1. Introduction

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infection is a chronic disease that remains a global public health concern. According to the updated data in the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) report, an estimated 39.9 million people are living with HIV, of whom 30.7 million have access to antiretroviral therapy (ART). This has contributed to a 69% decrease in AIDS-related deaths in 2023 compared to 2004 [

1].

Although mortality among people with HIV undergoing ART has decreased, it remains higher than that of the general population. The causes of death have changed over time as the HIV-positive population ages, with an increase in non-AIDS-related causes of death [

2]. Non-AIDS comorbidities, which tend to become the leading causes of death, include non-AIDS cancers, cardiovascular diseases, and metabolic complications [

3].

A prospective study of the Danish HIV cohort, compared to the general population, which assessed subclinical and obstructive coronary atherosclerosis (≥50% stenosis) using coronary computed tomography angiography, demonstrated that HIV is independently associated with a twofold higher risk of any form of subclinical coronary atherosclerosis and a threefold higher risk of obstructive coronary atherosclerosis. These results were reported after adjusting for cardiovascular risk factors, including age, sex, hypertension, dyslipidemia, active smoking, overweight or obesity, and diabetes, providing a possible explanation for the increased risk of myocardial infarction in people living with HIV [

4].

The risk of cardiovascular disease-related death is correlated with metabolic syndrome (MetS), characterized by the presence of at least three of the following criteria: abdominal obesity (waist circumference ≥102 cm in men and ≥88 cm in women), hypertension, elevated triglyceride levels (≥150 mg/dL or treatment for hypertriglyceridemia), low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL) levels (<40 mg/dL in men and <50 mg/dL in women), and insulin resistance or hyperglycemia (fasting blood glucose ≥100 mg/dL or type 2 diabetes). In recent decades, the prevalence of MetS among people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWH) has increased, varying by geographic region. The risk of MetS is associated with both traditional factors and factors related to HIV and antiretroviral therapy (ART). A meta-analysis of 102 studies from five continents found an overall combined prevalence of MetS in PLWH of 25.3%, with a 1.5-fold higher risk among individuals exposed to ART and a 1.6-fold higher risk than in HIV-uninfected individuals [

5].

The European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC) classifies Romania as a high-risk country in terms of cardiovascular risk, according to the SCORE2-OP model [

6].

Additionally, a 2024 report from the World Health Organization (WHO) indicates an increase in obesity prevalence to 38.2% among the adult population in Romania, the highest rate in Europe, which constitutes one of the explanations for the country’s elevated cardiovascular risk [

7]. People with obesity are at increased risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and death, and individuals living with HIV are part of this epidemic [

7].

Currently, over 18,000 people with HIV live in Romania, but no available data exist regarding obesity rates and cardiovascular risk in this population [

8]. Beyond the general conditions contributing to weight gain, antiretroviral therapy is an additional risk factor for obesity, affecting different populations unequally. Factors associated with weight gain after ART initiation include immune recovery in individuals with advanced immunosuppression, metabolic changes due to exposure to new antiviral molecules, older age, genetic factors, and lifestyle factors. In the coming years, it is estimated that obesity and cardiometabolic complications will rank among the leading causes of death and disability among PLWH [

9,

10,

11].

The objective of this study is to evaluate obesity and cardiovascular risk in HIV-positive individuals receiving antiretroviral treatment at a clinic in southeastern Romania, in relation to the clinical, biological, and therapeutic status of HIV/AIDS infection. The purpose of the study is to identify local intervention priorities to improve the management of HIV-positive patients in our site.

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study on the health status of HIV-seropositive individuals receiving antiretroviral (ARV) treatment and monitored at the HIV/AIDS Day Clinic of the Clinical Hospital for Infectious Diseases in Galați, located in southeastern Romania.

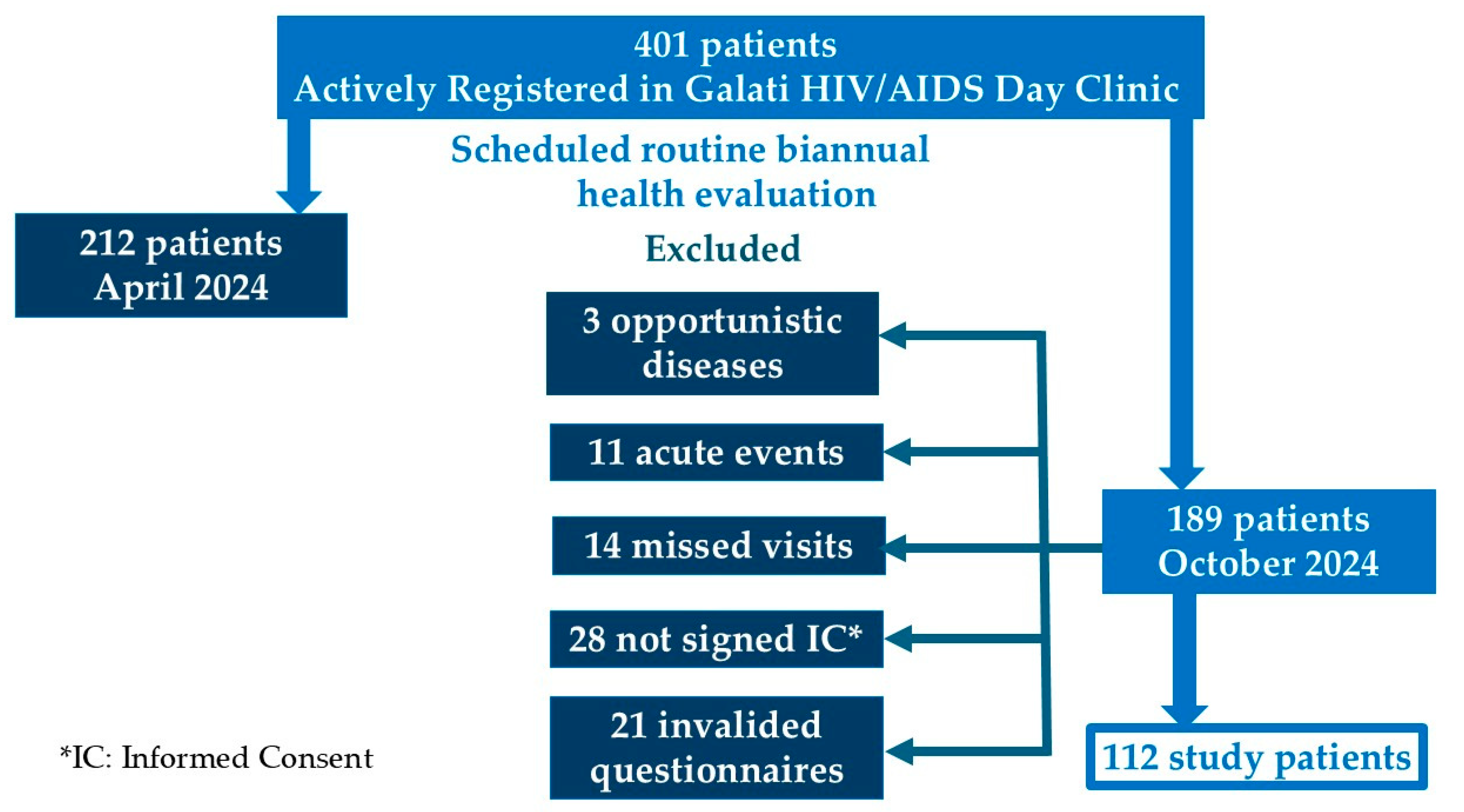

Out of the 401 patients actively registered in the clinic (defined as having attended at least one follow-up visit in the last six months), 112 patients participated in the study. These patients attended their scheduled biannual health evaluation in October 2024, following the local HIV/AIDS monitoring and treatment protocol, in accordance with the recommendations of the European AIDS Clinical Society (EACS) guidelines [

12].

