1. Introduction

Bladder cancer (BC) is the second most common genitourinary malignancy in the world, the sixth most common cancer in men and the 17th most common cancer in women [

1]. Muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) represents approximately 20% of newly diagnosed cases of BC [

2], and is characterized by an overall poor prognosis with a 5-year overall survival (OS) of ~50% [

3]. Although radical cystectomy (RC) remains the most effective treatment for MIBC, a half of MIBC treated with RC eventually recur with distant metastases and fatal outcome [

2].

Previous studies have demonstrated that neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) followed by RC increases the probability of downstaging BC prior to cystectomy and is associated with improved survival [

3,

4]. In addition, a recent meta-analysis of 15 randomized NAC clinical trials noted an improved cancer-specific survival by 5-10% compared to no NAC [

5]. With the accumulating evidence, currently AUA/ASCO/SUO Guideline for non-metastatic MIBC strongly recommends offering cisplatin-based NAC to eligible RC patients [

6]. However, NAC has the potential risk that a segment of patients do not respond, suffer treatment toxicity, and experience critical surgical delays [

7]. AUA/ASCO/SUO Guideline noted that there are no validated predictive factors or clinical characteristics (including age) associated with an increased or decreased probability of response and benefit using cisplatin-based NAC. Therefore, more precise stratification of patients with indications for NAC is urgently needed to identify patients more likely to respond, and transition those who are likely to fail to other strategies.

Our prior studies have identified a panel of 10 urine-based protein biomarkers including Alpha-1 Antitrypsin (A1AT), angiogenin (ANG), Apolipoprotein E (APOE), Carbonic Anhydrase 9 (CA9), Interleukin-8 (IL8), matrix metalloproteinases 9 (MMP9), MMP10, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI1), syndecan-1 (SDC1), and vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA), which are significantly associated with BC [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Previous studies using immunostaining have shown that these 10 protein biomarkers are highly expressed in neoplastic urothelium compared to benign urothelium, and higher levels of these biomarkers are associated with more aggressive BC [

12]. Additionally, we noted that mRNA expression of these 10 biomarkers to have prognostic power with a large gene expression cohort from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) [

13]. Taken together, these findings suggest that the gene expression profile of our BC-associated diagnostic signature may also have predictive value for determining response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC). This concept is further supported by emerging studies demonstrating that molecular biomarkers and gene expression signatures can inform NAC sensitivity and guide personalized treatment strategies in muscle-invasive bladder cancer [

14,

15,

16,

17]. However, although several predictive gene expression signatures have been proposed, none have yet been widely adopted into clinical practice, largely due to issues with reproducibility, lack of analytical validation, and limited feasibility for routine clinical use. Furthermore, most existing signatures rely on tumor tissue obtained from cystectomy specimens, rather than pre-treatment biopsies or non-invasive approaches. Our multiplex qPCR-array platform, designed to assess a focused panel of analytically validated biomarkers, offers the potential for a clinically practical, minimally invasive, and reproducible tool to predict NAC response prior to definitive surgery. Nevertheless, a rigorous and validated assessment of gene expression levels within this biomarker panel must first be established.

In this study, we developed a custom multiplex qPCR array-based assay to evaluate the mRNA expression of our bladder cancer associated diagnostic signature and analytically validated its performance using FFPE of surgical specimens obtained from MIBC based on the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines [

18]. The main objectives of this strategy were to optimize the components of the assay into an integrated workflow and to develop a standard operating protocol of sample collection, processing, assay run, quality assurance, quality control, and data generation. Here, we provide an overview of the analytical performance of the multiplex qPCR array-based assay (Nexus-Dx™, Nonagen Bioscience, Los Angeles, CA).

2. Results

2.1. Preanalytical Validation

2.1.1. RNA Stability

For RNA analysis, FF tissues are considered as the “gold standard” in basic science research. In the real world, FFPE samples are widely used for biological analysis because of their more pristine histology which can lead to more accurate diagnoses. However, RNA derived from FFPE tends to be degraded, chemically modified, and cross-linked due to fixation and archiving methods, affecting the performance of the molecular analysis such as RNA sequence or qPCR [

19]. We assessed the effect of FFPE processing compared to FF on the detection of the bladder cancer associated diagnostic signature using qPCR array assay.

