1. Introduction

Highlights

What are the main findings?

The uptake of COPD clinical practice guidelines among primary care facilities in Granada is low

This is specially true for the assessment of the symptom burden of this disease with evidence- based recommended questionnaires such as mMRC and CAT.

What is the implication of the main finding?

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) is a highly prevalent respiratory disease. National prevalence data from EPISCAN 1 study showed that this disease affects more than 10% of the Spanish adult population aged between 40 and 80 years- old. Moreover, COPD is the third leading cause of death worldwide 2 and the fifth leading cause of years lived with disability 3.

There are several clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) in our country aiming to organise clinical care of this patients with COPD, and quality of care standards have been developed by Spanish National Respiratory Society (SEPAR), which have allowed clinicians to improve the quality of healthcare by summarising the scientific evidence and offering consistency in clinical proceedings4. In Spain, the most followed recommendations are the Spanish Guidelines for COPD -GesEPOC5(which were endorsed by both the patients associations and scientific societies involved in COPD care, but also by the Spanish Ministry of Health) and the GOLD strategy document for COPD management 6.

However, adherence to such recommendations is far away from ideal 7. Several studies have detected a deficient compliance and heavy deviations between professionals, which ultimately derives in unequal quality of care even in the same healthcare system.

Along with this previous experience, a recent audit of clinical records from Spanish respiratory specialist clinics has been carried out, kwon as EPOCONSUL study audit. This study has also shown a large variability in healthcare resources as well as patient profiles, adherence to national clinical guidelines and international recommendations and pharmacological and non-pharmacological management of patients with stable COPD. As a result of this findings, scientific societies with interest in healthcare attention to COPD have designed and implemented improvement strategies focusing clinical efforts in those areas where more deficiencies and variability were observed 8–11. For example, although spirometry is the keystone for COPD diagnosis 12, it is worldwide kwon that access to spirometry is limited for patients, as a recent survey in Spain highlighted showing low rates of spirometries performed in primary care centers in Spain13. This gives a room for improvement in COPD and its implementation in primary care.

Nevertheless, although COPD is a frequent cause of primary care consultation in Spain (more than 10% of visits in primary care are due to COPD) because of its high prevalence and chronic nature, there is scarce data about primary healthcare attention to COPD in Spain and particularly in Andalusia. This has led to this proposal of clinical audits of primary care consultations for COPD patients. An audit is a quality process aiming to improve patient healthcare and its results by a systematic review of disease management with explicit criteria and changes implementation.

Therefore, our aim was to audit the management and care for patients with COPD along the same healthcare system in primary care centers in Granada, to describe the overall adherence to guidelines and suggest changes to improve the management of this population.

2. Materials and Methods

This study is a clinical retrospective audit of clinical histories from patients with a diagnostic code for COPD recruited at 19 primary care centres for 12 months from March 2021 to March 2022. The distribution and selection of primary care centres was performed to reflect the entire population of Granada province. Collected information was retrospective for clinical data (clinical history and related documents) and concurrent for that scheduled attention in primary care as well as for primary healthcare resources.

To avoid selection bias, recruitment was performed prospectively including the first 10 patients each month scheduled for an appointment in the primary care centre with a diagnostic code for COPD

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Patients were included if they had fulfilled inclusion criteria: adults (men or women) aged more than 40 years old, diagnostic code in Andalusian clinical records (Diraya) in accordance with ICD-9 (Diagnostic codes 496, 492.8, 494.0, 491.20, 493.2), were current of former smokers of at least 10 pack- years, had a minimum follow up of 1 year, and had been assisted in a scheduled primary care appointment at inclusion date. Exclusion criteria included those without information related with COPD in the previous year, those involved in any clinical trial or research study related with COPD.

2.2. Outcomes

The main outcome of the study was to audit public healthcare for patients with COPD in primary care offices in Granada, evaluating variability and possible determinant factors. Secondary outcomes were to describe clinical profile of patients with COPD attended at primary care offices in Granada, to describe the quality of care for COPD patients and its variability, to evaluate the adherence and implementation of clinical guidelines for COPD and the performance of healthcare and to describe current available resources for COPD healthcare in the primary care level in Granada.

2.3. Study Variables

Collected data were divided in 4 groups: a) available resources and primary care centre model, b) clinical practice models, c) data regarding clinical process, patient profile and primary care consultation and d) evaluation of database quality.