The inclusion criteria were age over 18 years, a minimum of one year on the current ARV therapy, absence of opportunistic infections or other acute illness-related conditions, and written informed consent for participation in a questionnaire-based study [

Figure A1]. The study included an inventory and grading of self-reported symptoms, therapeutic adherence (percentage of correctly taken ARV doses over 30 days relative to the prescribed doses), and a physical activity index [

13].

Demographic data (age, sex, living environment, education level, and marital status) and medical history regarding comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, obesity), duration of HIV diagnosis, clinical-immunological stage of infection, number of antiretroviral regimens experienced, type, and duration of current therapy were collected from the clinic’s database [

14]. We classified patients based on their clinical-immunological stage into AIDS and non-AIDS groups, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 1993 classification [

14].

During the routine monitoring visit, patients underwent a complete clinical examination, their self-reported therapeutic adherence was assessed (percentage of correctly taken ARV doses over 30 days relative to the prescribed doses), and blood samples were collected for standard laboratory tests [

12]. The following data were recorded: systolic and diastolic blood pressure, weight, height, and abdominal circumference, CD4 count, HIV-RNA viral load, leukocyte count, hemoglobin, platelets, blood glucose, total cholesterol, HDL, LDL, and triglycerides, C-reactive protein (CRP), interleukin-6 (IL-6), aspartate transaminase (AST), alanine transaminase (ALT), and co-infections with hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), and syphilis. Dyslipidemia was defined as dysregulation in the lipid profile [

15].

Using weight (W/kg) and height (H/cm) measurements, we calculated the body mass index (BMI = W/H²) and categorized participants as underweight (<18.5 kg/m²), normal weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m²), overweight (25–29.9 kg/m²) or obese (≥30 kg/m²) according to the WHO classification. Abdominal circumference (cm) was categorized as increased (94–102 cm in men and 80–88 cm in women) and very high (>102 cm in men and >88 cm in women) [

16,

17].

The physical activity index classified patients into three groups: active, moderately active, and inactive, based on the General Practice Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPPAQ) [

17,

18,

19].

We calculated the 5-year and 10-year cardiovascular risk (CVR) using the D:A:D® score, recommended for HIV-positive individuals, which incorporates traditional risk factors (age, sex, smoking, family history of cardiovascular disease and diabetes, total cholesterol, HDL, and LDL levels) along with CD4 immune status [

20].

For patients over 40 years old, we additionally calculated the 10-year CVR using the SCORE2-OP algorithm, identifying the corresponding risk age [

6,

21].

Considering each algorithm, patients were categorized based on risk levels into the following groups: <1%, 1–2.5%, 2.5–5%, 5–10%, 10–20%, and >20%.

The patient self-reported symptoms inventory assessed and graded symptoms on a scale from 0 (absence) to 4 (persistent symptoms/maximal intensity). The evaluated symptoms included fatigue, fever, dizziness, tingling, memory decline, nausea, diarrhea, depression, anxiety, insomnia, pruritus, cough, headache, loss of appetite, abdominal bloating, muscle pain, sexual dysfunction, hair loss, and weight gain or loss. The global score was the sum of individual symptom scores, ranging from 0 to 80, with higher scores indicating greater patient distress [

22].

Based on the D:A:D ® 5-year score, a CVR >5% was considered significant, and all patients were classified accordingly. To analyze factors associated with this risk, numerical data were grouped into categorical variables: age over 40 years (Yes/No), undetectable HIV-RNA (Yes/No), CD4 > 500/mm³ (Yes/No), dyslipidemia (Yes/No), AC (normal/high/very high), and BMI (obese/overweight/normal) [

23].

For statistical analysis, we used XLSTAT statistical analysis software, version 2020.1. We evaluated numerical and categorical variables representing dependent variables for CVR and independent variables, including demographic, clinical, and HIV-specific factors. Descriptive statistics were used to determine mean, standard deviation, median, range, data distribution, and normality testing for numerical variables, as well as absolute and relative frequencies for categorical variables. A univariate analysis of 5-year CVR stratified patients by age into groups below and above 40 years. Additionally, patients with a high CVR were identified as those with a predicted 5-year D:A:D ® score ≥ 5%. Depending on variable types and distribution, we compared these groups using Student’s t-test, Mann-Whitney U test, and Chi-square test (χ²). We also calculated Pearson’s correlation coefficient to evaluate relationships between scores and clinical variables. Significant differences were defined as p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic, Clinical, and Biological Characteristics of PLWH

The study group of 112 subjects consists predominantly of young individuals under the age of 40 (60.36%), with a majority being male (57.66%). Most participants have at least 12 years of education (70.54%) and reside in urban areas (73.21%). Only 21.11% of patients maintain an active lifestyle, while 29.49% consume alcohol, and 55.36% are smokers.

The median duration since HIV diagnosis is 11 years, ranging from 1 to 30 years. Notably, 25.89% of the patients in the study are survivors of the specific Romanian pediatric HIV cohort, having been nosocomially infected between 1988 and 1990 [

24]. The AIDS stage was identified in 59.85% of cases and 54.4% of patiens had experienced a nadir of CD4 below 200/mm

3. Exposure to antiretroviral therapy (ART) varied between 1 and 11 combinations, with a median of 3.

Regarding current ART regimens, the most commonly used combinations include Bictegravir/Emtricitabine/Tenofovir Alafenamide (43.75%), Dolutegravir/NRTI (22.32%), and Doravirine/Lamivudine/Tenofovir Disoproxil (13.39%), while other combinations account for 11.60%. The median duration of the current ART regimen is 2 years [

Table A1].

