Submitted:

25 April 2025

Posted:

27 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Sample Preparation

2.2. Evaluation of the Nanoadditive Dispersion Technique

2.3. Characterization of Binders and Aggregate

2.4. Methods of Testing Fresh and Hardened Mortars

3. Results

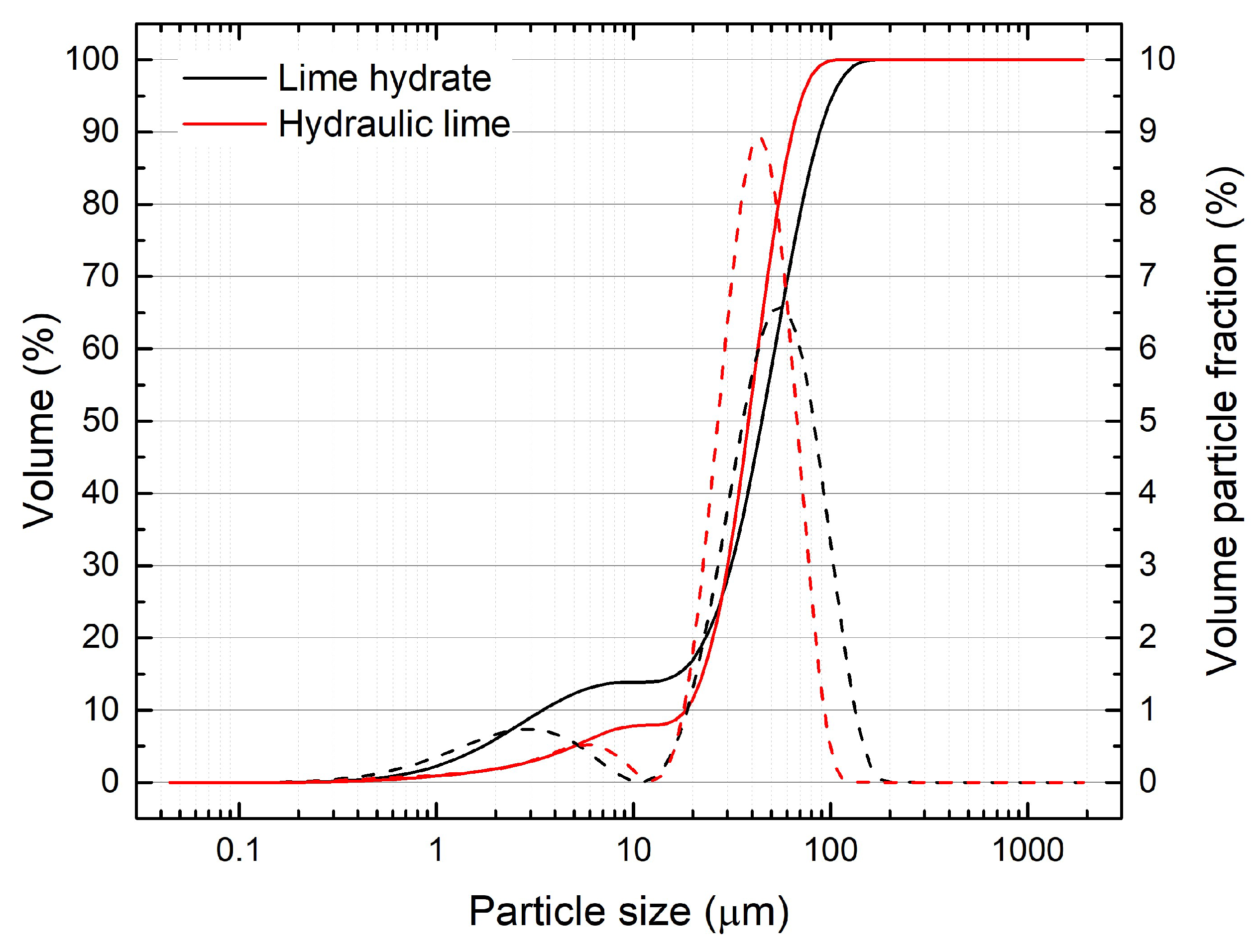

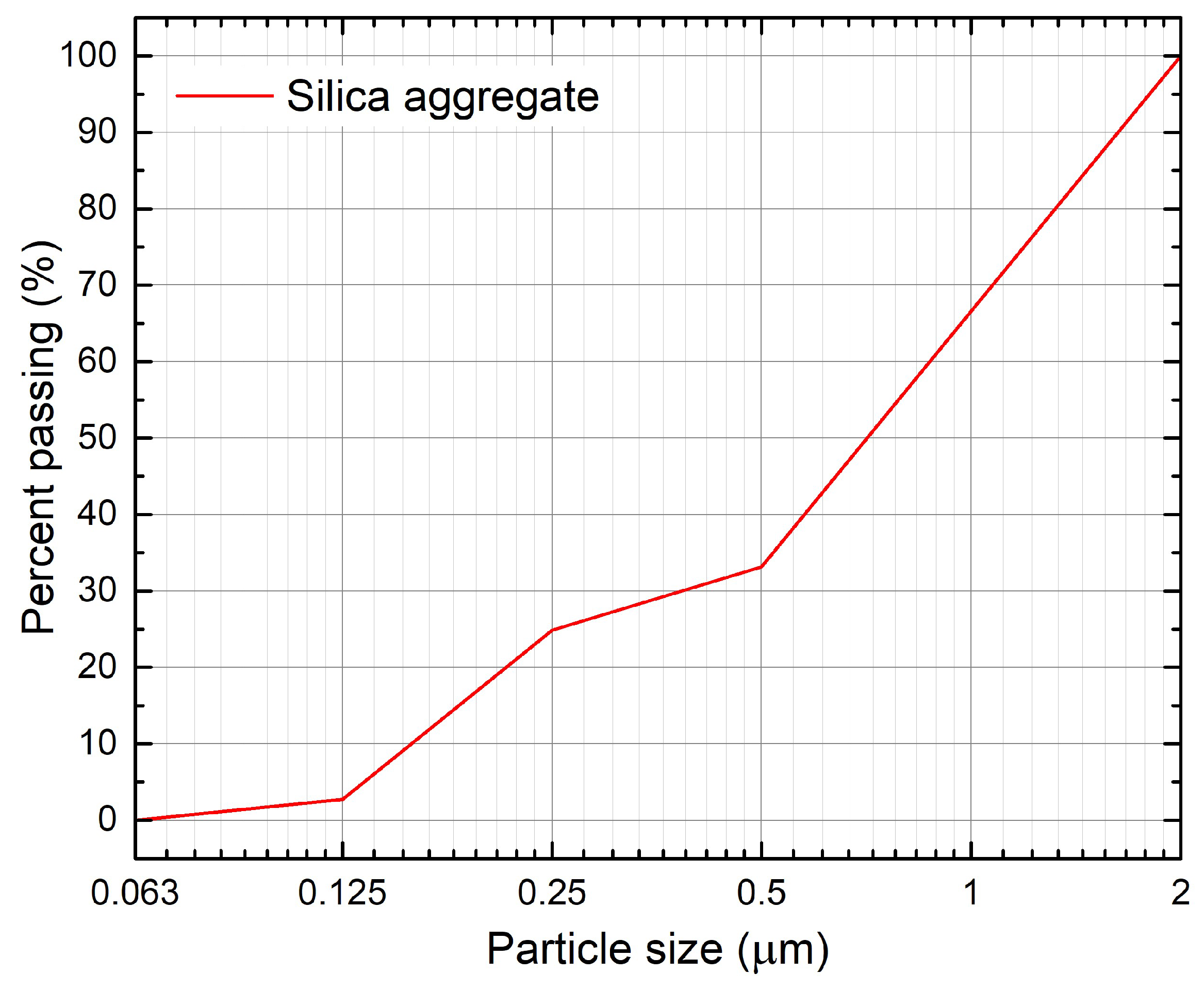

3.1. Characterisation of Raw Materials

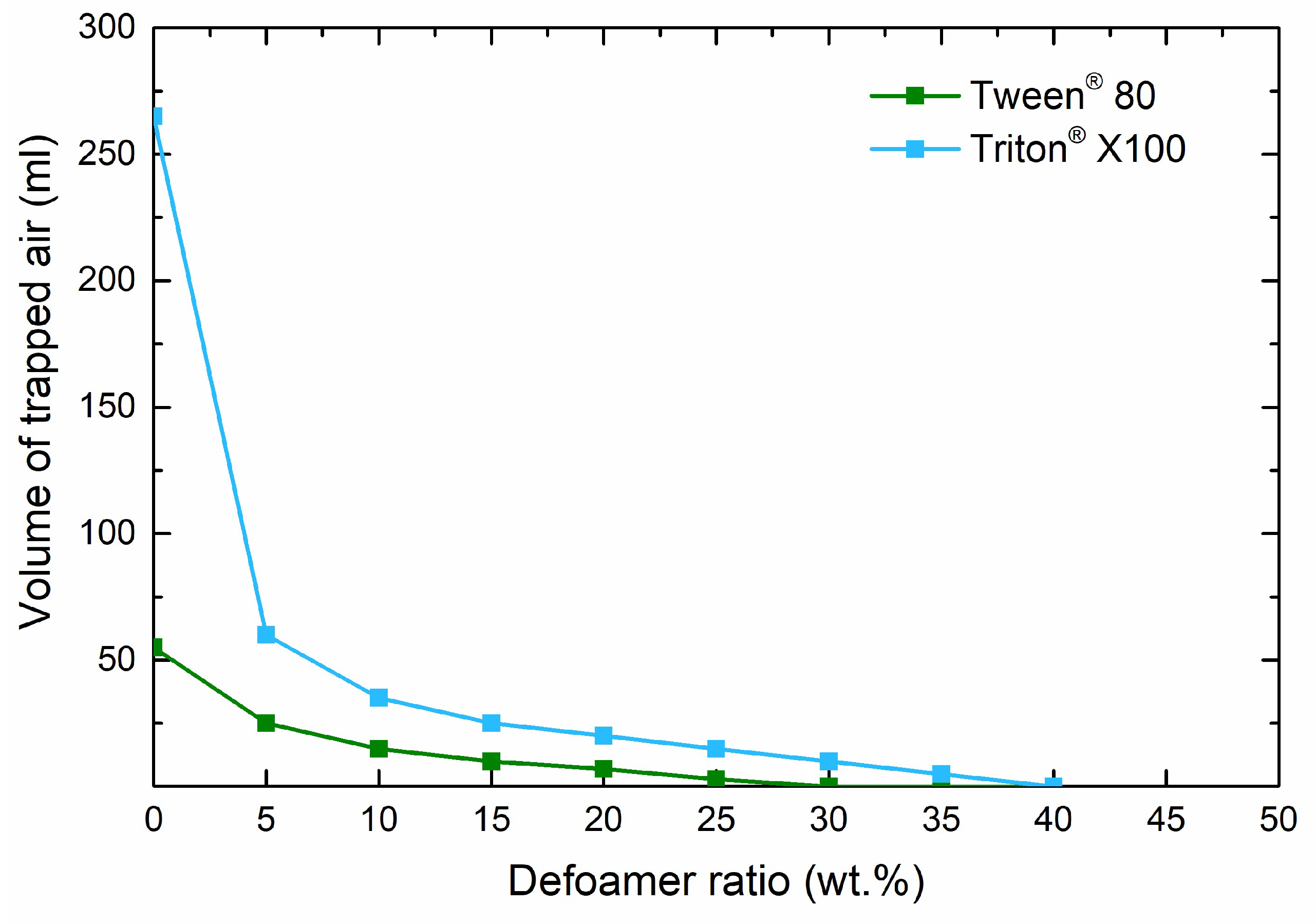

