Introduction

Despite decades of safe use, hypotension after epidural labor analgesia (ELA) remains the most common complication and is experienced by about 1 of every 5 patients receiving ELA. Hypotension has safety ramifications to both mother and fetus and results in, at its mildest, maternal lightheadedness and nausea, and at its most severe, fetal acidemia and difficulties with fetal-to-neonatal transition. These safety concerns make early detection, prevention, and treatment of ELA-associated hypotension a critical component for patient safety on labor and delivery units worldwide.

As digital technologies transform perioperative medicine, there is growing interest in leveraging predictive analytics and real-time physiologic monitoring to support clinical decision-making. Tools like the Hypotension Prediction Index (HPI) exemplify this shift, offering clinicians early warning of hemodynamic instability based on continuous arterial waveform analysis. In dynamic labor and delivery environments, where maternal physiology evolves rapidly and treatment windows are narrow, such digital decision support systems may facilitate earlier, more targeted interventions to protect both maternal and fetal well-being.

Currently, conventional monitoring involves intermittent non-invasive blood pressure checks to detect and treat hypotension. The current American Society of Anesthesiologists Guidelines on Obstetric Anesthesia Practice [

1] recommend monitoring for hypotension, with most practices using non-invasive cuff measures, typically expected every 5-15 minutes. However, intermittent monitoring may result in delays in recognition and treatment of low blood pressure [

2]. Delays in treating epidural anesthesia-associated hypotension can result in inadequate maternal-fetal perfusion [

2]. Further, causes of hypotension after neuraxial in obstetric patients are primarily driven by reductions in systemic vascular resistance (SVR) [

3]. Early detection of ELA-associated hypotension is critically needed to facilitate earlier treatments with vasopressors, typically consisting of either ephedrine or phenylephrine, to prevent hypotension related morbidities. Further, tailored treatment to maternal hemodynamics – a tactic made possible using HPI – is important because changes in systemic vascular resistance (SVR) and cardiac output (CO) during labor is known to impede uterine blood flow and fetal oxygenation. These changes can lead to fetal acidemia and distress, which can then lead to preventable and emergent birth interventions.

Our proposed solution involves using the hypotension prediction index (HPI, ClearSight

TM, Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, USA) to reduce time-to-treatment of epidural labor analgesia (ELA)-associated hypotension and to improve maternal hemodynamics, resulting in improved fetal perfusion. The HPI algorithm on ClearSight

TM is a machine-learning-based decision support tool that analyzes arterial waveform features to predict hypotension, defined by mean arterial pressure (MAP) < 65 mmHg for at least 1 minute [

4]. The index ranges 0 to 100 with higher numbers reflecting a higher likelihood of subsequent hypotension. HPI has 92% sensitivity and specificity for predicting hypotension 5 minutes in advance, sensitivity 89% and specificity 90% for 10 minutes in advance and 88% and 87% for 15 minutes in advance [

4]. The sensitivity and specificity of HPI to accurately predict hypotension has also been validated with conventional invasive and non-invasive arterial waveforms, in both pregnant and non-pregnant cohorts [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. Other studies have similarly demonstrated the effectiveness of HPI in predicting hypotension in perioperative settings [

10,

11,

12]. The algorithm is FDA approved for sale in Europe and the United States. To our knowledge, no study to date has rigorously assessed the utility of HPI in ELA compared to conventional monitoring, for the benefits of reduced time-to-treatment of ELA-associated hypotension.

Although prior studies have evaluated the use of ClearSight™ and HPI in obstetric settings and primarily under cesarean delivery, none have specifically focused on implementation-specific (patient- and clinician-specific) outcomes in a vaginal birth context under neuraxial analgesia. This study was designed to assess real-world workflow integration, to evaluate clinician and patient perceptions of the monitoring approach and generate preliminary estimates of treatment effect size to inform future research.

As healthcare systems embrace predictive algorithms and automated monitoring, integrating these tools into dynamic labor workflows requires evidence not only of efficacy, but of real-world feasibility and user acceptance. The purpose of this randomized controlled trial was to evaluate the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of HPI-guided management compared to conventional monitoring by assessing time-to-treatment of hypotension in healthy pregnant individuals receiving epidural labor analgesia (ELA).

Methods

Study Design and Population

This was a prospective single center randomized controlled trial designed to assess feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy (Clinical Trials .Gov information: NCT05906368, registered 31/07/2024). All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations and all protocols were approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board (STUDY23030009). Written informed consent was obtained from subjects. Subjects were eligible if they were admitted to the hospital for labor and delivery, pregnant at term gestation, and receiving epidural labor analgesia (ELA). Exclusion criteria included non-reassuring fetal tracing at the time of ELA request, unintentional dural puncture, contraindications to ELA, significant cardiac arrhythmias or aortic regurgitation, arrhythmia, treatment with antihypertensive medications, pre-eclampsia with or without severe features, preoperative infection, inability to use the study device for any reason, and incomplete data.

Randomization and Interventions

After informed consent, enrolled subjects were randomized (1:1) to treatment of hypotension according to conventional monitoring (Group CM) or monitoring by HPI (Group HPI). The total monitoring time was 4 hours starting from the initiation of ELA defined by the time of first dose of epidural medications. To enable group comparisons of total time in hypotension and other hemodynamic parameters, all participants wore continuous noninvasive blood pressure monitoring (CBPM): Group CM was blinded to CBPM output, while Group HPI received treatment of hypotension according to CBPM output and as specified by the hypotension treatment protocol below.