2.4. Statistical Methods

A descriptive analysis of data values was performed for the entire study population as well as for each primary care centre and a comparison with mean values of similar centres. Statistical descriptives analysis were arranged using means, standard deviations for quantitative data and proportions for qualitative data.

Analysis of clinical practice models, types of primary care centres, seasonal and geographical variability were carried on to detect their influence in COPD healthcare.

Significance of variability by area/ primary care center were explored by Kruskal–Wallis or chi-square tests, depending on the nature of the variable between the different participant centers. Data was processed using the the Jamovi software (Jamovi version 2.3, The Jamovi project). P-values 0.05 will be considered statistically significant.

To evaluate the degree of clinical practice guidelines implementation, criteria of good clinical practice and quality standards were classified into 3 categories: clinical evaluation of the patient, disease evaluation, and therapeutic interventions.

2.5. Ethical Aspects

The study was evaluated by a Clinical Scientific Ethics Committee (CSEC) to guaranty all the ethical issues and safe confidentiality of included patients. During study evaluations principles of Helsinki Declaration on biomedical research were followed. In accordance with Biomedical Research Spanish Law 14/2007 dated 3/July/2007 and the Organic Law on Patient Data Protection, it was not deemed necessary to obtain informed consent from included patients as it is stated in this legislation that retrospective evaluation of data obtained in routinely clinical practice with research aims precludes informed consent obtanining. An autorisation to participate was requested to local healthcare authorities. All the primary care centre directors and healthcare authorities were informed of starting dates.

2.6. Patient Data Protection

Protocol procedures were performed accordingly with Spanish Law of Patient Data Protection. Data about participant were collected codified, keeping confidentiality according to current legislation. Patients were identified by correlative number which were assigned by computer application. Registry did not store personal data allowing a concrete patient identification. A dissociation mechanism was launched between clinical history information and data recorded in the study in order not to provide individual information. The study was registered in clinicaltrials.gov with the identifier NCT04691752.

