1. Introduction

Histoplasmosis is a disease caused by the fungus

Histoplasma capsulatum [

1] which is a primary pathogen found in soil rich in organic material. Although this fungus has a cosmopolitan distribution, there are areas of high endemicity such as the Americas and Africa as well as other regions with medium-to high endemicity including China [

2] and Southeast Asia [

3]. Despite the various presentations of the disease, disseminated histoplasmosis is the most frequent clinical presentation. Nowadays, disseminated histoplasmosis is the most common AIDS-defining disease and the leading cause of death in HIV-positive patients, with around 1,500 cases per year, in some areas [

4]. Histoplasmosis is also the imported mycoses most frequently reported outside these endemic regions [

5,

6]. Recently, based on its public health importance, global disease burden and existing knowledge gaps,

H.capsulatum. is ranked as a high priority pathogen in the WHO fungal priority pathogens list [

7].

Diagnosis of histoplasmosis is challenging in both endemic and non-endemic regions. In endemic regions, the scarcity of tools for fast and accurate identification of the infection is a significant problem. In these regions the disease is mainly associated with patients living with AIDS who develop the disseminated form of the disease, which can be fatal in the absence of rapid and appropriate treatment [

8]. In non-endemic areas in addition to the lack of diagnostic methods a low index of suspicion must be added [

9]. The gold standard for diagnosis of histoplasmosis is based on conventional laboratory assays using culture and histopathology. However, these assays have several limitations, including the need for high-level laboratory infrastructure for culture handling (biosecurity level 3), the need for highly trained laboratory personnel, variable assay analytical performance, and a long turn-around time for results. Alternative diagnostic methods are essential to achieve a rapid diagnosis as this has a significant impact on the patient’s outcome [

10,

11,

12].

In recent years, a great effort has been made to develop methods based on the detection of different biomarkers. Serum is a non-invasive sample, easily obtainable, even in primary care centers, that can be used to detect antigens, antibodies, nucleic acids, and biomolecules to determine the evolution of an infection, making it a valuable sample.

The detection of antigens represented an important breakthrough in the early diagnosis of histoplasmosis, however, these tests have not been widely available in many regions until recently. Specifically, the

Histoplasma GM ELISA (IMMY) test has demonstrated excellent performance and reproducibility in disseminated disease, but it has only been tested in urine samples until now [

13]. Techniques based on the detection of antibodies, such as immunodiffusion or complement fixation are commercially available and useful mainly for travelers from endemic regions, however their sensitivity is moderate in immunosuppressed patients [

14]. Techniques based on the detection of nucleic acids have shown to be very promising tools for rapid diagnosis but, there is a lack of commercial tests and consensus among laboratories [

15].

In addition, much of our understanding of cytokine responses as biomarkers for diagnosis is derived from studies on different fungal infections, but data for histoplasmosis is very limited. Previous works performed on bronchoalveolar lavage samples showed the differential role of certain cytokines in the local inflammatory processes of infection with

H. capsulatum,

P. jirovecii, or both [

16] and the possibility to monitor certain cytokines levels for prognosis evaluation in patients [

17].

In this study, the diagnostic accuracy of different techniques using serum as a non-invasive sample was retrospectively evaluated in 41 samples from 40 patients with proven and probable histoplasmosis. Techniques based on the detection of antibodies, antigens, and DNA were tested, and a comparative analysis was performed. In addition, we analyzed the immunological response of patients using a panel of cytokines and other immunological biomarkers aiming to complement the diagnosis and predict their prognosis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients and Clinical Samples

This study was performed retrospectively using serum samples from the collection of clinical specimens of the Mycology Reference Laboratory included in the ISCIII Biobank Collection. The samples were previously anonymized in compliance with Spanish law and the ISCIII ethics committee approved the project.

A total of forty-one serum samples from 40 patients with proven (30) and probable (10) histoplasmosis, based on criteria from EORTC/MSG, were analyzed [

18]. Most patients 80% (32/40) were immigrants from Latin-American and African countries, and the rest were travelers to endemic areas. Regarding underlying diseases, 20 patients had AIDS, fifteen of whom presented with a disseminated histoplasmosis (DH), 3 with acute pulmonary histoplasmosis (APH) and 2 with a gastrointestinal form (GIH). Nineteen were immunocompetent patients with different forms of the disease, 9 with APH or Sub acute pulmonary histoplasmosis (SAPH), 1 patient with mediastinitis, 1 with pyomyositis, 1 with chronic respiratory condition, 3 with rheumatoid arthritis, 1 patient with primary skin infection and 3 non-HIV patients with no clinical information collected. Only one patient had other type of immunosuppression different from AIDS and presented with a disseminated disease (

Table 1).