3.2. Profile of Subjective Complaints

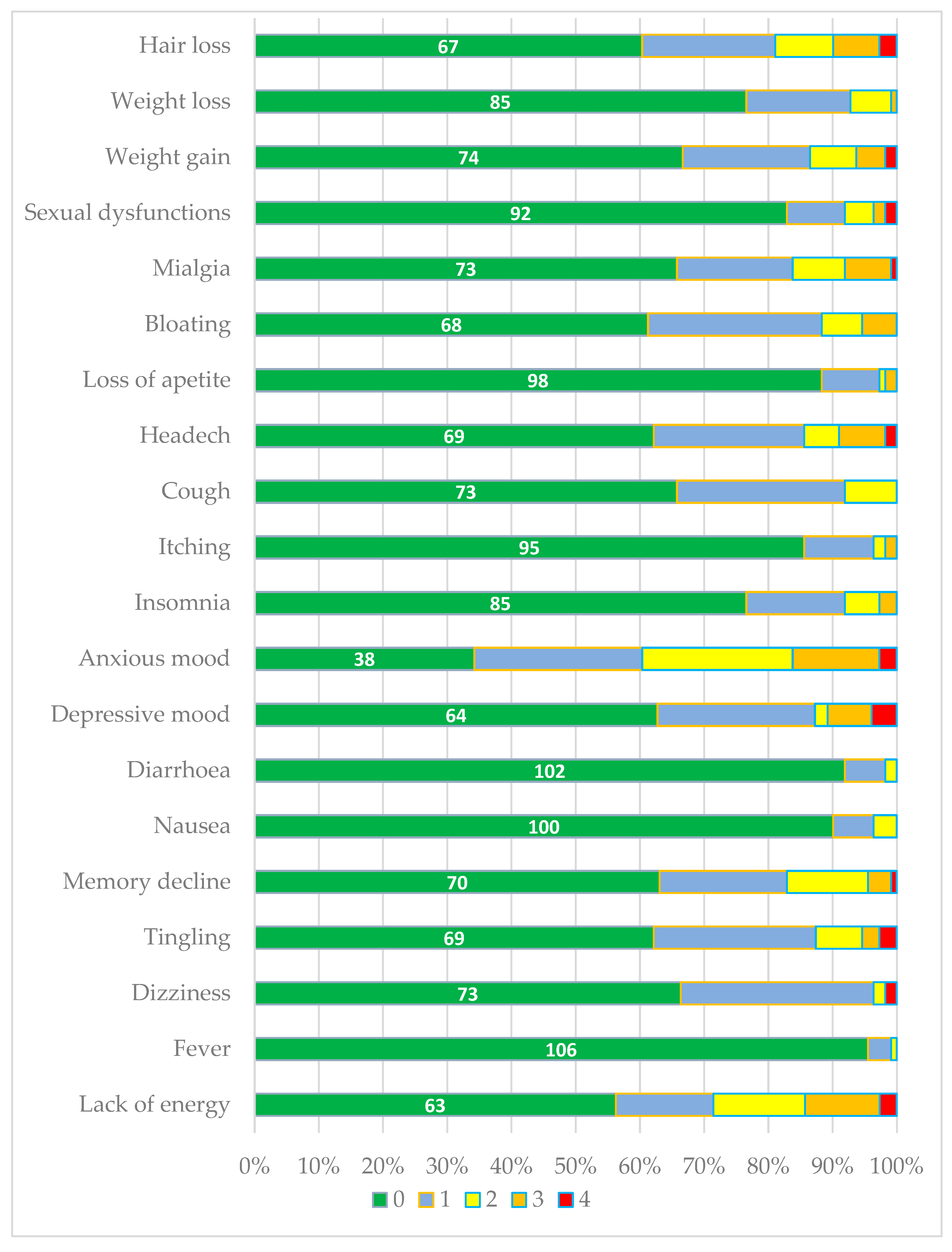

In general, patients were in good condition, with few subjective complaints, most of which were of mild intensity. The total score ranged from 0 to 34/80, with a mean of 9.6±6.9.

Anxiety-related mood disturbances were the most frequently reported symptoms affecting HIV patients, with over half of the respondents experiencing them [

Figure 1].

The second most common group of issues, affecting at least one-third of patients, included psycho-neurosensory symptoms such as reduced energy, depressive mood, tingling sensations, memory impairment, headaches, dizziness, as well as metabolic manifestations like weight gain, bloating, or hair loss. Mild (grade 1) and moderate (grade 2) cough was reported by 34% of patients, the majority of whom were smokers (OR=3.12; p=0.011).

Other symptoms, including fever, nausea, diarrhoea, ichting, insomnia, sexual dysfunction, loss of appetite, and weight loss, were reported less frequently and were of mild to moderate intensity. An exception was noted in two patients who reported severe (grade 4) sexual dysfunction [

Figure 1].

The average adherence to ART was 95%±0.08, but 37.5% of patients had suboptimal adherence (<95%).

3.3. Obesity, Metabolic Syndrome, and Cardiovascular Risk

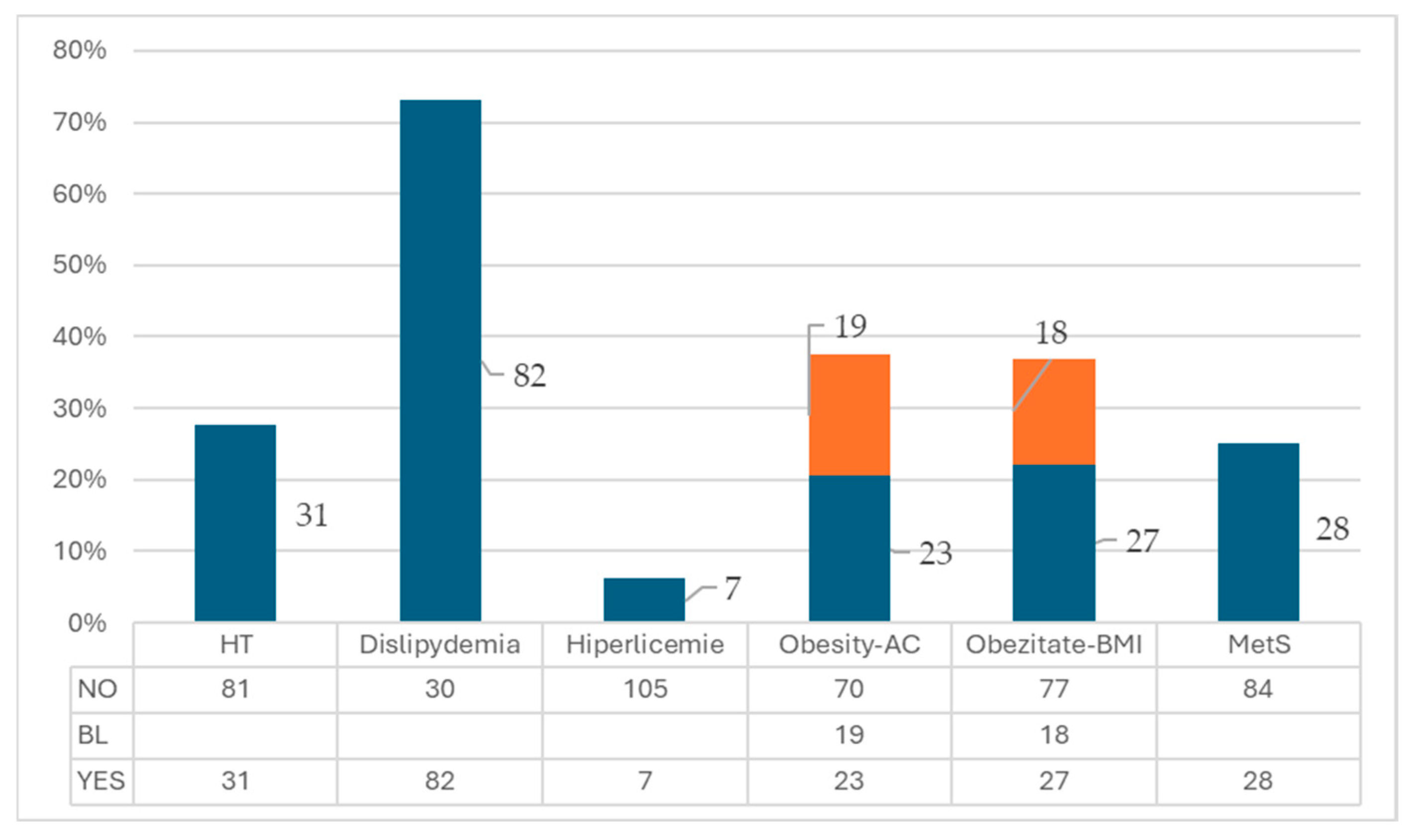

The BMI ranged from 17.95 kg/m² to 41.11 kg/m², with a mean value of 25.76±4.69. Based on the BMI value, 20.54% (23/112) of patients were obese, while 16.96% (19/112) were overweight.

