1. Introduction

The enduring success of implant prosthodontics is associated with precise adaptation between the prosthetic components, aesthetics, resistance to masticatory movements, and harmony in the stomatognathic system [

1]. Micromovements occur in the external hexagon (HE) connection as a consequence of the hexagon design, low resistance to masticatory loads, microgaps, bone resorption and difficulty in the rehabilitation procedure [

2,

3]. The Morse cone is widely used in rehabilitation due to its excellent sealing capacity, lower stress, greater stability between the prosthetic component and the implant and reduction of microspaces at the interface [

2,

3,

4].

Prosthetic components called Ti-base abutments are prefabricate ted abutments known as rehabilitation components and have a geometry that is easy to cement and screw in the same prosthesis, with the exact implant-abutment precision provided by the manufacturer [

5]. The advent of CAD/CAM, such as the titanium-based abutment [Ti-base), facilitates digital restoration design and milling of prosthetic restorations that can be cemented extraorally and then screwed to the implant [

6,

7].

Nowadays, the usual CAD/CAM systems provide a vast library of databases for the agile manufacture of restorations on titanium-based abutments [

5]. Among the advantages of the Ti-based technique found in the scientific literature, we can mention the customization of the emergence profile, time saving with reduced costs, hybrid retention mechanism [cemented and screwed) that makes it possible to remove excess cement and achieve satisfactory photopolymerization of the restoration margins before screwing it to the implant [

7,

8].

Calculated survival rates for implant-supported single crowns are 97% for porcelain-fused-to-metal and 90% to 96% for zirconia crowns after observation periods of 5 and 10 years, respectively [

9,

10]. Given its chemical inertness and lack of a glass phase, satisfactory bonding to zirconia has been clinically challenging. Bonding efficacy to zirconia is maximized when airborne particle abrasion, silica tribochemical coating, or etching with 10-methacryloyloxydecyl dihydrogen phosphate (MDP) monomer are used [

11,

12,

13].

The choice of cement type is important for successful cemented implant restorations. Temporary cement is a safe alternative for implant crowns compared to conventional and resin-based cement [

14]. The cement should be suitable for retaining the prosthesis, but at the same time, it should allow dentists to remove the restoration easily and safely [

15]. However, in some cases, such as a small abutment height, it is necessary to select cement with higher bond strength [

16]. Resin-based cements are an excellent choice, as they provide high levels of retention and entrapment with low microleakage [

15]. Surface treatments tend to improve the adhesion of zirconia to resin cement in vitro; factors such as temperature variations, saliva and mechanical fatigue can affect the longevity of the bond between zirconia crowns and resin cement [

17,

18]. Aging, such as water storage, exposure to acids, thermocycling and mechanical loading, are methods that evaluate the stability of the bonded interface [

19,

20,

21].

The aim of this study was to analyze the influence of the type of cement and the impact of aging on the retention of zirconia crowns cemented on a titanium-base abutment in external hexagon and morse taper implant connections. The first null hypothesis is that there would be no difference in retention strength before and after mechanical cycling. The second null hypothesis is that no difference would exist between the prosthetic connections evaluated. Finally, the third null hypothesis is that there would be no difference between the cements used.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This study divided the samples according to implant platform [EH or MT), cement type [temporary or definitive), and mechanical aging (with or without). Group I MT: CH + without aging (n=20); Group II MT: CH + aging (n=20); Group III MT: RC + without aging (n=20); Group IV MT: RC + aging (n=20); Group V EH: CH + without aging (n=20); Group VI EH: CH + aging (n=20); Group VII EH: RC + without aging (n=20); Group VIII EH: RC + aging (n=20).

2.2. Crowns Fabrication

A typodont with an upper right second premolar missing and a Biofit External Hex Implant 3.75x11.5 mm (DSP Biomedical, Campo Largo, PR, Brazil) in position was scanned with the CS3600 scanner (Carestream, Atlanta, GA, USA), using a Biofit scanbody (DSP Biomedical, Campo Largo, PR, Brazil), adapted directly to the implant platform. Using the obtained file, a full-coverage crown was designed using EXOCAD software (Exocad, Darmstadt, Germany) (

Figure 2). After the confection of this crown, it was cemented on the Ti-Base Standard HE 5.0x4.7x1.0 mm and Tibase Standard CMI 5.0x4.7x1.5 mm abutments (DSP Biomedical, Campo Largo, PR, Brazil).