3. Results

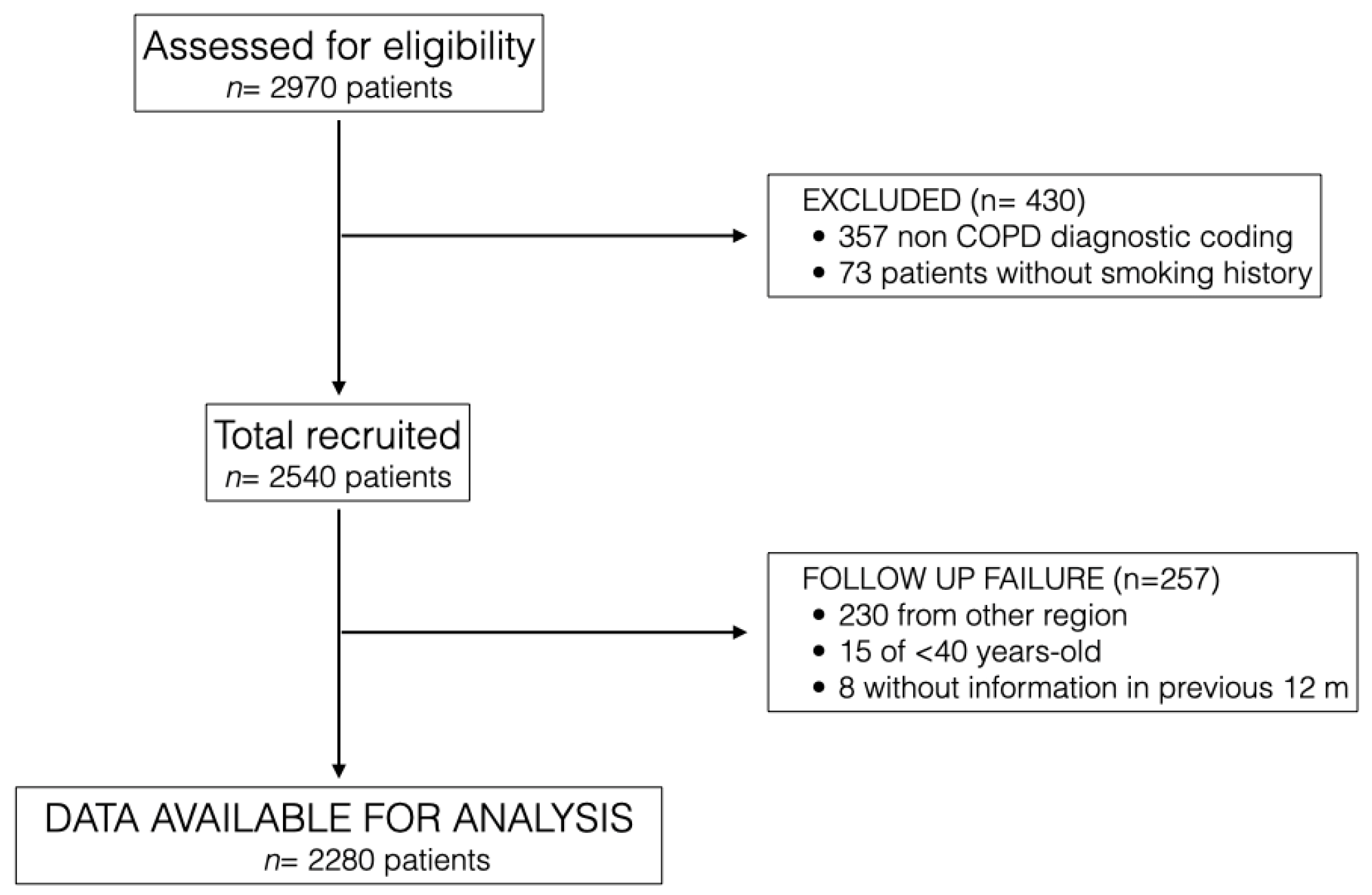

2970 patients attending primary care centres in Granada were detected and assessed for eligibility, of whom 2283 patients were finally included in the study from March 2021 to March 2022 at 19 primary care centres in Granada.

Figure 1 describes the flowchart of study participants. Main reasons for exclusion from the study were having a non-diagnostic code for COPD, lack of smoking history and patients attended at primary care centres who were from other regions of Spain.

Table 1 describes the overall characteristics of the 19 primary care centres including patients in the study. They were centres which attended more than 10000 people on average, most of them had resources for a basic COPD diagnosis (spirometry, blood test, chest X ray) and were authorised for medical internal residents’ formation in primary care.

Table 2 describes the overall characteristics of study population. It consisted of 7th decade men, with almost a quarter of them current smokers and moderate lung function impairment. Notably, there were very few patients with information about symptoms via CAT questionnaire and dyspnoea via mMRC. A very few of them had exacerbations in the previous year and a little proportion were admitted to the hospital due to severe episodes.

