-Mn-Mg-Ti-Zr alloy.

Figure 8 shows the dependences of basic engineering quantities characterizing surface roughness. Vickers microhardness, strength and yield strength and strain correspond to the strength and yield strength depending on heat treatment, Young’s modulus and secant modulus (0.05%-0.25% strain).

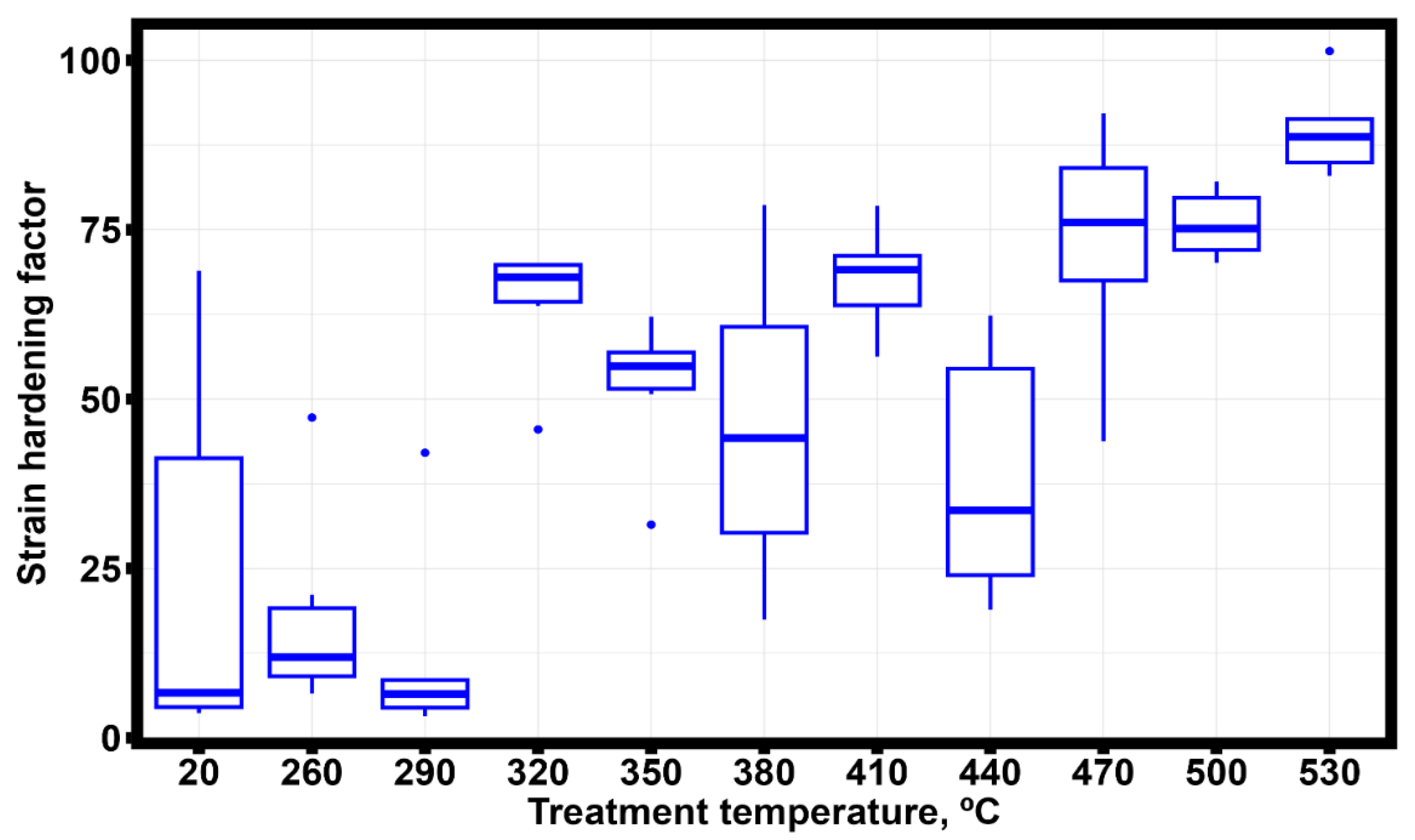

Figure 9 shows the strain hardening factor for SLMed Al-Mn-Mg-Ti-Zr thin-walled samples.

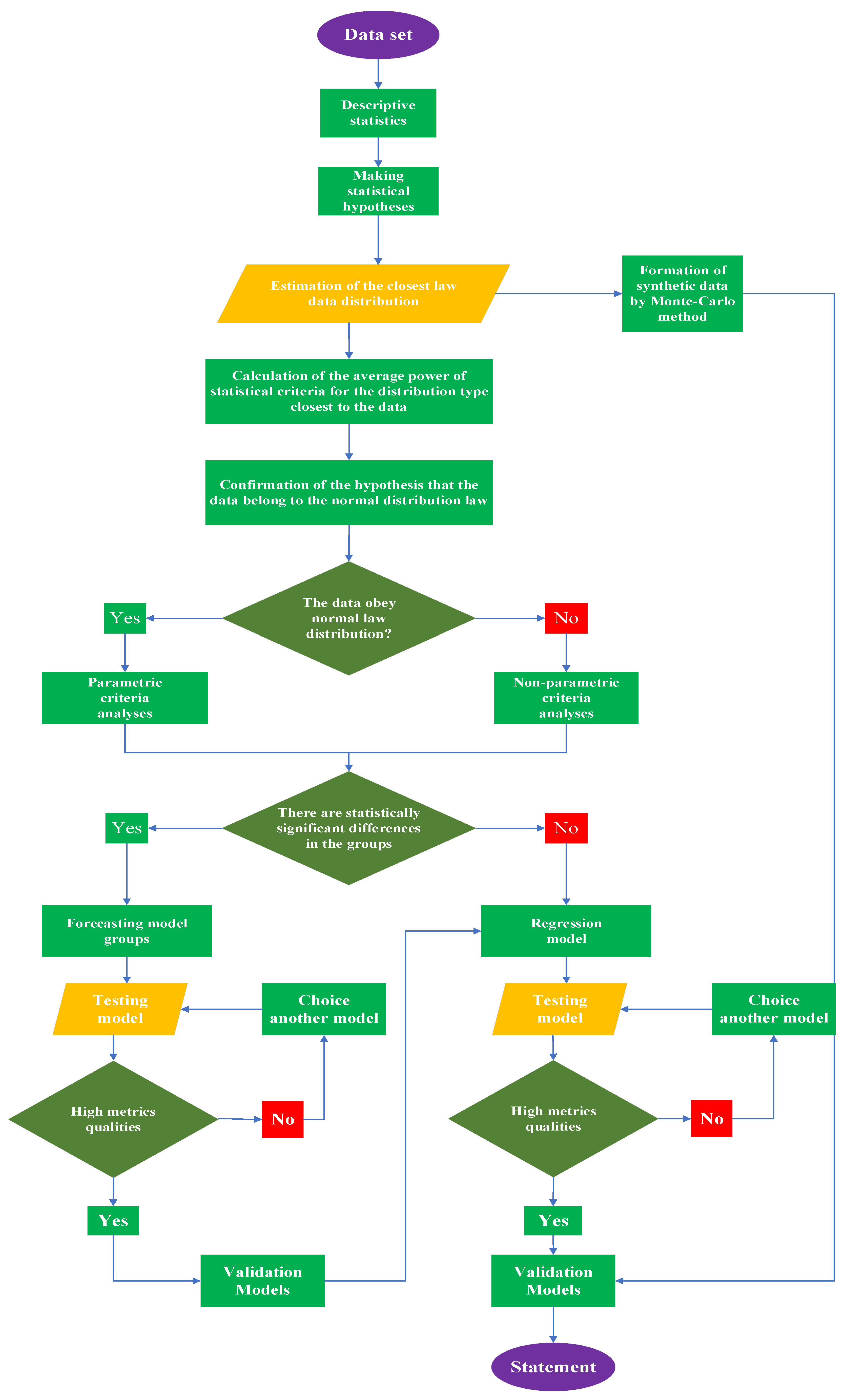

Based on the presented results of descriptive statistics, we can hypothesize the existence of three groups of samples heat-treated at different temperatures, the mechanical properties and microhardness of which are statistically significantly different from each other. The results of measuring surface roughness before and after heat treatment do not allow us to put forward such a hypothesis. According to the algorithm presented in

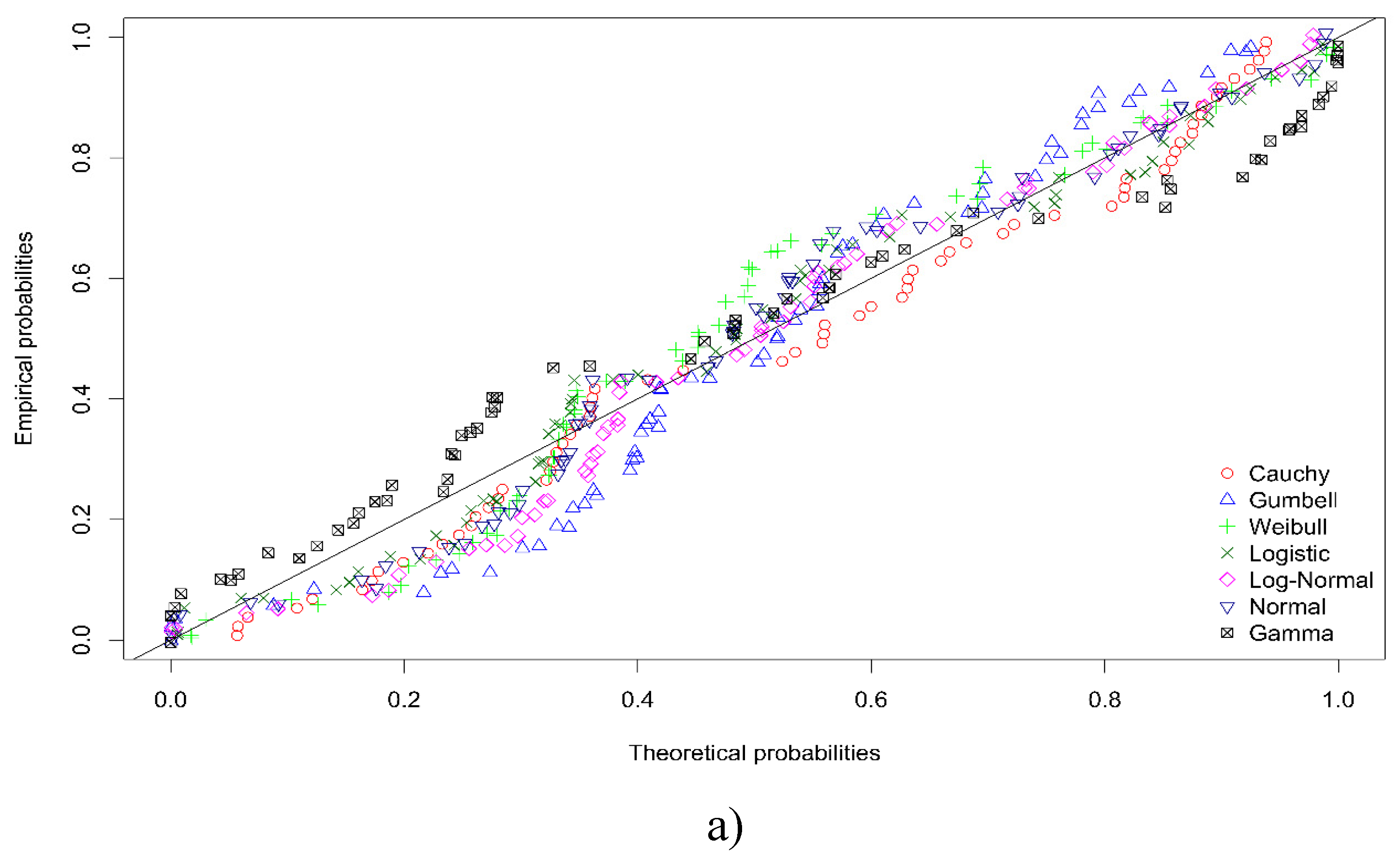

Figure 4, the closest law of distribution of mechanical properties was determined using Akaike and Bayes criteria. The results of the analysis are presented in

Table 3.

