1. Introduction

Students in STEM and health science disciplines often face cognitive load due to the volume and complexity of required content [

1,

2,

3]. This challenge, combined with decreasing interest in traditional educational approaches, contributes to disengagement and difficulty retaining knowledge [

4,

5,

6,

7]. As a result, there is growing interest in innovative teaching strategies that can both reduce cognitive load and increase motivation to learn—particularly among younger learners. Game-based learning (GBL) has emerged as a promising approach that promotes active learning, motivation, and knowledge retention through interactive and immersive experiences [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Serious games, specifically designed for educational purposes, have been increasingly adopted in health professions education for their ability to blend learning objectives with engaging gameplay [

12,

13].

Another well-established method for supporting learning in high cognitive load fields is the use of mnemonics [

14,

15]. Mnemonics leverage visual, linguistic, and spatial cues to aid in memory encoding and recall, making them useful for students managing large quantities of information common in STEM and health science fields [

16,

17,

18,

19]. While both GBL and mnemonics have been individually validated, few studies meaningfully combine the two into a unified educational experience.

To address this gap, we developed Medimon, an innovative GBL platform that merges mnemonic-based learning with the mechanics of a creature-collector role-playing game [

20]. In Medimon, players explore fictional environments, capture characters based on body systems, and engage in turn-based battles using moves and abilities grounded in medical mnemonics. The platform is designed to reduce cognitive load, enhance engagement, and improve knowledge retention through multisensory learning.

Our current project centers on the Medimon NASA Demo prototype, which focuses on two body systems of critical relevance to NASA and the future of space exploration: the musculoskeletal and visual systems. Astronauts operating in microgravity environments experience significant health challenges, including skeletal tissue degeneration, muscle atrophy, cardiovascular deconditioning, and Spaceflight-Associated Neuro-Ocular Syndrome (SANS) [

21,

22]. These issues are not only clinically important but also serve as compelling educational topics with real-world relevance that can capture student interest.

The Medimon NASA Demo was designed as a prototype serious game to teach undergraduate students about these systems through a self-regulated learning (SRL) environment [

23,

24]. We hypothesize that this demo will increase student knowledge of these body systems, foster engagement with health science education, and potentially boost interest in pursuing STEM-related careers.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Undergraduate students at the University of Idaho were recruited via email invitations and in-person presentations delivered by authors T.S. and T.B. The total number of participants (n=23) is represented in the participant flow diagram (

Figure 1), and demographic information is summarized in

Table 1.

2.2. Intervention

Participants were invited to download and play the Medimon NASA Demo, a serious game prototype integrating health science content related to the musculoskeletal and visual systems. They were instructed to engage with the game over a two-week period in an SRL manner, allowing them to control when and how often they played. The game is freely available at

https://panacea-interactive.itch.io/medimon-nasa-project

2.3. Design

The game prototype taught concepts from the musculoskeletal and visual systems using mnemonic-based characters and environments. Each character was part of a Medimon family representing a specific body system. Characters were designed across three evolutionary stages—Stage 1 (baby), Stage 2 (adolescent), and Stage 3 (adult)—with both healthy and diseased versions. Healthy Medimon represented normal anatomy and physiology, while diseased Medimon embodied related medical conditions. Diseased versions could be transformed into their healthy counterparts using in-game therapy items modeled after real-world treatments. Families and characters included in the prototype are listed in Appendix

Table A1.

Each character featured visual mnemonics reflecting their biological function or pathology (

Figure 2). For example, the Osteoclast character visually breaks down bone, symbolizing bone resorption. Locations within the game also supported mnemonic learning, such as the Bone family’s building, “Skeleton Crew Framing,” a hardware store where players accessed visual aids and encountered related wild Medimon (

Figure 3).

The turn-based battle system enabled players to battle and capture wild Medimon. Victories awarded experience points that allowed Medimon on the player's team to level up, enhance stats, and evolve. Key game statistics included:

HP (Health Points): Measures life; reaching zero causes the Medimon to “flat line,” meaning it can't be used in battle until healed.

ATP (Adenosine Triphosphate): Energy required to perform moves in battle, representing cellular energy.

STS (Stress): Increases with each move during battle; high STS may cause healthy Medimon to evolve into diseased versions or diseased Medimon to self-destruct.

Attack and Defense: Determine battle effectiveness and resistance to damage.

Moves within battles contained linguistic mnemonics (

Figure 4). For example, the Osteoclast’s “Bone Loss” move reinforces its biological role in bone resorption.

Players could also battle non-playable characters (NPCs) to level up their Medimon and visit a hospital to restore HP, ATP, and reduce STS. A comprehensive tutorial guided players through core mechanics, and the in-game menu provided explanations of educational content and mnemonics.

