Submitted:

25 April 2025

Posted:

25 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodologies for obtaining the UVF 3D digital models

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

- The literature research revealed the presence of several papers underlying the great utility of ultraviolet fluorescence photography as diagnostic tools to support the restoration, starting from the first published articles about a century ago.

- If from one hand the use of UVF imaging in 2D is widespread, the same one in 3D is much less applied, due to the difficulty of the procedure, especially in the phase of acquisition of the images necessary for creating the 3D model.

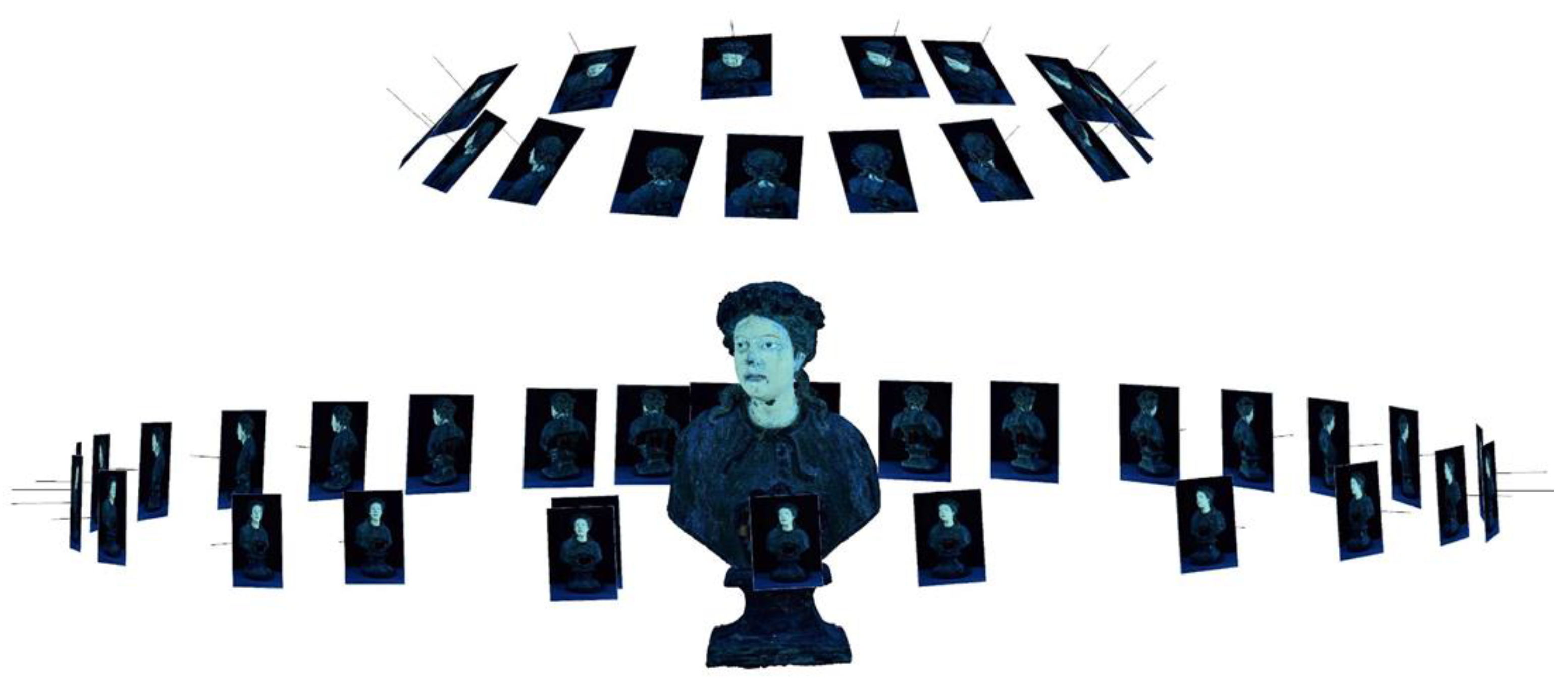

- Starting from 2017, some authors proposed an innovative approach aimed at simplifying the acquisition. The approach is based on photogrammetry and SfM but something has been modified. In fact, the camera and the UV sources are fixed and the object to be acquired is rotated on a turntable. The acquisition is possible thanks to the completely dark background required for UVF capture, as described in detail in paragraph 2.

