Submitted:

22 April 2025

Posted:

24 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Monocyte-Derived Dendritic Cells Obtention

2.2. Lyophilization and Protein Quantification

2.4. Characterization of moDC

2.5. Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy.

2.6. Cytokine Production

2.7. Identification and Expression of Toll-like Receptors (TLRs)

2.8. Flow Cytometry Analysis

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Pulmonarom® Extract Induces Ultrastructural Morphological Changes in moDC.

3.2. Pulmonarom® Extract Increases Class II Histocompatibility Molecules in Dendritic Cells.

3.3. Pulmonarom® Extract Increases the Expression of TLRs 2, 3, 6, and 7

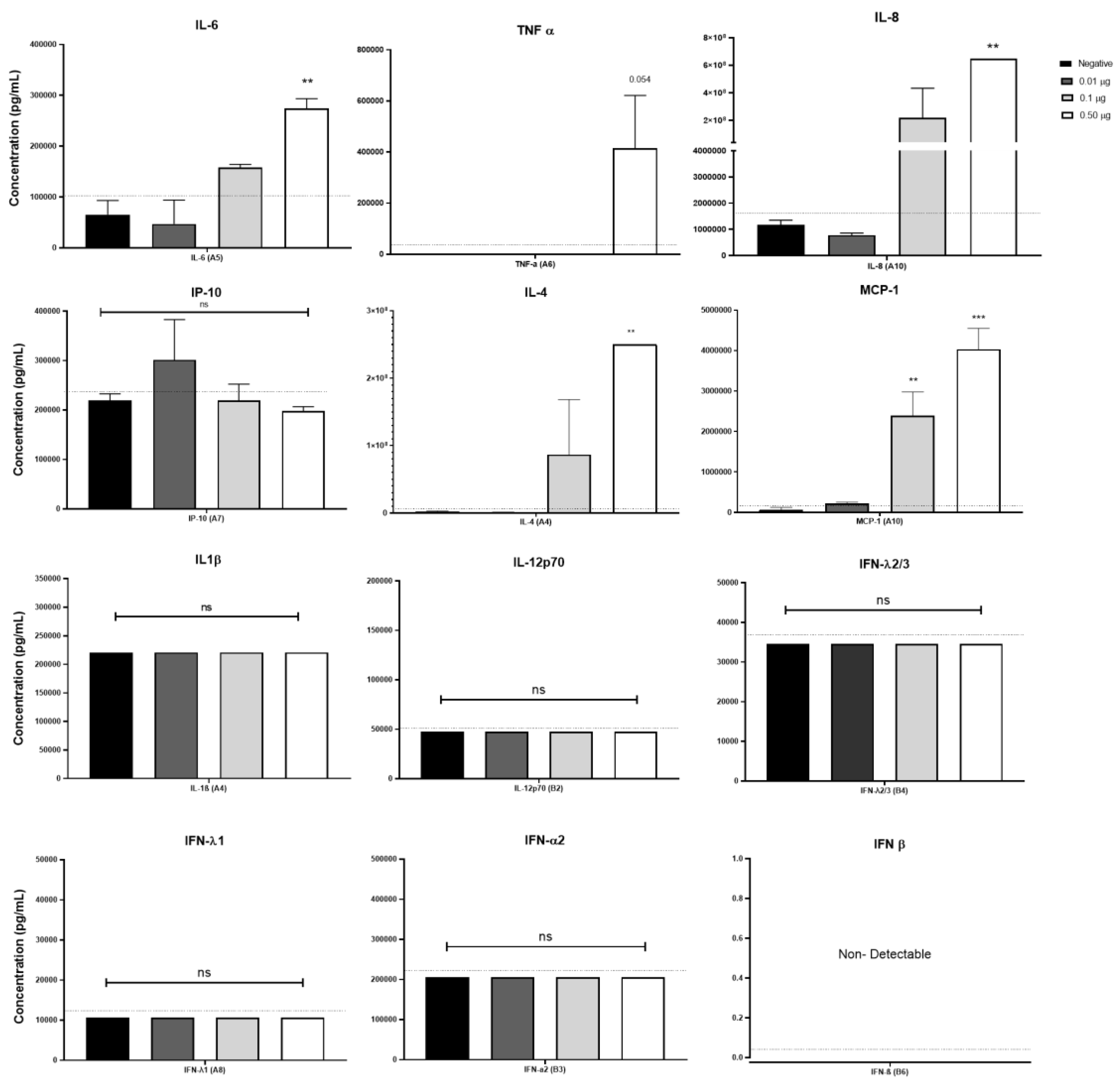

3.4. Pulmonarom® Increases the Production of IL-4, IL-6, IL-8 and MCP-1.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Authors Contributions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

References

- Sirota SB, Doxey MC, Dominguez RMV, Bender RG, Vongpradith A, Albertson SB, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of upper respiratory infections and otitis media, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Infect Dis [Internet]. 2024 Jan 1 [cited 2025 Jan 19];25[1]:36–51. Available from: http://www.thelancet.com/article/S1473309924004304/fulltext.

- Bender, R.G.; Sirota, S.B.; Swetschinski, L.R.; Dominguez, R.-M.V.; Novotney, A.; E Wool, E.; Ikuta, K.S.; Vongpradith, A.; Rogowski, E.L.B.; Doxey, M.; et al. Global, regional, and national incidence and mortality burden of non-COVID-19 lower respiratory infections and aetiologies, 1990–2021: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 974–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global immunization efforts have saved at least 154 million lives over the past 50 years [Internet]. [cited 2025 Mar 20]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/24-04-2024-global-immunization-efforts-have-saved-at-least-154-million-lives-over-the-past-50-years.

