Submitted:

22 April 2025

Posted:

22 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- -

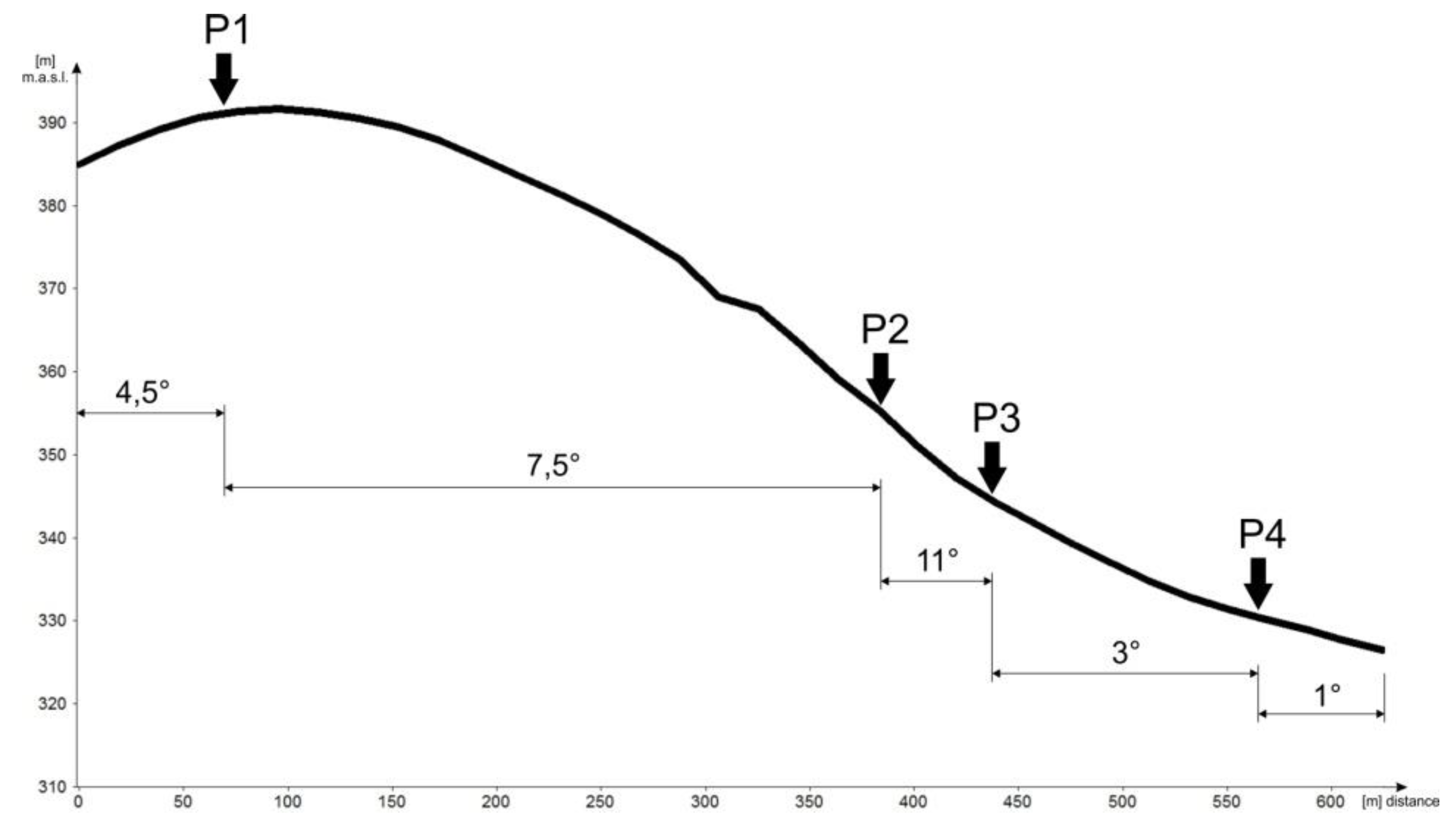

- On cultivated slopes, rendzina solum thickness is inversely related to inclination. On 11° convex slopes, a 25 cm Ap horizon directly overlies bedrock, while on flat hilltops, soil processes extend to 48 cm.