Understanding that the Ti-Base abutment has the same geometry and dimensions for both External Hexagon and Morse Taper implants, a single design was used to manufacture 120 (one hundred and twenty) milled zirconia crowns (ProtMat Infra Translucency 35%; Protmat Materiais Avançados Ltda, Juiz de Fora, MG, Brazil), using the InlabCAM software (Dentsply Sirona, Charlotte, NC, USA) and the MCX5 milling machine (Dentsply Sirona, Charlotte, NC, USA) (

Figure 1). After milling, the crowns were sintered in the Inlab Profire Sirona furnace.

Figure 1.

Milled full-coverage zirconia crowns.

Figure 1.

Milled full-coverage zirconia crowns.

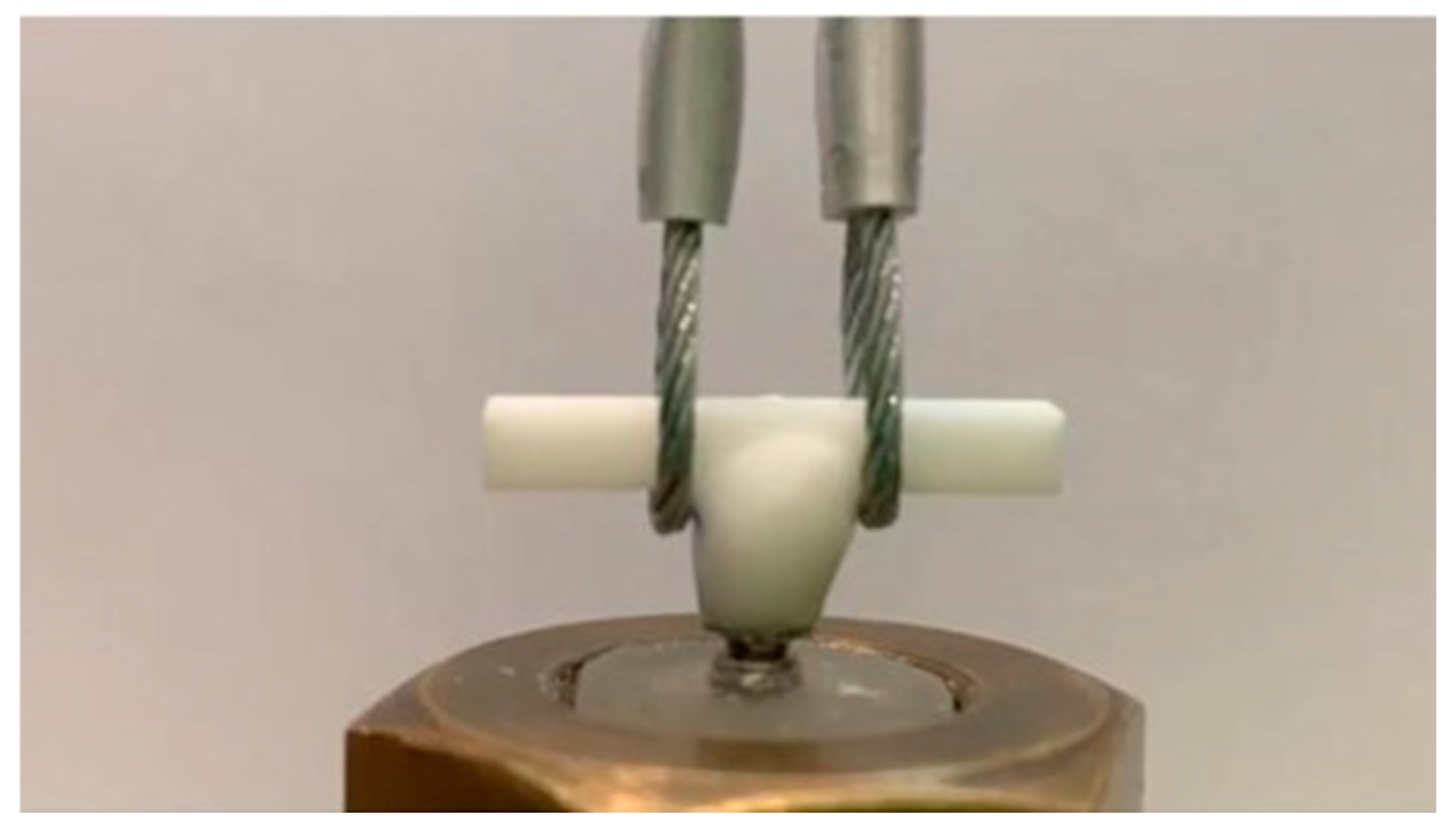

Figure 2.

Pull-out testing is being performed in the universal testing machine.

Figure 2.

Pull-out testing is being performed in the universal testing machine.

2.3. Specimens’ Fabrication

A total of 20 Morse taper implants and 20 external hexagon implants (3.75x11.5 mm; DSP Biomedical, Campo Largo, PR, Brazil) were positioned in cylindrical blocks of self-curing acrylic resin (JET Clássico, Campo Limpo Paulista, SP, Brazil). A custom metal device measuring 4.5 cm wide x 4.5 cm long x 1.5 cm high with a hole diameter of 1.8 cm was fabricated. A surveyor (B2; Bioart, São Carlos, SP, Brazil) was used to position the external hexagon implant with its prosthetic platform located 3 mm above the upper limit of the metal device, which simulates the position of the implant in relation to the bone level (ISO 14801, of 11/01/2016). For the Morse taper implant, the prosthetic platform was positioned 1 mm above the upper limit of the metal device, as indicated by the manufacturer.

2.4. Cementation Procedures

All crowns and abutments were cleaned using an ultrasonic bath containing 96% ethanol for 5 minutes, washed with distilled water, and dried [

22]. According to the manufacturer's instructions, all the Ti-base abutments were installed in their respective implants and torqued to 30 N/cm. Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) tape was used to fill the screw access of the abutments. For Groups I and V, the crowns were cemented with Calcium Hydroxide temporary cement (Hydro C; Dentsply Sirona, Charlotte, NC, USA) with a 1:1 catalyst and base ratio, manipulated for 10 s, and cemented under a pressure of 5 kg for 5 minutes.