- Communities vulnerable without immunization against infectious diseases [Internet]. [cited 2025 Mar 20]. Available from: https://www.who.int/malaysia/news/detail/23-04-2020-communities-vulnerable-without-immunization-against-infectious-diseases.

- Coviello, S.; Wimmenauer, V.; Polack, F.P.; Irusta, P.M. Bacterial lysates improve the protective antibody response against respiratory viruses through Toll-like receptor 4. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2014, 10, 2896–2902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinderola, G.; Sanders, M.E.; Cunningham, M.; Hill, C. Frequently asked questions about the ISAPP postbiotic definition. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1324565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salminen, S.; Collado, M.C.; Endo, A.; Hill, C.; Lebeer, S.; Quigley, E.M.M.; Sanders, M.E.; Shamir, R.; Swann, J.R.; Szajewska, H.; et al. The International Scientific Association of Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of postbiotics. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 649–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Green, K.M.; Rawat, M. A Comprehensive Overview of Postbiotics with a Special Focus on Discovery Techniques and Clinical Applications. Foods 2024, 13, 2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moser, M.; Murphy, K.M. Dendritic cell regulation of TH1-TH2 development. Nat. Immunol. 2000, 1, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Itano, A.; McSorley, S.J.; Reinhardt, R.; Ehst, B.D.; Ingulli, E.; Rudensky, A.Y.; Jenkins, M.K. Distinct Dendritic Cell Populations Sequentially Present Antigen to CD4 T Cells and Stimulate Different Aspects of Cell-Mediated Immunity. Immunity 2003, 19, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo PM, Gallucci S. The Dendritic Cell Response to Classic, Emerging, and Homeostatic Danger Signals. Implications for Autoimmunity. Front Immunol [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2025 Feb 8];4(JUN):138. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3677085/.