- -

- Non-skeletal deluvium (profile P-4) to 1 m depth contains 1.0-3.8% CaCO3 and 0.55-1.11 % Corg, exhibiting redoxymorphic processes at depth.

- -

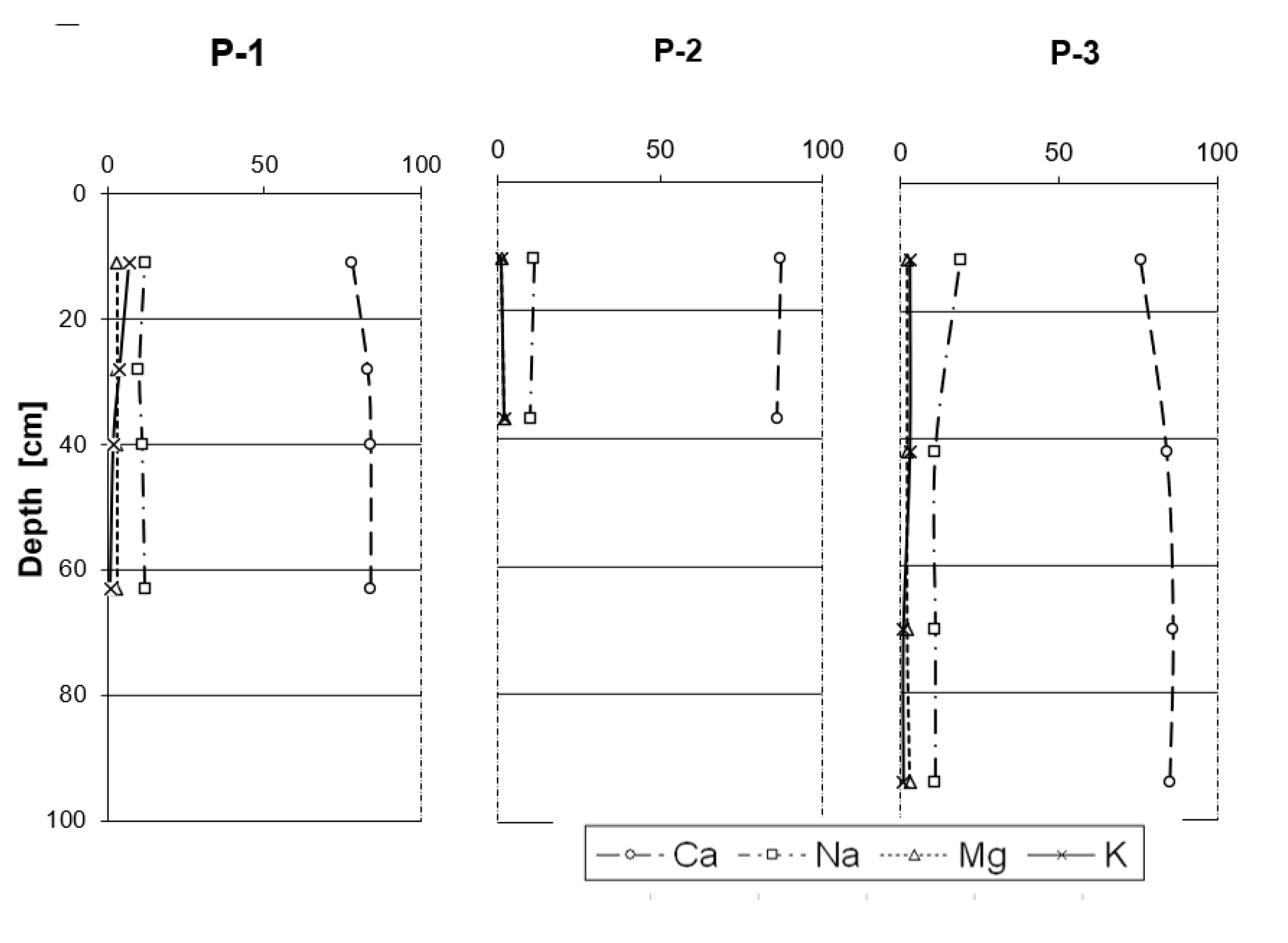

- Cultivated rendzinas on slopes show slight surface acidification, with sodium comprising approximately 10% of the sorption complex, irrespective of terrain location.