- One relevant aspect is the visualization and use of the 3D UVF models. In fact, the output is generally reported by showing 2D images that are extrapolated from the 3D model workflow or even single frames used for creating the digital model. The use of online platforms, such as Sketchfab, may give valid help in this regard. Sketchfab allows publishing 3D models that can be interactively investigated from simple devices, i.e., mobile, tablet, laptop, etc.

- Lastly the original models can be further used for other applications, such as mapping of the state of conservation in case of restoration activities, this being a usual procedure in the phases of documentation of artworks that precede the practical operations on them.

| Link to the 3D UVF model | Publication |

|---|---|

| https://skfb.ly/6EMy7 | Lanteri et al. [33] |

| https://sketchfab.com/3d-models/san-icodono-ridotto-623eeb3a3e6c40888f0c9663c5fc4adf | Lanteri and Pelosi [42] |

| https://sketchfab.com/3d-models/san-rodonio-tempo-1-187ef9beb2de45388bde63390591a778 | Lanteri and Pelosi [42] |

| https://sketchfab.com/3d-models/san-filomelo-3ef74f8fe0af4d2291b6898d6f72d391 | Lanteri and Pelosi [42] |

| https://sketchfab.com/3d-models/san-leonardo-7bcff9ed23ae4221a50ba52b06285679 | Lanteri and Pelosi [42] |

| https://sketchfab.com/3d-models/santa-rosalia-8b4cf6c05837433c8c383b6266bf46fb | Lanteri and Pelosi [42] |

| https://sketchfab.com/3d-models/santo-stefano-ac0f26ccea1d466a822a499df5df1d3b | Lanteri and Pelosi [42] |

| https://sketchfab.com/3d-models/pio-v-3d-uvf-model-063c014bb7734581b3ebfca95d1ab85e | Lanteri and Pelosi [12] |

| https://sketchfab.com/3d-models/copricapo-uvf-45e43bcc474b470e8c8b876db917ba3e | Colantonio et al. [39] |

| https://sketchfab.com/3d-models/tomba-degli-scudi-tarquinia-7a183dcbe1e84bb199babcc0b30c3905 | Rinaldi et al. [85] |

| https://sketchfab.com/3d-models/modello-3d-bambinello-corona-8d6a084e53144fb98174b8a0671ca4d5 | Ceci et al. [41] |

| https://sketchfab.com/3d-models/madonna-del-carmine-3d-model-672bf63e67f44f40b102dd789658bb0a | Published on Sketchfab |

| https://sketchfab.com/3d-models/sant-andrea-3d-uvf-5f10ae5fb00242e293aaa297473dad68 | Published on Sketchfab |

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mairinger, F. The ultraviolet and fluorescence study of paintings and manuscripts. (2000). In Radiation in Art and Archeometry, Creagh, D.C., Bradley, D.A. (Eds.); Elsevier Science B.V., Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2000, 56-75. [CrossRef]

- Buzzegoli, E.; Keller, A. Ultraviolet fluorescence imaging. In Scientific Examination for the Investigation of Paintings. A Handbook for Conservator-Restorers; Pinna, D., Galeotti, M., Mazzeo, R., Eds.; Centro Di Edifimi srl: Firenze, Italy, 2009; 204–206. [Google Scholar]

- Cosentino, A. Practical notes on ultraviolet technical photography for art examination. Conservar Património 2015, 21, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mairinger, F. UV-, IR-, and X-ray imaging. In Non-Destructive Micro Analysis of Cultural Heritage Materials, 1st ed.; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2004; pp. 15–71. [Google Scholar]