Abdominal circumference ranged from 55 cm to 120 cm, with a mean value of 85.82±14.69. When compared to normal values according to gender, 16.7% (18/112) of patients had increased measurements, and 24.11% (27/112) had very high values, which were considered criteria for metabolic syndrome. 25% (28/112) of patients met at least 3 criteria for the diagnosis of metabolic syndrome. Hypertension was identified in 27.68% (31/112) of patients, dyslipidemia in 72.21% (82/112), and hyperglycemia in 7.07% (7/112) [

Figure A2].

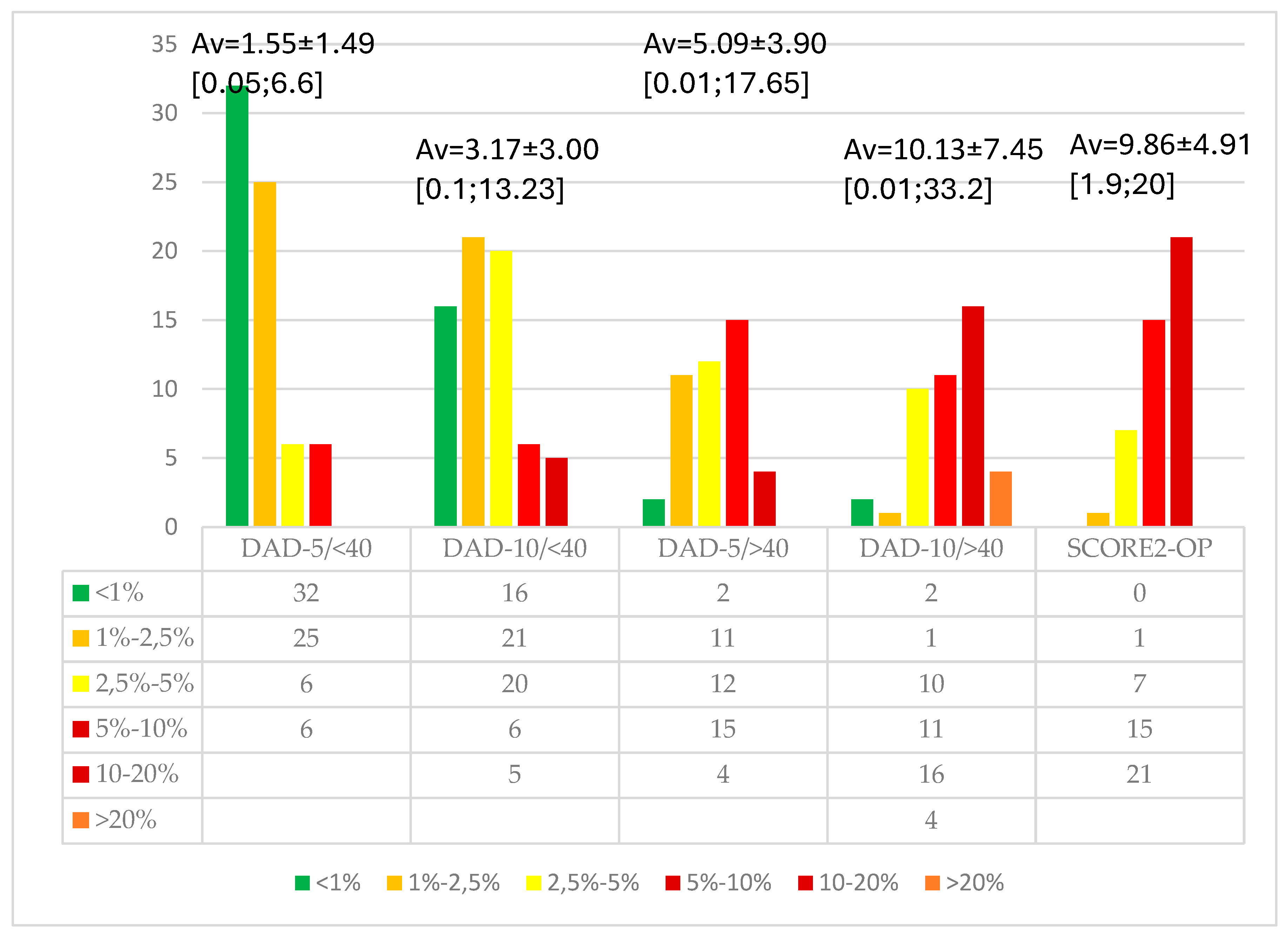

We calculated the cardiovascular risk in patients over 40 years of age, finding a very strong correlation between the values of the DAD (R) -10 years score and the SCORE2-OP score (correlation coefficient 0.95; p<0.001), although the criteria for these scores are partially different [

Figure 2]. The type of current ARV medication did not correlate with obesity, AC, MetS, or CVR in any age group, whether over or under 40 years.

The corresponding age of cardiovascular risk was higher by 7.5±5.10 years compared to chronological age (ranging from 0 to 18 years), according to the SCORE2-OP, demonstrating accelerated aging in PLWH.

The CVR for PLWH under 40 years of age is low, with a median of 1.79% at 5 years. Over the age of 40, the risk is 2 times higher (3.86%). Regardless of age group, the 10-year cardiovascular risk doubles (3.68% and 7.85%, respectively).