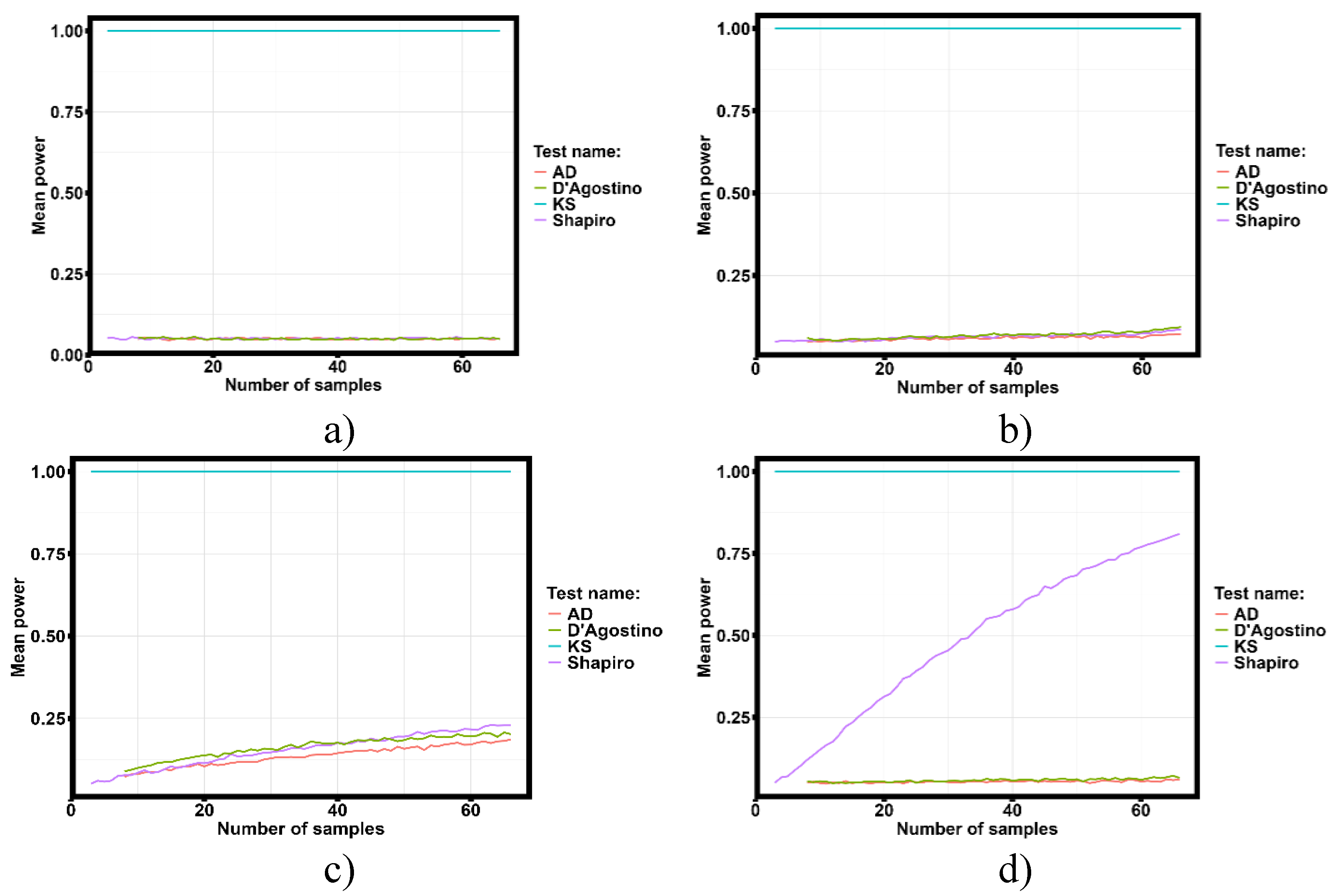

Among the eight considered laws of distribution, only seven of them were found in the data analyzed. The conformity of the data distribution to the normal distribution law was tested for the seven founded distribution laws in the experimental data. Testing was carried out by the estimation of the average statistical power of the four criteria (Shapiro-Wilk, D’Agusto, Kolmogorov-Smirnov, and Anderson-Darling).

Figure 10 shows the average statistical power of the four criteria for the yield strength distribution to the normal distribution law.

Estimation of the average statistical power on other parameters included in the dataset analyzed shows similar results. The analysis of the results presented in

Figure 10 shows that only the Kolmogorov-Smirnov criterion preserves its statistical power for any amount of data in the seven proposed distribution laws.

Table 4 presents the results obtained for the Kolmogorov-Smirnov criterion.

From the results of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test it follows that the distribution of all the studied values statistically significantly differs from the normal distribution law (p-value <0.05). Consequently, for further analysis, the Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s criterion will be applied, and the Bonferroni correction will be used as a correction for multiple comparison.

Table 5 shows the results of analyzing the differences in the groups of samples obtained by selective laser melting technique from Al-Mn-Mg-Ti-Zr alloy heat-treated at different temperatures.

For surface roughness parameters (Ra, Rz and Rmax) statistically significant differences in samples before heat treatment and after heat treatment, as well as at different temperatures of heat treatment were not revealed (p-value>0.05). Based on the analysis of differences in mechanical properties of samples obtained by selective laser melting technology and heat-treated at different temperatures, three groups can be distinguished. The Spearman correlation coefficient between the Euclidean distance of the hierarchical clustering and the cophenetic distance of the data was 0.834.

Table 6 shows the temperatures and sample numbers of each group.

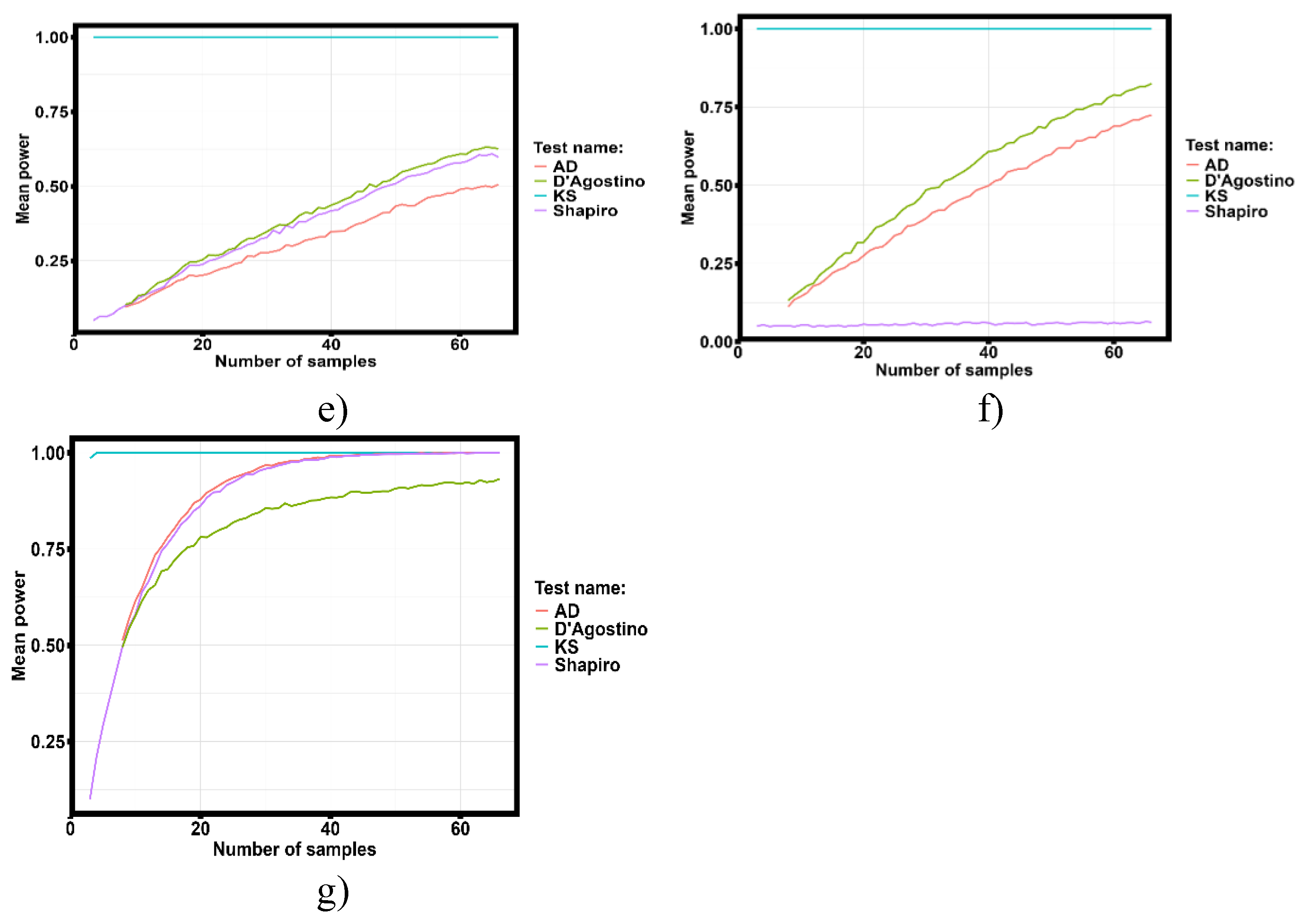

To investigate the relationships between tensile mechanical properties, microhardness and surface roughness, correlation analysis was performed in each of the selected data groups. Because the studied data have a distribution different from the normal distribution law, the Spearman correlation was used to evaluate the presence of statistical relationship in the data.

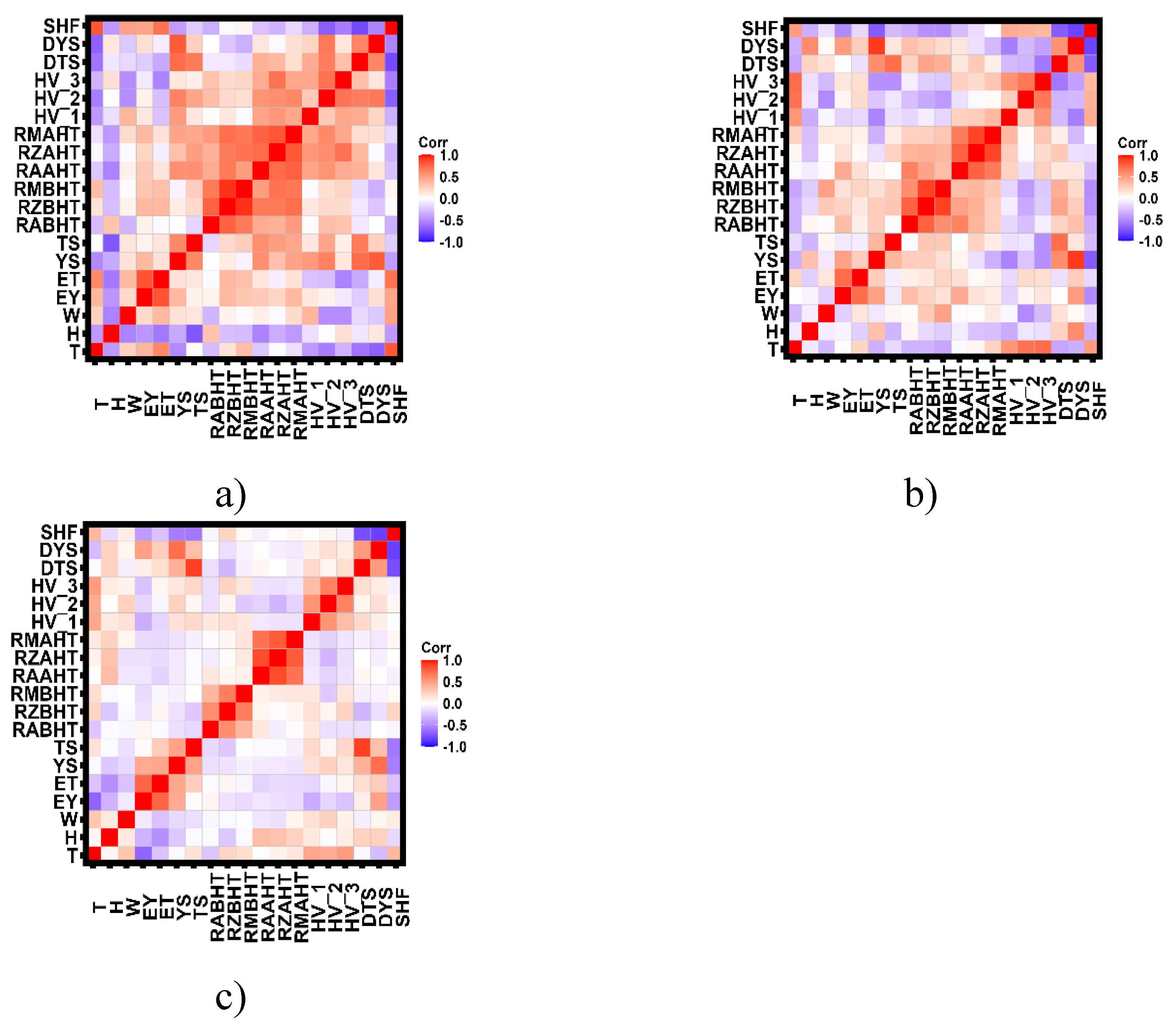

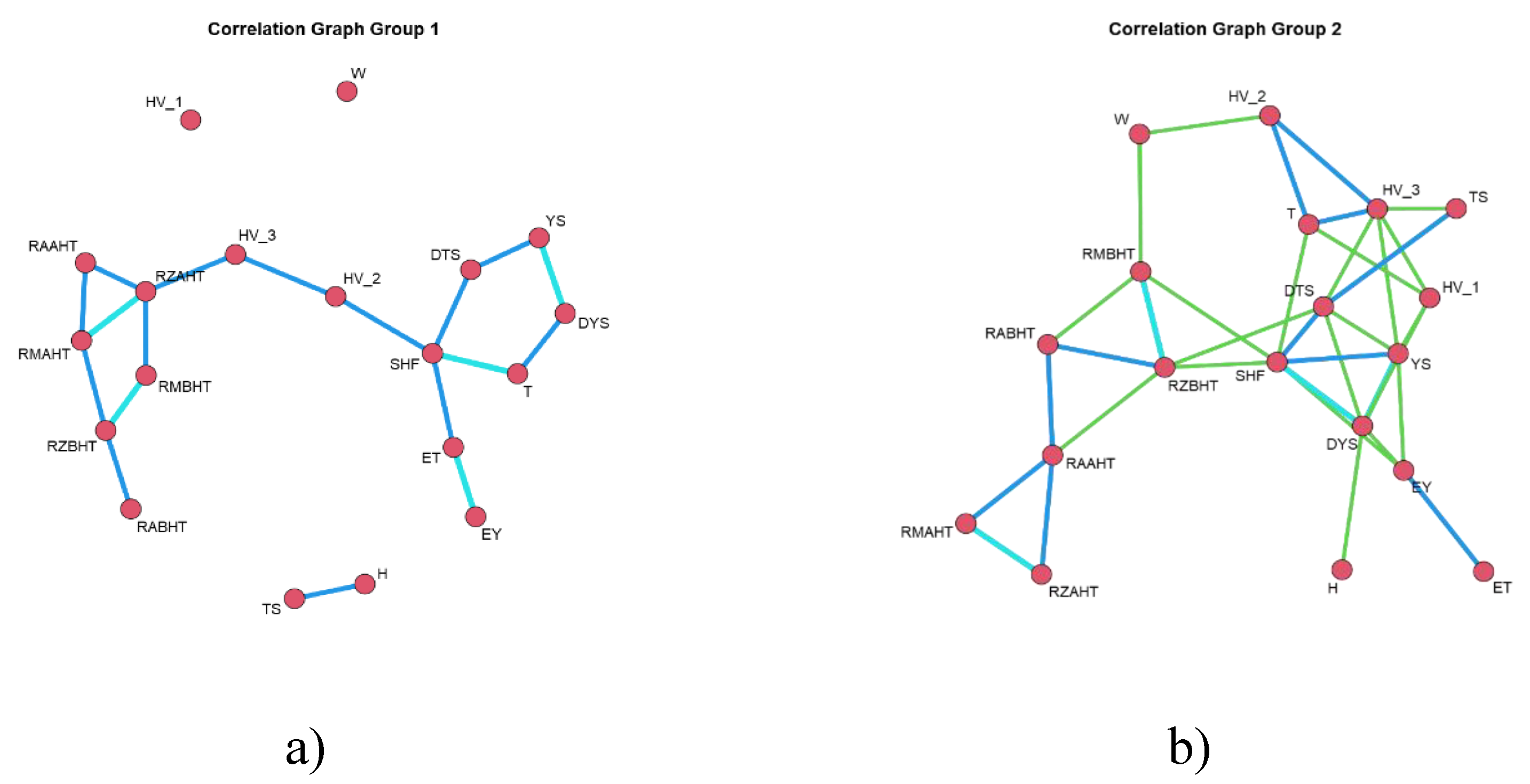

Figure 11 shows the results of correlation analysis in the three selected data groups.