- Pelagotti, A.; Pezzati, L.; Bevilacqua, N.; Vascotto, V.; Reillon, V.; Daffara, C. A Study of UV Fluorescence Emission of Painting Materials. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Non-Destructive Investigations and Microanalysis for the Diagnostics and Conservation of the Cultural and Environmental Heritage, Lecce, Italy, 15–19 May 2005; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, J.; Yadav, S. Analytical Tools for Multifunctional Materials. In Multifunctional Materials D.B. Tripathy, D.B.; Gupta A., Jain, A.K. (Eds.); Wiley; Hoboken, New Jersey, USA, 2025, 335-364. [CrossRef]

- Angheluță, L.M.; Popovici, A.I.; Ratoiu, L.C. A Web-Based Platform for 3D Visualization of Multimodal Imaging Data in Cultural Heritage Asset Documentation. Heritage 2023, 6, 7381–7399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogliani, P.; Pelosi, C.; Lanteri, L.; Bordi, G. Imaging Based Techniques Combined with Color Measurements for the Enhancement of Medieval Wall Paintings in the Framework of EHEM Project. J. Imaging 2024, 10, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De la Rie, E.R. Fluorescence of Paint and Varnish Layers (Part I). Stud. Conserv. 1982, 27, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Rie, E.R. Fluorescence of Paint and Varnish Layers (Part II). Stud. Conserv. 1982, 27, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Rie, E.R. Fluorescence of Paint and Varnish Layers (Part III). Stud. Conserv. 1982, 27, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanteri, L.; Pelosi, C. 2D and 3D ultraviolet fluorescence applications on cultural heritage paintings and objects through a low-cost approach for diagnostics and documentation. In Proceedings of the SPIE 11784, Optics for Arts, Architecture, and Archaeology VIII, Online, 21–26 June 2021; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2015; p. 1178417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearlstein, E. , Paulson, M. A Review of Ultraviolet Induced Luminescence of Undyed Feathers in Cultural Heritage. In: Springer Series on Fluorescence. Springer, Cham., 2023. [CrossRef]

- Pottier, F.; Michelin, A.; Robinet, L. Recovering illegible writings in fire-damaged medieval manuscripts through data treatment of UV-fluorescence photography. J. Cult. Herit. 2019, 36, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montani, I.; Sapin, E.; Pahud, A.; Margot, P. Enhancement of writings on a damaged medieval manuscript using ultraviolet imaging. J. Cult. Herit. 2012, 13, 226–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dondi, P.; Lombardi, L.; Invernizzi, C.; Rovetta, T.; Malagodi, M.; Licchelli, M. Automatic Analysis of UV-Induced Fluorescence Imagery of Historical Violins. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2017, 10, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearlstein, E.; Hughs, M.; Mazurek, J.; McGraw, K.; Pesme, C.; Riedler, R.; Gleeson, M. Ultraviolet-Induced Visible Fluorescence and Chemical Analysis as Tool for Examining Featherwork. J. Am. Inst. Conserv. 2015, 54, 149–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, N.; Orsilli, J.; Bonizzoni, L.; Gargano, M. UV-IR image enhancement for mapping restorations applied on an Egyptian coffin of the XXI Dynasty. Archaeol. Anthrop. Sci. 2019, 11, 6841–6850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piroddi, L.; Abu Zeid, N.; Calcina, S.V.; Capizzi, P.; Capozzoli, L.; Catapano, I.; Cozzolino, M.; D’Amico, S.; Lasaponara, R.; Tapete, D. Imaging Cultural Heritage at Different Scales: Part I, the Micro-Scale (Manufacts). Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldia, C.M.; Jakes, K.A. . Photographic methods to detect colourants in archaeological textiles. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2007, 34, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groppi, F.; Vigliotti, D.; Lanteri, L.; Agresti, G.; Casoli, A.; Laureti, S.; Ricci, M.; Pelosi, C. Advanced documentation methodologies combined with multi-analytical approach for the preservation and restoration of 18th century architectural decorative elements at Palazzo Nuzzi in Orte (Central Italy). Int. J. Conserv. Sci. 2021, 12, 921–934. [Google Scholar]

