Submitted:

30 April 2025

Posted:

02 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Data Source

2.3. Study Population

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient

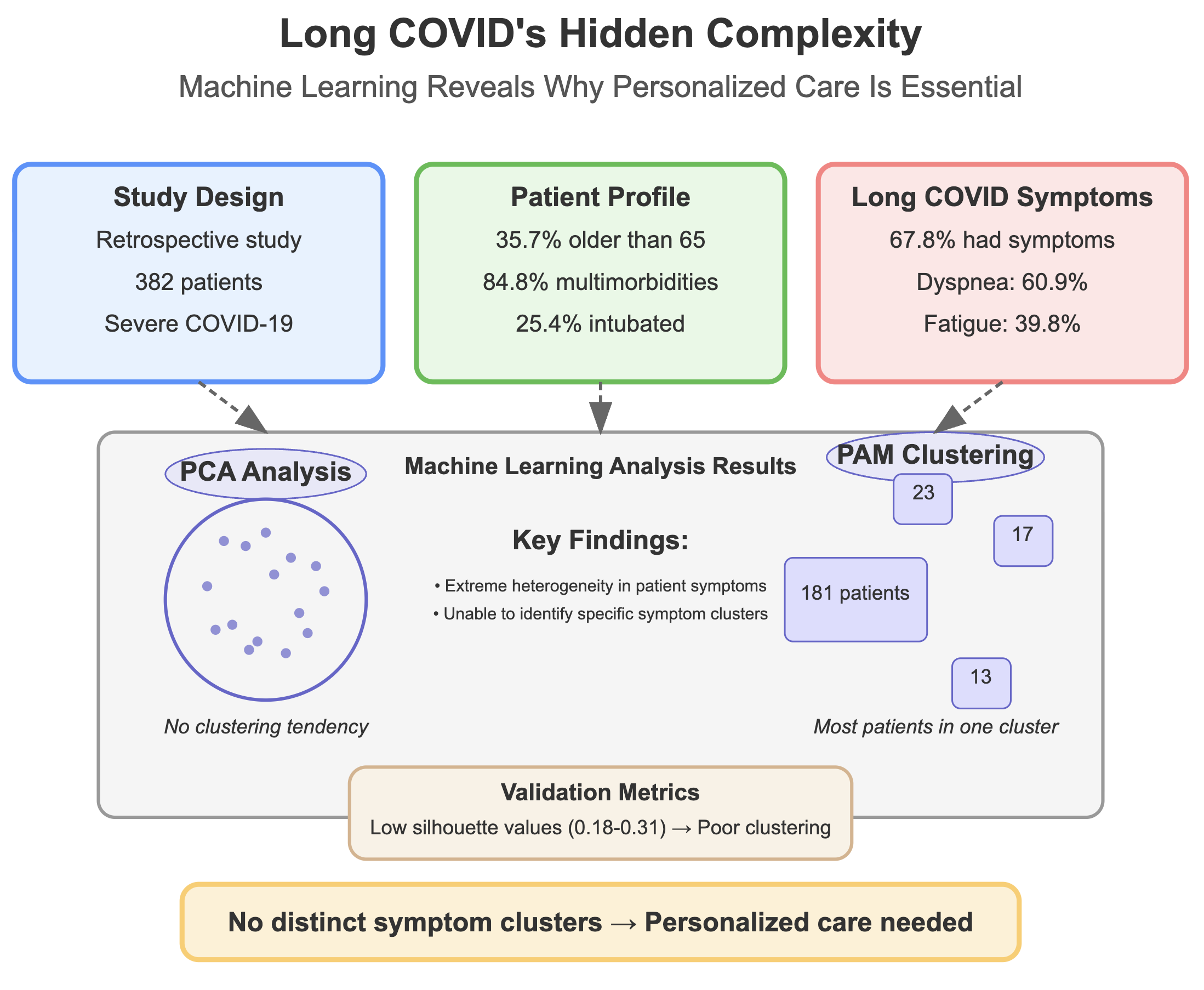

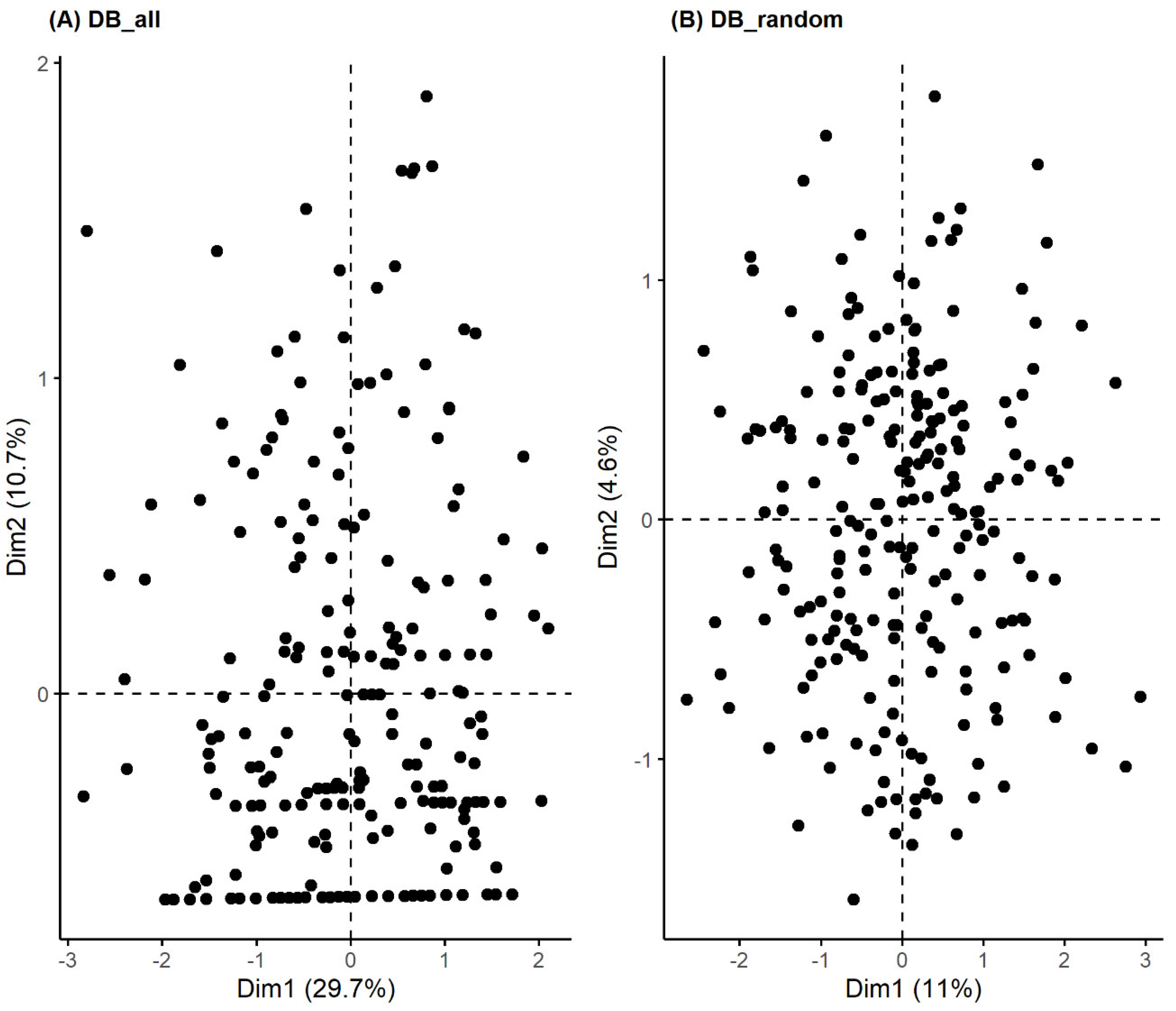

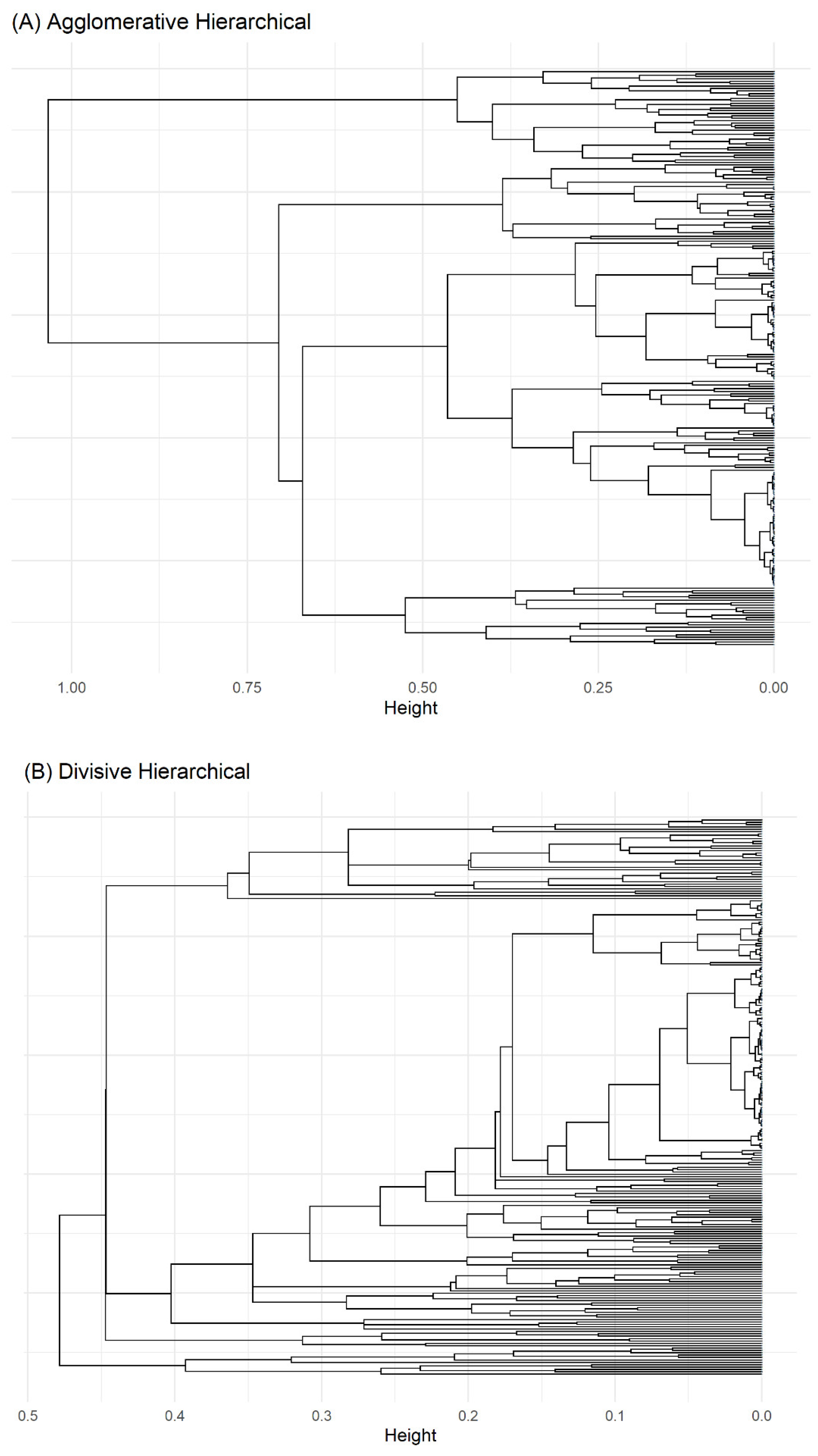

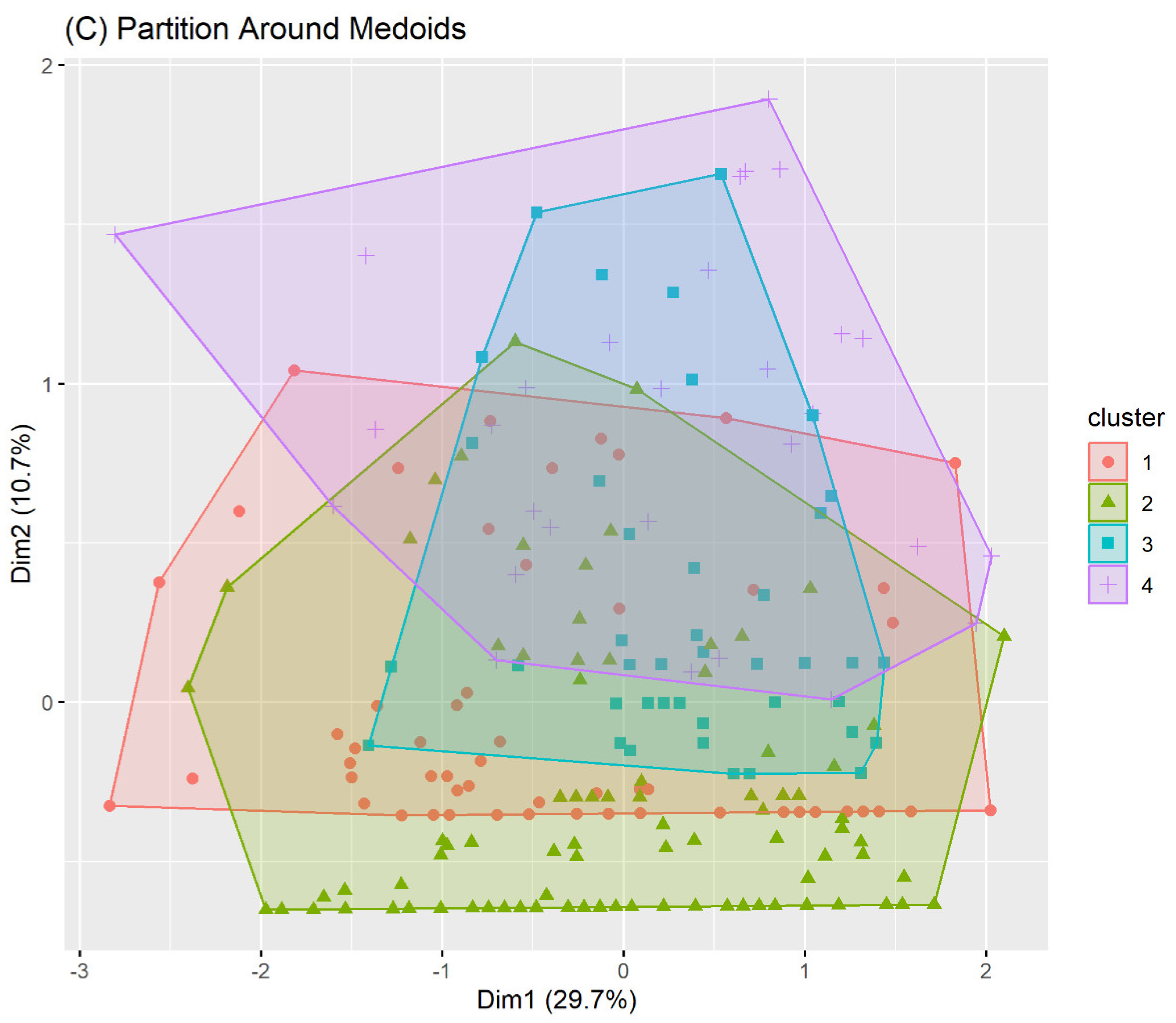

3.2. Unsupervised Machine Learning for the Identification of Patient Aggregation

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Discussion

5. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

References

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). COVID-19 rapid guideline: managing the long-term effects of COVID-19. 2020 Dec 18.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 Post-COVID Condition: Information for Healthcare Providers. 2022. vols. 1-16.