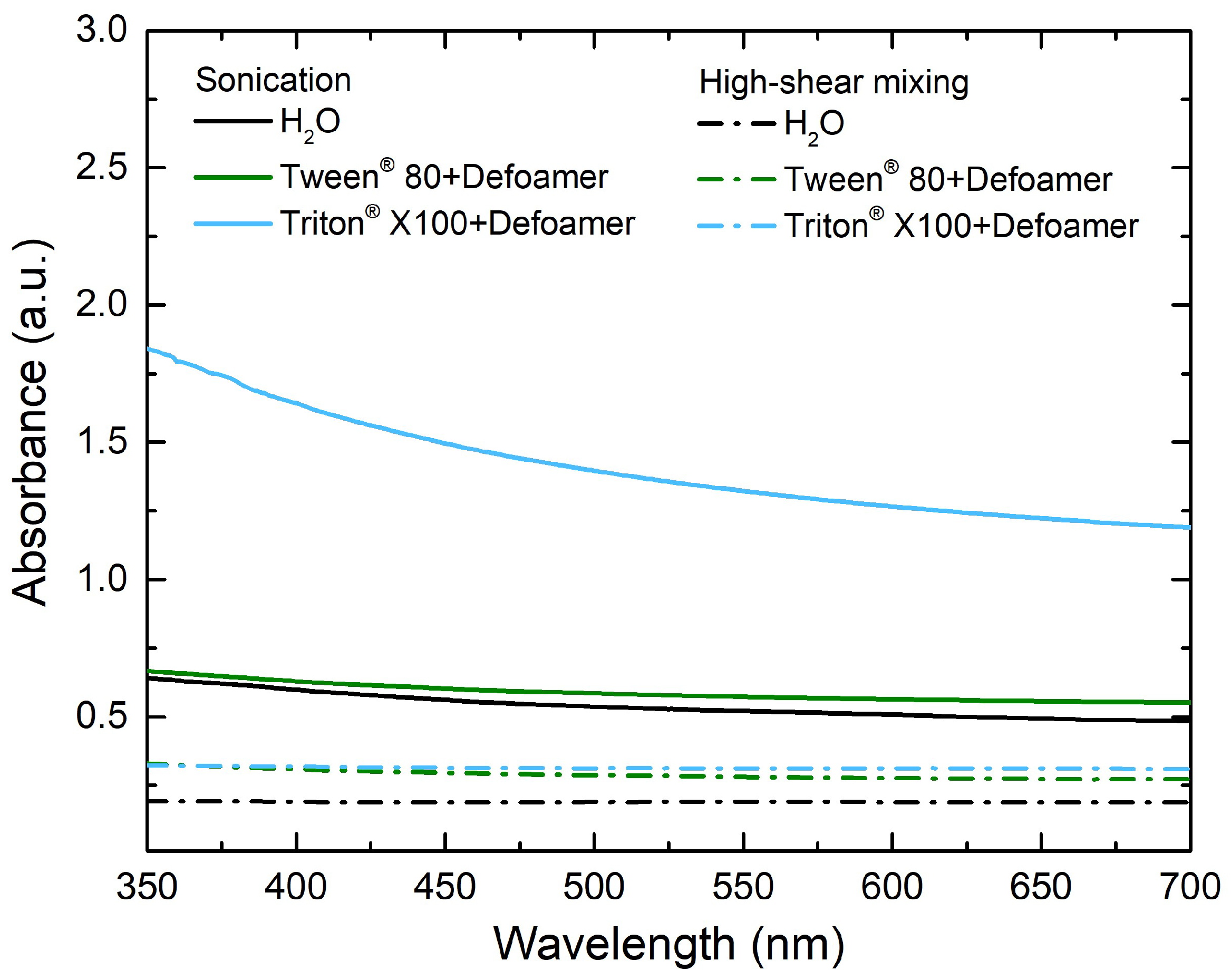

3.2. Dispersion Techniques

3.2. Properties of 28-day and 90-day Hardened Mortars

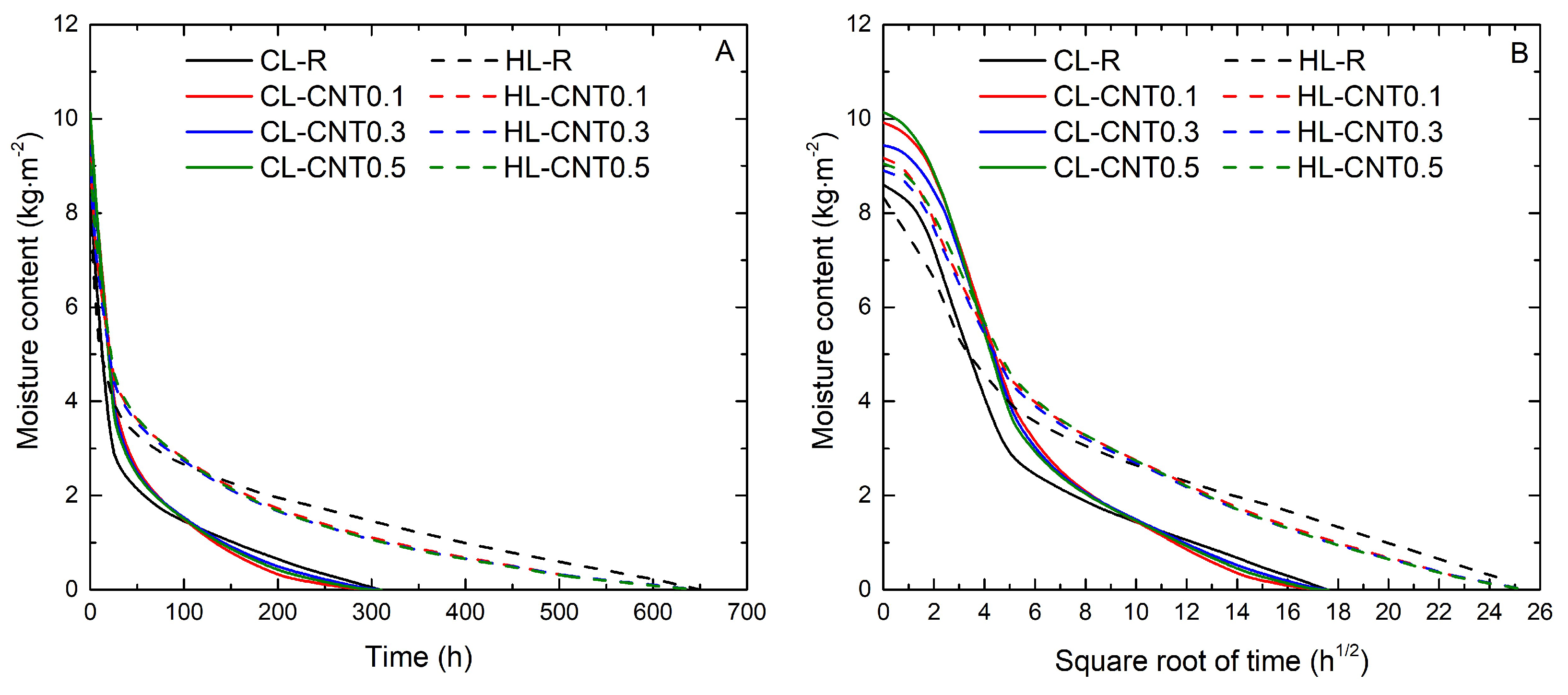

| Mortar | Phase 1Drying Rate D1(kg·m-2·h-1) | Phase 2Drying Rate D2(kg·m-2·h-1/2) | Drying Index DI(-) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CL-R | 0.36 | 1.57 | 0.15 |

| CL-CNT0.1 | 0.29 | 1.64 | 0.15 |

| CL-CNT0.3 | 0.29 | 1.60 | 0.15 |

| CL-CNT0.5 | 0.31 | 1.75 | 0.14 |

| HL-R | 0.26 | 0.88 | 0.19 |

| HL-CNT0.1 | 0.32 | 1.05 | 0.16 |

| HL-CNT0.3 | 0.30 | 1.11 | 0.16 |

| HL-CNT0.5 | 0.27 | 1.13 | 0.16 |

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- The UV/VIS spectroscopy test and the foamability test demonstrated that the most effective technique for producing nanosuspensions is the dispersion of nanotubes in an ultrasonic bath with the addition of surfactant and defoamer.