- Laureti, S.; Colantonio, C.; Burrascano, P.; Melis, M.; Calabrò, G.; Malekmohammadi, H.; Sfarra, S.; Ricci, M.; Pelosi, C. Development of integrated innovative techniques for the examination of paintings: The case studies of The Resurrection of Christ attributed to Andrea Mantegna and the Crucifixion of Viterbo attributed to Michelangelo’s workshop. J. Cult. Herit. 2019, 40, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picollo, M.; Stols-Witlox, M.; Fuster López, L. (Eds.) UV-Vis Luminescence Imaging Techniques / Técnicas de imagen de luminiscencia UV-Vis. Conservation 360°, No. 1, 342, 2019. [CrossRef]

- McGlinchey Sexton, J.; Messier, P.; Chen, J.J. Development and testing of a fluorescence standard for documenting ultraviolet induced visible fluorescence. In Proceedings of the 42nd Annual Meeting of the American Institute for Conservation, San Francisco, CA, USA, 28–31 May 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Koochakzaei, A.; Nemati Babaylou, A.; Jelodarian Bidgoli, B. Identification of Coatings on Persian Lacquer Papier Mache Penboxes by Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy and Luminescence Imaging. Heritage 2021, 4, 1962–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Measday, D. A Summary of Ultra-Violet Fluorescent Materials Relevant to Conservation. 2017. Available online: https://aiccm.org.au/national-news/summary-ultra-violet-fluorescent-materials-relevant-conservation (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Rorimer, J.J. Ultraviolet X Rays and Their Use in the Examination of Works of Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art: New York, USA, 1931.

- Eibner, A. Lichtwerkungen auf Malerfarben VII, Die Lumineszenzforschung im Dienst der Bilderkunde und Anstrichtechnik. Chemiker Zeitung, 1931, 593-604, 614-615, 635-637, 655-656.

- Eibner, A. Les rayons ultraviolets appliques à l’examen des couleurs et des agglutinants. Mouseion 1933, 21-22, 32–68. [Google Scholar]

- Eibner, A. Zum gegenwartigen Stand der naturwissenschaftlichen Bilduntersuchung, Angewandte Chemie 1932, 45, 301–307.

- Lyon, R.A. Ultraviolet rays as aids to restorers. Technical Studies in the Field of the Fine Arts 1934, 2, 152–157. [Google Scholar]

- Lanteri, L.; Agresti, G. Ultraviolet fluorescence 3D models for diagnostics of cultural heritage. Eur. J. Sci. Theol. 2017, 13, 35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Lanteri, L.; Agresti, G.; Pelosi, C. 3D model and ultraviolet fluorescence rendering: a methodological approach for the study of a wooden reliquary bust. In Proceedings of the 10th European Symposium on Religious Art, Restoration & Conservation, Prague, Magál, S., Mendelova, D., Petranová, D. Apostolescu, N. (Eds.); Lexis Compagnia Editoriale in Torino srl, Torino, Italy, 2018, 31 May - 1 June 2018; pp. 110–113. [Google Scholar]