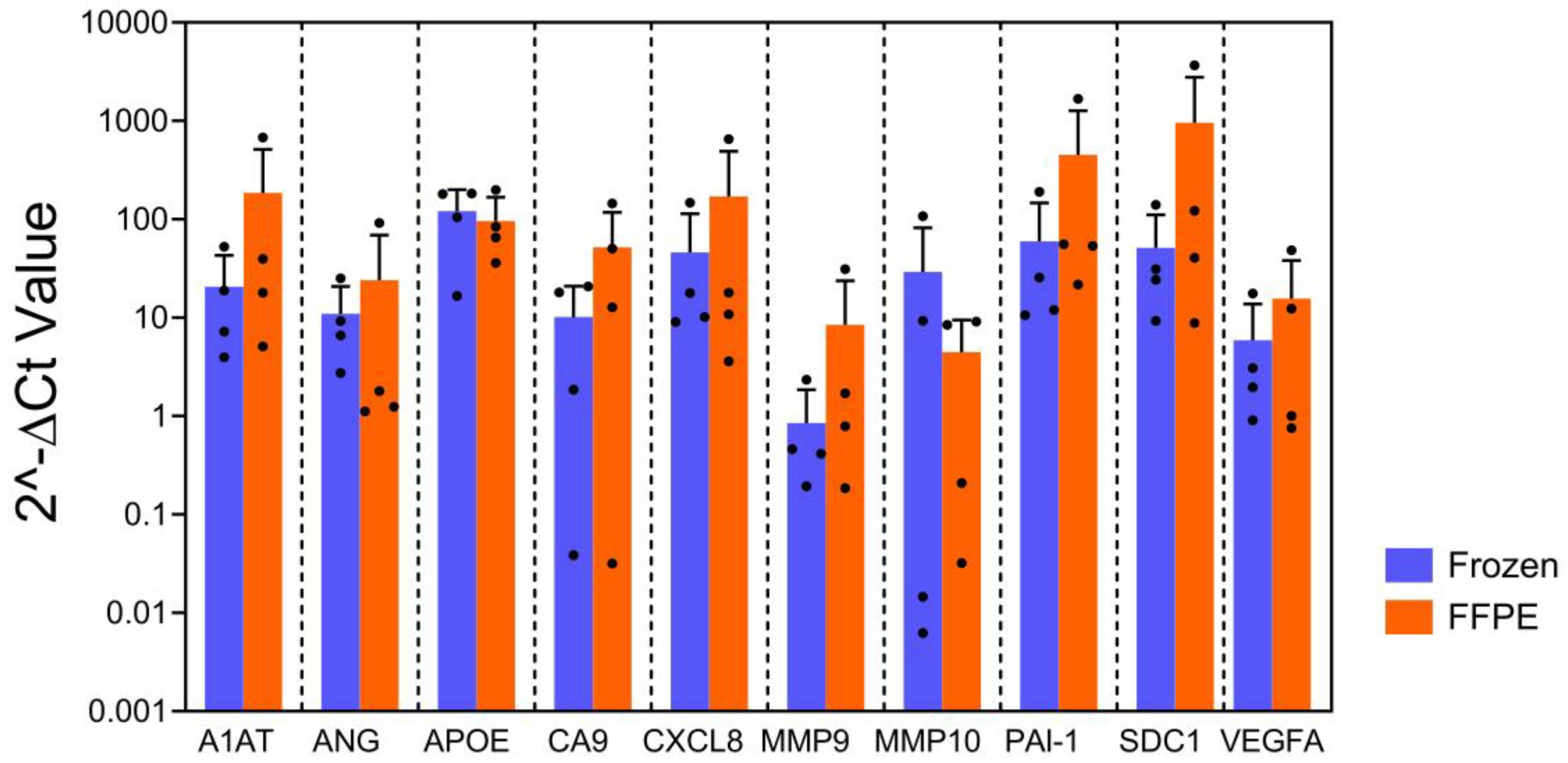

First, 4 FF tissues were bisected. One piece was stored at -80°C and the other was processed to generate FFPE blocks according to College of American Pathologists Guidelines [

20]. For the FFPE blocks, the bisected FF tissues were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 24 hours and immersing them in 70% ethanol. Then, they were processed in a Leica ASP300 tissue processor (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL) within 7 days. Next, we compared qPCR data using RNA isolated from FFPE blocks with matched FF tissues as controls. No statistically significant difference was found between the FFPE and the FF tissues on gene expression pattern (

Figure 1; p=0.13). The finding demonstrated that qPCR profiling on archival FFPE blocks can generate the reliable data for assessing RNA expression of the bladder cancer associated diagnostic signature.

Bar graph shows gene expression level, indicating the expression of each gene derived frozen tissue on left and FFPE on right in same color bar per gene. No difference was observed in gene expression patterns between frozen tissue and paired FFPE (p=0.13, mixed model regression). Error bars represent SD.