The game was built in the Unity game engine and uploaded for participant access on the itch.io platform.

2.4. Achievement

To evaluate learning, participants completed a short multiple-choice questionnaire before (pretest) and after (posttest) the two-week game period. Questions assessed knowledge of cellular functions, anatomical structures, and associated diseases covered in the game. Participants completed the pre/posttest through the Qualtrics platform.

2.5. STEM Career Interest

As part of the pretest and posttest, participants rated their interest in pursuing a STEM career using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Very interested; 5 = Very not interested). Changes in response were used to evaluate whether the game influenced career aspirations.

2.6. Data Collection

After completing the posttest, participants also completed the Situational Interest Survey of Multimedia (SIS-M), a validated instrument for evaluating multimedia engagement [

25,

26]. The SIS-M evaluates triggered interest, maintained interest, maintained feeling, and value interest using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly disagree; 5 = Strongly agree) (Appendix

Table B1), and has been used in prior medical education studies [

27,

28,

29]. The 12-item SIS-M was administered with two additional items: (1) a preference ranking between different health science learning modalities (Medimon game, traditional materials, or no preference), and (2) an open-ended explanation of that preference. Participants completed the SIS-M through the Qualtrics platform.

2.7. Data Analysis

Quantitative data analysis was conducted using Microsoft Excel and GraphPad Prism. Student achievement data were analyzed by calculating average pretest and posttest scores for each participant group. To further evaluate learning gains, normalized change calculations were applied, providing a standardized metric for interpreting improvement relative to baseline performance [

30].

For the Situational Interest Survey in Multimedia (SIS-M), responses were analyzed across four validated dimensions of situational interest: triggered interest, maintained interest, maintained-feeling, and maintained-value.

