Submitted:

24 April 2025

Posted:

25 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

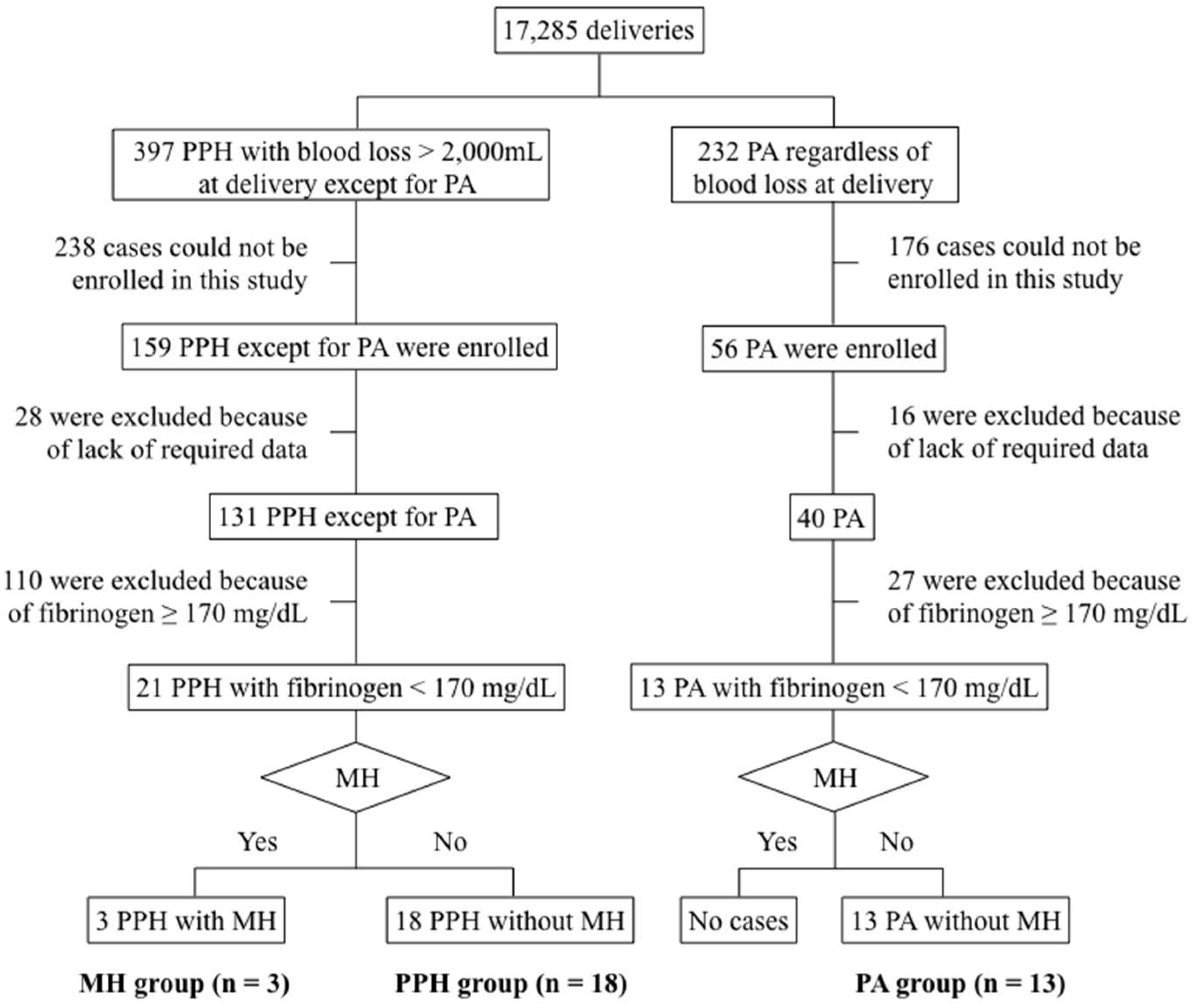

2.1. Design and Study Population

2.2. Clinical Data and Laboratory Tests

2.3. Validation of the Boundary Criterion for Predicting Hematuria and Comparison of Coagulation–Fibrinolytic Activation in Each Group