In Group HPI we used an index threshold for treatment that built upon findings from Maheshwari et al. [

13]. In their trial of 214 noncardiac surgical patients, 105 (49%) patients were randomized to management with a hypotension prediction algorithm, and intraoperative hypotension was not reduced compared with controls. They suggested that a lower alert threshold enabling adequate warning time, and a simpler treatment algorithm that emphasizes prompt treatment after alert may be useful. Therefore, our HPI alert threshold for treatment was specified at 75 and the treatment algorithm, specified below, was made as simple as possible.

Pre-ELA Protocol

Subjects received a 500mL crystalloid co-load that started during placement of ELA. Pregnant women in the lateral decubitus position can measure 10mmHg differences in dependent and upper arm blood pressures [

14]. Therefore, prior to ELA initiation the anticipated initial post-ELA decubitus position of the patient was clarified as Right or Left lateral decubitus. Standard monitoring was applied including pulse oximeter and non-invasive blood pressure (NIBP) cuff affixed over the non-dependent arm. In Group HPI both CBPM and NIBP monitors were applied on the same arm.

ELA Protocol

Baseline blood pressure was recorded immediately prior to the initiation of ELA. At subject request, a licensed and qualified anesthesia provider performed ELA using a combined spinal epidural (CSE) technique in the sitting position. CSE was chosen due to reliability and rapidity with which hypotension can be predicted within the ELA encounter. A meta-analysis of studies comparing low-dose epidural analgesia with CSE analgesia found no difference in the incidence of hypotension between the two techniques [

15].

The epidural space was found using loss of resistance to saline. A 25g or 27g Sprotte needle was introduced to the subarachnoid space. After confirmation of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), a spinal dose of fentanyl 15mcg and bupivacaine 2.5mg was given (this action defined T0 = initiation of CSE). At T0 blood pressure monitoring and data recordings began per the protocol specified below. A 19-20g flexible epidural catheter was then introduced and threaded 5-6cm into the epidural space. A test dose was delivered through the epidural catheter and consisted of 3mL lidocaine 1.5% with epinephrine. The anesthesia clinician declared positive or negative test dose 5 minutes after administration of test dose. A positive test dose (defined as heart rate increase >10 beats per minute at 30 seconds after injection, observation of both a metallic taste and tinnitus after injection, or warm or heavy sensation in the lower extremities at 3 minutes, or inability to raise legs within 4 to 10 minutes after injection) resulted in withdrawal from the study.

Maintenance of ELA was by patient-controlled epidural analgesia using programmed intermittent epidural bolus (PIEB) at our institutional standards: Ropivacaine 0.1% with fentanyl 2mcg/mL, 8mL every 40 minutes, 8mL demand every 8 minutes, maximum hourly volume 24mL (Smiths CADD®-Solis Infusion System, Infusion Pump, ICU Medical, Dublin, OH). The first PIEB dose was delivered 40 minutes after the initiation of the pump.

Hypotension Definition

We defined hypotension as a mean arterial pressure, MAP <65 mmHg for more than 1 minute. In Group CM, hypotension was measured by conventional non-invasive blood pressure cuff. In Group HPI hypotension was measured by CBPM and alerted when HPI threshold was <75 for more than 1 minute. Our hospital has existing protocols for epidural-associated hypotension to guide BP treatment: drop in systolic blood pressure (SBP) >20% from baseline, or systolic blood pressure <100 mmHg, or if there are any fetal heart rate concerns. These parameters continued per existing clinical standards if they were measured and detected by the NIBP regardless of group assignment and were expected to be evenly randomly distributed between the two groups by virtue of randomization. Random distribution of these events by frequency between groups, was assessed in analysis. Hypotension treatment protocols were standardized as below.

Monitoring and Hypotension Treatment Protocols

Monitoring occurred as follows. In Group CM at the time of test dose delivery, automated NIBP cycles began and were set to read every 3 minutes for 30 minutes, amounting to a total of at least 10 NIBP measurements. After 30 minutes, NIBP was cycled to every 15 minutes by existing clinical standards. At 4 hours, monitoring for the protocol ended. In Group HPI, at the time of test dose delivery, CBPM monitor continued. At 4 hours, monitoring for the protocol ended.

Hypotension treatment protocol: Group CM. In Group CM, at the first hypotensive episode, a 500mL intravenous fluid bolus was given, as well as ephedrine 10mg intravenous push. At the second hypotensive episode, an ephedrine 10mg intravenous push was given. For the third or more hypotensive episode, treatment was per physician anesthesiologist discretion.

Hypotension treatment protocol: Group HPI. For Group HPI, the hypotension treatment protocol was tailored to individual hemodynamic parameters. In Group HPI, at the first HPI alert, the hemodynamic relations screen was consulted and if the identified issue was one of preload, a 500mL intravenous fluid bolus was given; if a contractility or afterload issue was identified, ephedrine 10mg intravenous push was given. At the second HPI alert, the same approach was followed. At the third HPI alert, treatment was per physician anesthesiologist of record.