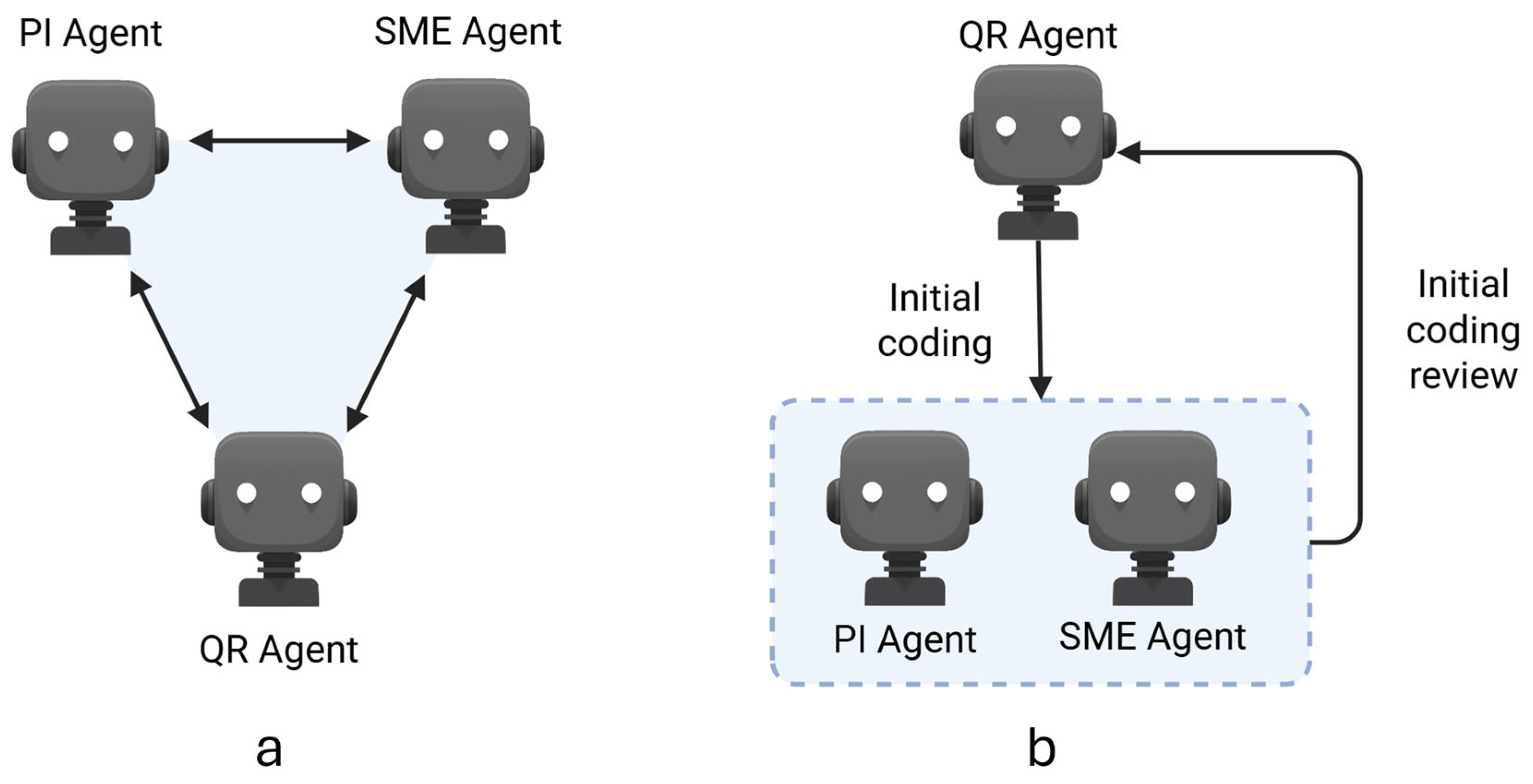

The open-ended SIS-M survey responses were analyzed using a large language model (LLM)-driven qualitative workflow informed by recent applications in medical education research [

27,

28,

29]. An agentic analysis process was utilized [

31,

32] which was powered by the “thinking” Google Gemini 2.5 Pro Experimental 03-25 LLM. The process involved three specialized generative artificial intelligent (genAI) agents, each guided by distinct system-level prompts tailored to their roles: Principal Investigator (PI), Qualitative Researcher (QR), and Subject Matter Expert (SME) (

Figure 5A). The workflow operated in a sequential, iterative format in which the output from one agent was refined by the next (

Figure 5B). Prompt engineering strategies, including Persona Prompting [

33,

34], were used to optimize agent performance. A detailed account of the full workflow—including all prompts, agent instructions, and resulting outputs—is provided in the

Supplemental Materials (Methods S1).

2.8. Ethical Considerations

The study protocol was reviewed and approved exempt by the Institutional Review Board (23-042) at the University of Idaho. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection.

3. Results

3.1. Achievement

All participants completed a multiple-choice questionnaire before and after engaging with the Medimon NASA Demo. Analysis revealed that posttest scores were significantly higher than pretest scores (pretest: 42% ± 13%; posttest: 65% ± 24%; p < 0.001), indicating a learning gain (

Figure 6A-B). To account for baseline knowledge variability and ceiling effects, we applied the normalized change method [

30]. The average normalized change across participants was c = 0.4 (

Figure 1C), representing a moderate improvement in knowledge acquisition during the two-week self-regulated learning period.