- (2)

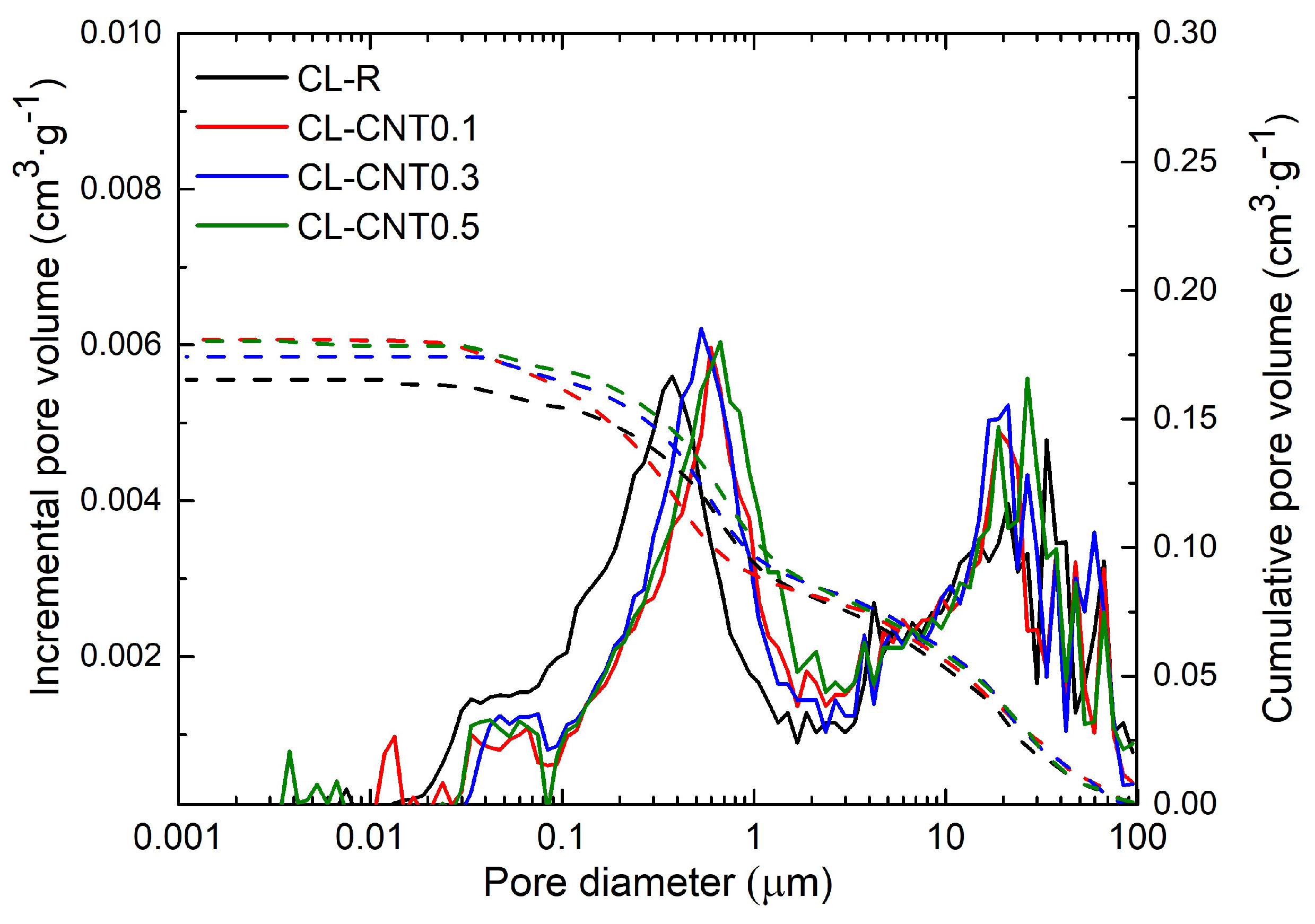

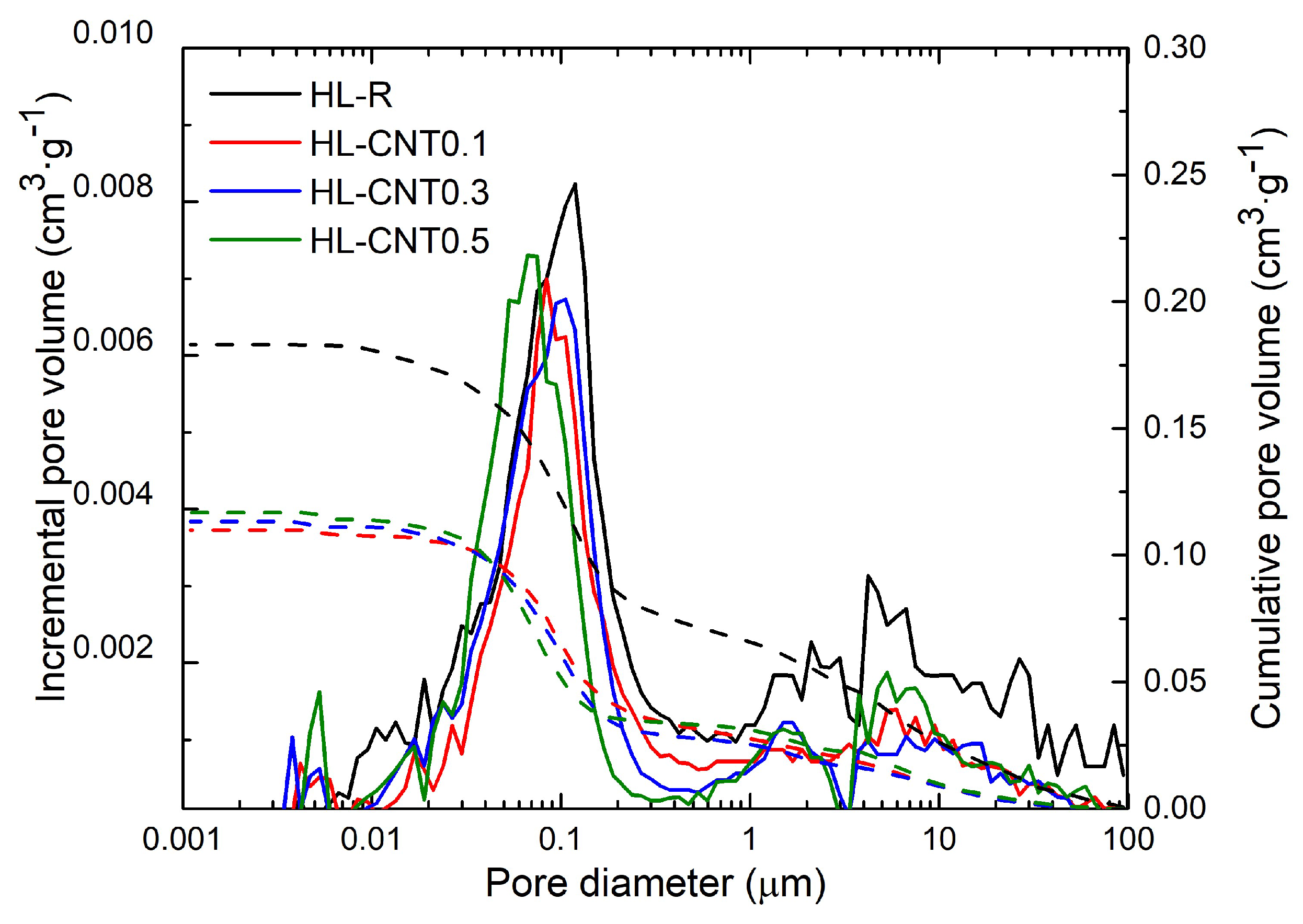

- The incorporation of CNTs resulted in the decreased bulk density and 2% increase in porosity of CL mortars, with no significant impact on the specific density. In contrast, the density of HL mortars exhibited an increase more than 9% (0.1% and 0.3% dosage) and 8% (0.5% dosage), while open porosity showed decrease of 6% compared to the reference hydraulic lime samples. Following a prolonged curing period, a slight increase in bulk and matrix density was observed with a small decrease in porosity.

- (3)

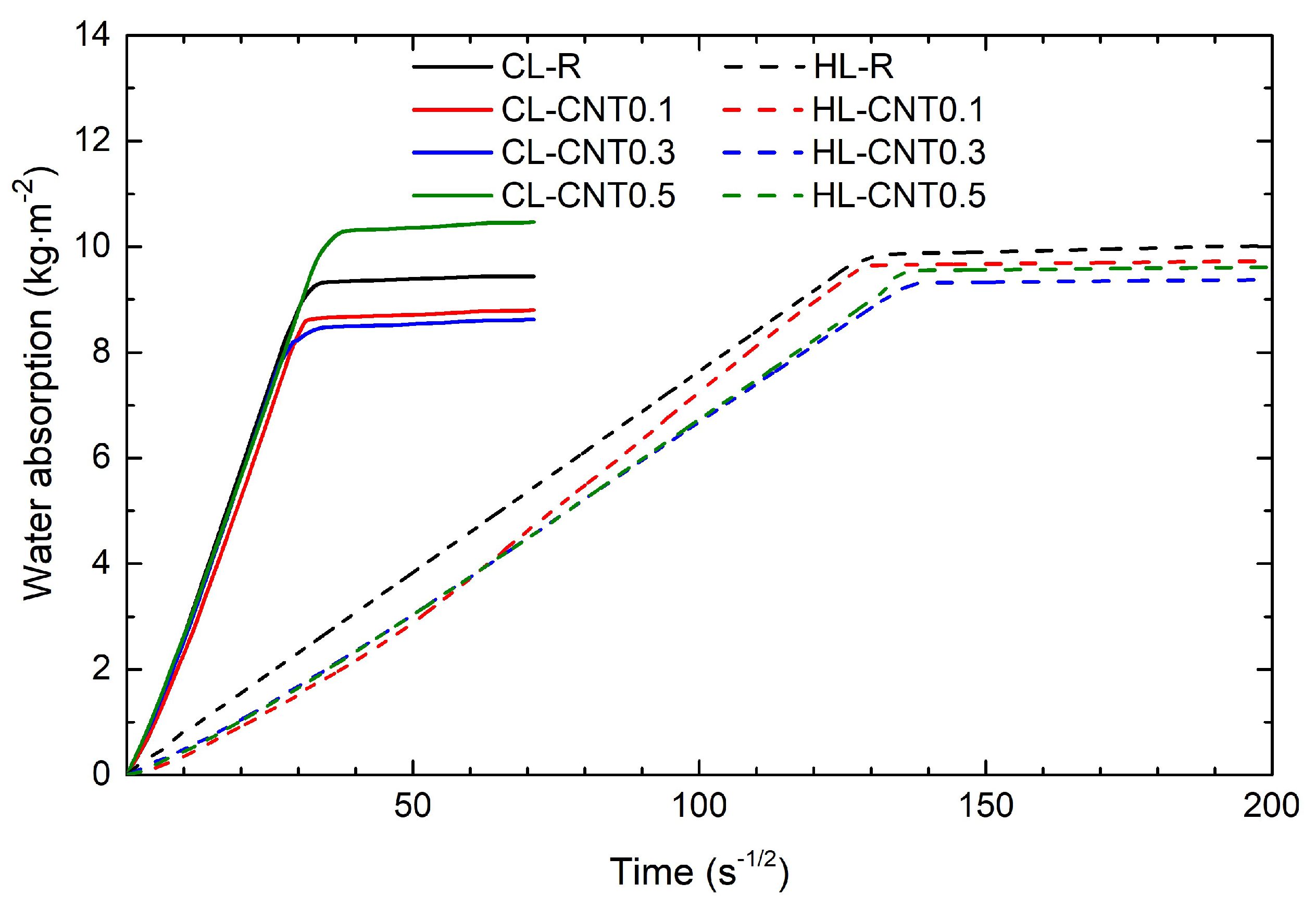

- The water absorption and drying behaviour of CL mortars exhibited no significant changes between the control and modified mortars. The capillary water absorption of the HL mortars was minimal, but significant differences were observed in the drying process. Nano-modification of the HL mortars resulted in accelerated drying (evaporation) and enhanced water vapour transfer.

- (4)

- In the case of CL mortars, the thermal conductivity and volumetric heat capacity showed minor variations due to similar porosity. In HL mortars, both parameters consistently increased with the content CNTs, with maximum increases of 15 %, and 22 % respectively, at 0.5% CNTs dosage. This effect was linked to the reduced porosity in HL mortars and the high thermal conductivity of CNTs themselves.