- -

- These rendzinas are characterized by high total iron content (up to 4.5%, locally 9.5% Fe) and a reddish hue (2.5 YR), with soil humus reducing brightness (value) and iron oxide reduction lowering color purity (chroma).

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abakumov, E. Rendzinas of the Russian Northwest: Diversity, Genesis, and cosystem Functions: A Review. Geosciences 2023, 13(7), 216. [CrossRef]

- Smoliková, L.; Ložek, V. Zur Altersfrage der miteleuropȁischen Terrae calcis. Eiszeitalter und Gegenwart 1962, 13, 155-177.

- Velde, B. Surface cracking and aggregate formation observed in a rendzina soil, La Touche (Vienne) France. Geoderma 2001, 99 (3-4), 261-276.

- Zasoński, S. Gleby wapniowcowe wytworzone z wybranych ogniw litostratygraficznych fliszu Wschodnich Karpat. Cz I. Ogólna charakterystyka gleb. Roczniki Gleboznawcze 1993, 44 (3-4), 121-133.

- Kabala, C. Rendzina (redzina) – Soil of the Year 2018 in Poland. Introduction to origin, classification and land use of rendzinas. Soil science annual 2018, 69 (2), 63-74.

- Bielek, P.; Šurina, B. Malý atlas pôd Slovenska. VÚPOP: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2000; p. 36.

- Dobrzański, B.; Konecka-Betley, K.; Kuźnicki, F.; Turski, R. Rędziny Polski. Roczn. Nauk Roln., ser. D, Poland, 1987; p. 143.

- FAO/UNESCO. Soil Map of the World. Revised legend with corrections and updates. ISRIC Press. Wageningen, The Netherlands. 1997.

- Sladkova, J. An Analysis of the Rendzina Issue in the Valid Czech Soil Classification System. Soil and Water Research 2009, 4 (2), 66-82. [CrossRef]

- Torrent, J.; Schwertmann, U.; Fechter, H.; Alferez F. Quantitative relationships between soil color and hematite content. Soil Science 1983, 136 (6), 354-358. [CrossRef]

- Torrent, J.; Cabedo, A. Sources of iron oxides in reddish brown soil profiles from calcarenties in southern Spain. Geoderma 1986, 37 (1), 57-66. [CrossRef]

- Sandler, A.; Taitel-Goldman, N.; Ezersky, V. Sources and formation of iron minerals in eastern Mediterranean coastal sandy soils – A HRTEM and clay mineral study. Catena 2023, 220(7), 106644. [CrossRef]

- Leviel, B.; Gabrielle, B.; Justes, E.; Mary, B.; Gosse, G. Water and nitrate budgets in a rendzina cropped with oilseed rape receiving varying amounts of fertilizer. European Journal of Soil Science 1998, 49 (1), 37-51.

- Wójcikowska-Kapusta, A.; Niemczuk, B. Wpływ sposobu użytkowania na zawartość różnych form magnezu i potem w profilach rędzin. Acta Agrophysica 2006, 8 (3), 765-771.

- Sokouti, R.; Razagi, S. Erodibility and loss of marly drived soils. Eurasian Journal of Soil Science 2015, 4 (4), 279-286. [CrossRef]

- Weihrauch, Ch.; Opp, Ch. Soil phosphorus dynamics along a loess-limestone transect in Mihla, Thuringia (Germany). Journal of Plant Nutrition & Soil Science 2017, 180 (6), 768-778.