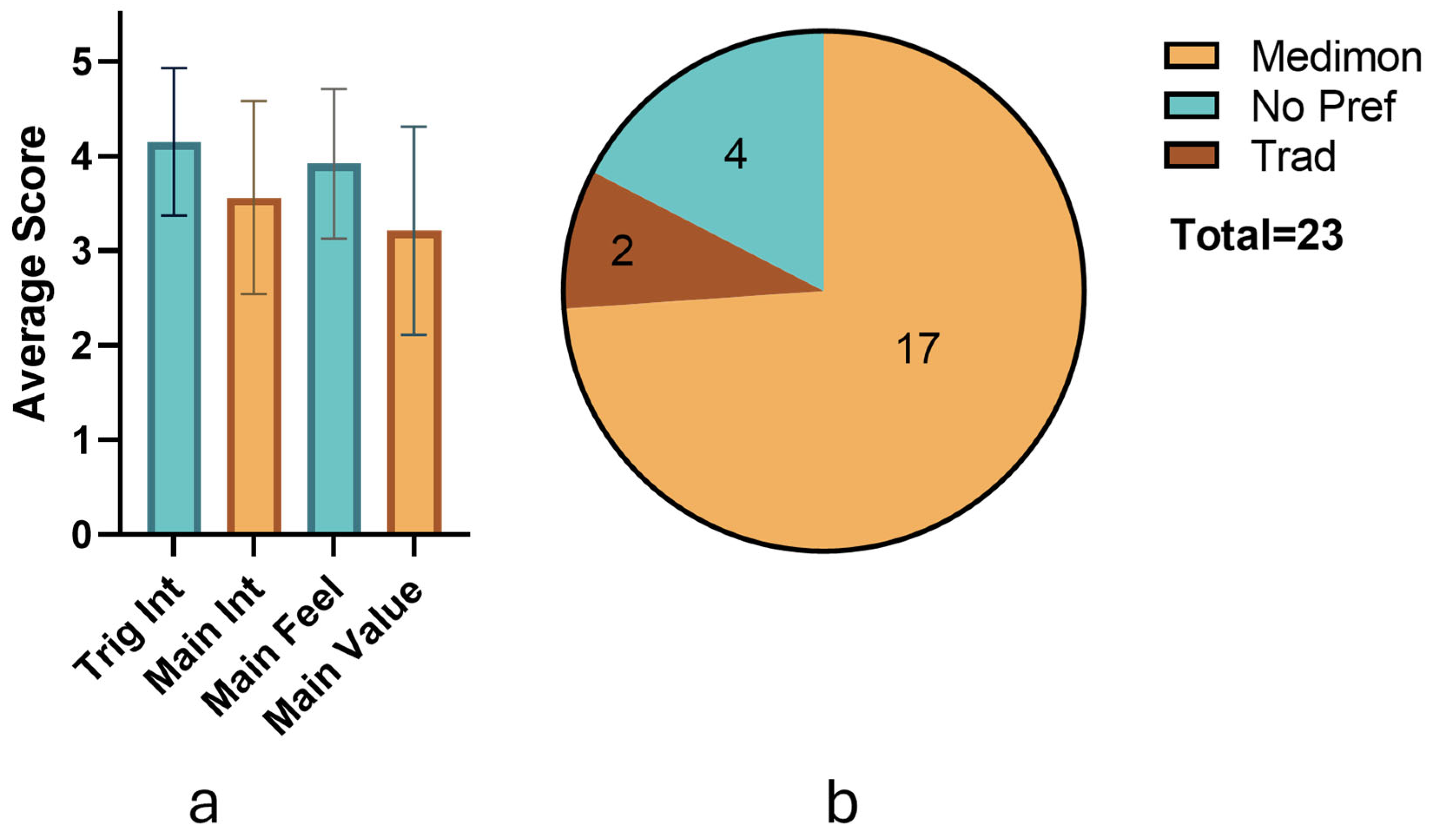

3.2. Engagement

The SIS-M provided insights into participants' levels of interest and engagement with the Medimon NASA Demo. The participants’ had a high average triggered situational interest (M = 4.15, SD = 0.78) and maintained feeling (M = 3.92, SD = 0.79) in the game (

Figure 7A).

The results for maintained interest (M = 3.56, SD = 1.02) and maintained value (M = 3.21, SD = 1.10) were more moderate, indicating a more neutral stance with the game. Overall, the majority of participants (74%) preferred the game for learning the health sciences, compared to the minority of participant who preferred traditional types of materials such as lectures and textbook readings (9%) and those who has no preference in learning material format (17%) (

Figure 7B).

To understand the underlying reasons for the learning modality preferences reported in the SIS-M, thematic analysis was conducted on participants' open-ended explanations. This analysis yielded four key themes illuminating the factors driving participants' choices: (1) Intrinsic Appeal & Affective Engagement, (2) Perceived Learning Efficacy & Mechanisms, (3) Interaction Design & Learner Experience, and (4) Cognitive Factors & Resource Management (

Table 2).