- Solano-Gálvez, S.G.; Tovar-Torres, S.M.; Tron-Gómez, M.S.; Weiser-Smeke, A.E.; Álvarez-Hernández, D.A.; Franyuti-Kelly, G.A.; Tapia-Moreno, M.; Ibarra, A.; Gutiérrez-Kobeh, L.; Vázquez-López, R. Human Dendritic Cells: Ontogeny and Their Subsets in Health and Disease. Med Sci. 2018, 6, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rial, A.; Lens, D.; Betancor, L.; Benkiel, H.; Silva, J.S.; Chabalgoity, J.A. Intranasal Immunization with a Colloid-Formulated Bacterial Extract Induces an Acute Inflammatory Response in the Lungs and Elicits Specific Immune Responses. Infect. Immun. 2004, 72, 2679–2688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquali, C.; Salami, O.; Taneja, M.; Gollwitzer, E.S.; Trompette, A.; Pattaroni, C.; Yadava, K.; Bauer, J.; Marsland, B.J. Enhanced Mucosal Antibody Production and Protection against Respiratory Infections Following an Orally Administered Bacterial Extract. Front. Med. 2014, 1, 41–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, G.A.; Bessler, W.; Ballarini, S.; Pasquali, C. Evidence that a primary anti-viral stimulation of the immune response by OM-85 reduces susceptibility to a secondary respiratory bacterial infection in mice. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2018, 44, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antunes, K.H.; Cassão, G.; Santos, L.D.; Borges, S.G.; Poppe, J.; Gonçalves, J.B.; Nunes, E.d.S.; Recacho, G.F.; Sousa, V.B.; Da Silva, G.S.; et al. Airway Administration of Bacterial Lysate OM-85 Protects Mice Against Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 867022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, T.; Du, Y.; Xing, C.; Wang, H.Y.; Wang, R.-F. Toll-Like Receptor Signaling and Its Role in Cell-Mediated Immunity. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 812774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallusto, F.; Lanzavecchia, A. Efficient presentation of soluble antigen by cultured human dendritic cells is maintained by granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor plus interleukin 4 and downregulated by tumor necrosis factor alpha. J. Exp. Med. 1994, 179, 1109–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romani, N.; Gruner, S.; Brang, D.; Kämpgen, E.; Lenz, A.; Trockenbacher, B.; Konwalinka, G.; O Fritsch, P.; Steinman, R.M.; Schuler, G. Proliferating dendritic cell progenitors in human blood. J. Exp. Med. 1994, 180, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, S.; Cossalter, G.; Chiavaroli, C.; Kanda, A.; Fleury, S.; Lazzari, A.; Cazareth, J.; Sparwasser, T.; Dombrowicz, D.; Glaichenhaus, N.; et al. The oral administration of bacterial extracts prevents asthma via the recruitment of regulatory T cells to the airways. Mucosal Immunol. 2011, 4, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber M MHBW. Eur J Med Res. 2005 [cited 2022 Nov 29]. p. 209–17 Th1-orientated immunological properties of the bacterial extract OM-85-BV - PubMed. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15946922/.