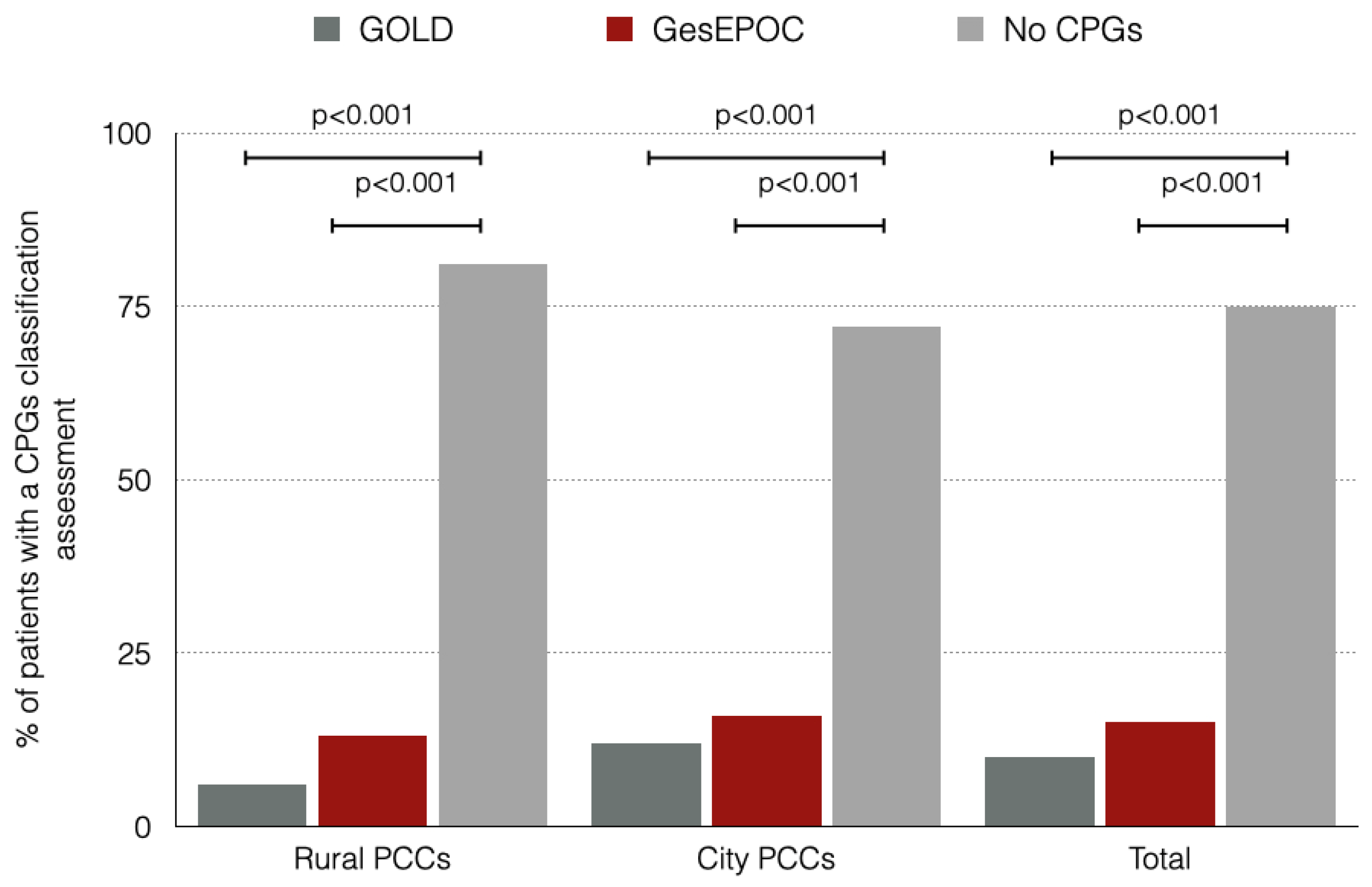

Figure 2 shows the proportion of patients included in the study who were assessed correctly by the CPGs divided by the location of the primary care center (PCC). Rural and city PCC patients had a low proportion of assessment by either GOLD o GesEPOC CPGs. There were no differences between both rural and city PCC in terms of correct assessment by CPGs.