- Goldie, H.S. Erratic judgements: re-evaluating solutional erosion rates of limestones using erratic-pedestal sites, including Norber, Yorkshire. Area 2005, 37 (4), 433-442.

- Peng, X.; Dai, Q.; Li, Ch.; Yuan, Y.; Zhao, L. Effect of simulated rainfall intensities and underground pore fissure degrees on soil nutrient loss from slope farmlands in Karst Region. Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering 2017, 33 (2), 131-140.

- Calvo-Cases, A.; Boix-Fayos, C.; Imeson, A.C. Runoff generation, sediment movement and soil water behaviour on calcareous (limestone) slopes of some Mediterranean environments in southeast Spain. Geomorphology 2003, 50 (1-3), 269-292.

- Bellanca, A.; Hauser, S.; Neri, R.; Palumbo, B. Mineralogy and geochemistry of Terra Rossa soils, western Sicily: insights into heavy metal fractionation and mobility. The Science of the Total Environment 1996; 193 (1), 57-67.

- Durn, G.; Ottner, F.; Slovenec, D. Mineralogical and geochemical indicators of the polygenetic nature of terra rossa in Istria, Croatia. Geoderma 1999, 91 (1-2), 125-150.

- Sanchez-Maraũón, M.; Soriano, M.; Delgado, G.; Delgado, R. Soil Quality in Mediterranean Mountain Environments: Effects of Land Use Change. Soil Science Society of America Journal 2002, 66 (3), 948-958.

- Strunk, H. Soil degradation and overland flow as causes of gully erosion on mountain pastures and in forests. Catena 2003, 50 (2-4), 185-199.

- Yaalon, D.H. Soils in the Mediterranean region: what makes them different? Catena 1997, 28 (3-4), 157-169.

- Singer, A.; Schwertmann, U.; Friedl, J. Iron oxide mineralogy of Terra Rosse and Rendzinas in relation to their moisture and temperature regimes. European Journal of Soil Science 1998, 49(3), 385-395. [CrossRef]

- Bronger, A.; Ensling, J.; Gűtlich, P.; Spiering, H. Rubification of Terrae Rossae in Slovakia: a Mossbauer effect study. Clays and Clay Miner 1983, 31 (4), 269-276.

- Kalicka, M.; Witkowska-Walczak, B.; Sławińska, C.; Dębicki, R. Impact of land use on water properties of rendzina. International Agrophysics 2008, 22 (4), 333-338.

- Voiculescu, M. The present-day erosional processes in the alpine level of the bucegi mountains - southern carpathians. Forum Geografic. 2009, 8 (8), 23-37.

- Maheľ, M. Geologicka stavba československých Karpat. Paleoalpinske jednotky. Veda SAV, Bratislava, Slovakia, 1986; p. 479.

- Harčár, J.; Kondračova, V.; Maltovič, R.; Michaeli, E. Prešov, Prešovský okres a Prešovský kraj. Geografickie exkurzie. University of Presov, Slovakia, 1998; p. 196.

- Nemčok, J. Vysvetlivky ku geologickej mape Pienin, Čergova, Ľubovnianskej a Ondavskej vrchoviny. GUDŠ, Bratislava, Slovakia, 1990; p. 35-44.

- Michaeli, E. Regionalna geografia Slovenskiej Republiky. University of Presov, Slovakia, 2008; p. 240.

- Tessier, A.; Campbell, P.G.; Bisson, M. Sequential extraction procedure for the speciation of particulate trace metals. Analytical Chemistry 1979, 51 (7), 844-851.

- Wischmeier, W.H.; Smith, D.D. Predicting rainfall erosion losses – a guide to conservation planning. U.S. Dep of Agriculture, Agriculture Handbook No. 537. 1978.

- Gąsior, J.; Jakobińczuk, W.F.; Oliwa, B. Kształtowanie się właściwości gleb górskich Karpat pod trwałymi użytkami zielonymi. Zeszyty Naukowe AR Kraków 2003, 399(89), 71-79.