- McInturff, J.E.; Modlin, R.L.; Kim, J. The Role of Toll-like Receptors in the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Dermatological Disease. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2005, 125, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruby, J.; Bluethmann, H.; Peschon, J.J. Antiviral Activity of Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF) Is Mediated via p55 and p75 TNF Receptors. J. Exp. Med. 1997, 186, 1591–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertz, C.J.; Wu, Q.; Porter, E.M.; Zhang, Y.J.; Weismüller, K.-H.; Godowski, P.J.; Ganz, T.; Randell, S.H.; Modlin, R.L. Activation of Toll-Like Receptor 2 on Human Tracheobronchial Epithelial Cells Induces the Antimicrobial Peptide Human β Defensin-2. J. Immunol. 2003, 171, 6820–6826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, J.; Kulatheepan, Y.; Jeyaseelan, S. Role of toll-like receptors and nod-like receptors in acute lung infection. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1249098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Grice, I.D.; Ulett, G.C.; Wei, M.Q. Advances in Bacterial Lysate Immunotherapy for Infectious Diseases and Cancer. J. Immunol. Res. 2024, 2024, 4312908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.K.; Kim, J. Properties of immature and mature dendritic cells: phenotype, morphology, phagocytosis, and migration. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 11230–11238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landmann, S.; Mühlethaler-Mottet, A.; Bernasconi, L.; Suter, T.; Waldburger, J.-M.; Masternak, K.; Arrighi, J.-F.; Hauser, C.; Fontana, A.; Reith, W. Maturation of Dendritic Cells Is Accompanied by Rapid Transcriptional Silencing of Class II Transactivator (Ciita) Expression. J. Exp. Med. 2001, 194, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trombetta, E.S.; Ebersold, M.; Garrett, W.; Pypaert, M.; Mellman, I. Activation of Lysosomal Function During Dendritic Cell Maturation. Science 2003, 299, 1400–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumoza-Toledo, A.; Lange, I.; Cortado, H.; Bhagat, H.; Mori, Y.; Fleig, A.; Penner, R.; Partida-Sánchez, S. Dendritic cell maturation and chemotaxis is regulated by TRPM2-mediated lysosomal Ca2+release. FASEB J. 2011, 25, 3529–3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bretou, M.; Sáez, P.J.; Sanséau, D.; Maurin, M.; Lankar, D.; Chabaud, M.; Spampanato, C.; Malbec, O.; Barbier, L.; Muallem, S.; et al. Lysosome signaling controls the migration of dendritic cells. Sci. Immunol. 2017, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Rong, S.-J.; Zhou, H.-F.; Yang, C.; Sun, F.; Li, J.-Y. Lysosomal control of dendritic cell function. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2023, 114, 518–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyanakian MA, Grela F, Aumeunier A, Chiavaroli C, Gouarin C, Bardel E, et al. Transforming Growth Factor-β and Natural Killer T-Cells Are Involved in the Protective Effect of a Bacterial Extract on Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes [Internet]. 2006 Jan 1 [cited 2022 Dec 4];55[1]:179–85. Available from: https://diabetesjournals.org/diabetes/article/55/1/179/12316/Transforming-Growth-Factor-and-Natural-Killer-T.

- Dang, A.T.; Pasquali, C.; Ludigs, K.; Guarda, G. OM-85 is an immunomodulator of interferon-β production and inflammasome activity. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, srep43844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morokata T, Ishikawa J, Ida K, Yamada T. C57BL/6 mice are more susceptible to antigen-induced pulmonary eosinophilia than BALB/c mice, irrespective of systemic T helper 1/T helper 2 responses. Immunology [Internet]. 1999 [cited 2025 Mar 17];98[3]:345–51. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10583592/.

- van der Sluis, R.M.; Cham, L.B.; Gris-Oliver, A.; Gammelgaard, K.R.; Pedersen, J.G.; Idorn, M.; Ahmadov, U.; Hernandez, S.S.; Cémalovic, E.; Godsk, S.H.; et al. TLR2 and TLR7 mediate distinct immunopathological and antiviral plasmacytoid dendritic cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 infection. EMBO J. 2022, 41, e109622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murawski, M.R.; Bowen, G.N.; Cerny, A.M.; Anderson, L.J.; Haynes, L.M.; Tripp, R.A.; Kurt-Jones, E.A.; Finberg, R.W. Respiratory Syncytial Virus Activates Innate Immunity through Toll-Like Receptor 2. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 1492–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groskreutz, D.J.; Monick, M.M.; Powers, L.S.; Yarovinsky, T.O.; Look, D.C.; Hunninghake, G.W. Respiratory Syncytial Virus Induces TLR3 Protein and Protein Kinase R, Leading to Increased Double-Stranded RNA Responsiveness in Airway Epithelial Cells. J. Immunol. 2006, 176, 1733–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwasaki A, Pillai PS. Innate immunity to influenza virus infection. Nature Reviews Immunology 2014 14:5 [Internet]. 2014 Apr 25 [cited 2025 Jan 26];14[5]:315–28. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/nri3665.