Due to limitations in the available volume sample, not all tests were carried out in every sample. The specific number of samples used for each test is described for each diagnostic methodology. Among those, we were able to test all the diagnostic methodologies in 27 samples.

For the biomarker-cytokine study, additional samples from patients with probable infection were included in order to increase the number of patients and samples. For that purpose, we used 36 samples of which 11 were additional samples and different from the samples initially used in the diagnostics studies. We also included eight serum samples from immunocompromised patients with no fungal infection according to the EORTC criteria 18.

2.2. Antigen Detection

Detection of Histoplasma GM (EIA Test Kit)

The clarus Histoplasma GM EIA test kit (IMMY Palex, Madrid, Spain) is validated and approved by FDA for urine samples [

13,

19]. The serum needs to be pretreated to release diagnostically relevant antigens. These samples were pretreated according to the manufacturer's recommendation as follows: a volume of 100 microliters of buffer supplied by the manufacturer was added to 300 microliters of each serum sample. The mixture was incubated at 120 °C for 6 minutes. Centrifugation was performed at 10,000 rpm for 10 minutes. The supernatant was used to carry out the indicated immunoassay technique. A cutoff of ≥0.20 ng/ml was used to determine positivity, according to the manufacturer´s recommendations.

To test cross-reactivity with other closely related fungal species, a total of 25 serum from patients infected with species of Aspergillus spp. (8), Candida spp. (5) and other endemic species such as Paracoccidiodes spp. (7) and Coccidiodes spp. (5) were included as control.

Detection of Histoplasma capsulatum by PlateliaTM Aspergillus Ag (Bio-Rad)

A volume of 300 microliters of serum was used. The assay was performed following the manufacturer´s recommendations. A cutoff of ≥ 0.5 was used to determine positivity.

2.3. Antibody Detection

Detection of Histoplasma antibodies by immunodiffusion by using the "ID Fungal Antibody System" kit (IMMY, Palex, Madrid, Spain) was used following the manufacturer´s instructions. A volume of 20 µl was tested for the assay. Results were analyzed after 48 hours.

2.4. DNA Detection

DNA extraction was performed using the QiAmp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Werfen, Madrid, Spain) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Fifty microliters of elution buffer were used for elution.

The RT-PCR technique described by Gago et al., [

20] was employed for the detection of the ITS2 region of the ribosomal DNA of

H. capsulatum. Four microliters of DNA from the clinical samples were used as template. All tests were performed in duplicate, including negative and positive controls for the PCR.

2.5. Biomarkers Quantification

A cytokine panel including IL-1β, IL-8, IL-17, IL-23, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-10, IL-18, and the soluble proteins: PTX3 and sTREM1 were tested in serum samples using Luminex with the Bio-Plex equipment (Bio-Rad). For sample preparation, the commercial Human premixed Multi-Analyte kit (R&D Systems) was used, following the protocol recommended by the manufacturer. All cytokine determinations were performed in duplicates, and concentrations were reported in pg/mL.

2.6. Statistical Analyses

All data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism software. To determine significant differences between the study groups, unpaired t-test were performed using the Mann-Whitney test. P values <0.05 were considered statically significant.

The correlation between biomarkers among H. capsulatum infected patients was explored using the Spearman correlation test.

3. Results

3.1. Antigen Detection

The GM EIA test was performed on 33 samples.The sensitivity of GM EIA test kit in immunosuppresed patients (IS), mostly with AIDS, was 94% (17/18) and in immunocompetent patients (IC) was 66% (10/15). Patients with disseminated disease were positive in a 100% (13/13). With acute pulmonary histoplasmosis (APH) were detected in a 75% (9/12), gastrointestinal histoplasmosis (GIH) 50% (1/2).

The PlateliaTM Aspergillus Ag was performed on 37 samples, but demostrated low performance in both groups: 42% (8/19) in IS and 16% (3/18) in IC.Best results were obtained in patients with DH 53% (8/15) vs. patients with APH (1/12) and was negative for chronic and mild disease.