- Kowalkowski, A;, Borzyszkowski, J. Badania nad związkami między morfologią powierzchni ziemi a strukturą pokrywy glebowej. Roczniki Gleboznawcze 1997, 28 (3/4), 3-17.

- Birkeland, P.W.; Shroba, R.R.; Burns, S.F.; Price, A.B.; Tonkin, P.J. Integrating soils and geomorphology in mountains – an example from the Front Range of Colorado. Geomorphology 2003, 55 (1-4), 329-344.

- Partyka, A.; Gąsior, J.Struktura pokrywy glebowej na południowych stokach w najwyższej części Bieszczadów Zachodnich w miejscowości Brzegi Górne. Zeszyty Problemowe Postępów Nauk Rolniczych 2003, 493, 455-463.

- Van Loo, M..; Dusar, B.; Verstraeten, G.; Renssen, H.; Notebaert, B.; D'Haen, K.; Bakker, J. Human induced soil erosion and the implications on crop yield in a small mountainous Mediterranean catchment (SW-Turkey). Catena 2017, 149 (1), 491-504.

- Starkel, L.; Baungart-Kotarba, M.; Michna, E.; Gil, E.; Pohl, J.; Słupik, J.; Zawora, T. Studia nad typologią i oceną środowiska geograficznego Karpat i Kotliny Sandomierskiej. Prace Geograficzne IG PAN 1978, 125, p. 165.

- Klima, K.; Wiśniowska-Kielian, B. Ocena strat gleby w wyniku spływu powierzchniowego w rejonie wyżynnym zależnie od rodzaju użytku. Zeszyty Problemowe Postępów Nauk Rolniczych 2007, 520, 821-827.

- Bochenek, W.; Gil, E. Water circulation, soil erosion and chemical denudation in flysh catchment area. Przegląd Naukowy, Inżynieria i Kształtowanie Środowiska 2007, 2 (36), 28-42.

- Cerda, A. Parent material and vegetation affect soil erosion in eastern Spain. Soil Science Society of America journal 1999, 63 (2), 362-368. [CrossRef]

- Badía, D.; Orús, D.; Doz, J. R.; Casanova, J.; Poch, R.M.; García-González, M.T. Vertic features in a soil catena developed on Eocene marls in the Inner Depression of the Central Spanish Pyrenees. Catena 2015, 129, 86-94. [CrossRef]

- Mirabella, A.; Carnicelli, S. Iron oxide mineralogy in red and brown soils developed on calcareous rocks in central Italy. Geoderma 1992, 55 (1-2), 95-109.