The same crowns for Groups I and V were used for Groups II and VI. For this, the remaining temporary cement was removed from the inside of the zirconia crowns with 50-μm aluminum oxide particles airborne-particle abrasion under a pressure of 1.5 bar at a distance of 1 cm at 45° for 15 s. The crowns were rinsed with 70% isopropyl alcohol for 30 s, then washed with water for 30 s, and cleaned in an ultrasonic bath (70% isopropyl alcohol, 15 min), rewashed with water for 30 s and dried with air [

22]. A dentin curette was used to remove residual cement from the abutments and immersed in an ultrasonic bath with 70% isopropyl alcohol for 15 min [

22,

23]. The cleaned abutments were rinsed in distilled water, dried, and visually inspected to ensure complete cement removal [

23]. As mentioned above, the abutments were placed and torqued, and the cementation procedures were done.

For the definitive cement groups (groups III, IV, VII, VIII), the new crowns were prepared with 50-μm aluminum oxide particles airborne-particle abrasion (particle size; Polidental Ind., Cotia, São Paulo, Brazil) at a distance of 10 mm for 10 s and a pressure of 2 bars; cleaned in an ultrasonic bath with distilled water for 5 min and vigorously air-dried for 20 s. A universal adhesive (Scotchbond Universal; 3M ESPE; Saint Paul, Minnesota, USA) was applied with a microbrush to the interior of the crowns and the surface of the Ti-base abutments for 20 s, and the excess was removed by air-drying for 5 s. To cement the crowns to the Ti-base abutments, a dual resin cement (RelyX Ultimate; 3M ESPE; Saint Paul, Minnesota, USA) was mixed according to the manufacturer's instructions and applied directly to the internal surface of the zirconia crown and the entire surface of the Ti-base abutment. The crowns were positioned and maintained in position by finger pressure. Excess cement was removed from the margins with a cotton ball. Then, light activation was performed with a curing light (Valo; Ultradent Products Inc., South Jordan, Utah, USA) on each surface for 20 s, with the standard power mode 1000 mW/cm2.