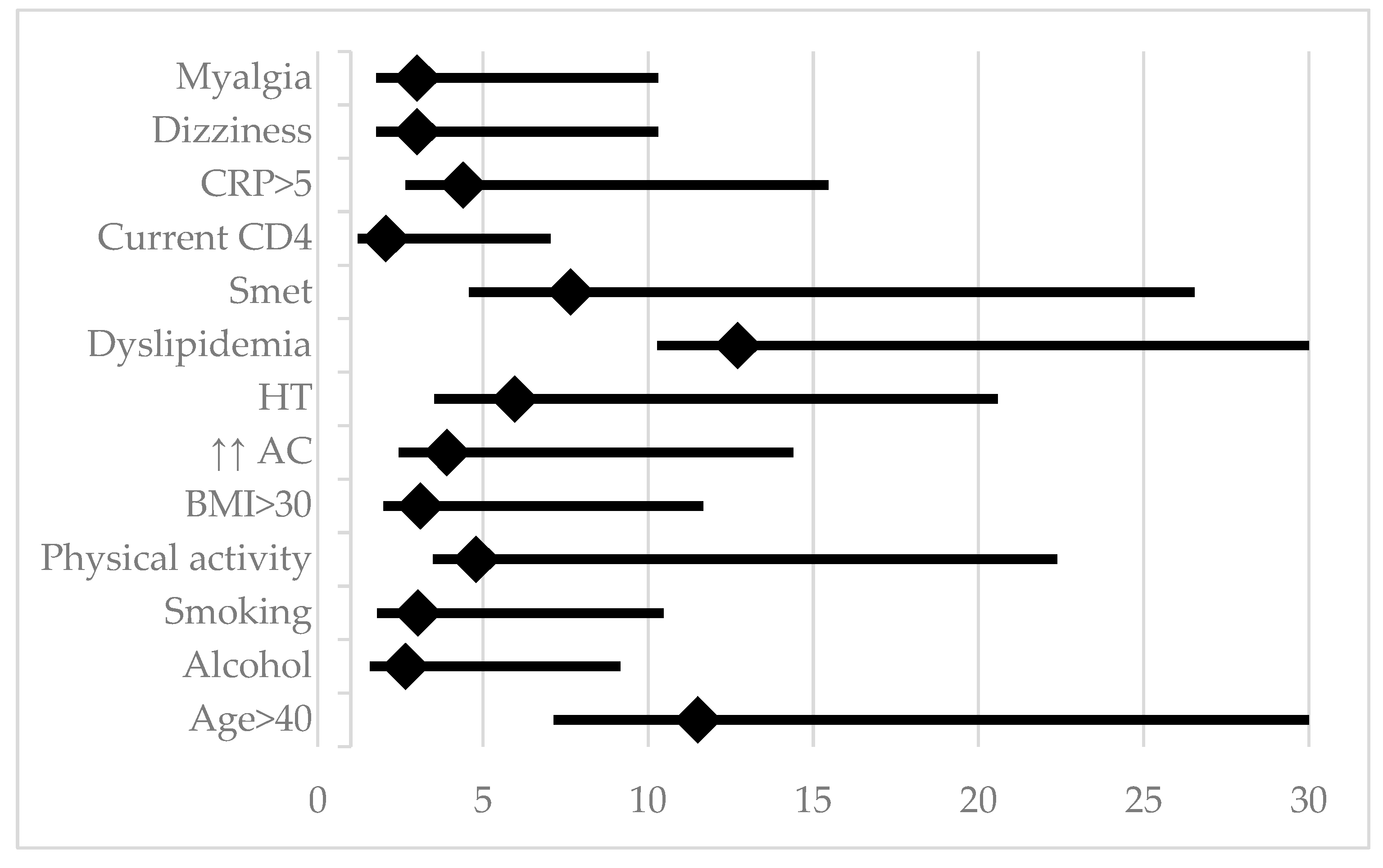

Referring to the DAD® score, we found a cardiovascular risk higher than 5% in the next 5 years in 23.21% of PLWH. Analyzing the influence of demographic, behavioral, metabolic, and HIV-specific factors, age over 40 years, smoking, alcohol consumption, and lack of sustained physical activity were highlighted, while education level, living environment, and male gender had no significant impact. Patients with moderate physical activity were not included in the analysis, as their behavior may evolve toward sedentary lifestyles with age. HIV-specific factors, such as diagnosis duration, AIDS stage, HIV-RNA levels, CD4 count, duration and type of ART, or therapeutic adherence, did not have a significant influence on the increase in 5-year cardiovascular risk. Among inflammatory markers, elevated C-RP values (but not IL-6) were associated with a CVR >5% [

Table 1;

Figure 3]. CRP remained significantly associated with cardiovascular risk, even after adjusting for smoking in the logistic regression.

Subjectively, dizziness and myalgia were associated with a higher CVR. Although the difference was not statistically significant, the symptoms score was higher in PLWH with CVR >5% compared to those with lower risk (11.92±8.14 vs. 8.76±6.38; p=0.078).

4. Discussion

4.1. Cardiovascular Risk and Inflammation

In our study, CVR was correlated with CRP, but not with IL-6.

The value of CRP as a biomarker in assessing cardiovascular risk is confirmed by its inclusion in several prevention guidelines, most recently in the 2024 ESC Guidelines for Chronic Coronary Syndrome [

25]. However, its utility is limited by genetic variations and the fact that it reflects systemic inflammation. IL-6 is a key factor in the pathophysiology of cardiovascular diseases. Produced by macrophages, monocytes, endothelial cells, vascular smooth muscle cells, and fibroblasts, IL-6 plays an important role in the development of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and the destabilization of plaques, making them susceptible to rupture [

26]. Compared to C-RP, IL-6 plays a more central role in the inflammatory cascade, stimulating the secretion of acute-phase proteins, including C-RP, and has a more significant role in predicting cardiovascular risk [

27,

28].

However, interpreting the significance of IL-6 values is limited by its short half-life and the high variability of its concentration in healthy individuals, influenced by factors like the postprandial state, physical activity, and circadian variations. Currently, there are no validated tests or standardized methods for sample collection to reliably assess IL-6 levels and their impact on cardiovascular risk. In contrast, CRP has a longer half-life and more stable levels, making it more widely applicable for cardiovascular risk assessment [

28].

4.2. Subjective Manifestations Associated with Cardiovascular Risk

Profile of self-reporting symptoms in the monitoring of patients with HIV is an important tool for signaling various health issues, drawing attention to the association with CVR and the need for further investigations.

Our study found that CVR was associated with reported symptoms such as dizziness and myalgia. Comparative data were identified in a large multicenter study on patients with atrial fibrillation, where dizziness was reported between 19% and 44%, along with other symptoms such as fatigue (26%–75%) and anxiety (12%–50%) [

29,

30]. It could be speculated that episodes of atrial fibrillation may be related to dizziness in the group of our patients with cardiovascular risk.

Dizziness is a symptom associated with 47-75% of patients with posterior stroke, as highlighted by a prospective study of a large database. However, in practice, interpreting this symptom as an alert for vascular brain complications requires the exclusion of other causes, such as low blood pressure, migraines, stress or anxiety, hypoglycemia, dehydration, motion sickness, or anemia. Patients who report dizziness need to undergo a neurological examination to detect other neurological signs and symptoms, assess cardiovascular risk factors, and have imaging studies to document vascular involvement [

31]. A meta-analysis of 20 studies showed that individuals with chronic musculoskeletal pain have a 1.91 times higher risk of associating cardiovascular diseases compared to those without pain [CI 1.64-2.21]. These results are consistent with the observations of patients in our study, but the association between musculoskeletal pain and various cardiovascular diseases remains unclear, requiring further studies in the future [

32].

4.3. Infection with HIV and the Cardiovascular Risk

The epidemiology of cardiovascular diseases in people living with HIV (PLWH) varies by geographic region, considering exposure to environmental factors, genetic differences among populations, the prevalence of traditional risk factors, as well as the clinical manifestations of HIV, co-infections, and the public health impact of HIV infection [

33].

Inflammation and the activation of both the innate and adaptive immune responses play a crucial role in atherogenesis and the pathogenesis of cardiovascular diseases in the general population, a process exacerbated by changes associated with HIV infection [

34,

35].

Antiretroviral therapy (ART) has significantly increased the life expectancy of PLWH. However, despite achieving complete viral suppression under therapy, PLWH maintain a persistently elevated inflammatory state compared to the non-HIV population. This is explained by the persistence of HIV in reservoirs, intestinal bacterial translocation, co-infections—particularly with Cytomegalovirus - and the incomplete recovery of adaptive immune deficits altered by HIV. Epidemiological studies indicate an increased risk of cardiovascular events or advanced atherosclerosis in PLWH with elevated inflammatory biomarkers, heightened monocyte activation, and a prothrombotic state (e.g., elevated D-dimer levels) [

33,

36].