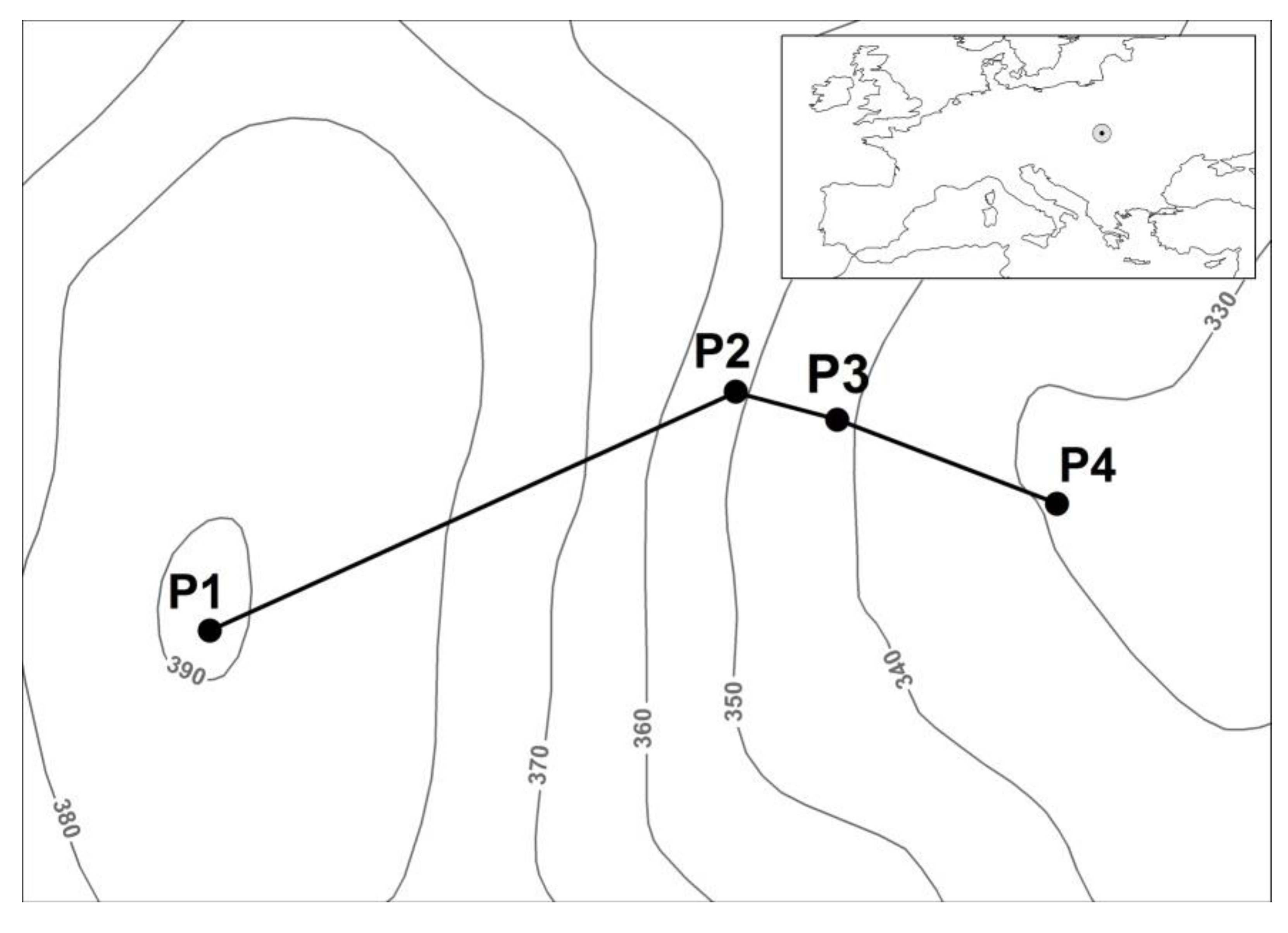

| Profile | Altitude (meters above sea level) | Latitude N | Longitude E |

|---|---|---|---|

| P-1 | 392 | 49°10491 | 21°29521 |

| P-2 | 347 | 49°10597 | 21°29886 |

| P-3 | 336 | 49°10582 | 21°29973 |

| P-4 | 325 | 49°10539 | 21°30121 |

| Fraction | Extractor |

|---|---|

| FeI ion-exchangeable | 1M MgCl2, pH 7,0 |

| FeII carbonate | 1M NaOAc, pH 8,2 |

| FeIII oxide | 0,04M NH2OHHCl |

| FeIV organic + sulfide | 1) 0,02 M HNO3 + 30% H2O2, pH 2,0 2) 30% H2O2, pH 2,0 3) 3,2 M NH4AcOH |

| FeV other | HF + HClO4 |

| Profile Localization |

Genetic horizon |

Depth (cm) |

Skeleton | Share of fraction | Color | CaCO3 (%) |

Co ( %) |

N g kg-1 |

C/N | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Φ > 2 mm (%) |

Sand | Dust | Silt | (dry) | ||||||||

| (%) | ||||||||||||

|

P-1 Hilltop |

Ap | 0–23 | 30 | 32 | 53 | 15 | 2,5 YR 3/3 | 4.2 | 1.41 | 1.76 | 8.01 | |

| A/Cca | 23–33 | 50 | 15 | 54 | 31 | 2.5 YR 4/4 | 23.6 | 0.73 | 1.01 | 7.23 | ||