- Thaweethai T, Jolley SE, Karlson EW, Levitan EB, Levy B, McComsey GA et al. Development of a Definition of Postacute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection JAMA. 2023 Jun 13; 329(22): 1934–1946. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Crook H, Raza S, Nowell J, Young M, Edison P. Long Covid-mechanisms, risk factors, and management. BMJ. 2021 Jul; 26: 374: n1648. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astin R, Banerjee A, Baker MR, Dani M, Ford E, Hull JH et al. Long COVID: mechanisms, risk factors and recovery. Exp Physiol. 2023 Jan; 108(1): 12-27. Epub 2022 Nov 22. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Najafi MB, Javanmard SH. Post-COVID-19 syndrome mechanisms, prevention and management. Int J Prev Med 2023; 14: 59. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- van Kessel SAM, Olde Hartman TC, Lucassen PLBJ, van Jaarsveld CHM. Post-acute and long-COVID-19 symptoms in patients with mild diseases: a systematic review. Family Practice, 2022, 159–167. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C, Palacios-Ceña D, Gómez-Mayordomo V, Florencio LL, Cuadrado ML, Plaza-Manzano G, Navarro-Santana M et al. Prevalence of post-COVID-19 symptoms in hospitalized and non-hospitalized COVID-19 survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Intern Med. 2021; 92:55–70. Epub 2021 Jun 16. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Davis H.E., McCorkell L., Vogel J.M., J. Topol E. Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations Nat Rev Microbiol 2023, 21(3):133-146. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C, Martín-Guerrero JD, Florencio LL, Navarro-Pardo E, Rodríguez-Jiménez J, Torres-Macho J et al. Clustering analysis reveals different profiles associating long-term post-COVID symptoms, COVID-19 symptoms at hospital admission and previous medical co-morbidities in previously hospitalized COVID-19 survivors. Infection 2023 Feb;51(1):61-69. Epub 2022 Apr 22. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kisiel MA, Lee S, Malmquist S, Rykatkin O, Holgert S, Janols H et al. Clustering Analysis Identified Three Long COVID Phenotypes and Their Association with General Health Status and Working Ability. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023;12(11):3617. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Subramanian A, Nirantharakumar K, Hughes S, Myles P, Williams T, Gokhale KM et al. Symptoms and risk factors for long COVID in non-hospitalized adults. Nature Medicine, august 2022; vol 28: 1706–1714. Epub 2022 Jul 25. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Seeßle J, Waterboer T, Hippchen T, Simon J, Kirchner M, Lim A et al. Persistent Symptoms in Adult Patients 1 Year After Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Prospective Cohort Study. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2021; 20 (20):1–8. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Greenhalgh T, Sivan M, Delaney B, Evans R, Milne R. Long covid—an update for primary care. BMJ 2022, 378, e072117.