While older-generation antiretroviral drugs were associated with a higher risk of myocardial infarction, newer antiretroviral regimens containing integrase strand transfer inhibitors (INSTIs) have a lesser impact on lipid profiles, suggesting a potentially lower cardiovascular risk. However, INSTI-based therapy has been linked to weight gain, particularly in women, and its role in cardiovascular risk (CVR) remains unclear. Overall, the benefits of early ART initiation are indisputable, as viral suppression is associated with a lower risk of opportunistic infections and cardiovascular complications, along with reduced residual inflammatory levels compared to those who start ART late due to delayed diagnosis [

37,

38].

Various guidelines for CVR calculation, whether HIV-specific or general, reflect the low predictive accuracy of these models in PLWH, as well as the variability of absolute atherosclerotic disease risk across different regions [

34]. Standard CVR prediction scores for the general population tend to underestimate the risk in PLWH, who exhibit two distinct types of myocardial infarction (MI). Plaque rupture and atherothrombosis are the primary mechanisms of MI in the general population, but they account for only 50% of MIs in PLWH. The remaining cases occur in the absence of atherogenesis, driven by structural abnormalities of the coronary vessels, dilated cardiomyopathy, and the influence of other HIV-specific factors [

39].

The updated guidelines of the American Heart Association suggest using locally validated standard risk scores while adjusting the estimated risk by a factor of 1.5 to 2 in PLWH, particularly in cases of persistent viremia or other high-risk markers [

25].

In our study, we found a strong correlation between the prediction of the standard SCORE2-OP score (adjusted for country-specific risk) and the D:A:D score for PLWH, estimated over a 10-year period for individuals over 40 years old. However, standard risk scores are not applicable for individuals under 40, despite the significant CVR in PLWH due to accelerated aging [

40].

Limitations of the Study

The main limitations of our study are the relatively small sample size and the inherent heterogeneity of the HIV population in terms of transmission routes, duration of infection, and broad age range. Given the numerous factors that influence CVR, a larger sample size would be essential for drawing more reliable and generalizable conclusions. Nevertheless, we believe that our findings provide preliminary data that could inform a future large-scale, multicentre national study.

5. Conclusions

The prevalence of obesity among PLWH in Galați, Romania, was 24.1%. According to the DAD(R) score, 23.21% of these patients have a 5-year CVR exceeding 5%. The DAD(R) score for a 10-year CVR correlates with the SCORE2-OP score in PLWH over 40 years old, indicating an additional average cardiovascular age of 7.5 years compared to chronological age. Cardiovascular risk in PLWH in Romania is influenced by age, obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, low physical activity, smoking, and alcohol consumption, while HIV-specific factors did not show a significant impact. A prevention program for cardiovascular events in this special population living with HIV in Romania should focus on promoting a healthy lifestyle, improving therapeutic adherence, ensuring sustained viral suppression, controlling blood pressure and dyslipidemia, and providing access to statins by including it in the national HIV-associated therapy protocol.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A., A.P.-C. and C.G.; methodology, M.A. and A.-A.A.; software, A.-A.A.; validation, C.G., A.P.-C. and A.-A.A.; formal analysis, M.A. and A.-A.A.; investigation, M.A., C.B. and G.-E.A.; data curation, C.B. and G.-E.A.; writing—original draft preparation, C.G., A.P.-C., C.B., and G.-E. A.; writing—review and editing, M.A. and A.-A.A.; visualization, C.G. and A.P.-C.; supervision, M.A.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Clinic Hospital for Infectious Diseases Galati no.1/5 date 21.01.2025.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was not applicable due to the retrospective nature of this study, but all the patients signed the informed consent of agreement to be used the personal data for medical statistical analysis.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available and can be shared on reasonable request sent to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AC |

Abdominal Circumference |

| AIDS |

Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome |

| ALT |

Alanine transaminase |

| AST |

Aspartate transaminase |

| ART |

antiretroviral therapy |

| Av |

Average |

| BMI |

Body mass index |

| BIC |

Bictegravir |

| CD4 |

Cluster of Differentiation 4 co-receptor for the T-cell receptor |

| CDC |

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| C-RP |

C-reactive protein |

| CVR |

Cardiovascular risk |

| EACS |

European AIDS Clinical Society |

| EAPC |

European Association of Preventive Cardiology |

| DEL |

Doravirine/lamivudine/tenofovir |

| DLG |

Dolutegravir |

| GPPAQ |

General Practice Physical Activity Questionnaire |

| HT |

Hypertension |

| HBV |

Hepatitis B virus |

| HCV |

Hepatitis C virus |

| HBs-Ag |

Hepatitis B surface antigen |

| HVC-Ab |

anti-HCV

|

| Hb |

Hemoglobin |

| HDL |

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| HIV |

Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| HIV-RNA |

Test of HIV ribonucleic acid

|

| IL-6 |

Interleukin-6 |

| LDL |

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| MetS |

Metabolic syndrome |

| NRTI |

Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors |

| OR |

Odd ratio |

| PLWH |

People living with HIV/AIDS |

| TPHA |

Treponema pallidum hemagglutination assay |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

| UNAIDS |

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS |

| VDRL |

Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (syphilis antibody) |

| WBC |

White blood cells |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Demographic and Clinical-Biological Characteristics of PLWH.

Table A1.

Demographic and Clinical-Biological Characteristics of PLWH.