2.4. Data Analysi

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AFE | Amniotic fluid embolism |

| C/S | Cesarean section |

| DAMPs | Damage-associated molecular patterns |

| DIC | Disseminated intravascular coagulation |

| FDP | Fibrin/fibrinogen degradation products |

| FFP | Fresh frozen plasma |

| HDP | Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy |

| INR | International normalized ratio |

| ISTH | International Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis |

| MH | Macroscopic hematuria |

| NHO | National Hospital Organization |

| PA | Placental abruption |

| PIC | Plasmin-α2–plasmin inhibitor complex |

| PPH | Postpartum hemorrhage |

| RCC | Red cell concentrates |

| TAT | Thrombin–antithrombin complex |

References

- Taylor, Jr, F. B.; Toh, C.H.; Hoots, W.K.; Wada, H.; Levi, M.; Scientific Subcommittee on Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC) of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH). Towards definition, clinical and laboratory criteria, and a scoring system for disseminated intravascular coagulation. Thromb. Haemost. 2001, 86, 1327–1330. [Google Scholar]

- Gando, S.; Saitoh, D.; Ogura, H.; Mayumi, T.; Koseki, K.; Ikeda, T.; Ishikura, H.; Iba, T.; Ueyama, M.; Eguchi, Y.; Ohtomo, Y.; Okamoto, K.; Japanese Association for Acute Medicine Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (JAAM DIC) Study Group. Natural history of disseminated intravascular coagulation diagnosed based on the newly established diagnostic criteria for critically ill patients: results of a multicenter, prospective survey. Crit. Care. Med. 2008, 36, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wada, H.; Takahashi, H.; Uchiyama, T.; Eguchi, Y.; Okamoto, K.; Kawasugi, K.; Madoiwa, S.; Asakura, H.; DIC subcommittee of the Japanese Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis. The approval of revised diagnostic criteria for DIC from the Japanese Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis. Thromb. J. 2017, 15, 17. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Asakura, H. Classifying types of disseminated intravascular coagulation: clinical and animal models. J. Intensive. Care. 2014, 2, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Asakura, H.; Takahashi, H.; Uchiyama, T.; Eguchi, Y.; Okamoto, K.; Kawasugi, K.; Madoiwa, S.; Wada, H.; DIC subcommittee of the Japanese Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis. Proposal for new diagnostic criteria for DIC from the Japanese Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis. Thromb. J. 2016, 14, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattray, D.D.; O’Connell, C.M.; Basket, T.F. Acute disseminated intravascular coagulation in obstetrics: a tertiary centre population review (1980 to 2009). J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2012, 34, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gando, S.; Levi,M. ; Toh, C.H. Disseminated intravascular coagulation. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2016, 2, 16037. [Google Scholar]