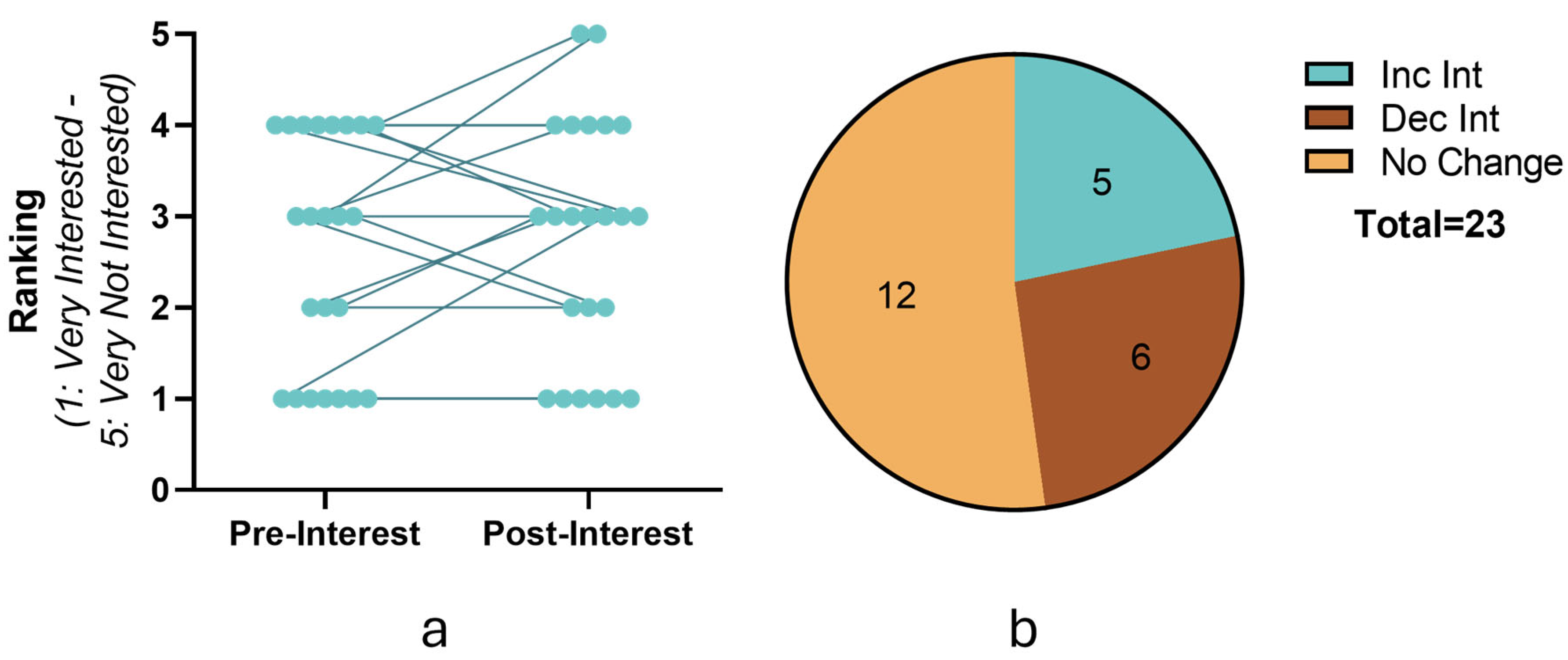

3.3. STEM Career Interest

To measure the game’s potential impact on career interests, participants rated their desire to pursue a STEM career before and after gameplay. Most participants showed no change in their career aspirations over the two-week period. However, five students reported increased interest in STEM, while five reported decreased interest (

Figure 8). These results suggest that while the demo had a positive educational impact, its effect on career intentions was limited during the short intervention window.

4. Discussion

The Medimon NASA Demo was designed to merge GBL with mnemonic strategies to address two persistent challenges in STEM and health science education: cognitive overload and student disengagement. Our findings suggest that this approach can improve student knowledge in key biomedical areas while maintaining high levels of learner engagement in an SRL environment.

Participants demonstrated significant learning gains, as evidenced by a 67% average improvement in posttest scores and a normalized change score of c = 0.4. These results are particularly notable given the brief, two-week exposure to the intervention and the lack of structured instructional support. The results affirm that the game's specific mechanisms, including its interactive nature and mnemonic-rich design (key elements highlighted in Theme 2: Perceived Learning Efficacy & Mechanisms), can serve as effective learning supports even without traditional scaffolding. These results suggest Medimon gameplay can serve as an effective standalone learning tool, especially when focused on content domains relevant to real-world challenges like those encountered in space medicine.

The SIS-M results further reinforce the educational potential of

Medimon. Participants reported high levels of triggered situational interest and maintained feeling. These findings align with previous studies in medical and STEM education that have shown serious games can foster motivation and sustained engagement. These quantitative findings align strongly with Theme 1 (Intrinsic Appeal & Affective Engagement) identified in the qualitative analysis, where participants emphasized the game's fun, engaging nature, and aesthetic appeal. Importantly, qualitative feedback highlighted that the integration of visual and linguistic mnemonics helped students grasp and retain difficult concepts, such as the function of osteoclasts in bone resorption or the etiology of conditions like retinitis pigmentosa and myasthenia gravis. This speaks directly to Theme 2 (Perceived Learning Efficacy & Mechanisms), as participants explicitly valued how mnemonics, interactivity, and the integration of content into gameplay made learning easier and more memorable. The presence of spatially located mnemonic-rich environments and NPCs provided contextual reinforcement, turning complex biological and pathological processes into accessible and memorable experiences [

35]. Participants reported more moderate levels of maintained interest and value-related interest. This outcome is consistent with the participant demographics, as the majority of students were not enrolled in STEM-related majors and, therefore, may not have perceived a health science educational game as highly relevant or essential to their academic studies.

Interestingly, while the game succeeded in improving knowledge and engagement, it had minimal impact on students’ STEM career aspirations. Only five participants reported increased interest in pursuing a STEM field, while five others reported a decline. This suggests that while GBL tools like Medimon can effectively enhance content understanding and immediate engagement, influencing long-term identity formation and career trajectories may require more prolonged, repeated exposure or the integration of mentorship and narrative career exploration within the game environment [

36,

37,

38,

39]. Career interest is often shaped by a broader range of psychosocial factors, including role modeling [

40,

41], perceived self-efficacy [

42,

43], and exposure to professional pathways [

44,

45]. Thus, future iterations of Medimon could include embedded role-play elements, career profiles, or narrative arcs that highlight the real-world applications of biomedical knowledge in various STEM professions, particularly in space medicine.