Based on Spearman correlation estimates, correlation graphs were constructed to account for the presence of statistically significant relationships between variables.

Figure 12 shows the results of the construction of correlation graphs in each of the groups.

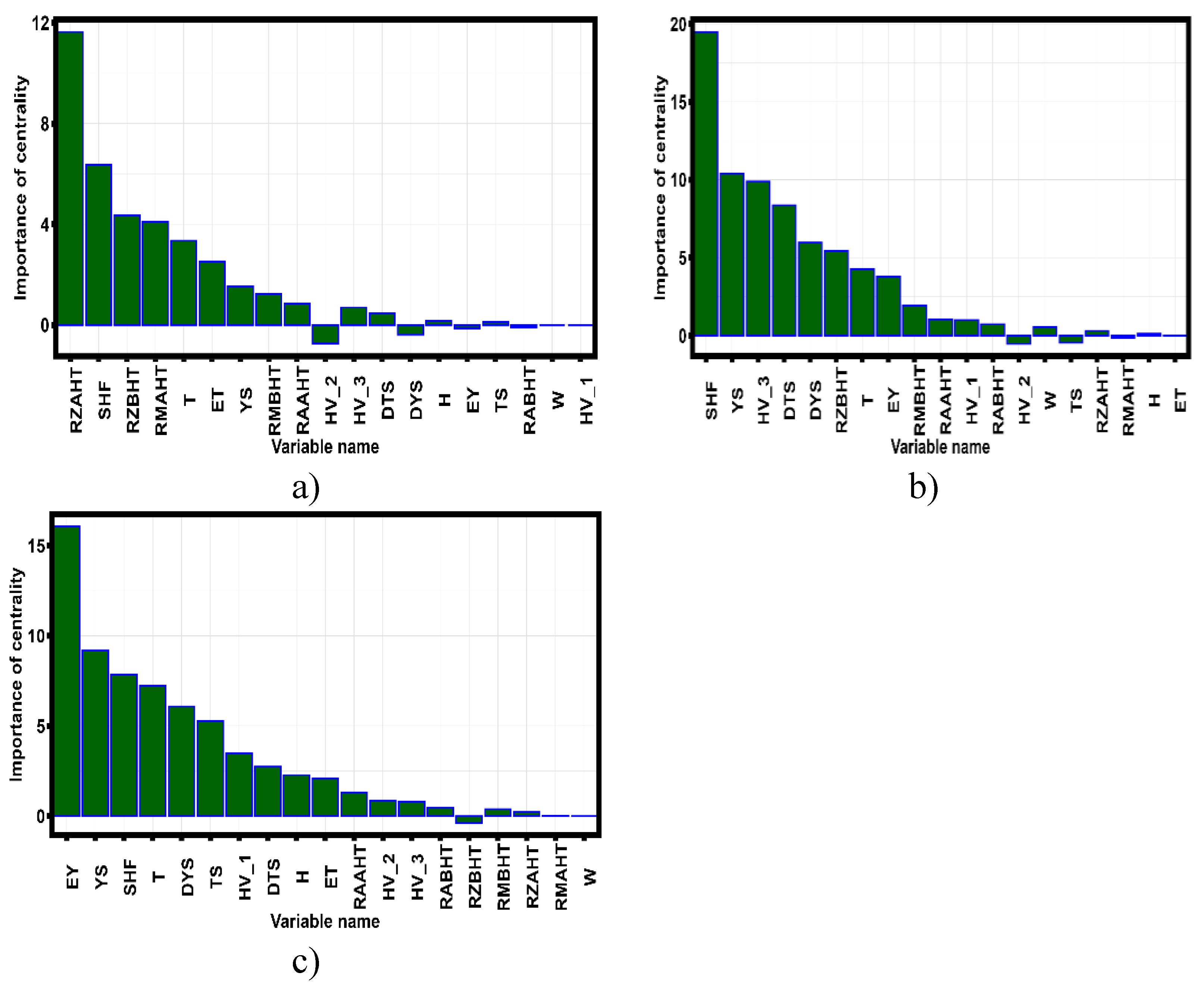

Figure 13 shows the results of ranking the variables included in the dataset based on the centrality calculations using equation (1).

Figure 13.

- Results of centrality analysis performed using equation (1). a) Group 1; b) Group 2; c) Group 3. Where T - heat treatment temperature; H - actual specimen thickness; W - actual specimen width; EY - Young’s modulus; ET - secant modulus; YS - yield strength; TS - tensile strength; RABHT - Ra before heat treatment; RZBHT - Rz before heat treatment; RMBHT - Rmax before heat treatment; RAAHT - Ra after heat treatment; RZAHT - Rz after heat treatment; RMAHT - Rmax after heat treatment; HV_1, HV_2 and HV_3 - Vickers microhardness in the first, second and third series of measurements; DTS - strain corresponding to the strength limit; DYS - strain corresponding to the yield limit; SHF - strain hardening factor.

Figure 13.

- Results of centrality analysis performed using equation (1). a) Group 1; b) Group 2; c) Group 3. Where T - heat treatment temperature; H - actual specimen thickness; W - actual specimen width; EY - Young’s modulus; ET - secant modulus; YS - yield strength; TS - tensile strength; RABHT - Ra before heat treatment; RZBHT - Rz before heat treatment; RMBHT - Rmax before heat treatment; RAAHT - Ra after heat treatment; RZAHT - Rz after heat treatment; RMAHT - Rmax after heat treatment; HV_1, HV_2 and HV_3 - Vickers microhardness in the first, second and third series of measurements; DTS - strain corresponding to the strength limit; DYS - strain corresponding to the yield limit; SHF - strain hardening factor.

Centrality analysis carried out by equations (1)-(3) shows that when moving from group (1) to group (3), the parameter that gives the greatest contribution to the correlations between the variables present in the data set changes. In group 1, the most significant parameter is the Rz determined after heat treatment, in group 2 the strain hardening coefficient, and in group 3 the Young’s modulus. In group 1, the actual specimen width and HV_1 have zero relationships. In group 2, there are no variables with no relationships. In group 3, the actual width of the specimen does not have any linkage.

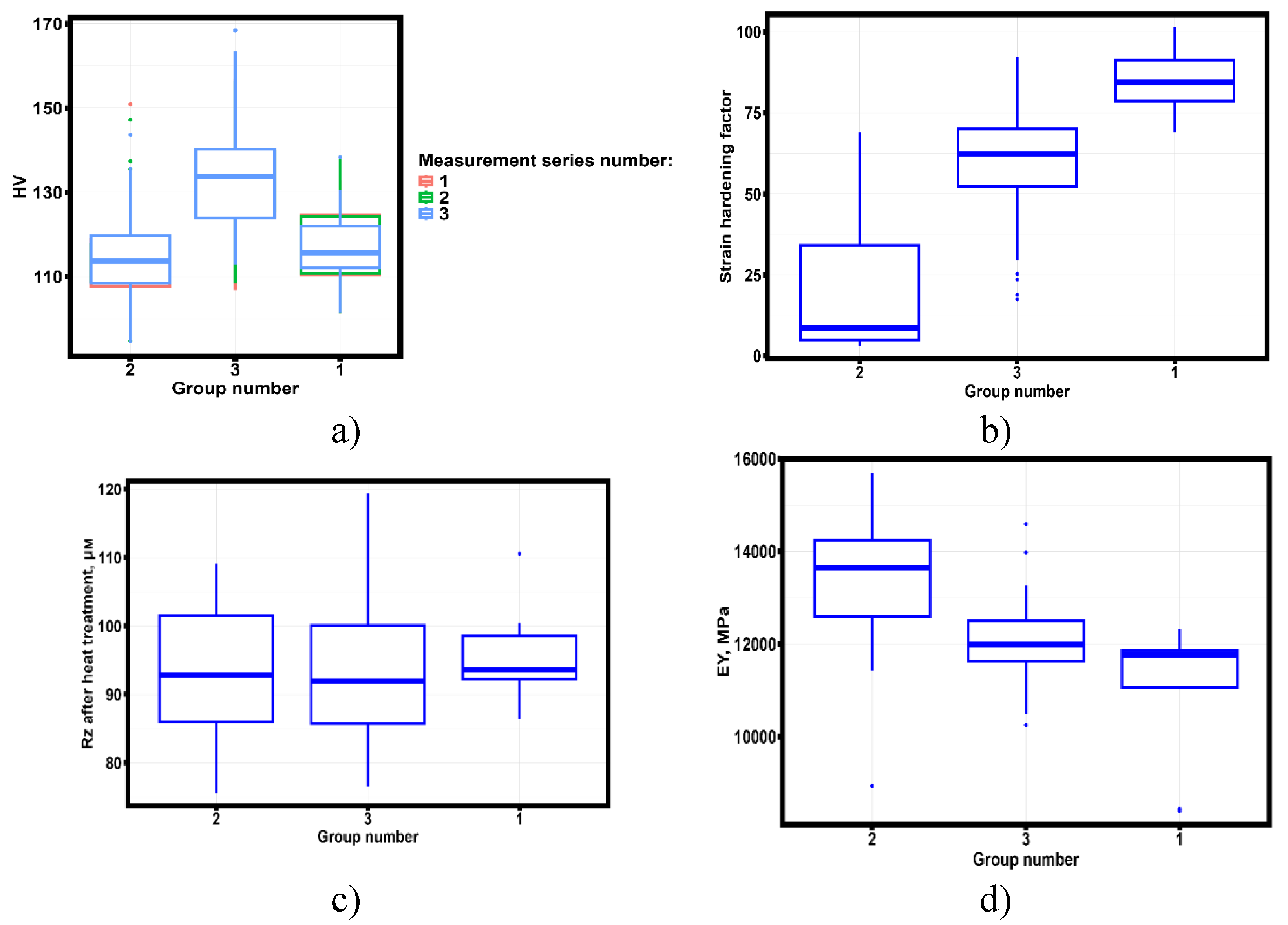

Figure 13 shows Tukey diagrams for the newly identified data groups for microhardness, strain hardening factor, Young’s modulus and Rz parameter after heat treatment (the groups are ordered according to the increase of the prevailing heat treatment temperatures in the intervals).

Figure 13.

- Behavior of central parameters selected based on correlation graph analysis in selected groups: a) Change of hardness (HV); b) Change of strain hardening coefficient; c) Change of Rz after heat treatment; d) Change of Young’s modulus (EY).

Figure 13.

- Behavior of central parameters selected based on correlation graph analysis in selected groups: a) Change of hardness (HV); b) Change of strain hardening coefficient; c) Change of Rz after heat treatment; d) Change of Young’s modulus (EY).

According to the results of the analysis, it can be assumed that the correlation between microhardness and surface roughness parameters is an intermediate link (

Figure 12 A) linking strain hardening and elastic properties of studied samples. The analysis of statistical significance differences in the selected groups shows that the parameter Rz after heat treatment has no statistically significant differences, Young’s modulus is statistically significantly different in group 2 from group 3 and group 1 (p-value<0.05) and does not differ in group 3 and group 1 (p-value >0.05). The behavior of microhardness and strain hardening coefficient are statistically significantly different in all three groups (p-value<0.05). Based on the results of the analysis, we can construct explanatory robust regression equations linking the constant value of Rz after heat treatment with microhardness, strain hardening coefficient and Young’s modulus. The same equations can be obtained for the relationship between microhardness, Young’s modulus, strain hardening coefficient and heat treatment temperature. Robust regression equations linking the parameters having non-zero centrality determined by equations (1)-(3) and the parameter having the maximum number of links. In computing the robust regression equations, normalization [

68,

69,

70] of the data was performed to allow comparison of the contributions of the variables to the explanation of the central variable. The robust regression equation in group 1 is as follows:

where T - heat treatment temperature; H - actual specimen thickness; W - actual specimen width; EY - Young’s modulus; ET - secant modulus; YS - yield strength; TS - tensile strength; RABHT - Ra before heat treatment; RZBHT - Rz before heat treatment; RMBHT - Rmax before heat treatment; RAAHT - Ra after heat treatment; RZAHT - Rz after heat treatment; RMAHT - Rmax after heat treatment; HV_1, HV_2 and HV_3 - Vickers microhardness in the first, second and third series of measurements; DTS - strain corresponding to the strength limit; DYS - strain corresponding to the yield limit; SHF - strain hardening factor.

The robust regression equation describing the relationship between the strain hardening coefficient and the rest of the parameters studied in group 2 is as follows:

where T - heat treatment temperature; H - actual specimen thickness; W - actual specimen width; EY - Young’s modulus; ET - secant modulus; YS - yield strength; TS - tensile strength; RABHT - Ra before heat treatment; RZBHT - Rz before heat treatment; RMBHT - Rmax before heat treatment; RAAHT - Ra after heat treatment; RZAHT - Rz after heat treatment; RMAHT - Rmax after heat treatment; HV_1, HV_2 and HV_3 - Vickers microhardness in the first, second and third series of measurements; DTS - strain corresponding to the strength limit; DYS - strain corresponding to the yield limit; SHF - strain hardening factor.