| |

Average± SD |

Median |

Min; Max |

P |

| Age [years old] |

38,97 ±9,95 |

36 |

19; 73 |

<0,001 |

| Length of HIV diagnostic [years] |

10,69±7,09 |

11 |

1;30 |

<0,001 |

| No of experienced ARV |

3,43±2,3 |

3 |

1; 11 |

<0,001 |

| Length of current ARV |

2,91±1,79 |

2 |

1; 10 |

<0,001 |

| CD4 [-/mm3] |

574,83±286,83 |

567 |

7; 1343 |

<0,001 |

| WBC [-/mm3] |

6280±2049 |

6000 |

1260; 11700 |

<0,001 |

| Hb [g/dl] |

14,35±1,85 |

14,7 |

8,9; 17,9 |

<0,001 |

| Platelets [-/mm3] |

231926±69563 |

224500 |

458000 |

<0,001 |

| CRP [ng/l] |

4,85±10,82 |

1,21 |

0,01; 80 |

<0,001 |

| IL-6 |

7,66±6,09 |

5,73 |

2; 33 |

<0,001 |

| Glicemia [mg/dl] |

104,24±16,09 |

102 |

78;202 |

0,006 |

| Creatinine [mg/dl] |

0,95±0,17 |

0,95 |

0,52; 1,44 |

<0,001 |

| Cholesterol-Total [mg/dl] |

208,92±48,25 |

211 |

33;347 |

<0,001 |

| HDL- Cholesterol [mg/dl] |

58,91±32,43 |

52 |

21; 297 |

<0,001 |

| LDL- Cholesterol [mg/dl] |

122,41±40,92 |

117,5 |

49; 243 |

<0,001 |

| Triglycerides [mg/dl] |

149,53±98,45 |

118 |

42; 548 |

<0,001 |

| Albumine [mg/dl] |

4,66±0,44 |

4,71 |

1,65; 5,82 |

<0,001 |

| ALT [UI/L] |

33,20±33,29 |

24 |

9; 247 |

<0,001 |

| AST [UI/L |

32,70±38,81 |

24,75 |

14; 347 |

<0,001 |

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Categories |

n |

% |

p |

| Age |

≥40 years old |

44 |

39,64 |

0,029 |

| |

<40 years old |

67 |

60,36 |

| Gender |

Female |

47 |

42,34 |

0,106 |

| |

Male |

64 |

57,66 |

| Living |

Rural |

30 |

26,79 |

<0,001 |

| |

Urban |

82 |

73,21 |

|

| High school education/over |

No |

33 |

29,46% |

<0,001 |

| Yes |

79 |

70,54% |

|

| Smoking |

Yes |

50 |

44,64 |

0,256 |

| No |

62 |

55,36 |

| Alcohol |

Yes |

33 |

29,46 |

<0,001 |

| No |

79 |

70,54 |

| Physical activity index |

Inactive |

22 |

19,64% |

<0,001 |

| Moderate |

63 |

56,25% |

| |

Active |

27 |

24,11% |

| AIDS |

Yes |

67 |

59,82% |

0,037 |

| No |

45 |

40,18% |

| CD4 |

<500/mm3

|

44 |

39,29% |

0,023 |

| ≥500/mm3

|

68 |

60,71% |

| ARN-HIV |

Detectable |

22 |

19,64 |

<0.001 |

| Undetectable |

90 |

80,36 |

| Current ARV |

BIC |

49 |

43,75% |

<0,001 |

| DLG/NNRTI |

25 |

22,32% |

| DEL |

15 |

13,39% |

| Others |

13 |

11,60% |

| HBs-Ag |

Positive |

7 |

6,03 |

<0,001 |

| Negative |

104 |

93,69 |

| HVC-Ab |

Positive |

1 |

0,9 |

<0,001 |

| Negative |

110 |

99,1 |

| VDRL |

Positive |

5 |

4,50 |

<0,001 |

| Negative |

106 |

95,5 |

| TPHA |

Positive |

14 |

12,61 |

<0,001 |

| Negative |

97 |

87,39 |

Figure A1.

Flow Diagram of Study Patient Selection.

Figure A1.

Flow Diagram of Study Patient Selection.

Figure A2.

Frequency of Metabolic Syndrome Criteria. Legend: AC= Abdominal Circumference; BL= Border line; HT= Hypertension; MetS= Methabolic Syndrome.

Figure A2.

Frequency of Metabolic Syndrome Criteria. Legend: AC= Abdominal Circumference; BL= Border line; HT= Hypertension; MetS= Methabolic Syndrome.

References

- UNAIDS DATA 2024. Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; 2024. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.Dec 2, 2024. Availabe online:https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/UNAIDS_FactSheet_en.pdf. (Accessed on: 25.12.2024).

- Trickey, A.; McGinnis, K.; Gill, M. J.; Abgrall, S.; Berenguer, J.; Wyen, C.; Hessamfar, M.; Reiss, P.; Kusejko, K.; Silverberg, M. J.; et al. Longitudinal trends in causes of death among adults with HIV on antiretroviral therapy in Europe and North America from 1996 to 2020: a collaboration of cohort studies. Lancet HIV 2024, 11 (3), e176-e185. [CrossRef]

- Nomah, D. K.; Jamarkattel, S.; Bruguera, A.; Moreno-Fornés, S.; Díaz, Y.; Alonso, L.; Aceitón, J.; Llibre, J. M.; Domingo, P.; Saumoy, M.; et al. Evolving AIDS- and non-AIDS Mortality and Predictors in the PISCIS Cohort of People Living With HIV in Catalonia and the Balearic Islands (Spain), 1998-2020. Open Forum Infect Dis 2024, 11 (4), ofae132. [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, A.D; Fuchs, A.; Benfield, T.; Køber, l.; Nordestgaard, B. G.; Afzal, S.; Kuhl, J. T.; Sigvardsen, P.F.; Suarez-Zdunek, M. A; Gelpi, M.; Nielsen, S. D.; Kofoed, K.F. HIV Is Associated With Subclinical Coronary Atherosclerosis: A Prospective Matched Cohort Study, Clinical Infectious Diseases, 2025;, ciae609. [CrossRef]

- Trachunthong, D.; Tipayamongkholgul, M.; Chumseng, S.; Darasawang, W.; Bundhamcharoen, K. Burden of metabolic syndrome in the global adult HIV-infected population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2024, 24 (1), 2657. [CrossRef]

- collaboration, S.-O. w. g. a. E. C. r. SCORE2-OP risk prediction algorithms: estimating incident cardiovascular event risk in older persons in four geographical risk regions. Eur Heart J 2021, 42 (25), 2455-2467. [CrossRef]

- World Obesity Federation. World Obesity Atlas 2024. London: World Obesity Federation, 2024. Available online: https://data.worldobesity.org/publications/?cat=22. (Accessed on: 12.022025).

- Compartimentul pentru Monitorizarea si Evaluarea Infectiei HIV/SIDA in Romania. Institutul National de Boli Infectioase “Prof. Dr. Matei Bals”. Date statistice: 1 decembrie Evoluția fenomenului HIV în România 2023-2024. Available online: https://www.cnlas.ro/index.php/date-statistice. (Accessed on: 12.01.2025).

- Pantazis, N.; Porter, K.; Sabin, C. A.; Burns, F.; Touloumi, G. Antiretrovirals and obesity. Lancet HIV 2024, 11 (12), e802-e803. [CrossRef]

- Chandiwana, N.; Manne-Goehler, J.; Gaayeb, L.; Calmy, A.; Venter, W. D. F. Novel anti-obesity drugs for people with HIV. Lancet HIV 2024, 11 (8), e502-e503. [CrossRef]

- Manne-Goehler, J.; Siedner, M. J. Untangling the causal ties between antiretrovirals and obesity. Lancet HIV 2024, 11 (10), e650-e651. [CrossRef]

- European AIDS Clinical Society (EACS) Guidelines 2023, vs.12.0. Available online: https://www.eacsociety.org/media/guidelines-12.0.pdf. (Accessed on: 28.02.2025).

- Committee IR. Guidelines for data processing and analysis of the International physical activity questionnaire (IPAQ)-short and long forms, 2005. Available online: https://www.physio-pedia.com/images/c/c7/Quidelines_for_interpreting_the_IPAQ.pdf. (Accessed on: 12.01.2025).

- Kamps, B. S.; Brodt, H. R.; Staszewski, S.; Bergmann, L.; Helm, E. B. AIDS-free survival and overall survival in HIV infection: the new CDC classification system (1993) for HIV disease and AIDS. Clin Investig 1994, 72 (4), 283-287. [CrossRef]

- Gaita, L.; Timar, B.; Timar, R.; Fras, Z.; Gaita, D.; Banach, M. Lipid Disorders Management Strategies (2024) in Prediabetic and Diabetic Patients. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 219. [CrossRef]

- WHO European Regional Obesity Report 2022. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2022. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/353747/9789289057738-eng.pdf. (Accessed on: 28.02.2025).