| A/Cca2 | 33–48 | 30 | 14 | 56 | 30 | 2.5 YR 4/4 | 32.2 | 0.46 | 0.69 | 6.67 | ||

| Cca | 48–76 | 30 | 17 | 50 | 33 | 2.5 YR 4/5 | 32.4 | – | – | – | ||

| P-2 Slope |

Ap | 0–25 | 50 | 25 | 49 | 26 | 2.5 YR 5/5 | 26.1 | 1.31 | 1.95 | 6.72 | |

| RcaCca | 25–48 | 80 | 28 | 43 | 29 | 2.5 YR 6/7 | 56.5 | 0.94 | 1.27 | 7.39 | ||

| P-3 Slope |

Ap | 0–30 | 15 | 16 | 51 | 33 | 2.5 YR 5/5 | 28.7 | 1.22 | 1.82 | 6.70 | |

| A/C | 30–55 | 10 | 15 | 52 | 33 | 2.5 YR 5/6 | 40.0 | 0.59 | 0.88 | 6.70 | ||

| Cca2 | 55–87 | 15 | 8 | 54 | 38 | 2.5 YR 6/7 | 48.2 | – | – | – | ||

| Cca3 | 87–100 | 30 | 13 | 54 | 33 | 2.5 YR 6/7 | 53.2 | – | – | – | ||

| P-4 Bottom |

Ap | 0–25 | 5 | 15 | 56 | 29 | 2.5 YR 3/3 | 2.3 | 1.11 | 1.63 | 6.81 | |

| Bw | 25–59 | – | 13 | 60 | 27 | 2.5 YR 3/3 | 1.0 | 0.84 | 1.21 | 6.94 | ||

| Bw/C | 59–80 | – | 12 | 59 | 29 | 2.5 YR 5/6 | 1.2 | 0.61 | 0.92 | 6.63 | ||

| Bw/C2 | 80–105 | – | 13 | 64 | 23 | 2.5 YR 5/6 | 3.8 | 0.55 | 0.84 | 6.55 | ||

| CG | 105–115 | – | 23 | 53 | 24 | 2.5 YR 4/3 | 13.3 | – | – | – | ||

| Genetic horizon |

pH | Hh | S | T | V | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2O | 1MKCl | cmol(+) kg-1 | (%) | ||||

| P-1 | Ap | 7.82 | 7.15 | 0.15 | 9.30 | 9.45 | 98.4 |

| A/Cca | 8.14 | 7.32 | 0.15 | 9.00 | 9.15 | 98.3 | |

| A/Cca2 | 8.29 | 7.44 | - | 9.81 | 9.81 | 100.0 | |

| Cca | 8.59 | 7.50 | - | 9.24 | 9.24 | 100.0 | |

| P-2 | Ap | 7.84 | 7.26 | 0.15 | 10.28 | 10.43 | 98.6 |

| RcaCca | 8.50 | 7.68 | - | 8.84 | 8.84 | 100.0 | |

| P-3 | Ap | 8.09 | 7.27 | 0.45 | 10.37 | 10.82 | 95.8 |

| A/C | 8.33 | 7.39 | 0.30 | 9.71 | 10.01 | 97.0 | |

| Cca2 | 8.61 | 7.57 | - | 8.97 | 8.97 | 100.0 | |

| Cca3 | 8.76 | 7.61 | - | 8.97 | 8.97 | 100.0 | |

| P-4 | Ap | 8.26 | 7.21 | 0.15 | 8.13 | 8.28 | 98.2 |

| Bw | 8.32 | 7.03 | 0.45 | 8.68 | 7.13 | 93.7 | |

| Bw/C | 8.29 | 7.20 | 0.30 | 9.68 | 9.98 | 96.9 | |

| Bw/C2 | 8.41 | 7.25 | - | 9.31 | 9.31 | 100.0 | |

| CG | 8.51 | 7.48 | - | 9.61 | 9.61 | 100.0 | |

| Profile |

Horizon | Humidity (% m) |

Hygroscopic water (%) |

Density g cm-3 |

Specific density g cm-3 | Total porosity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-1 | Ap | 13.2 | 3.77 | 1.35 | 2.51 | 46.2 |