3.2. Antibody Detection

The detection of antibodies using the ID fungal antibody System was performed in 40 samples and was positive in 31 out of 40 (77,5%). 95% (18/19) of ICs and 62% of IS(13/21). Patients with disseminated disease were positive in a 56,25% (9/16), APH 85% (11/13), GIH 66% (2/3); mild symptoms 100% (3/3).

3.3. DNA Detection

The PCR technique was performed in 36 samples and results were moderated for the detection of DNA. The overall sensitivity was 36% (13/36) being more useful for IS patients 50% in HIV (10/20) vs 19% in non-HIV(3/16). Patients with disseminated infections gave the best results 62.5% (10/16).

3.4. Comparative Analysis of Tools Used for Diagnostic

All methods were performed in 27 samples from 26 patients. Individual results are presented in the

Table 2 and aggregated results are summaried in

Table 3.

We explored the potential of using combinations of techniques to improve diagnostic performance (

Table 4).

3.5. Biomarkers Quantification

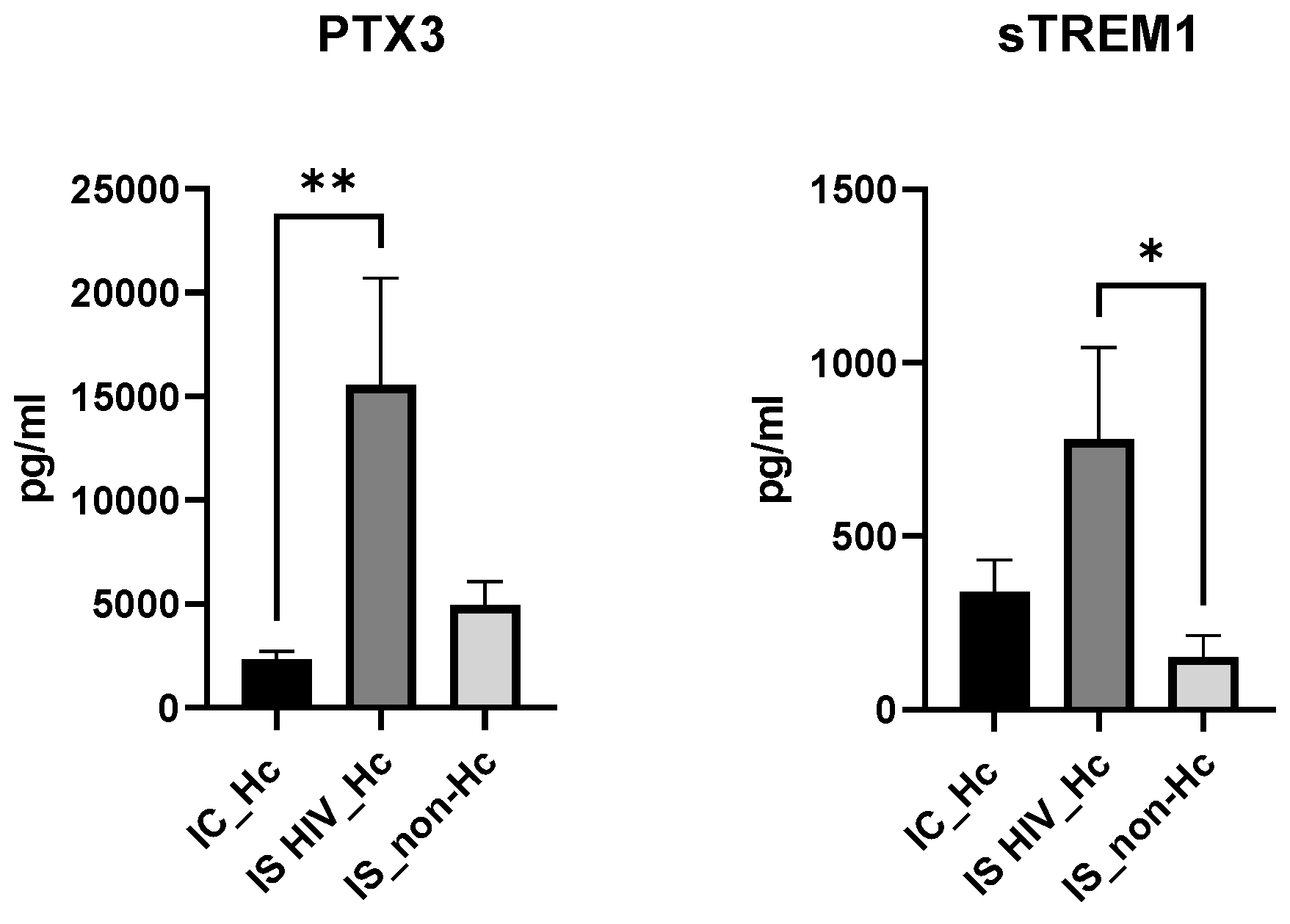

Since immune response is expected to be different between immunossupressed (IS) or immuno-competent (IC) individuals, patients were grouped in three categories: IC_Hc (Immuno-competent with H. capsulatum infection), IS HIV_Hc (Immunossupressed with HIV and H. capsulatum infection) and IS_non-Hc (Immunossupressed with non H. capsulatum infection).

Overall, patient groups infected with H. capsulatum (IC-Hc and IS HIV-Hc groups) showed higher IL-8, IL-6, IL-1B, TNF-α, IL-18 median values compared to not Hc infected controls, although no significance was reached for some of the analyses. The IS HIV-Hc group showed the highest median values with statistical differences for IL-6, IL-1Β, TNF-α, IL-18 (

Figure 1).

IL-17A, and IL-23 were analysed, with no significant difference values among groups.

The anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10, results showed also higher values for the Hc infected groups and statistical differences were found for both groups when compered to the IS_non-Hc patients.

Regarding the soluble biomarkers PTX3 and sTREM1 (

Figure 2), a significantly higher median value for PTX3 was found when IS HIV_Hc and IC_Hc groups were compared. Compared to the IS_non-Hc group PTX3 values were also higher, although no significance was reached. sTREM1 showed significantly higher median values of IS HIV_Hc patients againts IS_non-Hc individuals.