2.1.2. Specimen Format

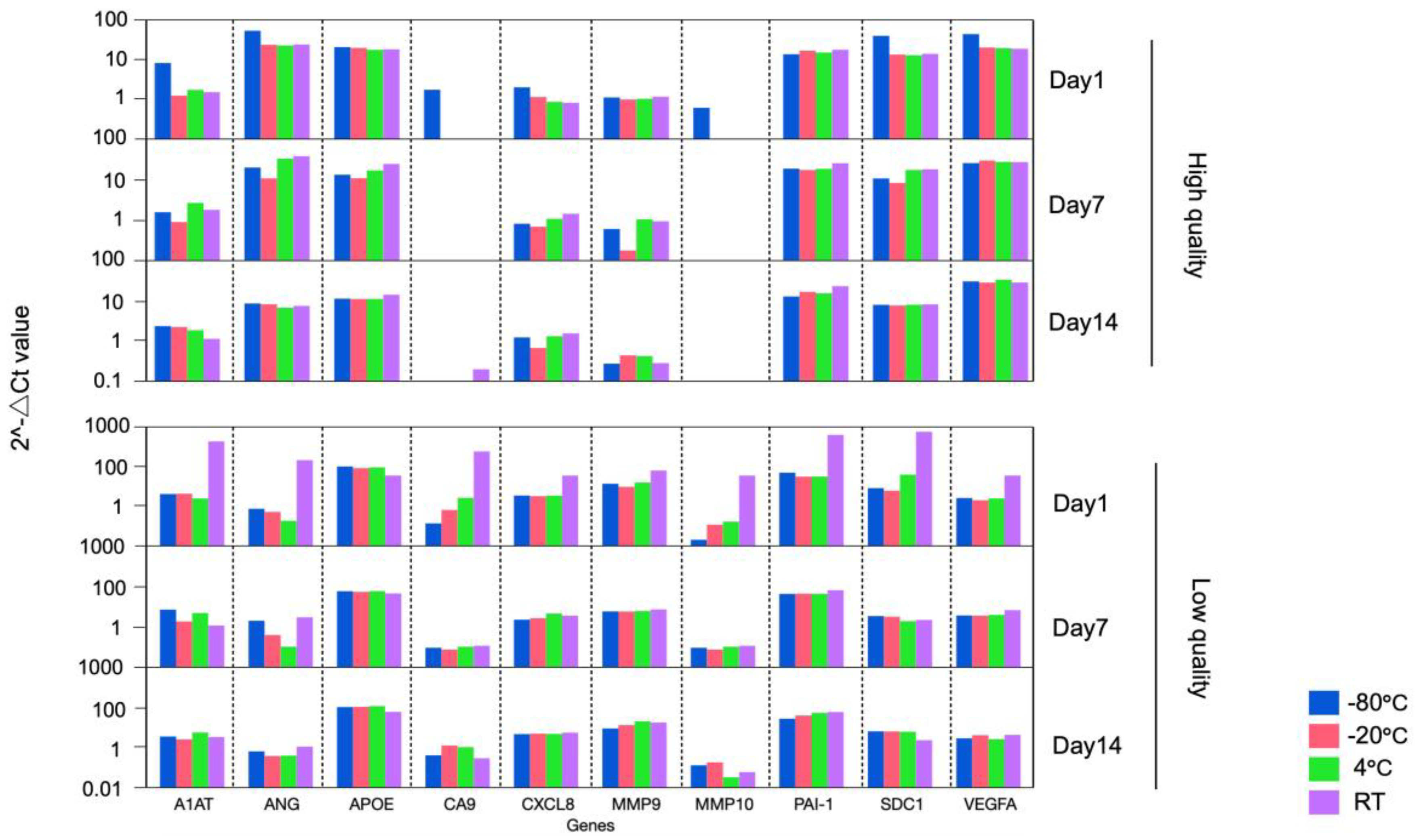

FFPE specimens are often received as unstained slides in an actual clinical situation. Transport and storage environments can adversely effect samples leading to degradation of RNA, which could alter experimental results. To address this issue, we compared the expression pattern of the BC associated diagnostic signature among the FFPE curl stored at various temperatures and durations as follows. Two FFPE blocks (High quality FFPE containing high % viable cells and low quality FFPE containing low % viable cells) were cut as 4 curls of 10 μm per condition and stored at room temperature (RT), 4°C, -20°C, and -80°C. RNA was extracted on 1, 7, and 14 days of storage, cDNA was immediately synthesized. Finally, PCR array assay was performed, and the bladder cancer associated diagnostic expression profiles were compared.

This study revealed that, for all conditions, a similar gene expression pattern was demonstrated across any storage temperature and periods, except for FFPE blocks processed at day 1 and stored at RT (

Figure 2,

Table 1). The result supports that the quality of the RNA in the assay can be ensured if the FFPE sample is stored at or below 4°C and performed within 2 weeks of its sectioning after the from blocks.

Day indicates the date when RNA was extracted from FFPE curl storage at RT, 4°C, -20°C, and -80°C. One high quality and one low quality FFPE were used.