Self-Reported and Medical Record Data

Subjects were asked to report pain score immediately prior to ELA initiation, nausea, vomiting, or lightheadedness at any time during the monitoring period.

Data abstracted from the medical record included age, race, education level, smoking status, gravidity, parity, estimated gestational age, body mass index, induction vs. spontaneous labor, last known cervical exam at the time of ELA initiation, pain score immediately prior to ELA initiation, total vasopressor doses from time of ELA initiation until delivery, changes in fetal heart rate category, presence or absence of fetal heart rate decelerations within 1 hour of initiation of ELA, mode of delivery, neonatal weight, neonatal Apgar scores, neonatal cord blood pH.

Study Efficacy Endpoints. The primary endpoint was time-to-treatment of hypotension. Time-to-treatment was chosen as the primary endpoint because earlier treatment is hypothesized to mitigate downstream hemodynamic instability and improve maternal-fetal outcomes. Although less conventional than area under the curve (AUC) MAP <65 mmHg or time-weighted averages, it offers an implementation-relevant measure of system responsiveness and clinical workflow efficiency in a labor unit setting.

Secondary endpoints were: total minutes in hypotension accumulated from any time intervals with MAP<65 mmHg based on ClearSight™ readings; nausea; vomiting; total events of SBP drop >20% from baseline based on NIBP; total events of SBP<100 mmHg based on NIBP; changes in fetal heart rate category; presence or absence of fetal rate decelerations within one hour of initiation of ELA; total vasopressor doses (i.e., phenylephrine in mcg and ephedrine in mg); total intravenous fluids in labor (mL); and hemodynamic variables (Cardiac Output CO, Cardiac Index CI, Stroke Volume SV, Stroke Volume Variability SVV, Systemic Vascular Resistance SVR).

Feasibility and Acceptability Assessment

At the end of the monitoring period, subjects and their bedside nurses completed the Acceptability of Intervention Measure (AIM), Intervention Appropriateness Measure (IAM), and Feasibility of Intervention Measure (FIM) instruments—validated, standardized 4-item implementation outcome measures that assess perceived acceptability, appropriateness, and feasibility on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from ‘completely disagree’ to ‘completely agree’ [

16,

17]. The AIM, IAM and FIM are measures to determine the degree to which respondents believe the intervention is acceptable, appropriate, and feasible, and these are often used to assess the probability of implementation success. An average score ≥4 was considered a positive rating. This approach has been previously validated for evaluating interventions in clinical implementation research.

Statistical Analysis

Sample Size and Power Justification. The primary outcome was time-to-treatment of hypotension. Based on a meta-analysis of trials, the estimated incidence of hypotension after initiation of neuraxial analgesia during labor is approximately 19% (range: 3-35%) [

15] depending on population, definition, and timing of measurements. Cox proportional hazard models were used for this trial involving time-to-event analysis [

18]. For a fully powered study, a sample of 74 patients (37 in each intervention group) experiencing hypotension will show a hazard ratio of 0.50 with power of 80% and two-sided α=0.05, and a total of n=370 would need to be enrolled with 20% (n=74) experiencing hypotension events of interest. For this initial phase, we enrolled a target sample of 30 participants to evaluate study workflow, data completeness, subject and clinician acceptability, and feasibility, and to explore treatment effect estimates that can inform the design and planning of a larger definitive trial. This sample size was not intended to power formal hypothesis testing on time-to-treatment but rather was sufficient to assess real-world feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy signals under the study protocol. The efficacy analyses presented in this study provide estimates of effect directionality and variability, both of which are critical for determining the practicality and design requirements of subsequent studies.

Summary statistics and endpoint comparisons by monitoring groups. For continuous data, mean with standard deviation and median with interquartile range were both reported. For categorical variables, number with percentage was reported. Baseline characteristics and study endpoints were compared between treatment groups using nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous variables and Chi-square test or Fisher exact test for categorical variables.

Time-to-event analysis for primary endpoint. The Kaplan-Meier survival curves estimated the cumulative probability of time to first hypotension treatment over 4 hours of monitoring period between Group CM and Group HPI. Log-rank test was used to compare if the entire Kaplan-Meier survival curves differs by groups. Proportional hazards regression models were used to estimate hazards ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CI) to assess the effect of monitoring type on time to hypotension treatment.