The robust regression equation describing the relationship between the strain hardening coefficient and the rest of the parameters studied in group 3 is as follows:

where T - heat treatment temperature; H - actual specimen thickness; W - actual specimen width; EY - Young’s modulus; ET - secant modulus; YS - yield strength; TS - tensile strength; RABHT - Ra before heat treatment; RZBHT - Rz before heat treatment; RMBHT - Rmax before heat treatment; RAAHT - Ra after heat treatment; RZAHT - Rz after heat treatment; RMAHT - Rmax after heat treatment; HV_1, HV_2 and HV_3 - Vickers microhardness in the first, second and third series of measurements; DTS - strain corresponding to the strength limit; DYS - strain corresponding to the yield limit; SHF - strain hardening factor.

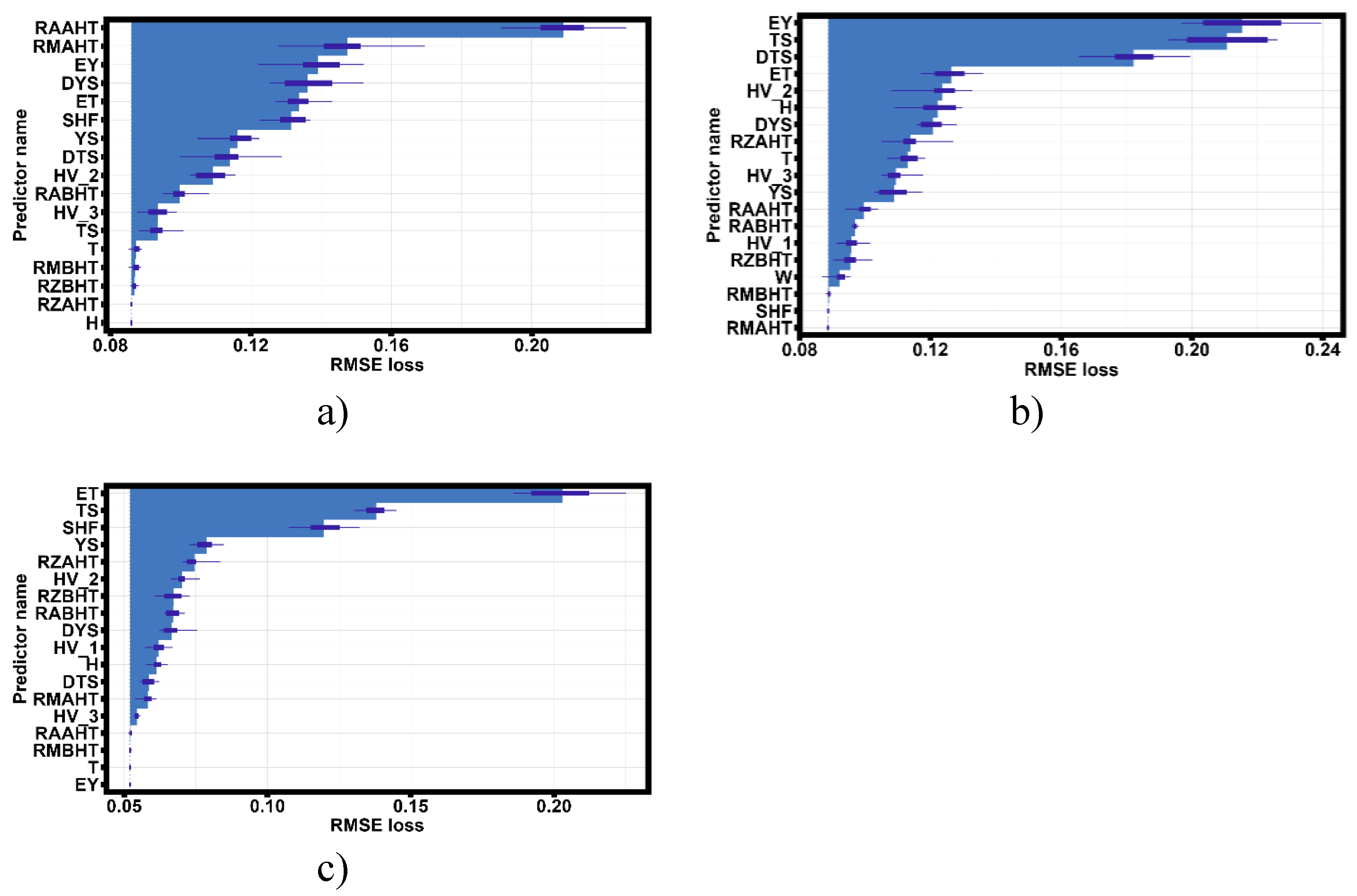

Figure 14 shows the contributions of the variables under study to the accuracy losses of the models described by equations (8)-(10).

Figure 14.

- Evaluation of the influence of explanatory variables on the control parameter in three groups of samples obtained by selective laser melting technique from Al-Mn-Mg-Ti-Zr alloy.

Figure 14.

- Evaluation of the influence of explanatory variables on the control parameter in three groups of samples obtained by selective laser melting technique from Al-Mn-Mg-Ti-Zr alloy.

The analysis of the influence of explanatory variables on the control parameter shows that in group 1 the average surface roughness before heat treatment and the maximum surface roughness before heat treatment have the greatest influence. Whereas the mechanical properties of thin-walled specimens contribute less to explaining the error of equation (8) of which Young’s modulus is the most significant. In group 2 (equation 9), Young’s modulus, tensile strength and strain corresponding to the tensile strength are the most significant contributors in explaining the strain hardening factor. In group 3 (Equation 10), Young’s modules, secant modules, tensile strength and strain-hardening ratio make the largest contribution to the explanation of Young’s modules. For the most significant parameters (except for the average and maximum surface roughness before heat treatment and after heat treatment) empirical equations of robust regression were constructed describing the dependence of the most significant parameters on the heat treatment temperature with confidence intervals determined by bootstrapping methods. The estimation of the best approximation was carried out by the minimum Akaike criterion; polynomials of the first, second and third degree were considered as approximations.

Table 7 shows the dependences of the main parameters on the heat treatment temperature.

Table 8 presents the confidence intervals of the robust regression coefficients of the robust regression equations (11)-(15).

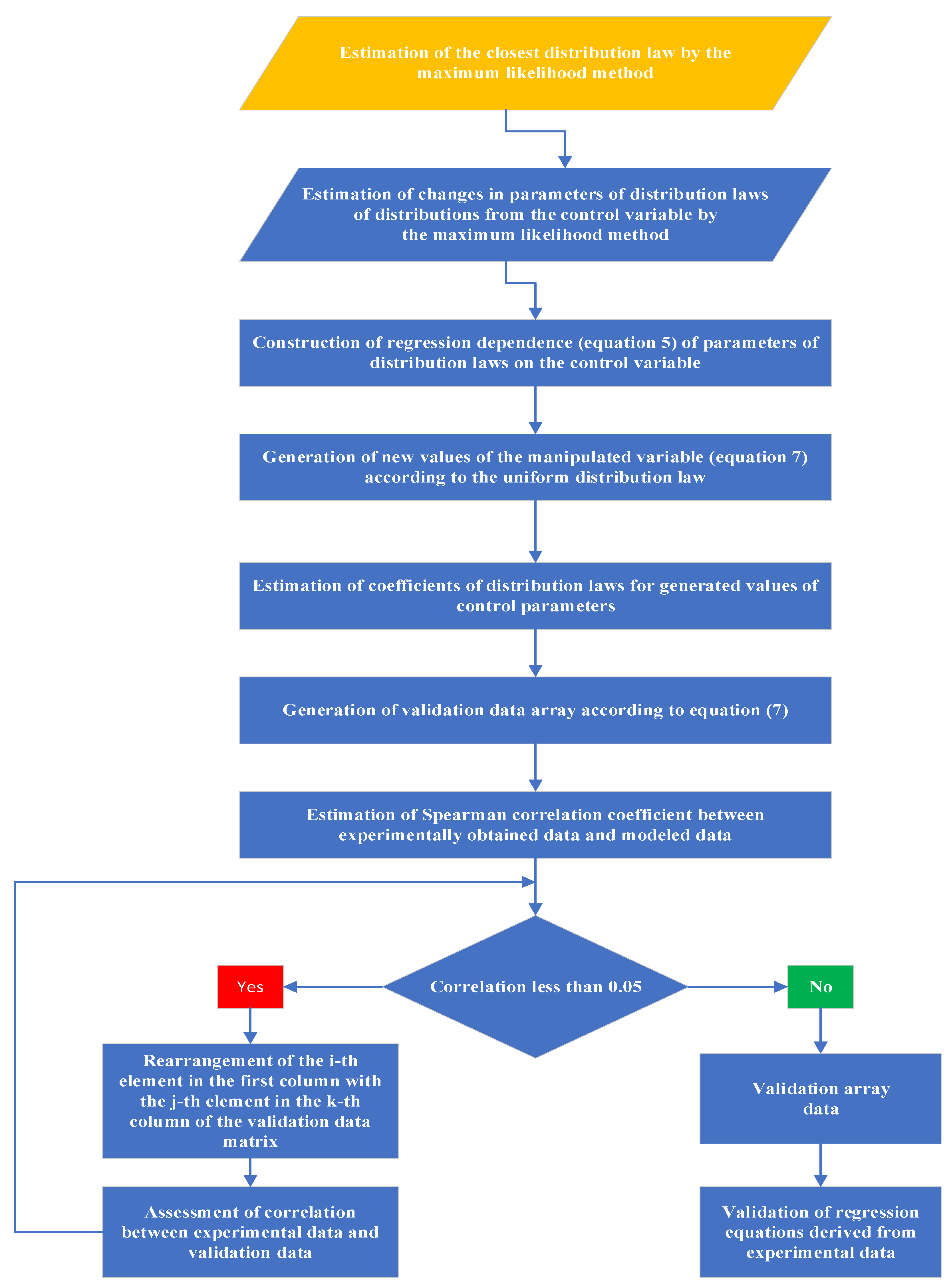

3.3. Monte Carlo statistical modeling

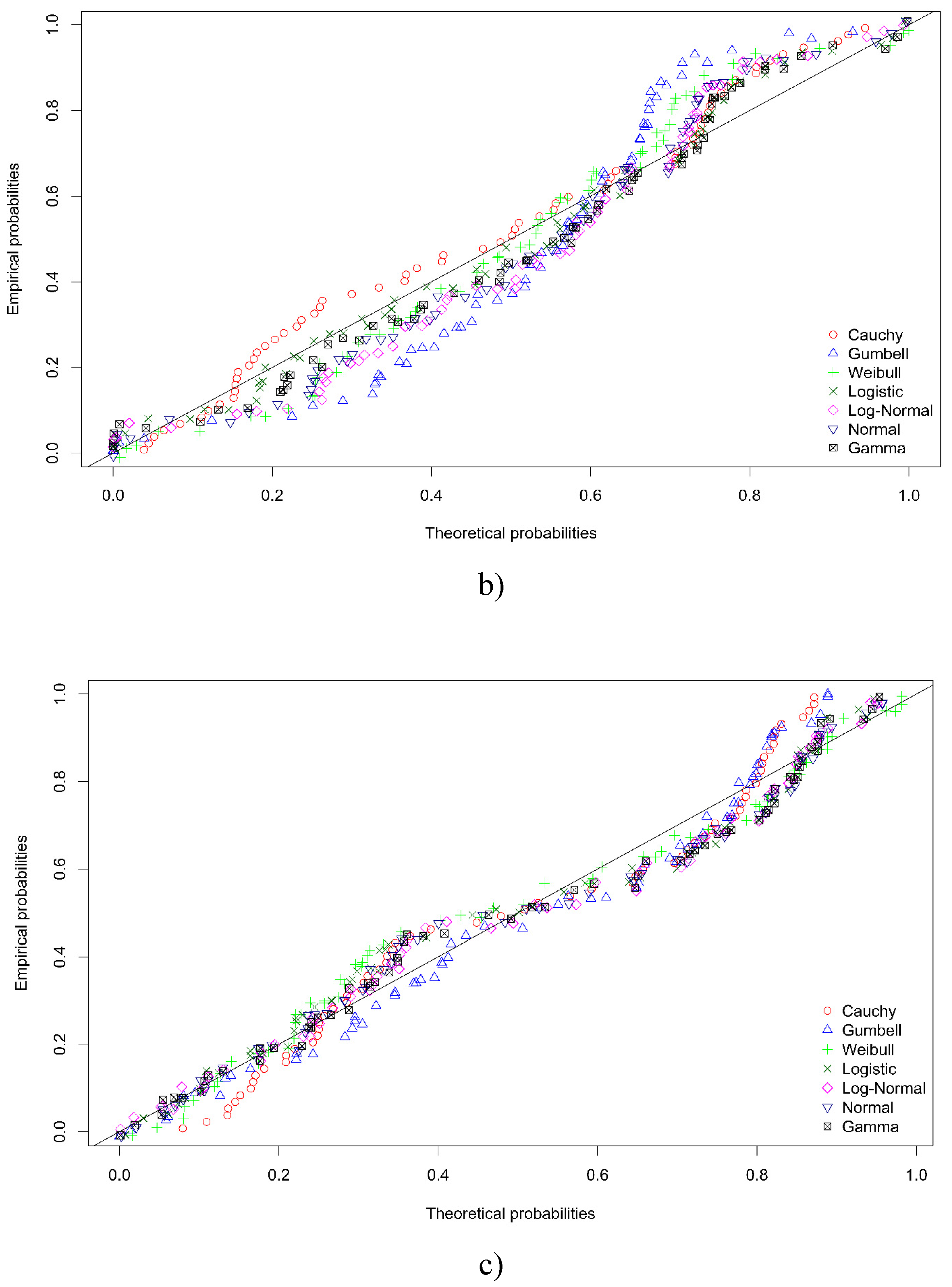

Table 3 presents the results of the evaluation of the closest distribution law of the experimental data by the Akaike and Bayesian information criteria, from which it follows that seven of the eight considered distribution laws are found in the experimental data. To confirm the established closest type of distribution, we evaluated the closeness of seven theoretical laws of distribution to the actual distribution, the results are presented in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

- Comparison of theoretical distribution laws with actual distribution laws of experimental data. A) PDF of Young’s modulus; B) PDF of secant modulus; C) PDF of ultimate strength; D) PDF of strain corresponding to ultimate strength; E) PDF of strain hardening coefficient.