- Institutul Național de Sănătate Publică. Ghid de prevenție pentru medicul de familie. Intervenții preventive integrate adresate stilului de viață - Alimentația. Activitatea fizică. București, 2023. Available online: https://proiect-pdp1.insp.gov.ro/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Ghidul-Alimentatia-Activitatea-fizica.pdf. (Accessed on: 12.01.2025).

- Golightly, Y. M.; Allen, K. D.; Ambrose, K. R.; Stiller, J. L.; Evenson, K. R.; Voisin, C.; Hootman, J. M.; Callahan, L. F. Physical Activity as a Vital Sign: A Systematic Review. Prev Chronic Dis 2017, 14, E123. World Health Organization. Global action plan on physical activity 2018-2030: more active people for a healthier world. World Health Organization, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Bull, F. C.; Al-Ansari, S. S.; Biddle, S.; Borodulin, K.; Buman, M. P.; Cardon, G.; Carty, C.; Chaput, J. P.; Chastin, S.; Chou, R.; et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br J Sports Med 2020, 54 (24), 1451-1462. [CrossRef]

- Centre of Excelence for Health, Immunity and Infections. Clinical risk scores. Available online: https://chip.dk/Resources/Clinical-risk-scores. (Accessed on: 12.01.2025).

- European Association of Preventive Cardiology. Heart Score. Calculate 10-year risk of fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular disease events. Available online: https://www.heartscore.org/en_GB?_gl=1*snk2xq*_gcl_au*MTg0MjAxOTYyMy4xNzQwNzQ2NjA4*_ga*NTg0NzgwNjU0LjE3NDA3NDY2MzE.*_ga_5Y189L6T14*MTc0MjExNzM2MS45LjAuMTc0MjExNzM2MS42MC4wLjA.*_ga_VPF4X3T28K*MTc0MjExNzM2MS41LjAuMTc0MjExNzM2MS4wLjAuMA. (Accessed on: 1.10.2024).

- Marc, L. G.; Wang, M. M.; Testa, M. A. Psychometric evaluation of the HIV symptom distress scale. AIDS Care 2012, 24 (11), 1432-1441. [CrossRef]

- WHO European Regional Obesity Report 2022. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2022. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/353747/9789289057738-eng.pdf. (Accessed on: 12.01.2025).

- Kozinetz, C.; Matusa, R.; Cazazu, A. The changing epidemic of pediatric hiv infection in romania. Ann Epidemiol 2000, 10 (7), 474-475. [CrossRef]

- Vrints, C.; Andreotti, F.; Koskinas, K. C.; Rossello, X.; Adamo, M.; Ainslie, J.; Banning, A. P.; Budaj, A.; Buechel, R. R.; Chiariello, G. A.; et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J 2024, 45 (36), 3415-3537. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Dhalla, N. S. The Role of Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines in the Pathogenesis of Cardiovascular Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25 (2). [CrossRef]

- Lin, G. M.; Lloyd-Jones, D. M.; Colangelo, L. A.; Lima, J. A. C.; Szklo, M.; Liu, K. Association between secondhand smoke exposure and incident heart failure: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Eur J Heart Fail 2024, 26 (2), 199-207. [CrossRef]

- Mehta, N. N.; deGoma, E.; Shapiro, M. D. IL-6 and Cardiovascular Risk: A Narrative Review. Curr Atheroscler Rep 2024, 27 (1), 12. [CrossRef]

- Schnabel, R. B.; Pecen, L.; Rzayeva, N.; Lucerna, M.; Purmah, Y.; Ojeda, F. M.; De Caterina, R.; Kirchhof, P. Symptom Burden of Atrial Fibrillation and Its Relation to Interventions and Outcome in Europe. J Am Heart Assoc 2018, 7 (11). [CrossRef]

- Jurgens, C. Y.; Lee, C. S.; Aycock, D. M.; Masterson Creber, R.; Denfeld, Q. E.; DeVon, H. A.; Evers, L. R.; Jung, M.; Pucciarelli, G.; Streur, M. M.; et al. State of the Science: The Relevance of Symptoms in Cardiovascular Disease and Research: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2022, 146 (12), e173-e184. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. S.; Newman-Toker, D. E.; Kerber, K. A.; Jahn, K.; Bertholon, P.; Waterston, J.; Lee, H.; Bisdorff, A.; Strupp, M. Vascular vertigo and dizziness: Diagnostic criteria. J Vestib Res 2022, 32 (3), 205-222. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, C. B.; Maher, C. G.; Franco, M. R.; Kamper, S. J.; Williams, C. M.; Silva, F. G.; Pinto, R. Z. Co-occurrence of Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain and Cardiovascular Diseases: A Systematic Review with Meta-analysis. Pain Med 2020, 21 (6), 1106-1121. [CrossRef]

- Ntsekhe, M.; Baker, J. V. Cardiovascular Disease Among Persons Living With HIV: New Insights Into Pathogenesis and Clinical Manifestations in a Global Context. Circulation 2023, 147 (1), 83-100. [CrossRef]

- Triant, V. A.; Lyass, A.; Hurley, L. B.; Borowsky, L. H.; Ehrbar, R. Q.; He, W.; Cheng, D.; Lo, J.; Klein, D. B.; Meigs, J. B.; et al. Cardiovascular Risk Estimation Is Suboptimal in People With HIV. J Am Heart Assoc 2024, 13 (10), e029228. [CrossRef]

- Arbune M. Premature aging and cardiovascular diseases related to HIV infection. Romanian Archives of Microbiology and Immunology 2021; 80(4): 342-348. [CrossRef]

- Obare, L. M.; Temu, T.; Mallal, S. A.; Wanjalla, C. N. Inflammation in HIV and Its Impact on Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease. Circ Res 2024, 134 (11), 1515-1545. [CrossRef]

- Savinelli, S.; Newman, E.; Mallon, P. W. G. Metabolic Complications Associated with Use of Integrase Strand Transfer Inhibitors (InSTI) for the Treatment of HIV-1 Infection: Focus on Weight Changes, Lipids, Glucose and Bone Metabolism. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2024, 21 (6), 293-308. [CrossRef]

- Corti, N.; Menzaghi, B.; Orofino, G.; Guastavigna, M.; Lagi, F.; Di Biagio, A.; Taramasso, L.; De Socio, G. V.; Molteni, C.; Madeddu, G.; et al. Risk of Cardiovascular Events in People with HIV (PWH) Treated with Integrase Strand-Transfer Inhibitors: The Debate Is Not Over; Results of the SCOLTA Study. Viruses 2024, 16 (4). [CrossRef]

- Crane, H. M.; Nance, R. M.; Avoundjian, T.; Harding, B. N.; Whitney, B. M.; Chow, F. C.; Becker, K. J.; Marra, C. M.; Zunt, J. R.; Ho, E. L.; et al. Types of Stroke Among People Living With HIV in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2021, 86 (5), 568-578. [CrossRef]

- Tükenmez Tigen, E.; Gökengin, D.; Özkan Özdemir, H.; Akalın, H.; Kaya, B.; Deveci, A.; İnan, A.; İnan, D.; Altunsoy, A.; Özel, A. S.; et al. Prevalence of Cardiovascular Disease and Comparison of Risk Category Predictions of Systemic Coronary Risk Evaluation Score-2 and 4 Other Cardiovascular Disease Risk Assessment Tools Among People Living with Human Immunodefficiency Virus in Türkiye. Anatol J Cardiol 2024, 28 (12), 584-591. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).