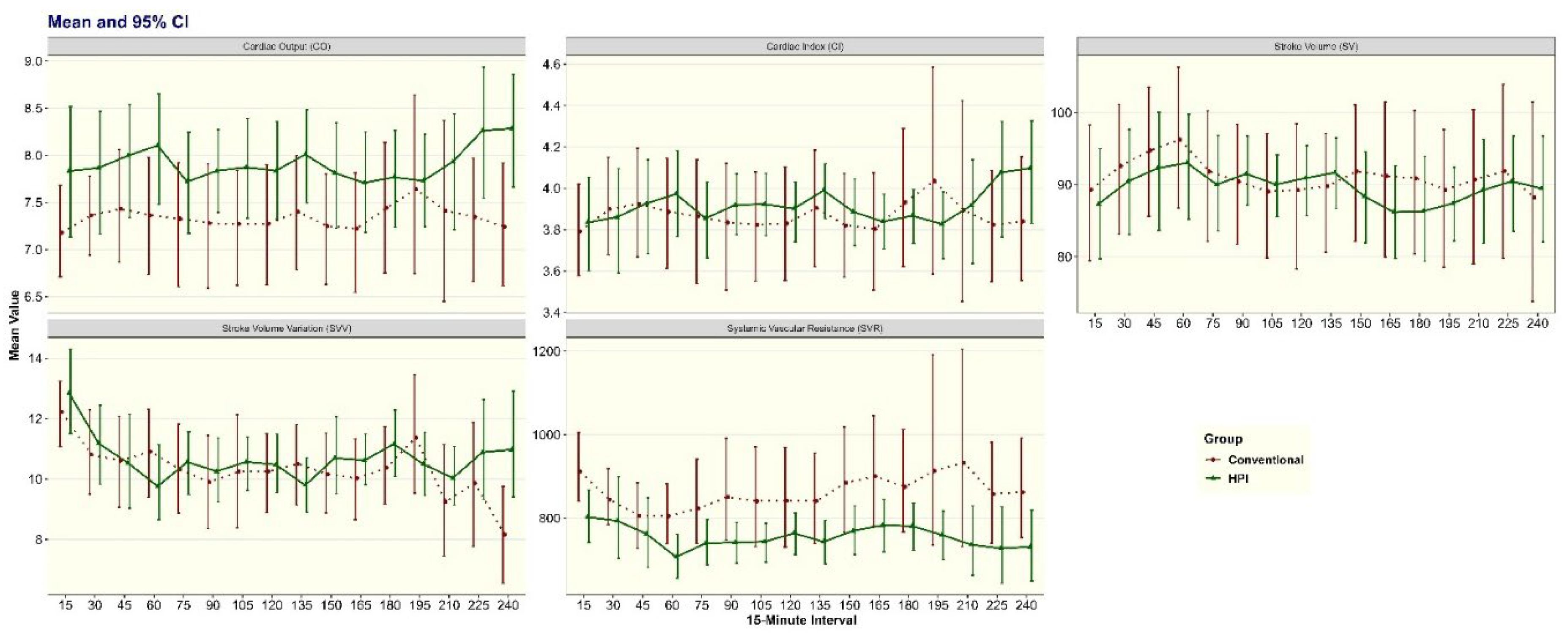

Hemodynamic Outcomes. Time series data for each hemodynamic outcome were averaged at every 15-minute interval. Mean and bootstrap 95%CI were used to illustrate the trends and differences between the two groups for CO, CI, SV, SVV, and SVR at each 15-min time interval. Random intercept mixed-effects models were used to estimate if each hemodynamic outcome differs between monitoring groups during the entire 4-hour monitoring period accounting for categorical time intervals. Interaction terms between monitoring groups and categorical time intervals were added to test if the change of hemodynamic outcomes over time differs by groups.

All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R version 4.1.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). A P < 0.05 was used to define statistical significance.