2.2. Analytical Validation

2.2.1. RNA Input

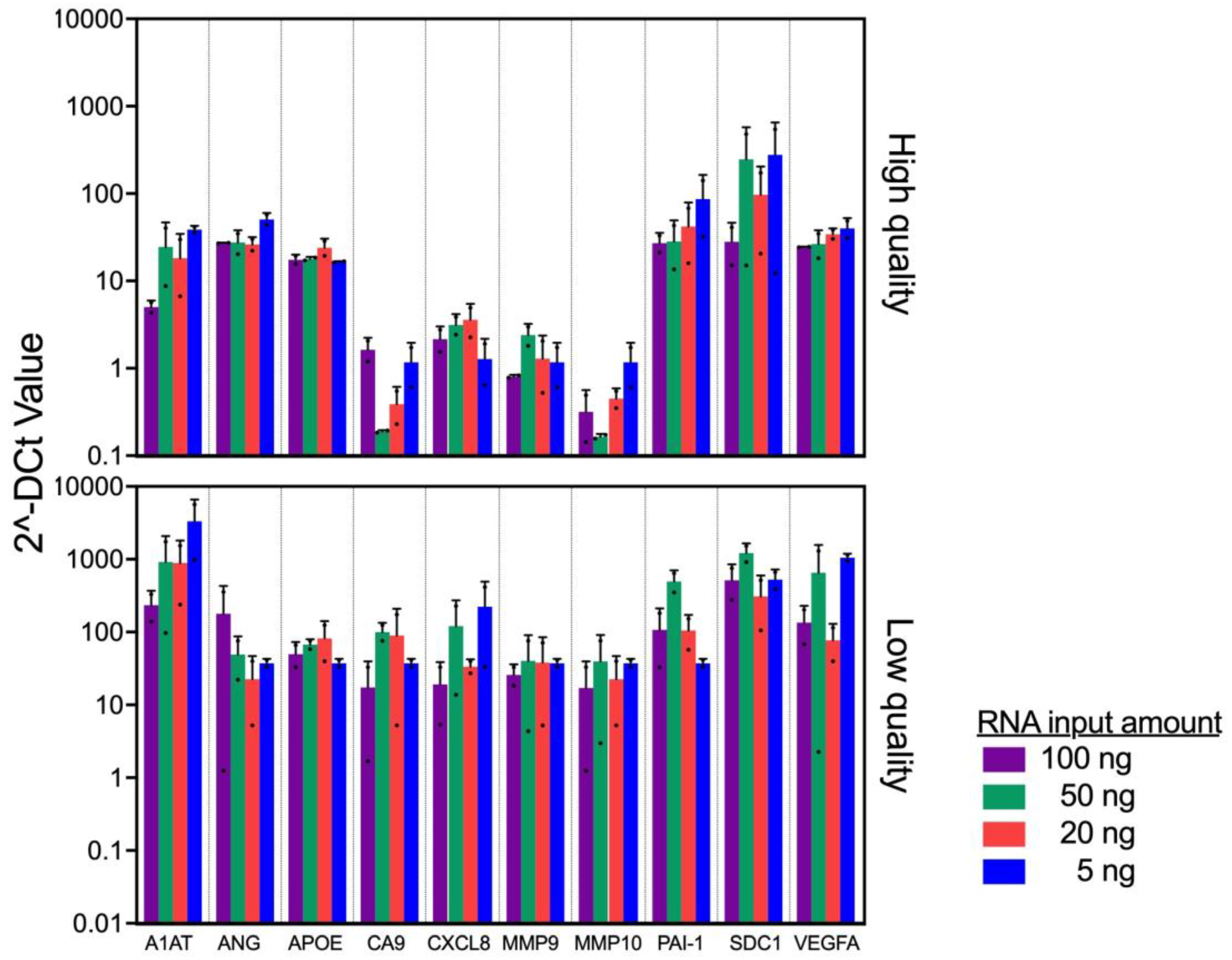

In clinical practice, it is expected that slight discrepancies in the amount of RNA recovered will occur due to variations in tissue size, fixation process, FFPE storage methods, and age of FFPE blocks. To evaluate the minimum amount of RNA input to accurately profile the bladder cancer associated diagnostic signature gene expression, we used 2 FFPEs with high (>80%) and 2 FFPEs with low (<25%) % viable cells to evaluate the consistency of the gene expression among various input amounts.

First, we obtained high quality (DV200 of 29 and 33%) and quantity (concentrations of 173 and 297 ng/μl) of RNA from high quality FFPE blocks, while RNA quality and quantity from low quality FFPE blocks are low as DV200 of 15 and 25%, and concentrations of 23 and 47 ng/μl, respectively. With the RNA samples, we evaluated the gene expression pattern. The similarity of gene expression pattern was observed among high quality FFPE blocks across all input amount of RNA (5-100 ng, p=0.27). On the other hand, we noted a discrepancy in the expression patten from the low quality FFPE blocks (

Figure 3, p=0.025). Specifically, the gene expression from the low quality FFPE blocks demonstrated higher ΔCt values. Because we added the same amount of RNA, the viable RNA amount (%DV200 x RNA amount) should not be too different. Thus, we consider that the difference in ΔCt values between high and low quality FFPE blocks may be due to tumor status, such as grade, stage, and/or aggressiveness. Taken together, the results suggest that the assay was robust enough when RNA quality/quantity are above DV200 of 15% and 5 ng.

Two samples on the top have highest quality FFPE and the other 2 samples on the bottom have lowest quality FFPE among current cohort were used. Significant difference in overall expression levels between high- and low-quality p<0.01, mixed model regression. Error bars represent SD.