- (5)

- The beneficial properties of CNTs incorporated into mortars were evident in the mechanical strength assessment. While the 0.1% dose of CNTs exhibited minimal impact on CL mortar, the application of a higher dose (0.3%) led to a substantial enhancement in the compressive strength, surpassing 30% for 28-days cured samples. The modified HL mortar exhibited an enhancement across all applied volumes. A significant effectiveness was observed when 0.3% of CNTs was incorporated, resulting in an increase of the compressive strength exceeding 65 % and nearly 19% improvement of the flexural strength. The extended duration of the curing process led to an improvement in the strength parameters of all samples, resulting in the maximum compressive strengths of 2.28 MPa (CL) and 16.79 MPa (HL) when a volume of 0.3% CNTs was used.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CL | Calcium Lime |

| CNT | Carbon Nanotube |

| GN | Graphene Nanoplatelets |

| HL | Hydraulic Lime |

| MWCNT | Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes |

| NHL | Natural Hydraulic Lime |

| NM | Nanomaterial |

| PC | Portland Cement |

References

- Groot, C.; Veiga, R.; Papayianna, I.; Hees, R.H.; Secco, M.; Alvarez, J.I.; Faria, P.; Stefanidou, M. RILEM TC 277-LHS report: Lime-based mortars for restoration–a review on long-term durability aspects and experience from practice. Mater. Struct. 2022, 55, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsen, J. Microscopy of historic mortars—a review. Cem. Concr. Res. 2006, 36, 1416–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, R.; Pinto, A.P.F.; Gomes, A. Design and behavior of traditional lime-based plasters and renders. Review and critical appraisal of strengths and weaknesses. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2018, 89, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CEMBUREAU. Activity Report 2023; CEMBUREAU—The European Cement Association: Brussels, Belgium, 2024; pp. 29–30. [Google Scholar]

- Loke, M.P.; Pallav, K.; Cultrone, G.; Di Filippo, C. Investigating the standard design and production procedure of heritage mortars for compatible and durable masonry restoration. J. Build. Eng., 2024, 94, 110012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosquera, M.J.; Silva, B.; Prieto, B.; Ruiz-Herrera, E. Addition of cement to lime-based mortars: Effect on pore structure and vapor transport. Cem. Concr. Res. 2006, 36, 1416–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakhsh Mahpour, A.; Ventura, H.; Ardanuy, M.; Rosell, J.R.; Claramunt, J. The effect of fibres and carbonation conditions on the mechanical properties and microstructure of lime/flax composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 138, 104981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klisińska-Kopacz, A.; Tišlova, R.; Adamski, G.; Kozłowski, R. Pore structure of historic and repair Roman cement mortars to establish their compatibility. J. Cult. Herit. 2010, 11, 404–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayta, A.; Bouzerd, H.; Ali-Boucetta, T.; Navarro, A.; Benmalek, M.L. Valorisation of waste glass powder and brick dust in air-lime mortars for restoration of historical buildings: Case study theatre of Skikda (Northern Algeria). Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 315, 125681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco-Torgal, F.; Faria, J.; Jalali, S. Some considerations about the use of lime–cement mortars for building conservation purposes in Portugal: A reprehensible option or a lesser evil? Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 30, 488–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posani, M.; Veiga, R.; De Freitas, V.P. Thermal renders for traditional and historic masonry walls: Comparative study and recommendations for hygric compatibility. Build. Environ. 2023, 228, 109737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeevanagoudar, Y.V.; Krishna, R.H.; Gowda, R.; Preethan, R.; Prabhakara, R. Improved mechanical properties and piezoresistive sensitivity evaluation of MWCNTs reinforced cement mortars. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 144, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalla, P.T.; Tragazikis, I.K.; Trakakis, G.; Galiotis, C.; Dassios, K.G.; Matikas, T.E. Multifunctional Cement Mortars Enhanced with Graphene Nanoplatelets and Carbon Nanotubes. Sensors, 2021, 21, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Li, X.; Li, C.; Zhang, N.; Liu, R.; Lu, C. Improvement of Flexural and Compressive Strength of Cement Mortar by Graphene Nanoplatelets. Open J. Civ. Eng. 2021, 15, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimou, A.-E.; Charalampidou, C.-M.; Metaxa, Z.S.; Kourkoulis, S.K.; Karatasios, I.; Asimakopoulos, G.; Alexopoulos, N.D. Me-chanical and electrical properties of hydraulic lime pastes reinforced with carbon nanomaterials. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2020, 28, 1694–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimou, A.-E.; Metaxa, Z.S.; Alexopoulos, N.D.; Kourkoulis, S.K. Assessing the potential of nano-reinforced blended lime-cement pastes as self-sensing materials for restoration applications. Mater. Today, 2022, 62, 2482–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, P.; Duarte, P.; Barbosa, D.; Ferrira, I. New composite of natural hydraulic lime mortar with graphene oxide. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 156, 1150–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V. S.; Rouxel, D.; Vincent, B. Dispersion of nano-particles: From organic solvents to polymer solutions. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2014, 21, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debbarma, K.; Debnath, B. and Sarkar, P.P. A comprehensive review on the usage of nanomaterials in asphalt mixes. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 361, 129634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N.; Wang, S.; Walsh, F.C. Effective particle dispersion via high-shear mixing of the electrolyte for electroplating a nickel-molybdenum disulphide composite. Electrochim. Acta. 2018, 283, 568–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, I.; Ellis, L.-J.; Romer, I.; Tantra, R.; Carriere, M.; Allard, S.; Mayne-L'Hermite, M.; Minelli, C.; Unger, W.; Potthoff, A. ; Rades, S; Valsami-Jones, E. Dispersion of Nanomaterials in Aqueous Media: Towards Protocol Optimization. J. Vis. Exp. 2017, 130, 56074. [Google Scholar]

- Tantra, R.; Oksel, C.; Robinson, K.N.; Sikora, A.; Wang, X.Z.; Wilkins, T.A. A method for assessing nanomaterial dispersion quality based on principal component analysis of particle size distribution data. Particuology, 2015, 22, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, K.; Lu, M.; Lam, C.; Cheung, H.; Sheng, F.; Li, H. Thermal and mechanical properties of single-walled carbon nanotube bundle-reinforced epoxy nanocomposites: the role of solvent for nanotube dispersion. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2005, 65, 719–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, A.; Pourfattah, F.; Miklós Szilágyi, I.; Afrand, M.; Żyła, G.; Ahn, H.S.; Wongwises, S.; Nguyen, H.M.; Arabkoohsar, A.; Mahian, O. Effect of sonication characteristics on stability, thermo-physical properties, and heat transfer of nanofluids: A comprehensive review. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2019, 58, 104701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshiul Alam, A.K.M. Methods of nanoparticle dispersion in the polymer matrix. In Nanoparticle-Based Polymer Composites; Rangappa, S.M., Parameswaranpillai, J., Gowda, T.G.Y., Siengchin, S., Seydibeyoglu, M.O., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, United Kingdom, 2022; pp. 469–479. [Google Scholar]

- Azunna, S.U.; Aziz, F.N.A.B.A.; Al-Ghazali, N.A.; Rashid, R.S.M.; Bakar, N.A. Review on the mechanical properties of rubberized geopolymer concrete. Clean. Mater. 2024, 11, 100225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauermannová, A.-M.; Jankovský, O.; Jiříčková, A.; Sedmidubský, D.; Záleská, M.; Pivák, A.; Pavlíkvá, M.; Pavlík, Z. MOC Composites for Construction: Improvement in Water Resistance by Addition of Nanodopants and Polyphenol. Polymers 2023, 15, 4300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EN 459-2; Building lime—Part 2: Test Methods. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2021.