Results

Study Population and Characteristics

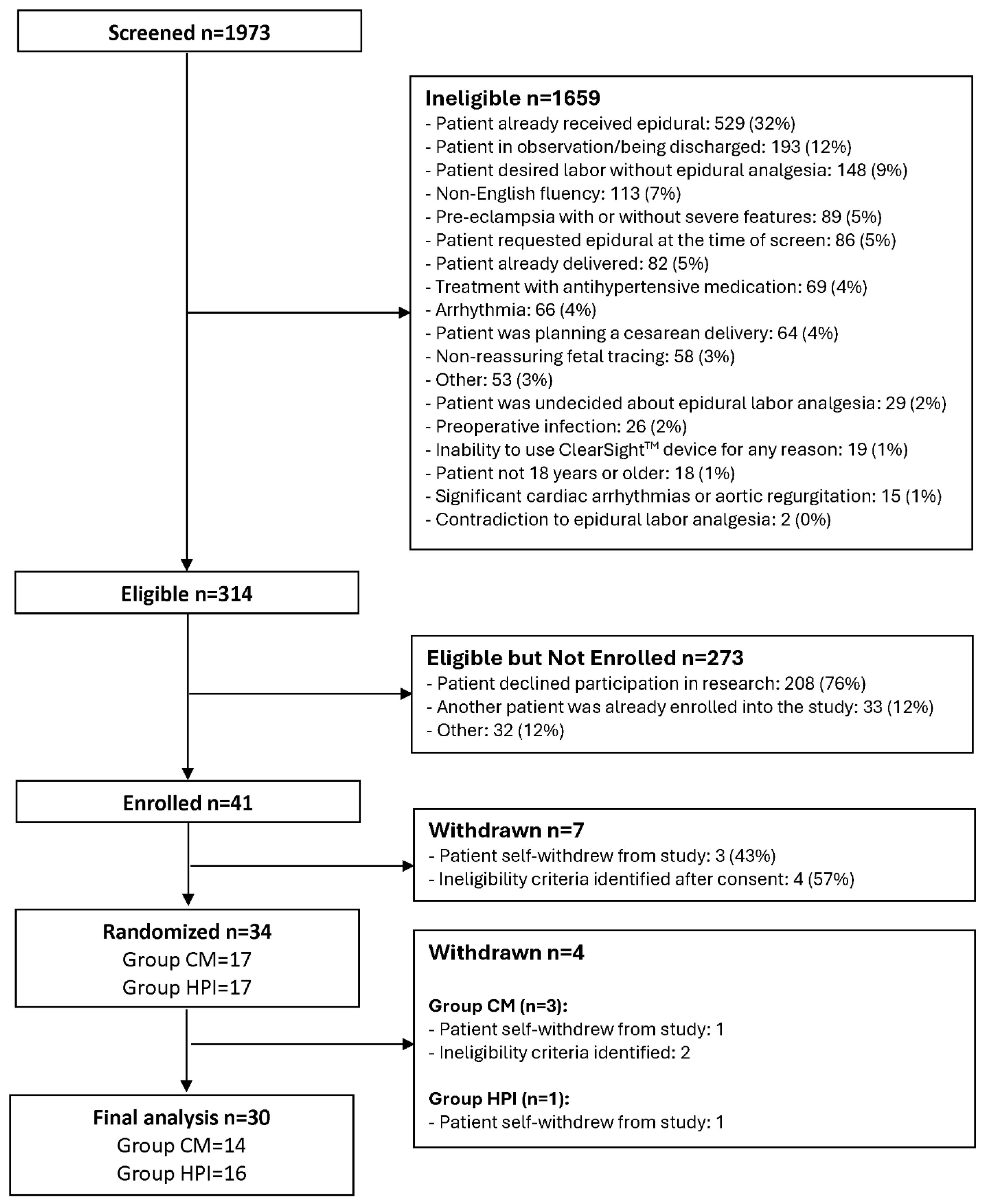

A total of 314 eligible participants were identified, and 41 (13%) were enrolled with signed informed consent forms, while 7 were withdrawn before randomization. Among 34 randomized participants (17 in Group CM and 17 in Group HPI), 3 additional participants were withdrawn from Group CM and 1 additional participant withdrawn from Group HPI. There were 30 subjects with complete data included in the final analysis (

Figure 1) with 14 (47%) randomized to Group CM and 16 (53%) to Group HPI. Mean (SD) age was 29.6 (5.5) years and 83% were White, 13% were Black, and 3% were Asian. Mean (SD) of BMI was 33.7 (5.8) kg/m2 and pain before epidural was 5.6 (3.1). There were no statistically significant differences between Group CM and HPI for baseline and self-reported characteristics (

Table 1).

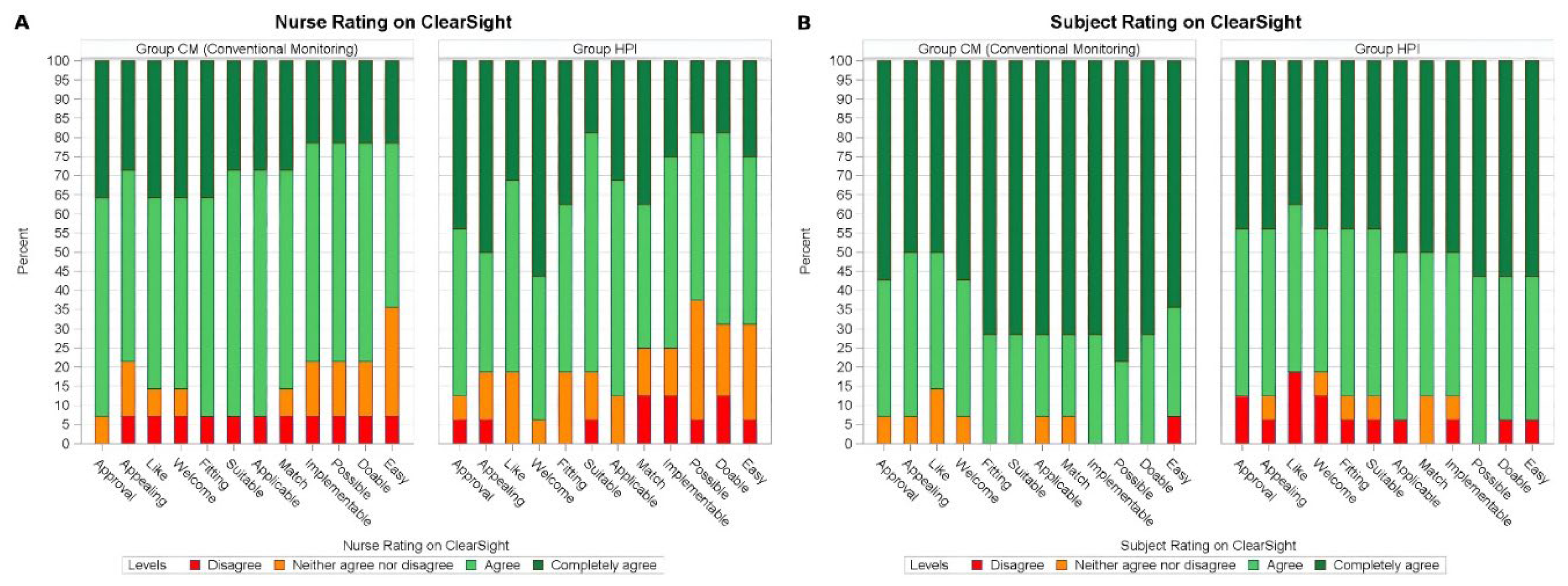

Feasibility, Appropriateness, and Acceptability

Both patient and nurse ratings for AIM, IAM, and FIM were primarily positive, indicating that both groups rated the study device with high acceptability, appropriateness, and feasibility. Both patients and nurses rated the intervention highly across all implementation domains (median score ≥4 for all items) (

Figure 2).