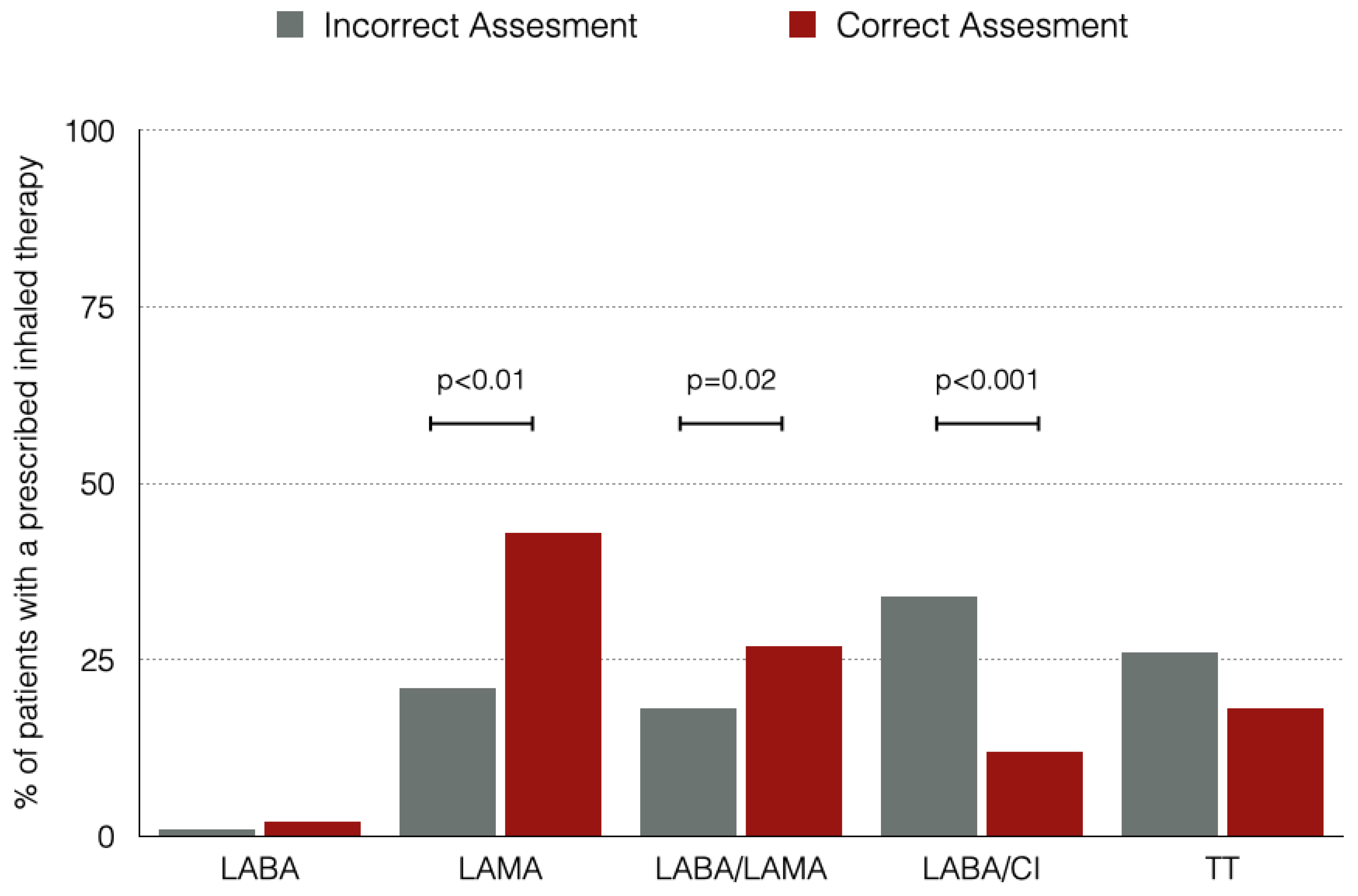

Figure 3 shows the prescribed inhaled therapies for the entire population regarding if a correct assessment based on the CPGs was made or not. The most frequent inhaled therapy was LAMA, and there were differences between groups in the use of long acting broncodilators (either monotherapy or dual bronchodilation) with those patients with an assessment based in CPGs being treated more frequently with bronchodilators and less frequently with LABA/ICs.

4. Discussion

The results of this study show that the management of patients with COPD does not usually follow up recommendations and this leads to an increase of the prescription of non-preferable inhaled therapies options for patients, which could determine not only a reduced perception of efficacy by the patients but an increase in long term adverse events and increased costs.

The results from our study do not differ from many other studies in our country or outside Spain, where a low adherence to CPGs has been detected14–16. This is not a sole problem in the field of primary care because similar problems have been detected in specialized care too, although in different magnitudes. Mainly the overall proportion of patients with a reported assessment of symptoms was very low, especially for the CAT questionnaire. This low adherence to symptom evaluation limits the overall adherence to CPGs and therefore it impacts the way a primary care physician prescribes inhaled therapies17,18.

Our results emphazise the need for a global quality standard for COPD assessment, with clear criteria for primary care physicians and easy orders to improve the management of this disease. While there are other ongoing initiatives 19regarding this issue, it will be needed a collaboration from medical authorities and healthcare directors to include some of them in the primary care deals in order to receive funding.

Our study has some limitations, the most important being a local study which could not reflect the overall quality of assessment of COPD patients. However, it should reflect at least the entire population of the province, which should not differ from other provinces with the same healthcare system. This means that our results could not be extrapolated to countries with different health systems.