- Lanteri, L.; Agresti, G.; Pelosi, C. A New Practical Approach for 3D Documentation in Ultraviolet Fluorescence and Infrared Reflectography of Polychromatic Sculptures as Fundamental Step in Restoration. Heritage 2019, 2, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedeaard, S.B.; Brøns, C.; Drug, I.; Saulins, P.; Bercu, C.; Jakovlev, A.; Kjær, L. Multispectral Photogrammetry: 3D models highlighting traces of paint on ancient sculptures. In Proceedings of the DHN, Copenhagen, Denmark, 5–8 March 2019; Published in 2024; pp. 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keats Webb, E.; Robson, S.; Evans, E.; O’Connor, A. Wavelength Selection Using a Modified Camera to Improve Image-Based 3D Reconstruction of Heritage Objects. J. Am. Inst. Conserv. 2023, 62, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathys, A.; Jadinon, R.; Hallot, P. Exploiting 3D multispectral texture for a better feature identification for cultural heritage. ISPRS Annals of Photogrammetry. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2019, 4, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radpour, R.; Fischer, C.; Kakoulli, I. A 3D modeling workflow to map ultraviolet- and visible-induced luminescent materials on ancient polychrome artifacts. Digit. Appl. Archaeol. Cult. Herit. 2021, 23, e00205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colantonio, C.; Lanteri, L.; Ciccola, A.; Serafini, I.; Postorino, P.; Censorii, E.; Rotari, D.; Pelosi, C. Imaging Diagnostics Coupled with Non-Invasive and Micro-Invasive Analyses for the Restoration of Ethnographic Artifacts from French Polynesia. Heritage 2022, 5, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Es Sebar, L.; Lombardo, L.; Buscaglia, P.; Cavaleri, T.; Lo Giudice, A.; Re, A.; Borla, M.; Aicardi, S.; Grassini, S. 3D Multispectral Imaging for Cultural Heritage Preservation: The Case Study of a Wooden Sculpture of the Museo Egizio di Torino. Heritage 2023, 6, 2783–2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceci, A.; Lanteri, L.; Pelosi, C.; Pogliani, P.; Sottile, S. Analysis of materials of wax Christ-children from the Monastery of Santa Rosa in Viterbo. In 2023 IMEKO TC-4, International Conference on Metrology for Archaeology and Cultural Heritage, University of Rome 3, Italy, October 19-21, 2023, pp. 468–473. [CrossRef]

- Lanteri, L.; Pelosi, C. Operational methods implemented for the monitoring of the artworks preserved in the Museum and the Conclave Hall of the “Colle del Duomo Museum Complex” of the Viterbo Diocese, Lazio – Italy. In Methodologies and Strategies for Cultural Heritage Protection and Conservation Against Climate Changes, Natural and Anthropic Risks; Di Ciaccio, F., Fiorini L., Tucci, G. (Eds.); Springer Nature Switzerland AG, Cham, Switzerland, 2025, pp. 144–153.

- Grifoni, E.; Legnaioli, S.; Lorenzetti, G.; Pagnotta, S.; Palleschi, V. Image based recording of three-dimensional profiles of paint layers at different wavelengths. Eur. J. Sci. Theol. 2017, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Grifoni, E.; Legnaioli, S.; Nieri, P.; Campanella, B.; Lorenzetti, G.; Pagnotta, S.; Poggialini, F.; Palleschi, V. Construction and comparison of 3D multi-source multi-band models for cultural heritage applications. J. Cult. Herit. 2018, 34, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keats Webb, E. UV induced luminescence. In UV-Vis Luminescence Imaging Techniques / Técnicas de imagen de luminiscencia UV-Vis; Picollo, M.; Stols-Witlox, M.; Fuster López, L. (Eds.); Conservation 360°, 2020, No. 1, 35-60. https://monografias.editorial.upv.es/index.php/con_360/article/view/67.

- Bonizzoni, L.; Caglio, S.; Galli, A.; Lanteri, L.; Pelosi, C. Materials and Technique: The First Look at Saturnino Gatti. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Invernizzi, C.; Fichera, G.V.; Licchelli, M.; Malagodi, M. A non-invasive stratigraphic study by reflection FT-IR spectroscopy and UV-induced fluorescence technique: The case of historical violins. Microchem. J. 2018, 138, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grifoni, E.; Bonizzoni, L.; Gargano, M.; Melada, J.; Ludwig, N.; Bruni, S.; Mignani, I. Hyper-dimensional Visualization of Cultural Heritage: A Novel Multi-Analytical Approach on 3D Pomological Models in the Collection of the University of Milan. ACM Journal on Computing and Cultural Heritage (JOCCH) 2022, 15, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tragni, C.B.; Chen, J.; Kushel, D.; The Use of Ultraviolet-Induced Visible Fluorescence for Examination of Photographs. Capstone Research Project, Advanced Residency Program in Photograph Conservation, George Eastman House/Image Permanence Institute. Rochester, NY. Available online: https://www.eastman.org/advanced-residency-program-photograph-conservation-capstone-research-projects (accessed on 10 Aprile 2025).