Primary Endpoint: Time to First Hypotension Treatment

The frequency of any hypotensive events was not different between Group CM (71%) and Group HPI (63%). Among 20 subjects who experienced hypotensive events, the median time-to-treatment was 14.5 minutes in Group CM and 16.0 minutes in Group HPI (

Table 2). The Kaplan-Meier survival analysis estimated the first hypotension treatment probability for patients in Group CM and Group HPI. At 75 minutes, the cumulative probability of for Group CM was 71%, compared to 65% for Group HPI, and remained the same probabilities through the end of the 4-hour monitoring period. The survival difference was not statistically significantly different (log-rank

P=0.66), indicating that patients in Group CM and Group HPI were similar with respect to the probability of time to first hypotension treatment (

Supplemental Figure S1). The Cox proportional hazards regression model shows an HR of 0.82 (95% CI: 0.34-1.98) in Group HPI compared to Group CM. (

Supplemental Table S1).

Secondary Analysis – Clinical and Hemodynamic Outcomes

Total minutes with MAP<65 based on CBPM was similar between the groups (median 3.0 minutes in Group CM vs 4.7 minutes in Group HPI;

P>0.99). There were trends toward higher rates of vomiting in Group CM (21%) compared to Group HPI (0%) (

P=0.09) (

Table 2). There were no differences between Group CM and Group HPI for NIBP-measured frequency of SBP drop >20% from baseline, SBP <100mmHg, and fetal heart rate tracing concerns (

Table 2). Among 20 subjects who experienced hypotensive events, total doses of ephedrine and phenylephrine, and total intravenous fluid volumes were not different between groups (

Table 2).

CO was higher for Group HPI over the entire monitoring period (β=0.58; 95%CI: -0.18, 1.34,

P=0.13). High SVR is a physiological risk factor known to influence placental and fetal perfusion. SVR was lower in Group HPI for the entire monitoring period (β= -97.22; 95% CI: -200.84, 6.40,

P=0.07) even though it was not statistically significant. The rate of change over time in hemodynamic variables was not significantly different by monitoring groups after testing the interaction term between group and time variables in random intercept mixed effects models. (

Supplemental Table S2, Figure S3).

Discussion

The primary findings of this trial are that that an HPI-guided hypotension clinical trial protocol in labor and delivery is feasible, appropriate, and acceptable to patients and clinicians, and treatment according to the HPI may result in improved maternal hemodynamics (i.e., cardiac output, cardiac index, and systemic vascular resistance) during labor and delivery. These findings are significant because they suggest that real-time hemodynamic monitoring using HPI can lead to reduced risks associated with delayed treatment, such as compromised maternal hemodynamics and maternal-fetal perfusion. Our results provide further justification for future studies using larger sample sizes to make definitive conclusions about the potential role of HPI-guided therapies for modern epidural labor analgesia hypotension management. These findings are significant because they suggest that real-time hemodynamic monitoring using HPI is not only technically feasible, but may be practical for scalable clinical integration into routine labor care.

Previous studies have shown comparable results favoring benefits of HPI-guided therapies. In one randomized trial [

19], HPI was used with goal-directed therapy to manage intraoperative hypotension. The study reported a reduction in the number of hypotensive episodes when using HPI, particularly for optimization of hemodynamics, fluid, and vasopressor administration. Our study considered the findings from Maheshwari et al. [

13], which suggested that lower alert threshold and simpler treatment protocols would improve outcomes. Our HPI treatment index was set below that of Maheshwari et al and our protocol was considerate of treatment norms in our hospital. Our findings support that a lower HPI trigger and a simple treatment protocol may improve maternal hemodynamics and is feasible and acceptable to subjects and clinicians alike.

To our knowledge this is the first study assessing HPI-guided therapies specifically in labor and delivery for the purpose of improving outcomes associated with epidural labor analgesia. Previous studies have primarily focused on non-obstetric populations, such as intraoperative hypotension management in noncardiac surgery, where HPI-guided therapy has had variable results on hypotension outcomes and markers of tissue perfusion [

13,

20]. Research in obstetric-specific contexts is necessary to optimize protocols for HPI in childbirth. Our findings show smaller confidence intervals in Group HPI around several hemodynamic parameters, which suggests that HPI-guided treatment for ELA-associated hypotension may result in more precise control of hemodynamic targets. These findings may be primarily because HPI-guided treatment enables more precise therapies according to specific hemodynamic perturbation (e.g., correcting a systemic vascular resistance issue with vasopressors, correcting a preload issue with volume). Targeted hemodynamic therapies have implications for clinically relevant outcomes in the birth context, specifically for improving placental perfusion and prevention of emergent interventions for fetal distress that may result from placental insufficiency during labor and delivery.