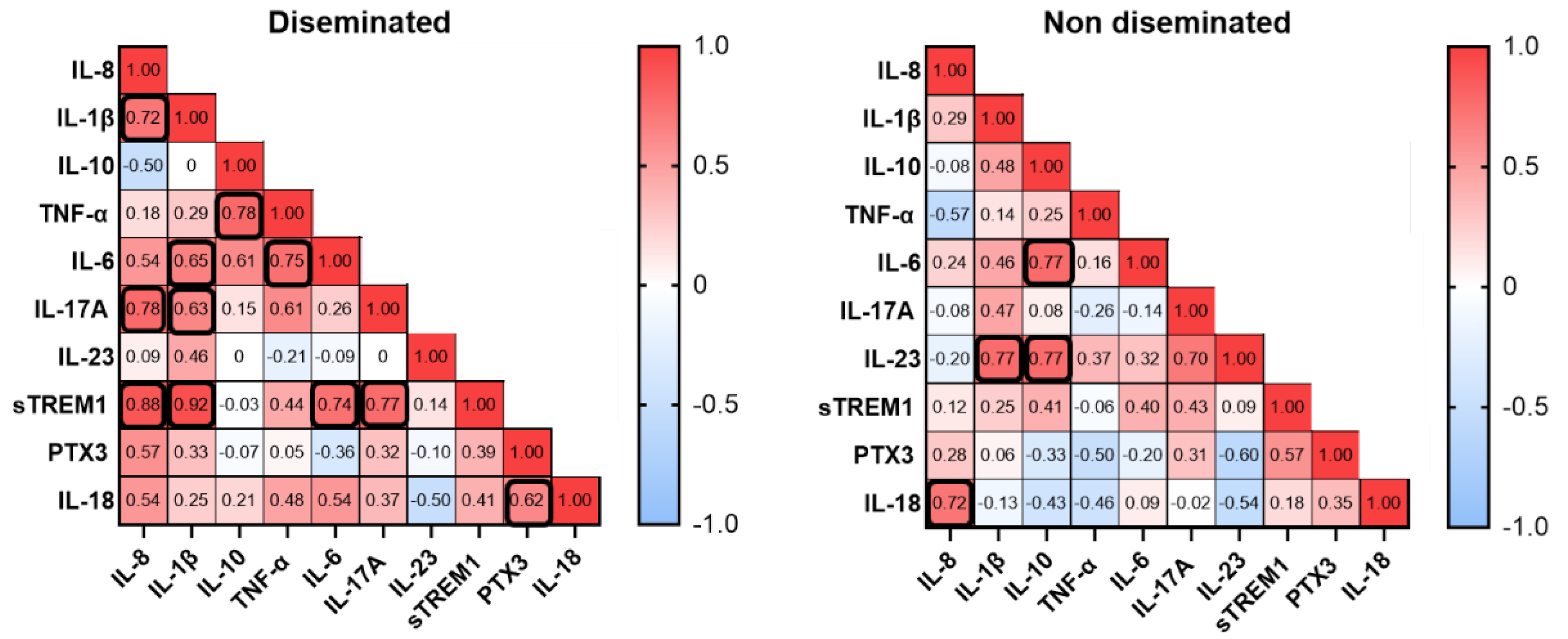

To further investigate biomarkers and disease conditions, we performed a correlation analysis of serum biomarkers among patients that developed a disseminated histoplasmosis and patients with a non-disseminated form of the disease. Disseminated patients demonstrated positive correlations between certain biomarkers. The strongest correlations were observed where IL-8 correlated well with IL-1β, IL-17A and sTREM1, and the strongest correlation was found between IL-1β and sTREM1. In the group of the non-disseminated form of the disease, we found positive correlation for IL-8 and IL-18, and IL-23 with IL-1β and IL-10, which showed correlation with IL-6.

Figure 3.

Correlation analysis of serum biomarkers. The scale represents the Spearman rho value; red squares correspond to the maximum positive correlation and blue squares to the maximum negative correlation. Numbers represent the correlation values and black bold squares indicate statistical significance. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Figure 3.

Correlation analysis of serum biomarkers. The scale represents the Spearman rho value; red squares correspond to the maximum positive correlation and blue squares to the maximum negative correlation. Numbers represent the correlation values and black bold squares indicate statistical significance. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Discussion

The diagnosis of histoplasmosis classically relies on culture, and microscopy. The isolation of the fungus on culture or the visualization of yeast in tissues from clinical samples are considered the gold standard, but these methods have well-known limitations. Recently, new methods based on the detection of antigens, antibodies, and DNA have been developed, leading to an improvement in diagnosis. However, the diagnosis of histoplasmosis remains challenging due mainly to the lack of the availability of some of these methods in certain areas, and due to the different clinical presentations, that make suspicion and detection difficult.