Figure 14.

- Comparison of theoretical distribution laws with actual distribution laws of experimental data. A) PDF of Young’s modulus; B) PDF of secant modulus; C) PDF of ultimate strength; D) PDF of strain corresponding to ultimate strength; E) PDF of strain hardening coefficient.

Table 9 presents the root mean square error between the theoretical and experimental likelihood function.

Comparison of the results of estimation of the mean square deviation of the theoretical distributions from the empirical distributions and the estimations carried out according to the Akaike and Bayesian information criteria coincide for Young’s modulus and secant modulus. Whereas, for the ultimate strength, strain corresponding to the ultimate strength and strain hardening coefficient, the distributions occupying the second place after the distribution laws having the minimum values of the information criteria are the closest. In accordance with recommendations [

72,

73,

74], the distribution laws established based on PDF analysis and bound from above and below by equations (11)-(15) will be used for Monte Carlo simulation.

Table 10 presents the robust regression equations approximating the change in the distribution coefficients as a function of the heat treatment temperature of the samples obtained by selective laser melting technology from Al-Mn-Mg-Ti-Zr alloy.

Figure 15 shows a histogram of the distribution of new annealing temperatures generated from the uniform distribution.

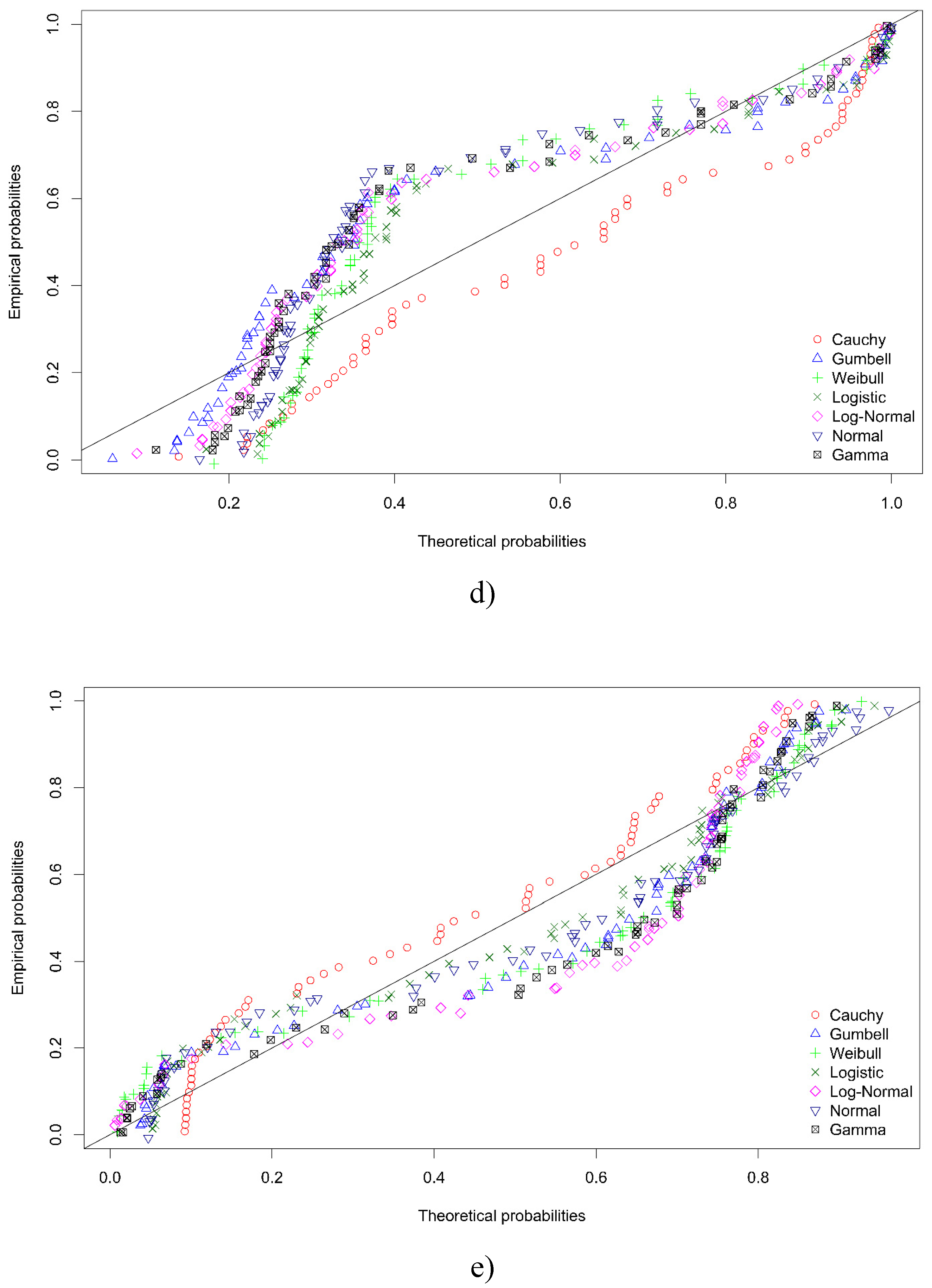

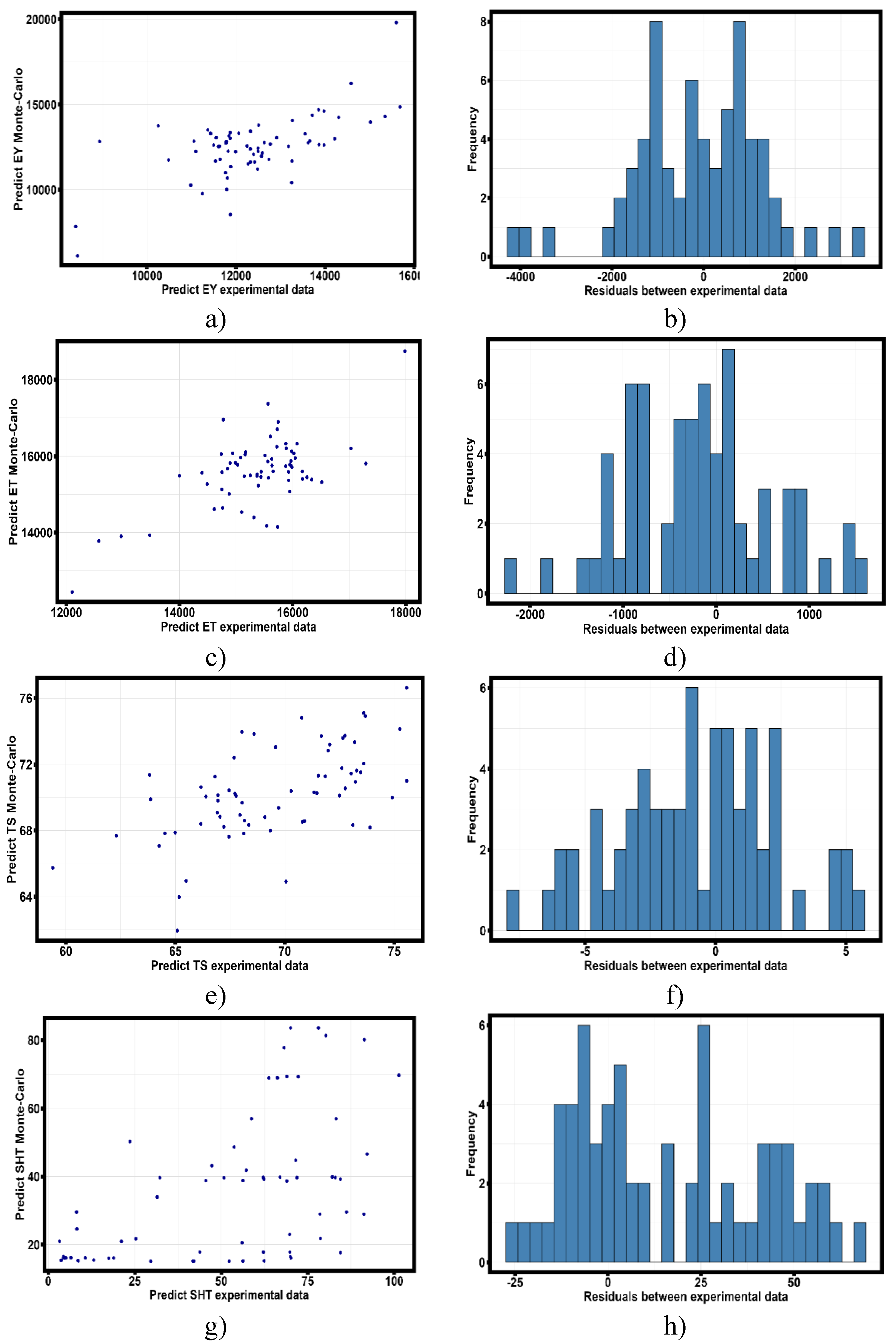

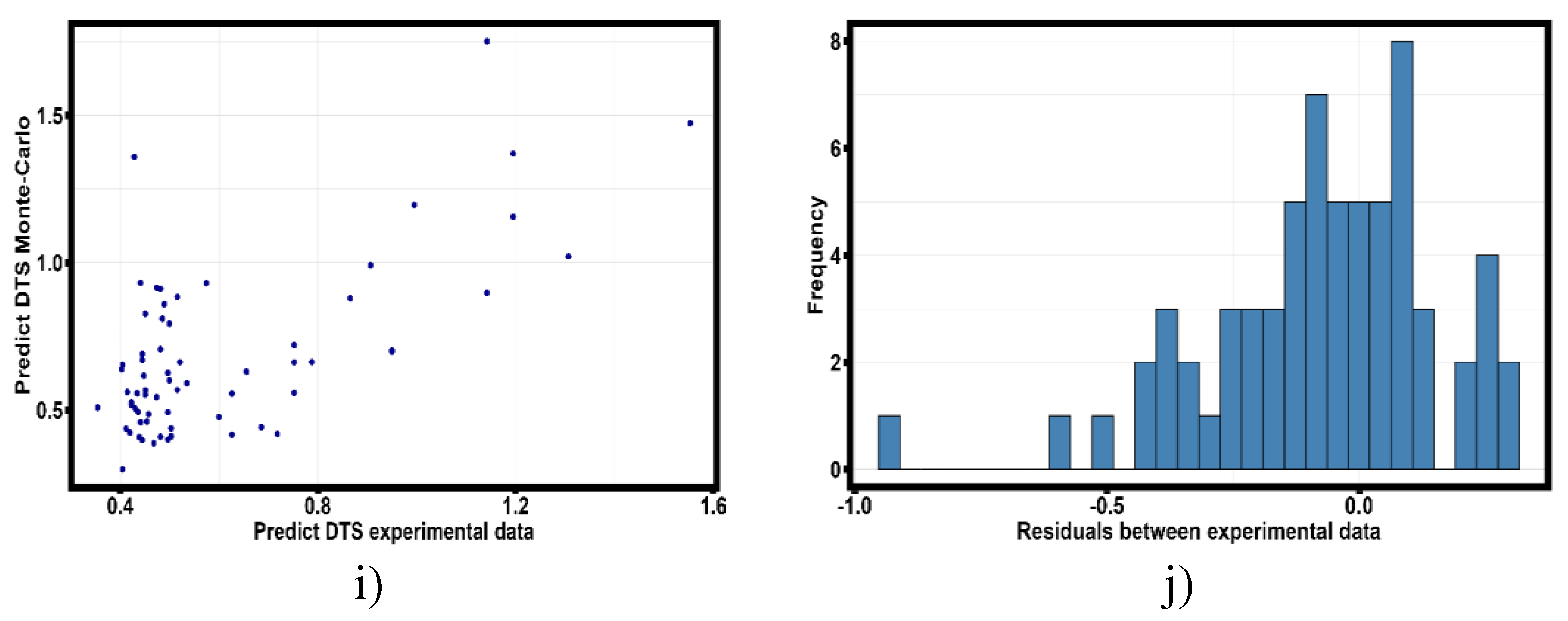

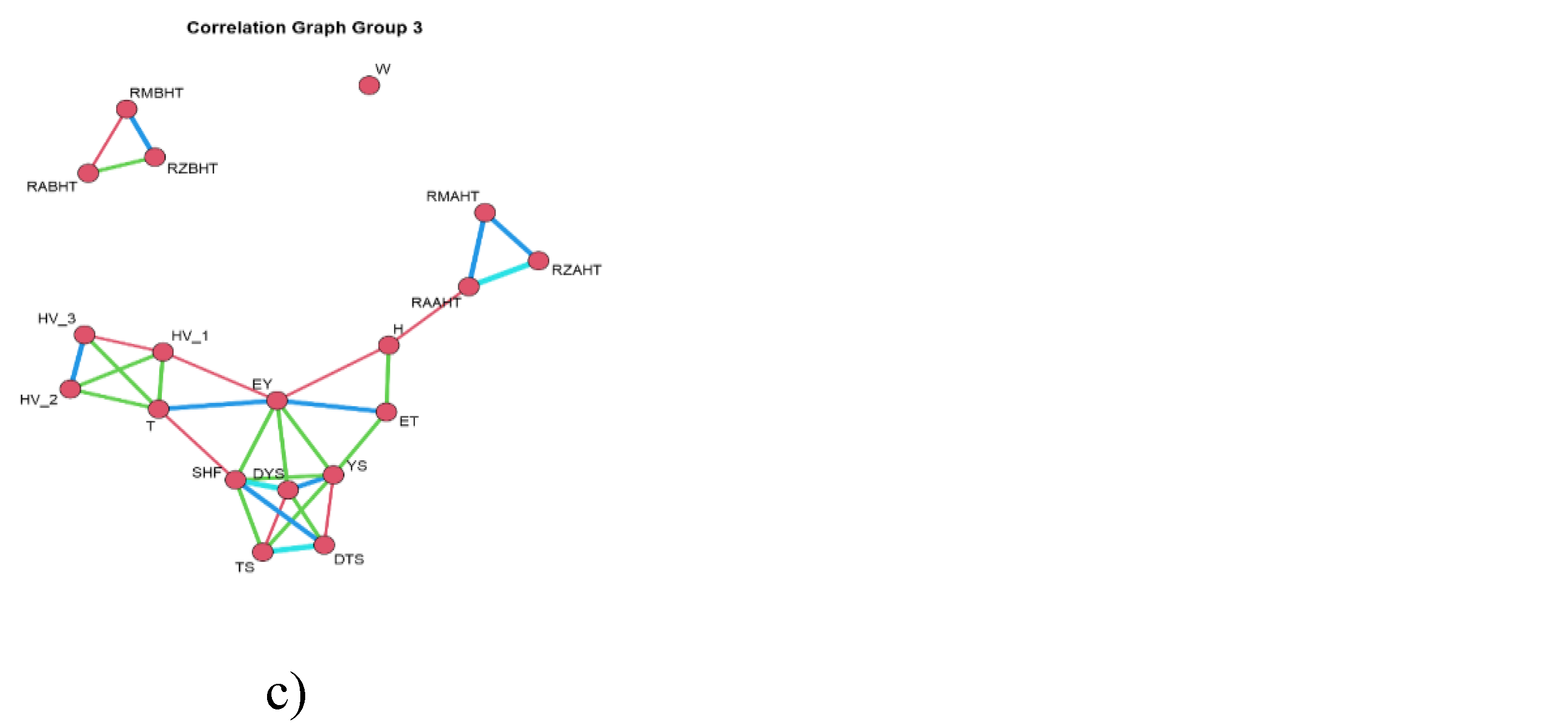

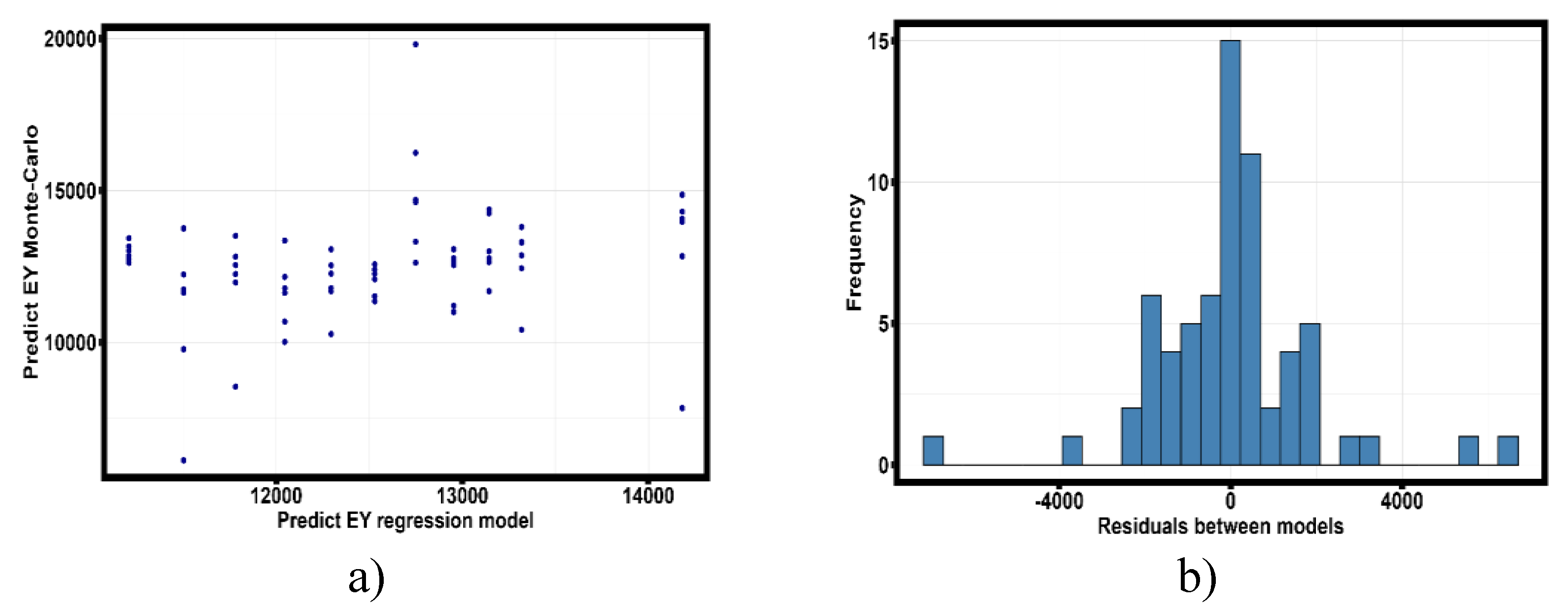

Figure 16 shows plots of dependence on the values predicted by equations (11)-(15) for annealing temperatures generated according to the uniform distribution law from the sample obtained by the Monte Carlo method and a histogram of the scatter of residuals between the model data and the results of prediction by equations (11)-(15).

Figure 17 shows the dependence of data obtained because of Monte Carlo simulation on the values obtained because of tensile tests of thin-walled samples obtained by selective laser melting technology from Al-Mn-Mg-Ti-Zr alloy.

Figure 17.