2.5. Mechanical Aging

For the aged groups (groups II, IV, VI, VIII), a mechanical loading was Applied with a 6 mm diameter metal piston for 240,000 cycles at 60 mm/min with a load of 50 N, with an electromechanical fatigue machine – MSFM (HM Electrical Solutions, Araçatuba, SP, Brazil).

2.6. Pull-Out Test

For the pull-out testing, all specimens were fixed in a rigid fixture to the universal testing machine (EMIC DL-3000, São José dos Pinais, PR, Brazil), and a steel cable was attached to each end of the occlusal bar (

Figure 2). A tensile load (0.5 mm/min) was applied to the long axis of the tooth and recorded in Newtons (N). After the crown removal, the failure mode according to the cement location was recorded by a calibrated observer who examined the crown and the Ti-base abutment to identify the nature of failure according to the criteria in

Table 1. Data analysis was initially assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Then, the three-way ANOVA parametric test with repeated measures was performed. Tukey's test was used as a post-hoc (P < 0.05).

3. Results

The distribution of quantitative data was considered normal by the Shapiro- Wilk test (p>0.05). Then, the parametric ANOVA test with three repeated measures was performed, in which a statistically significant difference was observed for the factors “Aging”, “Implant”, and “Cement” isolated, with the value of p<0.001 for the different factors.

Table 2 shows a statistical significance for the variable “aging” alone (P<.001). Mechanical aging, regardless of the implant connection or cement type, decreased the retention strength in the samples. However, it was not possible to observe a statistical difference when “aging” and “implant platforms” were evaluated together (P=0.254); “aging” and “cement” (P=0.066), or “aging”, “implant platforms” and “cement” (P=0.646).

Table 3 shows a statistically significant difference for the variables “implant platforms” and “cement” evaluated (P<.001). The Morse taper implants presented a statistically significantly higher average retention strength than the external hexagon implants, independently of the mechanical cycling and the type of cement. Regarding the type of cement, resin cement also presented a statistically significantly higher resistance force than calcium hydroxide cement, regardless of mechanical cycling and the type of implant.

Table 4 shows the average value (in N) of the retention strength for the implant platforms and cement types before and after aging. Thus, it was possible to verify that Groups III and IV presented the highest value compared to the other groups (565 N before mechanical aging and 491 N after mechanical aging). The post-hoc test showed that the highest statistically significant pull-out force values were observed before aging (p<0.001) for MT implants (p<0.001) using the definitive cement (p<0.001).