The simplest sample to obtain from patients in any setting is serum. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to analyze the effectiveness of different methods using serum for the diagnosis of histoplasmosis. Moreover, cytokine profiling in different groups of patients with histoplasmosis was performed to identify putative biomarkers of disease.

Samples from patients with proven and probable histoplasmosis were included, comprising two different groups. The first group consists on patients immunosuppressed, mostly with AIDS as an underlying condition, who typically present a disseminated or acute pulmonary disease. The second group comprises immunocompetent patients with, in many cases, much milder clinical presentations.

Regarding the methods employed, three commercial methods were used, an immunodifussion method for the detection of antibodies, a (EIA) specific for the detection Histoplasma galactomannan antigen and the Platelia galactomannan for

Aspergillus. The reason for using the later relies on the fact that

H. capsulatum and other endemic fungi cross-react with the Platelia test for

Aspergillus spp. and this test has indeed been helpful in those laboratories without access to

Histoplasma-specific tests [

21].

For the detection nucleic acids an “in house” technique previously described [

20] and validated was performed. All methods were only tested in 27 samples due to sample volume limitations. A comparative analysis was performed with these groups of samples.

As far as we know, this is the first study that used serum samples for the GM-EIA Kit as previously works used urine samples [

22]. The samples were pretreated as recommended by the manufacturer´s. Unfortunately, not all tests could be performed on all samples, which is a limitation of this work. However, we included in this work patients with different clinical characteristics, from disseminated infection to a much milder infection which allows assessing the performance of the techniques based on the clinic characteristics.