- Erez, O.; Othman, M.; Rabinovich, A.; Leron, E.; Gotsch, F.; Thachil, J. DIC in pregnancy–pathophysiology, clinical characterristics, diagnostic scores, and treatment. J. Blood. Med. 2022, 13, 21–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi, M. Pathogenesis and management of peripartum coagulopathic calamities (disseminated intravascular coagulation and amniotic fluid embolism). Thromb. Res. 2013, 131, 32–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collis, R.E.; Collins, P.W. Haemostatic management of obstetric haemorrhage. Anesthesia. 2015, 70, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, P.; Abdul-Kadir, R.; Thachil, J. Management of coagulopathy associated with postpartum hemorrhage: guidance from the SSC of the ISTH. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2016, 14, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terao, T.; Maki, M.; Ikenoue, T. A prospective study in 38 patients with abruptio placentae of 70 cases complicated by DIC. Asia-Oceania. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1987, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, F.G.; Nelson, D.B. Disseminated intravascular coagulation syndromes in obstetrics. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 126, 999–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM). ; Pacheco, L.D.; Saade, G.; Hankins, G.D.V.; Clark, S.L. Amniotic fluid embolism: diagnosis and management. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 215, B16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyagi, Y.; Tada, K.; Yasuhi, I.; Tsumura, K.; Maegawa, Y.; Tanaka, N.; Mizunoe, T.; Emoto, I.; Maeda, K.; Kawakami, K.; and behalf of the Collaborative Research in National Hospital Organization Network Pediatric and Perinatal Group. A novel method for determining fibrin/fibrinogen degradation products and fibrinogen threshold criteria via artificial intelligence in massive hemorrhage during delivery with hematuria. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erez, O.; Novack, L.; Beer-Weisel, R.; Dukler, D.; Press, F.; Zlotnik, A.; Than, NG.; Tomer, A.; Mazor, M. DIC score in pregnant women – A population based modification of the International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis score. PLoS. One. 2014, 11, 9, e93240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morikawa, M.; Kamiya, A.; Yoshida, A.; Nishibata, S.; Okada, H. Differences between Japanese new criteria and pregnancy-specific modified ISTH DIC scores for obstetrical DIC diagnosis. Int. J. Hematol. 2024, 119, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananth, C.V.; Lavery, J.A.; Vintzileos, A.M.; Skupski, D.W.; Varmer, M.; Saade, G.; Biggio, J.; Williams, M.A.; Wapner, R.J.; Wright, J.D. Severe placental abruption: clinical definition and association with maternal complications. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 214, 272, e1–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyagi, Y.; Tada, K.; Yasuhi, I.; Maekawa, Y.; Okura, N.; Kawakami, K.; Yamaguchi, K.; Ogawa, M.; Kodama, K.; Nomiyama, N.; Mizunoe, T.; Miyake, T. New method for determining fibrinogen and FDP threshold criteria by artificial intelligence in cases of massive hemorrhage during delivery. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2020, 46, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikkelsø, A.J.; Edwards, H.M.; Afshari, A.; Stensballe, J.; Langhoff-Roos, J.; Albrechtsen, C.; Ekelund, K.; Hanke, G.; Secher, E.L.; Sharif, H.F.; FIB-PPH Trial Group. Pre-emptive treatment with fibrinogen concentrate for postpartum haemorrhage: randomized controlled trial. Br. J. Anaesth. 2015, 114, 623–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavrides, E.; Allard, S.; Chandraharan, E.; Collins, P.; Green, L.; Hunt, B.J.; Riris, S.; Thomson, A.J.; on behalf of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Prevention and management of postpartum haemorrhage. BJOG. 2016, 124, e106–e149. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z; Liu, C. ; Zhong, M.; Yang, F.; Chen, H.; Kong, W.; Lv, P.; Chen, W.; Yao, Y.; Cao, Q.; Zhou, H. Changes in coagulation and fibrinolysis in post-cesarean section parturients treated with low molecular weight heparin. Clin. Appl. Thromb. Hemost. 2020, 26, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G. : Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. STROBE Initiative. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ. 2007, 335, 806–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allard, S.; Green, L.; Hunt, B.J. How we manage the haematologic aspects of major obstetric haemorrhage. Br. J. Haematol. 2014, 164, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erez, O.; Mastrolia, S.A.; Thachil, J. Disseminated intravascular coagulation in pregnancy: insights in pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 213, 452–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bączkowska, M.; Zgliczyńska, M.; Faryna, J.; Przytuła, E.; Nowakowski, B.; Ciebiera, M. Molecular changes on maternal-fetal interface in placental abruption–A systematic review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ide, R.; Oda, T.; Todo, Y.; Kawai, K.; Matsumoto, M.; NarumiM. ; Kohmura-Kobayashi, Y.; Furuta-Isomura, N.; Yaguchi, C.; Uchida, T.; Suzuki, K.; Kanayama, N.; Itoh, H.; Tamura, N. Comparative analysis of hyperfibrinolysis with activated coagulation between amniotic fluid embolism and severe placental abruption. Sci. Rep. 2024, 2, 14 (1), 272. [Google Scholar]

- Sawamura, A.; Hayakawa, M.; Gando, S.; Kubota, N.; Sugano, M.; Wada, T.; Katabami, K. Disseminated intravascular coagulation with a fibrinolytic phenotype at an early phase of trauma predicts mortality. Thromb. Res. 2009, 124, 608–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, T. PAMPs and DAMPs as trigger for DIC. J. Intensive. Care. 2014, 2, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iba, T.; Levy, J.H. Sepsis-induced coagulopathy and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Anesthesiology. 2020, 132, 1238–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Raoof, M.; Chen, Y.; Sursal, T.; Junger, W.; Bohi, K.; Itagaki, K.; Hauser, C.J. Circulating mitochondrial DAMPs cause inflammatory responses to injury. Nature. 2010, 464, 104–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, R.L.; Lang, M.Z.; Qiao, X.M. Immune storm and coagulation storm in the pathogenesis of amniotic fluid embolism. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2021, 25, 1796–1803. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Romero, R.; Chaiworapongsa, T.; Alpay, S.Z.; Xu, Y.; Hussein, Y.; Dong, Z.; Kusanovic, J.P.; Kim, C.J.; Hassan, S.S. Damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) in preterm labor with intact membranes and preterm PROM: a study of the alarmin HMGB1. J. Matern. Fetal. Neonatal. Med. 2011, 24, 1444–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leong, A.S.; Norman, J.E.; Smith, R. Vascular and myometrial changes in the human uterus at term. Reprod. Sci. 2008, 15, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayami, H.; Ohama, S.; Sakurai, A.; Yamada, J.; Yamaguchi, O.; Koide, Y.; Okura, M. Effect of amniotic fluid on blood coagulation. Crit. Care. 2009, 13, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oda, T.; Tamura, M.; Shen, Y.; Kohmura-Kobayashi, Y.; Furuta-Isomura, N.; Yaguchi, C.; Uchida, T.; Suzuki, K.; Ito, H.; Kanayama, N. Amniotic fluid as potent activator of blood coagulation and platelet aggregation: Study with rotational thromboelastometry. Thromb. Res. 2018, 172, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikkanen, M. Etiology, clinical manifestations, and prediction of placental abruption. Acta. Obstetrika. et. Gynecogica. 2010, 89, 732–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PPH group (n = 18) (PPH without MH) |