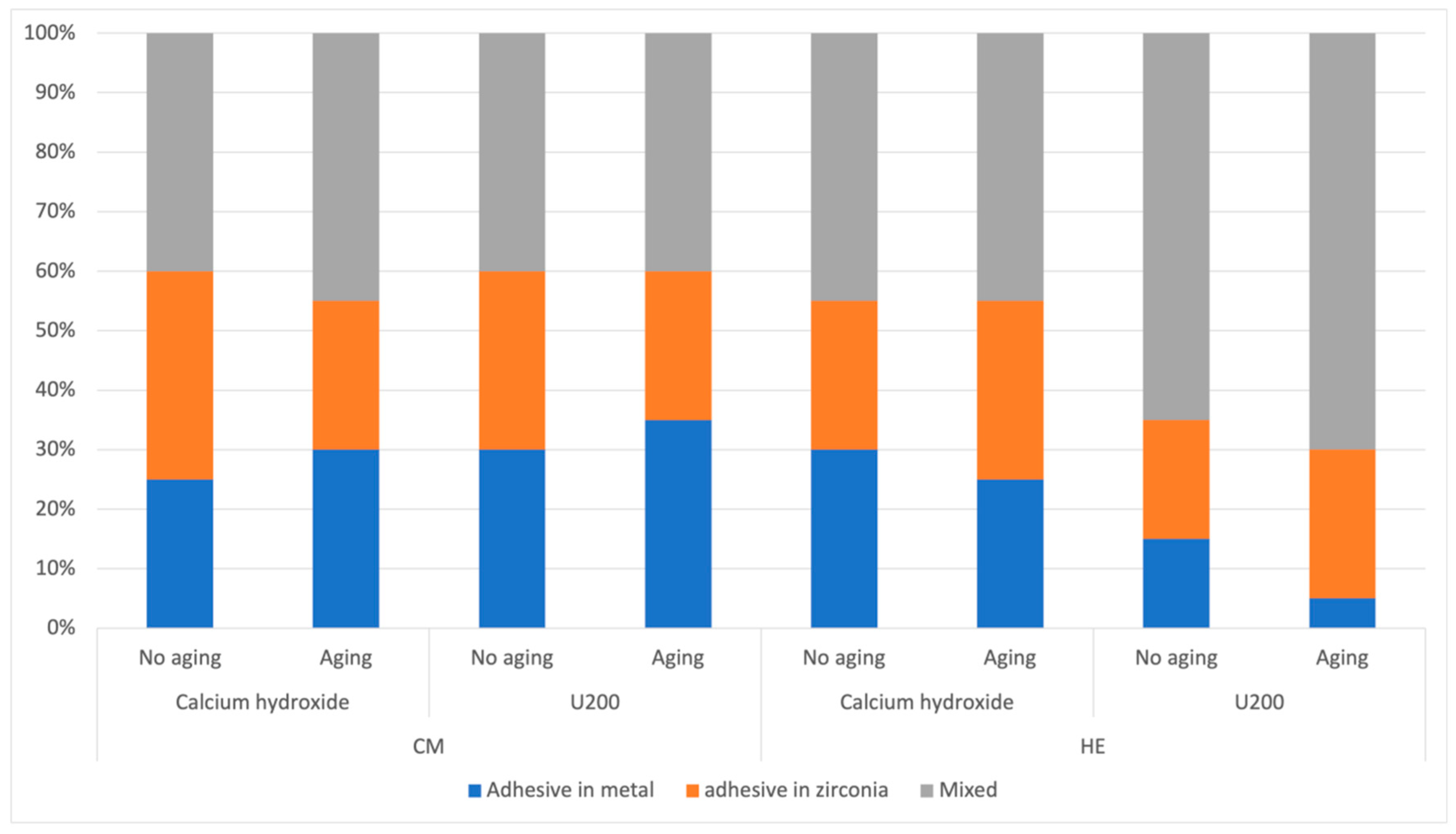

Was it possible to observe an increase in the amount of mixed failure after mechanical aging (

Figure 3). When comparing the implant types, it is possible to verify that the average mixed failure with the Calcium Hydroxide cement remained similar among the Morse taper implants. When comparing the resin cement between the implant platforms, it was possible to observe an increase in the external hexagon groups compared to the Morse taper groups. It was also likely observed that the metal failure in the external hexagon group with resin cement decreased compared to the other groups.

4. Discussion

Based on this study's findings, the first null hypothesis that there would be no significant difference in retention strength before and after mechanical cycling was rejected. The second null hypothesis, which was that no statistical difference would exist with implants with External Hexagon and Morse Taper, was also rejected. Finally, the third null hypothesis that there would be no statistically significant difference between the cements was also rejected.

Mechanical aging, regardless of the implant connection or cement type, decreased the retention strength of the samples. This result agrees with other studies demonstrating that mechanical aging influences the retention strength [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. No studies were found in the literature comparing the retention strength of crowns on Tibase abutments in Morse taper and external hexagon implants. The studies found to evaluate the retention strength compared factors such as types of cement [

24,

25,

28,

30], surface treatment, and height of Ti-base abutments [

24,

30].

The Morse taper and external hexagon comparison performed better in the Morse taper groups. This is due to better stress distribution and stability between the abutment and implant, as well as the reduction of micro spaces in the interface of the Morse taper system [

2,

3,

4,

29]. The presence of micro-movements in the external hexagon connection has been reported in scientific literature due to the size of the hexagon, low resistance to masticatory loads, more significant micro gaps, alveolar bone resorption, and rehabilitation failure [

2,

3]. Some authors concluded that the micro space in the Morse taper connection was smaller when compared to the external hexagon connection [

31,

32].