- Selvam, C.; Mohan Lal, D.; Harish, S. Enhanced heat transfer performance of an automobile radiator with graphene based suspensions. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 123, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, A.C.; Kaya, F.; Kaya, C. A study on optimum surfactant to multiwalled carbon nanotube ratio in alcoholic stable suspensions via UV–Vis absorption spectroscopy and zeta potential analysis. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 29120–29129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauermannová, A.-M. .; Lojka, M.; Sklenka, J.; Záleská, M.; Pavlíková, M.; Pivák, A.; Pavlík, Z.; Jankovský, O. Magnesium oxychloride-graphene composites: Towards high strength and water resistant materials for construction industry. FlatChem, 2021, 29, 100284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petkova, B.; Tcholakova, S.; Denkov, N. Foamability of surfactant solutions: Interplay between adsorption and hydrodynamic conditions. Colloids Surf. A: Physicochem. Eng. Asp., 2021, 626, 127009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapicová, A.; Pivák, A.; Záleská, M.; Pavlíková, M.; Pavlík, Z. Influence of different surfactants on hydrated lime pastes modified with CNTs. In Proceedings of the International Conference of Numerical Analysis and Applied Mathematics Icnaam 2021, Rhodes, Greece, 20–26 September 2021. [Google Scholar]

- EN 1015-1; Methods of Test for Mortar for Masonry—Part 1: Determination of Particle Size Distribution (by Sieve Analysis). CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 1999.

- EN 1015-3; Methods of Test for Mortar for Masonry—Part 3: Determination of Consistence of Fresh Mortar (by Flow Table). CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2000.

- EN 1015-10; Methods of Test for Mortar for Masonry—Part 10: Determination of Dry Bulk Density of Hardened Mortar. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2000.

- EN 1015-11; Methods of Test for Mortar for Masonry—Part 11: Determination of Flexural and Compressive Strength of Hardened Mortar. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2020.

- EN 12504-4; Testing Concrete in Structures—Part 4: Determination of Ultrasonic Pulse Velocity. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2021.

- EN 1015-18; Methods of Test for Mortar for Masonry—Part 18: Determination of Water Absorption Coefficient Due to Capillarity Action of Hardened Mortar. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2003.

- Pavlík, Z.; Černý, R. Determination of moisture diffusivity as a function of both moisture and temperature. Int. J. Thermophys. 2012, 33, 1704–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 16322; Conservation of Cultural Heritage—Test Methods—Determination of Drying Properties. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2013.

- Han, Z.; Fina, A. Thermal conductivity of carbon nanotubes and their polymer nanocomposites: A review. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2011, 36, 914–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyšvařil, M.; Pavlíková, M.; Záleská, M.; Pivák, A.; Žižlavský, T.; Rovnaníková, P.; Bayer, P.; Pavlík, Z. ; on-hydrophobized perlite renders for repair and thermal insulation purposes: Influence of different binders on their properties and durability. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 263, 120617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, T.D.; Brito, V. Artisanal Lime Coatings and Their Influence on Moisture Transport During Drying. In Historic Mortars; Hughes, J., Válek, J., Groot, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 241–253. [Google Scholar]

- Salomão, M.C.dF.; Bauer, E.; Kazmierczak, C.d.S. Drying parameters of rendering mortars. Ambiente Construido 2018, 18, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Colen, I.; Silva, L.; de Brito, J.; de Feritas, V.P. Drying index for in-service physical performance assessment of renders. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 112, 1101–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffler, G.A.; Plagge, R. Introduction of a Drying Coefficient for Building Materials. ASHRAE Trans. 2010, 116. [Google Scholar]

| Mortar Mix | Lime Hydrate |

Hydraulic Lime | Water | Silica Sand | CNTs | Triton® X-100 |

Defoamer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CL-R | 1500 | - | 1575 | 3 x 1500 | - | - | - |

| CL-CNT0.1 | 1500 | - | 1620 | 3 x 1500 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 0.675 |

| CL- CNT0.3 | 1500 | - | 1575 | 3 x 1500 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 2.025 |

| CL- CNT0.5 | 1500 | - | 1545 | 3 x 1500 | 7.5 | 7.5 | 3.375 |

| HL-R | - | 1500 | 1015 | 3 x 1500 | - | - | - |

| HL- CNT0.1 | - | 1500 | 1015 | 3 x 1500 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 0.675 |

| HL- CNT0.3 | - | 1500 | 1015 | 3 x 1500 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 2.025 |

| HL- CNT0.5 | - | 1500 | 1015 | 3 x 1500 | 7.5 | 7.5 | 3.375 |

| Property | Symbol | Unit | ECU (%) | Standard /method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bulk density | ρb | kg∙m-3 | 1.4 | EN 1015-10 [36] |

| Specific density | ρm | kg∙m-3 | 1.2 | He pycnometry |

| Open porosity | ψ | % | 2.0 | EN 1015-10/He pycnometry |

| Pore size diameter | dp | cm3∙g-1 | - | Mercury intrusion Porosimetry (MIP) |

| Average pore diameter | da | μm | - | MIP |

| Pore size distribution | PSD | % | - | MIP |

| Flexural strength | ff | MPa | 1.4 | EN 1015-11 [37] |

| Compressive strength | fc | MPa | 1.4 | EN 1015-11 [37] |

| Young´s modulus | E | GPa | 2.3 | EN 12504-4 [38] |

| Thermal conductivity | λ | W∙m-1∙K-1 | 2.3 | Transient pulse technique |

| Volumetric heat capacity | CV | MJ∙m-3∙K-1 | 2.3 | Transient pulse technique |

| Water absorption coefficient |

Aw | kg∙m-2∙s-1/2 | 2.3 | EN 1015-18 [39] |

| 24-hour water absorption | Wa24 | kg∙m-2 | 1.4 | EN 1015-18 [39] |

| Apparent moisture diffusivity |

κ | m2∙s-1 | 2.3 | EN 1015-18 [39] |

| Phase 1 drying rate | D1 | kg∙m-2∙h-1 | - | EN 16322 [41] |

| Phase 2 drying rate | D2 | kg∙m-2∙h-1/2 | - | EN 16322 [41] |

| Drying index | DI | - | - | EN 16322 [41] |

| Material | Lime Hydrate | Hydraulic Lime | Silica sand |

|---|---|---|---|

| CaO | 95.31 | 57.84 | 0.01 |

| Al2O3 | 3.07 | 11.63 | 3.23 |

| SiO2 | 0.27 | 20.45 | 96.34 |

| MgO | 1.22 | 1.47 | 0.35 |

| Fe2O3 | 0.06 | 1.78 | 0.04 |

| SrO | 0.04 | 0.05 | - |

| NiO | 0.03 | - | - |

| Na2O | - | 2.38 | - |

| K2O | - | 2.32 | 0.01 |

| SO3 | - | 1.43 | 0.01 |

| MnO | - | 0.32 | - |

| TiO2 | - | 0.26 | 0.01 |

| ZrO | - | 0.07 | - |

| ∑ | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Material | Loose Bulk Density (kg·m-3) |