- Chen, Y.; Lin, J.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, X.; Yi, H. Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) regulation mechanisms and roles in antiviral innate immune responses. J. Zhejiang Univ. B 2021, 22, 609–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stowell, N.C.; Seideman, J.; A Raymond, H.; A Smalley, K.; Lamb, R.J.; Egenolf, D.D.; Bugelski, P.J.; A Murray, L.; A Marsters, P.; A Bunting, R.; et al. Long-term activation of TLR3 by Poly(I:C) induces inflammation and impairs lung function in mice. Respir. Res. 2009, 10, 43–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, H.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, L.; Wang, C.; Zhang, M.; Xu, X.; Zhou, H.; Li, X.; Xu, Q.; He, F.; et al. OM85-BV Induced the Productions of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α via TLR4- and TLR2-Mediated ERK1/2/NF-κB Pathway in RAW264.7 Cells. J. Interf. Cytokine Res. 2014, 34, 526–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Böttcher, J.P.; Schanz, O.; Garbers, C.; Zaremba, A.; Hegenbarth, S.; Kurts, C.; Beyer, M.; Schultze, J.L.; Kastenmüller, W.; Rose-John, S.; et al. IL-6 trans-Signaling-Dependent Rapid Development of Cytotoxic CD8+ T Cell Function. Cell Rep. 2014, 8, 1318–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubernatorova, E.; Gorshkova, E.; Polinova, A.; Drutskaya, M. IL-6: Relevance for immunopathology of SARS-CoV-2. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2020, 53, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, S.T.; Lai, J.; Ma, J.; Stacey, H.D.; Miller, M.S.; Mullarkey, C.E. Neutrophils and Influenza: A Thin Line between Helpful and Harmful. Vaccines 2021, 9, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullarkey, C.E.; Bailey, M.J.; Golubeva, D.A.; Tan, G.S.; Nachbagauer, R.; He, W.; Novakowski, K.E.; Bowdish, D.M.; Miller, M.S.; Palese, P. Broadly Neutralizing Hemagglutinin Stalk-Specific Antibodies Induce Potent Phagocytosis of Immune Complexes by Neutrophils in an Fc-Dependent Manner. mBio 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, C.; Means, T.K.; Autissier, P.; Woodberry, T.; Altfeld, M.; Addo, M.M.; Frahm, N.; Brander, C.; Walker, B.D.; Luster, A.D. IL-8 responsiveness defines a subset of CD8 T cells poised to kill. Blood 2004, 104, 3463–3471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quach, H.Q.; Goergen, K.M.; E Grill, D.; Ovsyannikova, I.G.; A Poland, G.; Kennedy, R.B. IL-8 as a Causal Link Between Aging and Impaired Influenza Antibody Responses in Older Adults. J. Infect. Dis. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, V.; Sant’anna, O.A.; Lord, J.M. Ageing and myeloid-derived suppressor cells: possible involvement in immunosenescence and age-related disease. AGE 2014, 36, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawelec, G.; Picard, E.; Bueno, V.; Verschoor, C.P.; Ostrand-Rosenberg, S. MDSCs, ageing and inflammageing. Cell. Immunol. 2021, 362, 104297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekkering, S.; Domínguez-Andrés, J.; Joosten, L.A.; Riksen, N.P.; Netea, M.G. Trained Immunity: Reprogramming Innate Immunity in Health and Disease. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 39, 667–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleinnijenhuis, J.; Quintin, J.; Preijers, F.; Joosten, L.A.B.; Ifrim, D.C.; Saeed, S.; Jacobs, C.; van Loenhout, J.; de Jong, D.; Stunnenberg, H.G.; et al. Bacille Calmette-Guérin induces NOD2-dependent nonspecific protection from reinfection via epigenetic reprogramming of monocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012, 109, 17537–17542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcaraz-Serna, A.; Bustos-Morán, E.; Fernández-Delgado, I.; Calzada-Fraile, D.; Torralba, D.; Marina-Zárate, E.; Lorenzo-Vivas, E.; Vázquez, E.; de Alburquerque, J.B.; Ruef, N.; et al. Immune synapse instructs epigenomic and transcriptomic functional reprogramming in dendritic cells. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabb9965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).