| A/Cca | 14.7 | 3.04 | 1.41 | 2.44 | 42.2 | |

| A/Cca2 | 14.4 | 2.60 | 1.48 | 2.47 | 40.1 | |

| Cca | 16.4 | 2.37 | 1.50 | 2.45 | 38.8 | |

| P-2 | Ap | – | – | – | – | – |

| RcaCca | – | – | – | – | – | |

| P-3 | Ap | 11.4 | 4.41 | 1.31 | 2.45 | 46.5 |

| A/C | 12.6 | 3.22 | 1.43 | 2.43 | 41.1 | |

| Cca2 | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Cca3 | 13.5 | 3.54 | 1.50 | 2.49 | 39.8 | |

| P-4 | Ap | 19.7 | 5.31 | 1.27 | 2.43 | 47.7 |

| Bw | 22.4 | 4.55 | 1.34 | 2.40 | 44.2 | |

| Bw/C | 23.1 | 4.48 | 1.38 | 2.47 | 44.1 | |

| Bw/C2 | 26.8 | 4.83 | 1.58 | 2.52 | 37.3 | |

| C/G | – | – | – | – | – |

| Profile |

Horizon | Fet (%) |

Fraction | Ratios | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FeI | FeII | FeIII | FeIV | FeV | FeIII/Fet | FeIV/Fet | |||

| mg kg-1 | g kg-1 | (%) | (%) | ||||||

| P-1 | Ap A/Cca A/Cca2 Cca |

3.79 | 0.05 | 1.95 | 1.32 | 0.26 | 37.5 | 3.48 | 0.69 |

| 3.71 | 0.07 | 1.24 | 1.36 | 0.07 | 34.6 | 3.66 | 0.19 | ||

| 4.23 | 0.06 | 1.94 | 1.15 | 0.05 | 43.8 | 2.72 | 0.12 | ||

| 4.50 | 0.06 | 2.93 | 1.18 | 0.05 | 46.1 | 2.62 | 0.11 | ||

| P-2 | Ap RcaCca |

3.93 | 0.08 | 0.15 | 0.84 | 0.06 | 40.1 | 2.14 | 0.15 |

| 3.98 | 0.08 | 0.16 | 0.46 | 0.01 | 38.6 | 1.16 | 0.02 | ||

| P-3 | Ap A/C Cca2 Cca3 |

3.86 | 0.08 | 0.15 | 0.89 | 0.11 | 38.2 | 2.30 | 0.28 |

| 3.64 | 0.06 | 0.31 | 0.71 | 0.05 | 34.1 | 1.95 | 0.14 | ||

| 4.07 | 0.07 | 0.39 | 0.51 | 0.02 | 41.3 | 1.25 | 0.05 | ||

| 4.46 | 0.07 | 0.80 | 0.79 | 0.02 | 45.3 | 1.77 | 0.04 | ||

| P-4 | Ap Bw Bw/C Bw/C2 CG |

3.13 | 0.05 | 1.30 | 1.60 | 0.42 | 28.3 | 5.11 | 1.34 |

| 3.28 | 0.08 | 0.72 | 1.65 | 0.23 | 30.1 | 5.03 | 0.70 | ||

| 1.82 | 0.06 | 0.69 | 1.58 | 0.21 | 16.2 | 8.68 | 1.15 | ||

| 1.88 | 0.08 | 0.94 | 1.06 | 0.16 | 17.3 | 5.64 | 0.85 | ||

| 1.94 | 0.07 | 0.31 | 0.87 | 0.05 | 17.8 | 4.48 | 0.26 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).