- Dependence of experimental values of the most significant quantities selected based on the analysis of robust regression equations (8)-(10) on the values obtained by Monte Carlo method. a) Scatter diagram of the predicted values of Young’s modulus; b) Histogram of the distribution of the residuals of the difference of two models; c) Scatter diagram of the predicted values of modulus along the secant; d) Histogram of the distribution of the residuals of the difference of models; e) Scatter diagram of the predicted values of ultimate strength; f) Histogram of the distribution of residuals; g) Scatter diagram of the predicted values of strain hardening coefficient; h) Histogram of the distribution of residuals of models; i) Scatter diagram of the predicted values of strain corresponds to the values of the strain hardening coefficient; j) Histogram of the distribution of residuals of models;.

Figure 17.

- Dependence of experimental values of the most significant quantities selected based on the analysis of robust regression equations (8)-(10) on the values obtained by Monte Carlo method. a) Scatter diagram of the predicted values of Young’s modulus; b) Histogram of the distribution of the residuals of the difference of two models; c) Scatter diagram of the predicted values of modulus along the secant; d) Histogram of the distribution of the residuals of the difference of models; e) Scatter diagram of the predicted values of ultimate strength; f) Histogram of the distribution of residuals; g) Scatter diagram of the predicted values of strain hardening coefficient; h) Histogram of the distribution of residuals of models; i) Scatter diagram of the predicted values of strain corresponds to the values of the strain hardening coefficient; j) Histogram of the distribution of residuals of models;.

Evaluation of linear dependence between experimentally obtained results, robust regression models and results predicted by Monte Carlo method is presented in

Table 12. The estimation was carried out by Pearson correlation coefficient.

The results of correlation analysis show that the model based on the Monte Carlo method agrees better with the experimental data than the empirical model based on robust regression. Provided that the validation heat treatment temperature obeys a uniform distribution law. The exception is the prediction of the strain hardening coefficient, the robust regression equation describes the strain hardening coefficient more accurately, which may be the subject of refinement of the empirical Monte Carlo model.