- Dyer, J.; Verri, G.; Cupitt, J. Multispectral Imaging in Reflectance and Photo-induced Luminescence modes: A User Manual. Available on line: https://www.britishmuseum.org/pdf/charisma-multispectral-imaging-manual-2013.pdf (accessed 10 April 2025 ).

- Dyer, J.; Sotiropoulou, S. A technical step forward in the integration of visible induced luminescence imaging methods for the study of ancient polychromy. Herit. Sci. 2017, 5, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verri, G. The application of visible-induced luminescence imaging to the examination of museum objects. In Proceedings of the SPIE 7391, Optics for Arts, Architecture, and Archaeology II, Munich, Germany, 25 June 2009; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2015; p. 739105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verri, G.; Saunders, D. Xenon flash for reflectance and luminescence (multispectral) imaging in cultural heritage applications. British Museum Technical Research Bulletin 2014, 8, 83–92. [Google Scholar]

- Daveri, A.; Vagnini, M.; Nucera, F.; Azzarelli, M.; Romani, A.; Clementi, C. Visible-induced luminescence imaging: A user-friendly method based on a system of interchangeable and tunable LED light sources. Microchem. J. 2016, 125, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowther, J. Ultraviolet Fluorescence Photography—Choosing the Correct Filters for Imaging. J. Imaging 2022, 8, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo Pereira, L. UV Fluorescence Photography of Works of Art: Replacing the Traditional UV Cut Filters with Interference Filters. Int. J. Conserv. Sci. 2010, 1, 161–166. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, A. Digital Ultraviolet and Infrared Photography; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018; p. 76. [Google Scholar]

- Reichel, S.; Biertümpfel, R.; Engel, A. Characterization and measurement results of fluorescence in absorption optical filter glass. In Proceedings of the SPIE Volume 9626, Optical Systems Design 2015: Optical Design and Engineering VI, Jena, Germany, September 2015; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2015; p. 96260S. [Google Scholar]

- Christens-Barry, W.A.; Boydston, K.; France, F.G.; Knox, K.T.; Easton, J.R.L.; Toth, M.B. Camera system for multispectral imaging of documents. In Proceedings of the SPIE-IS&T 7249, Electronic Imaging: Sensors Cameras and Systems Industrial/Scientific Applications, San Jose, California, United States, 27 January 2009; p. 724908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triolo, P.A.; Spingardi, M.; Costa, G.A.; Locardi, F. Practical application of visible-induced luminescence and use of parasitic IR reflectance as relative spatial reference in Egyptian artifacts. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2019, 11, 5001–5008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delcourt, J. Un système intégré d’acquisition 3D multispectral : acquisition, codage et compression des données. Thesis, Université de Bourgogne, France, 2018. Available at: https://theses.hal.science/tel-00578448v3. (Accessed 3 April, 2025).

- Keats Webb, E. , Robson, S.; MacDonald, L.; Garside, D.; Evans, R. Spectral and 3D cultural heritage documentation using a modified camera. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci. 2018; XLII-2, 1183–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crippa, G.; Masini, S. Photography in the ultraviolet and visible violet spectra: Unravelling methods and applications in palaeontology. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 2022, 67, 685–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.J.; Smith, T.J. Documentation of Salted Paper Prints with a Modified Digital Camera. J. Am. Inst. Conserv. 2019, 59(3–4), 271–285. [CrossRef]

- Facini, M.; Heller, D.; Jenkins, A.; King, T.; Orlandini, V.; Salazar, M.; Hugh Shockey, L.; Swerda, K.; Vignaio, A.; Photographing Ultra-Violet Fluorescence with Digital Cameras. Waac Newsletters 2001, 23. Available online: https://cool.culturalheritage.org/waac/wn/wn23/wn23-2/wn23-205.html (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Cosentino, A. Effects of different binders on technical photography and infrared reflectography of 54 historical pigments. Int. J. Conserv. Sci. 2015, 6, 287–298. [Google Scholar]