- Sisó-Almirall A, Brito-Zerón P, Conangla Ferrín L, Kostov B, Moragas Moreno A, Mestres J et al. Long Covid-19: Proposed Primary Care Clinical Guidelines for Diagnosis and Disease Management. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021,18, 4350. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria. 2023.

- Tsuchida T, Yoshimura N, Ishizuka K, Katayama K, Inoue Y, Hirose M et al. Five cluster classifications of long COVID and their background factors: A cross-sectional study in Japan. Clin Exp Med. 2023 Nov;23(7):3663-3670. Epub 2023 Apr 7. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bai F, Tomasoni D, Falcinella C, Barbanotti D, Castoldi R, Mulè G et al. Female gender is associated with long COVID syndrome: a prospective cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2022 Apr;28(4):611.e9-611.e16. Epub 2021 Nov 9. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Marchi M, Grenzi P, Serafini V, Capoccia F, Rossi F, Marrino P et al. Psychiatric symptoms in Long-COVID patients: a systematic review. Front Psychiatry. 2023 Jun 21;14:1138389. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zakia H, Pradana K, Iskandar S. Risk factors for psychiatric symptoms in patients with long COVID: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2023 Apr 7;18(4):e0284075. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Goldhaber NH, Kohn JN, Ogan WS, Sitapati A, Longhurst CA, Wang A et al. Deep Dive into the Long Haul: Analysis of Symptom Clusters and Risk Factors for Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19 to Inform Clinical Care. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Dec 15;19(24):16841. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kisiel MA, Lee S, Malmquist S, Rykatkin O, Holgert S, Janols H et al. Clustering Analysis Identified Three Long COVID Phenotypes and Their Association with General Health Status and Working Ability. J Clin Med. 2023 May 23;12(11):3617. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Perlis RH, Santillana M, Ognyanova K, Safarpour A, Lunz Trujillo K, Simonson MD et al. Prevalence and Correlates of Long COVID Symptoms Among US Adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2022 Oct 3;5(10):e2238804. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chudzik M, Babicki M, Kapusta J, Kałuzińska-Kołat Ż, Kołat D, Jankowski P et al. Long-COVID Clinical Features and Risk Factors: A Retrospective Analysis of Patients from the STOP-COVID Registry of the PoLoCOV Study. Viruses. 2022 Aug 11;14(8):1755. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Szabo S, Zayachkivska O, Hussain A, Muller V. What is really ‘Long COVID’? Inflammopharmacology. 2023 Apr;31(2):551-557. Epub 2023 Mar 25. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ziauddeen N, Gurdasani D, O’Hara ME, Hastie C, Roderick P et al. Characteristics and impact of Long Covid: Findings from an online survey. PLoS One. 2022 Mar 8;17(3):e0264331. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Reese JT, Blau H, Casiraghi E, Bergquist T, Loomba JJ, Callahan TJ et al. Generalisable long COVID subtypes: findings from the NIH N3C and RECOVER programmes. EBioMedicine. 2023 Jan; 87:104413. Epub 2022 Dec 21. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| ICD9-CM chapter |