3.4. Discussion

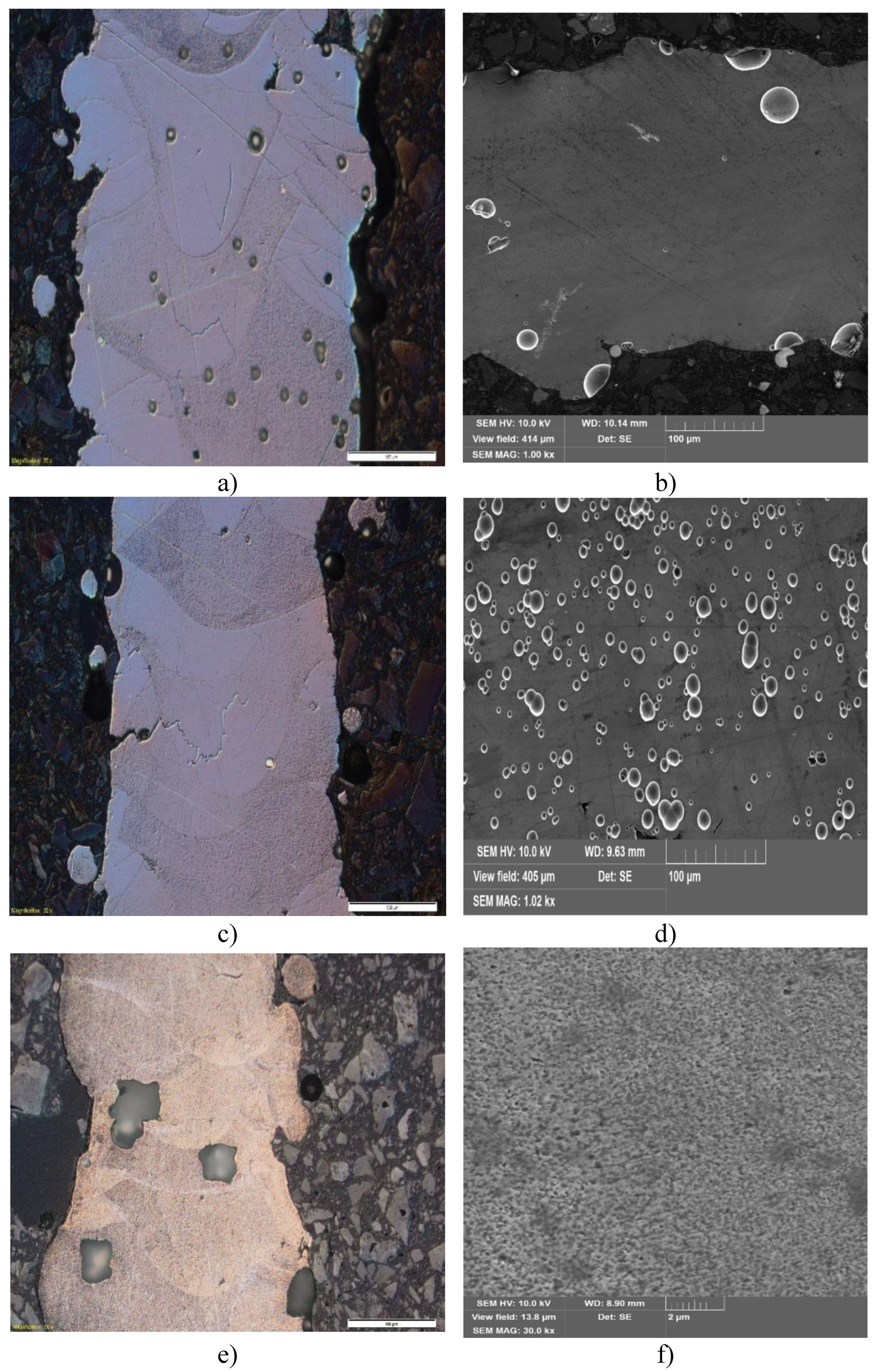

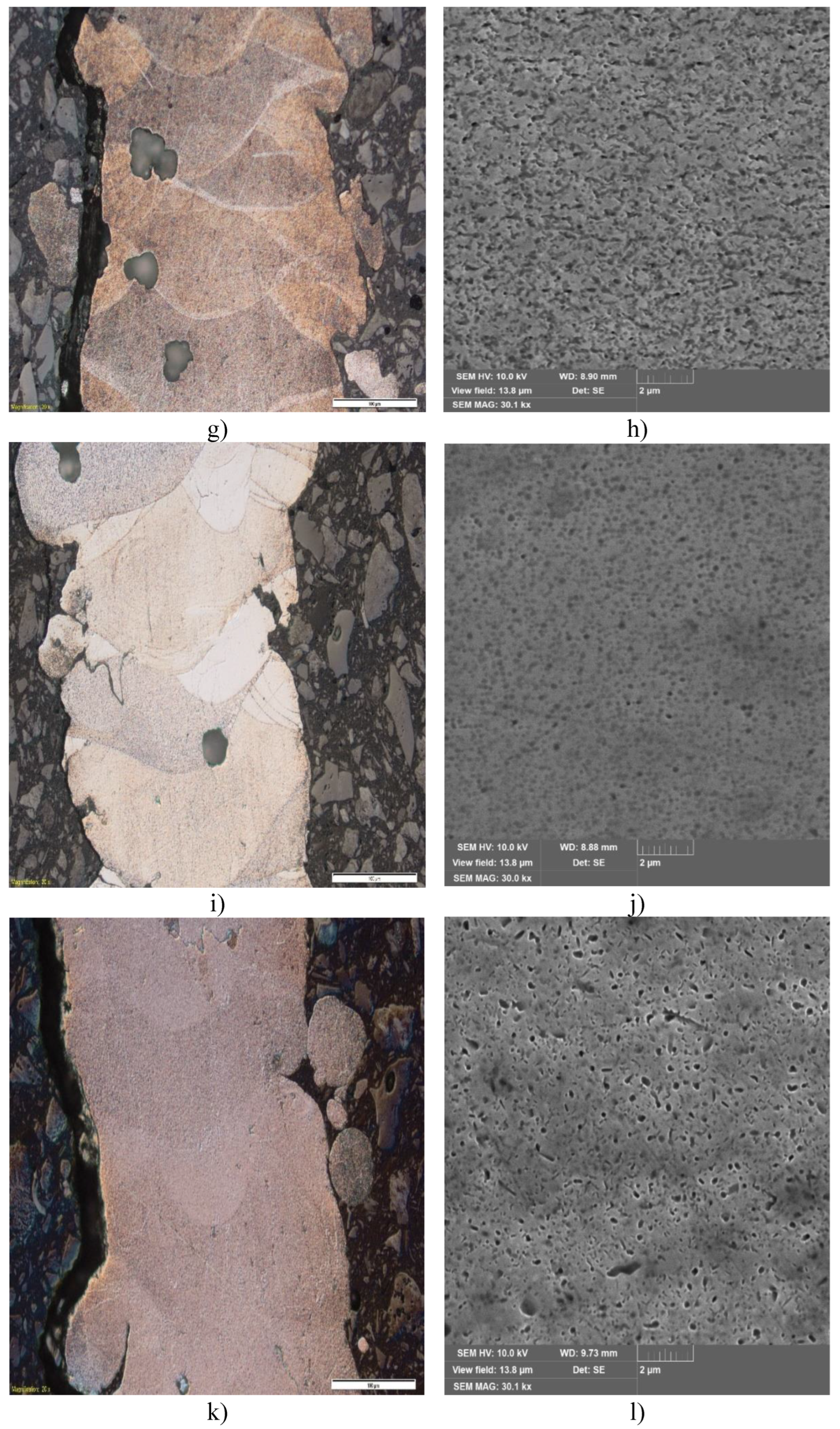

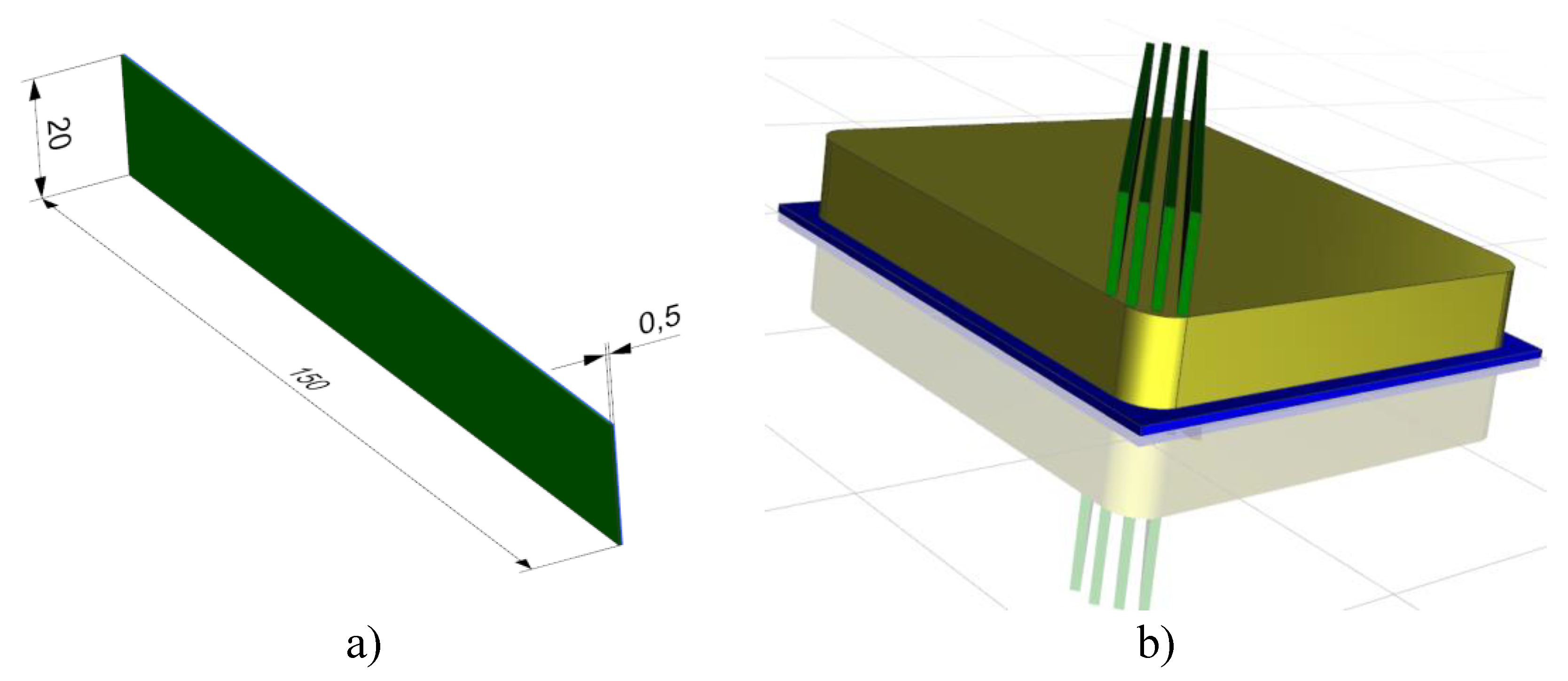

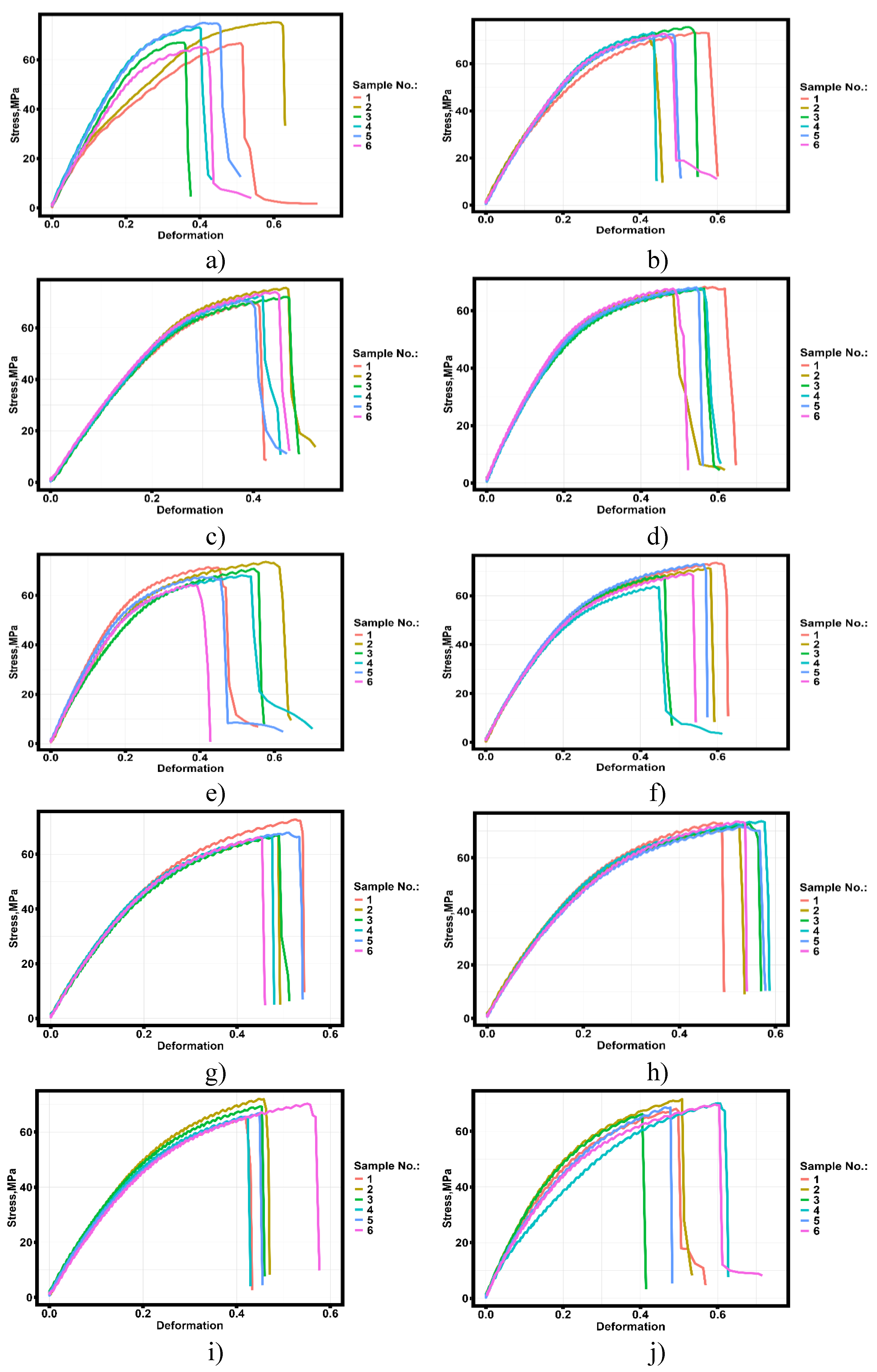

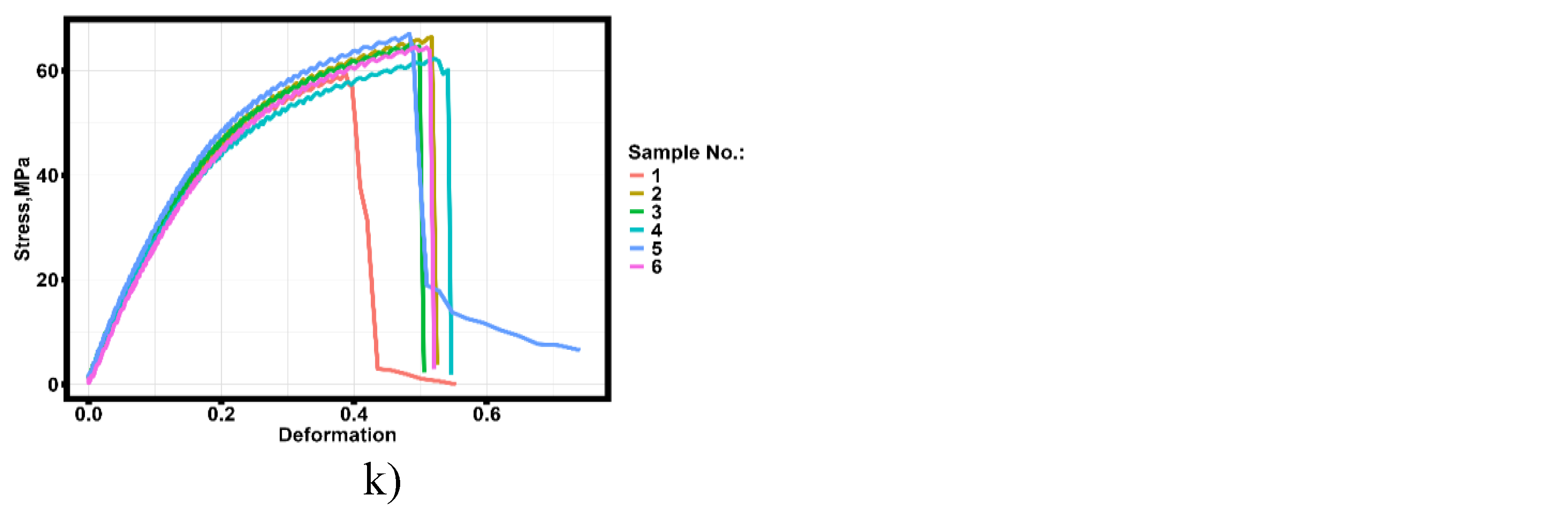

Statistical analysis of the results of tensile tests of specimens made by selective laser melting technology from Al-Mn-Mg-Ti-Zr alloy and subjected to heat treatment at temperatures from 260 ºC to 530 ºC within an hour showed that at temperatures of heat treatment from 20 ºC to 290 ºC the parameter having the largest number of statistically significant relationships is the strain hardening coefficient (Figure 13 B). At the same time, the analysis of the dependence of the strain hardening coefficient on the heat treatment temperature shows continuous growth with increasing temperature. Such behavior of the investigated value may indicate different mechanisms of strain hardening of samples subjected to heat treatment at temperatures from 260 ºC to 530 ºC. To identify the reasons for the growth of strain hardening coefficient, metallographic and X-ray phase analysis of thin-walled samples obtained by selective laser melting technology was carried out. Figure 17 shows the results of metallographic analysis of thin-walled samples subjected to heat treatment at different temperatures.

Figure 17.

- Optic (left column) and SEM (right column) images of thin-walled samples fabricated by selective laser melting of Al-Mn-Mg-Ti-Zr alloy. A), B) Without heat treatment; C), D) Heat treatment at 290 °C; E), F) Heat treatment at 320 °C; G), H) Heat treatment at 410 °C; I), J) Heat treatment at 470 °C; K), L) Heat treatment at 530 °C.

Figure 17.

- Optic (left column) and SEM (right column) images of thin-walled samples fabricated by selective laser melting of Al-Mn-Mg-Ti-Zr alloy. A), B) Without heat treatment; C), D) Heat treatment at 290 °C; E), F) Heat treatment at 320 °C; G), H) Heat treatment at 410 °C; I), J) Heat treatment at 470 °C; K), L) Heat treatment at 530 °C.

The analysis of presented images shows that the number of macropores and microcracks in the samples decreases with increasing heat treatment (Figure 17 A, D). After the temperature of 290 ºC (Figure 17 D, E) there are agglomerations (dark inclusions) at the melt bath boundaries and there are no macropores, but there are micropores. Comparing the results of metallographic analysis with the results of statistical analysis, the samples without heat treatment and heat treated at 260 ºC and 290 ºC fell into the same group (group 2

Table 6) and had the most significant mechanical property - strain hardening coefficient. It was shown on model specimens [

30] that the strain hardening coefficient increases almost twofold when the size of macrodefects decreases. Accordingly, the increase in strain hardening coefficient observed in Figure 13b can be explained through the mechanism of macrodefect reduction. This conclusion is confirmed, among other things, by the results of X-ray phase analysis.