Another factor evaluated was the impact of the type of cement. The resin cement presented retention values higher than the temporary cement for both implant connections. The results of this study are corroborated by other studies, where the resin cement presented higher retention values than the temporary cement [

5,

24,

30,

33]. However, the higher risk of crown fracture with resin cement was mentioned [

24]. The superiority of the resin cement is due to its better adhesive property and the surface treatment performed on the crown and the Ti-base abutment. Kemarly et al. [

34] studied the effect of mechanical and chemical treatment of the Ti-based abutment surface on the bond strength of a lithium disilicate framework. They found that chemical surface treatment with Monobond Plus, compared to mechanical treatment with CoJet (silicatization) or abrasion of airborne aluminum oxide particles, resulted in higher retention strength, and that without mechanical treatment of the coated surface, in lower retention strength, regardless of the chemical surface treatments. Using three resin-based luting agents, Gehrke et al. [

35] evaluated the retention of CAD/CAM-fabricated zirconia abutments after artificial aging under simulated oral conditions. They concluded that the use of resin-based luting agents in combination with abrasion of the titanium abutment and zirconia copings led to stable retention. Finally, Zahoui et al. [

36] established a more effective cementation protocol for cementing CAD/CAM zirconia crowns on Ti-based abutments. They studied the influence of abutment height, cement type, and surface pretreatment. They concluded that there is a direct relationship between Ti-based height, micromechanical or chemical pretreatment, and conventional adhesive in improving the retention of zirconia crowns.A higher percentage of the mixed failure pattern was found for all groups and can be justified by the convergent anatomy of the Titanium-base abutment [

37]. The angulation of the abutment base up to its half is almost parallel, increasing the convergence angle from its half to the most occlusal portion. When comparing the type of cementation failure with the implant types, it is possible to verify that the mixed failure remained similar when cemented with calcium hydroxide cement. When resin cement was used, it was possible to observe an increase in mixed failures in the external hexagon groups compared to the Morse taper groups. This higher percentage of mixed failure in the external hexagon implants is justified by the inferior biomechanical properties of this type of connection compared to the Morse taper connection31. Previous studies [

31,

32,

38] have demonstrated the higher presence of micro spaces in external hexagon implants than Morse taper implants, which can generate more significant movements in the abutment/implant assembly, leading to mixed cementation failure. The intimate contact of the prosthetic component to the Morse taper implant, also known as “cold welding”, generates higher stability of the assembly [

29,

31,

32,

38] justifying the lower percentage of mixed failure compared to the external hexagon implant.

Although it is an in vitro study, the results of this study help to gain knowledge about Titanium-base abutments, types of restorative materials, cements, and types of implant connections to increase the longevity of treatments using this type of abutment in clinical conditions. It is necessary to analyze the performance of different restorative materials and cement attached to the Ti-base abutment in different implant connections. Therefore, additional in vitro and in vivo investigations around the Ti-base abutment should be conducted to understand hybrid restorations properties and retention mechanisms in different prosthetic connections.

5. Conclusions

Mechanical aging decreased the retention force of restorations cemented on the Titanium-base abutment.

Zirconia crowns cemented on the Titanium-base abutment with resin cement on Morse taper implants presented higher retention force measured against external hexagon implants.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology and validation, A.L.M.M, D.M.S. and M.C.G.; formal analysis, A.L.M.M., D.M.S. and M.C.G.; investigation, resources, C.C.L., A.L.M.M. and C.L.M.M.N. data curation, C.C.L. and N.V.A.M. writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, R.V.M, S.B.B., C.L.M.M.N. and M.C.G.; supervision, W.G.A. and M.C.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Tonella BP, Pellizzer EP, Ferraço R, et al. Photoelastic analysis of cemented or screwed implant-supported prostheses with different prosthetic connections. Journal of Oral Implantology. 2011 Aug;37(4):401–10. [CrossRef]

- Zarone F, Sorrentino R, Traini T, Di lorio D, et al. Fracture resistance of implant-supported screw- versus cement-retained porcelain fused to metal single crowns: SEM fractographic analysis. Dental Materials. 2007 Mar;23(3):296–301. [CrossRef]

- Pita MS, Anchieta RB, Barão VAR, Garcia IR, et al. Prosthetic platforms in implant dentistry. Journal of Craniofacial Surgery. 2011 Nov;22(6):2327–31. [CrossRef]