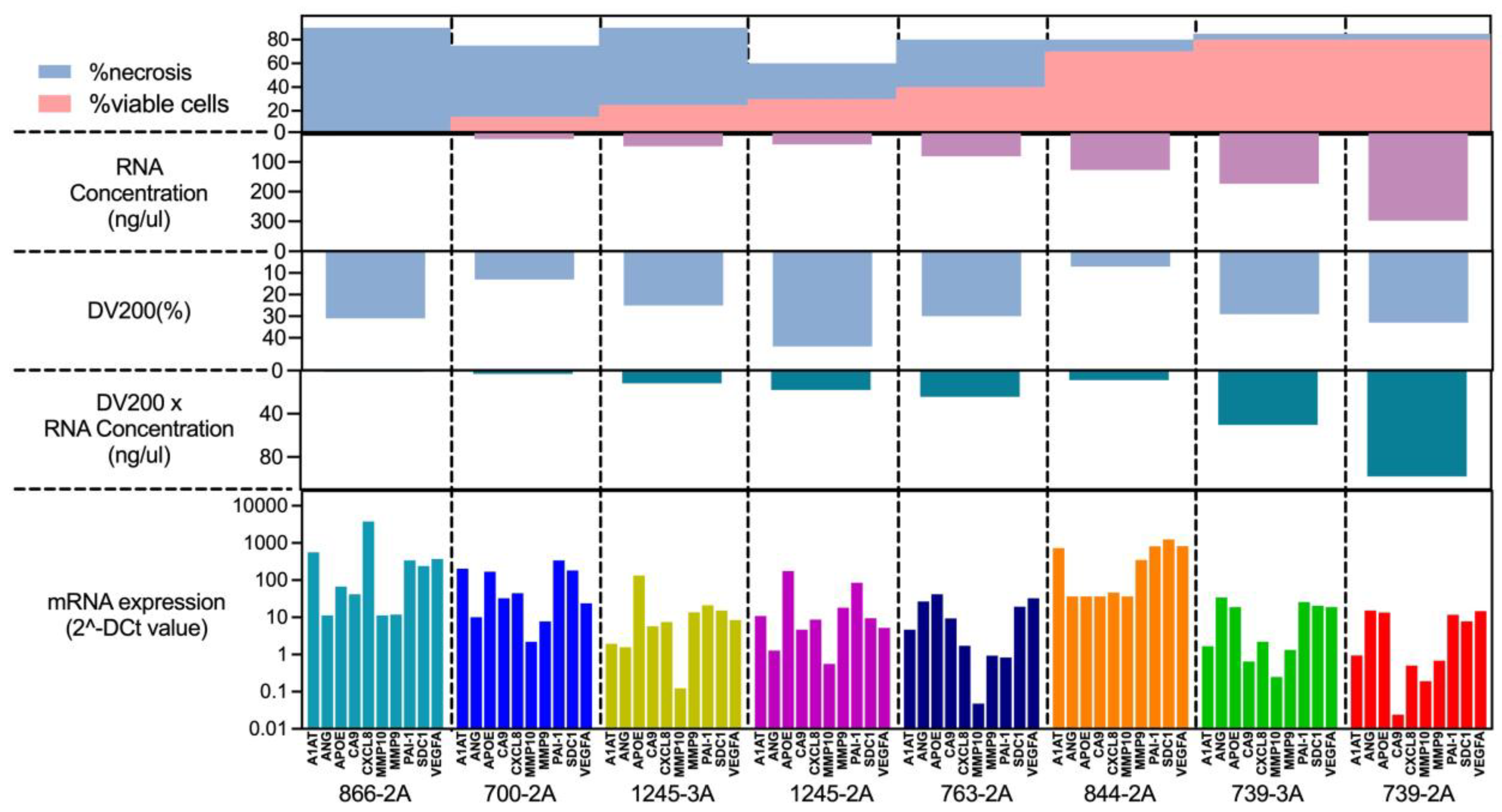

2.2.2. Tissue Quality

The proportion of necrosis can vary widely not only between different cases but also within the same case, which can affect the reliability of gene expression results. First, we observed a tendency for the proportion of necrosis to be inversely correlated with the yield of extracted RNA (

Figure 4). On the other hand, the RNA quality (DV200) evaluated by Bioanalyzer was not correlated with the proportion of necrosis, suggesting that the RNA quality may be due to other factors, such as tissue size, fixation process, FFPE storage methods, and age of FFPE blocks. We also observed consistency in gene expression in the pair of FFPE blocks within the same case with different necrosis rates, which are the pairs of 739-3A/739-2A and 1245-3A/1245-2A. Collectively, these results suggested that our assay could tolerate the presence of tissue necrosis. Though, the sample with 90% of necrosis showed the gene expression of the bladder cancer associated diagnostic signature as well as other samples with low proportion of necrosis, the best performance is seen when there is <50% necrosis present.

Top of the graph shows the proportion of necrosis as blue area and viable cells as pink area. The green graph bars on the middle shows RNA quality as DV200 (%) multiplied with RNA concentration suggesting the amount of RNA which is available for analyzation. There is an association of the proportion of necrosis and RNA quality. The bottom of the graph indicating that gene expression is still detectable even in the sample with highest proportion of necrosis.