PA group (n = 13) (PA without MH) |

MH group (n = 3) (PPH with MH) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal characteristics | ||||

| Age (years) | 37 (28–45) | 32 (22–45) | 32 (28–36) | 0.20 |

| Nulliparity (%) | 10 (56) | 3 (23) | 2 (67) | 0.14 |

| Body mass index at delivery (kg/m2) | 26.1 (20.7–28.1) | 27.6 (22.6–38.6) | 25.6 (20.6–28.6) | 0.12 |

| Gestational age at delivery (weeks) | 37.5 (28–41) | 35 (22–39) | 37 (32–38) | < 0.05 |

| HDP complicated | ||||

| Gestational hypertension (%) | 1 (6) | 1 (8) | 1 (33) | 0.29 |

| Preeclampsia (%) | 6 (33) | 6 (46) | 1 (33) | 0.76 |

| Neonatal characteristics | ||||

| Apgar score at 1 min | 8 (1–10) | 1 (0–8) | 8 (1–8) | < 0.001 |

| Umbilical arterial pH | 7.292 (7.051–7.351) | 7.045 (6.563–7.282) | 7.228 (7.225–7.296) | < 0.001 |

| Mode of delivery | ||||

| Cesarean section (%) | 9 (50) | 12 (92) | 3 (100) | < 0.05 |

| Instrumental vaginal (%) | 2 (11) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.39 |

| Multifetal pregnancy (%) | 4 (22) | 0 (0) | 1 (33) | 0.14 |

| Maternal transport (%) | 6 (33) | 5 (38) | 0 (0) | 0.44 |

| Causes of bleeding | ||||

| Uterine atony (%) | 8 (44) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Placenta previa (%) | 2 (33) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| Adherent placenta (%) | 4 (33) | 0 (0) | 1 (33) | – |

| Surgical trauma (%) | 3 (17) | 0 (0) | 2 (67) | – |

| Others (%) | 1 (6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| PA (%) | 0 (0) | 13 (100) | 0 (0) | – |

|

PPH group (n = 18) (PPH without MH) |

PA group (n = 13) (PA without MH) |

MH group (n = 3) (PPH with MH) |

p-value | |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 6.75 (5–10.2) | 8.3 (4.9–11.3) | 7.5 (4.5–10.1) | < 0.05 |

| Platelet counts (×1000/μL) | 88 (39–147) | 120 (45–204) | 96 (76–144) | 0.31 |

| Prothrombin time–INR | 1.11 (0.96–10) | 1.1 (1.02–1.44) | 1.53 (1.46–1.84) | < 0.05 |