- Goiato MC, Shibayama R, Filho HG, De Medeiros RA, et al. Stress distribution in implantsupported prostheses using different connection systems and cantilever lengths: Digital photoelasticity. J Med Eng Technol. 2016 Feb 17;40(2):35–42. [CrossRef]

- Lopes AC de O, Machado CM, Bonjardim LR, Bergamo ETP, et al. The Effect of CAD/CAM Crown Material and Cement Type on Retention to Implant Abutments. Journal of Prosthodontics. 2019 Feb 1;28(2):e552–6. [CrossRef]

- Burkhardt F, Pitta J, Fehmer V, Mojon P, et al. Retention forces of monolithic CAD/CAM crowns adhesively cemented to titanium base abutments—effect of saliva contamination followed by cleaning of the titanium bond surface. Materials. 2021 Jun 2;14(12). [CrossRef]

- Cardoso KB, Bergamo ETP, De Cruz VM, Ramalho IS, et al. Three-dimensional misfit between ti-base abutments and implants evaluated by replica technique. Journal of Applied Oral Science. 2020;28:1–5. [CrossRef]

- Bergamo ETP, Zahoui A, Ikejiri LLA, Marun M, et al. Retention of zirconia crowns to ti-base abutments: Effect of luting protocol, abutment treatment and autoclave sterilization. J Prosthodont Res. 2021;65(2):171–5. [CrossRef]

- Pjetursson BE, Valente NA, Strasding M, Zwahlen M, et al. A systematic review of the survival and complication rates of zirconia-ceramic and metal-ceramic single crowns. Vol. 29, ClinicalOral Implants Research. Blackwell Munksgaard; 2018. p. 199–214. [CrossRef]

- Larsson C, Wennerberg A. The Clinical Success of Zirconia-Based Crowns: A Systematic Review. Int J Prosthodont. 2014 Jan;27(1):33–43.

- Inokoshi M, De Munck J, Minakuchi S, Van Meerbeek B. Meta-analysis of bonding effectiveness to zirconia ceramics. Vol. 93, Journal of Dental Research. SAGE Publications Inc.; 2014. p. 329–34.

- Inokoshi M, Shimizu H, Nozaki K, Takagaki T, et al. Crystallographic and morphological analysis of sandblasted highly translucent dental zirconia. Dental Materials. 2018 Mar 1;34(3):508–18.

- Ruales-Carrera E, Cesar PF, Henriques B, Fredel MC, et al. Adhesion behavior of conventional and high-translucent zirconia: Effect of surface conditioning methods and aging using na experimental methodology. Journal of Esthetic and Restorative Dentistry. 2019;31(4):388–97.

- Schwarz S, Schröder C, Corcodel N, Hassel AJ, et al. Retrospective Comparison of Semipermanent and Permanent Cementation of Implant-Supported Single Crowns and FDPs with Regard to the Incidence of Survival and Complications. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2012 May;14(SUPPL. 1).

- Almehmadi N, Kutkut A, Al-Sabbagh M. What is the Best Available Luting Agent for Implant Prosthesis? Vol. 63, Dental Clinics of North America. W.B. Saunders; 2019. p. 531–45.

- Gómez-Polo M, Ortega R, Gómez-Polo C, Celemin A, et al. Factors Affecting the Decision to Use Cemented or Screw-Retained Fixed Implant-Supported Prostheses: A Critical Review. Int J Prosthodont. 2018 Jan;31(1):43–54.

- Shahin R, Kern M. Effect of air-abrasion on the retention of zirconia ceramic crowns luted with different cements before and after artificial aging. Dental Materials. 2010 Sep;26(9):922–8.

- Ehlers V, Kampf G, Stender E, Willershausen B, et al. Effect of thermocycling with or without 1 year of water storage on retentive strengths of luting cements for zirconia crowns.

- Amaral FLB, Colucci V, Palma-Dibb RG, Corona SAM. Assessment of in vitro methods used to promote adhesive interface degradation: A critical review. Journal of Esthetic and Restorative Dentistry. 2007 Dec;19(6):340–53.

- Heintze, SD. Crown pull-off test (crown retention test) to evaluate the bonding effectiveness of luting agents. Vol. 26, Dental Materials. 2010. p. 193–206.