2.3. Reproducibility

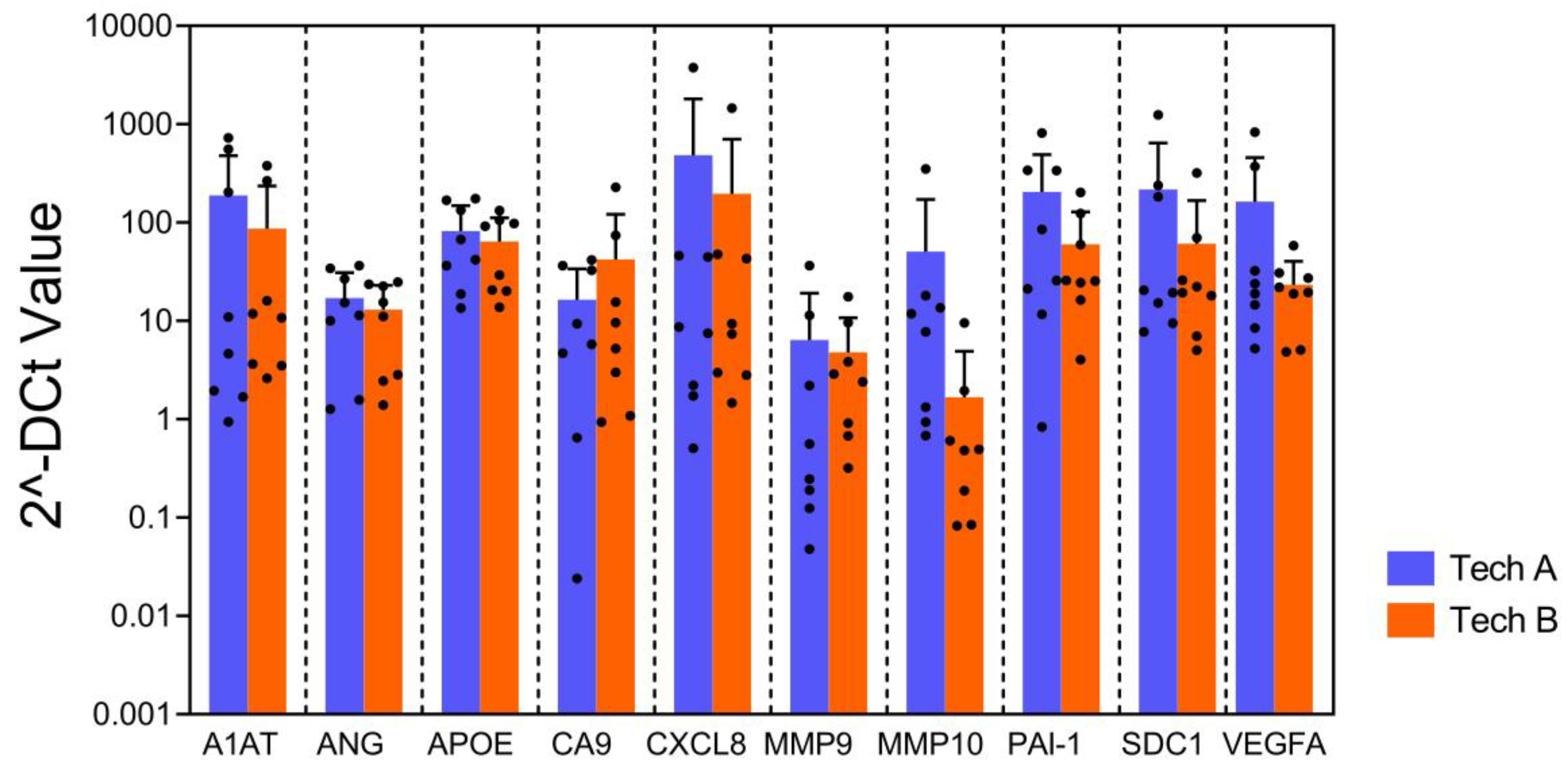

To evaluate the reproducibility and robustness of this assay, the bladder cancer associated diagnostic signature gene expression pattern from 2 independent technicians using the same 8 FFPE samples were compared. Multiplex qPCR assays were performed on all samples using a single plate on different dates by each technician. The results from two technicians demonstrated strong correlation (R

2=0.82), suggesting high reproducibility of the gene expression pattern (

Figure 5). This assists in ensuring high accuracy of the assay despite variations in experimental conditions and days within an actual clinical setting.

No difference was observed in gene expression levels obtained from the qPCR array for all genes across two different technicians (p=0.051, mixed model regression). Error bars represent SD

3. Discussion

Currently, NAC followed by RC is the gold standard treatment for the patients with locally advanced BC. Patients with NAC failure generally have a poorer prognosis when compared to those who achieve significant tumor downstaging [

21]. Because there are no validated predictive factors or clinical characteristics associated with an increased or decreased probability of NAC response, there is an urgent unmet need for effective and accurate test that predicts response to NAC. In this study, we outlined the development and analytical validation of a qPCR array-based assay that may predict clinical response to cisplatin-based NAC. The entire process including specimen collection, processing, qPCR, and the data analysis was evaluated to determine robustness across numerous sample features, including histologic status. All of these parameters passed our internal quality assurance plan. Of note, the intent of the qPCR array-based diagnostic assay is to measure the relative abundance of mRNA associated with a bladder cancer associated diagnostic signature that we have reported [

13].

The overall validation workflow for the assay utilized a series of samples prepared in different conditions to determine robustness, precision, accuracy, and potential confounders. From this evaluation, multiple quality controls (QCs) obtained from the manufacturer, such as gDNA, PCR, and RT, were included in the PCR array plate and they will serve as daily QC parameters. Specifically, the QC measures for gDNA, PCR, and RT were used to monitor genomic DNA contamination, PCR quality, and reverse transcription quality, respectively. The bioinformatics pipeline ensures quick data analysis, delivering results in less than five days. The analytical validation studies reported here demonstrated that ideal specimen characteristics minimally affect the qPCR array-based diagnostic test. First, we confirm that the results from FFPE RNA showed equivalent to RNA isolated from FF tissues. Then we evaluated the effect of storage condition after sectioning FFPE blocks. The results show that assay accuracy is maintained when samples are stored at or below 4°C and tested within 2 weeks after sectioning curls from FFPE blocks. Next, we evaluated the effects of quality and amount of RNA samples on the test results. To evaluate the minimum amount of RNA input, we employed RNA samples with high and low quality. The results suggest the assay can handle as low as DV200 of 15% and 5 ng, while the ideal DV200 is more than 30%. Interestingly, the amount of RNA was associated with % of viable tumor, while the quality of RNA (% DV200) was not. Therefore, the specimens should not have more than 80% necrosis present to obtain sufficient amount of RNA for qPCR array test. Finally, we demonstrated consistent gene expression patterns by different technicians on different days, thus attesting to the assay’s reproducibility.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design

Assay performance was assessed by studying various pre-analytical and analytical factors, focusing on reproducibility, sensitivity, accuracy, and specificity using MIBC surgical specimens from patients before NAC.

4.2. Specimens

To evaluate the analytical performance of the assay, we employed 8 Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) specimens and 4 fresh-frozen (FF) tissues from advanced BC patients stored in the Department of Pathology at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. This study was approved by Cedars-Sinai IRB (IRB# STUDY00000451) according to institutional policy for human subject research. Specimens included the surgical specimen of transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT) and the RC performed from 2016 to 2020.

4.3. RNA Extraction

4 FFPE curls of 10μm thickness were cut per FFPE block and total RNA was extracted using AllPrep DNA/RNA FFPE Kit (Cat# 80234, Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions after the deparaffinization steps using xylene. RNA was eluted in 30 μL of water and their yield and quality were evaluated by BioAnalyzer (RNA Pico or Nano, depending on RNA yield) and expressed as DV200, which evaluates the percentage of fragments of >200 nucleotides.