4.1. Limitations

Several limitations of the current study should be noted. First, the sample size was relatively small (n=23) and limited to students from a single institution, which may affect the generalizability of the results. One potential contributor to the high participant dropout rate may have been the complexity of the game access process. Participants were required to create an itch.io account, download the itch.io app, save the game to their account, and then install and play the game through the app. Future studies will explore more streamlined and user-friendly methods for distributing and accessing the game to reduce barriers to participation. Second, we did not track in-game behavior metrics such as time played, specific characters interacted with, or the frequency of battles completed. These metrics could provide a deeper understanding of how specific game mechanics influence learning and engagement. Third, the two-week duration may have been too short to observe meaningful changes in career interest. Fourth, the qualitative findings highlight specific design limitations perceived by some participants, particularly the lack of pedagogical structure, clear goals, and review mechanisms (Theme 3). These factors may have dampened learning outcomes or preference for students who thrive on more guided learning, suggesting the current prototype may be more appealing to intrinsically motivated or experienced gamers. Furthermore, concerns about learning depth and recall difficulty (Theme 2) identified by some participants suggest areas where the game's instructional design could be strengthened. Longitudinal studies are needed to assess how sustained interaction with GBL platforms like Medimon influences educational outcomes and career development over time.

Despite these limitations, this study provides compelling preliminary evidence that serious games integrating mnemonic strategies can enhance learning and engagement in undergraduate health science education. The thematic emphasis on musculoskeletal and visual systems within the context of space medicine also offers a novel interdisciplinary entry point for students who may not initially be drawn to STEM fields but are intrigued by the adventure and problem-solving aspects of space exploration. The self-paced nature of the demo aligns well with modern learner preferences [

46,

47] and demonstrates the value of autonomy and GBL feedback in promoting knowledge acquisition [

48].

4.2. Future Directions

Future research should expand the scope of Medimon to include additional body systems and pathologies, incorporate real-time data analytics, and assess its impact across diverse learner populations. Future iterations of Medimon should directly address the design feedback revealed through the qualitative analysis (Theme 3). This includes incorporating clearer learning objectives, progress tracking, feedback mechanisms, structured challenges or 'learning checks', and potentially dedicated review modes to enhance learner control and address recall concerns (Theme 2). There is also potential to explore collaborative modes of gameplay and integration into flipped or hybrid classroom models. As space agencies and healthcare systems prepare the next generation of scientists and clinicians, tools like Medimon offer a scalable, engaging, and pedagogically sound platform to inspire and educate tomorrow’s innovators. Finally, future work could explicitly embed career exploration elements or narratives to potentially influence STEM interest more effectively.

5. Conclusions

The Medimon NASA Demo represents a promising fusion of game-based learning and mnemonic strategies tailored to the unique needs of STEM and health science education. By embedding visually and linguistically rich mnemonics into an engaging, interactive gaming experience, the prototype succeeded in increasing student knowledge of the musculoskeletal and visual systems—two critical domains in space medicine. Participants not only demonstrated significant learning gains but also reported high levels of engagement and enjoyment in the game.

While the demo did not lead to a marked increase in STEM career interest over the short duration of the study, the strong indicators of cognitive and emotional engagement suggest that platforms like Medimon can serve as effective entry points into complex biomedical content. These results support the growing body of evidence that serious games, when thoughtfully designed, can bridge the gap between passive content delivery and active, meaningful learning.

Future work should focus on expanding content coverage, enhancing career exploration elements, integrating in-game analytics, and testing the platform across diverse learner populations and institutional contexts. With further development and longitudinal evaluation, Medimon has the potential to play a transformative role in health science education, helping cultivate a more scientifically literate and inspired generation of learners—both on Earth and beyond.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Methods S1: Agentic workflow, prompts, and outputs of the thematic analysis

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.H. and T.B.; data curation, T.B.; formal analysis, T.B.; investigation, M.H. and T.B.; methodology, M.H., J.H., and T.B.; visualization, J.H., C.B., E.F., J.C., and T.B.; writing—original draft, T.B.; writing—review and editing, T.S., and T.B; funding acquisition, T.S., and T.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by NASA ISGC, grant number V240132

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved as exempt by the institutional review board of the University of Idaho (23-042).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not publicly available due to the potential risk of re-identification of individual participants. Given the sensitivity of the data and the possibility of linking responses to specific students, requests to access the datasets should be directed to Tyler Bland (

tbland@uidaho.edu).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the University of Idaho undergraduate students for their time and feedback for enhancing the Medimon platform.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GBL |

Game-Based Learning |

| LLM |

Large Language Model |

| SANS |

Spaceflight-Associated Neuro-Ocular Syndrome |

| SIS-M |

Situational Interest Survey in Multimedia |

| SRL |

Self-Regulated Learning |

| STEM |

Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics |

| genAI |

Generative Artificial Intelligence |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Families and characters in the game. 1 = stage 1, 2 = stage 2, 3 = stage 3.