The best results were obtained in patients with immunosuppression (HIV+) and disseminated disease, being the most cost-effective in this population the galactomannan antigen detection technique (S 94%), followed by immunodiffusion. This technique has the limitation of not being used very widely in non-endemic regions since it is not cost-effective due to the low number of cases in these regions. In immunocompetent patients, the immunodiffusion technique detected the 100% of all sera showing its usefulness. However, this technique does not allow to discriminate between past or active infection. Moreover, the seroconversion requires 4 to 8 weeks to become antibodies detectable in serum.

The positive Platelia Aspergillus results were associated mainly with disseminated disease; however, the moderate sensitivity indicates that it is not a good option to rule out histoplamosis. In immunocompetent patients the sensitivity was very low indicating that it should not be used.

Regarding the RT-PCR results, the moderate sensitivity obtained suggested that the amount of circulating DNA in blood is very low. It would be necessary to develop alternative extraction methods that use large volumes of serum to improve the performance of the technique since PCR has the advantage of being fast, easy, specific and increasingly cheaper. Improved results were obtained by combining RT-PCR and ID. The combination of these two techniques is easy to implement in laboratories and can be especially useful in non-endemic regions since they can be easily performed for a low number of samples in the clinical laboratory.

The immune response to histoplasmosis has been mostly studied using animal or in vitro infection models [

23]. In the murine lung infected with

H. capsulatum, elevated concentrations of the cytokines IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-17, IL-23, IL-12, IFN-γ, IL-4, and IL-10 have been described [

24]. Additionally, in humans, increased concentrations of cytokines IL-1β and TNF-α, along with others such as IFN-γ, IL-18, IL-17A, IL-33, IL-13, and CXCL8, have been observed

16. In our work, compared to other groups, IS HIV_Hc patients showed the highest median values for IL-8, IL-6, IL-1B, TNF-α, IL-18 PTX3 and sTREM1 (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). TNF- α and IL-1β contribute to the generation of protective immunity against infection with

H. capsulatum [

25]. In our study TNF-α and IL-1β together with IL-6 and IL-18 showed the highest values with statistical differences for the group of HIV patients and Hc suggesting that these cytokines play a role in the local inflammatory processes of histoplasmosis in HIV patients. Our results also showed elevated levels of the soluble pattern recognition molecule pentraxin 3 (PTX3), and the soluble form of the triggering Receptor Expressed on Myeloid Cells 1 (sTREM1) in the IS HIV_Hc group. These two components of the immune response have shown a role against fungal disease with for example elevated levels in serum samples of haematological patients with invasive aspergillosis [

26]. The analysis for exploring associations between different biomarkers demonstrated a strong positive correlation between several cytokines in patients with disseminated histoplasmosis. This finding suggests that these cytokines play a role in the human immune response to

Histoplasma spp.

, with immune responses differing between immunocompetent and immunocompromised individuals.

It might appear difficult to use the information provided by host biomarkers such as cytokines to improve the diagnostic of fungal infections and even more in the context of Histoplasmosis and immunosupression associated to HIV. However, very little is investigated on that so increasing our knowledge about the role of soluble mediators that occur during these infections will provide information about host-pathogens interactions and how the host fights against the pathogen. This knowledge can be therefore used to improve diagnostic in a particular group of patients and to develop therapeutic strategies limiting the progressive invasive disease.

5. Conclusions

The performance of serum samples for rapid diagnosis of histoplasmosis depends on the patient's clinical presentation and the chosen diagnostic technique. The GM EIA kit appears to be a suitable choice for diagnosing disseminated histoplasmosis. The ID technique is valuable for detecting H. capsulatum antibodies in immunocompetent patients. The RT-PCR technique, however, exhibited moderate performance in serum and should be used in combination with other techniques. Elevated IL-1β, TNF- α, IL-18 and PTX3 levels in HIV patients with histoplasmosis could serve as a potential predictive biomarker for poor prognosis and disseminated disease development in these individuals. To assess the specificity and confirm the utility of these techniques in histoplasmosis diagnosis, further studies with larger patient cohorts, control subjects, and individuals with other infections are necessary.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, LBM, MJB, and LAF; methodology, RV, SG, PCR, SOM.; validation, LBM, MJB and LAF; formal analysis, LBM, MJB and LAF.; investigation, LBM, MJB and LAF; resources, LBM, MJB and LAF; data curation, LBM, MJB and LAF; writing—original draft preparation, LBM, MJB and LAF; writing—review and editing, LBM, MJB and LAF; funding acquisition, LBM and LAF. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