Overall N = 3821 |

San Matteo Hosp N = 2421 |

Cremona Hosp N = 1401 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (F) | - | 102 (26.7%) | 72 (29.8%) | 30 (21.4%) |

| Age > 65 | - | 136 (35.7%) | 84 (34.7%) | 52 (37.4%) |

| Endotracheal intubation | - | 97 (25.4%) | 51 (21.1%) | 46 (32.9%) |

| Multimorbidities | - | 324 (84.8%) | 200 (82.6%) | 124 (88.6%) |

| Circulatory | 7 | 176 (46.1%) | 126 (52.1%) | 50 (35.7%) |

| Endocrin | 3 | 76 (19.9%) | 66 (27.3%) | 10 (7.1%) |

| Genitourinary | 10 | 34 (8.9%) | 24 (9.9%) | 10 (7.1%) |

| Neurological | 6 | 25 (6.5%) | 21 (8.7%) | 4 (2.9%) |

| Gastroenterological | 9 | 13 (3.4%) | 11 (4.5%) | 2 (1.4%) |

| Cancer | 2 | 12 (3.1%) | 8 (3.3%) | 4 (2.9%) |

| Haematological | 4 | 10 (2.6%) | 9 (3.7%) | 1 (0.7%) |

| Dermatological | 12 | 8 (2.1%) | 5 (2.1%) | 3 (2.1%) |

| Trauma | 17 | 6 (1.6%) | 4 (1.7%) | 2 (1.4%) |

| Mental | 5 | 5 (1.3%) | 4 (1.7%) | 1 (0.7%) |

| Musculoskeletal | 13 | 4 (1.0%) | 4 (1.7%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Other | 18 | 157 (41.1%) | 28 (11.6%) | 129 (92.1%) |

| Symptoms | 16 | 113 (29.6%) | 7 (2.9%) | 106 (75.7%) |

| Symptom | All (N=382) |

San Matteo Hosp (N=242) |

Cremona Hosp (N=140) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % (95%CI) | N | % (95%CI) | N | % (95%CI) | |

| Residual Symptoms | 253 | 67.8 (62.8, 72.5) | 148 | 63.5 (56.9, 69.6) | 105 | 75.0 (66.8, 81.8) |

| Multiple Symptoms | ||||||

|

1 2 3+ |

107 77 74 |

28.0 (23.6, 32.9) 20.2 (16.3, 24.6) 19.4 (15.6, 23.8) |

71 46 36 |

29.3 (23.8, 35.6) 19.0 (14.4, 24.6) 14.9 (10.8, 20.1) |

36 31 38 |

25.7 (18.9, 33.9) 22.1 (15.8, 30.1) 27.1 (20.1, 35.4) |

| Dyspnea | 170 | 60.9 (54.9, 66.6) | 100 | 68.5 (60.2, 75.8) | 70 | 52.6 (43.8, 61.3) |

| Fatigue | 109 | 39.8 (34.0, 45.9) | 64 | 45.7 (37.3, 54.3) | 45 | 33.6 (25.8, 42.3) |

| Neuro-psychological symptoms | 69 | 30.4 (24.6, 36.9) | 33 | 35.9 (26.3, 46.6) | 36 | 26.7 (19.6, 35.1) |

| Rheumatologic symptoms | 47 | 21.1 (16.0, 27.1) | 21 | 23.6 (15.5, 34.0) | 26 | 19.4 (13.3, 27.3) |

| Cardiovascular symptoms | 47 | 17.2 (13.0, 22.3) | 28 | 20.3 (14.1, 28.2) | 19 | 14.1 (8.9, 21.4) |

| Otorhinolaryngological symptoms | 28 | 10.3 (7.1, 14.7) | 20 | 14.5 (9.3, 21.7) | 8 | 6.0% (2.8, 11.8) |

| Dermatologic symptoms | 22 | 9.8 (6.4, 14.6) | 6 | 6.7 (2.7, 14.5) | 16 | 11.9 (7.1, 18.8) |

| Cough | 18 | 6.6 (4.1, 10.5) | 7 | 5.1% (2.3, 10.7) | 11 | 8.1 (4.3, 14.4) |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 19 | 6.9 (4.3, 10.8) | 16 | 11.4 (6.9, 18.2) | 3 | 2.2 (0.6, 6.9) |

| Headache | 11 | 4.9 (2.6, 8.9) | 9 | 10.1 (5.0, 18.8) | 2 | 1.5 (0.3, 5.8) |

| Method | Average Silhouette | Separation Index (SI) | Cophenetic correlation coefficient | Entropy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agglomerative Clustering | 0.31 | 0.05 | 0.61 | 1.10 |

| Divisive Clustering | 0.31 | 0.03 | 0.74 | 0.74 |

| PAM Clustering | 0.18 | 0.01 | - | 1.27 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).