4.4. cDNA Synthesis

cDNA synthesis was conducted using 5μL of RNA solution and Prelude One-Step PreAmp master mix (Cat# 638554, Takara Bio Inc., Japan), with 5μL of the primer pool for 13 genes including 10 biomarkers genes (ANG, APOE, A1AT, CA9, IL8, MMP9, MMP10, PAI1, SDC1, and VEGFA) and the 3 reference genes (TBP, ATP5E and CLTC) for normalization of Quantitative PCR (qPCR) data as well as RT control primer (BIO-RAD, Cat #10025695). The preamplification assay was performed at cycling conditions of 42°C 10 min, 95°C 2 min, 14 cycles of 95°C 10 sec and 60°C 4 min, and 4°C hold.

4.5. Primer and PCR array Design

Primers for 10 biomarkers genes and 3 reference genes were designed using Primer-BLAST tools according to the desired gene target. The sequences for the target genes were obtained from GenBank within NCBI. Exon/intron selection was not carried out. Some candidate primers obtained then underwent further selection such as selection in forward and reverse primer temperatures <5°C, % GC values at 40-60% and no self-3-complementarity values. The specificity of this primer was tested using Standard Nucleotide BLAST. The custom PCR array was designed on Bio-Rad PrimePCR Tools and the array in a 384-well plate was produced by Bio-Rad.

4.6. Real-Time Quantitative PCR Array

The RT-qPCR analyses were performed in the Applied Biosystems QuantStudio 6 Flex Real-Time PCR system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) using PowerUP SYBR Green master mix for qPCR (Thermo Fisher Scientific). One reaction (10 µl total per well) contained: 5 µl of PCR master mix, 1 µl of cDNA template and each primer dried in well. The PCR program was set as follows: 95°C for 10 sec (denaturation), followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 5 sec, annealing and extension at 60°C for 30 sec, followed by melting curve read from 60°C to 95°C with increment 0.2°C every 10 sec.

4.7. Histologic Evaluation of H&E

Two board-certified anatomic pathologists (O.T.M.C. & D.J.L.) reviewed H&E slides from each FFPE block to evaluate histology and document the proportion of necrotic tissue.

4.8. Statistical Analysis

We calculated RNA expression level based on 2^-ΔCt as described previously [

22]. All statistical testing of differences in log-concentration RNA expression levels were analyzed with mixed model regression modeling with the fixed effect of each processing factor to be tested, with the random effects of patient and genes of interest. Differences were considered significant where p<0.05. Data analysis performed using SAS v9.4 software.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this analytical validation study identified optimal sample preparation and storage conditions for the multiplex qPCR array-based assay, ensuring the integrity and reliability of results across varying conditions. Additionally, we determined the minimum quality and quantity of samples necessary for accurate and reproducible testing. These findings are critical for standardizing the use of the multiplex qPCR array-based assay in clinical settings and maximizing its diagnostic performance. With these optimized parameters in place, the multiplex qPCR array-based assay is well-positioned for further clinical validation and potential widespread use in BC. Future studies will be needed to confirm these findings in diverse patient populations and real-world conditions.

Supplementary Materials

No supplementary data is included in this manuscript.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.J.R. and H.F.; methodology, C.J.R. and H.F.; formal analysis, T.S., C.B., O.T.M.C., D.J.L., C.J.R., W.H., and H.F.; investigation, T.S., S.T., C.J.R., and H.F.; resources, D.J.L.; data curation, T.S., S.T., K.M., F.A., C.B., D.J.L., O.T.M.C., and H.F.; writing—original draft preparation, T.S.; writing—review and editing, C.J.R. and H.F.; visualization, T.S. and C.B.; supervision, C.J.R. and H.F.; project administration, C.J.R. and H.F.; funding acquisition, C.J.R. and H.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by research grants UH3 CA271377 (CJR), R01 CA277810 (HF/CJR), U54 CA274375-01 (HF/CJR) and R01 CA198887 (CJR).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study received approval and a waiver of consent to use previously banked de-identified urine samples from the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center Institutional Review Board, Los Angeles, CA (IRB # STUDY00000451). Study performance complied with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The anonymized datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Yunfeng Dai with University of South Florida (Tampa, FL) for analytical assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

Wayne Hogrefe and Charles J. Rosser are officers of Nonagen bioscience Corp. All other authors report no potential conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BC |

Bladder cancer |

| MIBC |

muscle-invasive bladder cancer |

| NAC |

neoadjuvant chemotherapy |

| FFPE |

formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded |

| FF |

fresh-frozen |

| OS |

overall survival |

| RC |

radical cystectomy |

| TCGA |

The Cancer Genome Atlas |

| GEO |

Gene Expression Omnibus |

| TURBT |

Transurethral resection of bladder tumor |

| qPCR |

Quantitative PCR |

| RT |

room temperature |

References

- Jubber, I.; Ong, S.; Bukavina, L.; Black, P.C.; Comperat, E.; Kamat, A.M.; Kiemeney, L.; Lawrentschuk, N.; Lerner, S.P.; Meeks, J.J.; et al. Epidemiology of Bladder Cancer in 2023: A Systematic Review of Risk Factors. Eur Urol 2023, 84, 176–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, V.G.; Oh, W.K.; Galsky, M.D. Treatment of muscle-invasive and advanced bladder cancer in 2020. CA Cancer J Clin 2020, 70, 404–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grossman, H.B.; Natale, R.B.; Tangen, C.M.; Speights, V.O.; Vogelzang, N.J.; Trump, D.L.; deVere White, R.W.; Sarosdy, M.F.; Wood, D.P., Jr.; Raghavan, D.; et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus cystectomy compared with cystectomy alone for locally advanced bladder cancer. N Engl J Med 2003, 349, 859–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neoadjuvant cisplatin, methotrexate, and vinblastine chemotherapy for muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a randomised controlled trial. International collaboration of trialists. Lancet 1999, 354, 533–540. [CrossRef]