Table A1.

Families and characters in the game. 1 = stage 1, 2 = stage 2, 3 = stage 3.

| Family |

Healthy characters |

Diseased Characters |

| Bone |

1. Osteoclast

2. Osteoblast

3. Skeleton |

1. Osteoporosis

2. Postmenopausal Osteoporosis

3. Paget Disease |

| Muscle |

1. Myofibril

2. Muscle Fiber

3. Muscle |

1. Myasthenia Gravis

2. Epilepsy

3. Rhabdomyolysis |

| Eye |

1. Rod

2. Cone

3. Eye |

1. Retinitis Pigmentosa

2. Color Blindness

3. Glaucoma |

Appendix B

Table B1.

SIS items.

| SIS Type |

Survey Item |

| SI-triggered |

The Medimon NASA demo was interesting. |

| The Medimon NASA demo grabbed my attention. |

| The Medimon NASA demo was often entertaining. |

| The Medimon NASA demo was so exciting, it was easy to pay attention. |

| SI-maintained-feeling |

What I learned from the Medimon NASA demo is fascinating to me. |

| I am excited about what I learned from the Medimon NASA demo. |

| I like what I learned from the Medimon NASA demo. |

| I found the information from the Medimon NASA demo interesting. |

| SI-maintained-value |

What I studied in the Medimon NASA demo is useful for me to know. |

| The things I studied in the Medimon NASA demo are important to me. |

| What I learned from the Medimon NASA demo can be applied to my major/career. |

| I learned valuable things from the Medimon NASA demo. |

References

- Sweller, J. Cognitive load theory, learning difficulty, and instructional design. Learn Instr 1994, 4, 295–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Merriënboer, J.J.G.; Sweller, J. Cognitive load theory in health professional education: Design principles and strategies. Med Educ 2010, 44, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, J.Q.; Van Merrienboer, J.; Durning, S.; et al. Cognitive Load Theory: implications for medical education: AMEE Guide No. 86. Med Teach 2014, 36, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teschers, C.; Neuhaus, T.; Vogt, M. Troubling the boundaries of traditional schooling for a rapidly changing future – Looking back and looking forward. Educational Philosophy and Theory 2024, 56, 873–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuh GD., Schneider CGeary. High-impact educational practices : what they are, who has access to them, and why they matter. 2008; 35.

- Stains, M.; Harshman, J.; Barker, M.K.; et al. Anatomy of STEM teaching in North American universities. Science (1979) 2018, 359, 1468–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, S.; Eddy, S.L.; McDonough, M.; et al. Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014, 111, 8410–8415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Games2train, M.P.; York, N. Digital game-based learning. Computers in Entertainment (CIE) 2003, 1, 21–21. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, S.L.; Gantwerker, E.; Cosimini, M.; et al. Game-Based Learning in Neuroscience. Neurology Education Epub ahead of print. 2023, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamari, J.; Shernoff, D.J.; Rowe, E.; et al. Challenging games help students learn: An empirical study on engagement, flow and immersion in game-based learning. Comput Human Behav Epub ahead of print. 2016, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, M.; Oroszlanyova, M.; Farag, W. Effect of Digital Game-Based Learning on Student Engagement and Motivation. Computers 2023, 12, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Game-based learning in medical education. Front Public Health Epub ahead of print. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graafland, M.; Schraagen, J.M.; Schijven, M.P. Systematic review of serious games for medical education and surgical skills training. Br J Surg 2012, 99, 1322–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putnam, A.L. Mnemonics in education: Current research and applications. Transl Issues Psychol Sci 2015, 1, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpan, D.r.J.; Notar, D.r.C.E.; Beard, D.r.L. The Impact of Mnemonics as Instructional Tool. Journal of Education and Human Development 2021, 10, Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.B.; Mulligan, R.; Kraus, N. the Importance of Medical Mnemonics in Medicine. The Pharos.

- Assistant Professor, M.S.; Mary Zachariah Associate Professor, A.; Balakrishnan Assistant Professor, S. Effectiveness of mnemonics based teaching in medical education. Int J Health Sci (Qassim) 2022, 6, 9635–9640. [Google Scholar]

- Olu-Ajayi, F.E. The Upshot of Mnemonics on Gender and Other Learning Outcomes of Senior Secondary School Students in Biology. 2022. Available online: https://www.eajournals.org/ (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- Al-Maqbali, F.; Ambusaidi, A.; Shahat, M.A.; et al. The effect of teaching science based on mnemonics in reducing the sixth-grade female students’ cognitive load according to their imagery style. Journal of Positive Psychology 2022, 6, 2069–2084. [Google Scholar]