LAF and MJB were supported by ISCII (AESI) (MPY 117/18 and MPY 305/20). MJB and LBM were also granted by ISCIII (AESI)(MPY 433/2021. This work was also funded by the National Centre for Microbiology (Instituto de Salud Carlos III) through the Surveillance program of Antifungal Resistance and the Center for Biomedical Research in Network in Infectious Diseases (CIBERINFECT CB21/13/00105 (LAF, MJB and LBM). S.G. was supported by a PhD studentship from the Fondo de Investigaciones Biomedicas of the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (FI10/00464).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was performed retrospectively using serum samples from the collection of clinical specimens of the Mycology Reference Laboratory included in the ISCIII Biobank Collection. The samples were previously anonymized in compliance with Spanish law and the ISCIII ethics committee approved the project (CEI PI 38_2019).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed at the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge IMMY as they provided us with the Histoplasma GM-EIA kit and with advice regarding the use of the kit in sera samples.

Conflicts of Interest

IMMY provided us with the Histoplasma GM-EIA kit.

References

- Deepe, G.S. Immune response to early and late Histoplasma capsulatum infections. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2000, 3, 359–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antinori, S. Histoplasma capsulatum: More Widespread than Previously Thought. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2014, 90, 982–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashraf, N.; Kubat, R.C.; Poplin, V.; Adenis, A.A.; Denning, D.W.; Wright, L.; McCotter, O.; Schwartz, I.S.; Jackson, B.R.; Chiller, T.; et al. Re-drawing the Maps for Endemic Mycoses. Mycopathologia 2020, 185, 843–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adenis, A.A.; Aznar, C.; Couppié, P. Histoplasmosis in HIV-Infected Patients: A Review of New Developments and Remaining Gaps. Curr. Trop. Med. Rep. 2014, 1, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buitrago, M.J.; Bernal-Martínez, L.; Castelli, M.V.; Rodríguez-Tudela, J.L.; Cuenca-Estrella, M. Histoplasmosis and Paracoccidioidomycosis in a Non-Endemic Area: A Review of Cases and Diagnosis. J. Travel Med. 2010, 18, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Morant, D.; Sánchez-Montalvá, A.; Salvador, F.; Sao-Avilés, A.; Molina, I. Imported endemic mycoses in Spain: Evolution of hospitalized cases, clinical characteristics and correlation with migratory movements, 1997-2014. PLOS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2018, 12, e0006245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, A.; Kim, H.Y.; Halliday, C.L.; Oladele, R.; Rickerts, V.; Mmed, N.P.G.; Shin, J.-H.; Heim, J.; Ford, N.P.; Nahrgang, S.A.; et al. Histoplasmosis: A systematic review to inform the World Health Organization of a fungal priority pathogens list. Med Mycol. 2024, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nacher, M. Histoplasmosis in Persons Living with HIV. J. Fungi 2019, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buitrago, M.J.; Martín-Gómez, M.T. Timely Diagnosis of Histoplasmosis in Non-endemic Countries: A Laboratory Challenge. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedict, K.; Beer, K.D.; Jackson, B.R. Histoplasmosis-related Healthcare Use, Diagnosis, and Treatment in a Commercially Insured Population, United States. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2019, 70, 1003–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, N.; Alastruey-Izquierdo, A.; Bonilla, O.; Gamboa, O.; Mercado, D.; Pérez, J.C.; Salazar, L.R.; Arathoon, E.; Denning, D.W.; Rodriguez-Tudela, J.L. A Rapid Screening Program for Histoplasmosis, Tuberculosis, and Cryptococcosis Reduces Mortality in HIV Patients from Guatemala. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samayoa, B.; Aguirre, L.; Bonilla, O.; Medina, N.; Lau-Bonilla, D.; Mercado, D.; Moller, A.; Perez, J.C.; Alastruey-Izquierdo, A.; Arathoon, E.; et al. The Diagnostic Laboratory Hub: A New Health Care System Reveals the Incidence and Mortality of Tuberculosis, Histoplasmosis, and Cryptococcosis of PWH in Guatemala. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2019, 7, ofz534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cáceres, D.H.; Samayoa, B.E.; Medina, N.G.; Tobón, A.M.; Guzmán, B.J.; Mercado, D.; Restrepo, A.; Chiller, T.; Arathoon, E.E.; Gómez, B.L. Multicenter Validation of Commercial Antigenuria Reagents To Diagnose Progressive Disseminated Histoplasmosis in People Living with HIV/AIDS in Two Latin American Countries. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2018, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caceres, D.H.; Knuth, M.; Derado, G.; Lindsley, M.D. Diagnosis of Progressive Disseminated Histoplasmosis in Advanced HIV: A Meta-Analysis of Assay Analytical Performance. J. Fungi 2019, 5, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valero, C.; Martín-Gómez, M.T.; Buitrago, M.J. Molecular Diagnosis of Endemic Mycoses. J. Fungi 2022, 9, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreto-Binaghi, L.E.; Tenorio, E.P.; Morales-Villarreal, F.R.; Aliouat, E.M.; Zenteno, E.; Martínez-Orozco, J.-A.; Taylor, M.-L. Detection of Cytokines and Collectins in Bronchoalveolar Fluid Samples of Patients Infected with Histoplasma capsulatum and Pneumocystis jirovecii. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.-Y.; Guo, S.-L.; Yan, X.-F.; Zhang, L.-L.; Wang, J.; Yuan, G.-D.; Qing, G.; Xu, L.-L.; Zhan, Q. Collective outbreak of severe acute histoplasmosis in immunocompetent Chinese in South America: the clinical characteristics and continuous monitoring of serum cytokines/chemokines. BMC Prim. Care 2022, 23, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, J.P.; Chen, S.C.; Kauffman, C.A.; Steinbach, W.J.; Baddley, J.W.; Verweij, P.E.; Clancy, C.J.; Wingard, J.R.; Lockhart, S.R.; Groll, A.H.; et al. Revision and Update of the Consensus Definitions of Invasive Fungal Disease From the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer and the Mycoses Study Group Education and Research Consortium. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 1367–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falci, D.R.; Monteiro, A.A.; Braz Caurio, C.F.; Magalhães, T.C.O.; Xavier, M.O.; Basso, R.P.; Melo, M.; Schwarzbold, A.V.; Ferreira, P.R.A.; Vidal, J.E.; et al. Histoplasmosis, An Underdiagnosed Disease Affecting People Living With HIV/AIDS in Brazil: Results of a Multicenter Prospective Cohort Study Using Both Classical Mycology Tests and Histoplasma Urine Antigen Detection. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2019, 6, ofz073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gago, S.; Esteban, C.; Valero, C.; Zaragoza, Ó.; de la Bellacasa, J.P.; Buitrago, M.J. A Multiplex Real-Time PCR Assay for Identification of Pneumocystis jirovecii, Histoplasma capsulatum, and Cryptococcus neoformans/Cryptococcus gattii in Samples from AIDS Patients with Opportunistic Pneumonia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014, 52, 1168–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranque, S.; Pelletier, R.; Michel-Nguyen, A.; Dromer, F. Platelia Aspergillus assay for diagnosis of disseminated histoplasmosis. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2007, 26, 941–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cáceres, D.H.; Gómez, B.L.; Tobón, Á.M.; Chiller, T.M.; Lindsley, M.D. Evaluation of OIDx Histoplasma Urinary Antigen EIA. Mycopathologia 2021, 187, 129–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horwath, M.C.; Fecher, R.A.; Deepe, G.S., Jr. Histoplasma capsulatum, lung infection and immunity. Future Microbiol. 2015, 10, 967–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahaza, J.H.; Suárez-Alvarez, R.; Estrada-Bárcenas, D.A.; Pérez-Torres, A.; Taylor, M.L. Profile of cytokines in the lungs of BALB/c mice after intra-nasal infection with Histoplasma capsulatum mycelial propagules. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2015, 41, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroetz, D.N.; Deepe, G.S., Jr. The role of cytokines and chemokines in Histoplasma capsulatum infection. Cytokine 2012, 58, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal-Martínez, L.; Gonçalves, S.; de Andres, B.; Cunha, C.; Jimenez, I.G.; Lagrou, K.; Mellado, E.; Gaspar, M.; Maertens, J.; Carvalho, A.; et al. TREM1 regulates antifungal immune responses in invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Virulence 2021, 12, 570–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).