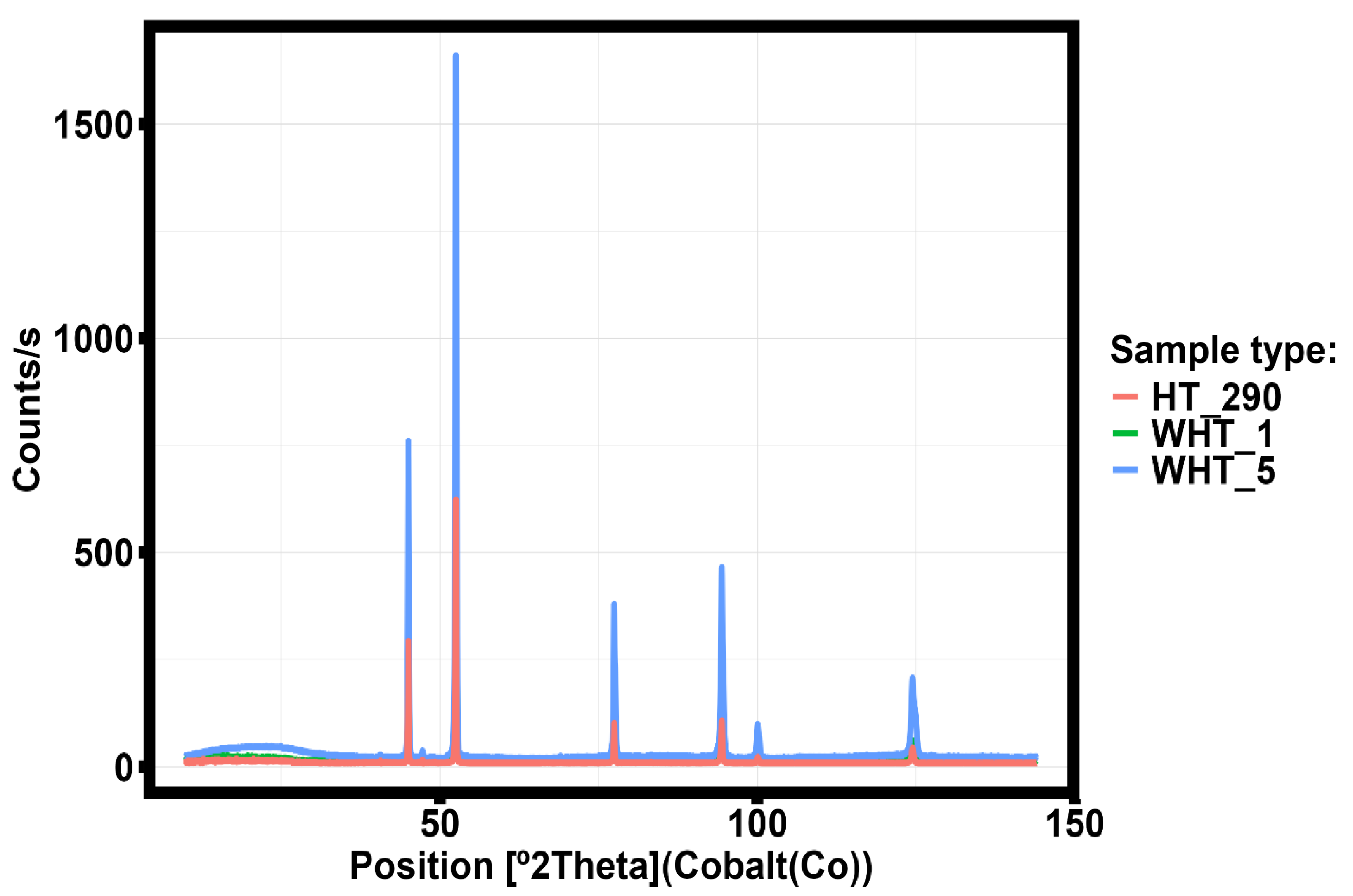

Figure 18 shows the results of XRD analysis corresponding to the samples without and with heat treated and at 290 ºC for one hour.

Changes in the intensity of the peaks observed in the X-ray diagram (

Figure 18) are associated with an increase in the concentration of manganese precipitating from the solid solution of aluminum and forming a compound with oxygen.

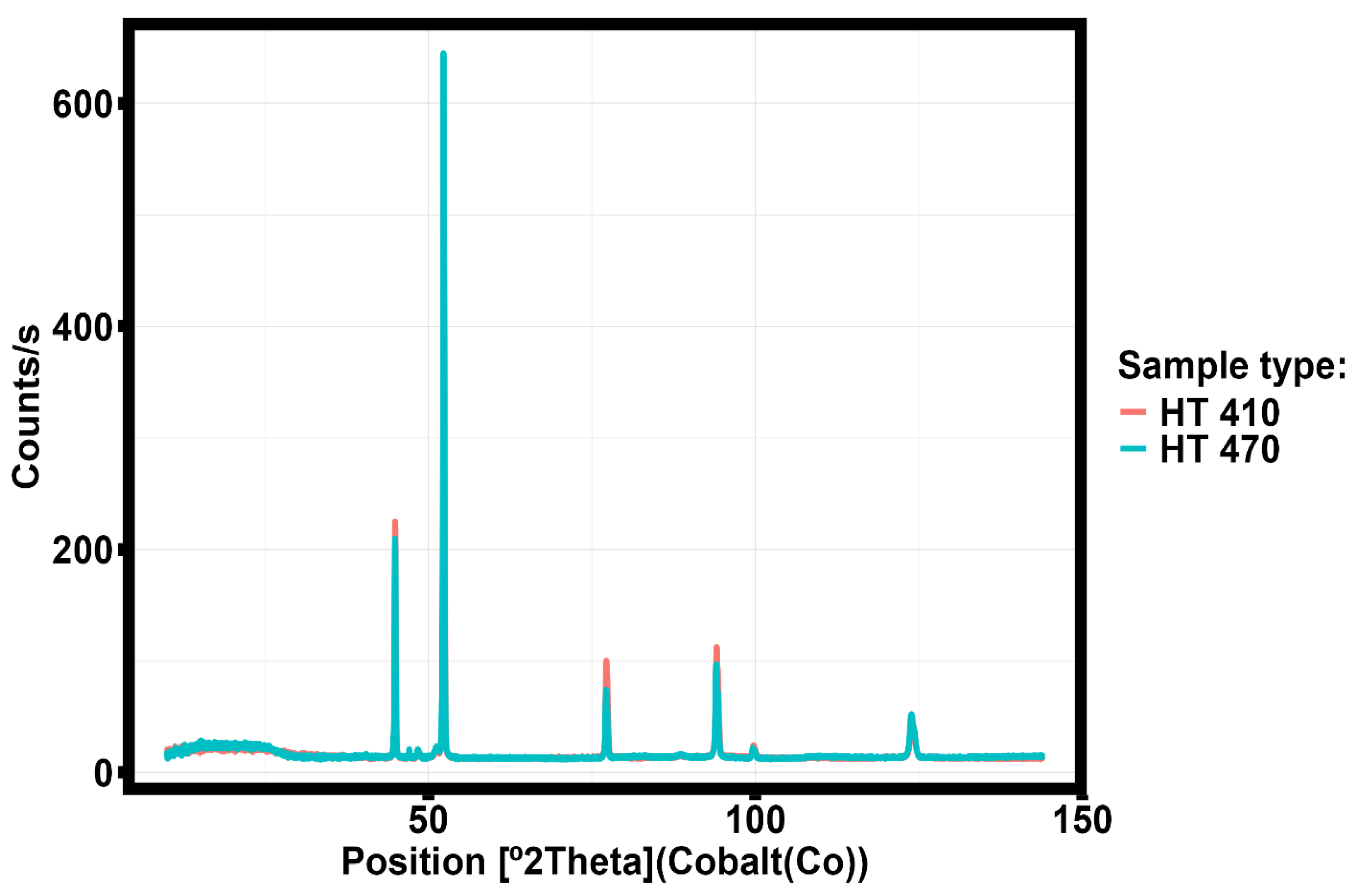

At higher heat treatment temperatures, in addition to the concentration of defects at the van-melt boundaries, the formation of light (white) zones at the van-melt boundary is observed (Figure 19 D and G). The formation of these areas is associated with intensive precipitation of manganese and magnesium with subsequent formation of oxides.

Figure 20 shows the X-ray diffraction pattern of sample heat-treated at 410 ºC and 470 ºC.

The statistical analysis shows that for the samples in group 3, the parameter with the largest number of statistically significant correlations is Young’s modulus, and in second place is the strain hardening coefficient (Figure 13 C). That in combination with the results presented in Figure 17 indicates that the precipitation of manganese and magnesium oxides on the melt bath boundaries reduce the elastic properties of the samples and to a lesser extent (than the reduction of macro-defectivity) contributes to the increase in the strain hardening coefficient.

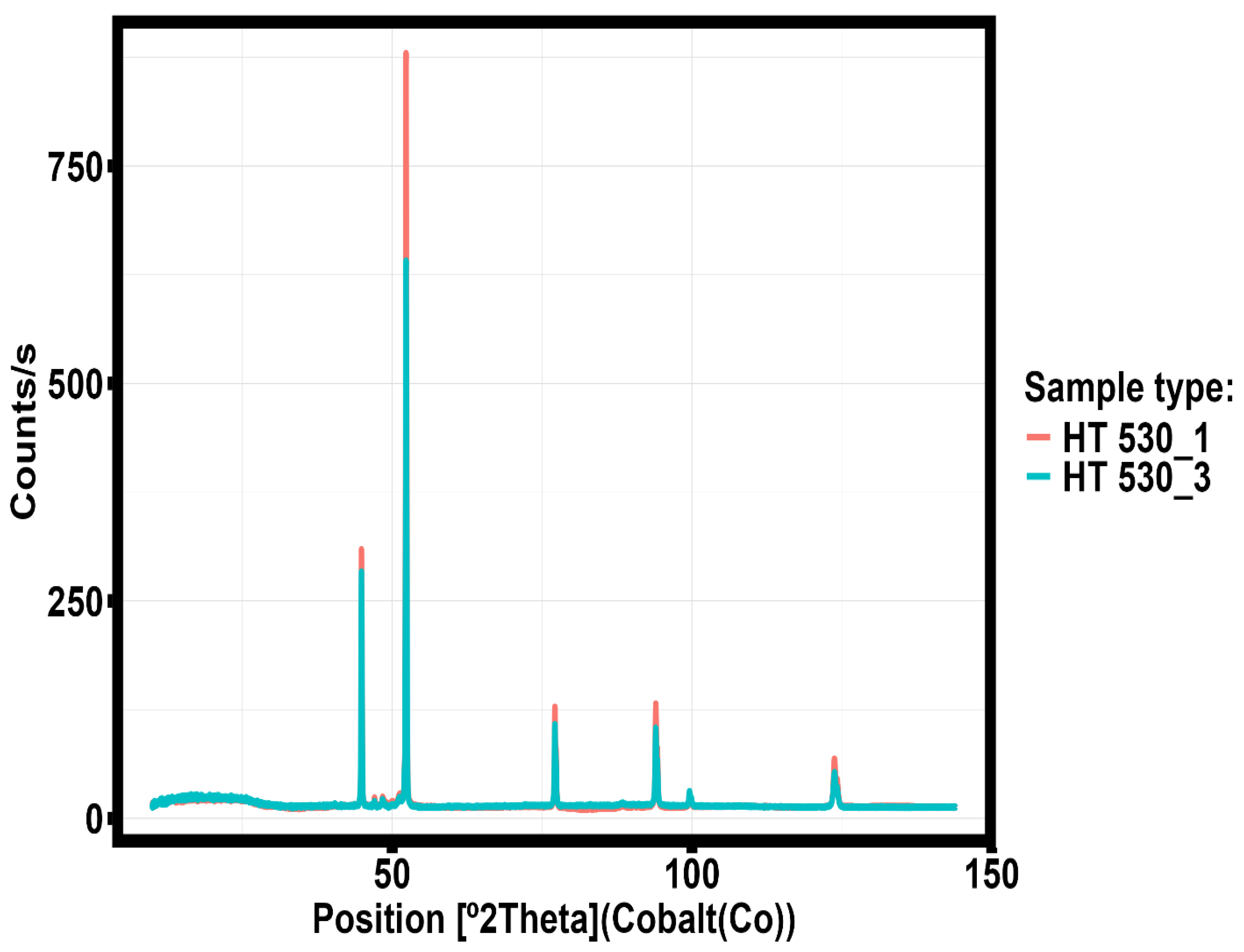

Further increase in the temperature of heat treatment of thin-walled samples obtained by selective laser melting technology leads to the precipitation of pure titanium with hexagonal crystallographic structure from the solid solution and the formation of intermetallic phase Mg

8Al

16 and further decrease in the level of macrodefectivity.

Figure 21 shows the X-ray radiography of sample heat-treated at 530 ºC for 1 hour.

Statistical analysis of the results showed that for specimens in the first group, the greatest number of statistically significant correlations is observed for the sum of heights of the largest protrusions and depths of the largest depressions of the surface roughness profile within the base length of the specimen (Rz) given by Eq:

where

– height of i-th protrusion of surface roughness profile;

– depth of the i-th depression of the surface roughness profile.

Why is the highest statistically significant correlation achieved after heat treatment at 530 ºC between the parameter Rz and microhardness (

Figure 11 A). Simultaneously with this fact, microstructural analysis shows the presence of a more homogeneous structure with a small number of micropores, and the results of XRD analysis show that the formation of intermetallic phases and the precipitation of titanium and zirconium from the solid solution. It follows that micropores formed because of selective laser melting during high-temperature heat treatment are shifted to the melt bath boundary with subsequent exit to the sample surface.

Analysis of microhardness behavior (Figure 13 a) shows that group 2 with low heat treatment temperature has the lowest microhardness for the three series of measurements. But the change of sign of the robust regression coefficient (Equation 9) at different series of microhardness measurements shows that each series of measurements falls into different phases contributing positively or negatively to the explanation of the strain hardening coefficient. However, these differences are not statistically significant, which suggests that the distribution of phases is not large and uniform around indenter penetration during measurements. A similar situation is observed in group three, considering the results (Figure 13 a), it can be stated that the amount of microhardness increasing phase increases and the sign of the contribution to the explanation of Young’s modulus (Equation 10) does not change (Equation 9). The decrease in microhardness of samples in group 1 and the change in the contribution of the measurement series (Equation 8) shows that the microstructure of the samples undergoes significant changes compared to group 2 and 3.

The cumulative analysis of the results of the conducted studies shows that at increasing the temperature of heat treatment micropores (macrodefects) are shifted to the boundary of the melt zones with subsequent exit to the surface, which together with the formation of intermetallic phase and the release of titanium and zirconium leads to strain hardening of thin-walled samples obtained by selective laser melting of Al-Mn-Mg-Ti-Zr alloy.

The analysis of the results of modeling the variables contributing the main contribution to the prediction error of the parameters having the maximum number of correlations (equations 8-10) shows that in most cases the semi-empirical model based on the Monte Carlo method and Latin Hypercube more accurately describes the experimental data compared to the robust regression model (equations (11)-(15)). The exception is the behavior of the strain hardening coefficient (

Table 12). During the modeling process, it was found that increasing the number of simulated specimens to 100 increases the Pearson correlation coefficient to 0.93. Thus, further research in the construction of a semi-empirical Monte Carlo model will be aimed at harmonizing the volume of experimental and generated samples to improve the accuracy of the model.