Specific Density (kg·m-3) |

Blaine Specific Surface (m2·kg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lime hydrate | 445 | 2228 | 1655 |

| Hydraulic lime | 788 | 2625 | 358 |

| Silica sand | 1671 | 2646 | - |

| Mortar | Bulk Density ρb (kg·m-3) |

Specific Density ρs (kg·m-3) |

Porosity ψ (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 28 Days | 90 Days | 28 days | 90 Days | 28 Days | 90 Days | |

| CL-R | 1656 ± 23 | 1675 ± 23 | 2545 ± 31 | 2552± 31 | 34.9 ± 0.7 | 34.4 ± 0.7 |

| CL-CNT0.1 | 1599 ± 22 | 1618 ± 23 | 2535 ± 30 | 2548 ± 31 | 36.9 ± 0.7 | 35.0 ± 0.7 |

| CL-CNT0.3 | 1617 ± 23 | 1659 ± 23 | 2537 ± 30 | 2550 ± 31 | 36.3 ± 0.7 | 34.9 ± 0.7 |

| CL-CNT0.5 | 1601 ± 22 | 1659 ± 23 | 2538 ± 30 | 2549 ± 31 | 36.9 ± 0.7 | 34.9 ± 0.7 |

| HL-R | 1740 ± 24 | 1754 ± 25 | 2575 ± 31 | 2577 ± 31 | 32.4 ± 0.6 | 31.9 ± 0.6 |

| HL-CNT0.1 | 1900 ± 27 | 1908 ± 27 | 2578 ± 31 | 2599 ± 31 | 26.3 ± 0.5 | 26.6 ± 0.5 |

| HL-CNT0.3 | 1893 ± 27 | 1902 ± 27 | 2563 ± 31 | 2596 ± 31 | 26.2 ± 0.5 | 26.7 ± 0.5 |

| HL-CNT0.5 | 1881 ± 26 | 1902 ± 27 | 2547 ± 31 | 2597 ± 31 | 26.2 ± 0.5 | 26.8 ± 0.5 |

| Mortar | Total Pore Volume dp (cm3·g-1) |

Average Pore Diameter da (µm) |

|---|---|---|

| CL-R | 0.165 | 0.197 |

| CL-CNT0.1 | 0.181 | 0.218 |

| CL-CNT0.3 | 0.174 | 0.212 |

| CL-CNT0.5 | 0.180 | 0.219 |

| HL-R | 0.183 | 0.068 |

| HL-CNT0.1 | 0.110 | 0.055 |

| HL-CNT0.3 | 0.113 | 0.058 |

| HL-CNT0.5 | 0.117 | 0.063 |

| Mortar | Flexural Strength ff (MPa) |

Compressive Strength fc (MPa) |

Dynamic Modulus of Elasticity E (GPa) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 28 Days | 90 Days | 28 Days | 90 Days | 28 Days | 90 Days | |

| CL-R | 0.48 ± 0.01 | 0.86 ± 0.01 | 0.55 ± 0.01 | 1.86 ± 0.03 | 4.2 ± 0.1 | 4.5 ± 0.1 |

| CL-CNT0.1 | 0.48 ± 0.01 | 0.82 ± 0.01 | 0.55 ± 0.01 | 1.98 ± 0.03 | 3.3 ± 0.1 | 3.7 ± 0.1 |

| CL-CNT0.3 | 0.51 ± 0.01 | 0.88 ± 0.01 | 0.72 ± 0.01 | 2.28 ± 0.03 | 3.5 ± 0.1 | 3.7 ± 0.1 |

| CL-CNT0.5 | 0.39 ± 0.01 | 0.77 ± 0.01 | 0.44 ± 0.01 | 1.95 ± 0.03 | 3.2 ± 0.1 | 3.4 ± 0.1 |

| HL-R | 2.16 ± 0.03 | 2.33 ± 0.03 | 7.43 ± 0.10 | 10.20 ± 0.14 | 10.3 ± 0.3 | 10.7 ± 0.3 |

| HL-CNT0.1 | 2.42 ± 0.03 | 2.45 ± 0.04 | 11.78 ± 0.16 | 14.36 ± 0.20 | 12.0 ± 0.3 | 12.2 ± 0.3 |

| HL-CNT0.3 | 2.57 ± 0.04 | 2.60 ± 0.03 | 12.28 ± 0.17 | 16.79 ± 0.24 | 11.9 ± 0.3 | 12.1 ± 0.3 |

| HL-CNT0.5 | 2.42 ± 0.03 | 2.24 ± 0.03 | 11.27 ± 0.16 | 14.65 ± 0.21 | 11.5 ± 0.3 | 11.7 ± 0.3 |

| Mortar | Thermal Conductivity λ (W·m-1·K-1) |

Volumetric Heat Capacity Cv x 106 (J·m-3·K-1) |

|---|---|---|

| CL-R | 1.125 ± 0.026 | 1.176 ± 0.027 |

| CL-CNT0.1 | 1.056 ± 0.024 | 1.153 ± 0.027 |

| CL-CNT0.3 | 1.094 ± 0.025 | 1.174 ± 0.027 |

| CL-CNT0.5 | 1.096 ± 0.025 | 1.182 ± 0.027 |

| HL-R | 1.107 ± 0.025 | 1.070 ± 0.025 |

| HL-CNT0.1 | 1.248 ± 0.029 | 1.312 ± 0.030 |

| HL-CNT0.3 | 1.252 ± 0.029 | 1.323 ± 0.030 |

| HL-CNT0.5 | 1.280 ± 0.029 | 1.362 ± 0.031 |

| Mortar | Water Absorption Coefficient Aw (kg·m-2·s-1/2) |

24 h Water Absorption Wa24 (kg·m-2) |

|---|---|---|

| CL-R | 0.31 ± 0.01 | 9.40 ± 0.13 |

| CL-CNT0.1 | 0.30 ± 0.01 | 9.47 ± 0.13 |

| CL-CNT0.3 | 0.30 ± 0.01 | 9.44 ± 0.13 |

| CL-CNT0.5 | 0.30 ± 0.01 | 9.65 ± 0.14 |

| HL-R | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 8.73 ± 0.12 |

| HL-CNT0.1 | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 8.78 ± 0.12 |

| HL-CNT0.3 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 8.75 ± 0.12 |

| HL-CNT0.5 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 8.59 ± 0.12 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).