- Cosentino, A. Identification of pigments by multispectral imaging; a flowchart method. Herit Sci 2014, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, G. Distinctive Image Features from Scale-Invariant Keypoints. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2004, 60, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiabrando, F.; Donadio, E.; Rinaudo, F. SfM for Orthophoto to Generation: A Winning Approach for Cultural Heritage Knowledge. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci. 2015; XL-5/W7, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandolini, F.; Patrucco, G. Structure-from-Motion (SFM) Photogrammetry as a Non-Invasive Methodology to Digitalize Historical Documents: A Highly Flexible and Low-Cost Approach? Heritage 2019, 2, 2124–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepe, M.; Alfio, V.S.; Costantino, D. UAV Platforms and the SfM-MVS Approach in the 3D Surveys and Modelling: A Review in the Cultural Heritage Field. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 12886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barszcz, M.; Montusiewicz, J.; Paśnikowska-Łukaszuk, M.; Sałamacha, A. Comparative Analysis of Digital Models of Objects of Cultural Heritage Obtained by the “3D SLS” and “SfM” Methods. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beraldin, J.-A.; Blais, F.; Boulanger, P.; Cournoyer, L.; Domey, J.; El-Hakim, S.F.; Godin, G.; Rioux, M.; Taylor, J. Real world modelling through high resolution digital 3D imaging of objects and structures. ISPRS J. Photogramm. 2000, 55, 230–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollefeys, M.; Koch, R.; Vergauwen, M.; Van Gool, L. Automated reconstruction of 3D scenes from sequences of images. ISPRS J. Photogramm. 2000, 55, 251–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieraccini, M.; Guidi, G.; Atzeni, C. 3D digitizing of cultural heritage. J Cult. Herit. 2001, 2, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remondino, F.; El-Hakim, S. Image-based 3D modelling: A review. Photogram. Rec. 2006, 21, 269–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scopigno, R.; Callieri, M.; Cignoni, P.; Corsini, M.; Dellepiane, M.; Ponchio, F.; Ranzuglia, G. 3D models for cultural heritage: Beyond plain visualization. Computer 2011, 44, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yastikli, N. Documentation of cultural heritage using digital photogrammetry and laser scanning. J. Cult. Herit. 2007, 8, 423–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, H.M.; Yakar, M.; Gulec, S.A.; Dulgerler, O.N. Importance of digital close-range photogrammetry in documentation of cultural heritage. J. Cult. Herit. 2007, 8, 428–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlidis, G.; Koutsoudis, A.; Arnaoutoglou, F.; Tsioukas, V.; Chamzas, C. Methods for 3D digitization of cultural heritage. J. Cult. Herit. 2007, 8, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agosto, E.; Bornaz, L. 3D Models in Cultural Heritage: Approaches for Their Creation and Use. Int. J. Comput. Methods Herit. Sci. 2017, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agisoft Metashape. Available at: https://www.agisoft.com/.

- AliceVision. Available at: https://alicevision.org/.

- Sketchfab. Available at: https://sketchfab.com/.

- Rinaldi, T.; Arrighi, C.; Cirigliano, A.; Neisje De Kruif, F.; Lanteri, L.; Porcelli, G.; Pelosi, C.; Pogliani, P.; Tomassetti, M.C. Innovative, Multidisciplinary Approach for Restoring Paintings in Hypogeal Environment: Etruscan Tomba Degli Scudi (4th Century Bc) in Tarquinia. In: Current Approaches, Solutions and Practices in Conservation of Cultural Heritage. Emre, G, Yilmaz, A., Pogliani, P., Ogruc Ildiz, G., Fausto, R., Eds.. Istanbul University Press: Istanbul, Turkey, 2024; Chapter 17, pp. 343–373. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).