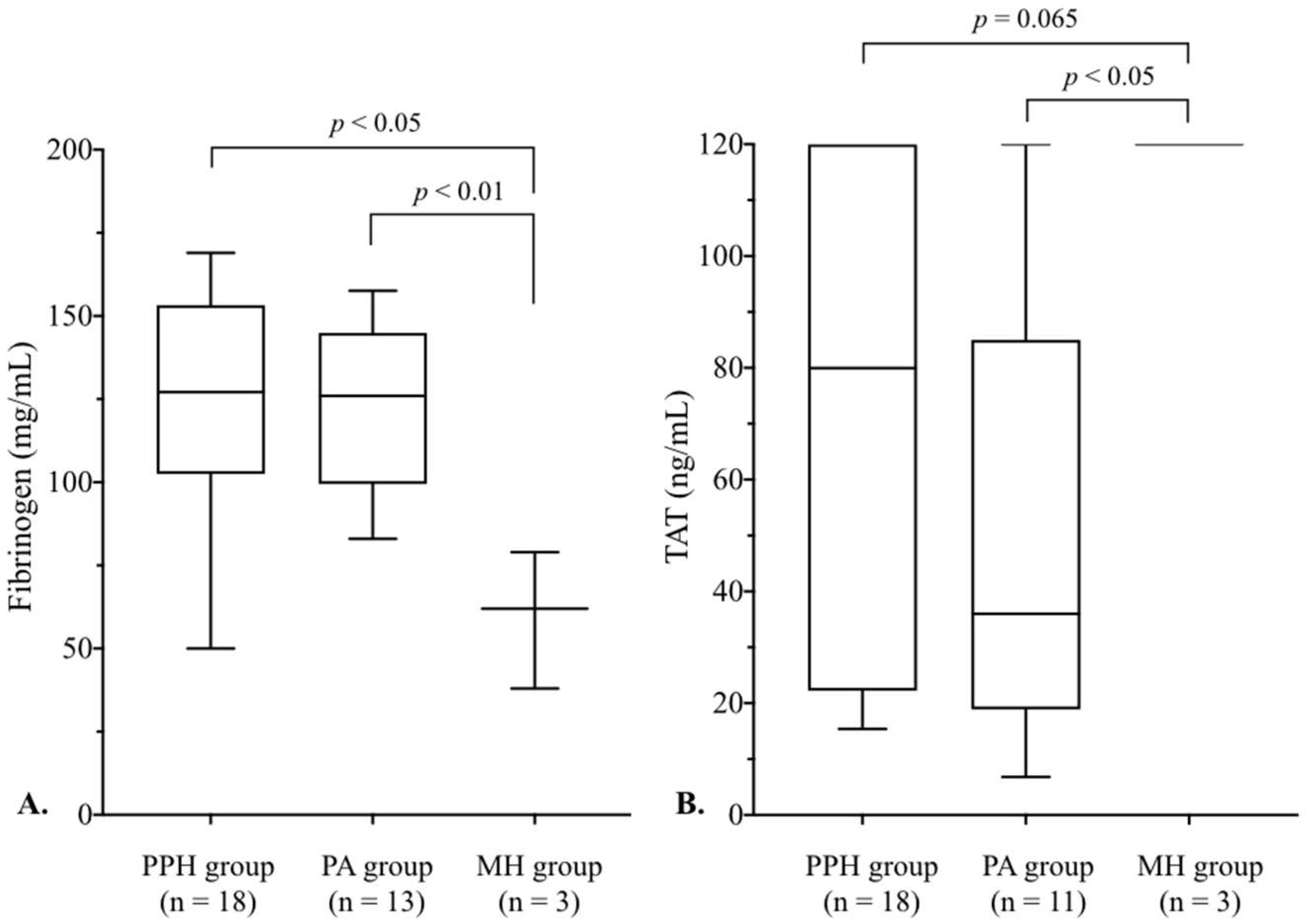

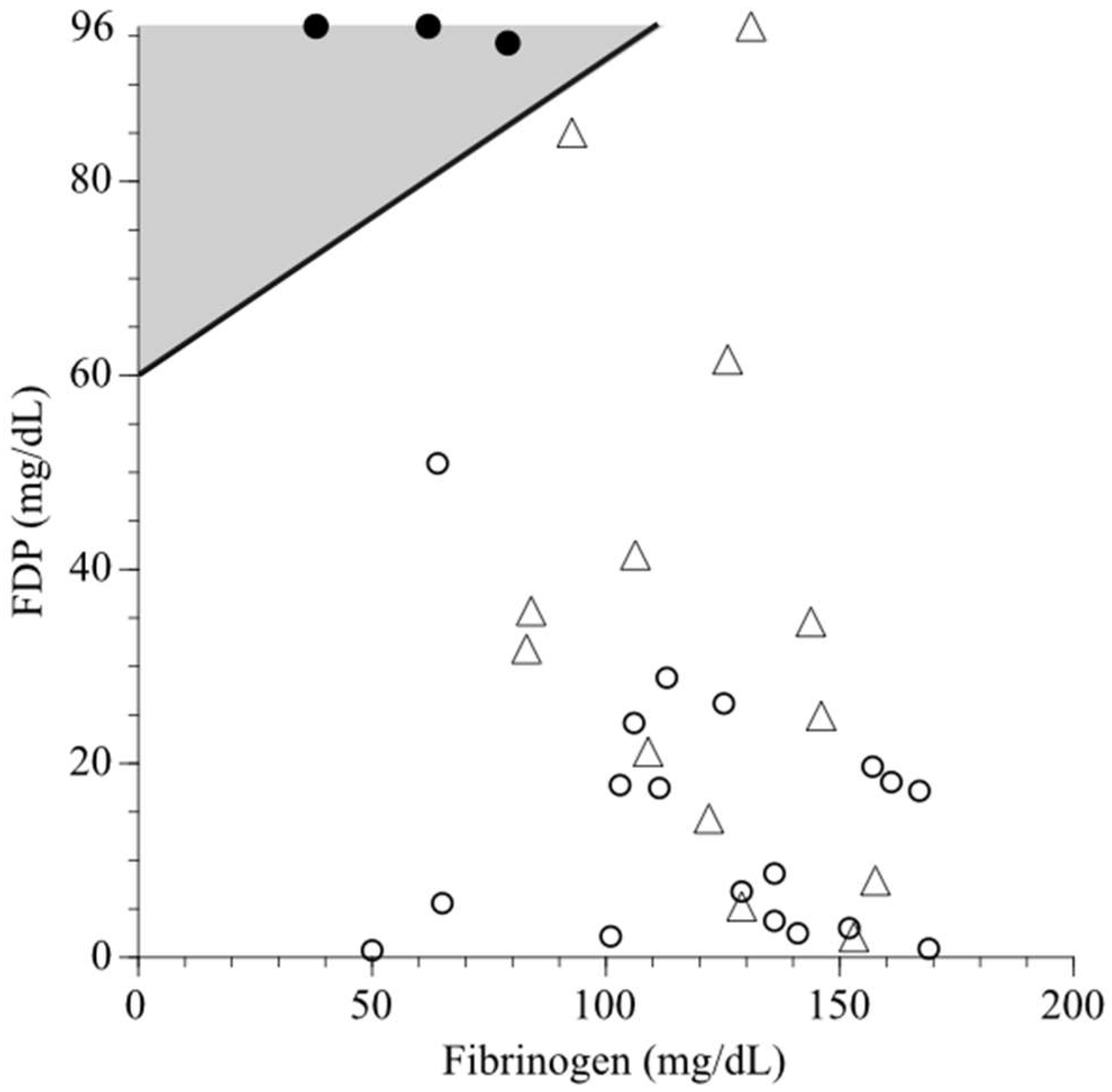

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 127.1 (50–169) | 126 (83–158) | 62 (38–79) | < 0.05 |