In conclusion, our work indicate that there is an overall room for improvement regarding the management of COPD patients in primary care. There is a need for symptom registry in health records and a increased uptake of CPGs.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our work indicate that there is an overall room for improvement regarding the management of COPD patients in primary care. There is a need for symptom registry in health records and a increased uptake of CPGs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, JCMC. and BAN.; methodology, JCMC.; formal analysis, BAN.; data adquisition, AHS, ACG, PPH, LBC, JPS, ARG, EPO, JSFR, PJMR, PQM, AGP, MNN, and NBS.; writing—original draft preparation, BAN.; writing—review and editing, JCMC and BAN.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by a non-restricted grant from GSK.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was evaluated by a Clinical Scientific Ethics Committee (CSEC) to guaranty all the ethical issues and safe confidentiality of included patients (CEIC EPOCAP 112016). During study evaluations principles of Helsinki Declaration on biomedical research were followed. In accordance with Biomedical Research Spanish Law 14/2007 dated 3/July/2007 and the Organic Law on Patient Data Protection, it was not deemed necessary to obtain informed consent from included patients as it is stated in this legislation that retrospective evaluation of data obtained in routinely clinical practice with research aims precludes informed consent obtanining. An autorisation to participate was requested to local healthcare authorities. All the primary care centre directors and healthcare authorities were informed of starting dates.

Data Availability Statement

Data from this audit is available upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

JCMC reports fees from Abbot, Boehringer- Ingelheim, GSK, Lilly, Novartis and Teva outside the submitted work. AHS reports fees from Boehringer- Ingelheim, Laboratorios Ferrer and GSK outside the submitted work. ACG, PPH, LBC, JPS, ARG, EPO, JSFR, PJMR, PQM, AGP, MNN, NBS had nothing to declare. BAN reports personal fees from GSK, grants, personal fees and non-financial support from Novartis AG, personal fees and non-financial support from Boehringer Ingelheim, personal fees and non-financial support from Chiesi, grants, personal fees and non-financial support from Laboratorios Menarini, personal fees from Astra- Zeneca, outside the submitted work.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| COPD |