We were surprised to see that our study shows 63-71% for hypotensive events, which is higher than previous estimates. Notably, in published literature the quoted incidence of hypotension after epidural labor analgesia is highly variable with estimates ranging between 14% and 36% [

15,

21,

22]. These variations can be attributed to differences in study populations, definitions of hypotension, and clinical practices. In our study, we used a definition of hypotension that was consistent with our existing hospital policies and on the definition of hypotension that informed HPI technology. Some explanations for our measured differences compared to what has been previously quoted may be because our institutional definitions of hypotension are more conservative than published literature thereby leading to more patients meeting the hypotension definition, or because patients who elected to participate were interested because they were more prone to hypotensive events.

This study has several limitations. First, the sample size of 30 participants was intentionally small as a feasibility study. The small sample limits making definitive conclusions, but it was helpful in indicating trends to inform future trials. In our study, hemodynamic trends are indicating potential benefits of HPI-guided therapies, particularly for cardiac output and systemic vascular resistance. A larger trial is needed to validate these results across more diverse populations. Second, the study duration was limited to 4 hours of monitoring following epidural labor analgesia (ELA), which may not capture late-onset hypotension events or other long-term hemodynamic changes. Future trials can expand the monitoring period. Additionally, the study relied on continuous monitoring from the CBPM system, and while this technology has shown promise, the comparison with intermittent non-invasive blood pressure (NIBP) monitoring may not fully reflect real-world clinical conditions where frequent interruptions or device malfunctions could occur.

This study did not include area under the curve (AUC) MAP <65 mmHg or time-weighted hypotension metrics, which are commonly used in intraoperative hypotension research. However, the clinical setting and objectives of this study differed from conventional studies: our focus was on feasibility, acceptability, and care responsiveness in a dynamic labor environment, where time-to-treatment serves as a more actionable and patient-centered implementation outcome. These conventional efficacy endpoints will be considered for incorporation into an analytic plan for a larger and fully powered trial on efficacy.

Our results suggest that adopting a protocol focused on earlier treatment of hypotension in labor and delivery can result in improvements in maternal physiology and symptoms. These improvements may also translate to improved fetal-neonatal outcomes although trials are needed to assess the impact of HPI-driven protocols on fetal-neonatal outcomes specifically.

Future studies should explore long-term maternal and neonatal outcomes associated with HPI-guided interventions, including outcomes for the entirety of labor and delivery and postpartum. Larger trials in diverse populations would be valuable to validate the effectiveness of HPI across patient groups and settings, and to optimize the alert thresholds and treatment algorithms. Also, examining the cost-effectiveness of implementing continuous HPI monitoring on labor units will be critical in determining its value and practicality in routine clinical practice across all practice settings. Research should also assess the impact of HPI-guided management on preventing adverse fetal outcomes that are attributable to maternal hypotension.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study provides evidence that continuous monitoring and HPI-driven protocols to detect and treat hypotension in labor and delivery are feasible, appropriate, and acceptable to patients and clinicians. Although this study was not designed or intended to be powered to detect significant differences in tme-to-treatment, we detected interesting trends in higher cardiac output and lower systemic vascular resistance, suggesting the potential for clinical benefit with HPI-guided treatment. These findings support further exploration in a larger trial.

HPI-guided treatment represents a promising digital strategy to improve maternal hemodynamics and exemplifies how AI-driven monitoring can advance precision and responsiveness in obstetric anesthesia care. It has the potential to support earlier detection and precision treatment of epidural-associated hypotension, a common childbirth event with maternal and fetal safety implications. Future trials are needed to fully inform the clinical utility of HPI-guided labor anesthetic management. Future work should also explore how continuous monitoring and prediction platforms can be integrated with electronic medical records and clinical decision support systems to streamline implementation and ensure timely clinical response.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

Preprints.org.

Funding

This study was supported by Edwards Lifesciences (monitor, disposables, support for clinical research staff). Dr. Lim receives salary and research support from NIH UH3CA261067, NIH R01MH134538, and Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI EASCS-34606).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to UPMC Magee Women’s hospital staff for their support of this study. We are also grateful to Missy McCallister for her assistance with the study devices. Finally, we are thankful to Amy Monroe, Alisha Maslanka, Barkha Patel, Julia Falgione, Alex Anderson, and Rose Barlow, who were instrumental to the success of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Lim receives research support, consulting honoraria, and chairs or is member of advisory board from: Octapharma, Heron Pharmaceuticals, Haemonetics, all unrelated to this publication. Dr. Lim receives stipends for medical expert testimony not related to this publication. Dr. Lim receives textbook royalties from Cambridge University Press not related to this publication.