- Egilmez F, Ergun G, Cekic-Nagas I, Vallittu PK, et al. Does artificial aging affect mechanical properties of CAD/CAM composite materials. J Prosthodont Res. 2018 Jan 1;62(1):65–74.

- Bajoghli F, Fathi A, Ebadian B, Jowkar M, et al. The effect of different methods of cleansing temporary cement (with and without eugenol) on the final bond strength of implantsupported zirconia copings after final cementation: An in vitro study [Internet]. Vol. 1, Dental Research Journal. 2023. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/journals/1480.

- Sarfaraz H, Hassan A, Kamalakanth Shenoy K, Shetty M. An in vitro study to compare the influence of newer luting cements on retention of cement-retained implant-supported prosthesis. The Journal of Indian Prosthodontic Society. 2019 Apr 1;19(2):166–72.

- Volkmann H, Rauch A, Koenig A, Schierz O. Pull-off Force of Four Different Implant Cements Between Zirconia Crowns and Titanium Implant Abutments in Two Different Abutment Heights. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2022 May;42(3):e67–74.

- Dähne F, Meißner H, Böning K, Arnold C, et al E. Retention of different temporary cements tested on zirconia crowns and titanium abutments in vitro. Int J Implant Dent. 2021 Dec;7(1).

- Bagegni A, Weihrauch V, Vach K, Kohal R. The Mechanical Behavior of a Screwless Morse Taper Implant–Abutment Connection: An In Vitro Study. Materials. 2022 May 1;15(9).

- Alevizakos V, Mosch R, Mitov G, Othman A, et al. Pull-off resistance of a screwless implantabutment connection and surface evaluation after cyclic loading. Journal of Advanced Prosthodontics. 2021 Jun 1;13(3):152–9.

- Bagegni A, Borchers J, Beisel S, Patzelt SBM, et al. Bonding Strength of Various Luting Agents between Zirconium Dioxide Crowns and Titanium Bonding Bases after Long-Term Artificial Chewing. Materials. 2023 Dec 1;16(23).

- Feitosa PCP, de Lima APB, Silva-Concílio LR, Brandt WC, et al. Stability of external and internal implant connections after a fatigue test. Eur J Dent. 2013;7(3):267–71.

- Silva CEP, Soares S, Machado CM, Bergamo ETP, et al. Effect of CAD/CAM abutment height and cement type on the retention of zirconia crowns. Implant Dent. 2018;27(5):582–7.

- Vinhas AS, Aroso C, Salazar F, López-Jarana P, et al. Review of the mechanical behavior of different implant–abutment connections. Vol. 17, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. MDPI AG; 2020. p. 1–20.

- Bittencourt ABBC, de Moraes Melo Neto CL, Penitente PA, Pellizzer EP, et al. Comparison of the Morse Cone Connection with the Internal Hexagon and External Hexagon Connections Based on Microleakage - Review. Prague Med Rep. 2021;122(3):181–90.

- Kapoor R, Singh K, Kaur S, Arora A. Retention of implant supported metal crowns cemented with different luting agents: A comparative invitro study. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research. 2016 Apr 1;10(4):ZC61–4.

- Kemarly K, Arnason SC, Parke A, Lien W, et al. Effect of various surface treatments on Ti-base coping retention. Oper Dent. 2020 Jul 1;45(4):426–34.

- Gehrke P, Alius J, Fischer C, Erdelt KJ, et al. Retentive strength of two-piece CAD/CAM zircônia implant abutments. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2014;920–5.

- Zahoui A, Bergamo ETP, Marun MM, Silva KP, et al. Cementation Protocol for Bonding Zirconia Crowns to Titanium Base CAD/CAM Abutments.

- Strazzi-Sahyon HB, Bergamo ETP, Gierthmuehlen PC, Lopes ACO, et al. In vitro assessment of the effect of luting agents, abutment height, and fatigue on the retention of zirconia crowns luted to titanium base implant abutments.

- Larrucea Verdugo C, Jaramillo Núñez G, Acevedo Avila A, Larrucea San Martín C. Microleakage of the prosthetic abutment/implant interface with internal and external connection: In vitro study. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2014;25(9):1078–83.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).