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. |

| CPG |

Clinical Practice Guideline |

| PCC |

Primary Care Centers |

| CAT |

COPD Assessment Test |

References

- Soriano, J.B.; Alfageme, I.; Miravitlles, M.; de Lucas, P.; Soler-Cataluña, J.J.; García-Río, F.; Casanova, C.; Rodríguez González-Moro, J.M.; Cosío, B.G.; Sánchez, G.; et al. Prevalence and Determinants of COPD in Spain: EPISCAN II. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2020, 57, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lozano, R.; Naghavi, M.; Foreman, K.; Lim, S.; Shibuya, K.; Aboyans, V.; Abraham, J.; Adair, T.; Aggarwal, R.; Ahn, S.Y.; et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012, 380, 2095–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassebaum, N.J.; Arora, M.; Barber, R.M.; A Bhutta, Z.; Brown, J.; Carter, A.; Casey, D.C.; Charlson, F.J.; Coates, M.M.; Coggeshall, M.; et al. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 315 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE), 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016, 388, 1603–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcázar-Navarrete, B.; Miñán, F.C.; Palacios, P.J.R. Clinical Guidelines in Asthma and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: How Useful Are They in Clinical Practice? Arch. De Bronc- 2018, 54, 117–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miravitlles, M.; Calle, M.; Molina, J.; Almagro, P.; Gómez, J.-T.; Trigueros, J.A.; Cosío, B.G.; Casanova, C.; López-Campos, J.L.; Riesco, J.A.; et al. Actualización 2021 de la Guía Española de la EPOC (GesEPOC). Tratamiento farmacológico de la EPOC estable. Arch. De Bronc- 2021, 58, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogelmeier, C. F.; Criner, G. J.; Martínez, F. J.; Anzueto, A.; Barnes, P. J.; Bourbeau, J.; Celli, B. R.; Chen, R.; Decramer, M.; Fabbri, L. M.; Frith, P.; Halpin, D. M. G.; López Varela, M. V.; Nishimura, M.; Roche, N.; Rodríguez-Roisin, R.; Sin, D. D.; Singh, D.; Stockley, R.; Vestbo, J.; Wedzicha, J. A.; Agustí, A. Informe 2017 de La Iniciativa Global Para El Diagnóstico, Tratamiento y Prevención de La Enfermedad Pulmonar Obstructiva Crónica: Resumen Ejecutivo de GOLD. Arch Bronconeumol 2017, 53, 128–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murad, M.H. Clinical Practice Guidelines: A Primer on Development and Dissemination. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2017, 92, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, M.C.; Soriano, J.B.; Campos, J.L.L.; Soler-Cataluña, J.J.; Navarrete, B.A.; Moro, J.M.R.G.; Miravitlles, M.; Barrecheguren, M.; Ferrer, M.E.F.; Hermosa, J.L.R.; et al. Testing for alpha-1 antitrypsin in COPD in outpatient respiratory clinics in Spain: A multilevel, cross-sectional analysis of the EPOCONSUL study. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0198777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, M.C.; Hermosa, J.L.R.; Soler-Cataluña, J.J.; López-Campos, J.L.; Navarrete, B.A.; Soriano, J.B.; Gónzalez-Moro, J.M.R.; Ferrer, M.E.F.; Miravitlles, M. Atención médica según el nivel de riesgo y su adecuación a las recomendaciones de la guía española de la enfermedad pulmonar obstructiva crónica (EPOC) (GesEPOC): Estudio EPOCONSUL. Arch. De Bronc- 2018, 54, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- On behalf of the EPOCONSUL Study; Rubio, M.C.; López-Campos, J.L.; Soler-Cataluña, J.J.; Navarrete, B.A.; Soriano, J.B.; González-Moro, J.M.R.; Ferrer, M.E.F.; Hermosa, J.L.R. Variability in adherence to clinical practice guidelines and recommendations in COPD outpatients: a multi-level, cross-sectional analysis of the EPOCONSUL study. Respir. Res. 2017, 18, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, M.C.; Navarrete, B.A.; Soriano, J.B.; Soler-Cataluña, J.J.; González-Moro, J.-M.R.; Ferrer, M.E.F.; Lopez-Campos, J.L. Clinical audit of COPD in outpatient respiratory clinics in Spain: the EPOCONSUL study. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2017, ume 12, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Río, F.; Calle, M.; Burgos, F.; Casan, P.; del Campo, F.; Galdiz, J.B.; Giner, J.; González-Mangado, N.; Ortega, F.; Maestu, L.P. Espirometría. Arch. De Bronc- 2013, 49, 388–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Campos, J.L.; Soriano, J.B.; Calle, M. A Comprehensive, National Survey of Spirometry in Spain. Chest 2013, 144, 601–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vachon, B.; Giasson, G.; Gaboury, I.; Gaid, D.; De Tilly, V.N.; Houle, L.; Bourbeau, J.; Pomey, M.-P. Challenges and Strategies for Improving COPD Primary Care Services in Quebec: Results of the Experience of the COMPAS+ Quality Improvement Collaborative. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2022, ume 17, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steurer-Stey, C.; Dallalana, K.; Jungi, M.; Rosemann, T. Management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Swiss primary care: room for improvement. 2012, 20, 365–73. [Google Scholar]

- on behalf of the COACH study investigators; Abad-Arranz, M.; Moran-Rodríguez, A.; Balaguer, E.M.; Velasco, C.Q.; Polo, L.A.; Palomo, S.N.; Rey, J.G.; Vargas, A.M.F.; Requena, A.H.; et al. Community Assessment of COPD Health Care (COACH) study: a clinical audit on primary care performance variability in COPD care. BMC Med Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miravitlles, M.; Solé, A.; Aguilar, H.; Ampudia, A.; Costa-Samarra, J.; Mallén-Alberdi, M.; Nieves, D. Economic Impact of Low Adherence to COPD Management Guidelines in Spain. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2021, ume 16, 3131–3143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, S.; Wright, A.; Hartgers-Gubbels, E.S.; Hechtner, M.; Clark, B.; Wright, C.; Langham, S.; Buhl, R. Costs and Clinical Consequences of Compliance with COPD GOLD Recommendations or National Guidelines Compared with Current Clinical Practice in Belgium, Germany, Sweden, and the United States. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2022, ume 17, 2149–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullen, R.; Miravitlles, M.; Sharma, A.; Singh, D.; Martinez, F.; Hurst, J.R.; Alves, L.; Dransfield, M.; Chen, R.; Muro, S.; et al. CONQUEST Quality Standards: For the Collaboration on Quality Improvement Initiative for Achieving Excellence in Standards of COPD Care. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2021, ume 16, 2301–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).