- Yin, M.; Joshi, M.; Meijer, R.P.; Glantz, M.; Holder, S.; Harvey, H.A.; Kaag, M.; Fransen van de Putte, E.E.; Horenblas, S.; Drabick, J.J. Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy for Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer: A Systematic Review and Two-Step Meta-Analysis. Oncologist 2016, 21, 708–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holzbeierlein, J.; Bixler, B.R.; Buckley, D.I.; Chang, S.S.; Holmes, R.S.; James, A.C.; Kirkby, E.; McKiernan, J.M.; Schuckman, A. Treatment of Non-Metastatic Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer: AUA/ASCO/SUO Guideline (2017; Amended 2020, 2024). J Urol 2024, 212, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Advanced Bladder Cancer Meta-analysis, C. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in invasive bladder cancer: update of a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data advanced bladder cancer (ABC) meta-analysis collaboration. Eur Urol 2005, 48, 202–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urquidi, V.; Goodison, S.; Cai, Y.; Sun, Y.; Rosser, C.J. A candidate molecular biomarker panel for the detection of bladder cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2012, 21, 2149–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, N.; Feng, S.; Shedden, K.; Xie, X.; Liu, Y.; Rosser, C.J.; Lubman, D.M.; Goodison, S. Urinary glycoprotein biomarker discovery for bladder cancer detection using LC/MS-MS and label-free quantification. Clin Cancer Res 2011, 17, 3349–3359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosser, C.J.; Liu, L.; Sun, Y.; Villicana, P.; McCullers, M.; Porvasnik, S.; Young, P.R.; Parker, A.S.; Goodison, S. Bladder cancer-associated gene expression signatures identified by profiling of exfoliated urothelia. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2009, 18, 444–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kreunin, P.; Zhao, J.; Rosser, C.; Urquidi, V.; Lubman, D.M.; Goodison, S. Bladder cancer associated glycoprotein signatures revealed by urinary proteomic profiling. J Proteome Res 2007, 6, 2631–2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Gomes-Giacoia, E.; Dai, Y.; Lawton, A.; Miyake, M.; Furuya, H.; Goodison, S.; Rosser, C.J. Validation and clinicopathologic associations of a urine-based bladder cancer biomarker signature. Diagn Pathol 2014, 9, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, R.; Pagano, I.; Sun, Y.; Murakami, K.; Goodison, S.; Vairavan, R.; Tahsin, M.; Black, P.C.; Rosser, C.J.; Furuya, H. A Diagnostic Gene Expression Signature for Bladder Cancer Can Stratify Cases into Prescribed Molecular Subtypes and Predict Outcome. Diagnostics (Basel) 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tripathi, N.; Fortuna, G.G.; Gebrael, G.; Dal, E.; Mathew Thomas, V.; Gupta, S.; Swami, U. Predictors of response to neoadjuvant therapy in urothelial cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2024, 194, 104236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitrov, G.; Mangaldzhiev, R.; Slavov, C.; Popov, E. Contemporary Molecular Markers for Predicting Systemic Treatment Response in Urothelial Bladder Cancer: A Narrative Review. Cancers (Basel) 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laviana, A.A.; Schiftan, E.G.; Mashni, J.W.; Large, M.C.; Kaimakliotis, H.Z.; Nolte, D.D.; Turek, J.J.; An, R.; Morgan, T.A.; Chang, S.S. Biodynamic prediction of neoadjuvant chemotherapy response: Results from a prospective multicenter study of predictive accuracy among muscle-invasive bladder cancer patients. Urol Oncol 2023, 41, 295 e299–295 e217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, N.; Shih, A.J.; Shah, P.; Yaskiv, O.; Khalili, H.; Liew, A.; Lee, A.T.; Zhu, X.H. Predictive molecular biomarkers for determining neoadjuvant chemosensitivity in muscle invasive bladder cancer. Oncotarget 2022, 13, 1188–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- (CLSI), C.a.L.S.I. Collection, Transport, Preparation, and Storage of Specimens for Molecular Methods; Approved Guideline.; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: 2005.

- Guo, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhao, S.; Ye, F.; Su, Y.; Clark, T.; Sheng, Q.; Lehmann, B.; Shu, X.O.; Cai, Q. RNA Sequencing of Formalin-Fixed, Paraffin-Embedded Specimens for Gene Expression Quantification and Data Mining. Int J Genomics 2016, 2016, 9837310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CAP Guidelines. Available online: https://www.cap.org/protocols-and-guidelines/cap-guidelines (accessed on December 3).

- Kaczmarek, K.; Malkiewicz, B.; Skonieczna-Zydecka, K.; Leminski, A. Influence of Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy on Survival Outcomes of Radical Cystectomy in Pathologically Proven Positive and Negative Lymph Nodes. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmittgen, T.D.; Livak, K.J. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc 2008, 3, 1101–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).