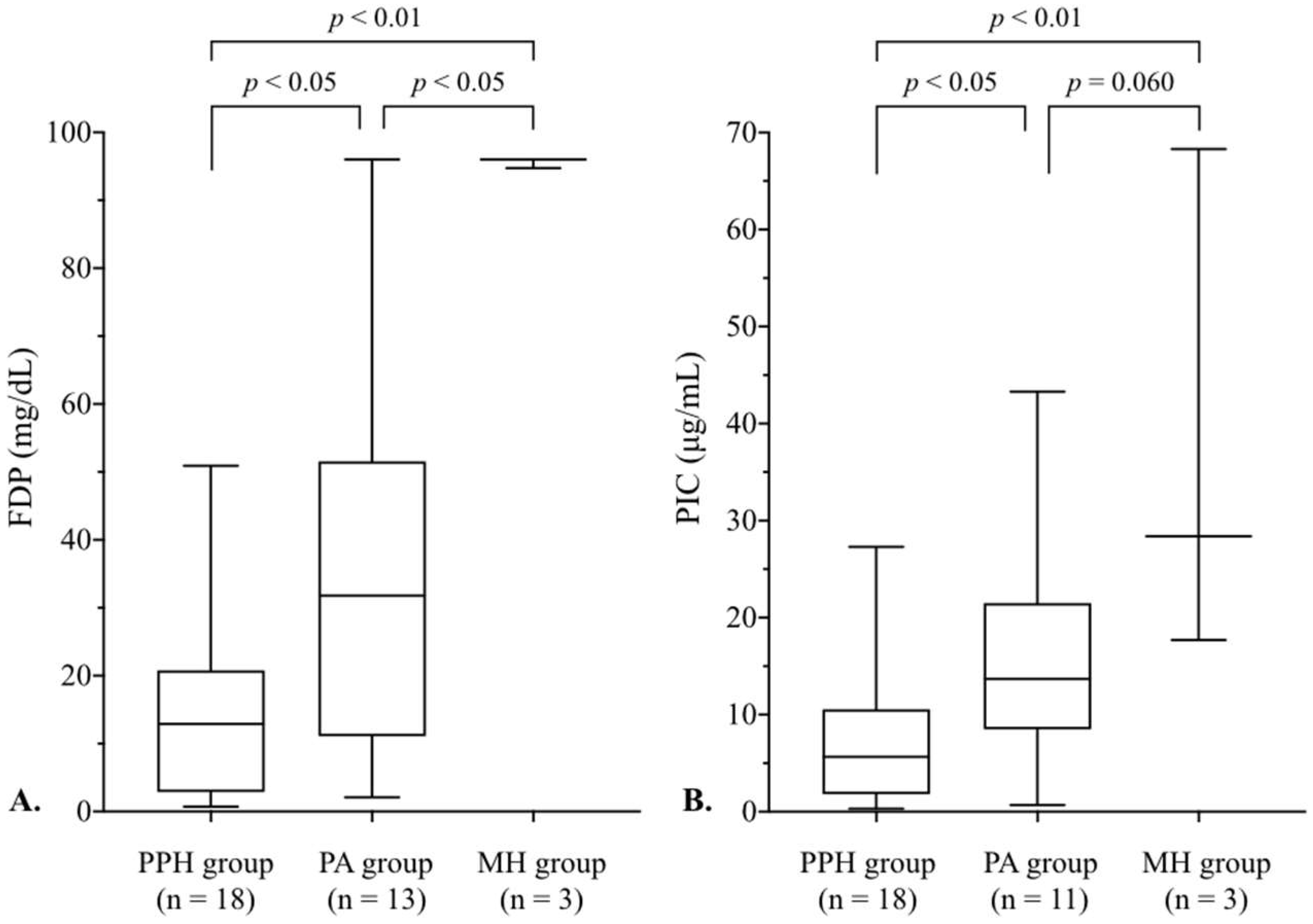

| FDP (mg/dL) | 12.9 (0.72–50.93) | 31.8 (2.09–96) | 96 (94.73–96) | < 0.01 |

| D-dimer (mg/dL) | 2.875 (0.3–21.9) | 3.7 (0.65–26.69) | 42.55 (13.54–49.1) | < 0.05 |

| TAT (ng/mL) | 79.95 (15.4–120) | 36 (6.8–120), n=11 | 120 (120–120) | 0.054 |

| PIC (μg/mL) | 5.65 (0.3–27.3) | 13.7 (0.7–43.3), n=11 | 28.4 (17.7–68.3) | < 0.01 |

| Time between delivery and initial blood sampling (h) | 2.83 (1–14) | 2 (0.56–8) | 1.5 (1.3–4) | 0.30 |

| Blood loss at initial blood sampling (mL) | 2,598.5 (900–4,000) | 1,594 (404–4,294) | 2,215 (1,300–2,215) | < 0.05 |

| Total blood loss (mL) | 3,148 (2,015–5,294) | 1,856 (475–4,294) | 2,950 (2,700–3,801) | < 0.001 |

| Volume of clear fluids at initial blood sampling (mL) | 2,250 (100–4,000) | 1,500 (100–4,500) | 1,500 (500–2,000) | 0.25 |

| Total volume of clear fluids | 4,000 (2,500–8,000) | 3,000 (1,500–5,000) | 4,500 (3,500–5,500) | 0.13 |

| Volume of RCC at initial blood sampling (mL) | 0 (0–1,120) | 0 (0–2,240) | 0 (0–0) | 0.44 |

| Total volume of RCC (mL) | 840 (0–3,360) | 560 (0–2,520) | 1,120 (840–1,960) | 0.18 |

| Volume of FFP at initial blood sampling (mL) | 240 (0–1,200) | 480 (0–3,600) | 0 (0–0) | 0.42 |

| Total volume of FFP (mL) | 720 (0–4,800) | 960 (0–4,080) | 960 (720–1,920) | 0.72 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).