- Bland, T.; Guo, M. Visual Mnemonics and Gamification: A New Approach to Teaching Muscle Physiology. Journal of Technology-Integrated Lessons and Teaching 2024, 3, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, J.W.; Rummel, J.D. Long-term effects of microgravity and possible countermeasures. Advances in Space Research 1992, 12, 281–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.G.; Mader, T.H.; Gibson, C.R.; et al. Spaceflight associated neuro-ocular syndrome (SANS) and the neuro-ophthalmologic effects of microgravity: a review and an update. npj Microgravity 2020, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Winne, P.H.; Azevedo, R. Metacognition and Self-Regulated Learning. In The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences; 93–113; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, B.; Sun, T. Self-Regulated Learning and Learning Outcomes in Undergraduate and Graduate Medical Education: A Meta-Analysis. Eval Health Prof. 2024. Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dousay, T.A. Effects of redundancy and modality on the situational interest of adult learners in multimedia learning. Educational Technology Research and Development 2016, 64, 1251–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dousay, T.A.; Trujillo, N.P. An examination of gender and situational interest in multimedia learning environments. British Journal of Educational Technology 2019, 50, 876–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bland, T. Enhancing Medical Student Engagement Through Cinematic Clinical Narratives: Multimodal Generative AI–Based Mixed Methods Study. JMIR Med Educ 2025, 11, e63865. Available online: https://mededujmirorg/2025/1/e63865. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bland, T.; Guo, M.; Dousay, T.A. Multimedia design for learner interest and achievement: a visual guide to pharmacology. BMC Medical Education 2024, 24, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worthley, B.; Guo, M.; Sheneman, L.; et al. Antiparasitic Pharmacology Goes to the Movies: Leveraging Generative AI to Create Educational Short Films. AI 2025, 6, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, J.D.; Cummings, K.; Phys, A.J. Normalized change. Am J Phys 2007, 75, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Wang, L.; Fard, P.; et al. An Agentic AI Workflow for Detecting Cognitive Concerns in Real-world Data. 2025. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.01789v1 (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Li, X. A Review of Prominent Paradigms for LLM-Based Agents: Tool Use (Including RAG), Planning, and Feedback Learning. 2024. Available online: http://arxiv.org/abs/2406.05804 (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Wang, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, L.; et al. Review of Large Vision Models and Visual Prompt Engineering. Meta-Radiology 2023, 1, 100047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.; Fu, Q.; Hays, S.; et al. A Prompt Pattern Catalog to Enhance Prompt Engineering with ChatGPT. 2023. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2302.11382v1 (accessed on 23 September 2024).

- Qureshi, A.; Rizvi, F.; Syed, A.; et al. The method of loci as a mnemonic device to facilitate learning in endocrinology leads to improvement in student performance as measured by assessments. Adv Physiol Educ 2014, 38, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R.W.; Brown, S.D.; Hackett, G. Toward a Unifying Social Cognitive Theory of Career and Academic Interest, Choice, and Performance. J Vocat Behav 1994, 45, 79–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, J. Who Am I and What Am I Going to Do With My Life? Personal and Collective Identities as Motivators of Action. Educ Psychol 2009, 44, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, J.P. What video games have to teach us about learning and literacy. Computers in Entertainment (CIE) 2003, 1, 20–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, D.W.; Gee, J.P. How computer games help children learn. In How Computer Games Help Children Learn; 1–242; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Couch, S.; Estabrooks, L.; et al. Role models’ influence on student interest in and awareness of career opportunities in life sciences. International Journal of Science Education, Part B 2023, 13, 381–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, D.E. Role models in career development: New directions for theory and research. J Vocat Behav 2004, 65, 134–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, M.; Lam, B.Q.; Tuan Ngoc Bui, A. Career exploration and its influence on the relationship between self-efficacy and career choice: The moderating role of social support. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R.W.; Brown, S.D.; Hackett, G. Toward a Unifying Social Cognitive Theory of Career and Academic Interest, Choice, and Performance. J Vocat Behav 1994, 45, 79–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, A.; Chow, C.S.; Feig, A.L.; et al. Exposure to multiple career pathways by biomedical doctoral students at a public research university. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0199720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, R.; Daniels, R.J.; Gilliland, G.; et al. A new data effort to inform career choices in biomedicine. Science (1979) 2017, 358, 1388–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tullis, J.G.; Benjamin, A.S. On the effectiveness of self-paced learning. J Mem Lang 2011, 64, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhode, J.F. Interaction Equivalency in Self-Paced Online Learning Environments: An Exploration of Learner Preferences. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning 2009, 10, Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, N. The use and impact of game-based learning on the learning experience and knowledge retention of nursing undergraduate students: A systematic literature review. Nurse Educ Today 2022, 117, 105484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).