References

- Practice Guidelines for Obstetric Anesthesia: An Updated Report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Obstetric Anesthesia and the Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology. Anesthesiology 2016, 124, 270–300. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.; Siddiqui, Z.; Anderson, N.; Chen, C.M.; Chatterji, M.; Smiley, R.; et al. Check the Blood Pressure!: An Educational Tool for Anesthesiology Trainees Converting Epidural Labor Analgesia to Cesarean Delivery Anesthesia. A A Pract. 2020, 14, e01174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyer, R.A.; Reed, A.R.; van Dyk, D.; Arcache, M.J.; Hodges, O.; Lombard, C.J.; et al. Hemodynamic effects of ephedrine, phenylephrine, and the coadministration of phenylephrine with oxytocin during spinal anesthesia for elective cesarean delivery. Anesthesiology 2009, 111, 753–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatib, F.; Jian, Z.; Buddi, S.; Lee, C.; Settels, J.; Sibert, K.; et al. Machine-learning Algorithm to Predict Hypotension Based on High-fidelity Arterial Pressure Waveform Analysis. Anesthesiology 2018, 129, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frassanito, L.; Giuri, P.P.; Vassalli, F.; Piersanti, A.; Longo, A.; Zanfini, B.A.; et al. Hypotension Prediction Index with non-invasive continuous arterial pressure waveforms (ClearSight): Clinical performance in Gynaecologic Oncologic Surgery. J Clin Monit Comput. 2022, 36, 1325–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Frassanito, L.; Sonnino, C.; Piersanti, A.; Zanfini, B.A.; Catarci, S.; Giuri, P.P.; et al. Performance of the Hypotension Prediction Index With Noninvasive Arterial Pressure Waveforms in Awake Cesarean Delivery Patients Under Spinal Anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 2022, 134, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juri, T.; Suehiro, K.; Kimura, A.; Mukai, A.; Tanaka, K.; Yamada, T.; et al. Impact of non-invasive continuous blood pressure monitoring on maternal hypotension during cesarean delivery: A randomized-controlled study. J Anesth. 2018, 32, 822–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maheshwari, K.; Buddi, S.; Jian, Z.; Settels, J.; Shimada, T.; Cohen, B.; et al. Performance of the Hypotension Prediction Index with non-invasive arterial pressure waveforms in non-cardiac surgical patients. J Clin Monit Comput. 2021, 35, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Helmer, P.; Helf, D.; Sammeth, M.; Winkler, B.; Hottenrott, S.; Meybohm, P.; Kranke, P. The Use of Non-Invasive Continuous Blood Pressure Measuring (ClearSight(®)) during Central Neuraxial Anaesthesia for Caesarean Section-A Retrospective Validation Study. J Clin Med. 2022, 11, 4498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Davies, S.J.; Vistisen, S.T.; Jian, Z.; Hatib, F.; Scheeren, T.W.L. Ability of an Arterial Waveform Analysis-Derived Hypotension Prediction Index to Predict Future Hypotensive Events in Surgical Patients. Anesth Analg. 2020, 130, 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinsky, M.R.; Cecconi, M.; Chew, M.S.; De Backer, D.; Douglas, I.; Edwards, M.; et al. Effective hemodynamic monitoring. Crit Care. 2022, 26, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sidiropoulou, T.; Tsoumpa, M.; Griva, P.; Galarioti, V.; Matsota, P. Prediction and Prevention of Intraoperative Hypotension with the Hypotension Prediction Index: A Narrative Review. J Clin Med. 2022, 11, 5551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Maheshwari, K.; Shimada, T.; Yang, D.; Khanna, S.; Cywinski, J.B.; Irefin, S.A.; et al. Hypotension Prediction Index for Prevention of Hypotension during Moderate- to High-risk Noncardiac Surgery. Anesthesiology 2020, 133, 1214–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinsella, S.M.; Black, A.M. Reporting of ‘hypotension’ after epidural analgesia during labour. Effect of choice of arm and timing of baseline readings. Anaesthesia 1998, 53, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simmons, S.W.; Taghizadeh, N.; Dennis, A.T.; Hughes, D.; Cyna, A.M. Combined spinal-epidural versus epidural analgesia in labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012, 10, Cd003401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Proctor, E.; Silmere, H.; Raghavan, R.; Hovmand, P.; Aarons, G.; Bunger, A.; et al. Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011, 38, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Weiner, B.J.; Lewis, C.C.; Stanick, C.; Powell, B.J.; Dorsey, C.N.; Clary, A.S.; et al. Psychometric assessment of three newly developed implementation outcome measures. Implement Sci. 2017, 12, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schoenfeld, D.A. Sample-size formula for the proportional-hazards regression model. Biometrics 1983, 39, 499–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šribar, A.; Jurinjak, I.S.; Almahariq, H.; Bandić, I.; Matošević, J.; Pejić, J.; Peršec, J. Hypotension prediction index guided versus conventional goal directed therapy to reduce intraoperative hypotension during thoracic surgery: A randomized trial. BMC Anesthesiol. 2023, 23, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lorente, J.V.; Ripollés-Melchor, J.; Jiménez, I.; Becerra, A.I.; Mojarro, I.; Fernández-Valdes-Bango, P.; et al. Intraoperative hemodynamic optimization using the hypotension prediction index vs. goal-directed hemodynamic therapy during elective major abdominal surgery: The Predict-H multicenter randomized controlled trial. Frontiers in Anesthesiology 2023, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghidini, A.; Vanasche, K.; Cacace, A.; Cacace, M.; Fumagalli, S.; Locatelli, A. Side effects from epidural analgesia in laboring women and risk of cesarean delivery. AJOG Glob Rep. 2024, 4, 100297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Korb, D.; Bonnin, M.; Michel, J.; Oury, J.F.; Sibony, O. Analysis of fetal heart rate abnormalities occurring within one hour after laying of epidural analgesia. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris) 2013, 42, 564–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).